ABSTRACT

CDP138 is a calcium- and lipid-binding protein that is involved in membrane trafficking. Here, we report that mice without CDP138 develop obesity under normal chow diet (NCD) or high-fat diet (HFD) conditions. CDP138−/− mice have lower energy expenditure, oxygen consumption, and body temperature than wild-type (WT) mice. CDP138 is exclusively expressed in adrenal medulla and is colocalized with tyrosine hydroxylase (TH), a marker of sympathetic nervous terminals, in the inguinal fat. Compared with WT controls, CDP138−/− mice had altered catecholamine levels in circulation, adrenal gland, and inguinal fat. Adrenergic signaling on cyclic AMP (cAMP) formation and hormone-sensitive lipase (HSL) phosphorylation induced by cold challenge but not by an exogenous β3 adrenoceptor against CL316243 were decreased in adipose tissues of CDP138−/− mice. Cold-induced beige fat browning, fatty acid oxidation, thermogenesis, and related gene expression were reduced in CDP138−/− mice. CDP138−/− mice are also prone to HFD-induced insulin resistance, as assessed by Akt phosphorylation and glucose transport in skeletal muscles. Our data indicate that CDP138 is a regulator of stress response and plays a significant role in adipose tissue browning, energy balance, and insulin sensitivity through regulating catecholamine secretion from the sympathetic nervous terminals and adrenal gland.

KEYWORDS: catecholamine release, stress response, sympathetic nerve, lipolysis, fat browning, insulin sensitivity, obesity, C2 domain protein, CDP138, insulin resistance, membrane transport

INTRODUCTION

Obesity is characterized by increased fat storage in the form of triacylglycerol (TAG) in adipose tissue and is mainly caused by a prolonged positive energy balance. Either increased energy intake or decreased energy expenditure leads to energy imbalance and obesity. Catecholamines are important hormones and neurotransmitters produced in the medulla of the adrenal glands and in some neurons of the central nervous system, and these hormones are involved in the regulation of energy expenditure. Adrenaline is the major form of catecholamine in the circulation released from the adrenal gland, while norepinephrine is the main transmitter secreted from sympathetic neuronal terminals. The major physiologic triggers of catecholamine release are acute stresses, such as physical threat (fight-or-flight response), cold exposure, or other excitement (1, 2). Catecholamines act by binding to a variety of adrenergic receptors on different tissues, and the activation of these receptors triggers a number of metabolic changes, such as lipolysis and thermogenesis, leading to an increase of energy expenditure (3–5). Catecholamine-induced lipolysis is a major pathway to reduce TAG storage in adipose tissues. Catecholamines bind to G protein-coupled beta-adrenoceptors and activate adenylate cyclase (AC), leading to an increase of cyclic AMP (cAMP). This in turn activates protein kinase A (PKA), which phosphorylates hormone-sensitive lipase (HSL). Phosphorylation of HSL triggers the translocation of HSL to the lipid droplet to participate in the process of TAG hydrolysis (6–8). In addition, PKA-dependent phosphorylation of the lipid droplet protein perilipin also interacts with HSL and facilitates HSL-mediated lipolysis (9, 10). Adipose triglyceride lipase (ATGL) is another lipase that is also involved in lipolysis (11–13). ATGL has high substrate specificity for the hydrolysis of TAG. HSL is the major lipase that mediates catecholamine-stimulated lipolysis, while ATGL is important for basal lipolysis (14). Together, ATGL and HSL are responsible for the majority of TAG hydrolase activity. Further, activation of beta-adrenoreceptor signaling also regulates thermogenesis in brown adipocytes tissue (BAT) through increased uncoupling of oxidative phosphorylation by uncoupling protein 1 (UCP1). This process catalyzes proton leakage cross the mitochondrial inner membrane and dissipates energy as heat (15–19). Expression of UCP1 and other BAT-related genes can be induced in inguinal subcutaneous white adipose tissue (iWAT) under conditions such as cold exposure or stimulation by β3-adrenergic receptor agonists (20–25). These WAT become thermogenic and are referred to as inducible BAT or beige fat (26–33).

In this study, we report that CDP138, a C2 domain-containing protein that has calcium- and lipid-binding capability, is highly expressed in the medulla of the adrenal gland and completely colocalized with TH in sympathetic nerve terminals in the inguinal fat. CDP138 may function as a novel regulatory molecule for catecholamine release. CDP138 knockout (CDP138−/−) mice are prone to developing obesity. CDP138−/− mice have decreased levels of cAMP, HSL phosphorylation, and ATGL expression, all of which are involved in the lipolysis pathway in adipose tissues. In addition, inducible beige fat browning, fatty acid oxidation, and thermogenesis in BAT in these mice are significantly diminished. We also observed that CDP138−/− mice are prone to HFD-induced insulin resistance with reduced Akt phosphorylation and glucose transport in skeletal muscles. Our data suggest for the first time that CDP138 is a new signaling molecule involved in the regulation of energy balance, fat metabolism, and insulin sensitivity by controlling catecholamine release from the adrenal gland and sympathetic neuronal terminals in fat tissues.

RESULTS

Generation of CDP138 null mice.

We previously identified CDP138 as a highly phosphorylated protein containing a calcium-binding C2 domain that is involved in insulin-regulated GLUT4 translocation and glucose transport in cultured 3T3 L1 adipocytes (34). To further illustrate its physiological function, CDP138 knockout (KO) mice were produced using an embryonic stem (ES) cell clone (IST12020E4), generated with a gene-trapping technique (Texas Institute for Genomic Medicine) with an insertion site at the first exon of the C2CD5 (5730419I09Rik) gene (Fig. 1A). The ES cell clone was microinjected into C57BL/6N host blastocysts to generate germ line chimeras. Chimeric males were bred to C57BL/6N females for germ line transmission of the mutant CDP138 allele. This was confirmed by detecting gene trap insertion into the genomic DNA and lack of CDP138 protein expression in CDP138−/− mice (Fig. 1B).

FIG 1.

CDP138 knockout mice develop obesity. (A) Gene trap strategy for generating CDP138 knockout (KO) mice. (B) PCR products (upper) and immunoblot analysis (lower) confirming the presence of the gene trap insertion and depletion of CDP138 protein in the germ line. WT and homozygous mutant mice generate 182-bp and 150-bp PCR products, respectively, from genomic DNA. (C) Representative images of 20-week-old female WT and KO mice under NCD or after feeding with an HFD (60 kcal% fat) for 8 weeks. (D) Mean body weights of WT and KO mice during NCD and 8 weeks of HFD starting at an age of 12 weeks. n = 8 in each group; P < 0.05 (*) and P < 0.01 (**) for WT versus KO mice both on NCD; #, P < 0.05 for WT versus KO mice both on HFD. (E and F) The body compositions of female mice were measured by NMR during 4 weeks of HFD feeding (n = 8 in each group; P < 0.05 [*] and P < 0.001 [**] for WT versus KO mice). (G) Deletion of CDP138 has no significant effect on mouse food intake. Female WT and KO mice (20 weeks; n = 4 in each group) were monitored in metabolic cages for 48 h under NCD or HFD feeding conditions. Food was weighed before and after the 48-h metabolic cage monitoring. (H and J) Representative images of white adipose tissue with hematoxylin and eosin staining (H) and liver tissue sections stained with Oil Red O (J). (I) Lipogenic gene expression in white adipose tissue from WT and KO mice. SubQ, subcutaneous. (K and L) Liver triglyceride contents and plasma free fatty acid levels in WT and KO mice fed a chow diet or an HFD for 8 weeks. (I) Both WT and KO mice were on a chow diet. (I, K, and L) Mice were fasted 8 h before harvesting tissues (n = 8 in each group). P < 0.05 (*) for WT versus KO mice. Scale bars, 100 μm. All data are presented as means ± SEM.

CDP138 null mice develop obesity and liver steatosis.

CDP138−/− mice are viable and fertile. In evaluation of the CDP138−/− mice physiological functions, we observed that under normal chow diet (NCD), CDP138−/− mice had higher body weight (Fig. 1C and D) than WT controls. This difference became more obvious when mice were older. When challenged with a 60% high-fat diet (HFD), CDP138−/− mice gained body weight much faster than WT controls (Fig. 1C and D). Body composition measurement with nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) revealed that the significant difference in body weight between CDP138−/− mice and WT controls was mainly due to more fat accumulation than lean body weight changes in CDP138−/− mice (Fig. 1E and F). There was no significant difference in food intake between the KO and WT mice during metabolic cage study (Fig. 1G). Adipocytes from white adipose tissue of CDP138−/− mice under both NCD and HFD conditions were bigger than those from WT mice (Fig. 1H). We also observed that white fat tissue from CDP138−/− mice had a significant increase in expression of the fatty acid synthase gene (Fasn) and the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma gene (Pparg) compared with WT mice (Fig. 1I), suggesting the lipogenesis pathway is activated in CDP138−/− mice. Oil Red O (ORO) staining revealed more lipid droplets in the liver from CDP138−/− mice than from WT mice (Fig. 1I). Consistent with this, triglyceride levels in liver samples from CDP138−/− mice fed either NCD or HFD were significantly higher than those of WT mice fed the same diet (Fig. 1K). These data suggest that CDP138−/− mice are prone to HFD-induced body weight gain, adipose hypertrophy, and lipid deposition in the liver. Surprisingly, CDP138−/− had fewer plasma free fatty acids than WT mice (Fig. 1L), although depletion of CDP138 increased lipid deposition in tissues.

CDP138 null mice have lower metabolic functions.

We further examined CDP138−/− mouse metabolic profiles monitored in metabolic cages as described previously (35–37). Both CDP138−/− and WT mice at 20 weeks of age under NCD or HFD for 8 weeks were housed in metabolic cages individually for 48 h (two cycles of dark and light). Compared to WT mice, CDP138−/− mice had significantly lower energy expenditure on NCD during both dark and light periods (0.29 ± 0.023 versus 0.35 ± 0.017 kcal/kg/min in the light and 0.35 ± 0.022 versus 0.42 ± 0.016 kcal/kg/min in the dark; P values of 0.04 and 0.02, respectively) (Fig. 2A, left). When fed an HFD, a lower energy expenditure rate was also observed during light times for CDP138−/− mice than for WT mice (Fig. 2A, right). The difference in oxygen consumption by KO and WT mice showed the exact same patterns as the energy expenditure rates. Under NCD, CDP138−/− mice had significantly lower oxygen consumption rates than WT mice (59.49 ± 4.73 versus 70.86 ± 3.36 ml/kg/min in the light and 70.65 ± 4.25 versus 83.85 ± 2.89 ml/kg/min in the dark; P values of 0.04 and 0.01, respectively) (Fig. 2B, left), while under HFD feeding the significantly lower oxygen consumption rate in CDP138−/− mice only presented during the light times compared with WT controls (Fig. 2B, right). These phenotypes indicate that CDP138−/− mice have much lower basal metabolic rates than WT mice during the light period. In terms of locomotor activity, z-axis activity (i.e., rearing) under HFD conditions in the dark was significantly lower in CDP138−/− mice than in WT mice, while other movements were similar between these two groups of mice (Fig. 2C). Overall, metabolic rates and rearing movement are significantly reduced in CDP138−/− mice.

FIG 2.

CDP138 knockout mice have lower energy expenditure and oxygen consumption and less body movement. Female WT and CDP138−/− mice or WT and KO mice (20 weeks) were monitored in metabolic cages for 48 h under NCD or HFD feeding conditions. The rates of energy expenditure (A), oxygen consumption (B), and total locomotor activity in the z axis (ZTOT) (C) were recorded and analyzed as means ± SEM during day (light) and night (dark) (n = 4 mice in each group; P < 0.05 [*] and P < 0.01 [**] for WT group versus KO group).

Lipolysis pathway in adipose tissue of CDP138 null mice is impaired.

Given the profound effect of CDP138 deletion on lipid accumulation in adipose tissue and liver but lower levels of plasma free fatty acids, we compared the lipolysis pathway in CDP138−/− mice to that in WT controls. The rate-limiting enzymes in the lipolysis pathway are ATGL and HSL. The latter is phosphorylated and activated by PKA, a downstream protein kinase activated by cAMP. We determined the levels of cAMP, HSL phosphorylation, and ATGL protein expression in adipose tissue samples from CDP138−/− and WT mice that were fed with either NCD or HFD for 10 weeks or NCD plus cold challenge at 4°C for 2 h. Deletion of CDP138 resulted in lower cAMP levels in BAT, iWAT, and skeletal muscle under all of the experimental conditions we used (Fig. 3A). Phosphorylation of HSL at Ser660, a PKA phosphorylation site (8), in BAT (Fig. 3B), and in iWAT (Fig. 3B) was significantly reduced in CDP138−/− mice compared to that in WT controls. In addition, protein levels of ATGL, the first lipase in the lipolysis pathway, in BAT and iWAT were also significantly decreased in CDP138−/− mice (Fig. 3B and C). These data indicate that the lipolysis pathway is significantly impaired in adipose tissues of CDP138−/− mice.

FIG 3.

Lipolysis pathway is impaired in CDP138 knockout mice. WT and KO female mice at 12 weeks of age were cold challenged (CC) for 2 h or fed with either NCD or an HFD for 10 weeks. Total tissue lysates from brown adipose tissue (BAT), subcutaneous inguinal white adipose tissue (iWAT), and gastrocnemius (muscle) were used for measuring cAMP levels with an ELISA kit (A) and for immunoblotting with antibodies against phospho-HSL (Ser660, a PKA phosphorylation site), HSL, ATGL, and Vps10p-tail interactor 1a (Vti1a) (B and C). Quantitative data for immunoblotting are presented as arbitrary units relative to the intensity of the band from the WT group. All data are presented as means ± SEM (n = 5 in each group; P < 0.05 [*] and P < 0.01 [**] for WT group versus KO group).

Fatty acid oxidation and thermogenesis in brown adipose tissue from CDP138 null mice are reduced.

To understand the molecular basis of reduced energy expenditure in CDP138−/− mice (Fig. 2A), we further examined the thermogenesis pathway in these mice. Both before and after cold challenge at 4°C for 2 h, CDP138−/− mice had significantly reduced core body temperatures compared to those of WT mice (Fig. 4A). BAT from CDP138−/− mice also exhibited more and larger lipid droplets, as revealed by hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining (Fig. 4B), and had less UCP1 protein expression detected with immunofluorescent staining (Fig. 4C) and quantified by immunoblotting (Fig. 4D and E). Expression of genes related to mitochondrial fatty acid oxidation, such as the PPARγ coactivator (PGC1α), cytochrome c oxidase subunit 4 (COX4), medium-chain acyl-coenzyme A dehydrogenase (Mcad), and carnitine palmitoyl transferase 1 (CPT1) genes, was significantly lower in BAT from CDP138−/− mice than in that from WT mice (Fig. 4F). We also measured the fatty acid oxidation (FAO) rate in BAT homogenates from CDP138−/− and WT mice fed with NCD. The FAO rate in BAT samples from CDP138−/− mice was significantly decreased compared to that from WT mice (Fig. 4G). Our data suggest that FAO and the thermogenesis pathway are impaired in BAT from mice lacking CDP138. In addition, the FAO rate in muscle from CDP138−/− mice was significantly decreased compared to that in muscle from WT mice (Fig. 4H).

FIG 4.

Deletion of CDP138 inhibits thermogenesis in brown adipose tissue. WT and KO male mice (10 weeks old) were challenged with cold (4°C for 2 h). (A) Mouse body temperatures were measured before and after the cold challenge with a mouse rectal thermometer. (B and C) Representative images of H&E staining (B) and immunofluorescence staining (C) of UCP-1 in BAT from WT and KO mice. Scale bars, 100 μm. (D and E) Immunoblot analysis and quantification (presented as arbitrary units) of UCP-1 protein expression in BAT from WT and KO mice. CDP138 and Vti1a were used as markers of loading control. (F) Gene expression levels of factors related to mitochondrial function. (G and H) Fatty acid oxidation (FAO) rates of BAT (G) and skeletal muscle (H) homogenates from WT and KO mice under NCD conditions were determined by measuring [1-14C]palmitate oxidation. All data are presented as means ± SEM (n = 6 in WT group and 5 in KO group; P < 0.05 [*] and P < 0.01 [**] for WT versus KO mice).

Inducible thermogenesis in beige fat of CDP138 null mice is also impaired.

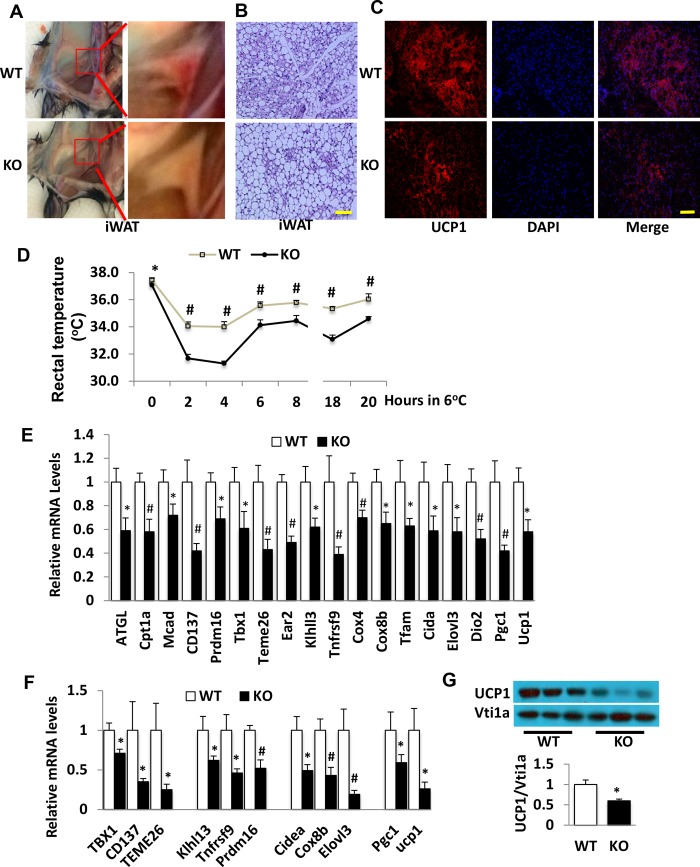

In addition to the classic thermogenesis in BAT, subcutaneous adipose tissue, particularly inguinal fat, can also undergo an inducible browning process to have thermogenesis function under certain conditions, such as cold exposure and stimulation with β3-adrenergic receptor agonists (20–27). We compared levels of inducible inguinal fat browning in CDP138−/− mice and WT controls under a cold-challenge condition. Inguinal fat from 12-week-old CDP138−/− mice exposed to cold (6°C) for 20 h displayed less browning than that from WT mice (Fig. 5A). Adipocytes from inguinal fat were also bigger, with significantly less UCP1 protein expression in CDP138−/− mice than in WT mice (Fig. 5B and C). The core body temperature of CDP138−/− mice was significantly lower than that of WT mice before cold challenge, and the difference became even bigger during the 20 h, especially the first 4 h, of cold exposure (Fig. 5D). Gene expression of markers related to beige fat, mitochondrial thermogenesis, and FAO were significantly lower in inguinal fat from CDP138−/− mice than in WT mice either after a long-term (20 h) (Fig. 5E) or a short-term (2 h) (Fig. 5F) cold challenge. UCP1 protein expression was also reduced in inguinal fat harvested from CDP138−/− mice after 20-h cold challenge (Fig. 5G). Thus, cold challenge-induced fat browning and thermogenesis are impaired in CDP138−/− mice.

FIG 5.

Deletion of CDP138 inhibits cold-induced inguinal fat browning and thermogenesis. WT and CDP138−/− male mice (12 weeks old) under NCD were exposed to cold for 20 h (long term at 6°C). (A to C) Representative images of inguinal subcutaneous white adipose tissue (iWAT) (A), H&E staining of iWAT (B), and UCP1 immunofluorescence staining of inguinal fat (C) from WT and CDP138−/− mice after 20-h cold challenge. (D) Mouse rectal temperatures were measured during the long-term cold challenge. (E and F) mRNA levels in beige fat from WT and KO mice after 20 h (E) or 2 h (F) of cold exposure. (G) UCP-1 protein levels in beige fat from WT and KO mice exposed to cold for 20 h. The data are presented as means ± SEM (n = 6 in WT group and 8 in KO group; P < 0.05 [*] and P < 0.01 [#] for WT mice versus KO mice). Scale bars, 100 μm.

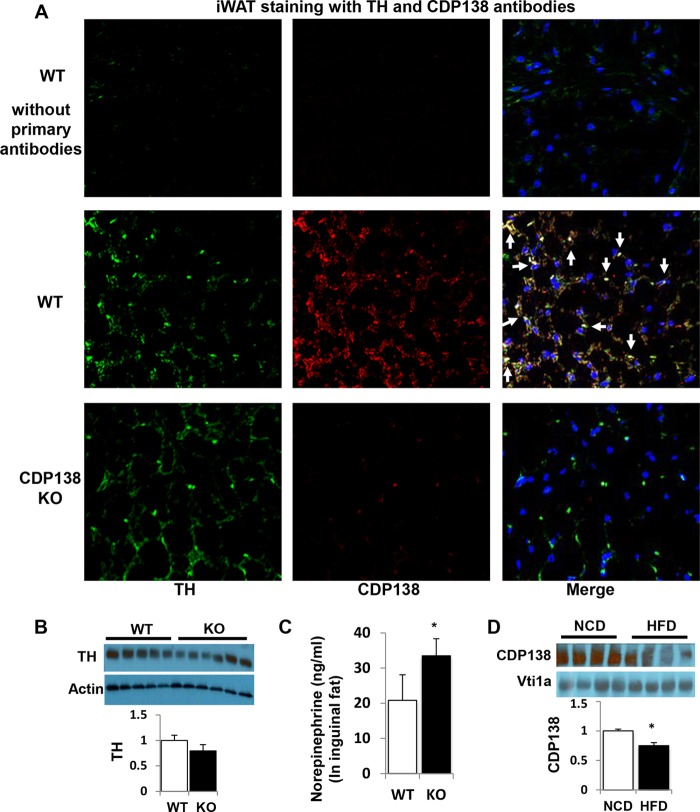

CDP138 is highly expressed in TH-positive sympathetic nervous terminals in inguinal fat.

We next explored the molecular mechanisms underlying impairment of lipolysis, thermogenesis, and beige fat browning in CDP138−/− mice. Since subcutaneous fat browning is known to be regulated by the sympathetic nervous system, we also compared sympathetic neuronal terminal distribution in the inguinal fat from CDP138−/− mice and WT controls after cold challenge for 20 h. Specific antibody against tyrosine hydroxylase (TH), a marker for sympathetic nervous terminals, was used for immunofluorescence staining. Our data revealed that TH signal completely overlaps CDP138 signal in the area around adipocytes in the inguinal fat (Fig. 6A), suggesting that CDP138 is involved in sympathetic nerve function. However, deletion of CDP138 did not alter the distribution of TH-positive cells. Considering cAMP levels in iWAT samples from CDP138−/− mice were significantly reduced, we also determined TH protein and norepinephrine levels in the inguinal fat after cold challenge. There was no significant different in TH protein expression in inguinal fat from CDP138−/− mice and WT controls both fed a normal chow diet (Fig. 6B). Surprisingly, CDP138−/− mice had significantly higher levels of norepinephrine than WT controls (Fig. 6C), although CDP138−/− mice had lower levels of cAMP in the inguinal fat (Fig. 3A). Our data are consistent with the finding that norepinephrine released from the nervous terminals is prone to degradation. Hence, it is possible that CDP138 is required for cold-stimulated activation of sympathetic signaling in the adipose tissue. We also assessed if HFD feeding affects CDP138 expression in inguinal fat. Figure 6D shows that HFD feeding for 16 weeks significantly reduced CDP138 protein levels in the total lysate from the fat tissue, suggesting CDP138 has a role in obesity-related functional changes.

FIG 6.

CDP138 is colocalized with sympathetic marker tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) in inguinal fat and is involved in the regulation of norepinephrine levels in fat tissue. (A) Formaldehyde-fixed inguinal fat sections from 20-h cold-challenged mice were used for immunofluorescence staining with antibodies against TH and CDP138 as described in Materials and Methods. Arrows indicate colocalization of CDP138 and TH in iWAT. (B) TH expression in iWAT from WT and CDP138 KO mice fed a chow diet. (C) Norepinephrine levels in iWAT after cold challenge for 20 h. n = 8 for each group. *, P < 0.05 for WT versus KO mice. (D) CDP138 expression in iWAT from C57BL/6 mice fed a chow diet (NCD) or an HFD (60 kcal% fat) for 16 weeks. *, P < 0.05 for NCD versus HFD; n = 6 for each group.

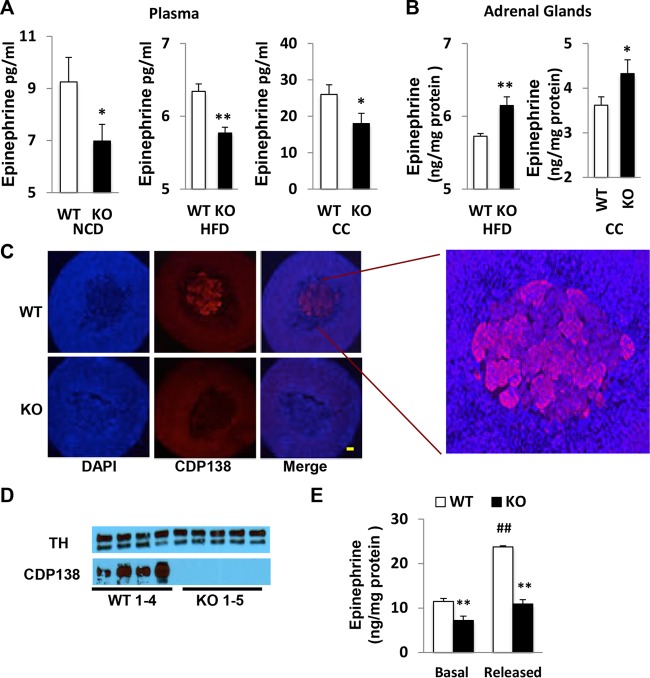

CDP138 deletion inhibits adrenaline release from adrenal gland.

We further evaluated circulating factors that might activate the cAMP pathway. There was no difference in plasma levels of glucagon between CDP138−/− mice and WT controls (data not shown). However, plasma adrenaline levels were significantly lower in CDP138−/− mice than in WT mice under NCD, HFD, or cold challenge conditions (Fig. 7A), while adrenaline levels in the total lysates from adrenal glands were significantly higher in CDP138−/− mice than WT mice (Fig. 7B). This is likely due to reduced adrenaline release from the medulla of the adrenal gland of CDP138−/− mice. Interestingly, immunofluorescence staining with anti-CDP138 antibody revealed that CDP138 is exclusively expressed and localized in the medulla, but not cortex, of the adrenal gland (Fig. 7C). In addition, there was no difference in protein expression of TH, an enzyme critical for the adrenaline synthesis pathway, in adrenal glands from CDP138−/− and WT mice (Fig. 7D), suggesting that the adrenaline synthesis pathway is not altered in CDP138−/− mice. We also assessed adrenaline release from isolated adrenal glands. Compared with those of WT mice, adrenal glands from CDP138−/− mice released much less adrenaline in response to treatment with nicotine (Fig. 7E), an activator of acetylcholine receptors in adrenal glands. Our data suggest CDP138 is required for nicotine-stimulated adrenaline release from adrenal glands directly.

FIG 7.

CDP138 is predominantly expressed in adrenal medulla and required for both basal and stressed-induced adrenaline release from adrenal glands. (A) Plasma adrenaline levels were measured by ELISA from 20-week-old mice fed with NCD (n = 4 in WT group and n = 6 in KO group) (left), 20-week-old mice fed with an HFD for 8 weeks (n = 8 in WT group and n = 7 in KO group) (middle), and 12-week-old mice fed with NCD plus cold challenge (CC) for 2 h (n = 6 in WT group and n = 7 in KO group) (right). (B) Adrenaline levels in total lysates of adrenal glands were measured by ELISA from 20-week-old mice fed with HFD for 8 weeks and 12-week-old female mice fed with NCD plus cold challenge for 2 h. (C) Immunofluorescence of CDP138 with adrenal gland tissue sections from 20-week-old WT and KO mice. Scale bars, 100 μm. (D) Adrenal gland tissue lysates from 20-week-old female WT and KO mice were immunoblotted with anti-tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) and anti-CDP138 antibodies. (E) Isolated adrenal gland of 12-week-old female WT and KO mice were minced and washed three times before incubation in 1 ml of enriched Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium for 30 min at 37°C. Conditional medium (200 μl) was taken for the basal adrenaline release measurement, and then the minced tissues were treated with 100 μM nicotine for 5 min to stimulate adrenaline release (n = 9 in each group). All data are presented as means ± SEM. P < 0.05 (*) and P < 0.01 (**) for WT versus KO mice; #, P < 0.01 for basal versus nicotine-stimulated adrenal medulla cells.

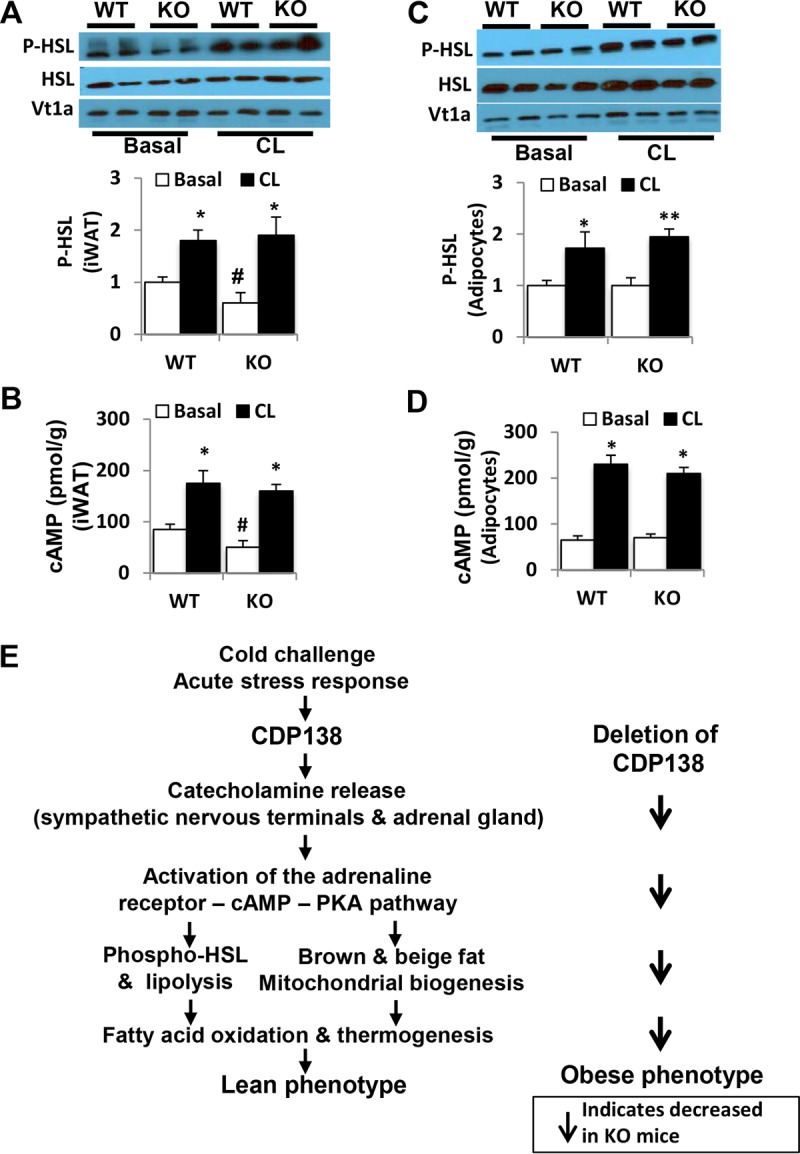

Deletion of CDP138 does not affect adrenoceptor signaling in adipose tissue induced by β3-adrenoceptor agonist CL316243.

We further evaluated if deletion of CDP138 affects adrenoceptor signaling in adipose tissue induced by the exogenous β3-adrenergic agonist CL316243. In this study, CL316243 was administered to both CDP138−/− mice and WT controls via intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection. As shown in Fig. 8A and B, CDP138−/− mice and WT controls had similar responses to CL316243-induced phosphorylation of HSL at PKA site Ser660 and cAMP production in subcutaneous adipose tissue. In addition, isolated adipocytes from CDP138−/− mice and WT controls were treated with CL316243 in an in vitro study. Again, adipocytes lacking CDP138 responded as effectively as the WT cells to CL316243-induced activation of the cAMP-HSL pathway (Fig. 8C and D). Together, our data suggest that CDP138 does not affect autonomous adrenoceptor signaling in adipose tissue.

FIG 8.

Deletion of CDP138 does not affect adrenoceptor signaling in inguinal adipose tissue induced by β3-adrenoceptor agonist CL316243. (A and B) WT and CDP138 KO mice (female, 10 weeks old) were administered CL316243 (1 mg/kg; Tocris Bioscience) or vehicle via i.p. injection. Subcutaneous iWAT were harvested 6 h after injection. (C and D) Primary adipocytes isolated from WT or CDP138 KO mouse inguinal fat were incubated with or without CL316243 (1 μM) for 30 min at 37°C. Total protein samples were used for quantification of HSL and phospho-HSL by immunoblot analysis (A and C) and measurement of cAMP (B and D). All data are presented as means ± SEM (n = 6 each group). *, P < 0.05 for basal versus CL-stimulated mice (A and B) or adipocytes (C and D); #, P < 0.05 for WT versus KO mice, both without CL treatment (A and B). (E) Schematic illustration of the molecular mechanism underlying the role of CDP138 in lipid metabolism, thermogenesis, and energy balance. Arrows indicate changes observed in CDP138 KO mice.

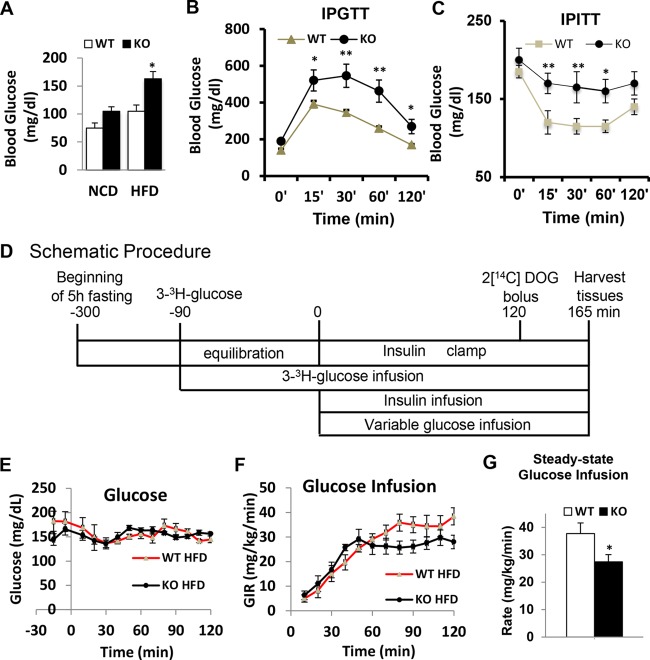

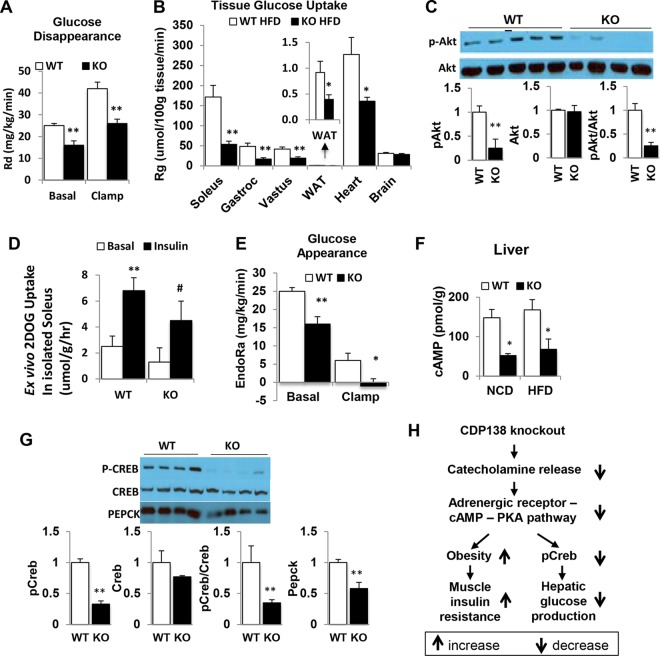

CDP138 null mice are prone to exacerbated HFD-induced insulin resistance.

To evaluate if deletion of CDP138 affects glucose metabolism, we performed glucose and insulin tolerance tests (GTT and ITT, respectively) with CDP138−/− and WT mice after feeding with 60% HFD for only 5 to 6 weeks. Compared with WT controls, CDP138−/− mice had higher fasting blood glucose levels and reduced glucose tolerance and insulin sensitivity (Fig. 9A to C). After being fed an HFD for 6 weeks, WT and CDP138−/− mice were also used for hyperinsulinemic-euglycemic clamp studies (Fig. 9D) (38, 39). CDP138−/− mice required less glucose infusion to maintain euglycemia (∼150 mg · dl−1) than WT mice (Fig. 9E to G). The rate of glucose disappearance was also significantly lower in CDP138−/− mice under both basal and clamp conditions (Fig. 10A). We also measured tissue [2-14C]deoxyglucose uptake (i.e., glucose metabolic rate [Rg]) during the euglycemic clamp. Figure 10B shows that CDP138−/− mice exhibit decreased insulin-stimulated glucose uptake into different skeletal muscles, heart, and WAT but not brain. Furthermore, Akt phosphorylation at Ser473 was significantly reduced in gastrocnemius muscle from CDP138−/− mice (Fig. 10C), suggesting impaired insulin signaling in the muscle. To evaluate if deletion of CDP138 has a direct effect on glucose transport, we also performed an ex vivo glucose transport assay with isolated soleus muscle from WT and CDP138−/− mice. Our data did not show significant differences in insulin-stimulated 2-deoxyglucose uptake, although there is a tendency toward lower glucose transport activity in isolated soleus from CDP138−/− mice (Fig. 10D).

FIG 9.

CDP138 null mice are prone to diet-induced insulin resistance. (A) Female, 20-week-old WT or KO mice were fed with NCD or HFD for 6 weeks and fasted overnight before glucose levels were measured in the morning. (B and C) For the glucose tolerance test (B) and insulin tolerance test (C), WT and CDP138 KO mice were fed an HFD for 6 weeks. Mice then were fasted for 6 h, followed by intraperitoneal injection of either glucose (0.9 g/kg) or insulin (0.75 U/kg). Blood glucose levels were measured before and at 15, 30, 60, and 120 min after injection. Basal glucose levels were measured before the injection. Data are presented as means ± SEM (n = 9 in each group). P < 0.05 (*) for comparisons of WT and KO mice. For hyperinsulinemic-euglycemic clamps (D to G), female WT and KO mice (10 weeks old) were fed an HFD for 6 weeks before the surgery, and then experiments were performed 1 week after the surgery as described in Materials and Methods. (D) A timeline of procedures for setting up and performing an insulin clamp experiment. During the clamp, blood samples are taken every 10 min to measure blood glucose. The glucose infusion rate (GIR) is adjusted accordingly to maintain euglycemia. Samples for baseline blood glucose, plasma insulin, and plasma [3-3H]glucose are taken at −15 and −5 min. Samples for clamp plasma [3-3H]glucose are taken at 80, 90, 100, 110, and 120 min and for clamp insulin at 100 and 120 min. [2-14C]deoxyglucose (2DOG) is administered after the sample at 120 min, and blood is collected at 2, 15, 25, and 35 min after. Tissues are taken after 35 min. (E and F) Time course of blood glucose (E) and GIR (F). (G) Average glucose infusion rate during the euglycemic clamps. Data are presented as means ± SEM (n = 7 in each group). P < 0.05 (*) for comparisons of WT and KO mice.

FIG 10.

CDP138 null mice have decreased glucose production in the liver and reduced glucose uptake in muscles and fat. WT and CDP138 KO mice were fed and subjected to euglycemic clamping as described in the legend to Fig. 9. (A and E) Glucose disappearance (A) and glucose appearance (E). (B) [2-14C]deoxyglucose (2DOG) uptake by different periphery tissues. (Inset) WAT. Data are presented as means ± SEM (n = 7 in each group). P < 0.01 (**) and P < 0.05 (*) for comparisons of WT and KO mice. Gastroc, gastrocnemius muscle. (D) Soleus muscles were isolated from WT and CDP138 KO mice and used for [2-14C]deoxyglucose transport assay ex vivo as described in Materials and Methods. n = 6 for each group. **, P < 0.01 for basal versus insulin for WT groups; #, P < 0.05 for basal versus insulin for KO groups. (C and G) For Western blot analysis, cell lysate protein samples were prepared from muscle (for pSer473-Akt) (C) and liver (for pSer133-CREB, CREB, and PEPCK) (G) from 20-week-old female mice fed with HFD for 8 weeks. Data are presented as means ± SEM (n = 8 in each group). **, P < 0.01 for comparisons of WT and KO mice. (F) For measuring cAMP levels, total liver tissue lysates from 16-week-old female mice fed with either HFD or NCD for 8 weeks were used for measuring cAMP levels with an ELISA kit. Data are presented as means ± SEM (n = 8 in each group). *, P < 0.05 for comparisons of WT and KO mice. (H) Schematic illustration of the mechanism by which deletion of CDP138 affects glucose metabolism in the skeletal muscle and liver. Thick arrows indicate changes observed in CDP138 KO mice.

Deletion of CDP138 suppresses hepatic glucose production.

As described previously (38, 39), [3-3H]glucose was used to estimate the rate of endogenous glucose appearance (EndoRa), which is an index of hepatic glucose production (HGP). Figure 9D shows that basal HGP is significantly lower in CDP138−/− mice than in the WT controls. Surprisingly, insulin-induced suppression of HGP is greater in CDP138−/− mice than in WT mice. Considering catecholamine is an activator of HGP through stimulating gluconeogenesis, we further compared the cAMP signaling pathway in the liver of WT and CDP138−/− mice. cAMP levels were much lower in total liver lysate from CDP138−/− mice than WT mice (Fig. 10E). Phosphorylation of cAMP response element-binding protein (CREB) at Ser133, a PKA phosphorylation site, in the liver was significantly reduced in CDP138−/− mice (Fig. 9F). We also observed that the expression of phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase (PEPCK), a key enzyme controlling gluconeogenesis, was significantly reduced in the liver from CDP138−/− mice (Fig. 10F). These data are consistent with reduced CREB phosphorylation, since phosphorylated CREB is known to be an important positive regulator of PEPCK gene expression (40, 41). Therefore, deletion of CDP138 affects HGP due to suppression of catecholamine secretion from the adrenal gland and its action in the liver (Fig. 10G).

DISCUSSION

In this study, for the first time, we applied a whole-body knockout mouse model to explore physiological functions of CDP138, a recently identified protein known to be involved in intracellular vesicle trafficking (34). CDP138−/− mice have increased body weight, adipose hypertrophy, and fatty liver content compared to those of WT controls. After challenge with an HFD, CDP138−/− mice accumulate significantly more body fat than WT controls. Metabolic analyses revealed that CDP138−/− mice have lower rates of energy expenditure and oxygen consumption under both NCD and HFD feeding conditions. Interestingly, the lipolysis pathway is compromised in CDP138−/− mice. Both cAMP levels and cAMP-dependent phosphorylation of HSL are significantly reduced in BAT and iWAT in CDP138−/− mice. Furthermore, we found that core body temperature and expression of factors related to BAT mitochondrial function and inguinal fat browning are decreased in CDP138−/− mice, suggesting that both classical and inducible thermogenesis are impaired in this loss-of-function mouse model.

Based on available information, CDP138 is the first C2 domain protein reported to be involved in the regulation of energy balance and thermogenesis. The C2 domain from CDP138 is similar to that in synaptotagmin-1, a protein involved in synaptic vesicle fusion (42), and is capable of binding calcium ions and membrane lipids. This biochemical property of CDP138 is important for its role in intracellular vesicle fusion with the plasma membrane in cultured cells (34). In this study, we also explored the potential molecular mechanism by which CDP138 regulates energy balance. First, we observed that CDP138−/− mice have lower plasma adrenaline levels while retaining higher levels of intracellular adrenaline in adrenal glands compared to WT mice under either the basal or cold-stressed state. Second, isolated adrenal glands from CDP138−/− mice also released less adrenaline in response to nicotine stimulation. Third, CDP138 is exclusively expressed in the medulla of the adrenal gland, where adrenaline is produced and stored in the dense core vesicles before being released. Furthermore, CDP138 completely colocalized with TH, a marker for sympathetic nervous terminals in inguinal fat. As mentioned above, CDP138−/− mice may stabilize norepinephrine levels in inguinal fat by preventing the transmitter release from the nervous terminals where the transmitter is protected from degradation. Provided the CDP138 protein level is also reduced in adipose tissue from HFD-fed obese mice, it is likely that CDP138 is involved in sympathetic function, at least in fat tissues, both under physiological and pathological states.

Catecholamine activates its G protein-coupled receptor, which triggers adenylate cyclase activity, resulting in the accumulation of cAMP and activation of PKA. The latter in turn phosphorylates and activates HSL, a rate-limiting enzyme of lipolysis, in the target tissues. Consistent with less catecholamine secretion from either adrenal gland or sympathetic nervous terminals, CDP138−/− mice have lower cAMP levels, less phosphorylation of HSL, and decreased expression of ATGL in several metabolic tissues, including BAT, iWAT, liver, and skeletal muscles, than WT controls. Therefore, CDP138 affects not only catecholamine release but also activation of the cAMP-PKA-lipolysis pathway. Depletion of CDP138 also leads to the impairment of both classical and inducible thermogenesis. Those changes include less fat browning, lower body temperature, and decreased gene expression of factors involved in mitochondrial function, uncoupling processes, fat browning, and differentiation in BAT and iWAT of CDP138−/− mice. Our data provide the first evidence that CDP138 functions as a mediator of basal and stress-induced catecholamine secretion. Hence, CDP138 is an important factor affecting metabolic rate and energy balance through regulating fat browning, lipolysis, FAO, and thermogenesis (Fig. 8E). It is possible that calcium-sensitive CDP138 is involved in trafficking processes of the catecholamine-containing dense core vesicles. However, further studies are needed to understand how CDP138 is activated under stress and how CDP138 regulates catecholamine secretion from the sympathetic nervous terminals and adrenal gland.

With regard to glucose metabolism, our data clearly demonstrated that CDP138−/− mice are susceptible to developing insulin resistance, marked by reduced Akt phosphorylation in skeletal muscles and impaired glucose uptake by periphery tissues, such as skeletal muscles, heart, and fat. Considering that CDP138 knockdown in cultured cells does not affect insulin-stimulated Akt phosphorylation (34), impaired insulin signaling and action in the muscles or fat observed in CDP138−/− mice are most likely the consequence of obese phenotype due to lack of catecholamine action. This rationale is further augmented by lack of an insulin resistance phenotype, evaluated by intraperitoneal glucose tolerance test (IPGTT) and intraperitoneal insulin tolerance test (IPITT), in 10-week-old CDP138−/− mice and WT controls fed a normal chow diet (data not shown). Intriguingly, unlike most insulin-resistant mouse models, CDP138−/− mice have reduced basal and insulin-suppressed HGP (Fig. 10E). This is consistent with the notion that catecholamine has insulin-antagonistic effects on HGP, since declining adrenaline or norepinephrine action leads to weakening the cAMP-CREB-gluconeogenesis pathway in the liver of CDP138−/− mice (Fig. 10G and H). Hence, deletion of CDP138 has two different effects on glucose metabolism: suppression of glucose output from the liver and reduction of glucose transport and utilization in muscle, heart, and fat tissues. It is worth noting that the overall effect of deletion of CDP138 on glucose metabolism is decreased glucose clearance due to development of obesity and muscle insulin resistance resulting from lack of sufficient catecholamine action, particularly when mice are challenged with an HFD. Thus, deletion of CDP138 provides a valuable mouse model for studying the roles of regulated secretion of the stress factor catecholamine on metabolic functions under both physiological and overnutrition states.

In summary, we discovered that C2 domain-containing CDP138, an intracellular trafficking protein, is a regulator for catecholamine secretion from adrenal gland and sympathetic nervous terminals. This function is important for maintaining basal and fight-or-flight acute stress responses to produce energy and heat. Depletion of CDP138 leads to the development of energy imbalance and obesity due to the impairment of fat browning, lipolysis, FAO, and thermogenesis. In addition, deletion of CDP138 also leads to insulin resistance and impaired glucose metabolism in HFD-challenged mice due to lack of catecholamine actions. This study provides the new insight that modulating the expression and activity of CDP138 is a potential strategy for controlling body fat metabolism and maintaining energy balance and glucose homeostasis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals.

CDP138 null mice (KO) with a C57BL/6N background were initially generated as described in Results at the Texas Institute for Genomic Medicine (College Station, TX). All mouse work was performed according to Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee guidelines. Mice were housed in certified facilities at Boston University School of Medicine (Boston, MA) and Sanford Burnham Prebys Medical Discovery Institute (Orlando, FL). The mice were maintained on NCD (Harlan Teklad 2018; Harlan, Madison, WI) or on HFD (D12492 rodent diet, 60 kcal% fat; Research Diet, New Brunswick, NJ). The genotyping for KO mice was conducted using PCR and the following primers: forward primer TGTTACAGGAGTGTAGGAGCATGC, reverse primer CTCAGAACTACACAACTGTCTTCC, and mutant reverser primer CCAATAAACCCTCTTGCAGTTGC.

Isolation of primary adipocytes.

Mouse inguinal white adipose tissues were used for isolation of primary adipocytes. Briefly, inguinal adipose tissues from WT and CDP138 KO mice were minced and digested in Hanks' balanced salt solution containing 2% bovine serum albumin (BSA) and collagenase (1 mg/ml) for 60 min at 37°C before being passed through a 100-μm nylon strainer. Isolated adipocytes were washed with Krebs-Ringer glucose buffer (2% BSA) and used for the designed experiments.

Body composition analysis.

Body composition of live conscious mice was measured after fasting for 5 h using a Minispec LF90II time domain NMR analyzer (Bruker Optics, Inc., Billerica, MA).

Metabolic cage study.

Metabolic measurements were performed using the Comprehensive Lab Animal Monitoring System (Columbus Instruments, Columbus, OH). Animals were individually housed in metabolic chambers maintained at 22 to 23°C on a 12-h light-dark cycle. Food (NCD or HFD) and water were available ad libitum. Mice were adapted to the cages for 12 to 18 h. Oxygen consumption (VO2) and carbon dioxide production (VCO2) by individual mice were measured for 1-min periods at intervals of 15 min over a total of 48 h. Airflow was set at 0.6 liter/min. Energy expenditure was calculated as (3.815 + [1.232 × RER]) × VO2, where RER is the respiratory exchange ratio (VCO2/VO2). Food intake (total and accumulated) was determined using a precision scale. Water intake (total and accumulated) was determined using a volumetric drinking monitor. Ambulatory activity was estimated by the number of infrared beam breaks along the x axis, and rearing activity was estimated by the number of infrared beam breaks along the z axis.

Insulin and glucose tolerance tests.

Glucose and insulin tolerance testing were performed as previously described (37). For glucose tolerance, animals were fasted overnight and then injected intraperitoneally with glucose (0.9 g/kg of body weight). Mice were bled from the tail vein, and glucose concentrations were determined using a blood glucometer (Bayer). Measurements were taken at baseline (prior to injection) and at 15, 30, 60, 90, and 120 min postinjection. For insulin tolerance, mice were fasted for 6 h the morning of the test and then injected intraperitoneally with insulin (0.75 U/kg). Blood samples were collected and glucose levels measured as described for the glucose tolerance test.

Hyperinsulinemic-euglycemic clamps.

Catheters were surgically implanted in the right jugular vein for infusions as described previously (38, 39). Mice were allowed to recover for a week before insulin clamps were applied. Briefly, mice were fasted 90 min before continuous infusion of [3-3H]glucose (2.5 mCi prime followed by 0.05 mCi · min−1 for the measurement of glucose turnover). A continuous infusion of insulin (2.5 mU · kg−1 · min−1; Humulin; Eli Lilly) and a variable infusion of glucose was adjusted according to blood glucose levels measured every 10 min to maintain euglycemia (∼150 mg · dl−1). At the end of the insulin clamp procedure, a 12-mCi bolus of [2-14C]deoxyglucose ([2-14C]DG; PerkinElmer) then was administered via the jugular vein catheter to assess rates of glucose uptake in tissues excised from anesthetized animals at the end of the clamp study. Plasma [3-3H]glucose and [2-14C]DG levels were determined from deproteinized samples by the method of Somogyi as previously described (49). Rates of glucose appearance (Ra) and disappearance (Rd) were calculated using Steele's non-steady-state equations (43, 44). The rate of endogenous glucose appearance (EndoRa) was determined by subtracting the glucose infusion rate (GIR) from the Ra. The glucose metabolic rate (Rg), an index of glucose uptake, was calculated as previously described (45, 46). Rg was normalized to tissue weight.

Ex vivo glucose transport assay.

Soleus muscles were isolated from mice fasted overnight, and glucose uptake assay was performed as described previously (47). Briefly, muscles were preincubated for 30 min at 37°C in Krebs-Ringer-bicarbonate (KRB) buffer containing 8 mM d-glucose before being treated with insulin (10 nM) for 20 min or being left untreated. The muscles were rinsed with KRB buffer containing 8 mM d-mannitol for 10 min before incubation in KRB buffer containing 1 mM 2-deoxy-d-[1,2-3H]glucose (1.5 mCi/ml) and 7 mM d-[14C]mannitol (0.3 mCi/ml) at 30°C for 10 min. To terminate the transport, muscles were dipped in KRB buffer containing 80 mM cytochalasin B at 4°C. Muscles were digested by incubation in 300 ml 1N NaOH at 80°C for 10 min and neutralized with 300 ml 1 N HCl. Radioactivity in extracted aliquots was determined with scintillation counting for dual labels, and the extracellular and intracellular spaces were calculated.

ELISA and other kits.

Plasma or tissue levels of adrenaline, norepinephrine, and cAMP were determined with enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits (adrenaline ELISA kit [Labor Diagnostika Nord GmbH & Co. KG], cAMP ELISA kit [Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA], and norepinephrine ELISA [Rocky Mountain Diagnostics, Inc., Spring, CO]) and mouse insulin ELISA kits, purchased from Millipore (Danvers, MA), by following the manufacturer's instructions. Plasma free fatty acids were measured with a fluorometric assay kit provided by Cayman Chemical (number 700310).

Cold exposure.

Experimental animals were caged individually in cold rooms at 4°C for 2 h (short term) or 6°C for 20 h (long term), and body temperatures were measured every 2 h during cold exposure with a rectal probe (Braintree Scientific, Braintree, MA).

Gene expression.

Total RNAs were extracted from tissues using TRIzol reagent (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA), and cDNAs were generated with the ProtoScript first-strand cDNA synthesis kit (New England BioLabs, Ipswich, MA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Real-time PCRs were performed using the ViiA TM7 real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) with SYBR green JumpStart Taq ready mix (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) according to the manufacturer's instructions. 36B4 was used as an internal control. All samples were run in triplicate. The results are expressed as fold change in mRNA levels relative to the expression of 36b4 in the same samples and were calculated with the following formula based on two replications in each cycle: fold change = [efficiency(c − t) of target gene/efficiency(c − t) of 36b4 mRNA], where c represents the cycle threshold (CT) for the target gene or 36b4 in the experimental control samples and t represents the CT for the target gene or 36b4 in test samples. Gene-specific PCR primers include the following: CDP138 (C2cd5) forward, 5′-GCGGAGAAATCAATGTTGTGGT-3′, and reverse, 5′-ATCAATCCACTGATACTCGGGA-3′; Atgl forward, 5′-ACCACC CTTTCCAACATGCTA-3′, and reverse, 5′-GGCAGAGTATAGGGCACCA-3′; Cidea forward, 5′-TGCTCTTCTGTATCGCCCAGT-3′, and reverse, 5′-GCCGTGTTAAGGAATCTGCTG-3′; Cox4i1 forward, 5′-TGAATGGAAGACAGTTGTGGG-3′, and reverse, 5′-GATCGAAAGTATGAGGGATGGG-3′; Cox8b forward, 5′-TGTGGGGATCTCAGCCATAGT-3′, and reverse, 5′-AGTGGGCTAAGACCCATCCTG-3′; Cpt1a forward, 5′-GGAGAGAATTTCATCCACTTCCA-3′, and reverse, 5′-CTTCCCAAAGCGGTGTGAGT-3′; Dio2 forward, 5′-CAGTGTGGTGCACGTCTCCAATC-3′, and reverse, 5′-TGAACCAAAGTTGACCACCAG-3′; Ear2 forward, 5′-CCTGTAACCCCAGAACTCCA-3′, and reverse, 5′-CAGATGAGCAAAGGTGCAAA-3′; Elovl3 forward, 5′-TTCTCACGCGGGTTAAAAATGG-3′, and reverse, 5′-GAGCAACAGATAGACGACCAC-3′; Il4ra forward, 5′-GTCACAGAGCAGCCTTCACA-3′, and reverse, 5′-AAAACTCCGGTAGGCAGGAT-3′; Klhl13 forward, 5′-AGAATTGGTTGCTGCAATACTCC-3′, and reverse, 5′-AAGGCACAGTTTCAAGTGCTG-3′; Mcad forward, 5′-TTTCGAAGACGTCAGAGTGC-3′, and reverse, 5′-TGCGACTGTAGGTCTGGTTC-3′; Pgc1a forward, 5′-AGCCGTGACCACTGACAACGAG-3′, and reverse, 5′-GCTGCATGGTTCTGAGTGCTAAG-3′; Ppara forward, 5′-TGTTTGTGGCTGCTATAATTTGC-3′, and reverse, 5′-GCAACTTCTCAATGTAGCCTATGTTT-3′; Prdm16 forward, 5′-CAGCACGGTGAAGCCATTC-3′, and reverse, 5′-GCGTGCATCCGCTTGTG-3′; Scd1 forward, 5′-CCTTCCCCTTCGACTACTCTG-3′, and reverse, 5′-GCCATGCAGTCGATGAAGAA-3′; Tfam forward, 5′-CACCCAGATGCAAAACTTTCAG-3′, and reverse, 5′-CTGCTCTTTATACTTGCTCACAG-3′; Tmem26 forward, 5′-ACCCTGTCATCCCACAGAG-3′, and reverse, 5′-TGTTTGGTGGAGTCCTAAGGTC-3′; Tnfrsf9 forward, 5′-CGTGCAGAACTCCTGTGATAAC-3′, and reverse, 5′-GTCCACCTATGCTGGAGAAGG-3′; Ucp1 forward, 5′-AGGCTTCCAGTACCATTAGGT-3′, and reverse, 5′-CTGAGTGAGGCAAAGCTGATTT-3′; Fasn forward, 5′-GCT GCG GAA ACT CAG GAA AT-3′, and reverse, 5′-AGA GAC GTG TCA CTC CTG GAC TT-3′; SCD1 forward, 5′-CCT TCC CCT TCG ACT ACT CTG-3′, and reverse, 5′-GCC ATG CAG TCG ATG AAG AA-3′; Srebp1c forward, 5′-GGA GCC ATG GAT TGC ACA TT-3′, and reverse, 5′-GGC CCG GGA AGT CAC TGT-3′; and Pparg forward, 5′-TGC ACT GCC TAT GAG CAC TT-3′, and reverse, 5′-ATC ACG GAG AGGTCC CAC AGA-3′.

Fatty acid oxidation rate.

Freshly collected brown fat tissues or gastrocnemius muscles (100 mg protein) were used for measuring fatty acid oxidation as previously described (37). Briefly, samples were homogenized with a motor-driven Teflon pestle in ice-cold buffer (250 mM sucrose, 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 2 mM ATP, and 1 mM EDTA). The homogenates were centrifuged at 500 × g for 5 min. The crude homogenates from the liver (500 μg protein) and from brown fat (100 μg protein) were used for fatty acid oxidation. Oxidation was measured in a 350-μl reaction buffer containing 125 mM sucrose, 25 mM KH2PO4, 200 mM KCl, 2.5 mM MgCl2 6H2O, 2.5 mM l-carnitine, 0.25 mM malic acid, 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 2.5 mM dithiothreitol, 0.25 mM NAD+, 4 mM ATP, and 0.125 mM coenzyme A with 14.5 μM [1-14C]palmitate (0.31 μCi/reaction mix) complexed to fatty acid-free BSA. Fatty acid oxidation studies measured the production of 14C-labeled carbon dioxide for 30 min at 37°C. The reaction was stopped by adding 60% perchloric acid to the reaction mixture and then incubated for 1 h to trap the CO2 into 1N NaOH. Radioactivity of captured CO2 in NaOH solution was determined by liquid scintillation. The fatty acid oxidation rate was quantified using the following formula: [(dpm blank)4.5 × 10−10/SA]/[micrograms of protein of tissue × hours of reaction incubation], where dpm is the number of disintegrations per minute and SA is the palmitic acid specific radioactivity (60 mCi/mmol).

Western blot analysis.

As described previously (48), after experimental treatments, the cells or mouse tissues were homogenized in ice-cold lysis buffer containing 50 mM HEPES (pH 7.4), 137 mM NaCl, 5 mM sodium pyrophosphate, 5 mM β-glycerophosphate, 10 mM sodium fluoride, 2 mM EDTA, 2 mM Na3VO4, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 10 μg/ml aprotinin, 10 μg/ml leupeptin, and 1% Triton X-100. Total cell lysates (30 to 50 μg of protein) were resolved with SDS-PAGE and electrotransferred to nitrocellulose membranes (Thermo Scientific), which were then incubated with specific primary antibodies followed by second antibodies conjugated with horseradish peroxidase (HRP). Specific protein bands were detected by SuperSignal West Pico luminol/enhancer solution (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL).

Antibodies.

Rabbit polyclonal antibodies against phospho-Ser133-CREB (9196), CREB (9193), phospho-Ser660-HSL (4126), HSL (4107), phospho-Ser473-Akt (4060), Akt (9272), and ATGL (2138), as well as HRP-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibody (7074; dilution, 1:10,000), were from Cell Signaling Technology. Antibody against tyrosine hydroxylase (Ab9983) was from EMD Millipore; rabbit CDP138 (kiaa0528) antibody was from Bethyl Laboratories, Inc. (Montgomery, TX), rabbit PEPCK antibody (sc-32879; 1:500 dilution) was from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., rabbit UCP1 antibody (PA1-24894; dilution, 1:2,000) was from Thermo Scientific, and mouse monoclonal antibody against Vit1a (611220) was from BD Biosciences. All primary antibodies, except for those mentioned specifically, were diluted 1,000-fold for immunoblotting.

Histological analysis.

The liver and adipose tissues were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde before H&E staining using a standard protocol (Sigma). Frozen liver tissues were used for Oil Red O staining with the ORO kit as described by the manufacturer (Poly Scientific R&D Corp). To detect UCP-1 expression in inguinal fat and CDP138 distribution in adrenal gland, rabbit polyclonal antibodies against UCP-1 (PA1-24894; dilution, 1:500; Thermo Scientific) and CDP138 (kiaa0528) (A301-469A; dilution, 1:1,000; Bethyl Laboratories) were used. Rhodamine-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG then was used to visualize primary antibody-bound UCP1 or CDP138. For CDP138 and TH colocalization studies, mouse monoclonal antibody against TH (MA124654; 1:80 dilution; Fisher-Invitrogen) was used after the completion of CDP138 staining. Fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG was used to visualize primary antibody-bound TH. DAPI (4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole) solution (Thermo Fisher Scientific) was used as the counterstain for nuclei.

Statistical analysis.

For mouse studies, statistical evaluations were performed by unpaired two-tailed Student's t test for two-group comparisons. For comparing more than two groups, an analysis of variance test, followed by a Sidak's test, was applied. All results are presented as means ± standard errors of the means (SEM). The threshold for significant two-tailed P values was set at ≤0.05.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Emily King at SBPMDI for the hyperinsulinemic euglycemic clamp study, Kenneth Walsh (BUSM), Steve Farmer (BUSM), and Paul Cohen (Rockefeller University) for constructive suggestions on the manuscript, and Thomas W. Balon (Boston University School of Medicine Metabolic Phenotyping Core) for helping with the mouse metabolic cage study.

This project was supported by NIH grant R01 DK094025 and a research grant from the American Diabetes Association (7-11-BS-72) to Z.Y.J., by a Boston University CTSI pilot grant (1UL1TR001430) to Q.L.Z., and by an American Diabetes Association minority undergraduate internship (1-17-MUI-006) to M.C.R.

Q.L.Z., Y.S., and Z.Y.J. designed the metabolic cage, euglycemic clamp, and cold challenge studies. Q.L.Z., Y.S., C.-H.H., J.-Y.H., Z.L., A.G.S., L.G., J.Z.D., and M.C.R. performed biochemical, ELISA, and protein and gene expression analyses. Z.Y.J., Q.L.Z., and Z.G. were involved in the early-stage generation of CDP138 KO mice and GTT/ITT studies. J.-Y.H. and X.X. helped maintain the CDP138 KO mice. J.E.A. and the SBPMDI Metabolic Phenotyping Core performed the hyperinsulinemic-euglycemic clamp study. S.Q. helped with experimental design. Z.Y.J. wrote the manuscript with help from Q.L.Z. and J.E.A.

We have no conflicts of interest to declare.

REFERENCES

- 1.Goldstein DS. 2010. Adrenal responses to stress. Cell Mol Neurobiol 30:1433–1440. doi: 10.1007/s10571-010-9606-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Verberne AJ, Korim WS, Sabetghadam A, Llewellyn-Smith IJ. 2016. Adrenaline: insights into its metabolic roles in hypoglycaemia and diabetes. Br J Pharmacol 173:1425–1437. doi: 10.1111/bph.13458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jocken JW, Blaak EE. 2008. Catecholamine-induced lipolysis in adipose tissue and skeletal muscle in obesity. Physiol Behav 94:219–230. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2008.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Langin D. 2006. Adipose tissue lipolysis as a metabolic pathway to define pharmacological strategies against obesity and the metabolic syndrome. Pharmacol Res 53:482–491. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2006.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Collins S, Cao W, Robidoux J. 2004. Learning new tricks from old dogs: beta-adrenergic receptors teach new lessons on firing up adipose tissue metabolism. Mol Endocrinol 18:2123–2131. doi: 10.1210/me.2004-0193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Watt MJ, Steinberg GR. 2008. Regulation and function of triacylglycerol lipases in cellular metabolism. Biochem J 414:313–325. doi: 10.1042/BJ20080305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zimmermann R, Lass A, Haemmerle G, Zechner R. 2009. Fate of fat: the role of adipose triglyceride lipase in lipolysis. Biochim Biophys Acta 1791:494–500. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2008.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Anthonsen MW, Ronnstrand L, Wernstedt C, Degerman E, Holm C. 1998. Identification of novel phosphorylation sites in hormone-sensitive lipase that are phosphorylated in response to isoproterenol and govern activation properties in vitro. J Biol Chem 273:215–221. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.1.215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Miyoshi H, Souza SC, Zhang HH, Strissel KJ, Christoffolete MA, Kovsan J, Rudich A, Kraemer FB, Bianco AC, Obin MS, Greenberg AS. 2006. Perilipin promotes hormone-sensitive lipase-mediated adipocyte lipolysis via phosphorylation-dependent and -independent mechanisms. J Biol Chem 281:15837–15844. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M601097200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Granneman JG, Moore HP. 2008. Location, location: protein trafficking and lipolysis in adipocytes. Trends Endocrinol Metab 19:3–9. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2007.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chakrabarti P, Kandror KV. 2011. Adipose triglyceride lipase: a new target in the regulation of lipolysis by insulin. Curr Diabetes Rev 7:270–277. doi: 10.2174/157339911796397866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zechner R, Kienesberger PC, Haemmerle G, Zimmermann R, Lass A. 2009. Adipose triglyceride lipase and the lipolytic catabolism of cellular fat stores. J Lipid Res 50:3–21. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R800031-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zimmermann R, Strauss JG, Haemmerle G, Schoiswohl G, Birner-Gruenberger R, Riederer M, Lass A, Neuberger G, Eisenhaber F, Hermetter A, Zechner R. 2004. Fat mobilization in adipose tissue is promoted by adipose triglyceride lipase. Science 306:1383–1386. doi: 10.1126/science.1100747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zechner R, Zimmermann R, Eichmann TO, Kohlwein SD, Haemmerle G, Lass A, Madeo F. 2012. FAT SIGNALS–lipases and lipolysis in lipid metabolism and signaling. Cell Metab 15:279–291. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2011.12.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tseng YH, Cypess AM, Kahn CR. 2010. Cellular bioenergetics as a target for obesity therapy. Nat Rev Drug Discov 9:465–482. doi: 10.1038/nrd3138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cannon B, Nedergaard J. 2004. Brown adipose tissue: function and physiological significance. Physiol Rev 84:277–359. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00015.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nedergaard J, Bengtsson T, Cannon B. 2007. Unexpected evidence for active brown adipose tissue in adult humans. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 293:E444–E452. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00691.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cypess AM, Lehman S, Williams G, Tal I, Rodman D, Goldfine AB, Kuo FC, Palmer EL, Tseng YH, Doria A, Kolodny GM, Kahn CR. 2009. Identification and importance of brown adipose tissue in adult humans. N Engl J Med 360:1509–1517. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0810780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Virtanen KA, Lidell ME, Orava J, Heglind M, Westergren R, Niemi T, Taittonen M, Laine J, Savisto NJ, Enerback S, Nuutila P. 2009. Functional brown adipose tissue in healthy adults. N Engl J Med 360:1518–1525. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0808949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wu J, Cohen P, Spiegelman BM. 2013. Adaptive thermogenesis in adipocytes: is beige the new brown? Genes Dev 27:234–250. doi: 10.1101/gad.211649.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu D, Bordicchia M, Zhang C, Fang H, Wei W, Li JL, Guilherme A, Guntur K, Czech MP, Collins S. 2016. Activation of mTORC1 is essential for beta-adrenergic stimulation of adipose browning. J Clin Investig 126:1704–1716. doi: 10.1172/JCI83532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Barquissau V, Beuzelin D, Pisani DF, Beranger GE, Mairal A, Montagner A, Roussel B, Tavernier G, Marques MA, Moro C, Guillou H, Amri EZ, Langin D. 2016. White-to-brite conversion in human adipocytes promotes metabolic reprogramming towards fatty acid anabolic and catabolic pathways. Mol Metab 5:352–365. doi: 10.1016/j.molmet.2016.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Saito M, Okamatsu-Ogura Y, Matsushita M, Watanabe K, Yoneshiro T, Nio-Kobayashi J, Iwanaga T, Miyagawa M, Kameya T, Nakada K, Kawai Y, Tsujisaki M. 2009. High incidence of metabolically active brown adipose tissue in healthy adult humans: effects of cold exposure and adiposity. Diabetes 58:1526–1531. doi: 10.2337/db09-0530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Barbatelli G, Murano I, Madsen L, Hao Q, Jimenez M, Kristiansen K, Giacobino JP, De Matteis R, Cinti S. 2010. The emergence of cold-induced brown adipocytes in mouse white fat depots is determined predominantly by white to brown adipocyte transdifferentiation. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 298:E1244–E1253. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00600.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rosenwald M, Perdikari A, Rulicke T, Wolfrum C. 2013. Bi-directional interconversion of brite and white adipocytes. Nat Cell Biol 15:659–667. doi: 10.1038/ncb2740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rosen ED, Spiegelman BM. 2014. What we talk about when we talk about fat. Cell 156:20–44. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.12.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cohen P, Levy JD, Zhang Y, Frontini A, Kolodin DP, Svensson KJ, Lo JC, Zeng X, Ye L, Khandekar MJ, Wu J, Gunawardana SC, Banks AS, Camporez JP, Jurczak MJ, Kajimura S, Piston DW, Mathis D, Cinti S, Shulman GI, Seale P, Spiegelman BM. 2014. Ablation of PRDM16 and beige adipose causes metabolic dysfunction and a subcutaneous to visceral fat switch. Cell 156:304–316. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.12.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Harms M, Seale P. 2013. Brown and beige fat: development, function and therapeutic potential. Nat Med 19:1252–1263. doi: 10.1038/nm.3361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sidossis L, Kajimura S. 2015. Brown and beige fat in humans: thermogenic adipocytes that control energy and glucose homeostasis. J Clin Investig 125:478–486. doi: 10.1172/JCI78362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schulz TJ, Huang P, Huang TL, Xue R, McDougall LE, Townsend KL, Cypess AM, Mishina Y, Gussoni E, Tseng YH. 2013. Brown-fat paucity due to impaired BMP signalling induces compensatory browning of white fat. Nature 495:379–383. doi: 10.1038/nature11943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shabalina IG, Petrovic N, de Jong JM, Kalinovich AV, Cannon B, Nedergaard J. 2013. UCP1 in brite/beige adipose tissue mitochondria is functionally thermogenic. Cell Rep 5:1196–1203. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.10.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Keipert S, Jastroch M. 2014. Brite/beige fat and UCP1–is it thermogenesis? Biochim Biophys Acta 1837:1075–1082. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2014.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McDonald ME, Li C, Bian H, Smith BD, Layne MD, Farmer SR. 2015. Myocardin-related transcription factor A regulates conversion of progenitors to beige adipocytes. Cell 160:105–118. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Xie X, Gong Z, Mansuy-Aubert V, Zhou QL, Tatulian SA, Sehrt D, Gnad F, Brill LM, Motamedchaboki K, Chen Y, Czech MP, Mann M, Kruger M, Jiang ZY. 2011. C2 domain-containing phosphoprotein CDP138 regulates GLUT4 insertion into the plasma membrane. Cell Metab 14:378–389. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2011.06.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kim JY, van de Wall E, Laplante M, Azzara A, Trujillo ME, Hofmann SM, Schraw T, Durand JL, Li H, Li G, Jelicks LA, Mehler MF, Hui DY, Deshaies Y, Shulman GI, Schwartz GJ, Scherer PE. 2007. Obesity-associated improvements in metabolic profile through expansion of adipose tissue. J Clin Investig 117:2621–2637. doi: 10.1172/JCI31021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shimizu I, Aprahamian T, Kikuchi R, Shimizu A, Papanicolaou KN, MacLauchlan S, Maruyama S, Walsh K. 2014. Vascular rarefaction mediates whitening of brown fat in obesity. J Clin Investig 124:2099–2112. doi: 10.1172/JCI71643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mansuy-Aubert V, Zhou QL, Xie X, Gong Z, Huang JY, Khan AR, Aubert G, Candelaria K, Thomas S, Shin DJ, Booth S, Baig SM, Bilal A, Hwang D, Zhang H, Lovell-Badge R, Smith SR, Awan FR, Jiang ZY. 2013. Imbalance between neutrophil elastase and its inhibitor alpha1-antitrypsin in obesity alters insulin sensitivity, inflammation, and energy expenditure. Cell Metab 17:534–548. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2013.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ayala JE, Bracy DP, Malabanan C, James FD, Ansari T, Fueger PT, McGuinness OP, Wasserman DH. 2011. Hyperinsulinemic-euglycemic clamps in conscious, unrestrained mice. J Vis Exp 57:3188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ayala JE, Bracy DP, McGuinness OP, Wasserman DH. 2006. Considerations in the design of hyperinsulinemic-euglycemic clamps in the conscious mouse. Diabetes 55:390–397. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.55.02.06.db05-0686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Herzig S, Long F, Jhala US, Hedrick S, Quinn R, Bauer A, Rudolph D, Schutz G, Yoon C, Puigserver P, Spiegelman B, Montminy M. 2001. CREB regulates hepatic gluconeogenesis through the coactivator PGC-1. Nature 413:179–183. doi: 10.1038/35093131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Altarejos JY, Montminy M. 2011. CREB and the CRTC co-activators: sensors for hormonal and metabolic signals. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 12:141–151. doi: 10.1038/nrm3072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chapman ER. 2002. Synaptotagmin: a Ca(2+) sensor that triggers exocytosis? Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 3:498–508. doi: 10.1038/nrm855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Debodo RC, Steele R, Altszuler N, Dunn A, Bishop JS. 1963. On the Hormonal regulation of carbohydrate metabolism; studies with C14 glucose. Recent Prog Horm Res 19:445–488. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Steele R, Wall JS, De Bodo RC, Altszuler N. 1956. Measurement of size and turnover rate of body glucose pool by the isotope dilution method. Am J Physiol 187:15–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ayala JE, Bracy DP, Julien BM, Rottman JN, Fueger PT, Wasserman DH. 2007. Chronic treatment with sildenafil improves energy balance and insulin action in high fat-fed conscious mice. Diabetes 56:1025–1033. doi: 10.2337/db06-0883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kraegen EW, James DE, Jenkins AB, Chisholm DJ. 1985. Dose-response curves for in vivo insulin sensitivity in individual tissues in rats. Am J Physiol 248:E353–E362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bruning JC, Michael MD, Winnay JN, Hayashi T, Horsch D, Accili D, Goodyear LJ, Kahn CR. 1998. A muscle-specific insulin receptor knockout exhibits features of the metabolic syndrome of NIDDM without altering glucose tolerance. Mol Cell 2:559–569. doi: 10.1016/S1097-2765(00)80155-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Huang JY, Zhou QL, Huang CH, Song Y, Sharma AG, Liao Z, Zhu K, Massidda MW, Jamieson RR, Zhang JY, Tenen DG, Jiang ZY. 2017. Neutrophil elastase regulates emergency myelopoiesis preceding systemic inflammation in diet-induced obesity. J Biol Chem 292:4770–4776. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C116.758748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ayala JE, Bracy DP, Hansotia T, Flock G, Seino Y, Wasserman DH, Drucker DJ. 2008. Insulin action in the double incretin receptor knockout mouse. Diabetes 57:288–297. doi: 10.2337/db07-0704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]