Abstract

Ozone pollution in the Southeast US involves complex chemistry driven by emissions of anthropogenic nitrogen oxide radicals (NOx ≡ NO + NO2) and biogenic isoprene. Model estimates of surface ozone concentrations tend to be biased high in the region and this is of concern for designing effective emission control strategies to meet air quality standards. We use detailed chemical observations from the SEAC4RS aircraft campaign in August and September 2013, interpreted with the GEOS-Chem chemical transport model at 0.25°×0.3125° horizontal resolution, to better understand the factors controlling surface ozone in the Southeast US. We find that the National Emission Inventory (NEI) for NOx from the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) is too high. This finding is based on SEAC4RS observations of NOx and its oxidation products, surface network observations of nitrate wet deposition fluxes, and OMI satellite observations of tropospheric NO2 columns. Our results indicate that NEI NOx emissions from mobile and industrial sources must be reduced by 30–60%, dependent on the assumption of the contribution by soil NOx emissions. Upper tropospheric NO2 from lightning makes a large contribution to satellite observations of tropospheric NO2 that must be accounted for when using these data to estimate surface NOx emissions. We find that only half of isoprene oxidation proceeds by the high-NOx pathway to produce ozone; this fraction is only moderately sensitive to changes in NOx emissions because isoprene and NOx emissions are spatially segregated. GEOS-Chem with reduced NOx emissions provides an unbiased simulation of ozone observations from the aircraft, and reproduces the observed ozone production efficiency in the boundary layer as derived from a regression of ozone and NOx oxidation products. However, the model is still biased high by 8±13 ppb relative to observed surface ozone in the Southeast US. Ozonesondes launched during midday hours show a 7 ppb ozone decrease from 1.5 km to the surface that GEOS-Chem does not capture. This bias may reflect a combination of excessive vertical mixing and net ozone production in the model boundary layer.

1 Introduction

Ozone in surface air is harmful to human health and vegetation. Ozone is produced when volatile organic compounds (VOCs) and carbon monoxide (CO) are photochemically oxidized in the presence of nitrogen oxide radicals (NOx ≡ NO+NO2). The mechanism for producing ozone is complicated, involving hundreds of chemical species interacting with transport on all scales. In October 2015, the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) set a new National Ambient Air Quality Standard (NAAQS) for surface ozone as a maximum daily 8-h average (MDA8) of 0.070 ppm not to be exceeded more than three times per year. This is the latest in a succession of gradual tightening of the NAAQS from 0.12 ppm (1-h average) to 0.08 ppm in 1997, and to 0.075 ppm in 2008, responding to accumulating evidence that ozone is detrimental to public health even at low concentrations (EPA, 2013). Chemical transport models (CTMs) tend to significantly overestimate surface ozone in the Southeast US (Lin et al., 2008; Fiore et al., 2009; Reidmiller et al., 2009; Brown-Steiner et al., 2015; Canty et al., 2015), and this is an issue for the design of pollution control strategies (McDonald-Buller et al., 2011). Here we examine the causes of this overestimate by using the GEOS-Chem CTM to simulate NASA SEAC4RS aircraft observations of ozone and its precursors over the region in August–September 2013 (Toon et al., 2016), together with additional observations from surface networks and satellite.

A number of explanations have been proposed for the ozone model overestimates in the Southeast US. Fiore et al. (2003) suggested excessive modeled ozone inflow from the Gulf of Mexico. Lin et al. (2008) proposed that the ozone dry deposition velocity could be underestimated. McDonald-Buller et al. (2011) pointed out the potential role of halogen chemistry as a sink of ozone. Isoprene emitted from vegetation is the principal VOC precursor of ozone in the Southeast US in summer, and Fiore et al. (2005) found that uncertainties in isoprene emissions and in the loss of NOx from formation of isoprene nitrates could also affect the ozone simulation. Horowitz et al. (2007) found a large sensitivity of ozone to the fate of isoprene nitrates and the extent to which they release NOx when oxidized. Squire et al. (2015) found that the choice of isoprene oxidation mechanism can alter both the sign and magnitude of the response of ozone to isoprene and NOx emissions.

The SEAC4RS aircraft campaign in August–September 2013 provides an outstanding opportunity to improve our understanding of ozone chemistry over the Southeast US. The SEAC4RS DC-8 aircraft hosted an unprecedented chemical payload including isoprene and its oxidation products, NOx and its oxidation products, and ozone. The flights featured extensive boundary layer mapping of the Southeast as well as vertical profiling to the free troposphere (Toon et al., 2016). We use the GEOS-Chem global CTM with high horizontal resolution over North America (0.25°×0.3125°) to simulate and interpret the SEAC4RS observations. We integrate into our analysis additional Southeast US observations during the summer of 2013 including from the NOMADSS aircraft campaign, the SOAS surface site in Alabama, the SEACIONS ozonesonde network, the CASTNET ozone network, the NADP nitrate wet deposition network, and NO2 satellite data from the OMI instrument. Several companion papers apply GEOS-Chem to simulate other aspects of SEAC4RS and concurrent data for the Southeast US including aerosol sources and optical depth (Kim et al., 2015), isoprene organic aerosol (Marais et al., 2016), organic nitrates (Fisher et al., 2016), formaldehyde and its relation to satellite observations (Zhu et al., 2016), and sensitivity to model resolution (Yu et al., 2016).

2 GEOS-Chem Model Description

We use the GEOS-Chem global 3-D CTM (Bey et al., 2001) in version 9.02 (www.geos-chem.org) with modifications described below. GEOS-Chem is driven with assimilated meteorological data from the Goddard Earth Observing System (GEOS-5.11.0) of the NASA Global Modeling and Assimilation Office (GMAO). The GEOS-5.11.0 data have a native horizontal resolution of 0.25° latitude by 0.3125° longitude and a temporal resolution of 3 h (1 h for surface variables and mixing depths). We use a nested version of GEOS-Chem (Chen et al., 2009) with native 0.25° × 0.3125° horizontal resolution over North America and adjacent oceans (130° − 60°W, 9.75° − 60°N) and dynamic boundary conditions from a global simulation with 4° × 5° horizontal resolution. Turbulent boundary layer mixing follows a non-local parameterization based on K-theory (Holtslag and Boville, 1993) implemented in GEOS-Chem by Lin and McElroy (2010). Daytime mixing depths are reduced by 40% from the GEOS-5.11.0 data as described by Kim et al. (2015) and Zhu et al. (2016) to match aircraft lidar observations. The GEOS-Chem nested model simulation is conducted for August–September 2013, following six months of initialization at 4° × 5° resolution.

2.1 Chemistry

The chemical mechanism in GEOS-Chem version 9.02 is described by Mao et al, (2010, 2013). We modified aerosol reactive uptake of HO2 to produce H2O2 instead of H2O in order to better match H2O2 observations in SEAC4RS. We also include a number of updates to isoprene chemistry, listed comprehensively in the Supplementary Material (Tables S1 and S2) and describe here more specifically for the low-NOx pathways. Companion papers describe the isoprene chemistry updates relevant to isoprene nitrates (Fisher et al., 2016) and organic aerosol formation (Marais et al., 2016). Oxidation of biogenic monoterpenes also is added to the GEOS-Chem mechanism (Fisher et al., 2016) but does not significantly affect ozone.

A critical issue in isoprene chemistry is the fate of the isoprene peroxy radicals (ISOPO2) produced from the oxidation of isoprene by OH (the dominant isoprene sink). When NOx is sufficiently high, ISOPO2 reacts mainly with NO to produce ozone (high-NOx pathway). At lower NOx levels, ISOPO2 may instead react with HO2 or other organic peroxy radicals, or isomerize, in which case ozone is not produced (low-NOx pathways). Here we increase the molar yield of isoprene hydroperoxide (ISOPOOH) from the ISOPO2 + HO2 reaction to 94% based on observations of the minor channels of this reaction (Liu et al., 2013). Oxidation of ISOPOOH by OH produces isoprene epoxides (IEPOX) that subsequently react with OH or are taken up by aerosol (Paulot et al., 2009b; Marais et al., 2016). We use updated rates and products from Bates et al. (2014) for the reaction of IEPOX with OH.

ISOPO2 isomerization produces hydroperoxyaldehydes (HPALDs) (Peeters et al., 2009; Crounse et al., 2011; Wolfe et al., 2012), and we explicitly include this in the GEOS-Chem mechanism. HPALDs go on to react with OH or photolyze at roughly equal rates over the Southeast US. We use the HPALD+OH reaction rate constant from Wolfe et al. (2012) and the products of the reaction from Squire et al. (2015). The HPALD photolysis rate is calculated using the absorption cross-section of MACR, with a quantum yield of 1, as recommended by Peeters and Müller (2010). The photolysis products are taken from Stavrakou et al. (2010). Self-reaction of ISOPO2 is updated following Xie et al. (2013).

A number of studies have suggested that conversion of NO2 to nitrous acid (HONO) by gas-phase or aerosol-phase pathways could provide a source of HOx radicals following HONO photolysis (Li et al., 2014; Zhou et al., 2014). This mechanism would also provide a catalytic sink for ozone when NO2 is produced by the NO + ozone reaction, viz.,

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

Observations of HONO from the NOMADSS campaign (https://www2.acom.ucar.edu/campaigns/nomadss) indicate a mean daytime HONO concentration of 10 ppt in the Southeast US boundary layer (Zhou et al., 2014), whereas the standard gas-phase mechanism in GEOS-Chem version 9.02 yields less than 1 ppt. We add the pathway proposed by Li et al. (2014), in which HONO is produced by the reaction of the HO2•H2O complex with NO2, but with a slower rate constant (kHO2•H2O+NO2 = 2×10−12 cm3 molecule−1 s−1) to match the observed ~10 ppt daytime HONO in the Southeast US boundary layer. The resulting impact on boundary layer ozone concentrations is negligible.

2.2 Dry Deposition

The GEOS-Chem dry deposition scheme uses a resistance-in-series model based on Wesely (1989) as implemented by Wang et al. (1998). Underestimate of dry deposition has been invoked as a cause for model overestimates of ozone in the eastern US (Lin et al., 2008; Walker, 2014). Daytime ozone deposition is determined principally by stomatal uptake. Here, we decrease the stomatal resistance from 200 s m−1 for both coniferous and deciduous forests (Wesely, 1989) by 20% to match summertime measurements of the ozone dry deposition velocity for a pine forest in North Carolina (Finkelstein et al., 2000) and for the Ozarks oak forest in southeast Missouri (Wolfe et al., 2015), both averaging 0.8 cm s−1 in the daytime. The mean ozone deposition velocity in GEOS-Chem along the SEAC4RS boundary layer flight tracks in the Southeast US averages0.7±0.3 cm s−1 for the daytime (9–16 local) surface layer. Deposition is suppressed in the model at night due to both stomatal closure and near-surface stratification, consistent with the Finkelstein et al. (2000) observations.

Deposition flux measurements for isoprene oxidation products at the Alabama SOAS site (http://soas2013.rutgers.edu) indicate higher deposition velocities than simulated by the standard GEOS-Chem model (Nguyen et al., 2015). The diurnal cycle of dry deposition in GEOS-Chem compares well with the observations from SOAS (Nguyen et al., 2015). As an expedient, Nguyen et al. (2015) scaled the Henry’s law coefficients for these species in GEOS-Chem to match their observed deposition velocities and we follow their approach here. Other important depositing species include HNO3 and peroxyacetyl nitrate (PAN), with mean deposition velocities along the SEAC4RS Southeast US flight tracks in daytime of 3.9 cm s−1 and 0.6 cm s−1, respectively.

2.3 Emissions

We use hourly US anthropogenic emissions from the 2011 EPA national emissions inventory (NEI11v1) at a horizontal resolution of 0.1° × 0.1° and adjusted to 2013 using national annual scaling factors (EPA, 2015). The scaling factor for NOx emissions is 0.89, for a 2013 US NEI total of 3.5 Tg N a−1. Further information on the use of the NEI11v1 in GEOS-Chem can be found here: http://wiki.seas.harvard.edu/geos-chem/index.php/EPA/NEI11_North_American_emissions/. Soil NOx emissions, including emissions from fertilizer application, are computed according to Hudman et al. (2012), with a 50% reduction in the Midwest US based on a previous comparison with OMI NO2 observations (Vinken et al., 2014). Open fire emissions are from the daily Quick Fire Emissions Database (QFED) (Darmenov and da Silva, 2014) with diurnal variability from the Western Regional Air Partnership (Air Sciences, 2005). We emit 40% of open fire NOx emissions as PAN and 20% as HNO3 to account for fast oxidation taking place in the fresh plume (Alvarado et al., 2010). Following Fischer et al. (2014), we inject 35% of fire emissions above the boundary layer, evenly between 3.5 and 5.5 km altitude. Lightning is an additional source of NOx but is mainly released in the upper troposphere, as described below.

Initial implementation of the above inventory in GEOS-Chem resulted in an 60–70% overestimate of NOx and HNO3 measured from the SEAC4RS DC-8 aircraft, and a 70% overestimate of nitrate (NO3−) wet deposition fluxes measured by the National Acid Deposition Program (NADP) across the Southeast US. Correcting this bias required a ~40% decrease in surface NOx emissions. Assuming strongly reduced soil and fertilizer NOx emissions (18% of total NOx emissions in the Southeast) and open fires (2%), also considering the large uncertainty in these emissions, would be insufficient to correct this bias. Emissions from power plant stacks are directly measured but account for only 12% of NEI NOx emissions on an annual basis (EPA, 2015). Several local studies in recent years have found that NEI NOx emissions for mobile sources may be too high by a factor of two or more (Castellanos et al, 2011; Fujita et al., 2012; Brioude et al., 2013; Anderson et al., 2014). We can achieve the required 40% decrease in total NOx emissions by reducing NEI emissions from mobile and industrial sources (all sources except power plants) by 60%, or alternatively by reducing these sources by 30% and zeroing out soil and fertilizer NOx emissions. Since it is apparent that there is some minimum contribution by soil NOx emissions we assessed the impact of the approach of reducing the NEI emissions by 60%. The spatial overlap between anthropogenic and soil NOx emissions is such that we cannot readily arbitrate between these two scenarios. Comparisons with observations will be presented in the next Section.

We constrain the lightning NOx source with satellite data as described by Murray et al. (2012). Lightning NOx is mainly released at the top of convective updrafts following Ott et al. (2010). The standard GEOS-Chem model uses higher NOx yields for mid-latitudes lightning (500 mol/flash) than for tropical (260 mol/flash) (Huntrieser et al., 2007, 2008; Hudman et al., 2007; Ott et al., 2010) with a fairly arbitrary boundary between the two at 23°N in North America and 35°N in Eurasia. Zhang et al. (2014) previously found that this leads GEOS-Chem to overestimate background ozone in the southwestern US and we find the same here for the eastern US and the Gulf of Mexico. We treat here all lightning in the 35°S–35°N band as tropical and thus remove the distinction between North America and Eurasia.

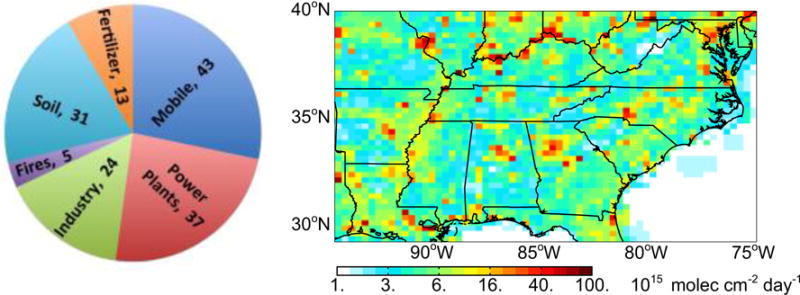

Figure 1 gives the resulting surface NOx emissions for the Southeast US for August and September 2013. With the original NEI inventory, fuel combustion accounted for 81% of total surface NOx emissions in the Southeast US (not including lightning). If the required reduction of non-power plant NEI emissions is 60%, the contribution from fuel combustion would be 68%.

Figure 1.

Surface NOx emissions in the Southeast US in GEOS-Chem for August and September 2013 including fuel combustion, soils, fertilizer use, and open fires (total emissions=153 Gg N). Anthropogenic emissions from mobile sources and industry in the National Emission Inventory (NEI11v1) for 2013 have been decreased by 60% to match atmospheric observations (see text). Lightning contributes an additional 25 Gg N to the free troposphere (not included in the Figure). The emissions are mapped on the 0.25° × 0.3125° GEOS-Chem grid. The pie chart gives the sum of August–September 2013 emissions (Gg N) over the Southeast US domain as shown on the map (94.5–75° W, 29.5–40° N).

Biogenic VOC emissions are from MEGAN v2.1, including isoprene, acetone, acetaldehyde, monoterpenes, and >C2 alkenes. We reduce MEGAN v2.1 isoprene emissions by 15% to better match SEAC4RS observations of isoprene fluxes from the Ozarks (Wolfe et al., 2015) and observed formaldehyde (Zhu et al., 2016). Yu et al. (2016) show the resulting isoprene emissions for the SEAC4RS period.

3 Overestimate of NOx emissions in the EPA NEI inventory

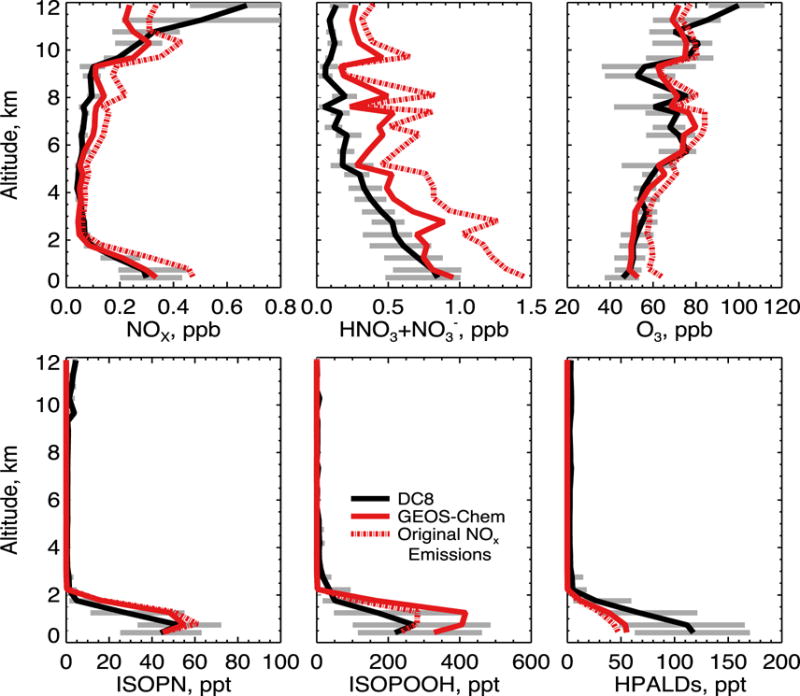

Figure 2 shows simulated and observed median vertical distributions of NOx, total inorganic nitrate (gas-phase HNO3+aerosol NO3−), and ozone concentrations along the SEAC4RS flight tracks over the Southeast US. Here and elsewhere the data exclude urban plumes as diagnosed by [NO2] > 4 ppb, open fire plumes as diagnosed by [CH3CN] > 200 ppt, and stratospheric air as diagnosed by [O3]/[CO] > 1.25 mol mol−1. These filters exclude <1%, 7%, and 6% of the data respectively. We would not expect the model to be able to capture these features even at native resolution (Yu et al., 2016).

Figure 2.

Median vertical concentration profiles of NOx, total inorganic nitrate (gas HNO3 + aerosol NO3−), ozone, isoprene nitrate (ISOPN), isoprene hydroperoxide (ISOPOOH), and hydroperoxyaldehydes (HPALD) for the SEAC4RS flights over the Southeast US (domain of Figure 1). Observations from the DC-8 aircraft are compared to GEOS-Chem model results. The dashed red line shows model results before adjustment of NOx emissions from fuel combustion and lightning (see text). The 25th and 75th percentiles of the DC-8 observations are shown as grey bars. The SEAC4RS observations have been filtered to remove open fire plumes, stratospheric air, and urban plumes as described in the text. Model results are sampled along the flight tracks at the time of flights and gridded to the model resolution. Profiles are binned to the nearest 0.5 km. The NOAA NOyO3 4-channel chemiluminescence (CL) instrument made measurements of ozone and NOy (Ryerson et al., 1998), NO (Ryerson et al., 2000) and NO2 (Pollack et al, 2010). Total inorganic nitrate was measured by the University of New Hampshire Soluble Acidic Gases and Aerosol (UNH SAGA) instrument (Dibb et al., 2003) and was mainly gas-phase HNO3 for the SEAC4RS conditions. ISOPOOH, ISOPN, and HPALDs were measured by the Caltech single mass analyzer CIMS (Crounse et al., 2006; Paulot et al., 2009a; Crounse et al., 2011).

Model results in Figure 2 are shown both with the original NOx emissions (dashed line) and with non-power plant NEI fuel emissions decreased by 60% (solid line). Decreasing emissions corrects the model bias for NOx and also largely corrects the bias for inorganic nitrate. Boundary layer ozone is overestimated by 12 ppb with the original NOx emissions but this bias disappears after decreasing the NOx emissions. Results are very similar if we decrease the non-power plant NEI fuel emissions by only 30% and zero out soil and fertilizer emissions. Thus the required decrease of NOx emissions may involve an overestimate of both anthropogenic and soil emissions.

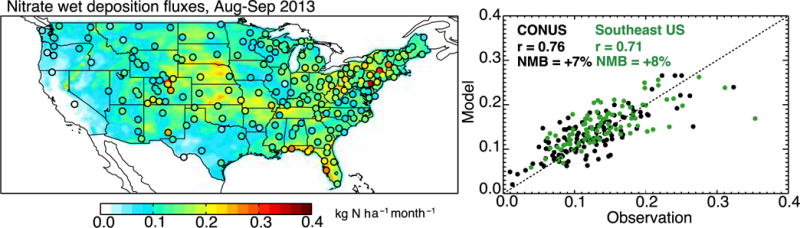

Further support for decreasing NOx emissions is offered by observed nitrate wet deposition fluxes from the NADP network (NADP, 2007). Figure 3 compares simulated and observed fluxes for the model with decreased NOx emissions. Model values have been corrected for precipitation bias following the method of Paulot et al. (2014), in which the monthly deposition flux is assumed to scale to the 0.6th power of the precipitation bias. We diagnose precipitation bias in the GEOS-5.11.0 data relative to high-resolution PRISM observations (http://prism.oregonstate.edu). For the Southeast US, the precipitation bias is −34% in August and −21% in September 2013. We see from Figure 3 that the model with decreased NOx emissions reproduces the spatial variability in the observations with only +8% bias over the Southeast US and +7% over the contiguous US. In comparison, the model with original emissions had a 63% overestimate of the nitrate wet deposition flux nationally and a 71% overestimate in the Southeast. The high deposition fluxes along the Gulf of Mexico in Figure 3, both in the model and in the observations, reflect particularly large precipitation.

Figure 3.

Nitrate wet deposition fluxes across the US in August–September 2013. Mean observations from the NADP network (circles in the left panel) are compared to model values with decreased NOx emissions (background). Also shown is a scatterplot of simulated versus observed values at individual sites for the whole contiguous US (black) and for the Southeast US (green). The correlation coefficient (r) and normalized mean bias (NMB) are shown inset, along with the 1:1 line.

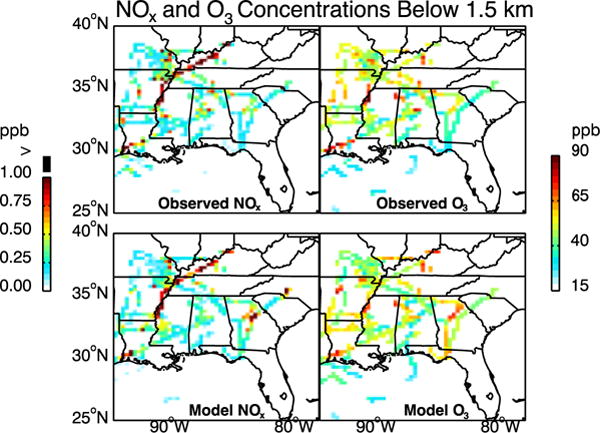

The model with decreased NOx emissions also reproduces the spatial distribution of NOx in the Southeast US boundary layer as observed in SEAC4RS. This is shown in Figure 4 with simulated and observed concentrations of NOx along the flight tracks below 1.5 km altitude. The spatial correlation coefficient is 0.71. There are no obvious spatial patterns of model bias that would point to specific source sectors as responsible for the NOx emission overestimate, beyond the blanket 30–60% decrease of non-power plant NEI emissions needed to correct the regional emission total.

Figure 4.

Ozone and NOx concentrations in the boundary layer (0–1.5km) during SEAC4RS (6 Aug to 23 Sep 2013) Observations from the aircraft and simulated values are averaged over the 0.25°×0.3125° GEOS-Chem grid. NOx above 1ppb is shown in black. The spatial correlation coefficient is 0.71 for both NOx and O3. The normalized mean bias is −11.5% for NOx and 4.5% for O3.

4 Using satellite NO2 data to verify NOx emissions: sensitivity to upper troposphere

Observations of tropospheric NO2 columns by solar backscatter from the OMI satellite instrument offer an additional constraint on NOx emissions (Duncan et al., 2014; Lu et al., 2015). We compare the tropospheric columns simulated by GEOS-Chem with the NASA operational retrieval (Level 2, v2.1) (NASA, 2012; Bucsela et al., 2013) and the Berkeley High-Resolution (BEHR) retrieval (Russell et al., 2011). The NASA retrieval has been validated to agree with surface measurements to within ± 20% (Lamsal et al., 2014). Both retrievals fit the observed backscattered solar spectra to obtain a slant tropospheric NO2 column, Ωs, along the optical path of the backscattered radiation detected by the satellite. The slant column is converted to the vertical column, Ωv, by using an air mass factor (AMF) that depends on the vertical profile of NO2 and on the scattering properties of the surface and the atmosphere (Palmer et al., 2001):

| (4) |

In Equation 4, AMFG is the geometric air mass factor that depends on the viewing geometry of the satellite, w(z) is a scattering weight calculated by a radiative transfer model that describes the sensitivity of the backscattered radiation to NO2 as a function of altitude, S(z) is a shape factor describing the normalized vertical profile of NO2 number density, and ZT is the tropopause. Scattering weights for NO2 retrievals typically increase by a factor of 3 from the surface to the upper troposphere (Martin et al., 2002). Here we use our GEOS-Chem shape factors to re-calculate the AMFs in the NASA and BEHR retrievals as recommended by Lamsal et al. (2014) for comparing model and observations. We filter out cloudy scenes (cloud radiance fraction > 0.5) and bright surfaces (surface reflectivity > 0.3).

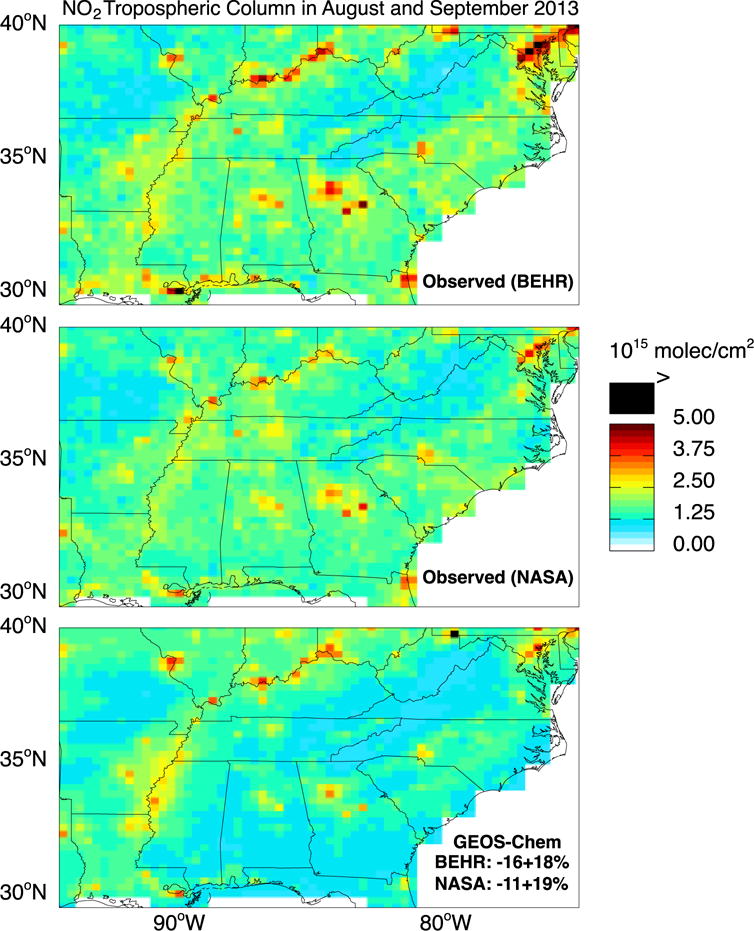

Figure 5 shows the mean NO2 tropospheric columns from BEHR, NASA, and GEOS-Chem (with NOx emission reductions applied) over the Southeast US for August–September 2013. The BEHR retrieval is on average 6% higher than the NASA retrieval. GEOS-Chem is on average 11±19% lower than the NASA retrieval and 16±18% lower than the BEHR retrieval. With the original NEI NOx emissions, GEOS-Chem would be biased high against both retrievals by 26–31%. The low bias in the model with reduced NOx emissions does not appear to be caused by an overcorrection of surface emissions but rather by the upper troposphere. Figure 6 (top left panel) shows the mean vertical profile of NO2 number density as measured from the aircraft by two independent instruments (NOAA and UC Berkeley) and simulated by GEOS-Chem. At the surface, the median difference is 1.8×109 molecules cm−3 which is within the NOAA and UC Berkeley measurement uncertainties of +/− 0.030 ppbv + 7% and +/− 5%, respectively. The observations show a secondary maximum in the upper troposphere above 10 km, absent in GEOS-Chem. It has been suggested that aircraft measurements of NO2 in the upper troposphere could be biased high due to decomposition in the instrument inlet of thermally unstable NOx reservoirs such as HNO4 and methylperoxynitrate (Browne et al., 2011; Reed et al., 2016). This would not affect the UC Berkeley measurement (Nault et al., 2015) and could possibly account for the difference with the NOAA a measurement in Figure 6.

Figure 5.

NO2 tropospheric columns over the Southeast US in August–September 2013. GEOS-Chem (sampled at the 13:30 local time overpass of OMI) is compared to OMI satellite observations using the BEHR and NASA retrievals. Values are plotted on the 0.25°×0.3125° GEOS-Chem grid. The GEOS-Chem mean bias over the Figure domain and associated spatial standard deviation are inset in the bottom panel.

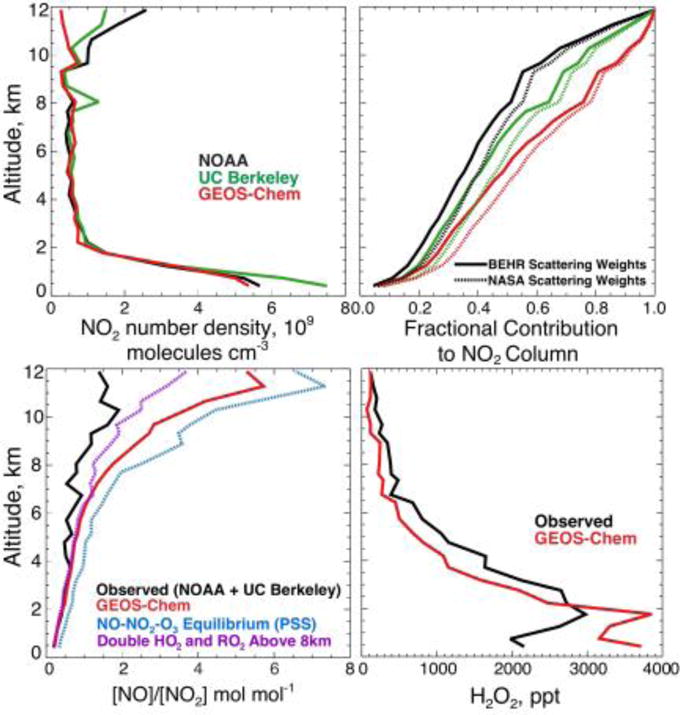

Figure 6.

Vertical distribution of NO2 over the Southeast US during SEAC4RS (August-September 2013) and contributions to tropospheric NO2 columns measured from space by OMI. The top left panel shows median vertical profiles of NO2 number density measured from the SEAC4RS aircraft by the NOAA and UC Berkeley instruments and simulated by GEOS-Chem. The top right panel shows the fractional contribution of NO2 below a given altitude to the total tropospheric NO2 slant column measured by OMI, accounting for increasing sensitivity with altitude as determined from the retrieval scattering weights. The bottom left panel shows the median vertical profiles of the daytime [NO]/[NO2] molar concentration ratio in the aircraft observations (NOAA for NO and UC Berkeley for NO2) and in GEOS-Chem. Also shown is the ratio computed from NO-NO2-O3 photochemical steady state (PSS) as given by reactions (5)+(7) (blue) and including reaction (6) with doubled HO2 and RO2 concentrations above 8km (purple). The bottom right panel shows the median H2O2 profile from the model and from the SEAC4RS flights over the Southeast US. H2O2 was measured by the Caltech CIMS (see Figure 2).

The top right panel of Figure 6 shows the cumulative contributions from different altitudes to the slant NO2 column measured by the satellite, using the median vertical profiles from the left panel and applying mean altitude-dependent scattering weights from the NASA and BEHR retrievals. The boundary layer below 1.5 km contributes only 19–28% of the column. The upper troposphere above 8 km contributes 32–49% in the aircraft observations and 23% in GEOS-Chem. Much of the observed upper tropospheric NO2 likely originates from lightning and is broadly distributed across the Southeast because of the long lifetime of NOx at that altitude (Li et al., 2005; Bertram et al., 2007; Hudman et al., 2007). The NO2 vertical profile (shape factor) assumed in the BEHR retrieval does not include any lightning influence, and the Global Modeling Initiative (GMI) model vertical profile assumed in the NASA retrieval has little contribution from the upper troposphere (Lamsal et al., 2014). These underestimates of upper tropospheric NO2 in the retrieval shape factors will cause a negative bias in the AMF and therefore a positive bias in the retrieved vertical columns.

The GEOS-Chem underestimate of observed upper tropospheric NO2 in Figure 6 is partly driven by NO/NO2 partitioning. The bottom left panel of Figure 6 shows the [NO]/[NO2] concentration ratio in GEOS-Chem and in the observations (NOAA for NO, UC Berkeley for NO2). One would expect the [NO]/[NO2] concentration ratio in the daytime upper troposphere to be controlled by photochemical steady-state:

| (5) |

| (6) |

| (7) |

If reaction (6) plays only a minor role then [NO]/[NO2] ≈ k7/(k5[O3]), defining the NO-NO2-O3 photochemical steady state (PSS). The PSS plotted in Figure 6 agrees closely with GEOS-Chem. Such agreement has previously been found when comparing photochemical models with observed [NO]/[NO2] ratios from aircraft in the marine upper troposphere (Schultz et al., 1999) and lower stratosphere (Del Negro et al., 1999). The SEAC4RS observations show large departure. The NO2 photolysis frequencies k7 computed locally by GEOS-Chem are on average within 10% of the values determined in SEAC4RS from measured actinic fluxes (Shetter and Muller, 1999), so this is not the problem.

A possible explanation is that the model underestimates peroxy radical concentrations and hence the contribution of reaction (6) in the upper troposphere. Zhu et al. (2016) found that GEOS-Chem underestimates the observed HCHO concentrations in the upper troposphere during SEAC4RS by a factor of 3, implying that the model underestimates the HOx source from convective injection of HCHO and peroxides (Jaeglé et al., 1997; Prather and Jacob, 1997; Müller and Brasseur, 1999). HO2 observations over the central US in summer during the SUCCESS aircraft campaign suggest that this convective injection increases HOx concentrations in the upper troposphere by a factor of 2 (Jaeglé et al., 1998). The bottom right panel of Figure 6 shows median modeled and observed vertical profiles of the HOx reservoir hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) during SEAC4RS over the Southeast US. GEOS-Chem underestimates observed H2O2 by a mean factor of 1.7 above 8km. The bottom left panel of Figure 6 shows the [NO]/[NO2] ratio in GEOS-Chem with HO2 and RO2 doubled above 8 km. Such a change corrects significantly the bias relative to observations.

The PSS and GEOS-Chem simulation of the NO/NO2 concentration ratio in Figure 6 use k5 = 3.0×10−12 exp[−1500/T] cm3 molecule−1 s−1 and spectroscopic information for k7 from Sander et al. (2011). It is possible that the strong thermal dependence of k5 has some error, considering that only one direct measurement has been published for the cold temperatures of the upper troposphere (Borders and Birks, 1982). Cohen et al. (2000) found that reducing the activation energy of k5 by 15% improved model agreement in the lower stratosphere. Correcting the discrepancy between simulated and observed [NO]/[NO2] ratios in the upper troposphere in Figure 6 would require a similar reduction to the activation energy of k5, but this reduction would negatively impact the surface comparison. This inconsistency of the observed [NO]/[NO2] ratio with basic theory needs to be resolved, as it affects the inference of NOx emissions from satellite NO2 column measurements. Notwithstanding this inconsistency, we find that NO2 in the upper troposphere makes a significant contribution to the tropospheric NO2 column observed from space.

5 Isoprene oxidation pathways

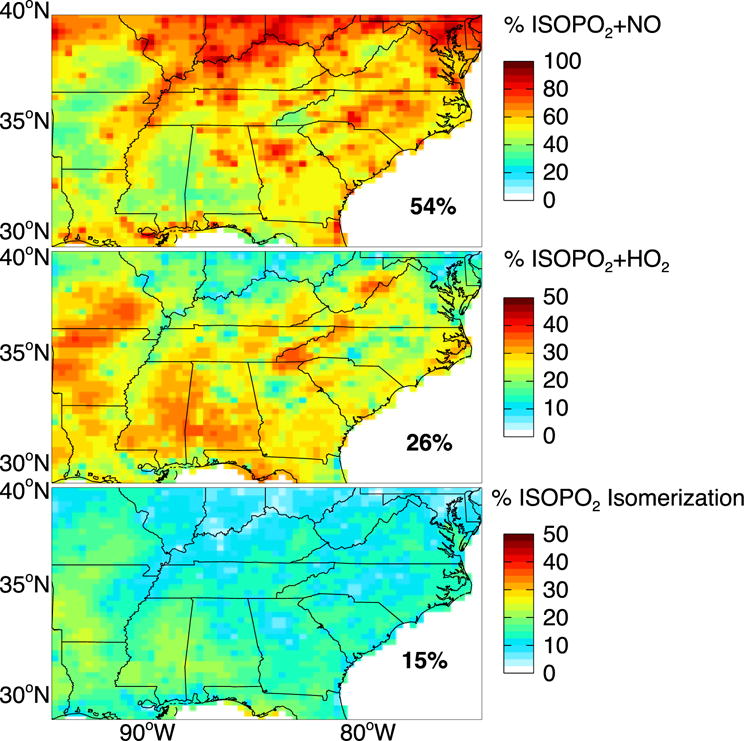

Measurements aboard the SEAC4RS aircraft included first-generation isoprene nitrates (ISOPN), isoprene hydroperoxide (ISOPOOH), and hydroperoxyaldehydes (HPALDs) (Crounse et al., 2006; Paulot et al., 2009a; St. Clair et al., 2010; Crounse et al., 2011; Beaver et al., 2012; Nguyen et al., 2015). Although measurement uncertainties are large (30%, 40%, and 50%, respectively (Nguyen et al., 2015)), these are unique products of the ISOPO2 + NO, ISOPO2 + HO2, and ISOPO2 isomerization pathways and thus track whether oxidation of isoprene proceeds by the high-NOx pathway (producing ozone) or the low-NOx pathways. Figure 2 (bottom row) compares simulated and observed concentrations. All three gases are restricted to the boundary layer because of their short lifetimes. Mean model concentrations in the lowest altitude bin (Figure 2, approximately 400m above ground) differ from observations by +19% for ISOPN, +70% for ISOPOOH, and −50% for HPALDs. The GEOS-Chem simulation of organic nitrates including ISOPN is further discussed in Fisher et al. (2016). Our HPALD source is based on the ISOPO2 isomerization rate constant from Crounse et al. (2011). A theoretical calculation by Peeters et al. (2014) suggests a rate constant that is 1.8× higher, which would reduce the model bias for HPALDs and ISOPOOH and increase boundary layer OH by 8%. St. Clair et al. (2015) found that the reaction rate of ISOPOOH + OH to form IEPOX is approximately 10% faster than the rate given by Paulot et al. (2009b), which would further reduce the model overestimate. For both ISOPOOH and HPALDs, GEOS-Chem captures much of the spatial variability (r = 0.80 and 0.79, respectively).

Figure 7 shows the model branching ratios for the fate of the ISOPO2 radical by tracking the mass of ISOPO2 reacting via the high-NOx pathway (ISOPO2+NO) and the low-NOx pathways over the Southeast US domain. The mean branching ratios for the Southeast US are ISOPO2+NO 54%, ISOPO2+HO2 26%, ISOPO2 isomerization 15%, and ISOPO2+RO2 5%. The lack of dominance of the high-NOx pathway is due in part to the spatial segregation of isoprene and NOx emissions (Yu et al., 2016). This segregation also buffers the effect of changing NOx emissions on the fate of isoprene. Our original simulation with higher total NOx emissions (unadjusted NEI11v1) had a branching ratio for the ISOPO2+NO reaction of only 62%.

Figure 7.

Branching ratios for the fate of the isoprene peroxy radical (ISOPO2) as simulated by GEOS-Chem over the Southeast US for August–September 2013. Values are percentages of ISOPO2 that react with NO, HO2, or isomerize from the total mass of isoprene reacting over the domain. Note the difference in scale between the top panel and the lower two panels. Regional mean percentages for the Southeast US are shown inset. They add up to less than 100% because of the small ISOPO2 sink from reaction with other organic peroxy radicals (RO2).

6 Implications for ozone: aircraft and ozonesonde observations

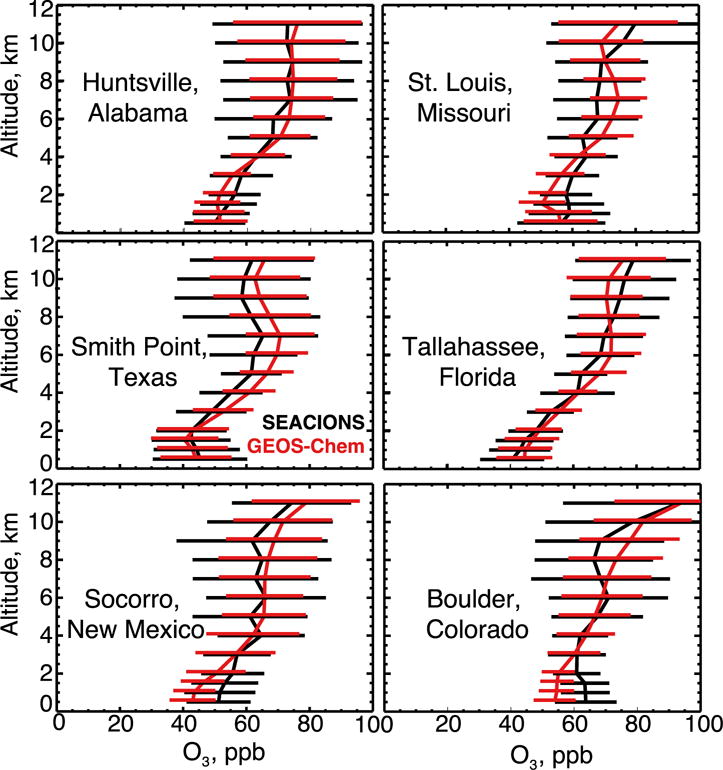

Figure 2 compares simulated and observed median vertical profiles of ozone concentrations over the Southeast US during SEAC4RS. There is no significant bias through the depth of the tropospheric column. The median ozone concentration below 1.5 km is 49 ppb in the observations and 51 ppb in the model. We also find excellent model agreement across the US with the SEACIONS ozonesonde network (Figure 8). The successful simulation of ozone is contingent on the decrease in NOx emissions. As shown in Figure 2, a simulation with the original NEI emissions overestimates boundary layer ozone by 12 ppb.

Figure 8.

Mean ozonesonde vertical profiles at the US SEACIONS sites (http://croc.gsfc.nasa.gov/seacions/) during the SEAC4RS campaign in August–September 2013. An average of 20 sondes were launched per site between 9am and 4pm local time. Ozonesondes at Smith Point, Texas were only launched in September. Model values are coincident with the launches. Data are averaged vertically over 0.5 km bins below 2 km altitude and 1.0 km bins above. Also shown are standard deviations.

The model also has success in reproducing the spatial variability of boundary layer ozone seen from the aircraft, as shown in Figure 4. The correlation coefficient is r = 0.71 on the 0.25°×0.3125° model grid, and patterns of high and low ozone concentration are consistent. The highest observed ozone (>75 ppb) was found in air influenced by agricultural burning along the Mississippi River and by outflow from Houston over Louisiana. GEOS-Chem does not capture the extreme values and this probably reflects a dilution effect (Yu et al., 2016).

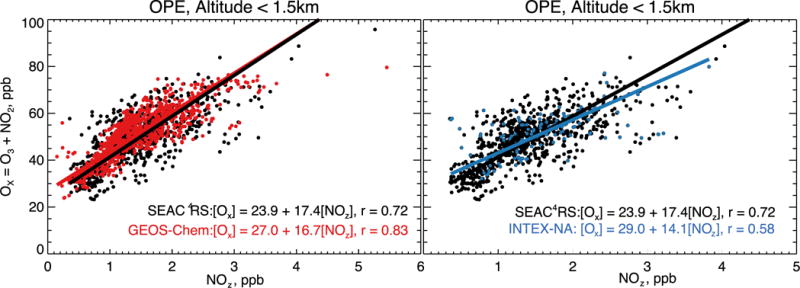

A critical parameter for understanding ozone production is the ozone production efficiency (OPE) (Liu et al., 1987), defined as the number of ozone molecules produced per molecule of NOx emitted. This can be estimated from atmospheric observations by the relationship between odd oxygen (Ox ≡ O3+NO2) and the sum of products of NOx oxidation, collectively called NOz and including inorganic and organic nitrates (Trainer et al., 1993; Zaveri, 2003). The Ox vs. NOz linear relationship (as derived from a linear regression) provides an upper estimate of the OPE because of rapid deposition of NOy, mainly HNO3 (Trainer et al., 2000; Rickard et al., 2002).

Figure 9 shows the observed and simulated daytime (9–16 local) Ox vs. NOz relationship in the SEAC4RS data below 1.5 km, where NOz is derived from the observations as NOy-NOx ≡ HNO3 + aerosol nitrate + PAN + alkyl nitrates. The resulting OPE from the observations (17.4±0.4 mol mol−1) agrees well with GEOS-Chem (16.7±0.3). Previous work during the INTEX-NA aircraft campaign in summer 2004 found an OPE of 8 below 4 km (Mena-Carrasco et al., 2007). By selecting INTEX-NA data only for the Southeast and below 1.5 km we find an OPE of 14.1±1.1 (Figure 9, right panel). The median NOz was 1.1 ppb during SEAC4RS and 1.5 ppb during INTEX-NA, a decrease of approximately 40%. With the original NEI11v1 NOx emissions (53% higher), the OPE from GEOS-Chem would be 14.7±0.3. Both the INTEX-NA data and the model are consistent with the expectation that OPE increases with decreasing NOx emissions (Liu et al., 1987).

Figure 9.

Ozone production efficiency (OPE) over the Southeast US in summer estimated from the relationship between odd oxygen (Ox) and the sum of NOx oxidation products (NOz) below 1.5 km altitude. The left panel compares SEAC4RS observations to GEOS-Chem values for August–September 2013 (data from Figure 2). The right panel compares SEAC4RS observations to INTEX-NA aircraft observations collected over the same Southeast US domain in summer 2004 (Singh et al., 2006). NOz is defined here as HNO3 + PAN + alklynitrates, all of which were measured from the SEAC4RS and INTEX-NA aircraft. The slope and intercept of the reduced-major-axis (RMA) regression are provided inset with the correlation coefficient (r). Observations for INTEX-NA were obtained from ftp://ftp-air.larc.nasa.gov/pub/INTEXA/.

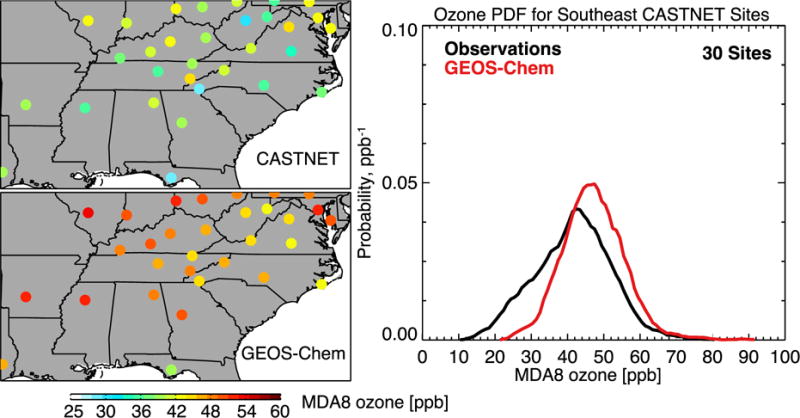

7 Implications for ozone: surface air

Figure 10 compares maximum daily 8-h average (MDA8) ozone values at the US EPA Clean Air Status and Trends Network (CASTNET) sites in June-August 2013 to the corresponding GEOS-Chem values. The model has a mean positive bias of 6±14 ppb with no significant spatial pattern. The model is unable to match the low tail in the observations, including a significant population with MDA8 ozone less than 20 ppb. The improvements to dry deposition described in Section 2.2 minimally reduce (approximately 1 ppb) GEOS-Chem ozone compared to SEAC4RS boundary layer and CASTNET surface MDA8 ozone observations. The reduction of daytime mixing depths described in Section 2 results in a small increase in mean MDA8 ozone (approximately 2 ppb).

Figure 10.

Maximum daily 8-h average (MDA8) ozone concentrations at the 30 CASTNET sites in the Southeast US in June–August 2013. The left panels show seasonal mean values in the observations and GEOS-Chem. The right panel shows the probability density functions (pdfs) of daily values at the 30 sites.

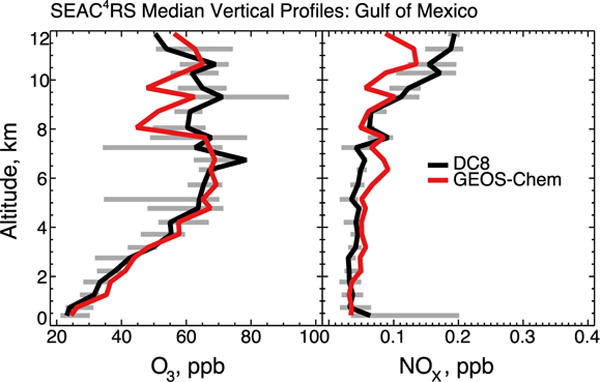

The positive bias in the model for surface ozone is remarkable considering that the model has little bias relative to aircraft observations below 1.5 km altitude (Figures 2 and 4). A standard explanation for model overestimates of surface ozone over the Southeast US, first proposed by Fiore et al. (2003) and echoed in the review by McDonald-Buller et al. (2011), is excessive ozone over the Gulf of Mexico, which is the prevailing low-altitude inflow. We find that this is not the case. SEAC4RS included four flights over the Gulf of Mexico, and Figure 11 compares simulated and observed vertical profiles of ozone and NOx concentrations that show no systematic bias. The median ozone concentration in the marine boundary layer is 26 ppb in the observations and 29 ppb in the model. This successful simulation is due to our adjustment of lightning NOx emission (Section 2.3); a sensitivity test with the original (twice higher) GEOS-Chem lightning emissions in the southern US increases surface ozone over the Gulf of Mexico by up to 6 ppb. The aircraft observations in Figure 4 further show no indication of a coastal depletion that might be associated with halogen chemistry. Remarkably, the median ozone over the Gulf of Mexico is higher than approximately 8% of MDA8 values at sites in the Southeast.

Figure 11.

Median vertical profiles of ozone and NOx concentrations over the Gulf of Mexico during SEAC4RS. Observations are from four SEAC4RS flights over the Gulf of Mexico (August 12, September 4, 13, 16). GEOS-Chem model values are sampled along the flight tracks. The 25th and 75th percentiles of the aircraft observations are shown as horizontal bars.

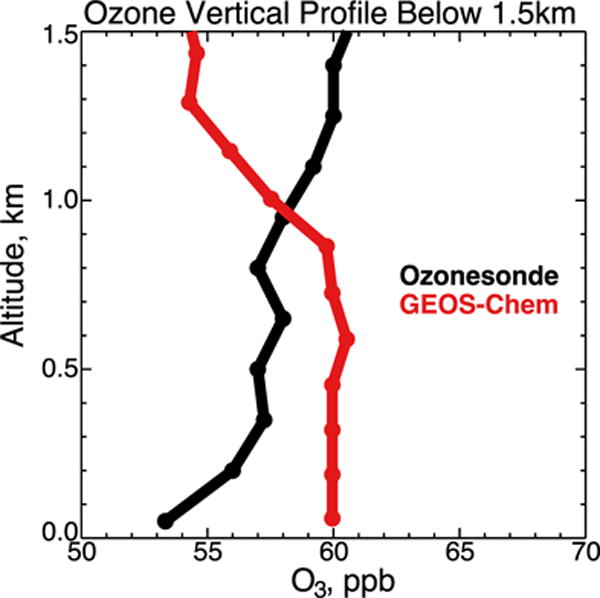

It appears instead that there is a model bias in boundary layer vertical mixing and chemistry. Figure 12 shows the median ozonesonde profile at a higher vertical resolution over the Southeast US (Huntsville, Alabama and St. Louis, Missouri sites) during SEAC4RS as compared to GEOS-Chem below 1.5 km. The ozonesondes indicate a decrease of 7 ppb from 1.5 km to the surface, whereas GEOS-Chem features a reverse gradient of increasing ozone from 1.5 to 1 km with flat concentrations below. This implies a combination of two model errors in the boundary layer: (1) excessive vertical mixing, (2) net ozone production whereas observations indicate a net loss.

Figure 12.

Median vertical profile of ozone concentrations over St. Louis, Missouri and Huntsville, Alabama during August and September 2013. Observations from SEACIONS ozonesondes launched between 10 and 13 local time (57 launches) are compared to GEOS-Chem results sampled at the times of the ozonesonde launches and at the vertical resolution of the model (11 layers below 1.5km, red circles). The ozonesonde data are shown at 150m resolution. Altitude is above local ground level.

8 Conclusions

We used aircraft (SEAC4RS), surface, satellite, and ozonesonde observations from August and September 2013, interpreted with the GEOS-Chem chemical transport model, to better understand the factors controlling surface ozone in the Southeast US. Models tend to overestimate ozone in that region. Determining the reasons behind this overestimate is critical to the design of efficient emission control strategies to meet the ozone NAAQS.

A major finding from this work is that the EPA National Emission Inventory (NEI11v1) for NOx (the limiting precursor for ozone formation) is biased high across the US by as much as a factor of 2. Evidence for this comes from (1) SEAC4RS observations of NOx and its oxidation products, (2) NADP network observations of nitrate wet deposition fluxes, and (3) OMI satellite observations of NO2. Presuming no error in emissions from large power plants with continuous emission monitors (14% of unadjusted NEI inventory), we find that emissions from other industrial sources and mobile sources must be 30–60% lower than NEI values, depending on the assumption of the contribution from soil NOx emissions. We thus estimate that anthropogenic fuel NOx emissions in the US in 2013 were 1.7–2.6 Tg N a−1, as compared to 3.5 Tg N a−1 given in the NEI.

OMI NO2 satellite data over the Southeast US are consistent with this downward correction of NOx emissions but interpretation is complicated by the large contribution of the free troposphere to the NO2 tropospheric column retrieved from the satellite. Observed (aircraft) and simulated vertical profiles indicate that NO2 below 2 km contributes only 20–35% of the tropospheric column detected from space while NO2 above 8 km (mainly from lightning) contributes 25–50%. Current retrievals of satellite NO2 data do not properly account for this elevated pool of upper tropospheric NO2, so that the reported tropospheric NO2 columns are biased high. More work is needed on the chemistry maintaining high levels of NO2 in the upper troposphere.

Isoprene emitted by vegetation is the main VOC precursor of ozone in the Southeast in summer, but we find that only 50% reacts by the high-NOx pathway to produce ozone. This is consistent with detailed aircraft observations of isoprene oxidation products from the aircraft. The high-NOx fraction is only weakly sensitive to the magnitude of NOx emissions because isoprene and NOx emissions are spatially segregated. The ability to properly describe high- and low-NOx pathways for isoprene oxidation is critical for simulating ozone and it appears that the GEOS-Chem mechanism is successful for this purpose.

Our updated GEOS-Chem simulation with decreased NOx emissions provides an unbiased simulation of boundary layer and free tropospheric ozone measured from aircraft and ozonesondes during SEAC4RS. Decreasing NOx emissions is critical to this success as the original model with NEI emissions overestimated boundary layer ozone by 12 ppb. The ozone production efficiency (OPE) inferred from Ox vs. NOz aircraft correlations in the mixed layer is also well reproduced. Comparison to the INTEX-NA aircraft observations over the Southeast in summer 2004 indicates a 14% increase in OPE associated with a 40% reduction in NOx emissions.

Despite the successful simulation of boundary layer ozone (Figures 2 and 9), GEOS-Chem overestimates MDA8 surface ozone observations in the Southeast US in summer by 6±14 ppb. Daytime ozonesonde data indicate a 7 ppb decrease from 1.5 km to the surface that GEOS-Chem does not capture. This may be due to excessive boundary layer mixing and net ozone production in the model. Excessive mixing in GEOS-Chem may be indicative of an overestimate of sensible heat flux (Holtslag and Boville, 1993), and thus an investigation of boundary layer meteorological variables is warranted. Such a bias may not be detected in the comparison of GEOS-Chem with aircraft data, generally collected under fair-weather conditions and with minimal sampling in the lower part of the boundary layer. An investigation of relevant meteorological variables and boundary layer source and sink terms in the ozone budget to determine the source of bias and its prevalence across models will be the topic of a follow-up paper.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the entire NASA SEAC4RS team for their help in the field. We thank Tom Ryerson for his measurements of NO and NO2 from the NOAA NOyO3 instrument. We thank L. Gregory Huey for the use of his CIMS PAN measurements. We thank Fabien Paulot and Jingqiu Mao for their helpful discussions of isoprene chemistry. We thank Christoph Keller for his help in implementing the NEI11v1 emissions into GEOS-Chem. We acknowledge the EPA for providing the 2011 North American emission inventory, and in particular George Pouliot for his help and advice. These emission inventories are intended for research purposes. A technical report describing the 2011-modeling platform can be found at: http://www.epa.gov/ttn/chief/net/2011nei/2011_nei_tsdv1_draft2_june2014.pdf. A description of the 2011 NEI can be found at: http://www.epa.gov/ttnchie1/net/2011inventory.html. This work was supported by the NASA Earth Science Division and by STAR Fellowship Assistance Agreement no. 91761601-0 awarded by the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). It has not been formally reviewed by EPA. The views expressed in this publication are solely those of the authors. JAF acknowledges support from a University of Wollongong Vice Chancellor’s Postdoctoral Fellowship. This research was undertaken with the assistance of resources provided at the NCI National Facility systems at the Australian National University through the National Computational Merit Allocation Scheme supported by the Australian Government.

References

- Air Sciences, I. 2002 Fire Emission Inventory for the WRAP Region - Phase II, Western Governors Association/Western Regional Air Parnership. 2005 [Google Scholar]

- Alvarado MJ, Logan JA, Mao J, Apel E, Riemer D, Blake D, Cohen RC, Min KE, Perring AE, Browne EC, Wooldridge PJ, Diskin GS, Sachse GW, Fuelberg H, Sessions WR, Harrigan DL, Huey G, Liao J, Case-Hanks A, Jimenez JL, Cubison MJ, Vay SA, Weinheimer AJ, Knapp DJ, Montzka DD, Flocke FM, Pollack IB, Wennberg PO, Kurten A, Crounse J, Clair JMS, Wisthaler A, Mikoviny T, Yantosca RM, Carouge CC, Le Sager P. Nitrogen oxides and PAN in plumes from boreal fires during ARCTAS-B and their impact on ozone: an integrated analysis of aircraft and satellite observations. Atmos Chem Phys. 2010;10:9739–9760. doi: 10.5194/acp-10-9739-2010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson DC, Loughner CP, Diskin G, Weinheimer A, Canty TP, Salawitch RJ, Worden HM, Fried A, Mikoviny T, Wisthaler A, Dickerson RR. Measured and modeled CO and NOy in DISCOVER-AQ: An evaluation of emissions and chemistry over the eastern US. Atmos Environ. 2014;96:78–87. doi: 10.1016/j.atmosenv.2014.07.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bates KH, Crounse JD, St Clair JM, Bennett NB, Nguyen TB, Seinfeld JH, Stoltz BM, Wennberg PO. Gas Phase Production and Loss of Isoprene Epoxydiols. J Phys Chem-US A. 2014;118:1237–1246. doi: 10.1021/Jp4107958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaver MR, St Clair JM, Paulot F, Spencer KM, Crounse JD, LaFranchi BW, Min KE, Pusede SE, Woolridge PJ, Schade GW, Park C, Cohen RC, Wennberg PO. Importance of biogenic precursors to the budget of organic nitrates: observations of multifunctional organic nitrates by CIMS and TD-LIF during BEARPEX 2009. Atmos Chem Phys. 2012;12:5773–5785. [Google Scholar]

- Bertram TH, Perring AE, Wooldridge PJ, Crounse JD, Kwan AJ, Wennberg PO, Scheuer E, Dibb J, Avery M, Sachse G, Vay SA, Crawford JH, McNaughton CS, Clarke A, Pickering KE, Fuelberg H, Huey G, Blake DR, Singh HB, Hall SR, Shetter RE, Fried A, Heikes BG, Cohen RC. Direct Measurements of the Convective Recycling of the Upper Troposphere. Science. 2007;315 doi: 10.1126/science.1134548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bey I, Jacob DJ, Yantosca RM, Logan JA, Field BD, Fiore AM, Li QB, Liu HGY, Mickley LJ, Schultz MG. Global modeling of tropospheric chemistry with assimilated meteorology: Model description and evaluation. J Geophys Res-Atmos. 2001;106:23073–23095. doi: 10.1029/2001jd000807. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Borders RA, Birks JW. High-Precision Measurements of Activation Energies over Small Temperature Intervals: Curvature in the Arrhenius Plot for the Reaction NO + O3 –> NO2 + O2. J Phys Chem-US. 1982;86:3295–3302. [Google Scholar]

- Brioude J, Angevine WM, Ahmadov R, Kim SW, Evan S, McKeen SA, Hsie EY, Frost GJ, Neuman JA, Pollack IB, Peischl J, Ryerson TB, Holloway J, Brown SS, Nowak JB, Roberts JM, Wofsy SC, Santoni GW, Oda T, Trainer M. Top-down estimate of surface flux in the Los Angeles Basin using a mesoscale inverse modeling technique: assessing anthropogenic emissions of CO, NOx and CO2 and their impacts. Atmos Chem Phys. 2013;13:3661–3677. doi: 10.5194/acp-13-3661-2013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brown-Steiner B, Hess PG, Lin MY. On the capabilities and limitations of GCCM simulations of summertime regional air quality: A diagnostic analysis of ozone and temperature simulations in the U S using CESM CAM -Chem. Atmos Environ. 2015;101:134–148. doi: 10.1016/j.atmosenv.2014.11.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Browne EC, Perring AE, Wooldridge PJ, Apel E, Hall SR, Huey LG, Mao J, Spencer KM, Clair JMS, Weinheimer AJ, Wisthaler A, Cohen RC. Global and regional effects of the photochemistry of CH3O2NO2: evidence from ARCTAS. Atmos Chem Phys. 2011;11:4209–4219. doi: 10.5194/acp-11-4209-2011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brunner D, Staehelin J, Jeker D, Wernli H, Schumann U. Nitrogen oxides and ozone in the tropopause region of the Northern Hemisphere: Measurements from commercial aircraft in 1996/1996 and 1997. J Geophys Res. 2001;106:27,673–27,699. [Google Scholar]

- Bucsela EJ, Krotkov NA, Celarier EA, Lamsal LN, Swartz WH, Bhartia PK, Boersma KF, Veefkind JP, Gleason JF, Pickering KE. A new stratospheric and tropospheric NO2 retrieval algorithm for nadir-viewing satellite instruments: applications to OMI. Atmospheric Measurement Techniques. 2013;6:2607–2626. doi: 10.5194/amt-6-2607-2013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Canty TP, Hembeck L, Vinciguerra TP, Anderson DC, Goldberg DL, Carpenter SF, Allen DJ, Loughner CP, Salawitch RJ, Dickerson RR. Ozone and NOx chemistry in the eastern US: evaluation of CMAQ/CB05 with satellite (OMI) data. Atmos Chem Phys. 2015;15:10965–10982. doi: 10.5194/acp-15-10965-2015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter LJ, Clemitshaw KC, Burgess RA, Penkett SA, Cape JN, McFadyen GG. Investigation and evaluation of the NOx/O3 photochemical steady state. Atmos Environ. 1998;32:3353–3365. [Google Scholar]

- Castellanos P, Marufu LT, Doddridge BG, Taubman BF, Schwab JJ, Hains JC, Ehrman SH, Dickerson RR. Ozone, oxides of nitrogen, and carbon monoxide during pollution events over the eastern United States: An evaluation of emissions and vertical mixing. J Geophys Res. 2011;116:D16307. doi: 10.1029/2010JD014540. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen D, Wang YX, McElroy MB, He K, Yantosca RM, Le Sager P. Regional CO pollution in China simulated by the high-resolution nested-grid GEOS-Chem model. Atmos Chem Phys. 2009;9:3825–3839. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen RC, Perkins KK, Koch LC, Stimpfle RM, Wennberg PO, Hanisco TF, Lanzendorf EJ, Bonne GP, Voss PB, Salawitch RJ, Del Negro LA, Wilson JC, McElroy CT, Bui TP. Quantitative constraints on the atmospheric chemistry of nitrogen oxides: An analysis along chemical coordinates. J Geophys Res. 2000;105:24,283–24,304. [Google Scholar]

- Crounse JD, McKinney KA, Kwan AJ, Wennberg PO. Measurement of gas-phase hydroperoxides by chemical ionization mass spectrometry (CIMS) Anal Chem. 2006;78:6726–6732. doi: 10.1021/ac0604235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crounse JD, Paulot F, Kjaergaard HG, Wennberg PO. Peroxy radical isomerization in the oxidation of isoprene. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2011;13:13607–13613. doi: 10.1039/c1cp21330j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darmenov AS, da Silva A. The Quick Fire Emissions Dataset (QFED) Documentatino of versions 2.1, 2.2 and 2.4. NASA; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Dibb JE, Talbot RW, Scheuer EM, Seid G, Avery MA, Singh HB. Aerosol chemical composition in Asian continental outflow during the TRACE-P campaign: Comparison with PEM -West B. J Geophys Res. 2003;108 doi: 10.1029/2002jd003111. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Del Negro LA, Fahey DW, Gao RS, Donnelly SG, Keim ER, Neuman JA, Cohen RC, Perkins KK, Koch LC, Salawitch RJ, Lloyd SA, Proffitt MH, Margitan JJ, Stimpfle RM, Bonne GP, Voss PB, Wennberg PO, McElroy CT, Swartz WH, Kusterer TL, Anderson DE, Lait LR, Bui TP. Comparison of modeled and observed values of NO2 and JNO2 during the Photochemistry of Ozone Loss in the Arctic Region in Summer (POLARIS) mission. J Geophys Res. 1999;104:26687. doi: 10.1029/1999jd900246. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan BN, Prados AI, Lamsal LN, Liu Y, Streets DG, Gupta P, Hilsenrath E, Kahn RA, Nielsen JE, Beyersdorf AJ, Burton SP, Fiore AM, Fishman J, Henze DK, Hostetler CA, Krotkov NA, Lee P, Lin M, Pawson S, Pfister G, Pickering KE, Pierce RB, Yoshida Y, Ziemba LD. Satellite data of atmospheric pollution for U.S. air quality applications: Examples of applications, summary of data end-user resources, answers to FAQs, and common mistakes to avoid. Atmos Environ. 2014;94:647–662. doi: 10.1016/j.atmosenv.2014.05.061. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- EPA. Integrated Science Assessment for Ozone and Related Photochemical Oxidatns. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency; Research Triangle Park, NC: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- National Emissions Inventory (NEI) Air Pollutant Emission Trends Data. 2015 http://www.epa.gov/ttn/chief/trends/index.html.

- Finkelstein PL, Ellestad TG, Clarke JF, Meyers TP, Schwede DB, Hebert EO, Neal JA. Ozone and sulfur dioxide dry deposition to forests: Observations and model evaluation. J Geophys Res-Atmos. 2000;105:15365–15377. doi: 10.1029/2000jd900185. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fiore AM, Jacob DJ, Liu H, Yantosca RM, Fairlie TD, Li Q. Variability in surface ozone background over the United States: Implications for air quality policy. J Geophys Res-Atmos. 2003;108 doi: 10.1029/2003jd003855. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fiore AM, Horowitz LW, Purves DW, Levy H, Evans MJ, Wang Y, Li Q, Yantosca R. Evaluating the contribution of changes in isoprene emissions to surface ozone trends over the eastern United States. J Geophys Res. 2005;110 doi: 10.1029/2004jd005485. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fiore AM, Dentener FJ, Wild O, Cuvelier C, Schultz MG, Hess P, Textor C, Schulz M, Doherty RM, Horowitz LW, MacKenzie IA, Sanderson MG, Shindell DT, Stevenson DS, Szopa S, Van Dingenen R, Zeng G, Atherton C, Bergmann D, Bey I, Carmichael G, Collins WJ, Duncan BN, Faluvegi G, Folberth G, Gauss M, Gong S, Hauglustaine D, Holloway T, Isaksen ISA, Jacob DJ, Jonson JE, Kaminski JW, Keating TJ, Lupu A, Marmer E, Montanaro V, Park RJ, Pitari G, Pringle KJ, Pyle JA, Schroeder S, Vivanco MG, Wind P, Wojcik G, Wu S, Zuber A. Multimodel estimates of intercontinental source-receptor relationships for ozone pollution. J Geophys Res. 2009;114 doi: 10.1029/2008jd010816. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer EV, Jacob DJ, Yantosca RM, Sulprizio MP, Millet DB, Mao J, Paulot F, Singh HB, Roiger A, Ries L, Talbot RW, Dzepina K, Deolal SP. Atmospheric peroxyacetyl nitrate (PAN): a global budget and source attribution. Atmos Chem Phys. 2014;14:2679–2698. doi: 10.5194/acp-14-2679-2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher JA, Jacob DD, Travis KR, Kim PS, Marais E, Miller CC, Yu K, Zhu L, Yantosca RM, Sulprizio MP, Mao J, Wennberg PO, Crounse JD, Teng AP, Nguyen TB, St Clair JM, Romer P, Nault BA, Wooldridge PJ, Jimenez JL, Campuzano-Jost P, Day DA, Shepson PB, Xiong F, Blake DR, Goldstein AH, Misztal PK, Hanisco TF, Wolfe GM, Ryerson TB, Wisthaler A, Mikoviny T. Organic nitrate chemistry and its implications for nitrogen budgets in an isoprene- and monoterpene-rich atmosphere: constrains from aircraft (SEAC4RS) and ground-based (SOAS) observations in the Southeast US. Atmos Chem Phys. 2016;6:5969–5991. doi: 10.5194/acp-16-5969-2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujita EM, Campbell DE, Zielinska B, Chow JC, Lindhjem CE, DenBleyker A, Bishop GA, Schuchmann BG, Stedman DH, Lawson DR. Comparison of the MOVES2010a, MOBILE6.2, and EMFAC2007 mobile source emission models with on-road traffic tunnel and remote sensing measurements. J Air Waste Manage. 2012;62:1134–1149. doi: 10.1080/10962247.2012.699016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holtslag A, Boville B. Local versus nonlocal boundary-layer diffusion in a global climate model. J Climate. 1993;6:1825. [Google Scholar]

- Horowitz LW, Fiore AM, Milly GP, Cohen RC, Perring A, Wooldridge PJ, Hess PG, Emmons LK, Lamarque JF. Observational constraints on the chemistry of isoprene nitrates over the eastern United States. J Geophys Res-Atmos. 2007;112 doi: 10.1029/2006jd007747. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hudman RC, Jacob DJ, Turquety S, Leibensperger EM, Murray LT, Wu S, Gilliland AB, Avery M, Bertram TH, Brune W, Cohen RC, Dibb JE, Flocke FM, Fried A, Holloway J, Neuman JA, Orville R, Perring A, Ren X, Sachse GW, Singh HB, Swanson A, Wooldridge PJ. Surface and lightning sources of nitrogen oxides over the United States : Magnitudes, chemical evolution, and outflow. J Geophys Res. 2007;112 doi: 10.1029/2006jd007912. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hudman RC, Moore NE, Mebust AK, Martin RV, Russell AR, Valin LC, Cohen RC. Steps towards a mechanistic model of global soil nitric oxide emissions: implementation and space based-constraints. Atmos Chem Phys. 2012;12:7779–7795. doi: 10.5194/acp-12-7779-2012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huntrieser H, Schlager H, Roiger A, Lichtenstern M, Schumann U, Kurz C, Brunner D, Schwierz C, Richter A, Stohl A. Lightning-produced NOx over Brazil during TROC-CINOX: airborne measurements in tropical and subtropical thun-derstorms and the importance of mesoscale convective systems. Atmos Chem Phys. 2007;7:2987–3013. doi: 10.5194/acp-7-2987-2007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huntrieser H, Schumann U, Schlager H, Höller H, Giez A, Betz HD, Brunner D, Forster C, Pinto O, Jr, Calheiros R. Lightning activity in Brazilian thunderstorms during TROCCINOX: implications for NOx production. Atmos Chem Phys. 2008;8:921–953. doi: 10.5194/acp-8-921-2008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs MI, Burke WJ, Elrod MJ. Kinetics of the reactions of isoprene-derived hydroxynitrates: gas phase epoxide formation and solution phase hydrolysis. Atmos Chem Phys. 2014;14:8933–8946. doi: 10.5194/acp-14-8933-2014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jaeglé L, Jacob DJ, Wang Y, Weinheimer AJ, Ridley BA, Campos TL, Sachse GW, Hagen DE. Sources and chemistry of NOx in the upper troposphere over the United States. Geophys Res Lett. 1998;25(10):1705–1708. [Google Scholar]

- Jaeglé L, Jacob DJ, Wennberg PO, Spivakovsky CM, Hanisco TF, Lanzendorf EL, Hintsa EJ, Fahey DW, Keim ER, Proffitt MH, Atlas E, Flocke F, Schauffler S, McElroy CT, Midwinter C, Pfister L, Wilson JC. Observed OH and HO2 in the upper troposphere suggest a major source from convective injection of peroxides. Geophys Res Lett. 1997;24:3181–3184. [Google Scholar]

- Kim PS, Jacob DJ, Fisher JA, Travis K, Yu K, Zhu L, Yantosca RM, Sulprizio MP, Jimenez JL, Campuzano-Jost P, Froyd KD, Liao J, Hair JW, Fenn MA, Butler CF, Wagner NL, Gordon TD, Welti A, Wennberg PO, Crounse JD, St Clair JM, Teng AP, Millet DB, Schwarz JP, Markovic MZ, Perring AE. Sources, seasonality, and trends of Southeast US aerosol: an integrated analysis of surface, aircraft, and satellite observations with the GEOS-Chem chemical transport model. Atmos Chem Phys. 2015;15:10411–10433. doi: 10.5194/acp-15-10411-2015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lamsal LN, Krotkov NA, Celarier EA, Swartz WH, Pickering KE, Bucsela EJ, Gleason JF, Martin RV, Philip S, Irie H, Cede A, Herman J, Weinheimer A, Szykman JJ, Knepp TN. Evaluation of OMI operational standard NO2 column retrievals using in situ and surface-based NO2 observations. Atmos Chem Phys. 2014;14:11587–11609. doi: 10.5194/acp-14-11587-2014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q, Jacob DJ, Park R, Wang Y, Heald CL, Hudman R, Yantosca RM. North American pollution outflow and the trapping of convectively lifted pollution by upper-level anticyclone. J Geophys Res. 2005;110 doi: 10.1029/2004JD005039. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Rohrer F, Hofzumahaus A, Brauers T, Haseler R, Bohn B, Broch S, Fuchs H, Gomm S, Holland F, Jager J, Kaiser J, Keutsch FN, Lohse I, Lu K, Tillmann R, Wegener R, Wolfe GM, Mentel TF, Kiendler-Scharr A, Wahner A. Missing gas-phase source of HONO inferred from Zeppelin measurements in the troposphere. Science. 2014;344:292–296. doi: 10.1126/science.1248999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin J, Youn D, Liang X, Wuebbles D. Global model simulation of summertime U.S. ozone diurnal cycle and its sensitivity to PBL mixing, spatial resolution, and emissions. Atmos Environ. 2008;42:8470–8483. doi: 10.1016/j.atmosenv.2008.08.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lin JT, McElroy MB. Impacts of boundary layer mixing on pollutant vertical profiles in the lower troposphere: Implications to satellite remote sensing. Atmos Environ. 2010;44:1726–1739. doi: 10.1016/j.atmosenv.2010.02.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu SC, Trainer M, Fehsenfeld FC, Parrish DD, Williams EJ, Fahey DW, Hubler G, Murphy PC. Ozone Production in the Rural Troposphere and the Implications for Regional and Global Ozone Distributions. J Geophys Res. 1987;92:4191–4207. [Google Scholar]

- Liu YJ, Herdlinger-Blatt I, McKinney KA, Martin ST. Production of methyl vinyl ketone and methacrolein via the hydroperoxyl pathway of isoprene oxidation. Atmos Chem Phys. 2013;13:5715–5730. doi: 10.5194/acp-13-5715-2013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Z, Streets DG, de Foy B, Lamsal LN, Duncan BN, Xing J. Emissions of nitrogen oxides from US urban areas: estimation from Ozone Monitoring Instrument retrievals for 2005-2014. Atmos Chem Phys. 2015;15:10367–10383. doi: 10.5194/acp-15-10367-2015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mao J, Jacob DJ, Evans MJ, Olson JR, Ren X, Brune WH, Clair JMS, Crounse JD, Spencer KM, Beaver MR, Wennberg PO, Cubison MJ, Jimenez JL, Fried A, Weibring P, Walega JG, Hall SR, Weinheimer AJ, Cohen RC, Chen G, Crawford JH, McNaughton C, Clarke AD, Jaeglé L, Fisher JA, Yantosca RM, Le Sager P, Carouge C. Chemistry of hydrogen oxide radicals (HOx) in the Arctic troposphere in spring. Atmos Chem Phys. 2010;10:5823–5838. doi: 10.5194/acp-10-5823-2010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mao J, Paulot F, Jacob DJ, Cohen RC, Crounse JD, Wennberg PO, Keller CA, Hudman RC, Barkley MP, Horowitz LW. Ozone and organic nitrates over the eastern United States: Sensitivity to isoprene chemistry. J Geophys Res: Atmospheres. 2013;118:11,256–11,268. doi: 10.1002/jgrd.50817. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Marais EA, Jacob DJ, Jimenez JL, Campuzano-Jost P, Day DA, Hu W, Krechmer J, Zhu L, Kim PS, Miller CC, Fisher JA, Travis K, Yu K, Hanisco TF, Wolfe GM, Arkinson HL, Pye HOT, Froyd KD, Liao J, McNeil FV. Aqueous-phase mechanism for secondary organic aerosol formation from isoprene: application to the Southeast United States and co-benefit of SO2 emission controls. Atmos Chem Phys. 2016;16:1603–1618. doi: 10.5194/acp-16-1603-2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin RV, Chance K, Jacob DJ, Kurosu TP, Spurr RJD, Bucsela E, Gleason JF, Palmer PI, Bey I, Fiore AM, Li Q, Yantosca RM, Koelemeijer RBA. An improved retrieval of tropospheric nitrogen dioxide from GOME. J Geophys Res. 2002;107 doi: 10.1029/2001jd001027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald-Buller EC, Allen DT, Brown N, Jacob DJ, Jaffe D, Kolb CE, Lefohn AS, Oltmans S, Parrish DD, Yarwood G, Zhang L. Establishing policy relevant background (PRB) ozone concentrations in the United States. Envir Sci Tech. 2011;45:9484–9497. doi: 10.1021/es2022818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mena-Carrasco M, Tang Y, Carmichael GR, Chai T, Thongbongchoo N, Campbell JE, Kulkarni S, Horowitz L, Vukovich J, Avery M, Brune W, Dibb JE, Emmons L, Flocke F, Sachse GW, Tan D, Shetter R, Talbot RW, Streets DG, Frost G, Blake D. Improving regional ozone modeling through systematic evaluation of errors using the aircraft observations during the International Consortium for Atmospheric Research on Transport and Transformation. J Geophys Res. 2007;112 doi: 10.1029/2006jd007762. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Müller JF, Brasseur G. Sources of upper tropospheric HOx: A three-dimensional study. J Geophs Res. 1999;104:1705–1715. [Google Scholar]

- Murray LT, Jacob DJ, Logan JA, Hudman RC, Koshak WJ. Optimized regional and interannual variability of lightning in a global chemical transport model constrained by LIS/OTD satellite data. J Geophys Res. 2012;117 doi: 10.1029/2012jd017934. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- NADP. National Atmospheric Deposition Program (NRSP-3) In: Office, N. P., editor. Illinois State Water Survey. 2204 Griffith Dr., Champaign, IL 61820: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Center, N. G. S. F, editor. NASA, U. G. OMI/Aura Level 2 Nitrogen Dioxide (NO2) Trace Gas Column Data 1-Orbit subset Swath along Cloud Sat track 1-Orbit Swath 13×24 km, version 003. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Nault BA, Garland C, Pusede SE, Wooldridge PJ, Ullmann K, Hall SR, Cohen RC. Measurements of CH3O2NO2 in the upper troposphere. Atmospheric Measurement Techniques. 2015;8:987–997. doi: 10.5194/amt-8-987-2015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen TB, Crounse JD, Teng AP, St Clair JM, Paulot F, Wolfe GM, Wennberg PO. Rapid deposition of oxidized biogenic compounds to a temperate forest. P Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112:E392–401. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1418702112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ott LE, Pickering KE, Stenchikov GL, Allen DJ, DeCaria AJ, Ridley B, Lin RF, Lang S, Tao WK. Production of lightning NOx and its vertical distribution calculated from three-dimensional cloud-scale chemical transport model simulations. J Geophys Res. 2010;115 doi: 10.1029/2009jd011880. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer PI, Jacob DJ, Chance K, Martin RV, Spurr RJD, Kurosu TP, Bey I, Yantosca R, Fiore A, Li Q. Air mass factor formulation for spectroscopic measurements from satellites: Application to formaldehyde retrievals from the Global Ozone Monitoring Experiment. J Geophys Res. 2001;106:14539. doi: 10.1029/2000jd900772. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Paulot F, Crounse JD, Kjaergaard HG, Kroll JH, Seinfeld JH, Wennberg PO. Isoprene photooxidation: new insights into the production of acids and organic nitrates. Atmos Chem Phys. 2009a;9:1479–1501. [Google Scholar]

- Paulot F, Crounse JD, Kjaergaard HG, Kurten A, St Clair JM, Seinfeld JH, Wennberg PO. Unexpected Epoxide Formation in the Gas-Phase Photooxidation of Isoprene. Science. 2009b;325:730–733. doi: 10.1126/Science.1172910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paulot F, Jacob DJ, Pinder RW, Bash JO, Travis K, Henze DK. Ammonia emissions in the United States, European Union, and China derived by high-resolution inversion of ammonium wet deposition data: Interpretation with a new agricultural emissions inventory (MASAGE_NH3) J Geophys Res: Atmospheres. 2014;119:4343–4364. doi: 10.1002/2013jd021130. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Peeters J, Nguyen TL, Vereecken L. HOx radical regeneration in the oxidation of isoprene. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2009;11:5935–5939. doi: 10.1039/b908511d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peeters J, Müller JF. HO(x) radical regeneration in isoprene oxidation via peroxy radical isomerisations. II: experimental evidence and global impact. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2010;12:14227–14235. doi: 10.1039/c0cp00811g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peeters J, Müller JF, Stavrakou T, Nguyen VS. Hydroxyl radical recycling in isoprene oxidation driven by hydrogen bonding and hydrogen tunneling: the upgraded LIM1 mechanism. J Phys Chem-US A. 2014;118:8625–8643. doi: 10.1021/jp5033146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollack IB, Lerner BM, Ryerson TB. Evaluation of ultraviolet light-emitting diodes for detection of atmospheric NO2 by photolysis – chemilumenescence. J Atmos Chem. 2010;65(2):111–125. doi: 10.1007/s10874-011-9184-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Prather MJ, Jacob DJ. A persistent imbalance in HOx and NOx photochemistry of the upper troposphere driven by deep tropical convection. Geophys Res Lett. 1997;24:3189–3192. [Google Scholar]

- Reed C, Evans MJ, Di Carlo P, Lee JD, Carpenter LJ. Interferences in photolytic NO2 measurements: explanation for an apparent missing oxidant? Atmos Chem Phys. 2016;16:4707–4724. doi: 10.5194/acp-16-4707-2016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Reidmiller DR, Fiore AM, Jaffe DA, Bergmann D, Cuvelier C, Dentener FJ, Duncan BN, Folberth G, Gauss M, Gong S, Hess P, Jonson JE, Keating T, Lupu A, Marmer E, Park R, Schultz MG, Shindell DT, Szopa S, Vivanco MG, Wild O, Zuber A. The influence of foreign vs. North American emissions on surface ozone in the US. Atmos Chem Phys. 2009;9:5027–5042. [Google Scholar]

- Rickard AR, Salisburyg G, Monks PS, Lewis AC, Baugitte S, Bandy BJ, Clemitshaw KC, Penkett SA. Comparison of Measured Ozone Production Efficiencies in the Marine Boundary Layer at Two European Coastal Sites under Different Pollution Regimes. J Atmos Chem. 2002;43:107–134. [Google Scholar]

- Russell AR, Perring AE, Valin LC, Bucsela EJ, Browne EC, Wooldridge PJ, Cohen RC. A high spatial resolution retrieval of NO2 column densities from OMI: method and evaluation. Atmos Chem Phys. 2011;11:8543–8554. doi: 10.5194/acp-11-8543-2011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Russell AR, Valin LC, Cohen RC. Trends in OMI NO2 observations over the United States: effects of emission control technology and the economic recession. Atmos Chem Phys. 2012;12:12197–12209. doi: 10.5194/acp-12-12197-2012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ryerson TB, Williams EJ, Fehsenfeld FC. An efficient photolysis system for fast-response NO2 measurements. J Geophys Res. 2000;105:26447. doi: 10.1029/2000jd900389. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ryerson TB, Buhr MP, Frost GJ, Goldan PD, Holloway JS, Hübler G, Jobson BT, Kuster WC, McKeen SA, Parrish DD, Roberts JM, Sueper DT, Trainer M, Williams J, Fehsenfeld FC. Emissions lifetimes and ozone formation in poewr plant plumes. J Geophys Res. 1998;103(D17):22569–22583. [Google Scholar]

- Sander SP, Abbatt J, Barker JR, Burkholder JB, Friedl RR, Golden DM, Huie RE, Kolb CE, Kurylo MJ, Moortgat GK, Orkin VL, Wine PH. Chemical Kinetics and Photochemical Data for Use in Atmospheric Studies, Evaluation No. 17. Jet Propulsion Laboratory; Pasadena: 2011. JPL Publication 10-6. [Google Scholar]

- Schultz MG, Jacob DJ, Wang Y, Logan JA, Atlas EL, Blake DR, Blake NJ, Bradshaw JD, Browell EV, Fenn MA, Flocke F, Gregory GL, Heikes BG, Sachse GW, Sandholm ST, Shetter RE, Singh HB, Talbot RW. On the origin of tropospheric ozone and NOx over the tropical South Pacific. J Geophys Res. 1999;104:5829. doi: 10.1029/98jd02309. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shetter RE, Muller M. Photolysis frequency measurements using actinic flux spectroradiometry during the PEM -Tropics mission: Instrumentation description and some results. J Geophys Res. 1999;104:5647–5661. doi: 10.1029/98JD01381. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Singh HB, Brune WH, Crawford JH, Jacob DJ, Russell PB. Overview of the summer 2004 Intercontinental Chemical Transport Experiment–North America (INTEX-A) J Geophys Res. 2006;111 doi: 10.1029/2006jd007905. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Squire OJ, Archibald AT, Griffiths PT, Jenkin ME, Smith D, Pyle JA. Influence of isoprene chemical mechanism on modelled changes in tropospheric ozone due to climate and land use over the 21st century. Atmos Chem Phys. 2015;15:5123–5143. doi: 10.5194/acp-15-5123-2015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- St Clair JM, Rivera-Rios JC, Crounse JD, Knap HC, Bates KH, Teng AP, Jorgensen S, Kjaergaard HG, Keutsch FN, Wennberg PO. Kinetics and Products of the Reaction of the First-Generation Isoprene Hydroxy Hydroperoxide (ISOPOOH) with OH. J Phys Chem-US A. 2015 doi: 10.1021/acs.jpca.5b06532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- St Clair JM, McCabe DC, Crounse JD, Steiner U, Wennberg PO. Chemical ionization tandem mass spectromet er for the in situ measurement of methyl hydrogen peroxide. Rev Sci Instrum. 2010;81 doi: 10.1063/1.3480552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stavrakou T, Peeters J, Müller JF. Improved global modelling of HOx recycling in isoprene oxidation: evaluation against the GABRIEL and INTEX-A aircraft campaign measurements. Atmos Chem Phys. 2010;10:9863–9878. doi: 10.5194/acp-10-9863-2010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Toon OB, Maring H, Dibb J, Ferrare R, Jacob DJ, Jensen EJ, Luo ZJ, Mace GG, Pan LL, Pfister L, Rosenlof KH, Redemann J, Reid JS, Singh HB, Yokelson RJ, Minnis P, Chen G, Jucks KW, Pszenny A. Planning, implementation, and scientific goals of the Studies of Emissions and Atmospheric Composition, Clouds, and Climate Coupling by Regional Surveys (SEAC4RS) field mission. J Geophys Res. 2016 in review. [Google Scholar]

- Trainer M, Parrish DD, Buhr MP, Norton RB, Fehsenfeld FC, Anlauf KG, Bottenheim JW, Tang YZ, Wiebe HA, Roberts JM, Tanner RL, Newman L, Bowersox C, Meagher JF, Olszyna KJ, Rodgers MO, Wang T, Berresheim H, Demerjian KL, Roychowdhury UK. Correlation of ozone with NOy in photochemically aged air. J Geophys Res. 1993;98:2917–2925. [Google Scholar]

- Trainer M, Parrish DD, Goldan PD, Roberts J, Fehsenfeld FC. Review of observation-based analysis of the regional factors influencing ozone concentrations. Atmos Environ. 2000;34:2045–2061. [Google Scholar]

- Vinken GCM, Boersma KF, Maasakkers JD, Adon M, Martin RV. Worldwide biogenic soil NOx emissions inferred from OMI NO2 observations. Atmos Chem Phys. 2014;14:10363–10381. doi: 10.5194/acp-14-10363-2014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Walker TW. Applications of Adjoint Modeling in Chemical Composition: Studies of Tropospheric Ozone at Middle and High Northern Latitudes. Graduate Department of Physics, University of Toronto; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Jacob DJ, Logan JA. Global simulation of tropospheric O3-NOx-hydrocarbon chemistry, 1. Model formulation. J Geophys Res. 1998;103:10,727–10,755. [Google Scholar]

- Wesely ML. Parameterization of Surface Resistances to Gaseous Dry Deposition in Regional-Scale Numerical-Models. Atmos Environ. 1989;23(89):1293–1304. 90153–4. doi: 10.1016/0004-6981. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe GM, Crounse JD, Parrish JD, St Clair JM, Beaver MR, Paulot F, Yoon TP, Wennberg PO, Keutsch FN. Photolysis, OH reactivity and ozone reactivity of a proxy for isoprene-derived hydroperoxyenals (HPALDs) Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2012;14:7276–7286. doi: 10.1039/c2cp40388a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe GM, Hanisco TF, Arkinson HL, Bui TP, Crounse JD, Dean-Day J, Goldstein A, Guenther A, Hall SR, Huey G, Jacob DJ, Karl T, Kim PS, Liu X, Marvin MR, Mikoviny T, Misztal PK, Nguyen TB, Peischl J, Pollack I, Ryerson T, St Clair JM, Teng A, Travis KR, Ullman K, Wennberg PO, Wisthaler A. Quantifying Sources and Sinks of Reactive Gases in the Lower Atmosphere using Airborne Flux Observations. Geophys Res Lett. 2015;42:8231–8240. doi: 10.1002/2015GL065839. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xie Y, Paulot F, Carter WPL, Nolte CG, Luecken DJ, Hutzell WT, Wennberg PO, Cohen RC, Pinder RW. Understanding the impact of recent advances in isoprene photooxidation on simulations of regional air quality. Atmos Chem Phys. 2013;13:8439–8455. doi: 10.5194/acp-13-8439-2013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yu K, Jacob DJ, Fisher JA, Kim PS, Marais EA, Miller CC, Travis KR, Zhu L, Yantosca RM, Sulprizio MP, Cohen RC, Dibb JE, Fried A, Mikoviny T, Ryerson TB, Wennberg PO, Wisthaler A. Sensitivity to grid resolution in the ability of a chemical transport model to simulate observed oxidant chemistry under high-isoprene conditions. Atmos Chem Phys. 2016;16:4369–4378. doi: 10.5194/acp-16-4369-2016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]