Abstract

The treatment of ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) has advanced dramatically over the past 30 years since the introduction of reperfusion therapies, such that mechanical reperfusion with primary percutaneous coronary intervention is now the standard of care. With STEMI, as with other forms of acute coronary syndrome, stent deployment in culprit lesions is the dominant form of reperfusion in the developed world and is supported by contemporary guidelines. However, the precise timing of stenting and the extent to which both culprit and non-culprit lesions should be treated continue to be active areas of study. In this review, we revisit key data that support the use of mechanical reperfusion therapy in STEMI patients and explore the optimal timing for and extent of stent implantation in this complex patient group. We also review data surrounding the deleterious effects of untreated residual myocardial ischemia, the importance of complete revascularization, and the recent data exploring culprit-only versus multivessel stenting in the STEMI setting.

Keywords: stenting, PCI, STEMI, acute coronary syndrome, mechanical reperfusion

INTRODUCTION

Acute myocardial infarction (MI) was identified nearly 50 years ago as a coronary occlusive event resulting from atherosclerotic plaque rupture and thrombosis. This mechanistic understanding was essential to the development of reperfusion therapy for treating ST-segment elevation MI (STEMI)—a treatment that has revolutionized the care and outcomes in these patients. Widespread use of pharmacologic reperfusion therapy with fibrinolytic agents was introduced following the landmark GISSI and ISIS-2 trials, both of which demonstrated important absolute reductions in mortality of up to 3.5% if fibrinolytic agents could be administered promptly.1,2 The results of these and other seminal trials using modern fibrinolytic agents unequivocally established thrombolytic therapy as a cornerstone of STEMI management by the mid-1990s.3–6

During the same period, the concept of mechanical interventional therapies to dilate occlusive coronary stenoses began to take hold. Although this concept was initially deemed almost heretical, the development of guidewire and balloon technologies birthed the notion that mechanical reperfusion for acute MI might become a reality. The experiential “proof” that physical manipulation of coronary thrombosis could be achieved with specialized angioplasty tools ushered in the modern era of STEMI management—that of primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI).

In 1993, O'Neill and colleagues published an exploratory study of 56 patients who underwent balloon angioplasty within 12 hours of symptom onset in STEMI. Reperfusion was achieved in approximately 85% of both the primary PCI and streptokinase groups. Despite no differences between the two treatment modalities in symptom duration (3 h) or time to treatment (4 h), the thrombolytic therapy arm of the study experienced a high residual stenosis burden and worse ventricular function.7 Based on these novel findings, more than a dozen large clinical trials were undertaken throughout the next decade to demonstrate the superiority of primary PCI over thrombolytic therapy for the treatment of STEMI, with multiple studies demonstrating reductions in short-term death, non-fatal MI, and stroke.8

Keeley et al. published a seminal quantitative review of 23 studies spanning almost 20 years of work in STEMI reperfusion therapy. The review included studies that used more contemporary adjunctive medical therapies, fibrin-specific thrombolytic agents, and angioplasty with and without stenting.8 Of the 7,739 patients presenting with STEMI, 3,872 were treated with primary PCI and the remaining 3,867 were treated with thrombolytic therapy. A key feature of this study was an analysis excluding data from the SHOCK Trial, wherein participants were at a disproportionately higher risk of adverse outcomes based on the presence of cardiogenic shock. The authors noted a decrease in overall short-term death (7% vs 9%; P = .0002), nonfatal reinfarction (3% vs 7%; P < .0001), stroke (1% vs 2%; P = .0003), and a composite end point of all three of these adverse outcomes (8% vs 14%; P < .0001) in favor of primary PCI.8 These data led to a guideline change recommending primary PCI as a preferred reperfusion therapy for STEMI when provided within 90 minutes at experienced centers; they also spurred the rapid development of interventional therapies to treat acute MI lesions.9

BALLOON ANGIOPLASTY VERSUS ROUTINE STENT IMPLANTATION IN PRIMARY PCI FOR STEMI

As focus shifted to mechanical reperfusion in STEMI, increasing experience with percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty (PTCA) prompted the desire to further refine the PCI technique over PTCA alone, despite the lower rates of mortality, reinfarction, and cerebrovascular events achieved with PTCA over fibrinolytic therapy.10 While PTCA effectively achieved coronary flow and myocardial reperfusion, it was not perfect. For example, without mechanical stabilization of plaque in the lumen, PTCA alone could be associated with early ischemia/reinfarction, acute target vessel reocclusion, stent recoil, and late restenosis in STEMI patients.11,12 Accordingly, stent technologies, including the pioneering Palmaz-Schatz metallic stent, were developed to obviate these early and late complications of PTCA, with a focus on reducing the 50% restenosis rate of PTCA alone and the near 20% rate of target vessel revascularization (TVR) noted post PTCA in previous studies. Nonetheless, the application of stent technologies to PCI was first envisioned for use in stable patients and not in those undergoing STEMI PCI.

With the recognition that coronary stenting could stabilize the acute results of coronary PTCA in stable patients, this therapy was tested in the acute MI setting as well.13,14 The multicenter Stent Primary Angioplasty in Myocardial Infarction (STENT PAMI) trial randomized 900 patients with STEMI to routine stent implantation versus PTCA. Significantly lower rates of 30-day and 6-month recurrent ischemia and restenosis were noted in the stenting arm compared with the PTCA-alone arm (1.3% vs 3.8% and 7.7% vs 17%, respectively). There were no differences in the rates of mortality, cerebrovascular events, or reinfarctions between the groups. The primary end point, which was a composite of the above component events, was primarily driven by lower rates of TVR in the stenting-alone group.15 Notably, there was a lower rate of Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) grade 3 flow after stenting (94.6% vs 97% after PTCA; P = .054), with a trend towards decreased survival in these patients at 6 months. This trend may have been due in part to the absence of more potent antiplatelet therapies at the time of PCI. For example, glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors or contemporary P2Y12 inhibitors were used in a very small proportion of patients in this study.

In view of the STENT PAMI findings, the larger Controlled Abciximab and Device Investigation to Lower Late Angioplasty Complications (CADILLAC) trial randomized 2,082 patients, the majority of whom presented with STEMI, into 4 groups: PTCA alone (n = 518), PTCA plus abciximab (n = 528), stenting alone (n = 512), and stenting plus abciximab (n = 524).16 Compared to stenting alone, the PTCA-alone group was associated with an early increased rate of ischemic TVR at 30 days (1.6% vs 5.6%; P < .001) and a higher incidence of the composite end point (death from any cause, reinfarction, ischemia-driven TVR, or disabling stroke) at 6 months (11.5% vs 20%; P < .001). Unsurprisingly, the 6-month composite end point difference was driven by lower TVR rates in the stenting-alone versus PTCA-alone group (5.7 vs 16.9; P < .001). However, no significant differences in mortality, reinfarction, and disabling stroke rates were noted between the two groups. The results of this study ultimately furthered support for the use of stenting over PTCA in STEMI patients, with improved angiographic outcomes and higher rates of event-free survival achieved after stent implantation.

Meta-analyses combining the stenting versus PTCA data have largely confirmed these observations. Zhu and colleagues reported the outcomes of 4,120 acute MI patients from 9 studies and found a reduction in major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) by nearly 50% at 6 to 12 months (OR 0.52, 0.44–0.62, P < .001), which was driven by lower TVR rates.17 Subsequently, a definitive Cochrane meta-analysis of 4,433 patients from 9 randomized trials found lower rates of TVR at 30 days, 6 months, and 12 months with stenting compared with PTCA alone18 and lower reinfarction rates in the stenting group within the same time periods. Once again, there were no differences in mortality between the two groups. The study did, however, report a reduction of 12 reinfarction events and 144 TVR events per 1,000 STEMI patients treated with primary stenting rather than balloon angioplasty.18 Ultimately, the amalgamation of evidence regarding stenting in primary PCI for STEMI demonstrates superiority to PTCA alone, primarily through a reduction in repeat revascularization and reinfarction.

The ongoing development of stent technologies and the move from bare metal stents (BMS) to second-generation drug-eluting stents (DES) has led to further improvement in post-PCI outcomes and reductions in MACE. A large meta-analysis of 77 randomized clinical trials that enrolled patients requiring PCI for de novo coronary lesions revealed a reduction in myocardial infarctions and the need for TVR at a mean of 2.1 years of follow-up with the use of DES over BMS.19 Several studies have demonstrated similar findings in the setting of STEMI—particularly in patients with insulin-treated diabetes, a reference vessel diameter of less than 3.0 mm, and a total lesion length of over 30 mm—as noted in an analysis of 2-year follow-up data from the HORIZONS-AMI trial.20 Most recently, in a large-network meta-analysis of trials assessing the safety and efficacy of DES versus BMS in the setting of STEMI, Palmerini and colleagues found significantly lower rates of cardiac death or myocardial infarction and stent thrombosis in cobalt-chromium–based everolimus eluting stents (CoCr-EES) compared with both BMS and first-generation DES. Nearly all DES types also carried lower 1-year TVR rates than BMS. The authors concluded that DES (especially CoCr-EES) were superior to BMS in STEMI patients, with lower rates of MACE and improved efficacy seen at as little as 30 days from the index procedure and maintained for up to 2 years.21

DEFERRED VERSUS IMMEDIATE STENTING IN PRIMARY PCI

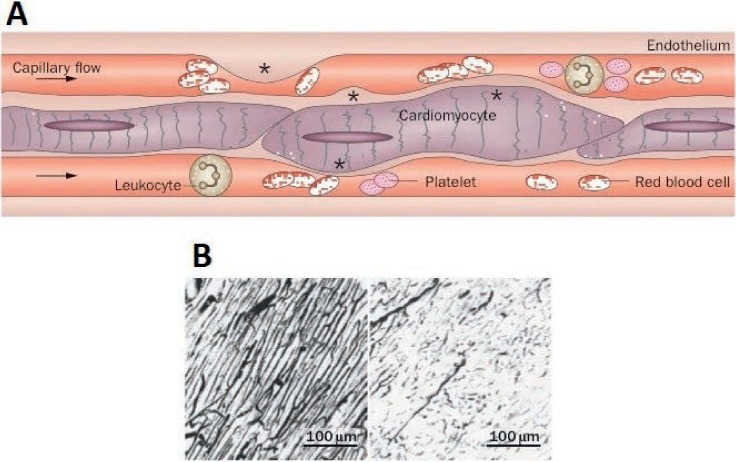

Despite the successes of primary PCI over fibrinolytic therapy and routine stent implantation for the reduction of TVR and reinfarction, there are several challenges associated with PCI and stenting of acutely thrombotic lesions (i.e., STEMI lesions). Suboptimal myocardial perfusion has been noted post revascularization with both fibrinolytic therapy and primary PCI despite restoration of normal epicardial blood flow.22.23 Also, slow flow and no-reflow due to coronary microvascular obstruction (either in situ or through embolization of thrombotic plaque with associated spasm) has been recognized as an important drawback of stenting in heavily thrombotic lesions in approximately 10% of cases (Figure 1).24–26 Device-based studies to limit the amount of embolization—such as those using either aspiration thrombectomy or distal embolic protection—have not yielded positive outcomes.27–29 More recently, a conceptual strategy of delayed stenting following initial mechanical and pharmacologic reperfusion has been introduced to reduce no-reflow and improve myocardial salvage.30–33 The initial reperfusion strategy involves PTCA/thrombectomy alone in conjunction with intravenous antithrombotic agents, such as GpIIb/IIIa inhibitors and/or unfractionated or low-molecular-weight heparin, to passivate atherothrombotic plaque contents.

Figure 1.

Coronary no-reflow phenomenon. (A) Coronary capillary network after myocardial reperfusion, and (B) pathological comparison between reflow and no-reflow. Reprinted with permission.26

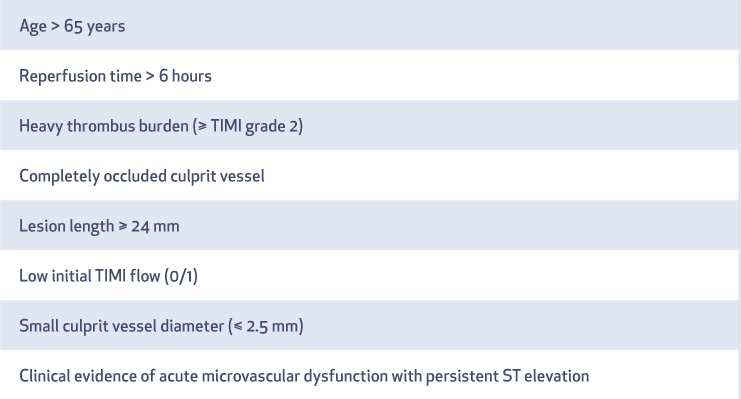

DEFER-STEMI, a prospective single-center trial of STEMI patients with one or more risk factors for no-reflow (Table 1), randomized 101 participants to either immediate conventional stenting or to angiography and deferred stenting within 4 to 16 hours following initial mechanical reperfusion.30 The median time to stenting in the deferred group was 9 hours. A lower incidence of slow/no-reflow and higher 6-month post-revascularization myocardial salvage (percentage of left ventricular mass) was noted in the deferred group compared with the immediate stenting group. Despite the promising results of this early proof-of-concept study, subsequent larger trials assessing clinical end points have demonstrated inconsistent results.34,35 DANAMI-3–DEFER, an open-label multicenter trial, randomized 1,215 patients to either immediate (n = 612) or deferred (n = 603) PCI with a median follow-up of 42 months; it found no significant difference between deferred and immediate stenting in all-cause mortality, hospital admission for heart failure, recurrent infarction, and target vessel revascularization.35 The Minimalist Immediate Mechanical Intervention (MIMI) approach study, a multicenter open-label trial of 160 STEMI patients randomized to immediate versus deferred stenting, reported no difference in the rate of major adverse cardiovascular and cerebral events among treatment arms.34 There were no significant differences in median ejection fraction, infarct weight, or infarct size in either group. Interestingly, median microvascular obstruction size (reported as a percentage of left ventricular mass) showed a trend towards benefit in immediate versus deferred stenting (1.88% vs 3.96%; P = .051), with significantly lower percent-microvascular-obstruction in the area at risk among the immediate stenting group (5.5% vs 12.3%; P = .049).

Table 1.

Risk factors for no-reflow phenomenon in the DEFER-STEMI Trial.30 TIMI: Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction score

Two recent meta-analyses examined the impact of deferred stenting on clinical outcomes.36,37 In one analysis, Qiao et al. reported no significant differences in MI, major bleeding, TVR, mortality, and MACE.37 However, significant improvement in long-term left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) was reported in the deferred stenting group compared with immediate stenting (mean difference 1.9%, 95% CI 0.77–3.03, P = .001). Additionally, a lower incidence of low/no-reflow was noted in the deferred group (OR 0.25, 95% CI 0.1–0.62, P = .002). This study was criticized on the basis of data heterogeneity and publication bias. Consequently, a second meta-analysis by Lee and colleagues examined data from 2,281 patients in 10 studies (3 randomized trials and 7 observational studies).36 Unsurprisingly, the incidence of MACE or its individual end points were no different between deferred and immediate stenting in STEMI. However, deferred stenting was again associated with a significantly lower risk of periprocedural composite events (acute occlusion, no/slow-reflow, or distal embolization compared to immediate stenting (5.3% vs 10.2, P = .002).

Taken together, the available data suggest that the overall benefit of deferred stenting in higher-risk STEMI PCI is likely limited to a lower incidence of no-flow phenomenon with a possible slight improvement in long-term LVEF. Although the clinical significance of these improvements in terms of long-term survival and MACE remains unclear, results from key long-term follow-up studies (DANAMI-3–DEFER and MIMI in particular) may provide additional insight about the use of deferred stenting in STEMI patients.

CULPRIT-ONLY VERSUS MULTIVESSEL PCI IN STEMI AND COMPLETE REVASCULARIZATION

Approximately 50% of patients presenting with STEMI have multivessel coronary disease (MVD) and poorer short- and longer-term outcomes than those with single-vessel disease despite adjustment for baseline characteristics.38,39 It is well known that preservation of ventricular function and cardiac output in the STEMI setting relies upon hyperfunctioning noninfarcted segments. If these segments are actively ischemic due to severe stenoses, the acute insult of the MI is more poorly tolerated.

Even after recovery from STEMI, the presence of residual ischemic burden may portend a worse prognosis. A growing body of literature suggests that large territories of residual ischemic myocardium are associated with poorer survival. Data from the CASS Registry identified placement of fewer than three bypass grafts in patients with three-vessel coronary disease (thereby implying residual ischemic territory) as a predictor of mortality.40 Similarly, in the COURAGE Nuclear substudy of patients with stable ischemic heart disease, Shaw and colleagues found an increasing rate of death or MI with increasing territories of ischemic myocardium, with a rate of almost 40% in patients with > 10% ischemic myocardium on myocardial perfusion scan at 18 months of follow-up.41 A study of 11,294 patients from the New York State Medical Registry indicated a hazard ratio for mortality of 1.23 (1.04–1.45, P = .01) at 18 months in patients with incomplete revascularization.42 Similar findings were observed in an analysis of drug-eluting stents versus coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) using data from the same registry, where hazard ratios of 1.66 and 2.59 were seen for incomplete revascularization in patients with MI or repeat revascularization regardless of revascularization strategy.43 The data favoring complete (vs incomplete) revascularization was summarized by Garcia et al. in a meta-analysis of 89,883 patients that demonstrated lower relative risks for long-term mortality (0.71, 95% CI, 0.65–0.77; P < .001), MI (0.78, 95% CI, 0.68–0.90; P = .001), and repeat coronary revascularization (0.74, 95% CI, 0.65–0.83; P < .001). Of note, the mortality benefit of complete revascularization was preserved regardless of revascularization modality (CABG: RR 0.70, 95% CI, 0.61–0.80; P < .001 and PCI: RR 0.72, 95% CI, 0.64–0.81; P < .001).44

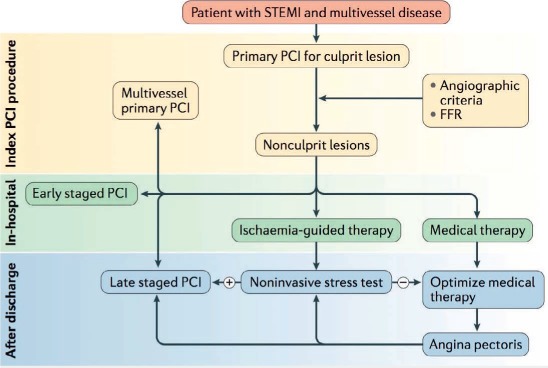

In view of the predicate data supporting complete revascularization, several groups have aimed to identify the optimal strategy of managing MVD in patients with STEMI (Figure 2).45 In their rationale, proponents of complete revascularization, which often requires multivessel PCI, cite the improved safety of such procedures as well as the likely benefits of minimizing the potential ischemic burden shouldered by an already perturbed post-STEMI myocardium. Conversely, those not in favor of complete revascularization using multivessel PCI (MV-PCI) cite high complication rates.46,47 Current guidelines are in favor of culprit-only PCI (CO-PCI) in all STEMI patients except those presenting with cardiogenic shock24,48; this is based on published data from several large nonrandomized observational studies that suggest no benefit of MV-PCI over CO-PCI and a possible increase of short- and long-term death and MACE.49–51 However, these guidelines do allow for staged revascularization of non-culprit arteries, particularly in the presence of ischemia on noninvasive testing.

Figure 2.

Schematic representation of treatment strategies for significant non-culprit coronary lesions following primary PCI for STEMI. Treatment strategies include medical therapy and/or partial or complete revascularization performed during index hospitalization or as a staged procedure. Reprinted with permission.45 PCI: percutaneous intervention; STEMI: ST-elevated myocardial infarction; FFR: fractional flow reserve

Four multicenter randomized controlled clinical trials have studied the optimal strategy for managing MVD in STEMI patients.52–55 The PRAMI trial enrolled 465 patients with acute STEMI and MVD.52 Following successful PCI of the culprit lesion, patients were randomized to undergo immediate multivessel PCI of all lesions with greater than 50% stenosis. The composite primary end point of death from cardiac causes, nonfatal MI, or refractory angina was significantly lower among patients randomized to MV-PCI (and thus complete revascularization), leading to premature termination of the trial. Notably, the number of primary end point events in this trial was very small, with an effect size that may have been overestimated in part by the trial's early termination. The CvLPRIT trial randomized 296 patients to culprit-only PCI versus MV-PCI prior to hospital discharge.53 In this study, ischemic testing was recommended prior to follow-up angiography and PCI if symptoms recurred on robust antianginal therapy. This study demonstrated a significant reduction in composite MACE (all-cause death, recurrent MI, heart failure, and any ischemia-driven revascularization) at 12 months in the MV-PCI group. The DANAMI-3–PRIMULTI trial enrolled 627 patients with STEMI and MVD in one or more noninfarct-related vessels. After undergoing successful PCI of the infarct-related artery, patients were randomized to either fractional flow reserve (FFR)-guided complete revascularization of all FFR-positive lesions or to ongoing medical therapy with no further PCI.54 A total of 69% of patients in the FFR-guided arm received additional PCI, whereas 31% did not require PCI based on FFR values. Although these authors found that MV-PCI resulted in a decrease in MACE rates from 22% to 13% (P = .004) in the group assigned to FFR-guided revascularization, the difference was largely driven by a reduction in repeat revascularization in the MV-PCI group. This study failed to show a difference in either death or MI with FFR-guided complete revascularization.

Most recently, the COMPARE-ACUTE trial randomized 886 patients to FFR-guided treatment of MVD following primary PCI for STEMI or FFR assessment of residual lesions with culprit-only PCI.55 Based on FFR assessment, 54.1% of patients in the MV-PCI group underwent FFR-guided multivessel intervention, 83.6% of whom were treated with multivessel primary PCI and the remainder treated with MV-PCI during the index hospitalization. The primary composite end point of death, MI, revascularization, and cerebrovascular events was 12.7% higher in the culprit-only PCI group (20.5% vs 7.8%; P < .001). Of note, this study did not consider a clinically indicated PCI in the CO-PCI group if it occurred within 45 days of the index intervention; this may have produced an underestimation of the difference between the two treatment strategies.

Interpreting the results of these large randomized trials in aggregate is somewhat challenging given important methodological differences (e.g., indications for repeat revascularization). Furthermore, the overall low event rates seen in several of the studies contribute to the fragility of the data, in which a change in a few events in either arm could appreciably alter conclusions. A clearer picture will no doubt start to emerge following results of the COMPLETE trial—a study of culprit-only versus complete revascularization in STEMI (with treatment of all coronary stenosis greater than 70% by angiography or greater than 50% with FFR < 0.80). This study will attempt to enroll 3,900 patients treated with contemporary DES and optimal medical therapy, including the use of newer, highly potent antiplatelet agents.56 At present, however, contemporary data suggest that MV-PCI to achieve complete revascularization is, at minimum, associated with a decreased need for repeat revascularization and may be a factor in decreasing mortality and subsequent MI in patients with STEMI and MVD.

ACCESS SITE CONSIDERATIONS TO OPTIMIZE OUTCOMES

In 2015, the European Society of Cardiology Clinical Practice Guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes presenting without persistent ST elevation recommended use of the radial artery approach for catheterization and intervention (Class 1A) if performed by skilled operators at experienced centers.57 Although the 2015 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association/Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions Focused Update on Primary Percutaneous Coronary Intervention in Patients with ST-Elevated Myocardial Infarction stopped short of recommending radial access for these procedures, it acknowledged the growing body of evidence supporting its use.58 Several recent randomized controlled trials (MATRIX, RIFLE-STAECS, RIVAL, STEMI RADIAL) have shown that the use of radial access in STEMI patients carries a reduction in major bleeding events, vascular or access site complications, hospital length of stay, and cardiac and all-cause mortality compared to femoral access use.59–62 Acquiring proficiency in radial access requires time and practice even for experienced PCI operators, although uptake of this technique is growing and resulting in more favorable outcomes.63

CONCLUSIONS

The treatment of STEMI has progressed dramatically over the past 30 years. Since the introduction of reperfusion therapies, primary PCI has become the preferred approach to coronary revascularization, and primary PCI with stent implantation produces improvements in MACE over PTCA alone. Recent studies have focused on the optimal timing of stent implantation and extent of reperfusion in STEMI patients with the goal of refining the approach to STEMI PCI. Ongoing work will develop the data on complete revascularization in STEMI by using a philosophy of ischemia-based revascularization.

KEY POINTS

Stenting in STEMI is superior to balloon angioplasty, primarily due to a reduction in repeat revascularization and reinfarction.

Deferred stenting in STEMI reduces the no-reflow phenomenon and may carry a slight benefit with respect to preservation of left ventricular ejection fraction, although the clinical significance of these benefits has yet to be determined.

Prevailing evidence suggests that complete revascularization in STEMI decreases the need for repeat revascularization and may improve survival. The COMPLETE trial will lend further insight in this area in the near future.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Disclosure: Dr. Kirtane conducts research (via institutional grants to Columbia University/CRF) on behalf of Medtronic, Abbott Vascular, Boston Scientific, Abiomed, Cath Works, Siemens, Philips, ReCor Medical, and Spectranetics. Dr. Kalra is a speakers' bureau member for Abiomed and ACIST Medical Systems.

REFERENCES

- 1. Effectiveness of intravenous thrombolytic treatment in acute myocardial infarction. Gruppo Italiano per lo Studio della Streptochinasi nell'Infarto Miocardico (GISSI). Lancet. 1986. February 22; 1 8478: 397– 402. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Randomised trial of intravenous streptokinase, oral aspirin, both, or neither among 17,187 cases of suspected acute myocardial infarction: ISIS-2. ISIS-2 (Second International Study of Infarct Survival) Collaborative Group. Lancet. 1988. August 13; 2 8607: 349– 60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. [GUSTO (Global Utilization of Streptokinase & t-PA for Occluded Coronary Arteries): comparison of four therapeutic strategies in acute myocardial infarction. Washington, 30 April 1993]. Internist (Berl). 1993. July; 34 7 Suppl: 1– 12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Randomised, double-blind comparison of reteplase double-bolus administration with streptokinase in acute myocardial infarction (INJECT): trial to investigate equivalence. International Joint Efficacy Comparison of Thrombolytics. Lancet. 1995. August 5; 346 8971: 329– 36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Van De Werf F, Adgey J, Ardissino D, . et al. Single-bolus tenecteplase compared with front-loaded alteplase in acute myocardial infarction: the ASSENT-2 double-blind randomised trial. Lancet. 1999. August 28; 354 9180: 716– 22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Cannon CP, Gibson CM, McCabe CH, . et al. TNK-tissue plasminogen activator compared with front-loaded alteplase in acute myocardial infarction: results of the TIMI 10B trial. Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) 10B Investigators. Circulation. 1998. December 22–29; 98 25: 2805– 14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. O'Neill W, Timmis GC, Bourdillon PD, . et al. A prospective randomized clinical trial of intracoronary streptokinase versus coronary angioplasty for acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 1986. March 27; 314 13: 812– 8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Keeley EC, Boura JA, Grines CL, . et al. Primary angioplasty versus intravenous thrombolytic therapy for acute myocardial infarction: a quantitative review of 23 randomised trials. Lancet. 2003. January 4; 361 9351: 13– 20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Antman EM, Anbe DT, Armstrong PW, . et al. ACC/AHA guidelines for the management of patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Committee to Revise the 1999 Guidelines for the Management of Patients with Acute Myocardial Infarction). Circulation. 2004. August 31; 110 9: e82– 292. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Weaver WD, Simes RJ, Betriu A, . et al. Comparison of primary coronary angioplasty and intravenous thrombolytic therapy for acute myocardial infarction: a quantitative review. JAMA. 1997. December 17; 278 23: 2093– 8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Stone GW, Grines CL, Browne KF, . et al. Implications of recurrent ischemia after reperfusion therapy in acute myocardial infarction: a comparison of thrombolytic therapy and primary angioplasty. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1995. July; 26 1: 66– 72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Stone GW, Grines CL, Rothbaum D, . et al. Analysis of the relative costs and effectiveness of primary angioplasty versus tissue-type plasminogen activator: the Primary Angioplasty in Myocardial Infarction (PAMI) trial. The PAMI Trial Investigators. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1997. April; 29 5: 901– 7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Fischman DL, Leon MB, Baim DS, . et al. A randomized comparison of coronary-stent placement and balloon angioplasty in the treatment of coronary artery disease. Stent Restenosis Study Investigators. N Engl J Med. 1994. August 25; 331 8: 496– 501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Serruys PW, de Jaegere P, Kiemeneij F, . et al. A comparison of balloon-expandable-stent implantation with balloon angioplasty in patients with coronary artery disease. Benestent Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1994. August 25; 331 8: 489– 95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Grines CL, Cox DA, Stone GW, . et al. Coronary angioplasty with or without stent implantation for acute myocardial infarction. Stent Primary Angioplasty in Myocardial Infarction Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1999. December 23; 341 26: 1949– 56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Stone GW, Grines CL, Cox DA, . et al. Comparison of angioplasty with stenting, with or without abciximab, in acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2002. March 28; 346 13: 957– 66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Zhu MM, Feit A, Chadow H, Alam M, Kwan T, Clark LT.. Primary stent implantation compared with primary balloon angioplasty for acute myocardial infarction: a meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Am J Cardiol. 2001. August 1; 88 3: 297– 301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Nordmann AJ, Bucher H, Hengstler P, Harr T, Young J.. Primary stenting versus primary balloon angioplasty for treating acute myocardial infarction. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005. April 18; 2: CD005313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bangalore S, Kumar S, Fusaro M, . et al. Short- and long-term outcomes with drug-eluting and bare-metal coronary stents: a mixed-treatment comparison analysis of 117 762 patient-years of follow-up from randomized trials. Circulation. 2012. June 12; 125 23: 2873– 91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Stone GW, Parise H, Witzenbichler B, . et al. Selection criteria for drug-eluting versus bare-metal stents and the impact of routine angiographic follow-up: 2-year insights from the HORIZONS-AMI (Harmonizing Outcomes With Revascularization and Stents in Acute Myocardial Infarction) trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010. November 2; 56 19: 1597– 604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Palmerini T, Biondi-Zoccai G, Della Riva D, . et al. Clinical outcomes with drug-eluting and bare-metal stents in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: evidence from a comprehensive network meta-analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013. August 6; 62 6: 496– 504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Gibson CM, Cannon CP, Daley WL, . et al. TIMI frame count: a quantitative method of assessing coronary artery flow. Circulation. 1996. March 1; 93 5: 879– 88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Gibson CM, Cannon CP, Murphy SA, . et al. Relationship of TIMI myocardial perfusion grade to mortality after administration of thrombolytic drugs. Circulation. 2000. January 18; 101 2: 125– 30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. O'Gara PT, Kushner FG, Ascheim DD, . et al. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of ST-elevation myocardial infarction: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2013. January 29; 127 4: 529– 55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Rezkalla SH, Stankowski RV, Hanna J, Kloner RA.. Management of No-Reflow Phenomenon in the Catheterization Laboratory. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2017. February 13; 10 3: 215– 223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. O'Farrell FM, Attwell. . A role for pericytes in coronary no-reflow. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2014. June; 11 7: 427– 32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Fröbert O, Lagerqvist B, Olivecrona GK, . et al. Thrombus aspiration during ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2013. October 24; 369 17: 1587– 97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Jolly SS, Cairns JA, Yusuf S, . et al. Randomized trial of primary PCI with or without routine manual thrombectomy. N Engl J Med. 2015. April 9; 372 15: 1389– 98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Stone GW, Webb J, Cox DA, . et al. Distal microcirculatory protection during percutaneous coronary intervention in acute ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2005. March 2; 293 9: 1063– 72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Carrick D, Oldroyd KG, McEntegart M, . et al. A randomized trial of deferred stenting versus immediate stenting to prevent no- or slow-reflow in acute ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (DEFER-STEMI). J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014. May 27; 63 20: 2088– 98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Isaaz K, Robin C, Cerisier A, . et al. A new approach of primary angioplasty for ST-elevation acute myocardial infarction based on minimalist immediate mechanical intervention. Coron Artery Dis. 2006. May; 17 3: 261– 9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Ke D, Zhong W, Fan L, Chen L.. Delayed versus immediate stenting for the treatment of ST-elevation acute myocardial infarction with a high thrombus burden. Coron Artery Dis. 2012. November; 23 7: 497– 506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Meneveau N, Séronde MF, Descotes-Genon V, . et al. Immediate versus delayed angioplasty in infarct-related arteries with TIMI III flow and ST segment recovery: a matched comparison in acute myocardial infarction patients. Clin Res Cardiol. 2009. April; 98 4: 257– 64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Belle L, Motreff P, Mangin L, . et al. Comparison of Immediate With Delayed Stenting Using the Minimalist Immediate Mechanical Intervention Approach in Acute ST-Segment-Elevation Myocardial Infarction: The MIMI Study. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2016. March; 9 3: e003388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kelbæk H, Høfsten DE, Køber L, . et al. Deferred versus conventional stent implantation in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (DANAMI 3-DEFER): an open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2016. May 28; 387 10034: 2199– 206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Lee JM, Rhee TM, Chang H, . et al. Deferred versus conventional stent implantation in patients with acute ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: An updated meta-analysis of 10 studies. Int J Cardiol. 2017. March 1; 230: 509– 517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Qiao J, Pan L, Zhang B, . et al. Deferred Versus Immediate Stenting in Patients With ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Am Heart Assoc. 2017. March 8; 6 3 pii: e004838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Sorajja P, Gersh BJ, Cox DA, . et al. Impact of multivessel disease on reperfusion success and clinical outcomes in patients undergoing primary percutaneous coronary intervention for acute myocardial infarction. Eur Heart J. 2007. July; 28 14: 1709– 16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Park DW, Clare RM, Schulte PJ, . et al. Extent, location, and clinical significance of non-infarct-related coronary artery disease among patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction. JAMA. 2014. November 19; 312 19: 2019– 27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Bell MR, Gersh BJ, Schaff HV, . et al. Effect of completeness of revascularization on long-term outcome of patients with three-vessel disease undergoing coronary artery bypass surgery. A report from the Coronary Artery Surgery Study (CASS) Registry. Circulation. 1992. August; 86 2: 446– 57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Shaw LJ, Berman DS, Maron DJ, . et al. Optimal medical therapy with or without percutaneous coronary intervention to reduce ischemic burden: results from the Clinical Outcomes Utilizing Revascularization and Aggressive Drug Evaluation (COURAGE) trial nuclear substudy. Circulation. 2008. March 11; 117 10: 1283– 91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Hannan EL, Wu C, Walford G, . et al. Incomplete revascularization in the era of drug-eluting stents: impact on adverse outcomes. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2009. January; 2 1: 17– 25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Bangalore S, Guo Y, Samadashvili Z, Blecker S, Xu J, Hannan EL.. Everolimus-eluting stents or bypass surgery for multivessel coronary disease. N Engl J Med. 2015. March 26; 372 13: 1213– 22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Garcia Ss, Sandoval Y, Roukoz H, . et al. Outcomes after complete versus incomplete revascularization of patients with multivessel coronary artery disease: a meta-analysis of 89,883 patients enrolled in randomized clinical trials and observational studies. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013. October 15; 62 16: 1421– 31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Vogel B, Mehta SR, Mehran R.. Reperfusion strategies in acute myocardial infarction and multivessel disease. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2017. November; 14 11: 665– 678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Jaski BE, Cohen JD, Trausch J, . et al. Outcome of urgent percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty in acute myocardial infarction: comparison of single-vessel versus multivessel coronary artery disease. Am Heart J. 1992. December; 124 6: 1427– 33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Nath A, DiSciascio G, Kelly KM, . et al. Multivessel coronary angioplasty early after acute myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1990. September; 16 3: 545– 50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Windecker S, Kolh P, Alfonso F, . et al. [2014 ESC/EACTS Guidelines on myocardial revascularization]. Kardiol Pol. 2014; 72 12: 1253– 379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Cavender MA, Milford-Beland S, Roe MT, Peterson ED, Weintraub WS, Rao SV.. Prevalence, predictors, and in-hospital outcomes of non-infarct artery intervention during primary percutaneous coronary intervention for ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (from the National Cardiovascular Data Registry). Am J Cardiol. 2009. August 15; 104 4: 507– 13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Roe MT, Cura FA, Joski PS, . et al. Initial experience with multivessel percutaneous coronary intervention during mechanical reperfusion for acute myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol. 2001. July 15; 88 2: 170– 3, A6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Santos AR, Piçarra BC, Celeiro M, . et al. Multivessel approach in ST-elevation myocardial infarction: impact on in-hospital morbidity and mortality. Rev Port Cardiol. 2014. February; 33 2: 67– 73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Wald DS, Morris JK, Wald NJ, . et al. Randomized trial of preventive angioplasty in myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2013. September 19; 369 12: 1115– 23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Gershlick AH, Khan JN, Kelly DJ, . et al. Randomized trial of complete versus lesion-only revascularization in patients undergoing primary percutaneous coronary intervention for STEMI and multivessel disease: the CvLPRIT trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015. March 17; 65 10: 963– 72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Engstrøm T, Kelbæk H, Helqvist S, . et al. Complete revascularisation versus treatment of the culprit lesion only in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction and multivessel disease (DANAMI-3—PRIMULTI): an open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2015. August 15; 386 9994: 665– 71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Smits PC, Abdel-Wahab M, Neumann FJ, . et al. Fractional Flow Reserve-Guided Multivessel Angioplasty in Myocardial Infarction. N Engl J Med. 2017. March 30; 376 13: 1234– 1244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Mehta SR. Complete vs Culprit-only Revascularization to Treat Multi-vessel Disease After Primary PCI for STEMI (COMPLETE). ClinicalTrials.gov 2015 [cited 2017 September 15, 2017]; Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01740479.

- 57. Roffi M, Patrono C, Collet JP, . et al. 2015 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes in patients presenting without persistent ST-segment elevation: Task Force for the Management of Acute Coronary Syndromes in Patients Presenting without Persistent ST-Segment Elevation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J. 2016. January 14; 37 3: 267– 315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Levine GN, Bates ER, Blankenship JC, . et al. 2015 ACC/AHA/SCAI Focused Update on Primary Percutaneous Coronary Intervention for Patients With ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction: An Update of the 2011 ACCF/AHA/SCAI Guideline for Percutaneous Coronary Intervention and the 2013 ACCF/AHA Guideline for the Management of ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions. Circulation. 2016. March 15; 133 11: 1135– 47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Bernat I, Horak D, Stasek J, . et al. ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction treated by radial or femoral approach in a multicenter randomized clinical trial: the STEMI-RADIAL trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014. March 18; 63 10: 964– 72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Jolly SS, Yusuf S, Cairns J, . et al. Radial versus femoral access for coronary angiography and intervention in patients with acute coronary syndromes (RIVAL): a randomised, parallel group, multicentre trial. Lancet. 2011. April 23; 377 9775: 1409– 20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Romagnoli E, Biondi-Zoccai G, Sciahbasi A, . et al. Radial versus femoral randomized investigation in ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome: the RIFLE-STEACS (Radial Versus Femoral Randomized Investigation in ST-Elevation Acute Coronary Syndrome) study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012. December 18; 60 24: 2481– 9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Valgimigli M, Gagnor A, Calabró P, . et al .; MATRIX Investigators Radial versus femoral access in patients with acute coronary syndromes undergoing invasive management: a randomised multicentre trial. Lancet. 2015. June 20; 385 9986: 2465– 76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Mamas MA, Nolan J, de Belder MA, . et al .; British Cardiovascular Intervention Society (BCIS) and the National Institute for Clinical Outcomes Research (NICOR) Changes in Arterial Access Site and Association With Mortality in the United Kingdom: Observations From a National Percutaneous Coronary Intervention Database. Circulation. 2016. April 26; 133 17: 1655– 67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]