Abstract

Background:

Relative risk estimates for long-term ozone () exposure and respiratory mortality from the American Cancer Society Cancer Prevention Study II (ACS CPS-II) cohort have been used to estimate global mortality in adults. Updated relative risk estimates are now available for the same cohort based on an expanded study population with longer follow-up.

Objectives:

We estimated the global burden and spatial distribution of respiratory mortality attributable to long-term exposure in adults of age using updated effect estimates from the ACS CPS-II cohort.

Methods:

We used GEOS-Chem simulations ( grid resolution) to estimate annual exposures, and estimated total respiratory deaths in 2010 that were attributable to long-term annual exposure based on the updated relative risk estimates and minimum risk thresholds set at the minimum or fifth percentile of exposure in the most recent CPS-II analysis. These estimates were compared with attributable mortality based on the earlier CPS-II analysis, using 6-mo average exposures and risk thresholds corresponding to the minimum or fifth percentile of exposure in the earlier study population.

Results:

We estimated 1.04–1.23 million respiratory deaths in adults attributable to exposures using the updated relative risk estimate and exposure parameters, compared with 0.40–0.55 million respiratory deaths attributable to exposures based on the earlier CPS-II risk estimate and parameters. Increases in estimated attributable mortality were larger in northern India, southeast China, and Pakistan than in Europe, eastern United States, and northeast China.

Conclusions:

These findings suggest that the potential magnitude of health benefits of air quality policies targeting , health co-benefits of climate mitigation policies, and health implications of climate change-driven changes in concentrations, are larger than previously thought. https://doi.org/10.1289/EHP1390

Introduction

Ground-level ozone () is formed photochemically in the atmosphere from nitrogen oxides, non-methane volatile organic compounds, methane, and carbon monoxide. Ozone exposure has been associated with a range of health impacts, including mortality (REVIHAAP 2013; U.S. EPA 2013). Relative risk estimates based on prospective data from the American Cancer Society Cancer Prevention Study II (ACS CPS-II) have been applied in previous analyses of the global burden of mortality attributable to long-term air pollution exposures. Jerrett et al. (2009) reported a relative risk estimate for respiratory mortality in association with long-term exposure in the CPS-II cohort (hereafter referred to as J2009), which was subsequently used to derive global estimates of mortality ranging from 0.15 to 0.49 million deaths per year (Anenberg et al. 2010; Fang et al. 2013b; GBD 2013 Risk Factors Collaborators 2015; GBD 2015 Risk Factors Collaborators 2016; Lim et al. 2012; Silva et al. 2013, 2016a). In contrast, global estimates of mortality attributable to fine particulate matter () exposure (from cardiovascular, respiratory, and lung cancer diseases) have been much higher, ranging from 1.6 to 4.2 million per year (Anenberg et al. 2010; Fang et al. 2013b; GBD 2013 Risk Factors Collaborators 2015; GBD 2015 Risk Factors Collaborators 2016; Lim et al. 2012; Silva et al. 2013, 2016a).

Turner et al. (2016) recently reported updated CPS-II cohort estimates of mortality risks associated with long-term exposure (hereafter referred to as T2016). The updated CPS-II estimates are based on a larger study population with longer follow-up (669,046 participants and 237,201 deaths during 1982–2004) (Turner et al. 2016) than the previous estimates (448,850 participants and 118,777 deaths during 1982–2000) (Jerrett et al. 2009). In addition to the differences noted above, the updated risk estimates reflect other changes from the original study, which are described in detail in Table S1. Importantly, there are differences in the exposure metric used in either study; in Jerrett et al. (2009), the summer average daily maximum 1-h concentration was used (average of April–June and July–September values), and in Turner et al. (2016), the annual average daily maximum 8-h concentration was used.

The purpose of the present analysis is to provide estimates of global respiratory mortality attributable to long-term exposure based on the updated T2016 relative risk estimate and exposure metric and compare them with estimates derived using the J2009 relative risk estimate and exposure metric. In addition, we report estimates of ozone-attributable deaths due to COPD mortality specifically.

The evidence from epidemiological and toxicological studies for associations, and causal linkages, between exposure (short- and long-term) and specific health outcomes has been reviewed by the WHO and U.S. EPA (REVIHAAP 2013; U.S. EPA 2013). For respiratory mortality, REVIHAAP (2013) identified three cohort studies that linked long-term exposure and relevant outcomes, including respiratory mortality specifically (Jerrett et al. 2009), COPD mortality (Zanobetti and Schwartz 2011), and cardiopulmonary mortality (Smith et al. 2009b). The U.S. EPA (2013) concluded that there was “likely to be a causal relationship between long-term exposure to and respiratory effects” based on epidemiologic studies of respiratory mortality (Jerrett et al. 2009; Zanobetti and Schwartz 2011), respiratory morbidity (Jacquemin et al. 2012; Lin et al. 2008; Meng et al. 2010; Parker et al. 2009), and toxicological evidence of biologically plausible mechanisms for respiratory effects of , including “pulmonary function decrement and increases in respiratory symptoms, lung inflammation, lung permeability, and airway hyper-responsiveness” (U.S. EPA 2013). Evidence for causal associations of with specific causes of respiratory mortality is more limited, with stronger evidence from studies of short-term and hospital admissions for both COPD and asthma compared with pneumonia (Medina-Ramón et al. 2006; U.S. EPA 2013; Zanobetti and Schwartz 2006), although a recent study reported an association between short-term exposure and hospital visits for pneumonia, as well as COPD (Malig et al. 2016).

Methods

Long-Term Exposure Estimation

Global gridded (, approximately at the equator) hourly concentrations were simulated using the GEOS-Chem Chemical Transport Model (Bey et al. 2001) driven by GEOS-5 meteorological fields for 2010 from the Global Modeling and Assimilation Office, with 47 vertical levels defined from the surface up to 0.01 hPa. Simulations used 2010 anthropogenic emissions from the Hemispheric Transport of Air Pollution version-2 inventory (Janssens-Maenhout et al. 2015). The model also considers additional emissions, described in further detail by Lapina et al. (2014), which include biogenic VOCs, soil , lightning , and monthly biomass burning emissions.

When estimating attributable deaths globally based on the J2009 relative risk estimates, we used an exposure metric that was consistent with the premise of the exposure metric for which the J2009 relative risk estimates were derived. Jerrett et al. (2009) used the average daily maximum 1-h concentration between April and September as the exposure metric in the United States alone, where concentrations are highest in spring and summer months. In other regions, the seasonal pattern of variation is different. To account for variability in the 6-mo period with highest daily maximum 1-h concentrations across regions, we estimated, for each grid, annual maximum 6-mo average daily maximum 1-h (6mDM1h) concentrations. The 6mDM1h metric calculated grid-by-grid accounts for differences in seasonal variation across the globe that affects the timing of the maximum 6-mo concentration (Anenberg et al. 2010; Silva et al. 2013, 2016a). When estimating attributable deaths using the T2016 risk estimates, we used the annual average daily maximum 8-h concentration (ADM8h) for each grid, consistent with the analysis from which the relative risk estimates were derived. For each day, 24 eight-hour rolling mean concentrations were calculated as the average concentration at the start hour and the following 7 h. The maximum of the 24 eight-hour concentrations on each day were selected and averaged across the year to derive the ADM8h concentration in each grid.

Exposure–Response Functions

Mortality attributable to long-term exposure was estimated for 181 countries in 2010 using Equations 1 and 2, consistent with methodologies used to estimate global health impacts of previously (Anenberg et al. 2010; Silva et al. 2013, 2016a):

| [1] |

| [2] |

is the change in mortality attributable to long-term exposure, and was estimated separately for the population in each grid cell covering a particular country. In this study, we estimated for each country in 2010 for respiratory mortality [International Classification of Diseases (ICD)-10 codes: J00–J98], consistent with the causes of death investigated in Jerrett et al. (2009) and Turner et al. (2016), and separately for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) mortality (ICD-10 codes: J19–J46), a subset of respiratory mortality.

Pop. is the exposed population, which was the population in each country of age, estimated from UN Population Division population statistics disaggregated by age for each country (https://esa.un.org/unpd/wpp/DataQuery/) because participants in the ACS CPS-II cohort were required to be over 30 y of age at enrollment. The population was distributed to the grids covering each country using population count data for 2010 from the Gridded Population of the World (GPW) version 3 dataset (CIESIN-FAO-CIAT 2005). is the baseline mortality rate for each cause of death, derived as the ratio of the deaths of people of age from the cause and the number of people in each country of age estimated by the UN Population Division (https://esa.un.org/unpd/wpp/DataQuery/). For each country, the total number of deaths for each disease category (respiratory and COPD) for the population of age in 2010 were from the GBD 2015 estimates derived by the Institute of Health Metrics and Evaluation (GBD 2015 Mortality and Causes of Death Collaborators 2016). Uncertainty in was derived from the confidence intervals (CIs) reported by GBD 2015 Mortality and Causes of Death Collaborators (2016) for the number of deaths from each cause, as described below.

is the effect estimate [natural log of the hazard ratio (HR)] for the association between long-term concentrations and respiratory or COPD mortality (Equation 2). In Jerrett et al. (2009), and Turner et al. (2016), the HRs are reported as the increased hazard of death for a increase in long-term exposure, which is in Equation 2. For J2009, in the main analysis we used the ln-HR for a increase in concentration (6mDM1h metric) from the two-pollutant model adjusted for (; 95% CI: 1.013, 1.067), which has been applied in several previous analyses (Anenberg et al. 2010; Fann et al. 2012; Silva et al. 2013, 2016a; West et al. 2013). For T2016, in the main analysis we used the ln-HR for a increase in concentration (ADM8h metric) from a model adjusted for near-source , regional , and (; 95% CI: 1.08, 1.16). This HR was used to estimate updated long-term respiratory mortality [using two low-concentration cutoffs (LCCs) to reflect uncertainty in the concentration–response relationship below exposure levels in Turner et al. (2016) (see below)]. T2016 relative risk estimates for COPD mortality also were adjusted for (near-source and regional) and [ (95% CI: 1.08, 1.21)].

Finally, is the long-term exposure (estimated using GEOS-Chem model output), expressed relative to a threshold exposure (low-concentration cutoff, or LCC), below which we assume there is no effect of exposure on mortality. The specific LCCs used corresponded to the minimum exposure or the fifth percentile of exposure in the respective ACS CPS-II population on which each set of relative risk estimates (J2009 or T2016) were based because the validity of each risk estimate is uncertain for exposures below the actual levels experienced by each population. For analyses based on J2009 relative risk estimates and the 6mDM1h ozone exposure metric, LCCs for the minimum and fifth percentiles of exposure were set at and , respectively; for analyses using T2016 relative risk estimates and the ADM8h exposure metric, corresponding LCCs were set at and . For each grid cell, was calculated from the GEOS-Chem derived concentration (O3_GC) as

| [3] |

To derive central estimates of long-term attributable respiratory, and COPD deaths for individual countries, we applied Equation 1 for the population of age assigned to each grid cell covering the country, using the central estimates of and the national baseline mortality rate (). To account for uncertainty in the relative risk estimate () and baseline mortality rates (), we sampled 1,000 estimates of and from normal distributions based on the 95% CIs for each variable, applied each resulting value to Equation 1 to derive 1,000 estimates of long-term attributable deaths, and used the resulting distribution to derive 95% CIs for attributable mortality in each grid cell. Estimates for individual grids were summed to derive national, regional, and global estimates, assuming dependence among the gridded estimates.

Sensitivity analyses were performed to estimate long-term mortality using T2016 relative risk estimates derived using a single-pollutant model that did not adjust for near-source , regional , or exposures [ (95% CI: 1.10, 1.18)]. In addition, we also performed analyses using methods comparable with those used in previous studies to estimate mortality. This allowed assessment of the consistency of results obtained in those studies, with comparable estimates using the exposure, baseline mortality, and population data used in this study. To make a direct comparison with the Global Burden of Disease (GBD) analyses, we also further estimated long-term deaths using comparable methods. Specifically, GBD estimated long-term deaths associated with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) only, using the maximum 3-mo average daily maximum 1-h concentration, and the single-pollutant J2009 relative risk estimate [1.029 (95% CI 1.010, 1.048)] that was derived for total respiratory mortality (GBD 2013 Risk Factors Collaborators 2015; GBD 2015 Risk Factors Collaborators 2016; Lim et al. 2012).

Results

Globally, exposure ranged between and when quantified using the 6-mo daily maximum 1-h concentration (6mDMA1) relevant for the J2009 relative risk estimates, and between and when quantified as the annual daily maximum 8-h concentration (ADMA8) relevant for the T2016 relative risk estimates (Table 1; see also Figure S1). Both exposure metrics were elevated across Asia (particularly India and China) compared with other regions (Table 1).

Table 1.

Range of concentrations (ppb) in grids covering world regions and selected countries estimated from GEOS-chem model simulations.

| Region | Metric | Minimum | 5th percentile | 25th percentile | Median | 75th percentile | 95th percentile | Maximum |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Asia | 6mDMA1 | 13.6 | 26.5 | 50.4 | 59.2 | 66.1 | 75.9 | 84.0 |

| ADMA8 | 11.7 | 23.5 | 42.4 | 50.4 | 57.2 | 66.1 | 72.6 | |

| China | 6mDMA1 | 46.2 | 51.7 | 59.9 | 64.4 | 70.2 | 78.5 | 84.0 |

| ADMA8 | 40.9 | 43.7 | 50.6 | 54.5 | 59.6 | 67.7 | 72.6 | |

| India | 6mDMA1 | 36.1 | 45.0 | 62.4 | 67.2 | 73.2 | 78.3 | 80.1 |

| ADMA8 | 30.7 | 36.5 | 50.8 | 57.9 | 64.7 | 70.7 | 72.6 | |

| Europe | 6mDMA1 | 36.9 | 38.7 | 40.2 | 42.6 | 48.9 | 57.8 | 66.0 |

| ADMA8 | 30.3 | 33.5 | 35.0 | 37.8 | 41.1 | 48.9 | 54.3 | |

| Africa | 6mDMA1 | 25.8 | 34.7 | 44.6 | 50.2 | 56.3 | 67.4 | 84.6 |

| ADMA8 | 20.2 | 29.3 | 37.5 | 43.2 | 47.8 | 53.4 | 59.6 | |

| Latin America and the Caribbean | 6mDMA1 | 15.8 | 22.3 | 29.9 | 38.7 | 49.5 | 59.0 | 78.5 |

| ADMA8 | 11.3 | 15.6 | 24.5 | 32.3 | 39.7 | 50.1 | 62.6 | |

| North America | 6mDMA1 | 39.3 | 39.8 | 41.4 | 43.8 | 51.7 | 64.8 | 77.3 |

| ADMA8 | 34.1 | 35.6 | 37.0 | 39.4 | 44.0 | 54.4 | 58.8 | |

| United States | 6mDMA1 | 39.6 | 40.3 | 43.3 | 51.8 | 60.1 | 68.8 | 77.3 |

| ADMA8 | 34.1 | 36.3 | 38.6 | 44.5 | 50.9 | 55.6 | 58.8 | |

| Oceania | 6mDMA1 | 13.6 | 18.5 | 25.8 | 33.0 | 35.9 | 38.0 | 40.3 |

| ADMA8 | 11.7 | 15.0 | 20.1 | 29.2 | 32.7 | 34.5 | 37.6 | |

| Global | 6mDMA1 | 13.6 | 26.8 | 39.8 | 44.8 | 54.8 | 68.9 | 84.6 |

| ADMA8 | 11.3 | 22.5 | 34.4 | 39.0 | 46.3 | 58.2 | 72.6 |

Note: The range of the maximum 6-mo daily maximum 1-h concentration (6mDMA1, relevant for J2009 relative risk estimates), and the annual average daily maximum 8-h concentrations (ADMA8, relevant for T2016 relative risk estimates) are shown. Ranges for China and India are shown because of the large health impacts estimated in these countries. Ranges from the United States are also shown because this is where the Jerrett et al. (2009) and Turner et al. (2016) studies were conducted.

Using the T2016 relative risk estimate () and ADM8h concentrations in each grid, we estimated that 1.23 million (95% CI: 0.85, 1.62 million) respiratory deaths among the global population of age were attributable to long-term exposure in 2010 using the minimum exposure in the T2016 cohort () as the low-concentration cutoff (LCC), and 1.04 million deaths (95% CI: 0.72, 1.37 million) using the fifth percentile LCC () (Table 2). Attributable deaths estimated using the T2016 relative risk estimate and the fifth percentile LCC represent 20.3% (95% CI: 14.5, 26.9%) of all respiratory deaths among those of age in 2010. In contrast, using the J2009 relative risk () and 6mDM1h concentrations, we estimated 0.55 million (95% CI: 0.20, 0.90) deaths attributable to long-term in 2010 using the minimum exposure in the J2009 cohort as the LCC () and 0.40 million (95% CI: 0.14, 0.65) million attributable respiratory deaths using the fifth percentile LCC ().

Table 2.

Global and regional estimates of respiratory deaths attributable to long-term exposure for adults of age.

| Region | Estimates based on J2009a | Estimates based on T2016b | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low-concentration cutoffc | Attributable respiratory deaths J2009 (thousands) | Low-concentration cutoffc | Attributable respiratory deaths T2016 (thousands) | Proportion of total respiratory deaths (T2016 estimates, %) | |

| Asia | 430 (161, 699) | 970 (686, 1,253) | 28.0 (19.2, 35.8) | ||

| 328 (120, 536) | 844 (593, 1,095) | 24.3 (17.1, 31.9) | |||

| China | 154 (59.9, 248) | 316 (230, 403) | 28.0 (20.5, 35.9) | ||

| 120 (45.6, 195) | 274 (198, 351) | 24.2 (17.2, 31.3) | |||

| India | 193 (74.8, 311) | 450 (329, 572) | 32.2 (23.5, 41.3) | ||

| 151 (57.2, 246) | 402 (291, 513) | 28.7 (20.0, 37.3) | |||

| Europe | 39.2 (13.9, 64.5) | 78.9 (54.2, 104) | 15.0 (10.4, 19.7) | ||

| 22.5 (7.7, 37.2) | 55.9 (38.1, 73.8) | 10.6 (6.9, 14.1) | |||

| Africa | 33.6 (6.6, 60.6) | 80.6 (37.1, 124) | 15.9 (7.5, 24.6) | ||

| 18.8 (3.6, 34.1) | 59.6 (27.5, 91.6) | 11.7 (5.8, 19.1) | |||

| Latin America and the Caribbean | 14.5 (5.1, 23.9) | 39.9 (27.4, 52.4) | 12.0 (8.2, 15.4) | ||

| 6.5 (2.3, 10.8) | 27.2 (18.6, 35.7) | 8.2 (5.4, 10.8) | |||

| North America | 30.1 (11.5, 48.7) | 63.8 (46.3, 81.3) | 23.9 (17.3, 30.6) | ||

| 22.0 (8.2, 35.8) | 53.5 (38.4, 68.5) | 20.0 (14.5, 25.8) | |||

| Oceania | 0.2 (0.06, 0.28) | 1.0 (0.7, 1.3) | 3.7 (2.4, 5.3) | ||

| 0d | 0.4 (0.3, 0.6) | 1.5 (1.0, 2.1) | |||

| Global | 547 (198, 897) | 1,234 (851, 1,616) | 24.0 (16.9, 31.7) | ||

| 398 (142, 654) | 1,040 (716, 1,365) | 20.3 (14.5, 26.9) | |||

Note: Estimates were calculated using relative risk estimates for long-term exposure and respiratory mortality derived in Jerrett et al. (2009) and Turner et al. (2016) and are also reported as a proportion of all respiratory deaths for the population aged in each region. Values in parentheses are 95% confidence intervals.

J2009 estimates use (95% CI: 1.013, 1.067) as the relative risk estimate and the maximum 6-mo daily 1-h maximum concentration as the exposure metric (Jerrett et al. 2009).

T2016 estimates use (95% CI: 1.08, 1.16) as the relative risk estimate and the annual daily 8-h maximum ozone concentration as the exposure metric (Turner et al. 2016).

Lower value is the minimum ozone concentration, and the upper value is the 5th percentile of the ozone concentration for the population and ozone metric used to derive the J2009 and T2016 relative risk estimates.

Estimated maximum 6-mo concentrations did not exceed the 5th percentile low-concentration cutoff in Oceania, and therefore no long-term respiratory deaths were estimated.

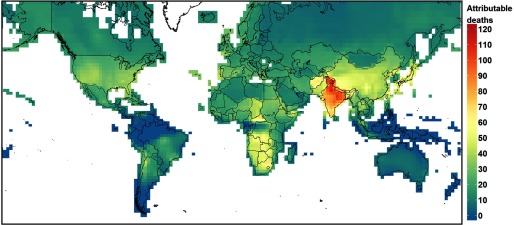

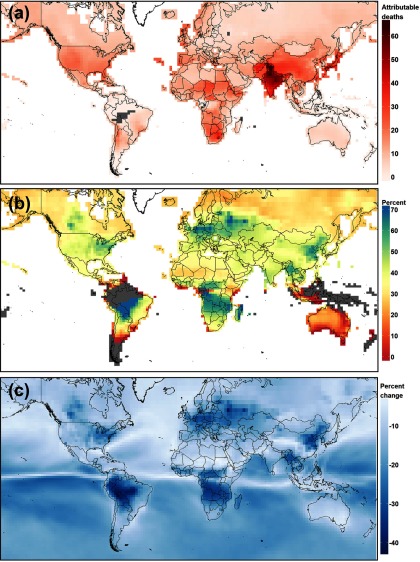

The majority (79–81%) of our estimated long-term respiratory deaths using the T2016 relative risk estimates were in Asia (Table 2, Figure 1), predominantly in India and China [37–39% of the global total for India depending on the LCC, and 26% for both LCCs for China (Table 2)]. Applying the T2016 relative risk estimates increased estimated long-term respiratory deaths everywhere in the world (Figure 2a), compared with the J2009 relative risk estimates (see Figure S2), reflecting the common increase in the HR. However, the increase in HR was offset to a different degree in different regions by the size of the decreases in the magnitude of the long-term exposure metric when quantified over the whole year (T2016) rather than 6 mo (J2009), and expressed as a daily 8-h maximum (T2016) rather than as a 1-h maximum (J2009). In those regions with relatively large reductions in the magnitude of the metric (Figure 2c), the increase in estimated attributable respiratory deaths was smaller than in those regions with a smaller reduction in the metric (Figure 2b). For example, there were larger reductions in the exposure metric, and smaller increases in estimated attributable respiratory deaths, at northern midlatitudes (eastern United States, northeast China, and central and northern Europe), compared with other regions (e.g., northern India). The spatial differences in the magnitude of the all-year compared with 6-mo metrics reflects different seasonal variability in concentrations at northern midlatitudes, compared with other regions (Monks et al. 2015).

Figure 1.

Estimated long-term -exposure attributable respiratory deaths in 2010 for adults of age. Units are attributable deaths per 100,000 people, and estimates were derived using the T2016 relative risk estimate [ (95% CI: 1.08, 1.16), adjusted for near-source and regional , and exposure] and annual average daily maximum 8-h concentration as the exposure metric, with a low-concentration cutoff set at the minimum exposure in the Turner et al. (2016) cohort () (Map Data: © EuroGeographics for the administrative boundaries).

Figure 2.

Spatial distribution of changes in estimated long-term respiratory deaths when using the J2009 relative risk estimates [ (95% CI: 1.013, 1.067), adjusted for total exposure] and 6-mo daily maximum 1-h concentration as the exposure metric ( low-concentration cutoff), and T2016 relative risk estimates [ (95% CI: 1.08, 1.16), adjusted for near-source and regional , and exposure] and annual average daily maximum 8-h concentration as the exposure metric ( low-concentration cutoff). (a) shows the absolute difference in attributable respiratory deaths per 100,000 people estimated using the J2009 and T2016 relative risk estimates. (b) shows the percent of T2016-based attributable respiratory death estimates accounted for by J2009-based attributable respiratory deaths estimates (colder colors indicate a smaller increase in estimated respiratory deaths when calculated using the T2016 relative risk estimate, warmer colors indicate a larger increase). (c) shows the percent decrease in the magnitude of the long-term exposure metric when using the annual average daily maximum 8-h metric (relevant for T2016 relative risk estimates), compared with the maximum 6-mo average daily maximum 1-h metric (relevant for J2009 relative risk estimates). Gray areas in each panel indicate those grids where the 6-mo or annual exposure metric was below the LCC, and therefore no respiratory deaths were estimated (Map Data: © EuroGeographics for the administrative boundaries).

In addition, the T2016 relative risk estimates were also applied with different LCCs compared with the J2009 relative risk estimates. The use of an annual metric to characterize population exposure compared with a 6-mo metric shifts the distribution of the exposure metric in different regions, including in relation to the relevant LCCs. For example, the median ADM8h concentration across all grids globally was 46% greater than the minimum exposure LCC (), compared with 35% greater for the median 6mDM1h concentration ( LCC), that is, a 33% larger exceedance of the minimum exposure LCC for the median ADM8h metric (Table 1). However, in Asia the exceedance of the LCC for the median ADM8h concentration was only 14% greater than for the median 6mDM1h concentrations, compared with 49% and 51% in Europe and North America, respectively (Table 1). Hence in different regions the change in the extent to which the exposure metrics exceed the LCC differs and contributes to regional differences in the increase in estimated respiratory mortality when applying the T2016 relative risk estimates.

We performed a sensitivity analysis of estimated respiratory deaths using a T2016 relative risk estimate derived from a single-pollutant model, instead of the multi-pollutant adjusted estimate used for the primary analyses. Estimated numbers of ozone-attributed respiratory deaths based on the single-pollutant model relative risk estimates were approximately 13% higher than the estimates derived using the multi-pollutant model relative risk estimates (see Table S2).

The respiratory mortality estimates using the J2009 relative risk estimate, as described above (; 95% CI: 1.013, 1.067; and LCCs), were comparable with previous estimates in Anenberg et al. (2010), Fang et al. (2013b), Silva et al. (2013), and Silva et al. (2016a) (see Table S4). In comparison with previous estimates of long-term attributable mortality by the Global Burden of Disease (GBD) project, our estimates using GBD-comparable inputs to Equation 1 (i.e., estimating COPD mortality using the J2009 single-pollutant relative risk estimate for respiratory mortality and maximum 3-mo daily maximum 1-h exposure metric) had overlapping confidence intervals with GBD 2010, GBD 2013, and GBD 2015 long-term deaths (GBD 2013 Risk Factors Collaborators 2015; GBD 2015 Risk Factors Collaborators 2016; Lim et al. 2012), but our central estimates were higher (see Table S3). Differences in the magnitude of exposure estimates, derived from the Tracer Model v5-FAst Scenario Screening Tool model in GBD (Brauer et al. 2016) and GEOS-Chem here, may contribute to this discrepancy. For example, in India and China, population-weighted 3-mo maximum daily 1-h concentrations were 5% (), and 22% () higher for GEOS-Chem, respectively. Further work is required to evaluate the performance of both models in these regions, which have the largest estimated health burden, although currently there is relatively low number and spatial density of monitoring sites in these regions to achieve this (Cooper et al. 2014).

Application of the T2016 relationships for COPD mortality specifically resulted in an estimated 0.86 million (95% CI: 0.53, 1.18 million) COPD deaths across the global population of age in 2010 using the minimum exposure in the T2016 cohort () as the LCC, and 0.74 million deaths (95% CI: 0.45, 1.02 million) using the fifth percentile LCC () (see Table S4, Figure S3). This indicates that estimated COPD deaths were approximately 70–71% of total estimated respiratory deaths. Hence, even when only focusing on COPD, long-term health impacts may be more significant than previously estimated [e.g., global long-term COPD deaths estimated by GBD 2015 were 6% of attributable deaths, whereas our estimates using T2016 relationships are 17–20% of this death estimate (GBD 2015 Risk Factors Collaborators 2016)].

Discussion

Results of this study estimating the global burden and spatial distribution of long-term exposure on mortality applying the revised T2016 relative risk estimates estimated 1.04–1.23 million respiratory deaths among the global population of age were attributable to exposure in 2010. The more than doubling of estimated long-term respiratory deaths obtained using the T2016 compared with J2009 relative risk estimates (0.40–0.55 million attributable respiratory deaths) increases the estimated contribution of to the global outdoor air pollution health burden. The respiratory mortality results for are 25–29% of the 4.2 million deaths estimated to be attributable to exposure by the Global Burden of Disease (GBD) (GBD 2015 Risk Factors Collaborators 2016).

Previous long-term attributable mortality estimates have used exposure over a 6-mo period for consistency with the exposure estimates in Jerrett et al. (2009) (Anenberg et al. 2010; Fang et al. 2013b; Silva et al. 2013, 2016a) (the GBD studies have applied the J2009 relative risk estimates using a 3-mo metric (Brauer et al. 2016; Cohen et al. 2017)). The 3- and 6-mo metrics previously applied to estimate long-term health burdens do not account for exposure that occurs during the rest of the year, which varies differently between regions. For example, at northern midlatitudes, including North America, Europe, and northeast China, there is substantial annual variation, with a peak during spring months. In contrast, closer to the equator, there is less annual variation in concentrations (Monks et al. 2015). Hence annual averaged concentrations are substantially lower than 3- or 6-mo concentrations at northern midlatitudes compared with closer to the equator (Figure 2, Table 1). This work shows that when exposure across the whole year is taken into account the spatial distribution of estimated respiratory mortality shifts in from the northern midlatitudes towards the equator, compared with previous analyses that quantified exposure only during part of the year. Consequently, the relative increase in estimated long-term attributable respiratory mortality using the T2016 compared with J2009 method was 134–165% for India, compared with 105–128% for China, 112–143% for North America and 101–148% for Europe.

The T2016 relative risk estimates used in the present analysis were derived using improved exposure estimates that combined monitored data with photochemical model output (Turner et al. 2016). In addition, we used T2016 relative risk estimates from multi-pollutant models adjusted for and for “near-source” and “regional” that have different correlation structures with . In contrast, previous global estimates of long-term deaths used J2009 relative risk estimates from a single-pollutant model [e.g., GBD 2015 Risk Factors Collaborators 2016), or a multi-pollutant model adjusted for total concentrations only (e.g., Anenberg et al. (2010)], but within which there was a moderate correlation between and exposure estimates. Hence the long-term death estimates presented in this work should be more independent of health burdens associated with exposure to and .

Additionally, the consistency of the association between exposure to fine particulate matter () and mortality in multiple ACS CPS-II cohort analyses to different estimates of exposure suggests that the stronger relationship between long-term exposure and attributable mortality in Turner et al. (2016) may represent an additional contribution to the outdoor air pollution health burden, as opposed to a reattribution of premature deaths to long-term exposure. For example, the relative risk estimates derived in Turner et al. (2016) between long-term exposure and all-cause mortality [HR for a increase in concentration, single-pollutant model: 1.07 (95% CI: 1.06, 1.09) multipollutant model using alternative estimate of exposure: 1.06 (95% CI: 1.04, 1.08)] was similar to that derived in the Krewski et al. (2009) [HR: 1.06 (95% CI: 1.04, 1.08)], and Pope et al. (2002) [HR: 1.06 (95% CI: 1.02, 1.11)] analyses of the ACS CPS-II cohort.

Turner et al. (2016) also calculated a significant association with cardiovascular mortality in addition to the significant association calculated between long-term exposure and respiratory mortality. This is in contrast to Jerrett et al. (2009) where a significant inverse relationship between long-term exposure and cardiovascular mortality was calculated. The evidence for associations, and causal linkages, between long-term exposure and cardiovascular mortality has been reviewed by the WHO and the U.S. EPA (REVIHAAP 2013; U.S. EPA 2013). REVIHAAP (2013) identified three cohort studies that estimated a significant relationship between long-term exposure and mortality, which includes, or is a subset of, cardiovascular mortality. One study calculated an association with ischemic heart disease (IHD) (Lipsett et al. 2011), one study with cardiopulmonary disease (Smith et al. 2009a), and one with congestive heart failure (Zanobetti and Schwartz 2011). Based on the evidence from a limited number of epidemiological and toxicological studies, the U.S. EPA concluded that the available evidence is only “suggestive of a causal relationship between long-term exposure to and cardiovascular effects” (U.S. EPA 2013), whereas Prueitt et al. (2014) concluded that the evidence from epidemiological, and human and animal toxicological studies is “below equipoise,” that is, not sufficient to conclude that a causal relationship is as least as likely as not. Hence because the evidence for a causal association between long-term exposure and cardiovascular mortality is limited compared with respiratory mortality, we did not estimate the global impact of long-term exposure on cardiovascular mortality. However, if additional evidence shows that the T2016 relative risk estimate between long-term exposure and cardiovascular mortality is valid (Schwartz 2016), then the inclusion of cardiovascular mortality would increase the estimated health burden further.

Uncertainties

Limitations of this study include estimation of long-term exposure using a single global chemistry transport model at global grid resolution (, at the equator), that does not account for local-scale variability in concentrations (Monks et al. 2015). However, previous studies indicate only a modest effect of grid spatial resolution on attributable mortality estimates because the spatial gradients in concentrations are typically smoother than those of population distribution. Punger and West (2013) calculated a less than 6% increase in attributable mortality estimates in the United States, when derived using modeled concentrations at a grid scale compared with the finest () resolution. Furthermore, using GEOS-Chem, we obtained similar long-term death estimates to previous studies using consistent methods (including the GBD, see Table S3), based on J2009 relationships, including those using chemical transport models with finer grid resolution (see Table S3).

Compared with 1,420 monitoring sites globally (85% of which were in the United States), a mean bias of was calculated for GEOS-Chem, which was consistent with biases estimated in other global models as part of multi-model comparison projects (Yan et al. 2016). This bias was identified by Yan et al. (2016) to be partly due to small scale nonlinear chemical processes that are not captured at the grid resolution of the GEOS-Chem model used here. Similarly, in China, where some of the highest health burdens were estimated, a positive bias was calculated in comparison with available measurements, for example, Zhu and Liao (2016): mean bias of based on monitoring data from 10 Chinese sites (i.e., GEOS-Chem modeled concentrations were on average 11.6% higher than the measured concentration), and Lou et al. (2014): mean bias of compared with data from 12 Chinese sites. Hence, accounting for these smaller-scale nonlinear processes in the GEOS-Chem global model, and in global models in general, may therefore yield somewhat lower estimates of exposure than estimated in this study. Ongoing efforts to harmonize and synthesize available measurement data worldwide will be particularly useful to extend model-measurement comparison with other regions (including those with the highest estimated health burdens) (Cooper et al. 2014; http://www.igacproject.org/TOAR), as is further work to increase global monitoring data coverage. Further evaluation of modeled exposure estimates through inter-model and measurement comparisons is also warranted.

Consistent with previous analyses of the GBD, we used relative risk estimates derived from a U.S. cohort to estimate mortality attributable to long-term exposure throughout the world. This assumes that the relative risk estimates for the ACS CPS-II population are transferable to all populations globally, for which the prevalence of other risk factors for respiratory mortality, such as socioeconomic status, access to health care, nutrition, race/ethnicity, education, and other competing risks may be different from the predominantly white, high-school educated CPS-II cohort population. Although Turner et al. (2016) adjusted for many of these confounders in analyzing the ACS CPS-II cohort, a limitation of this study is the application of the T2016 relative risk estimates to populations where the distribution of these risk factors is likely to be substantially different from the distribution across the ACS CPS-II population. The two European cohort studies that have assessed long-term exposure and mortality estimated null or negative associations between exposure and respiratory mortality (Bentayeb et al. 2015; Carey et al. 2013), and no such cohort studies have been conducted outside North America and Europe (Atkinson et al. 2016). In some regions, our modeled annual daily maximum 8-h concentrations (Table 1; see also Figure S1) were higher than for the Turner et al. (2016) cohort (maximum estimated exposure of Turner et al. (2016) cohort: ). The T2016 HRs for ozone and mortality reported by Turner et al. (2016) were based on estimated exposures in the United States during 2002–2004, at the end of a 24-y period during which precursor emissions decreased substantially in the United States (Simon et al. 2015). Their application to regions with increasing precursor emissions since the 1980s is therefore uncertain (Monks et al. 2015). Further investigation is required to determine the relationship between changing long-term exposure and mortality in regions with increasing emissions.

Finally, potential interactions between exposure to and other pollutants (e.g., ) and impacts on mortality were not considered by Turner et al. (2016). Hence long-term mortality estimates reported here assume independence of effects of each pollutant. As additional epidemiological data becomes available on potential interactions between exposure to and (and other pollutants), or on the transferability of effect estimates between regions, long-term mortality estimates should be updated to account for the improved understanding of these aspects of impacts on mortality.

Conclusions

To evaluate the overall outdoor air pollution health burden, mortality attributable to and exposure has been estimated at global (Anenberg et al. 2010; Fang et al. 2013b; GBD 2013 Risk Factors Collaborators 2015; Lelieveld et al. 2015; Likhvar et al. 2015; Silva et al. 2013), regional (Crippa et al. 2016), and national scales (Caiazzo et al. 2013; Fann et al. 2012; Kim et al. 2015), and many studies have used relative risk estimates derived from the ACS CPS-II cohort (Jerrett et al. 2009) to estimate mortality attributable to ozone air pollution in adults of age. Our findings suggest that the potential impact of long-term exposure on respiratory mortality is substantially higher when respiratory deaths attributable to long-term exposure are estimated using updated relative risks, exposure metrics, and low-concentration thresholds from the ACS CPS-II cohort (Turner et al. 2016). We estimated 1.04–1.23 million long-term attributable respiratory deaths using the updated assumptions, a 126–161% increase from estimates derived using assumptions based on an earlier analysis of the ACS CPS-II cohort (Jerrett et al. 2009). This study indicates that reducing exposure, for example, through reduction of precursor emissions (i.e., methane, , VOCs, and CO), could have substantially greater benefits than previously quantified in reducing the overall global burden of disease attributable to outdoor air pollution. Furthermore, human health co-benefits from climate mitigation policies (Anenberg et al. 2012; Shindell et al. 2012, 2016; West et al. 2013), and health burdens from climate-driven changes in concentrations (Fang et al. 2013a; Silva et al. 2016b; Zhu and Liao 2016) may also be greater than previously estimated.

Supplemental Material

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to N. Fann for helpful discussions regarding this work.

This work was supported by the Stockholm Environment Institute (SEI) Low Emissions Development Pathways (LED-P) Initiative and NASA Health and Air Quality Applied Sciences Team grant NNX16AQ26G. M.C.T. was funded by a Canadian Institutes of Health Research Fellowship.

References

- Anenberg SC, Horowitz LW, Tong DQ, West JJ. 2010. An estimate of the global burden of anthropogenic ozone and fine particulate matter on premature human mortality using atmospheric modeling. Environ Health Perspect 118(9):1189–1195, PMID: 20382579, 10.1289/ehp.0901220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anenberg SC, Schwartz J, Shindell D, Amann M, Faluvegi G, Klimont Z, et al. 2012. Global air quality and health co-benefits of mitigating near-term climate change through methane and black carbon emission controls. Environ Health Perspect 120(6):831–839, PMID: 22418651, 10.1289/ehp.1104301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atkinson RW, Butland BK, Dimitroulopoulou C, Heal MR, Stedman JR, Carslaw N, et al. 2016. Long-term exposure to ambient ozone and mortality: a quantitative systematic review and meta-analysis of evidence from cohort studies. BMJ Open 6(2):e009493, PMID: 26908518, 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-009493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentayeb M, Wagner V, Stempfelet M, Zins M, Goldberg M, Pascal M, et al. 2015. Association between long-term exposure to air pollution and mortality in France: a 25-year follow-up study. Environ Int 85:5–14, PMID: 26298834, 10.1016/j.envint.2015.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bey I, Jacob DJ, Yantosca RM, Logan JA, Field BD, Fiore AM, et al. 2001. Global modeling of tropospheric chemistry with assimilated meteorology: model description and evaluation. J Geophys Res 106(D19):23073–23095, 10.1029/2001JD000807. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brauer M, Freedman G, Frostad J, van Donkelaar A, Martin RV, Dentener F, et al. 2016. Ambient air pollution exposure estimation for the Global Burden of Disease 2013. Environ Sci Technol 50(1):79–88, PMID: 26595236, 10.1021/acs.est.5b03709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caiazzo F, Ashok A, Waitz IA, Yim SHL, Barrett SRH. 2013. Air pollution and early deaths in the United States. Part I: quantifying the impact of major sectors in 2005. Atmos. Environ 79:198–208, 10.1016/j.atmosenv.2013.05.081. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carey IM, Atkinson RW, Kent AJ, van Staa T, Cook DG, Anderson HR. 2013. Mortality associations with long-term exposure to outdoor air pollution in a national English cohort. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 187(11):1226–1233, PMID: 23590261, 10.1164/rccm.201210-1758OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CIESIN-FAO-CIAT [(Center for International Earth Science Information Network (CIAT); Columbia University, United Nations Food and Agriculture Programme (FAO); Centro Internacional de Agricultura Tropical (CIAT)]. 2005. Gridded Population of the World, Version 3 (GPWv3): Population Count Grid. Palisades, NY:NASA Socioeconomic Data and Applications Center; http://dx.doi.org/10.7927/H4639MPP [accessed 7 July 2017]. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen AJ, Brauer M, Burnett RT, Anderson HR, Frostad J, Estep K, et al. 2017. Estimates and 25-year trends of the global burden of disease attributable to ambient air pollution: an analysis of data from the Global Burden of Diseases Study 2015. Lancet 389(10082):1907–1918, PMID: 28408086, 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30505-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper OR, Parrish DD, Ziemke J, Balashov NV, Cupeiro M, Galbally IE, et al. 2014. Global distribution and trends of tropospheric ozone: an observation-based review. Elem Sci Anth 2:29, 10.12952/journal.elementa.000029. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Crippa M, Janssens-Maenhout G, Dentener F, Guizzardi D, Sindelarova K, Muntean M, et al. 2016. Forty years of improvements in European air quality: regional policy-industry interactions with global impacts. Atmos Chem Phys 16:3825–3841, 10.5194/acp-16-3825-2016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fang Y, Mauzerall DL, Liu JF, Fiore AM, Horowitz LW. 2013a. Impacts of 21st century climate change on global air pollution-related premature mortality. Clim Change 121(2):239–253, 10.1007/s10584-013-0847-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fang Y, Naik V, Horowitz LW, Mauzerall DL. 2013b. Air pollution and associated human mortality: the role of air pollutant emissions, climate change and methane concentration increases from the preindustrial period to present. Atmos Chem Phys 13:1377–1394, 10.5194/acp-13-1377-2013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fann N, Lamson AD, Anenberg SC, Wesson K, Risley D, Hubbell BJ. 2012. Estimating the national public health burden associated with exposure to ambient PM2.5 and ozone. Risk Anal 32(1):81–95, PMID: 21627672, 10.1111/j.1539-6924.2011.01630.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GBD 2013 Risk Factors Collaborators. 2015. Global, regional, and national comparative risk assessment of 79 behavioural, environmental and occupational, and metabolic risks or clusters of risks in 188 countries, 1990–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet 386(10010):2287–2323, PMID: 26364544, 10.1016/s0140-6736(15)00128-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GBD 2015 Mortality and Causes of Death Collaborators. 2016. Global, regional, and national life expectancy, all-cause mortality, and cause-specific mortality for 249 causes of death, 1980–2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet 388(10053):1459–1544, PMID: 27733281, 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31012-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GBD 2015 Risk Factors Collaborators. 2016. Global, regional, and national comparative risk assessment of 79 behavioural, environmental and occupational, and metabolic risks or clusters of risks, 1990–2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet 388(10053):1659–1724, PMID: 27733284, 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31679-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacquemin B, Kauffmann F, Pin I, Le Moual N, Bousquet J, Gormand F, et al. 2012. Air pollution and asthma control in the Epidemiological study on the Genetics and Environment of Asthma. J Epidemiol Community Health 66(9):796–802, PMID: 21690606, 10.1136/jech.2010.130229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janssens-Maenhout G, Crippa M, Guizzardi D, Dentener F, Muntean M, Pouliot G, et al. 2015. HTAP_v2.2: a mosaic of regional and global emission grid maps for 2008 and 2010 to study hemispheric transport of air pollution. Atmos Chem Phys 15:11411–11432, 10.5194/acp-15-11411-2015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jerrett M, Burnett RT, Pope CA III, Ito K, Thurston G, Krewski D, et al. 2009. Long-term ozone exposure and mortality. N Engl J Med 360(11):1085–1095, PMID: 19279340, 10.1056/NEJMoa0803894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim YM, Zhou Y, Gao Y, Fu JS, Johnson BA, Huang C, et al. 2015. Spatially resolved estimation of ozone-related mortality in the United States under two Representative Concentration Pathways (RCPs) and their uncertainty. Clim Change 128(1–2):71–84, PMID: 25530644, 10.1007/s10584-014-1290-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krewski D, Jerrett M, Burnett RT, Ma R, Hughes E, Shi Y, et al. 2009. Extended Follow-up and Spatial Analysis of the American Cancer Society Study Linking Particulate Air Pollution and Mortality. Boston, MA:Health Effects Institute. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lapina K, Henze DK, Milford JB, Huang M, Lin M, Fiore AM, et al. 2014. Assessment of source contributions to seasonal vegetative exposure to ozone in the U.S. J Geophys Res Atmos 119:324–340, 10.1002/2013JD020905. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lelieveld J, Evans JS, Fnais M, Giannadaki D, Pozzer A. 2015. The contribution of outdoor air pollution sources to premature mortality on a global scale. Nature 525(7569):367–371, PMID: 26381985, 10.1038/nature15371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Likhvar VN, Pascal M, Markakis K, Colette A, Hauglustaine D, Valari M, et al. 2015. A multi-scale health impact assessment of air pollution over the 21st century. Sci Total Environ 514:439–449, PMID: 25687670, 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2015.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim SS, Vos T, Flaxman AD, Danaei G, Shibuya K, Adair-Rohani H, et al. 2012. A comparative risk assessment of burden of disease and injury attributable to 67 risk factors and risk factor clusters in 21 regions, 1990–2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet 380(9859):2224–2260, PMID: 23245609, 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61766-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin S, Liu X, Le LH, Hwang SA. 2008. Chronic exposure to ambient ozone and asthma hospital admissions among children. Environ Health Perspect 116(12):1725–1730, PMID: 19079727, 10.1289/ehp.11184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipsett MJ, Ostro BD, Reynolds P, Goldberg D, Hertz A, Jerrett M, et al. 2011. Long-term exposure to air pollution and cardiorespiratory disease in the California Teachers Study cohort. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 184(7):828–835, PMID: 21700913, 10.1164/rccm.201012-2082OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lou S, Liao H, Zhu B. 2014. Impacts of aerosols on surface-layer ozone concentrations in China through heterogeneous reactions and changes in photolysis rates. Atmos Environ 85:123–138, 10.1016/j.atmosenv.2013.12.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Malig BJ, Pearson DL, Chang YB, Broadwin R, Basu R, Green RS, et al. 2016. A time-stratified case-crossover study of ambient ozone exposure and emergency department visits for specific respiratory diagnoses in California (2005–2008). Environ Health Perspect 124(6):745–753, PMID: 26647366, 10.1289/ehp.1409495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medina-Ramón M, Zanobetti A, Cavanagh DP, Schwartz J. 2006. Extreme temperatures and mortality: assessing effect modification by personal characteristics and specific cause of death in a multi-city case-only analysis. Environ Health Perspect 114(9):1331–1336, PMID: 16966084, 10.1289/ehp.9074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng YY, Rull RP, Wilhelm M, Lombardi C, Balmes J, Ritz B. 2010. Outdoor air pollution and uncontrolled asthma in the San Joaquin Valley, California. J Epidemiol Community Health 64(2):142–147, PMID: 20056967, 10.1136/jech.2009.083576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monks PS, Archibald AT, Colette A, Cooper O, Coyle M, Derwent R, et al. 2015. Tropospheric ozone and its precursors from the urban to the global scale from air quality to short-lived climate forcer. Atmos Chem Phys 15:8889–8973, 10.5194/acp-15-8889-2015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Parker JD, Akinbami LJ, Woodruff TJ. 2009. Air pollution and childhood respiratory allergies in the United States. Environ Health Perspect 117(1):140–147, PMID: 19165401, 10.1289/ehp.11497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pope CA III, Burnett RT, Thun MJ, Calle EE, Krewski D, Ito K, et al. 2002. Lung cancer, cardiopulmonary mortality, and long-term exposure to fine particulate air pollution. JAMA 287:1132–1141, PMID: 11879110, 10.1001/jama.287.9.1132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prueitt RL, Lynch HN, Zu K, Sax SN, Venditti FJ, Goodman JE. 2014. Weight-of-evidence evaluation of long-term ozone exposure and cardiovascular effects. Crit Rev Toxicol 44(9):791–822, PMID: 25257962, 10.3109/10408444.2014.937855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Punger EM, West JJ. 2013. The effect of grid resolution on estimates of the burden of ozone and fine particulate matter on premature mortality in the USA. Air Qual Atmos Health 6(3):563–573, PMID: 24348882, 10.1007/s11869-013-0197-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- REVIHAAP (Review of Evidence on Health Aspects of Air Pollution). 2013. Review of Evidence on Health Aspects of Air Pollution – REVIHAAP Project Technical Report. Bonn, Germany:World Health Organization (WHO) Regional Office for Europe; http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0004/193108/REVIHAAP-Final-technical-report-final-version.pdf?ua=1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz J. 2016. The year of ozone. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 193(10):1077–1079, PMID: 27174475, 10.1164/rccm.201512-2533ED. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shindell D, Kuylenstierna JC, Vignati E, van Dingenen R, Amann M, Klimont Z, et al. 2012. Simultaneously mitigating near-term climate change and improving human health and food security. Science 335(6065):183–189, PMID: 22246768, 10.1126/science.1210026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shindell DT, Lee Y, Faluvegi G. 2016. Climate and health impacts of US emissions reductions consistent with 2°C. Nature Clim Change 6:503–507, 10.1038/nclimate2935. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Silva RA, Adelman Z, Fry MM, West JJ. 2016a. The impact of individual anthropogenic emissions sectors on the global burden of human mortality due to ambient air pollution. Environ Health Perspect 124(11):1776–1784, PMID: 27177206, 10.1289/EHP177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva RA, West JJ, Lamarque JF, Shindell DT, Collins WJ, Dalsoren S, et al. 2016b. The effect of future ambient air pollution on human premature mortality to 2100 using output from the ACCMIP model ensemble. Atmos Chem Phys 16:9847–9862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva RA, West JJ, Zhang Y, Anenberg SC, Lamarque JF, Shindell DT, et al. 2013. Global premature mortality due to anthropogenic outdoor air pollution and the contribution of past climate change. Environ Res Lett 8(3):034005, 10.1088/1748-9326/8/3/034005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Simon H, Reff A, Wells B, Xing J, Frank N. 2015. Ozone trends across the United States over a period of decreasing NOx and VOC emissions. Environ Sci Technol 49(1):186–195, PMID: 25517137, 10.1021/es504514z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith KR, Jerrett M, Anderson HR, Burnett RT, Stone V, Derwent R, et al. 2009a. Public health benefits of strategies to reduce greenhouse-gas emissions: health implications of short-lived greenhouse pollutants. Lancet 374(9707):2091–2103, 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61716-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith RL, Xu B, Switzer P. 2009b. Reassessing the relationship between ozone and short-term mortality in U.S. urban communities. Inhal Toxicol 21(suppl 2):37–61, PMID: 19731973, 10.1080/08958370903161612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner MC, Jerrett M, Pope CA III, Krewski D, Gapstur SM, Diver WR, et al. 2016. Long-term ozone exposure and mortality in a large prospective study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 193(10):1134–1142, PMID: 26680605, 10.1164/rccm.201508-1633OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. EPA (U.S. Environmental Protection Agency). 2013. 2013 Final Report: Integrated Science Assessment of Ozone and Related Photochemical Oxidants. Washington, DC:U.S. EPA; EPA/600/R-10/076F. [Google Scholar]

- West JJ, Smith SJ, Silva RA, Naik V, Zhang Y, Adelman Z, et al. 2013. Co-benefits of mitigating global greenhouse gas emissions for future air quality and human health. Nat Clim Chang 3(10):885–889, PMID: 24926321, 10.1038/NCLIMATE2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan Y, Lin J, Chen J, Hu L. 2016. Improved simulation of tropospheric ozone by a global-multi-regional two-way coupling model system. Atmos Chem Phys 16:2381–2400, 10.5194/acp-16-2381-2016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zanobetti A, Schwartz J. 2006. Air pollution and emergency admissions in Boston, MA. J Epidemiol Community Health 60(10):890–895, PMID: 16973538, 10.1136/jech.2005.039834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zanobetti A, Schwartz J. 2011. Ozone and survival in four cohorts with potentially predisposing diseases. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 184(7):836–841, PMID: 21700916, 10.1164/rccm.201102-0227OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu J, Liao H. 2016. Future ozone air quality and radiative forcing over China owing to future changes in emissions under the Representative Concentration Pathways (RCPs). J Geophys Res Atmos 121(4):1978–2001, 10.1002/2015JD023926. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.