Abstract

Aims

In heart failure, various biomarkers are established for diagnosis and risk stratification; however, little is known about the relevance of serial measurements during an episode worsening heart failure (WHF). This study sought to investigate the trajectory of natriuretic peptides and multiple novel biomarkers during hospitalization for WHF and to determine the best time point to predict outcome.

Methods and results

MOLITOR (Impact of Therapy Optimisation on the Level of Biomarkers in Patients with Acute and Decompensated Chronic Heart Failure) was an eight‐centre prospective study of 164 patients hospitalized with a primary diagnosis of WHF. C‐terminal fragment of pre‐pro‐vasopressin (copeptin), N‐terminal pro‐B‐type natriuretic peptide (NT‐proBNP), mid‐regional pro‐atrial natriuretic peptide (MR‐proANP), mid‐regional pro‐adrenomedullin (MR‐proADM), and C‐terminal pro‐endothelin‐1 (CT‐proET1) were measured on admission, after 24, 48, and 72 h, and every 72 h thereafter, at discharge and follow‐up visits. Their performance to predict all‐cause mortality and rehospitalization at 90 days was compared. All biomarkers decreased during recompensation (P < 0.05) except MR‐proADM. Copeptin at admission was the best predictor of 90 day mortality or rehospitalization (χ 2 = 16.63, C‐index = 0.724, P < 0.001), followed by NT‐proBNP (χ 2 = 10.53, C‐index = 0.646, P = 0.001), MR‐proADM (χ 2 = 9.29, C‐index = 0.686, P = 0.002), MR‐proANP (χ 2 = 8.75, C‐index = 0.631, P = 0.003), and CT‐proET1 (χ 2 = 6.60, C‐index = 0.64, P = 0.010). Re‐measurement of copeptin at 72 h and of NT‐proBNP at 48 h increased prognostic value (χ 2 = 23.48, C‐index = 0.718, P = 0.00001; χ 2 = 14.23, C‐index = 0.650, P = 0.00081, respectively).

Conclusions

This largest sample of serial measurements of multiple biomarkers in WHF found copeptin at admission with re‐measurement at 72 h to be the best predictor of 90 day mortality and rehospitalization.

Keywords: Worsening heart failure, Biomarker trajectory, Serial measurement, Copeptin

Introduction

Approximately 14 million people in the European Union have been diagnosed with heart failure (HF).1 Worsening heart failure (WHF) is the leading cause of hospital admissions worldwide and is associated with high morbidity and mortality. None of the prospective clinical trials have shown that any therapy started during hospitalization can improve mortality and risk of rehospitalization in these patients. Therefore, guidelines recommend mainly symptomatic therapy.1

To which degree WHF patients respond to the therapy ranges from uncomplicated recompensation to prolonged hospital stay with early readmission or even fatal outcome. Better prognostic assessment may help clinicians in identification of patients who should ‘move to the front of the line’ with respect to immediate therapeutic interventions.

The measurement of natriuretic peptides [i.e. N‐terminal pro‐B‐type natriuretic peptide (NT‐proBNP)] is frequently used2 to evaluate patients whose diagnosis of HF is uncertain. During hospitalization, natriuretic peptides are thought to be helpful in risk stratification,3, 4 and a fall in peptide levels correlate with a better prognosis.5, 6, 7, 8 Recently, other candidate peptides, such as mid‐regional pro‐adrenomedullin (MR‐proADM)2 and copeptin,9 were found to add prognostic value. Copeptin is C‐terminal fragment of pre‐pro‐vasopressin. Unlike vasopressin, it is stable and can be easily measured.10 Adrenomedullin is a vasodilatory peptide with hypotensive effects, and its levels are elevated in HF patients. However, since its plasma half‐life is only around 22 min, proADM is used as a trustworthy biomarker.11 Endothelin‐1 is a vasoconstrictor peptide, which is produced by vascular tissue, and increases blood pressure. HF patients are often found with elevated levels of ET‐1, as a result of neurohormonal activation.12 Due to its instability, the C‐terminal portion of pro‐endothelin‐1, which is much more stable, is commonly being measured. Atrial natriuretic peptide (ANP) is released from the atria as a response to elevated intra‐atrial pressure and wall stretch,13 but its concentrations are difficult to be measured due to its short half‐life (2–5 min).13 However, ANP's prohormone (proANP) has a longer half‐life, and its mid‐region (MR‐proANP) can be detected easily.14

Further, serial biomarker measurement in HF management has received growing interest for outcome prediction.15, 16 However, most authors assessed biomarkers only on admission and pointed out rare time points to re‐measure, for example, prior to discharge.7 Indeed, little is known about the exact trajectory of biomarkers during an episode of decompensation, and there has not been a comparison of the prognostic performance of serial measurements.17

The primary aim of this study was to determine the performance of serial in‐hospital measurements of natriuretic peptides and multiple novel biomarkers to predict outcome in WHF patients.

Methods

MOLITOR (Impact of Therapy Optimisation on the Level of Biomarkers in Patients with Acute and Decompensated Chronic Heart Failure) was an eight‐centre prospective study of 164 patients presenting to the emergency department with a primary diagnosis of WHF. The study is registered under http://clinicaltrials.gov (NCT01501981), sponsored by Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin, and financed by an unrestricted grant by BRAHMS AG (Neuendorfstr. 25, 16761 Hennigsdorf, Germany).

Study population

The institutional review boards of all participating centres approved the study, and all patients gave their written informed consent. In order to be considered as eligible, patients had to have signs and symptoms of HF with dyspnoea at rest or with minimal exertion [New York Heart Association (NYHA) class III and IV] and pulmonary congestion on physical examination or chest X‐ray. Patients were excluded if they had an alternative diagnosis that could account for the patient's HF symptoms, for example, significant pulmonary disease (history of oral daily steroid dependency, history of CO2 retention, or need for intubation for acute exacerbation); had suspected acute myocardial infarction, cardiogenic shock, sepsis or active infection requiring i.v. antimicrobial treatment; had significant arrhythmias (ventricular tachycardia, bradyarrhythmias with ventricular rate < 45 b.p.m., or atrial fibrillation/flutter with ventricular response of >150 b.p.m.), significant kidney disease with current or planned haemofiltration or dialysis, acute myocarditis, hypertrophic obstructive, restrictive, or constrictive cardiomyopathy; or were younger than 18 years. The primary endpoint was the best time point to predict all‐cause death or rehospitalization within 90 days.

Measurement of biomarkers

All blood samples were taken at admission, after 24, 48, and 72 h, and every 72 h thereafter, at discharge and at regular follow‐up visits. Blood samples were collected in ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (plasma separated within 60 min by centrifugation) and serum tubes and stored at −70°C in plastic freezer vials. NT‐proBNP (Elecsys 2010 analyzer, Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN) and copeptin and MR‐proANP (both on the KRYPTOR system) were measured centrally with the support of BRAHMS/Thermo Fisher, Germany. MR‐proADM was measured using an automated sandwich chemiluminescence immunoassay on the KRYPTOR system, as previously described.18, 19 For MR‐proADM, the limit of quantification was 0.23 nmol/L; the within‐run imprecision (coefficient of variation) was 1.9%, and the between‐run imprecision (coefficient of variation) was 9.8%. All blood samples were processed by personnel blinded from any patient data.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed by an independent trial biometrician in accordance with a pre‐defined statistical analysis plan. Descriptives of variables are expressed as mean ± standard deviation or median (Quartiles 1 and 3) for highly skewed variables, and n (%) for categorical variables. Values of biomarkers were log10 transformed prior to inclusion into regression models. Serial changes in biomarker levels during treatment optimization were assessed by Student t‐tests for paired samples on log10‐transformed data. Spearman rank correlation coefficients were calculated to assess the relationship between investigated biomarkers. For the primary endpoint all‐cause mortality/hospitalizations at 90 days, Cox regression models were built for each biomarker for baseline values (univariate). To determine the diagnostic accuracy of serum biomarker levels for the prediction of all‐cause mortality/hospitalization, receiver operating characteristic plots were analysed, and areas under the curve were calculated for all analytes. Areas under the curve were compared according to the method by Blanche. The whole study population of 164 patients with WHF was then stratified according to tertiles of copeptin and NT‐proBNP. Using the tertile approach, we computed Kaplan–Meier estimates of event‐free survival probabilities, and log‐rank tests were performed to compare survival curves between the groups. The time‐dependent Cox model was used to test whether there is a significant added value of the follow‐up measurements of biomarkers concentration on top of those obtained on admission.20 We defined the significance level 0.05 for all tests. R 3.0.2 software was used for all statistical analysis.

Results

Description of general population

A total of 164 patients (mean age 69, 70% male, mean left ventricular ejection fraction 34%, 76% in NYHA class III) were enrolled at eight sites in Germany, Serbia, and Slovenia. Table 1 displays demographic and clinical characteristics. Mean length of stay was 7 days. At 90 days, 18 (10.6%) patients had died and 24 (14.1%) were rehospitalized. Eight patients died during index hospitalization.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics at baseline according to events (all‐cause mortality/hospitalization) for the entire cohort (n = 164)

| All patients (n = 164) | Event free (n = 124) | Dead or rehospitalized (n = 40) | P‐value* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||||

| Age, years, mean (SD) | 68.3 (10) | 67.9 (10.2) | 69.5 (9.4) | 0.361 |

| Male sex, n (%) | 116 (70.7) | 89 (71.8) | 27 (67.5) | 0.751 |

| Clinical | ||||

| BMI | 29 (5.1) | 28.9 (5.2) | 29.1 (4.8) | 0.828 |

| Systolic blood pressure, mean (SD) | 136.7 (26.1) | 136.9 (25) | 135.8 (29.5) | 0.807 |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mean (SD) | 82.3 (14.8) | 83.6 (14.8) | 78.5 (14.3) | 0.055 |

| Heart rate, mean (SD) | 91.8 (20.9) | 93.3 (20.8) | 87.1 (20.6) | 0.101 |

| Heart rate in patients with sinus rhythm, mean (SD) | 88.9 (18.9) | 90.1 (18.1) | 83.8 (21.7) | 0.203 |

| Heart rate in patients with atrial fib, mean (SD) | 97.3 (21.5) | 100.1 (21.7) | 90.9 (20.2) | 0.111 |

| Pulmonary rales, n (%) | 161 (98.2) | 122 (98.4) | 39 (97.5) | 1.000 |

| Peripheral oedema, n (%) | 121 (73.8) | 89 (71.8) | 32 (80) | 0.411 |

| NYHA class III, n (%) | 124 (75.6) | 98 (79) | 26 (65) | 0.113 |

| NYHA class IV, n (%) | 40 (24.4) | 26 (21) | 14 (35) | 0.113 |

| Atrial fibrillation, n (%) | 65 (39.6) | 45 (36.3) | 20 (50) | 0.175 |

| LVEF (%), mean (SD) | 33.9 (12.5) | 34.3 (12.6) | 32.6 (12.2) | 0.451 |

| LVEDD (mm), mean (SD) | 61.9 (11.3) | 60.8 (11.5) | 65.3 (10.3) | 0.031 |

| Intraventricular septum diameter, mean (SD) | 10.5 (3.2) | 10.3 (3.4) | 11.2 (2.2) | 0.156 |

| PWED, mean (SD) | 9.9 (3.3) | 9.9 (3.5) | 10.1 (2.6) | 0.689 |

| E/e′, mean (SD) | 14.6 (21.7) | 14 (18.9) | 16.3 (28.3) | 0.670 |

| Pacemaker, n (%) | 5 (3) | 2 (1.6) | 3 (7.5) | 0.176 |

| ICD/CRT, n (%) | 9 (5.5) | 5 (4) | 4 (10) | 0.297 |

| Co‐morbidities | ||||

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 65 (39.6) | 49 (39.5) | 16 (40) | 1.000 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 137 (84.6) | 102 (83.6) | 35 (87.5) | 0.734 |

| GFR < 60, n (%) | 84 (51.9) | 58 (47.5) | 26 (65) | 0.083 |

| COPD, n (%) | 30 (19.1) | 19 (16.2) | 11 (27.5) | 0.183 |

| Current smoker, n (%) | 26 (16) | 23 (18.7) | 3 (7.7) | 0.167 |

| Ex‐smoker, n (%) | 54 (33.3) | 38 (30.9) | 16 (41) | 0.330 |

| Medication | ||||

| Beta‐blockers | 105 (64) | 80 (64.5) | 25 (62.5) | 0.967 |

| ACE inhibitors/angiotensin receptor blockers | 129 (78.7) | 99 (79.8) | 30 (75) | 0.669 |

| MR antagonists | 108 (65.9) | 87 (70.2) | 21 (52.5) | 0.063 |

| Glycosides | 72 (43.9) | 49 (39.5) | 23 (57.5) | 0.070 |

| Loop diuretics | 161 (98.2) | 121 (97.6) | 40 (100) | 0.753 |

| Nitrates | 15 (9.1) | 9 (7.3) | 6 (15) | 0.245 |

| Biomarkers at baseline, median [IQR] | ||||

| Copeptin (pmol/L) | 31.4 [16.8–48.5] | 26.6 [13.5–41.1] | 47 [33.8–64.9] | <0.001 |

| NT‐proBNP (pg/mL) | 3894 [1605–11592] | 3414 [1541–8491] | 9279 [2472–18499] | 0.003 |

| MR‐proANP (pmol/L) | 375.5 [220.4–599.6] | 347.1 [218.4–525.3] | 568.9 [295.7–796] | 0.012 |

| MR‐proADM (nmol/L) | 1.23 [0.85–2.02] | 1.1 [0.84–1.63] | 1.75 [1.11–3.4] | 0.001 |

| CT‐proET1 (pmol/L) | 122.7 [81.9–194.5] | 112.9 [80.2–182.6] | 170.3 [99–232.4] | 0.014 |

ACE, angiotensin‐converting enzyme; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CT‐proET1, C‐terminal endothelin‐1 precursor fragment; GFR, glomerular filtration rate; ICD/CRT, implantable cardioverter defibrillator/cardiac resynchronization therapy; IQR, interquartile range; LVEDD, left ventricular end‐diastolic diameter; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; MR‐proADM, mid‐regional pro‐adrenomedullin; MR‐proANP, mid‐regional pro‐atrial natriuretic peptide; NT‐proBNP, N‐terminal pro‐B‐type natriuretic peptide; PWED, end‐diastolic posterior wall; SD, standard deviation.

Data are presented as n (%), mean ± SD, or median [25th–75th percentiles].

P < 0.05.

Serial in‐hospital changes of biomarkers

All biomarkers decreased significantly from admission to discharge (P < 0.05) except MR‐proADM (Table 2). All baseline biomarker levels correlated significantly, with a high correlation found for the natriuretic peptides and between MR‐proADM and C‐terminal pro‐endothelin‐1 (CT‐proET1; Table 3).

Table 2.

Serial in‐hospital changes of studied biomarkers

| Biomarker | Baseline (n = 164) | 24 h (n = 160) | 48 h (n = 155) | 72 h (n = 140) | Discharge (n = 153) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Copeptin (pmol/L) | 31.4 [16.8–48.5] | 27.2 [16.3–42.6]* | 27.9 [15.3–40.5] | 27.1 [15.9–39.5]* | 23.5 [14.8–36.1]* |

| NT‐proBNP (pg/mL) | 3894 [1605–11592] | 3194 [1220–8426]** | 2505 [689–7720]** | 2698 [758–8424]** | 1808 [613–4259]** |

| MR‐proANP (pmol/L) | 375.5 [220.4–599.6] | 355.1 [211.8–568.8]** | 340.5 [207.5–543.5]** | 328.2 [203.5–596.5]** | 300.9 [182.6–481.6]** |

| MR‐proADM (nmol/L) | 1.23 [0.85–2.02] | 1.15 [0.81–1.87]* | 1.08 [0.77–1.71]** | 1.04 [0.75–1.73]** | 1.03 [0.76–1.49]** |

| CT‐proET1 (pmol/L) | 122.7 [81.9–194.5] | 109 [78.3–175.8]* | 104.7 [75.2–155.3]** | 104.9 [75–155.6]** | 99.1 [73–142.7]** |

CT‐proET1, C‐terminal endothelin‐1 precursor fragment; MR‐proADM, mid‐regional pro‐adrenomedullin; MR‐proANP, mid‐regional pro‐atrial natriuretic peptide; NT‐proBNP, N‐terminal pro‐B‐type natriuretic peptide.

Data are presented as median [25th–75th percentiles].

P < 0.05.

P < 0.001.

Table 3.

Non‐parametric correlation between baseline plasma concentrations of studied biomarkers

| NT‐proBNP | MR‐proANP | MR‐proADM | CT‐proET1 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Copeptin | 0.54 | 0.56 | 0.56 | 0.50 |

| NT‐proBNP | 0.84 | 0.48 | 0.53 | |

| MR‐proANP | 0.63 | 0.65 | ||

| MR‐proADM | 0.90 |

CT‐proET1, C‐terminal endothelin‐1 precursor fragment; MR‐proADM, mid‐regional pro‐adrenomedullin; MR‐proANP, mid‐regional pro‐atrial natriuretic peptide; NT‐proBNP, N‐terminal pro‐B‐type natriuretic peptide.

Spearman's coefficient of correlation (P < 0.001 for all correlations).

Prognostic value of biomarker levels at baseline

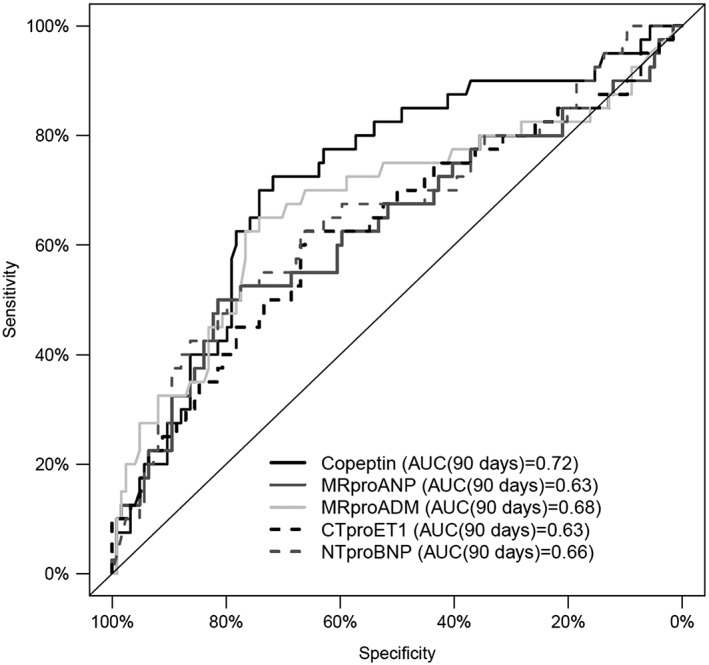

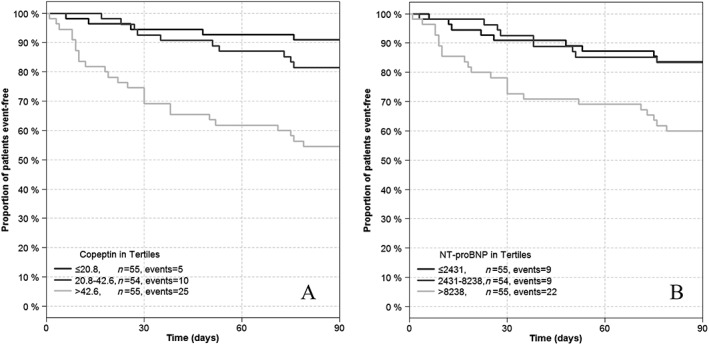

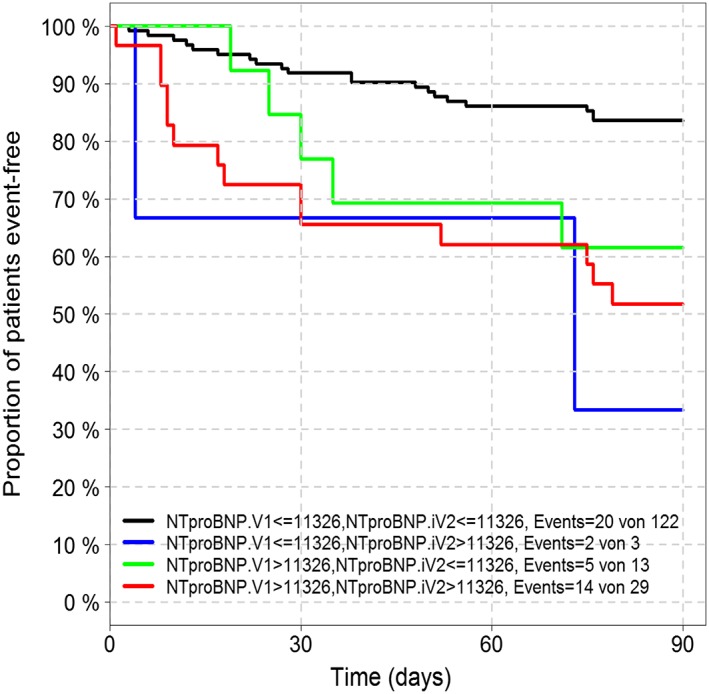

The prognostic value for all‐cause mortality/hospitalization at 90 days is presented with the receiver operating characteristic curves in Figure 1. All biomarkers at admission, except for CT‐proET1, were significant univariate outcome predictors (Table 4). At baseline, copeptin was the strongest predictor (χ 2 = 16.63, C‐index = 0.724, P < 0.001), followed by NT‐proBNP (χ 2 = 10.53, C‐index = 0.646, P = 0.001). Similarly, copeptin showed a trend (P = 0.0565) towards a 19% improvement of net reclassification for patients at the highest risk of 90 day mortality or rehospitalization (95% confidence interval [−0.5, 39.1]). Defining a copeptin threshold of 37.2 pmol/L at baseline, the positive and negative predictive values of all‐cause death/hospitalization were 45.3% and 89%, respectively. Likewise, sensitivity and specificity for this cut‐off were 72.5% and 71.8%. Addition of baseline copeptin levels to baseline NT‐proBNP levels significantly improved its prognostic performance for 90 day outcome [model likelihood ratio (LR) χ 2 = 17.80, C‐index = 0.688, P = 0.004], unlike in the addition of other novel cardiac biomarkers including MR‐proADM (data not shown). Figure 2 shows Kaplan–Meier curves for three groups of patients stratified according to the tertiles plasma concentrations of copeptin (Figure 2 A) and NT‐proBNP (Figure 2 B). The highest tertile of baseline copeptin and NT‐proBNP was related with the worst prognosis at 3 months' follow‐up (Figure 3 ).

Figure 1.

Receiver operating characteristic plot demonstrating the capacity of the five biomarkers at hospital admission to predict 90 day all‐cause mortality/hospitalization in 164 patients with acute heart failure.

Table 4.

Prognostic value of in‐hospital baseline biomarker levels for the prediction of 90 day all‐cause mortality/hospitalization in 164 hypertensive heart failure patients

| n | Events | Model LR χ 2 | d.f. | P‐value | C‐index | 95% CI | HR (per IQR) | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CT‐proET1 | 164 | 40 | 2.57 | 1 | 0.109 | 0.618 | [0.523, 0.714] | 1.32 | [0.91–1.92] |

| MR‐proADM | 164 | 40 | 4.03 | 1 | 0.045 | 0.658 | [0.562, 0.753] | 1.33 | [0.98–1.82] |

| MR‐proANP | 164 | 40 | 6.84 | 1 | 0.009 | 0.620 | [0.524, 0.716] | 1.76 | [1.15–2.69] |

| NT‐proBNP | 164 | 40 | 9.60 | 1 | 0.002 | 0.641 | [0.55, 0.733] | 2.08 | [1.27–3.40] |

| Copeptin | 164 | 40 | 13.98 | 1 | <0.001 | 0.707 | [0.622, 0.792] | 2.02 | [1.44–2.84] |

CI, confidence interval; CT‐proET1, C‐terminal endothelin‐1 precursor fragment; HR, hazard ratio; IQR, interquartile range; LR, likelihood ratio; MR‐proADM, mid‐regional pro‐adrenomedullin; MR‐proANP, mid‐regional pro‐atrial natriuretic peptide; NT‐proBNP, N‐terminal pro‐B‐type natriuretic peptide.

Figure 2.

Kaplan–Meier analysis of event‐free survival in respect to the tertiles of baseline copeptin (A) and N‐terminal pro‐B‐type natriuretic peptide (B).

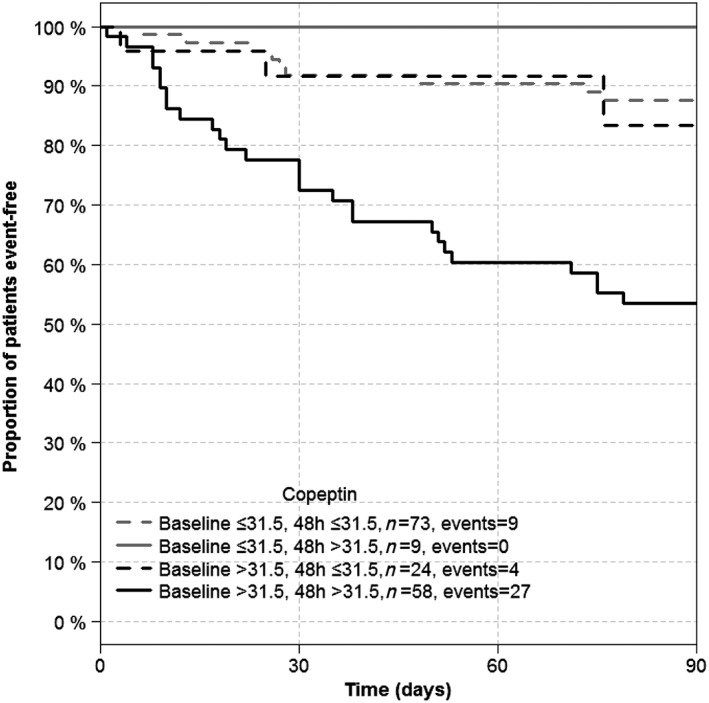

Figure 3.

Kaplan–Meier analysis of event‐free survival according to the change of copeptin circulating concentration after 48 h of hospitalization.

Prognostic performance of serial in‐hospital measurements of biomarkers

The best time point for re‐measurement of copeptin was 72 h after admission, and then its predictive value was increased (copeptin χ 2 = 23.48, C‐index = 0.718, P = 0.00001). Patients with levels <50 pmol/L at admission and at 72 h had the best prognosis, while patients with low levels at admission that increased after 72 h had an even worse prognosis than had patients with elevated levels at admission (>50 pmol/L) (see Figure 4). Patients with persistently elevated copeptin during the first 72 h after initial in‐hospital evaluation had the worst prognosis at 3 months' follow‐up. With the unadjusted adapted time‐dependent Cox model, we found a significant added value of the re‐measurement of copeptin. The gain of additional measurement can be observed as early as 48 hours after inclusion (LR χ 2 = 19.08, added χ 2 = 5.1, P = 0.024). The significant added value of copeptin re‐measurement after 48 h persisted even after adjustment for age, gender, and NYHA functional class (LR χ 2 = 27.31, added χ 2 = 6.43, P = 0.011).

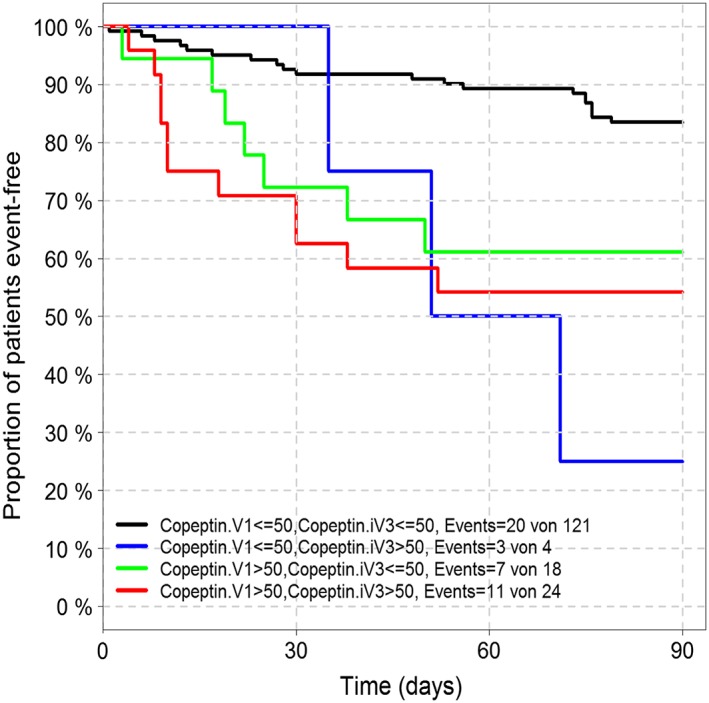

Figure 4.

Kaplan–Meier analysis of event‐free survival according to the change of copeptin circulating concentration after 72 h of hospitalization.

Re‐measurement of NT‐proBNP after 48 h showed the highest predictive value (NT‐pro BNP χ 2 = 14.23, C‐index = 0.650, P < 0.001). Patients with low NT‐proBNP levels on admission and 48 h had the best prognosis. Patients with low biomarker levels at admission that increased after 48 h had an even worse prognosis than had patient with elevated levels at admission (see Figure 5). Biomarker assessment at discharge did not provide additional information.

Figure 5.

Kaplan–Meier analysis of event‐free survival according to the change of N‐terminal pro‐B‐type natriuretic peptide concentration after 48 h of hospitalization.

Unlike that of copeptin and NT‐proBNP, re‐measurement of other investigated biomarkers (MR‐proANP, MR‐proADM, and CT‐proET1) during hospital stay did not provide incremental value over a single determination at hospital admission (data not shown).

Discussion

This is the largest sample of serial in‐hospital measurements of novel biomarker in a typical sample of WHF patients during hospitalization. The mean ejection fraction of the patients in this study was ~34%, which can be considered moderately reduced compared with that of other acute decompensated HF studies.

Copeptin was the strongest predictor for all‐cause mortality/hospitalization at 90 days. Addition of baseline copeptin levels to baseline NT‐proBNP levels significantly improved its prognostic performance for 90 day outcome. The best time point for re‐measurement was 72 h, showing that patients with persistently elevated copeptin had the worst prognosis at 3 months' follow‐up.

In line with our results, patients with WHF and elevated copeptin levels were at increased risk of 90 day mortality, readmissions, and emergency department visits.2 Additionally, Gegenhuber et al. demonstrated that increased levels of copeptin, BNP, MR‐proANP, and MR‐proADM of patients with WHF at admission independently indicated an increased risk of 1 year mortality.5 Another study that included 172 patients with chronic stable HF showed that copeptin was an excellent predictor of outcome during a median period of 1301 days.6 Similarly, copeptin levels predicted mortality in stable patients with chronic HF independently from clinical variables, including plasma sodium levels and loop diuretic doses.7 Even after a 13 year follow‐up period, copeptin levels demonstrated a prognostic value for mortality risk in 470 elderly patients with HF.8 In the BACH (Biomarkers in Acute Heart Failure) study, in patients presenting to the emergency room with dyspnoea, elevated copeptin levels were associated with increased 90 day mortality, HF‐related admission, and HF‐related emergency department visits.2 Thus, current literature outlines the prognostic value of copeptin in patients with HF.

Another publication showed similarly to ours that adding copeptin to NT‐proBNP improved its long‐term prognostic performance for mortality in elderly patients with HF.21 Additionally, the combination of increased concentration of copeptin and NT‐proBNP was found to be related with enhanced risk of all‐cause mortality during a median period of 13 years in 470 elderly patients with symptoms of HF.8 Another study showed that a decrease in NT‐proBNP levels in patients with WHF was associated with better prognosis.22

Our study showed that repeated measurement of copeptin 72 h after admission may be advised for the improvement of risk stratification. Persistently elevated copeptin levels during hospitalization, from admission to 72 h, seem to be related with worse outcome. Despite the fact that a single measurement of a biomarker during the progression of a disease may predict the outcome, there is currently much interest in using serial biomarker measurements for monitoring the drug therapy response.23, 24, 25 One recent study evaluated copeptin variations during hospitalization and its prognostic significance in patients with dyspnoea at emergency departments.26 It demonstrated that dyspnoeic patients with high levels of copeptin at both hospital admission and discharge had significantly higher risk of developing events (death or rehospitalization) at 90 days. In line with our results, the authors demonstrated that there was a better 90 day prognosis in dyspnoeic patients with a higher decrease of copeptin from admission to discharge compared with patients who showed a lower decrease of copeptin. Additionally, this study showed that in both acute HF and non‐acute HF patients, a great reduction of copeptin from admission to discharge is desirable and is linked to a better outcome. An increase in copeptin concentration between baseline and 1 month was associated with an increased risk of death and the composite cardiovascular endpoint in patient with HF after an acute myocardial infarction.27 Increases in copeptin and MR‐proANP detected by serial measurements during follow‐up in ambulatory patients with chronic HF appear to be common and predictive of increased risk of short‐term events including death.28

In contrast to these results, another study showed that a relative change of copeptin levels in patients after HF hospitalization (3 month follow‐up vs. discharge value) did not contribute in risk stratification of these patients, because no pattern of improvement or of worsening added any prognostic information.29 This study included a cohort of stable HF patients undergoing treatment optimization. Similarly, another study with stable HF patients showed that change of copeptin at 3 months compared with that at baseline did not provide new prognostic value.30

During an episode of WHF treatment, intervention rapidly resets neurohormonal values to their steady state. That is why serial measurements of biomarkers in the context of WHF may be more valuable than that in the context of chronic HF. For BNP and NT‐proBNP, studies evaluating the influence of treatment on hormone concentrations have shown that therapeutic inhibition of the renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system decreases peptide levels, while beta‐blockade results in an initial increase followed by a decline.31, 32, 33 To reap the full prognostic benefit of repeated measurements, a time frame has to be defined including the point at which re‐measurement of specific biomarker may provide additional information. This is key for further studies on the efficacy of neurohormonal‐guided therapy, which have failed to show benefit so far.

Limitation of the study

Major limitations of this study were the small sample of patients observed and short follow‐up period. This resulted in a relatively small number of 90 day events.

Conclusions

Serial in‐hospital measurements of copeptin levels among hypertensive HF patients provide additional prognostic values for all‐cause mortality/hospitalizations, unlike those of other cardiac biomarkers (MR‐proADM, MR‐proANP, and CT‐proET1). Patients with persistently elevated copeptin during the first 72 h after initial in‐hospital evaluation had the worst prognosis at 3 months' follow‐up. Copeptin levels at hospital admission increased the prognostic value of NT‐proBNP, the established biomarker in HF.

Conflict of interest

H.‐D.D. reported receiving grant support from Thermo Fisher Scientific, Hennigsdorf, Germany.

Funding

This work was supported by Thermo Fisher Scientific, Hennigsdorf, Germany.

Düngen, H.‐D. , Tscholl, V. , Obradovic, D. , Radenovic, S. , Matic, D. , Musial Bright, L. , Tahirovic, E. , Marx, A. , Inkrot, S. , Hashemi, D. , Veskovic, J. , Apostolovic, S. , von Haehling, S. , Doehner, W. , Cvetinovic, N. , Lainscak, M. , Pieske, B. , Edelmann, F. , Trippel, T. , and Loncar, G. (2018) Prognostic performance of serial in‐hospital measurements of copeptin and multiple novel biomarkers among patients with worsening heart failure: results from the MOLITOR study. ESC Heart Failure, 5: 288–296. doi: 10.1002/ehf2.12231.

Clinical Trial Registration: http://clinicaltrials.gov. Unique identifier: NCT01501981

References

- 1. McMurray JJ, Adamopoulos S, Anker SD, Auricchio A, Böhm M, Dickstein K, Falk V, Filippatos G, Fonseca C, Gomez‐Sanchez MA, Jaarsma T, Køber L, Lip GY, Maggioni AP, Parkhomenko A, Pieske BM, Popescu BA, Rønnevik PK, Rutten FH, Schwitter J, Seferovic P, Stepinska J, Trindade PT, Voors AA, Zannad F, Zeiher A, Task Force for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Acute and Chronic Heart Failure 2012 of the European Society of Cardiology , Bax JJ, Baumgartner H, Ceconi C, Dean V, Deaton C, Fagard R, Funck‐Brentano C, Hasdai D, Hoes A, Kirchhof P, Knuuti J, Kolh P, McDonagh T, Moulin C, Popescu BA, Reiner Z, Sechtem U, Sirnes PA, Tendera M, Torbicki A, Vahanian A, Windecker S, McDonagh T, Sechtem U, Bonet LA, Avraamides P, Ben Lamin HA, Brignole M, Coca A, Cowburn P, Dargie H, Elliott P, Flachskampf FA, Guida GF, Hardman S, Iung B, Merkely B, Mueller C, Nanas JN, Nielsen OW, Orn S, Parissis JT, Ponikowski P, ESC Committee for Practice Guidelines . ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure 2012: The Task Force for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Acute and Chronic Heart Failure 2012 of the European Society of Cardiology. Developed in collaboration with the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC. Eur J Heart Fail 2012; 14: 803–869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Maisel A, Mueller C, Nowak RM, Peacock WF, Ponikowski P, Mockel M, Hogan C, Wu AH, Richards M, Clopton P, Filippatos GS, Di Somma S, Anand I, Ng LL, Daniels LB, Neath SX, Christenson R, Potocki M, McCord J, Hartmann O, Morgenthaler NG, Anker SD. Midregion prohormone adrenomedullin and prognosis in patients presenting with acute dyspnea: results from the BACH (Biomarkers in Acute Heart Failure) trial. J Am Coll Cardiol 2011; 58: 1057–1067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Blanche P, Dartigues JF, Jacqmin‐Gadda H. Estimating and comparing time‐dependent areas under receiver operating characteristic curves for censored event times with competing risks. Stat Med 2013; 32: 5381–5397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hartmann O, Schuetz P, Albrich WC, Anker SD, Mueller B, Schmidt T. Time‐dependent Cox regression: serial measurement of the cardiovascular biomarker proadrenomedullin improves survival prediction in patients with lower respiratory tract infection. Int J Cardiol 2012; 161: 166–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Gegenhuber A, Struck J, Dieplinger B, Poelz W, Pacher R, Morgenthaler NG, Bergmann A, Haltmayer M, Mueller T. Comparative evaluation of B‐type natriuretic peptide, mid‐regional pro‐A‐type natriuretic peptide, mid‐regional pro‐adrenomedullin, and Copeptin to predict 1‐year mortality in patients with acute destabilized heart failure. J Card Fail 2007; 13: 42–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Tentzeris I, Jarai R, Farhan S, Perkmann T, Schwarz MA, Jakl G, Wojta J, Huber K. Complementary role of copeptin and high‐sensitivity troponin in predicting outcome in patients with stable chronic heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail 2011; 13: 726–733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Balling L, Kistorp C, Schou M, Egstrup M, Gustafsson I, Goetze JP, Hildebrandt P, Gustafsson F. Plasma copeptin levels and prediction of outcome in heart failure outpatients: relation to hyponatremia and loop diuretic doses. J Card Fail 2012; 18: 351–358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Alehagen U, Dahlström U, Rehfeld JF, Goetze JP. Association of copeptin and N‐terminal proBNP concentrations with risk of cardiovascular death in older patients with symptoms of heart failure. JAMA 2011; 305: 2088–2095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Maisel A, Xue Y, Shah K, Mueller C, Nowak R, Peacock WF, Ponikowski P, Mockel M, Hogan C, Wu AH, Richards M, Clopton P, Filippatos GS, Di Somma S, Anand IS, Ng L, Daniels LB, Neath SX, Christenson R, Potocki M, McCord J, Terracciano G, Kremastinos D, Hartmann O, von Haehling S, Bergmann A, Morgenthaler NG, Anker SD. Increased 90‐day mortality in patients with acute heart failure with elevated copeptin: secondary results from the Biomarkers in Acute Heart Failure (BACH) study. Circ Heart Fail 2011; 4: 613–620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Jia J, Chang GL, Qin S, Chen J, He WY, Lu K, Li Y, Zhang DY. Comparative evaluation of copeptin and NT‐proBNP in patients with severe acute decompensated heart failure, and prediction of adverse events in a 90‐day follow‐up period: a prospective clinical observation trial. Exp Ther Med 2017. Apr; 13: 1554–1560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. von Haehling S, Filippatos GS, Papassotiriou J, Cicoira M, Jankowska EA, Doehner W, Rozentryt P, Vassanelli C, Struck J, Banasiak W, Ponikowski P, Kremastinos D, Bergmann A, Morgenthaler NG, Anker SD. Mid‐regional pro‐adrenomedullin as a novel predictor of mortality in patients with chronic heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail 2010. May; 12: 484–491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Abukar Y, May CN, Ramchandra R. Role of endothelin‐1 in mediating changes in cardiac sympathetic nerve activity in heart failure. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 2016. Jan 1; 310: R94–R99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lindberg S, Jensen JS, Pedersen SH, Galatius S, Goetze JP, Mogelvang R. MR‐proANP improves prediction of mortality and cardiovascular events in patients with STEMI. Eur J Prev Cardiol 2015. Jun; 22: 693–700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Zografos T, Katritsis D. Natriuretic peptides as predictors of atrial fibrillation recurrences following electrical cardioversion. Arrhythm Electrophysiol Rev 2013. Nov; 2: 109–114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Yalta K, Yalta T, Sivri N, Yetkin E. Copeptin and cardiovascular disease: a review of a novel neurohormone. Int J Cardiol 2013; 167: 1750–1759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Gottlieb SS, Kukin ML, Ahern D, Packer M. Prognostic importance of atrial natriuretic peptide in patients with chronic heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol 1989; 13: 1534–1539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Loncar G, Omersa D, Cvetinovic N, Arandjelovic A, Lainscak M. Emerging biomarkers in heart failure and cardiac cachexia. Int J Mol Sci 2014. Dec 22; 15: 23878–23896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Logeart D, Thabut G, Jourdain P, Chavelas C, Beyne P, Beauvais F, Bouvier E, Solal AC. Predischarge B‐type natriuretic peptide assay for identifying patients at high risk of re‐admission after decompensated heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol 2004; 43: 635–641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bayés‐Genís A, Lopez L, Zapico E, Cotes C, Santaló M, Ordonez‐Llanos J, Cinca J. NT‐ProBNP reduction percentage during admission for acutely decompensated heart failure predicts long‐term cardiovascular mortality. J Card Fail 2005; 11: S3–S8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hartmann O, Schuetz P, Albrich WC, Anker SD, Mueller B, Schmidt T. Time‐dependent Cox regression: serial measurement of the cardiovascular biomarker proadrenomedullin improves survival prediction in patients with lower respiratory tract infection. Int J Cardiol 2012. Nov 29; 161: 166–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Morgenthaler NG, Struck J, Alonso C, Bergmann A. Assay for the measurement of copeptin, a stable peptide derived from the precursor of vasopressin. Clin Chem 2006; 52: 112–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bettencourt P, Azevedo A, Pimenta J, Friões F, Ferreira S, Ferreira A. N‐terminal‐pro‐brain natriuretic peptide predicts outcome after hospital discharge in heart failure patients. Circulation 2004; 110: 2168–2174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Miller WL, Hartman KA, Burritt MF, Grill DE, Rodeheffer RJ, Burnett JC Jr, Jaffe AS. Serial biomarker measurements in ambulatory patients with chronic heart failure: the importance of change over time. Circulation 2007; 116: 249–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Jourdain P, Jondeau G, Funck F, Gueffet P, Le Helloco A, Donal E, Aupetit JF, Aumont MC, Galinier M, Eicher JC, Cohen‐Solal A, Juillière Y. Plasma brain natriuretic peptide‐guided therapy to improve outcome in heart failure: the STARS‐BNP Multicenter Study. J Am Coll Cardiol 2007; 49: 1733–1739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Troughton RW, Richards AM. Outpatient monitoring and treatment of chronic heart failure guided by amino‐terminal pro‐B‐type natriuretic peptide measurement. Am J Cardiol 2008; 101: 72–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Vetrone F, Santarelli S, Russo V, Lalle I, De Berardinis B, Magrini L, Di Stasio E, Salerno G, Cardelli P, Piccoli A, Codognotto M, Mion MM, Plebani M, Vettore G, Castello LM, Avanzi GC, Di Somma S. Copeptin decrease from admission to discharge has favorable prognostic value for 90‐day events in patients admitted with dyspnea. Clin Chem Lab Med 2014; 52: 1457–1464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Voors AA, von Haehling S, Anker SD, Hillege HL, Struck J, Hartmann O, Bergmann A, Squire I, van Veldhuisen DJ, Dickstein K, OPTIMAAL Investigators . C‐terminal provasopressin (copeptin) is a strong prognostic marker in patients with heart failure after an acute myocardial infarction: results from the OPTIMAAL study. Eur Heart J 2009; 30: 1187–1194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Miller WL, Hartman KA, Grill DE, Struck J, Bergmann A, Jaffe AS. Serial measurements of midregion proANP and copeptin in ambulatory patients with heart failure: incremental prognostic value of novel biomarkers in heart failure. Heart 2012; 98: 389–394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Neuhold S, Huelsmann M, Strunk G, Struck J, Adlbrecht C, Gouya G, Elhenicky M, Pacher R. Prognostic value of emerging neurohormones in chronic heart failure during optimization of heart failure‐specific therapy. Clin Chem 2010; 56: 121–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Masson S, Latini R, Carbonieri E, Moretti L, Rossi MG, Ciricugno S, Milani V, Marchioli R, Struck J, Bergmann A, Maggioni AP, Tognoni G, Tavazzi L, Investigators GISSI‐HF. The predictive value of stable precursor fragments of vasoactive peptides in patients with chronic heart failure: data from the GISSI‐heart failure (GISSI‐HF) trial. Eur J Heart Fail 2010; 12: 338–347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Loncar G, von Haehling S, Tahirovic E, Inkrot S, Mende M, Sekularac N, Lainscak M, Apostolovic S, Putnikovic B, Edelmann F, Wachter R, Dimkovic S, Waagstein F, Gelbrich G, Düngen HD. Effect of beta blockade on natriuretic peptides and copeptin in elderly patients with heart failure and preserved or reduced ejection fraction: results from the CIBIS‐ELD trial. Clin Biochem 2012; 45: 117–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Anand IS, Fisher LD, Chiang YT, Latini R, Masson S, Maggioni AP, Glazer RD, Tognoni G, Cohn JN, Investigators V‐HFT. Changes in brain natriuretic peptide and norepinephrine over time and mortality and morbidity in the Valsartan Heart Failure Trial (Val‐HeFT). Circulation 2003; 107: 1278–1283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Rousseau MF, Gurné O, Duprez D, Van Mieghem W, Robert A, Ahn S, Galanti L, Ketelslegers JM, Belgian RALES Investigators . Beneficial neurohormonal profile of spironolactone in severe congestive heart failure: results from the RALES neurohormonal substudy. J Am Coll Cardiol 2002; 40: 1596–1601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]