Abstract

Background

Compared with other general energy crops, microalgae are more compatible with desert conditions. In addition, microalgae cultivated in desert regions can be used to develop biodiesel. Therefore, screening oil-rich microalgae, and researching the algae growth, CO2 fixation and oil yield in desert areas not only effectively utilize the idle desertification lands and other resources, but also reduce CO2 emission.

Results

Monoraphidium dybowskii LB50 can be efficiently cultured in the desert area using light resources, and lipid yield can be effectively improved using two-stage induction and semi-continuous culture modes in open raceway ponds (ORPs). Lipid content (LC) and lipid productivity (LP) were increased by 20% under two-stage industrial salt induction, whereas biomass productivity (BP) increased by 80% to enhance LP under semi-continuous mode in 5 m2 ORPs. After 3 years of operation, M. dybowskii LB50 was successfully and stably cultivated under semi-continuous mode for a month during five cycles of repeated culture in a 200 m2 ORP in the desert area. This culture mode reduced the supply of the original species. The BP and CO2 fixation rate were maintained at 18 and 33 g m−2 day−1, respectively. Moreover, LC decreased only during the fifth cycle of repeated culture. Evaporation occurred at 0.9–1.8 L m−2 day−1, which corresponded to 6.5–13% of evaporation loss rate. Semi-continuous and two-stage salt induction culture modes can reduce energy consumption and increase energy balance through the energy consumption analysis of life cycle.

Conclusion

This study demonstrates the feasibility of combining biodiesel production and CO2 fixation using microalgae grown as feedstock under culture modes with ORPs by using the resources in the desert area. The understanding of evaporation loss and the sustainability of semi-continuous culture render this approach practically viable. The novel strategy may be a promising alternative to existing technology for CO2 emission reduction and biofuel production.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s13068-018-1068-1) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Microalgae, Lipid production, Semi-continuous culture, CO2 fixation, Open raceway ponds, Desert area, Evaporation

Background

Renewable and environmentally friendly alternative fuels are urgently needed for future industrial development, because of the diminishing world oil reserves and the environmental deterioration associated with fossil fuel consumption [1, 2]. Microalgae are increasingly considered as feedstock for next-generation biofuel production because of their many excellent characteristics, such as broad environmental adaptability, short growth period, high photosynthetic efficiency, and high-quality lipid [3, 4]. However, the commercial feasibility of microalgal biodiesel is limited because only few microalgal strains can be grown reliably with high lipid content (LC) outdoors. Lipid productivity (LP) under outdoor conditions is significantly lower than that in the laboratory due to pollution from other microorganisms and fluctuations in environmental parameters [5–7]. Large-scale outdoor cultivation using sunlight is the only solution for the sustainable industrial production of microalgal biofuel [8]. Therefore, an essential prerequisite to achieve the industrial-scale application of microalgal biofuel is the selection of robust and highly productive microalgal strains with relatively high LC outdoors.

Two cultivation systems are commonly used for large-scale outdoor microalgal cultivation: the open system (e.g., open raceway ponds, ORPs) and the closed photobioreactor system (e.g., tubular, flat plate or column photobioreactors) [1, 9–11]. Compared with closed photobioreactors, ORPs consume less energy and require lower investment and production costs for microalgal cultivation [12]. Although microalgal cultivation in ORPs offers many advantages, the high cost of cultivation systems impedes the commercialization for lipid production. Thus, developing an economically feasible culture mode to increase the lipid production and thereby reduce cultivation costs is necessary [7, 13].

Increasing LP via culture modes can reduce the costs and enhance the economic feasibility of microalgal biodiesel production. The photoautotrophic two-stage cultivation mode is a highly promising approach to increase lipid production in photobioreactors by improving LCs [14–16]. However, only few studies have employed this mode in ORPs [17]. The semi-continuous mode is a simple and efficient strategy to increase lipid production in microalgal biomass by continuously increasing biomass [7, 18]. This mode can avoid a low cell division rate at the early exponential stage and light limitation at the late stationary stage. Furthermore, it maintains the microalgal culture under exponential growth conditions, resulting in enhanced biodiesel production [7]. However, the number of cycles for semi-continuous culture is limited because of the different nutrient consumption rates of algal cells. Thus, exploring the adequate cultivation time of microalgal cells under whole semi-continuous cultivation mode is important to evaluate their survivability.

The large-scale cultivation of microalgae requires large areas of land and water resources. Arid and semiarid regions account for 41% of the global land area [19]. Thus, cultivating microalgae in desertification areas avoids competition with food crops for arable land and water. In addition, the unique climatic conditions (strong solar radiation, long sunshine duration, and large day and night temperature difference) in deserts are beneficial to the accumulation of dry weight (DW) in the cells. Compared with other crops, microalgae are more compatible with desert conditions. Furthermore, cyanobacteria and green microalgae can be stably and efficiently cultivated in desert areas [13, 20, 21]. Therefore, microalgal cultivation is an effective means to utilize desert lands and sunshine.

In the current work, the ability of three microalgae to produce high lipid indoors was determined in a 5 m2 (1000 L) ORP to select for high environmental adaptability and lipid accumulation capability in the desert area. The influences of two-stage cultivation mode and semi-continuous mode on cell growth, CO2 fixation rate, and evaporation rate were first investigated under 5 m2 (1000 L) ORP. Algal strain growth was scaled up to a 200 m2 (40,000 L) ORP with semi-continuous mode to determine cycle times. Outdoor cultivation test at different times was conducted to assess the stability of the algal strain in long-term semi-continuous operations. Finally, the energy consumption of life cycle was analyzed to assess the feasibility of biodiesel production and CO2 mitigation in desert area.

Methods

Organism

Monoraphidium dybowskii LB50 and Micractinium sp. XJ-2 were provided by Prof. Xudong Xu of the Institute of Hydrobiology, the Chinese Academy of Sciences. Podohedriella falcata XJ-176 was isolated from Xinjiang Taxi River Reservoir (Additional file 1: Figure S1). The stock cultures were maintained indoors in a sterilized BG11 medium containing 1.5 g NaNO3, 40 mg K2HPO4, 75 mg MgSO4·7H2O, 20 mg Na2CO3, 36 mg CaCl2·2H2O, 6 mg ammonium ferric citrate, 6 mg ammonium citrate monohydrate, 1 mg EDTA, 2.86 μg H3BO3, 1.81 μg MnCl2·4H2O, 0.222 μg ZnSO4·7H2O, 0.39 μg Na2MoO4·2H2O, 0.079 μg CuSO4·5H2O, and 0.050 μg CoCl2·6H2O in 1 L water.

Experimental setup

All experiments were conducted in the Dalate Banner of Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region at the East edge of Hobq Desert (40°22′23.4″N 109°50′57.7″E) for 3 years (Additional file 1: Figure S1). Two scales of ORPs at 5 and 200 m2 were utilized. The length, width, and maximum depth were 4.80, 1.05, and 0.60 m and 34.50, 5.80, and 0.60 m in 5 and 200 m2 illuminated areas of ORP, respectively (Additional file 1: Figure S1). The culture depth in raceway ponds was set to 20 cm, with 1000 and 40,000 L culture volumes. A stainless steel paddlewheel, 0.80 m in diameter, was used for the circulation of the cultures in 5 and 200 m2 ORPs at 0.35 and 0.25 m s−1, respectively. Microalgae were cultivated using a modified BG11 medium containing 0.25 g L−1 urea, but 0.1 M NaHCO3 was added to the medium used for M. dybowskii LB50. The medium was thoroughly compounded with groundwater. A series of scale-up pre-cultivation was employed (Additional file 1: Figure S1). Water in the system was replenished every day to prevent serious evaporative losses in the open raceway system. Cell concentration measured as an OD680 of 0.1 was inoculated into the culture in 5 and 200 m2 ORPs.

After pre-cultivation, the batch culture was conducted with three microalgae in 5 m2 ORP (1000 L) to select the optimal stain for lipid production.

For two-stage salt induction culture in 5 m2 ORPs, M. dybowskii LB50 was cultivated in 5 m2 ORPs outdoors. On the 10th day, which is at the late-exponential growth phase, NaCl and industrial salts (Hubei Guangyan Lantioan salt chemical co., Ltd, China. Additional file 2: Table S1) were added at final concentrations of 0 and 20 g L−1. Industrial salts, often referred in China to NaCl, NaOH (caustic soda), and Na2CO3 are widely used in the industry. In the current study, the main component of industrial salt was NaCl. Industrial salt can be inexpensive and is easily produced because of the low purity. Day 0 was assumed as the time of salt addition.

For semi-continuous cultivation, further experiments were conducted with semi-continuous mode in two ORP scales. Two-thirds of the culture was harvested, and the remaining culture was used as the seed for subsequent batches and replaced by the same volume of nutrition-rich growth media containing half of the urea concentration. The algal culture was harvested every 3 or 4 days. The semi-continuous experiment was carried out in a 200 m2 ORP for a month.

The water used for algal cultivation was pumped from the ground and contained 89.39 ppm Na+, 62.92 ppm SO42+, and low levels of K+ (1.69 ppm), Mg2+(13.65 ppm), Ca2+ (12.66 ppm), Cl− (24.12 ppm), and NO3− (1.41 ppm) [13].

Analytical procedures

Biomass measurement

Biomass productivity (BP, mg L−1 day−1) was calculated according to Eq. (1):

| 1 |

where B2 and B1 represent the DW biomass density at time t (days) and at the start of the experiment, respectively.

Algal density was determined by measuring the OD680—the optical density of algae at 680 nm. The relationships between the DW (g L−1) and the OD680 values of the algae were described using Eqs. (2–4):

| 2 |

| 3 |

| 4 |

The cells were harvested by centrifugation and baked in an oven.

Lipid analysis

Total lipid was extracted from approximately 80–100 mg of the dried algae (w1) using a Soxhlet apparatus, with chloroform–methanol (1:2, v/v) as the solvent. Total lipid was transferred into a pre-weighed beaker (w2) and blow-dried in a fume cupboard. The lipid was dried to a constant weight in an oven at 10 °C and weighed (w3).

LC (%) and the LP (mg L−1 day−1) were determined according to Eqs. (5, 6):

| 5 |

| 6 |

Determination of urea concentration

Urea concentration was determined following the protocol outlined by Beale and Croft [22]. The liquid sample collected from the raceway pond was filtered using a 0.22 μm-pore filter and then diluted 60-fold with deionized water for each sample. The sample was collected and mixed with 1 volume of diacetylmonoxime–phenylanthranilic acid reagent (1 volume of 1% w/v diacetylmonoxime in 0.02% acetic acid and 1 volume of phenylanthranilic acid in 20% v/v ethanol with 120 mM NaCO3). Exactly, 1 mL of activated acid phosphate (1.3 M NaH2PO4, 10 mM MnCl2, 0.4 mM NaNO3, 0.2 M HCl in 31% v/v H2SO4) was added before incubation in boiling water for 15 min. The tubes were left to cool, and their OD520 were determined using a UV/Vis spectrophotometer.

Determination of pH, irradiance, conductivity, and evaporation

The temperature, conductivity and pH of the culture medium were determined daily by utilizing respective sampling probes (YSI Instruments, Yellow Springs, Ohio, USA). Irradiance was measured with a luxmeter (Hansatech Instruments, Norfolk, UK).

The depth at four fixed positions was determined in the raceway ponds every day, and evaporation (L m−2 day−1) was calculated according to Eq. (7):

| 7 |

where h2 and h1 represent the average depth at time t (days) and at the start of the experiment, respectively. S represents the area of the raceway ponds.

Determination of CO2 fixation rate

According to the mass balance of microalgae, the fixation rate of CO2 (mg L−1 day−1, g m−2 day−1) was calculated from the relationship between the carbon content and volumetric growth rate of the microalgal cell, as indicated in Eq. (8):

| 8 |

where BP is in mg L−1 day−1 or g m−2 day−1; Ccarbon is the carbon content of the biomass (g g−1), as determined by an elemental analyzer (Elementar Vario EL cube); is the molar mass of CO2; and MC is the molar mass of carbon (Additional file 3: Table S2).

Net energy ratio (NER) and energy balances

NER is defined as the ratio of the energy produced over primary energy input as represented in Eq. (9):

| 9 |

On the basis of the data obtained in the 200 m2 ORP for cultivating M. dybowskii LB50 for 1 year, NER is estimated using the method discussed by Jorquera et al. [23].

Energy balance is defined as the difference between energy produced and primary energy input, as represented Eq. (10):

| 10 |

Statistical analysis

The values were expressed as mean ± standard deviation. The data were analyzed by one-way ANOVA using SPSS (version 19.0). Statistically significant difference was considered at p < 0.05.

Results and discussion

Growth, lipid accumulation, and CO2 fixation rate of the three microalgae in 5 m2 ORPs outdoors

Three strains of potential microalgae (Additional file 4: Table S3) were grown in 5 m2 ORPS to evaluate their lipid accumulation and CO2 fixation potential. As shown in Fig. 1, the BPs of M. dybowskii LB50 and Micractinium sp. XJ-2 were both 42 mg L−1 day−1 (8 g m−2 day−1), whereas P. falcata XJ-176 cannot be reliably cultured outdoors. The LC of M. dybowskii LB50 (30%) was higher than that of Micractinium sp. XJ-2 (p < 0.05). Thus, the LP of M. dybowskii LB50 (2.6 g m−2 day−1) was also higher than that of Micractinium sp. XJ-2 (2.28 g m−2 day−1). The CO2 fixation rates of M. dybowskii LB50, Micractinium sp. XJ-2, and P. falcata XJ-176 were 59, 41, and 19 mg L−1 day−1 (12, 8, and 4 g m−2 day−1, Additional file 5: Table S4), respectively. During the time course of culture, CO2 fixation rate was low at the beginning and stable stage and was the highest at the exponential growth stage, reaching 163 mg L−1 day−1. At the late growth stage, CO2 fixation rate was negative, indicating that the microalgal cells did not grow or died, releasing large amounts of CO2 possibly through respiratory metabolism.

Fig. 1.

Biomass, lipid content (a), and CO2 fixation rate (b) of M. dybowskii LB50, Micractinium sp. XJ-2, and P. falcata XJ-176 in 5 m2 ORPs. DW dry weight, LC lipid content

Microbial contamination during large-scale algal cultivation can significantly and consistently reduce biomass production. In this context, eukaryotic contaminants, such as amoebae, ciliates, and rotifers, and clusters of cells based on microscopy were found to cause biomass deterioration in P. falcata XJ-176 cultivation. In the current study, this phenomenon was rarely observed during the cultivation of M. dybowskii LB50 and Micractinium sp. XJ-2. These results showed that the two species demonstrate high environmental tolerance, especially to the high light intensity in the desert (Additional file 6: Figure S2), and could inhibit the excessive growth of bacteria [16, 24]. Consequently, M. dybowskii LB50 exhibited improved lipid accumulation potential outdoors, particularly during cultivation in the desert.

Two-stage induction culture of microalgae

In addition to selecting a fast-growing strain with high LC, improving the LC or biomass to increase lipid yield is also necessary to enhance the economic feasibility of microalgae-based CO2 removal and biodiesel production [13, 16, 25]. LC can be improved through many ways [7, 26], among which two-stage salt induction is very effective [27]. In our previous study, the LC of M. dybowskii LB50 was increased by 10% through NaCl induction in 140 L photobioreactors outdoors [16]. However, few studies on NaCl induction in ORPs have been conducted [17].

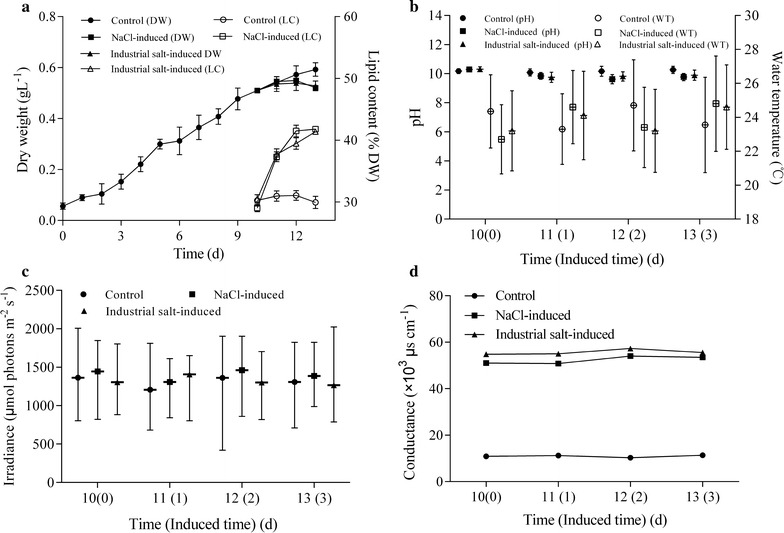

Figure 2 shows that the biomass was not significantly decreased on the first day of NaCl and industrial salt induction (p > 0.05), but was significantly reduced on the third day (p < 0.05). The effect of industrial salt induction on LC was similar to that of NaCl. LC increased by 7% on day 1 of induction and by 10% on day 2 of induction. Thus, LP was 3.3 g m−2 day−1 without significant difference within 1 or 2 days of induction. Only 1 day was required for induction to shorten the culture period. Meanwhile, CO2 fixation rate was 78 mg L−1 day−1 at the time course of induction (Table 1). The pH of the culture liquid did not significantly change, after adding NaCl or industrial salt, but the conductivity increased by five times after adding salt ions (Additional file 2: Table S1). Consequently, the two-stage industrial salt induction culture mode in ORPs favorably increased the LC and reduced the costs.

Fig. 2.

Monoraphidium dybowskii LB50 cultivated via NaCl and industrial salt induction in 5 m2 ORPs. Biomass and lipid content (a), pH and water temperature (b), irradiance (c), and conductance (d)

Table 1.

LC, VBP, ABP, VLP, ALP, and CO2 fixation rate of M. dybowskii LB50 under two-stage induction culture in 5 m2 ORPs

| 0–11 days | 0–12 days | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | NaCl induced | Industrial salt induced | Control | NaCl induced | Inustrial salt induced | |

| LC (%) | 30.95 ± 0.83 | 37.31 ± 0.79 | 37.70 ± 0.89 | 31.05 ± 0.79 | 41.48 ± 0.95 | 39.46 ± 0.94 |

| VBP (mg L−1 day−1) | 44.02 ± 1.90 | 44.46 ± 2.96 | 43.55 ± 2.78 | 43.00 ± 0.54 | 41.04 ± 1.87 | 40.20 ± 0.02 |

| ABP (g m−2 day−1) | 8.80 ± 0.38 | 8.89 ± 0.79 | 8.71 ± 0.56 | 8.60 ± 0.11 | 8.21 ± 0.37 | 8.04 ± 0.09 |

| VLP (mg L−1 day−1) | 13.62 ± 0.16 | 16.59 ± 0.23 | 16.42 ± 0.25 | 13.35 ± 0.04 | 17.02 ± 0.18 | 15.86 ± 0.25 |

| ALP (g m−2 day−1) | 2.72 ± 0.31 | 3.32 ± 0.06 | 3.28 ± 0.49 | 2.67 ± 0.01 | 3.41 ± 0.06 | 3.17 ± 0.01 |

| CO2 fixation rate (mg L−1 day−1) | 78.94 ± 3.40 | 79.74 ± 5.31 | 78.11 ± 4.98 | 77.11 ± 0.96 | 73.59 ± 3.36 | 72.11 ± 1.21 |

| CO2 fixation rate (g m−2 day−1) | 15.79 ± 0.68 | 15.95 ± 1.06 | 15.62 ± 1.00 | 15.42 ± 0.19 | 14.72 ± 0.67 | 14.42 ± 0.09 |

VBP volume biomass productivity, ABP areal biomass productivity, VLP volume lipid productivity, ALP areal lipid productivity, LC lipid content

Two-stage cultivation has been performed in closed photobioreactors outdoors. Tetraselmis sp. and Chlorella sp. were cultured in 120 L closed photobioreactors, and lipid productivities of microalgae were increased by suitable CO2 concentration [11, 28]. Moreover, NaCl induction in the column photobioreactors was favorable [16]. However, these reports have not been verified in ORPs. Kelley [29] reported LC can be increased by using a two-step method involving N deficiency and light conversion in 3 m2 ORPs. LP can also be increased by NaCl induction during dual mode cultivation of mixotrophic microalga in culture tubes [17]. In this study, we confirmed that LC was significantly increased not only in the open runway pool (1000 L), but also with industrial salt induction.

Semi-continuous culture of microalgae

Semi-continuous culture in 5 m2 ORPs

Given its convenient operation and cost-effectiveness, semi-continuous cultivation is also a good choice [30]. Semi-continuous cultivation has attracted considerable attention in energy microalgae [7, 18, 31]. Unfortunately, the culture medium used in semi-continuous cultivation cannot be reused for an unlimited number of times because of the difference in nutrients consumption rate of cells. Portions of the nutrient concentration excessively increase with culture time and eventually inhibit cell growth.

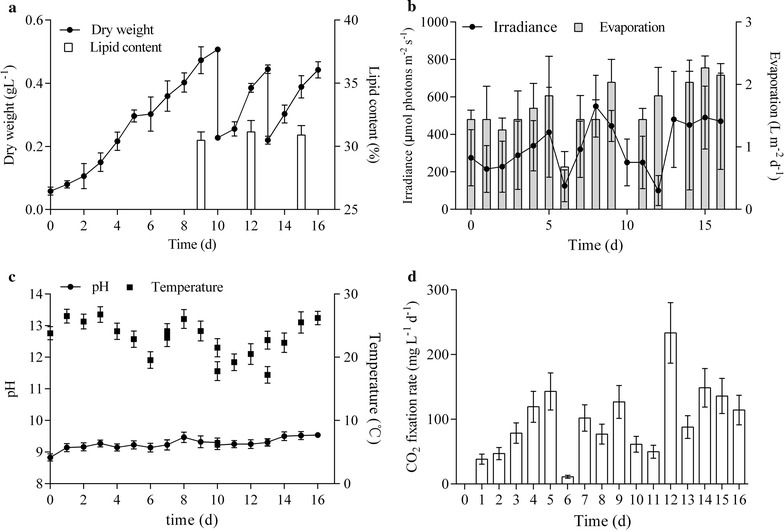

In the 1000 L ORP, the BP increased from 44.86 to 74.16 mg L−1 day−1 after repeated culture, and the LC remained stable at 30% in M. dybowskii LB50 (Fig. 3). Finally, areal LP (ALP) increased from 2.73 to 4.58 g m−2 day−1 (Table 2), and the CO2 fixation rate increased from 16.1 to 26.7 g m−2 day−1 after repeated culture. During the whole semi-continuous culture, the CO2 fixation rate reached 23 g m−2 day−1 (114 mg L−1 day−1). The pH of the culture medium did not significantly change (9.14–9.52, Fig. 3c), indicating that the growth consistently improved throughout the semi-continuous culture. However, the fluctuations in light intensity and temperature were large. Increased illumination and prolonged periods of light exposure were favorable factors for microalgal culture in desert areas, but high evaporation due to increased illumination was unfavorable. Evaporation occurred at 1.62 L m−2 day−1 (Fig. 3). The minimum amount of evaporation was 0.68 L m−2 day−1 at low temperature and light intensity (day 6, rainy day), whereas the highest evaporation rate was 2.26 L m−2 day−1 at high temperature and light intensity in the 5 m2 ORP.

Fig. 3.

Biomass and lipid content (a), irradiance and evaporation (b), pH and water temperature (c), and CO2 fixation rate (d) of M. dybowskii LB50 under semi-continuous mode in the 5 m2 ORP. DW dry weight, LC lipid content

Table 2.

LC, VBP, ABP, VLP, ALP, and CO2 fixation rate of M. dybowskii LB50 under semi-continuous mode in 5 m2 ORPs

| 0–10 days | 11–13 days | 14–16 days | 0–16 days | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LC (%) | 30.48 ± 0.67 | 31.15 ± 0.89 | 30.9 ± 0.74 | 30.84 ± 0.34 |

| VBP (mg L−1 day−1) | 44.86 ± 2.1 | 72.32 ± 3.51 | 74.16 ± 2.25 | 63.78 ± 3.05 |

| ABP (g m−2 day−1) | 8.97 ± 0.23 | 14.46 ± 0.19 | 14.83 ± 0.26 | 12.75 ± 0.23 |

| VLP (mg L−1 day−1) | 13.67 ± 0.64 | 22.53 ± 1.09 | 22.87 ± 0.7 | 19.66 ± 0.94 |

| ALP (g m−2 day−1) | 2.73 ± 0.07 | 4.51 ± 0.06 | 4.58 ± 0.08 | 3.93 ± 0.07 |

| CO2 fixation rate (mg L−1 day−1) | 80.54 ± 3.77 | 129.87 ± 6.29 | 133.65 ± 4.04 | 114.47 ± 5.47 |

| CO2 fixation rate (g m−2 day−1) | 16.09 ± 0.41 | 24.75 ± 0.34 | 26.73 ± 0.47 | 23.1 ± 0.41 |

The two-stage induction culture exhibited slightly higher LP than the semi-continuous culture in the same culture time in a 5 m2 ORP. However, the semi-continuous culture was more favorable for CO2 emission reduction than the two-stage induction culture. The semi-continuous culture prolonged culture period to reduce the supply of the original species.

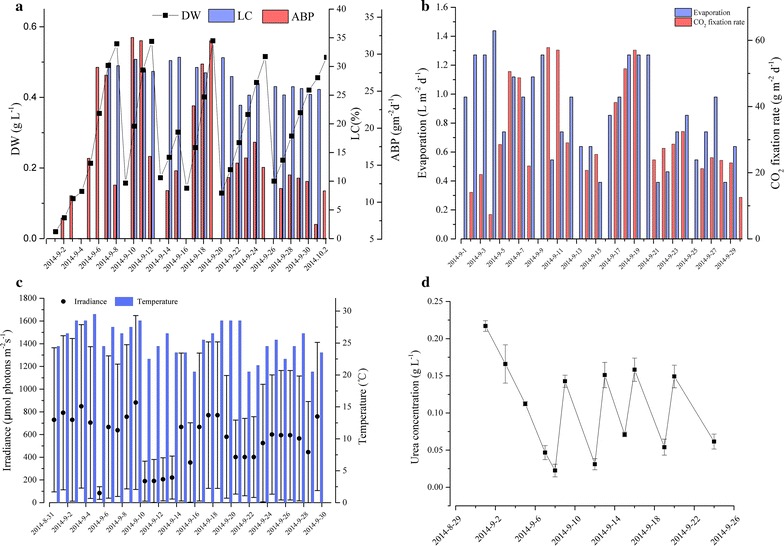

Scaled up semi-continuous cultivation in 200 m2 ORP

Figure 4 shows the semi-continuous culture of M. dybowskii LB50 in a 200 m2 ORP (40,000 L) for a month. BP was 15.2 g m−2 day−1 during the initial growth (0–7 days). The highest BP was 26.8 g m−2 day−1 during the first cycle of semi-continuous culture, but was decreased at the second cycle, because of the rainy days (11–12 days, Fig. 4c). The average biomass productivity was 17 g m−2 day−1 (0–26 days, Table 3) after 1 month of semi-continuous culture at five cycles of replacement. The LC did not significantly change during the four cycles, but significantly decreased at the fifth passage. Therefore, the LP also decreased during fifth passage. The change in CO2 fixation rate was the same as that during biomass production. The average CO2 fixation rate was 30.8 or 33.9 g m−2 day−1 at 0–26 or 0–20 days (Table 3).

Fig. 4.

Time course profiles of dry weight, biomass productivity, lipid content (a), CO2 fixation rate, evaporation (b), water temperature, light intensity (c), and urea concentration (d) of M. dybowskii LB50 grown under semi-continuous mode in the 200 m2 ORP

Table 3.

LC, VBP, ABP, VLP, ALP, and CO2 fixation rate of M. dybowskii LB50 grown under semi-continuous mode in 200 m2 ORP

| LC (%) | VBP (mg L−1 day−1) | ABP (g m−2 day−1) | VLP (mg L−1 day−1) | ALP (g m−2 day−1) | CO2 fixation rate (mg L−1 day−1) | CO2 fixation rate (g m−2 day−1) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0–7 days | 30.38 ± 0.35 | 76.02 ± 46.42 | 15.21 ± 9.28 | 23.09 ± 1.62 | 4.62 ± 0.33 | 136.35 ± 83.08 | 27.27 ± 16.64 |

| 8–10 days | 29.96 ± 1.31 | 133.79 ± 45.77 | 26.76 ± 9.15 | 40.08 ± 5.99 | 8.01 ± 1.19 | 239.93 ± 82.08 | 47.98 ± 16.41 |

| 11–12 days | 31.33 ± 0.41 | 64.54 ± 9.49 | 12.91 ± 1.89 | 20.22 ± 0.37 | 4.04 ± 0.08 | 115.73 ± 17.03 | 23.14 ± 3.41 |

| 13–15 days | 29.37 ± 0.66 | 139.17 ± 22.27 | 27.83 ± 4.45 | 40.87 ± 1.49 | 8.17 ± 0.29 | 249.57 ± 39.95 | 49.92 ± 7.99 |

| 16–20 days | 27.01 ± 3.66 | 77.40 ± 8.80 | 15.48 ± 1.97 | 20.91 ± 3.61 | 4.18 ± 0.72 | 138.81 ± 15.79 | 27.76 ± 3.15 |

| 21–26 days | 25.58 ± 0.62 | 58.44 ± 12.17 | 11.69 ± 2.43 | 14.95 ± 0.75 | 1.99 ± 0.15 | 104.81 ± 21.82 | 20.96 ± 4.36 |

| 0–20 days | 29.61 ± 1.62 | 94.41 ± 4.37 | 18.88 ± 2.73 | 27.95 ± 0.07 | 5.59 ± 0.04 | 169.29 ± 78.33 | 33.86 ± 15.67 |

| 0–26 days | 28.44 ± 1.27 | 85.77 ± 17.49 | 17.15 ± 3.49 | 24.39 ± 2.12 | 4.88 ± 0.42 | 153.82 ± 31.31 | 30.76 ± 6.29 |

Evaporation occurred at 0.88 ± 0.31 L m−2 day−1 in the 200 m2 ORP, and the maximal evaporation rate was 1.44 L m−2 day−1 under high light intensity (128–1568 μmol m−2 s−1). Even during a rainy day, minimal evaporation loss of 0.39 m−2 day−1, which included the leakages and washout of the ORP, was found. Therefore, the average daily evaporation loss rate was 0.44%, and evaporation loss rate was 8.8–11.44% during the whole semi-continuous culture. Figure 4d shows that a small amount of urea can accumulate after each cycle of replacement. The accumulation of urea in the medium reached 0.05 g L−1 until the fourth cycle of semi-continuous culture. These results suggested that the growth and lipid of cells were affected by the accumulation of partial nutrients and the remaining death cells in the media as cycle times increased. Therefore, five cycles of repeated culture were conducted in this study. However, further scalable work can be continued for long-term cultivation with additional repeated times, considering the good performance observed in M. dybowskii LB50.

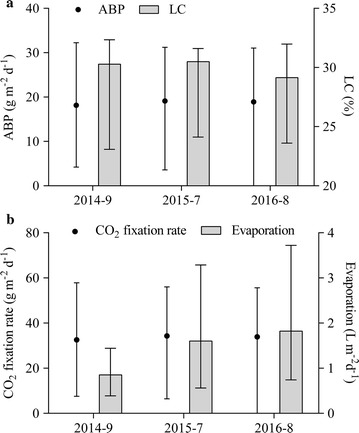

Three semi-continuous cultures of M. dybowskii LB50 in a 200 m2 ORP were performed thrice in September 2014, July 2015, and August 2016 (Fig. 5). M. dybowskii LB50 could exhibit stable growth for a month with semi-continuous culture. The biomass and LC were maintained at 18–20 g m−2 day−1 and 30%, respectively. The CO2 fixation rate remained at 33 g m−2 day−1, but the evaporation exhibited increased difference in various months. The evaporation rates were 0.39–1.44 L m−2 day−1 ( = 0.9 L m−2 day−1), 0.56–3.29 L m−2 day−1 ( = 1.6 L m−2 day−1), and 0.74–3.72 L m−2 day−1 ( = 1.8 L m−2 day−1) in September 2014, July 2015, and August 2016. The evaporation loss rate of a semi-continuous culture is 6.5–13%. Water resources are a potential limitation for microalgal culture, but evaporation affects its scale and sustainability [32]. Furthermore, regions with high BP receive high solar irradiance and thus result in high evaporation rates [33]. Evaporation of the ponds was assumed to occur at a rate of 0.4 cm day−1 (0.4 L m−2 day−1) [34]. In this case, further work on the water cyclic utilization and evaporation reduction can be conducted for sustainable cultivation because of the increased evaporation.

Fig. 5.

Biomass productivity and lipid content (a), CO2 fixation rate and evaporation (b) of M. dybowskii LB50 under 200 m2 ORP in 3 years

Replacement ratio or dilution ratio, the volume ratio of new medium to total culture, is an important parameter in semi-continuous culture because it influences microalgae growth and cell the biochemical components. Ho et al. [35] reported that BP increases with replacement ratio, but lipid causes the opposite effect. The 90% replacement group exhibited the highest overall LP among five replacement ratios (10, 30, 50, 70, and 90%). Some studies reported that a semi-batch process with a 50% medium replacement ratio is suitable for microalgal biomass production and CO2 fixation [13, 36]. In the current study, the LC was unaffected by the 2/3 replacement ratio mainly because of the high and long duration of light in the desert. Although the microalgal concentration in the reactor was not high, cells could grow rapidly.

Cycle time is another parameter affecting the continuity of semi-continuous culture. Previously, five to six cycles of repeated semi-continuous culture were conducted and resulted in inhibited growth or decreased LC [35, 37]. The LC of Desmodesmus sp. F2 significantly decreased at the sixth repeated cycle when five replacement ratios were adopted for semi-continuous cultivation for six repeated cycles [35]. In the 2/3 replacement test, the LC remained high throughout the five-cycle repeated course in 200 m2 ORPs.

Table 4 shows the LP of microalgae in large-scale culture outdoors. The largest scale was implemented in the cultivation of N. salina in the USA, and LP was 10.7 m3 ha−1 year−1 [38], followed by the cultivation of M. dybowskii LB50, Graesiella sp. WBG-1, and M. dybowskii Y2 in 200 m2 ORPs (40,000 L). The LPs (5.3 g m−2 day−1) of M. dybowskii LB50 and M. dybowskii Y2 were higher than those of Graesiella sp. WBG-1 (2.9 g m−2 day−1) and the others in ORPs and tubular photobioreactors. Increased CO2 fixation ability (CO2 fixation rate of 34 g m−2 day−1) was obtained under semi-continuous modes with ORPs in the desert area (Table 4). These results indicated that high biomass production was obtained and CO2 mitigation was feasible by microalgal culture in the desert. The volumetric LP (VLP) in ORPs was lower than that in photobioreactors (Table 4). Finally, all types of bioreactors must focus on the ALP in microalgae industry applications. In brief, the semi-continuous mode in ORPs is more practical than other operation modes in other bioreactors for long-term cultivation. Thus, it is suitable for oleaginous microalgae industry applications because it is economic, convenient, and demonstrates high ALP.

Table 4.

Comparisons of biomass and lipid productivity of different sizes in some microalgae outdoors (culture volume > 100 L)

| Strains | LC (%) | VBP (mg L−1 day−1) | ABP (g m−2 day−1) | VLP (mg L−1 day−1) | ALP (g m−2 day−1) | CO2 fixation rate | Bioreactor volume (L) | Culture | Location | References | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (mg L−1 day−1) | (g m−2 day−1) | ||||||||||

| N. gaditana | 18.6 | 590 | 15.4 | 110 | 2.9 | 1109a | 28.9 | TPs (340) | Dilution rate | Spain | [14] |

| 17.1 | 460 | 12.1 | 78.7 | 2.1 | 864.8a | 22.8 | Nutrient | ||||

| Nannochloropsis sp. | 43 | 256 | 110 | 481.3a | GWP (590) | Nitrogen | Italy | [41] | |||

| Chlorella sp. | 34.8 | 238 | 83 | 447a | BPs (120) | Batch | Australia | [11] | |||

| T. suecica | 32 | 51.5 | 14.8 | 97a | CO2 | [28] | |||||

| S. obliquus | 13.4 | 135 | 11.3 | 19 | 1.6 | 253.8a | 21.3 | HTP (500) | Semi-continuous | UK | [42] |

| Nannochloropsis sp. | 28 | 16.75 | 4.69 | 31.50a | RCS (8000) | Flue gas | Shandong, China | [43] | |||

| C. sp. FC2 IITG | 35.12 | 44.00 | 9.70 | 10.70 | 3.80 | 82.70a | 18.20 | OPs (300, 1.4 m2) | CO2 | India | [15] |

| S. rubescens | 13.8 | 4 | 0.6 | 7.6 | RCS (9000) | Normal | USA | [44] | |||

| N. salina | 16.33 | 204.2 | 24.5 | 33.3 | 4 | 383.9a | 46.1 | RCS (300) | CO2 | Israel | [45] |

| N. salina | 34.7 | 160 | 55.5 | 300.8a | AGSp (174,000) | Normol | USA | [46] | |||

| B. braunii TN101 | 169 | 33.8 | 8.2-13.0 | 317.7a | 63.5 | RCS (5000, 25 m2) | Semi-continuous | Malaysia | [10] | ||

| B. braunii | 24 | 100 | 24c | 188a | RCS (80) | Batch | India | [47] | |||

| Graesiella sp. | 31.8 | 43.5 | 8.7 | 14.5 | 2.9 | 81.8a | 16.4 | RCS (40,000, 200 m2) | Batch (CO2) | Yunnan, China | [5] |

| N. gaditana | 25.6 | 190 | 10.3–22.4 | 30.4 | 2.6–5.7 | 357.2a | 19.4 | RCS (792, 7.2 m2) | Continuous | Spain | [48] |

| S. acutus LB0414 | 21.5 | 42.9 | 3.5 | 9.2 | 0.8 | 80.7a | 6.6 | RCS (2278, 10 m2) | Batch | USA | [49] |

| Tetraselmis sp. | 34.9 | 243 | 48.6 | 85 | 17 | 456.8a | 31.9 | RCS (200, 1 m2) | Batch | Australia | [50] |

| S. obliquus CNW-N (summer) | 205.1 | 83.9d | 358.8b | Tubular (60) | Batch | Taiwan, China | [51] | ||||

| S. obliquus CNW-N (winter) | 119.2 | 47.3d | 208.7b | Tubular (60) | Batch | Taiwan, China | |||||

| M. dybowskii Y2 | 29.9 | 89.5 | 17.9 | 26.7 | 5.3 | 148.1b | 29.6 | RCS (40,000, 200 m2) | Semi-continuous | Inner Mongolia, China | [13] |

| M. dybowskii LB50 | 38.6 | 81.4 | 21.7 | 32.5 | 8.6 | 153.1b | 40.8 | Plastic bag (140 L) | NaCl-induced | Beijing, China | [16] |

| 30.34 | 50.1 | 10 | 15.2 | 3 | 89.9b | 18.0 | RCS | Batch | Inner Mongolia, China | This study | |

| 30 | 90.6 | 18.1 | 27.2 | 5.4 | 162.5b | 32.5 | RCS | Semi-continuous | |||

TPs tubular photobioreactors, GWP green wall panel, BPs bag photobioreactors, HTP horizontal tubular photobioreactor, TLP thin-layer photobioreactor, RCS raceway cultivation system, AGSp algae growth system photobioreactor, OPs open ponds

aCalculated from the following equation: CO2 fixation rate = biomass productivity (mg L−1 day−1) × 1.88

bCalculated from the following equation: CO2 fixation rate = biomass productivity (mg L−1 day−1) × C (%) × 44/12

cFor hydrocarbon

dFor carbohydrate

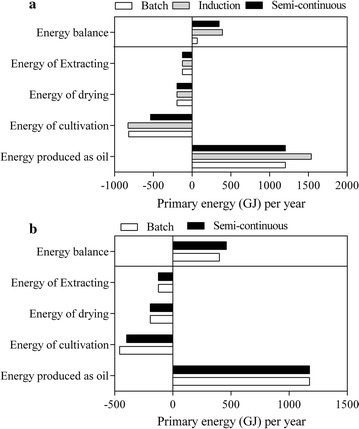

Energy consumption evaluation of outdoor cultivation in different culture modes

The biodiesel production from microalgae involved a course of cultivation, centrifugation, drying, and extraction via a conventional method. We assumed that 100,000 kg dry weight of biomass was produced within the year (270 days). Other parameters were included in our assessment according to the actual operation.

Table 5 shows that the net positive energy for oil production (1.34–2.72) and biomass production (1.41–2.52) in the two-stage salt induction or semi-continuous culture mode was higher than those in the batch mode in 5 m2 ORPs. Moreover, in the 200 m2 ORP, the net positive energy of oil production in the semi-continuous and batch modes was 1.52–2.69, indicating that the semi-continuous culture increased the biomass yield, but not the additional energy consumption. The NER of oil and biomass production increased with a scale-up of the culture system. In addition, the energy demand for producing 1 kg of biodiesel was 14.2–23.3 MJ under semi-continuous mode in 200 m2 ORP.

Table 5.

Comparative energy analyses for biomass or bio-oil production based on 1 year of cultivating M. dybowskii LB50 via different culture modes under OPRs

| Variable | 5 m2 | 200 m2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Batch | Induction | Semi-continuous | Batch | Semi-continuous | |

| Annual biomass production (kg year−1) | 100,000 | 100,000 | 100,000 | 100,000 | 100,000 |

| Volumetric productivity (g L−1 day−1) or (kg m−3day−1)a | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.07 | 0.08 | 0.09 |

| Illuminated areal productivity (kg m−2 day−1)a | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.02 |

| Reactor volume (m3)b | 8413.68 | 8504.49 | 5513.10 | 4700.13 | 4087.97 |

| Occupied area (m2) | 42,087.54 | 42,522.43 | 27,557.32 | 23,500.66 | 20,439.87 |

| Lipid content (%)a | 30.85 | 39.39 | 30.84 | 30.13 | 30.13 |

| Energy consumption for stirring (W m−3)c | 3.72–12.5 | 3.72–12.5 | 3.72–12.5 | 3.72–12.5 | 3.72–12.5 |

| Total energy for stirring (kWh months−1)d | 7511.7–25,241.1 | 7592.8–25,513.4 | 4922.1–16,539.3 | 4196.2–14,100.3 | 3649.7–12,263.9 |

| Total energy for biomass drying (kWh year−1)e | 53,900.00 | 53,900.00 | 53,900.00 | 53,900.00 | 53,900.00 |

| Total energy for oil recovery (kWh year−1)f | 34,534.00 | 34,534.00 | 34,534.00 | 34,534.00 | 34,534.00 |

| Total energy consumption for producing biomass | 437.42–1011.85 | 440.05–1020.68 | 353.52–729.91 | 330–650.89 | 312.29–591.39 |

| Total energy consumption for producing oil (GJ year−1) | 561.74–1136.17 | 564.37–1145 | 477.84–854.24 | 454.32–775.22 | 436.61–715.71 |

| Energy produced as oil (GJ year−1)g | 1204.3 | 1537.8 | 1203.9 | 1176.3 | 1176.3 |

| Energy produced as 100,000 kg biomass (GJ year−1)h | 3155.33 | 3155.33 | 3155.33 | 3155.33 | 3155.33 |

| NER for oil productioni | 2.14–1.06 | 2.72–1.34 | 2.52–1.41 | 2.59–1.52 | 2.69–1.64 |

| NER for biomass production | 7.21–3.12 | 7.17–3.09 | 8.93–4.32 | 9.56–4.85 | 10.1–5.34 |

| Energy consumption for oil (MJ kg−1 bio-oil) | 17.86–36.13 | 14.06–28.52 | 15.2–27.17 | 14.79–25.24 | 14.22–23.3 |

| Energy consumption for oil (MJ MJ−1 bio-oil) | 0.47–0.94 | 0.37–0.74 | 0.4–0.71 | 0.39–0.66 | 0.37–0.61 |

The assumed annual biomass production is 100,000 kg

aData were based on this study

bDetermined by dividing the illuminated area actual by production the volume of each unit

c3.72 W m−3 from Jorquera et al. [23]. 12.5 W m−3 from the actual date for the 200 m2 raceway pond

dIncludes 8 h of daily pumping

eStepan et al. [52]. 539 kWh ton−1 biomass

fStephenson et al. [53]; Gao et al. [54]. 345.34 kWh ton−1 biomass

gEnergy content of net oil yield (assumed value of 39.04 MJ kg−1); Jorquera et al. [23]

hEnergy content of net biomass yield (assumed value of 31.55 MJ kg−1); Jorquera et al. [23]

iNER would be above 1 if including coproduct allocation [55]

Figure 6 shows that the energy consumption of cultivation assumed the highest proportion (55–72%) under any culture mode. The energy balance in the two-stage salt induction culture mode was higher than that in the other methods mainly due to the increase of LC by industrial salt induction to increase the energy produced by oil. The energy produced by oil was 1.27 times larger than that under other modes within the same biomass production (100,000 kg), but the energy balance was only about 10% higher than that under semi-continuous mode. These results demonstrate that the energy consumption of the cultivation process was increased and was reduced by scaling up. The energy balance thus increased after scaling up. Moreover, the energy balance under semi-continuous mode was five times higher than that under batch mode in 5 m2 ORPs and was 1.15 times higher in 200 m2 ORP. Therefore, reducing energy consumption by intermittent agitation or by optimizing mixing, mixing velocity, and paddlewheel must be prioritized to reduce the energy consumption of the entire industrial chain [39].

Fig. 6.

Comparative energy analyses for bio-oil production based on 1 year of M. dybowskii LB50 cultivation via different culture modes in 5 m2 ORPs (a), and 200 m2 ORPs (b). The assumed annual biomass production is 100,000 kg

NER is associated with the type of culture system, and the NER of oil is generally less than 1 in tubular photobioreactors and greater than 1 in ORPs [23]. Ponnusamy et al. [40] reported that the energy demand for producing 1 kg of biodiesel is 28.23 MJ. Only 14–23 MJ was required for 1 kg of biodiesel in this study, which significantly decreased the energy consumption. He et al. [13] reported that the semi-continuous mode reduces the total costs (14.18 and 13.31$ gal−1) by 14.27 and 36.62% compared with the costs of batch mode in M. dybowskii Y2 and Chlorella sp. L1 in the desert area. Therefore, using semi-continuous culture mode with ORPs in the desert area can result in higher biomass, lower energy consumption, and lower costs compared with other culture modes.

Conclusion

Three microalgae were investigated for their environmental tolerances and lipid production potential in ORP outdoors, and M. dybowskii LB50 can be efficiently cultivated using resources in the desert. Lipid production can be improved by using two-stage salt induction and semi-continuous culture modes in ORPs. After 3 years of operation, M. dybowskii LB50 was successfully and stably cultivated under semi-continuous mode for a month (five cycles of repeated culture) in 200 m2 ORPs in the desert, reducing the supply of the original species. The BP and CO2 fixation rates were maintained at 18 and 33 g m−2 day−1, respectively. The LC decreased only during the fifth cycle of repeated culture. Evaporation occurred at 0.9–1.8 L m−2 day−1 (6.5–13% of evaporation loss rate). Finally, using the semi-continuous and two-stage salt induction modes for cultivating M. dybowskii, LB50 can reduce energy consumption and increase energy balance via energy analysis of life cycle. Therefore, M. dybowskii LB50 is a promising candidate for the large-scale, outdoor production of biodiesel feedstock in desert areas. The outdoor ORP cultivation system together with the semi-continuous culture method in desert areas is a suitable strategy to further decrease the cultivation cost and increase the biomass/oil production and CO2 emission potential of M. dybowskii LB50.

Additional files

Additional file 1: Figure S1. Outdoor cultivation system of large-scale raceway ponds.

Additional file 2: Table S1. Ingredients of industrial salt.

Additional file 3: Table S2. Elemental analysis of M. dybowskii LB50, Micractinium sp. XJ-2, and P. falcata XJ-176.

Additional file 4: Table S3. LC, BP, and LP of M. dybowskii LB50, Micractinium sp. XJ-2 and P. falcata XJ-176 cultivated indoors.

Additional file 5: Table S4. LC, VBP, ABP, VLP, ALP, and CO2 fixation rate of M. dybowskii LB50, Micractinium sp. XJ-2, and P. falcata XJ-176 grown in 5 m2 ORPs.

Additional file 6: Figure S2. Irradiance, temperature and pH of three microalgae in 5 m2 ORPs.

Authors’ contributions

HY and CH planned and designed the research and performed the experiments. HY and QH analyzed the data. HY and CH wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by the National 863 program (2013AA065804), the Natural Science Foundation of China (41573111), Science and technology special basic work project (2012FY112900) and Platform construction of oleaginous microalgae (Institute of Hydrobiology, CAS of China). We are indebted to Prof. Xu (Institute of Hydrobiology, CAS of China) for providing us the microalgal strains.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its additional files.

Consent for publication

All authors consent to the publication of the manuscript in Biotechnology for Biofuels. All authors have approved the manuscript to be published.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Funding

This work was funded by National 863 program (2013AA065804), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (41573111), and the Science and technology special basic work project (2012FY112900).

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Abbreviations

- ORP

open raceway pond

- BP

biomass productivity

- DW

dry weight

- LC

lipid content

- LP

lipid productivity

- VBP

volumetric biomass productivity

- ABP

areal biomass productivity

- VLP

volumetric lipid productivity

- ALP

areal lipid productivity

- NER

net energy ratio

- OD

optical density

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s13068-018-1068-1) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Contributor Information

Haijian Yang, Email: hjyang@ihb.ac.cn.

Qiaoning He, Email: heqn9999@163.com.

Chunxiang Hu, Phone: +86-27-68780866, Email: cxhu@ihb.ac.cn.

References

- 1.Rawat I, Kumar RR, Mutanda T, Bux F. Biodiesel from microalgae: a critical evaluation from laboratory to large scale production. Appl Energy. 2013;103:444–467. doi: 10.1016/j.apenergy.2012.10.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rodolfi L, Chini Zittelli G, Bassi N, Padovani G, Biondi N, Bonini G, et al. Microalgae for oil: strain selection, induction of lipid synthesis and outdoor mass cultivation in a low-cost photobioreactor. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2009;102(1):100–112. doi: 10.1002/bit.22033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chisti Y. Biodiesel from microalgae. Biotechnol Adv. 2007;25(3):294–306. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2007.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hu Q, Sommerfeld M, Jarvis E, Ghirardi M, Posewitz M, Seibert M, et al. Microalgal triacylglycerols as feedstocks for biofuel production: perspectives and advances. Plant J. 2008;54(4):621–639. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2008.03492.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wen X, Du K, Wang Z, Peng X, Luo L, Tao H, et al. Effective cultivation of microalgae for biofuel production: a pilot-scale evaluation of a novel oleaginous microalga Graesiella sp. WBG-1. Biotechnol Biofuels. 2016;9(1):123. doi: 10.1186/s13068-016-0541-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liu J, Huang J, Sun Z, Zhong Y, Jiang Y, Chen F. Differential lipid and fatty acid profiles of photoautotrophic and heterotrophic Chlorella zofingiensis: assessment of algal oils for biodiesel production. Bioresour Technol. 2011;102(1):106–110. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2010.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ho SH, Ye X, Hasunuma T, Chang JS, Kondo A. Perspectives on engineering strategies for improving biofuel production from microalgae—a critical review. Biotechnol Adv. 2014;32(8):1448–1459. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2014.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Singh J, Cu S. Commercialization potential of microalgae for biofuels production. Renew Sustain Energy Rev. 2010;14(9):2596–2610. doi: 10.1016/j.rser.2010.06.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kiran B, Kumar R, Deshmukh D. Perspectives of microalgal biofuels as a renewable source of energy. Energy Convers Manag. 2014;88:1228–1244. doi: 10.1016/j.enconman.2014.06.022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ashokkumar V, Agila E, Sivakumar P, Salam Z, Rengasamy R, Ani FN. Optimization and characterization of biodiesel production from microalgae Botryococcus grown at semi-continuous system. Energy Convers Manag. 2014;88:936–946. doi: 10.1016/j.enconman.2014.09.019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moheimani NR. Long-term outdoor growth and lipid productivity of Tetraselmis suecica, Dunaliella tertiolecta and Chlorella sp. (Chlorophyta) in bag photobioreactors. J Appl Phycol. 2013;25(1):167–176. doi: 10.1007/s10811-012-9850-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pires JCM, Alvim-Ferraz MCM, Martins FG, Simoes M. Carbon dioxide capture from flue gases using microalgae: engineering aspects and biorefinery concept. Renew Sustain Energy Rev. 2012;16(5):3043–3053. doi: 10.1016/j.rser.2012.02.055. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.He Q, Yang H, Hu C. Culture modes and financial evaluation of two oleaginous microalgae for biodiesel production in desert area with open raceway pond. Bioresour Technol. 2016;218:571–579. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2016.06.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.San Pedro A, Gonzalez-Lopez CV, Acien FG, Molina-Grima E. Outdoor pilot-scale production of Nannochloropsis gaditana: influence of culture parameters and lipid production rates in tubular photobioreactors. Bioresour Technol. 2014;169:667–676. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2014.07.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Muthuraj M, Kumar V, Palabhanvi B, Das D. Evaluation of indigenous microalgal isolate Chlorella sp. FC2 IITG as a cell factory for biodiesel production and scale up in outdoor conditions. J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol. 2014;41(3):499–511. doi: 10.1007/s10295-013-1397-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yang H, He Q, Rong J, Xia L, Hu C. Rapid neutral lipid accumulation of the alkali-resistant oleaginous Monoraphidium dybowskii LB50 by NaCl induction. Bioresour Technol. 2014;172:131–137. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2014.08.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Venkata Mohan S, Devi MP. Salinity stress induced lipid synthesis to harness biodiesel during dual mode cultivation of mixotrophic microalgae. Bioresour Technol. 2014;165:288–294. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2014.02.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moheimani NR, Borowitzka MA. Increased CO2 and the effect of pH on growth and calcification of Pleurochrysis carterae and Emiliania huxleyi (Haptophyta) in semicontinuous cultures. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2011;90(4):1399–1407. doi: 10.1007/s00253-011-3174-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maestre FT, Escolar C, de Guevara ML, Quero JL, Lázaro R, Delgado-Baquerizo M, et al. Changes in biocrust cover drive carbon cycle responses to climate change in drylands. Glob Change Biol. 2013;19(12):3835–3847. doi: 10.1111/gcb.12306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lan S, Wu L, Yang H, Zhang D, Hu C. A new biofilm based microalgal cultivation approach on shifting sand surface for desert cyanobacterium Microcoleus vaginatus. Bioresour Technol. 2017;238:602–608. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2017.04.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rossi F, Li H, Liu Y, De Philippis R. Cyanobacterial inoculation (cyanobacterisation): perspectives for the development of a standardized multifunctional technology for soil fertilization and desertification reversal. Earth-Sci Rev. 2017;171:28–43. doi: 10.1016/j.earscirev.2017.05.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Beale RN, Croft D. A sensitive method for the colorimetric determination of urea. J Clin Pathol. 1961;14(4):418–424. doi: 10.1136/jcp.14.4.418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jorquera O, Kiperstok A, Sales EA, Embirucu M, Ghirardi ML. Comparative energy life-cycle analyses of microalgal biomass production in open ponds and photobioreactors. Bioresour Technol. 2010;101(4):1406–1413. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2009.09.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sato R, Maeda Y, Yoshino T, Tanaka T, Matsumoto M. Seasonal variation of biomass and oil production of the oleaginous diatom Fistulifera sp. in outdoor vertical bubble column and raceway-type bioreactors. J Biosci Bioeng. 2014;117(6):720–724. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiosc.2013.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Benvenuti G, Bosma R, Ji F, Lamers P, Barbosa MJ, Wijffels RH. Batch and semi-continuous microalgal TAG production in lab-scale and outdoor photobioreactors. J Appl Phycol. 2016;28(6):3167–3177. doi: 10.1007/s10811-016-0897-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Goncalves EC, Wilkie AC, Kirst M, Rathinasabapathi B. Metabolic regulation of triacylglycerol accumulation in the green algae: identification of potential targets for engineering to improve oil yield. Plant Biotechnol J. 2016;14(8):1649–1660. doi: 10.1111/pbi.12523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Xia L, Ge H, Zhou X, Zhang D, Hu C. Photoautotrophic outdoor two-stage cultivation for oleaginous microalgae Scenedesmus obtusus XJ-15. Bioresour Technol. 2013;144:261–267. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2013.06.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moheimani NR. Inorganic carbon and pH effect on growth and lipid productivity of Tetraselmis suecica and Chlorella sp. (Chlorophyta) grown outdoors in bag photobioreactors. J Appl Phycol. 2013;25(2):387–398. doi: 10.1007/s10811-012-9873-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kelley JE. Lipid production by microalgae treating municipal wastewater. 2013.

- 30.Hsieh CH, Wu WT. Cultivation of microalgae for oil production with a cultivation strategy of urea limitation. Bioresour Technol. 2009;100(17):3921–3926. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2009.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ashokkumar V, Agila E, Salam Z, Ponraj M, Din MF, Ani FN. A study on large scale cultivation of Microcystis aeruginosa under open raceway pond at semi-continuous mode for biodiesel production. Bioresour Technol. 2014;172:186–193. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2014.08.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Batan L, Quinn JC, Bradley TH. Analysis of water footprint of a photobioreactor microalgae biofuel production system from blue, green and lifecycle perspectives. Algal Res. 2013;2(3):196–203. doi: 10.1016/j.algal.2013.02.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ishika T, Moheimani NR, Bahri PA. Sustainable saline microalgae co-cultivation for biofuel production: a critical review. Renew Sustain Energy Rev. 2017;78:356–368. doi: 10.1016/j.rser.2017.04.110. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hoffman J, Pate RC, Drennen T, Quinn JC. Techno-economic assessment of open microalgae production systems. Algal Res. 2017;23:51–57. doi: 10.1016/j.algal.2017.01.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ho S-H, Chen C-NN, Lai Y-Y, Lu W-B, Chang J-S. Exploring the high lipid production potential of a thermotolerant microalga using statistical optimization and semi-continuous cultivation. Bioresour Technol. 2014;163:128–135. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2014.04.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ho S-H, Kondo A, Hasunuma T, Chang J-S. Engineering strategies for improving the CO2 fixation and carbohydrate productivity of Scenedesmus obliquus CNW-N used for bioethanol fermentation. Bioresour Technol. 2013;143:163–171. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2013.05.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.da Rosa GM, Moraes L, Cardias BB, de Souza MDR, Costa JA. Chemical absorption and CO2 biofixation via the cultivation of Spirulina in semicontinuous mode with nutrient recycle. Bioresour Technol. 2015;192:321–327. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2015.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Quinn JC, Yates T, Douglas N, Weyer K, Butler J, Bradley TH, et al. Nannochloropsis production metrics in a scalable outdoor photobioreactor for commercial applications. Bioresour Technol. 2012;117:164–171. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2012.04.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rogers JN, Rosenberg JN, Guzman BJ, Oh VH, Mimbela LE, Ghassemi A, et al. A critical analysis of paddlewheel-driven raceway ponds for algal biofuel production at commercial scales. Algal Res. 2014;4:76–88. doi: 10.1016/j.algal.2013.11.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ponnusamy S, Reddy HK, Muppaneni T, Downes CM, Deng S. Life cycle assessment of biodiesel production from algal bio-crude oils extracted under subcritical water conditions. Bioresour Technol. 2014;170:454–461. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2014.07.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Biondi N, Bassi N, Chini Zittelli G, De Faveri D, Giovannini A, Rodolfi L, et al. Nannochloropsis sp. F&M-M24: oil production, effect of mixing on productivity and growth in an industrial wastewater. Environ Prog Sustain. 2013;32(3):846–853. doi: 10.1002/ep.11681. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hulatt CJ, Thomas DN. Energy efficiency of an outdoor microalgal photobioreactor sited at mid-temperate latitude. Bioresour Technol. 2011;102(12):6687–6695. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2011.03.098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhu B, Sun F, Yang M, Lu L, Yang G, Pan K. Large-scale biodiesel production using flue gas from coal-fired power plants with Nannochloropsis microalgal biomass in open raceway ponds. Bioresour Technol. 2014;174:53–59. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2014.09.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lin Q, Lin J. Effects of nitrogen source and concentration on biomass and oil production of a Scenedesmus rubescens like microalga. Bioresour Technol. 2011;102(2):1615–1621. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2010.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Boussiba S, Vonshak A, Cohen Z, Avissar Y, Richmond A. Lipid and biomass production by the halotolerant microalga Nannochloropsis salina. Biomass. 1987;12(1):37–47. doi: 10.1016/0144-4565(87)90006-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Quinn JC, Catton K, Wagner N, Bradley TH. Current large-scale US biofuel potential from microalgae cultivated in photobioreactors. Bioenergy Res. 2012;5(1):49–60. doi: 10.1007/s12155-011-9165-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ranga Rao A, Ravishankar GA, Sarada R. Cultivation of green alga Botryococcus braunii in raceway, circular ponds under outdoor conditions and its growth, hydrocarbon production. Bioresour Technol. 2012;123:528–533. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2012.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.San Pedro A, González-López CV, Acién FG, Molina-Grima E. Outdoor pilot production of Nannochloropsis gaditana: influence of culture parameters and lipid production rates in raceway ponds. Algal Res. 2015;8:205–213. doi: 10.1016/j.algal.2015.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Eustance E, Wray JT, Badvipour S, Sommerfeld MR. The effects of cultivation depth, areal density, and nutrient level on lipid accumulation of Scenedesmus acutus in outdoor raceway ponds. J Appl Phycol. 2016;28(3):1459–1469. doi: 10.1007/s10811-015-0709-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fon-Sing S, Borowitzka MA. Isolation and screening of euryhaline Tetraselmis spp. suitable for large-scale outdoor culture in hypersaline media for biofuels. J Appl Phycol. 2016;28(1):1–14. doi: 10.1007/s10811-015-0560-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ho SH, Chen YD, Chang CY, Lai YY, Chen CY, Kondo A, et al. Feasibility of CO2 mitigation and carbohydrate production by microalga Scenedesmus obliquus CNW-N used for bioethanol fermentation under outdoor conditions: effects of seasonal changes. Biotechnol Biofuels. 2017;10(1):27. doi: 10.1186/s13068-017-0712-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Stepan DJ, Shockey RE, Moe TA, Dorn R. Carbon dioxide sequestering using microalgal systems. Grand Forks: University of North Dakota; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Stephenson AL, Kazamia E, Dennis JS, Howe CJ, Scott SA, Smith AG. Life-cycle assessment of potential algal biodiesel production in the United Kingdom: a comparison of raceways and air-lift tubular bioreactors. Energy Fuel. 2010;24:4062–4077. doi: 10.1021/ef1003123. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gao XP, Yu Y, Wu HW. Life cycle energy and carbon footprints of microalgal biodiesel production in Western Australia: a comparison of byproducts utilization strategies. ACS Sustain Chem Eng. 2013;1(11):1371–1380. doi: 10.1021/sc4002406. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sander K, Murthy GS. Life cycle analysis of algae biodiesel. Int J Life Cycle Assess. 2010;15(7):704–714. doi: 10.1007/s11367-010-0194-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: Figure S1. Outdoor cultivation system of large-scale raceway ponds.

Additional file 2: Table S1. Ingredients of industrial salt.

Additional file 3: Table S2. Elemental analysis of M. dybowskii LB50, Micractinium sp. XJ-2, and P. falcata XJ-176.

Additional file 4: Table S3. LC, BP, and LP of M. dybowskii LB50, Micractinium sp. XJ-2 and P. falcata XJ-176 cultivated indoors.

Additional file 5: Table S4. LC, VBP, ABP, VLP, ALP, and CO2 fixation rate of M. dybowskii LB50, Micractinium sp. XJ-2, and P. falcata XJ-176 grown in 5 m2 ORPs.

Additional file 6: Figure S2. Irradiance, temperature and pH of three microalgae in 5 m2 ORPs.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its additional files.