Abstract

Objective

Pharmacotherapy to rapidly relieve suicidal ideation in depression may reduce suicide risk. Rapid reduction in suicidal thoughts after ketamine treatment has mostly been studied in patients with low levels of suicidal ideation.

Method

This randomized clinical trial tested the effect of adjunctive sub-anesthetic intravenous ketamine on clinically significant suicidal ideation in major depressive disorder (MDD). Adults (N=80) with current MDD and score ≥4 on the Scale for Suicidal Ideation (SSI), of whom 54% (N=43) were taking antidepressant medication, were randomized to ketamine or midazolam infusion. The primary outcome was Day 1 SSI score (24 hours post-infusion). Other outcomes included global depression and adverse effects.

Results

Reduction of SSI score was 4.96 points greater after ketamine compared with midazolam at Day 1 (95% confidence interval (CI)=2.33 to 7.59; p=0.0003; Cohen’s d=0.75). Proportion of responders (≥50% reduction in SSI) at Day 1 was 55% after ketamine and 30% after midazolam (OR=2.85 (95% CI=1.14 to 7.15); p=0.0237; NNT=4.00). Improvement in the Profile of Mood States (POMS) depression subscale was greater at Day 1 compared with midazolam treatment (Estimate=7.65 (95% CI=1.36 to 13.94), df=75, t=2.42, p=0.0178), and this effect mediated 33.6% of ketamine’s effect on SSI score. Side effects were short-lived. Benefit was sustained for up to six weeks with clinical pharmacotherapy.

Conclusions

Adjunctive ketamine demonstrated greater reduction of clinically significant suicidal ideation in depressed patients within 24 hours compared to midazolam, partially independent of antidepressant effect. Research is needed to understand ketamine’s mechanism of action and to develop safe, longer-term treatment.

Introduction

There is a lack of evidence-based pharmacotherapy for suicidal patients with major depressive disorder (MDD). The 26.5% increase in US suicide rates from 1999 to 2015 (1) underscores this treatment need. The American Psychiatric Association’s guideline states, “evidence for a lowering of suicide rates with antidepressant treatment is inconclusive”(2). Standard antidepressants may reduce suicidal ideation and behavior in depressed adults, mediated by improvement in depression, but this effect takes weeks (3). Other somatic treatments with some evidence for anti-suicidal effects include clozapine in schizophrenia (4), and ECT (5) and lithium (6) in mood disorders.

Suicidal depressed patients need rapid relief of suicidal ideation. Depression remits in a third or fewer patients, and less than half achieve even 50% relief with typical first-line medication (7). Although suicidal behavior is usually associated with depression (8), most antidepressant trials have excluded suicidal patients and did not assess ideation and behavior systematically, limiting data (9). Depression predicts suicide attempts via its effect on suicidal ideation (10).

Ketamine, approved by the FDA in 1970 for anesthetic use, is a drug with dissociative and glutamate receptor-blocking properties, and has recently become a target of research for its antidepressant effects within hours at sub-anesthetic doses (11). Reports of reduction in suicidal ideation after ketamine infusion are promising, but measurement of suicidal ideation with a single item from a depression inventory such as the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS) (12–16), lack of control group (15–17), use of saline control (12, 13), samples with low suicidal ideation (16, 18) or mixed diagnoses (19), have limited the conclusiveness of results for MDD.

We conducted a randomized clinical trial of an adjunctive infusion of ketamine compared with the short-acting benzodiazepine anesthetic midazolam in MDD with clinically significant suicidal ideation based on SSI score (20). The primary outcome was Day 1 SSI score (24 hours post-infusion). Other outcomes included global depression, clinical ratings during 6-week open follow-up treatment, and safety measures. Due to ketamine’s dissociative effects, there is no ideal comparator, thus like the trial by Murrough et al (21), we used midazolam because it is a psychoactive anesthetic agent with a similar half-life and absence of established antidepressant or anti-suicidal effects. We hypothesized that ketamine would produce a greater reduction in suicidal ideation at Day 1 compared with midazolam.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Patients

Eligible patients were 18 to 65 years old with DSM-IV MDD, HDRS-17 score ≥16 (22) and SSI score ≥4 - considered a clinically significant cutoff (18, 23, 24). A prospective study of 6,891 psychiatric outpatients found that a baseline SSI score >2 predicted suicide during up to 20 years of follow-up, adjusting for other risk factors (23).

Eligibility involved a voluntary admission to an inpatient research unit at New York State Psychiatric Institute (NYSPI), and patients were discharged when assessed as stable and not an imminent safety risk. Exclusions included unstable medical or neurological illness, significant electrocardiographic abnormality, pregnancy or lactation, current psychosis, history of ketamine abuse or dependence, other drug or alcohol dependence within six months, suicidal ideation due to binge substance use or withdrawal, prior ineffective trial of or adverse reaction to ketamine or midazolam, daily opiate use greater than 20 mg oxycodone or equivalent during the three days pre-infusion, score <25 on the Mini Mental State Exam (25) for persons >60 years old, lack of capacity to consent or inadequate understanding of English. There was no exclusion for body mass index or weight. Participants were allowed to continue a stable dose of current psychiatric medications except for benzodiazepines within 24 hours before the infusion. Recruitment was via internet and local media advertising and clinician referral. The protocol was approved by the NYSPI IRB, and written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Intervention

Participants were randomized to intravenous racemic ketamine hydrochloride 0.5 mg/kg or midazolam 0.02 mg/kg in 100 ml normal saline infused over 40 minutes. To minimize additive sedation, we used a lower midazolam dose than the 0.045 mg/kg dose used in studies where participants were washed off concomitant medication (21). In addition to safety concerns, excessive sedation could compromise blinding since sub-anesthetic ketamine does not tend to induce sleep and can be stimulating. Blood pressure, oxygen saturation, heart and respiratory rate were monitored every five minutes during the infusion. A psychiatrist certified in Advanced Cardiac Life Support administered the infusion and an anesthesiologist was available for consultation by phone. After Day 1 assessments, participants received clinical treatment for six months with weekly research ratings for the first six weeks.

Outcome and Measures

Raters were PhD or masters level psychologists. Diagnoses, including alcohol and substance abuse or dependence, were made using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I and II disorders (26, 27) in a weekly consensus conference including research psychologists and psychiatrists. Suicidal ideation due to binge substance abuse was assessed by clinical history, past antidepressant trials and current medications were inventoried with our baseline clinical-demographic form which surveys a range of variables not captured by other instruments. Weekly reliability monitoring used videotaped assessments. Intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC) for key clinical ratings included: (SCID I) ICC=0.94, (HDRS-17) ICC=0.96, (SSI) ICC=0.98.

The clinician-rated SSI (20) assessed current severity of suicidal ideation with 19 items scaled 0 (least severe) to 2 (most severe) and score range 0–38 (20). Items probe wish to die, passive vs. active suicide attempt thoughts, duration and frequency of ideation, sense of control, deterrents, and preparatory behavior for an attempt (23). The SSI has moderately high internal consistency and good concurrent and discriminant validity (28). It was assessed at screening, baseline within 24 hours pre-infusion (SSIBL), 230 minutes post-infusion, 24 hours post-infusion (SSIDay1), and weeks 1–6 of follow-up. For brevity we use “Day 1” to refer to 24 hours postinfusion ratings. Depressive symptoms were assessed with the 17 and 24-item HDRS (22), Beck Depression Inventory (BDI)(29), and Profile of Mood States (POMS) (30). Anxiety was measured with a 5-level Likert scale asking patients to self-rate from 0 (not at all) to 4 (extremely anxious).

Adverse effects were measured with the Systematic Assessment for Treatment Emergent Events-General Inquiry (SAFTEE) (31), Clinician-Administered Dissociative States Scale (CADSS; score range 0–92) (32), and positive symptom subscale of the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRSP: conceptual disorganization, grandiosity, hallucination, and delusions; score range 0–24) (33). Efficacy ratings and the CADSS and BPRSp (baseline, 230 minute, and Day 1) were collected by psychologist raters who were not present during the infusion. The immediate post-infusion CADSS and BPRSp and all SAFTEE ratings were done by the physician who supervised the infusion. Participants were asked at 3 and 6 months about post-study ketamine use.

Randomization and Blinding

A permuted, blocked design with 1:1 assignment between treatments and block size randomized between 4 and 6 with equal probability was used. Randomization was stratified on baseline factors: 1) whether the participant was taking psychiatric medication (yes/no); and 2) SSIBL <8 or ≥8. The latter, based on median SSIBL in our prior clinical trial in suicidal, depressed patients (34), was to increase the likelihood that the treatment groups would be similar in baseline SSI severity.

Patients and study personnel were blind to treatment. To assess blind adequacy, in Day 1 ratings participants and raters answered whether they thought the infusion was midazolam, ketamine, or if they had ‘no idea’. Response was defined as SSIDay1 ≥50% below baseline. We defined ‘remission’ more stringently as SSIDay1 ≥50% below baseline and less than the eligibility threshold of 4. A remission level of improvement was defined to insure that the midazolam group would have every opportunity to receive ketamine. Non-remitters were unblinded and those who had received midazolam were offered an open ketamine infusion, usually the following day. Pre-existing medications were held constant from pre-infusion baseline until completion of Day 1 ratings after the final infusion. Remitters remained blind and received a letter from the pharmacy after completing follow-up treatment informing them of their randomized drug.

Statistical Methods

The study was powered assuming a two-sided test of the group effect at α=0.05 significance level. Effect size estimates, SD’s, and correlations were based on previous reports (15, 34). A planned sample of N=70, assigned 1:1 to each treatment, provided ≥80% power to detect a 25% SSI reduction over 24 hours in the ketamine group and none in the midazolam group. The actual sample is N=80.

Histograms and residual plots of outcomes were inspected for normality. Group comparisons on baseline characteristics were made using Chi-Square tests, or Fisher’s Exact test, as appropriate, for categorical variables, and two sample t-tests for continuous variables. The modified intent-to-treat analysis included all randomized participants who were assessed for the primary outcome, SSIDay1 (N = 80). The primary hypothesis was tested using an ANCOVA model of the change in SSI from baseline to Day 1, with treatment group and SSIBL as the predictors. Randomization stratum (taking psychiatric medication yes/no), by definition not associated with treatment group, was not associated with the primary outcome (p=0.84), and so was not included in the model. Effect size calculations used Cohen’s d and Number Needed to Treat (NNT). Cohen’s d was calculated as the difference in mean group change divided by the standard deviation of baseline values for the whole sample.

Secondary analyses used ANCOVA models to test for differential change between groups in SSI and depressive symptoms (HDRS17 and 24, BDI, POMS) from baseline to 230 minutes and in depressive symptoms from baseline to Day 1. Response was compared by drug using logistic regression. Linear regression was used in an exploratory analysis of treatment effects on the suicidal desire/ideation and planning subscales of the SSI (35). Mediation analyses were performed using a Structural Equation Modeling framework in MPlus, version 7 (36). Paired t-tests were used to determine if the participants assigned to midazolam who received an open ketamine treatment after Day 1 (N = 36) experienced significant subsequent change in SSI or HDRS. For the longitudinal data analysis mixed effects linear regression of SSI and HDRS-17 during the 6-week follow-up ratings tested for significant change from baseline across the entire sample, regardless of treatment group since 35/40 midazolam subjects were non-remitters and received an open ketamine infusion. Safety analyses included univariate tests comparing infusion-related cardio-respiratory effects, SAFTEE events, and post-infusion severity of the BPRSP, dissociative, and anxiety ratings between groups. SAS Version 9.4 (SAS Institute) and SPSS Version 23 (IBM Corp.) were used for all analyses.

Results

Participants

Enrollment was from November 2012 to December 2016 with data collection complete in February 2017. A CONSORT chart (Figure SF1, online data supplement) shows participant flow. Of the 82 participants randomized, one in each group withdrew before Day 1 assessment and was excluded from the analysis. The groups did not differ in baseline characteristics except for frequency of borderline personality disorder (BPD) (Table 1). No participant met SCID criteria for current alcohol or substance abuse; one had alcohol and one cannabis abuse in partial remission (Table SF1). At baseline, participants reported a lifetime medication history of, on average, 4 (SD=2.4) antidepressants, 2 (SD=1.2) antidepressant classes, 45/80 (56%) had previously taken a mood stabilizer, 49/80 (61%) a second generation antipsychotic, 32/80 (40%) a stimulant, 51/80 (64%) a benzodiazepine, 25/80 (31%) other anxiolytics, and 27/80 (34%) sleep medications, and these frequencies did not differ by group (p≥0.1201). Three participants had never taken an antidepressant or other psychiatric drug, and 22 had received prior ECT. Frequencies of current medication classes at baseline were: antidepressants (43/80); anticonvulsants (21/80); antipsychotics (14/80); benzodiazepines (27/80; stopped at least 24 hours pre-infusion); and lithium (2/80) (Table SF2), and these did not differ by treatment group (p≥0.2422).

TABLE 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Patients with Major Depressive Disorder and Clinically Significant Suicidal Ideation Given a Single Infusion of Ketamine or Midazolama

| Midazolam (N=40) |

Ketamine (N=40) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variableb | N | % | N | % | χ2 | df | p |

| Female sex | 26 | 65 | 22 | 55 | 0.83 | 1 | 0.36 |

| White race | 39 | 97.5 | 35 | 87.5 | 0.20h | ||

| Hispanic ethnicity | 1 | 2.5 | 0 | 0 | 1.0h | ||

| Married | 7 | 18 | 7 | 18 | 0.00 | 1 | 0.96 |

| Currently employed | 15 | 37.5 | 10 | 25 | 1.46 | 1 | 0.23 |

| Prior psychiatric hospitalization | 29 | 73 | 27 | 68 | 0.24 | 1 | 0.63 |

| Prior suicide attemptc | 22 | 55 | 17 | 42.5 | 1.25 | 1 | 0.26 |

| Personality disorderd | 13 | 36 | 16 | 41 | 0.19 | 1 | 0.66 |

| Borderline personality disorderd | 3 | 8 | 11 | 28 | 4.87 | 1 | 0.03 |

| Alcohol or substance use disorder history | 9 | 22.5 | 11 | 27.5 | 0.27 | 1 | 0.61 |

| Mood disorder in first degree relative | 23 | 57.5 | 24 | 60.0 | 0.052 | 1 | 0.82 |

| Suicide or attempt in first degree relative | 3 | 7.5 | 2 | 5.0 | 1.0h | ||

| Variable | N | Mean ± SD | N | Mean ± SD | t | df | p |

| Age | 40 | 40.7 ±13.1 | 40 | 38.4 ±13.2 | 0.77 | 78 | 0.44 |

| Scale for Suicidal Ideatione | 40 | 15.7 ±6.9 | 40 | 14.3 ±6.3 | 0.94 | 78 | 0.35 |

| Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (17 item)f | 40 | 22.6 ±3.9 | 40 | 22.2 ±4.6 | 0.41 | 78 | 0.68 |

| Beck Depression Inventoryg | 38 | 33.9 ±8.1 | 36 | 31.8 ±8.1 | 1.13 | 72 | 0.26 |

| Total years of education | 39 | 15.9 ±2.4 | 40 | 15.9 ±2.8 | 0.04 | 77 | 0.97 |

| Variable | Median (range) | Median (range) | Ui | p | |||

| Length of current episode (weeks) | 37 | 50 (2–2860) | 36 | 60 (8–572) | 652.0 | 0.88 | |

| Age of onset of first major depressive episode (years) | 39 | 14 (5–45) | 37 | 16 (6–51) | 744.5 | 0.81 | |

| Lifetime number of major depressive episodes including current | 35 | 3 (1-too many to count) | 36 | 4.5 (1-too many to count) | 716.5 | 0.31 | |

| Body mass index | 40 | 27.8 (17.2–51.5) | 40 | 25.3 (19.9–46.7) | 708.0 | 0.38 | |

Modified intention-to-treat sample.

Assessed with our research Baseline Clinical-Demographic form unless otherwise noted.

Columbia Suicide History Interview (48).

SCID for DSM-IV Axis II disorders (27).

Score ranges from 0 to 38, with higher scores indicating greater symptom severity.

Score ranges from 0 to 53, with higher scores indicating greater symptom severity.

Score ranges from 0 to 63, with higher scores indicating greater symptom severity.

Fisher’s Exact Test

Mann-Whitney U

Primary Outcome: Day 1 suicidal ideation

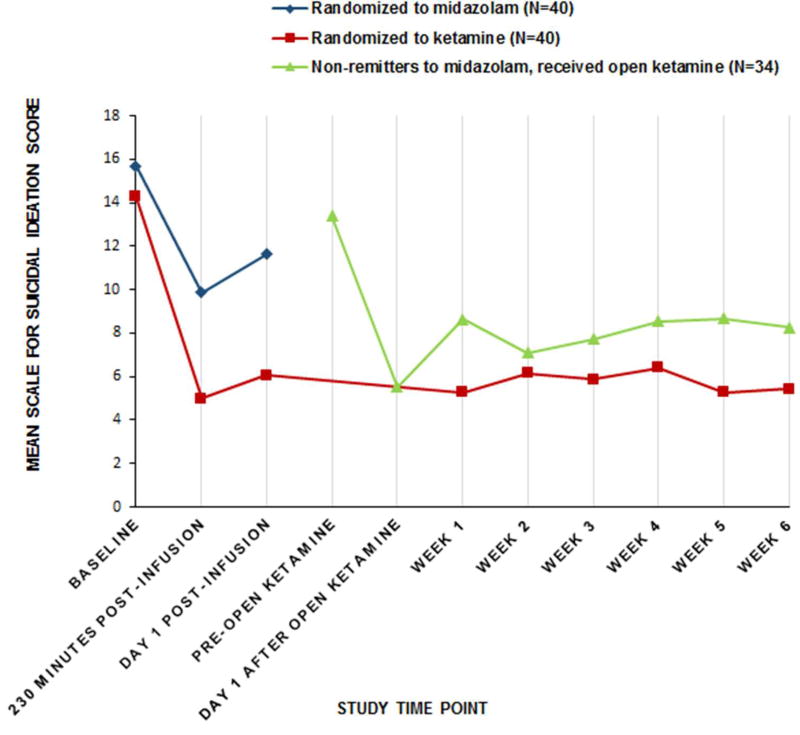

Average SSI score at Day 1 was 4.96 points lower after ketamine compared with midazolam (Estimate=4.96 (95% CI 2.33 to 7.59), t=3.75, df=77, p=0.0003) (Figure 1). Cohen’s d for the difference in mean group change was 0.75, a medium effect size. Including baseline BPD diagnosis as a covariate had little effect on the results (Estimate=4.76 (95% CI=1.89 to 7.63), t=3.30, df=71, p=0.0015).

FIGURE 1. Change in Suicidal Ideationa Over Time in Suicidal Patients with Major Depression Randomized to a Sub-anesthetic Infusion of Ketamine or Midazolamb,c.

aScale for Suicidal Ideation (SSI) scores range 0 to 38, higher scores indicating greater severity.

bModified intent-to-treat sample (N=40 per group). Ketamine 0.5 mg/kg or midazolam 0.02 mg/kg in 100 ml normal saline infused over 40 minutes, adjunctive to current, nonbenzodiazepine medications. Remission defined as Day 1 post-infusion SSI score ≥50% below baseline and less than study eligibility threshold of 4. For non-remitters, the blind was broken and those allocated to midazolam were offered an open ketamine infusion usually the following day: N=35 midazolam non-remitters received an open ketamine infusion and 1 withdrew before Day 1 assessment.

cReduction in SSI from baseline to 24 hours after the randomized infusion (Day1 Post-infusion) was the primary outcome and was greater for the ketamine group than for the midazolam group (p=0.0003).

Secondary Outcomes

Suicidal Ideation

The proportion of responders on the SSI at Day 1 was 55% after ketamine and 30% after midazolam (OR=2.85 (95% CI=1.14 to 7.15); p=0.0237; NNT=4.00). Decrease in suicidal ideation at 230 minutes after the randomized infusion was greater after ketamine (mean reduction=9.69 points) compared with midazolam (mean reduction=5.41 points); differential drug effect estimate=4.29 points (95% CI=1.73 to 6.84; t=3.34, df=77, p=0.0013). Exploratory analysis showed a trend toward the ketamine group having 2.8-fold greater odds of zero SSI score at Day 1 (p=0.0879). Among those with suicidal ideation on Day 1, we found no differential drug effect on the SSI planning subscale, but greater improvement in the ketamine group in the “suicidal desire and ideation” subscale (35) (estimate=1.37, df=58, t=2.02, p=0.0485).

Post-infusion worsening of SSI occurred in 4 midazolam subjects at 230 minutes, and at Day 1 in 9 midazolam and 2 ketamine subjects.

Depressive symptoms

Day 1 POMS total mood disturbance score showed greater improvement after ketamine compared with midazolam (Estimate=21.19 (95% CI=2.95 to 39.43), df=75, t=2.31, p=0.0234) as did depression (Estimate=7.65 (95% CI=1.36 to 13.94), df=75, t=2.42, p=0.0178) and fatigue subscale scores (Estimate=4.12 (95% CI=0.73 to 7.50), df=75, t=2.42, p=0.0178). There was partial mediation (33.6%) of ketamine’s effect on SSIDay1 through its effect on POMS depression (indirect path Estimate=−1.62, SE=0.81, p=0.0498; direct path Estimate=−3.20, SE=1.12, p=0.0054).

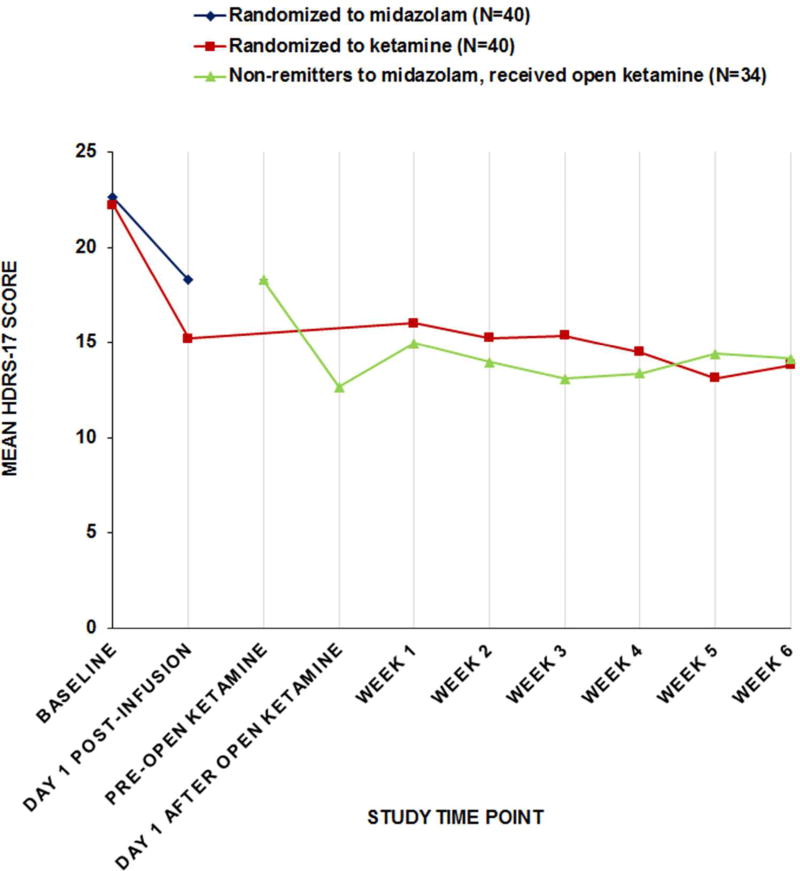

There were trend-level advantages for ketamine on the Day 1 clinician-rated HDRS-17 (Estimate=2.83 points (95% CI=−0.12 to 5.77), t=1.91, df=77, p=0.0600), HDRS-24 (Estimate=3.54 points (95% CI=−0.29 to 7.36), t=1.84, df=77, p=0.0694), and self-rated BDI (Estimate=4.66 points (95% CI=−0.04 to 9.36), t=1.98, df=69, p=0.0519). Proportion of responders in the ketamine and midazolam groups, respectively, were: HDRS-17 (30% vs. 15%: OR=2.43 (95% CI=0.81 to 7.30), NNT=6.67, p=0.1082); HDRS 24 (25% vs. 15%: OR=1.89 (95% CI=0.61 to 5.82), NNT=10.00, p=0.2636); BDI (36% vs. 17%: OR=2.83 (95% CI=0.93 to 8.57), NNT=5.14, p=0.0612).

Open ketamine infusion

In the midazolam group, 35 participants did not meet the SSI remission criteria and received an open ketamine infusion (Figure 1). Day 1 ratings showed improvement from postmidazolam scores as follows: SSI (Estimate=−7.85 (SD 6.58), df=33, t=−6.96, p<0.0001); HDRS-17 (Estimate=−7.26 (SD 6.93), df=33, t=−6.11, p<0.0001); and HDRS-24 (Estimate=−9.85 (SD 9.43), df=33, t=−6.09, p<0.0001).

Weeks 1–6 Follow-Up Ratings

Longitudinal analysis showed that clinical improvement after randomized and open ketamine treatment was generally maintained through six-week open, clinical follow-up treatment with respect to SSI, and depression (Figures 1 and 2; Tables SF3 and 4).

FIGURE 2. Change in 17-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale Scorea Over Time in Suicidal Patients with Major Depression Randomized to a Sub-anesthetic Infusion of Ketamine or Midazolamb,c.

aHDRS-17 scores range 0 to 53, higher scores indicating greater severity.

bModified intent-to-treat sample (N=40 per group). Ketamine 0.5 mg/kg or midazolam 0.02 mg/kg in 100 ml normal saline infused over 40 minutes, adjunctive to current, non-benzodiazepine medications. Remission defined as Day 1 post-infusion SSI score ≥50% below baseline and less than study eligibility threshold of 4. For non-remitters, the blind was broken and those allocated to midazolam were offered an open ketamine infusion usually the following day: N=35 midazolam non-remitters received an open ketamine infusion and 1 withdrew before Day 1 assessment.

cHDRS-17 at 24 hours after the randomized infusion (Day1 Post-infusion) was a secondary outcome and there was a trend toward greater reduction in the ketamine group compared to the midazolam group (p=0.0600).

Blinding

On Day 1, raters correctly guessed the blinded drug in 42% of midazolam and 44% of ketamine cases (χ2=0.02, df=1, p=0.8950). Patients guessed correctly 55% of the time with both drugs (χ2=0.00, df=1, p=1.000).

Safety Outcomes

Cardio-Respiratory Effects

Ketamine was associated with a mean transient increase in SBP of 15.28 (SD=9.79) mm Hg compared with 3.75 (SD=6.46) mm Hg for midazolam (t=−6.22, df=78, p<0.0001)(Table SF1, online data supplement). A mean increase in DBP of 13.38 (SD=8.48) mm Hg was observed with ketamine versus 4.03 (SD=5.50) mm Hg with midazolam (t=−5.85, df=78, p<0.0001). It took a mean of 5.28 minutes for blood pressure to return to baseline after ketamine, and zero minutes after midazolam. Cardio-respiratory effects are summarized in Table SF5.

Psychiatric and other adverse effects

Baseline dissociative and BPRSP symptoms did not differ between groups (p>0.7). CADSS scores were higher immediately after ketamine (Mean=17.63, SD=13.55) than after midazolam (Mean=0.88, SD=1.42; U=1,475.50, p<0.0001), but the groups did not differ at 230 minutes (p=0.8190) or Day 1 (p=0.8256)(Figure SF2). BPRSP scores were higher immediately postketamine (Mean=0.68, SD=1.80) with no score>0 after midazolam (U=980.00, p=0.0016), and no group differences at 230 minutes (p=0.3173) or Day 1 (p=0.6338).

Participants reported higher anxiety 230 minutes after midazolam (Mean=2.10, SD=1.34) than after ketamine (Mean=1.40, SD=1.13) (Estimate=2.68 (95% CI=1.15 to 6.23), p=0.0228), but there was no difference on Day 1 (p=0.4968). Mostly physical adverse effects, assessed with the SAFTEE, are summarized in Table SF6 (online data supplement).

At follow-up assessment for ketamine abuse: N=68 (85%) were reached at 3 months and N=62 (78%) at 6 months. None showed evidence of abuse, 5 (6%) reported receiving ketamine off-label in private clinics, and one had contemplated using some given by a friend.

Serious Adverse Events

There were 10 serious adverse events (SAE requiring IRB report): 2 for unrelated medical illness, 1 sedative misuse without suicidal intent, 4 suicide attempts (3 after and 1 before study procedures), and 3 inpatient admissions for increased suicidal ideation. No SAE resulted in serious medical sequelae or IRB-required protocol modification. Details are provided in Table SF7 (online data supplement). No suicides occurred during the protocol. Two suicides occurred after the study at 6 and 26 months post-infusion during treatment in the community by, respectively, a ketamine remitter and a non-responder.

Discussion

In MDD with clinically significant suicidal ideation, a single sub-anesthetic ketamine infusion, adjunctive to ongoing pharmacotherapy, was associated with greater reduction in suicidal thoughts at Day 1, the primary outcome, compared to midazolam control. The adjusted mean difference of 4.96 points on the clinician-rated SSI, Cohen’s d of 0.75, and NNT of 4 for response represent a medium size effect. Adverse effects – mainly blood pressure increase and dissociative symptoms – were similar to other studies (37), mostly mild to moderate, and transient, typically resolving within minutes to hours after infusion. Improvement in suicidal ideation was maintained during the 6-week clinical treatment follow-up ratings.

To our knowledge, there is no number of points on a standard suicidal ideation scale established as a clinically meaningful reduction. A prospective study (N=6,891) of patients with depressive disorders found that a baseline SSI>2 predicted suicide during up to 20 years of follow-up (23). In another prospective study of 562 inpatients (64% with a mood disorder) who endorsed suicidal thoughts, those who experienced a 50% reduction within 24 hours from a severe level (suicidal ideation “most of the time”) had one-third the risk of subsequent self-harm events during a mean length of stay of 24 days compared to those whose suicidal thoughts remained elevated (38). Trials during recent decades show the average advantage for antidepressant drug vs. placebo was 2 to 4 points on measures such as the HDRS-17 (39). The United Kingdom’s National Institute for Health and Care Excellence considers a standardized mean difference, such as Cohen’s d of ≥0.5, or a between group difference of ≥3 points on the HDRS or BDI, to be clinically significant (40). Together these data suggest that the advantage for reduction of suicidal ideation 24 hours after ketamine, compared to midazolam, found in this study is clinically meaningful.

Given concerns about ketamine’s one to two-week antidepressant effect in prior studies (11), it is notable that the improvement in suicidal ideation in this trial was largely maintained through the 6-week follow-up ratings. This may be partly explained by the fact that patients continued prior psychotropic medication, which was optimized after completion of Day 1 post-infusion ratings. Our result is consistent with the Hu et al trial in which MDD patients randomized to a single ketamine infusion on Day 1 of escitalopram therapy experienced faster response compared to saline control and benefits were maintained for four weeks (41).

We found greater reductions in overall mood disturbance, depression and fatigue, assessed with the POMS, on Day 1 after ketamine compared with midazolam. The response rates we found for depression using the HDRS and BDI were surprisingly low compared to other randomized controlled ketamine trials (42). Contributing factors may include: concurrent antidepressant and other psychiatric medications, the effect of hopelessness as a feature of suicidal states, the possibility that our non-treatment resistant sample may have been more prone to midazolam placebo response.

The fact that the differential drug effect on global mood and depression was strongest for the POMS and BDI may partly relate to their emphasis on subjective experience of core depressive symptoms which correlate more strongly with suicidal ideation than do other symptom types (43). A secondary analysis of adjunctive ketamine (N=14) found reduction of suicidal ideation even when depression did not remit (17). Ketamine is mechanistically distinct from currently approved antidepressants, its therapeutic effects possibly involving rapid synapse formation (44). Our mediation model results suggest its effects on depression and suicidal thoughts are at least partially independent.

The only other midazolam-controlled trial of adjunctive ketamine infusion with primary outcome of SSI at Day 1 was in mood and anxiety disorders (N=24) with score ≥4 on the Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale suicide item (MADRS-SI) (19). Differences from our trial included mixed diagnoses, inpatient and outpatient settings, higher (0.045 mg/kg) midazolam dose, and self-report SSI (19) which correlates >0.90 with the clinician-rated version that we used although patients report higher scores than clinicians (45). Results did not show a differential treatment effect on the primary outcome but a difference favoring ketamine was found at 24 hours on the MADRS-SI and at 48 hours on the SSI, which was no longer significant at 72 hours (19). The study did not find a differential effect on global depression nor correlations between changes in SSI and total MADRS scores (19).

A midazolam-controlled ketamine trial in treatment resistant depression (N=73) found an 8-point advantage for ketamine on the primary outcome MADRS at Day 1 (Cohen’s d=0.81; OR for response=2.2) (21). Subsequent analysis reported an advantage at Day 1 for ketamine in reduction of a suicidal index comprised of the self-report SSI (mean baseline score=6) and suicide items from two depression scales, which was fully mediated by reduction in MADRS score minus the suicide item (18).

We found stronger effects on suicidal ideation than on global depression compared to the latter trial (21), although both studies involved patients with moderate to severe baseline depression severity according to MADRS and HDRS guidelines (46). Reasons may include study design whereby we allowed patients to stay on their current stable dose of antidepressants instead of washing subjects off medication so they were drug-free for a week before the trial began. 54% of our sample was taking antidepressant medication at baseline. Residual antidepressant effects from the concomitant medication in both treatment groups in our study may have diminished the antidepressant effect of ketamine. Another study difference was in the samples where they included treatment resistant depression and we included clinically significant suicidal ideation.

Limitations of our study include the primary outcome of suicidal ideation as opposed to behavior. Suicide or attempts are more significant, but their low base rates, even in at-risk populations, mean that very large samples and long follow-up are required. Suicidal ideation is feasible and significant as clinicians assess it when evaluating need for hospitalization because it predicts suicide attempts (47) and suicide (23). Among those with suicidal ideation on Day 1, there was no differential drug effect on the SSI planning subscale, but greater improvement in the ketamine group in the “suicidal desire and ideation” subscale, which correlated with depression, hopelessness and past suicide attempt in a study by Witte et al (35).

There were more patients with BPD in the ketamine group. While there is no reason to think this would affect study infusion response in a particular direction, when it was included as a covariate it had little effect on the primary outcome. The higher rate of dissociative side effects with ketamine, found in other studies, makes midazolam an imperfect control (21), but the rate of correct guesses on the blinded infusion drug was not statistically significant among raters or participants. Other limitations include open label data during Week 1–6 follow-up ratings and the small percentages of Hispanic and non-white participants.

In this randomized trial in suicidal depressed patients, a single, adjunctive, subanesthetic ketamine infusion was associated with clinically significant reduction in suicidal ideation at Day 1, greater than midazolam control. This improvement persists for at least 6 weeks. The clinical applicability of our findings was improved with infusion administration by a psychiatrist and without a medication washout as in some studies (12, 13, 21). Research is needed to understand ketamine’s mechanism of action and to investigate strategies and safety of longer-term treatment.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Supported by NIMH grant R01 MH-096784 to Dr. Grunebaum. The authors thank S. Ellis, B. Stanley, G. Blinn, A. Frawley, the NYSPI 5-South unit staff, and Manny De La Nuez for their contributions, and all of the participants who volunteered their time and trust. ClinicalTrials.gov identifier, NCT01700829.

Drs. Mann, Burke and Oquendo receive royalties from the Research Foundation for Mental Hygiene for commercial use of the Columbia Suicide Severity Rating Scale, which was not used in this study. Dr. Oquendo’s family owns stock in Bristol Myers Squibb.

Footnotes

Disclosures: The other authors have no conflicts of interest related to this study.

References

- 1.Fatal Injury Reports, National, Regional and State, 1981 – 2015. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; [Accessed 05/24/2017]. URL: https://webappa.cdc.gov/sasweb/ncipc/mortrate.html. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jacobs DG, Baldessarini RJ, Conwell Y, Fawcett JA, Horton L, Meltzer H, Pfeffer CR, Simon RI. Practice Guideline for the Assessment and Treatment of Patients with Suicidal Behaviors. American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc.; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gibbons RD, Brown CH, Hur K, Davis JM, Mann JJ. Suicidal thoughts and behavior with antidepressant treatment: reanalysis of the randomized placebo-controlled studies of fluoxetine and venlafaxine. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2012 doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.2048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Meltzer HY, Alphs L, Green AI, Altamura AC, Anand R, Bertoldi A, Bourgeois M, Chouinard G, Islam MZ, Kane J, Krishnan R, Lindenmayer JP, Potkin S International Suicide Prevention Trial Study G. Clozapine treatment for suicidality in schizophrenia: International Suicide Prevention Trial (InterSePT) Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60:82–91. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.1.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Prudic J, Sackeim HA. Electroconvulsive therapy and suicide risk. J Clin Psychiatry. 1999;60(Suppl 2):104–110. discussion 111–106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cipriani A, Hawton K, Stockton S, Geddes JR. Lithium in the prevention of suicide in mood disorders: updated systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2013;346:f3646. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f3646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Trivedi MH, Rush AJ, Wisniewski SR, Nierenberg AA, Warden D, Ritz L, Norquist G, Howland R, Lebowitz B, McGrath PJ, Shores-Wilson K, Biggs JT, Balsubramani GK, Fava M, Team SDS. Evaluation of outcomes with citalopram for depression using measurement-based care in STAR*D: implications for clinical practice. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:28–40. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.163.1.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mann JJ, Apter A, Bertolote J, Beautrais A, Currier D, Haas A, Hegerl U, Lonnqvist J, Malone KM, Marusic A, Mehlum L, Patton G, Phillips M, Rutz W, Rihmer Z, Schmidtke A, Shaffer D, Silverman M, Takahashi Y, Varnik A, Wasserman D, Yip P, Hendin H. Suicide prevention strategies: a systematic review. JAMA. 2005;294:2064–2074. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.16.2064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zimmerman M, Mattia JI, Posternak MA. Are subjects in pharmacological treatment trials of depression representative of patients in routine clinical practice? Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159:469–473. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.3.469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nock MK, Hwang I, Sampson NA, Kessler RC. Mental disorders, comorbidity and suicidal behavior: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Molecular Psychiatry. 2009:1–9. doi: 10.1038/mp.2009.29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Newport DJ, Carpenter LL, McDonald WM, Potash JB, Tohen M, Nemeroff CB. Ketamine and Other NMDA Antagonists: Early Clinical Trials and Possible Mechanisms in Depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2015;172:950–966. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2015.15040465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Berman RM, Cappiello A, Anand A, Oren DA, Heninger GR, Charney DS, Krystal JH. Antidepressant effects of ketamine in depressed patients. Biol Psychiatry. 2000;47:351–354. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(99)00230-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zarate CA, Jr, Singh JB, Carlson PJ, Brutsche NE, Ameli R, Luckenbaugh DA, Charney DS, Manji HK. A Randomized Trial of an N-methyl-D-aspartate Antagonist in Treatment- Resistant Major Depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63:856–864. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.8.856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kudoh A, Takahira Y, Katagai H, Takazawa T. Small-dose ketamine improves the postoperative state of depressed patients. Anesth Analg. 2002;95:114–118. doi: 10.1097/00000539-200207000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Price RB, Nock MK, Charney DS, Mathew SJ. Effects of intravenous ketamine on explicit and implicit measures of suicidality in treatment-resistant depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2009;66:522–526. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.04.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.DiazGranados N, Ibrahim LA, Brutsche NE, Ameli R, Henter ID, Luckenbaugh DA, Machado-Vieira R, Zarate CA. Rapid resolution of suicidal ideation after a single infusion of an N-methyl-D-aspartate antagonist in patients with treatment-resistant major depressive disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;71:1605–1611. doi: 10.4088/JCP.09m05327blu. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ionescu DF, Swee MB, Pavone KJ, Taylor N, Akeju O, Baer L, Nyer M, Cassano P, Mischoulon D, Alpert JE, Brown EN, Nock MK, Fava M, Cusin C. Rapid and Sustained Reductions in Current Suicidal Ideation Following Repeated Doses of Intravenous Ketamine: Secondary Analysis of an Open-Label Study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2016;77:e719–725. doi: 10.4088/JCP.15m10056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Price RB, Iosifescu DV, Murrough JW, Chang LC, Al Jurdi RK, Iqbal SZ, Soleimani L, Charney DS, Foulkes AL, Mathew SJ. Effects of ketamine on explicit and implicit suicidal cognition: a randomized controlled trial in treatment-resistant depression. Depress Anxiety. 2014;31:335–343. doi: 10.1002/da.22253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Murrough JW, Soleimani L, DeWilde KE, Collins KA, Lapidus KA, Iacoviello BM, Lener M, Kautz M, Kim J, Stern JB, Price RB, Perez AM, Brallier JW, Rodriguez GJ, Goodman WK, Iosifescu DV, Charney DS. Ketamine for rapid reduction of suicidal ideation: a randomized controlled trial. Psychol Med. 2015;45:3571–3580. doi: 10.1017/S0033291715001506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Beck AT, Kovacs M, Weissman A. Assessment of suicidal intention: The scale for suicide ideation. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1979;47:343–352. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.47.2.343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Murrough JW, Iosifescu DV, Chang LC, Al Jurdi RK, Green CE, Perez AM, Iqbal S, Pillemer S, Foulkes A, Shah A, Charney DS, Mathew SJ. Antidepressant efficacy of ketamine in treatment-resistant major depression: a two-site randomized controlled trial. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170:1134–1142. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2013.13030392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hamilton M. A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1960;23:56–62. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.23.1.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brown GKBAT, Steer RA, Grisham JR. Risk factors for suicide in psychiatric outpatients. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2000;68:371–377. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Holi MM, Pelkonen M, Karlsson L, Kiviruusu O, Ruuttu T, Hannele H, Tuisku V, Marttunen M. Psychometric properties and clinical utility of the Scale for Suicidal Ideation (SSI) in adolescents. BMC Psychiatry. 2005 Feb 3; doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-5-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. "Mini-mental state". A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12:189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (SCID) New York State Psychiatric Institute, Biometrics Research; New York, NY: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 27.First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JMG, Benjamin L. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis II Personality Disorders (SCID-II), (Version 2.0) New York: Biometrics Research Department, New York State Psychiatric Institute; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Beck AT, Brown GK, Steer RA. Psychometric characteristics of the Scale for Suicide Ideation with psychiatric outpatients. Behav Res Ther. 1997;35:1039–1046. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(97)00073-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelson M, Mock J, Erbaugh J. An inventory for measuring depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1961;4:53–63. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1961.01710120031004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McNair DM, Lorr M, Droppleman LF. Manual for the Profile of Mood States. San Diego: Educational and Industrial Testing Service; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Levine J, Schooler NR. SAFTEE: a technique for the systematic assessment of side effects in clinical trials. Psychopharmacol Bull. 1986;22:343–381. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bremner JD, Krystal JH, Putnam FW, Southwick SM, Marmar C, Charney DS, Mazure CM. Measurement of dissociative states with the Clinician-Administered Dissociative States Scale (CADSS) Journal of Traumatic Stress. 1998;11:125–136. doi: 10.1023/A:1024465317902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Overall JE, Gorham DR. The brief psychiatric rating scale. Psychological Reports. 1962;10:799–812. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Grunebaum MF, Ellis SP, Duan N, Burke AK, Oquendo MA, Mann JJ. Pilot randomized clinical trial of an SSRI vs bupropion: effects on suicidal behavior, ideation, and mood in major depression. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2012;37:697–706. doi: 10.1038/npp.2011.247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Witte TK, Joiner TE, Jr, Brown GK, Beck AT, Beckman A, Duberstein P, Conwell Y. Factors of suicide ideation and their relation to clinical and other indicators in older adults. J Affect Disord. 2006;94:165–172. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2006.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Muthen L, Muthen B. Mplus Version 7 User's Guide: Version 7. Los Angeles, CA: Muthen & Muthen; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sanacora G, Frye MA, McDonald W, Mathew SJ, Turner MS, Schatzberg AF, Summergrad P, Nemeroff CB American Psychiatric Association Council of Research Task Force on Novel B, Treatments. A Consensus Statement on the Use of Ketamine in the Treatment of Mood Disorders. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017 doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.0080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Restifo E, Kashyap S, Hooke GR, Page AC. Daily monitoring of temporal trajectories of suicidal ideation predict self-injury: A novel application of patient progress monitoring. Psychother Res. 2015;25:705–713. doi: 10.1080/10503307.2015.1006707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Thase ME. The small specific effects of antidepressants in clinical trials: what do they mean to psychiatrists? Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2011;13:476–482. doi: 10.1007/s11920-011-0235-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Clinical guideline. UK: 2009. Excellence NIfHaC: Depression in adults: recognition and management. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hu YD, Xiang YT, Fang JX, Zu S, Sha S, Shi H, Ungvari GS, Correll CU, Chiu HF, Xue Y, Tian TF, Wu AS, Ma X, Wang G. Single i.v. ketamine augmentation of newly initiated escitalopram for major depression: results from a randomized, placebo-controlled 4-week study. Psychol Med. 2016;46:623–635. doi: 10.1017/S0033291715002159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Murrough JW, Abdallah CG, Mathew SJ. Targeting glutamate signalling in depression: progress and prospects. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2017 doi: 10.1038/nrd.2017.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Keilp JG, Grunebaum MF, Gorlyn M, LeBlanc S, Burke AK, Galfalvy H, Oquendo MA, Mann JJ. Suicidal ideation and the subjective aspects of depression. J Affect Disord. 2012;140:75–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2012.01.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Duman RS, Aghajanian GK, Sanacora G, Krystal JH. Synaptic plasticity and depression: new insights from stress and rapid-acting antidepressants. Nat Med. 2016;22:238–249. doi: 10.1038/nm.4050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Beck AT, Steer RA, Ranieri WF. Scale for suicide ideation: Psychometric properties of a self-report version. J Clin Psychol. 1988;44:499–505. doi: 10.1002/1097-4679(198807)44:4<499::aid-jclp2270440404>3.0.co;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Carmody TJ, Rush AJ, Bernstein I, Warden D, Brannan S, Burnham D, Woo A, Trivedi MH. The Montgomery Asberg and the Hamilton ratings of depression: a comparison of measures. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2006;16:601–611. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2006.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Oquendo MA, Galfalvy HC, Russo S, Ellis SP, Grunebaum MF, Burke AK, Mann JJ. Prospective Study of Clinical Predictors of Suicidal Acts After a Major Depressive Episode in Patients With Major Depressive Disorder or Bipolar Disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2004:1433–1441. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.8.1433. In Press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Oquendo MA, Halberstam B, Mann JJ. Risk Factors for Suicidal Behavior: utility and limitations of research instruments. In: First MB, editor. Standardized Evaluation in Clinical Practice. Washington, D.C: APPI Press; 2003. pp. 103–130. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.