Abstract

Background

Biologic therapy is effective for treatment of moderate-to-severe psoriasis but may be associated with an increased risk for serious infection.

Objective

To estimate the serious infection rate among patients with psoriasis treated with biologic as compared with nonbiologic systemic agents within a community-based health care delivery setting.

Methods

We identified 5889 adult Kaiser Permanente Northern California health plan members with psoriasis who had ever been treated with systemic therapies and calculated the incidence rates and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for serious infections over 29,717 person-years of follow-up. Adjusted hazard ratios (aHRs) were calculated using Cox regression.

Results

Adjusting for age, sex, race or ethnicity, and comorbidities revealed a significantly increased risk for overall serious infection among patients treated with biologics as compared with those treated with nonbiologics (aHR, 1.31; 95% CI, 1.02–1.68). More specifically, there was a significantly elevated risk for skin and soft tissue infection (aHR, 1.75; 95% CI, 1.19–2.56) and meningitis (aHR, 9.22; 95% CI, 1.77–48.10) during periods of active biologic use.

Limitations

Risk associated with individual drugs was not examined.

Conclusion

We found an increased rate of skin and soft tissue infections among patients with psoriasis treated with biologic agents. There also was a signal suggesting increased risk for meningitis. Clinicians should be aware of these potential adverse events when prescribing biologic agents.

Keywords: biologics, epidemiology, psoriasis, serious adverse infections, soft tissue infections, TNF-α

Psoriasis is a chronic, immune-mediated skin disease associated with considerable morbidity that afflicts 2% to 3% of the general population.1–3 Patients with moderate-to-severe psoriasis have traditionally been treated with systemic antiproliferative or immunosuppressive agents. More recently, biologic agents, including tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) inhibitors, interleukin (IL) 12/IL-23 inhibitors, and IL-17 inhibitors4–6 targeting key components of the dysregulated inflammatory response, have increased therapeutic options for psoriasis. Despite the efficacy of biologic agents, their effects on immune function may increase risk for adverse events, including infections.

Serious infection, defined as an infection that that requires hospitalization and treatment with systemic antibiotics, can cause substantial morbidity and mortality. Although there is an established association between serious infections and use of biologics in patients with other autoimmune conditions, evidence of this relationship in patients with psoriasis who are using biologics has been disputed.7–10

A recent meta-analysis revealed no increased risk for serious infection, whereas a prospective cohort study observed a significantly increased risk for serious infection with specific biologic agents.11,12 The contradictory results may be a result of data aggregation from multiple locations, inadequate follow-up time and sample size, variable exclusion criteria, and inconsistent definitions of serious infection. To address these concerns, we analyzed these events in patients with newly diagnosed psoriasis in a real-world, integrated practice setting with the longest follow-up time to date of any study, together allowing for greater accuracy in data capture and increased likelihood of recording these rare, but serious events. Using data from a large cohort of patients with moderate-to-severe psoriasis treated systemically within an integrated community-based health care system, we have estimated the serious adverse infectious event incidence rate (IR) and adjusted hazard ratio (aHR) among subjects during periods of treatment with a biologic agent, treatment with a nonbiologic agent, and no active systemic treatment.

METHODS

Study setting and population

Kaiser Permanente Northern California (KPNC) is a prepaid, comprehensive, integrated care delivery system that maintains computerized data of all visits, procedures, pharmacy-dispensed medications, and other medical goods and services to its 3.9 million members, representing 35% of the insured population in Northern California.13 The study population included all KPNC health plan members 18 years or older with a diagnosis of psoriasis (defined as having an outpatient dermatologist-rendered visit coded with the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, diagnosis code 696.1) between January 1, 1998, and December 31, 2011, and treated with a systemic agent for psoriasis after diagnosis during the study period. For each subject, the index date was defined as the date on which the member filled a prescription for a systemic agent used to treat psoriasis. At least 12 months of health plan enrollment before the index date was required for study inclusion. Members with the following disease codes in the 365 days before their index dates were excluded: solid organ or autologous bone marrow transplantation, HIV infection, advanced kidney or liver disease, or prior cancer diagnoses (excluding nonmelanoma skin cancer). Patients were followed from their index date until the first occurrence of (1) serious infection; (2) loss of health plan membership; (3) newly diagnosed advanced kidney or liver disease, cancer (excluding nonmelanoma skin cancer), or HIV; (4) solid organ or autologous bone marrow transplant; (5) death; or (6) end of the study period (December 31, 2012). The study was approved by the Kaiser Foundation Research Institute institutional review board.

Data sources

Medication data included the date of the dispensed medication or infusion, route, dose, quantity dispensed, and number of days supplied. Infusions of infliximab were considered equivalent to a 56-day supply, rituximab to a 180-day supply, and other injected or infused drugs to a 30-day supply.

Definition of psoriasis treatment episode

For each individual, we extracted data on all dispensed medications and infusions for oral, intravenous, and intramuscular biologic and nonbiologic agents during the study period. The following agents were classified as biologic treatments: adalimumab, etanercept, infliximab, ustekinumab, golimumab, certolizumab, tocilizumab, abatacept, anakinra, and rituximab. The following agents were classified as nonbiologic treatments: methotrexate, retinoids, cyclosporine, hydroxyurea, mycophenolate mofetil, sulfasalazine, and thioguanine. Per study protocol, we were unable to examine individual drugs, only drug categories. Drug exposure was calculated under an assumption of prescription adherence, so that drug use equaled the day supply variable of the dispensed medication; refilled medication was equated to drug use after completion of the prior course. To allow for possible noncompliance and varied half-lives of the drugs of interest, treatment gaps of up to 90 days were overlooked and 90 days was added to the end of each drug exposure episode.

Baseline risk factors

Baseline risk factors were assessed in the year before index and were derived from vital signs, medication use, procedures, diagnoses (International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, and Current Procedural Terminology codes), and results of laboratory tests. Baseline measures were body mass index, dyslipidemia, hypertension, tobacco use, coronary artery disease, and diabetes.

Outcomes

The following serious infection outcomes were assessed: sepsis, pneumonia, skin and soft tissue infections (SSTIs), meningitis, and renal/urinary tract infections. Serious infections were defined as inpatient hospitalizations accompanied by a diagnosis of 1 of the aforementioned infections with use of parenteral antibiotics.

Statistical analysis

IRs for the first occurrence of a serious infection were calculated for current use of biologic agents, current use of nonbiologics, and current nonuse of systemic treatment. Hazard ratios were calculated using Cox proportional hazards regression models, accommodating right-censoring. aHRs were calculated by including the following covariates: age, sex, race, and baseline risk factors. Systemic treatment was handled as a time-dependent covariate in regression models, capturing whether the patient was exposed to biologics (with or without concurrent use of nonbiologics), nonbiologics only, or nonsystemic medication on each day of follow-up.

RESULTS

Table I shows the baseline demographic characteristics of cohort members who were exposed to any biologic as compared with those that were treated with only nonbiologics. Persons ever exposed to a biologic were more likely to be younger, male, and Hispanic and less likely to be black than were persons never exposed to biologics (P < .01). Users of biologics had a statistically significantly longer duration of disease (2.96 years) before the start of systemic therapy as compared with users of nonbiologics (2.45 years). Users of biologics were less likely to have coronary artery disease.

Table I.

Characteristics of KPNC Cohort with systemically treated psoriasis

| Characteristics | All n = 5889 | Ever biologic use n = 2258 | Never biologic use n = 3631 | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||||

| Mean age at index (±SD) | 51.00 (15) | 47.50 (13) | 53.17 (16) | <.01 |

| Categorical age, y, n (%) | <.01 | |||

| 18 to <50 | 2791 (47) | 1310 (58) | 1481 (41) | |

| 50 to <65 | 2059 (35) | 742 (33) | 1317 (36) | |

| ≥65 | 1039 (18) | 206 (9) | 833 (23) | |

| Sex, n (%) | .01 | |||

| Female | 2914 (49) | 1071 (47) | 1843 (51) | |

| Male | 2975 (51) | 1187 (53) | 1788 (49) | |

| Race/ethnicity, n (%) | <.01 | |||

| White, non-Hispanic | 3377 (57) | 1299 (58) | 2078 (57) | |

| White, Hispanic | 824 (14) | 349 (15) | 475 (13) | |

| Black | 237 (4) | 68 (3) | 169 (5) | |

| Asian/Native American | 940 (16) | 371 (16) | 569 (16) | |

| Multiracial | 290 (5) | 110 (5) | 180 (5) | |

| Unknown | 221 (4) | 61 (3) | 160 (4) | |

| Baseline risk factors* | ||||

| CAD, n (% yes) | 223 (4) | 56 (2) | 167 (5) | <.01 |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (% yes) | 798 (14) | 290 (13) | 508 (14) | .21 |

| BMI (closest to index), kg/m2, n (%) | <.01 | |||

| <25 (normal) | 714 (12) | 280 (12) | 434 (12) | |

| 25–30 (overweight) | 1034 (18) | 431 (19) | 603 (17) | |

| >30 (obese) | 1412 (24) | 653 (29) | 759 (21) | |

| Missing | 2729 (46) | 894 (40) | 1835 (51) | |

| Cigarette use, n (% yes) | <.01 | |||

| Current | 652 (11) | 284 (13) | 368 (10) | |

| Former | 583 (10) | 249 (11) | 334 (9) | |

| Never | 1020 (17) | 443 (20) | 577 (16) | |

| Unknown | 3,634 (62) | 1282 (57) | 2352 (65) | |

| Duration of psoriasis, y | 2.65 (3) | 2.96 (3) | 2.45 (3) | <.01 |

BMI, Body mass index; CAD, coronary artery disease; KPNC, Kaiser Permanente Northern California; SD, standard deviation.

Baseline risk factors measured within 12 months before index date.

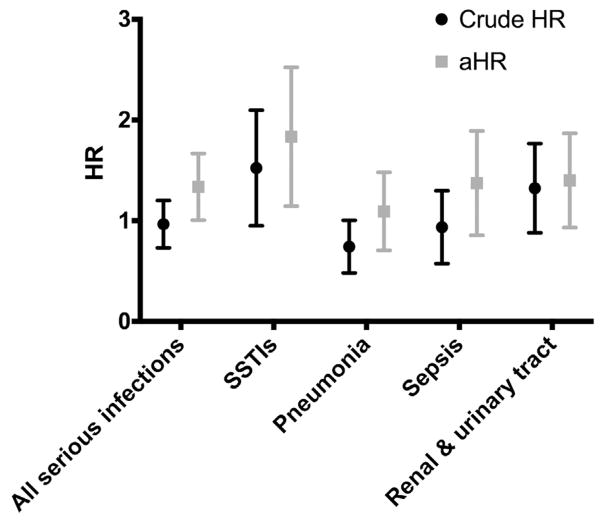

Table II summarizes the serious infection IRs during the time when persons were (1) exposed to biologics, (2) exposed only to nonbiologic systemic therapies, and (3) not being actively treated with systemic therapy. The point estimate for the overall IR per 1000 person-years for serious infections was lower among patients with psoriasis who were being actively treated with a biologic agent (IR, 16.3; 95% confidence interval [CI], 13.2–19.3) than among those undergoing nonbiologic therapy (IR, 17.9; 95% CI, 15.3–20.4). However, aHRs (Fig 1) revealed a statistically significant difference in overall serious infection rates between persons receiving biologics and persons receiving nonbiologics (aHR, 1.31; 95% CI, 1.02–1.68). Examining subclasses of serious infections demonstrated a statistically significant difference between persons using biologics and persons receiving nonbiologics for SSTIs (aHR, 1.75; 95% CI, 1.19–2.56) and meningitis (aHR, 9.22; 95% CI, 1.77–48.10). There was no significant difference in pneumonia, sepsis, or renal/urinary tract infection when time using a biologic and time not using a biologic were compared.

Table II.

Incidence rates for serious infections in KPNC treatment cohorts of persons with psoriasis (N = 5889)

| During biologic use | During nonbiologic use | During no systemic treatment | Biologic vs nonbiologic vs no treatment |

Crude HR | aHR* | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||

| Outcome | N (%) | Years† | IR (95% CI)‡ | N (%) | Years† | IR (95% CI)‡ | N (%) | Years† | IR (95% CI)‡ | (95% CI) | (95% CI) | |

| Skin and soft tissue | 50 (26) | 6791 | 7.4 (5.3–9.4) | 63 (33) | 10,836 | 5.8 (4.4–7.2) | 76 (40) | 13,014 | 5.8 (4.5–7.2) | Biologic vs nonbiologic | 1.45 (0.99–2.13) | 1.75 (1.19–2.56) |

| Nonbiologic vs no treatment§ | 1.26 (0.87–1.81) | 1.32 (0.92–1.90) | ||||||||||

| Meningitis | 4 (57) | 6924 | 0.6 (0.0–1.1) | 1 (14) | 10,979 | 0.1 (0.0–0.3) | 2 (29) | 13,352 | 0.1 (0.0–0.4) | Biologic vs nonbiologic | 6.38 (1.10–36.89) | 9.22 (1.77–48.10) |

| Nonbiologic vs no treatment | 1.74 (0.25–12.18) | 1.75 (0.26–11.64) | ||||||||||

| Pneumonia | 47 (17) | 6833 | 6.9 (4.9–8.8) | 101 (36) | 10,782 | 9.4 (7.5–11.2) | 129 (47) | 12,969 | 9.9 (8.2–11.7) | Biologic vs no treatment | 0.71 (0.50–1.02) | 1.05 (0.73–1.50) |

| Nonbiologic vs no treatment | 1.05 (0.79–1.39) | 1.13 (0.85–1.50) | ||||||||||

| Sepsis | 46 (22) | 6847 | 6.7 (4.8–8.7) | 73 (35) | 10,893 | 6.7 (5.2–8.2) | 90 (43) | 13,155 | 6.8 (5.4–8.3) | Biologic vs nonbiologic | 0.89 (0.60–1.32) | 1.31 (0.89–1.92) |

| Nonbiologic vs no treatment | 0.90 (0.65–1.26) | 0.95 (0.68–1.32) | ||||||||||

| Renal and urinary tract | 29 (16) | 6839 | 4.2 (2.7–5.8) | 59 (32) | 10,879 | 5.4 (4.0–6.8) | 99 (53) | 13,084 | 7.6 (6.1–9.1) | Biologic vs nonbiologic | 0.71 (0.45–1.11) | 1.12 (0.71–1.78) |

| Nonbiologic vs no treatment | 1.27 (0.91–1.79) | 1.35 (0.96–1.89) | ||||||||||

| All serious infections|| | 108 (20) | 6646 | 16.3 (13.2–19.3) | 189 (36) | 10,570 | 17.9 (15.3–20.4) | 234 (44) | 12,501 | 18.7 (16.3–21.1) | Biologic vs no treatment | 0.95 (0.74–1.21) | 1.31 (1.02–1.68) |

| Nonbiologic vs no treatment | 1.12 (0.91–1.39) | 1.20 (0.97–1.49) | ||||||||||

aHR, Adjusted hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; IR, incidence rate; KPNC, Kaiser Permanente Northern California.

Adjusted for age, sex, race, baseline BMI, coronary artery disease, diabetes, dyslipidemia, hypertension, and cigarette use.

Follow-up years.

Incidence rate per 1000 person years. Events were attributed to biologics if the event occurred during a period when the patient was considered to be using a biologic medication (with or without concurrent use of nonbiologic psoriasis treatment medications). Events were attributed to nonbiologics if the event occurred during a period when the patient was considered to be using nonbiologic psoriasis treatment medication (without concurrent use of biologics). Events were attributed to ‘‘no treatments’’ if the event occurred during a period when the patient was not actively prescribed a biologic or nonbiologic agent.

Nonbiologics versus no systemic treatment.

Incidence rate is for the first occurrence of any of the outcomes; thus, the number of events in each category may not equal the sum of the total number of events.

Fig 1.

Crude hazard ratios (HRs) and adjusted HRs (aHRs) of serious infections for biologic versus nonbiologic therapy HRs were calculated using Cox proportional hazards regression models, accommodating right-censoring. Adjusted HRs were calculated by including the following covariates: age, sex, race, and baseline risk factors. Meningitis HRs and aHRs are not displayed here, as confidence intervals were wide on account of the limited number of events. SSTI, Skin and soft tissue infection.

DISCUSSION

In this large cohort study of systemically treated patients with psoriasis in a real-world, community-based setting, we have shown that there is an overall increased risk for serious infection while undergoing biologic therapy compared with when undergoing nonbiologic therapy. This increased risk for serious infection was driven primarily by SSTIs, as patients with psoriasis who were actively taking biologics had a 75% increased risk for development of SSTIs compared with users of nonbiologics. An increased risk for meningitis among users of biologics was also observed. However, these results are based on only 7 patients with meningitis, yielding unstable regression estimates, wide confidence intervals, and the inability to adjust for potential confounders. Thus, the meningitis results must be interpreted with caution.

Biologic therapies principally work by blocking specific cytokines, influencing T-cell activation and differentiation, or depleting disease-causing B cells, and such immunomodulation may increase serious infection risk.14 The relationship between serious infection and biologics is established in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and Crohn’s disease, with estimated infection estimates ranging from 1.1% to 5.6% and 4% to 4.9%, respectively.8–10,15 However, previous epidemiologic studies on infectious outcomes in patients with psoriasis who were receiving biologics have yielded conflicting results.11,12,16–20 A large, prospective cohort study discovered an elevated risk for serious infection (most commonly cellulitis and pneumonia) with the TNF-α inhibitor adalimumab compared with systemic retinoid and/or phototherapy, but this increased risk was not observed in biologic-naive subjects.12 In contrast, meta-analyses of several registries found no increased risk for serious infection with biologics.11,21 A possible explanation for this difference is that the former study had a less restrictive definition of serious infection (ie, patients did not need to be hospitalized), which may have captured more adverse events. With regard to SSTIs, patients with psoriasis develop serious cellulitis infections at 3 times the rate at which patients without psoriasis develop them.22 Data from our study suggest that biologics lead to an additional increased risk for SSTIs, a finding previously established in patients with rheumatoid arthritis.8 The specific increase in SSTIs is suggestive of unique roles of TNF-α and the other cytokines inhibited by biologics in the cutaneous immune environment. Specifically, TNF-α mediates inflammatory cell recruitment to the skin and directs antigen-presenting Langerhans cells from the epidermis to draining lymph nodes. Thus, there is a known mechanism of action that could explain our findings, namely, that inhibition of TNF-α could lead to increased risk for cutaneous infections.

Major strengths of this study included both the study population, which was large with a long follow-up time (29,717 person-years of follow-up) and racially and ethnically diverse, and the study setting, which was a real-world integrated health care delivery system with the ability to accurately and completely capture serious adverse infectious outcomes that had stringent definitions and were restricted to incident disease, thus minimizing overestimation of risk. The study findings may not be generalized to uninsured populations or patients with psoriasis with significant comorbid conditions. However, many patients with significant comorbid conditions would not be good candidates for biologic therapy and would likely have higher rates of serious infection.23 We also did not have specific measures of psoriasis severity and utilized systemic therapy prescriptions as a proxy for moderate-to-severe disease, but this definition has been successfully used in prior work.24 Another strength of this study is that dispensation of medication was well documented, although we did not have self-reported utilization. Given that KPNC is a prepaid system with comprehensive health care delivery, health plan members were unlikely to receive inpatient care or fill prescriptions outside the system.25 Protocol and institutional limitations precluded investigation of individual drug effects, which is a topic for future investigations.12,17,18,26,27

In summary, our findings suggest that in systemically treated psoriasis, use of a biologic compared with use of a nonbiologic increases the risk for overall serious infections, and more specifically SSTIs. Although the risk for meningitis was also increased, the number of events in this study was low. Patients with an underlying increased risk for SSTIs, such as persons with diabetes, peripheral vascular disease, and obesity may benefit from increased counseling about the risk for SSTIs. Dermatologists may want to discuss these increased risks with their patients with psoriasis, counsel them about early signs of infection, and monitor them for SSTIs during the course of their biologic therapy.

Acknowledgments

Supported by Pfizer Inc and the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (grant K24 AR069760 to MA).

Abbreviations used

- aHRs

adjusted hazard ratios

- CI

confidence interval

- IL

interleukin

- IR

incidence rate

- KPNC

Kaiser Permanente Northern California

- SSTI

skin and soft tissue infection

- TNF-α

tumor necrosis factor alpha

Footnotes

Reprints not available from the authors.

Disclosure: In addition to research support from Pfizer Inc, Dr Asgari and Dr Quesenberry have received research support from Valeant Pharmaceuticals and Mr Ray has received research support from Merck & Co, Genentech, and Purdue Pharma. Dr Geier is an employee of Pfizer, Inc. Dr Dobry has no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Rapp SR, Feldman SR, Exum ML, Fleisher AB, Jr, Reboussin DM. Psoriasis causes as much disability as other major medical diseases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41(3 Pt 1):401–407. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(99)70112-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yeung H, Takeshita J, Mehta NN, et al. Psoriasis severity and the prevalence of major medical comorbidity: a population-based study. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149(10):1173–1179. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2013.5015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Langley RG, Krueger GG, Griffiths CE. Psoriasis: epidemiology, clinical features, and quality of life. Ann Rheum Dis. 2005;64(suppl 2):ii18–ii23. doi: 10.1136/ard.2004.033217. discussion ii24–ii5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Administration, T.U.S.F.a.D. Clinical Review of Biologic License Application STN 12507/0 Efalizumab for Moderate to Severe Chronic Plaque Psoriasis. Rockville MD: US Food and Drug Administration; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Administration, T.U.S.F.a.D. Final Clinical Review Biologic License Application STN BL 125036/0 for Alefacept for Treatment of Moderate to Severe Chronic Plaque Psoriasis. Rockville, MD: US Food and Drug Administration; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Victor FC, Gottlieb AB, Menter A. Changing paradigms in dermatology: tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-alpha) blockade in psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis. Clin Dermatol. 2003;21(5):392–397. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2003.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.García-Doval I, Hernández MV, Vanoclocha F, et al. Should tumour necrosis factor antagonist safety information be applied from patients with rheumatoid arthritis to psoriasis? Rates of serious adverse events in the prospective rheumatoid arthritis BIOBADASER and psoriasis BIOBADADERM cohorts. Br J Dermatol. 2017;176(3):643–649. doi: 10.1111/bjd.14776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dixon WG, Watson K, Lunt M, et al. Rates of serious infection, including site-specific and bacterial intracellular infection, in rheumatoid arthritis patients receiving anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy: results from the British Society for Rheumatology Biologics Register. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54(8):2368–2376. doi: 10.1002/art.21978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.van Dartel SA, Fransen J, Kievit W, et al. Difference in the risk of serious infections in patients with rheumatoid arthritis treated with adalimumab, infliximab and etanercept: results from the Dutch Rheumatoid Arthritis Monitoring (DREAM) registry. Ann Rheum Dis. 2013;72(6):895–900. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-201338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Listing J, Strangfeld A, Kary S, et al. Infections in patients with rheumatoid arthritis treated with biologic agents. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52(11):3403–3412. doi: 10.1002/art.21386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Garcia-Doval I, Cohen AD, Cazzaniga S, et al. Risk of serious infections, cutaneous bacterial infections, and granulomatous infections in patients with psoriasis treated with anti-tumor necrosis factor agents versus classic therapies: prospective meta-analysis of Psonet registries. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76(2):299–308. e16. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2016.07.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kalb RE, Fiorentino DF, Lebwohl MG, et al. Risk of serious infection with biologic and systemic treatment of psoriasis: results from the Psoriasis Longitudinal Assessment and Registry (PSOLAR) JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151(9):961–969. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2015.0718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gordon NP. Similarity of the adult Kaiser Permanente membership in Northern California to the insured and general population in Northern California: statistics from the 2007 California Health Interview Survey. Internal Division of Research Report, 2012. Oakland, CA: Kaiser Permanente Division of Research; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fathi R, Armstrong AW. The role of biologic therapies in dermatology. Med Clin North Am. 2015;99(6):1183–1194. doi: 10.1016/j.mcna.2015.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Galloway JB, Mercer LK, Moseley A, et al. Risk of skin and soft tissue infections (including shingles) in patients exposed to anti-tumour necrosis factor therapy: results from the British Society for Rheumatology Biologics Register. Ann Rheum Dis. 2013;72(2):229–234. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2011-201108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gottlieb AB, Evans R, Li S, et al. Infliximab induction therapy for patients with severe plaque-type psoriasis: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;51(4):534–542. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2004.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reich K, Nestle FO, Papp K, et al. Infliximab induction and maintenance therapy for moderate-to-severe psoriasis: a phase III, multicentre, double-blind trial. Lancet. 2005;366(9494):1367–1374. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67566-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barker J, Hoffmann M, Wozel G, et al. Efficacy and safety of infliximab vs. methotrexate in patients with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis: results of an open-label, active-controlled, randomized trial (RESTORE1) Br J Dermatol. 2011;165(5):1109–1117. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2011.10615.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shear NH, Hartmann M, Toledo-Bahena M, et al. Long-term efficacy and safety of infliximab maintenance therapy in patients with plaque-type psoriasis in real-world practice. Br J Dermatol. 2014;171(3):631–641. doi: 10.1111/bjd.13004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Menter A, Feldman SR, Weinstein GD, et al. A randomized comparison of continuous vs. intermittent infliximab maintenance regimens over 1 year in the treatment of moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56(1):31e1–e15. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2006.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yiu ZZ, Exton LS, Jabbar-Lopez Z, et al. Risk of serious infections in patients with psoriasis on biologic therapies: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Invest Dermatol. 2016;136(8):1584–1591. doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2016.03.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wakkee M, Wakkee M, de Vries E, van den Haak P, Nijsten T. Increased risk of infectious disease requiring hospitalization among patients with psoriasis: a population-based cohort. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65(6):1135–1144. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2010.08.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Garcia-Doval I, Carretero G, Vanaclocha F, et al. Risk of serious adverse events associated with biologic and nonbiologic psoriasis systemic therapy: patients ineligible vs eligible for randomized controlled trials. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148(4):463–470. doi: 10.1001/archdermatol.2011.2768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gelfand JM, Wan J, Callis Duffin K, et al. Comparative effectiveness of commonly used systemic treatments or phototherapy for moderate to severe plaque psoriasis in the clinical practice setting. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148(4):487–494. doi: 10.1001/archdermatol.2012.370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moffet HH, Adler N, Schillinger D, et al. Cohort profile: the Diabetes Study of Northern California (DISTANCE)—objectives and design of a survey follow-up study of social health disparities in a managed care population. Int J Epidemiol. 2009;38(1):38–47. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyn040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Reich K, Wozel G, Zheng H, van Hoogstraten HJ, Flint L, Barker J. Efficacy and safety of infliximab as continuous or intermittent therapy in patients with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis: results of a randomized, long-term extension trial (RESTORE2) Br J Dermatol. 2013;168(6):1325–1334. doi: 10.1111/bjd.12404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Leonardi C, Papp K, Strober B, et al. The long-term safety of adalimumab treatment in moderate to severe psoriasis: a comprehensive analysis of all adalimumab exposure in all clinical trials. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2011;12(5):321–337. doi: 10.2165/11587890-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]