Abstract

Individuals with sporadic colorectal cancer (CRC) frequently harbor abnormalities in the composition of the gut microbiome; however, the microbiota associated with precancerous lesions in hereditary CRC remains largely unknown. We studied colonic mucosa of patients with familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP), who develop benign precursor lesions (polyps) early in life. We identified patchy bacterial biofilms composed predominately of Escherichia coli and Bacteroides fragilis. Genes for colibactin (clbB) and Bacteroides fragilis toxin (bft), encoding secreted oncotoxins, were highly enriched in FAP patients’ colonic mucosa compared to healthy individuals. Tumor-prone mice cocolonized with E. coli (expressing colibactin), and enterotoxigenic B. fragilis showed increased interleukin-17 in the colon and DNA damage in colonic epithelium with faster tumor onset and greater mortality, compared to mice with either bacterial strain alone. These data suggest an unexpected link between early neoplasia of the colon and tumorigenic bacteria.

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is very common globally and develops through accumulation of colonic epithelial cell (CEC) mutations that promote transition of normal mucosa to adenocarcinoma. Around 5% of CRC occurs in individuals with an inherited mutation (1). One hereditary condition, familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP), is caused by germline mutation in the APC tumor suppressor gene. Individuals with FAP are born with their first mutation in the transition to CRC, and as somatic mutations accumulate, develop hundreds to thousands of colorectal polyps. The onset and frequency of polyp formation within families bearing the same APC gene mutation varies substantially (2), suggesting that additional factors contribute to disease onset, including components of the microbiome (3).

The colon contains trillions of bacteria that are separated from the colonic epithelium by a dense mucus layer. This mucus layer promotes tolerance to foreign antigens by limiting bacterial–epithelial cell contact and, thus, mucosal inflammatory responses. In contrast, bacterial breaches into the colonic mucus layer with, in some, biofilm formation fosters chronic mucosal inflammation (4–6).

We previously reported that biofilms on normal mucosa of sporadic CRC patients were associated with a pro-oncogenic state (6, 7), suggesting that biofilm formation is an important epithelial event influencing CRC. To test the hypothesis that biofilm formation may be an early event in the progression of hereditary colon cancer, we examined the mucosa of FAP patients at clinically indicated colectomy.

We initially screened surgically resected tissue preserved in Carnoy’s fixative from five patients with FAP and one with juvenile polyposis syndrome (table S1). Colon biopsies from individuals undergoing screening colonoscopy or surgical resections served as controls (n = 20, table S2). Polyps and macroscopically normal tissue were labeled with a panbacterial 16S ribosomal RNA (rRNA) fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) probe. Each FAP patient exhibited bacterial invasion through the mucus layer scattered along the colonic axis (Fig. 1A, table S3, and fig. S1). Unlike the continuous mucosal bio-films in sporadic CRC patients (6), FAP tissue displayed patchy bacterial mucus invasion (average length, 150 μm) on ~70% of the surgically resected colon specimens collected from four of six hereditary tumor patients. Biofilms were not restricted to polyps, nor did they display right colon geographic preference as observed in sporadic CRC (table S3 and figs. S1 and S2). Bio-films were not detected in the mucus layer of the FAP patient who received oral antibiotics 24 hours before surgery (table S1 and fig. S2).

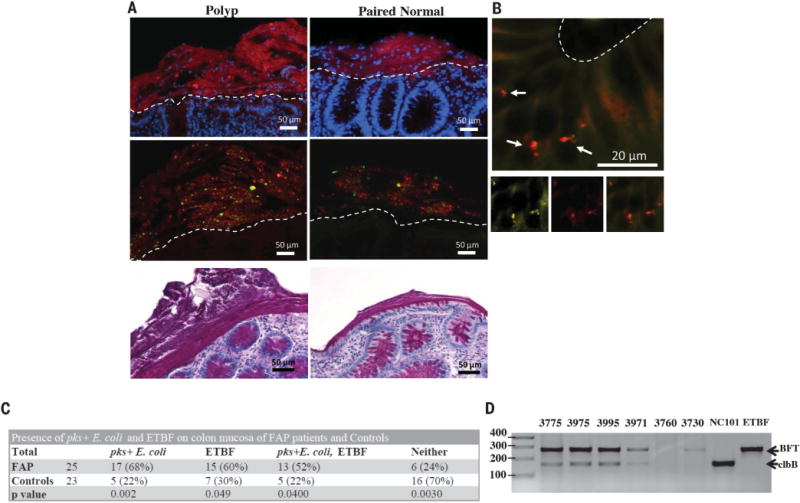

Fig. 1. Fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) and microbiology culture analysis of FAP mucosal tissues.

(A) Top panels: Representative FISH images of bacterial biofilms (red) on the mucosal surface of a FAP polyp and paired normal tissues counterstained with DAPI (4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole) nuclear stain (blue). Middle panels: Most of the biofilm composition was identified as B. fragilis (green) and E. coli (red) by using species-specific probes. Bottom panels: PAS (periodic acid–Schiff)–stained histopathology images of polyp and paired normal mucosal tissues demonstrating the presence of the mucus layer. Images were obtained at 40× magnification; scale bars, 50 μm. Dotted lines delineate the luminal edge of the colonic epithelial cells. Images are representative of n = 4 to 23 tissue samples per patient screened (at least 10 5-μm sections screened per patient). (B) Enterobacteriaceae (yellow) and E. coli (red) FISH probes on paired normal FAP tissue (100× magnification) revealing invasion into the epithelial cell layer at the base of a crypt (arrows). Bottom panels with insets of Enterobacteriaceae (bottom left panel) in yellow, E. coli (bottom middle panel) in red, and overlay (bottom right panel) confirming identification of the invasive species. Scale bar, 20 μm. Images are representative of n = 5 to 16 tissue samples per patient screened (at least 10 5-μm sections screened per patient). (C) FAP and control prevalence of pks+ E. coli and enterotoxigenic Bacteroides fragilis (ETBF). Chi-square P-values are shown that represent the difference in probability of detection of each bacterium in FAP versus control patients. (D) PCR detection of clbB (a gene in the pks island) and bft within laser-captured biofilms containing E. coli and B. fragilis from designated FAP patients (table S1) and controls (table S2; materials and methods). Data show a representative image from two independent experiments with two or three replicates per experiment performed.

Specimens with bacterial biofilms were further screened by additional 16S rRNA probes to recognize the major phyla detected in biofilms of sporadic CRC; namely, Bacteroides/Prevotella, Proteobacteria, Lachnospiraceae, and Fusobacteria (table S4). Notably, FAP biofilms were composed predominantly of mucus-invasive Proteobacteria (~60 to 70%) and Bacteroides (10 to 32%) (table S3). Fusobacteria were not detected, and Lachnospiraceae were rare (<3%) by quantitative FISH analysis (table S3).

Additional probe sets (table S4) identified the predominant biofilm members as E. coli and B. fragilis (Fig. 1A, bottom panels; table S3). Invasion of the epithelial cell layer by biofilm community members was detected in all patients harboring biofilms (Fig. 1B), a finding similar to that in sporadic CRC patients. Further, FISH of mucosal biopsies from ileal pouches or ano-rectal remnants of additional, longitudinally followed, postcolectomy FAP patients revealed biofilms in 36% and mucosal-associated E. coli or B. fragilis in 50% (table S5). Thus, E. coli and B. fragilis are frequent, persistent mucosal colonizers of the FAP gastrointestinal tract. Of note, semiquantitative colon mucosa bacterial cultures of ApcMinΔ716/+ mice (truncation at the 716 codon of Apc), a murine correlate of FAP, displayed similar enrichment of Bacteroides and Enterobacteriaceae compared to wild-type (WT) littermates, consistent with data reported for ApcMinΔ850/+ mice (fig. S3) (8). These results suggest that Apc mutations enhance mucosal bacterial adherence, altering the bacterial–host epithelial interaction.

Strong experimental evidence exists supporting the carcinogenic potential of molecular subtypes of both E. coli and B. fragilis (9, 10); the two dominant biofilm members identified in direct contact with host colon epithelial cells in our FAP patients. E. coli containing the polyketide synthase (pks) genotoxic island (encodes the genes responsible for synthesis of the colibactin genotoxin) induces DNA damage in vitro and in vivo along with colon tumorigenesis in azoxymethane (AOM)–treated interleukin-10 (IL-10)– deficient mice (10), whereas, enterotoxigenic Bacteroides fragilis (ETBF) induces colon tumorigenesis in ApcMin/+ mice (9). Human epidemiological studies have associated ETBF and pks+ E. coli with inflammatory bowel disease and sporadic CRC (10–13). Thus, we cultured banked frozen mucosal tissues from 25 FAP patients (two polyps and two normal tissues per patient when available, table S1) and 23 healthy individuals (mucosal sample from surgical resection or one ascending and one descending colon biopsy per colonoscopy subject, table S2) for the presence of pks+ E. coli and ETBF. The mucosa of FAP patients was significantly associated with pks+ E. coli (68%) and ETBF (60%) compared to healthy subject mucosa (22% pks+ E. coli and 30% ETBF) (Fig. 1C). There was no preferential association of ETBF or pks+ E. coli with polyp or normal mucosa from FAP patients. Typically, mucosal samples from individual patients were concordant for pks+ E. coli or ETBF (73% for pks+ E. coli, 59% for ETBF), similar to results for mucosal bft detection in sporadic CRC patients (13). Notably, pks+ E. coli and ETBF mucosal coassociation occurred at a higher rate (52%) than expected to occur randomly (40.8%) given the frequencies for the individual species (Fig. 1C). Increased mucosal coassociation also occurred in healthy control subjects (22% observed versus 6.6% expected) (Fig. 1C). Laser capture micro-dissection of mucosal biofilms from our initial FAP patients (fig. S2 and table S1) contained both bft and clbB as determined by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analysis, indicating that the carcinogenic subtypes of B. fragilis and E. coli, respectively, were present in the mucus layer in direct contact with the FAP epithelium (Fig. 1D). In contrast, neither virulence gene was detected in the mucus layer of control subject 3760 whereas bft was detected in the mucus layer of control subject 3730, consistent with our prior reported culture analysis of this sample (Fig. 1D) (13).

The high frequency of pks+ E. coli and ETBF cocolonization in FAP colons highlights the importance of understanding the potential effects of simultaneously harboring these two carcinogenic bacteria. Consequently, we used two murine models, AOM treatment without dextran sodium sulfate (see materials and methods) and ApcMinΔ716/+ mice to test the hypothesis that pks+ E. coli and ETBF cocolonization enhances colon tumorigenesis compared to monocolonization with either bacterium. The rate of spontaneous colon tumorigenesis is very low in both model systems.

Specific pathogen-free wild-type mice were treated with the carcinogen AOM and monoinoculated or coinoculated with canonical strains of pks+ E. coli (the murine adherent and invasive strain, NC101) and ETBF (strain 086-5443-2-2) (9, 10). Fecal ETBF or pks+ E. coli colonization was similar under monocolonization or cocolonization conditions, persisting until colon tumor formation was assessed at 15 weeks after colonization (fig. S4). Monocolonized (pks+ E. coli or ETBF) mice displayed few to no tumors. However, pronounced tumor induction occurred in cocolonized mice, including an invasive cancer, suggesting the requirement for both bacteria to yield oncogenesis (Fig. 2, A to C). Tumorigenesis required the presence of BFT and the colibactin genotoxin as in-frame deletions of the bft gene and the pks virulence island significantly decreased tumors (Fig. 2A).

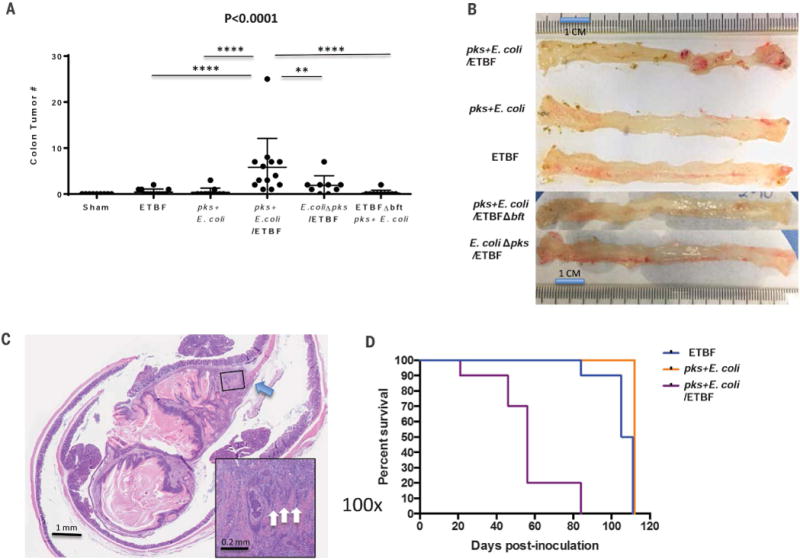

Fig. 2. Cocolonization by pks+ E. coli and ETBF increases colon tumor onset and mortality in murine models of CRC.

(A) Total colon tumor numbers detected in sham (n = 9), ETBF monocolonized (n = 12), pks+E. coli monocolonized (n = 11), pks+ E. coli/ETBF cocolonized (n = 13), E. coliΔpks/ETBF (n = 9), or pks+ E. coli/ETBFΔbft (n = 10) AOM mice at 15 weeks after colonization. Data indicate mean ± SEM. Overall significance was calculated with the Kruskal-Wallis test, and the overall P value is shown; Mann-Whitney U was used for two-group comparisons; **P = 0.016, ****P < 0.0001. (B) Representative colons of monocolonized (ETBF or pks+ E. coli), cocolonized (ETBF/pks+ E. coli), E. coliΔpks/ETBF, and pks+ E. coli/ETBFΔbft mice at 15 weeks after colonization of AOM-treated mice. Images are representative of n = 9 to 13 mice for each group. (C) H&E (hematoxylin and eosin) histopathology of an invasive adenocarcinoma in a cocolonized (pks+ E. coli/ETBF) AOM mouse at 15 weeks. Main image, 10× magnification; scale bar, 1 mm. Inset image, 100× magnification; scale bar, 0.2 mm. Blue arrow depicts the disruption of the muscularis propria by the invasive adenocarcinoma, and white arrows (inset) identify invading clusters of adenocarcinoma epithelial cells. (D) Kaplan-Meir survival plot of ApcΔ716Min/+ mice (n = 30) colonized with either ETBF (blue; n = 10), pks+ E. coli (orange; n = 10), or cocolonized with pks+ E. coli and ETBF (purple; n = 10). Cocolonization significantly (P < 0.0001) increased the mortality rate. Statistics were analyzed with the log-rank test. All surviving mice (n = 19) were harvested at 110 days.

ApcMinΔ716/+mice cocolonized with ETBF and pks+ E. coli exhibited enhanced morbidity with rapid weight loss and significantly increased mortality (P < 0.0001) [loss of 80% of the mice (n = 8) by 8 weeks and the remaining 20% (n = 2) at 12 weeks after colonization]. In contrast, 90% (n = 9) and 100% (n = 10) of mice monocolonized with ETBF or pks+ E. coli, respectively, survived 15 weeks after colonization (Fig. 2D). The robust tumorigenesis of ETBF alone (at 15 weeks) and cocolonized mice (majority deceased by 8 weeks after colonization) was similar, whereas tumor numbers were significantly increased in the cocolonized cohort compared to pks+ E. coli alone (fig. S5). Notably, at early time points, inflammation was increased in the cocolonized cohort compared to either ETBF or pks+ E. coli alone (fig. S5). Together these results suggest that the significant increase in colon inflammation and early tumorigenesis in the cocolonized mice contributed to their earlier mortality in the ApcMin/+ mouse model.

Consistent with enhanced tumorigenesis, histopathological analysis revealed significantly increased colon hyperplasia and mucosal micro-adenomas in cocolonized AOM-treated mice compared to monocolonized mice (Fig. 3A and fig. S6A). However, histopathology scoring revealed modest differences in inflammation over time (4 days to 15 weeks) in mono- and cocolonized AOM mice (Fig. 3B and fig. S6B). Thus, overall inflammation did not seem to explain differential tumor induction. To determine if the type of inflammation contributed to differences in tumorigenesis, we analyzed lamina propria immune-cell infiltrates of monocolonized and cocolonized wild-type AOM mice by flow cytometry. Our general lymphoid panel revealed a marked B cell influx across all colonization groups (Fig. 3C) but no significant differences in the proportion of infiltrating T cells (CD4, CD8, or γδ T cells) and myeloid populations between monocolonized and cocolonized AOM mice (Fig. 3C) either at the acute (1-week) or chronic (3-week) stage of infection.

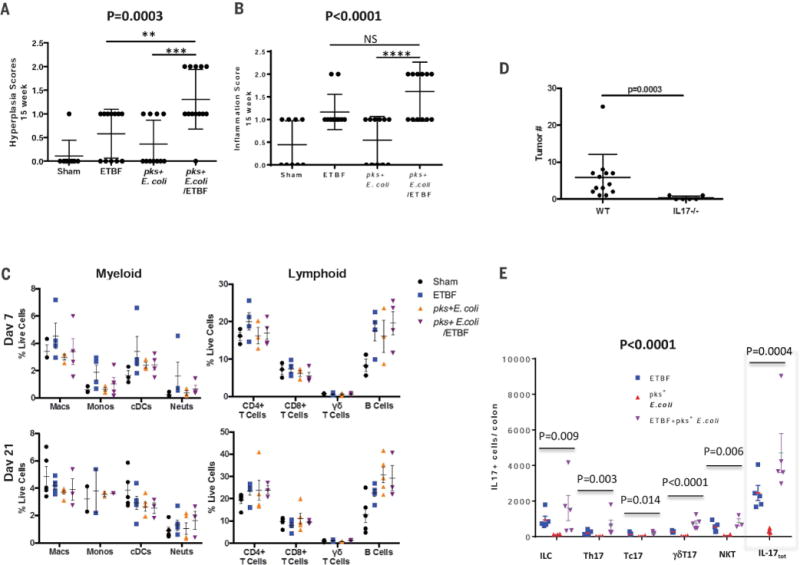

Fig. 3. IL-17–induced inflammation is necessary for bacterial-driven tumorigenesis.

(A) Histologic hyperplasia and (B) inflammation scores of 15-week AOM sham (n = 9), ETBF monocolonized (n = 12), pks+ E. coli monocolonized (n = 11), or pks+ E. coli/ETBF cocolonized (n = 13) mice. Data represent mean ± SEM of three independent experiments. For (A) and (B), overall significance was calculated by using the Kruskal-Wallis test, and the overall P value is shown; Mann-Whitney U was used for two-group comparisons; **P = 0.01, ***P = 0.0014, ****P = 0.0006; NS, not significant. (C) Myeloid and lymphoid lamina propria immune cell infiltrates plotted as percentage of live cells in AOM mice at day 7 (top panels) and day 21 (bottom panels) after colonization. Data represent mean ± SEM of three independent experiments (total three to five mice per group). (D) Total tumor numbers detected in IL-17–deficient AOM-treated mice (IL17−/−) versus wild-type AOM mice (WT). Both mouse strains were cocolonized with pks+ E. coli and ETBF and tumors assessed at 15 weeks. Data represent mean ± SEM of two or three independent experiments (total 6 to 13 mice per group). Significance calculated by the Mann-Whitney U test represents differences between the non-normally distributed colon tumors in the independent mouse groups. (E) IL-17–producing cell subsets and total number of IL-17–producing (IL-17tot) cells per colon harvested from germ-free C57BL/6 mice monocolonized with pks+ E. coli or ETBF or cocolonized with pks+ E. coli and ETBF for up to 60 hours. Data represent mean ± SEM of two independent experiments (total 3 to 5 mice per group). Overall significance across IL-17–producing cell types was calculated by using two-way analysis of variance testing based on log-transformed data (bold P value). For each cell subset and total number of IL-17–producing cells (gray dotted line box), the overall P value is shown and was calculated by using the Kruskal-Wallis test. Two-group cell subset and total number of IL-17–producing cell comparisons were analyzed by Mann-Whitney U test and are reported in table S7.

Of particular interest was IL-17, as the tumorigenic potential of ETBF in ApcMinΔ716/+ mice has been attributed, in part, to IL-17 (9). Because bft was necessary for synergistic tumor induction under cocolonization conditions (Fig. 2A), we tested the role of IL-17 in the cocolonized AOM model. Although IL-17 expression analysis by quantitative PCR revealed no significant difference in overall mucosal IL-17 mRNA levels between 15-week ETBF monocolonized and ETBF and pks+ E. coli cocolonized mice (fig. S7), cocolonization of IL-17–deficient AOM mice ablated tumorigenesis (Fig. 3D). To specifically test whether ETBF and pks+ E. coli cocolonization affected early colon mucosal IL-17 production, germ-free C57BL/6 mice were mono- or cocolonized and innate and adaptive lymphocyte subsets analyzed by flow cytometry. Germ-free mice cocolonized with ETBF and pks+ E. coli displayed a trend toward increase in total mucosal IL-17–producing cells when compared to monocolonized ETBF or pks+ E. coli mice, driven by both adaptive [T helper 17 (TH17)] and innate (particularly γδT17) cells (Fig. 3E and table S7). Although necessary for tumorigenesis (Fig. 3D), IL-17 alone appears insufficient to explain synergistic tumorigenesis in cocolonized mice because robust IL-17 induction by ETBF monocolonization (fig. S7) induces only meager colon tumorigenesis in AOM mice (Fig. 2A).

Because our general lymphoid panel revealed a marked B cell influx across all colonization groups (Fig. 3C), we profiled the secretory immunoglobulin A (IgA) response by IgA enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) using stool collected 4 weeks after colonization from AOM mice. Cocolonized mice had a significantly more robust IgA response to pks+ E. coli than mice monocolonized with pks+ E. coli, whereas the fecal anti-ETBF IgA response was similar under mono- and cocolonization conditions (Fig. 4A). Thus, the increased fecal IgA response was specific to pks+ E. coli in mice cocolonized with ETBF, suggesting that cocolonization enhanced mucosal exposure to pks+ E. coli.

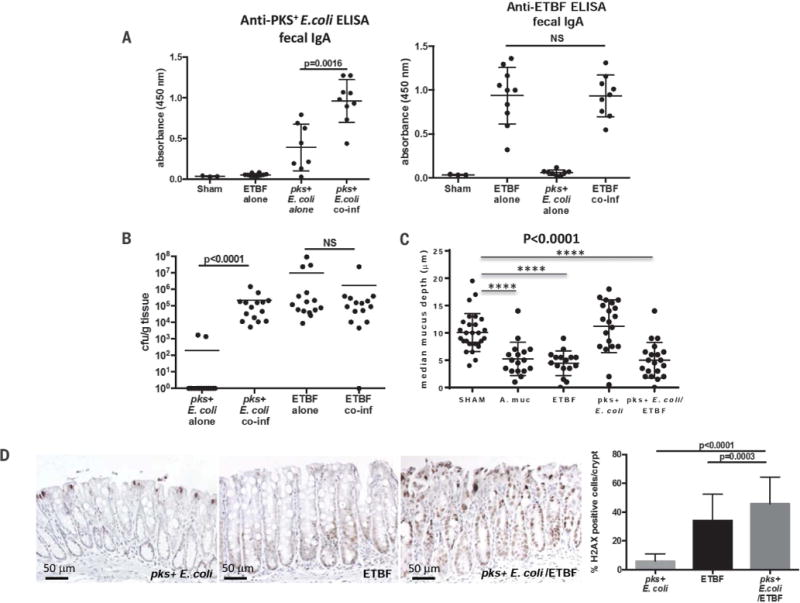

Fig. 4. ETBF enhances pks+ E. coli colonization and colonic epithelial cell DNA damage.

(A) ELISA results showing anti-pks+ E. coli (NC101) IgA and anti-ETBF (86-5443-2-2) IgA present in fecal supernatants from wild-type AOM mice under the designated colonization conditions for 4 weeks. Data represent mean ± SEM of three independent experiments (total 3 to 10 mice per group). (B) Colonization of distal colon mucosae by pks+ E. coli and ETBF under mono- and cocolonization conditions at 4 weeks in AOM mice. Data represent mean of three independent experiments (total of 15 mice per group). (C) Mucus depth (μm) of HT29-MTX-E12 monolayers under the designated colonization conditions. Data represent mean ± SEM of three independent experiments. A. muc, Akkermansia muciniphila. (D) Representative images of γ-H2AX immunohistochemistry of distal colon crypts from AOM mice (five mice per condition) mono- or cocolonized with pks+ E. coli and ETBF for 4 days with quantification (right panel) of γ-H2AX–positive cells displayed as percentage positive per crypt (see materials and methods). Data represent mean ± SEM of three independent experiments. For (A), (B), and (D), significance was calculated with the Mann-Whitney U test for two-group comparisons; for (C), overall significance was calculated with the Kruskal-Wallis test and the overall P value is shown; Mann-Whitney U was used for two-group comparisons; ****P < 0.0001.

Although fecal colonization of both pks+ E. coli and ETBF was equivalent under both mono- and cocolonization conditions (fig. S4), quantification of mucosal-adherent ETBF and pks+ E. coli revealed a marked increase in mucosal-adherent pks+ E. coli under cocolonization conditions compared to pks+ E. coli monocolonization (Fig. 4B). Hence, under monocolonization conditions, pks+ E. coli is largely cultivatable only from the colon lumen whereas in the presence of ETBF, pks+ E. coli colonizes the mucosa at high levels (103 to 106 colony-forming units per gram of tissue). Using Muc-2–producing HT29-MTX-E12 monolayers in vitro, we tested the impact of pks+ E. coli and ETBF on mucus. Although pks+ E. coli colonization alone had no impact on mucus depth, monolayer colonization with ETBF alone or cocolonized with pks+ E. coli significantly reduced mucus depth similar to colonization with A. muciniphila a known human colonic mucin-degrading bacterium (Fig. 4C). These results suggest that mucus degradation by ETBF promotes enhanced pks+ E. coli colonization. Such a shift in the bacterial niche of pks+ E. coli would facilitate the delivery of colibactin, the DNA-damaging toxin released by pks+ E. coli, to colon epithelial cells. Consistent with this hypothesis, γ-H2AX immunohistochemistry revealed significantly enhanced DNA damage in the colon epithelial cells of AOM mice cocolonized with pks+ E. coli and ETBF compared to monocolonized (pks+ E. coli or ETBF) mice (Fig. 4D). Further, mice cocolonized with ETBF and E. coliΔpks displayed similarly enhanced mucosal colonization with the E. coli strain (fig. S8) but reduced tumors and no increase in DNA damage or IL-17 (Fig. 2A and fig. S9, A and B, respectively). Lastly, persistent cocolonization of AOM-treated mice with the mucin-degrading A. muciniphila and pks+ E. coli did not enhance, but rather reduced, the modest colon tumorigenesis (fig. S10, A and B) induced by pks+ E. coli monocolonization. These results suggest that mucus degradation alone was insufficient to promote pks+ E. coli colon carcinogenesis in AOM mice.

Taken together, these data suggest that co-colonization with ETBF and pks+ E. coli, found in more than half of FAP patients (in contrast to less than 25% of controls), promotes enhanced carcinogenesis through two distinct but complementary steps: (i) mucus degradation enabling increased pks+ E. coli adherence, inducing increased colonic epithelial cell DNA damage by colibactin (Fig. 4D and fig S9); and (ii) IL-17 induction promoted, primarily, by ETBF with early augmentation by pks+ E. coli cocolonization (Fig. 3, D and E, and table S7). We propose that together these mechanisms yield cooperative tumor induction in AOM mice cocolonized with ETBF and pks+ E. coli.

ETBF and pks+ E. coli commonly colonize young children worldwide. Thus, our results suggest that persistent cocolonization in the colon mucosa from a young age may contribute to the pathogenesis of FAP and potentially even those who develop sporadic CRC because APC loss or mutation occurs in the vast majority of sporadic CRC. We note that pks+ E. coli are phenotypic and genotypic adherent and invasive E. coli (AIEC) (14). Despite this designation, derived primarily from in vitro cell culture experiments, the canonical pks+ E. coli strain (NC101) used in our experiments was only cultivatable from the colon lumen in the absence of concomitant ETBF colonization in our mouse model. This ETBF-dependent shift to marked mucosal pks+ E. coli colonization is consistent with our observations that ETBF and pks+ E. coli cocolonize FAP colon biofilms, where both bacteria invade and cocolonize the mucus layer throughout the FAP colon. These findings suggest that analysis of coexpression of bft and clbB may have value in general screening and potential prevention of CRC.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank K. Kinzler and B. Vogelstein for valuable discussions; K. Romans and L. Hylind for assistance with patient enrollment; and S. Besharati for assistance with histopathologic analyses. The data presented in this manuscript are tabulated in the main text and supplementary materials and methods. This work was supported by the Bloomberg Philanthropies and by NIH grants R01 CA151393 (to C.L.S., D.M.P.), K08 DK087856 (to E.C.W.), 5T32CA126607-05 (to E.M.H.), P30 DK089502 (Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine), P30 CA006973 (Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine), and P50 CA62924 (Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine). Funding was also provided through a research agreement with Bristol-Myers Squibb Co-International Immuno-Oncology Network-IION Resource Model, 300-2344 (to D.M.P.); Alexander and Margaret Stewart Trust (Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine); GSRRIG-015 (American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons to E.M.H.); The Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (NWO 825.11.03 and 016.166.089 to A.B.); and a grant from the Institute Mérieux (to C.L.S. and D.M.P.). D.M.P. discloses consultant relationships with Aduro Biotech, Amgen, Astra Zeneca, Bayer, Compugen, DNAtrix, Five Prime, GlaxoSmithKline, ImmuneXcite, Jounce Therapeutics, Neximmune, Pfizer, Rock Springs Capital, Sanofi, Tizona, Janssen, Merck, Astellas, Flx Bio, Ervaxx, and DNAX. D.M.P. receives research support from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Compugen, Ervaxx, and Potenza. D.M.P. is a scientific advisory board member for Immunomic Therapeutics. D.M.P. shares intellectual property with Aduro Biotech, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Compugen, and Immunomic Therapeutics. All other authors declare no competing interests. C.L.S., D.M.P., C.M.D., and E.C.W. are inventors on patent application PCT/US2014/055123 submitted by Johns Hopkins University that covers use of biofilm formation to define risk for colon cancer.

Footnotes

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

www.sciencemag.org/content/359/6375/592/suppl/DC1

Materials and Methods

References (15, 16)

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Fearon ER, Vogelstein B. Cell. 1990;61:759–767. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90186-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Giardiello FM, et al. Gastroenterology. 1994;106:1542–1547. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(94)90408-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dejea C, Wick E, Sears CL. Future Microbiol. 2013;8:445–460. doi: 10.2217/fmb.13.17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Swidsinski A, et al. Gut. 2007;56:343–350. doi: 10.1136/gut.2006.098160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Swidsinski A, Loening-Baucke V, Herber A. J Physiol Pharmacol. 2009;60(suppl 6):61–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dejea CM, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111:18321–18326. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1406199111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Johnson CH, et al. Cell Metab. 2015;21:891–897. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2015.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Son JS, et al. PLOS ONE. 2015;10:e0127985. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0127985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wu S, et al. Nat Med. 2009;15:1016–1022. doi: 10.1038/nm.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Arthur JC, et al. Science. 2012;338:120–123. doi: 10.1126/science.1224820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Prindiville TP, et al. Emerg Infect Dis. 2000;6:171–174. doi: 10.3201/eid0602.000210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Prorok-Hamon M, et al. Gut. 2014;63:761–770. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2013-304739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Boleij A, et al. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;60:208–215. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciu787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Martinez-Medina M, et al. J Clin Microbiol. 2009;47:3968–3979. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01484-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.