Abstract

Multiple sclerosis (MS) has long been considered a CD4 T-cell disease, primarily because of the findings that the strongest genetic risk for MS is the major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II locus, and that T cells play a central role in directing the immune response. The importance that the T helper (Th)1 cytokine, interferon γ (IFN-γ), and the Th17 cytokine, interleukin (IL)-17, play in MS pathogenesis is indicated by recent clinical trial data by the enhanced presence of Th1/Th17 cells in central nervous system (CNS) tissue, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), and blood, and by research on animal models of MS, such as experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE). Although the majority of research on MS pathogenesis has centered on the role of effector CD4 T cells, accumulating data suggests that CD8 T cells may play a significant role in the human disease. In fact, in contrast to most animal models, the primary T cell found in the CNS in patients with MS, is the CD8 T cell. As patient-derived effector T cells are also resistant to mechanisms of dominant tolerance such as that induced by interaction with regulatory T cells (Tregs), their reduced response to regulation may also contribute to the unchecked effector T-cell activity in patients with MS. These concepts will be discussed below.

T-CELL BIOLOGY, AN INTRODUCTION

T cells are a major component of the adaptive immune system. During maturation in the thymus, each T cell expresses a specific T-cell receptor (TCR) that arises by random recombination of gene segments enabling expression of a large repertoire of different TCR specificities (Jung and Alt 2004). During their thymic maturation, early TCR+ T cells expressing both CD4 and CD8 major histocompatibility complex (MHC) binding coreceptors are positively selected if they express TCRs that recognize self-MHC proteins resulting in the cell becoming single positive for CD4 or CD8, depending on whether they are restricted to MHC class II or MHC class I, respectively. Subsequent to positive selection, single positive CD4 or CD8 T cells that strongly recognize self-MHC are deleted by negative selection, a process often referred to as central tolerance, which reduces the release of autoreactive T cells to the periphery (Stritesky et al. 2012; Mingueneau et al. 2013). This system of sequential positive and negative selection of TCR specificities is referred to as thymic education, and ultimately produces mature T cells that are activated by recognizing foreign peptides in the context of self-MHC proteins. Thus, thymic selection defines the mature pool of circulating naïve T cells in each individual.

Thymic education does also result in the peripheral release of a small number of self-reactive T cells. One self-reactive T-cell population is the unique population of CD4 FoxP3+ regulatory T cells (Tregs), which express TCRs that strongly react with self-proteins and are positively selected in the thymus (Jordan et al. 2001; Caramalho et al. 2015). These self-reactive FoxP3+ Tregs play a fundamental role in maintaining immune homeostasis and inhibiting autoimmunity, as they suppress the activation of other immune cell types (Sakaguchi et al. 2007). In contrast to these regulatory cells, a low frequency of nonregulatory T cells that can recognize self-antigens are also found in the peripheral pool of T cells, even in healthy individuals. These potentially autoreactive T cells are believed to only recognize the self-antigens with weak TCR signaling, which allows these cells to be controlled by peripheral tolerance mechanisms such as Tregs, but may resist or escape suppression causing autoimmune reactions.

After exiting the thymus, mature T cells continuously recirculate in the peripheral blood and lymphatic system in search of their antigen (Fink and Hendricks 2011). The mature T cells that have not yet encountered their cognate antigen are referred to as naïve T cells. When the naïve TCR interacts with a cell presenting its activating antigen, a cascade event of signal transduction is set into motion that ultimately causes the T cell to differentiate into a specific type of effector T cell. During this process, some of the activated T cells go on to become memory cells that are quickly reactivated when an antigen is reencountered. The nature of the transition from naïve T cell to functional effector T cell is regulated not only by the interaction of its TCR with antigen/MHC, but also by its interaction with costimulatory molecules and the types of cytokines produced by the antigen-presenting cell (APC) (Kaiko et al. 2008). This stimulating milieu can polarize naïve T cells into different functional effector subsets that produce distinct cytokines or cell-mediated activity, and have unique associations with specific disease. In general, it has long been known that the CD4 “helper” T cells augment immune activation by releasing specific cytokines when activated by antigen presented on MHC class II molecules, whereas the CD8 “cytotoxic” T cells primarily are responsible for killing cells that present antigen on MHC class I. Although it is important to note that CD8 T cells can secrete cytokines, and a small population of CD4 T cells has been proposed to have cytotoxic activity.

MULTIPLE SCLEROSIS (MS) AS A T-CELL-MEDIATED DISEASE

The autoimmune T-cell hypothesis of MS was suggested by the work of Kabat and colleagues, who showed that immunization of monkeys with myelin antigens from brain extracts of genetically homologous monkeys resulted in spinal cord and brain inflammation similar to the neuropathology of MS (Kabat et al. 1947). This enhanced the original studies by Rivers and colleagues who first showed immune cell infiltrations and demyelinating lesions when Rhesus macaques were injected with normal brain extracts from rabbits by adding the autoimmune component (Rivers et al. 1933; Schwentker and Rivers 1934; Rivers and Schwentker 1935). This model disease, initially designated experimental allergic encephalomyelitis, was then established in a variety of species, including rodents. A milestone was achieved when the adoptive transfer model was developed by Paterson (1960) demonstrating that the disease could be transferred from an immunized rat to a naïve rat by injection of lymph node cells, and removal of the thymus from newborn rats prevented development of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) in later life (Arnason et al. 1962). Later, this model was further refined when intravenous inoculation of T cells reactive only against myelin basic protein led to development of clinical paralysis in syngeneic rats (Ben-Nun et al. 1981). The EAE model serves as the primary model for the development of new therapeutic strategies in MS.

THE ROLE OF DISTINCT POPULATIONS OF EFFECTOR T CELLS IN MS

In MS, lesions containing large infiltrates of immune cells exist in the central nervous system (CNS) and are hallmarks of the disease. These cells show the marked capacity to break down the blood–brain barrier (BBB), enter into the brain parenchyma, and initiate the loss of neuron-protecting oligodendrocytes with subsequent dissection of neuronal axons and ultimately inducing neuronal cell death (Frischer et al. 2009). The disease is believed to begin with the activation of self-reactive effector T cells in the periphery, which cross the BBB into the CNS. Once in the CNS, they are reactivated by local APCs and recruit additional T cells and macrophages to establish the inflammatory lesion. T cells have been found to be present in these CNS infiltrations at early time points in the disease. Most efficacious disease-modifying therapies (DMTs) that reduce relapse rate and lesion activity function by targeting and blocking immune activation and inflammation (Wingerchuk and Carter 2014). Yet, even though many of these DMTs inhibit new lesion formation, the disease usually progresses over time to result in striking neuron loss and brain atrophy (Tauhid et al. 2014). Whether extremely early inhibition of inflammation would have a different outcome is unknown and difficult to test as the disease is believed to often have been ongoing for long periods of time before it is detected.

Strong immune activation in the CNS is believed to be deleterious (Fletcher et al. 2010); thus, immune infiltration and activation in the CNS is usually tightly regulated and limited by the astrocyte biology and endothelial tight junctions that contribute to the BBB, and MHC molecules being lowly expressed on CNS APCs (Harris et al. 2014). Yet, in spite of the limited expression of MHC on brain parenchyma, immune surveillance does occur in the CNS (Williams et al. 1980), as antivirus studies have shown that cells of the CNS do present antigens to CD8 T cells (Pinschewer et al. 2010). This is also supported by findings that in a small number of patients with MS that received natalizumab therapy to block T-cell entry into the CNS, the loss of T cells in the CNS resulted in unchecked potentially lethal reactivation of CNS-resident John Cunningham (JC) virus (Tan and Koralnik 2010).

The strongest genetic risk factors for MS lie within the MHC, with the MHC class II molecule, HLA-DRB*1501, exerting the strongest affect (Barcellos et al. 2003; Sawcer et al. 2005; International Multiple Sclerosis Genetics Consortium et al. 2011). This strongly implicates CD4 T cells in the pathogenesis of MS as MHC class II molecules specifically present peptide antigens to activate CD4 T cells. MHC class I molecules have also been associated with MS where the HLA-A*0301 allele is associated with increased susceptibility (Fogdell-Hahn et al. 2000; Harbo et al. 2004), whereas the HLA-A*0201 allele is associated with protection from the disease (Brynedal et al. 2007; International Multiple Sclerosis Genetics Consortium et al. 2011). These data point to a role for CD8 T cells in MS, which, in contrast to CD4 T cells, are activated with peptides in the context of MHC class I molecules. Outside of the MHC, a large proportion of risk alleles are associated with T-cell functions again indicating a role for T cells in the disease (for review, see International Multiple Sclerosis Genetics Consortium et al. 2011).

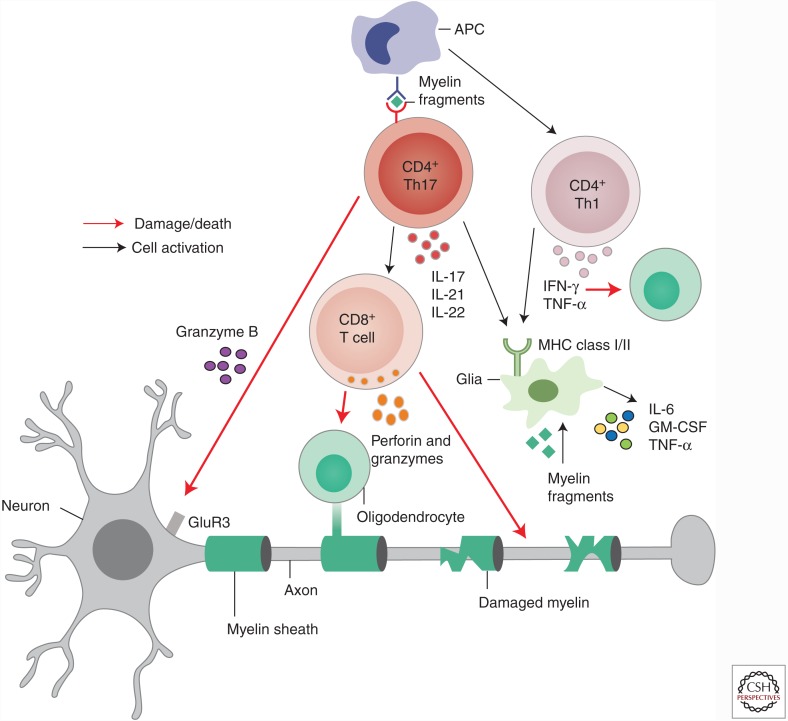

Multiple reports have indicated that defined subsets of both CD4 and CD8 T cells may play unique roles in the disease process. CD8 T cells are predominantly found at the edges of the lesions, and CD4 T cells are found deep in the lesions (Denic et al. 2013). The lesional immune cells are believed to mediate loss of myelin, oligodendrocyte destruction, and axonal damage, all leading to neurologic dysfunction. In response to lesional inflammation, immune-modulatory networks are initiated that limit the immune response and begin repair, often resulting in at least partial remyelination and clinical remission. Yet, in the relapsing form of the disease, immune reactivation occurs as indicated by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and/or as relapse, and the disease progresses in more than 80% of patients. What we currently understand about how the different potential effector T cells contribute to the disease process is discussed below and summarized in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Effector T cells in the central nervous system (CNS). Upon entry into the CNS, CD4 and CD8 effector T cells establish and/or maintain an inflammatory environment contributing to oligodendrocyte death, demyelination, and ultimately neuronal loss. Interleukin (IL)-17- and interferon γ (IFN-γ)-secreting cells activate local glia and antigen-presenting cells (APCs), up-regulating major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I/II molecules on APCs, allowing them to restimulate myelin-reactive effector T cells. IL-17 promotes expression of proinflammatory cytokines IL-6, granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), and tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α). IFN-γ can directly kill oligodendrocytes. IL-17-secreting CD4 and CD8 T cells can secrete granzyme B, which kills neurons through the glutamate receptor (GluR3). CD8 T cells have cytolytic granules, comprising perforin and granzyme molecules, polarized toward demyelinated axons, and will release these for killing of oligodendrocytes and neurons.

MYELIN-REACTIVE CD4 T CELLS

Myelin-reactive T cells have been found in both MS patients and healthy individuals (Burns et al. 1983). In MS patients, myelin-reactive T cells are more likely to be in an activated state, in the memory population, and display a T helper (Th)1 phenotype, whereas myelin-reactive T cells from healthy controls were found to be more naïve (Allegretta et al. 1990; Olsson et al. 1990; Sun et al. 1991; Voskuhl et al. 1993; Lovett-Racke et al. 1998; Burns et al. 1999; Pelfrey et al. 2000). These data indicate that, although these cells are present in healthy controls, in MS patients they have undergone an activation event. Data also suggest that the affinity of the TCRs expressed on patient-derived myelin-binding protein (MBP)-reactive T cells have higher affinity for MBP than those isolated from healthy donors (Goverman 2011). In EAE, disease was ameliorated by delivering altered peptide ligands (APLs) of MBP in which the peptides were mutated for the amino acids that were critical TCR contact sites. To test whether APLs would similarly work in humans, a clinical trial used an APL for myelin basic protein (Hickey and Kimura 1988; Olsson 1992; Dettke et al. 1997; Popko and Baerwald 1999; The Lenercept Multiple Sclerosis Study Group and The University of British Columbia MS/MRI Analysis Group 1999; Aloisi et al. 2000; Goris et al. 2002; Kim et al. 2002; Kantarci et al. 2005; Kebir et al. 2009; Mehling et al. 2010; Hirota et al. 2011; de Weerd and Nguyen 2012; Joffre et al. 2012; Peng et al. 2012; Andreadou et al. 2013; Ottum et al. 2015), which was expected to down-regulate myelin-specific T-cell activation. However, the APL treatment actually exacerbated disease and the clinical trial was halted when patients showed contrast enhancing lesions and 2000-fold expansion of myelin-specific T cells that produced interferon γ (IFN-γ) (Bielekova et al. 2000). Although this clinical trial failed, it directly supports a role for T cells in the exacerbation of MS.

CD4 T CELLS—THE Th1 AND Th17 DICHOTOMY IN MS

The major proinflammatory CD4 T-cell populations associated with autoimmune diseases, including MS, are the Th1 CD4 T cells that secrete IFN-γ and tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) and the Th17 CD4 T cells that secrete interleukin (IL)-17, IL-21, and IL-22. In contrast, atopy and asthma are associated with Th2 CD4 T cells that are induced by IL-4 and produce IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13 (Zhu et al. 2010). Th1 and Th17 CD4 T cells express the unique transcription factors of T-bet (Th1) or RORC2 (Th17), whereas Th2 cells require the activity of the GATA3 transcription factor. In the CNS, both IFN-γ and IL-17 are believed to escalate immune activation by inducing the release of additional proinflammatory mediators, by augmenting antigen presentation, or by directly affecting the viability or function of CNS resident cells. In EAE, studies have indicated that Th17 cells play a central and fundamental role in generating CNS autoimmunity, whereas both IL-17 and IFN-γ have been strongly associated with human disease.

In vitro studies have shown that naïve T cells are induced to become Th17 cells in response to TCR stimulation and IL-6 with transforming growth factor β (TGF-β), whereas naïve T cells are polarized to become Th1 cells in response to IL-12 (Damsker et al. 2010). These in vitro data are suggested to mimic the in vivo polarization induced by cytokines produced by activated accessory cells, producing a proinflammatory cytokine milieu to act on the naïve T cell. IL-6 and IL-12 are primarily produced by APCs of the myeloid lineage such as microglia and infiltrating macrophages; astrocytes can also secrete proinflammatory cytokines potentially contributing to the activation of these cells in the CNS (Choi et al. 2014). In MS, Th1 and Th17 cells are found at increased frequency in CNS lesions and cells from the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) as well as in the peripheral blood. The absolute number of Th1 cells in the CSF and peripheral blood is approximately 10-fold higher than the number of Th17 cells (Brucklacher-Waldert et al. 2009). However, during a clinical relapse, the frequency of Th17 cells was shown to be increased in the CSF of MS patients compared to those in remission or patients with noninflammatory neurologic conditions (Brucklacher-Waldert et al. 2009). This is in direct contrast to a report that enhancement of IFN-γ alone and not IL-17 was associated with relapse (Frisullo et al. 2008). Furthermore, it is important to note that not all IL-17 or IFN-γ-producing cells are pathogenic in MS but rather subsets of each may be initiators, mediators, or exacerbators of disease.

The contrasting roles that IFN-γ and IL-17 appear to play in MS as compared to EAE remains unresolved. Prior to the discovery of Th17 cells, IFN-γ-producing Th1 cells induced by IL-12 were thought to be the critical mediators of EAE because disease was ameliorated on deletion of the IL-12 p40 subunit. However, it was later discovered that p40 is also a component of IL-23, a cytokine that stabilized the Th17 phenotype and IL-17 expression, indicating that loss of p40 would affect Th17 cells as well as Th1 cells (Dardalhon et al. 2008). Furthermore, as the genetic abolition of IFN-γ actually enhanced the severity of EAE, IFN-γ was considered to be protective in the mouse model, potentiating the belief that IL-17 is the mediator of EAE (Axtell and Raman 2012). In contrast, in humans, there is data to support the conclusion that both IFN-γ and IL-17 are pathogenic in MS. The inflammatory nature of IFN-γ-expressing cells in MS has been known since the late 1980s (Traugott and Lebon 1988a,b), and support for the pathogenic role of these cytokines in MS comes from results of clinical trials. In the 1990s, a clinical trial was conducted where IFN-γ was administered to MS patients, which markedly exacerbated disease (Panitch et al. 1987a,b). This directly contradicts the mouse/EAE data where deletion of IFN-γ was deleterious and likely underscores the complexity of the human disease. More recently, clinical trials of IL-17 neutralizing drugs are underway with early reports indicating that the treatment decreases relapse rate in patients with relapsing-remitting MS (RRMS) (Miossec and Kolls 2012). In contrast, an additional clinical trial using a monoclonal antibody against the p40 subunit to block the IL-17 stabilizing cytokine IL-23, was not efficacious in RRMS though it did help in Crohn’s disease and psoriasis (Leonardi et al. 2008; Sandborn et al. 2008; Segal et al. 2008). Explanations put forth to resolve the apparent paradoxical outcome of blocking IL-17 versus blocking the Th17-stabilizing IL-23 include the possibility that the patients enrolled in the trial were too far along in the disease process (Longbrake and Racke 2009), and that different cytokines may play unique roles in disease initiation versus exacerbation (Arellano et al. 2015). Ultimately, it may be that IFN-γ and IL-17 exert stage-specific roles in the disease in man. Furthermore, Th17 cells derived from MS patients and healthy controls express lower levels of FASL compared to Th1 cells, resulting in a lower sensitivity to cell death, potentially allowing for the preferential persistence of these cells and enhancing their contribution to disease in MS (Cencioni et al. 2015).

PATHOLOGY OF Th17 RESPONSES

IL-17 is essential primarily for defense against extracellular bacteria and fungi (O’Quinn et al. 2008), and exerts its activities via a receptor that is ubiquitously expressed (Yao et al. 1997). As such, IL-17 is proposed to specifically alter the activation of astrocytes (Elain et al. 2014). Although the response to IL-17 differs by target cell type, IL-17 promotes immune pathology by synergizing with other cytokines and increasing the secretion of proinflammatory cytokines (IL-6, granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor [GM-CSF], and TNF-α), chemokines (CXCL8, CXCL2, and CCL20), and effector proteins (complement) (Onishi and Gaffen 2010). These effects of IL-17 serve to not only maintain Th17 cells themselves, but also to activate microglia and to recruit neutrophils, macrophages, and lymphocytes (Steinman 2007).

Data from MS patients strongly link IL-17 to disease activity. Microarray analysis detected IL-17 messenger RNA (mRNA) in MS brain lesions (Lock et al. 2002; Montes et al. 2009), whereas active lesions showed increased numbers of IL-17-producing glial cells, CD4, and CD8 T cells, as compared to inactive brain regions (Tzartos et al. 2008). Expression of the IL-17 RORC2 transcription factor is increased in plaques as compared to healthy brain tissue (Lock et al. 2002; Montes et al. 2009). In patient-derived peripheral blood, elevated frequencies of IL-17-producing cells and IL-17 mRNA were detected and positively associated with disease activity (Matusevicius et al. 1999; Durelli et al. 2009). Higher IL-17 mRNA and protein is detected in the blood and CSF of patients at relapse (Matusevicius et al. 1999; Vaknin-Dembinsky et al. 2006; Brucklacher-Waldert et al. 2009; Durelli et al. 2009). Further, enhanced secretion of IL-17 by cells stimulated with MBP was correlated to disease activity by MRI (Hedegaard et al. 2008).

Th17 cell activities may promote disease activity and CNS dysfunction. In vitro, human Th17 cells migrate across models of the BBB more efficiently than Th1 cells and display neurotoxic effects (Kebir et al. 2007). IL-17A levels in the CSF of MS patients are associated with neutrophil expansion and BBB disruption (Kostic et al. 2015). Increased IL-17A levels in the CSF of MS patients also correlates with CSF glutamate levels, which suggests a role for IL-17 in glutamate excitotoxity (Kostic et al. 2014). Th17 cells also secrete IL-21 and IL-22. IL-21, which regulates immune cell activation and survival, may affect the lymphocytes infiltrating acute and chronic active white matter MS lesions (Tzartos et al. 2011). High levels of IL-22, which promotes the disruption of the BBB, has also been detected in CSF and peripheral blood of MS patients (Kebir et al. 2007; Xu et al. 2013; Rolla et al. 2014; Perriard et al. 2015). Importantly, the IL-17A and IL-22 double expressing Th17 cells can also express granzyme B, which has been shown to be cytolytic against human fetal neuron cultures compared to inactivated T cells (Kebir et al. 2007), whereas the extracellular release of granzyme B can kill neurons by targeting the glutamate receptor, GluR3 (Ganor et al. 2007). The secretion of GM-CSF by Th17 cells may play a fundamental role in activating CNS myeloid cells (microglia, macrophages, and dendritic cells) as GM-CSF-deficient Th17 cells are unable to induce EAE (El-Behi et al. 2011).

Reductions in Th17 responses are associated with positive responses to therapy. IFN-β treatment has been shown to inhibit Th17 differentiation in vitro (Durelli et al. 2009; Ramgolam et al. 2009; Sweeney et al. 2011). Patients showing little response to IFN-β showed higher serum levels of IL-17F as compared to patients showing a beneficial response to IFN-β therapy (Axtell et al. 2010). Response to treatment with Fingolimod and dimethyl fumerate has also been suggested to correlate with reduced Th17 responses (Mehling et al. 2010; Peng et al. 2012).

PATHOLOGY OF Th1 RESPONSES

IFN-γ is primarily secreted by T cells and natural killer (NK) cells, although it is also secreted by B cells, APCs, and natural killer T (NKT) cells. Th1 cells strongly secrete IFN-γ and TNF-α; however, the signature cytokine of Th1 cells is IFN-γ. In the CNS, IFN-γ increases the expression of MHC molecules by cells in the CNS (Ottum et al. 2015) and directly affects the activation and viability of other CNS resident cells. Importantly, all CNS cell types are potentially responsive to IFN-γ as its receptor is ubiquitously expressed (de Weerd and Nguyen 2012).

In MS, the levels of IFN-γ have been associated with the frequency of active lesions (Olsson 1992). IFN-γ production by patient-derived T cells was also found to increase before exacerbation of disease activity (Dettke et al. 1997). Genetic polymorphisms of IFN-γ have been associated with susceptibility to MS (Goris et al. 2002; Kantarci et al. 2005). Importantly, whereas it was also shown that IFN-γ can activate microglia to become phagocytic and present antigens, IFN-γ can also directly kill oligodendrocytes (Aloisi et al. 2000). The death of the oligodendrocytes would directly result in the loss of neuronal myelination observed in the CNS of patients (Popko and Baerwald 1999). IFN-γ also induced dendritic retraction and inhibited synapse formation (Kim et al. 2002). By augmenting the expression of MHC molecules, IFN-γ is believed to enhance the antigen-presenting ability of myeloid cells in the meningeal or perivascular sites to restimulate myelin-antigen-specific CD4 or CD8 T. In MS patients, it was shown that myelin-reactive CD8 T cells can be activated by APCs using a process of antigen cross presentation to express exogenous myelin on MHC class I molecules (Joffre et al. 2012). This activation would then license the CD4 or CD8 T cells for subsequent tissue invasion (Hickey and Kimura 1988).

T cells that produce IL-17 and IFN-γ either concurrently or sequentially are also detected in MS and EAE. In EAE, fate-mapping studies indicated that cells that previously produced IL-17, converted to ex-Th17 cells that lack IL-17 but highly express IFN-γ. Importantly, in this study, most CNS-infiltrating Th1 cells appeared to originate from Th17 cells (Hirota et al. 2011). Concomitantly, as T cells expressing both IL-17 and IFN-γ were enriched in MS brain tissue, it suggests that these double positive effector cells may play a role in disease (Kebir et al. 2009).

Last, although it may be surprising, data has also been put forth suggesting that Th1 cells may actually play a protective role in MS. Neutralizing the Th1 cytokine, TNF-α, has been found to initiate myelin autoimmunity in rheumatoid patients (Andreadou et al. 2013) and to exacerbate disease in a clinical trial in MS (The Lenercept Multiple Sclerosis Study Group and the University of British Columbia MS/MRI Analysis Group 1999). This would suggest that TNF-α is somehow protective in MS. IFN-γ has also been shown to stabilize brain endothelial cells of the BBB and enhance their expression of tight-junction proteins (Ni et al. 2014). In direct contrast, IL-17 weakens tight junctions.

CD8 T CELLS

Although much focus on MS pathology has centered on CD4 T cells, data suggest that CD8 T cells play a role in MS. The classic function of activated CD8 effector T cells is to kill target cells by introducing granzymes into the cytosol of target cells by the directional release of granules that contain granzymes and perforin (Bevan 2004). These cytolytic CD8 T cells perform an important antiviral immune surveillance in the CNS, especially as the CNS is a common target of viral infections (Salinas et al. 2010). Again, the importance of CD8 immune surveillance was indicated by the reactivation of the progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML) (JC virus) that occurred in a number of patients when T cells were blocked from entering the CNS with anti-CD49 (natalizumab) (Chalkias et al. 2014). However, in addition to their well-described cytotoxic function, different subsets of CD8 T cells can also secrete IFN-γ and IL-17 (Kish et al. 2009).

Postmortem analysis from acute or RRMS patients indicated that CD8 T cells vastly outnumber CD4 T cells within perivascular cuffs and parenchymal lesions (Traugott et al. 1983; Hauser et al. 1986; Babbe et al. 2000; Junker et al. 2007; Frischer et al. 2009). Within parenchymal lesions, cytotoxic T cells can be visualized with their cytolytic granules polarized toward demyelinated axons, which is believed to be indicative of imminent killing (Neumann et al. 2002). There are also reports of a positive correlation between the abundance of CD8 T cells and the intensity of axonal damage (Bitsch et al. 2000; Kuhlmann et al. 2002). There is an enrichment of activated effector memory or effector (CCR7−, CD45RA−/+) CD8 T cells in the CSF of MS (Jilek et al. 2007). CCR7− T cells can migrate into inflamed tissue and display effector functions (Sallusto et al. 1999; Bromley et al. 2005; Debes et al. 2005). Further, CD8 T cells show oligoclonal expansion in plaques, CSF, and peripheral blood of MS patients (Babbe et al. 2000; Jacobsen et al. 2002; Junker et al. 2007; Friese and Fugger 2009). Altogether, these data suggest an occurrence of antigen-driven activation of CD8 T cells in MS.

The inflammatory environment in the CNS in MS is poised to augment CD8 cytolytic activity. MHC class I molecules present antigens to CD8 T cells to induce their cytotoxic effector function. Most CNS resident cells express MHC class I molecules under inflammatory conditions making them potential targets for CD8 T cells, and an up-regulation of MHC class I molecules is seen early on in MS disease development before demyelination occurs (Hayashi et al. 1988; Ransohoff and Estes 1991; Gobin et al. 2001).

Cytokine-expressing CD8 T cells are also associated with MS. An increase in CD8 T cells expressing IL-17 were found in perivascular spaces in active MS lesions, whereas only rare IL-17 positive cells were found at inactive lesions (Tzartos et al. 2008). These IL-17-producing CD8 T cells are all contained within a CD161high subset of CD8 cells (Annibali et al. 2011). In blood, even though myelin-specific CD8 T cells lines could be derived from MS patients as well as healthy controls (Tsuchida et al. 1994; Dressel et al. 1997; Honma et al. 1997; Crawford et al. 2004), a higher frequency of CD8 T cells recognizing myelin proteins has been reported in MS patients (Crawford et al. 2004; Zang et al. 2004), although there remains controversy (Berthelot et al. 2008).

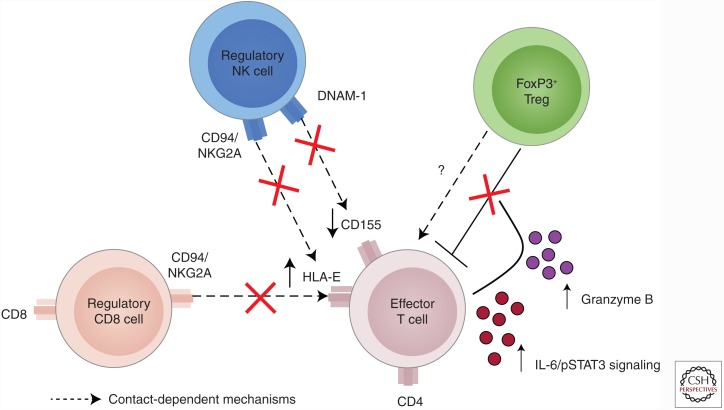

EFFECTOR CELLS EXHIBIT MECHANISMS OF RESISTANCE TO REGULATION

Tregs represent a fundamental regulatory mechanism to maintain immune homeostasis. Studies performed in the EAE model show that Treg-mediated suppression is absolutely required to recover from peak disease activity. A number of reports studying Tregs from patients with MS indicated that patient-derived Treg suppression was significantly less effective than the suppression induced by healthy donor Tregs. A significant reason for the reduced suppression by MS-derived cells is that the T cells isolated from patients with MS are resistant to Treg suppression. While Treg suppression in MS is discussed in another article in this collection, we briefly discuss how the effector cells appear to resist Treg suppression (Fig. 2) (Dressel 1997).

Figure 2.

Effector T-cell mechanisms of resistance to regulation in multiple sclerosis (MS). Effector T cells can escape regulation by regulatory cells via a number of different mechanisms. Up-regulation of HLA-E on the surface of CD4 effector T cells interacts with the CD94/NKG2A inhibitory molecule on regulatory CD8 cells or regulatory natural killer (NK) cells to resist suppression. Further, down-regulation of CD155 and a concomitant decrease in DNAM-1 on the surface of NK cells also allows effector T cells to escape NK-mediated regulation. Increased interleukin (IL)-6 signaling and activation of STAT3 as well as secretion of granzyme B inhibits the capacity of CD4 FoxP3+ regulatory T cells (Tregs) to suppress effector T cells.

Both IL-6 (Schneider et al. 2013) and nonlytic, extracellular secreted granzyme B (Bhela et al. 2015) have been found to inhibit the capacity of Tregs to suppress cells isolated from patients with MS. It is of note that IL-6 is induced by IL-17, and granzyme B has been shown to be a component of the pathogenic Th17 signature and secreted in a markedly increased fashion by patient- versus healthy donor-derived CD4 T cells. In addition to these two mechanisms of resistance that have been shown to be active in MS, Treg function is known to be inactivated by Toll-like receptor (TLR) signals, and by IL-7, IL-18, IL-15, and TNF-α cytokines (Walker 2009). Treg resistance has been described in type 1 diabetes (Lawson et al. 2008; Schneider et al. 2008), psoriasis, rheumatoid arthritis, juvenile idiopathic arthritis, and systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) (Haufe et al. 2011; Wehrens et al. 2011).

In addition to escaping suppression from CD4 FoxP3 Tregs, effector T cells also resist suppression by CD8 Tregs and regulatory NK cells. CD8 CD25+ Tregs recognize and lyse activated myelin-specific CD4 cells (Baughman et al. 2011). This mechanism, which is dependent on HLA-E, a nonclassical MHC class I molecule, is up-regulated in white matter lesions in MS patients (Durrenberger et al. 2012). CD94/NKG2 was found to be significantly elevated on CD8 T cells during a relapse (Correale and Villa 2008). HLA-E can interact with CD94/NKG2 and inhibits the cytotoxic killing of pathogenic CD4 T cells (Correale and Villa 2008). Up-regulation of HLA-E on CD4 T cells also allows resistance to CD56bright CD16dim/− NK cells, again through CD94/NKG2 (Nielsen et al. 2012). Further, effector T cells may escape NK-cell-mediated lysis by down-modulating CD155, the ligand for DNAM-1, after activation with a concomitant decrease in DNAM-1 NK cells (Gross et al. 2016).

Thus, it appears that the chronic activation of the immune system has resulted in or contributed to an imbalance in homeostatic immune networks and results in poor regulation of proinflammatory effector T cells.

Footnotes

Editors: Howard L. Weiner and Vijay K. Kuchroo

Additional Perspectives on Multiple Sclerosis available at www.perspectivesinmedicine.org

REFERENCES

- Allegretta M, Nicklas JA, Sriram S, Albertini RJ. 1990. T cells responsive to myelin basic protein in patients with multiple sclerosis. Science 247: 718–721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aloisi F, Ria F, Adorini L. 2000. Regulation of T-cell responses by CNS antigen-presenting cells: Different roles for microglia and astrocytes. Immunol Today 21: 141–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreadou E, Kemanetzoglou E, Brokalaki C, Evangelopoulos ME, Kilidireas C, Rombos A, Stamboulis E. 2013. Demyelinating disease following anti-TNFa treatment: A causal or coincidental association? Report of four cases and review of the literature. Case Rep Neurol Med 2013: 671935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Annibali V, Ristori G, Angelini DF, Serafini B, Mechelli R, Cannoni S, Romano S, Paolillo A, Abderrahim H, Diamantini A, et al. 2011. CD161highCD8+ T cells bear pathogenetic potential in multiple sclerosis. Brain 134: 542–554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arellano G, Ottum PA, Reyes LI, Burgos PI, Naves R. 2015. Stage-specific role of interferon-γ in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis and multiple sclerosis. Front Immunol 6: 492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnason BG, Jankovic BD, Waksman BH, Wennersten C. 1962. Role of the thymus in immune reactions in rats. II: Suppressive effect of thymectomy at birth on reactions of delayed (cellular) hypersensitivity and the circulating small lymphocyte. J Exp Med 116: 177–186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Axtell RC, Raman C. 2012. Janus-like effects of type I interferon in autoimmune diseases. Immunol Rev 248: 23–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Axtell RC, de Jong BA, Boniface K, van der Voort LF, Bhat R, De Sarno P, Naves R, Han M, Zhong F, Castellanos JG, et al. 2010. T helper type 1 and 17 cells determine efficacy of interferon-β in multiple sclerosis and experimental encephalomyelitis. Nat Med 16: 406–412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babbe H, Roers A, Waisman A, Lassmann H, Goebels N, Hohlfeld R, Friese M, Schröder R, Deckert M, Schmidt S, et al. 2000. Clonal expansions of CD8+ T cells dominate the T cell infiltrate in active multiple sclerosis lesions as shown by micromanipulation and single cell polymerase chain reaction. J Exp Med 192: 393–404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barcellos LF, Oksenberg JR, Begovich AB, Martin ER, Schmidt S, Vittinghoff E, Goodin DS, Pelletier D, Lincoln RR, Bucher P, et al. 2003. HLA-DR2 dose effect on susceptibility to multiple sclerosis and influence on disease course. Am J Hum Genet 72: 710–716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baughman EJ, Mendoza JP, Ortega SB, Ayers CL, Greenberg BM, Frohman EM, Karandikar NJ. 2011. Neuroantigen-specific CD8+ regulatory T-cell function is deficient during acute exacerbation of multiple sclerosis. J Autoimmunity 36: 115–124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Nun A, Wekerle H, Cohen IR. 1981. The rapid isolation of clonable antigen-specific T lymphocyte lines capable of mediating autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Eur J Immunol 11: 195–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berthelot L, Laplaud DA, Pettré S, Ballet C, Michel L, Hillion S, Braudeau C, Connan F, Lefrère F, Wiertlewski S, et al. 2008. Blood CD8+ T cell responses against myelin determinants in multiple sclerosis and healthy individuals. Eur J Immunol 38: 1889–1899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bevan MJ. 2004. Helping the CD8+ T-cell response. Nat Rev Immunol 4: 595–602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhela S, Kempsell C, Manohar M, Dominguez-Villar M, Griffin R, Bhatt P, Kivisakk-Webb P, Fuhlbrigge R, Kupper T, Weiner H, et al. 2015. Nonapoptotic and extracellular activity of granzyme B mediates resistance to regulatory T cell (Treg) suppression by HLA-DR-CD25hiCD127lo Tregs in multiple sclerosis and in response to IL-6. J Immunol 194: 2180–2189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bielekova B, Goodwin B, Richert N, Cortese I, Kondo T, Afshar G, Gran B, Eaton J, Antel J, Frank JA, et al. 2000. Encephalitogenic potential of the myelin basic protein peptide (amino acids 83-99) in multiple sclerosis: Results of a phase II clinical trial with an altered peptide ligand. Nat Med 6: 1167–1175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bitsch A, Schuchardt J, Bunkowski S, Kuhlmann T, Bruck W. 2000. Acute axonal injury in multiple sclerosis. Correlation with demyelination and inflammation. Brain 123: 1174–1183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bromley SK, Thomas SY, Luster AD. 2005. Chemokine receptor CCR7 guides T cell exit from peripheral tissues and entry into afferent lymphatics. Nat Immunol 6: 895–901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brucklacher-Waldert V, Stuerner K, Kolster M, Wolthausen J, Tolosa E. 2009. Phenotypical and functional characterization of T helper 17 cells in multiple sclerosis. Brain 132: 3329–3341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brynedal B, Duvefelt K, Jonasdottir G, Roos IM, Akesson E, Palmgren J, Hillert J. 2007. HLA-A confers an HLA-DRB1 independent influence on the risk of multiple sclerosis. PLoS ONE 2: e664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns J, Rosenzweig A, Zweiman B, Lisak RP. 1983. Isolation of myelin basic protein-reactive T-cell lines from normal human blood. Cell Immunol 81: 435–440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns J, Bartholomew B, Lobo S. 1999. Isolation of myelin basic protein-specific T cells predominantly from the memory T-cell compartment in multiple sclerosis. Ann Neurol 45: 33–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caramalho Í, Nunes-Cabaço H, Foxall RB, Sousa AE. 2015. Regulatory T-cell development in the human thymus. Front Immunol 6: 395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cencioni MT, Santini S, Ruocco G, Borsellino G, De Bardi M, Grasso MG, Ruggieri S, Gasperini C, Centonze D, Barilá D, et al. 2015. FAS-ligand regulates differential activation-induced cell death of human T-helper 1 and 17 cells in healthy donors and multiple sclerosis patients. Cell Death Dis 6: e1741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chalkias S, Dang X, Bord E, Stein MC, Kinkel RP, Sloane JA, Donnelly M, Ionete C, Houtchens MK, Buckle GJ, et al. 2014. JC virus reactivation during prolonged natalizumab monotherapy for multiple sclerosis. Ann Neurol 75: 925–934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi SS, Lee HJ, Lim I, Satoh J, Kim SU. 2014. Human astrocytes: Secretome profiles of cytokines and chemokines. PLoS ONE 9: e92325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Correale J, Villa A. 2008. Isolation and characterization of CD8+ regulatory T cells in multiple sclerosis. J Neuroimmunol 195: 121–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crawford MP, Yan SX, Ortega SB, Mehta RS, Hewitt RE, Price DA, Stastny P, Douek DC, Koup RA, Racke MK, et al. 2004. High prevalence of autoreactive, neuroantigen-specific CD8+ T cells in multiple sclerosis revealed by novel flow cytometric assay. Blood 103: 4222–4231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damsker J, Hansen A, Caspi R. 2010. Th1 and Th17 cells: Adversaries and collaborators. Ann NY Acad Sci 1183: 211–221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dardalhon V, Korn T, Kuchroo VK, Anderson AC. 2008. Role of Th1 and Th17 cells in organ-specific autoimmunity. J Autoimmun 31: 252–256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Debes GF, Arnold CN, Young AJ, Krautwald S, Lipp M, Hay JB, Butcher EC. 2005. Chemokine receptor CCR7 required for T lymphocyte exit from peripheral tissues. Nat Immunol 6: 889–894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denic A, Wootla B, Rodriguez M. 2013. CD8+ T cells in multiple sclerosis. Expert Opin Ther Targets 17: 1053–1066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dettke M, Scheidt P, Prange H, Kirchner H. 1997. Correlation between interferon production and clinical disease activity in patients with multiple sclerosis. J Clin Immunol 17: 293–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Weerd NA, Nguyen T. 2012. The interferons and their receptors—Distribution and regulation. Immunol Cell Biol 90: 483–491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dressel A, Chin JL, Sette A, Gausling R, Hollsberg P, Hafler DA. 1997. Autoantigen recognition by human CD8 T cell clones: Enhanced agonist response induced by altered peptide ligands. J Immunol 159: 4943–4951. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durelli L, Conti L, Clerico M, Boselli D, Contessa G, Ripellino P, Ferrero B, Eid P, Novelli F. 2009. T-helper 17 cells expand in multiple sclerosis and are inhibited by interferon-β. Ann Neurol 65: 499–509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durrenberger PF, Webb LV, Sim MJ, Nicholas RS, Altmann DM, Boyton RJ. 2012. Increased HLA-E expression in white matter lesions in multiple sclerosis. Immunology 137: 317–325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elain G, Jeanneau K, Rutkowska A, Mir AK, Dev KK. 2014. The selective anti-IL17A monoclonal antibody secukinumab (AIN457) attenuates IL17A-induced levels of IL6 in human astrocytes. Glia 62: 725–735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Behi M, Ciric B, Dai H, Yan Y, Cullimore M, Safavi F, Zhang GX, Dittel BN, Rostami A. 2011. The encephalitogenicity of TH17 cells is dependent on IL-1- and IL-23-induced production of the cytokine GM-CSF. Nat Immunol 12: 568–575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fink PJ, Hendricks DW. 2011. Post-thymic maturation: Young T cells assert their individuality. Nat Rev Immunol 11: 544–549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher JM, Lalor SJ, Sweeney CM, Tubridy N, Mills KH. 2010. T cells in multiple sclerosis and experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Clin Exp Immunol 162: 1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fogdell-Hahn A, Ligers A, Gronning M, Hillert J, Olerup O. 2000. Multiple sclerosis: A modifying influence of HLA class I genes in an HLA class II associated autoimmune disease. Tissue Antigens 55: 140–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friese MA, Fugger L. 2009. Pathogenic CD8+ T cells in multiple sclerosis. Ann Neurol 66: 132–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frischer JM, Bramow S, Dal-Bianco A, Lucchinetti CF, Rauschka H, Schmidbauer M, Laursen H, Sorensen PS, Lassmann H. 2009. The relation between inflammation and neurodegeneration in multiple sclerosis brains. Brain 132: 1175–1189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frisullo G, Nociti V, Iorio R, Patanella AK, Marti A, Caggiula M, Mirabella M, Tonali PA, Batocchi AP. 2008. IL17 and IFNγ production by peripheral blood mononuclear cells from clinically isolated syndrome to secondary progressive multiple sclerosis. Cytokine 44: 22–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganor Y, Teichberg VI, Levite M. 2007. TCR activation eliminates glutamate receptor GluR3 from the cell surface of normal human T cells, via an autocrine/paracrine granzyme B-mediated proteolytic cleavage. J Immunol 178: 683–692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gobin SJ, Montagne L, Van Zutphen M, Van Der Valk P, Van Den Elsen PJ, De Groot CJ. 2001. Upregulation of transcription factors controlling MHC expression in multiple sclerosis lesions. Glia 36: 68–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goris A, Heggarty S, Marrosu MG, Graham C, Billiau A, Vandenbroeck K. 2002. Linkage disequilibrium analysis of chromosome 12q14-15 in multiple sclerosis: Delineation of a 118-kb interval around interferon-γ (IFNG) that is involved in male versus female differential susceptibility. Genes Immunity 3: 470–476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goverman JM. 2011. Immune tolerance in multiple sclerosis. Immunol Rev 241: 228–240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross CC, Schulte-Mecklenbeck A, Rünzi A, Kuhlmann T, Posevitz-Fejfár A, Schwab N, Schneider-Hohendorf T, Herich S, Held K, Konjević M, et al. 2016. Impaired NK-mediated regulation of T-cell activity in multiple sclerosis is reconstituted by IL-2 receptor modulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci 113: E2973–E2982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harbo HF, Lie BA, Sawcer S, Celius EG, Dai KZ, Oturai A, Hillert J, Lorentzen AR, Laaksonen M, Myhr KM, et al. 2004. Genes in the HLA class I region may contribute to the HLA class II-associated genetic susceptibility to multiple sclerosis. Tissue Antigens 63: 237–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris MG, Hulseberg P, Ling C, Karman J, Clarkson BD, Harding JS, Zhang M, Sandor A, Christensen K, Nagy A, et al. 2014. Immune privilege of the CNS is not the consequence of limited antigen sampling. Sci Rep 4: 4422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haufe S, Haug M, Schepp C, Kuemmerle-Deschner J, Hansmann S, Rieber N, Tzaribachev N, Hospach T, Maier J, Dannecker GE, et al. 2011. Impaired suppression of synovial fluid CD4+CD25− T cells from patients with juvenile idiopathic arthritis by CD4+CD25+ Treg cells. Arthritis Rheum 63: 3153–3162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauser SL, Bhan AK, Gilles F, Kemp M, Kerr C, Weiner HL. 1986. Immunohistochemical analysis of the cellular infiltrate in multiple sclerosis lesions. Ann Neurol 19: 578–587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi T, Morimoto C, Burks JS, Kerr C, Hauser SL. 1988. Dual-label immunocytochemistry of the active multiple sclerosis lesion: Major histocompatibility complex and activation antigens. Ann Neurol 24: 523–531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedegaard CJ, Krakauer M, Bendtzen K, Lund H, Sellebjerg F, Nielsen CH. 2008. T helper cell type 1 (Th1), Th2 and Th17 responses to myelin basic protein and disease activity in multiple sclerosis. Immunology 125: 161–169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hickey WF, Kimura H. 1988. Perivascular microglial cells of the CNS are bone marrow-derived and present antigen in vivo. Science 239: 290–292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirota K, Duarte JH, Veldhoen M, Hornsby E, Li Y, Cua DJ, Ahlfors H, Wilhelm C, Tolaini M, Menzel U, et al. 2011. Fate mapping of IL-17-producing T cells in inflammatory responses. Nat Immunol 12: 255–263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honma K, Parker KC, Becker KG, McFarland HF, Coligan JE, Biddison WE. 1997. Identification of an epitope derived from human proteolipid protein that can induce autoreactive CD8+ cytotoxic T lymphocytes restricted by HLA-A3: Evidence for cross-reactivity with an environmental microorganism. J Neuroimmunol 73: 7–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- International Multiple Sclerosis Genetics Consortium; Wellcome Trust Case Control Consortium 2; Sawcer S, Hellenthal G, Pirinen M, Spencer CC, Patsopoulos NA, Moutsianas L, Dilthey A, Su Z, et al. 2011. Genetic risk and a primary role for cell-mediated immune mechanisms in multiple sclerosis. Nature 476: 214–219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobsen M, Cepok S, Quak E, Happel M, Gaber R, Ziegler A, Schock S, Oertel WH, Sommer N, Hemmer B. 2002. Oligoclonal expansion of memory CD8+ T cells in cerebrospinal fluid from multiple sclerosis patients. Brain 125: 538–550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jilek S, Schluep M, Rossetti AO, Guignard L, Le Goff G, Pantaleo G, Du Pasquier RA. 2007. CSF enrichment of highly differentiated CD8+ T cells in early multiple sclerosis. Clin Immunol 123: 105–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joffre OP, Segura E, Savina A, Amigorena S. 2012. Cross-presentation by dendritic cells. Nat Rev Immunol 12: 557–569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jordan MS, Boesteanu A, Reed AJ, Petrone AL, Holenbeck AE, Lerman MA, Naji A, Caton AJ. 2001. Thymic selection of CD4+ CD25+ regulatory T cells induced by an agonist self-peptide. Nat Immunol 2: 301–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung D, Alt FW. 2004. Unraveling V(D)J recombination. Cell 116: 299–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Junker A, Ivanidze J, Malotka J, Eiglmeier I, Lassmann H, Wekerle H, Meinl E, Hohlfeld R, Dornmair K. 2007. Multiple sclerosis: T-cell receptor expression in distinct brain regions. Brain 130: 2789–2799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabat EA, Wolf A, Bezer AE. 1947. The rapid production of acute disseminated encephalomyelitis in rhesus monkeys by injection of heterologous and homologous brain tissue with adjuvants. J Exp Med 85: 117–130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaiko GE, Horvat JC, Beagley KW, Hansbro PM. 2008. Immunological decision-making: How does the immune system decide to mount a helper T-cell response? Immunology 123: 326–338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kantarci OH, Goris A, Hebrink DD, Heggarty S, Cunningham S, Alloza I, Atkinson EJ, de Andrade M, McMurray CT, Graham CA, et al. 2005. IFNG polymorphisms are associated with gender differences in susceptibility to multiple sclerosis. Genes Immun 6: 153–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kebir H, Kreymborg K, Ifergan I, Dodelet-Devillers A, Cayrol R, Bernard M, Giuliani F, Arbour N, Becher B, Prat A. 2007. Human TH17 lymphocytes promote blood–brain barrier disruption and central nervous system inflammation. Nat Med 13: 1173–1175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kebir H, Ifergan I, Alvarez JI, Bernard M, Poirier J, Arbour N, Duquette P, Prat A. 2009. Preferential recruitment of interferon-γ-expressing TH17 cells in multiple sclerosis. Ann Neurol 66: 390–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim IJ, Beck HN, Lein PJ, Higgins D. 2002. Interferon γ induces retrograde dendritic retraction and inhibits synapse formation. J Neurosci 22: 4530–4539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kish DD, Li X, Fairchild RL. 2009. CD8 T cells producing IL-17 and IFN-γ initiate the innate immune response required for responses to antigen skin challenge. J Immunol 182: 5949–5959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kostic M, Dzopalic T, Zivanovic S, Zivkovic N, Cvetanovic A, Stojanovic I, Vojinovic S, Marjanovic G, Savic V, Colic M. 2014. IL-17 and glutamate excitotoxicity in the pathogenesis of multiple sclerosis. Scand J Immunol 79: 181–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kostic M, Stojanovic I, Marjanovic G, Zivkovic N, Cvetanovic A. 2015. Deleterious versus protective autoimmunity in multiple sclerosis. Cell Immunol 296: 122–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhlmann T, Lingfeld G, Bitsch A, Schuchardt J, Bruck W. 2002. Acute axonal damage in multiple sclerosis is most extensive in early disease stages and decreases over time. Brain 125: 2202–2212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawson JM, Tremble J, Dayan C, Beyan H, Leslie RD, Peakman M, Tree TI. 2008. Increased resistance to CD4+ CD25hi regulatory T cell-mediated suppression in patients with type 1 diabetes. Clin Exp Immunol 154: 353–359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonardi CL, Kimball AB, Papp KA, Yeilding N, Guzzo C, Wang Y, Li S, Dooley LT, Gordon KB; PHOENIX 1 study investigators. 2008. Efficacy and safety of ustekinumab, a human interleukin-12/23 monoclonal antibody, in patients with psoriasis: 76-week results from a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial (PHOENIX 1). Lancet 371: 1665–1674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lock C, Hermans G, Pedotti R, Brendolan A, Schadt E, Garren H, Langer-Gould A, Strober S, Cannella B, Allard J, et al. 2002. Gene-microarray analysis of multiple sclerosis lesions yields new targets validated in autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Nat Med 8: 500–508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longbrake EE, Racke MK. 2009. Why did IL-12/IL-23 antibody therapy fail in multiple sclerosis? Exp Rev Neurotherapeut 9: 319–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovett-Racke AE, Trotter JL, Lauber J, Perrin PJ, June CH, Racke MK. 1998. Decreased dependence of myelin basic protein-reactive T cells on CD28-mediated costimulation in multiple sclerosis patients. A marker of activated/memory T cells. J Clin Invest 101: 725–730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matusevicius D, Kivisäkk P, He B, Kostulas N, Ozenci V, Fredrikson S, Link H. 1999. Interleukin-17 mRNA expression in blood and CSF mononuclear cells is augmented in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler 5: 101–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehling M, Lindberg R, Raulf F, Kuhle J, Hess C, Kappos L, Brinkmann V. 2010. Th17 central memory T cells are reduced by FTY720 in patients with multiple sclerosis. Neurology 75: 403–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mingueneau M, Kreslavsky T, Gray D, Heng T, Cruse R, Ericson J, Bendall S, Spitzer MH, Nolan GP, Kobayashi K, et al. 2013. The transcriptional landscape of αβ T cell differentiation. Nat Immunol 14: 619–632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miossec P, Kolls JK. 2012. Targeting IL-17 and TH17 cells in chronic inflammation. Nat Rev Drug Discov 11: 763–776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montes M, Zhang X, Berthelot L, Laplaud DA, Brouard S, Jin J, Rogan S, Armao D, Jewells V, Soulillou JP, et al. 2009. Oligoclonal myelin-reactive T-cell infiltrates derived from multiple sclerosis lesions are enriched in Th17 cells. Clin Immunol 130: 133–144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neumann H, Medana IM, Bauer J, Lassmann H. 2002. Cytotoxic T lymphocytes in autoimmune and degenerative CNS diseases. Trends Neurosci 25: 313–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ni C, Wang C, Zhang J, Qu L, Liu X, Lu Y, Yang W, Deng J, Lorenz D, Gao P, et al. 2014. Interferon-γ safeguards blood–brain barrier during experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Am J Pathol 184: 3308–3320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen N, Ødum N, Ursø B, Lanier LL, Spee P. 2012. Cytotoxicity of CD56bright NK cells towards autologous activated CD4+ T cells is mediated through NKG2D, LFA-1 and TRAIL and dampened via CD94/NKG2A. PLoS ONE 7: e31959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsson T. 1992. Cytokines in neuroinflammatory disease: Role of myelin autoreactive T cell production of interferon-γ. J Neuroimmunol 40: 211–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsson T, Zhi WW, Höjeberg B, Kostulas V, Jiang YP, Anderson G, Ekre HP, Link H. 1990. Autoreactive T lymphocytes in multiple sclerosis determined by antigen-induced secretion of interferon-γ. J Clin Invest 86: 981–985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onishi RM, Gaffen SL. 2010. Interleukin-17 and its target genes: Mechanisms of interleukin-17 function in disease. Immunology 129: 311–321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Quinn DB, Palmer MT, Lee YK, Weaver CT. 2008. Emergence of the Th17 pathway and its role in host defense. Adv Immunol 99: 115–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ottum PA, Arellano G, Reyes LI, Iruretagoyena M, Naves R. 2015. Opposing roles of interferon-γ on cells of the central nervous system in autoimmune neuroinflammation. Front Immunol 6: 539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panitch HS, Hirsch RL, Haley AS, Johnson KP. 1987a. Exacerbations of multiple sclerosis in patients treated with γ interferon. Lancet 1: 893–895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panitch HS, Hirsch RL, Schindler J, Johnson KP. 1987b. Treatment of multiple sclerosis with γ interferon: Exacerbations associated with activation of the immune system. Neurology 37: 1097–1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paterson PY. 1960. Transfer of allergic encephalomyelitis in rats by means of lymph node cells. J Exp Med 111: 119–136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelfrey CM, Rudick RA, Cotleur AC, Lee JC, Tary-Lehmann M, Lehmann PV. 2000. Quantification of self-recognition in multiple sclerosis by single-cell analysis of cytokine production. J Immunol 165: 1641–1651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng H, Guerau-de-Arellano M, Mehta VB, Yang Y, Huss DJ, Papenfuss TL, Lovett-Racke AE, Racke MK. 2012. Dimethyl fumarate inhibits dendritic cell maturation via nuclear factor κB (NF-κB) and extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1 and 2 (ERK1/2) and mitogen stress-activated kinase 1 (MSK1) signaling. J Biol Chem 287: 28017–28026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perriard G, Mathias A, Enz L, Canales M, Schluep M, Gentner M, Schaeren-Wiemers N, Du Pasquier RA. 2015. Interleukin-22 is increased in multiple sclerosis patients and targets astrocytes. J Neuroinflammation 12: 119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinschewer DD, Schedensack M, Bergthaler A, Horvath E, Brück W, Löhning M, Merkler D. 2010. T cells can mediate viral clearance from ependyma but not from brain parenchyma in a major histocompatibility class I- and perforin-independent manner. Brain 133: 1054–1066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popko B, Baerwald KD. 1999. Oligodendroglial response to the immune cytokine interferon γ. Neurochem Res 24: 331–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramgolam VS, Sha Y, Jin J, Zhang X, Markovic-Plese S. 2009. IFN-β inhibits human Th17 cell differentiation. J Immunol 183: 5418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ransohoff RM, Estes ML. 1991. Astrocyte expression of major histocompatibility complex gene products in multiple sclerosis brain tissue obtained by stereotactic biopsy. Arch Neurol 48: 1244–1246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivers TM, Schwentker FF. 1935. Encephalomyelitis accompanied by myelin destruction experimentally produced in monkeys. J Exp Med 61: 689–702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivers TM, Sprunt DH, Berry GP. 1933. Observations on attempts to produce acute disseminated encephalomyelitis in monkeys. J Exp Med 58: 39–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rolla S, Bardina V, De Mercanti S, Quaglino P, De Palma R, Gned D, Brusa D, Durelli L, Novelli F, Clerico M. 2014. Th22 cells are expanded in multiple sclerosis and are resistant to IFN-β. J Leukocyte Biol 96: 1155–1164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakaguchi S, Wing K, Miyara M. 2007. Regulatory T cells—A brief history and perspective. Eur J Immunol 37: S1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salinas S, Schiavo G, Kremer EJ. 2010. A hitchhiker’s guide to the nervous system: The complex journey of viruses and toxins. Nat Rev Microbiol 8: 645–655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sallusto F, Lenig D, Forster R, Lipp M, Lanzavecchia A. 1999. Two subsets of memory T lymphocytes with distinct homing potentials and effector functions. Nature 401: 708–712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandborn WJ, Feagan BG, Fedorak RN, Scherl E, Fleisher MR, Katz S, Johanns J, Blank M, Rutgeerts P; Ustekinumab Crohn’s Disease Study Group. 2008. A randomized trial of ustekinumab, a human interleukin-12/23 monoclonal antibody, in patients with moderate-to-severe Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology 135: 1130–1141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawcer S, Ban M, Maranian M, Yeo TW, Compston A, Kirby A, Daly MJ, De Jager PL, Walsh E, Lander ES, et al. 2005. A high-density screen for linkage in multiple sclerosis. Am J Hum Genet 77: 454–467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider A, Rieck M, Sanda S, Pihoker C, Greenbaum C, Buckner JH. 2008. The effector T cells of diabetic subjects are resistant to regulation via CD4+ FOXP3+ regulatory T cells. J Immunol 181: 7350–7355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider A, Long SA, Cerosaletti K, Ni CT, Samuels P, Kita M, et al. 2013. In active relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis, effector T cell resistance to adaptive Tregs involves IL-6–mediated signaling. Sci Transl Med 5: 170ra15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwentker FF, Rivers TM. 1934. The antibody response of rabbits to injections of emulsions and extracts of homologous brain. J Exp Med 60: 559–574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segal BM, Constantinescu CS, Raychaudhuri A, Kim L, Fidelus-Gort R, Kasper LH; Ustekinumab MS Investigators. 2008. Repeated subcutaneous injections of IL12/23 p40 neutralising antibody, ustekinumab, in patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: A phase II, double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomised, dose-ranging study. Lancet Neurol 7: 796–804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinman L. 2007. A brief history of TH17, the first major revision in the TH1/TH2 hypothesis of T cell-mediated tissue damage. Nat Med 13: 139–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stritesky GL, Jameson SC, Hogquist KA. 2012. Selection of self-reactive T cells in the thymus. Annu Rev Immunol 30: 95–114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun JB, Olsson T, Wang WZ, Xiao BG, Kostulas V, Fredrikson S, Ekre HP, Link H. 1991. Autoreactive T and B cells responding to myelin proteolipid protein in multiple sclerosis and controls. Eur J Immunol 21: 1461–1468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sweeney CM, Lonergan R, Basdeo SA, Kinsella K, Dungan LS, Higgins SC, Kelly PJ, Costelloe L, Tubridy N, Mills KH, et al. 2011. IL-27 mediates the response to IFN-β therapy in multiple sclerosis patients by inhibiting Th17 cells. Brain Behav Immun 25: 1170–1181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan CS, Koralnik IJ. 2010. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy and other disorders caused by JC virus: Clinical features and pathogenesis. Lancet Neurol 9: 425–437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tauhid S, Neema M, Healy BC, Weiner HL, Bakshi R. 2014. MRI phenotypes based on cerebral lesions and atrophy in patients with multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Sci 346: 250–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Lenercept Multiple Sclerosis Study Group and The University of British Columbia MS/MRI Analysis Group. 1999. TNF neutralization in MS: Results of a randomized, placebo-controlled multicenter study. Neurology 53: 457–465. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Traugott U, Lebon P. 1988a. Multiple sclerosis: Involvement of interferons in lesion pathogenesis. Ann Neurol 24: 243–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Traugott U, Lebon P. 1988b. Interferon-γ and Ia antigen are present on astrocytes in active chronic multiple sclerosis lesions. J Neuro Sci 84: 257–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Traugott U, Reinherz EL, Raine CS. 1983. Multiple sclerosis. Distribution of T cells, T cell subsets and Ia-positive macrophages in lesions of different ages. J Neuroimmunol 4: 201–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuchida T, Parker KC, Turner RV, McFarland HF, Coligan JE, Biddison WE. 1994. Autoreactive CD8+ T-cell responses to human myelin protein-derived peptides. Proc Natl Acad Sci 91: 10859–10863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tzartos JS, Friese MA, Craner MJ, Palace J, Newcombe J, Esiri MM, Fugger L. 2008. Interleukin-17 production in central nervous system-infiltrating T cells and glial cells is associated with active disease in multiple sclerosis. Am J Pathol 172: 146–155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tzartos JS, Craner MJ, Friese MA, Jakobsen KB, Newcombe J, Esiri MM, Fugger L. 2011. IL-21 and IL-21 receptor expression in lymphocytes and neurons in multiple sclerosis brain. Am J Pathol 178: 794–802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaknin-Dembinsky A, Balashov K, Weiner HL. 2006. IL-23 is increased in dendritic cells in multiple sclerosis and down-regulation of IL-23 by antisense oligos increases dendritic cell IL-10 production. J Immunol 176: 7768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voskuhl RR, Martin R, Bergman C, Dalal M, Ruddle NH, Mcfarland HF. 1993. T helper 1 (TH1) functional phenotype of human myelin basic protein-specific T lymphocytes. Autoimmunity 15: 137–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker LSK. 2009. Regulatory T cells overturned: The effectors fight back. Immunology 126: 466–474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wehrens EJ, Mijnheer G, Duurland CL, Klein M, Meerding J, van Loosdregt J, de Jager W, Sawitzke B, Coffer PJ, Vastert B, et al. 2011. Functional human regulatory T cells fail to control autoimmune inflammation due to PKB/c-akt hyperactivation in effector cells. Blood 118: 3538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams KA, Hart DN, Fabre JW, Morris PJ. 1980. Distribution and quantitation of HLA-ABC and DR (Ia) antigens on human kidney and other tissues. Transplantation 29: 274–279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wingerchuk DM, Carter JL. 2014. Multiple sclerosis: Current and emerging disease-modifying therapies and treatment strategies. Mayo Clin Proc 89: 225–240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu W, Li R, Dai Y, Wu A, Wang H, Cheng C, Qiu W, Lu Z, Zhong X, Shu Y, et al. 2013. IL-22 secreting CD4+ T cells in the patients with neuromyelitis optica and multiple sclerosis. J Neuroimmunol 261: 87–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao Z, Spriggs MK, Derry JM, Strockbine L, Park LS, VandenBos T, Zappone JD, Painter SL, Armiage RJ. 1997. Molecular characterization of the human interleukin (IL)-17 receptor. Cytokine 9: 794–800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zang YC, Li S, Rivera VM, Hong J, Robinson RR, Breitbach WT, Killian J, Zhang JZ. 2004. Increased CD8+ cytotoxic T cell responses to myelin basic protein in multiple sclerosis. J Immunol 172: 5120–5127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu J, Yamane H, Paul WE. 2010. Differentiation of effector CD4 T cell populations. Ann Rev Immunol 28: 445–489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]