Abstract

Research increasingly means that patients, caregivers, health professionals, other stakeholders, and academic investigators work in partnership. This requires effective collaboration rooted in mutual respect, involvement of all participants, and good communication. Having conducted such partnered research over multiple projects, and having recently completed a project together funded by the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute, we collaboratively developed a list of 12 lessons we have learned about how to ensure effective research partnerships. To foster a culture of mutual respect, hold early in-person meetings, with introductions focused on motivation, offer appropriate orientation for everyone, and maintain awareness of individual and project goals. To actively involve all team members, it is important to ensure sufficient funding for everyone’s participation, to ask for and recognize diverse contributions, and to seek the input of quiet members. To facilitate good communication, teams should carefully consider labels, avoid jargon and acronyms, judiciously use homogeneous and heterogeneous subgroups, and keep progress visible. In offering pragmatic, actionable lessons we have learned through our separate and shared experiences, we hope to help foster more patient-centered research via productive and enjoyable research collaborations.

KEY WORDS: patient engagement, patient-centered outcomes research, stakeholder engagement

INTRODUCTION

Health research teams increasingly include patients, caregivers, clinicians, and other stakeholders whose primary careers are not health research. This may occur because team leaders are convinced of the merits of such an approach, because funders or publishers require it, or both.1 – 4 Such partnerships are intended to increase the relevance of research to those who might benefit from it and thus to reduce research waste.5 This is an excellent and laudable aim; however, there is relatively little practical guidance available about how to effectively conduct such partnered research.

Previous reviews and evaluations demonstrate four points about conducting partnered research. First, research teams with patients, caregivers, and other stakeholder team members tend to involve these stakeholders more at earlier stages in the project than at later stages.6 , 7 Second, people coming into projects without a research background may require orientation in order to participate fully.8 Third, benefits of partnership may be difficult to formally assess.9 Fourth, time requirements are a frequent concern for everyone.7 , 10 These reviews offer valuable evidence syntheses relevant to partnership, as do recommendations from long-standing traditions of methods such as community-based participatory research11 and participatory action research.12 However, as partnered research expands across research types and funding opportunities, more people are engaging in team structures that are new to them. Available frameworks suggest structures for partnerships,13 – 16 and literature promotes broad principles such as addressing issues of power and equity17 – 25 and developing relationships of trust.20 – 22 , 24 – 31 However, it can be difficult for teams, particularly those new to this type of work, to operationalize abstract structures and principles in the specific context of their research project.

In this article, we draw from our collective years of experience as patients, caregivers, clinicians, other stakeholders and academic researchers in partnered projects to offer 12 practical lessons we have learned about how to better conduct partnered research. These lessons are intended for all people working in such projects, including patients, caregivers, clinicians, researchers, policymakers, and others.

DEVELOPING THE LESSONS

Our team recently completed a research project funded by the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute in which we brought our perspectives as patients, caregivers, health care professionals, other stakeholders, and academic researchers at diverse career stages. Many of us also have other previous or ongoing similar collaborations in other research teams.

We developed this list of lessons learned through iterative consensus-building, offering ideas at regular teleconferences during a 2-year project. After developing a preliminary list of lessons for our own internal use, we realized that our lessons may also be useful to others. We therefore conducted two rounds of a modified Delphi process32 within the study team to reach consensus on the importance of each lesson for different types of research projects and to organize the lessons into themes.

LESSONS

Our lessons learned are classed within three broad themes, each with four lessons.

Theme 1: Establishing and maintaining a culture and expectation of mutual respect

Patients, other stakeholders, and academic researchers bring different contributions, perspectives, experiences, and ways of working, all of which are needed to succeed in reaching a common goal. It helps to acknowledge the views and contributions of all participants, to bridge differences or tensions when they arise, and to assume best intentions from everyone.

Have an in-person full team meeting as early as possible. This is especially critical if much of the forthcoming work will happen by email, teleconference, or videoconference. Giving team members the chance to first get to know each other as people helps everyone build a foundation of common understanding, trust, and human relationships that will carry forward into the rest of the work.

-

2.

Introduce yourselves with stories, not titles. Introductions focused primarily on positions and titles can imply hierarchies, contributing to problematic power dynamics. Instead, team members can introduce themselves by discussing how and why they got involved with the project, what they hope to bring to the project, and what motivates them in their role. This format serves two purposes. First, it may help teams establish common ground as people, thus reducing perceived or real power imbalances. Second, framing introductions around motivations may help everyone relate through shared goals.

-

3.

State individual and project goals explicitly. To ensure clarity about project goals and how individual goals fit with the project, it can be helpful to ask all team members to state explicitly what they hope to bring to the project, what they hope to get out of it, and what they hope the project contributes to health care. Teams should then assess the alignment between individual and project goals and periodically review the extent to which each project is meeting these goals.

-

4.

Offer orientation to everyone. Orientation can be useful to team members who are new to research and also to those who are new to working in diverse stakeholder teams or in a new clinical setting. This orientation should lay a foundation for mutual respect, understanding of perspectives, and familiarity with terminology. It is important to avoid homogenization of the diverse perspectives that people would otherwise bring to a project. Orientation should not be positioned as something intended to correct knowledge deficits among team members who are not academic researchers. All team members may have things to learn. It is also important to consider terminology. When one of our academic team members initially raised the potential of “training,” some stakeholders noted the implicit power imbalance inherent in the term and suggested that “orientation” would be a better label.

Theme 2: Actively involving all team members

Starting off well with a diversity of perspectives is an important first step. However, to truly capitalize on the potential benefits of such diverse perspectives and make the whole greater than the sum of its parts, we must actively involve all team members. Careful consideration when assembling a team can help ensure a productive diversity of background, perspectives and thoughts.

-

5.

Ensure funding for everyone’s participation. No one should have to pay to be at the table. Volunteer work is not free; it uses time that could be spent on other things. Furthermore, requiring team members who are not professional researchers to serve as volunteers means that the only people whose voices are heard are those who can afford to volunteer their time. Team members who are not already receiving a salary for their work on the project should be offered compensation, though they may choose not to accept it. Team members who are primary caregivers should be offered additional funding to cover caregiving expenses incurred in their absence.

-

6.

Recognize different kinds of contributions and efforts. Each person on the team brings important contributions. Our collective experience leads us to believe that it is important to recognize all types of work involved in these contributions. Simply being involved and sharing intimate personal details about one’s health or the health of a loved one, or bringing up the same issues repeatedly and not seeing significant changes, may be emotionally taxing work for patients or caregivers. Acknowledging this work privately with the person or within the team can help highlight the effort required and how each person’s contributions influence the project.

-

7.

Invite people to contribute and take up roles. Although it’s important not to burden team members, it’s also important not to go too far in the other direction. People get involved in projects because they want to contribute, and may simply need an invitation to take up specific roles. This could take the form of different people taking notes at meetings, sharing meeting facilitation roles, or leading activities. For example, at an in-person team meeting, one of our patient team members led an exercise designed to foster empathy and creative collaboration across different roles in health care.33

-

8.

Privately check in with people who are quiet. Team leaders should check in privately with team members who have not spoken up much, create space during meetings that allows a roundtable contribution of all members, and invite those who have been quiet during the meeting to share their perspectives on the topic under discussion. Conference calls can make this more challenging, whereas in-person meetings allow meeting facilitators to monitor body language. Regardless of meeting format, however, this should be done with care and sensitivity to avoid putting individuals on the spot. Some people may prefer to comment individually, by email or in a subsequent meeting after reviewing notes and summary documents.

Theme 3: Facilitating good communication

Good communication is important to the success of any collaborative endeavor. However, it is arguably more critical within a team in which people may not have worked together before and may be bringing different expectations about how work ought to proceed.

-

9.

Think carefully about labels, as they convey implicit values. It is critical to become aware of acceptable and unacceptable language. Some communities prefer person-first language—for example, “people with diabetes” rather than “diabetics” or “diabetic patients.” However, other communities may prefer to embrace descriptors as part of their identity—for example, “autistic people.” These preferences may vary across and even within communities. It is worth taking the time to discuss labels. At our first team meeting, one member of our team noted problematic implications with the term, “patient engagement,” and noted, “The engagement is over: we’re partners now.” We adopted “partners” as the term for members of our team. Another member of our team has used the term “patient investigators” in other projects. Similarly, after a team member noted that “non-researcher clinicians” was not an acceptable term, we also worked to appropriately distinguish health care professionals whose primary job function is patient care from professionals who divide their time between research and patient care.

-

10.

Beware of jargon and acronyms. All communities develop shared language over time. When one member of a community is talking to another member of that same community, it is easy to slip into shared jargon and forget that others may not understand. Our team established an agreement that we would aim to avoid jargon and acronyms while also being patient with each other, recognizing that habits are hard to break. We all welcomed requests for explanation when we accidentally used jargon or acronyms. Teams may also find it useful to make a living glossary, updating it as the project progresses.

-

11.

Occasionally regroup in smaller, more homogeneous groups. At our team’s first in-person meeting, we conducted some of our brainstorming work in four smaller groups of people in similar roles (patient and caregiver partners, clinicians and decision aid developers, junior researchers, senior researchers) before reassembling into our large group. Discussions in these more homogenous groups allowed for free-flowing ideas among peers with shared language, reinforcing the sense of purpose within the team. Subsequent discussions in heterogeneous groups allowed for deeper discussion and understanding of different perspectives and terminology.

-

12.

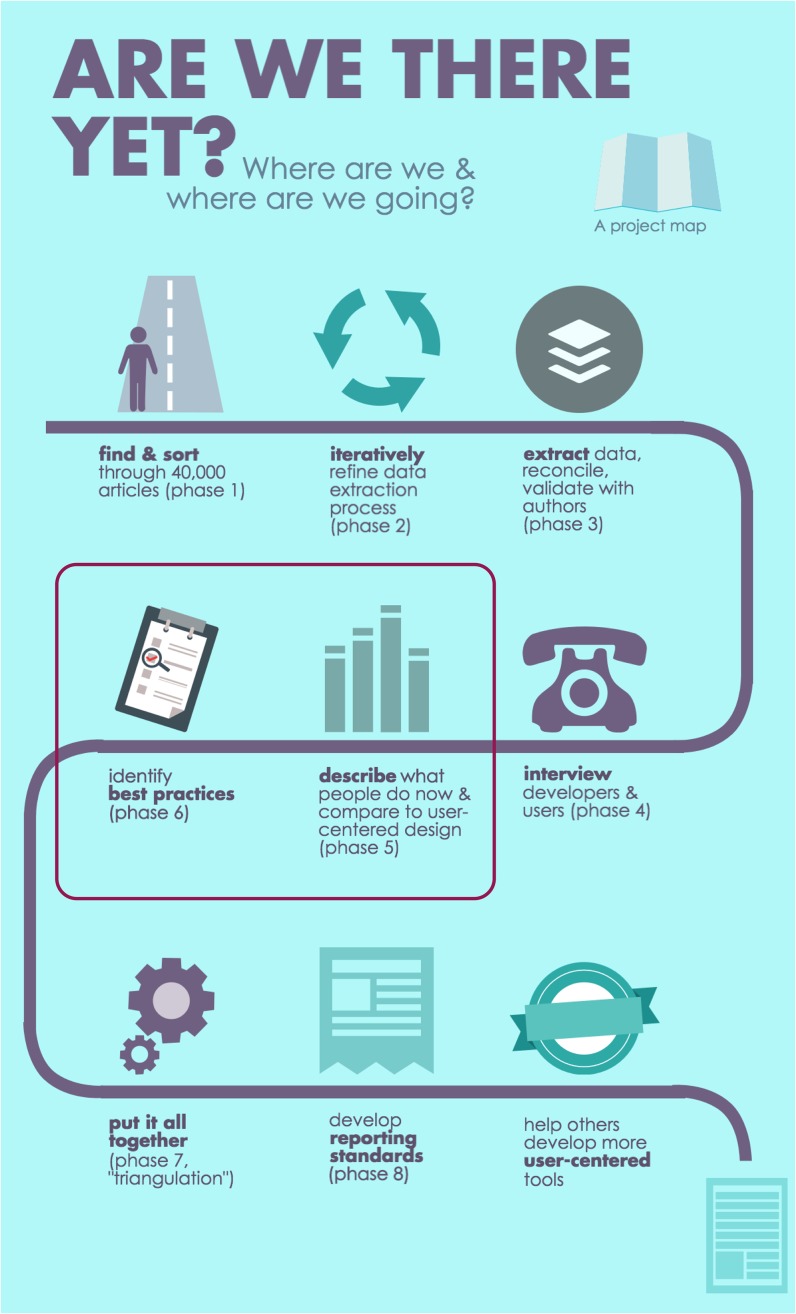

Create a visual map of the project. A map can help everyone understand and talk about the ultimate goals of the project, how the different pieces fit together, and where the team is at each step of the way. Such a visual depiction may provide greater clarity about the process and project deliverables, especially to people who are newer to research. We created our project map (Fig. 1) following suggestions by multiple members of our team.

Figure 1.

Project map (created with Piktochart; piktochart.com).

Relative Importance of Lessons

Some of the lessons are equally important for all research teams, while others are particularly important for heterogeneous teams—for example, the lessons related to establishing common ground and a culture of respect and facilitating communication. Table 1 summarizes the lessons’ relative importance and offers references to literature aligned in principle with the lesson.

Table 1.

Summary of Lessons’ Relative Importance

| Lesson Learned | Equally important for all research teams | Especially important for partnered teams | Aligns with principles or addresses issues articulated in literature |

|---|---|---|---|

| Theme 1: Establishing and maintaining a culture of mutual respect | |||

| 1. Have an in-person full team meeting as early as possible. | X | 21 , 23 | |

| 2. Introduce yourselves with stories, not titles. | X | 21 | |

| 3. State individual and project goals explicitly. | X | 18 , 20 , 21 , 23 – 25 , 27 , 30 , 34 , 35 | |

| 4. Offer orientation to everyone. | X | 10 , 18 , 30 , 31 , 34 , 36 | |

| Theme 2: Actively involving all team members | |||

| 5. Ensure funding for everyone’s participation. | X | 18 , 19 , 23 , 24 , 31 , 36 | |

| 6. Recognize different kinds of contributions and efforts. | X | 18 , 24 , 26 , 27 , 30 , 31 , 36 | |

| 7. Invite people to contribute and take up roles. | X | 21 , 36 | |

| 8. Privately check in with people who are quiet. | X | 36 | |

| Theme 3: Facilitating good communication | |||

| 9. Think carefully about labels, as they convey implicit values. | X | 17 , 21 , 23 | |

| 10. Beware of jargon and acronyms. | X | 10 , 19 , 21 , 23 , 26 , 27 , 30 , 36 , 37 | |

| 11. Occasionally regroup in smaller, more homogeneous groups. | X | 10 , 36 | |

| 12. Create a visual map of the project. | X | 30 | |

DISCUSSION

Effective partnership can be both challenging and rewarding, no matter who is involved and no matter their background. It can sometimes be easier to work through a difference of opinions between people in different roles than between those in similar roles, and teamwork issues such as interpersonal conflict may arise in any team. Nonetheless, partnered research is a new paradigm for many in health research. We hope these practical tips help teams conduct meaningful and enjoyable research.

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI): ME-1306-03174. PCORI had no role in determining the study design, the plans for data collection or analysis, the decision to publish, or the preparation of this manuscript. HOW is funded by a Research Scholar Junior 1 Career Development Award by the Fonds de Recherche du Québec—Santé. NMI is funded by a New Investigator Award (NIA) by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research as well as an NIA from the Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of Toronto. FL is funded by a Tier 1 Canada Research Chair in Shared Decision Making. DS is funded by a University of Ottawa Research Chair in Knowledge Translation to Patients.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

During the course of this project, CAL received salary support as Research Director for the Informed Medical Decisions Foundation, the research division of Healthwise, Inc., a not-for-profit organization (http://www.informedmedicaldecisions.org/). KS held a contract with Animas through 2015 and subsequently a contract with Tandem Diabetes Care. All other authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Brett J, Staniszewska S, Mockford C, et al. Mapping the impact of patient and public involvement on health and social care research: A systematic review. Health Expect. 2014;17(5):637–650. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-7625.2012.00795.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Collier R. Federal government unveils patient-oriented research strategy. Can Med Assoc J. 2011;183(13):E993–E994. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.109-3978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Frank L, Basch E, Selby JV. Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute. The PCORI perspective on patient-centered outcomes research. JAMA. 2014;312(15):1513–1514. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.11100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Topic of Conversation. Den Haag, Netherlands: Dutch organization for health and innovation in healthcare; 2010:1–17

- 5.Chalmers I, Bracken MB, Djulbegovic B, et al. How to increase value and reduce waste when research priorities are set. Lancet. 2014;383(9912):156–165. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62229-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Concannon TW, Fuster M, Saunders T, et al. A systematic review of stakeholder engagement in comparative effectiveness and patient-centered outcomes research. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29(12):1692–1701. doi: 10.1007/s11606-014-2878-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Domecq JP, Prutsky G, Elraiyah T, et al. Patient engagement in research: a systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14:89. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-14-89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brett J, Staniszewska S, Mockford C, et al. A systematic review of the impact of patient and public involvement on service users, researchers and communities. Patient. 2014;7(4):387–395. doi: 10.1007/s40271-014-0065-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Forsythe LP, Szydlowski V, Murad MH, et al. A systematic review of approaches for engaging patients for research on rare diseases. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29(Suppl 3):S788–S800. doi: 10.1007/s11606-014-2895-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Forsythe LP, Ellis LE, Edmundson L, et al. Patient and Stakeholder Engagement in the PCORI Pilot Projects: Description and Lessons Learned. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31(1):13–21. doi: 10.1007/s11606-015-3450-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Israel BA, Schulz AJ, Parker EA, Becker AB. Review of community-based research: assessing partnership approaches to improve public health. Annu Rev Public Health. 1998;19:173–202. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.19.1.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baum F, MacDougall C, Smith D. Participatory action research. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2006;60(10):854–857. doi: 10.1136/jech.2004.028662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute Engagement Rubric. Engagement Rubric for Applicants. http://www.pcori.org/sites/default/files/Engagement-Rubric.pdf. Accessed 26 Feb 2016.

- 14.Canadian Institutes of Health Research Strategy for Patient-Oriented Research. Patient Engagement Framework. http://www.cihr-irsc.gc.ca/e/documents/spor_framework-en.pdf. Accessed 26 Feb 2016.

- 15.The Engagement Cycle. The Engagement Cycle. http://engagementcycle.org. Published February 22, 2013. Accessed August 7, 2017.

- 16.Carman KL, Dardess P, Maurer M, et al. Patient and family engagement: a framework for understanding the elements and developing interventions and policies. Health Aff. 2013;32(2):223–231. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.1133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Amey MJ, Brown DF, Sandmann LR. A Multidisciplinary Collaborative Approach to a University-Community Partnership: Lessons Learned. J Higher Educ Outreach Engagement. 2002;7(3):19–26. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Israel BA, Parker EA, Rowe Z, et al. Community-based participatory research: lessons learned from the Centers for Children’s Environmental Health and Disease Prevention Research. Environ Health Perspect. 2005;113(10):1463–1471. doi: 10.1289/ehp.7675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.BeLue R, Schafer P, Chung B, Vance M, Lanzi R, O’Campo P. Evaluation of the Community Child Health Research Network (CCHN) Community-Academic Partnership. J Health Disparities Res Pract. 2014;7(5):51–66. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Christopher S, Watts V, McCormick AKHG, Young S. Building and maintaining trust in a community-based participatory research partnership. Am J Public Health. 2008;98(8):1398–1406. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.125757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Garland AF, Brookman-Frazee L. Therapists and researchers: advancing collaboration. Psychother Res. 2015;25(1):95–107. doi: 10.1080/10503307.2013.838655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jagosh J, Bush PL, Salsberg J, et al. A realist evaluation of community-based participatory research: partnership synergy, trust building and related ripple effects. BMC Public Health. 2015;15:725. doi: 10.1186/s12889-015-1949-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Castonguay LG, Youn SJ, Xiao H, Muran JC, Barber JP. Building clinicians-researchers partnerships: lessons from diverse natural settings and practice-oriented initiatives. Psychother Res. 2015;25(1):166–184. doi: 10.1080/10503307.2014.973923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sullivan TP, Price C, McPartland T, Hunter BA, Fisher BS. The Researcher–Practitioner Partnership Study (RPPS): Experiences From Criminal Justice System Collaborations Studying Violence Against Women. Violence Against Women. 2016;23(7):887–907. doi: 10.1177/1077801216650290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Frerichs L, Kim M, Dave G, et al. Stakeholder Perspectives on Creating and Maintaining Trust in Community–Academic Research Partnerships. Health Educ Behav. 2016;44(1):182–191. doi: 10.1177/1090198116648291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Garland AF, Plemmons D, Koontz L. Research-practice partnership in mental health: lessons from participants. Admin Pol Ment Health. 2006;33(5):517–528. doi: 10.1007/s10488-006-0062-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kirchner JE, Kearney LK, Ritchie MJ, Dollar KM, Swensen AB, Schohn M. Research & services partnerships: lessons learned through a national partnership between clinical leaders and researchers. Psychiatr Serv. 2014;65(5):577–579. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201400054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Midboe AM, Elwy AR, Durfee JM, et al. Building strong research partnerships between public health and researchers: a VA case study. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29(Suppl 4):831–834. doi: 10.1007/s11606-014-3017-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.López Turley RN, Stevens C. Lessons From a School District–University Research Partnership. Educ Eval Policy Anal. 2015;37(1_suppl):6S–15S. doi: 10.3102/0162373715576074. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Buick F, Blackman D, O’Flynn J, O’Donnell M, West D. Effective Practitioner-Scholar Relationships: Lessons from a Coproduction Partnership. Public Adm Rev. 2016;76(1):35–47. doi: 10.1111/puar.12481. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kirwan JR, de Wit M, Frank L, et al. Emerging Guidelines for Patient Engagement in Research. Value Health. 2017;20(3):481–486. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2016.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hsu C-C, Sandford BA. The Delphi technique: making sense of consensus. Pract Assess Res Eval. 2007;12(10):1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Walk a Mile Cards. Walk a Mile Cards. http://walkamilecards.com/. Accessed August 7, 2017.

- 34.Sriharan A, Harris J, Davis D, Clarke M. Global Health Partnerships for Continuing Medical Education: Lessons from Successful Partnerships. Health Syst Reform. 2016;2(3):241–253. doi: 10.1080/23288604.2016.1220776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mayer K, Braband B, Killen T. Exploring collaboration in a community-academic partnership. Public Health Nurs. 2017. 10.1111/phn.12346. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 36.Hewlett S, de Wit M, Richards P, et al. Patients and professionals as research partners: challenges, practicalities, and benefits. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;55(4):676–680. doi: 10.1002/art.22091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Redline S, Baker-Goodwin S, Bakker JP, et al. Patient Partnerships Transforming Sleep Medicine Research and Clinical Care: Perspectives from the Sleep Apnea Patient-Centered Outcomes Network. J Clin Sleep Med. 2016;12(7):1053–1058. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.5948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]