Abstract

Marital dissolution is commonly assumed to cause increased depression among adults, but causality can be questioned based on directionality and third variable concerns. The present study improves upon past research by using a propensity score matching algorithm to identify a sub-sample of continuously married participants equivalent in divorce risk to participants who actually experienced separation/divorce between two waves of the nationally representative study, Midlife Development in the United States (MIDUS). After correcting for participants’ propensity to separate/divorce, increased rates of depression at the second assessment were observed only among participants who were (a) depressed at the initial assessment, and (b) experienced a separation/divorce. Participants who were not depressed at the initial assessment but who experienced a separation/divorce were not at increased risk for a later major depressive disorder (MDE). Thus, both social selection and social causation contribute to the increased risk for a MDE found among separated/divorced adults.

Keywords: Midlife Development in the United States (MIDUS), marital separation, divorce, marital status, major depression, prospective studies

Stressful life events are associated with an increased risk for a range of mental health problems, including the first onset and recurrence of clinically significant mood disorders (Kendler, Hettema, Butera, Gardner, & Prescott, 2003; Mazure, 1998; Monroe & Simons, 1991). Within the broad class of potentially negative social upheavals, marital separation and divorce confer many adaptive challenges (Hetherington & Kelly, 2002). Separating from a spouse involves numerous logistical and financial burdens, and many people also face substantial emotional challenges, including grieving the end of the marriage, revising one’s self-identity, reforming social networks, and making major changes in parenting practices (Emery, 1994). Although most adults manage the transition of divorce well and can be described as resilient (Amato, 2010; Hetherington & Kelly, 2002; Mancini, Bonanno, & Clark, 2011), a subset of people become stuck on trajectories of long-term stress and strain (Lorenz, Wickrama, Conger, & Elder, 2006; Lucas, 2005). The extent to which this stress and strain translates into risk for a diagnosable mood disorder remains to be determined (e.g., Overbeek, Vollebergh, de Graaf, Scholte, de Kemp, & Engles, 2006).

A central and still unresolved question is whether the association between marital dissolution and mental health is a consequence of ending the marriage, or if the association can be eliminated by accounting for predictors of the divorce (Amato, 2010; Carr & Springer, 2010); that is, do variables that predict divorce (e.g., marital discord, neuroticism, hostility) also explain the putative consequences of divorce? Disentangling this issue of social selection and/or social causation is critical for the study of all non-random life events (e.g., Saudino, Pedersen, Lichtenstein, McClearn, & Plomin, 1997). The current study implements a propensity score analysis (Rosenbaum & Rubin, 1983) to investigate risk for a major depressive episode following marital separation and divorce using data from the large and representative Midlife Development in the United States (MIDUS) study. Combining data from the first and second wave of the MIDUS study allows us to examine whether changes in marital status are associated with changes in depression in a sample that is matched across its risk for divorce.

Although it is widely assumed that marital separation and divorce increase risk for diagnosable mood disorders, research on this topic is mixed. For example, using data from the Epidemiological Catchment Area study, Bruce and Kim (1992) reported that marital disruption was associated with increased risk for major depression, and especially first onset depression in men. These findings are consistent with evidence from other epidemiological and large-scale studies of risk for major depression (e.g., Asletine & Kessler, 1993; Breslau et al., 2011; Keller, Neale, & Kendler, 2007; Kendler et al., 1995; Kendler, Garnder, & Prescott, 2002; Weissman et al., 1996).

Other research, however, suggests these associations may be spurious. For example, Overbeek and colleagues (2006) found no association between divorce and subsequent major depressive illness; moreover, this study found that the association between divorce and dysthymia was eliminated by accounting for marital quality prior to the separation. This latter finding is consistent with evidence from prospective panel studies demonstrating that marital distress and variables that select people out of marriage explain the supposed consequences of divorce (e.g., Blekesaune & Barrett, 2005; Mastekaasa, 1994; Wade & Paevlin, 2004). Also consistent with these results is evidence demonstrating that heritability of divorce is largely explained by genetic factors contributing to the expression of personality (Jocklin, McGue, & Lykken, 1996).

For the most part, studies address questions of social selection via statistical control and the analysis of covariance (ANCOVA). Although this approach is common, its advisability is debatable and statistical equating of this nature can yield misleading results (see Miller & Chapman, 2002). An increasingly recognized alternative to studying non-random selection into “exposure events” is to conduct a propensity score analysis, and, especially, propensity score matching (PSM; Shadish, Clark, & Steiner, 2008; Thoemmes & Kim, 2011). Propensity scores have origins in counterfactual reasoning (see Oakes & Johnson, 2006) and are often used in non-experimental settings to equate groups of people that cannot be randomized. This approach typically involves predicting group membership from a specified set of variables, then matching people in terms of their propensity to, for example, become divorced. With matched samples (i.e., an exposure sample and a comparison sample) that are equivalent in terms of their propensity for the exposure, we can then determine whether the exposure is associated with outcomes of interest. Propensity scores are ideally suited for examining the association between divorce and risk for major depression: adults cannot be randomly assigned to divorce, the experience of divorce is non-random, and there exists no clear answer about the magnitude of the risk— if any— linking divorce and subsequent mental health problems. Amato (2003) conducted propensity score analyses when examining the effect of parental divorce on children’s mental health outcomes (also see Frisco, Muller, & Frank, 2007), and here we conduct PSM analyses to study the association between divorce and a Major Depressive Episode (MDE) in adults.

The Present Study

Given the potential utility of PSM, we implemented this statistical approach to evaluate the mental health correlates of becoming separated or divorced using two waves of the MIDUS sample. First, we identified all married adults in the MIDUS I random digit dialing, twin, and metropolitan oversample subsamples who became separated or divorced prior to the MIDUS II assessment, which was a 9-year follow-up of the original MIDUS cohort. Using a set of predictor variables described in detail below, we then implemented the PSM matching algorithm to identify a sub-set of continuously married participants exhibiting the same propensity to divorce as those who became separated or divorced between the MIDUS assessments. With the matched samples, we then conducted a series of regression analyses to determine if becoming divorced remained a significant predictor of a MDE at the MIDUS II assessment. In addition, we explored the possibility that the propensity to divorce moderates the mood symptom correlates of divorce. Amato and Hohmann-Marriott (2007) found that adults in high conflict marriages reported an increase in life happiness following divorce, whereas adults in low conflict marriages reported a decrease. Here, we also sought to conduct a conceptual replication of this finding by determining if having a low propensity to divorce is associated with worse mood symptom outcomes when marriage comes to an end.

Method

Participants

The overall MIDUS I (M1) sample included 7,108 participants (3,395 men) who were an average age of 46.40 years old (SD = 13 years) when the initial phone interview was conducted in 1995–1996. The MIDUS sample is described in detail elsewhere (Brim, Ryff, & Kessler, 2004), and in the present report, we excluded anyone who was part of the MIDUS sibling sub-sample (n = 950) in order to conduct analyses using entirely independent data. In brief, participants were drawn from a nationally representative random-digit-dial sample of noninstitutionalized, English-speaking adults aged 25–74 in the United States and asked via telephone survey to provide information on the patterns, predictors, and consequences of midlife development in the areas of physical health, psychological well-being, and social responsibility. For the present study, we included adults in a national random digit dialing sample (n = 3,487) and oversamples from five metropolitan areas in the U.S. (n = 757). In addition, the MIDUS study includes a random sample of twin pairs (n = 1,914); to avoid problems associated with non-independent data, we randomly selected one twin from the pair for the present study. Of the 5,137 people identified from these sub-samples, 3,250 (1,779 men) were married at M1, and this group formed our baseline sample. Between 2004–2006, the MIDUS 2 (M2) longitudinal follow-up was conducted, and every attempt was made to contact all original participants. Data from both M1 and M2 includes information derived from a 30-minute phone interview with participants, as well as an extensive questionnaire regarding their psychological functioning. Of the participants married at M1, 2,346 completed the follow-up assessment, which represents 27% attrition from M1 to M2, a rate that approximates the attrition from the entire MIDUS study. Analyses of selective attrition revealed that women were significantly less likely to remain in the study, χ2 (1) = 23.90, p < .001. Three hundred forty-one participants were experiencing a MDE at M1, but there was no selective attrition between M1 and M2 as a function of mood disturbance, χ2 (1) = .61, p < .43. Participants who were not retained in M2 reported significantly less total household income at M1 (d = .16) and significantly less overall education (d = .21) at M1, but no differences were observed between participants completing and not completing the M2 assessment on any of the other variables reported in Table 1. At M1, participants reported having been married for an average of 23.42 years (SD = 13.18 years); thus, this sample is unique in that we study divorce in the context of long-term marriages.

Table 1.

Demographic and Psychological Characteristics of the MIDUS Sample by Marital Status

| Continuously Married (n = 1864) |

Became Separated/Divorced (n = 136)a |

|

|---|---|---|

| Demographic | ||

| Gender (% female) | 44 | 59*** |

| M1 Years Married | 24.17 ± 13.11 | 16.07 ± 10.63*** |

| M1 Age (mean ± SD years) | 46.77 ± 12.09 | 39.40 ± 9.33* |

| M1 Household income (mean ± SD $) | $88,115 ± $63,559 | $83,890 ± $59,386 |

| Education level (mean ± SD years in school) | 7.17 ± 2.43 | 6.66 ± 2.50* |

| Psychological | ||

| M1 PWB (mean ± SD) | 16.95 ± 2.21 | 16.56 ± 2.65 |

| M1 Depression (% with MDD diagnosis) | 9.81 | 14.70+ |

| M2 Depression (% with MDD diagnosis) | 8.40 | 22.05*** |

| M1 Perceived Marital Risk (mean ± SD) | 1.86 ± .61 | 2.23 ± .70*** |

| M1 Neuroticism (mean ± SD) | 2.20 ± .65 | 2.33 ± .66* |

| M1 Extraversion (mean ± SD) | 3.19 ± .55 | 3.17 ± .52 |

| M1 Openness (mean ± SD) | 3.01 ± .50 | 3.03 ± .47 |

| M1 Conscientiousness (mean ± SD) | 3.43 ± .42 | 3.39 ± .42 |

| M1 Agreeableness (mean ± SD) | 3.45 ± .49 | 3.39 ± .51 |

| M1 Perceived Control (mean ± SD) | −.02 ± .50 | .06 ± .53* |

| M1 Social Integration (mean ± SD) | 14.53 ± 4.14 | 12.85 ± 4.77*** |

| M1 Family Strain (mean ± SD) | 2.09 ± .59 | 2.13 ± .61 |

| M1 Alcohol Problems (mean ± SD) | .17 ± .56 | .28 ± .76* |

Note.

= p < .10;

= p < .05;

= p < .01;

= p < .001.

M1 = MIDUS I Sample; M2 = MIDUS 2 Sample; MDD = Major depressive divorce; PWB = Psychological Well-Being. a = All of these participants were married at M1.

The propensity score algorithm used in this study requires complete data on all covariates from all participants at M1. We identified adults who met this criterion, were married at M1 and separated or divorced at M2 (n = 136; 58 men). The M2 interview asked participants to report the year and month they last lived with their former partner. Using the M1 and M2 interview dates, two variables were computed for the separated/divorced sample: the number of days from M1 until the month of physical separation (M = 858, SD = 1,224) and the number of days from the separation to M2 (M = 2,432, SD = 1,512). On average, participants reported separating from their former spouse 2.5 years after the M1 interview, which was 6.8 years prior to their M2 interview. Thus, any unique effects of becoming separated/divorced on mood symptom changes are those that persist, on average, 6.5 years after the date of physical separation. The number of adults who provided complete data and remained married (without having divorced and remarried) from M1 to M2 was substantially larger (n = 1864; 993 men). Table 1 reports descriptive statistics for the separated/divorced and continuously married sub-groups on the variables examined in this study.

Measures

Demographic and psychosocial covariates

The MIDUS study assessed participants’ age, gender, total household income, and education, and length of marriage (Table 1). Several variables, all assessed at M1, were included as covariates for the propensity score matching algorithm (see Thoemmes, 2012). Perceived marital risk (see Rossi, 2001) at M1 was calculated as the mean of five Likert-type items (ranging from 1 = Never to 5 = All the time) that assessed the degree to which participants thought their marriage might be at risk of ending in divorce (e.g., “During the past year, how often have you thought your relationship might be in trouble?”). This scale had adequate internal reliability (α = .69). Participants were asked how much each of 30 self-descriptive adjectives described them, and we included assessments of neuroticism, extraversion, openness to experience, agreeableness, and conscientiousness (Chapman, Fiscella, Kawachi, & Duberstein, 2010; Lachman & Weaver, 1997). The personality scales had internal consistency scores ranging from .58 (for conscientiousness) to .80 (for agreeableness). Perceived control (α = .80) was measured by combining four items assessing personal mastery (e.g., “I can do just about anything I set my mind to.”) and eight items assessing perceived constraints (e.g., “I often feel helpless in dealing with the problems of life.”; see Lachman & Weaver, 1998); scores on the master and constraint scales were standarized, then the perceived control scale was calculated as the mean of these composites. Social integration (α = .73) was assessed using three items, scored on a 7-point Likert type scale, assessing participants’ perceptions of social integration (“I don’t feel I belong to anything I’d call a community”; “I feel close to many people in my community”; and, “My community is a source of comfort”). The social integration scale is part of a larger social well-being inventory (Keyes & Shapiro, 2004). Family strain (α = .80) was assessed using four items tapping the degree to which participants perceive that family members make demands on them, are critical of them, get on their nerves, and let them down (Grzywacz & Marks, 1999; Walen & Lachman, 2000). Finally, an index of problem drinking (α = .69) was calculated by taking the sum of five items asking participants if they experienced problems associated with excessive drinking and if they experienced withdrawal or tolerance symptoms (see Selzer, 1971).

Primary outcome variable

Major depression was the primary outcome in this study. MIDUS used the World Health Organization Composite International Diagnostic Interview-Short Form (CITI-SF; Kessler, Andrews, Mroczek, Ustun, & Wittchen, 1998), which assesses the presence of a Major Depression Episode (MDE) in the prior 12 months as defined by the third edition-revised of the American Psychiatric Association’s (1987) Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Disorders III-R (see Kessler, DuPont, Berglund, & Wittchen, 1999). The CITI-SF has a stem-branch structure. During a telephone interview, participants were first asked about the presence of sad/depressed affect that was particularly intense and was experienced every day or nearly every day for at least a 2-week period. Participants were also asked a stem question about the presence of anhedonia, defined as the near complete loss of interest in more activities almost every day or every day for a 2-week period. The diagnosis of a MDE requires a period of at least two weeks of either depressed mood or anhedonia most of the day, nearly every day, and a series of at least four other associated symptoms typically found to accompany depression (e.g., loss of appetite, sleep problems, irritability). The CITI-SI has demonstrated strong sensitivity and specificity (Kessler et al., 1998). The same items were assessed in both M1 and M2, thus allowing for the diagnosis of a past-year MDE at both points.

Propensity Score Matching (PSM)

We implemented the PSM algorithm outlined in Thoemmes (2012). With the exception of the MDE variable, we selected all M1 variables reported in Table 1 as covariates for the creation of the propensity score.1 The predicted scores from this analysis represent the propensity for anyone in the larger sample to experience a marital separation or divorce between M1 and M2. We then used a nearest neighbor matching algorithm to match each person in the separated/divorced group to a person in the continuously married group who had the closest propensity score. To increase the power to detect moderated effects in the final sample, we used a 4:1 matching ratio that resulted in 4 married participants to every separated/divorced participant. The PSM analyses were conducted using the custom SPSS 20.0 custom psmatching dialog created by Theommes (2012), which opens the SPSS R-Plugin and executes R computer code for the analyses. Once the PSM was complete, all of the significant mean differences between groups (reported in Table 1) were eliminated.

Results

Table 1 presents the descriptive statistics for the married and divorce sub-samples on all covariate, predictor, and outcome variables prior to the PSM. Relative to adults who remained married between the M1 and M2 assessments, those who became separated or divorced were significantly more likely to be female, younger, and married for fewer years. They reported significantly greater neuroticism, alcohol problems and marital dissatisfaction, lower levels of PWB, lower overall education, and less social integration but greater perceived control at M1. Participants who became divorced also showed a trend toward greater rates of depression at M1 (prior to their separation). After accounting for rates of depression at M1 but without adjusting for any of the other covariates, becoming separated/divorced was associated with a significant increase in the likelihood of being diagnosed with a MDE at M2, B = 1.09, SE = .23, p < .001, OR = 2.97, 95% CI = 1.89, 4.69. After accounting for depression at M1 as well as the 17 other covariates reported in Table 1, becoming separated/divorced remained significantly associated with an increase in the likelihood of being diagnosed with a MDE at M2, B = .81, SE = .25, p = .001, OR = 2.29, 95% CI = 1.41, 3.75.

Having established a basic association between changes in marital status and increases in the likelihood of being depressed in the M2 assessment in the overall sample, we then conducted the propensity score matching process described above. The propensity score matching process yielded a reduced data set (n = 680) in which the married and divorced groups have an equal propensity to experience divorce. Among people with an equal propensity to divorce, the effect of becoming divorced on depression at M2 (after accounting for depression at M1 and participants’ propensity score) was significant, B = .78, SE = .26, p = .003, OR = 2.18, 95% CI = 1.31, 3.63. In the same model, participants’ continuous propensity score also was significantly associated with risk of being depressed at M2, B = 3.07, SE = .35, p = .02, OR = 21.58, 95% CI = 1.62, 287.83.

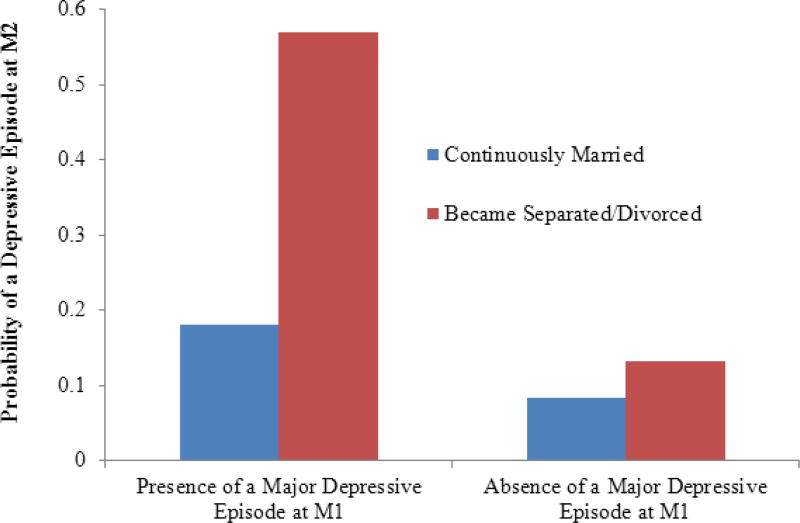

We found no evidence for a Propensity Score X Marital Status interaction, B = −.80, SE = 2.50, p = .74. We then explored the possibility that becoming divorced interacted with depression at M1 to predict depression at M2. After controlling for participants’ sex, the propensity to divorce score, and the main effects of depression at M1 and marital status, the M1-MDE X Marital Status interaction was significant, B = −1.27, SE = .65, p = .048, OR = .27, 95% CI = .08, .69. In this model, the main effect of marital status was qualified by the interaction: the effect of separation/divorce on depression at M2 varied as a function of depression at M1. The simple slope deconstruction of this interaction is illustrated in Figure 1. For participants without a history of depression at M1, rates of depression did not differ at M2 as a function of change in marital status, Z = 1.63, p = .10. In contrast, for participants with a history of depression at M1, rates of depression differed substantially at M2 as function of change in marital status, Z = 3.16, p = .002. When the pairwise comparisons are reversed, we see that among participants who became divorced, those who experienced a prior MDE at M1 were significantly more likely to experience a MDE at M2 relative to divorced/separated adults who were not depressed at M1, Z = 3.86, p = .0001. As shown in Figure 1, nearly 6 of 10 people who were depressed at M1 and then experienced a divorce between M1 and M2 were again depressed at M2. For all other participants (including people with a history of depression at M1 but no divorce and people without a history of depression at M1 who then divorced), the risk for a MDE at M2 was equivalent, roughly around 1 to 2 of 10 participants.

Figure 1.

Probability for a Major Depressive Episode (MDE) at MIDUS II (M2) as a function of participants’ marital status and depression at MIDUS I (M1). The greatest risk for a MDE was observed among people who experienced a separation/divorce between M1 and M2 and who also experienced a MDE at M1.

Finally, to examine the potential utility of the propensity score analyses over-and-above ANCOVA, we re-tested the M1-MDE X Marital Status interaction using the full sample of participants who were unmatched in terms of their propensity to divorce. After controlling for all of the M1 covariates listed in Table 1, the main effects of depression at M1 and marital status, the M1-MDE X Marital Status interaction was not significant, B = −.89, SE = .60, p = .14, OR = .41. Thus, the PSM approach used here provides a different account of the interaction between depression and changes in marital status in the MIDUS sample than that derived from ANCOVA alone.

Discussion

Using data from the nationally representative MIDUS study, we replicated prior findings showing that the end of marriage through divorce is associated with a significant increase in the probability of a future depressive episode (see Keller, Neale, & Kendler, 2007; Bruce & Kim, 1992). After implementing a propensity score matching (PSM) algorithm (Thoemmes, 2012) that identified a group of married adults who have an equivalent likelihood to experience marital separation and/or divorce in the future, the end of marriage was only associated with an increased likelihood of a future depressive episode among adults who experienced a MDE at M1. This interaction was revealed using PSM but was not observed when we conducted ANCOVA with the full sample; thus, the PSM approach provides an alternative—and perhaps more nuanced—account of the association between separation/divorce and subsequent mood disturbance than the picture emerging from more commonly used data analytic approaches in this area.

Although we expected to provide a conceptual replication of Amato and Hohmann-Marriott’s (2007) findings by showing that people with less of a propensity to divorce have a greater risk for depression when they divorced, we found no evidence for this process with respect to depression. Amato and Hohmann-Marriott (2007) investigated happiness as their primary outcome, and it may well be that the end of higher quality marriages predicts lower levels of happiness but not the onset of clinically significant depression. The results of this report paint a picture that is entirely consistent with both diathesis-stress (Monroe & Simons, 1991) and stress generation models (Hammen, 1991) of mood disturbance. The propensity analyses indicated that a number of the covariates listed in Table 1 (including, for example, neuroticism, social integration, and psychological wellbeing at M1) contributed to the propensity to divorce; in the full sample, both participants’ propensity score and becoming separated/divorced were uniquely associated with increased risk for a MDE at M2.

When we conducted additional analyses using the sub-sample (n = 680) matched for their propensity to divorce, the main effect of becoming separated/divorce was qualified by a significant interaction with depression at M1. (This interaction was not significant in the full sample using participants unmatched in their propensity to separate/divorce.) Elevated risk for a MDE at M2 was observed only among people who were depressed at M1 and who experienced a separation/divorce between the two MIDUS waves. People without a history of depression at M1 and who experienced this life event, then, may have the emotional and social wherewithall to cope well with the upheaval of divorce. In contrast, when adults with a history of depression faced this stressful life event, they may have done so with a limited capacity to cope with the demands of the transition out of marriage. This perspective raises the possibility that the separation itself does not give rise to depression, but instead it is the chronic difficulties that typically follow a marital separation (e.g., Lorenz et al., 2006) that play a causl role in episode reccurence among people with a history of depression. Consistent with this reasoning, Monroe, Slavich, Torres, and Gotlib (2007) found that major chronic difficulties, not major life events themselves, were most highly associated with depression recurrence.

Given the findings in this report, our position is that the duality between social selection and social causation explanations is misplaced (also see Blekesaune, 2008). As shown in Figure 1, adults with a history of depression at M1 who do not ultimately separate/divorce show no difference in rates of depression when compared to adults without a history of depression at M1.2 In this case, it is the divorce that potentiates the underlying risk, but, in-and-of itself, this life event does not appear associated with increased rates of depression (i.e., separated or divorced adults without a history of depression are not at significantly increased risk for depression at M2).3 A critical next step in this line of work is to evaluate the mediational processes that explain why only divorcing adults with a history of depression are at particular risk for a depressive episode post-divorce. Do the processes that give rise to the propensity to divorce (for example, lack of social support as one of many possibilities), also explain why this event correlates with a risk for future depression? This question remains open for investigation, and the key contribution of this paper is demarcating who is at greatest risk for subsequent psychopathology when marriage comes to an end.

The rates of depression observed in this sample are non-trivial, and the findings have clear clinical implications. We suggest that clinicans working with divorcing adults carefully assess depression history; although this study does not include all prior MDEs for every participant, we observed here that as little as a single prior MDE can increase risk substantially for a subsequent episode following divorce. If an adult in midlife experiences a separation/divorce and does not also report a history of prior MDEs, our findings suggest that the risk of a MDE in the years following the separation/divorce is fairly minimal.

The findings reported here should be interpreted in light of the study’s limitations. First, the group of separated/divorced adults was relatively small. Furthermore, to increase the size of this group, we combined separated and divorced adults into one group. Although doing so is an accepted approach to studying marital transitions (e.g., Sbarra, Law, Lee, & Mason, 2009), collapsing across marital status in this way may blur potentially interesting differences between those adults separated from their spouse relative to those adults who have experienced legal divorce. Second, although the MIDUS data provide a rich resource for asking prospective research questions, the gap between the assessments is too long to capture short-term change or any anticipation effects (i.e., distress pre-dating the separation experience). For example, using 15 waves of data from the British Household Panel Study, Blekesaune (2008) found that the emotional distress associated with the end of marriage was relatively short-lived. The present study focuses on clinical distress and it is likely that the processes leading to diagnosable mood disturbance are different than those that unfold as part of a normative grief response. Furthermore, as noted above, it is possible that the high rates of depression observed among people who separated/divorced with a history of depression follow from the stressors and major difficulties associated with divorce, not the life event itself (cf. Monroe et al., 2007). Nevertheless, it is important to recognize that the present study is limited in its assessment of the temporal dynamics of the findings. Third, although the MIDUS study includes a representative sample of community-dwelling adults, participants were, on average in their late forties. Thus, this paper focuses on divorce within relatively stable marriages. As married adults age, they are less likely to become divorce (Heaton, 2002) and the extent to which these results can apply to younger cohorts remains to be determined. Finally, although we used a large set of covariates to conduct our PSM analyses, this approach cannot account for all of the variables contributing to the selection out of marriage. Thus, it is possible that the inclusion of other variables in the PSM algorithm would alter the results of the current study.

Conclusion

Using data from the nationally representative MIDUS study, this report investigated whether accounting for the propensity to experience marital separation/divorce altered the association between marital dissolution and risk for major depression. Although the prospective association between separation/divorce and major depression at M2 was significant in both unadjusted and covariance analyses, after implementing a propensity score matching (PSM) algorithm we observed the main effect of separation/divorce to be qualified by a significant interaction with depression at the start of the study. Elevated risk for a MDE at M2 was observed only among people who were depressed at M1 and who also experienced a separation/divorce between the two MIDUS waves. Adults with a history of depression at M1 who did not ultimately divorce showed no difference in rates of depression compared to adults without a history of depression at M1. In this case, it is the divorce that potentiates the underlying risk, but, in-and-of itself, this life event does not appear associated with increased rates of depression (i.e., separated or divorced adults without a history of depression do not have a significantly increased risk for depression at M2). These findings are consistent with both diathesis-stress and stress generation models of mood disturbance, and this research provides a more nuanced account of how social selection and social causation processes may work in combination to increase risk for major depression following marital separation and divorce.

Acknowledgments

The first author’s work on this paper was supported in part by grants from the National Science Foundation (BCS90023;0919525), the National Institute on Aging (#036895), and the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development (#069498). Christopher R. Beam was supported by Award Number T32AG020500 from the National Institute on Aging. We wish to thank Felix Thoemmes for helpful consultation on the application of his propensity score matching algorithm, as well as the Evaluation and Data Analysis Group at the University of Arizona. MIDUS is the main research activity of the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation Network on Successful Midlife Development (MIDMAC). For the present analyses, the publicly available versions of MIDUS were used: Lachman, Markus, Marmot, Rossi, Ryff, and Shweder. National Survey of Midlife Development in the United States (MIDUS), 1995–1996 [Computer file]. ICPSR02760-v6. Ann Arbor, MI: Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research [distributor], 2010-01-06.

doi:10.3886/ICPSR02760 downloaded on November 9, 2010. The authors had access to all publicly available data and were responsible for all data analysis and report writing.

Footnotes

Given that our ultimate goal was to predict variation in MDEs at M2 as a function of the propensity score, using the MDE item at M1 to compute the propensity would introduce bias in these analyses. Because the residualized regression (predicting MDEs at M2) will include depression at M1, including this variable in the propensity score algorithm prevents a clear examination of whether separation/divorce interacts primarily with prior depression, or with the other factors examined on the propensity score index. Thus, we accounted for MDE at M1 in the final logistic regression model but did not use this item to create the propensity score.

Depression at M1 is very highly associated with depression at M2. Therefore, even though the M1-MDE X Marital Status interaction is significant, the main effect of M1-MDE remains highly significant as well.

Consistent with the points raised in Footnote #2, when we re-run this analysis with the entire sample (i.e., not just those participants identified as having an equivalent propensity to separation/divorce), the probability for depression among people with a MDE at M1 who do not divorce increases to 2.0 of 10 people. The probability of depression at M2 among the high-risk group experiencing a MDE at M1 and subsequent separation/divorce is slightly reduced to 5.0 of 10 people.

References

- Amato PR. Reconciling divergent perspectives: Judith Wallerstein, quantitative Family research, and children of divorce. Family Relations. 2003;52:332–339. [Google Scholar]

- Amato PR. Research on divorce: Continuing trends and new developments. Journal of Marriage & Family. 2010;72:650–666. [Google Scholar]

- Amato PR, Hohmann-Marriott B. A comparison of high- and low-distress marriages that end in divorce. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2007;69:621–638. [Google Scholar]

- Aseltine RH, Kessler RC. Marital disruption and depression in a community sample. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1993;34:237–251. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkman LF, Glass T, Brissette I, Seeman TE. From social integration to health: Durkheim in the new millennium. Social Science & Medicine. 2000;51:843–857. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(00)00065-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blekesaune M. Partnership transitions and mental distress: Investigating temporal order. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2008;70:879–890. [Google Scholar]

- Blekesaune M, Barrett AE. Marital dissolution and work disability: A longitudinal study of administrative data. European Sociological Review. 2005;21(3):259–271. [Google Scholar]

- Booth A, Amato P. Divorce and psychological stress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1991;32:396–407. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breslau J, Miller E, Jin R, Sampson N, Alonso J, Andrade L, et al. A multinational study of mental disorders, marriage, and divorce. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2011;124:474–486. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2011.01712.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brim OG, Ryff CD, Kessler RC. How healthy are we?: A national study of well-being at midlife. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Carr D, Springer KW. Advances in families and health research in the 21st century. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2010;72:743–761. [Google Scholar]

- Chapman BP, Fiscella K, Kawachi I, Duberstein PR. Personality, socioeconomic status, and all-cause mortality in the united states. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2010;171:83–92. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwp323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emery RE. Renegotiating family relationships: Divorce, child custody, and mediation. New York: Guilford Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Emery RE. The truth about children and divorce: Dealing with the emotions so you and your children can thrive. New York: Viking/Penguin; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Frisco ML, Muller C, Frank K. Parents’ union dissolution and adolescents’ school performance: Comparing methodological approaches. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2007;69:721–741. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2007.00402.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner J, Oswald AJ. Do divorcing couples become happier by breaking up? Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series A (Statistics in Society) 2006;169:319–336. [Google Scholar]

- Gove WR. Sex, marital status, and mortality. American Journal of Sociology. 1973;79:45–67. doi: 10.1086/225505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grzywacz JG, Marks NF. Family solidarity and health behaviors: Evidence from the National Survey of Midlife Development in the United States. Journal of Family Issues. 1999;20:243–268. [Google Scholar]

- Hammen C. Generation of stress in the course of unipolar depression. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1991;100:555–561. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.100.4.555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heaton TB. Factors contributing to increasing marital stability in the United States. Journal of Family Issues. 2002;23:392–409. [Google Scholar]

- Hetherington EM, Kelly J. For better or for worse: Divorce reconsidered. New York: Norton & Company; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Jocklin V, McGue M, Lykken DT. Personality and divorce: A genetic analysis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1996;71:288–299. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.71.2.288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson DR, Wu J. An empirical test of crisis, social selection, and role explanations of the relationship between marital disruption and psychological distress: A pooled time-series analysis of four-wave panel data. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2002;64:211–224. [Google Scholar]

- Keller MC, Neale MC, Kendler KS. Association of different adverse life events with distinct patterns of depressive symptoms. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2007;164:1521–1529. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.06091564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendler KS, Gardner CO, Prescott CA. Toward a comprehensive developmental model for major depression in women. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2002;159:1133–1145. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.7.1133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendler KS, Hettema JM, Butera F, Gardner CO, Prescott CA. Life event dimensions of loss, humiliation, entrapment, and danger in the prediction of onsets of major depression and generalized anxiety. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2003;60:789–796. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.8.789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendler K, Kessler R, Walters E, MacLean C, Neale M, Heath A, et al. Stressful life events, genetic liability, and onset of an episode of major depression in women. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1995;152:833–842. doi: 10.1176/ajp.152.6.833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Andrews G, Mroczek D, Ustun B, Wittchen H-U. The World Health Organization Composite International Diagnostic Interview Short Form (CIDI-SF) International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research. 1998;7:171–185. doi: 10.1002/mpr.168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, DuPont RL, Berglund P, Wittchen H-U. Impairment in pure and comorbid generalized anxiety disorder and major depression at 12 months in two national surveys. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1999;156:1915–1923. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.12.1915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Mickelson KD, Walters EE, Zhao S, Hamilton L. Age and depression in the MIDUS survey. In: Brim OG, Ryff CD, Kessler RC, editors. How healthy are we?: A national study of well-being at midlife. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 2004. pp. 227–251. [Google Scholar]

- Keyes CLM, Shapiro AD. Social well-being in the United States: A descriptive epidemiology. In: Brim O, Ryff C, Kessler R, editors. How healthy are we?: A national study of well-being at midlife. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 2004. pp. 350–373. [Google Scholar]

- Lachman ME, Weaver SL. The Midlife Development Inventory (MIDI) Personality Scales: Scale construction and scoring. Waltham, MA: Brandeis University; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Lachman ME, Weaver SL. The sense of control as a moderator of social class differences in health and well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1998;74:763–773. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.74.3.763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorenz FO, Wickrama KA, Conger RD, Elder GH., Jr The short-term and decade-long effects of divorce on women's midlife health. J Health Soc Behav. 2006;47:111–125. doi: 10.1177/002214650604700202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucas RE. Time does not heal all wounds: A longitudinal study of reaction and adaptation to divorce. Psychological Science. 2005;16:945–950. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2005.01642.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald G, Leary MR. Why does social exclusion hurt? The relationship between social and physical pain. Psychological Bulletin. 2005;131:202–223. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.131.2.202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mancini AD, Bonanno GA, Clark AE. Stepping off the hedonic treadmill. Journal of Individual Differences. 2011;32:144–152. [Google Scholar]

- Mastekaasa A. Psychological well-being and marital dissolution. Journal of Family Issues. 1994;15:208. [Google Scholar]

- Mastekaasa A. Marital dissolution as a stressor: Some evidence on psychological, physical, and behavioral changes in the pre-separation period. Journal of Divorce & Remarriage. 1997;26:155–183. [Google Scholar]

- Mazure CM. Life stressors as risk factors in depression. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 1998;5:291–313. [Google Scholar]

- McFarlane AH, Bellissimo A, Norman GR. The role of family and peers in social self-efficacy. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 1995;65:402–410. doi: 10.1037/h0079655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menaghan EG, Lieberman MA. Changes in depression following divorce: A panel study. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1986;48:319–328. [Google Scholar]

- Miller GA, Chapman JP. Misunderstanding analysis of covariance. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2001;110:40–48. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.110.1.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monroe SM, Simons AD. Diathesis-stress theories in the context of life stress research: Implications for the depressive disorders. Psychological Bulletin. 1991;110:406. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.110.3.406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monroe SM, Slavich GM, Torres LD, Gotlib IH. Major life events and major chronic difficulties are differentially associated with history of major depressive episodes. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2007;116:116–124. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.116.1.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oakes JM, Johnson PJ. Propensity score matching for social epidemiology. In: MOakes J, Kaufman JS, editors. Methods in social epidemiology. Vol. 1. San Francisco, California: Josey-Bass; 2006. pp. 370–393. [Google Scholar]

- Overbeek G, Vollebergh W, de Graaf R, Scholte R, de Kemp R, Engels R. Longitudinal associations of marital quality and marital dissolution with the incidence of dsm-iii-r disorders. Journal of Family Psychology. 2006;20:284–291. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.20.2.284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbaum PR, Rubin DB. The central role of the propensity score in observational studies for causal effects. Biometrika. 1983;70:41–55. [Google Scholar]

- Saudino KJ, Pedersen NL, Lichtenstein P, McClearn GE, Plomin R. Can personality explain genetic influences on life events? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1997;72:196–206. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.72.1.196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sbarra DA, Law RW, Lee LA, Mason AE. Marital dissolution and blood pressure reactivity: Evidence for the specificity of emotional intrusion-hyperarousal and task-rated emotional difficulty. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2009;71:532–540. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181a23eee. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selzer ML. The Michigan Alcoholism Screening Test: The quest for a new diagnostic instrument. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1971;127:1653. doi: 10.1176/ajp.127.12.1653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shadish WR, Clark M, Steiner PM. Can nonrandomized experiments yield accurate answers? A randomized experiment comparing random and nonrandom assignments. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 2008;103:1334–1353. [Google Scholar]

- Simon RW. Revisiting the relationships among gender, marital status, and mental health. The American Journal of Sociology. 2002;107:1065–1096. doi: 10.1086/339225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strohschein L. Parental divorce and child mental health trajectories. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2005;67:1286–1300. [Google Scholar]

- Thoemmes FJ. Propensity score matching in SPSS. 2012 Retrieved from: http://sourceforge.net/p/psmspss/home/Home/

- Thoemmes FJ, Kim ES. A systematic review of propensity score methods in the social sciences. Multivariate behavioral research. 2011;46:90–118. doi: 10.1080/00273171.2011.540475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wade TJ, Pevalin DJ. Marital transitions and mental health. Journal of Health & Social Behavior. 2004;45:155–170. doi: 10.1177/002214650404500203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weissman MM, Bland RC, Canino GJ, Faravelli C, Greenwald S, Hwu HG, Yeh EK. Cross-national epidemiology of major depression and bipolar disorder. JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association. 1996;276:293–299. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]