Abstract

We possess limited understanding of how speciation unfolds in the most species-rich region of the planet—the Amazon basin. Hybrid zones provide valuable information on the evolution of reproductive isolation, but few studies of Amazonian vertebrate hybrid zones have rigorously examined the genome-wide underpinnings of reproductive isolation. We used genome-wide genetic datasets to show that two deeply diverged, but morphologically cryptic sister species of forest understorey birds show little evidence for prezygotic reproductive isolation, but substantial postzygotic isolation. Patterns of heterozygosity and hybrid index revealed that hybrid classes with heavily recombined genomes are rare and closely match simulations with high levels of selection against hybrids. Genomic and geographical clines exhibit a remarkable similarity across loci in cline centres, and have exceptionally narrow cline widths, suggesting that postzygotic isolation is driven by genetic incompatibilities at many loci, rather than a few loci of strong effect. We propose Amazonian understorey forest birds speciate slowly via gradual accumulation of postzygotic genetic incompatibilities, with prezygotic barriers playing a less important role. Our results suggest old, cryptic Amazonian taxa classified as subspecies could have substantial postzygotic isolation deserving species recognition and that species richness is likely to be substantially underestimated in Amazonia.

Keywords: hybrid zones, selection, speciation, genomic clines

1. Introduction

Studies that estimate rates of evolution in traits important for species discrimination and by extension prezygotic reproductive isolation suggest that evolution generally occurs more rapidly at high latitudes than in the tropics. For example, sexually selected traits such as song and plumage coloration show greater rates of evolution in high-latitude birds, thus suggesting that prezygotic isolation evolves faster away from the tropics [1–3]. In addition, faster rates of climatic-niche evolution at high latitudes may accelerate extrinsic postzygotic isolation towards the poles, while reduced divergence in species' climatic niches in the tropics may retard the rate at which reproductive isolation evolves there [4]. These latitudinal patterns for birds suggest that divergent selection pressures between allopatric populations are weaker in the tropics, resulting in lower levels of prezygotic and extrinsic postzygotic isolation there. Intrinsic postzygotic isolation, on the other hand, seems to accumulate slowly in birds. Crosses between avian species have shown that full sterility of F1 hybrids generally requires a minimum of three to four million years of divergence between parental species [5,6], though exceptions are known (e.g. Ficedula flycatchers [7]). Thus the length of time required for intrinsic postzygotic isolation to result in full sterility is broadly much longer than the time scale over which new avian species are formed at high latitudes, suggesting that intrinsic postzygotic isolation may play a limited role in the speciation process there [6]. However, given that prezygotic reproductive isolation mediated by species discrimination traits and extrinsic postzygotic isolation mediated by the environment appear to evolve slowly in the tropics [1–4], it is possible that the process of tropical speciation is protracted, with intrinsic postzygotic isolation playing a more prominent role towards the equator.

Recent research in the Neotropics has provided a wealth of information on the evolution of reproductive isolation, but for the Amazon basin, research has focused mainly on the study of Heliconius butterflies [8]. Almost no studies have investigated the genome-wide underpinnings of reproductive isolation in Neotropical birds [9] or other terrestrial vertebrates, and the only studies to do so for Amazonian birds [10,11] made few conclusions regarding the roles of pre- and postzygotic reproductive isolation. Most research on the evolution of avian reproductive isolation comes from well-studied hybrid zones at high-latitude regions that are generally formed by young species pairs (e.g. [12–15]). Hybrid zone analyses from the Amazon are needed to better understand how vertebrate speciation occurs in areas of high species richness.

Analyses of avian hybrid zones in Amazonia are difficult to implement because most closely related bird species (especially those that inhabit the forest understorey) are separated geographically by river barriers, and few of these are known to come into geographical contact and form hybrid zones [10,16–19]. Likewise within species, phylogeographic analyses have often uncovered five or more genetically distinct lineages (i.e. phylogroups) within widespread understorey avian species in the Amazon basin (e.g. [20,21]). However, few of these genetically distinct lineages are known to come into geographical contact and there is currently limited knowledge of whether they have diverged sufficiently to represent reproductively isolated species. A major exception occurs in the headwaters of the south-eastern section of the Amazon where a series of avian species extend their geographical ranges around or across the headwaters of the Tapajos river and its major tributary, the Teles Pires, to come into geographical contact with closely related congeners [16]. Weir et al. [10] used a genome-wide approach to demonstrate that seven pairs of species or subspecies coming into geographical contact all hybridize in headwater regions of the Teles Pires river, but little is known about the frequency of hybridization or the dynamics of reproductive isolation. This headwater region thus offers an exceptional opportunity to study reproductive isolation in Amazonian birds.

Here we examine geographical contact zones between two pairs of taxa from the headwaters of the Teles Pires: (i) the elegant (Xiphorhynchus elegans) and Spix's (X. spixii) woodcreepers, and (ii) the scale-backed (Willisornis poecilinotus) and Xingu (W. vidua) antbirds. Taxa within each of these pairs were long considered conspecific given their morphological similarity, but were recently split on the basis of genetic divergence (Xiphorhynchus) and relatively minor vocal differences (both species pairs) [22–24]. Both species pairs possess genetically distinct populations on either side of the Tapajos river (though the mouth of the Tapajos does not appear to form a barrier for Willisornis, probably due to palaeo-movement of this part of the river to its current location; see [24]) and lower Teles Pires rivers, but come into geographical contact in headwater regions of the Teles Pires where the width of the river system narrows (figure 1) and eventually ceases to form a dispersal barrier. Despite being morphologically similar in plumage, both species pairs are old (i.e. compared with the age of hybridizing species pairs across a latitudinal gradient [10]), with mitochondrial dating suggesting divergence dates of 2.5 and 4 My for Xiphorhynchus and Willisornis respectively [10]. These old dates of divergence provide an opportunity to study the genetic architecture in pairs of old, cryptic lineages that are prevalent in Amazonia. Willisornis represents one of the oldest pairs of avian species that are known to form a hybrid zone [10]. Despite their old ages, both species pairs are reported to produce non-F1 hybrids, indicating a lack of sterility of F1 hybrids, and the ability for backcrossing to occur [10].

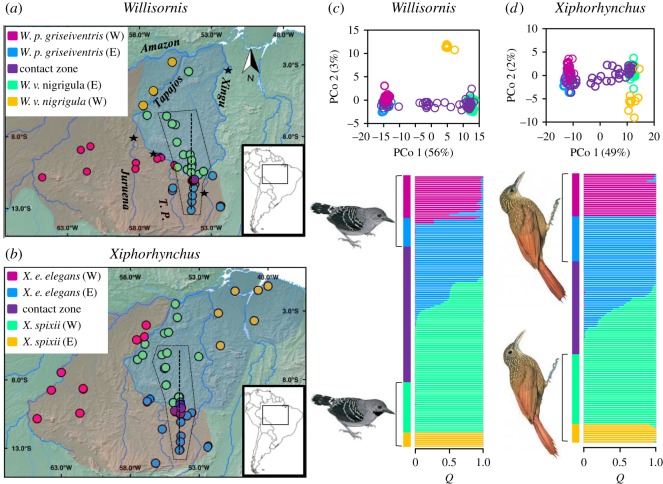

Figure 1.

Geographical sampling and population structure for Willisornis poecilinotus griseiventris and W. vidua nigrigula and Xiphorhynchus elegans elegans and X. spixii in south-central Amazonia. (a,b) Geographical ranges for each taxon (shading in red and blue) and sampling localities for genetically differentiated populations and their contact zones (coloured circles). Contact zone localities included at least one hybrid individual. Stars indicate locations where rivers first narrow to less than 100 m in our study region and give an indication of where headwater regions begin. (c,d) The first two components (and their variance) of a principal coordinate analyses and Bayesian analyses of population structure with each individual represented as a horizontal bar and colours denoting the genomic proportions (Q) derived from each of four populations supported for each species pair. Bird illustrations are reproduced as they are in Handbook of the Birds of the World Alive with the permission of HBW Alive, Lynx Edicions, Barcelona. T. P. indicates the Teles Pires river. (Online version in colour.)

We used genome-wide datasets to characterize the patterns of hybridization and introgression, and to infer potential mechanisms of reproductive isolation. We first compared the distributions of the genome-wide hybrid index and of heterozygosity across contact-zone individuals to distributions simulated under different strengths of pre- and postzygotic selection. Having determined from such analyses that reproductive isolation is strong and is driven primarily by postzygotic isolation, we then used genomic and geographical cline analyses to determine if postzygotic isolation is driven by a small number of loci of major fitness effect, or many loci of minor fitness effect. Portions of the genome closely linked to genes of high fitness effects may be immune to introgression and form sharp transitions between species along contact zones while the remainder of the genome may be free to introgress across species boundaries, producing a pattern of weak transition in the genomic background. We used statistical tests to search for loci with steeper than expected cline widths to try and determine if outlier speciation loci of major effect could be detected. As the number of fitness genes increases, more of the genome should become resistant to introgression and exhibit a sharper transition until, in the extreme case, when reproductive isolation is complete, the entire genome becomes immune to introgression [25,26]. In the latter case, we expect that the accumulation of many fitness affecting loci spread across the genome will result in a high degree of concordance in cline widths and centres across replicate loci [26].

2. Methods

A full description of methods can be found in the electronic supplementary material.

(a). Genotyping by sequencing and SNP generation

We genetically analysed 144 individuals of Willisornis and 128 of Xiphorhynchus sampled in detail along a 550 km north-to-south transect between the headwaters of the Teles Pires and Xingu rivers and more broadly across south central Amazonia (figure 1a; electronic supplementary material, figure S1, database S1 and S2). This included 70 individuals of Willisornis and 43 of Xiphorhynchus obtained from contact zone populations where either both parentals and/or hybrids occurred syntopically.

A genome-wide sample of SNPs was obtained using genotyping-by-sequencing (GBS) [27]. Two datasets were generated. The first dataset with a minimum depth of coverage of 3× was extracted and used for the Bayesian genomic clines analyses in bgc [28] in which genotype uncertainty is explicitly incorporated into the modelling framework. The second dataset had a minimum 10× coverage and was used for all other analyses. SNPs in both datasets were further filtered to have a single SNP per GBS locus, a minor allele frequency greater than 0.05, a maximum SNP heterozygosity of 0.75 (to exclude paralogues), loci coverage (proportion of individuals with genotyped data at a given locus) of at least 80%, and an individual coverage (proportion of loci with genotyped data for a given individual) of at least 75%. This rigorous filtering retained 901 SNPs for Willisornis and 501 SNPs for Xiphorhynchus.

(b). Population structure and differentiation

We used Bayesian analysis of population structure (Structure v. 2.3.4 [29,30]) and principal coordinate analysis (PCoA; PAST v. 3.10 [31]) of all SNPs to identify parental and genetically admixed populations. We quantified genome-wide differentiation between parental populations for both species pairs using the interspecific differentiation index (D) [32]. This index measures the mean difference in allele frequencies between parental populations for each SNP.

(c). Analysis of intrinsic postzygotic isolation

We used fully fixed SNPs (D = 1) between parental populations (147 SNPs for Willisornis, 45 for Xiphorhynchus) to calculate the hybrid index HI (analogous to the admixture coefficient, Q, from Structure, with a value of 0 corresponding to pure individuals from W. poecilinotus and X. elegans, and 1 to W. vidua and X. spixii), and observed heterozygosity, Ho, for each individual in the contact zone. For loci fixed between parentals, Ho is the proportion of loci in an individual's genome that are heterozygous for the parental alleles (0 = all homozygous genotypes, 1 = all heterozygous genotypes) [33]. Ho is 0 for individuals from parental populations, 1 for F1 hybrids, while latter generation hybrids lie between 0 and 1. HI and Ho were visualized in triangle plots (figure 2a). Individuals along the diagonals of these plots (representing the descendants of F1 hybrids that have backcrossed once or multiple times with one of the parentals) have the least recombination, while individuals in the middle (C category, representing F2, F3 and other classes of later generation hybrid individuals) have the most.

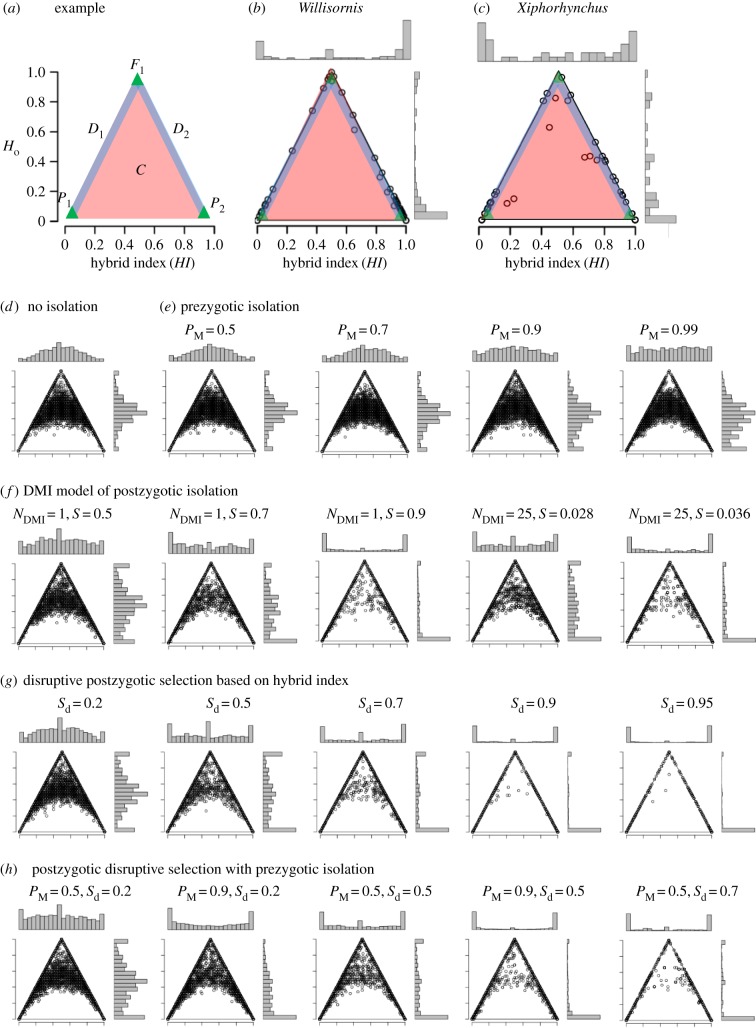

Figure 2.

Triangle plot analyses of genome-wide hybrid index (HI) and observed heterozygosity (Ho). (a) Illustrative triangle plot showing the position of different classes of hybrids (D1 and D2 are hybrids lying along the diagonals which result from successive backcrossing of F1 with one of the parental species; C represent F2 and other classes of later generation hybrids which lie off the diagonals and have the highest levels of recombination) and parentals (P1 and P2). (b,c) Triangle plots for all contact zone individuals in (b) Willisornis (HI = 0 for W. poecilinotus and 1 for W. vidua) and (c) Xiphorhynchus (HI=0 for X. elegans and 1 for X. spixii). Histograms are shown for the distribution of HI and Ho. (d–h) Simulated triangle plots with (d) no isolation or (e–h) varying levels of prezygotic and postzygotic isolation. Simulated data pooled from 20 replicate simulations each of 200 individuals and lasting 1000 generations, with each generation allowing migration from parental source populations, random (with no prezygotic isolation) or nonrandom (with prezygotic isolation) mating, and selection against hybrid offspring. PM is the probability that individuals will fail to mate when they differ in hybrid index by a value of 1. Sd is the maximum level of selection (against individuals with a hybrid index of 0.5) under the disruptive postzygotic selection model and S is the rate of postzygotic selection against each Dobzhansky–Muller incompatibility (DMI). NDMI is the number of DMI loci pairs used (either 1 or 25). (Online version in colour.)

Simulations of genetic markers in individuals at hybrid zones were performed under three different scenarios of reproductive isolation. These were used to visualize the expected distribution of Ho and HI with and without pre- and postzygotic isolation in the hybrid zone centre. First, we modelled prezygotic isolation whereby the probability of mating (PM) for a pair of random individuals is proportional to their similarity in HI values. The probability of mating decreases linearly with the absolute difference in HI from a maximum value of 1 when HI values are identical to a minimum value of PM when the absolute difference in HI values is 1 (i.e. parental individuals of each species). Next, we modelled selection (S) against either 1 or 25 Dobzhansky–Muller incompatibilities (DMIs), each involving two loci. Finally, we modelled disruptive postzygotic selection based on HI, with the strongest selection acting when HI = 0.5 (parameter Sd) and no selection when HI = 0 or 1. Selection rates increased linearly between HI = 0 and HI = 0.5, and declined linearly between HI = 0.5 and HI = 1. All scenarios allowed ongoing migration from parental populations, and were run for 1000 generations, though the resulting patterns were similar whether run for 10, 100 or 1000 generations (electronic supplementary material, figure S5).

(d). Genomic and geographical cline analysis

We performed analysis of geographical and genomic clines to determine if loci showed variability in cline centre (α) and width (β) as expected for species pairs with genomes that are semipermeable to gene flow. A greater steepness (positive β) than expected may indicate loci with reduced levels of introgression, while narrow clines with little variance in α and β are indicative of late stages of the speciation process when genomes are immune to introgression due to the accumulation of large number of genes conferring negative fitness effects on hybrids. Geographical cline shape of a particular locus was considered significantly different if the 95% confidence intervals did not overlap with the 95% confidence intervals obtained for a geographical cline estimated using the genome-wide admixture (Q). Analyses were performed only for loci with a minimum threshold of differentiation between parental populations of D > 0.6.

Kriging of the admixture coefficient Q from Structure across the geographical landscape (electronic supplementary material, figure S3) indicated that geographical clines were oriented along an almost perfectly north to south transect. We therefore used latitude position to calculate placement along transects for geographical clines for the individuals shown in the dotted polygons in figure 1. For each species pair, the transect started at the northernmost sampling location (latitude −6.6 Willisornis; −6.1 Xiphorhynchus) within the dotted polygons (figure 1) and ended at the southernmost (latitude −13.1 for both).

(e). Tests for introgression outside of hybrid zones

If introgression has occurred beyond the hybrid zone region into adjacent ‘parental’ populations, we would expect that these parental populations will have a greater proportion of loci with small and a lower proportion of loci with high D values compared with populations far from the contact zone. We tested this using a chi-squared test to compare both the number of weakly differentiated (D ≤ 0.2) and strongly differentiated (D ≥ 0.8) loci in adjacent versus geographically distant pairs of populations.

(f). Tests for assortative mating

Following methods in [12], we tested for assortative mating in Willisornis poecilinotus/vidua (mated pairs both respond aggressively to song playback allowing us to collect genetic information for paired individuals) but not in Xiphorhynchus spixii/elegans (we rarely collected both members of a pair given paired individuals rarely responded together to playback) using a Pearson rank order correlation (r) to compare genetic hybrid indices (i.e. the admixture proportion Q from Structure) of 14 females and their mates. We calculated the significance of this correlation by randomly assigning each female a male from their own local population within the contact zone (this corrects for genetic structure within the contact zone) and calculating the overall genetic correlation between paired individuals. The randomization included 74 individuals (the 14 pairs and 46 additional individuals which lacked genetic data for the mate). We repeated this randomization 100 000 times, generating a distribution of within-pair correlations expected under random mating.

3. Results

PCo 2 and Bayesian analyses of population structure uncovered two genetically distinctive groups within each of the four taxa analysed here (called western and eastern populations), and these appear to be separated by the Tapajos (W. vidua nigrigula), Teles Pires (W. poecilinotus griseiventris, with hybrid individuals in populations immediately adjacent to the river), Juruena (X. elegans elegans) and Xingu (X. spixii) rivers (figure 1). Of these, PCoA indicate that the two populations of W. vidua nigrigula are the most diverged, while differentiation between the other intraspecific populations was minor. Only the populations within each species that come into contact with their sister species (coloured blue and green, figure 1) in the headwater regions between the Xingu and Teles Pires rivers were used in subsequent hybrid zone analyses. PCo 1, the analyses of population structure (figure 1c,d), and the distribution of loci D values (electronic supplementary material, figure S2) showed clear differentiation between headwater populations of each species pair. Many individuals from the contact zone were intermediate in their positioning along PCo 1 and had varying degrees of genetic admixture (figure 1), consistent with the presence of a hybrid zone where these species pairs come into contact. Contact zone populations also possessed many individuals with a genetic composition that matched parental populations of either species pair (figure 1).

Triangle plots of contact zone individuals revealed a large number of parental-like individuals, a small number of F1-like hybrids, a substantial number of individuals along the diagonals of the triangle plot (D1 and D2), and no (Willisornis) or few (Xiphorhynchus) hybrids in the middle of the sample space (C) where recombination is greatest (figure 2b,c). In contrast, simulations with no reproductive isolation (figure 2d) have unimodal distributions of HI and Ho (with modes each near 0.5). Most individuals represented C category hybrids and there were few parental or F1 hybrids. These distributions became flat under high levels of prezygotic isolation, but never bimodal even with assortative mating as high as PM = 0.99 (figure 2e). Here our premating isolation model assumes mate choice based on similarity in hybrid index. Alternatively, mate choice could be based on as little as a single mate preference gene. In the latter case, we expect that recombination will erode correlations between phenotype genes and mate preference genes rapidly, resulting in even faster collapse of species differences than detected under our model here using hybrid index. The key exception to this is when mate preference genes and the targets of those genes are under strong linkage disequilibrium, for example when both occur along inversions.

Both the DMI and disruptive selection models of post-zygotic isolation (figure 2f–h) produced strongly bivariate distributions of hybrid index with few hybrids when selection rates were high. However, whether a given level of selection was targeted at one or 25 pairs of DMI had little impact on the resulting distributions.

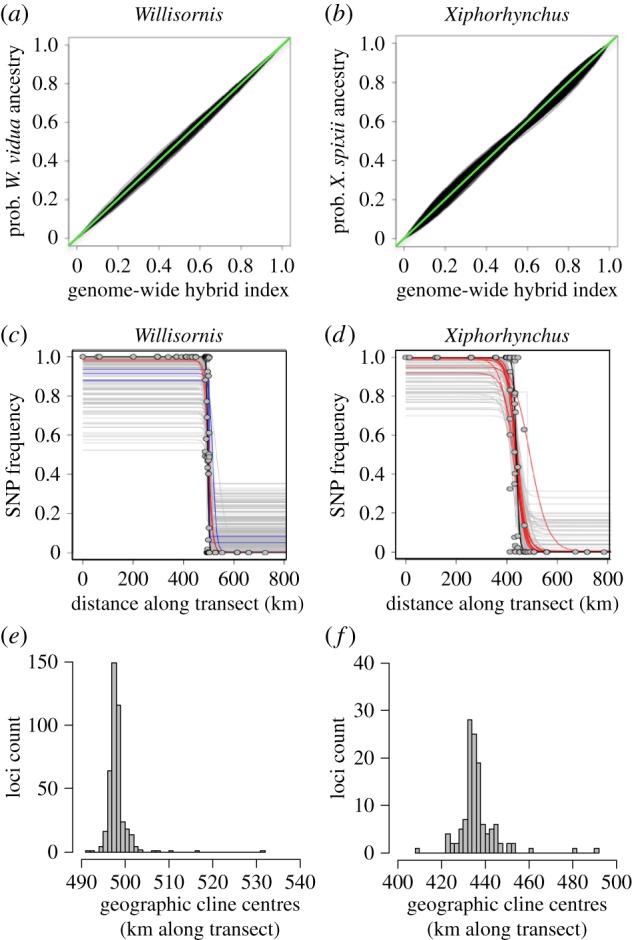

Tests for introgression using Bayesian genomic clines detected no loci with significant departures from the genomic background expectations in α (centre) and β (width) (figure 3a,b). Likewise, geographical clines showed no loci with narrower than expected widths, though several loci for both species pairs showed broader than expected widths and several had cline centres slightly shifted (in all cases to the north) (figure 3c,d; electronic supplementary material, table S1). The centre of the genome-wide Q cline (calculated from all loci) in Willisornis was calculated at 496.5 km (95% confidence interval = 495.5 to 497.7 km) with clines of individual loci with D > 0.7 ranged from 491 to 531 km. In Xiphorhynchus the centre of the Q cline occurred at 438.01 km (95% confidence interval = 435.7 to 440.6 km) (figure 3) with individual loci ranging from 408 to 491 km. The width of the Q cline in Willisornis was estimated at 10.1 km (95% confidence interval = 8.1 to 13.3 km) while clines of individual loci with D > 0.7 varied from 0.1 to 83.4 km. In Xiphorhynchus the width of the Q cline was 24.6 km (95% confidence interval = 20.3 to 30.3 km) with individual loci ranging from 0.4 to 145.3 km.

Figure 3.

Genomic and geographical cline analyses. Genomic clines for the (a) Willisornis (901 loci) and (b) Xiphorhynchus (501 loci) hybrid zones. The green line is the genome-wide expectation, individual loci are shown in black, and none showed significant deviations in cline centre or slope. Geographical clines for loci with D > 0.7 for (c) Willisornis (418 loci) and (d) Xiphorhynchus (123 loci). Lines represent SNP cline fits for loci in which cline centre (blue), width (red) or neither (grey) deviated significantly from the genome-wide admixture cline Q (thick black line). In all cases, width outliers had significantly greater widths than the genome-wide admixture cline. Grey circles represent admixture proportions (Q value) from the Bayesian analysis of population structure (figure 1) for each individual. Histograms of geographical cline centres across loci are shown in (e) and (f). (Online version in colour.)

For both Willisornis and Xiphorhynchus the proportion of loci that were strongly differentiated (D > 0.8) was not significantly lower in populations near the contact zone compared with populations farther from the contact zone (statistical results in electronic supplementary material, table S2). Likewise, the proportion of loci that were weakly differentiated (D < 0.2) was not higher in near versus far populations (electronic supplementary material, table S2). These results held true even when correcting for low sample size of one of our populations of Xiphorhynchus spixii.

Finally, though sample size was low (14 mated pairs with genetic data from the hybrid zone), no significant correlation was found between mated pairs of Willisornis in their allelic composition across SNPs (r = 0.54; p = 0.143), indicating a failure to reject the hypothesis of random mating. One pair was mixed between genetically pure individuals of each parental, four pairs between a genetically pure parental and an F1-like individual, three pairs between parental and later-generation backcrossed individuals, and individuals in six pairs were not mixed between species (three of which came from local populations with only pure individuals of one of the two species detected).

4. Discussion

The process of speciation is poorly characterized in one of the most species-rich regions of the planet—the Amazon basin. Previous studies on birds have demonstrated slow evolutionary rates near the equator in traits important to speciation like song, plumage coloration and climatic niche [1,2,4]. These tropical rates suggest that prezygotic isolation (mediated by song and plumage) and extrinsic postzygotic isolation (mediated by the environment) evolve slowly in the tropics and may play a less important role in tropical speciation than the gradual accumulation of intrinsic postzygotic isolation. Here we analysed two cryptic species pairs that diverged approximately 2.5 to 4.2 Ma. We present evidence from triangle plots and genomic and geographical cline analyses that reproductive isolation is nearly complete and is driven largely by postzygotic isolation in which a large number of loci render the genomic background immune to introgression.

We first used triangle plot analyses to infer that reproductive isolation is strong and is not driven solely by prezygotic isolation, but rather is largely driven by postzygotic isolation (figure 2). Strong reproductive isolation is inferred for Willisornis and Xiphorhynchus from their bimodal distribution of hybrid indices (figure 2b,c). Simulations without reproductive isolation instead collapsed into unimodal distributions after a few generations (figure 2d; electronic supplementary material, figure S5). Simulations of prezygotic isolation also failed to produce bimodal distributions, even with species discrimination probabilities as high as 0.99 (figure 2e). Rather, species discrimination must be near complete (i.e. greater than 0.99) in order to produce bivariate distributions and a lack of species collapse in contact zone populations, consistent with previous suggestions [6,34]. We uncovered no indication that either Willisornis or Xiphorhynchus experience near complete species discrimination. For example, populations from hybrid zone centres failed to reject random mating (Willisornis; not assessed for Xiphorhynchus) with respect to male and female genetic background, though sample size was low and the test may thus lack strong statistical power. Nevertheless, our results clearly demonstrate that assortative mating, if present at all, is certainly not strong enough (i.e. PM > 0.99) to maintain a bivariate distribution of hybrid indices in hybrid zone populations. Furthermore, while both species pairs differ in minor aspects of their song (degree of raspiness in Willisornis and song pace in Xiphorhynchus) and calls (shape of contact calls in Willisornis, possible pace differences in Xiphorhynchus), we frequently used interspecific playback of vocalizations to trap birds in nets, suggesting a lack of strong vocal discrimination in both pairs, though formal tests are still required.

In contrast to prezygotic isolation, both of our models of postzygotic isolation (DMI and disruptive selection on hybrid index) produced strongly bivariate distributions of hybrid index at high levels of selection that closely matched the bivariate distributions observed for Willisornis and Xiphorhynchus (figure 2f,g). Adding prezygotic isolation to postzygotic isolation further reduced the number of hybrids in simulations, indicating that the two forms of selection can work together to prevent species collapse, but that only postzygotic and not prezygotic isolation can function alone to this end. We conclude that the strong reproductive isolation evident in triangle plot patterns produced for Willisornis and Xiphorhynchus is largely driven by postzygotic isolation with probably only a modest contribution from prezygotic isolation.

Determining whether postzygotic isolation is driven by a small number of genes of large fitness effect or by many genes spread across the genome is important to understanding the processes that drive speciation. If postzygotic isolation were driven by a single or small number of genes of major fitness effect, then we should expect these genes to be associated with exceptionally narrow cline widths compared to the genomic background expectation, though even neutral dynamics can sometimes generate narrow width outliers [26]. Studies of both avian and non-avian hybrid zones from outside of the Amazon basin (and mostly at high latitudes) have often uncovered outlier loci with narrow cline widths (e.g. 50 outliers of 1425 loci for Poecile chickadees [35]; 25 of 84 Passer sparrows [36]; see also Lycaeides butterflies [37]; Mus mice [38]). In contrast, none of the genetic markers in this study had narrower cline widths than expected for either genomic or geographical cline analyses, though we may simply have failed to sample markers in close linkage disequilibrium with large-effect speciation genes, and whole genome sequencing might yet uncover such genes.

During intermediate stages of the speciation process genomes may be semipermeable to gene flow at neutral loci which are not closely linked to speciation genes and for loci under positive selection to introgress. This semipermeable nature allows for considerable variability across neutral loci in cline centres and widths while positively selected alleles may introgress deeply and loci with major deleterious fitness effects in hybrids may be associated with exceptionally narrow cline widths. As the number of genes conferring a deleterious fitness effect in hybrids increases, the genome becomes progressively less permeable culminating in the late stages of speciation when the entire genome may become immune to introgression (so called ‘genomic speciation’ [26]), resulting in genome-wide concordance in cline widths and cline centres across loci regardless of whether or not they confer a fitness effect [25,26]. In Willisornis and Xiphorhynchus cline centres and widths exhibited remarkable concordance compared with most other avian studies (e.g. [9,13,32,35,39,40]), with no outlier loci detected for genomic clines and few outliers in geographical clines (figure 3; electronic supplementary material, table S1). Further, our geographical clines were exceptionally narrow for birds (compared with table 15.1 in [6]), with the genome-wide cline width of just 10 km in Willisornis and 25 km in Xiphorhynchus. Assuming these hybrid zones formed at the start of the Holocene 11 700 ybp (i.e. at the end of the last glacial cycle when wet forest expanded back into headwater regions where the current hybrid zones occur; see discussion in [10]), a generation time of 2 years and a postnatal dispersal distance of at least 1 km (Willis [41] and Terborgh et al. [42] report individual territories to be approx. 320 m in diameter in Willisornis and 440 m for woodcreepers, which suggest that a postnatal distance of at least 1 km is reasonable), hybrid zone widths at neutral loci (i.e. those not under close linkage disequilibrium to genetic incompatibilities) should be at least 192 km on average (see formula in [43]). Zone widths would increase to 384 and 960 km with larger postnatal dispersal distances of 2 or 5 km respectively. None of our loci had widths as broad as 192 km (including the small number of outlier loci with wider than expected cline widths), suggesting strong selection across the genome is maintaining narrow hybrid zone widths. The exceptionally narrow widths of our hybrid zones together with the highly concordant cline centres thus strongly suggest that we are dealing with a late stage of speciation in which many genetic incompatibilities spread across the genome have rendered genes of these species pairs immune to introgression even at most neutral loci. A possible objection to this conclusion is that all of the differentiated markers (with D > 0.7) in our analyses might come from the Z chromosome or a few other regions of low recombination and high linkage disequilibrium (e.g. inversions), and thus do not represent genome-wide patterns. However, our genetic markers for both species pairs map to a large diversity of chromosomes indicating this is not the case (see electronic supplementary material, table S3). Moreover, we find similar proportions of loci that were either strongly (D > 0.8) or weakly (D < 0.2) differentiated between populations near the contact zone versus populations far from contact zone regions (electronic supplementary material, table S4). These results suggest minimal introgression has occurred outside of the immediate vicinity of the contact zones and that hybrid zones in these two pairs of species are not commonly acting as selectively permeable membranes despite the fact that many of our genetic markers are likely to be non-coding and neutral.

Prezygotic and extrinsic postzygotic barriers have often been considered of greater importance to speciation in birds and other groups than intrinsic postzygotic isolation because of the belief that barriers preventing mating or adaptations to environmental conditions typically evolve fastest, while hybrid sterility evolves too slowly to account for speciation (birds [5,44]; darter fish [45,46]; cichlid fish [47]; Heliconius butterflies [48]; Drosophila [49]). We are aware of only one other avian example (Ficedula flycatchers) in which genetic incompatibilities are believed to play the primary role in driving speciation [7]. Likewise, all studied Helicionius butterfly examples from the Neotropics appear to involve strong prezygotic isolation and/or extrinsic postzygotic isolation (hybrids not recognized as unpalatable by birds), though intrinsic postzygotic barriers are known to also contribute in select examples [50]. In contrast, comparative analyses have shown great variation in the contribution of prezygotic and intrinsic postzygotic isolation in driving speciation across Drosophila species [51], with near-complete reproductive isolation driven almost solely by either pre- or postzygotic isolation or by a combination of the two in different suites of species. Our results here for Willisornis and Xiphorhynchus suggest that intrinsic barriers may play a key role in Amazonian avian speciation involving morphologically cryptic taxa. These taxa have been diverging over long time periods on opposite sides of wide Amazonian rivers which limit gene flow. Despite similar environments on opposing river banks, and thus presumed low levels of divergent selection that might lead to rapid prezygotic and extrinsic postzygotic isolation, the long time spans involved have allowed for genetic incompatibilities to accumulate at many loci across the genome, leading to speciation.

In conclusion, our results suggest that reproductive isolation in these Amazonian understorey forest birds evolves largely through postzygotic reproductive barriers and may be driven by the accumulation of genetic incompatibilities over long time periods in the inferred absence of strong divergent selection. Prezygotic or extrinsic postzygotic barriers probably have less effect on these speciation events than intrinsic postzygotic barriers. Thus, the limited plumage and song divergence between many Amazonian understorey forest bird lineages may not necessarily indicate a lack of reproductive isolation, but instead may indicate that prezygotic reproductive barriers play a less important role in the speciation process in Amazonia. Here we only analyse two hybrid zones chosen from a series of hybrid zones in the headwaters of the Teles Pires river in the Amazon rainforest [10], based on the availability of large numbers of collected samples. If our results for these two hybrid zones are reflective of other morphologically and vocally cryptic avian lineages in Amazonia (which seems probable), then it is likely that many of the deeply diverged genetic lineages known to be present within Amazonian underforest species will deserve species status, and that the number of biological species in Amazonia may be substantially underestimated [10,21,52]. The hybrid zones analysed here occurred between relatively old (Xiphorhynchus, 2.5 Ma) to very old (Willisornis, 4 Ma), morphologically similar lineages, which until recently had been considered conspecific. Further studies will be needed to determine if sufficient intrinsic postzygotic isolation can accumulate for pairs of morphologically cryptic Amazonian avian taxa that diverged around 1 or 2 Ma, the time scale over which reproductive isolation generally evolves in high-latitude passerines [53].

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank the many landowners who allowed sampling on their properties and the Brazilian Government for issuing research permits, Maya Faccio and Alfredo Barrera-Guzmán for assisting with field collection, Trevor Price for discussions on premating isolation, and Stephen Wright and Santiago J. Sánchez-Pacheco for constructive comments on the manuscript.

Ethics

Fieldwork to capture and obtain genetic samples followed procedures in accordance with the Animal Ethics Protocols of the University of Toronto (20009364 and 20010519) and Goeldi Museum (CEUA/MPEG 2/2017). Collecting permits in Brazil were issued by the Brazilian ministries of the Environment (4253-1, 40173-1 and 6581-1) and Science and Technology (00813/2011-7 and 01300.002155/2013-91).

Data accessibility

Illumina short read data have been deposited in the National Center for Biotechnology Information Sequence Read Archive under BioProjects PRJNA433557 and PRJNA433538 (see electronic supplementary material, database S1 and S2).

Authors' contributions

All authors designed the study and collected samples, P.P.-S. analysed the data, J.T.W. performed simulations, P.P.-S. and J.T.W. wrote and A.A. edited the manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Funding

Computations were performed on the General Purpose and Sandybridge supercomputers at the SciNet HPC Consortium, which is funded by the Canadian Foundation for Innovation, the Government of Ontario, and the University of Toronto. Research funding was provided by Colciencias Francisco Jose de Caldas grant no. 20110582 (P.P.-S); the Mitacs Globalink Research Award 497400 (P.P.-S. and J.T.W.); the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC) Discovery Grant (RGPIN-2016-06538), NSERC Discovery Accelerator grant no. 492890, and the University of Toronto Scarborough VPR-Research Competitiveness Fund (J.T.W); and CNPq (‘INCT em Biodiversidade e Uso da Terra da Amazônia’ #574008/2008-0; #471342/ 2011-4; #310880/2012-2; and #306843/2016-1) and the Amazônia Paraense Foundation—FAPESPA (grant no. ICAAF 023/2011) (A.A.).

References

- 1.Martin PR, Montgomerie R, Lougheed SC. 2010. Rapid sympatry explains greater colour pattern divergence in high latitude birds. Evolution 64, 336–347. ( 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2009.00831.x.) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weir JT, Wheatcroft D. 2011. A latitudinal gradient in rates of evolution of avian syllable diversity and song length. Proc. R. Soc. B 278, 1713–1720. ( 10.1098/rspb.2010.2037) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weir JT, Wheatcroft DJ, Price TD. 2012. The role of ecological constrain in driving the evolution of avian song frequency across a latitudinal gradient: evolution of birdsong. Evolution 66, 2773–2783. ( 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2012.01635.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lawson AM, Weir JT. 2014. Latitudinal gradients in climatic-niche evolution accelerate trait evolution at high latitudes. Ecol. Lett. 17, 1427–1436. ( 10.1111/ele.12346) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Price TD, Bouvier MM. 2002. The evolution of F1 postzygotic incompatibilities in birds. Evolution 56, 2083–2089. ( 10.1111/j.0014-3820.2002.tb00133.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Price T. 2008. Speciation in birds. Greenwood Village, CO: Roberts and Co. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wiley C, Qvarnström A, Andersson G, Borge T, Saetre G-P. 2009. Postzygotic isolation over multiple generations of hybrid descendents in a natural hybrid zone: how well do single-generation estimates reflect reproductive isolation? Evolution 63, 1731–1739. ( 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2009.00674.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.The Heliconius Genome Consortium. 2012. Butterfly genome reveals promiscuous exchange of mimicry adaptations among species. Nature 487, 94–98. ( 10.1038/nature11041) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Parchman TL, Gompert Z, Braun MJ, Brumfield RT, McDonald DB, Uy JAC, Jarvis ED, Schlinger BA, Buerkle CA. 2013. The genomic consequences of adaptive divergence and reproductive isolation between species of manakins. Mol. Ecol. 22, 3304–3317. ( 10.1111/mec.12201) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weir JT, Faccio MS, Pulido-Santacruz P, Barrera-Guzmán AO, Aleixo A. 2015. Hybridization in headwater regions, and the role of rivers as drivers of speciation in Amazonian birds. Evolution 69, 1823–1834. ( 10.1111/evo.12696) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barrera-Guzmán AO, Aleixo A, Shawkey MD, Weir JT. 2018. Hybrid speciation leads to novel male secondary sexual ornamentation of an Amazonian bird. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 115, E218–E225. ( 10.1073/pnas.1717319115) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brelsford A, Irwin DE. 2009. Incipient speciation despite little assortative mating: the yellow-rumpled warbler hybrid zone. Evolution 63, 3050–3060. ( 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2009.00777.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grossen C, Seneviratne SS, Croll D, Irwin DE. 2016. Strong reproductive isolation and narrow genomic tracts of differentiation among three woodpecker species in secondary contact. Mol. Ecol. 25, 4247–4266. ( 10.1111/mec.13751) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Seneviratne SS, Davidson P, Martin K, Irwin DE. 2016. Low levels of hybridization across two contact zones among three species of woodpeckers (Sphyrapicus sapsuckers). J. Avian Biol. 47, 887–898. ( 10.1111/jav.00946) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Toews DPL, Brelsford A, Grossen C, Milá B, Irwin DE. 2016. Genomic variation across the yellow-rumped warbler species complex. The Auk 133, 698–717. ( 10.1642/AUK-16-61.1) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Haffer J. 1997. Contact zones between birds of southern Amazonia. Ornith. Monogr. 48, 281–305. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Haffer J. 2008. Hypotheses to explain the origin of species in Amazonia. Braz. J. Biol. 68, 917–947. ( 10.1590/S1519-69842008000500003) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Naka LN, Bechtoldt CL, Henriques LMP, Brumfield RT. 2012. The role of physical barriers in the location of avian suture zones in the Guiana Shield, northern Amazonia. Am. Nat. 179, E115–E132. ( 10.1086/664627) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harvey MG, et al. 2014. The avian biogeography of an Amazonian headwater: the Upper Ucayali River, Peru. Wilson J. Ornithol. 126, 179–191. ( 10.1676/13-135.1) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fernandes AM, Gonzalez J, Wink M, Aleixo A. 2013. Multilocus phylogeography of the Wedge-billed Woodcreeper Glyphorynchus spirurus (Aves, Furnariidae) in lowland Amazonia: widespread cryptic diversity and paraphyly reveal a complex diversification pattern. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 66, 270–282. ( 10.1016/j.ympev.2012.09.033) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thom G, Aleixo A. 2015. Cryptic speciation in the white-shouldered antshrike (Thamnophilus aethiops, Aves—Thamnophilidae): the tale of a transcontinental radiation across rivers in lowland Amazonia and the northeastern Atlantic Forest. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 82, 95–110. ( 10.1016/j.ympev.2014.09.023) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Aleixo A. 2002. Molecular systematics and the role of the ‘várzea’-‘terra-firme’ ecotone in the diversification of Xiphorhynchus woodcreepers (Aves: Dendrocolaptidae). The Auk 119, 621–640. ( 10.1642/0004-8038) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Aleixo A. 2004. Historical diversification of a terra-firme forest bird superspecies: a phylogeographic perspective on the role of different hypotheses of Amazonian diversification. Evolution 58, 1303–1317. ( 10.1111/j.0014-3820.2004.tb01709.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Isler ML, Whitney BM. 2011. Species limits in antbirds (Thamnophilidae): the scale-backed antbird (Willisornis poecilinotus) complex. Wilson J. Ornithol. 123, 1–14. ( 10.1676/10-082.1) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Barton N, Bengtsson BO. 1986. The barrier to genetic exchange between hybridising populations. Heredity 57, 357–376. ( 10.1038/hdy.1986.135) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gompert Z, Mandeville EG, Buerkle CA. 2017. Analysis of population genomic data from hybrid zones. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 48, 207–229. ( 10.1146/annurev-ecolsys-110316-022652) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Elshire RJ, Glaubitz JC, Sun Q, Poland JA, Kawamoto K, Buckler ES, Mitchell SE. 2011. A Robust, simple genotyping-by-sequencing (GBS) approach for high diversity species. PLoS ONE 6, e19379 ( 10.1371/journal.pone.0019379) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gompert Z, Buerkle CA. 2012. bgc? Software for Bayesian estimation of genomic clines. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 12, 1168–1176. ( 10.1111/1755-0998.12009.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pritchard JK, Stephens M, Donnelly P. 2000. Inference of population structure using multilocus genotype data. Genetics 155, 945–959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Falush D, Stephens M, Pritchard JK. 2003. Inference of population structure using multilocus genotype data: linked loci and correlated allele frequencies. Genetics 164, 1567–1587. ( 10.1111/j.1471-8286.2007.01758.x) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hammer O, Harper DAT, Ryan PD. 2001. Past: paleontological statistics software package for education and data analysis. Palaeontol. Electron. 4, 9. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Larson EL, Andrés JA, Bogdanowicz SM, Harrison RG. 2013. Differential introgression in a mosaic hybrid zone reveals candidate barrier genes. Evolution 67, 3653–3661. ( 10.1111/evo.12205) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gompert Z, Buerkle CA. 2009. A powerful regression-based method for admixture mapping of isolation across the genome of hybrids. Mol. Ecol. 18, 1207–1224. ( 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2009.04098.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hudson EJ, Price TD. 2014. Pervasive reinforcement and the role of sexual selection in biological speciation. J. Hered. 105, 821–833. ( 10.1093/jhered/esu041) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Taylor SA, Curry RL, White TA, Ferretti V, Lovette I. 2014. Spatiotemporally consistent genomic signatures of reproductive isolation in a moving hybrid zone. Evolution 68, 3066–3081. ( 10.1111/evo.12510) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Trier CN, Hermansen JS, Sætre G-P, Bailey RI. 2014. Evidence for mito-nuclear and sex-linked reproductive barriers between the hybrid Italian sparrow and its parent species. PLoS Genet. 10, e1004075 ( 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004075) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gompert Z, Lucas LK, Nice CC, Fordyce JA, Forister ML, Buerkle CA. 2012. Genomic regions with a history of divergent selection affect fitness of hybrids between two butterfly species. Evolution 66, 2167–2181. ( 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2012.01587.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Janousek V, Munclinger P, Wang L, Teeter KC, Tucker PK. 2015. Functional organization of the genome may shape the species boundary in the house mouse. Mol. Biol. Evol. 32, 1208–1220. ( 10.1093/molbev/msv011) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.da Barbiano LA, Gompert Z, Aspbury AS, Gabor CR, Nice CC. 2013. Population genomics reveals a possible history of backcrossing and recombination in the gynogenetic fish Poecilia formosa. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 110, 13 797–13 802. ( 10.1073/pnas.1303730110) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nosil P, Parchman TL, Feder JL, Gompert Z. 2012. Do highly divergent loci reside in genomic regions affecting reproductive isolation? A test using next-generation sequence data in Timema stick insects. BMC Evol. Biol. 12, 164 ( 10.1186/1471-2148-12-164) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Willis EO. 1982. The behavior of Scale-backed Antbirds. Wilson Bull. 94, 447–462. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Terborgh J, Robinson SK, Parker TA, Munn CA, Pierpont N. 1990. Structure and organization of an Amazonian forest bird community. Ecol. Monogr. 60, 213–238. ( 10.2307/1943045) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Barton N, Gale K. 1993. Genetic analysis of hybrid zones. In Hybrid zones and the evolutionary process (ed. Harrison RG.), pp. 13–45. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lijtmaer DA, Mahler B, Tubaro PL. 2003. Hybridization and postzygotic isolation patterns in pigeons and doves. Evolution 57, 1411–1418. ( 10.1111/j.0014-3820.2003.tb00348.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mendelson TC, Imhoff VE, Venditti JJ. 2007. The Accumulation of reproductive barriers during speciation: postmating barriers in two behaviorally isolated species of darters (Percidae: Etheostoma). Evolution 61, 2596–2606. ( 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2007.00220.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mendelson TC. 2003. Sexual isolation evolves faster than hybrid inviability in a diverse and sexually dimorphic genus of fish (Percidae: Etheostoma). Evolution 57, 317–327. ( 10.1111/j.0014-3820.2003.tb00266.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Stelkens RB, Young KA, Seehausen O. 2010. The accumulation of reproductive incompatibilities in African Cichlid fish. Evolution 64, 617–633. ( 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2009.00849.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Merot C, Salazar C, Merrill RM, Jiggins CD, Joron M. 2017. What shapes the continuum of reproductive isolation? Lessons from Heliconius butterflies. Proc. R. Soc. B 283, 20170335 ( 10.1098/rspb.2017.0335) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Coyne JA, Orr HA. 1989. Patterns of speciation in Drosophila. Evolution 43, 362–381. ( 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1989.tb04233.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Muñoz AG, Salazar C, Castaño J, Jiggins CD, Linares M. 2010. Multiple sources of reproductive isolation in a bimodal butterfly hybrid zone: reproductive isolation in bimodal hybrid zone. J. Evol. Biol. 23, 1312–1320. ( 10.1111/j.1420-9101.2010.02001.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Coyne J, Orr H. 1997. ‘Patterns of speciation in Drosophila’ revisited. Evolution 51, 295–303. ( 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1997.tb03650.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fernandes AM. 2013. Fine-scale endemism of Amazonian birds in a threatened landscape. Biodivers. Conserv. 22, 2683–2694. ( 10.1007/s10531-013-0546-9) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Weir JT, Price TD. 2011. Limits to speciation inferred from times to secondary sympatry and ages of hybridizing species along a latitudinal gradient. Am. Nat. 177, 462–469. ( 10.1086/658910) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Illumina short read data have been deposited in the National Center for Biotechnology Information Sequence Read Archive under BioProjects PRJNA433557 and PRJNA433538 (see electronic supplementary material, database S1 and S2).