Abstract

Background & Aims

Despite the availability of endoscopic therapy, many patients in the United States undergo surgical resection for non-malignant colorectal polyps. We aimed to quantify and examine trends in the use of surgery for non-malignant colorectal polyps in a nationally representative sample.

Methods

We analyzed data from the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project National Inpatient Sample for the years 2000 through 2014. We included all adult patients who underwent elective colectomy or proctectomy and had a diagnosis of either non-malignant colorectal polyp or colorectal cancer. We compared trends in surgery for non-malignant colorectal polyps with surgery for colorectal cancer and calculated age, sex, race, region, and teaching status/bed-size specific incidence rates of surgery for non-malignant colorectal polyps.

Results

From 2000 through 2014, there were 1,230,458 surgeries for non-malignant colorectal polyps and colorectal cancer in the United States. Among those surgeries, 25% were performed for non-malignant colorectal polyps. The incidence of surgery for non-malignant colorectal polyps has increased significantly, from 5.9 in 2000 to 9.4 in 2014 per 100,000 adults (incidence rate difference, 3.56; 95% CI 3.40–3.72), while the incidence of surgery for colorectal cancer has significantly decreased, from 31.5 to 24.7 surgeries per 100,000 adults (incidence rate difference, −6.80; 95% CI, −7.11 to −6.49). The incidence of surgery for non-malignant colorectal polyps has been increasing among individuals 20–79, in men and women and including all races and ethnicities.

Conclusions

In an analysis of a large, nationally representative sample, we found that surgery for non-malignant colorectal polyps is common and has significantly increased over the last 14 years.

Keywords: colonic polyps, adenomatous polyps, intestinal polyps, colectomy

Introduction

An estimated 6.3 million screening colonoscopies are performed annually in the United States.1 Among patients undergoing an average-risk screening colonoscopy, 4–11% will be found to have a large colorectal polyp.2 Traditionally, many of these more complex colorectal polyps were managed surgically with a partial colectomy. With advances in endoscopic mucosal resection, this practice should be changing. Compared with surgical resection, endoscopic resection is associated with a reduced risk of adverse events3–5 and is more cost effective.6, 7 Prior to consideration of surgical resection, guidelines now recommend referral to an advanced endoscopist for repeat colonoscopy and if appropriate, attempted endoscopic resection.8–10

Despite strong evidence favoring endoscopic resection, partial colectomies for non-malignant colorectal polyps continue to be performed frequently in the United States.11 Elective colectomy is often complicated by adverse events, and more so in older adults who are disproportionally affected with non-malignant colorectal polyps.3, 11 One in seven patients who have surgery for a non-malignant colorectal polyp will have at least one major post-operative event.3 The most common adverse events within 30-days are readmission (8%), reoperation (4%) and anastomotic leak or abscess (3%).3 While surgery for the management of non-malignant colorectal polyps is commonly utilized in the United States, national incidence rates and trends for this surgery have not been published.

Understanding volume and trends in surgery for non-malignant colorectal polyps in the United States can increase awareness of how non-malignant colorectal polyps are managed and better identify barriers to endoscopic management. To this end, we examined trends in surgery for non-malignant colorectal polyps stratified by patient characteristics and hospital-level factors in a nationally representative sample. To put these trends into context, we compared this data to data on surgery for colorectal cancer from the same national sample.

Methods

Study Design and Population

We used the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project National Inpatient Sample (NIS) for the years 2000–2014 to obtain incidence estimates for surgery for non-malignant colorectal polyps and colorectal cancer. The NIS is the largest publicly available all-payer inpatient health care database in the United States, yielding national estimates of hospital inpatient stays. Unweighted, it contains data from more than 7 million hospital stays, at over 1,000 hospitals, each year. Prior to 2012, the NIS performed a stratified random sample of 20% of participating hospitals, with all discharge records from selected facilities included. In 2012, the NIS redesigned the sampling strategy to a stratified random sample of all discharge records. The NIS contains information on patients, regardless of payer, including individuals covered by Medicare, Medicaid, or private insurance, and those who are uninsured.

All patients ≥20 years old, who had diagnoses for either benign neoplasms of the colon, rectum, or anal canal (International Classification of Disease, Ninth edition (ICD-9) codes: 211.3 or 211.4) or colorectal cancer (ICD −9 codes: 153 – 154.8, 230.3, or 230.4), and underwent elective colectomy or proctectomy (ICD −9 procedure codes: 17.3 – 17.39, 45.7 – 45.79, or 48.4 – 48.59) were eligible for inclusion. Patients with diagnoses for both benign neoplasms and colorectal cancer were classified as having colorectal cancer. We excluded patients classified as having benign neoplasms and intestinal perforation (ICD-9 code 569.83), all patients diagnosed with inflammatory bowel disease (555 – 555.9 and 556 – 556.9) and all patients who underwent total colectomy (45.8 – 45.83) (Supplemental Figure 1). To assess whether the polyps might be an incidental finding, we excluded all patients diagnosed with diverticulitis (ICD-9 code 562.11) in a sensitivity analysis. For the sake of clarity, benign neoplasms of the colon and rectum are referred to as non-malignant colorectal polyps throughout the manuscript. Discharge weights were applied to estimate the national incidence for surgery for non-malignant colorectal polyps and colorectal cancer. The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Office of Human Research Ethics determined this study to be exempt from continuing review given use of deidentified data.

Statistical Analysis

Patient demographics and hospital characteristics, stratified by patient diagnosis (non-malignant colorectal polyp versus colorectal cancer), were described using descriptive statistics. The yearly incidence of surgery for non-malignant colorectal polyps and colorectal cancer, respectively, was calculated using Poisson regression, and expressed as the number of procedures per 100,000 US adults. The number of US adults was obtained using available 2010 US Census data. Additionally, age, sex, race/ethnicity, and region stratified rates of surgery for non-malignant colorectal polyps per 100,000 US adults were also calculated using Poisson regression. Age was categorized as 20 – 49 years old, 50 – 64 years old, 65 – 79 years old, and ≥80 years old. The rates of surgery for non-malignant colorectal polyps across teaching status/location and bed size were assessed among all US adults. A hospital is considered to be a teaching hospital if it has an American Medical Association approved residency program, is a member of the Council of Teaching Hospitals or has a ratio of full-time equivalent interns and residents to beds of .25 or higher. Incidence rate differences (IRDs) comparing the rates in 2014 to 2000 were also calculated and were expressed as rates per 100,000 adults. Significant change in the rate of surgery for non-malignant colorectal polyps between 2000 and 2014 was assessed using a likelihood ratio test. All analyses were performed using SAS 9.4 (SAS Inc., Cary, North Carolina).

Results

In the United States, there were an estimated 1,230,458 surgeries for either non-malignant colorectal polyps or colorectal cancer between 2000 and 2014 (Table 1). Among these surgeries, 25% (n=304,578) were performed for non-malignant colorectal polyps. The majority of patients having surgery for non-malignant colorectal polyps were non-Hispanic white, had Medicare, and were in the highest category of household income. Most surgery for non-malignant colorectal polyps was performed in hospitals categorized as large bed size, urban teaching hospitals and in the Southern region of the United States.

Table 1.

Estimated number of cases and characteristics of adults having surgery for non-malignant colorectal polyps or colorectal cancer in the US between 2000 and 2014.

| Non-malignant colorectal polyp | Colorectal cancer | |

|---|---|---|

| n = 304,578 | n = 925,880 | |

| Sex, n (%) | ||

| Male | 151,797 (49.9) | 460,032 (49.7) |

| Female | 152,432 (50.1) | 464,944 (50.3) |

| Age, mean (standard deviation) | 65.9 (24.6) | 68.4 (27.9) |

| Race/Ethnicity, n (%) | ||

| Non-Hispanic white | 201,467 (81.1) | 589,731 (79.7) |

| Non-Hispanic black | 25,550 (10.3) | 68,607 (9.3) |

| Hispanic | 12,274 (4.9) | 43,042 (5.8) |

| Other | 9,101 (3.7) | 38,622 (5.2) |

| Missing | 56,186 | 185,877 |

| Primary insurance, n (%) | ||

| Medicare | 165,005 (54.3) | 554,232 (60.1) |

| Medicaid | 7,873 (2.6) | 32,380 (3.5) |

| Private | 122,678 (40.4) | 306,528 (33.2) |

| Other insurance | 5,418 (1.8) | 15,520 (1.7) |

| Self-pay | 2,760 (0.9) | 13,878 (1.5) |

| Household income3, n (%) | ||

| Low | 56,920 (19.0) | 175,011 (19.3) |

| Medium | 75,123 (25.1) | 234,029 (25.7) |

| High | 79,176 (26.5) | 234,285 (25.8) |

| Highest | 87,948 (29.4) | 265,859 (29.2) |

| Hospital bed sizeb, n (%) | ||

| Small | 34,722 (11.4) | 110,733 (12.0) |

| Medium | 77,701 (25.6) | 230,784 (25.0) |

| Large | 191,225 (63.0) | 581,898 (63.0) |

| Hospital type, n (%) | ||

| Urban, teaching | 140,953 (46.4) | 431,046 (46.7) |

| Urban, nonteaching | 128,818 (42.4) | 374,241 (40.5) |

| Rural, nonteaching | 33,877 (11.2) | 118,128 (12.8) |

| Hospital region, n (%) | ||

| Northeast | 57,260 (18.8) | 183,891 (19.9) |

| Midwest | 72,165 (23.7) | 228,297 (24.7) |

| South | 121,704 (40.0) | 332,809 (36.0) |

| West | 53,449 (17.6) | 180,883 (19.5) |

Between 2000 and 2002 household income was characterized by the following quartiles: $1–$24,999 (low), $25,000–$34,999 (medium), $35,000–$44,999 (high), and $45,000 and above (highest); from 2003 onward, income was characterized into quartiles within each ZIP code

Hospital size categories are based on the number of hospital beds; cut points were chosen for each region and location (rural, non-teaching, urban non-teaching, and urban teaching) combination so that approximately ⅓ of hospitals would appear in each size category

Incidence Estimates

In 2014, the incidence rate for non-malignant colorectal polyp surgery was 1.0 per 100,000 among those 20–49 years old, 14.4 per 100,000 among those 50–64 years old, 34.5 per 100,000 among those 65–79 years old, and 13.4 per 100,000 among those ≥80 years old (Table 2). The incidence estimates for men and women were similar (9.7 vs. 9.2 per 100,000, respectively). Non-Hispanic whites compared with non-Hispanic blacks and Hispanics had a higher rate of surgery (10.5 vs. 8.6 vs. 3.7 per 100,000, respectively). Incidence rates per 100,000 US adults were higher in the Midwest (10.8 per 100,000) and South (10.6 per 100,000) compared with the Northeast (7.8 per 100,000) and West (7.5 per 100,000). The incidence rates for surgery were highest in large (3.1 per 100,000) and medium (1.8 per 100,000) urban teaching hospitals and large (1.4 per 100,000) urban nonteaching hospitals (Table 3).

Table 2.

Crude incidence rate of surgery for non-malignant colorectal polyps per 100,000 US adults ≥ 20 years old, stratified by age category, sex, race/ethnicity and hospital region.

| 2000 | 2014 | IRD (95% CI) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| # of Cases | Rate per 100,000 | # of Cases | Rate per 100,000 | ||

| Age category, years | |||||

| 20–49 | 1180 | 0.9 | 1300 | 1.0 | 0.09 (0.02, 0.17) |

| 50–64 | 3780 | 6.4 | 8450 | 14.4 | 7.95 (7.58, 8.31) |

| 65–79 | 6480 | 22.3 | 10000 | 34.5 | 12.13 (11.26, 12.99) |

| ≥80 | 1812 | 16.1 | 1520 | 13.4 | −2.60 (−3.61, −1.59) |

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 6637 | 6.1 | 10575 | 9.7 | 3.61 (3.37, 3.84) |

| Female | 6614 | 5.7 | 10695 | 9.2 | 3.51 (3.29, 3.73) |

| Race/Ethnicity | |||||

| Non-Hispanic white | 8484 | 5.6 | 15900 | 10.5 | 4.88 (4.68, 5.08) |

| Non-Hispanic black | 907 | 3.5 | 2225 | 8.6 | 5.08 (4.66, 5.50) |

| Hispanic | 346 | 1.1 | 1180 | 3.7 | 2.65 (2.40, 2.89) |

| Other | 255 | 1.6 | 755 | 4.7 | 3.12 (2.73, 3.51) |

| Hospital region | |||||

| Northeast | 2662 | 6.4 | 3230 | 7.8 | 1.37 (1.01, 1.74) |

| Midwest | 3333 | 6.8 | 5275 | 10.8 | 3.98 (3.61, 4.35) |

| South | 4881 | 5.9 | 8865 | 10.6 | 4.78 (4.50, 5.05) |

| West | 2375 | 4.6 | 3900 | 7.5 | 2.94 (2.64, 3.24) |

Table 3.

Crude incidence rate of surgery for non-malignant colorectal polyps per 100,000 US adults ≥ 20 years old, in urban teaching, urban nonteaching, and rural nonteaching hospitals, stratified by bed size.

| 2000 | 2014 | IRD (95% CI) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| # of Cases | Rate per 100,000 | # of Cases | Rate per 100,000 | ||

| Urban, teaching | |||||

| Small | 691 | 0.3 | 2715 | 1.2 | 0.89 (0.85, 0.95) |

| Medium | 1546 | 0.7 | 4085 | 1.8 | 1.13 (1.06, 1.19) |

| Large | 3591 | 1.6 | 6875 | 3.1 | 1.46 (1.37, 1.55) |

| Urban, nonteaching | |||||

| Small | 723 | 0.3 | 870 | 0.4 | 0.07 (0.03, 0.10) |

| Medium | 1518 | 0.7 | 1785 | 0.8 | 0.12 (0.07, 0.17) |

| Large | 3403 | 1.5 | 3100 | 1.4 | −0.13 (−0.20, −0.06) |

| Rural, nonteaching | |||||

| Small | 90 | 0.0 | 280 | 0.1 | 0.08 (0.07, 0.10) |

| Medium | 341 | 0.2 | 350 | 0.2 | 0.00 (−0.02, 0.03) |

| Large | 1341 | 0.6 | 1210 | 0.5 | −0.06 (−0.10, −0.01) |

Trends

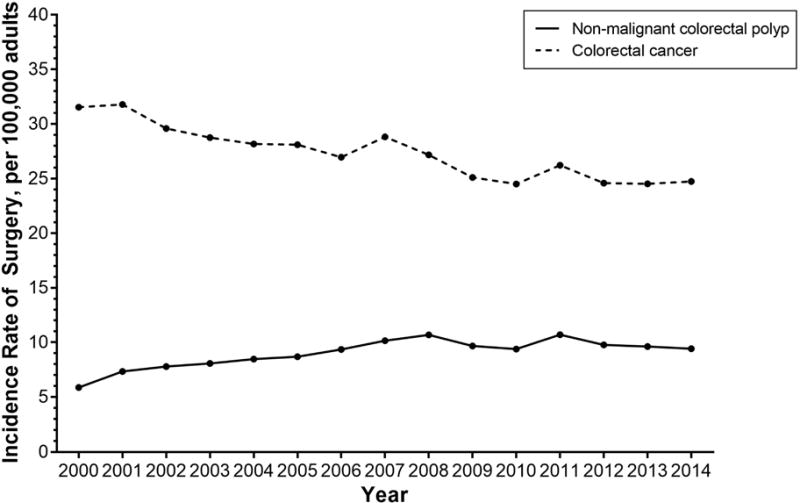

The incidence rate of surgery for non-malignant colorectal polyps has significantly increased over time from 5.9 in 2000 to 9.4 in 2014 per 100,000 adults (IRD 3.56, 95% CI 3.40, 3.72) (Figure 1). During this time, the rate of surgery for colorectal cancer has significantly decreased from 31.5 to 24.7 surgeries per 100,000 adults (IRD −6.80, 95% CI −7.11, −6.49).

Figure 1.

Annual incidence rate for non-malignant colorectal polyp and colorectal cancer surgery per 100,000 US adults (≥20 years old) in the United States between 2000 and 2014

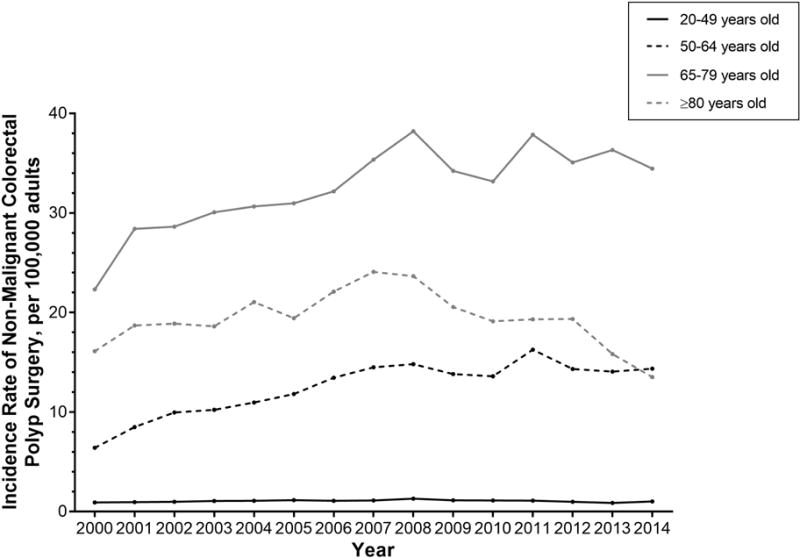

The rate of surgery for non-malignant colorectal polyps has significantly increased across the study period among adults 50–64 years olds (IRD 7.95, 95% CI 7.58, 8.31), and 65–79 years old (IRD 12.13, 95% CI 11.26, 12.99) (Table 2 and Figure 2). Adults ≥80 years old were significantly less likely to have surgery for a non-malignant colorectal polyp in 2014 compared to 2000 (IRD −2.60, 95% CI −3.61, −1.59), though this age group experienced higher rates of surgery for polyps between 2004–2008, followed by a decline.

Figure 2.

Annual incidence rate for non-malignant colorectal polyp surgery per 100,000 US adults, stratified by age.

Stratified by sex, the incidence rate of surgery for non-malignant colorectal polyps has significantly increased among both men (IRD 3.61, 95% CI 3.37, 3.84) and women (IRD 3.51, 95% CI 3.29, 3.73) (Table 2). Stratified by race/ethnicity, the incidence rate of surgery for non-malignant colorectal polyps has significantly increased among non-Hispanic whites (IRD 4.88, 95% CI 4.68, 5.08), non-Hispanic blacks (IRD 5.08, 95% CI 4.66, 5.50), Hispanics (IRD 2.65, 95% CI 2.40, 2.89), and other race (IRD 3.12, 95% CI 2.73, 3.51) adults (Table 2 and Supplemental Figure 2).

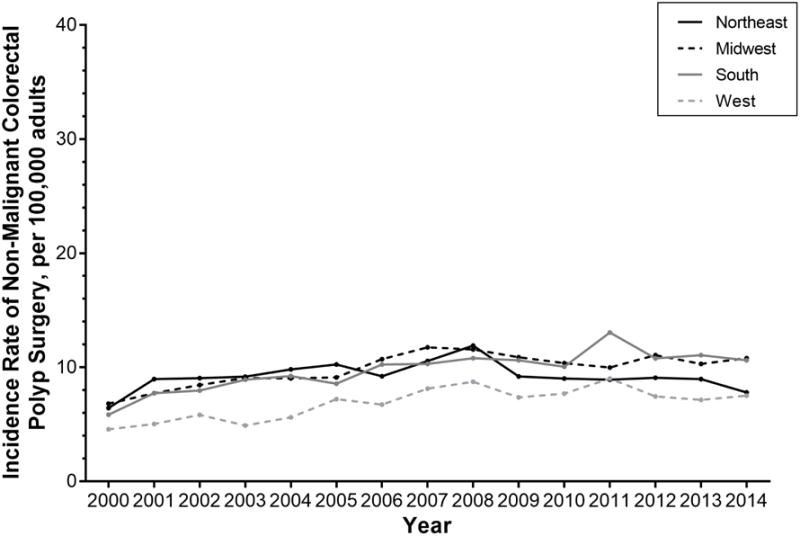

Stratified by region, the incidence rate of surgery for non-malignant colorectal polyps has significantly increased among hospitals in the Northeast (IRD 1.37, 95% CI 1.01, 1.74), Midwest (IDR 3.98, 95% CI 3.61, 4.35), South (IRD 4.78, 95% CI 4.50, 5.05), and West (IRD 2.94, 95% CI 2.64, 3.24) (Table 2 and Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Annual incidence rate for non-malignant colorectal polyp surgery per 100,000 US adults, stratified by hospital region.

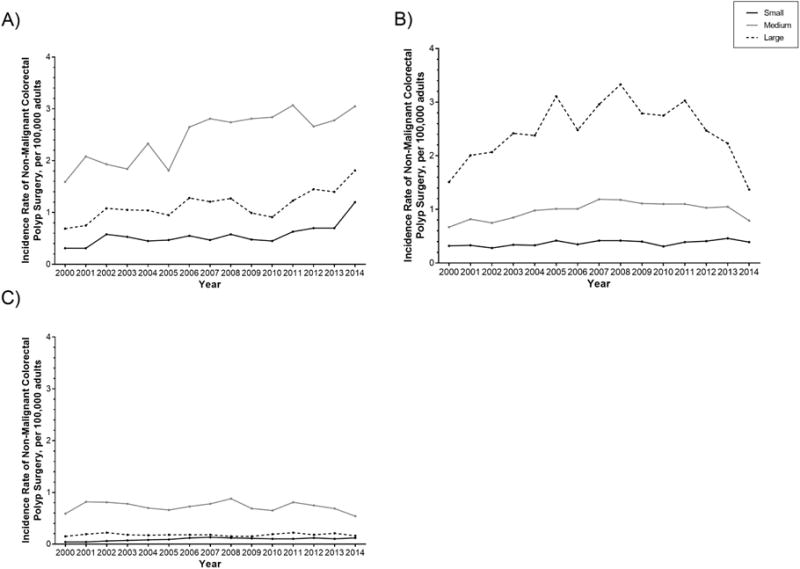

Stratified by teaching status, urban/rural location and bed size, the incidence rate of surgery for non-malignant colorectal polyps has significantly increased in urban, teaching hospitals of all bed sizes (small: IRD 0.89 [95% CI 0.85, 0.95]; medium: IRD 1.13 [95% CI 1.06, 1.19]; large: IRD 1.46 [95% CI 1.37–1.55]) (Table 3 and Figure 4). The rate of surgery has increased in small (IRD 0.07, 95% CI 0.03, 0.10) and medium (IRD 0.12, 95% CI 0.07, 0.17) sized urban nonteaching hospitals but decreased in large (IRD −0.13, 95% CI −0.20, −0.06) urban nonteaching hospitals. The rate of surgery has increased in small (IRD 0.08, 95% CI 0.07, 0.10) rural nonteaching hospitals, is unchanged in medium (IRD 0.00, 95% CI −0.02, 0.03) rural nonteaching hospitals and decreased in large (IRD −0.06, 95% CI −0.10, −0.01) rural nonteaching hospitals.

Figure 4.

Annual incidence rate for non-malignant colorectal polyp surgery per 100,000 US adults, among A) urban, teaching hospitals, B) urban, nonteaching hospitals, and C) rural, nonteaching hospitals, stratified by bed size.

Among our cases with non-malignant colorectal polyps, 4.4% also had an ICD 9 code for diverticulitis compared with 1.2% of patients with colorectal cancer. To address this difference, we performed a sensitivity analysis excluding all patients with an ICD 9 code for diverticulitis and found no meaningful change in our results (Supplemental Tables).

Discussion

In this large nationally representative sample, surgery for non-malignant colorectal polyps is common. While the volume of colorectal resection procedures has remained stable in the United States over the last decade,12 the rate of surgery for non-malignant colorectal polyps has increased in individuals aged 20–79 among both men and women and including all races/ethnicities. This increase is nationwide and is primarily taking place in urban teaching hospitals.

The increase in surgery for non-malignant colorectal polyps is concerning. The literature to date is clear that endoscopic resection is the preferred management of non-malignant colorectal polyps.8–10, 13, 14 This recommendation is based on evidence that almost all (>90%) complex non-malignant colorectal polyps, regardless of size, can be safely resected endoscopically with an outpatient procedure.5 Compared with partial colectomy, endoscopic resection is more cost effective6, 7 and is associated with a reduced risk of adverse events.3–5 Among patients who have surgery for a non-malignant colorectal polyp, 14% will have at least one major short-term postoperative event.3 Partial colectomy can be complicated by need for an ostomy and postoperative infection, wound dehiscence, readmission, reoperation, and less commonly, death.3 Notably, non-malignant colorectal polyps have no risk of lymph node metastasis and are amenable to endoscopic cure.

We had hypothesized that surgery for non-malignant colorectal polyps would be both uncommon and declining in teaching hospitals where providers are more likely to be familiar with current guidelines and to have access to endoscopic mucosal resection. Instead, we found that surgery for non-malignant colorectal polyps is both common and significantly increasing in teaching hospitals. These findings are difficult to understand or explain.

First, we considered the possibility that surgery for non-malignant colorectal polyps might be concentrating in teaching hospitals because more cases were referred to high-volume centers. In the United States, there has been a trend towards centralization of cancer procedures because increasing procedure volumes are associated with improved clinical outcomes. While this trend has been specific to esophageal and pancreatic procedures, there has been little to no centralization of colon and rectal cancer procedures to explain the trends we found.15

Alternatively, if referrals for endoscopic resection of non-malignant colorectal polyps are increasing at teaching hospitals, inappropriate referrals and “failed” endoscopic resections would result in an increased volume of surgery in these centers. Importantly, most of these surgeries would be for either suspected or confirmed malignancy and would be captured with a colorectal cancer code. This referral pattern would not translate into a substantially increasing incidence of surgery for non-malignant colorectal polyps. In a meta-analysis of the efficacy and safety of endoscopic resection of large colorectal polyps, 14% of patients were sent to surgery before any attempt at endoscopic resection, because the endoscopic appearance was suggestive of submucosal invasion. In the same analysis, 8% of patients underwent surgery for non-curative resection and most of those (62%) were for invasive cancer.5

We also considered whether increased colorectal cancer screening and therefore increased detection of non-malignant colorectal polyps could explain the increase in surgery for non-malignant colorectal polyps. While the proportion of adults screened for colorectal cancer increased in the United States before 2010,16–18 the rate of screening did not significantly change between 2010 and 2015 (60% in 2010, 59% in 2013, 63% in 2015).19 Furthermore, three studies suggest that there has not been an increase in the annual number of screening colonoscopies. The first study used data from the National Survey of Endoscopic Capacity and found that there were 6–7 million screening colonoscopies performed in 2002 in the United States20 and 6.3 million performed in 2012.1 The second study used administrative data from 106 health plans and found that insured Americans aged 50 to 64 years significantly reduced their use of screening colonoscopy during the 2007–2009 recession.21 The third study used Medicare claims and found that the number of colonoscopies performed declined from 91 procedures per 1,000 beneficiaries in 2006 to 84 procedures per 1,000 beneficiaries in 2009.22 Finally, the total volume of colonoscopies in the United States appears to be static. Using data from National Survey of Endoscopic Capacity, there were an estimated 14.2 million colonoscopies and 2.8 million flexible sigmoidoscopies performed in 200220 and 15 million total colonoscopies in 20121 in the United States. Using MarketScan Commercial Claims and Encounters data (Truven Health Analytics, Ann Arbor, MI), we have examined temporal trends in colonoscopy use in adults 18–64 years old. The overall colonoscopy rate increased from 37.3 per 1,000 in 2001 to 48.5 per 1,000 person-years in 2008. Since 2008, the rate decreased and then plateaued (45.9 per 1,000 in 2010, 45.1 per 1,000 in 2012, 45.6 per 1,000 in 2014) (unpublished data). Thus, while we cannot definitively exclude an association between secular trends in colonoscopy utilization and surgery volumes, we believe this is an unlikely explanation for our findings.

There are other potential explanations for the increasing rate of surgery. There is evidence that polyp detection (particularly detection of adenomatous polyps) is improving with time, however the improved detection appears to be attributable to small or diminutive non-advanced adenomas, which would not be expected to contribute to (appropriate) surgery.23, 24 It is also conceivable that increasing production pressure and inadequate reimbursement for endoscopic mucosal resection may persuade endoscopists to refer patients with complex non-malignant colorectal polyps for surgery. Finally, there is the issue of risk. The most common risks associated with a complex endoscopic resection include incomplete resection, bleeding and perforation. For endoscopists without additional training in advanced endoscopic resection these risks may be perceived as too great, especially when they have the option of referring for a surgical resection. In contrast, from a surgeon’s perspective a laparoscopic resection of a non-malignant colorectal polyp is generally simpler and easier then a resection for an inflammatory process or bulky cancer.25 These relative risks could drive a tendency for endoscopist to refer and for surgeons to operate.

It is important to emphasize that not all surgery done for non-malignant colorectal polyps is inappropriate–some polyps may not be amenable to endoscopic resection, and some patients may opt to pursue colectomy as a more definitive procedure. It may be that the literature recommending endoscopic resection for complex non-malignant colorectal polyps is somehow inaccurate, failing to capture a large patient population for whom surgical resection is the better choice despite its increased risks.

Conversely, it is possible that we are failing to implement our guidelines,8–10 which recommend referral to an advanced endoscopist for attempted endoscopic resection. If so, we have to ask why.26–28 Are patients aware of the endoscopic option for their non-malignant colorectal polyp? Are they even aware that their lesion is non-malignant? Do patients prefer the more definitive procedure? Are endoscopists able to identify an endoscopically curable polyp? Are endoscopists familiar with the spectrum of lesions amenable to endoscopic resection? Is there a lack of access to a local or regional advanced endoscopist? What proportion of patients have a repeat endoscopy with an advanced endoscopists? Can our health care system meet the demand for advanced endoscopists?

Our study has several strengths. We used nationally representative data that included information on patients, regardless of payer, and generated national estimates of hospital inpatient stays for surgery for non-malignant colorectal polyps. To put these trends into context, we also generated national estimates for surgery for colorectal cancer. As expected, with the declining incidence of colorectal cancer in the United States,29 the rate of surgery for colorectal cancer has significantly decreased during the study period.

Our study has several limitations. We utilized administrative codes to identify our cases. The sensitivity of ICD-9 codes for non-malignant colorectal polyps is unknown, but this definition has been used previously11, 30 and we would expect it to have a high specificity. We could have underestimated the incidence of surgery for non-malignant colorectal polyps if these cases were miscoded as colorectal cancer or missing a diagnosis code. Likewise, we could have overestimated the incidence of surgery for non-malignant colorectal polyps if these cases had colorectal cancer but were miscoded as non-malignant colorectal polyps. To reduce the risk of misclassification, patients with diagnoses for both benign neoplasms and colorectal cancer were classified as having colorectal cancer. We excluded those patients with inflammatory bowel disease or those who underwent a total colectomy because these patients are more likely to have familial adenomatous polyposis To assess whether polyps might be an incidental finding, we excluded all patients diagnosed with diverticulitis (ICD-9 code 562.11) in a sensitivity analysis. While the ICD-9 code for benign polyp includes lesions of the anal canal, our analysis only included procedure codes for the colon and rectum.

In conclusion, surgery for non-malignant colorectal polyps appears to be both common and increasing. These findings appear to be independent of screening colonoscopy utilization during the time period observed and stand against a body of research that suggests endoscopic resection of non-malignant colorectal polyps is safer and more cost-effective. Further research will be necessary to better understand who these patients are and why they are undergoing surgical procedures that may not be indicated.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by grants from the National Institutes of Health, K23DK113225, R25CA116339, KL2TR001109 and T35DK007386-37

Abbreviations

- NIS

National Inpatient Sample

- ICD-9

International Classification of Disease, Ninth edition codes

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest/Disclosures: None

Writing Assistance: None

Author Contributions: AFP, KSC, PDS, SKM, SDC, AB, MK, ISG: study concept and design; analysis and interpretation of data; drafting of the manuscript; critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content

References

- 1.Joseph DA, Meester RG, Zauber AG, et al. Colorectal cancer screening: Estimated future colonoscopy need and current volume and capacity. Cancer. 2016;122:2479–86. doi: 10.1002/cncr.30070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lieberman DA, Williams JL, Holub JL, et al. Race, ethnicity, and sex affect risk for polyps >9 mm in average-risk individuals. Gastroenterology. 2014;147:351–8. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.04.037. quiz e14–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Peery AF, Shaheen NJ, Cools KS, et al. Morbidity and mortality after surgery for nonmalignant colorectal polyps. Gastrointest Endosc. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2017.03.1550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rao AK, Soetikno R, Raju GS, et al. Large Sessile Serrated Polyps Can Be Safely and Effectively Removed by Endoscopic Mucosal Resection. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14:568–74. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2015.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hassan C, Repici A, Sharma P, et al. Efficacy and safety of endoscopic resection of large colorectal polyps: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gut. 2016;65:806–20. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2014-308481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Law R, Das A, Gregory D, et al. Endoscopic resection is cost-effective compared with laparoscopic resection in the management of complex colon polyps: an economic analysis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2016;83:1248–57. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2015.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jayanna M, Burgess NG, Singh R, et al. Cost Analysis of Endoscopic Mucosal Resection vs Surgery for Large Laterally Spreading Colorectal Lesions. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14:271–8. e1–2. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2015.08.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ferlitsch M, Moss A, Hassan C, et al. Colorectal polypectomy and endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR): European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Clinical Guideline. Endoscopy. 2017;49:270–297. doi: 10.1055/s-0043-102569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rex DK, Bond JH, Winawer S, et al. Quality in the technical performance of colonoscopy and the continuous quality improvement process for colonoscopy: recommendations of the U.S. Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:1296–308. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.05812.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rex DK, Schoenfeld PS, Cohen J, et al. Quality indicators for colonoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;81:31–53. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2014.07.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zogg CK, Najjar P, Diaz AJ, et al. Rethinking Priorities: Cost of Complications After Elective Colectomy. Ann Surg. 2016;264:312–22. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000001511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weiss AJ, Elixhauser A. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) Statistical Briefs. Rockville (MD): 2006. Trends in Operating Room Procedures in U.S. Hospitals, 2001–2011: Statistical Brief #171. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gorgun E, Benlice C, Church JM. Does Cancer Risk in Colonic Polyps Unsuitable for Polypectomy Support the Need for Advanced Endoscopic Resections? J Am Coll Surg. 2016;223:478–84. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2016.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ruhl CESB, Byrd-Hold DD, et al. Costs of Digestive Diseases. In: Everhart JE, editor. The burden of digestive diseases in the United States. US Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office; 2008. p. 142. (NIH Publication No. 09-6443). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stitzenberg KB, Meropol NJ. Trends in centralization of cancer surgery. Ann Surg Oncol. 2010;17:2824–31. doi: 10.1245/s10434-010-1159-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shapiro JA, Klabunde CN, Thompson TD, et al. Patterns of colorectal cancer test use, including CT colonography, in the 2010 National Health Interview Survey. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2012;21:895–904. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-12-0192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Klabunde CN, Cronin KA, Breen N, et al. Trends in colorectal cancer test use among vulnerable populations in the United States. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2011;20:1611–21. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-11-0220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rim SH, Joseph DA, Steele CB, et al. Colorectal cancer screening - United States, 2002, 2004, 2006, and 2008. MMWR Suppl. 2011;60:42–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cancer Trends Progress Report. 2017 Jan; Retrieved from URL September 29, 2017. https://progressreport.cancer.gov/detection/colorectal_cancer).

- 20.Seeff LC, Richards TB, Shapiro JA, et al. How many endoscopies are performed for colorectal cancer screening? Results from CDC’s survey of endoscopic capacity. Gastroenterology. 2004;127:1670–7. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.09.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dorn SD, Wei D, Farley JF, et al. Impact of the 2008–2009 economic recession on screening colonoscopy utilization among the insured. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;10:278–84. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2011.11.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Koenig L, Gu Q. Growth of ambulatory surgical centers, surgery volume, and savings to medicare. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:10–5. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2012.183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brenner H, Altenhofen L, Kretschmann J, et al. Trends in Adenoma Detection Rates During the First 10 Years of the German Screening Colonoscopy Program. Gastroenterology. 2015;149:356–66.e1. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wallace MB, Crook JE, Thomas CS, et al. Effect of an endoscopic quality improvement program on adenoma detection rates: a multicenter cluster-randomized controlled trial in a clinical practice setting (EQUIP-3) Gastrointest Endosc. 2017;85:538–545.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2016.07.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Itah R, Greenberg R, Nir S, et al. Laparoscopic surgery for colorectal polyps. JSLS. 2009;13:555–9. doi: 10.4293/108680809X12589998404407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Grimm I, Peery AF, Kaltenbach T, et al. Quality Matters: Improving the Quality of Care for Patients With Complex Colorectal Polyps. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017 doi: 10.1038/ajg.2017.409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Young-Fadok TM. Pro: a large colonic polyp is best removed by laparoscopy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:270–2. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Soetikno R, Gotoda T. Con: colonoscopic resection of large neoplastic lesions is appropriate and safe. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:272–5. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2016. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66:7–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hernandez-Boussard TM, McDonald KM, Morrison DE, et al. Risks of adverse events in colorectal patients: population-based study. J Surg Res. 2016;202:328–34. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2016.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.