Abstract

Background

Retinopathy of prematurity (ROP) refers to the developmental disorder of the retina in premature infants and is one of the most serious and most dangerous complications in premature infants. The prevalence of ROP in Iran is different in various parts of Iran and its prevalence is reported to be 1–70% in different regions. This study aims to determine the prevalence and risk factors of ROP in Iran.

Methods

This review article was conducted based on the preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis (PRISMA) protocols. To find literature about ROP in Iran, a comprehensive search was done using MeSH keywords in several online databases such as PubMed, Ovid, Science Direct, EMBASE, Web of Science, CINAHL, EBSCO, Magiran, Iranmedex, SID, Medlib, IranDoc, as well as the Google Scholar search engine until May 2017. Comprehensive Meta-analysis Software (CMA) Version 2 was used for data analysis.

Results

According to 42 studies including 18,000 premature infants, the prevalence of ROP was reported to be 23.5% (95% CI: 20.4–26.8) in Iran. The prevalence of ROP stages 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5 was 7.9% (95% CI: 5.3–11.5), 9.7% (95% CI: 6.1–15.3), 2.8% (95% CI: 1.6–4.9), 2.9% (95% CI: 1.9–4.5) and 3.6% (95% CI: 2.4–5.2), respectively. The prevalence of ROP in Iranian girls and boys premature infants was 18.3% (95% CI: 12.8–25.4) and 18.9% (95% CI: 11.9–28.5), respectively. The lowest prevalence of ROP was in the West of Iran (12.3% [95% CI: 7.6–19.1]), while the highest prevalence was associated with the Center of Iran (24.9% [95% CI: 21.8–28.4]). The prevalence of ROP is increasing according to the year of study, and this relationship is not significant (p = 0.181). The significant risk factors for ROP were small gestational age (p < 0.001), low birth weight (p < 0.001), septicemia (p = 0.021), respiratory distress syndrome (p = 0.036), intraventricular hemorrhage (p = 0.005), continuous positive pressure ventilation (p = 0.023), saturation above 50% (p = 0.023), apnea (p = 0.002), frequency and duration of blood transfusion, oxygen therapy and phototherapy (p < 0.05), whereas pre-eclampsia decreased the prevalence of ROP (p = 0.014).

Conclusion

Considering the high prevalence of ROP in Iran, screening and close supervision by experienced ophthalmologists to diagnose and treat the common complications of pre-maturity and prevent visual impairment or blindness is necessary.

Keywords: Meta-analysis, Retinopathy of prematurity, Iran, Prevalence, Risk factor

Background

Retinopathy of prematurity (ROP) refers to the developmental disorder of the retina in premature infants and is one of the most serious and most dangerous complications in premature infants.

Embryonic retinal arteries start to grow in the third month of pregnancy and their development ends at birth. Therefore, the stages of evolution of the eye are defective in premature infants, and the growth of the vessels is either stopped or unusual, and ultimately, the vessels become very fragile, which can lead to visual impairment in severe cases [1].

Despite considerable progress made in the treatment of ROP, it is still a common cause of reduced vision in children in developed countries, and its prevalence is increasing [2–4]. This is a preventable disease and responds to treatments appropriately if diagnosed at early stages, but in case of delayed diagnosis and treatment, it may lead to blindness [5].

The first incidences of ROP were reported in the 1940s and 1950s, mainly as a result of the use of supplemental oxygen without supervision (first epidemic). Although the survival of premature infants improved in the following decades, and despite improved monitoring methods for oxygen supplements, ROP emerged with an increasing incidence (second epidemic) [6]. Over the past decade, the increasing incidence of ROP blindness has been recorded in low-income countries. Studies show that ROP is the leading cause of blindness in China, Southeast Asia, South America, Latin America, and Eastern Europe, especially in urban centers of newly industrialized countries, and this is referred to as the “third epidemic” [7].

ROP is a multifactorial disease and the most important risk factors are preterm delivery, especially before the 32nd week of gestation and birth weight less than 1500 g. Apnea, intraventricular hemorrhage, various maternal factors (diabetes, preeclampsia, mother’s smoking), respiratory disorders, infection, vitamin E deficiency, heart disease, increased blood carbon dioxide, increased oxygen (O2) consumption, decreased PH, decreased blood O2, bradycardia, transfusion, amount of received oxygen and duration of ventilation are other risk factors for ROP [8–10].

The prevalence of ROP in different regions of Iran is different and its prevalence is reported to be 1–70% in different regions [11–14]. Considering the abovementioned issues and the importance of the subject, as well as the diversity of reports in Iranian studies, it is necessary to carry out more extensive and precise studies. Meta-analysis is a method that collects and analyzes multiple research data with a common purpose to provide a reliable estimate of the impact of some interventions or observations in medicine [15, 16]. Obviously, the sample size in meta-analysis becomes larger by collecting data from several studies and therefore the range of changes and probabilities will be reduced; therefore, the significance of statistical results increases [16, 17]. This study aims to determine the incidence and risk factors for ROP in Iran.

Methods

Study protocol

This review article was conducted based on the preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis (PRISMA) protocols [16]. The study was conducted in five stages: design and search strategy, a collection of articles and their systematic review, evaluation of inclusion and exclusion criteria, qualitative evaluation and statistical analysis of data. To avoid bias in the study, each of the above steps was carried out by two researchers independently. In case of differences in the results obtained by the two researchers, a third researcher intervened to reach an agreement.

Search strategy

To find literature about ROP in Iran, a comprehensive search was done using the terms (Retinopathy of Prematurity [MeSH]) AND (“Incidence” [MeSH] OR “Epidemiology” [MeSH]), OR (“Prevalence” [MeSH]) AND (“Iran” [MeSH]) in 7 international databases including PubMed, Ovid, Science Direct, EMBASE, Web of Science, CINAHL, EBSCO, and 5 national databases including Magiran, Iranmedex, SID, Medlib, IranDoc, as well as Google Scholar search engine until May 2017. References to all relevant articles were reviewed. Due to the inability of Iranian databases to search using Boolean operators (AND, OR and NOT), searches on these databases were only performed using the keywords.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Articles with the following characteristics were chosen for meta-analysis: 1. Original research papers published either in Persian or English; 2. Medical dissertations; 3. Review of the prevalence or risk factors for ROP. The exclusion criteria were: 1. Non-random sample for estimating the prevalence; 2. Being irrelevant to the topic; 3. Congress papers; 4. Sample size other than premature infants; 5. Non-Iranian studies; 6. Review articles, case reports, editorials; 7. Duplicate studies and 8. Low-quality studies.

ROP detection criteria

ROP was diagnosed by an expert through examination of retinas of infants using indirect ophthalmoscope.

Selection of studies

First, all related articles (articles with affiliations containing Iranian authors) were collected and a list of titles was prepared at the end of the search and removal of duplicates. After blinding the specifications of the articles by on researcher (Milad Azami), including the name of the journal and the name of the author, the full text of the articles was presented to the researchers. Each article was studied by two researchers independently (Gholamreza Badfar, Afsar Dastjani Farahani). If the article was rejected, the reason for this rejection was mentioned. In case of disagreement between the two authors, the article was judged by the team of researchers.

Quality of studies

Using the standard modified Newcastle Ottawa Scale (NOS) checklist [18], which included 8 sections. Thus, the minimum and maximum score available on this checklist were 0 and 8, respectively. Accordingly, the studies were divided into three categories: 1. low quality with a score less than 5; 2. moderate quality with a score of 5–6; and 3. high quality with a score of 7–8. Finally, the moderate to high quality studies were selected for the meta-analysis stage.

Data extraction

The raw data of the prepared articles were extracted using a premade checklist. The checklist includes the name of the authors, published year the year of study, the location of the study, the study design, quality score, sample size, the prevalence of ROP, the ROP detection criteria, the prevalence of ROP based on gender (ROP) and ROP risk factors.

Statistical analysis

In each study, the prevalence of ROP was considered as the probability of binomial distribution. To evaluate the heterogeneity of the studies, Cochran’s Q test and I2 index were used [19]. There are three categories for the I2 index: heterogeneity lower than 25%, heterogeneity between 25% and 75% and heterogeneity more than 75%. Considering the heterogeneity of the studies, a random effects model was used to combine ROP prevalence. For ROP risk factors, the fixed effects model and the random effects model were used, respectively in the case of low heterogeneity and high heterogeneity in the meta-analysis [20, 21]. Sensitivity analysis was performed to identify the influence of a single study on the combined result incidence or any risk factors (with ≥ 7 studies). In order to identify the cause of heterogeneity of ROP prevalence, sub-groups analysis of ROP were carried out based on geographical region, province and quality of studies, while the meta-regression model (method of moments) was carried out based on the year of studies [22]. Egger and Begg’s tests were used to identify publications bias. Data analysis was performed using Comprehensive Meta-Analysis Software Version 2 and the significance level in the tests was considered to be lower than 0.05.

Results

Search results and characteristics

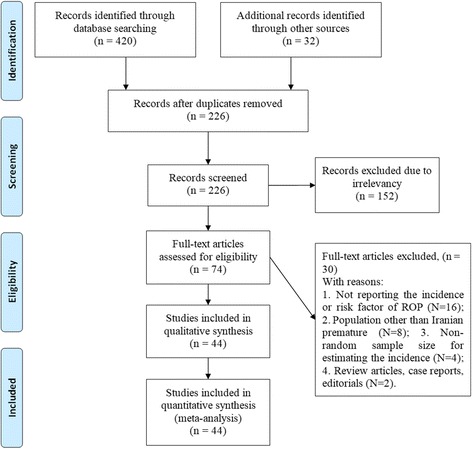

In the initial search, 452 studies were found to be related to the topic. Two independent researchers reviewed the title and the abstract. If the title or abstract was likely to be related to the topic, the full text was reviewed. After reviewing the full text of 74 relevant articles, 30 articles were omitted due to lacking the necessary criteria and finally 44 qualified studies entered the qualitative assessment stage (Fig. 1). Table 1 shows the characteristics of each study.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flowchart for the selection of studies

Table 1.

Summary of demographic characteristics in studies into a meta-analysis

| Ref. | First author, Published Year | Year of study | GAa (week) | BWb (gr) | Place | Sample size | Prevalence (%) | Quality | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | Non-ROPc | ROP | ||||||||

| [11] | Naderian Gh, 2011 | 2009 | < 34 | And ≤ 1800 | Isfahan | 100 | 71 | 29 | 29 | Moderate |

| [11] | Naderian Gh(1), 2011 | 2009 | < 34 | And ≤ 1800 | Isfahan | 100 | 58 | 42 | 42 | Moderate |

| [12, 13] | Mostafa Gharebagh M, 2012 | 2008 | < 34 | – | Tabriz | 71 | 41 | 30 | High | |

| [14] | Nakhshab M, 2016 | 2014 | < 30 or < 34d | – | Sari | 146 | 122 | 24 | 16.44 | High |

| [52] | Naderian G, 2009 | 2002 | 25–34 | And 600–1800 | Isfahan | 796 | 662 | 134 | 16.8 | Moderate |

| [53] | Hosseini H, 2009 | 2006 | < 34 | – | Shiraz | 1024 | 1004 | 20 | 1.95 | High |

| [54] | Karkhaneh R, 2005 | 2000 | ≤ 37 | And ≤ 2500 | Tehran | 185 | 162 | 23 | 12.4 | High |

| [55] | Naderian G, 2010 | 2003 | – | – | Isfahan | 604 | 498 | 106 | 17.5 | High |

| [56] | Mansouri M, 2007 | 2004 | ≤ 32 | And ≤ 1500 | Tehran | 147 | 103 | 44 | 29.9 | High |

| [57] | Nakshab M, 2003 | 2001 | – | ≤ 2500 | Sari | 68 | 60 | 8 | 11.7 | High |

| [58] | Daraie G, 2016 | 2008 | < 37 | Or < 2000 | Semnan | 270 | 267 | 3 | 1.1 | Moderate |

| [59] | Fayazi A,2009 | 2005 | < 32 | Or < 1500 or 1500–2500* | Tabriz | 399 | 370 | 29 | 7.26 | Moderate |

| [60] | Sadeghi K, 2008 | 2006 | < 36 | And < 2000 | Tabriz | 150 | 124 | 26 | 17.3 | Moderate |

| [61] | Ebrahimiadib N, 2016 | 2011 | < 37 | Or < 3000 | Tehran | 1896 | 1326 | 570 | 30.06 | Moderate |

| [62] | Ghaseminejad A, 2011 | 2006 | ≤ 36 | And ≤ 2500 | Kerman | 83 | 59 | 24 | 29 | High |

| [63] | Khatami F, 2008 | 2000 | < 34 | Or < 2000 | Mashhad | 50 | 36 | 14 | 28 | Moderate |

| [64] | Sabzehei MK, 2013 | 2007 | – | < 1500 | Tehran | 414 | 343 | 71 | 17.14 | Moderate |

| [65] | Saeidi R, 2009 | 2005 | ≤ 32 | Or < 1500 | Mashhad | 47 | 43 | 4 | 8.5 | Moderate |

| [66] | Azin Far B, 2005 | 2001 | < 29 | And < 1500 | Babol | 100 | 56 | 44 | 44 | High |

| [67] | Karkhanehyousefi N, 2009 | 2009 | – | – | Babol | 100 | 61 | 39 | 39 | Moderate |

| [68] | Ebrahimzadeh A, 2009 | 2003 | – | – | Tehran | 1343 | 874 | 469 | 34.9 | High |

| [69] | Mirzaee SA, 2010 | 2008 | – | < 2000 | Tehran | 74 | 50 | 24 | 324 | Moderate |

| [70] | Mousavi Z, 2009 | 2001 | 24–36 | And 600–2900 | Tehran | 797 | 540 | 257 | 32.24 | Moderate |

| [71] | Fouladinejad M, 2009 | 2004 | ≤ 34 | – | Gorgan | 89 | 84 | 5 | 5.6 | High |

| [72] | Mousavi S, 2008 | 2001 | 24–36 | And 600–2800 | Tehran | 693 | 474 | 219 | 31.6 | Moderate |

| [73] | Sadeghzadeh M, 2016 | 2001 | – | 450–3000 | Zanjan | 78 | 77 | 1 | 1.2 | Moderate |

| [74] | Bayat-Mokhtari M, 2010 | 2006 | – | < 1500 Or 1500–2000* | Shiraz | 199 | 115 | 84 | 42 | High |

| [75] | Karkhaneh R, 2001 | 1997 | < 37 | Or < 2500 | Tehran | 150 | 141 | 9 | 6 | High |

| [76] | Babaei H, 2012 | 2009 | – | ≤ 1500 | Kermanshah | 84 | 73 | 11 | 13.1 | Moderate |

| [77] | Abrishami M, 2013 | 2006 | < 32 | – | Mashhad | 122 | 90 | 32 | 26.2 | High |

| [78] | Riazi-Esfahani M, 2008 | 2002 | ≤ 37 | And ≤ 2500 | Tehran | 165 | 125 | 40 | 24.24 | Moderate |

| [79] | Alizadeh Y, 2015 | 2005 | ≤ 36 | And ≤ 2500 | Rasht | 310 | 246 | 64 | 20.6 | High |

| [80] | Mousavi SZ, 2010 | 2003 | – | – | Tehran | 605 | 415 | 190 | 31.4 | Moderate |

| [81] | Mousavi Z, 2010 | 2003 | – | – | Tehran | 1053 | 673 | 380 | 36.1 | High |

| [82] | Feghhi M, 2012 | 2006 | < 32 | And ≤ 2000 | Ahvaz | 576 | 393 | 183 | 32 | High |

| [83] | Afarid M, 2012 | 2006 | ≤ 32 | And ≤ 2000 | Shiraz | 787 | 494 | 293 | 37.2 | Moderate |

| [84] | Ahmadpourkacho M, 2014 | 2009 | < 28 | And < 1500 or 1500–2000* | Babol | 256 | 76 | 180 | 70.31 | High |

| [85] | AhmadpourKacho M, 2014 | 2007 | < 34 | And < 2000 | Babol | 155 | 85 | 70 | 45.2 | Moderate |

| [86] | Rasoulinejad SA, 2016 | 2007 | < 36 | And < 2500 | Babol | 680 | 374 | 306 | 45 | High |

| [87] | Karkhaneh R, 2008 | 2003 | < 37 | – | Tehran | 953 | 624 | 329 | 34.5 | High |

| [88] | Khalesi N, 2015 | 2013 | – | – | Tehran | 120 | 60 | 60 | Moderate | |

| [89] | Ebrahim M, 2010 | 2004 | < 37 | – | Babol | 173 | 140 | 33 | 19.1 | High |

| [90] | Roohipoor R, 2016 | 2012 | ≤ 37 | And ≤ 3000 | Tehran | 1932 | 1362 | 570 | 3 | High |

| [91] | Mansouri M, 2016 | 2013 | < 34 | Or < 2000 | Sanandaj | 47 | 42 | 5 | 10.6 | High |

aGestational age; bBirth weight; cRetinopathy of prematurity; dWith unstable condition

Prevalence

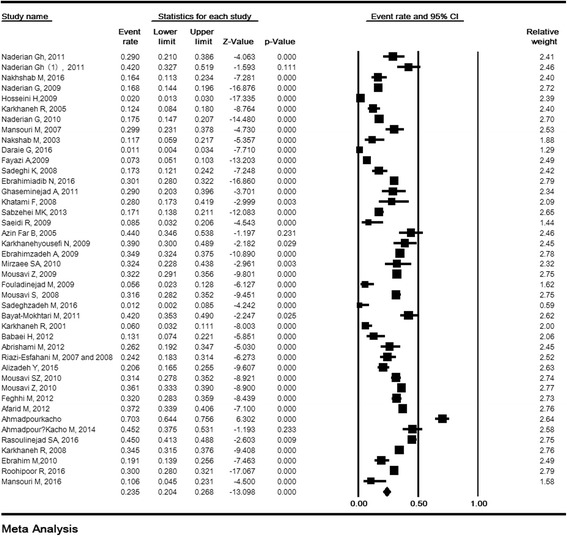

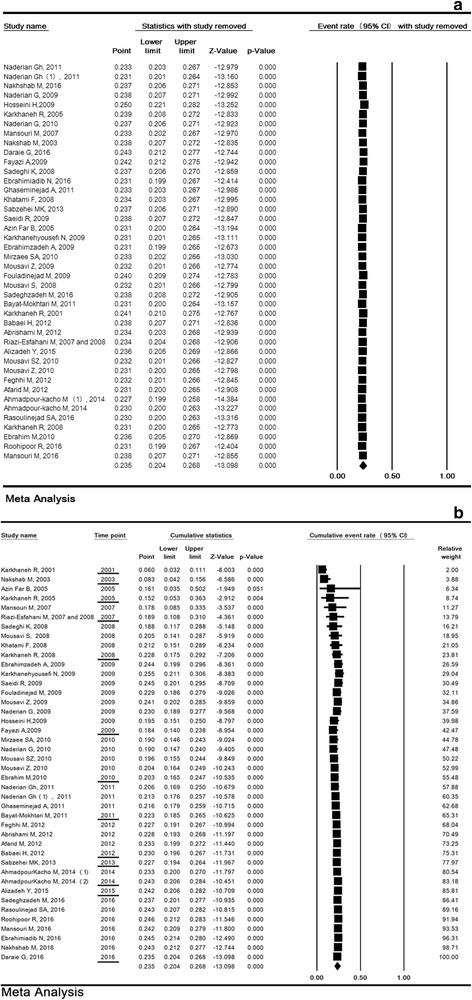

Reviewing 42 studies with a total sample size of 18,000 premature infants, the prevalence of ROP in Iran was estimated to be 23.5% (95% CI: 20.4–26.8). The lowest and highest prevalence was related to the studies in Semnan (2008) (1.1%) (58) and in Babol (2009) (70.3%) (84), respectively (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

The prevalence of retinopathy of prematurity in Iran. Random effects model

Sensitivity analysis and cumulative analysis for ROP

The sensitivity analysis of the prevalence or risk factors of ROP and its 95% confidence interval (CI) was estimated simultaneously regardless of one study and the results showed that the incidence or risk factors of ROP were not significantly changed before and after the deletion of each study. (Fig. 3a). Cumulative analysis for incidence of ROP based on the year of publication is shown in Fig. 3b.

Fig. 3.

Sensitivity analysis (a) and cumulative analysis based on the year of publication (b) for prevalence of retinopathy of prematurity in Iran. Random effects model

Subgroup analysis of ROP prevalence based on geographic region

In the reviewed studies, 2, 4, 12, 4, and 20 studies were related to the West, East, North, South, and Center of Iran, respectively. The prevalence of ROP in the five regions of Iran is shown in Table 2 and the lowest incidence of ROP was in west of Iran (12.3% [95% CI: 7.6–19.1]), while the highest prevalence was related to the center of Iran (24.9% [95% CI: 21.8–28.4]) (Table 2).

Table 2.

The prevalence of ROP based on region, gender, provinces and quality of studies

| Variable | Studies (Na) | Sample (N) | Heterogeneity | 95% CIb | Prevalence (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I2 | P-Value | ||||||

| Region | Center | 20 | 12,355 | 93.65 | < 0.001 | 21.8 to 28.4 | 24.9 |

| East | 4 | 302 | 57.79 | 0.07 | 17 to 33 | 24.1 | |

| North | 12 | 2626 | 97.09 | < 0.001 | 15.9 to 37.1 | 25 | |

| South | 4 | 2586 | 98.60 | < 0.001 | 9.2 to 37.1 | 20.5 | |

| West | 2 | 131 | 0 | 0.67 | 7.6 to 19.1 | 12.3 | |

| Test for subgroup differences: Q = 9.67, df(Q) = 4, P = 0.046 | |||||||

| Gender | Boys | 11 | 1467 | 92.65 | < 0.001 | 11.9 to 28.5 | 18.9 |

| Girls | 11 | 1184 | 85.02 | < 0.001 | 12.8 to 25.4 | 18.3 | |

| Rate ratio of boys to girls: ORc = 1.07(0.86 to 1.33, P = 0.501) | |||||||

| Provinces | Khozestan | 1 | 576 | 0 | – | 28.3 to 35.9 | 32 |

| Mazandaran | 8 | 1678 | 95.77 | < 0.001 | 23.5 to 48.2 | 34.8 | |

| Isfahan | 4 | 1600 | 92.48 | < 0.001 | 16.5 to 35 | 24.6 | |

| Golestan | 1 | 89 | 0 | – | 2.3 to 12.8 | 5.6 | |

| Kerman | 1 | 83 | 0 | – | 20.3 to 39.6 | 29 | |

| Kermanshah | 3 | 84 | 0 | – | 7.4 to 22.1 | 13.1 | |

| Razavi Khorasan | 3 | 219 | 67.89 | 0.044 | 12.4 to 34.2 | 21.3 | |

| Guilan | 1 | 310 | 0 | – | 16.5 to 25.5 | 20.9 | |

| Kurdistan | 1 | 47 | 0 | – | 4.5 to 23.1 | 10.6 | |

| Semnan | 1 | 270 | 0 | – | 0.4 to 3.4 | 1.1 | |

| Fars | 3 | 2010 | 99.09 | < 0.001 | 4 to 50.8 | 17.2 | |

| East Azarbaijan | 2 | 549 | 91.32 | 0.001 | 4.6 to 25 | 11.3 | |

| Tehran | 14 | 10,407 | 91.32 | < 0.001 | 25.1 to 31 | 28 | |

| Zanjan | 1 | 78 | 0 | – | 0.2 to 8.5 | 1.2 | |

| Test for subgroup differences: Q = 97.59, df(Q) = 13, P < 0.001 | |||||||

| Quality | Medium | 20 | 7760 | 63.68 | < 0.001 | 16.6 to 28.0 | 23.5 |

| High | 22 | 10,240 | 96.65 | < 0.001 | 19.1 to 28.7 | 23.5 | |

| Test for subgroup differences: Q = 0, df(Q) = 1, P = 0.995 | |||||||

aNumber

bConfidence interval

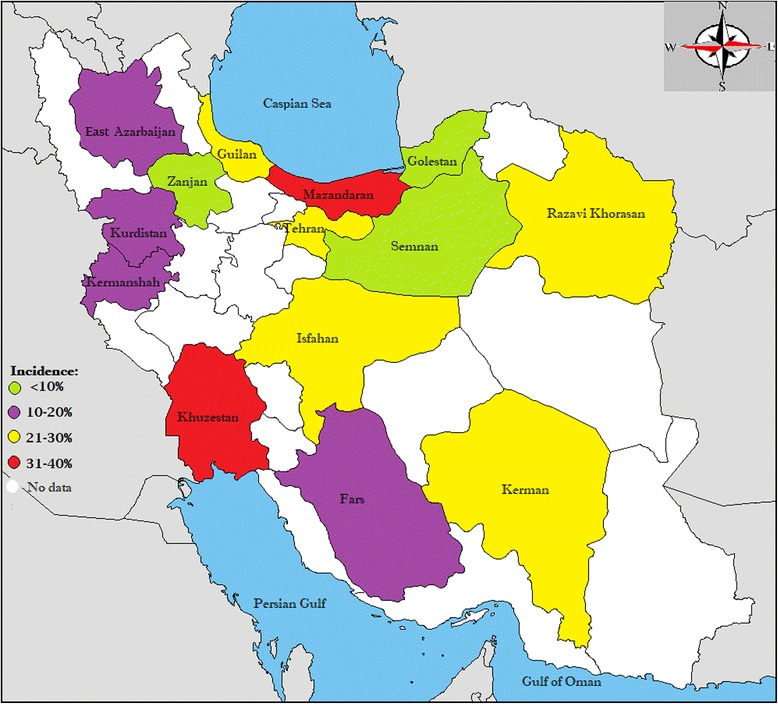

Subgroup analysis of ROP prevalence based on province

Table 2 and Fig. 4 show the prevalence of ROP based on Iran’s provinces. The highest prevalence was in provinces of Mazandaran (34.8%) and Khuzestan (32%), and the lowest prevalence was in the provinces of Semnan (1.1%) and Zanjan (1.2%).

Fig. 4.

Geographical distribution of retinopathy of prematurity in Iran

Subgroup analysis of ROP prevalence based on the quality of studies

The prevalence of ROP in moderate and high-quality studies was 23.5% (95% CI: 16.6–28.0) and 23.5% (95% CI: 19.1–28.7), respectively, and the difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.995) (Table 2).

The prevalence of ROP based on gender

The prevalence of ROP in girls and boys premature infants was 18.3% (95% CI: 12.8–25.4) and 18.9% (95% CI: 11.9–28.5), respectively. Their difference was not statistically significant (P = 0.501) (Table 2).

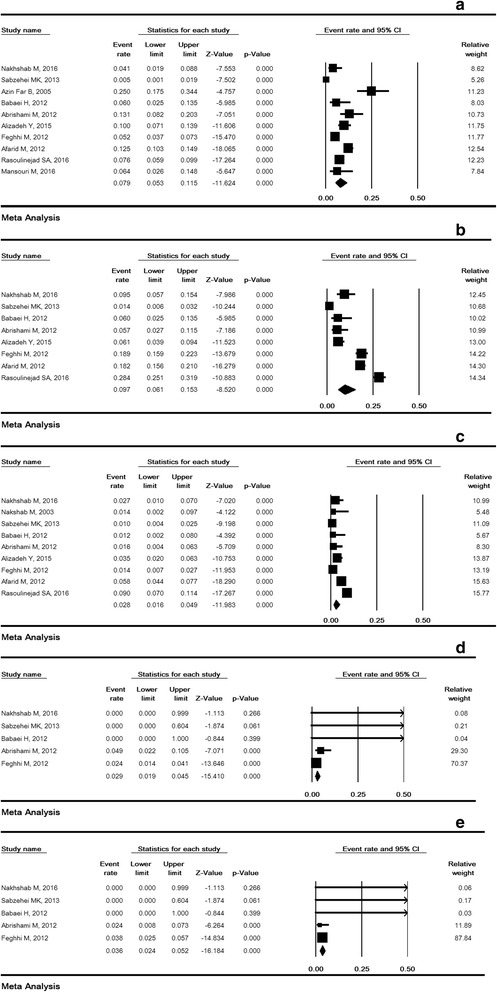

The prevalence of ROP based on stage

The prevalence of stages 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5 were reported in 10, eight, nine, five, and five studies, respectively. Fig. 5 shows the prevalence of ROP at different stages. The prevalence of stages 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5 was 7.9% (95% CI: 5.3–11.5), 9.7% (95% CI: 6.1–15.3), 2.8% (95% CI: 1.6–4.9), 2.9% (95% CI: 1.9–4.5), and 3.6% (95% CI: 2.4–5.2), respectively.

Fig. 5.

The prevalence of stages I (a), II (b), III (c), IV (d), V (e) retinopathy of prematurity. Random effects model

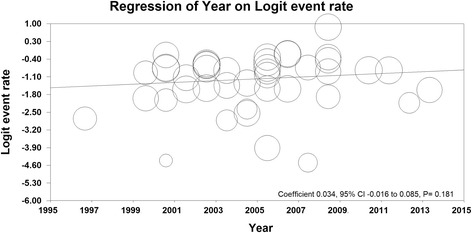

Meta-regression

Meta-regression model in Fig. 6 shows that the incidence of ROP is increasing according to the year of study, and this relationship is not statistically significant (meta-regression coefficient: 0.034, 95% CI -0.016 to 0.085, P = 0.181).

Fig. 6.

Meta-regression of ROP prevalence based on years of studies

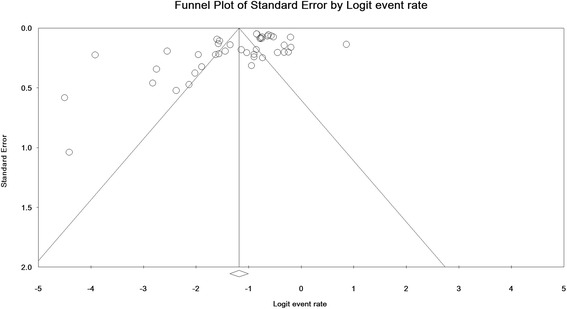

Publication bias

The significance level of publication bias in the reviewed studies was 0.003 and 0.002 according to Egger and Begg’s tests, respectively, which is shown in Fig. 7.

Fig. 7.

Publication bias in the studies

ROP risk factors

The meta-analysis results of evaluating the risk factors of ROP are shown in Table 3. ROP risk factors include certain variables such as continuous positive pressure (CPAP) (P = 0.023), the prevalence of blood transfusion (P = 0.001), septicemia (P = 0.021), weight < 1000 g (P < 0.001), weight < 1500 g (P < 0.0001), frequency of phototherapy (P < 0.0001), the frequency of oxygen therapy (P = 0.049), apnea (P = 00.2), intraventricular hemorrhage (IVH) (P = 0.005), respiratory distress syndrome (RDS) (P = 0.036), gestational age (GA) ≤ 28 W(week) (P < 0.001), GA ≤32 W (P < 0.001), saturation over 50% (P < 0.001), mean GA (P < 0.001), mean weight (P < 0.0001), oxygen therapy duration (P < 0.001) and phototherapy duration (P < 0.0001); however, preeclampsia significantly decreases the prevalence of ROP (P = 0.014).

Table 3.

Risk factor for retinopathy of prematurity in Iran

| Variables | Studies(Na) | Sample (N) | Heterogeneity | OR (95%CIb) | P-Value | Model in Meta-analysis | ||

| Case | Control | I2 | P-Value | |||||

| Twin birth | 4 | 804 | 1868 | 46.97 | 0.129 | 1.62 (0.94 to 2.81) | 0.081 | Randomc |

| Mechanical ventilation | 6 | 1131 | 2493 | 73.35 | 0.002 | 1.81 (0.80 to 1.73) | 0.39 | Random |

| Continuous positive pressure ventilation | 2 | 62 | 131 | 64.11 | 0.095 | 3.97 (1.21 to 13.01) | 0.023 | Random |

| Blood transfusion (N) | 16 | 1820 | 4167 | 91.34 | < 0.001 | 2.38 (1.43 to 3.94) | 0.001 | Random |

| Septicemia | 11 | 1327 | 2965 | 80.75 | < 0.001 | 1.96 (1.10 to 3.48) | 0.021 | Random |

| Birth weight < 1000 g | 9 | 573 | 2093 | 59.65 | 0.011 | 4.16 (2.35 to 7.35) | < 0.001 | Random |

| Birth weight < 1500 g | 10 | 559 | 1984 | 43.34 | 0.069 | 3.74 (2.54 to 5.49) | < 0.001 | Random |

| Phototherapy (N) | 11 | 1380 | 3355 | 80.69 | < 0.001 | 1.50 (1.00 to 2.27) | 0.049 | Random |

| Oxygen therapy (N) | 14 | 726 | 3124 | 87.39 | < 0.001 | 3.06 (1.29 to 7.27) | 0.011 | Random |

| Need for resuscitation | 2 | 56 | 212 | 86.50 | 0.006 | 5.01 (0.18 to 135.71) | 0.338 | Random |

| Apnea | 3 | 114 | 492 | 72.08 | 0.028 | 4.41 (1.70 to 11.40) | 0.002 | Random |

| Congenital heart disease | 2 | 50 | 246 | 67.29 | 0.08 | 2.13 (0.10 to 45.62) | 0.626 | Random |

| Inter-ventricular hemorrhage | 11 | 1223 | 3178 | 76.36 | < 0.001 | 2.24 (1.2 to 3.95) | 0.005 | Random |

| Acidosis | 3 | 132 | 296 | 62.62 | 0.069 | 2.56 (0.81 to 8.06) | 0.106 | Random |

| Cesarean section | 4 | 375 | 830 | 47.88 | 0.124 | 1.08 (0.53 to 2.18) | 0.82 | Random |

| Preeclampsia | 2 | 108 | 237 | 0 | 0.82 | 0.12 (0.02 to 0.65) | 0.014 | Fixedd |

| Respiratory distress syndrome | 11 | 2039 | 2618 | 80.13 | < 0.001 | 1.64 (1.03 to 2.61) | 0.036 | Random |

| Saturation above 50% | 4 | 118 | 656 | 30.30 | 0.23 | 8.35 (3.14 to 22.18) | < 0.001 | Random |

| Normal Vaginal Delivery | 4 | 375 | 830 | 46.63 | 0.132 | 1.01 (0.50 to 2.02) | 0.969 | Random |

| Multiple pregnancy | 6 | 1199 | 2518 | 40.20 | 0.137 | 0.92 (0.73 to 1.16) | 0.517 | Random |

| Gestational age ≤ 28 | 6 | 551 | 1440 | 75.88 | < 0.001 | 5.20 (2.31 to 11.73) | < 0.001 | Random |

| Gestational age ≤ 32 | 9 | 689 | 1885 | 64.84 | 0.004 | 7.88 (4.62 to 13.46) | < 0.001 | Random |

| Birth weight (gr) | 7 | 1495 | 2893 | 97.30 | < 0.001 | 0.98 (0.97 to 0.99) | < 0.001 | Random |

| Gestational age (week) | 7 | 1495 | 2893 | 84.20 | < 0.001 | 0.67 (0.59 to 0.770) | < 0.001 | Random |

| Variables | Studies(Na) | Sample (N) | Heterogeneity | Mean Difference (95% CIb) | P-Value | |||

| Case | Control | I2 | P-Value | |||||

| Gestational age (weeks) | 18 | 1835 | 4126 | 94.53 | < 0.001 | 2.08(1.50 to 2.66) | < 0.001 | Random |

| Birth weight (gr) | 19 | 1782 | 4519 | 95.94 | < 0.001 | 305.39(236.09 to 374.69) | < 0.001 | Random |

| Oxygen therapy (day) | 11 | 1399 | 3214 | 96.04 | < 0.001 | −4.36(−6.09 to −2.63) | < 0.001 | Random |

| Phototherapy (days) | 4 | 78 | 308 | 83.80 | < 0.001 | −2.08(−3.81 to −0.35) | < 0.001 | Random |

| Apgar score in the first minute | 3 | 174 | 216 | 63.30 | 0.66 | 1.07(0.45 to 1.68) | 0.001 | Random |

| Apgar score | 3 | 64 | 272 | 76.34 | 0.015 | 0.43(−0.25 to −1.13) | 0.21 | Random |

| Mechanical ventilation (days) | 2 | 114 | 154 | 88.81 | 0.003 | −4.53(−9.17 to 0.10) | 0.55 | Random |

| Bilirubin (mg/di) | 3 | 54 | 186 | 7.70 | 0.33 | −0.27(−1.40 to 0.86) | 0.63 | Random |

| Blood transfusion (duration) | 2 | 98 | 151 | 0 | 0.98 | −0.69(−0.96 to − 0.42) | < 0.001 | Fixed |

| clinical risk index for babies | 2 | 161 | 250 | 58.84 | 0.11 | −0.62(− 1.40 to 0.16) | 0.11 | Random |

aNumber

bConfidence interval

cRandom effects model

dFixed effects model

Discussion

The present study is the first systematic and meta-analytic review on the prevalence and risk factors of ROP in Iran. The results of this meta-analysis showed that the prevalence of ROP in 18,000 Iranian premature infants was 23.5%, and the prevalence for stages 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5 was 7.9%, 9.7%, 2.8%, 2.9% and 3.6%, respectively. In this study, the level of heterogeneity was high for ROP studies (95.6%). The results of the subgroup analysis showed that geographic regions and the provinces could be a cause of high heterogeneity. However, this difference can be a reflection of studies conducted on different samples based on the GA or neonatal weight.

ROP is still a major cause of potentially preventable blindness around the world [23]. According to guidelines published by the American Academy of Ophthalmology, the American Academy of Children, and the American Association for Ophthalmology for Children and Strabismus for ROP screening, infants weighing less than 1500 g or GA ≤ 30 weeks, and infants weighing between 1500 and 2000 g or GA > 30 weeks with an unstable clinical course should receive dilated ophthalmoscopy examinations for ROP [24].

The prevalence of ROP in various studies is mainly due to differences in mean GA and birth weight of infants in each study. Based on GA, the prevalence of ROP significantly decreases from 77.9% in GA 24–25 to 1.1% in GA 30–31, which indicates the direct role of GA in ROP incidence. These results are completely consistent with the data published in other literature [25–31]. Moreover, in a meta-analysis study in Iran, the prevalence of prematurity was reported to be 9.2% (95% CI: 7.6–10.7) [32]. Therefore, the high prevalence of ROP in Iran (23.5%) can be explained by the high prevalence of prematurity.

In a study by Tabarez-Carvajal et al. among 3018 premature infants, the incidence of stages 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 was reported to be 8.34%, 8.78%, 1.9%, 0.03%, and 0.30%, respectively [33]. In another study by Abdel HA et al., the prevalence of ROP stage 1 was 10.4%, stage 2 was 5.2% and stage 3 was 3.45%, and none of the infants had ROP at stages 4 or 5 [34]. But in the present study, the prevalence of ROP stages 4 and 5 was higher.

ROP is a multi-factorial disease, and in the present study, the strongest risk factor for ROP was prematurity and low birth weight. Most studies have demonstrated that prematurity and low birth weight are the strongest predictive factors of ROP, which indicates the crucial role of factors associated with the progression of the ROP disease [35–45].

After low birth weight and prematurity, exposure to oxygen for a long period and saturation over 50% were the most important risk factors for ROP in this study, which was consistent with the results of many other studies [42–47]. Due to inadequate antioxidant defense system, premature infants are not evolved to live in an oxygen-rich ectopic environment [48, 49]. Oxidative stress is the result of various organs’ exposure to free radicals of oxygen after being exposed to high concentrations of oxygen, which can lead to the progression of many pathogens such as ROP, necrotizing enterocolitis, IVH, bronchopulmonary dysplasia, and periventricular leukomalacia [50, 51].

In this study, other significant relationships with ROP were also found, including frequency and duration of blood transfusion, phototherapy, septicemia, apnea, IVH, and RDS. The comparison between the risk factors in our study and other reports is shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Risk factor for retinopathy of prematurity in other studies

| Study details | GA (weeks) | BW (gr) | Risk factors |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reyes et al., 2017. Oman [46] | < 32 | < 1500 | low BW, low GA, duration of invasive ventilation, duration of oxygen therapy, duration of nasal CPAP, late onset clinical or proven sepsis |

| Shah et al., 2005 Singapore [40] | < 32 | < 1500 | Preeclampsia, low BW, prolonged duration of ventilation, pulmonary hemorrhage and CPAP |

| Yau et al., 2016, China [45] | < 32 and > 32 | < 1500 | low GA, low BW, preeclampsia, gestational diabetes mellitus, inotrope use, postnatal hypotension, apgar score (1 min, 5 min and 10 min), respiratory distress syndrome, bronchopulmonary dysplasia, invasive mechanical ventilation, surfactant use, oxygen supplement, patent ductus arteriosus, thrombocytopenia, blood transfusion, anemia, NSAID use, sepsis |

| Abdel HA et al., 2012, Egypt [34] | < 32 and > 32 | < 1500 and > 1500 | low GA, oxygen therapy, frequency of blood transfusions and sepsis |

| Chen et al., 2011, USA [41] | < 30 | < 1500 | low GA, Sepsis, oxygen exposure |

| Hadi and Hamdy, 2013, Egypt [37] | < 32 | < 1250 | low GA, low BW, Ventilation, blood transfusions, sepsis, Patent ductus arteriosus, IVH |

| Nair et al., 2001, Oman [36] | < 32 | < 1500 | low BW, Low GA, TPN |

BW Birth weight, GA Gestational age, PDA Patent ductus arteriosus, CPAP Continuous positive pressure ventilation, IVH Intraventricular hemorrhage, TPN Total parenteral nutrition

Conclusion

Finally, it can be concluded that the present systematic review and meta-analysis summarizes the results of previous studies and provides a comprehensive view of ROP in Iran. Although the prevalence of ROP in Iran is similar to some developing countries, it is much higher than some other countries. Therefore, this fact highlights the importance of preventing and treating ROP and its following complications. To achieve a more favorable level and reduce the prevalence in the coming years, screening and close monitoring by experienced ophthalmologists are essential to diagnose and treat the common complications of prematurity and prevent visual impairment or blindness.

Acknowledgements

We thanks Behbahan University of Medical Sciences for the financial support.

Funding

Behbahan University of Medical Sciences.

Availability of data and materials

Because this article is a meta-analysis also the data extracted from the relevant articles in Iran.

Abbreviations

- CI

Confidence interval

- GA

Gestational age

- IVH

Intraventricular hemorrhage

- PRISMA

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Protocols

- RDS

Respiratory Distress Syndrome

- ROP

Retinopathy of prematurity

- W

Week

Authors’ contributions

MA was involved in study concept and design, acquisition of data, search, quality evaluation of studies, drafting of the manuscript, analysis and interpretation of data, critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content, approval of final version, and accountable for accuracy and integrity of the work. ZJ was involved in search, interpretation of data, acquisition of data, quality evaluation of studies, drafting of the manuscript, and approval of final version. ShR was involved in search, analysis and interpretation of data, quality evaluation of studies, drafting of the manuscript, and approval of final version. GhB was involved in study concept and design, acquisition of data, quality evaluation of studies, drafting of the manuscript, critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content, approval of final version, administrative, technical or material support and accountable for accuracy and integrity of the work. ADF was involved in search critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content, and approval of final version.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Milad Azami, Email: MiladAzami@medilam.ac.ir.

Zahra Jaafari, Email: zahra.jaafari24@gmail.com.

Shoboo Rahmati, Email: shoboorahmati2014@gmail.com.

Afsar Dastjani Farahani, Email: Ropinfo@tums.ac.ir.

Gholamreza Badfar, Email: Gh_badfar@yahoo.com.

References

- 1.Zin A, Gole GA. Retinopathy of prematurity-incidence today. Clin Perinatol. 2013;40(2):185–200. doi: 10.1016/j.clp.2013.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gergely K, Gerinec A. Retinopathy of prematurity--epidemics, incidence, prevalence, blindness. Bratisl Lek Listy. 2009;111(9):514–517. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zin A. R etinopathyof P re maturity-I ncidence to day. 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kliegman RM, Behrman RE, Jenson HB, et al. Nelson textbook of pediatrics E-book: Elsevier health sciences. 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wilson CM, Ells AL, Fielder AR. The challenge of screening for retinopathy of prematurity. Clin Perinatol. 2013;40(2):241–259. doi: 10.1016/j.clp.2013.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gibson DL, Sheps SB, Schechter MT, et al. Retinopathy of prematurity: a new epidemic? Pediatrics. 1989;83:486–492. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Augsburger JJBN. Yanoff M, Duker JS, editors. Ophtalmology. St. Louis, MO: Mosby 2004. p. 1097–102.

- 8.Senthil MP, Salowi MA, Bujang MA, et al. Risk factors and prediction models for retinopathy of prematurity. Malays J Med Sci. 2015;22(5):57. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.GEBEŞÇE A, USLU H, KELEŞ E, et al. Retinopathy of prematurity: incidence, risk factors, and evaluation of screening criteria. Turk J Med Sci. 2016;46(2):315–320. doi: 10.3906/sag-1407-127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Edy Siswanto J, Sauer PJ. Retinopathy of prematurity in Indonesia: Incidence and risk factors. J Neonatal Perinatal Med. 2017;10(1):85-90. 10.3233/NPM-915142. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Naderian GIR, Mohammadizadeh M, Najafabadi FBZ, et al. The frequency of retinopathy of prematurity in premature infants referred to an ophthalmology Clinic in Isfahan. J Isfahan Med Sch. 29(128):126–30.

- 12.Gharebagh M, Sadeghi K, Zarghami N, Mostafidi H. Evaluation of vascular endothelial growth factor, leptin and insulin-like growth factor in precocious retinopathy. Urmia Med J. 2012;23(2):183–90.

- 13.Gharehbaghi MM, Peirovifar A, Sadeghi K. Plasma leptin concentrations in preterm infants with retinopathy of prematurity (ROP). Iran J Neonatol. 2012;3(1):12–6.

- 14.Nakhshab MAA, Dargahi S, Farhadi R, et al. The incidence rate of retinopathy of prematurity and related risk factors: a study on premature neonates hospitalized in two hospitals in sari, Iran, 2014-2015. J Kerman Univ Med Sci. 2016;23(3):296–307. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Badfar G, Shohani M, Nasirkandy MP, et al. Epidemiology of hepatitis B in pregnant Iranian women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Virol. 2018;163(2):319-330. 10.1007/s00705-017-3551-6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, PRISMA Group Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sayehmiri K, Tavan H, Sayehmiri F, et al. Prevalence of epilepsy in Iran: a meta-analysis and systematic review. Iran J Child Neurol. 2014;8(4):9–17. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wells GA, Shea B, O'Connell D, Peterson J, Welch V, Losos M, et al. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analysis. 2011. Available: www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp. Accessed 25 Nov 2012.

- 19.Higgins JP, Green S. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. Hoboken: Wiley; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ades A, Lu G, Higgins J. The interpretation of random-effects meta-analysis in decision models. Med Decis Mak. 2005;25(6):646–654. doi: 10.1177/0272989X05282643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Borenstein M, Hedges LV, Higgins J, et al. A basic introduction to fixed-effect and random-effects models for meta-analysis. Res Synth Methods. 2010;1(2):97–111. doi: 10.1002/jrsm.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Borenstein M, Hedges LV, Higgins J, Rothstein HR. Meta-Regression. Introduction to meta-analysis. 2009. pp. 187–203. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Clemett R, Darlow B. Results of screening low-birth-weight infants for retinopathy of prematurity. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 1999;10:155–163. doi: 10.1097/00055735-199906000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ophthalmology AAoPSo Screening examination of premature infants for retinopathy of prematurity. Pediatrics. 2013;131(1):189–195. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-2996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Isaza G, Arora S. Incidence and severity of retinopathy of prematurity in extremely premature infants. Can J Opthalmol. 2012;47:296–300. doi: 10.1016/j.jcjo.2012.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hwang JH, Lee EH, Kim EA. Retinopathy of prematurity among very-low-birth-weight infants in Korea: incidence, treatment, and risk factors. J Korean Med Sci. 2015;30(Suppl 1):S88S94. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2015.30.S1.S88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gunn DJ, Cartwright DW, Gole GA. Incidence of retinopathy of prematurity in extremely premature infants over an 18-year period. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2012;40:93–99. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-9071.2011.02724.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cerman E, Balci SY, Yenice OS, et al. Screening for retinopathy of prematurity in a tertiary ophthalmology Department in Turkey: incidence, outcomes, and risk factors. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers Imaging Retina. 2014;45:550–555. doi: 10.3928/23258160-20141118-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mitsiakos G, Papageorgiou A. Incidence and factors predisposing to retinopathy of prematurity in inborn infants less than 32 weeks of gestation. Hippokratia. 2016;20(2):121–126. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bas AY, Koc E, Dilmen U; ROP Neonatal Study Group. Incidence and severity of retinopathy of prematurity in Turkey. Br J Ophthalmol. 2015;99(10):1311-4. 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2014-306286. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.Group ETfRoPC. The incidence and course of retinopathy of prematurity: findings from the early treatment for retinopathy of prematurity study. Pediatrics 2005;116(1):15–23. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 32.Vakilian K, Ranjbaran M, Khorsandi M, et al. Prevalence of preterm labor in Iran: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Reprod Biomed. 2015;13(12):743–748. doi: 10.29252/ijrm.13.12.743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tabarez-Carvajal AC, Montes-Cantillo M, Unkrich KH, et al. Retinopathy of prematurity: screening and treatment in Costa Rica. Br J Ophthalmol. 2017;101(12):1709–1713. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2016-310005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Abdel HA, Mohamed GB, Othman MF. Retinopathy of prematurity: a study of incidence and risk factors in NICU of al-Minya University Hospital in Egypt. J Clin Neonatol. 2012;1(2):76–81. doi: 10.4103/2249-4847.96755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bassiouny MR. Risk factors associated with retinopathy of prematurity: a study from Oman. J Trop Pediatr. 1996;42:355–358. doi: 10.1093/tropej/42.6.355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nair PM, Ganesh A, Mitra S, et al. Retinopathy of prematurity in VLBW and extreme LBW babies. Indian J Pediatr. 2003;70:303–306. doi: 10.1007/BF02723585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hadi AM, Hamdy IS. Correlation between risk factors during the neonatal period and appearance of retinopathy of prematurity in preterm infants in neonatal intensive care units in Alexandria, Egypt. Clin Ophthalmol. 2013;7:831–837. doi: 10.2147/OPTH.S40136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ratra D, Akhundova L, Das MK. Retinopathy of prematurity like retinopathy in full-term infants. Oman J Ophthalmol. 2017;10(3):167-172. 10.4103/ojo.OJO_141_2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 39.Sahin A, Sahin M, Türkcü FM, et al. Incidence of retinopathy of prematurity in extremely premature infants. ISRN Pediatr. 2014;2014:134347. doi: 10.1155/2014/134347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shah VA, Yeo CL, Ling YL, et al. Incidence, risk factors of retinopathy of prematurity among very low birth weight infants in Singapore. Ann Acad Med Singap. 2005;34:169–178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chen M, Citil A, McCabe F, et al. Infection, oxygen, and immaturity: interacting risk factors for retinopathy of prematurity. Neonatology. 2011;99:125–132. doi: 10.1159/000312821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Darlow BA, Hutchinson JL, Henderson-Smart DJ, et al. Prenatal risk factors for severe retinopathy of prematurity among very preterm infants of the Australian and New Zealand neonatal network. Pediatrics. 2005;115:990–996. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-1309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Badriah C, Amir I, Elvioza SR, et al. Prevalence and 325 risk factors of retinopathy of prematurity. Paediatr Indones. 2012;52:138–144. doi: 10.14238/pi52.3.2012.138-44. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rizalya D, Rudolf T, Rohsiswatmo R. Screening for 328 retinopathy of prematurity in hospital with limited facil- 329 ities. Sari Pediatri. 2012;14:185–190. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yau GS, Lee JW, Tam VT, et al. Incidence and risk factors of retinopathy of prematurity from 2 neonatal intensive care units in a Hong Kong Chinese population. Asia Pac J Ophthalmol. 2016;5(3):185–191. doi: 10.1097/APO.0000000000000167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Reyes ZS, Al-Mulaabed SW, Bataclan F, et al. Retinopathy of prematurity: revisiting incidence and risk factors from Oman compared to other countries. Oman J Ophthalmol. 2017;10(1):26–32. doi: 10.4103/ojo.OJO_234_2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yu VY, Upadhyay A. Neonatal management of the growth-restricted infant. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med. 2004;9:403–409. doi: 10.1016/j.siny.2004.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Weinberger B, Laskin DL, Heck DE, et al. Oxygen toxicity in premature infants. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2002;181:60–67. doi: 10.1006/taap.2002.9387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hardy P, Beauchamp M, Sennlaub F, et al. New insights into the retinal circulation: inflammatory lipid mediators in ischemic retinopathy. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 2005;72:301–325. doi: 10.1016/j.plefa.2005.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.O'Donovan DJ, Fernandes CJ. Free radicals and diseases in premature infants. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2004;6:169–176. doi: 10.1089/152308604771978471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yoon HS. Neonatal innate immunity and toll-like receptor. Korean J Pediatr. 2010;53:985–988. doi: 10.3345/kjp.2010.53.12.985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Naderian G, Parvaresh M, Rismanchiyan A, et al. Refractive errors after laser therapy for retinopathy of prematurity. Int J Ophthalmol. 2009;15(1):13–18. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hosseini H, Farvardin M, Attarzadeh A, et al. Advanced retinopathy of prematurity at Poostchi ROP clinic, Shiraz. Bina J Ophthalmol 2009; 15(1):19–25.

- 54.Karkhaneh RER, Ghojehzadeh L, Kadivar M, et al. Incidence and risk factors of retinopathy of prematurity. Bina J Ophthalmol. 2005;11(1):81–90. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nadeian GMH, Hadipour M, Sajjadi H. Prevalence and rsskfactor for retinopathy of prematuority in isfahan. Bina J Ophthalmol. 2010;15(3):208–213. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mansouri MRKM, Karkhaneh R, Riazi Esfahani M, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of retinopathy of prematurity in very low birth weight or low gestational age infants. Bina J Ophthalmol. 2007;12(4):428–434. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Nakhshab MBG, Amiri A, Ashaghi M. Prevalence of preterm infant retinopathy in neonatal intensive care unit Buali Sari Hospital. J Mazandaran Univ Med Sci. 2003;13(39):63–70.

- 58.Daraie G, Nooripoor S, Ashrafi AM, et al. Incidence of retinopathy of prematurity and some related factors in premature infants born at amir–al-momenin hospital in Semnan. Iran Koomesh. 2016;17(2):297–303. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Fayazi AHM, Fayzollazade M, GHolzar A, et al. Prevalence of retinopathy in preterm infants admitted to neonatal intensive care unit of Alzahra hospital in Tabriz. J Tabriz Univ Med Sci. 2009;30(4):63–6.

- 60.Sadeghi KHA, Hashemi F, Haydarzade M, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of retinopathy in preterm infants. J Tabriz Univ Med Sc. 2008;30(2):73–77. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ebrahimiadib N, Roohipour R, Karkhaneh R, et al. Internet-based versus conventional referral system for retinopathy of prematurity screening in Iran. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2016;23(5):292–297. doi: 10.3109/09286586.2015.1136653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ghaseminejad A, Niknafs P. Distribution of retinopathy of prematurity and its risk factors. Iran J Pediatr. 2011;21(2):209. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Khatami SF, Yousefi A, Bayat GF, et al. Retinopathy of prematurity among 1000-2000 gram birth weight newborn infants. Iran J Pediatr. 2008;18(2):137–142. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sabzehei MK, Afjeh SA, Farahani AD, et al. Retinopathy of prematurity: incidence, risk factors, and outcome. Arch Iran Med. 2013;16(9):507. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Saeidi R, Hashemzadeh A, Ahmadi S, et al. Prevalence and predisposing factors of retinopathy of prematurity in very low-birth-weight infants discharged from NICU. Iran J Pediatr. 2009;19(1):59–63. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Azinfar MAM, Pasha Z, Amad M. Prevalence of premature newborns discharged from NICU and infants in Shafizadeh Ami Children's hospital [dissertation]. Babol, Iran; Babol Univ Med; 2005.

- 67.Karkhanehyousefi NRA, Mekaniki A. Prevalence of retinopathy in immature newborns referred to eye Clinic of Shahid Beheshti Hospital in Babol [dissertation]. Babol, Iran; Babol Univ Med; 2009.

- 68.Ebrahimzade MKR, Esfahani M, Kadpour M, et al. The prevalence of retinopathy in preterm infants in preterm infants referred to Farabi hospital from the beginning of the year 2002 to the beginning of 2008 and the evaluation of short-term laser therapy results [dissertation]. Tehran: Islamic Azad Univ Med; 2009.

- 69.Mirzaee SA, Mohagheghi P. Determine the prevalence of retinopathy (ROP) in infants admitted to the NICU department of Milad Hospital [dissertation]. Tehran: Islamic Azad Univ Med; 2010.

- 70.Mousavi SZ, Karkhaneh R, Riazi-Esfahani M, et al. Retinopathy of prematurity in infants with late retinal examination. J Ophthalmic Vis Res. 2009;4(1):24. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Foladinezhad MMM, GHarib M, SHishari F, Soltani M. Frequency, severity and some risk factors of retinopathy in premature infants of Taleghani Hospital in Gorgan. J Gorgan Univ Med Sc. 2009;11(2):51–4.

- 72.Mousavi SZKR, Riazi-Esfahani M, Mansouri MR, et al. Incidence, severity and risk factors for retinopathy ofPrematurity in premature infants with late retinal examination. Bina J Ophthalmol. 2008;13(4):412–417. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Sadeghzadeh M, Khoshnevisasl P, Parvaneh M, et al. Early and late outcome of premature newborns with history of neonatal intensive care units admission at 6 years old in Zanjan. Northwestern Iran Iran J Child Neurol. 2016;10(2):67. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Bayat-Mokhtari M, Pishva N, Attarzadeh A, et al. Incidence and risk factors of retinopathy of prematurity among preterm infants in shiraz/Iran. Iran J Pediatr. 2010;20(3):303. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Karkhaneh R, Shokravi N. Assessment of retinopathy of prematurity among 150 premature neonates in Farabi eye hospital. Acta Med Iran. 2001;39(1):35–38. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Babaei H, Ansari MR, Alipour AA, et al. Incidence and risk factors for retinopathy of prematurity in very low birth weight infants in Kermanshah. Iran World Appl Sci J. 2012;18(5):600–604. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Abrishami M, Maemori G-A, Boskabadi H, et al. Incidence and risk factors of retinopathy of prematurity in Mashhad. Northeast Iran Red Crescent Med J. 2013;15(3):229. doi: 10.5812/ircmj.4513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Riazi-Esfahani M, Alizadeh Y, Karkhaneh R, et al. Retinopathy of prematurity: single versus multiple-birth pregnancies. J Ophthalmic Vis Res. 2008;3(1):47. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Alizadeh Y, Zarkesh M, Moghadam RS, et al. Incidence and risk factors for retinopathy of prematurity in north of Iran. J Ophthalmic Vis Res. 2015;10(4):424. doi: 10.4103/2008-322X.176907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Mousavi SZ, Karkhaneh R, Roohipoor R, et al. Screening for retinopathy of prematurity: the role of educating the parents. J Ophthalmol. 2010;22(2):13–18. [Google Scholar]

- 81.MousavibS Zb EM, Roohipoor R, Jabbarvand M, et al. Characteristics of advanced stages of retinopathy of prematurity. J Ophthalmol. 2010;22(2):19–24. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Feghhi M, Altayeb SMH, Haghi F, et al. Incidence of retinopathy of prematurity and risk factors in the south-western region of Iran. Middle East Afr J Ophthalmol. 2012;19(1):101. doi: 10.4103/0974-9233.92124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Afarid M, Hosseini H, Abtahi B. Screening for retinopathy of prematurity in south of Iran. Middle East Afr J Ophthalmol. 2012;19(3):277. doi: 10.4103/0974-9233.97922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Ahmadpour-kacho M, Zahed Pasha Y, Rasoulinejad SA, et al. Correlation between retinopathy of prematurity and clinical risk index for babies score. J Tehran Univ Med S. 2014;72(6):404–411. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Ahmadpour-Kacho M, Jashni Motlagh A, Rasoulinejad SA, et al. Correlation between hyperglycemia and retinopathy of prematurity. Pediatr Int. 2014;56(5):726–730. doi: 10.1111/ped.12371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Rasoulinejad SA, Montazeri M. Retinopathy of prematurity in neonates and its risk factors: a seven year study in northern iran. Open Ophthalmol J. 2016;10:17. doi: 10.2174/1874364101610010017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Karkhaneh R, Mousavi S-Z, Riazi-Esfahani M, et al. Incidence and risk factors of retinopathy of prematurity in a tertiary eye hospital in Tehran. Br J Ophthalmol. 2008;92(11):1446–1449. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2008.145136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Khalesi N, Shariat M, Fallahi M, et al. Evaluation of risk factors for retinopathy in preterm infant: a case-control study in a referral hospital in Iran. Minerva Pediatr. 2015;67(3):231–237. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Ebrahim M, Ahmad RS, Mohammad M. Incidence and risk factors of retinopathy of prematurity in Babol. North of Iran Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2010;17(3):166–170. doi: 10.3109/09286581003734860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Roohipoor R, Karkhaneh R, Farahani A, et al. Retinopathy of prematurity screening criteria in Iran: new screening guidelines. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2016;101(4):F288–FF93. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2015-309137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Mansouri M, Hemmatpour S, Sedighiani F, et al. Factors associated with retinopathy of prematurity in hospitalized preterm infants in Sanandaj. Iran Electronic physician. 2016;8(9):2931. doi: 10.19082/2931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Because this article is a meta-analysis also the data extracted from the relevant articles in Iran.