Abstract

Aims

Although clinical guidelines advocate the use of the highest tolerated dose of angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers after acute myocardial infarction (MI), the optimal dosing or the risk–benefit profile of different doses have not been fully identified.

Methods and results

In this multicentre trial, 495 Korean patients with acute ST segment elevation MI and subnormal left ventricular (LV) ejection fraction (<50%) were randomly allocated (2:1) to receive maximal tolerated dose of valsartan (titrated up to 320 mg/day, n = 333) or low‐dose valsartan (80 mg/day, n = 162) treatment. The primary objective was to assess the changes in echocardiographic parameters of LV remodelling from baseline to 12 months after discharge. After treatment, end‐diastolic LV volume (LVEDV) decreased significantly in the low‐dose group, but the difference in LVEDV changes was insignificant between the maximal‐tolerated‐dose and low‐dose groups. End‐systolic LV volume decreased significantly in both groups, to a similar degree between groups. LV ejection fraction rose significantly in both study groups, to a similar degree. Changes in plasma levels of neurohormones were also comparable between the two groups. Drug‐related adverse effects occurred more frequently in the maximal‐tolerated‐dose group than in the low‐dose group (7.96 vs. 0.69%, P < 0.001).

Conclusions

In the present study, treatment with the maximal tolerated dose of valsartan did not exhibit a superior effect on post‐MI LV remodelling compared with low‐dose treatment and was associated with a greater frequency of adverse effect in Korean patients. Further study with a sufficient number of cases and statistical power is warranted to verify the findings of the present study.

Keywords: Myocardial infarction, Ventricular remodelling, Valsartan, Dose

Introduction

Suppression of angiotensin activity either with angiotensin‐converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors or with angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) attenuates ventricular dilatation and improves clinical outcomes after acute myocardial infarction (MI).1, 2, 3, 4, 5 Current guidelines recommend administration of ACE inhibitors or ARBs in patients with acute MI6, 7 and advocate the use of the maximal tolerable dose of those drugs, as used in major trials that established the efficacy of the drugs.6 However, those trials assessed the efficacy of a single target dose of the study drugs; they did not provide the optimal dosing or risk–benefit assessment of different doses of such agents. While higher neurohormone levels have been associated with worse prognosis in patients with left ventricular (LV) dysfunction,8 it remains undetermined whether the highest possible degree of neurohumoral blockade is more beneficial. Intensified therapy with a combination of an ACE inhibitor and ARB did not improve clinical outcomes compared with monotherapy in post‐MI patients.5

The issue of the optimal dosing of ACE inhibitors or ARBs has been debated over the past years in the field of systolic heart failure. Small studies that compared the efficacy of therapy with higher‐dose vs. lower‐dose agents have yielded inconsistent or conflicting results.9, 10, 11 Recently, a large‐scale trial, the Heart Failure Evaluation of Angiotensin Antagonist Losartan, demonstrated the superiority of higher‐dose over low‐dose losartan on the primary outcomes of death or hospitalization in patients with systolic heart failure.12 However, the study subjects were limited to patients who were intolerant to ACE inhibitors, precluding extrapolation of the results to the general population. Furthermore, the pathophysiology of post‐MI remodelling may differ from that of disease progression in chronic systolic heart failure. Thus, the question of whether the highest dose of an angiotensin antagonist offers a greater benefit in the post‐MI setting than does a submaximal dose, which is lower than that used in major trials but is widely prescribed in practice, remains to be solved. This might be a more relevant issue in the Asian population, as Asians have different genetic traits and body sizes than do those of Western backgrounds. Therefore, this study (Valsartan in Post‐MI Remodelling [VALID]) was conducted to determine whether the recommended maximal tolerated dose of valsartan (320 mg/day or the maximum tolerated daily dose) is more efficacious than is the low dose (80 mg/day) in retarding post‐MI LV remodelling in Korean patients who suffered their first ST‐segment elevation MI (STEMI).

Methods

Study design

The design of this study was previously described.13 VALID is a randomized, single‐blinded, multicentre trial conducted in 17 regional hospitals in Korea. Men and women 18 years of age or older who had suffered their first acute STEMI within the previous 10 days were eligible for enrolment. At the time of randomization, patients were required to have signs of LV dysfunction, which was defined as LV ejection fraction (LVEF) <50% by visual estimation on two‐dimensional echocardiography. Patients were enrolled regardless of whether or not they received reperfusion therapy, either by thrombolysis or by primary percutaneous coronary intervention. Patients were excluded if they had a known intolerance to the study drug, systolic blood pressure (BP) <90 mmHg, significant valvular heart disease or arrhythmia, hepatic or renal dysfunction severer than a mild degree, or systemic illness with a limited life expectancy.13 The first patient was enrolled on 7 January 2008, and patients were enrolled until 31 December 2012.

The study conformed to the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the institutional review board of the participating site. All patients provided written informed consent before randomization.

Randomization and intervention

Eligible patients were randomly assigned in a 2:1 fashion to either maximal‐tolerated‐dose valsartan (titrated up to 320 mg/day as tolerated) or low‐dose valsartan (80 mg/day) treatment. Study drug administration was conducted following titration scheme as described in a previous paper.13 In the low‐dose group, valsartan at 40 mg twice a day was administered throughout the study period of 1 year. For those in the maximal‐tolerated‐dose group, the dose was up‐titrated to 80 mg twice a day before hospital discharge and finally to 160 mg twice a day after 2 weeks of outpatient visits. If up‐titration was not feasible, because of either hypotension or deepening azotemia, the previous dose was subsequently administered as the maximal tolerated dose. Pharmacological therapy with agents other than the study drug, including beta‐adrenergic blockers, or the choice of additional antihypertensive drugs was permitted at the discretion of the attending physician. However, an increase in the dose of study drug for BP control was prohibited. No one in the low‐dose group crossed over to the high‐dose group within the study period.

Follow‐up and study objectives

After discharge, patient visits were scheduled in Week 2 (high‐dose group only) and Months 1, 3, 6, 9, and 12. At each visit, patients underwent a complete physical examination, medical history taking, and assessment of drug compliance. Physical functional status, pre‐defined clinical events, and occurrence of adverse effects were all recorded at each visit. Echocardiographic examination and serum neurohormonal assays were conducted at 3 and 12 months after discharge.

The primary objective of the study was to assess changes in echocardiographic indices of LV remodelling from baseline to 12 months after discharge. Echocardiographic records from the participating sites were analysed in a central laboratory by an independent observer uninformed of patient assignment. LV volume at end‐diastolic and end‐systolic time (LVEDV and LVESV, respectively) and LVEF were measured by the modified Simpson rule.14 The secondary objectives of the study included assessing changes in plasma neurohormone levels and the occurrence of clinical events. Plasma neurohormone assays for B‐type natriuretic peptide (BNP) and norepinephrine were conducted in a central laboratory. Occurrences of major clinical events including all‐cause death, cardiovascular death, hospitalization, and revascularization were collected from the participating site. In addition, adverse effects during the treatment period were also registered in order to evaluate the safety profile.

Statistical analyses

Owing to a lack of relevant data in the Asian population, a sample size calculation was performed based on the data from the Valsartan in Acute Myocardial Infarction Trial (VALIANT); the analysis showed that 600 patients were necessary to detect, with 90% power, a 7.6 mL difference in LVEDV between the treatment groups.5 Because the present study enrolled patients with milder LV dysfunction, 279 patients in the low‐dose group and 558 patients in the maximal‐tolerated‐dose valsartan group were required to detect smaller differences in end‐diastolic volume (3.8 mL, two‐sided level of significance α = 5%, and power of 1 − β = 90%) between treatment groups.

The principal analysis was performed on an intention‐to‐treatment basis. Continuous variables were assessed using Student's t test, and discrete variables were compared using the χ2 test. Echocardiographic data and biomarkers were assessed using the Student t test, if the samples are normally distributed or their variances are homogeneous or Mann–Whitney U-test, otherwise. A two‐way ANOVA for repeated measures was used to detect changes in echocardiographic values from randomization to end of treatment in the two study groups. A value of P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS Version 9.0 (SAS Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Study patients

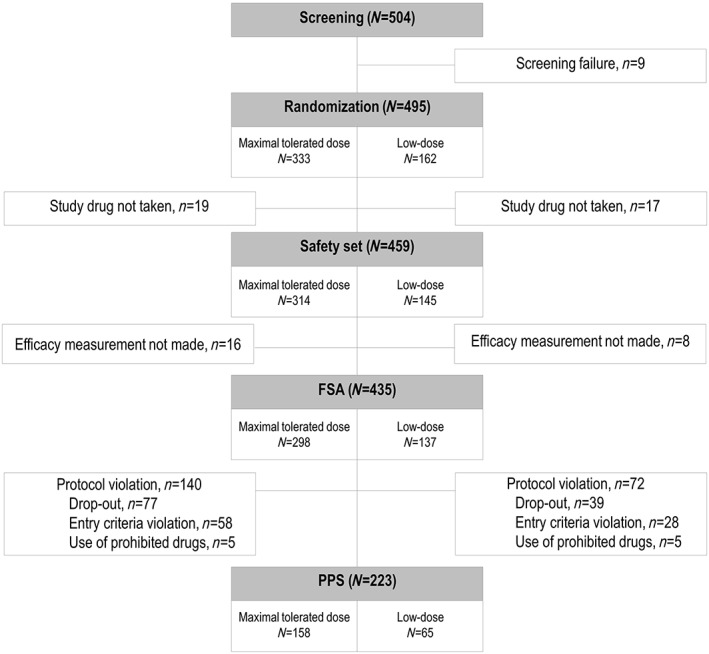

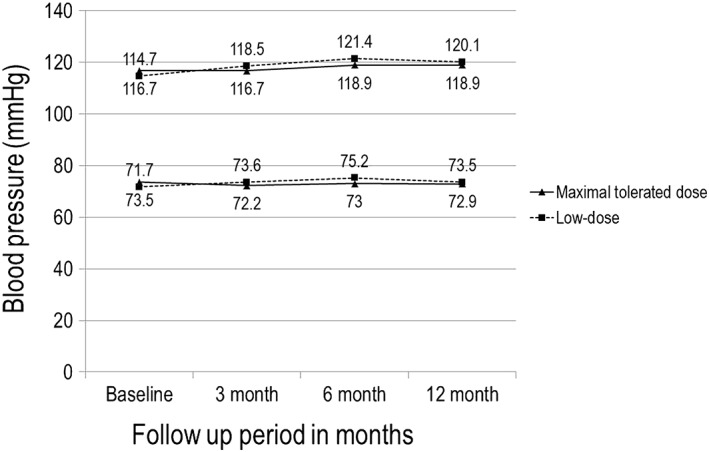

Owing to a low rate of patient recruitment despite the extended study period, enrolment was halted at the end of December 2012. Thus, 495 patients were included in the study and randomized into the two groups. Figure 1 shows the trial profile. Safety set analysis was performed for those who took the study medication. Full set analysis was carried out in 435 subjects for whom efficacy measurements were taken. At baseline, the two treatment groups were equally distributed in terms of demographic features, medical history, electrographic and angiographic findings, and medications taken concomitantly (Table 1). Out of 495 patients, the hypertension distribution of the study population showed 45.6% male and 33.1% female patients. These populations had been treated with antihypertensive drug in primary care. Overall, 66.1% patients were treated with a single antihypertensive drug, and 33.9% were treated with antihypertensive drug combinations. During the study period, 37 patients (7.5%) received mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist. A total 46 of 495 patients (9.3%) had New York Association Class III or Class IV congestive heart failure, and 11 of 495 patients (2.3%) had an LVEF of 35% or less. Follow‐up medication use was similar in the two groups at both 6 months and 1 year. The mean dose of valsartan was 196.2 ± 97.8 mg/day in the maximal‐tolerated‐dose group and 80.0 ± 0.0 mg/day in the low‐dose group. In the maximal‐tolerated‐dose group, 32% of the patients took the maximum dose (320 mg/day) of valsartan. BP profiles at baseline and after 12 months of treatment were similar in both study groups, and changes in BP during the period were not significantly different between the two groups (systolic/diastolic BP at baseline and 12 months: 116.7 ± 16.4/73.5 ± 11.7 and 118.9 ± 14.6/72.9 ± 10.4 mmHg, respectively, in the maximal‐tolerated‐dose group and 114.7 ± 17.2 and 120.1 ± 14.2 mmHg in the low‐dose group; change in systolic BP during the study period: 2.9 ± 19.2 mmHg in the maximal‐tolerated‐dose group and 3.9 ± 19.4 mmHg in the low‐dose group, P = 0.67; change in diastolic BP: −0.1 ± 14.3 mmHg in the maximal‐tolerated‐dose group and 0.9 ± 13.2 mmHg in the low‐dose group, P = 0.55) (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Flow chart of participants in the randomized controlled trial. Five hundred four patients were enrolled at 17 centres and assessed for eligibility. Of those enrolled, nine were excluded from randomization for screening failure. Four hundred ninety‐five patients were randomized, of which 333 were allocated to the maximal‐tolerated‐dose group and 162 patients were allocated to the low‐dose group.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of study subjects

| Maximal‐tolerated‐dose group (n = 333) | Low‐dose group (n = 162) | P‐value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 59.5±11.5 | 58.4±11.2 | 0.297a |

| Male sex, n (%) | 72(21.6) | 42(25.9) | 0.286b |

| Height, cm | 165.3±7.6 | 164.69±11.2 | 0.542c |

| Weight, cm | 65.5±10.7 | 64.9±11.1 | 0.551c |

| Body surface area, m2 | 1.9±0.2 | 1.92±0.2 | 0.589a |

| Hypertension | 122(37.1) | 58(36.9) | 0.976b |

| Diabetes | 76(23.1) | 36(22.9) | 0.967b |

| Dyslipidaemia | 29(8.8) | 9(5.7) | 0.230b |

| Stroke | 20(6.1) | 13(8.3) | 0.367b |

| Smoking | |||

| Never smoked | 140(42.9) | 57(36.5) | 0.210b |

| Current smoker | 154(47.2) | 87(55.8) | |

| Past smoker | 32(9.8) | 12(7.7) | |

| Killip classification | |||

| Class I | 192(59.8) | 90(59.2) | 0.566d |

| Class II | 97(30.2) | 48(31.6) | |

| Class III | 27(8.4) | 14(9.2) | |

| Class IV | 5(1.5) | 0(0.0) | |

| Infarct size (CK‐MB), U/L | 145.40±191.13 | 128.96±196.22 | 0.039c |

| Infarct site, anterior | 249(75.6) | 125(77.6) | 0.632b |

| Infarct‐related artery | |||

| Left main | 0(0.0) | 1(1.1) | 0.517d |

| LAD | 130(69.9) | 67(71.3) | |

| LCX | 14(7.5) | 8(8.5) | |

| RCA | 42(22.6) | 18(19.2) | |

| TIMI flow of infarct‐related artery | |||

| 0 | 103(55.7) | 45(47.8) | 0.671b |

| 1 | 36(19.4) | 21(22.3) | |

| 2 | 17(9.2) | 10(10.6) | |

| 3 | 29(15.7) | 18(19.2) | |

| Thrombolytic therapy | 25(7.5) | 7(4.3) | 0.176b |

| Percutaneous coronary intervention | |||

| Primary | 267(86.4) | 123(83.1) | 0.530b |

| Rescue | 36(11.6) | 20(13.5) | |

| Delayed | 6(1.9) | 5(3.4) | |

| Coronary artery bypass graft | 1(0.3) | 3(1.8) | 0.105d |

| Concomitant drugs | |||

| Aspirin | 330(99.1) | 161(99.4) | 0.421b |

| Thienopyridine | 328(98.5) | 158(97.5) | 0.618b |

| Beta‐blockers | 316(94.9) | 152(93.8) | 0.616b |

| ACE inhibitors | 40(13.4) | 11(8.0) | 0.104b |

| Statins | 181(60.7) | 86(62.8) | 0.685b |

| Aldosterone antagonist | 28(9.4) | 9(6.6) | 0.326b |

| Digoxin | 8(2.7) | 3(2.2) | 1.000d |

| Diuretics | 96(32.2) | 36(26.3) | 0.211b |

| Loop diuretics | 73(24.5) | 27(19.7) | 0.270b |

| Thiazide diuretics | 13(4.4) | 4(2.9) | 0.471b |

ACE, angiotensin‐converting enzyme; LAD, left anterior descending artery; LCX, left circumflex artery; RCA, right coronary artery. Values are absolute and relative frequencies for categorical variables and mean ± standard deviation for continuous variables. Values are n, N/n (%), mean ± SD.

Wilcoxon rank sum test.

χ2 test.

Two‐sample t‐test.

Fisher's exact test.

Figure 2.

Systolic and diastolic blood pressure in the two treatment groups over the course of the trial.

Study objectives

Changes in echocardiographic indices of left ventricular remodelling

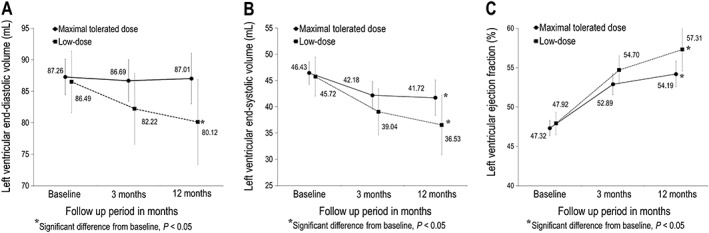

The changes in LV volume and LVEF from baseline to 3 and 12 months are shown in Figure 3. Echocardiogram results were available for 206 (64.0%) patients in the maximal‐tolerated‐dose group and 95 (58.6%) patients in the low‐dose group. Baseline echocardiographic parameters, including LVEDV, LVESV, and LVEF, were not significantly different between the two treatment groups (Table 2). Compared with that at baseline, LVEDV changed by 0.42 ± 20.01 mL (P = 0.79) in the maximal‐tolerated‐dose group and decreased by 3.8 ± 15.54 mL (P = 0.01) in the low‐dose group. However, the magnitude of LVEDV change was not significantly different between the two groups (P = 0.08). A separate analysis for the subgroup of 35 patients with LVEF <40% also revealed a comparable change of LVEDV in the maximal‐tolerated‐dose and low‐dose groups (1.79 ± 31.91 vs. −2.67 ± 26.23 mL, respectively, P = 0.48). LVESV decreased significantly from baseline in both study groups (−3.84 ± 17.01 and −6.78 ± 14.01 mL, respectively, both P < 0.001), but the magnitude of change was comparable between the two groups (P = 0.12). LVEF rose significantly from baseline in both groups (6.07 ± 8.34% and 8.45 ± 9.18%, respectively, both P < 0.001), to a similar degree between the two groups (P = 0.08). Because of lack of study numbers, post hoc power analysis was performed for echocardiographic parameters according to real number of cases. The values of statistical power for LVEVD, LVESD, and LVEF changes were 0.60, 0.43, and 0.75, respectively, with a two‐sided α error probability of 0.05 and an effect size of 0.5.

Figure 3.

Effect of valsartan on left ventricular echocardiographic measurements. Changes in left ventricular end‐diastolic volume (A), end‐systolic volume (B), and ejection fraction (C) from baseline to 12 months after randomization in both groups.

Table 2.

Baseline echocardiographic and neurohormonal characteristics

| Maximal tolerated dose group | Low‐dose group | P‐value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Mean±SD | n | Mean±SD | ||

| Echocardiography | |||||

| LVEDV, mL | 206 | 87.3±20.6 | 95 | 86.5±24.2 | 0.776 |

| LVESV, mL | 206 | 46.4±15.7 | 95 | 45.7±18.3 | 0.730 |

| LVEF, % | 206 | 47.3±7.2 | 95 | 47.9±7.1 | 0.499 |

| Neurohormone | |||||

| BNP, pg/dL | 275 | 252.8±292.3 | 119 | 239.4±302.2 | 0.678 |

| Norepinephrine, mg/dL | 277 | 403.1±287.4 | 121 | 382.8±255.1 | 0.504 |

BNP, B‐type natriuretic peptide; LVEDV, left ventricular end‐diastolic volume; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; LVESV, left ventricular end‐systolic volume; SD, standard deviation. Values are absolute frequencies for categorical variables and mean ± SD for continuous variables.

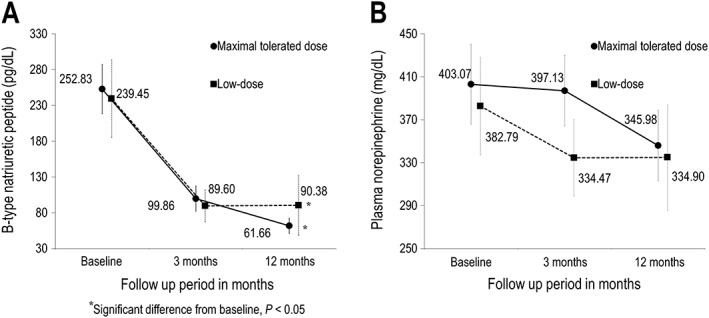

Change in plasma neurohormone levels

Changes in plasma neurohormone levels during the study period are depicted in Figure 4. Baseline neurohormone levels were not significantly different between the two treatment groups (Table 2). The level of BNP decreased significantly from baseline in both the maximal‐tolerated‐dose and low‐dose groups (−154.65 ± 169.43 and −139.59 ± 272.11 pg/dL, respectively, both P < 0.01). The magnitude of BNP change was not significantly different between the two groups (P = 0.33). The plasma norepinephrine level decreased in both groups, but the end levels were not statistically significantly different from baseline (−17.38 ± 298.05 mg/dL, P = 0.49, and −20.02 ± 245.75 mg/dL, P = 0.21, respectively). The magnitude of change was comparable in the two groups (P = 0.46).

Figure 4.

Effect of valsartan on plasma neurohormones. Changes in plasma B‐type natriuretic peptide (A) and norepinephrine (B) from baseline to 12 months after randomization.

Clinical events and adverse effects

During the 12 month study period, only a small number of major events were observed, and there was no significant difference in the event rate between the maximal‐tolerated‐dose and low‐dose valsartan treatment groups (Table 3). Adverse events occurred in 69/314 patients (21.9%) in the maximal‐tolerated‐dose group and in 30/145 patients (20.1%) in the low‐dose group (P = 0.76). The number of events in the maximal‐tolerated‐dose and low‐dose groups was 139 and 61, respectively. Among the adverse events, drug‐related adverse reactions occurred more frequently in the maximal‐tolerated‐dose group (25/314, 7.96%) than in the low‐dose group (1/145, 0.69%) (P < 0.001). The most frequent adverse drug reaction was hypotension and hypotension‐related symptoms (Table 4). When adverse events specifically related to low BP (dizziness, hypotension, and syncope) were examined, they were not found in the low‐dose group. Deepening azotemia also was not reported in the low‐dose group. There were no significant changes in the New York Heart Association class between the low‐dose and maximal‐tolerated‐dose groups. No patient worsened to Class IV in either treatment group.

Table 3.

Major clinical events during follow‐up

| Maximal‐tolerated‐dose group (n = 333) | Low‐dose group (n = 162) | P‐value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Death | 3 (0.90) | 3(1.85) | 0.3317 |

| Cardiovascular death | 1 (0.30) | 2 (1.23) | 0.1929 |

| Hospitalization | 52 (15.62) | 22(13.58) | 0.9151 |

| Recanalization | 10 (3.00) | 7 (4.32) | 0.3590 |

Table 4.

Incidence of drug‐related adverse events associated with valsartan

| System organ class/preferred term | Maximal‐tolerated‐dose group (n = 314) | Low‐dose group (n = 145) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | (%) | [Cases] | n | (%) | [Cases] | |

| Nervous system disorders | 13 | (4.14) | [13] | 0 | (0.00) | [0] |

| Dizziness | 11 | (3.50) | [11] | 0 | (0.00) | [0] |

| Dizziness postural | 2 | (0.64) | [2] | 0 | (0.00) | [0] |

| Vascular disorders | 7 | (2.23) | [7] | 0 | (0.00) | [0] |

| Hypotension | 5 | (1.59) | [5] | 0 | (0.00) | [0] |

| Orthostatic hypotension | 2 | (0.64) | [2] | 0 | (0.00) | [0] |

| Gastrointestinal disorders | 2 | (0.64) | [2] | 0 | (0.00) | [0] |

| Abdominal pain upper | 1 | (0.32) | [1] | 0 | (0.00) | [0] |

| Diarrhoea | 1 | (0.32) | [1] | 0 | (0.00) | [0] |

| General disorders and administration site conditions | 2 | (0.64) | [2] | 0 | (0.00) | [0] |

| Asthenia | 1 | (0.32) | [1] | 0 | (0.00) | [0] |

| Chest discomfort | 1 | (0.32) | [1] | 0 | (0.00) | [0] |

| Investigations | 2 | (0.64) | [2] | 0 | (0.00) | [0] |

| Blood creatinine increased | 1 | (0.32) | [1] | 0 | (0.00) | [0] |

| Haemoglobin decreased | 1 | (0.32) | [1] | 0 | (0.00) | [0] |

| Respiratory, thoracic, and mediastinal disorders | 1 | (0.32) | [1] | 1 | (0.69) | [1] |

| Cough | 1 | (0.32) | [1] | 0 | (0.00) | [0] |

| Oropharyngeal pain | 0 | (0.00) | [0] | 1 | (0.69) | [1] |

| Metabolism and nutrition disorders | 1 | (0.32) | [1] | 0 | (0.00) | [0] |

| Hyperkalaemia | 1 | (0.32) | [1] | 0 | (0.00) | [0] |

| Renal and urinary disorders | 1 | (0.32) | [1] | 0 | (0.00) | [0] |

| Nephropathy | 1 | (0.32) | [1] | 0 | (0.00) | [0] |

Discussion

The present study attempted to determine whether the maximal tolerated dose of valsartan is more beneficial than the low dose in attenuating post‐MI ventricular remodelling in Korean patients. Valsartan was selected because it is the only ARB agent that has been proven to have equivalent clinical efficacy as an ACE inhibitor in post‐MI patients.5 The results of the present study show that the maximal tolerated dose of the drug did not offer a greater benefit in terms of reducing ventricular size or improving function compared with low‐dose therapy in the study population. In addition, use of a high dose was associated with more frequent occurrence of drug‐related adverse reactions. These findings are not in accordance with the recommendations of current practical guidelines, which advocate the use of the highest tolerated dose of ACE inhibitors or ARB valsartan in post‐MI patients.6 Although current recommendations are based on large‐scale post‐MI trials, the issue of optimal dosing or intensity of angiotensin antagonism has not been directly addressed in those trials. In the VALIANT trial, intensification of therapy via combining ACE inhibitors and ARB has not produced improved clinical outcomes compared with treatment with the target dose recommended in the current guidelines.5 VALIANT clinical results have been mirrored in the VALIANT ECHO study, where combination therapy was not superior to either therapy alone in preserving or improving ventricular size and function after MI.15 The results of the present study are comparable with those of the VALIANT ECHO study in that a higher degree of angiotensin antagonism failed to bring about different echocardiographic outcomes. However, unlike the VALIANT ECHO study, which evaluated the efficacy of combined therapy over the recommended maximal dose, the present study compared efficacy between low‐dose and maximal‐tolerated‐dose therapies and found that therapy with the low dose is as efficacious as therapy with the recommended dose of valsartan in attenuating the process of post‐MI LV remodelling in a contemporary population of patients. Modest LV dysfunction in VALID subjects might account for the similar geometric changes between groups throughout the study period, but corresponding results were also observed in the subgroup of patients with baseline LVEF <40%. Further, changes in neurohormone levels, the secondary outcome of the present study, paralleled echocardiographic results. During the study period, plasma BNP and norepinephrine levels decreased from baseline in both study groups, and there was no significant difference in the magnitude of changes between groups receiving the two different doses. The neutral results of this study were also presented in the subgroup of patients with anterior MI.

It is difficult to explain the lack of superiority of higher‐dose therapy in the present study despite the previous observation in a population with heart failure that prognosis correlates with the degree of neurohumoral activation, which formed the rationale for aggressive pharmacological therapy.16 Obviously, the lack of sufficient number of subjects is a possible reason, but there may be other possible mechanisms accountable for the neutral results. One of the factors that might contribute to the neutral result of this study is the use of beta‐blockers in the study population. Beta‐blockers were used in 94.5% of the patients in both groups at baseline and 86.7% of the patients after 1 year. Beta‐blockers have been shown to prevent ventricular remodelling after acute MI17 and have exhibited a potent anti‐remodelling effect in patients with heart failure, which is greater than that observed in ACE inhibitor studies.18 Beta‐blockers can also provide an additional benefit by reducing the angiotensin II concentration in patients who receive ACE inhibitor treatment.19 Accumulating data suggest that, whereas ACE inhibitors seem to prevent progressive LV dilatation, beta‐blockers may actually reverse the remodelling process by reducing chamber size and improving systolic function.20 Therefore, it is possible that use of beta‐blockers might have diminished any potential differences between the two different dosage strategies. Additionally, too vigorous angiotensin suppression might be deleterious in the presence of background beta‐blocker therapy. In the Valsartan Heart Failure Trial, additional therapy with valsartan was associated with worse outcomes among patients receiving both beta‐blocker and ACE inhibitor treatments.21 This may be in part responsible for the tendency of favourable change in echocardiographic parameters in the low‐dose group shown in the present study, although it was not statistically significant. But the issue of adverse effect of intensive renin–angiotensin system (RAS) blockade in the presence of beta‐adrenergic blockers is still debatable, because such a finding was not replicated in the larger VALIANT study.5 Another factor may be related to the valsartan dose consumed by the study population. Valsartan at 80 mg/day in the low‐dose group may represent a high dosage for subjects with smaller body sizes, a common feature of adults in the Asia‐Pacific region. The mean body weight and height of patients in this study were 65 kg and 165 cm, respectively (mean body mass index, 23.8 kg/m2), which are substantially lower than those of the general Western population. Thus, 80 mg/day of valsartan in the low‐dose group might have been offering adequate RAS blockade, thereby reducing the difference in pharmacological effects between the study groups. On the other hand, the doses taken in the maximal‐tolerated‐dose group patients were smaller than those given to the patients' Western counterparts. The mean daily dose in the maximal‐tolerated‐dose group was 196.2 mg/day, with 32% of subjects taking the target dose, as compared with 247 mg/day and 56% taking the target dose in the VALIANT subgroup.5 Although those dosages may still represent the maximal tolerated dose in the Asian population and are 2.5 times greater than the amount given to the low‐dose group, it is possible that the higher doses did not produce as much of a difference in receptor antagonism because of the flatter slope of the dose–effect curve of valsartan in the higher dosage range.22 Such a dose–effect relationship may explain the similar systolic and diastolic BPs between the study groups during the study period. Previous clinical data also reported that both low‐dose valsartan treatment regimens (80 mg/day) and high‐dose treatment regimens (160 mg/day) resulted in a BP decrease to a similar level.23

During the study period, clinical events occurred infrequently in both study groups, but adverse effects were more frequently observed in the maximal‐tolerated‐dose group. The rate of drug‐related adverse effects, most commonly hypotension or hypotension‐related symptoms, was higher in the maximal‐tolerated‐dose group. These results occurred despite the dosage adjustment employed during the up‐titration period in the maximal‐tolerated‐dose group. Although ARBs are more tolerable than are ACE inhibitors in terms of cough or rash, treatment with the maximal dosage can lead to an equal or greater incidence of haemodynamic side effects such as hypotension or renal dysfunction, as demonstrated in a large‐scale study.5

Limitations

Several limitations of our study should be noted. First, the VALID study was underpowered for the primary endpoint. Because of the slow rate of enrolment, the number of patients in this study failed to reach the sample size as originally planned. Further, echocardiographic measurements were not conducted in all the subjects enrolled. Consequently, the possibility of neutral results derived from insufficient statistical power cannot be excluded. As a result of this particular limitation, extrapolation of the study result to general population should require exercise of caution. Second, echocardiographic measurements were not conducted in all the subjects enrolled. The basal echocardiographic profiles of the study patients showed only modest LV dysfunction, unlike those in larger post‐MI trials. This may reflect the successful reperfusion strategy of participating centres but may have led to less pronounced post‐MI remodelling and diluted the impact of pharmacological therapy. Actually, the efficacy of ACE inhibitor or ARB is not so clearly defined in modest‐risk post‐MI patients as in high‐risk patients. However, a protective role of RAS blockade on post‐MI remodelling is possible even in patients with mild LV dysfunction,24 and use of ACE inhibitors in all patients with STEMI remains a Class IIa recommendation in the current guidelines.6 Nonetheless, subjects with mild LV dysfunction is a weak point for measuring the impact of different dosing. Although the primary echocardiographic outcomes were similar in the small subset of patients with LVEF <40% or anterior MI and supported by the secondary objective of neurohumoral changes, these results require further verification in a larger study population exclusively composed of Asian patients who have significant LV dysfunction after MI. Third, because the study was conducted between 2008 and 2012, there is possibility that the latest pharmacological or device therapeutics was not employed during the study period.

Conclusions

Among Korean patients who suffered their first episode of acute STEMI, treatment with the maximal tolerated dose of valsartan did not exhibit an incremental benefit in attenuating post‐MI LV remodelling compared with a low dose of valsartan (80 mg/day). Maximal‐tolerated‐dose therapy was associated with more frequent drug‐related adverse events. For post‐MI Asian patients, judicious titration of valsartan rather than routine targeting up to high dosage may be an appropriate approach in terms of risk–benefit balance, but the small number of cases in the present study does not allow generalization of the results. Adequately powered studies are needed to verify the findings of the present study and clarify the efficacy and tolerability of maximal‐tolerated‐dose valsartan when given alongside modern evidence‐based therapies post‐MI.

Conflict of interest

Kyungil Park, Young‐Dae Kim, Ki‐Sik Kim, Su‐Hoon Lee, Tae‐Ho Park, Sang‐Gon Lee, Byung‐Soo Kim, Seung‐Ho Hur, Tae‐Hyun Yang, Joo‐Hyun Oh, Taek‐Jong Hong, Jong‐Sun Park, Jin‐Yong Hwang, Byungcheon Jeong, and Woo‐Hyung Bae declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Funding

This study was financially supported by Novartis Korea, Seoul, Korea. The funding body did not interfere in the analysis and interpretation of the data.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all members of the present study group for their ideas, suggestions, participation, and support.

Park, K. , Kim, Y.‐D. , Kim, K.‐S. , Lee, S.‐H. , Park, T.‐H. , Lee, S.‐G. , Kim, B.‐S. , Hur, S.‐H. , Yang, T.‐H. , Oh, J.‐H. , Hong, T.‐J. , Park, J.‐S. , Hwang, J.‐Y. , Jeong, B. , Bae, W.‐H. , and VALID Investigators (2018) The impact of a dose of the angiotensin receptor blocker valsartan on post‐myocardial infarction ventricular remodelling. ESC Heart Failure, 5: 354–363. doi: 10.1002/ehf2.12249.

References

- 1. Domanski MJ, Exner DV, Borkowf CB, Geller NL, Rosenberg Y, Pfeffer MA. Effect of angiotensin converting enzyme inhibition on sudden cardiac death in patients following acute myocardial infarction. A meta‐analysis of randomized clinical trials. J Am Coll Cardiol 1999; 33: 598–604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Pfeffer MA, Braunwald E, Moye LA, Basta L, Brown EJ, Cuddy TE, Davis BR, Geltman EM, Goldman S, Flaker GC, Klein M, Lamas GA, Packer M, Rouleau J, Rouleau JL, Rutherford J, Wertheimer JH, Hawkins CM, on behalf of the SAVE Investigators . Effect of captopril on mortality and morbidity in patients with left ventricular dysfunction after myocardial infarction. Results of the Survival and Ventricular Enlargement Trial. N Engl J Med 1992; 327: 669–677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. The Acute Infarction Ramipril Efficacy (AIRE) Study Investigators . Effect of ramipril on mortality and morbidity of survivors of acute myocardial infarction with clinical evidence of heart failure. Lancet 1993; 342: 821–828. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kober L, Trop‐Pedersen C, Carisen JE, Bagger H, Eliasen P, Lyngborg K, Videbek J, Cole DS, Auclert L, Pauly N, Aliot E, Persson S, Camm AJ, Trandolapril Cardiac Evaluation (TRACE) Study Group . A clinical trial of the angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitor trandolapril in patients with left ventricular dysfunction after myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med 1995; 333: 1670–1676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Pfeffer MA, McMurray JJV, Velazquez EJ, Rouleau JL, Kober L, Maggioni AP, Solomon SD, Swedberg K, Van de Werf F, White H, Leimberger JD, Henis M, Edwards S, Zelenkofske S, Sellers MA, Califf RM, Valsartan in Acute Myocardial Infarction Trial Investigators . Valsartan, captopril, or both in myocardial infarction complicated by heart failure, left ventricular dysfunction, or both. N Engl J Med 2003; 349: 1893–1906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. O'Gara PT, Kushner FG, Ascheim DD, Casey DE Jr, Chung MK, de Lemos JA, Ettinger SM, Fang JC, Fesmire FM, Franklin BA, Granger CB, Krumholz HM, Linderbaum JA, Morrow DA, Newby LK, Ornato JP, Ou N, Radford MJ, Tamis‐Holland JE, Tommaso CL, Tracy CM, Woo YJ, Zhao DX, Anderson JL, Jacobs AK, Halperin JL, Albert NM, Brindis RG, Creager MA, DeMets D, Guyton RA, Hochman JS, Kovacs RJ, Kushner FG, Ohman EM, Stevenson WG, Yancy CW. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of ST‐elevation myocardial infarction: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation 2013; 127: e362–e425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ibanez B, James S, Agewall S, Antunes MJ, Bucciarelli‐Ducci C, Bueno H, Caforio ALP, Crea F, Goudevenos JA, Halvorsen S, Hindricks G, Kastrati A, Lenzen MJ, Prescott E, Roffi M, Valgimigli M, Varenhorst C, Vranckx P, Widimský P. 2017 ESC guidelines for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST‐segment elevation: the Task Force for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST‐segment elevation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Developed in collaboration with the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC. Eur Heart J 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Benedict CR, Shelton B, Johnstone DE, Francis G, Greenberg B, Konstam M, Probstfield JL, Yusuf S, SOLVD Investigators . Prognostic significance of plasma norepinephrine in patients with asymptomatic left ventricular dysfunction. Circulation 1996; 94: 690–697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Packer M, Poole‐Wilson PA, Armstrong PW, Cleland JGF, Horowitz JD, Massie BM, Ryden L, Thygesen K, Uretsky BF, ATLAS Study Group . Comparative effects of low and high doses of angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitor, lisinopril, on morbidity and mortality in chronic heart failure. Circulation 1999; 100: 2312–2318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Clement DL, De Buyzere M, Tomas M, Vanavermaete G. Long‐term effects of clinical outcome with low and high dose in the Captopril in Heart Insufficiency Patients Study (CHIPS). Acta Cardiol 2000; 55: 1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. The NETWORK Investigators . Clinical outcome with enalapril in symptomatic chronic heart failure; a dose comparison. Eur Heart J 1998; 19: 481–489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Konstam MA, Neaton JD, Dickstein K, Drexler H, Kamajda M, Martinez FA, Riegger GAJ, Malbecq W, Smith RD, Gupta S, Poole‐Wilson PA, HEAAL Investigators . Effects of high‐dose versus losartan on clinical outcomes in patients with heart failure (HEAAL study): a randomised, double‐blind trial. Lancet 2009; 374: 1840–1848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Cho YR, Kim YD, Park TH, Park KI, Park HK, Choi SY, Kim KS, Hong TJ, Yang TH, Hwang JY, Park JS, Hur SH, Lee SG. The impact of dose of the angiotensin‐receptor blocker valsartan on the post‐myocardial infarction ventricular remodeling: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials 2011; 12: 247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lang RM, Bierig M, Devereux RB, Flachskampf FA, Foster E, Pellikka PA, Picard MH, Roman MJ, Seward J, Shanewise JS, Solomon SD, Spencer KT, Sutton MS, Stewart WJ. American Society of Echocardiography's Guidelines and Standard Committee: European Association of Echocardiography. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2005; 18: 1440–1463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Solomon SD, Skali H, Anavekar NS, Bourgoun M, Barvik S, Ghali JK, Warnica W, Khrakovskaya M, Arnold MO, Schwarz Y, Velazquez EJ, Califf RM, McMurray JV, Pfeffer MA. Changes in ventricular size and function in patients treated with valsartan, captopril, or both after myocardial infarction. Circulation 2005; 111: 3411–3419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Eichhorn EJ, Bristow MR. Medical therapy can improve the biological properties of the chronically failing heart. Circulation 1996; 94: 2285–2296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Doughty RN, Whalley GA, Walsh HA, Gamble GD, López‐Sendón J, Sharpe N, CAPRICORN Echo Substudy Investigators . Effects of carvedilol on left ventricular remodeling after acute myocardial infarction: the CAPRICORN Echo Substudy. Circulation 2004; 109: 201–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Doughty RN, Whalley GA, Gamble G, MacMahon S, Sharpe N, Australia–New Zealand Heart Failure Research Collaborative Group . Left ventricular remodeling with carvedilol in patients with congestive heart failure due to ischemic heart disease. J Am Coll Cardiol 1997; 29: 1060–1066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Campbell DJ, Aggarwal A, Esler M, Kaye D. Beta‐blockers, angiotensin II, and ACE inhibitors in patients with heart failure. Lancet 2001; 358: 1609–1610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Khattar RS. Effects of ACE inhibitors and beta‐blockers on left ventricular remodeling in chronic heart failure. Minerva Cardioangiol 2003; 51: 143–154. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Cohn JN, Tognoni G, Valsartan Heart Failure Trial Investigators . A randomized trial of the angiotensin‐receptor blocker valsartan in chronic heart failure. N Engl J Med 2001; 345: 1667–1675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Maillard MP, Wurzner G, Nussberger J, Centeno C, Burnier M, Brunner HR. Comparative angiotensin II receptor blockade in healthy volunteers. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2002; 71: 68–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Saikawa T, Sasaki J, Biro S, Kono S, Otonari T, Ikeda Y, DDV investigators . Is the reno‐protective effect of valsartan dose dependent? A comparative study of 80 and 160 mg day(−1). Hypertens Res 2010; 33: 886–891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. The PREAMI Investigators . Effects of angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibition with perindopril on left ventricular remodeling and clinical outcome. Results of the randomized perindopril and remodeling in elderly with acute myocardial infarction. Arch Intern Med 2006; 166: 659–666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]