Significance

p53 is widely perceived as a determinant of sensitivity to radio-/chemotherapy. We report a distinct mechanism whereby p53-regulated MDM2 works together with MDMX to modulate sensitivity to DNA damage by controlling EZH2 (enhancer of zeste homolog 2) turnover. Our work uncovers a mechanism of chromatin modification underlying tissue sensitivity to DNA damage. The MDM2/MDMX disruptor can be used for protecting renewable tissues from chemo-/radiotherapy-induced damage, and the EZH2 inhibitor for sensitizing p53-mutant cancer cells to chemo-/radiotherapy.

Keywords: DNA damage sensitivity, p53/MDM2/MDMX, EZH2, chromatin architecture, epigenetic modifications

Abstract

Renewable tissues exhibit heightened sensitivity to DNA damage, which is thought to result from a high level of p53. However, cell proliferation in renewable tissues requires p53 down-regulation, creating an apparent discrepancy between the p53 level and elevated sensitivity to DNA damage. Using a combination of genetic mouse models and pharmacologic inhibitors, we demonstrate that it is p53-regulated MDM2 that functions together with MDMX to regulate DNA damage sensitivity by targeting EZH2 (enhancer of zeste homolog 2) for ubiquitination/degradation. As a methyltransferase, EZH2 promotes H3K27me3, and therefore chromatin compaction, to determine sensitivity to DNA damage. We demonstrate that genetic and pharmacologic interference of the association between MDM2 and MDMX stabilizes EZH2, resulting in protection of renewable tissues from radio-/chemotherapy-induced acute injury. In cells with p53 mutation, there are diminished MDM2 levels, and thus accumulation of EZH2, underpinning the resistant phenotype. Our work uncovers an epigenetic mechanism behind tissue sensitivity to DNA damage, carrying important translation implications.

Chemo- and radiotherapy remain the primary cancer treatments. Although they are successful to some extent, such treatments also damage healthy tissues, leading to adverse effects. There is a pressing need to develop strategies of normal tissue protection, and in particular for the most sensitive renewable tissues (1). One of the major determinants of cellular sensitivity to DNA-damaging agents is p53, which induces apoptosis on activation. The p53 level within a given tissue is thought to determine its sensitivity to DNA damage; for instance, a heightened sensitivity in renewable tissues is often associated with a high level of p53 (1). However, cells in renewable tissues continuously proliferate, which is contingent on p53 down-regulation, as p53 activity is largely incompatible with proliferation (2). As such, p53 in renewable tissues must be actively controlled to permit cell proliferation. Indeed, MDM2 and MDMX, the two chief regulators of p53, are highly expressed in renewable tissues (3) to ensure dynamic p53 turnover and down-regulation, enabling cell proliferation. However, this creates an apparent discrepancy between the p53 level and elevated sensitivity of renewable tissues to DNA damage. We report here that it is p53-regulated MDM2 that, together with MDMX, controls EZH2 (enhancer of zeste homolog 2) turnover to determine tissue sensitivity to DNA-damaging agents.

EZH2 is a histone-lysine N-methyltransferase, the catalytic subunit of the polycomb repressive complex 2 responsible for trimethylation of K27 sites on H3 (H3K27me3). Polycomb repressive complex 2 also facilitates condensation of chromatin and formation of heterochromatin by facilitating recruitment of the PRC1 complex to H3K27me3 (4). Alteration of chromatin architecture can greatly modulate cellular sensitivity to DNA damage (5).

Results

Disassociation of the MDMX/MDM2 Complex Results in Increased Resistance to Radiation and Doxorubicin-Induced Acute Toxicity.

The principal mechanism for both radio- and chemotherapies is the induction of DNA damage, which potently activates p53, resulting in induction of apoptosis. Renewable tissues such as bone marrow, small intestine, spleen, and thymus are thought to be particularly sensitive to DNA-damaging agents as a result of a higher level of p53 (1). However, p53 is typically growth inhibitory and incompatible with cell proliferation, as studies have shown that cell proliferation is usually coupled with p53 down-regulation (2). This contradicting relationship raises the question as to whether p53 is truly responsible for the heightened sensitivity observed in renewable tissues. We addressed this question by using a tamoxifen-inducible Cre knockin mouse model to control p53 protein turnover through the MDM2/MDMX complex (6). Specifically, our model expresses a single amino acid substitution mutant MDMXC462A that is deficient in MDM2 binding, resulting in disruption of the MDM2/MDMX complex and reduced p53 turnover (6). This model is unique in that both p53 and MDM2 are unaltered and MDMXC462A remains proficient in p53 binding. Of note, the heterozygous mdmxC462A/WT mice showed little detectable phenotype under physiological conditions (7).

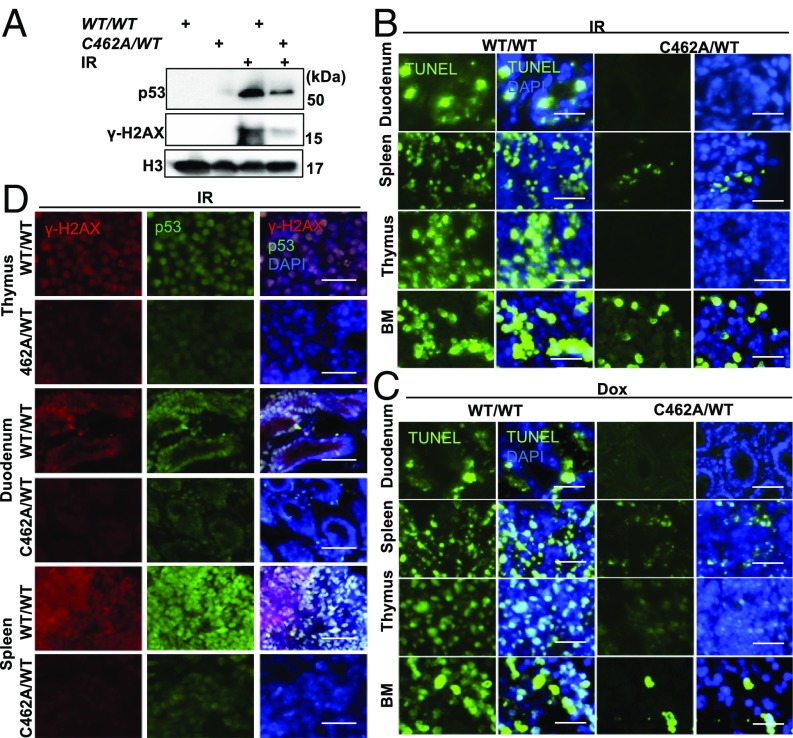

It is well documented that induction of p53 in response to DNA damage is largely a result of the inhibition of MDM2/MDMX-mediated p53 degradation (8). Because of reduced turnover of p53 in mdmxC462A/WT heterozygous cells, we predicted that p53 induction by DNA damage would be exacerbated in these cells. We tested this prediction by comparing thymocytes isolated from mdmxC462A/WT mice with the wild-type littermates for their response to ionizing radiation (IR). Unexpectedly, immunoblot revealed less induction of p53 in thymocytes isolated from mdmxC462A/WT mice compared with wild-type mice (Fig. 1A). In addition, there was considerably less induction of γH2AX, a surrogate marker of DNA damage, in mdmxC462A/WT cells than in wild-type cells. The data suggest that p53 responds to DNA damage in a quantitative manner. The same dose of irradiation induced less DNA damage in mdmxC462A/WT thymocytes, thus resulting in reduced p53 induction compared with the wild-type counterpart.

Fig. 1.

MdmxC462A/WT mice show radiation and doxorubicin resistance. (A) Thymocytes isolated from MdmxWT/WT (WT/WT) and MdmxC462A/WT (C462A/WT) mice were exposed to 8 Gy X-ray, and cells were harvested 1 h post-IR for Western blot with the indicated antibodies. TUNEL analysis of duodenum, spleen, thymus, and bone marrow of MdmxWT/WT and MdmxC462A/WT mice after (B) 5 h of 2.5 Gy IR exposure and (C) 24 h after 20 mg/kg doxorubicin. (D) γ-H2AX and p53 staining of spleen, thymus, and duodenum 1 h post-IR. (Insets) 3× magnified. (Scale bar, 200 μm.)

To confirm the results from isolated thymocytes, we examined tissue response in situ by focusing on sensitive tissues, including bone marrow, duodenum, spleen, and thymus. Mice were induced with tamoxifen and treated with either sham or total body IR at 2.5 Gy or doxorubicin (20 mg/kg, i.p.). The animals were killed 5 or 24 h posttreatment, respectively, and tissues were collected for TUNEL assay. Both IR (Fig. 1B) and doxorubicin (Fig. 1C) induced massive apoptosis in all four tissues in wild-type mice, which was markedly diminished in mdmxC462A/WT mice. Acute toxicity of DNA-damaging agents is frequently associated with atrophy of the spleen and thymus. Consistently, both IR and doxorubicin significantly reduced the size of the spleen and thymus in wild-type mice. This reduction was considerably attenuated in mdmxC462A/WT mice (Fig. S1 A and B). Together, the data indicated that reduced p53 turnover in mdmxC462A/WT mice is associated with enhanced resistance to IR and doxorubicin-induced tissue damage, a phenotype contrary to what we had predicted.

To connect DNA damage-induced apoptosis with the p53 response, we killed animals at 1 h posttreatment with IR to detect the level of γH2AX and p53. Consistent with the apoptotic response, treatment of wild-type mice with IR induced a marked increase of γH2AX and robust p53 induction in the sensitive tissues. When the same treatment was applied to mdmxC462A/WT mice, there was substantially less γH2AX and p53 induction (Fig. 1D). A reduced γH2AX could result from increased DNA repair or intrinsic resistance. We tested this question by measuring IR-induced γH2AX in cells at 10 min posttreatment, when the DNA repair machinery is yet activated. We found that in contrast to the significant increase of γH2AX in cell isolate from wild-type mice, there was little induction of γH2AX in cells isolated from mdmxC462A/WT mice (Fig. S1C). The results together suggest an increased DNA damage resistance in mdmxC462A/WT mice.

Sensitivity to DNA Damage Correlates with Chromatin Compaction and EZH2-Dependent Histone Methylation.

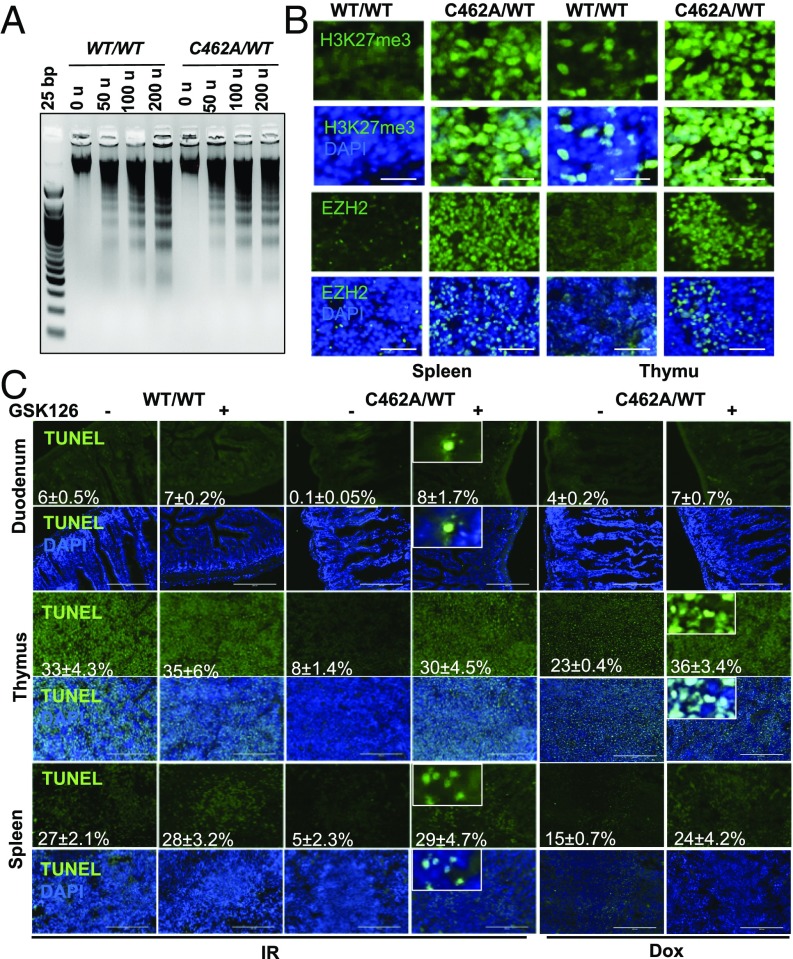

Next, we wanted to investigate the underlying mechanism behind the unexpected resistance of mdmxC462A/WT mice to DNA damage. The markedly reduced γH2AX foci in IR-treated mdmxC462A/WT mice led us to explore a potential contribution of chromatin architecture, which is known to modulate sensitivity to DNA damage (5). We adopted a well-established micrococcal nuclease digestion assay to assess chromatin accessibility as an indirect measurement of chromatin compaction (9). MNase digestion of chromatin preparations produced more monosomes in splenocytes isolated from wild-type mice than in mdmxC462A/WT mice (Fig. 2A and Fig. S2B). Less compacted chromatin was also observed in bone marrow cells isolated from wild-type mice relative to mdmxC462A/WT mice (Fig. S2A). The data together suggest a more compacted chromatin in mdmxC462A/WT cells than in wild-type controls.

Fig. 2.

EZH2 and H3K27me3 protein levels are elevated in MdmxC462A/WT mice. (A) MNase assay of isolated splenocytes from indicated mice. (B) Immunofluorescence for H3K27me3 (Top) and EZH2 (Bottom) in spleen and thymus of indicated mice. (C) The indicated mice were pretreated either with vehicle or 150 mg/kg of GSK126 immunoprecipitation (IP) for 19 h, followed by treatments with 2.5 Gy IR or 20 mg/kg doxorubicin. TUNEL assay was performed as described in Fig. 1 in duodenum, thymus, and spleen. (Insets) 2× magnified.

To substantiate the results obtained from MNase assay, we explored potential changes that might affect chromatin architectures. Abundant evidence indicates that chromatin dynamics are highly regulated by histone modifications (5). Among the various types of modifications, histone H3K27 trimethylation, or H3K27me3, critically contributes to chromatin compaction (7). We thus examined the status of H3K27me3, using immunohistochemistry. The results revealed an apparent increase in H3K27me3 in the spleen and thymus (Fig. 2B, Top) from mdmxC462A/WT mice compared with wild-type counterparts, correlating with the difference in chromatin compaction. Methylation of lysine 27 on histone H3 is primarily mediated by polycomb repressive complex 2, in which EZH2 is the methyltransferase that catalyzes H3K27 di-methylation and trimethylation (H3K27me2/3) (10). We thus asked whether this methyltransferase was involved in the histone methylation observed in our model. We reasoned that if EZH2 were responsible for H3K27me3, which determines sensitivity to DNA damage, then the level of EZH2 expression would correlate with tissue sensitivity to DNA damage. Indeed, immunohistochemistry analysis indicated that EZH2 was preferentially expressed in the renewable tissues (Fig. S2D). Moreover, the spleen, thymus, and duodenum isolated from mdmxC462A/WT mice expressed higher EZH2 levels than in wild-type mice (Fig. 2B, Bottom), which was further confirmed by immunoblot analysis of cells isolated from ACTB-Cre mice (Fig. S2 D and E).

To directly link EZH2-mediated H3K27me3 to tissue response, we used a commercially available specific EZH2 inhibitor, GSK126 (10). Treatment of mice with GSK126 inhibited the methyltransferase activity of EZH2, as indicated by the considerable reduction of H3K273 staining (Fig. S3B) and chromatin compaction (Fig. S3A). In contrast to wild-type mice, in which inhibition of EZH2 showed minimal effect, pretreatment of mdmxC462A/WT mice with GSK126 substantially augmented IR and doxorubicin-induced apoptosis (Fig. 2C). We corroborated the results by using RNAi to knockdown EZH2 in thymocytes. Depletion of EZH2 expression (Fig. S3C) abrogated the resistance of mdmxC462A/WT thymocytes to IR-induced cell death (Fig. S3D). Treatment of isolated thymocytes with GSK126 resulted in an effect similar to siEZH2 (Fig. S3E). Collectively, the data are consistent with a notion that EZH2-induced H3K27me3 promotes chromatin compaction, resulting in a DNA-damage-resistant phenotype.

Identification of EZH2 as a Substrate of MDM2/MDMX E3 Ligase.

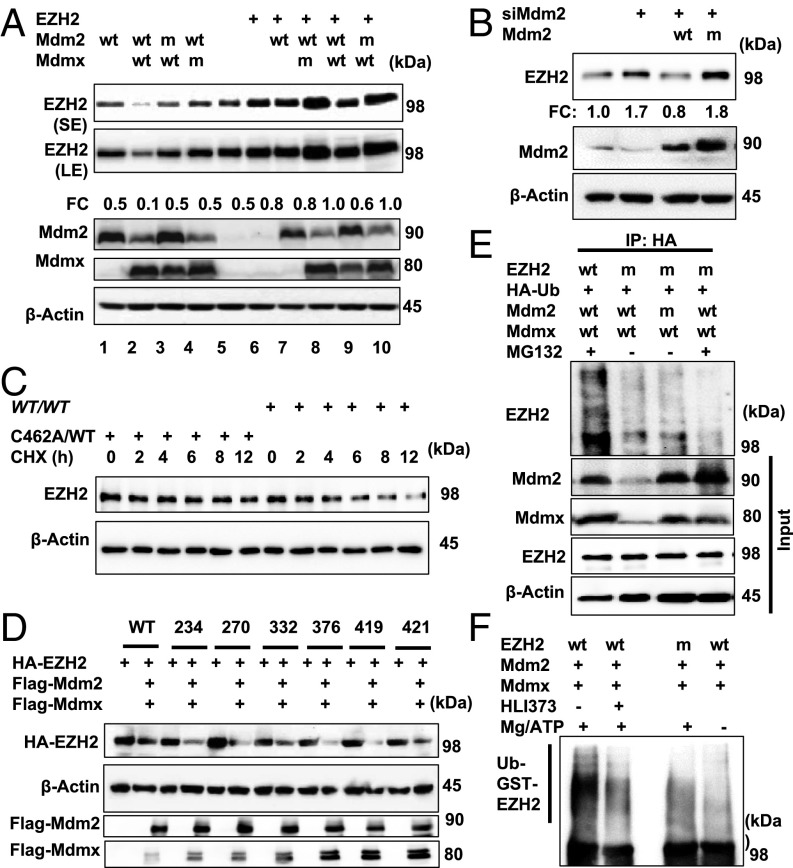

Having observed that the resistance of mdmxC462A/WT mice to DNA damage was mediated by elevated EZH2 level in the renewable tissues, we next explored the mechanism behind EZH2 regulation. There was no detectable difference in EZH2 mRNA level between mdmxC462A/WT mice and the wild-type littermates (Fig. S4A), suggesting a mechanism of posttranscriptional regulation. The mdmxC462A/WT mice exhibit decreased E3 ligase activity because the MDM2/MDMX complex level is reduced to one-half of the wild-type mice. With a recent study reporting a physical interaction between MDM2 and EZH2 (11), we explored whether MDM2/MDMX could function as an E3 ligase to target EZH2 for ubiquitination/degradation. 293T cells were cotransfected with MDM2 or MDMX singly or in combination. Their effects on the level of endogenous EZH2 (Fig. 3A, lanes 1–5) were assessed using immunoblot analysis. The results indicate that MDM2 induced marked reduction of EZH2 abundance only when expressed together with MDMX (Fig. 3A, lane 2). This effect required E3 ligase activity and an intact MDM2/MDMX complex, as both E3 ligase-defective MDM2 mutant and the MDMX mutant defective in MDM2-binding failed to show any detectable effect on EZH2 (lanes 3 and 4). Exogenously expressed EZH2 protein was also ubiquitinated (Fig. S4C) and down-regulated by MDM2/MDMX in an E3 ligase-dependent manner (Fig. 3A, lanes 6–10).

Fig. 3.

Mdm2/Mdmx complex acts as an E3 ubiquitin ligase of EZH2. (A) Western blot with the indicated antibodies of HEK293FT cells transfected with indicated plasmids. (B) Western blot for EZH2 and Mdm2 in H1299 cells transfected with siMdm2-5′UTR alone or prior Flag-Mdm2-WT/C463A and Flag-Mdmx-WT plasmids. (C) Half-life of EZH2 was determined with splenocytes isolated from indicated mice. (D) Western blot for HA-EZH2, Flag-Mdm2, and Flag-Mdmx in HEK293FT cells transfected with indicated plasmids. (E) In vivo ubiquitination assay of EZH2 in HEK293FT transfected with indicated plasmids followed by IP with anti-HA antibody. (F) In vitro ubiquitination assay of GST-EZH2-WT or GST-EZH2-K332R with or without 10 μM HLI373 pretreatment for 30 min, followed by EZH2 Western blot.

To corroborate the results, we employed RNAi to knockdown MDM2, which resulted in markedly increased EZH2 abundance. Importantly, this increase was completely reversed by re-expression of wild-type MDM2, but not with the E3 ligase mutant (Fig. 3B), confirming an E3 ligase-dependent mechanism of EZH2 regulation. The data together suggest that MDM2/MDMX is an E3 ligase for EZH2, which corresponds with the increased EZH2 abundance in mdmxC462A/WT cells. Indeed, measurement of EZH2 half-life revealed a greater stability of EZH2 in mdmxC462A/WT cells than in wild-type controls (Fig. 3C and Fig. S4D). To further validate MDM2/MDMX-mediated EZH2 ubiquitination, we mapped potential ubiquitination sites. A series of EZH2 mutants was generated by replacing lysine residues that are predicted as potential ubiquitination sites by the UbPred program with arginine (www.ubpred.org). When cotransfected with MDM2/MDMX, only the K332R EZH2 mutant exhibited resistance (Fig. 3D and Fig. S4E). We verified the result with an in vivo ubiquitination assay, which showed that the abundant ubiquitination signal found with wild-type EZH2 was almost completely diminished in the K332R mutant (Fig. 3E). As further support, we carried out an in vitro ubiquitination assay by incubating purified wild-type or K332R EZH2 with MDM2/MDMX complex. As shown in Fig. 3F, the addition of ATP stimulated a robust increase in ubiquitination of wild-type, but not K332R, EZH2. HLI373, a specific MDM2 E3 ligase inhibitor (12), also diminished EZH2 ubiquitination. Collectively, the data demonstrate that the MDM2/MDMX complex is a ubiquitin E3 ligase for EZH2.

Use a Pharmacologic Approach to Control MDM2/MDMX-Mediated EZH2 Turnover.

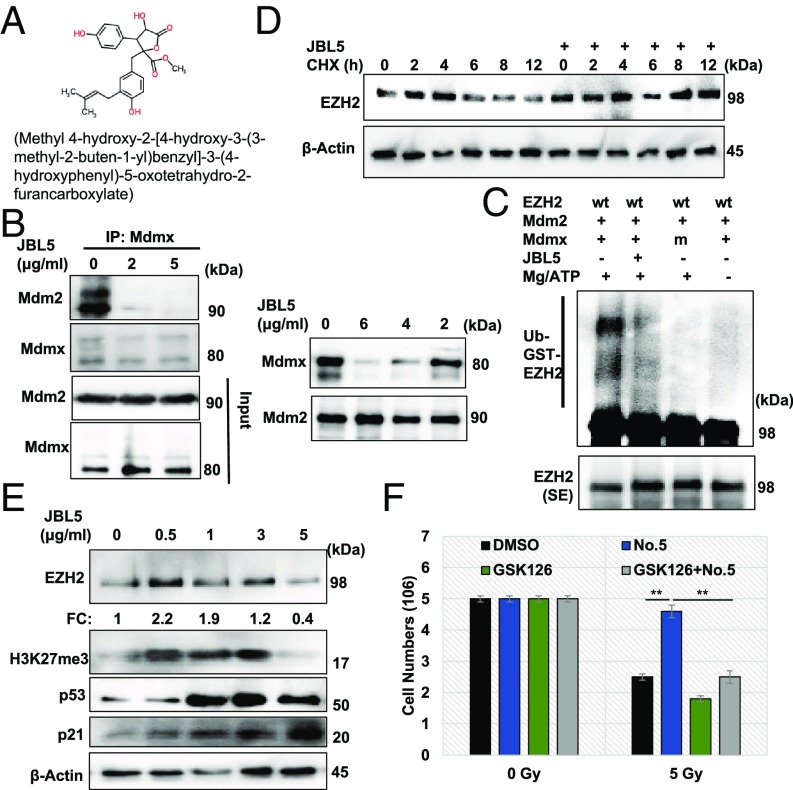

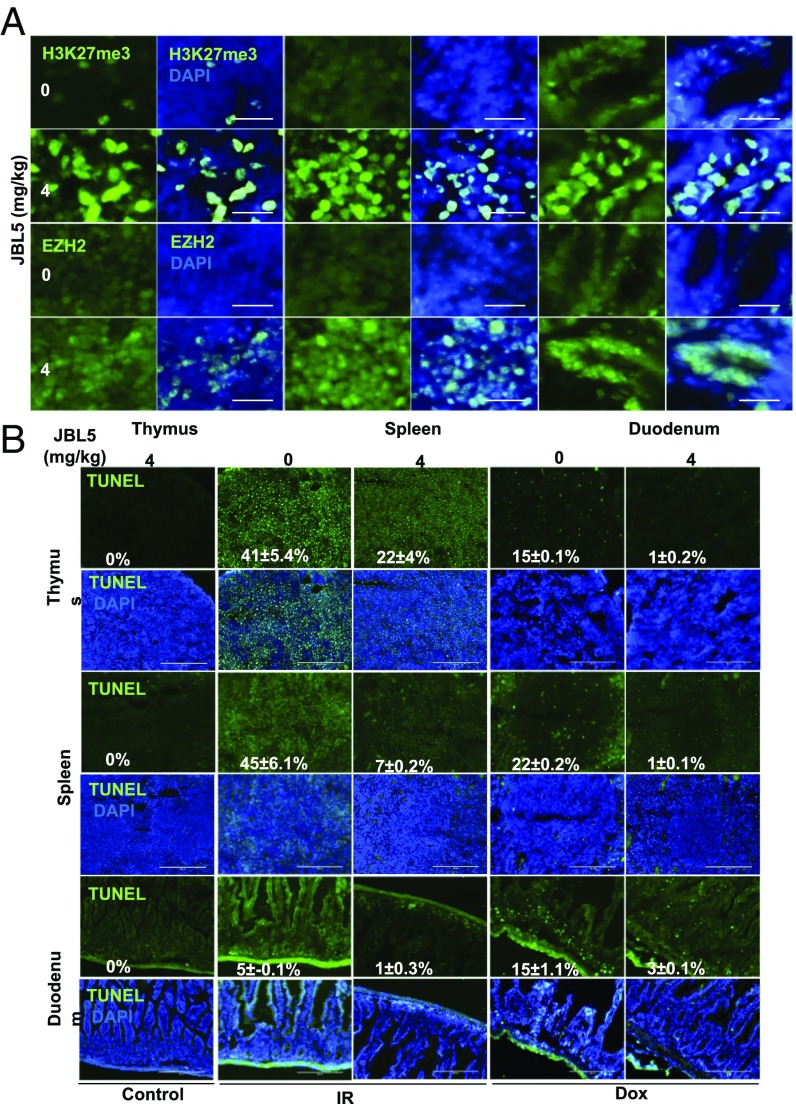

The data derived from mdmxC462A/WT mice have provided proof-of-concept evidence demonstrating that stabilization of EZH2 via impeding MDM2/MDMX-mediated degradation can serve as an effective strategy to protect sensitive tissues against cytotoxic agents. We sought to use a small molecular MDM2/MDMX disruptor, named JBL5 (Fig. 4A), to attenuate MDM2/MDMX-mediated EZH2 turnover. Treatment of splenocytes with JBL5 resulted in disassociation of the MDM2/MDMX complex (Fig. 4B, Left). The effect of JBL5 was further validated with an in vitro binding assay (Fig. 4B, Right). In addition, in vitro ubiquitination assay confirmed that MDM2/MDMX was the direct target of JBL5 (Fig. 4C). Treatment of splenocytes with JBL5 was associated with increased half-life of EZH2 (Fig. 4D and Fig. S5A). We tested a range of doses and found that JBL5 at 0.5–2 μg/mL induced EZH2 levels, but did not significantly induce p21 (Fig. 4E) or inhibit cell proliferation (Fig. S5B). Treatment of cells with JBL5 (2 μg/mL) significantly attenuated IR-induced killing, reminiscent of the results with mdmxC462A/WT cells. The protective effect of JBL5 appeared to be mediated through EZH2 because this effect was completely reversed by the EZH2 inhibitor, GSK126 (Fig. 4F). When administered in mice, JBL5 induced a considerable increase in EZH2 abundance in the duodenum, spleen, and thymus, and the toxicity was not apparent until doses greater than 20 mg/kg (Fig. S5C). Our goal was to use a pharmacologic approach to mimic the genetic model of mdmxC462A/WT mice, and we therefore selected a dose of 4 mg/kg that caused little toxic effect for subsequent in vivo experiments. Treatment of mice with JBL5 resulted in increased EZH2 abundance and H3K27me3 in the duodenum, spleen, and thymus (Fig. 5A), similar to what was observed in mdmxC462A/WT mice. Remarkably, JBL5 treatment was associated with substantially diminished apoptosis induced by IR and doxorubicin in all three sensitive tissues (Fig. 5B), implying that pharmacologic inhibition of MDM2/MDMX-mediated EZH2 degradation has the potential to protect renewable tissues from chemo- and radiotherapy-induced acute injury.

Fig. 4.

Mdm2/Mdmx complex disruptor JBL5 inhibits MDM2/MDMX-mediated ubiquitination and degradation of EZH2 protein. (A) Chemical structure of JBL5. (B) Splenocytes were treated with 0, 2, or 5 μg/mL JBL5 for 24 h, followed by IP with anti-Mdmx antibody and immunoblot (Left). Purified MDMX was incubated with 0, 2, 4, or 6 μg/mL for 30 min. MDM2 was then added. After incubation for 1 h, MDM2 IP was carried out, followed by Western with MDM2 or MDMX antibody (Right). (C) In vitro ubiquitination assay of GST-EZH2-WT with or without 2 μg/mL JBL5 pretreatment for 30 min, followed by EZH2 Western. (D) Half-life of EZH2 in splenocytes pretreated with 2 μg/mL JBL5 for 24 h, followed by 100 μg/mL CHX. (E) Thymocytes isolated from wild-type mice were treated with an increasing dose of JBL5 for 12 h, followed by Western blot with the indicated antibodies. (F) Thymocytes were treated with JBL5 2 μg/mL or JBL5 + 2 μM GSK126 for 24 h, followed by 0 or 5 Gy IR, and 48 h later, cell numbers were counted. Data are mean ± SEM, n = 3. **P < 0.001.

Fig. 5.

JBL5 protects sensitive tissues from radiation and doxorubicin induced apoptosis. (A). Wild-type mice were treated with 0 or 4 mg/kg JBL5 for 19 h. The thymus, spleen, and duodenum were harvested and subjected to immunostaining with H3K27me3 or EZH2. (B) TUNEL analysis of thymus, spleen, and duodenum of wild-type mice injected with 4 mg/kg JBL5 IP for 19 h before 2.5 Gy IR or 20 mg/kg doxorubicin.

Highly Elevated EZH2 Renders p53 Mutant Cells Resistant to DNA Damage.

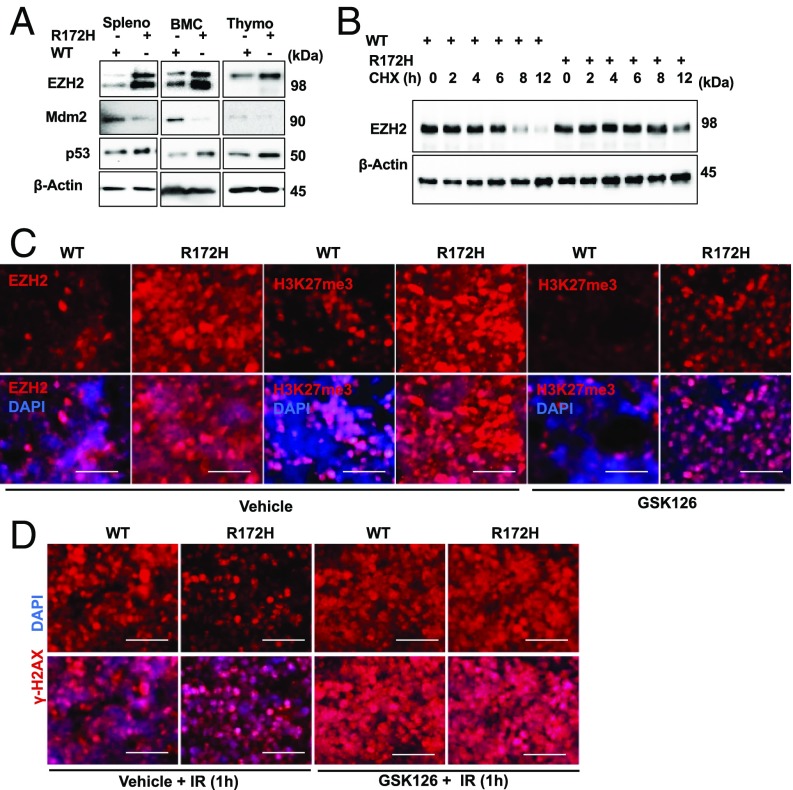

It is widely observed that cells harboring mutant p53 are generally resistant to DNA damage (1). However, the mechanisms behind this resistant phenotype remain incompletely unclear. Because p53 is the principal transcriptional activator of MDM2, p53 mutation frequently leads to loss of MDM2 expression, which would result in elevated EZH2, and therefore increased resistance to DNA damage. We tested this prediction by first comparing the EZH2 level between p53R172H mice and its wild-type littermates. Splenocytes, thymocytes, and BM cells isolated from p53R172H mice displayed substantially elevated EZH2 levels compared with wild-type mice (Fig. 6A). The increased EZH2 level was correlated with a lengthened protein half-life (Fig. 6B and Fig. S6A), consistent with an enhanced EZH2 stability in cells with p53 mutation resulting from diminished MDM2 expression. Correspondingly, the DNA is more compact in p53R172H cells than in the wild-type controls (Fig. S6B). Next, we used the EZH2 inhibitor to test its role in the modulation of sensitivity to DNA damage in p53R172H mice. Immunohistochemistry analysis revealed that compared with wild-type mice, the spleen, thymus, and duodenum from p53R172H mice displayed considerably higher H3K27me3, which correlated with a higher EZH2 level. Treatment of p53R172H mice with GSK126 induced a noticeable reduction of H3K27me3 (Fig. 6C and Fig. S7, Top), which, remarkably, resulted in substantially heightened radiation sensitivity, as reflected by a marked increase of γ-H2AX in GSK126-treated mice compared with the vehicle-treated control (Fig. 6D and Fig. S7, Bottom). The data together indicate that the elevated EZH2 level resulting from diminished MDM2 expression is at least in part responsible for increased radiation resistance in p53R172H mice.

Fig. 6.

EZH2 protein stability is increased in cells from p53R172H/R172H mice. (A) Western blot for EZH2, Mdm2, p53 from splenocytes, BMCs, and thymocytes of p53WT/WT (WT) and p53R172H/R172H (R172H) mice. (B) Half-life of EZH2 in splenocytes isolated from p53WT/WT and p53R172H/R172H mice. (C) EZH2 and H3K27me3 staining in the spleen of p53WT/WT and p53R172H/R172H mice injected with vehicle or 150 mg/kg GSK126 for 16 h. (D) γ-H2AX in spleen after exposure of p53WT/WT and p53R172H/R172H mice to 2.5 Gy IR for 1 h prior vehicle or 150 mg/kg GSK126 injection for 16 h.

Discussion

We used our mdmxC462A/WT mouse model in which p53 turnover is reduced because of a decreased amount of MDM2/MDMX to investigate whether a heightened sensitivity to DNA-damaging agents is a result of a high level of p53. Contrary to our prediction that on exposure to IR or doxorubicin, mdmxC462A/WT mice would exhibit a higher p53 induction and more severe injury than wild-type littermates, both irradiation and doxorubicin induced a smaller increase in p53 in mdmxC462A/WT mice compared with the wild-type littermates. The decreased p53 induction appeared to be the result of less DNA damage induced in mdmxC462A/WTmice, which correlated with lesser apoptosis. The data indicate that p53 responds to DNA damage in a quantitative fashion. It is the level of DNA damage that dictates the extent of p53 induction, and thereby the magnitude of apoptosis, and mdmxC462A/WT mice are more resistant to DNA damage than the wild-type littermates.

Of interest is the observation that the resistance of mdmxC462A/WT mice to DNA damage resulted from increased chromatin compaction, consistent with the finding that chromatin architecture can have a profound effect on sensitivity to DNA damage, in that condensed chromatin or heterochromatin is more resistant to DNA damage than open or euchromatin (5). In line with the compacted chromatin in mdmxC462A/WT mice, there was a considerable increase in H3K27me3 compared with the wild-type controls. Our data support an epigenetic mechanism in the modulation of DNA damage sensitivity.

In agreement with EZH2 as the primary methyltransferase for H3K27me3 (7, 10), we observed a close correlation between the levels of EZH2 and H3K27me3. Immunohistochemistry analysis revealed that the expression of EZH2 was highly enriched in bone marrow, thymus, spleen, and small intestine, consistent with published result (13). As a protein critically involved in transcriptional repression, it is conceivable that the level of EZH2 is dynamically regulated and down-regulated to meet the active transcriptional needs in proliferative cells. We provide several lines of evidence to demonstrate MDM2/MDMX as an EZH2 E3 ligase: the expression of MDM2 and MDMX is similarly enriched in the renewable tissues; the turnover of EZH2 requires the formation of MDM2/MDMX complex, which is a better E3 ligase than MDM2 alone (6); in vitro ubiquitination assay with purified recombinant proteins demonstrates EZH2 is a direct target of MDM2/MDMX; and identification of the lysine residue 332 as the major site of ubiquitination. The binding of MDM2 to EZH2 was recently published, but that study did not report MDM2-mediated EZH2 turnover (11), which is not inconsistent with our data, as the authors examined the effects of MDM2 alone, and our data indicate that MDM2 by itself is not sufficient to promote EZH2 ubiquitination. Although further validation is necessary, our data indicate that the small molecule MDM2/MDMX disruptor was effective in EZH2 stabilization that resulted in marked protection of susceptible tissues from IR-induced acute injury.

Ample evidence indicates that p53 inactivation in tumor cells contributes to increased resistance to chemo-/radiotherapy (1). Numerous mechanisms such as compromised apoptosis and senescence have been reported to contribute to the resistance phenotype of p53 mutant tumors. We have uncovered EZH2-mediated regulation of chromatin compaction as an additional mechanism to modulate cellular sensitivity to DNA damage. In line with the finding that the expression of MDM2 is primarily controlled by p53 (3, 8), the level of MDM2 is diminished in cells harboring p53 mutation. As a result, the turnover of EZH2 is severely compromised in p53 mutant-expressing cells, resulting in accumulation of EZH2, providing a molecular basis for the resistant phenotype associated with the p53 mutation. The finding that p53 mutant cells were specifically sensitized by the EZH2 inhibitor can be exploited to sensitize tumors with the p53 mutation to radiation- and chemotherapy-induced killing.

The prosurvival function of EZH2 is widely observed (13, 14). Recent studies have shown that EZH2 inhibition increases the sensitivity to radiation and chemotherapy in various cell types (15, 16). Using complementary genetic and pharmacologic methods, we provided solid evidence indicating EZH2 as one of the important determinants of cellular sensitivity to DNA damage by promoting H3K27me3, and therefore chromatin compaction. We note that MDM2/MDMX-mediated EZH2 regulation plays a critical role in governing cell sensitivity under physiological conditions, or before DNA damage is induced. After DNA damage, additional mechanisms of regulation might be engaged. For instance, p53 could down-regulate EZH2 via inhibition of E2F1, which positively regulates EZH2 expression (17). Thus, DNA-damage-induced EZH2 down-regulation (Fig. S4B) could be also mediated by activated p53, although via distinct mechanisms.

Materials and Methods

Generation of Transgenic Animals and Drug Administration.

All animal procedures were approved by the Harvard University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee protocols under protocol number 04933.

We generated inducible whole-body MdmxC462A/WT mice by crossing Mdmx-C462A flox/flox mice (6) with tamoxifen-inducible Cre-ER mice (#004682; Jackson Lab). Sex-matched 6–8-wk-old mice (n = 3–6 each genotype) were used. p53R172H/R172H mice were kindly provided by Dr R. Medzhitov, Yale University.

Splenocyte, Thymocyte, and Bone Marrow Cell Isolation.

Splenocyte, thymocytes, and bone marrow cells (BMCs) were isolated as described (6). Throughout the experiments, all the isolated primary cells were incubated under the physiological oxygen pressure (5%) in a Heracell 150i CO2 incubator (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

Plasmid Transfection and Gene Silencing by siRNA.

MDM2 and MDMX expression plasmids have been described previously (6). pCMVHA-hEZH2, MSCVhygro-F-Ezh2, and pGEX-EZH2 plasmids were purchased from Addgene (www.addgene.org). The ON-TARGETplus siRNA EZH2 (J-040882–05-0002), Mdm2 (J-003279-11-0002), and nontargeting pool siRNA (d-001206-13) were purchased from Dharmacon (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The siRNA duplexes were electroporated into 1 × 106 isolated thymocytes using Neon Transfection System (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Cells were analyzed 24–48 h after electroporation or transfection, either by Western blot and/or cell counting.

Site-Directed Mutagenesis and qRT-PCR.

Site-directed mutagenesis was performed using QuikChange II XL Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit (Agilent).

For qRT-PCR, total RNA-isolated primary cells were used for the preparation of cDNA, using a high-capacity cDNA reverse transcription kit (BioRad), and for qRT-PCR analyses, using PowerUp SYBR Green Master Mix (Thermo Fisher Scientific). For information on all primers, please see Table S1.

Coimmunoprecipitation, in Vivo and in Vitro Ubiquitination Assays.

For coimmunoprecipitation, thymocytes isolated from mice treated with 2 and 5 μg/mL JBL5 for 24 h were lysed in coimmunoprecipitation buffer. In vitro and in vivo ubiquitination assays were as described in ref. 6.

Immunohistochemistry by Chromogenic and Fluorescence Detection.

Immunohistochemistry was performed using a published procedure (7). Mice tissues spleen, thymus, femur bone, duodenum, liver, lung, testis, kidney, pancreas, muscle, and fat were used to visualize EZH2 and H3K27me3, p53, and γ-H2AX protein expressions. For information on antibodies used, please see Table S2.

TUNEL.

Formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded or cryopreserved tissues harvested from mice were subjected to in situ cell death detection fluorescein (Roche, Sigma-Aldrich Corp) following the manufacturer’s instructions.

MNase assay.

MNase assay was performed with minor modifications, as described (9). Cell lysates were digested with 0.2 mg/mL Proteinase K. Digested gDNA fragment was isolated using ChIP DNA Clean & Concentrator kit (Zymo Research). DNA concentrations were measured by Nanodrop, and 500 ng DNA was run on 2% agarose gel.

Statistical analysis.

Each experiment was repeated at least three times independently. All data were expressed as mean ± SEM. Statistical analysis was determined using two-tailed unpaired Student’s t test. A P value <0.05 was considered significant.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by the Morningside Foundation, the Zhu Fund, and grants from the National Cancer Institute at the National Institute of Health (R01CA85679, R01CA167814, and R01CA125144).

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: Harvard University has filed a provisional patent application on behalf of the investigators claiming some of the concepts contemplated in this publication.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1719532115/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Gudkov AV, Komarova EA. The role of p53 in determining sensitivity to radiotherapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3:117–129. doi: 10.1038/nrc992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zwang Y, et al. Two phases of mitogenic signaling unveil roles for p53 and EGR1 in elimination of inconsistent growth signals. Mol Cell. 2011;42:524–535. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.04.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eischen CM, Lozano G. The Mdm network and its regulation of p53 activities: A rheostat of cancer risk. Hum Mutat. 2014;35:728–737. doi: 10.1002/humu.22524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ding X, et al. The polycomb protein Ezh2 impacts on induced pluripotent stem cell generation. Stem Cells Dev. 2014;23:931–940. doi: 10.1089/scd.2013.0267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cann KL, Dellaire G. Heterochromatin and the DNA damage response: The need to relax. Biochem Cell Biol. 2011;89:45–60. doi: 10.1139/O10-113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Huang L, et al. The p53 inhibitors MDM2/MDMX complex is required for control of p53 activity in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:12001–12006. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1102309108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cao R, et al. Role of histone H3 lysine 27 methylation in polycomb-group silencing. Science. 2002;298:1039–1043. doi: 10.1126/science.1076997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kruiswijk F, Labuschagne CF, Vousden KH. p53 in survival, death and metabolic health: A lifeguard with a licence to kill. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2015;16:393–405. doi: 10.1038/nrm4007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zaret K. Micrococcal nuclease analysis of chromatin structure. Curr Protoc Mol Biol. 2005;Chapter 21:Unit 21.1. doi: 10.1002/0471142727.mb2101s69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McCabe MT, et al. EZH2 inhibition as a therapeutic strategy for lymphoma with EZH2-activating mutations. Nature. 2012;492:108–112. doi: 10.1038/nature11606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wienken M, et al. MDM2 associates with polycomb repressor complex 2 and enhances stemness-promoting chromatin modifications independent of p53. Mol Cell. 2016;61:68–83. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2015.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kitagaki J, Agama KK, Pommier Y, Yang Y, Weissman AM. Targeting tumor cells expressing p53 with a water-soluble inhibitor of Hdm2. Mol Cancer Ther. 2008;7:2445–2454. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-08-0063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lund K, Adams PD, Copland M. EZH2 in normal and malignant hematopoiesis. Leukemia. 2014;28:44–49. doi: 10.1038/leu.2013.288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bachmann IM, et al. EZH2 expression is associated with high proliferation rate and aggressive tumor subgroups in cutaneous melanoma and cancers of the endometrium, prostate, and breast. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:268–273. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.01.5180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fillmore CM, et al. EZH2 inhibition sensitizes BRG1 and EGFR mutant lung tumours to TopoII inhibitors. Nature. 2015;520:239–242. doi: 10.1038/nature14122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Smonskey M, et al. EZH2 inhibition re-sensitizes multidrug resistant B-cell lymphomas to etoposide mediated apoptosis. Oncoscience. 2016;3:21–30. doi: 10.18632/oncoscience.288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Béguelin W, et al. EZH2 enables germinal centre formation through epigenetic silencing of CDKN1A and an Rb-E2F1 feedback loop. Nat Commun. 2017;8:877. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-01029-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.