Abstract

Tobacco use is increasingly concentrated within marginalized groups, including LGBTQ+ young adults. Developing tailored interventions to reduce tobacco-related health disparities requires understanding the mechanisms linking individual and contextual factors associated with tobacco use to behavior. This paper presents an in-depth exploration of three cases from a novel mixed method study designed to identify the situational factors and place-based practices of substance use among high-risk individuals. We combined geographically explicit ecological momentary assessment (GEMA) with an adapted travel diary-interview method. Participants (young adult bisexual smokers, ages 18-26) reported on non-smoking and smoking situations for 30 days with a smartphone app. GEMA surveys captured internal and external situational factors (e.g., craving intensity, location type, seeing others smoking). Continuous locational data was collected via smartphone GPS. Subsequently, participants completed in-depth interviews reviewing maps of their own GEMA data. GEMA data and transcripts were analyzed separately and integrated at the case level in a matrix. Using GEMA maps to guide the interview grounded discussion in participants' everyday smoking situations and routines. Interviews clarified participant interpretation of GEMA measures and revealed experiences and meanings of smoking locations and practices. The GEMA method identified the most frequent smoking locations/times for each participant (e.g., afternoons at university). Interviews provided description of associated situational factors and perceptions of smoking contexts (e.g., peer rejection of bisexual identity) and the roles of smoking therein (e.g., physically escape uncomfortable environments). In conclusion, this mixed method contributes to advancing qualitative GIS and other hypothesis-generating approaches working to reveal the richness of individuals' experiences of the everyday contexts of health behavior, while also providing reliable measures of situational predictors of behaviors of interest, such as substance use. Limitations of and future directions for the method are discussed.

Keywords: Ecological momentary assessment, geolocation, space-time geography, qualitative GIS, tobacco, health disparities, United States, sexual and gender minorities

Introduction

Tobacco control policies have reduced smoking rates among higher income populations, leaving “smoking islands” (Thompson, Pearce and Barnett 2007) of high tobacco use among poor and minority groups. Understanding of how and why high rates of tobacco use persist among marginalized groups is needed to develop tailored interventions that can effectively reduce tobacco-related health disparities and experiences of social exclusion related to smoker stigma for these individuals (Blosnich, Lee and Horn 2013, Frohlich et al. 2012, Lee, Griffin and Melvin 2009, Pearce, Barnett and Moon 2012). Interest in the roles of context in understanding tobacco and other substance use disparities has grown in recent years (Thomas, Richardson and Cheung 2008, Barnett et al. 2017). Calls have been made for examining not only area-level effects on tobacco use, (e.g., residential segregation (Moon, Pearce and Barnett 2012)), but also the social contexts, social practices, and meanings of tobacco use from the perspectives of smokers themselves (e.g., Blue et al. 2016, Poland et al. 2006, Frohlich et al. 2002, Glenn et al. 2017, Pearce et al. 2012).

Novel research methods could further propel tobacco research beyond identifying individual and area-level predictors of tobacco use to understanding the underlying mechanisms linking these to behavior. To this end, we present a novel mixed method for identifying and understanding the situational factors and place-based practices of substance use. We piloted the integration of geographically explicit ecological momentary assessment (GEMA) (Kirchner & Shiffman, 2016) with an adapted travel diary-interview method similar to those often employed in space-time geographical studies (e.g., Schwanen and De Jong 2008) to understand where and when individuals smoke, as well as how and why.

Ecological momentary assessment (EMA) methods employ “repeated collection of real-time data on subjects' behavior and experience in their natural environments,” (Shiffman et al. 2008, 3). This can be achieved through a variety of data collection tools, including written diaries, cell phones, electronic diaries, and physiological sensors with which participants report on factors such as their current state, activities, and observations of their surroundings. These momentary assessments are completed repeatedly over a pre-defined time period (e.g., a month) (Shiffman et al. 2008). While most tobacco surveillance studies ask participants to report global characterizations of their tobacco use (e.g., ‘How many cigarettes do you smoke per day on average?’), a key methodological advantage of EMA is that it largely avoids retrospective recall, which is systematically biased toward emotionally salient or unique experiences, dependent upon context and mood at the time of recalling events, and biased by cognitive heuristics used to summarize experience (Shiffman et al. 2008).

Tobacco use is particularly well-suited for study with EMA because it is an episodic behavior with discernable small-scale events thought to be related to mood and context as the individual goes about everyday life (Author 2015, Author 2017, Shiffman 2009, McCarthy et al. 2006, Ferguson and Shiffman 2011). Recently, the EMA method has been expanded by integrating Global Positioning System (GPS) tracking data; referred to as geographically explicit ecological momentary assessment (GEMA) (Epstein et al. 2014, Mitchell et al. 2014, Chow et al. 2017, Kirchner and Shiffman 2016). GEMA allows for spatial analyses of relationships such as those between participant self-reports (e.g., drug craving intensity), location types (e.g., home) and objective environmental ratings (e.g., neighborhood disorder).

GEMA is an ecologically strong approach to understanding tobacco use contexts because it conceives of an individual's interaction with their environment in terms of their activity space, meaning everywhere they actually spend time in everyday life in addition to their place of residence (e.g., commuting path, friends' homes, nightlife venues) (Shareck et al. 2015). However, because GEMA surveys must be kept short to reduce participant burden and encourage data collection compliance, they cannot capture the richness of individuals' experiences of smoking contexts and practices. These types of interactions between the individual and their activity space locations are key to understanding environmental influences on social or health outcomes (Mennis, Mason, & Cao, 2013), such as tobacco-related health disparities.

Space-time geography also takes an activity space approach, focusing on individuals' continuous paths through time and space in understanding human behavior and experience (Rainham et al. 2010). A qualitative space-time geographical approach may shed light on the experiential and relational dimensions missing from GEMA measures that interplay with how and why tobacco use folds into individuals' space-time paths.

Qualitative and mixed methods space-time geographical approaches have examined individuals' experiences of logistical constraints on their movements through time and space (e.g., limited reach in space due to reliance on public transit (Hernandez and Rossel 2015), juggling everyday activities (e.g., managing work demands alongside parenting activities (Schwanen 2008)), arrhythmias between the body and everyday environments (e.g., older age (Lager, Hoven and Huigen 2016)), and embodied experiences of everyday contexts that influence mobility (e.g., feeling unwelcome in a high-end store due to one's appearance (Author 2012)).

Similar to EMA diaries, participants in space-time geographical studies have used travel diaries in real time over a number of sample days to record information such as where they go, transportation modes, activities performed, and times of departure and arrival (e.g., Berg et al. 2014, Author 2017, Author 2017). These diaries guide subsequent interviews, prompting participants to recreate the sample days. This grounds discussion in participants' everyday contexts and encourages description of experiences, routines, and habits that participants might otherwise find too mundane or unremarkable to bring up. Travel diaries could be replaced by viewing and discussing maps of the participant's GEMA data, providing interviewer and interviewee the opportunity to reflect on spatial patterns of tobacco use and discuss experiential dimensions of tobacco use contexts and practices.

A growing body of research has integrated geographic information systems (GIS) with qualitative data and methods to explain the processes producing spatial patterns, knowledge, relationships, and interactions, and their resulting social and political impacts (Elwood & Cope, 2009). Some have used qualitative data and GIS as separate but complementary research components, as in the use of GPS tracking, ethnographic observation, and in-depth interviews (Naybor et al., 2016, see also Pavlovskaya, 2004). Others have visualized and interpreted qualitative data within a GIS software platform. For example, participants use the VERITAS web mapping application to mark activity space locations and trips and draw perceived neighborhood boundaries (Chaix et al., 2012). Meijering and Weitkamp (2016) merged information recorded in participant travel and activity diaries with the GPS tracking data, which informed the content discussed in subsequent interviews. Geo-narrative (Kwan, 2008; Kwan & Ding, 2008) uses GIS to visualize emotions associated with different times and locations along participants' daily space-time paths (e.g., colored red to illustrate fear), geo-references various qualitative data sources (e.g., memos and photos), and integrates basic qualitative data coding functions within GIS. Mennis and colleagues (2013) used structured interviews to collect data on participants' activity space locations, including perceptions of safety and risk in these places. They then visualized participants' perceptions, interpretations, and feelings about everyday locations with cartographic symbols.

One prior GEMA study incorporated a qualitative GIS approach (Pearson et al. 2016) consisting of a ‘place’ survey wherein research assistants sat with participants and geo-tagged their personal mobility maps with tobacco rules and norms for locations participants had visited. Additionally, some EMA studies have used qualitative methods, such as interviews, before or after EMA data collection to inform EMA study design or assess participant acceptability of data collection protocol (e.g., Attwood et al. 2017, Naughton et al. 2016, Brookie et al. 2017). To our knowledge, no prior study has employed a qualitative GIS mixed method design in which participants discuss and interpret maps of their GEMA data regarding reported behaviors (e.g., smoking) and experiences (e.g., nicotine cravings) during in-depth interviews.

We draw from a GEMA-interview mixed method pilot study to provide an in-depth exploration of three bisexual young adult smokers in the San Francisco Bay Area. Bisexual individuals are an exemplar group for studying tobacco-use disparities, as little is known about why tobacco use rates are higher nationally among bisexuals than heterosexual, gay, or lesbian individuals (Emory et al. 2016). Proposed explanations for elevated tobacco use among sexual and gender minorities as a group include the minority stress model (Blosnich et al. 2013, Meyer 2003), having smokers in one's peer network (Remafedi 2007), the role of bars in sexual and gender minority communities and the pleasure-enhancing relationship between alcohol and nicotine (Blosnich et al. 2013, McKee et al. 2004, Gubner et al. 2017), tobacco retail and marketing density in neighborhoods with concentrations of same-sex couples (Lee et al. 2016), and the targeting of sexual and gender minorities in tobacco marketing campaigns (Stevens, Carlson and Hinman 2004).

We aim to understand: 1) participants' spatial and temporal patterns of smoking and cravings; 2) situational factors and place-based practices driving patterns of smoking and cravings; and 3) how, if at all, bisexual identity interplays with situational factors and place-practices of smoking and cravings. We discuss the complementarity, strengths, and weaknesses of the mixed method and conclude with future directions for research and applications.

GEMA–Interview Mixed Method

Study design

We employed an explanatory sequential mixed method approach (Figure 1) (Curry and Nunez-Smith 2015, Onwuegbuzie and Teddlie 2003). Participants were recruited from a larger GEMA study of smokers ages 18-26 in Alameda and San Francisco Counties, California (n=145). Eligible participants smoked at least 100 cigarettes in their lifetime, currently smoked at least one cigarette per day at least three days per week, and owned and used daily a smartphone with GPS capabilities. Participants were recruited through Facebook and, to a lesser extent, Craigslist and LGBTQ youth serving organizations. Advertisements linked to the study's website with an eligibility questionnaire. If eligible, participants were taken to the informed consent webpage. In order to verify participants' identities, participants sent a picture of their ID.

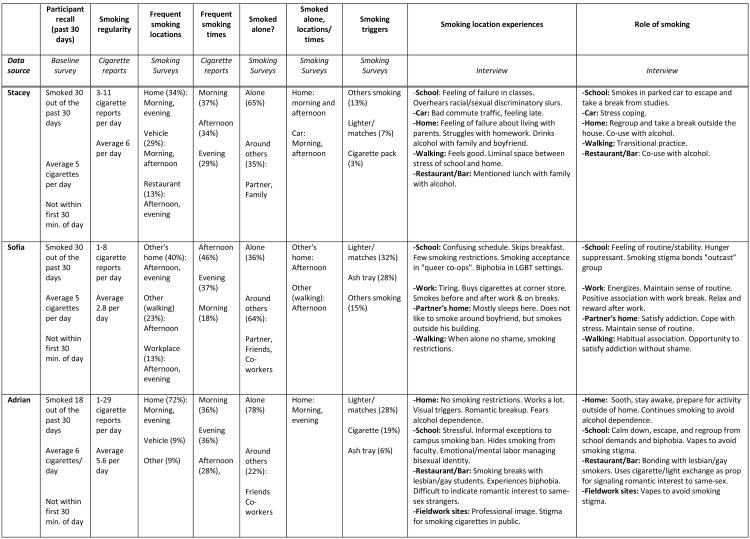

Figure 1. GEMA-interview mixed method study design.

For the mixed methods pilot, those with medium or high GEMA data compliance (completed >50% of prompted GEMA surveys) were recruited to ensure adequately rich GEMA data at the case level. Those who selected ‘bisexual’ and/or wrote in ‘pansexual’ or ‘queer’ on the baseline survey were selected for the mixed method pilot. We use ‘bisexual’ in this paper as short-hand for expressing attraction to one's own and other genders.

The resulting sample (n=17) was composed mostly of female young adults (ages 18-26) who all identified as bisexual, pansexual, and/or queer. Most identified as bisexual (76%) and cisgendered female (71%) with three gender queer individuals assigned female at birth and two cisgendered men. They were from a variety of socioeconomic backgrounds as determined by mother's highest education and a variety of racial/ethnic groups, although African Americans were under-represented.

Participants received up to $180 in incentives in the form of an Amazon Gift Card. Incentive amounts varied by participant compliance with the smartphone app administered surveys. Participants received $60 for completing the face-to-face interview.

First, GEMA data were collected using a smartphone app over a 30-day period. Then, qualitative data were collected, consisting of in-depth interviews guided by maps of participants' GEMA data that visualized their paths over the course of data collection and spatial patterns of smoking and cigarette craving reports. The interviews informed and interpreted the quantitative data in greater depth. The quantitative and qualitative data sets were analyzed separately and then integrated in a Mixed Method Matrix (O'Cathain, Murphy and Nicholl 2010). Quantitative and qualitative findings were discussed for each case. Then, we performed a qualitative cross case analysis to discover patterns across all cases regarding the situational factors and place-based practices driving smoking patterns, as well as the role of bisexual identity. Ethics approval for this study was granted by [INSERT UNIVERSITY NAME] Institutional Review Board.

Geographically Explicit Ecological Momentary Assessment (GEMA) smartphone method

Participants completed a baseline survey on an online survey platform (Qualtrics) regarding basic demographics, smoking history, and current behavior. GEMA data were collected using the PiLR Health platform (pilrhealth.com). Participants used their own smartphones and the study app to collect data on non-smoking and smoking situations over 30 days. The study app collected continuous location sensor data throughout the data collection period (we aimed for a data point every two minutes; in reality, the frequency varied across phone operation systems (Android vs. iOS), OS version, and phone type). Participants were instructed to report every time they smoked a cigarette (cigarette reports). A random subset of up to a maximum of three of these cigarette reports each day triggered a survey prompt (smoking surveys). The likelihood for a cigarette report to trigger a smoking survey was adjusted according to the participant's baseline smoking rate. Participants were also prompted at random three times per day (random surveys) to complete a survey to allow for assessment of non-smoking as well as smoking situations. These procedures are consistent with those previously reported in the literature (Jahnel et al., 2017, Shiffman et al., 2002, Shiffman & Paty, 2006). Researchers could access the GEMA platform backend and download participant data.

Smoking survey and random survey questions were developed from the literature and our previous studies (Author 2014, Author 2015, Cronk and Piasecki 2010, Kirchner et al. 2013). Questions examined aspects of each sampled situation that were both internal and external to the individual. For example, to capture ‘internal’ factors, participants were prompted to report their mood and intensity of their cigarette craving. For ‘external’ factors, participants reported what type of location they were in, if they were drinking or eating, and if specific smoking triggers, such as others smoking, ashtrays, or tobacco advertisements, were present, for example. The number of survey questions was limited to prevent interference with participants' daily activities. The GEMA software automatically logged participants' responses with GPS coordinates for every completed survey to collect a location data point exactly when the survey was submitted. All data were time and date-stamped to allow for temporal analysis of smoking behavior.

GEMA data were descriptively analyzed using Stata 14 (StataCorp 2015). For the present analysis, cigarette reports and smoking surveys were examined, focusing on smoking locations, times of high frequency of smoking at each location, presence of others, and reports of specific smoking triggers (e.g., ashtrays, cigarette packs). Baseline survey data were used to compare and contrast the GEMA data with how participants globally recall and report their smoking behavior.

Map-interview method

GEMA data were visualized in ArcGIS upon completion of the GEMA data collection period for each participant. Map layers were created to visualize where participants went during the data collection period (using location sensor data), where they had reported high cravings for tobacco (using smoking survey and random survey data), and where they had reported smoking (using cigarette report data). Map layers were made for the entire 30-day GEMA data collection period, one weekday, and one weekend day as close to the interview date as possible to increase the likelihood that participants could recall the experiences and events of those two sample days.

Interviews were held within a few days of GEMA data completion. The first author conducted the interviews, which lasted about an hour. During interviews, the participant was shown the map layers of high cravings, cigarette reports, and location sensor data on a laptop in Google Earth. The interviewer toggled between the map layers to reveal differences in spatial patterns (e.g., areas where the participant had frequently reported high cravings but not many cigarette reports). The participant was invited to explore the data by zooming in and out and panning over the maps. The interviewer prompted the participant to discuss apparent spatial clusters of reported smoking and high cravings as well as places where they had spent time but did not report these tobacco use experiences and behaviors. This encouraged discussion regarding the locations, times, triggers, situational experiences, and routines linked to the use of and craving for tobacco in everyday life. Then, the maps of two recent sample days were shown. The participant was asked to ‘lead’ the interviewer through each sample day, providing such vivid ‘play-by-play’ detail of their activities, movements, and experiences, including tobacco use and craving episodes, that someone could make a movie of their day. Participants spontaneously compared or were asked to compare and contrast the events of those sample days with their ‘usual routine.’

Interviews were audio recorded, transcribed verbatim, and coded by the first author in Dedoose qualitative analysis software (SocioCultural Research Consultants 2015). Memos of initial impressions of the data were kept throughout data collection and initial coding. Analysis aimed at identifying the situational factors and place-based practices of smoking driving the spatial and temporal patterns of smoking identified in the GEMA maps and descriptive analysis, and to reveal how, if at all, bisexual identity interplays with these situational factors and place-based practices. Thematic analysis followed an integrative inductive-deductive approach (Bradley, Curry and Devers 2007). The initial coding list was developed from domains from the GEMA surveys to facilitate integration of the qualitative and quantitative data at the case level: smoking location types (e.g., home, car), smoking episodes, and cravings for cigarettes. Then, excerpts concerning smoking episodes and cravings were re-examined by location type to identify emergent themes regarding the experiences driving smoking and cravings in each location (e.g., experiences of marginalization due to sexual identity; feeling fatigue) and the role of tobacco in these situations (e.g., escape; impose a break and energize).

Data integration

Following independent data analysis of the quantitative and qualitative data sets, the first and second authors met to discuss their findings for three cases. This provided discoveries of where findings were in disagreement or alignment, weaknesses in each method, and where one method complemented the other. It also provided an opportunity to follow a thread of interest (O'Cathain et al. 2010) from one data set to the other. For example, if a dramatic shift in a participant's cigarette consumption pattern was observed in the GEMA data, the transcript could be searched for content to explain this shift. The first author kept memos regarding these observations throughout the findings presentation and discussion process. The GEMA and map-interview findings were then integrated for each case in a Mixed Method Matrix (O'Cathain et al. 2010). The rows represented each case and the columns contained findings from the baseline survey, cigarette reports, smoking surveys, and interviews.

Exploring three cases

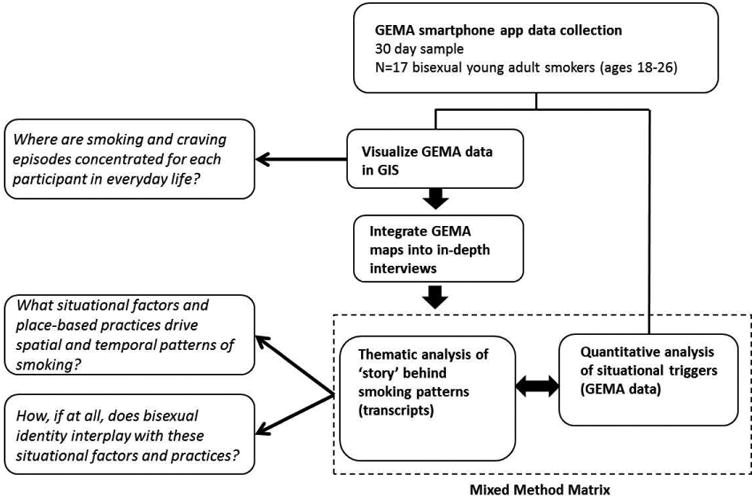

Figure 2 depicts an abbreviated version of the Mixed Method Matrix. Data sources are listed in the second row. We explore these cases below, focusing on what each method brought to our understanding of each case, methodological weaknesses that emerged in analysis, and ways in which the GEMA and map-interview methods complemented one another. Pseudonyms were assigned to each case, some participant details were changed, and maps of participant data are displayed without georeferencing information such as streets and landmarks to protect participant confidentiality.

Figure 2. Mixed Method Matrix, Three Cases.

Stacey

Stacey is a White, non-Hispanic, cisgendered, bisexual woman in her mid-20's. She lives at home with her parents in an outer suburb and is studying full-time at a community college. In the baseline survey, she reported being a daily smoker, smoking five cigarettes per day on average, and never smoking within the first 30 minutes of waking (an indicator of nicotine dependence) (Shiffman et al. 2008).

The GEMA data provided a more reliable and contextualized picture of Stacey's smoking behavior. Her GEMA data showed she smoked slightly more per day than reported in her baseline survey. She smoked most frequently at home, in her vehicle, and at restaurants/bars, during the morning, afternoon, and slightly less in evenings. She usually smoked alone, overwhelmingly so while in her car and to a large extent while at home. Her smoking did not seem driven by seeing other smokers (Remafedi 2007), or by common visual triggers for smoking, such as tobacco advertising (Stevens et al. 2004, Lee et al. 2016). What, then, drove Stacey's smoking within the times and places she smoked most?

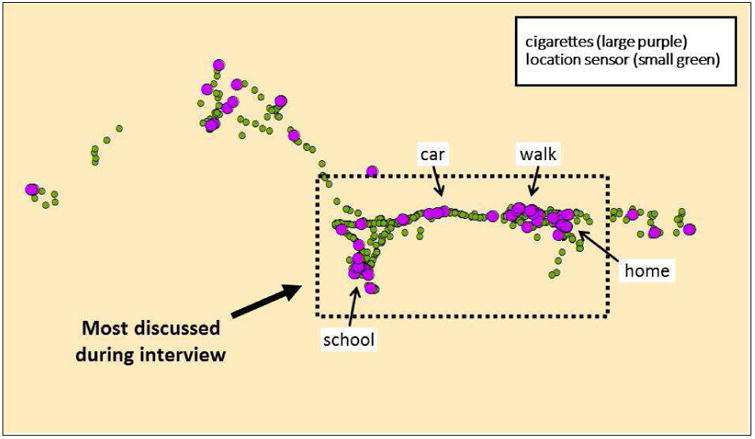

The map-interview revealed the experiences and smoking practices embedded within Stacey's frequent smoking locations and times. The locations most relevant to her smoking did not entirely match those identified by her GEMA data (home, vehicle, restaurant/bar). Contrary to Stacey's craving and cigarette report maps, the most intensively discussed locations were school, car, home, walking, and to a lesser extent restaurants/bars. The GEMA data did not indicate ‘school’ or ‘walking’ as frequent smoking locations, and a restaurant was only discussed fleetingly during the interview in reference to a family lunch. The integration of findings from both methods allowed us to obtain a clearer and more nuanced picture of Stacey's smoking behavior in several ways.

First, the interview revealed an additional meaning of ‘smoking in the car’ obscured in the smoking survey data. While reasonable interpretation of the smoking survey data suggests she smoked a lot while driving, the interview clarified that she also smoked frequently in her car while parked at school (discussed in more detail below). Therefore, a substantial number of cigarettes reported as smoked in her ‘car’ in the smoking surveys might more accurately be reported as ‘school’.

Second, the discrepancy between the most relevant smoking locations may also be due to recall bias toward intensely emotional experiences (Shiffman et al. 2008). While restaurants/bars are one of Stacey's top three most frequent smoking locations on surveys, they were likely glossed over during the interview because Stacey's smoking practices in other locations - school, car, home, and while walking -were associated with more emotionally compelling experiences (Map 1).

Map 1. Stacey's smoking reports and location sensor data, 30 days.

Stacey described intensely negative experiences linked to smoking at school, in her car, and at home, while smoking while walking was experienced as largely positive. At school, Stacey experiences failure in her classes. She overhears students using racial and homophobic slurs and biphobic comments from her lesbian and gay peers both at school and at parties and events. Smoking provides her with a reason to physically escape this negatively experienced environment, as smoking is restricted to the school parking lot. While driving to and from school, she chain smokes to cope with “miserable” commute traffic. At home, she feels like a failure for having moved back in with her parents. She struggles with homework and drinks alcohol with her family and boyfriend. She steps outside the house to smoke, take a break and regroup, and is also likely driven in her smoking by co-use with alcohol. While walking dogs in her neighborhood after school, however, smoking is a distinctly positive experience. She experiences this time between school and home as a liminal space. Smoking becomes a transitional practice with which to “turn the page” on her day.

In short, the GEMA data complemented the interview by compensating for participant discounting of seemingly unremarkable events (e.g., smoking at restaurants/bars) and recall bias toward emotionally powerful experiences. The map-interview complemented the GEMA by clarifying the meaning of locations reported in smoking surveys (e.g., the parked car as a cocooned environment at school), and provided insight into the experiences and place-based practices that help explain why Stacey smokes most frequently in particular places and at particular times, including concrete smoking experiences related to minority stress (Blosnich et al. 2013) and intragroup marginalization (Callis 2013) as a bisexual.

Sofia

Sofia is an Hispanic, cisgendered, bisexual woman in her late teens. While her smoking surveys showed both cigarettes and a small amount of smokeless tobacco (e.g., chew) use, she clarified during the interview that the smokeless tobacco reports were app user error. She lives in a university dorm in an urban environment, studying full-time and working full-time.

In the baseline survey, Sofia reported being a regular smoker, smoking five cigarettes per day on average, and never smoking within the first 30 minutes of the day. Her cigarette report data indicated fewer cigarettes per day than indicated in the baseline survey. As the interview did not indicate a shift from her usual smoking pattern, she may have under-reported her cigarette consumption during GEMA data collection. She smoked most often at someone else's home, an ‘other location’ she wrote-in as ‘walking’, and at work, mostly in the afternoon and evening. When she smoked she was most often around others; usually her boyfriend, friends, or co-workers. Relevant visual smoking triggers for Sofia were seeing lighters/matches, an ash tray, and others smoking. In short, the GEMA data suggests Sofia smokes most often at someone else's home, while walking, and at work, in the afternoon and evening. Seeing tobacco paraphernalia and often being around other smokers may be driving her cigarette use.

The map-interview described Sofia's experiences and smoking practices within the same locations identified by the GEMA method (other's home, walking, workplace). It also added the relevance of her school experience, including her difficulties juggling everyday activities and how this interplays with smoking. Sofia often has troubles keeping track of her work and class schedule and skips breakfast. Her cigarette consumption increased dramatically within a week of moving out of her family home into the university environment. Informal exceptions to the university campus smoking ban and the absence of family disapproval means she can “smoke whenever I want”. Smoking is a hunger suppressant and provides her with a momentary sense of calm and a portable practice with which to impose rhythmic regularity and a sense of routine on her complex work-school schedule (see also Blue et al. 2016).

The interview revealed that the ‘other's home’ location reported in the smoking surveys is her non-smoker boyfriend's home where she sleeps most nights and smokes outside of his building. Her full-time food service job is located next to a corner store where she buys cigarettes. She smokes before and after work and on breaks. Smoking gives her energy when she is tired and she associates it positively with being on break and rewarding herself after work. While walking alone between work, classes, and her and her boyfriend's homes, Sofia can smoke without feeling ashamed in front of her non-smoker friends and boyfriend. She identified a strongly habitual relationship between stepping outside alone to walk somewhere with reaching for her cigarette pack.

In short, the smoking locations discussed in Sofia's interview matched those identified in the smoking surveys, offering a smooth flow from the quantitative GEMA findings regarding Sofia's spatial patterns of smoking to in-depth qualitative findings regarding her experiences and place-based practices within smoking locations.

Adrian

Adrian is a Latino, cisgendered, bisexual man in his early 20's. He is in graduate school and active in LGBTQ+ organizing. Adrian smokes cigarettes and uses a nicotine vaporizer (“vape pen”). He lives in an urban environment in an apartment with one housemate. Adrian reported smoking 18 out of the past 30 days on his baseline survey, with an average of six cigarettes per day. Like Stacey and Sofia, he did not report smoking upon waking. His average daily cigarette consumption recorded with the GEMA app was comparable to the baseline survey.

Adrian's cigarette reports showed wide consumption fluctuation over the data collection period (range: one to 29 cigarettes per day), reporting far fewer cigarettes in the first two weeks of data collection than in the final two. While this could indicate user or functional app error, the interview revealed that he went through a romantic breakup and unexpected school demands that precipitated the smoking surge. While the cigarette reports were therefore likely reflective of his actual use, the ‘binge’ posed a serious challenge for the GEMA method. Because the smoking surveys were triggered in anticipation of a lower number of cigarettes per day and capped at a maximum number of three, the smoking surveys collected for this participant in the second half of the data collection period are more reflective of morning smoking episodes. Therefore, the smoking survey data cannot reliably speak to situational factors of smoking later in the day.

The morning-focused smoking survey data suggested Adrian smoked mostly at home. However, cigarette reports showed he smoked fairly evenly across the day, suggesting greater diversity in smoking locations. Overwhelmingly, smoking surveys indicated he smoked alone, and if not alone, around friends, co-workers, or acquaintances. At home, he mostly smoked alone and in the morning and evening. Based on the question about specific smoking triggers, two visual triggers seemed relevant to Adrian: seeing lighters/matches and cigarettes.

The interview helped balance the morning-biased picture created by the smoking surveys. As in the smoking surveys, home was discussed as the most important smoking location. Other smoking locations were school, fieldwork, LGBTQ+ organizing sites, and restaurants/bars. Vehicles were mentioned only in passing. Home is where Adrian does most of his graduate and LGBTQ+ organizing work. While he conceals smoking in other settings, at home he leaves visual triggers such as lighters lying around. He and his roommate do not have tobacco restrictions for the apartment. Adrian smokes while he works, to stay up at night, and feel “more at ease” for upcoming outside activities (e.g., public speaking). Home was also primarily where he grieved his romantic relationship. Adrian fears that if he quits nicotine during a stressful time he will drink too much alcohol. As such, his continued nicotine use is a strategy for avoiding what he perceives as more concerning substance use.

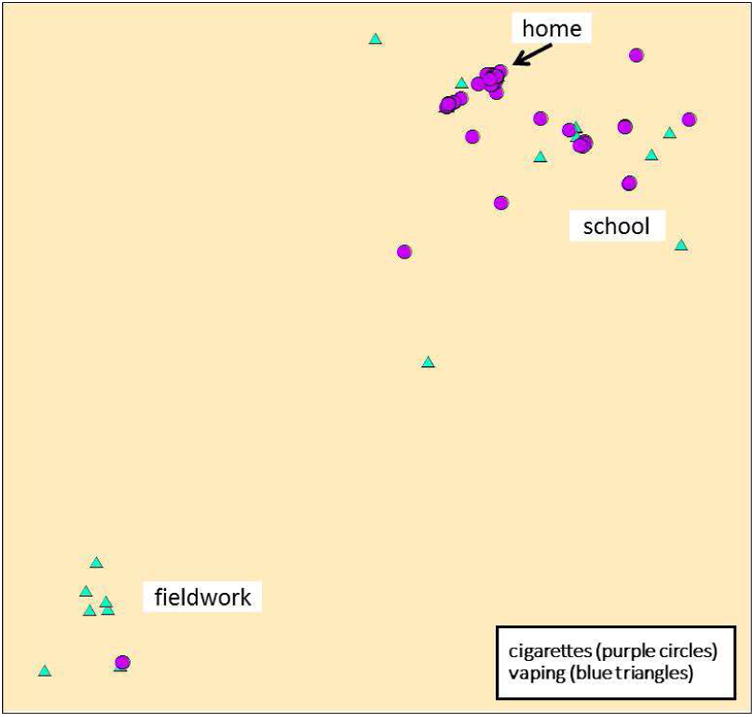

Adrian discussed graduate fieldwork and LGBTQ+ organizing sites during the interview; most likely the ‘other’ locations reported in the smoking surveys. Adrian's maps of cigarette and vaping reports showed contrasting spatial patterns of consumption for the two tobacco products (Map 2). This prompted discussion regarding the situations in which Adrian uses one tobacco product over the other. He explained that university, fieldwork, and LGBTQ+ organizing places are “areas of high investment” where he wants to create a professional image and do “damage control” against smoker stigma, unlike home where he freely smokes cigarettes. Adrian finds vaping to be more socially acceptable and therefore tries to either hide cigarette consumption or vape in “high investment” places.

Map 2.

Cigarette and vaping reports selection, 30 days, Adrian

At university, Adrian manages his bisexual identity as well as his professional image. He described feeling that his bisexual identity is “interrogated” by lesbian and gay graduate cohort members. He feels he must perform a “trapeze line walk” as a bisexual man in order to be accepted as an organizer in the LGBTQ+ community and not be perceived as a “predator” by lesbian/bisexual women, all the while without negating the aspect of his identity that involves attraction to women. Within straight spaces, he tries not to be perceived as gay. He describes this performative identity management as “emotional/mental labor” from which smoking helps him calm down, escape, recharge, and regroup in the moment.

Finally, the interview shed light on an important evening smoking location not adequately captured in Adrian's smoking surveys: restaurants/bars. Adrian frequently attends happy hours at bars where he smokes outside with his lesbian and gay graduate cohort members. Discovering that they smoke was a bonding point for them. Adrian also finds smoking provides a prop for initiating interaction with strangers of the same sex. While he finds women more readily interpret contact from unknown men as an indication of romantic interest, Adrian finds it harder to communicate interest to other men by simply starting a conversation. He finds that exchanging a cigarette or light facilitates physical proximity and exchange of something of value.

In short, the integration of the interview with the GEMA data confirmed that Adrian's smoking pattern did shift dramatically over the final two weeks of data collection. While this challenged the reliability of the smoking survey data regarding situational factors associated with cigarettes smoked later in the day, the interview helped compensate for this by providing insight into the experiences and smoking practices of evening smoking locations (e.g., bars). Viewing the maps of cigarette and vaping reports during the interview sparked discussion that may not have otherwise arisen regarding the participants' contextually-dependent use of different tobacco products.

Discussion

This paper presented a mixed method combining geographically explicit ecological momentary assessment (GEMA) and an adaptation of the travel diary-interview method often employed in space-time geography, exploring three cases of bisexual young adult smokers. The integration of a qualitative GIS approach with GEMA is a contribution to GEMA studies (Epstein et al. 2014, Pearson et al. 2016, Mitchell et al. 2014, Chow et al. 2017, Kirchner and Shiffman 2016) and mixed methods space-time geographical approaches (Schwanen and De Jong 2008, Naybor et al. 2016). Together, these methods identified each participants' most frequent smoking locations/times (e.g., afternoons on university campus) and associated situational factors (e.g., seeing tobacco paraphernalia). It revealed participant experiences of smoking locations/times (e.g., peer rejection of bisexual identity at school) and the role of tobacco use therein (e.g., physically escape uncomfortable environments). These exploratory findings suggest the potential to illuminate how smoking as a practice is embedded and perpetuated within the everyday contexts of individuals' lives, identifying pathways between the characteristics and social contexts of where they live, their individual attributes, and their smoking behavior (Pearce et al. 2012, Poland et al. 2006, Frohlich et al. 2002). They suggest the ability to describe the spatio-temporal patterns of smoking practices, as well as the materiality, competencies, and meanings that fold into their reproduction in everyday life (Blue et al. 2016).

The inductive advantages of visualizing and exploring self-reported data with participants can help generate hypotheses about the contexts of health behaviors (Mennis et al. 2013), such as how and why in everyday life smoking is linked to stress for marginalized groups (Blosnich et al. 2013, Meyer 2003). It may provide a window into the concrete everyday situations in which the stresses of having a stigmatized or minority status manifest and provide the practice of smoking with meaning and utility for the individual. More practical contributions may include identifying for a particular group the most relevant places for tobacco intervention outreach, the situational factors and experiences of smoking most important to address in cessation support and counseling materials, and the unique smoking practice-related experiences that must be acknowledged in order to engage individuals with tobacco prevention messages and treatment.

Strengths

The integration of the GEMA and map-interview methods demonstrated several advantages in understanding participants' everyday contexts and practices of smoking. One was in providing opportunities for confirmation of findings (O'Cathain et al. 2010). For example, Adrian's cigarette ‘binge’ in the second half of his GEMA data collection period appeared at first due to either participant compliance or app functioning, but was confirmed by the interview as a credible representation of his consumption pattern. Furthermore, analyzing both data sets by smoking location offered opportunities for confirmation of the most relevant locations for each participant from both the cumulative perspective of the GEMA data and the global perspective of the participant, as observed in Sofia's GEMA and interview data where smoking locations mapped onto each other. We also observed confirmation regarding visual smoking triggers. For example, Adrian's GEMA data suggested tobacco paraphernalia (e.g., lighters) as one of his smoking triggers and he described feeling encouraged to smoke more by seeing these objects around his apartment.

The GEMA and map-interview methods complemented one another by helping compensate for independent methodological weaknesses. The GEMA data helped balance the autobiographical recall bias inherent to the interview method (Shiffman et al. 2008). Stacey only mentioned smoking in restaurants and bars in passing during the interview despite these being identified as important by the GEMA data. This would suggest that her experiences in these locations are less remarkable to her than in locations where her smoking practices are embedded in more emotionally compelling experiences. Without the GEMA data, this smoking location would have gone largely unnoticed in our analysis of this case.

The convenience of the GEMA data collection by smartphone app allowed for a longer sampling period than feasible with traditional travel diaries, which are most often only collected for a week or less. This provided a more reliable impression of each participant's ‘typical’ tobacco use patterns while still providing map layers for ‘play-by-play’ discussion of individual sample days. Integration of GEMA maps into the interview prompted discussion of content that may not have otherwise come up. For example, Adrian's cigarette and vape pen use map layers showed distinct spatial patterns of use, prompting a discussion on how he uses one tobacco product over the other depending on the place and situation.

The interview provided clarification regarding participants' interpretations of the GEMA survey measures, the descriptions of which are necessarily brief in the GEMA surveys. For example, the interviews revealed two ‘car’ location meanings for Stacey, clarified that Sofia's ‘other's home’ location was her boyfriend's home, and that Adrian's ‘other’ locations were likely graduate fieldwork and LGBTQ+ organizing sites. The interview provided in-depth understanding of the ways in which participants experience smoking locations and the meanings and functions of smoking in these locations. The participant accounts presented here revealed dimensions of their social contexts of smoking (Poland et al. 2006), such as experiences of minority stress and intragroup marginalization, and the role and meanings of tobacco use in those situations (Blue et al. 2016). This level of understanding is not possible to glean from multiple choice, pre-defined responses in GEMA surveys.

Finally, while the GEMA method is designed to assess moment-to-moment factors of interest, the interview provided more holistic understanding of how participants experience everyday life, including the juggling of activities and sequencing of events. Part of the function of smoking for Sofia, for example, is to provide a portable, stable rhythm that she can impose on her hectic schedule. Stacey's transitional practice of smoking while walking dogs after school is given meaning and function by her experience of the sequence of contexts and activities along her daily space-time path (Schwanen 2006).

Limitations

Several limitations in this mixed-method approach became apparent while exploring the three cases. On a practical level, the integration of the GEMA and interview data at the case level is time consuming, requiring team discussion of individual cases. This presents a challenge to scaling up analysis for a larger sample size, especially one large enough for statistical analyses across cases (O'Cathain et al. 2010). Furthermore, while interviewing only those participants who achieve medium or high data collection compliance throughout the GEMA sampling period ensures high quality GEMA data at the case level, this may bias participant selection toward those who are more conscientious or able to engage with data collection protocol.

The full range of contextual factors influencing smoking practices may not all be reliably detected and reported by study participants (Kirchner and Shiffman 2016). Both the GEMA and map-interview methods rely upon participants' awareness and perception of their surroundings and actions, as well as their ability and willingness to comply with the GEMA data collection procedures and engage in the interview process. Some place characteristics relevant to tobacco use, such as racial and ethnic segregation and area-level deprivation (e.g., Moon et al. 2012), may not be adequately captured in this way. Future studies could integrate area-level characteristics into the GEMA-interview method with using an activity space approach (Epstein et al., 2014). Relatedly, all measures used in this study, except for GPS data, relied on participant self-reports and may thus be impacted by social desirability bias. As smoking is increasingly stigmatized and subject to social norms that discourage cigarette use (Graham 2012), participants may underreport their smoking behavior in both GEMA surveys and interviews. Computerized assessments have shown to decrease social desirability bias compared to in-person interviews (Booth-Kewley, Larson and Miyoshi 2007), which may point to an advantage of using the method to guide follow-up interviews. It should be noted that previous studies using data collection procedures similar to the current investigation have found strong correlations between cigarette reports and biochemically verified breath carbon-monoxide (Shiffman & Paty, 2006). Passive tracking of smoking episodes, for example by using wearable sensors (Sazonov, Lopez-Meyer and Tiffany 2013), could bypass potential self-report biases completely.

The GEMA method appears compromised by large fluctuations or changes in tobacco use over the data collection period, as demonstrated by Adrian's ‘binge’ in the second half of his data collection period. The sampling of tobacco use episodes by using a fixed likelihood of sampling each smoking occasion means that sampled smoking situations are skewed toward early in the day during periods of significant increase from the participant's baseline use patterns. This methodological weakness was only partially compensated for by the interview discussion of Adrian's evening tobacco use situations. These findings are in line with previous studies reporting a high variability in cigarettes smoked per day among a substantial subset of smokers (e.g., Hughes et al. 2017). In fact, variability may be even more pronounced among light and intermittent smokers (Shiffman et al. 2012), which is consistent with the smoking behavior reported by Adrian. Results suggest that a different GEMA sampling approach may be needed to survey a representative subset of smoking occasions for participants with highly variable day-to-day smoking patterns.

Finally, while Stacey, Adrian, and Sofia's accounts draw tentative links between tobacco use and experiences of social exclusion as bisexuals, this pilot study did not include measures of discrimination in the GEMA surveys. Future studies could incorporate explicit measures of social exclusion experience in GEMA surveys to further investigate this topic. Future studies could also better hone in on issues relevant to bisexuals by including a non-bisexual comparison group.

Conclusion

This GEMA-interview mixed method shows potential for revealing the richness of individuals' experiences of everyday contexts and practices while providing reliable measures of situational factors associated with health behaviors, such as substance use. These types of findings can aid in generating hypotheses that may be tested with other methods on larger samples to explain health disparity-related behaviors, such as tobacco use among minority groups. The method may also inform the development of tailored health interventions to reduce health disparities, such as tobacco cessation smartphone apps, online cessation groups, and curriculum for cessation counselors and lay health workers. Future studies could integrate exposure to area-level characteristics into this mixed-method using an activity space approach. Social exclusion measures could be integrated into the GEMA surveys to better capture potential relationships between substance use and experiences of marginalization. GEMA-interview mixed methods such as this could provide in-depth understandings of a variety of health behaviors, including the consumption of different substances (e.g., marijuana, alcohol, opioids) independently or in co-use situations within a variety of populations.

Research highlights.

We describe a novel mixed method for understanding substance use behavior

Mobile tobacco use surveys and GPS data were mapped and guided interviews

Reliable measures of situational factors associated with smoking were collected

Participant experiences of smoking contexts and practices were revealed

In-depth findings on marginalized smokers may inform tailored tobacco interventions

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the participants of this study, the helpful suggestions of the two anonymous reviewers, Galen Joseph and Janice Tsoh for feedback on earlier manuscript versions, and Carson Benowitz-Fredericks for research coordination. Financial support was received from the National Cancer Institute (T32 CA113710; U01 CA154240) and the California Tobacco-Related Disease Research Program (TRDRP 25FT-0009).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Julia McQuoid, Center for Tobacco Control Research and Education, University of California, San Francisco, 530 Parnassus Ave, Suite 366, San Francisco, California 94143.

Johannes Thrul, Bloomberg School of Public Health, Johns Hopkins University, 624 N. Broadway, Baltimore, Maryland 21205.

Pamela Ling, Center for Tobacco Control Research and Education, University of California, San Francisco, 530 Parnassus Ave, Suite 366, San Francisco, California 94143.

References

- Attwood S, Parke H, Larsen J, Morton KL. Using a mobile health application to reduce alcohol consumption: A mixed-methods evaluation of the drinkaware track & calculate units application. BMC Public Health. 2017;17:394. doi: 10.1186/s12889-017-4358-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnett R, Moon G, Pearce J, Thompson L, Twigg L. Smoking Geographies: Space, Place and Tobacco Chichester. West Sussex: John Wiley & Sons; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Berg J, Levin L, Abramsson M, Hagberg JE. Mobility in the transition to retirement – The intertwining of transportation and everyday projects. Journal of Transport Geography. 2014;38:48–54. [Google Scholar]

- Blosnich J, Lee JGL, Horn K. A systematic review of the aetiology of tobacco disparities for sexual minorities. Tobacco Control. 2013;22:66–73. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2011-050181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blue S, Shove E, Carmona C, Kelly MP. Theories of practice and public health: Understanding (un) healthy practices. Critical Public Health. 2016;26:36–50. [Google Scholar]

- Booth-Kewley S, Larson GE, Miyoshi DK. Social desirability effects on computerized and paper-and-pencil questionnaires. Computers in Human Behavior. 2007;23:2093–2093. [Google Scholar]

- Bradley EH, Curry LA, Devers KJ. Qualitative data analysis for health services research: Developing taxonomy, themes, and theory. Health Services Research. 2007;42:1758–1772. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2006.00684.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brookie KL, Mainvil LA, Carr AC, Vissers MCM, Conner TS. The development and effectiveness of an ecological momentary intervention to increase daily fruit and vegetable consumption in low-consuming young adults. Appetite. 2017;108:32–41. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2016.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callis AS. The black sheep of the pink flock: Labels, stigma, and bisexual identity. Journal of Bisexuality. 2013;13:82–105. [Google Scholar]

- Chaix B, Kestens Y, Perchoux C, Karusisi N, Merlo J, Labadi K. An interactive mapping tool to assess individual mobility patterns in neighborhood studies. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2012;43(4):440–450. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chow PI, Fua K, Huang Y, Bonelli W, Xiong H, Barnes LE, Teachman BA. Using mobile sensing to test clinical models of depression, social anxiety, state affect, and social isolation among college students. Journal of Medical Internet Research. 2017;19:e62. doi: 10.2196/jmir.6820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cronk NJ, Piasecki TM. Contextual and subjective antecedents of smoking in a college student sample. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2010;12:997–1004. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntq136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curry L, Nunez-Smith M. Mixed methods in health sciences research: A practical primer. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Elwood S, Cope M. Introduction: Qualitative GIS: Forging mixed methods through representations, analytical innovations, and conceptual engagements. In: Cope M, Elwood S, editors. Qualitative GIS: A Mixed Methods Approach. London: SAGE Publications Ltd; 2009. pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Emory K, Kim Y, Buchting F, Vera L, Huang J, Emery SL. Intragroup variance in lesbian, gay, and bisexual tobacco use behaviors: Evidence that subgroups matter, notably bisexual women. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2016;18:1494–1501. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntv208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein DH, Tyburski M, Craig IM, Phillips KA, Jobes ML, Vahabzadeh M, Mezghanni M, Lin JL, Furr-Holden CDM, Preston KL. Real-time tracking of neighborhood surroundings and mood in urban drug misusers: Application of a new method to study behavior in its geographical context. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2014;134:22–29. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson SG, Shiffman S. Using the methods of ecological momentary assessment in substance dependence research—Smoking cessation as a case study. Substance Use & Misuse. 2011;46:87–95. doi: 10.3109/10826084.2011.521399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frohlich KL, Mykhalovskiy E, Poland BD, Haines-Saah R, Johnson J. Creating the socially marginalised youth smoker: The role of tobacco control. Sociology Of Health & Illness. 2012;34:978–993. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9566.2011.01449.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frohlich KL, Potvin L, Chabot P, Corin E. A theoretical and empirical analysis of context: Neighbourhoods, smoking and youth. Social Science & Medicine. 2002;54:1401–1417. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(01)00122-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glenn NM, Lapalme J, McCready G, Frohlich KL. Young adults' experiences of neighbourhood smoking-related norms and practices: A qualitative study exploring place-based social inequalities in smoking. Social Science & Medicine. 2017;189:17–24. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham H. Smoking, stigma and social class. Journal of Social Policy. 2012;41:83–99. [Google Scholar]

- Gubner NR, Thrul J, Kelly OA, Ramo DE. Young adults report increased pleasure from smoking cigarettes when drinking alcohol but not when using marijuana. Addiction Research & Theory. 2017:1–6. doi: 10.1080/16066359.2017.1311877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez D, Rossel C. Inequality and access to social services in latin america: Space–time constraints of child health checkups and prenatal care in montevideo. Journal of Transport Geography. 2015;44:24–32. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes J, Shiffman S, Naud S, Peters EN. Day-to-day variability in self-reported cigarettes per day. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2017;19:1107–1111. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntx057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jahnel T, Ferguson SG, Shiffman S, Thrul J, Schüz B. Momentary smoking context as a mediator of the relationship between SES and smoking. Addictive Behaviors. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2017.12.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirchner TR, Cantrell J, Anesetti-Rothermel A, Ganz O, Vallone DM, Abrams DB. Geospatial exposure to point-of-sale tobacco: Real-time craving and smoking-cessation outcomes. American Journal Of Preventive Medicine. 2013;45:379–385. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2013.05.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirchner TR, Shiffman S. Spatio-temporal determinants of mental health and well-being: Advances in geographically-explicit ecological momentary assessment (GEMA) Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2016;51:1211–1223. doi: 10.1007/s00127-016-1277-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwan MP. From oral histories to visual narratives: Re-presenting the post-September 11 experiences of the Muslim women in the USA. Social & Cultural Geography. 2008;9(6):653–669. doi: 10.1080/14649360802292462. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kwan MP, Ding G. Geo-narrative: extending geographic information systems for narrative analysis in qualitative and mixed-method research. Professional Geographer. 2008;60 doi: 10.1080/00330120802211752. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lager D, Hoven BV, Huigen PP. Rhythms, ageing and neighbourhoods. Environment and Planning A. 2016;48:1565–1580. [Google Scholar]

- Lee JGL, Griffin GK, Melvin CL. Tobacco use among sexual minorities in the USA, 1987 to May 2007: A systematic review. Tobacco Control. 2009;18:275–282. doi: 10.1136/tc.2008.028241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JGL, Pan WK, Henriksen L, Goldstein AO, Ribisl KM. Is there a relationship between the concentration of same-sex couples and tobacco retailer density? Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2016;18:147–155. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntv046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy DE, Piasecki TM, Fiore MC, Baker TB. Life before and after quitting smoking: An electronic diary study. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2006;115:454. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.115.3.454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKee SA, Hinson R, Rounsaville D, Petrelli P. Survey of subjective effects of smoking while drinking among college students. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2004;6:111–117. doi: 10.1080/14622200310001656939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meijering L, Weitkamp G. Numbers and narratives: Developing a mixed-methods approach to understand mobility in later life. Social Science & Medicine. 2016;168(Supplement C):200–206. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mennis J, Mason MJ, Cao Y. Qualitative GIS and the visualization of narrative activity space data. International Journal of Geographic Information Science. 2013;27 doi: 10.1080/13658816.2012.678362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer IH. Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychological Bulletin. 2003;129:674. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell JT, Schick RS, Hallyburton M, Dennis MF, Kollins SH, Beckham JC, McClernon FJ. Combined ecological momentary assessment and global positioning system tracking to assess smoking behavior: A proof of concept study. Journal of Dual Diagnosis. 2014;10:19–29. doi: 10.1080/15504263.2013.866841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moon G, Pearce J, Barnett R. Smoking, ethnic residential segregation, and ethnic diversity: A spatio-temporal analysis. Annals of the Association of American Geographers. 2012;102:912–921. [Google Scholar]

- Naughton F, Hopewell S, Lathia N, Schalbroeck R, Brown C, Mascolo C, McEwen A, Sutton S. A context-sensing mobile phone app (Q sense) for smoking cessation: A mixed-methods study. JMIR mHealth and uHealth. 2016;4 doi: 10.2196/mhealth.5787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naybor D, Poon JPH, Casas I. Mobility disadvantage and livelihood opportunities of marginalized widowed women in rural uganda. Annals of the American Association of Geographers. 2016;106:404–412. [Google Scholar]

- O'Cathain A, Murphy E, Nicholl J. Three techniques for integrating data in mixed methods studies. BMJ. 2010;341:c4587. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c4587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onwuegbuzie AJ, Teddlie C. A framework for analyzing data in mixed methods research. In: Tashakkori A, Teddlie RC, editors. Handbook Of Mixed Methods In Social And Behavioral Research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2003. pp. 351–383. [Google Scholar]

- Pavlovskaya M. Other transitions: Multiple economies of moscow households in the 1990s. Annals of the Association of American Geographers. 2004;94(2):329–351. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8306.2004.09402011.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pearce J, Barnett R, Moon G. Sociospatial inequalities in health-related behaviours: Pathways linking place and smoking. Progress in Human Geography. 2012;36:3–24. [Google Scholar]

- Pearson JL, Smiley SL, Rubin LF, Anesetti-Rothermel A, Elmasry H, Davis M, DeAtley T, Harvey E, Kirchner T, Abrams DB. The Moment Study: Protocol for a mixed method observational cohort study of the Alternative Nicotine Delivery Systems (ANDS) initiation process among adult cigarette smokers. BMJ open. 2016;6:e011717. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-011717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poland B, Frohlich K, Haines RJ, Mykhalovskiy E, Rock M, Sparks R. The social context of smoking: The next frontier in tobacco control? Tobacco Control. 2006;15:59–63. doi: 10.1136/tc.2004.009886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rainham D, Mc Dowell I, Krewski D, Sawada M. Conceptualizing the healthscape: Contributions of time geography, location technologies and spatial ecology to place and health research. Social Science & Medicine. 2010;70:668–676. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.10.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Remafedi G. Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youths: Who smokes, and why? Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2007;9:S65–S71. doi: 10.1080/14622200601083491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sazonov E, Lopez-Meyer P, Tiffany S. A wearable sensor system for monitoring cigarette smoking. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2013;74:956–964. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2013.74.956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwanen T. On ‘arriving on time’, but what is ‘on time’? Geoforum. 2006;37:882–894. [Google Scholar]

- Schwanen T. Struggling with time: Investigating coupling constraints. Transport Reviews. 2008;28:337–356. [Google Scholar]

- Schwanen T, De Jong T. Exploring the juggling of responsibilities with space-time accessibility analysis. Urban Geography. 2008;29:556–580. [Google Scholar]

- Shareck M, Kestens Y, Vallée J, Datta G, Frohlich KL. The added value of accounting for activity space when examining the association between tobacco retailer availability and smoking among young adults. Tobacco Control. 2015:1–7. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2014-052194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiffman S. Ecological momentary assessment (EMA) in studies of substance use. Psychological assessment. 2009;21:486. doi: 10.1037/a0017074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiffman S, Paty J. Smoking patterns and dependence: Contrasting chippers and heavy smokers. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2006;115(3):509–523. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.115.3.509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiffman S, Gwaltney C, Balabanis M, Liu K, Paty J, Kassel J. Immediate antecedents of cigarette smoking: An analysis from ecological momentary assessment. Journal of abnormal psychology. 2002;111:5310545. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.111.4.531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiffman S, Stone AA, Hufford MR. Ecological momentary assessment. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2008;4:1–32. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.3.022806.091415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiffman S, Tindle H, Li X, Scholl S, Dunbar M, Mitchell-Miland C. Characteristics and smoking patterns of intermittent smokers. Experimental And Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2012;20:264–277. doi: 10.1037/a0027546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SocioCultural Research Consultants. Dedoose v. 7.6.6 [Computer software] Los Angeles, CA: SocioCultural Research Consultants, LLC.; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- StataCorp. Stata Statistical Software: Release 14. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Stevens P, Carlson LM, Hinman JM. An analysis of tobacco industry marketing to lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (lgbt) populations: Strategies for mainstream tobacco control and prevention. Health Promotion Practice. 2004;5:129S–134S. doi: 10.1177/1524839904264617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas YF, Richardson D, Cheung I. Geography and drug addiction. New York: Springer; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson L, Pearce J, Barnett JR. Moralising geographies: Stigma, smoking islands and responsible subjects. Area. 2007;39:508–517. [Google Scholar]