Abstract

Diabetic nephropathy (DN) is characterized by interstitial inflammation and fibrosis, which is the result of chronic accumulation of extracellular matrix produced by activated fibroblasts in the renal tubulointerstitium. Renal proximal tubular epithelial cells (PTECs), through the process of epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT), are the source of fibroblasts within the interstitial space, and loss of E-cadherin has shown to be one of the earliest steps in this event. Here, we studied the effect of the anti-diabetic agent sodium tungstate (NaW) in the loss of E-cadherin induced by transforming growth factor (TGF) β-1, the best-characterized in vitro EMT promoter, and serum from untreated or NaW-treated diabetic rats in HK-2 cell line, a model of human kidney PTEC. Our results showed that both TGFβ-1 and serum from diabetic rat induced a similar reduction in E-cadherin expression. However, E-cadherin loss induced by TGFβ-1 was not reversed by NaW, whereas sera from NaW-treated rats were able to protect HK-2 cells. Searching for soluble mediators of NaW effect, we compared secretion of TGFβ isoforms and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)-A, which have opposite actions on EMT. One millimolar NaW alone reduced secretion of both TGFβ-1 and -2, and stimulated secretion of VEGF-A after 48 h. However, these patterns of secretion were not observed after diabetic rat serum treatment, suggesting that protection from E-cadherin loss by serum from NaW-treated diabetic rats originates from an indirect rather than a direct effect of this salt on HK-2 cells, via a mechanism independent of TGFβ and VEGF-A functions.

Diabetes, a progressive metabolic disease characterized by chronic hyperglycemia and disturbances of carbohydrate, fat, and protein metabolism, is the major cause of end stage renal disease, with ~30% of diabetic patients developing nephropathy after years of uncontrolled hyperglycemia (Vallon, 2011). Diabetic nephropathy (DN) is characterized by fibrosis, a progressive and generally irreversible process leading to renal failure (Lindenmeyer et al., 2007), as a consequence of the chronic accumulation of extracellular matrix in the renal tubulointerstitium (Liu, 2010). Enhanced production of extracellular matrix proteins is achieved through activation of resident renal fibroblasts, but it also occurs through appearance of de novo myofibroblasts generated during epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT), a process by which fully differentiated epithelial cells lose their epithelial characteristics and acquire migratory mesenchymal properties (Liu, 2010). One of the earliest events in EMT is the loss of epithelial adhesion, which occurs after down-regulation of components of cell-to-cell contact, such as E-cadherin from adherens junctions (Hong et al., 2013).

Although glomerular dysfunction is considered the triggering factor in DN, deterioration of renal function also correlates with tubular alterations, especially in proximal tubular epithelial cells (PTECs) (Vallon, 2011). EMT from PTECs has demonstrated to be the source of matrix-producing fibroblasts in an in vivo model of unilateral ureteral obstruction, accounting for up to 36% of fibroblasts within the interstitial space (Iwano et al., 2002). The role of EMT in DN has been determined in animal models (Burns et al., 2006; Holian et al., 2008; Noh et al., 2009) and human kidney biopsies (Rastaldi et al., 2002; Simonson, 2007; Yu et al., 2014).

Diabetes is recognized as an inflammatory disease and progressive renal fibrosis is induced by diverse inflammatory mediators (Liu, 2010). One of them, transforming growth factor-β1 (TGF-β1), is as a key factor in promoting renal fibrosis, and levels of TGF-β1 predict renal end point in patients with type 2 diabetes (Wong et al., 2013). TGF-β1 is a potent in vitro EMT inducer, being able to complete the entire course of EMT, starting with down-regulation of E-cadherin (Liu, 2010). TGF-β2 and TGF-β3 isoforms also participate in renal fibrogenesis (Yu et al., 2003). Vascular endothelial growth factor isoform A (VEGF-A) is involved in the pathology of DN, and a reduction of VEGF-A expression in human biopsies with established DN is associated with loss of peritubular capillary density and hypoxia (Lindenmeyer et al., 2007). In this context, VEGF-A supplementation suppresses EMT and ameliorates tubulointerstitial damage in experimental animal models (Lian et al., 2011; Hong et al., 2013).

Sodium tungstate (NaW) is an inorganic salt that exerts potent anti-diabetic and anti-obesity activity in animal models of type 1 and type 2 diabetes, being administered orally (ad libitum, in tap water) as a non-invasive easy-to-use agent (Barberà et al., 2001; Muñoz et al., 2001; Bertinat et al., 2015). NaW effectively normalizes blood glucose and triglycerides levels, among several beneficial effects (Barberà et al., 2001; Muñoz et al., 2001; Bertinat et al., 2015). NaW activity depends mostly on mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathways, especially extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) 1/2 activation (Domínguez et al., 2003; Bertinat et al., 2015). In the diabetic rat kidney, NaW treatment completely reverses the most characteristic histopathological feature, the so-called Armanni-Ebstein lesion, which is an extensive glycogen deposition in tubular cells (Barberà et al., 2001). No other information addressing the effects of NaW in renal cells is available to date. NaW treatment has been shown to restore the number and function of immune cells as well as the immunoglobulin level in diabetic rats (Palanivel and Sakthisekaran, 2002). Given that the effect of NaW on proximal tubule EMT in the context of DN is unknown, we further assessed the mechanisms involving NaW protective effects in diabetes.

This is the first report that explores the action of NaW on EMT in vitro. For this purpose, we analyzed E-cadherin expression as a hallmark of EMT in the human renal proximal cell line HK2, using TGFβ1 as an inducer of EMT. Interestingly, 0.1–1 mM NaW had no effect on E-cadherin down-regulation induced by TGFβ1. However, when we studied the serum from NaW-treated type 1 diabetic rats, we detected a consistent conservation of E-cadherin expression, compared to the serum from untreated diabetic rats. Looking for the indirect effectors mediating NaW effect, we studied the secretion of inflammatory mediators by HK2 cells. 1 mM, but not 0.1 mM NaW induced VEGF-A and inhibited TGFβ-1 and -2 secretion, whereas this pattern was not reproduced by serum from NaW-treated or untreated rats. These results indicate that diabetes induces the secretion of toxic serum factors that negatively affect E-cadherin expression in renal proximal tubule cells, and that NaW treatment is able to reverse this condition. Furthermore, our results also suggest that the protective effect of this anti-diabetic drug on E-cadherin loss in HK-2 cells is indirect, and it does not depend on TGFβ1 or VEGF-A.

Materials and Methods

Experimental animals

Adult male Sprague-Dawley rats (~250 g) were maintained on a standard diet with free access to water. They were randomly divided into two different groups of 10 individuals each: control and diabetic. Type 1 diabetes was induced by a single intravenous injection of streptozotocin (STZ; 60 mg/kg body weight) (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO) in 0.1 M citrate buffer, pH 4.5, and it was considered time zero in the study. Control rats received buffer alone. Diabetes was monitored by determination of glycemia using a glucose meter. After 2 months, control and diabetic rats were randomly divided into two subgroups, and one subgroup in each group was treated with 2 g/L of NaW (EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA) in the drinking water ad libitum, to complete the four experimental groups: untreated control, treated control, untreated diabetic, and treated diabetic, with five individuals each. After 4 months of diabetes induction (and 2 months of NaW treatment), a bigger sample of blood was taken from the caudal vein and serum was prepared. Overnight urine (8 h) was also collected. Aliquots of serum and urine were stored at −80°C until use. Glucose (#1400106, Wiener Lab, Rosario, Argentina) and triglycerides (#1780111, Wiener Lab, Rosario, Argentina) were determined by enzymatic methods. Animals were not sacrificed because the study was originally intended to analyze NaW effect in the long term (8 months). All experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Universidad Austral de Chile.

Cell culture

The human proximal tubular cell line HK2 was obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (CRL-2190). HK-2 cells were maintained in DMEM/Ham’s F12 medium (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA), supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum, 2 mM L-glutamine, 100 U/ml penicillin and 100 mg/ml streptomycin (Li et al., 2011). One day before the experiment, culture medium was replaced with DMEM/Ham’s F12 without serum supplementation. Cells were stimulated for 48 h with recombinant human TGFβ1 (240-B-002, R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) and/or 0.1–1 mM NaW. In experiments with co-incubation of TGFβ1 and NaW, cells were pre-incubated for 1 h with 0.1–1 mM NaW, and TGFβ1 was added in the continuous presence of the salt. In experiments with MAPK/ERK (PD98059) or phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) (LY294002) inhibitors (Cell Signaling #9000 and #9001, respectively, Danvers, MA), cells were pre-incubated for 1 h with 50 μM each, and 5 ng/ml TGFβ1 or 0.1–1 mM NaW were added in the continuous presence of the inhibitor. When the inhibitor, TGFβ1 and NaW were used together, cells were incubated with inhibitor for 1 h, then NaW was added for 1 h in the presence of the inhibitor, and finally TGFβ1 was added in the presence of the other two. In parallel, cells were incubated with 1%–10% of serum from control, diabetic, and NaW treated-control and diabetic rats for 48 h. Cell viability was checked with trypan blue staining at the end of the experiment. Culture medium was transferred to a tube, centrifuged at 1,000×g for 5 min, and store at −80°C for TGFβ and VEGF detection.

Antibodies

Rabbit anti-E cadherin and β-actin were from Santa Cruz Biotechnologies (sc:7870 and sc:47778-HRP, respectively, Santa Cruz, CA). Rabbit anti-phosphorylated ERK1/2 (Thr202/ Tyr204) and anti-total ERK1/2 were from Cell Signaling Technology Inc. (#4379 and #4695, respectively, Beverly, MA). Secondary antibodies were donkey anti-rabbit IgG HRP (Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA) and Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (Molecular probes, Eugene, OR).

Western blot

Cell homogenates were prepared with lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.4, 10 mM EGTA, 150 mM NaCl) plus 1% Triton X-100 and protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN). Fifteen microgram of total proteins were fractionated in 4%–12% SDS-PAGE, transferred to PVDF membranes and probed overnight with primary antibodies. Following incubation with a HRP-conjugated secondary antibody, reaction was developed using the Pierce ECL Western Blotting Substrate (Pierce Biotechnology, Rockford, IL).

Real-time RT-PCR

Total RNA was extracted from HK2 cells using TRIzol reagent, following the manufacturer’s instructions (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA). cDNA was synthesized from 2 μg of total RNA using MuLV reverse transcriptase (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA) and 0.5 μg oligo dT. For real time PCR we used specific primers for human E-cadherin (sense 5′ AGGCCAAGCAGCAGTACATT 3′, antisense 5′ GGGGGCTTCATTCACATCCA 3′), and β-actin as the reference gene (sense 5′ GACCAGAGCCTCGCCTTTGCC 3′, antisense 5′ CGATGCCGTGCTCGATGGGG 3′). Primers were annealed at 60°C and run for 40 cycles. Data was captured using Mastercycler ep realplex2 equipment and Mastercycler ep realplex software 2.2 (Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany).

TGFβ and VEGF-A detection

Cell culture medium was frozen at −80°C until time of Luminex analysis. The analytes measured in this study were part of two separate kits (VEGF-A was analyzed using the Milliplex Map Human Cytokine/Chemokine kit; and TGFβ-1, -2 and -3 were analyzed using the Milliplex Map TGFβ Magnetic Bead 3 Plex Kit; EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA). Analysis was carried out on the Luminex 200 instrument (Luminex Corp., Austin, TX), and data were analyzed by Milliplex Analyst software (VigeneTech Inc., Carlisle, MA).

Statistical analysis

Each experiment was performed three separate times. Data are expressed as the mean ± SD. Statistical analysis was performed with unpaired Student’s t test using GraphPad Prism, version 6.01. Data were considered statistically significant for P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Effect of NaW on TGFβ1-induced E-cadherin loss in HK2 cells

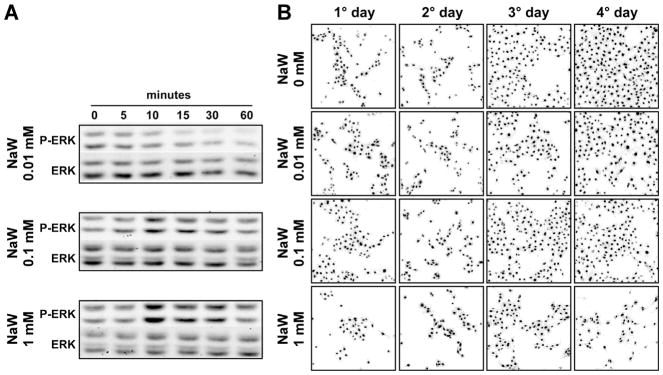

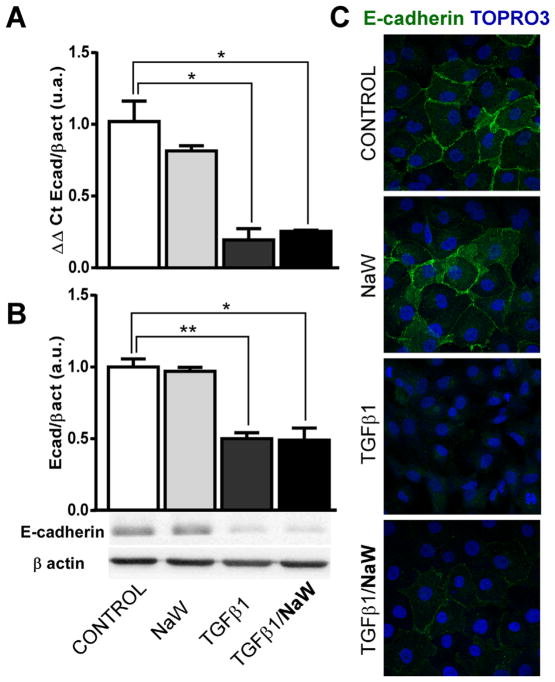

Given the relevance of TGFβ1 in the pathogenesis of renal fibrosis, and the fact that it is a well-described inducer of EMT, HK2 cells were stimulated with TGFβ1 to establish our control model. Taking into account that expression of E-cadherin is a marker of epithelial integrity, and also its loss is one of the earliest steps associated with EMT, we decided to study the expression of this adherens junction component. First of all, we established the best dose of NaW on HK2 cells, by studying ERK1/2 phosphorylation. In our hands, the best concentrations of NaW to induce ERK1/2 activation were 0.1 and 1 mM, but not 0.01 mM (Fig. 1A). However, a clear growth arrest was observed when cells were seeded in the presence of 1 mM NaW, as cell confluence was not reached even after 4 days of culture (Fig. 1B), although viability was not affected (data not shown). To this end, using this in vitro model of EMT, the effect of NaW on the expression of E-cadherin was studied by means of qPCR, Western blot and immunofluorescence. After 48 h of 5 ng/ml TGFβ1 treatment, HK2 cells showed a 75% reduction in the mRNA levels and 50% reduction in the protein levels of E-cadherin (Fig. 2A–B), in agreement with a poor detection of this protein in the membrane compartment by means of immunofluorescence (Fig. 2C). Despite NaW (0.1 or 1 mM) treatment being unable to inhibit the TGFβ1-induced down-regulation of E-cadherin at the mRNA and protein levels (Fig. 2A–B), it did partially inhibit the loss of E-cadherin localization at the membrane compartment (Fig. 2C). Incubation with NaW in the absence of TGFβ1 did not alter the expression or localization of E-cadherin (Fig. 2A–C). Only treatment with 1 mM NaW is shown, as no difference with 0.1 mM NaW was detected (data not shown).

Fig. 1.

Effect of NaW on ERK1/2 phosphorylation and proliferation in HK-2 cells. HK-2 cells were incubated 5 h in DMEM/F12 medium without serum supplementation, and then the ability of 0.01, 0.1, and 1 mM NaW on ERK1/2 phosphorylation was studied at 0, 5, 10, 15, 30. and 60 min by means of Western blot against phosphorylated and total ERK1/2 (A). In parallel, HK-2 cells were seeded at the same density in different dishes and allowed to attach in the presence of DMEM/F12 medium and serum. The next day, medium was replaced with basal DMEM/F12 medium and NaW was added to a final concentration of 0, 0.01, 0.1, and 1 mM. Each day, cells were fixed and stained with TOPRO3 for nuclei visualization. Images are representative of five different areas of each slide (B). n = 3.

Fig. 2.

NaW does not reverse TGFβ-1-induced E-cadherin loss in HK-2 cells. HK-2 cells were allowed to reach confluence and then serum-starved for 24 h. Cells were incubated with 5 ng/ml TGFβ-1 for 48 h, in the presence or absence of 1 mM NaW, as described in Materials and Methods. E-cadherin expression was studied by means of qRT-PCR (A), Western blot (B) and immunofluorescence (E-cadherin; TOPRO3 nuclear staining) (C). Each experiment was performed in triplicate and three separate times. *P< 0.05; **P < 0.01.

Effect of NaW on diabetic serum-induced E-cadherin loss in HK2 cells

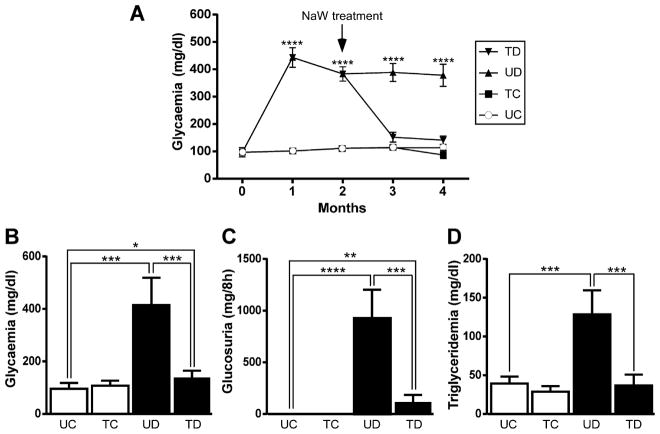

In vivo, the diabetic milieu is much more complex and TGFβ1 may not be the only injurious stimulus. Moreover, positive and negative interaction among factors may occur. The aim of using serum from diabetic rats was to explore the effect of this toxic, more physiological condition on EMT, and also to determine the in vivo effects of NaW. Using a glucose meter, glycemia was estimated weekly in all groups in order to verify the efficiency of diabetes induction and the effect of NaW in vivo. The diabetic group showed higher blood glucose levels from the first week after induction of diabetes (data not shown), and glycemia was elevated during the 4 months of experiment (Fig. 3A). NaW-treated diabetic rats showed a normalization of glycemia, whereas treated and untreated control rats remained normoglycemic during the entire course of the experiment (Fig. 3A). After 4 months, serum was obtained and glycemia was measured again by means of the glucose oxidase method. This quantitative method allowed us to determine that glycemia from treated diabetic rats was normalized, but still a difference of statistical significance was observed comparing with the untreated control (Fig. 3B). Other parameters, such as glucosuria and triglyceridemia (Fig. 3C–D, respectively) were also corrected by NaW treatment.

Figure 3.

Biochemical parameters of sera from untreated and NaW-treated, control and diabetic rats. Diabetes was induced as described in Materials and Methods. Rats were randomly divided in four groups: untreated control (UC), NaW-treated control (TC), untreated diabetic (UD), and NaW-treated diabetic (TD). With the moment of STZ-induction being “time zero,” NaW treatment was started 2 months later and lasted for another 2 months. Glycemia (mg/dl) was estimated using a glucose meter from the beginning of the experiment, and each weak (only the monthly values are shown) until the 4th month after diabetes induction (A). Serum was obtained at the end of the experiment, and glycemia (mg/dl) (B), glucosuria (mg(dl) (C), and triglyceridemia (mg/dl) (D) were determined by enzymatic methods. n = 5 animals in each group. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ****P < 0.0001.

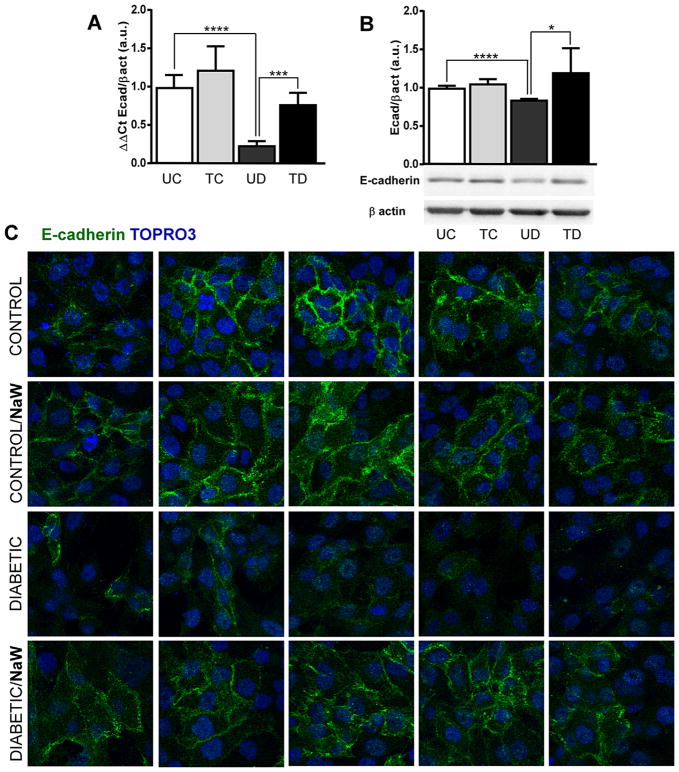

HK2 cells were cultured in the presence of high (10% and 5%), medium (2.5%), and low (1%) concentrations of serum from untreated control, NaW-treated control, untreated diabetic and NaW-treated diabetic rats, but only the 2.5% condition was used due to the low viability under the higher percentage of the serum from diabetic rats (data not shown). Even at 2.5% serum from diabetic rats, HK-2 cells survived for only 3 days (data not shown), indicating how toxic it was. Hence, the experiment was carried out with 2.5% serum for 48 h to make a direct comparison with the TGFβ1 treatment. Notably, the serum from diabetic rats induced the down-regulation of E-cadherin expression, with a 75% reduction in the mRNA levels (similar to the effect of TGFβ1), and a ~20% reduction in the protein levels (Fig. 4A–B). Furthermore, E-cadherin localization at the membrane compartment was almost totally lost after treatment with the serum from diabetic rats, compared to the serum from control rats (Fig. 4C). Interestingly, the serum from NaW-treated diabetic rats was unable to induce loss of E-cadherin expression at all levels (Fig. 4A–C). No differences were determined between the effect of sera from NaW-treated and untreated control rats. Since one of the main effects of NaW treatment is normalization of hyperglycemia, it is reasonable to consider the possibility that the deleterious effect of the diabetic serum was due to the higher glucose levels. However, cells were cultured in the presence of high glucose without any sign of cell death after 48 h (data not shown), and on the other hand, cells were incubated with diluted serum (2.5%) which makes a final glucose concentration of ~100 mg/dl of the untreated diabetic serum.

Figure 4.

Serum from NaW-treated diabetic rats prevents loss of E-cadherin expression in HK-2 cells. HK-2 cells were allowed to reach confluence and then serum-starved for 24 h. Cells were incubated with 2.5% serum from untreated control (UC), NaW-treated control (TC), untreated diabetic (UD), and NaW-treated diabetic (TD) rats for 48 h, and E-cadherin expression was studied by means of qRT-PCR (A), Western blot (B), and immunofluorescence (E-cadherin; TOPRO3 nuclear staining) (C). n = 5. Each experiment was performed three separate times. *P < 0.05; ***P < 0.001; ****P < 0.0001.

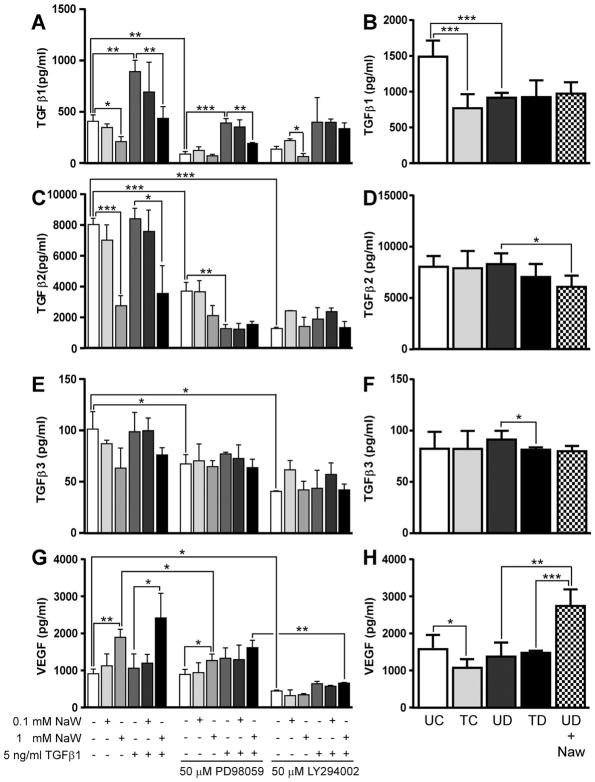

Effect of NaW on secretion of inflammatory mediators by HK-2 cells

We hypothesized that cytokine secretory profile differed between TGFβ1- and serum-stimulated HK-2 cells. As it has been determined that TGFβ1 stimulates more TGFβ1 secretion in PTECs acting in an autocrine fashion, and given that TGFβ-1 is considered the main pro-fibrotic factor in diseased kidney, we decided to determine secretion of all three isoforms of TGFβ, named TGFβ-1, -2, and -3. Basal secretion of TGFβ-1 by HK-2 cells after 48 h incubation was decreased in the presence of 1 mM NaW (but not 0.1 mM) (Fig. 5A). As expected, supernatant from HK-2 cells incubated in the presence of TGFβ-1 showed a higher amount of TGFβ-1, and 1 mM NaW co-treatment was able to restore TGFβ-1 to basal levels (Fig. 5A). PD98059, a MAPK/ERK pathway inhibitor, diminished basal secretion of TGFβ-1 in the absence and presence of NaW, and it also decreased TGFβ-1 to basal levels in TGFβ-1-treated cells. In these conditions, 1 mM NaW was able to further stimulate a decrease in TGFβ-1 levels (Fig. 5A). LY294002, a phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) inhibitor, induced a similar pattern of TGFβ-1 secretion than PD98059 (Fig. 5A).

Figure 5.

NaW reduced TGFβ and induced VEGF secretion in HK-2 cells. HK-2 cells were allowed to reach confluence and then serum-starved for 24 h. Cells were incubated with 5 ng/ml TGFβ-1 or 0.1-1 mM NaW, or both, in the presence or absence of 50 μM MAPK/ERK inhibitor (PD98059) or 50 μM PI3K inhibitor (LY294002) for 48 h (A, C, E, G). In parallel, cells were incubated with 2.5% serum from untreated control (UC), NaW-treated control (TC), untreated diabetic (UD), NaW-treated diabetic (TD), and untreated diabetic rats +1mM NaW (UD +NaW) for 48 h (B, D, F, H) as described in Materials and Methods. Medium was collected and TGFβ-1 (A–B), TGFβ-2 (C–D), TGFβ-3 (E–F), and VEGF (G–H) were measured using Luminex technology. n = 3 for A, C, E, G, and n = 5 for B, D, F, H. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001.

When HK-2 cells were treated with serum, the higher levels of TGFβ-1 were detected after incubation with serum from untreated control rats, and statistically significant lower levels were only detected in the presence of serum from NaW-treated control and untreated diabetic rats, although a tendency to decreasing TGFβ-1 levels was also observed after incubation with serum from NaW-treated diabetic rats and co-incubation with serum from untreated diabetic rats and 1 mM NaW (Fig. 5B). Levels of TGFβ-2 in basal conditions were 16-fold higher than TGFβ-1 (Fig. 5C). One millimolar NaW (but not 0.1 mM) was able to induce a decrease in TGFβ-2 levels, either in the absence or presence of TGFβ-1 (Fig. 5C). PD98059 inhibited basal secretion of TGFβ-2, which was further reduced in the presence of TGFβ-1 (Fig. 5C). Treatment with LY294002 induced a common reduction of TGFβ-2 levels in all the conditions studied (Fig. 5C). In the case of HK-2 cells treated with rat serum, no differences were determined in the secretion of TGFβ-2, except that co-treatment with serum from diabetic rat and NaW induced a minor but still statistically significant reduction with respect to the serum from diabetic rat alone (Fig. 5D). Levels of TGFβ-3 were lower than TGFβ-1 and TGFβ-2 in all conditions (Fig. 5E). Although no difference of statistical significance was determined, a tendency similar to that of the two other TGFβ isoforms is observed, as 1 mM NaW seems to reduce secretion of TGFβ-3 (Fig. 5E). Both PD98059 and LY294002 reduced basal secretion of TGFβ-3, but no further differences were detected with the combined treatments (Fig. 5E). In HK-2 cells incubated with serum, a significant reduction in TGFβ-3 secretion was detected after treatment with serum from treated versus untreated diabetic rats, but in general there were no great differences in any condition (Fig. 5F).

As VEGF-A has become a key reno-protective factor in the progression of DN, we decided to study VEGF-A secretion as a putative mediator in the effect of NaW action through rat serum. Although HK-2 cells secreted VEGF-A at a basal level after 48 h incubation in culture medium alone, 1 mM NaW (but not 0.1 mM) induced a twofold increase in the secretion of VEGF-A either in the presence or absence of TGFβ1 (Fig. 5G). Interestingly, the MAPK/ERK1/2 inhibitor PD98059 decreased NaW-induced but not basal VEGF-A secretion, whereas PI3K inhibitor LY294002 decreased both basal and NaW-induced VEGF-A secretion (Fig. 5G). By contrast, after 48 h incubation there was a decreased secretion of VEGF-A in HK-2 cells incubated with serum from NaW-treated versus untreated control rats, but no difference was determined between NaW-treated or untreated diabetic and the untreated control (Fig. 5H). However, co-incubation of HK-2 cells with serum from untreated diabetic rats and 1 mM NaW showed again the twofold increase in VEGF-A secretion, compared to serum from untreated diabetic rats alone (Fig. 5H), suggesting a direct action of NaW on VEGF-A secretion by HK-2 cells. TGFβ and VEGF-A levels in rat serum diluted at 2.5% were negligible (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

Understanding of the pathogenesis of renal fibrosis is of key importance in order to develop effective new therapeutic strategies. For this purpose, experimental animal models are important tools to pre-clinical studies. Sodium tungstate (NaW) is a potent anti-diabetic agent which has proven to correct hyperglycemia and hypertriglyceridemia in diabetic animal models, together with the normalization of other functions that finally produce a reversion of the diabetic phenotype (Barberà et al., 2001; Muñoz et al., 2001; Bertinat et al., 2015). In this study, we demonstrate that the serum from type 1 diabetic rats down-regulates the expression of E-cadherin in the human renal epithelial cell line HK-2, in a similar fashion to that of TGFβ1, one of the best characterized inducers of EMT in vitro (Liu, 2010). Interestingly, co-incubation with NaW was unable to inhibit the loss of E-cadherin expression induced by TGFβ1, however, it produced an effect when administered in vivo to diabetic rats and then serum added to cells. This result clearly indicates that the effect of NaW over the expression of E-cadherin in HK-2 cells occurs via indirect mechanisms. A similar result was reported by Altirriba et al. (2009) who demonstrated that NaW alone induced a little increase in proliferation of the INS-1E rat β cell line, but when these cells were incubated with serum from NaW-treated diabetic rats, the rate of proliferation was greatly enhanced, explaining the total increase in β cell mass observed in vivo after NaW treatment. Together, these data suggest that the study of NaW in vitro is underestimating its effects due to the lack of other interacting factors that may potentiate NaW therapeutic value.

The cell-growth arrest induced by 1 mM NaW in HK-2 cells has been previously reported on the human prostate cancer cell line PC-3, and it was attributed to G2/M cell cycle arrest due to inhibition of M-phase inducer phosphatase 3, Cdc25C (Liu et al., 2012). As a widely-used phosphatase inhibitor, NaW actions have been explained through this activity, but this property is not enough to account for all the anti-diabetic actions reported to date (Domínguez et al., 2003; Bertinat et al., 2015). As it was mentioned above, NaW stimulated an increase in proliferation of INS-1E rat β cell line (Altirriba et al., 2009), highlighting the differences in NaW activity depending on the cell model under study. Moreover, whereas Altirriba et al. (2009) demonstrated an enhancement of cell proliferation when using 10% serum from NaW-treated diabetic rats, we could not reproduce the anti-proliferative effect of NaW alone on HK-2 cells after incubation with 10% serum from NaW-treated control or diabetic rats (data not shown). Pharmacokinetics studies in rats have shown that NaW concentrations that are active in vitro are similar to the plasma levels determined in NaW-treated animals (Le Lamer et al., 2002). Taken into account that 1 mM NaW induced a pattern of growth arrest that was not reproduced by 0.1 mM NaW or the rat serum, caution must be taken with the dose of NaW used for in vivo treatment. More research is needed to explore this possibility, because a strong correlation between the G2/ M-arrested tubular epithelial cells and fibrotic outcome was seen in different mouse models of acute kidney diseases (Prunotto et al., 2012). However, our data strongly suggest beneficial in vivo effects of NaW that cannot be replicated in vitro, indicating the involvement of other pathways that need to be investigated and may provide further therapeutic options.

TGFβ-1 auto-induction in PTECs is associated with EMT and further deterioration of renal function; antagonism of TGFβ-1 has demonstrated therapeutic potential (Zhang et al., 2006). Moreover, it has been reported that TGFβ-2 is the predominant responsive element during the acute phase of DN, and that TGFβ-2 neutralizing antibodies also confer reno-protective effects as they attenuated fibrosis in experimental diabetic rat kidney (Hill et al., 2001). Pro-fibrotic actions of TGFβ-2 are mediated via common receptors with TGFβ-1 (2003). TGFβ-1 transiently activates MAPK/ERK cascade and induces expression of several proteins, including its own (Zhang et al., 2006). Furthermore, TGFβ-1 signaling occurs through the Smad family of transcriptional activators, which not only participate in deleterious effects of TGFβ-1, but also in negative feedback to suppress TGFβ-1 action (Leask and Abraham, 2004). TGFβ-1/Smad signaling is tightly controlled by MAPK/ERK cascade, which phosphorylates and modifies Smad activity (Leask and Abraham, 2004). Activation of ERK1/2 was the first molecular event unequivocally related with NaW signaling, and inhibition of MAPK/ERK cascade impairs most of NaW effects (Domínguez et al., 2003; Bertinat et al., 2015). Notably, NaW induced a decrease in the secretion of TGFβ-1 in our model, supporting the fact that over-activation of the MAPK/ERK cascade blocks nuclear accumulation of Smads in epithelial cells (Leask and Abraham, 2004). However, this effect was not observed in cells incubated with serum from rats, even when co-incubated with 1 mM NaW, suggesting that other factors in the serum are interfering with NaW action. Indeed, interleukin (IL)-1, tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, and interferon (IFN)-γ potentiate TGFβ-1 signaling by inducing TGFβ receptor expression (Liu, 2010). Any effect of NaW on secretion of these cytokines remains to be determined. Furthermore, involvement of NaW in stabilization of latent inactive forms of TGFβ may offers other potential mechanisms. PI3K is also a key downstream player of TGFβ-mediated signaling (Pozzi, 2012) and our data show that inhibition of this kinase greatly reduces secretion of TGFβ-1 and TGFβ-2 in HK-2 cells. With the exception of β pancreatic cells, the PI3K pathway is not commonly induced by NaW (Piquer et al., 2007; Bertinat et al., 2015).

Diabetes promotes endothelial dysfunction. In the glomerulus, VEGF-A-induced neoangiogenesis may contribute to initial hyperfiltration, whereas posterior decrease in VEGF production, due to podocyte loss, may result in decreased glomerular filtration rate (Eleftheriadis et al., 2013). It is known that TGFβ1 mediates VEGF-A production in cultured podocytes (Iglesias-de la Cruz et al., 2002). By contrast, TGFβ1 did not induce VEGF-A production in our model of proximal tubular cells, suggesting important differences among renal cells in the response to this pro-fibrotic factor. Indeed, VEGF-A was found to be expressed in all glomeruli, while expression in PTECs was reduced in patients with proteinuric renal disease (Rudnicki et al., 2009). In this context, autocrine and paracrine action of VEGF-A on renal tubular epithelial cells functions as a survival factor, promoting healthy communication with endothelial cells (Villegas et al., 2005; Miya et al., 2011). Reduced expression of VEGF-A has been detected in tubulointerstitial fibrosis, associated with loss of peritubular capillaries and hypoxia (Sun et al., 2006; Lindenmeyer et al., 2007), and VEGF-A supplementation has shown to suppress EMT and to ameliorate tubulointerstitial damage in vitro and in experimental animal models (Lian et al., 2011; Hong et al., 2013). In our studies, we did not detect any reversal of TGFβ1-induced down-regulation of E-cadherin even when NaW stimulated VEGF-A secretion, thereby suggesting the involvement of other pathways. It is possible that VEGF-A levels secreted after in vitro NaW treatment (2,000 pg/ml, present data) are not enough, because 10,000–100,000 pg/ml VEGF-A are required to correct E-cadherin expression (Lian et al., 2011). However, accumulation of VEGF-A in the damaged tubulointerstitial area might be mediating any NaW in vivo effect. In addition, the effects of NaW on the expression of endogenous inhibitory isoforms of VEGF-A, or regulation of VEGF-A receptors expression and signaling may require further studies.

Because treatment of human patients with NaW has been tried inconclusively only once (Hanzu et al., 2010) and further clinical studies have been delayed, experiments with serum from NaW-treated diabetic patients are not possible at the moment. Therefore, in an attempt to overcome this limitation, our data from an animal model are critical for further elucidation of the mechanisms by which NaW may be protective against diabetes in human patients, and it also provides information about possible new undesired effects. However, because murine models and humans do not always share the same molecular behavior (Gatica et al., 2013, 2015), care has to be taken when extrapolating data between species. In this context, we believe that our approach offers a more physiological model to study NaW actions on human cells. Due to the potent normoglycemic action of NaW in diabetic rats, it is reasonable to consider that the protective effect of NaW on E-cadherin expression is secondary to correction of blood glucose levels, given that diabetic problems are mainly attributed to chronic hyperglycemia (Vallon, 2011). Hence, our data allow us to propose a protective effect of NaW on E-cadherin expression in human PTECs.

At present, there is no effective therapy for treatment of fibrotic diseases. Since removal of deposited matrix is almost impossible as the fibrotic disease progresses, the sooner the disease is detected, the better the chances to stop or even reverse the damage. This is also true for DN. Given the urgent need for new therapies addressing this complex process, drugs targeting EMT have been the focus of intense research. This study describes novel functions of NaW in the context of diabetic EMT, renal inflammation, and fibrosis, and suggests that treatments with NaW can prevent down-regulation of E-cadherin, a major player in EMT, that together with the well-known normoglycemic and normotriglyceridemic effects, offers a promising therapy for DN in humans. In addition to TGFβ and VEGF, this report also suggests the participation of other factors in the in vivo protective effects of NaW on the reduction of E-cadherin expression. Further experiments will be required to confirm whether NaW-induced reduction of TGFβ-1/-2 and increase of VEGF-A secretion by proximal tubule cells may mediate the beneficial effects in the diabetic kidney. The putative effect of NaW on cell growth in vivo also needs further analysis. We believe that elucidation of these cellular mechanisms will eventually allow novel interventions aimed to delay or prevent the onset of renal fibrosis in human DN.

Acknowledgments

Microscopy analysis was performed at Centro de Microscopía Avanzada (CMA)-Bío Bío, Universidad de Concepcíon, Concepcion, Chile. TGFβ and VEGF-A secretion analysis was conducted at ICBM, Facultad de Medicina, Universidad de Chile, Santiago, Chile. This study was supported by grants from Fondo Nacional de Desarrollo Científico y Tecnologico from Chilean State: FONDECYT 3120144 to Romina Bertinat; FONDECYT 1131033 to Alejandro Yáñez.

Footnotes

The authors declares no conflict of interest.

Literature Cited

- Altirriba J, Barbera A, Del Zotto H, Nadal B, Piquer S, Sánchez-Pla A, Gagliardino JJ, Gomis R. Molecular mechanisms of tungstate-induced pancreatic plasticity: A transcriptomics approach. BMC Genomics. 2009;28:406. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-10-406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barberà A, Gomis RR, Prats N, Rodríguez-Gil JE, Domingo M, Gomis R, Guinovart JJ. Tungstate is an effective antidiabetic agent in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats: A long-term study. Diabetologia. 2001;44:507–513. doi: 10.1007/s001250100479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertinat R, Nualart F, Li X, Yáñez AJ, Gomis R. Preclinical and clinical studies for sodium tungstate: Application in humans. J Clin Cell Immunol. 2015;6:1. doi: 10.4172/2155-9899.1000285. http://dx.doi.org/10.4172/2155-9899.1000285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns WC, Twigg SM, Forbes JM, Pete J, Tikellis C, Thallas-Bonke V, Thomas MC, Cooper ME, Kantharidis P. Connective tissue growth factor plays an important role in advanced glycation end product-induced tubular epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition: Implications for diabetic renal disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;17:2484–2494. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006050525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domínguez JE, Muñoz MC, Zafra D, Sanchez-Perez I, Baqué S, Caron M, Mercurio C, Barberà A, Perona R, Gomis R, Guinovart JJ. The antidiabetic agent sodium tungstate activates glycogen synthesis through an insulin receptor-independent pathway. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:42785–42794. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M308334200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eleftheriadis T, Antoniadi G, Pissas G, Liakopoulos V, Stefanidis I. The renal endothelium in diabetic nephropathy. Ren Fail. 2013;35:592–599. doi: 10.3109/0886022X.2013.773836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gatica R, Bertinat R, Silva P, Carpio D, Ramírez MJ, Slebe JC, San Martín R, Campistol F, Caelles JM, Yáñez C. Altered expression and localization of insulin receptor in proximal tubule cells from human and rat diabetic kidney. J Cell Biochem. 2013;114:639–649. doi: 10.1002/jcb.24406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gatica R, Bertinat R, Silva P, Kairath P, Slebe F, Pardo F, Ramírez MJ, Slebe JC, Campistol JM, Nualart F, Caelles C, Yáñez AJ. Over-expression of muscle glycogen synthase in human diabetic nephropathy. Histochem Cell Biol. 2015;143:313–324. doi: 10.1007/s00418-014-1290-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanzu F, Gomis R, Coves MJ, Viaplana J, Palomo M, Andreu A, Szpunar J, Vidal J. Proof-of-concept trial on the efficacy of sodium tungstate in human obesity. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2010;12:1013–1018. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1326.2010.01293.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill C, Flyvbjerg A, Rasch R, Bak M, Logan A. Transforming growth factor-beta2 antibody attenuates fibrosis in the experimental diabetic rat kidney. J Endocrinol. 2001;170:647–651. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1700647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holian J, Qi W, Kelly DJ, Zhang Y, Mreich E, Pollock CA, Chen XM. Role of Kruppel-like factor 6 in transforming growth factor-beta1-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition of proximal tubule cells. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2008;295:F1388–F1396. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00055.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong JP, Li XM, Li MX, Zheng FL. VEGF suppresses epithelial-mesenchymal transition by inhibiting the expression of Smad3 and miR-192, a Smad3-dependent microRNA. Int J Mol Med. 2013;31:1436–1442. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2013.1337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iglesias-de la Cruz MC, Ziyadeh FN, Isono M, Kouahou M, Han DC, Kalluri R, Mundel P, Chen S. Effects of high glucose and TGF-beta1 on the expression of collagen IV and vascular endothelial growth factor in mouse podocytes. Kidney Int. 2002;62:901–913. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2002.00528.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwano M, Plieth D, Danoff TM, Xue C, Okada H, Neilson EG. Evidence that fibroblasts derive from epithelium during tissue fibrosis. J Clin Invest. 2002;110:341–350. doi: 10.1172/JCI15518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Lamer S, Cros G, Pinol C, Fernández-Alvarez J, Bressolle F. An application of population kinetics analysis to estimate pharmacokinetic parameters of sodium tungstate after multiple-dose during preclinical studies in rats. Pharmacol Toxicol. 2002;90:100–105. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0773.2002.900208.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leask A, Abraham DJ. TGF-beta signaling and the fibrotic response. FASEB J. 2004;18:816–827. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-1273rev. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q, Liu BC, Lv LL, Ma KL, Zhang XL, Phillips AO. Monocytes induce proximal tubular epithelial-mesenchymal transition through NF-kappa B dependent upregulation of ICAM-1. J Cell Biochem. 2011;112:1585–1592. doi: 10.1002/jcb.23074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lian YG, Zhou QG, Zhang YJ, Zheng FL. VEGF ameliorates tubulointerstitial fibrosis in unilateral ureteral obstruction mice via inhibition of epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2011;32:1513–1521. doi: 10.1038/aps.2011.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindenmeyer MT, Kretzler M, Boucherot A, Berra S, Yasuda Y, Henger A, Eichinger F, Gaiser S, Schmid H, Rastaldi MP, Schrier RW, Schlondorff D, Cohen CD. Interstitial vascular rarefaction and reduced VEGF-A expression in human diabetic nephropathy. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;18:1765–1776. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006121304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y. New insights into epithelial-mesenchymal transition in kidney fibrosis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;21:212–222. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2008121226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu TT, Liu YJ, Wang Q, Yang XG, Wang K. Reactive-oxygen-species-mediated Cdc25C degradation results in differential antiproliferative activities of vanadate, tungstate, and molybdate in the PC-3 human prostate cancer cell line. J Biol Inorg Chem. 2012;17:311–320. doi: 10.1007/s00775-011-0852-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miya M, Maeshima A, Mishima K, Sakurai N, Ikeuchi H, Kuroiwa T, Hiromura K, Yokoo H, Nojima Y. Enhancement of in vitro human tubulogenesis by endothelial cell-derived factors: implications for in vivo tubular regeneration after injury. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2011;301:F387–F395. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00619.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz MC, Barberà A, Domínguez J, Fernàndez-Alvarez J, Gomis R, Guinovart JJ. Effects of tungstate, a new potential oral antidiabetic agent, in Zucker diabetic fatty rats. Diabetes. 2001;50:131–138. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.50.1.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noh H, Oh EY, Seo JY, Yu MR, Kim YO, Ha H, Lee HB. Histone deacetylase-2 is a key regulator of diabetes- and transforming growth factor-beta1-induced renal injury. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2009;297:F729–F739. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00086.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palanivel R, Sakthisekaran D. Immunomodulatory effect of tungstate on streptozotocin-induced experimental diabetes in rats. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2002;958:382–386. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2002.tb03008.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piquer S, Barcelo-Batllori S, Julia M, Marzo N, Nadal B, Guinovart JJ, Gomis R. Phosphorylation events implicating p38 and PI3K mediate tungstate-effects in MIN6 beta cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;358:385–391. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.04.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pozzi A. PI3-kinase and TGF-β in glomerular nephropathy: Which comes first. Kidney Int. 2012;82:507–509. doi: 10.1038/ki.2012.154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prunotto M, Budd DC, Gabbiani G, Meier M, Formentini I, Hartmann G, Pomposiello S, Moll S. Epithelial-mesenchymal crosstalk alteration in kidney fibrosis. J Pathol. 2012;228:131–147. doi: 10.1002/path.4049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rastaldi MP, Ferrario F, Giardino L, Dell’Antonio G, Grillo C, Grillo P, Strutz F, Muller GA, Colasanti G, D’Amico G. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition of tubular epithelial cells in human renal biopsies. Kidney Int. 2002;62:137–146. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2002.00430.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudnicki M, Perco P, Enrich J, Eder S, Heininger D, Bernthaler A, Wiesinger M, Sarkozi R, Noppert SJ, Schramek H, Mayer B, Oberbauer R, Mayer G. Hypoxia response and VEGF-A expression in human proximal tubular epithelial cells in stable and progressive renal disease. Lab Invest. 2009;89:337–346. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.2008.158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simonson MS. Phenotypic transitions and fibrosis in diabetic nephropathy. Kidney Int. 2007;71:846–854. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5002180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun D, Feng J, Dai C, Sun L, Jin T, Ma J, Wang L. Role of peritubular capillary loss and hypoxia in progressive tubulointerstitial fibrosis in a rat model of aristolochic acid nephropathy. Am J Nephrol. 2006;26:363–371. doi: 10.1159/000094778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vallon V. The proximal tubule in the pathophysiology of the diabetic kidney. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2011;300:R1009–R1022. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00809.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villegas G, Lange-Sperandio B, Tufro A. Autocrine and paracrine functions of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) in renal tubular epithelial cells. Kidney Int. 2005;67:449–457. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.67101.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong MG, Perkovic V, Woodward M, Chalmers J, Li Q, Hillis GS, Yaghobian Azari D, Jun M, Poulter N, Hamet P, Williams B, Neal B, Mancia G, Cooper M, Pollock CA. Circulating bone morphogenetic protein-7 and transforming growth factor-β1 are better predictors of renal end points in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Kidney Int. 2013;83:278–284. doi: 10.1038/ki.2012.383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu L, Border WA, Huang Y, Noble NA. TGF-beta isoforms in renal fibrogenesis. Kidney Int. 2003;64:844–856. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2003.00162.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu C, Xin W, Zhen J, Liu Y, Javed A, Wang R, Wan Q. Human antigen R mediated post-transcriptional regulation of epithelial-mesenchymal transition related genes in diabetic nephropathy [published online ahead of print September 30, 2014] J Diabetes. 2014 doi: 10.1111/1753-0407.12220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang M, Fraser D, Phillips A. ERK, p38, and Smad signaling pathways differentially regulate transforming growth factor-beta1 autoinduction in proximal tubular epithelial cells. Am J Pathol. 2006;169:1282–1293. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2006.050921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]