Abstract

Primary cilia are solitary, non-motile, axonemal microtubule-based antenna-like organelles that project from the plasma membrane of most mammalian cells and are implicated in transducing hedgehog signals during development. It was recently proposed that aberrant SHH signaling may be implicated in the progression of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF). However, the distribution and role of primary cilia in IPF remains unclear. Here, we clearly observed the primary cilia in alveolar epithelial cells, fibroblasts, and endothelial cells of human normal lung tissue. Then, we investigated the distribution of primary cilia in human IPF tissue samples using immunofluorescence. Tissues from six IPF cases showed an increase in the number of primary cilia in alveolar cells and fibroblasts. In addition, we observed an increase in ciliogenesis related genes such as IFT20 and IFT88 in IPF. Since major components of the SHH signaling pathway are known to be localized in primary cilia, we quantified the mRNA expression of the SHH signaling components using qRT-PCR in both IPF and control lung. mRNA levels of SHH, the coreceptor SMO, and the transcription factors GLI1 and GLI2 were upregulated in IPF compared with control. Furthermore, the nuclear localization of GLI1 was observed mainly in alveolar epithelia and fibroblasts. In addition, we showed that defective KIF3A-mediated ciliary loss in human type II alveolar epithelial cell lines leads to disruption of SHH signaling. These results indicate that a significant increase in the number of primary cilia in IPF contributes to the upregulation of SHH signals.

Keywords: Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, primary cilia, Sonic Hedgehog signaling pathway

INTRODUCTION

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) is a specific form of chronic, irreversible fibrosing interstitial lung diseases of unknown etiology and is characterized by histopathological and radiological findings of usual interstitial pneumonia (UIP)(Raghu et al., 2011). The pathophysiologic mechanisms underlying IPF are poorly understood. Recent studies have shown that activation of the Sonic hedgehog (SHH) signaling plays a critical role in IPF pathophysiology (Bolanos et al., 2012; Cigna et al., 2012). SHH overexpression is observed in epithelial cells lining fibrotic areas in IPF but is undetectable in normal lung tissue (Fitch et al., 2011). Abnormal expression of SHH signaling components, patched-1 (PTCH1), smoothened (SMO), and GLI1, was also increased in human IPF tissues (Bolanos et al., 2012; Cigna et al., 2012).

SHH is a critical morphogen during embryonic lung development, which regulates the interaction between epithelial and mesenchymal cells (Litingtung et al., 1998; Pepicelli et al., 1998) and participates in branching morphogenesis and in controlling alveolar bud size and shape (Cardoso and Lu, 2006). In addition, HH signaling pathway plays an important functional role in fibrosis development in the kidney and in the heart (Ding et al., 2012; Zhou et al., 2014). These studies suggest that HH promotes the myofibroblastic transdifferentiation and proliferation of interstitial fibroblasts. Recent studies have revealed that mammalian HH signaling depends on the primary cilium. The key components of the SHH signaling are localized at the primary cilia (Corbit et al., 2005; Haycraft et al., 2005; Ocbina and Anderson, 2008; Rohatgi et al., 2007). Primary cilia are involved in modulating mammalian SHH signaling downstream of SMO and upstream of the GLI factors (Eggenschwiler and Anderson, 2007; Huangfu and Anderson, 2005). Primary cilia can both mediate and suppress the SHH signaling via the receptor PTCH1, the coreceptor SMO, and the transcription factor GLI. Upon binding of the HH ligand to PTCH1, SMO moves to the cilium, and SHH signaling is activated (Corbit et al., 2005).

Primary cilia are solitary, non-motile, axonemal microtubule-based antenna-like organelles that project from the plasma membrane of most mammalian cells (Wilson and Chuang, 2010). Primary cilia act as a sensory organelle, providing chemosensation, thermosensation and mechanosensation of the extracellular environment. And then primary cilia play a role in mediating specific signaling cues. These functions of primary cilia contribute to maintaining the local cellular environment (Adams et al., 2008). The association of the primary cilia with pathophysiology of lung has largely not been studied. The primary cilia are rarely observed in normal airway epithelium, but are detected after injury (Jain et al., 2010). Although the role of primary cilia in cancers is not well understood, primary cilia are lost in many cancers (Hassounah et al., 2012). It is expected that normal or abnormal functions of primary cilia may contribute to airway epithelium/ tumor biology. Primary cilia have been observed in non-small cell lung carcinomas with a significant reduction in the number of ciliated cells and contribute to progression and metastasis of lung cancer by aiding the adhesion, proliferation, migration and epithelial to mesenchymal transition of lung cancer cells (Hu et al., 2014). However, the distribution and the role of primary cilia in lung fibrotic diseases has been rarely evaluated.

We hypothesized that aberrant SHH signaling in IPF is associated with primary cilia changes involved the pathogenesis of IPF. To confirm that primary cilia changes are necessary for IPF pathogenesis, we investigated the distribution of primary cilia in pulmonary alveoli. We demonstrated primary cilia changes in alveolar epithelium and fibroblasts of IPF lung tissue. Our results strongly suggest that excessive ciliogenesis contributes to the upregulation of the SHH signaling and fibrogenesis in IPF lung tissue.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Human lung tissue specimens

We retrospectively analysed the clinicopathological parameters of 32 patients who had undergone wedge resection for interstitial lung disease between January 2010 and December 2015 at St. Mary’s Hospital, Daejeon, South Korea. Of these, the patients with nonspecific interstitial pneumonia, left lobe resection and other underlying lung diseases, such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), tuberculosis and malignancy were excluded. We reviewed the patients’ medical records to obtain their age, gender, disease duration and smoking history. Finally, three male and 3 female were included for the study. All the patients had been diagnosed with IPF in accordance with clinical practice, based on clinical assessment and reasoning, including consideration of high-resolution computed tomography (HRCT) data. The baseline characteristics of each patient are summarized in Table 1. Paraffin-embedded 6 IPF tissues were obtained for immunofluorescence stain and 6 fresh frozen tissue samples stored in liquid nitrogen tanks for RT-PCR.

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics

| P1 | P2 | P3 | P4 | P5 | P6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 60 | 61 | 61 | 68 | 65 | 64 |

| Gender | Male | Male | Male | Female | Female | Female |

| Weight (Kg) | 74 | 64 | 60 | 58 | 48 | 50 |

| Height (cm) | 169 | 172 | 164 | 155 | 146 | 149 |

| Smoker | Never | Never | Never | Never | Never | Never |

| Location | RLL | RML | RML | RML, RLL | RML, RLL | RLL |

| HRCT | UIP/NSIP | UIP/NSIP | UIP/NSIP | UIP/NSIP | UIP/NSIP | UIP/NSIP |

| Duration* | 2 month | 1 month | 1 month | 6 month | 8 month | 1 month |

| Pulmonary function test | ||||||

| FVC | 4.05 L(91%) | 4.25 L(74%) | 3.79 L(95%) | 2.39 L(55%) | 2.13 L(60%) | 2.07 L(28%) |

| FEV1 | 2.87 L(102%) | 3.02 L(96%) | 2.83 L(104%) | 1.65 L(59%) | 1.49 L(70%) | 1.39 L(42%) |

| FEV1/FVC | 71% | 71% | 72% | 71% | 72% | 71% |

the time presentation of symptoms to diagnosis

RLL, right lower lobe; RML, right middle lobe; UIP, usual interstitial pneumonia; NSIP, nonspecific interstitial pneumonia

Control healthy lung tissues were obtained from normal portion of the lobectomy for lung cancer which is located as far as possible from cancer. To reduce the selection bias between IPF group and non-IPF group, we selected control human samples with similar conditions to the IPF group.

The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board and the methods were carried out in accordance with the approved guidelines of the Catholic University of Korea Daejeon St. Mary’s Hospital (DC17SESI0078).

Immunofluorescence staining

Paraffin-embedded 7 μm-thick tissue-sections were incubated at 56°C for 6 h. Thereafter, tissue-sections were deparaf-finized in xylene and rehydrated through a graded-series of ethanol baths. Antigens were retrieved in antigen retrieval buffer (0.01M citric acid–sodium citrate, pH 6.0) by heating the tissue-sections in an autoclave at 121°C for 25 min. After washing, the tissue-sections were air-dried for 30 min and then rewashed with 1× phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). The tissue-sections were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 30 min, and then permeabilized with 0.5% Triton X-100 in PBS for 10 min at room temperature. Tissue-sections were blocked with 5% bovine serum albumin in PBS for 30 minutes at room temperature. Thereafter, tissue-sections were incubated with primary antibodies for 24 h at 4°C. On the following day, the tissue-section slides were washed three times with 1× PBS and incubated at 4°C for 12 h with secondary antibodies. Primary antibodies against Polyglutamylation Modification (GT335, AdipoGen), γ-tubulin (Sigma-Aldrich), cytokeratin (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), and vimentin (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) were used. GT335, a monoclonal antibody directed against polyglutamylated tubulins, stained the centriole/basal body and the axoneme of ciliated cells, and the centriole of non-ciliated cells. Goat anti-mouse and goat anti-rabbit secondary antibodies conjugated to Alexa Fluor dyes (Invitrogen/Life Technologies) were used for indirect fluorescent detection. The stained slides were observed under an Olympus FluoView FV1000 microscope equipped with a charge-coupled device camera (Olympus Corp.).

Inhibition of ciliogenesis in alveolar epithelial cell lines

A549, human type II alveolar epithelial cell lines were obtained from the Korea Cell Line Bank (Korea) and the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, USA). The cell was grown in an RPMI1640 medium supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% penicillin/streptomycin at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere. Cells were seeded in two 6-well plates. To inhibit ciliogenesis, knockdown of KIF3A was performed using small interference RNA (siRNA) transfection into A549. A549 cells were transfected with siRNA KIF3A using Lipofectamine™ RNAiMAX Transfection Reagent (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Experiments for primary cilia analysis were performed in serum starvation, because serum starvation is commonly used to induce ciliogenesis in cultured cells. To confirm the efficacy of siRNA KIF3A, we performed qRT-PCR and examined primary cilia by immunofluorescence staining. Experiments were done in triplicate.

Analysis of cilia frequency and length in cell lines and lung tissue

The frequency of ciliated cells in lung tissue was determined by counting GT335-positive cilia in 1000 nuclei of alveolar (marked by cytokeratin) or fibroblast (marked by vimentin) cells. However, since there are a few fibroblasts in the normal alveolar septae, only 100 fibroblasts were counted. Primary cilia were manually counted. Primary cilia length was measured using the length measurement tool within the software package (Olympus Corp.). Serial 10 images were captured by adjusting the focus of the 7 μm-thick tissue. Following capture, the 10 images were combined into a picture to allow measurement of the entire length of primary cilia. At least 100 primary cilia were measured to determine the average ciliary length.

mRNA isolation and quantitative RT-PCR

Total RNA was isolated from frozen human tissues (fibrotic lesions and normal portions) or cultured cells using Trizol (Invitrogen, Life Technologies, USA). Complementary DNA (cDNA) was synthesized from the total RNA using M-MLV Reverse Transcriptase and oligo-dT primers (Invitrogen). qRT-PCR was performed using QuantiTect SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (QIAGEN). Each reaction was performed in triplicate. Lists of primer pairs used in qRT-PCR were shown in Table 2. Amplification conditions were as follows: 10 min at 95°C for enzyme activation, and 40 cycles at 95°C denaturation for 10 s, 60°C annealing for 30 s, and 72°C extension for 30 s. The cycle threshold (Ct) values for GAPDH RNA and that of target genes were measured and calculated by computer software (Life Technologies 7500 software, USA).

Table 2.

Lists of primer pairs used in qRT-PCR.

| Gene | Forward | Reverse |

|---|---|---|

| hIFT20 | 5′-AGGCAGGGCTGCATTTTGAT-3′ | 5′-CAAGCTCAATTAGACCACCAACA-3′ |

| hIFT88 | 5′-CAGTGACAGTGGCCAGAACA-3′ | 5′-ATCTGTCCCAGGCAAAGCTC-3′ |

| hSHH | 5′-GAAAGCAGAGAACTCGGTGG-3′ | 5′-CTCAGGTCCTTCACCAGCTT-3′ |

| hIHH | 5′-CATTGAGACTTGACTGGGCAA C-3′ | 5′-AGAGCAGGCTGAGTTGGGAGTCGC-3′ |

| hHHIP | 5′-ATGGTGGGTTGTGCTTTCC-3′ | 5′-AGTTGTGTTTGTGCTTTCTGCT-3′ |

| hSMO | 5′-CAGCAAGATCAACGAGACCA-3′ | 5′-GGCAGCTGAAGGTAATGAGC-3′ |

| hPTCH1 | 5′-CCTCGGGAAACCAGAGAATATG-3′ | 5′-AAACTCCTGTGTAGGTCGTAAAG-3′ |

| hGLI1 | 5′-CACATCCACAGCCTCTCTTT-3′ | 5′-CCTGGGTTCTGAAGGAAGATAAT-3′ |

| hGLI2 | 5′-TTTATGGGCATCCTCTCTGG-3′ | 5′-AAGGCTGGAAAGCACTGTGT-3′ |

| hGLI3 | 5′-CCTCCCAACTCCTCACACAT-3′ | 5′-CAACACCAACTGGTCCCTCT-3′ |

| hGAPDH | 5′-TGCACCACCAACTGCTTAGC-3′ | 5′-GGCATGGACTGTGGTCATGAG-3′ |

(h, human)

Statistical analyses

Differences between mean values were analyzed using t-test. qPCR data were analyzed using Wilcoxon rank sum test. P-value less than 0.05 was considered significant. All analyses were performed using SPSS version 22.0 statistical software (SPSS Inc., USA).

RESULTS

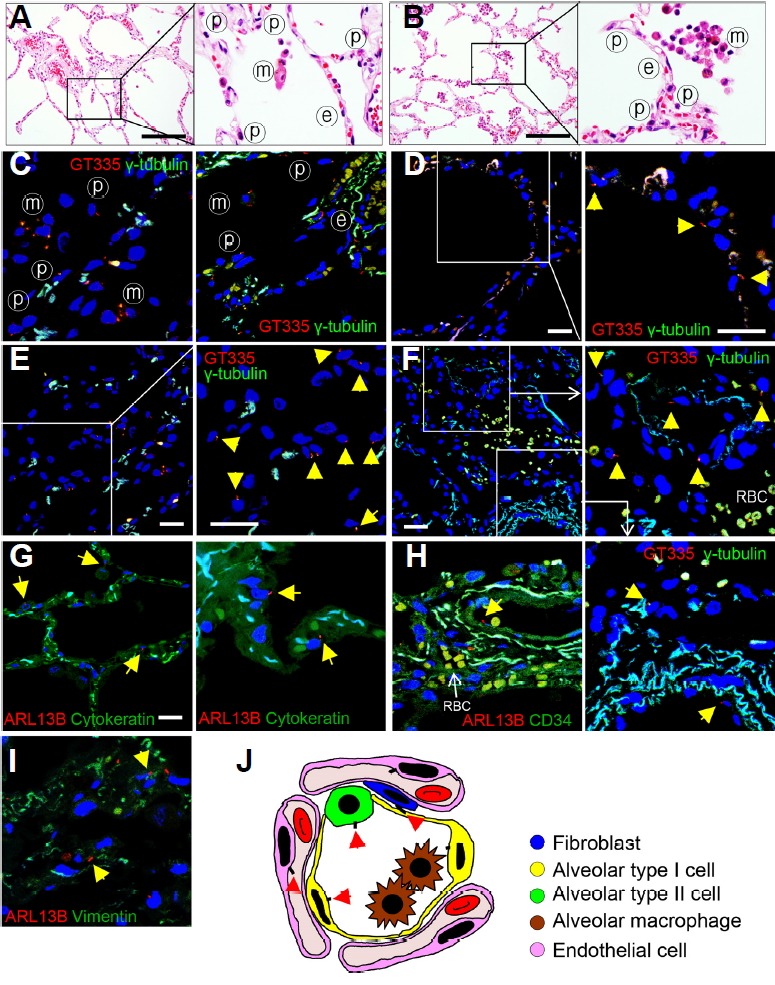

Identification of primary cilia in human normal lung tissue

The pulmonary alveoli consist of an alveolar epithelial layer and extracellular matrix surrounded by capillaries. There are three major types of cells in the alveolar septae; type I and type II alveolar epithelial cells, and alveolar macrophages (Figs. 1A and 1B). To investigate the distribution of primary cilia in the lung parenchyma, we identified primary cilia using antibodies against GT335, ARL13B and γ-tubulin. The axoneme/ basal body was stained with GT335, which is a useful marker for analyzing cilia length. The basal bodies were also stained with γ-tubulin. In the normal lung, primary cilia were detected in alveolar epithelial cells and endothelial cells (Figs. 1C–1F, arrow). Alveolar cells show positive cytoplasmic expression of cytokeratin. The primary cilia protruded from the apical membrane of the alveolar epithelium and variable tilt angles were found (Fig. 1G). Primary cilia were present on endothelial cells where they project into the vessel lumen (Fig. 1H, arrow). Cilia lengths were measured with ImageJ software. The frequency of ciliated cells was 10.77 ± 5.01%, and the average length of the primary cilia was 1.13 ± 0.47 μm in the alveolar epithelium.

Fig. 1. Distribution of primary cilia in normal human lung tissues.

(A, B) The alveolus is made up of a single layer of epithelial cells and contains a dense network of capillaries. ⓟ, pneumocyte; ⓔ, endothelial cell; ⓜ, alveolar macrophage. H&E staining. Scale bar, 30 μm. (C–F) Primary cilia (arrow) protrude from the apical membrane of the alveolar epithelium. Immunofluorescent staining of primary cilia (arrow) in the normal lung using anti-GT335 (red) and anti-γ-tubulin antibody (green). Scale bar, 5 μm. (G) Alveolar epithelial cells of normal lung parenchyma have primary cilia. Immunofluorescence staining of primary cilia in the normal alveolar epithelium using anti-ARL13B antibody (red). Alveolar epithelium expressed by anti-cytokeratin antibody (green). Scale bar, 5 μm. (H) Endothelial cells of normal lung parenchyma have primary cilia. Immunofluorescence staining of primary cilia (anti-ARL13B, arrow) in the blood vessel (anti-CD34). (I) There are a few fibroblasts in the normal alveolar septae and primary cilia was detected in 5.11% of the fibroblasts present in the normal alveolar septae. Immunofluorescence staining of primary cilia (anti-ARL13B, arrow) in the fibroblast (anti-Vimentin). (J) Schematic for distributions of primary cilia (arrow) in the microanatomy of the alveolus.

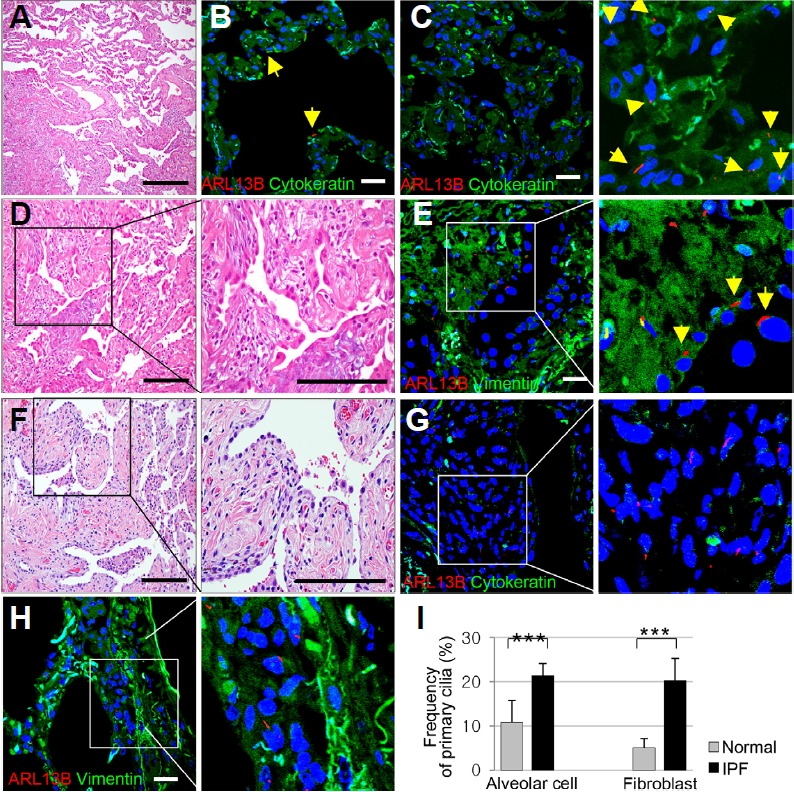

Increased number of primary cilia in IPF lung tissue

The hallmark pathological feature of UIP is a heterogeneous, variegated appearance with alternating areas of healthy lung, interstitial inflammation, fibroblastic foci, and honeycomb change (Visscher and Myers, 2006). We evaluated the distributions of primary cilia in these lesions in IPF tissue. Fibroblasts/ myofibroblasts show positive cytoplasmic expression of vimentin. The mean frequency of primary cilia was rarely changed in the healthy lung portions in IPF compared with the control (P = 0.414, Fig. 2B). In the portion where the alveolar wall begins to thicken, the frequency of primary cilia was increased (Fig. 2C). In interstitial inflammation and fibroblastic foci, the overlying alveolar epithelial cells were swollen or elongated (Figs. 2D and 2F). The frequency of primary cilia was significantly elevated in these hyperplastic alveolar epithelium compared with the control (Fig. 2E). In the hyperplastic alveolar epithelium, the mean frequency of primary cilia was 21.44 ± 2.56%, compared with 10.77 ± 5.01% in the control (P = 0.009, Fig. 2I). Fibroblastic foci were observed to be an area of active fibroblast proliferation within the lung interstitium (Figs. 2D and 2F), and were observed to have increased number of primary cilia (Figs. 2E and 2G). In the fibroblastic foci, the mean frequency of primary cilia was 20.30 ± 3.18% compared with 5.11 ± 2.01% in the control lung (P = 0.0005, Fig. 2I). The average length of the primary cilia was 3.62 ± 1.21 μm in IPF (p = 0.014).

Fig. 2. Distribution of primary cilia in IPF.

(A) Typical histologic finding of spatial heterogeneity in UIP with an abrupt transition from fibrosing alveolitis to normal lung. H&E staining. Scale bar, 30 μm. (B, C) Primary cilia (arrow) are rarely changed in the healthy alveoli of normal lung portions. In the portion where the alveolar wall begins to thicken, the frequency of primary cilia was increased. Immunofluorescence staining of primary cilia using anti-ARL13B antibody (red). Alveolar epithelium expressed by anti-cytokeratin antibody (green). Scale bar, 5 μm. (D) Overlying epithelium of fibrosing alveolitis consists of hyperplastic alveolar cells. Fibrosis predominates over inflammation. H&E staining. Scale bar, 30 μm. (E) Primary cilia (arrow) are detected in the hyperplastic alveolar cell. Immunofluorescence staining of primary cilia in the hyperplastic alveolar cell using anti-ARL13B (red). Fibroblastic foci expressed by anti-vimentin antibody (green). Scale bar, 5 μm. (F) Fibrosis comprises mainly dense eosinophilic collagen deposition. There are fibroblastic foci in which fibroblasts and myofibroblasts are arranged in a linear fashion within a pale staining matrix. H&E staining. Scale bar, 30 μm. (G, H) Primary cilia in active fibroblast within the interstitium. Immunofluorescence staining of primary cilia using anti-ARL13B antibody (red). Fibroblastic foci expressed by anti-vimentin antibody (green). Scale bar, 5 μm. (I) The average frequency of primary cilia in alveolar epithelial cells (10.77% in normal and 21.44% in IPF) and fibroblasts (5.11% in normal and 20.30% in IPF) of IPF compared with that of normal lung. ***P < 0.001 (t-test).

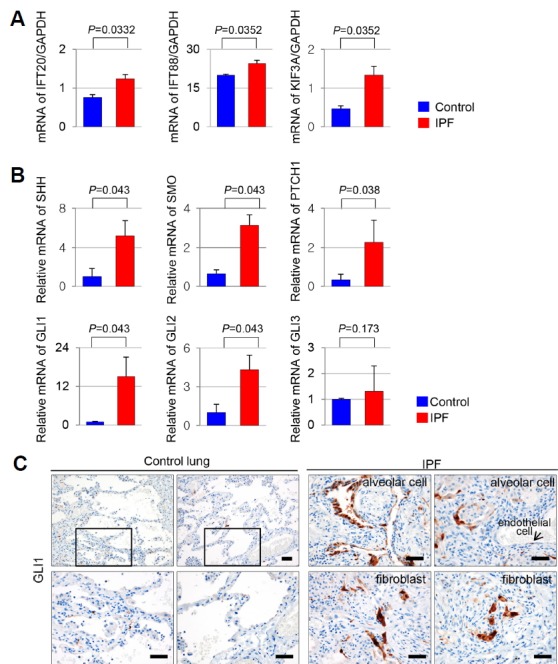

Increased ciliogenesis contributes to upregulation of the SHH signaling in IPF lung tissue

To determine whether an increased number of primary cilia is associated with aberrant activation of ciliogenesis in IPF, we examined the expression levels of genes involved in ciliogenesis. The expression levels of IFT20, IFT88 and KIF3A mRNA were increased in IPF (Fig. 3A). This result indicates that the increase in the number of primary cilia is due to increased ciliogenesis.

Fig. 3. Altered mRNA expression levels of the ciliogenesis and SHH signaling genes in IPF.

(A) The genes associated with ciliogenesis, IFT20, IFT88, and KIF3A were upregulated in IPF compared with control (IFT20, P = 0.0332; IFT88, P = 0.0352; KIF3A, P = 0.0352). (B) The gene expression of SHH, SMO, PTCH1, and transcription factors GLI1 and GLI2 was increased in IPF compared with control (SHH, P = 0.043; SMO, P = 0.043; PTCH1, P=0,038; GLI1, P = 0.043; GLI2, P = 0.043). mRNA levels of GLI3 did not significantly differ between IPF and control (GLI3, P = 0.173). mRNA levels of SHH, SMO, PTCH1, GLI1, GLI2, and GLI3 were normalized to levels of GAPDH. (C) In normal lung parenchyma, GLI1 positive cell was rarely detected. While, nuclear expression of GLI1 was markedly increased in alveolar cells, fibroblasts, and endothelial cells of IPF. Scale bar, 50 μm.

BoIanos et al. demonstrated that the SHH pathway is activated in IPF lungs and that SHH may contribute to IPF pathogenesis by increasing the proliferation, migration, extracellular matrix production, and survival of fibroblasts (Bolanos et al., 2012; Cigna et al., 2012). Based on their findings, we investigated whether increased ciliogenesis of alveolar epithelial cells and fibroblastic foci induces upregulation of SHH signals. We quantified the mRNA expression of the SHH signaling components using Quantitative Real-time Polymerase Chain Reaction (qRT-PCR) in both IPF and control lung tissue. mRNA levels of SHH, the coreceptor SMO, the receptor PTCH1, and the transcription factors GLI1 and GLI2 were upregulated in IPF compared with control (P < 0.05). mRNA levels of GLI3 did not significantly differ between IPF and control (Fig. 3B). In addition, we identified GLI1 positive cells using immunostain. The nuclear localization of GLI1 was observed mainly in alveolar epithelia and fibroblasts, while In normal lung parenchyma, GLI1 positive cell was rarely detected in control normal lung (Fig. 3C).

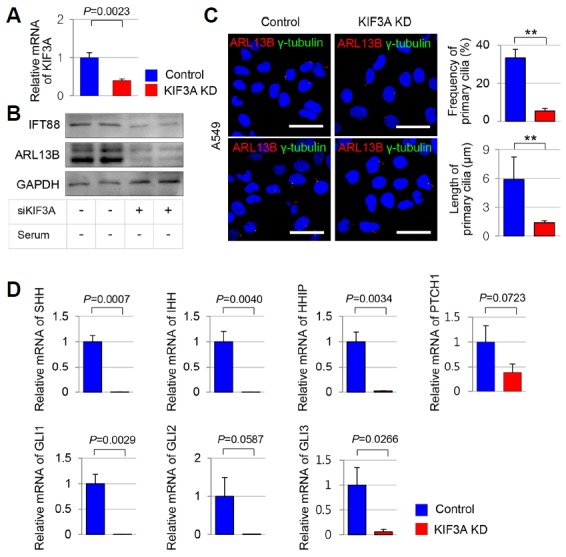

Inhibition of ciliogenesis contributes to downregulation of the SHH signaling in human alveolar epithelial cells

Based on our findings in IPF tissues, we have shown that primary cilia are involved in aberrant activation of SHH signaling in IPF pathogenesis in vitro. First, to determine whether alterations in ciliogenesis in alveoli directly affect SHH signaling, we generated alveolar epithelial cell lines, A549 that harbor a loss of primary cilia. We suppressed ciliogenesis in A549 cells using RNA interference of KIF3A, which encodes a subunit of the heterotrimeric motor protein, kinesin-2 required for assembly of the primary cilium (Marszalek et al., 2000). KIF3A-knockdown A549 cells showed a marked reduction of KIF3A mRNA levels (P = 0.0023)(Fig. 4A). The expression levels of IFT88 and ARL13B protein were decreased in KIF3A-knockdown A549 (Fig. 4B). KIF3A-knockdown A549 showed markedly decreased numbers of primary cilia compared with wild-type A549 (Fig. 4C). The frequency of primary cilia was 33.40 ± 4.47% in wild-type A549 and 7.17 ± 2.40% in KIF3A-knockdown A549 (p < 0.001). The average length of the primary cilia was 5.876 ± 2.35 μm in wild-type A549 and 1.376 ± 0.22 μm in KIF3A-knockdown A549 (p < 0.001). These results indicate that the formation of primary cilia in A549 cells was inhibited by siRNA KIF3A.

Fig. 4. Altered mRNA expression levels of the SHH signaling genes in human alveolar epithelial cells with defective KIF3A-mediated ciliary loss.

(A) KIF3A-knockdown A549 cells showed a marked reduction of KIF3A mRNA levels (P = 0.0023). (B) Western blot analysis was performed to detect IFT88 and ARL13B protein levels in KIF3A-knockdown A549 and wild-type control. GAPDH served as the loading control. serum (−); serum-starved condition. (C) Immunofluorescent staining of primary cilia using anti-GT335 (red) with anti-γ-tubulin (green) in KIF3A-knockdown A549 and wild-type control cells. Scale bar, 10 μm. The average frequency and the average length of primary cilia in KIF3A-knockdown A549 and wild-type control. (D) The gene expression of SHH, IHH, HHIP, GLI1, and GLI3 was decreased in A549 cells with ciliary loss (SHH, P = 0.0007; IHH, P = 0.0040; HHIP, P = 0.0034; GLI1, P = 0.0029; GLI3, P = 0.0266). mRNA levels of PTCH1 and GLI2 did not significantly differ between KIF3A-knockdown A549 and wild-type control (PTCH1, P = 0.0723; GLI2, P = 0.0587). mRNA levels of SHH, IHH, HHIP, PTCH1, GLI1, GLI2, and GLI3 were normalized to levels of GAPDH.

Next, we examined gene expression of the SHH signaling in A549 cells with deleted primary cilia. mRNA expression levels of SHH, IHH, HHIP, GLI1 and GLI3 were downregulated in A549 with ciliary loss compared to A549 with intact primary cilia. PTCH1 and GLI2 mRNA expression levels did not change significantly in A549 cells with and without primary cilia (Fig. 4D). PTCH1 expression levels were reduced but not significant. This suggests that PTCH1, a receptor for SHH, is predominantly present in fibroblasts, so that PTCH1 may not change significantly in alveolar epithelial cells. Taken together, these findings indicate that loss of primary cilia leads to decreased SHH signaling in lung alveolar epithelial cells.

DISCUSSION

In the present study, we first investigated the characteristic changes in distribution, frequency and length of primary cilia in IPF compared to human normal lung tissue. Excessive ciliogenesis was found in the hyperplastic alveolar epithelium and fibroblastic foci of IPF, but the activation of primary cilia was rarely found in normal lung tissue. The primary cilia of lung have been demonstrated by Jain et al. (2010). They showed that the primary cilia, which are rarely observed in normal airway epithelium, are detected after injury. These findings indicate that the primary cilia play a critical role in the development and repair of airway epithelium. Trempus et al. (2017) demonstrated that the primary cilia are necessary for the airway remodeling by mediating calcium flux and SHH signaling. They suggest that the effect of primary cilia in airway smooth muscle cells contraction is only partly mediated through SHH signaling and other signalings, such as calcium flux are involved in more portions. We showed the upregulation of the SHH signaling in IPF, which is associated with excessive ciliogenesis in both alveolar epithelium and fibroblasts. The difference between results is thought to be due to the difference in the progression degree of pulmonary fibrosis. In order for the smooth muscle to deposit in lung alveoli, fibrosis should proceed considerably. But in our study, there was no significant fibrotic specimen in which smooth muscle was deposited in lung alveoli. Because primary cilia can affect multiple signaling pathways, including the Wnt (Lancaster et al., 2011) and Hedgehog pathway (Wong et al., 2009) that are implicated in diseases, excessive ciliogenesis results in morphological and/or functional changes of affected cells or organs. Recent studies have shown that SHH signaling has been implicated in lung fibrosis (Yang et al., 2013) and IPF (Bolanos et al., 2012). Key components of the SHH signaling with known roles in fibrogenesis localize to the primary cilia (Seeger-Nukpezah and Golemis, 2012). We showed the upregulation of the SHH signaling in IPF, which is associated with excessive ciliogenesis. However, direct association between excessive ciliogenesis and cell fibrosis has not been demonstrated. Some ciliopathies, such as polycystic kidney disease, have been associated with fibrosis (Chang et al., 2006; Piontek et al., 2007). Thus, primary cilia might be affected during fibrosis and/or conversely ciliary changes might affect fibrogenesis. The precise mechanisms between ciliary changes and cell fibrosis should be further studied.

The current hypothesis regarding the pathogenesis of IPF is that after repeated epithelial cell injury, aberrant activation of alveolar epithelial cells provokes the migration, proliferation, and activation of mesenchymal cells with the formation of fibroblastic foci, leading to exaggerated accumulation of extracellular matrix with an irreversible destruction of the lung parenchyma (Harari and Caminati, 2010). Impaired communication between alveolar epithelial and mesenchymal cells may contribute to the pathophysiology of IPF (Horowitz and Thannickal, 2006). Our results demonstrate a new aspect of IPF pathogenesis that injury to alveolar epithelial cells, which is thought to be the key event for initiation of IPF, must lead to an aberrant activation of ciliogenesis, and the increased frequency and length of primary cilia contributes to upregulation of SHH signaling.

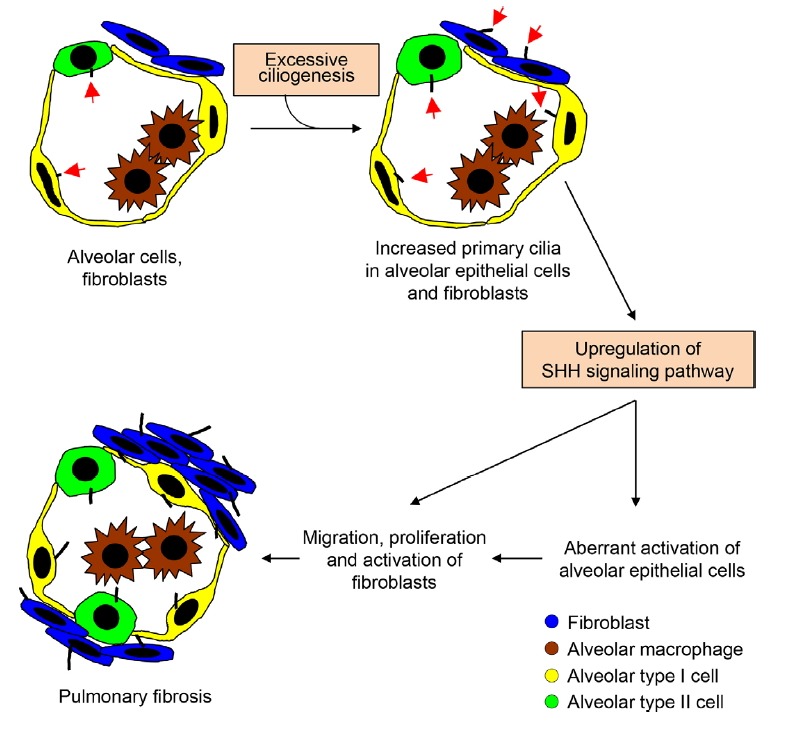

Taken together, we propose a unique insight for the pathogenesis of IPF as illustrated in Fig. 5; (1) chronic exposure to inciting or triggering agents or chronic aspiration in a susceptible host lead to excessive ciliogenesis, and (2) abnormally activated primary cilia causes upregulation of SHH signaling, which leads to (3) aberrant activation of alveolar epithelial cells and myofibroblasts as well as migration, proliferation, and activation of mesenchymal cells, (4) consequently leading to exaggerated accumulation of extracellular matrix with an irreversible destruction of the lung parenchyma.

Fig. 5.

Excessive ciliogenesis of primary cilia contributes to upregulation of SHH signaling in IPF lung tissue.

We could not establish the precise mechanisms for ciliary activation response to chronic lung injuries, because we did not unfortunately obtain in vivo mouse models for IPF. However, several studies have shown that upregulation of ciliogenic transcription factors is a general response to cell injury (Hellman et al., 2010). In the mammalian kidney, cilia length significantly increases in response to kidney injury (Verghese et al., 2008; 2009). In the pancreatic duct, increase cilia length has been associated with ductal injury (Ashizawa et al., 1999; Hamamoto et al., 2002). These studies demonstrated that injury-induced changes of cilia structure and function are a compensatory response to injury (Hellman et al., 2010). Maintenance of primary ciliary function requires highly regulated mechanisms of ciliogenesis, which can lead to increased or decreased ciliogenesis for compensation if altered. Therefore, we suggest that excessive ciliogenesis in IPF could be an adaptive response to injury.

We demonstrated a significant increase in primary cilia as well as upregulation of SHH signaling in IPF. These findings strong suggest that aberrant ciliogenesis of primary cilia might play an important role in the pathogenesis of IPF. This aspect of the pathogenesis of IPF associated with excessive ciliogenesis could be targeted to develop therapeutic strategies for IPF.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was supported by a grant from the Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Science, ICT & Future Planning (grant number: NRF-2015R1C1A1A02037434) and a grant from the Catholic Medical Center Research Foundation made in the program year of 2016.

REFERENCES

- Adams M, Smith UM, Logan CV, Johnson CA. Recent advances in the molecular pathology, cell biology and genetics of ciliopathies. J Med Genet. 2008;45:257–267. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2007.054999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashizawa N, Niigaki M, Hamamoto N, Niigaki M, Kaji T, Katsube T, Sato S, Endoh H, Hidaka K, Watanabe M, et al. The morphological changes of exocrine pancreas in chronic pancreatitis. Histol Histopathol. 1999;14:539–552. doi: 10.14670/HH-14.539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolanos AL, Milla CM, Lira JC, Ramirez R, Checa M, Barrera L, Garcia-Alvarez J, Carbajal V, Becerril C, Gaxiola M, et al. Role of Sonic Hedgehog in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2012;303:L978–990. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00184.2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardoso WV, Lu J. Regulation of early lung morphogenesis: questions, facts and controversies. Development. 2006;133:1611–1624. doi: 10.1242/dev.02310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang MY, Parker E, Ibrahim S, Shortland JR, Nahas ME, Haylor JL, Ong AC. Haploinsufficiency of Pkd2 is associated with increased tubular cell proliferation and interstitial fibrosis in two murine Pkd2 models. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2006;21:2078–2084. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfl150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cigna N, Farrokhi Moshai E, Brayer S, Marchal-Somme J, Wemeau-Stervinou L, Fabre A, Mal H, Leseche G, Dehoux M, Soler P, et al. The hedgehog system machinery controls transforming growth factor-beta-dependent myofibroblastic differentiation in humans: involvement in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Pathol. 2012;181:2126–2137. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2012.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbit KC, Aanstad P, Singla V, Norman AR, Stainier DY, Reiter JF. Vertebrate Smoothened functions at the primary cilium. Nature. 2005;437:1018–1021. doi: 10.1038/nature04117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding H, Zhou D, Hao S, Zhou L, He W, Nie J, Hou FF, Liu Y. Sonic hedgehog signaling mediates epithelial-mesenchymal communication and promotes renal fibrosis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012;23:801–813. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2011060614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eggenschwiler JT, Anderson KV. Cilia and developmental signaling. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2007;23:345–373. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.23.090506.123249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitch PM, Howie SE, Wallace WA. Oxidative damage and TGF-beta differentially induce lung epithelial cell sonic hedgehog and tenascin-C expression: implications for the regulation of lung remodelling in idiopathic interstitial lung disease. Int J Exp Pathol. 2011;92:8–17. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2613.2010.00743.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamamoto N, Ashizawa N, Niigaki M, Kaji T, Katsube T, Endoh H, Watanabe M, Sumi S, Kinoshita Y. Morphological changes in the rat exocrine pancreas after pancreatic duct ligation. Histol Histopathol. 2002;17:1033–1041. doi: 10.14670/HH-17.1033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harari S, Caminati A. IPF: new insight on pathogenesis and treatment. Allergy. 2010;65:537–553. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2009.02305.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassounah NB, Bunch TA, McDermott KM. Molecular pathways: the role of primary cilia in cancer progression and therapeutics with a focus on Hedgehog signaling. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18:2429–2435. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-0755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haycraft CJ, Banizs B, Aydin-Son Y, Zhang Q, Michaud EJ, Yoder BK. Gli2 and Gli3 localize to cilia and require the intraflagellar transport protein polaris for processing and function. PLoS Genet. 2005;1:e53. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0010053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hellman NE, Liu Y, Merkel E, Austin C, Le Corre S, Beier DR, Sun Z, Sharma N, Yoder BK, Drummond IA. The zebrafish foxj1a transcription factor regulates cilia function in response to injury and epithelial stretch. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:18499–18504. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1005998107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horowitz JC, Thannickal VJ. Epithelial-mesenchymal interactions in pulmonary fibrosis. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;27:600–612. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-957332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Q, Wu Y, Tang J, Zheng W, Wang Q, Nahirney D, Duszyk M, Wang S, Tu JC, Chen XZ. Expression of polycystins and fibrocystin on primary cilia of lung cells. Biochem Cell Biol. 2014;92:547–554. doi: 10.1139/bcb-2014-0062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huangfu D, Anderson KV. Cilia and Hedgehog responsiveness in the mouse. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:11325–11330. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0505328102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jain R, Pan J, Driscoll JA, Wisner JW, Huang T, Gunsten SP, You Y, Brody SL. Temporal relationship between primary and motile ciliogenesis in airway epithelial cells. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2010;43:731–739. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2009-0328OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lancaster MA, Schroth J, Gleeson JG. Subcellular spatial regulation of canonical Wnt signalling at the primary cilium. Nat Cell Biol. 2011;13:700–707. doi: 10.1038/ncb2259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litingtung Y, Lei L, Westphal H, Chiang C. Sonic hedgehog is essential to foregut development. Nat Genet. 1998;20:58–61. doi: 10.1038/1717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marszalek JR, Liu X, Roberts EA, Chui D, Marth JD, Williams DS, Goldstein LS. Genetic evidence for selective transport of opsin and arrestin by kinesin-II in mammalian photoreceptors. Cell. 2000;102:175–187. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00023-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ocbina PJ, Anderson KV. Intraflagellar transport, cilia, and mammalian Hedgehog signaling: analysis in mouse embryonic fibroblasts. Dev Dyn. 2008;237:2030–2038. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pepicelli CV, Lewis PM, McMahon AP. Sonic hedgehog regulates branching morphogenesis in the mammalian lung. Curr Biol. 1998;8:1083–1086. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(98)70446-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piontek K, Menezes LF, Garcia-Gonzalez MA, Huso DL, Germino GG. A critical developmental switch defines the kinetics of kidney cyst formation after loss of Pkd1. Nat Med. 2007;13:1490–1495. doi: 10.1038/nm1675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raghu G, Collard HR, Egan JJ, Martinez FJ, Behr J, Brown KK, Colby TV, Cordier JF, Flaherty KR, Lasky JA, et al. An official ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT statement: idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: evidence-based guidelines for diagnosis and management. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;183:788–824. doi: 10.1164/rccm.2009-040GL. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohatgi R, Milenkovic L, Scott MP. Patched1 regulates hedgehog signaling at the primary cilium. Science. 2007;317:372–376. doi: 10.1126/science.1139740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seeger-Nukpezah T, Golemis EA. The extracellular matrix and ciliary signaling. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2012;24:652–661. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2012.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trempus CS, Song W, Lazrak A, Yu Z, Creighton JR, Young BM, Heise RL, Yu YR, Ingram JL, Tighe RM, et al. A novel role for primary cilia in airway remodeling. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2017;313:L328–L338. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00284.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verghese E, Ricardo SD, Weidenfeld R, Zhuang J, Hill PA, Langham RG, Deane JA. Renal primary cilia lengthen after acute tubular necrosis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;20:2147–2153. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2008101105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verghese E, Weidenfeld R, Bertram JF, Ricardo SD, Deane JA. Renal cilia display length alterations following tubular injury and are present early in epithelial repair. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2008;23:834–841. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfm743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Visscher DW, Myers JL. Histologic spectrum of idiopathic interstitial pneumonias. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2006;3:322–329. doi: 10.1513/pats.200602-019TK. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson CW, Chuang PT. Mechanism and evolution of cytosolic Hedgehog signal transduction. Development. 2010;137:2079–2094. doi: 10.1242/dev.045021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong SY, Seol AD, So PL, Ermilov AN, Bichakjian CK, Epstein EH, Jr, Dlugosz AA, Reiter JF. Primary cilia can both mediate and suppress Hedgehog pathway-dependent tumorigenesis. Nat Med. 2009;15:1055–1061. doi: 10.1038/nm.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang IV, Coldren CD, Leach SM, Seibold MA, Murphy E, Lin J, Rosen R, Neidermyer AJ, McKean DF, Groshong SD, et al. Expression of cilium-associated genes defines novel molecular subtypes of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Thorax. 2013;68:1114–1121. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2012-202943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou D, Li Y, Zhou L, Tan RJ, Xiao L, Liang M, Hou FF, Liu Y. Sonic hedgehog is a novel tubule-derived growth factor for interstitial fibroblasts after kidney injury. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2014;25:2187–2200. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2013080893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]