Abstract

Objectives

To compare rates of switchbacks to branded drug products for patients switched from branded to authorized generic drug products, which have the same active ingredients, appearance, and excipients as the branded product, with patients switched from branded to generic drug products, which have the same active ingredients as the branded product but may differ in appearance and excipients.

Design

Observational cohort study.

Setting

Private (a large commercial health plan) and public (Medicaid) insurance programs in the US.

Participants

Beneficiaries of a large US commercial health insurer between 2004 and 2013 (primary cohort) and Medicaid beneficiaries between 2000 and 2010 (replication cohort).

Main outcome measures

Patients taking branded products for one of the study drugs (alendronate tablets, amlodipine tablets, amlodipine-benazepril capsules, calcitonin salmon nasal spray, escitalopram tablets, glipizide extended release tablets, quinapril tablets, and sertraline tablets) were identified when they switched to an authorized generic or a generic drug product after the date of market entry of generic drug products. These patients were followed for switchbacks to the branded drug product in the year after their switch to an authorized generic or a generic drug product. Cox proportional hazard models were used to estimate hazard ratios and 95% confidence intervals after adjusting for demographics, including age, sex, and calendar year. Inverse variance meta-analysis was used to pool adjusted hazard ratios across all drug products.

Results

A total of 94 909 patients switched from branded to authorized generic drug products and 116 017 patients switched from branded to generic drug products and contributed to the switchback analysis. Unadjusted incidence rates of switchback varied across drug products, ranging from a low of 3.8 per 100 person years (for alendronate tablets) to a high of 17.8 per 100 person years (for amlodipine-benazepril capsules), with an overall rate of 8.2 per 100 person years across all drug products. Adjusted switchback rates were consistently lower for patients who switched from branded to authorized generic drug products compared with branded to generic drug products in the primary cohort (pooled hazard ratio 0.72, 95% confidence interval 0.64 to 0.81). Similar results (0.75, 0.62 to 0.91) were observed in the replication cohort.

Conclusion

Switching from branded to authorized generic drug products was associated with lower switchback rates compared with switching from branded to generic drug products.

Introduction

Generic drugs account for nearly nine out of every 10 prescriptions filled in the US and the UK.1 2 Generic drugs have identical active ingredients to their branded counterparts, but can be substantially less expensive.3 Owing to this lower cost, generic drugs have the potential to improve medication adherence and persistence.4 5 Generic drug products are approved when pharmaceutical equivalence and bioequivalence to the reference product have been demonstrated. No requirements for testing clinical equivalence in pre-marketing trials is required, but robust evidence from multiple post-marketing studies has demonstrated equivalent clinical efficacy of many generic drug products with their branded counterparts.4 6 7 8 9 Many patients perceive generic drug products to be less effective and less safe,10 11 12 13 and express lower confidence in them for treating serious illness.14 As a result of the negative expectations, some patients may report experiencing negative outcomes upon switching from branded to generic drug products; a phenomenon described as the nocebo effect.15

Changes in the physical appearance of a drug product, including its shape, color, and size, may influence such negative perceptions in patients switched from branded to generic drug products and may ultimately lead patients to specifically request the brand version.16 Among patients switched from branded to generic drug products, the rates of switching back to branded drug products are reported to be in the range of 12% to 65% for many drug classes including antiepileptics, antipsychotics, and β blockers.17 18 19 Switching back to the branded drug product when low cost generic drug products are available has important economic implications for the healthcare system. Use of branded drug products when generic drug products are available increases patient expenses by an estimated $1.2bn (£860m; €980m), and overall healthcare system costs by an estimated $7.7bn (£5.5bn; €6.3bn) annually in the US.20 The higher costs of branded drug products can result in lower adherence which, in turn, can lead to worse clinical outcomes.4 Therefore, it is critical to carefully understand and address the reasons for switchbacks.

Authorized generic drug products are a unique type of generic drug product; they are identical in composition and appearance to the branded drug product but are marketed by the brand manufacturer (or its licensees) as generics, usually around the date of market entry of other generic drug products. Unlike other generic products, authorized generics are marketed in the US under the branded drug product’s New Drug Application license without any bioequivalence testing requirements.21 As authorized generics have identical active ingredients, appearance, and excipients as the corresponding branded products, they may be less susceptible to negative perceptions that affect the use of other generic products. We hypothesized that branded to authorized generic drug product switching would be associated with fewer switchbacks compared with branded to generic drug product switching. To test this hypothesis, we compared branded to authorized generic with branded to generic drug product switchback rates in a large commercial health plan and replicated the study with data from Medicaid, a public insurance program for Americans on low incomes.

Methods

Data sources

The study used de-identified data from a large US commercial health insurance database from 2004-13. This source contains comprehensive longitudinal health insurance claims information on enrollee demographics, inpatient and outpatient diagnoses and procedures, and outpatient prescription dispensing records.

Drug products

In collaboration with members of the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Office of Generic Drugs, we screened 22 drug products that had marketed authorized generics between 2004 and 2013. We excluded products for two reasons. First, if the date of market entry of authorized generics was more than 30 days after the date of market entry of the first generic product. Concurrent availability of an authorized generic and a generic product was required to reliably evaluate switching patterns among prevalent branded drug product users (two products excluded). Second, if we were note able to definitively identify authorized generic products using current National Drug Codes (NDC) derived from the FDA NDC directory. Authorized generic, generic, and branded drug products were identified based on the Market Category Name field of the NDC directory. As the NDC directory does not maintain details on discontinued NDC, we excluded drug products for which more than 5% of filled prescriptions identified in our database belonged to NDC that were not found in the NDC directory (12 products excluded). The following eight products met our inclusion criteria: alendronate tablets, amlodipine tablets, amlodipine-benazepril capsules, calcitonin salmon nasal spray, escitalopram tablets, glipizide extended release tablets,quinapril tablets, and sertraline tablets.

Study design

Substitution analysis

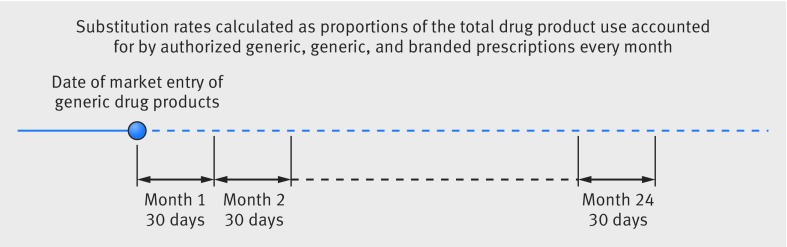

We first conducted a prescription level substitution analysis to understand trends in the use of authorized generic and generic drug products in the first two years after loss of patent protection for each of the eight branded drug products included in this study. Figure 1 shows that we calculated the proportion of prescriptions that were filled with authorized generic, generic, and branded drug products by using 30 day intervals starting from the date of market entry of the first generic drug product.

Fig 1.

Study design for substitution analyses

Switchback analysis

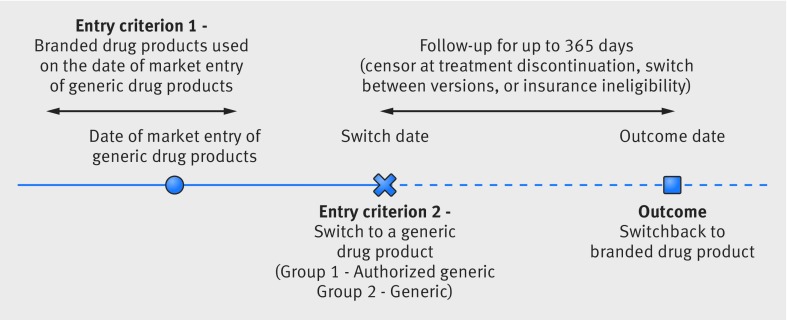

We next evaluated rates of switchback to the branded drug product among patients taking branded drug products who were switched to an authorized generic or generic after their date of market entry. For this patient level analysis, we identified patients actively using branded drug products on the date of market entry of the first generic drug product for each of the eight study drug products. We defined active branded drug product users as patients filling a prescription for a branded drug product with sufficient supply to overlap with the date of market entry of generic drug products. Among branded drug product users, we identified two groups of patients. Patients in one group were switched to the same dose of an authorized generic drug product. Patients in the other group were switched to the same dose of a generic drug product. To define switches, we required the patients to be using the branded drug product without a gap of more than 14 days between the end of the last branded drug product prescription fill and the switch to authorized generic or generic drug product. Figure 2 shows that we followed patients who had switched to authorized generic and generic drug products beginning on this switch date to evaluate the date that they switched back to the branded drug product (outcome date). Patients who disenrolled from their health plan, changed exposure groups (switched from authorized generic to generic or vice versa), discontinued use of the drug product (defined as a gap of more than 14 days between two prescriptions), or had 365 days of follow-up data were censored.

Fig 2.

Study design for switchback analyses

Statistical analysis

We plotted proportions of prescriptions dispensed as authorized generic, generic, or branded drug products in the substitution analysis. We reported the total number of switchers included in the switchback analysis along with descriptive statistics for patient demographics stratified by switch to authorized generic or generic drug product. Unadjusted incidence rates of brand switchbacks were reported for all eight drug products and incidence rate ratios and incidence rate differences were calculated comparing branded to authorized generic with branded to generic switchers. Kaplan-Meier survival probabilities for the outcome of switchback over the follow-up time were calculated for all drug products and plotted for branded to authorized generic and branded to generic switchers along with 95% confidence intervals. We used a Cox proportional hazards regression model, adjusting for basic demographics (age, sex, and calendar year), to estimate hazard ratios and 95% confidence intervals for branded drug product switchbacks comparing branded to authorized generic with branded to generic switchers. To summarize switchback estimates across the eight study drug products, we conducted inverse variance weighted random effects meta-analyses. We quantified the between study heterogeneity with the I2 statistic. We used RevMan version 5.3 (Copenhagen: The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration, 2014) for meta-analyses. All other statistical analyses were conducted with SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Replication analysis

To confirm the findings observed in our switchback analysis, we replicated our study in a separate patient population with data from Medicaid. We used Medicaid Analytic eXtract files from 49 state Medicaid programs (all states except Arizona) for the period 2000-10. Medicaid Analytic eXtract files contain comprehensive information on patient demographics, inpatient and outpatient diagnoses and procedures, and outpatient prescription dispensing records, which can be tracked longitudinally. Methods for cohort identification and statistical analysis were identical to the primary analysis. We did not include escitalopram tablets in the replication analysis because the date of market entry of generic drug products was March 2012.

Patient involvement

No patients were involved in setting the research question or the outcome measures, nor were they involved in developing plans for design or implementation of the study. No patients were asked to advise on interpretation or writing up of results. There are no plans to disseminate the results of the research to study participants or the relevant patient community.

Results

Substitution analysis

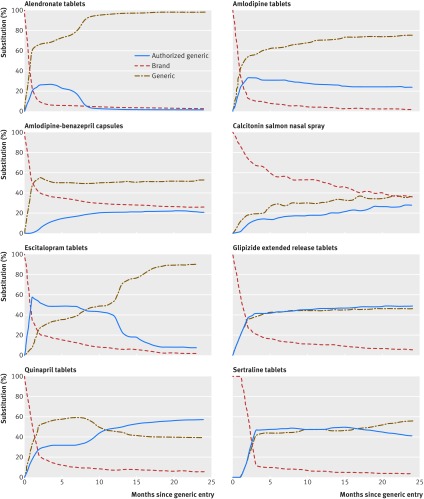

Figure 3 shows that for all but one study drug product (calcitonin nasal spray), authorized generic and generic drug products represented a majority of drug use within the six months after the date of market entry of generic drug products. For most study drug products, the authorized generic gained and maintained substantial market share for the first two years. For alendronate tablets and escitalopram tablets, however, authorized generic utilization decreased substantially after the first nine months of generic availability. For calcitonin salmon nasal spray and amlodipine-benazepril capsules, the brand product retained a sizable market share in the first two years after authorized generic and generic drug products became available.

Fig 3.

Substitution patterns within the first two years after the date of market entry of the first generic in the primary cohort

Switchback analysis

A total of 94 909 branded to authorized generic and 116 017 branded to generic switchers for seven drug products contributed to the switchback analysis. The sample size for calcitonin salmon nasal spray was insufficient to calculate switchback rates. Table 1 shows that baseline demographics, including age and sex, were similar between authorized generic switchers for most of the drug products with a few exceptions. Patients switching from branded to authorized generic drug products compared with patients switching from branded to generic drug products had an older mean age for amlodipine tablets and glipizide extended release tablets and a younger mean age for sertraline tablets.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of the patients included in the study

| Drug product | Total | Mean age, years (SD) | % Male | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Authorized generic switchers (94 995) | Generic switchers (116 265) | Authorized generic switchers | Generic switchers | Standardized difference* | Authorized generic switchers | Generic switchers | Standardized difference* | |||

| Alendronate tablets | 4367 | 15 676 | 63 (10) | 63 (10) | −4.4 | 7.9 | 8.1 | −0.7 | ||

| Amlodipine tablets | 26 529 | 31 867 | 60 (12) | 56 (11) | 29.5 | 55.5 | 55.1 | 0.7 | ||

| Amlodipine-benazepril capsules | 1645 | 20 689 | 57 (10) | 56 (11) | 5.2 | 64.4 | 63.7 | 1.5 | ||

| Calcitonin salmon nasal spray | 86 | 248 | 68 (11) | 69 (10) | −9.5 | 7.0 | 8.1 | −4.1 | ||

| Escitalopram tablets | 24 128 | 5595 | 47 (15) | 46 (15) | 2.1 | 31.9 | 31.1 | 1.8 | ||

| Glipizide extended release tablets | 7963 | 6114 | 59 (11) | 57 (11) | 19.1 | 58.6 | 58.4 | 0.4 | ||

| Quinapril tablets | 8799 | 11 165 | 58 (11) | 56 (11) | 7.1 | 60.4 | 59.2 | 2.5 | ||

| Sertraline tablets | 21 478 | 24 911 | 44 (14) | 47 (15) | −15.9 | 30.1 | 29.8 | 0.6 | ||

Standardized difference of 10 or higher indicate meaningful differences between groups

A total of 3416 switchback events over 46 218 person years of follow-up were observed among branded to authorized generic switchers and 5336 events over 60 198 person years were observed among branded to generic switchers across the seven included drug products. Unadjusted incidence rates of switchback varied across drug products, ranging from a low of 3.8 per 100 person years for alendronate tablets to a high of 17.8 per 100 person years for amlodipine-benazepril capsules. The overall unadjusted incidence rate was 8.2 per 100 person years for the seven drug products included in this analysis. Table 2 provides the unadjusted switchback rates stratified by authorized generic status for all drugs. The crude rates of switchback were noticeably lower for branded to authorized generic switchers compared with branded to generic switchers for all drug products except alendronate tablets (for which the rates were numerically lower but statistically non-significant). Incidence rate differences in switchbacks between branded to authorized generic switchers and branded to generic switchers varied from a low of 0.7 per 100 person years for alendronate tablets to a high of 5.4 per 100 person years for amlodipine-benazepril capsules. The overall incidence rate difference was 1.5 per 100 person years.

Table 2.

Unadjusted incidence rates of branded drug product switchbacks for authorized generic compared with generic switchers per 100 person years of follow-up

| Drug product | Overall (95% CI) | Authorized generic switchers (95% CI) | Generic switchers (95% CI) | Incidence rate difference (95% CI) | Incidence rate ratios (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alendronate tablets | 3.8 (3.4 to 4.2) | 3.2 (2.4 to 4.2) | 3.9 (3.5 to 4.3) | −0.7 (−1.7 to 0.3) | 0.82 (0.61 to 1.10) |

| Amlodipine tablets | 4.8 (4.6 to 5.1) | 4.3 (4.0 to 4.7) | 5.2 (4.9 to 5.6) | −0.9 (−1.4 to −0.4) | 0.83 (0.75 to 0.92) |

| Amlodipine-benazepril capsules | 17.8 (17.0 to 18.6) | 12.8 (10.6 to 15.4) | 18.3 (17.4 to 19.1) | −5.4 (−7.9 to −3.0) | 0.70 (0.58 to 0.84) |

| Escitalopram tablets | 13.8 (13.2 to 14.5) | 13.4 (12.7 to 14.1) | 15.6 (14.1 to 17.2) | −2.2 (−3.9 to −0.5) | 0.86 (0.77 to 0.96) |

| Glipizide extended release tablets | 7.8 (7.1 to 8.5) | 6.5 (5.7 to 7.3) | 9.5 (8.4 to 10.7) | −3.0 (−4.4 to −1.7) | 0.68 (0.57 to 0.81) |

| Quinapril tablets | 4.7 (4.4 to 5.2) | 3.2 (2.7 to 3.7) | 6.0 (5.5 to 6.7) | −2.9 (−3.7 to −2.1) | 0.52 (0.43 to 0.63) |

| Sertraline tablets | 9.2 (8.8 to 9.6) | 8.1 (7.5 to 8.7) | 10.1 (9.5 to 10.7) | −2.0 (−2.8 to −1.2) | 0.80 (0.73 to 0.88) |

| Overall | 8.2 (8.1 to 8.4) | 7.4 (7.2 to 7.6) | 8.9 (8.6 to 9.1) | −1.5 (−1.8 to −1.1) | 0.83 (0.80 to 0.87) |

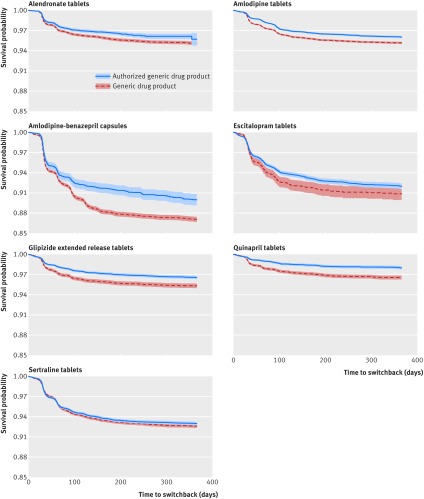

Figure 4 shows Kaplan-Meier plots for all included drug products. Visual inspection of the plots indicated a sharp decline in the survival probabilities within the first three months for all drug products. This suggests that the majority of switchbacks occur soon after the switch from branded to approved generic or generic drug products. Separation of the probability curves for authorized generic and generic groups also appeared to occur within the first three months of follow-up, after which the curves were parallel.

Fig 4.

Kaplan-Meier survival probability plots (with 95% CI shaded) of branded drug product switchbacks over the follow-up period in exposure groups in the primary cohort

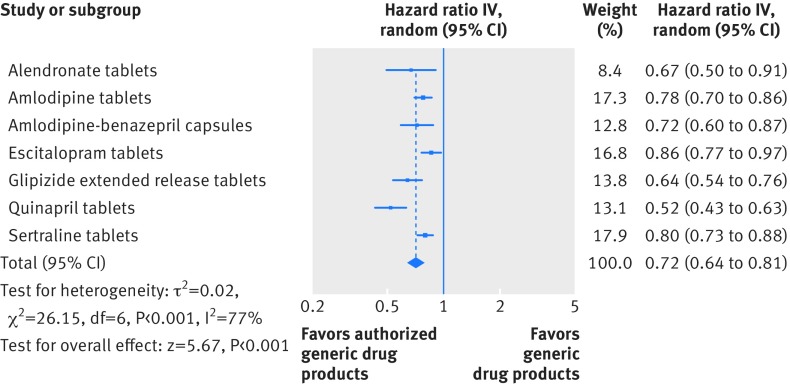

Figure 5 shows that in the adjusted analysis, the switchback rates remained consistently lower among branded to authorized generic switchers than branded to generic switchers for all included drug products. The magnitude of this effect was largest for quinapril tablets (hazard ratio 0.52, 95% confidence interval 0.43 to 0.63) and smallest for escitalopram tablets (0.86, 0.77 to 0.97). The pooled hazard ratio across the seven drug products in the study suggested that branded to authorized generic switching was associated with a 28% lower rate of switchback compared with branded to generic switching (0.72, 0.64 to 0.81). Although we observed between study heterogeneity (I2=77%), all hazard ratios for the individual drug products were less than 1.0 with 95% confidence intervals that excluded the null value.

Fig 5.

Switchback analysis for the primary cohort. Hazard ratios were adjusted for age, sex, and calendar year

Replication analysis

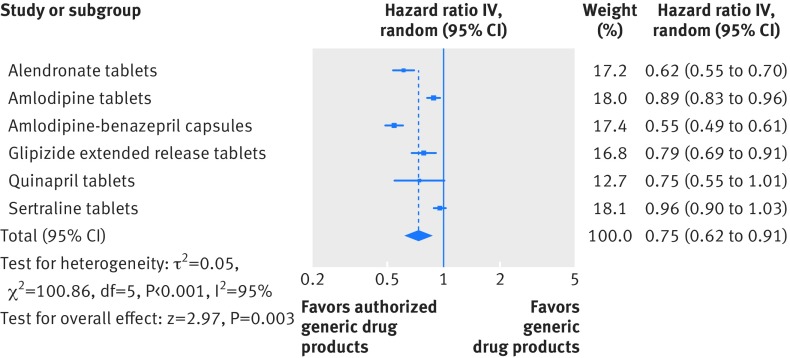

A total of 85 260 branded to authorized generic switchers and 94 372 branded to generic switchers were included in the replication analysis. Adjusted switchback rates were likewise consistently lower for branded to authorized generic switchers compared with branded to generic switchers. The differences were statistically significant for alendronate tablets, amlodipine tablets, amlodipine-benazepril capsules, and glipizide extended release tablets and non-significant for quinapril tablets and sertraline tablets. Figure 6 shows that the pooled hazard ratio across the six drug products included in this analysis was 0.75 (95% confidence interval 0.62 to 0.91).

Fig 6.

Switchback analysis for the replication cohort. Hazard ratios were adjusted for age, sex, and calendar year.

Discussion

In this observational cohort study, we found that authorized generic versions of the eight study drug products were regularly dispensed during the first two years after the date of market entry of the first generic drug product. Patients who switched from branded products to authorized generic drug products upon market entry of the first generic were less likely to switchback to the branded drug product compared with patients who switched to generic drug products.

We observed that eight out of every 100 patients taking branded drug products who switched to a generic, switched back to the branded drug product within a year. The switchback rates were 28% lower for patients who switched to an authorized generic compared with patients who switched to a generic drug product. One potential reason for lower switchbacks among branded to authorized generic switchers may be the similarity in product appearance between authorized generics and branded drug products. Changes in drug product appearance upon branded to generic drug product switch may induce the nocebo effect, defined as negative effects in treatment efficacy or tolerability mediated by negative expectations, through psychological or neurobiological factors.15 22 23 A recent study purportedly tested the safety and efficacy of β blockers, but all 60 patients actually received placebos. The patients who were randomized to switch from a ‘branded’ to a ‘generic’ drug product with a different color tablet were reported to have lower reductions in blood pressure and more adverse events compared with patients who continued receiving ‘branded’ drug products.16 Studies have also found an association between changes in tablet appearance, including shape and color, and medication non-persistence.24 25

Another possible explanation for higher branded switchback rates among branded to generic drug product switchers may be lower efficacy or an increase in adverse events with generic products. However, recent randomized trials of certain antiepileptic drugs have found no clinical impact of switching from branded to generic drug products.26 27 Generic drug products for various drug classes including β blockers, diuretics, calcium channel blockers, statins, and antiplatelet agents have also repeatedly been demonstrated to provide equivalent clinical benefits in short term endpoints, including blood pressure changes, urine output, and platelet aggregation as well as long term endpoints such as atherothrombotic events and healthcare utilization (eg, hospital stays and emergency department visits).4 6 7 8 28 In a separate study, we found no differences in clinically important long term outcomes between authorized generic and generic versions of all the eight drug products included in this study.29 Considering all of this available evidence suggesting similarity in clinical outcomes between independent generic products and their branded counterparts, differences observed in the switchback rates in this study between authorized generic and generic drug products are unlikely to be fully explained by differences in quality, safety, or efficacy.

One previous study of nearly 6000 switchers from a regional healthcare delivery system in the US reported the overall switchback rate of 4.8% (a total of 264 switchback events) and did not detect differences in switchback rates between authorized generic and generic switchers.30 The most likely explanations of the apparently divergent finding may include a lack of statistical power in the previous study and different individual products investigated in the two studies. Switchback patterns may depend substantially on the specific drug product factors including the total number of generics available, specific indications and formulations, marketing of specific products, and different contracting agreements between manufacturers and pharmacy chains.

Implications for policy makers

In the US, laws allowing for pharmacist substitution of branded drug products with generic drug products are intended to promote cost savings.31 Doctors or patients may request pharmacists to ‘dispense as written’ so that the branded drug product is dispensed instead of the generic drug product. According to one estimate, this practice increases the cost burden on the US healthcare system by $7.7bn (£5.5bn; €6.3bn) annually.20 Promoting continued use of generic drug products, rather than switching back to branded drug products, could lead to substantial cost savings. One possible way to reduce switchbacks could be for generic drug products to mirror the appearance of branded drug products. Courts would likely not allow brand name manufacturers to claim intellectual property protections over their products’ appearance to prevent their use by generic manufacturers.32 Additionally, doctors or pharmacists could discuss the nocebo effect with patients. Reducing switchbacks to branded drug products may be possible if patients are made aware that branded and generic drug products are of equal quality, safety, and efficacy.

Strengths and weaknesses of this study

Our study is the largest investigation to date of brand switchbacks among patients who switched from branded to authorized generic or branded to generic drug products. A major strength of this analysis is the availability of comprehensive data on prescription dispensing in two large cohorts based on national insurance programs in the US. This allowed us to document representative utilization patterns of different versions of drug products after patent expiration of the branded drug product. We consistently observed lower switchback rates among branded to authorized generic drug product switchers for seven drug products in four therapeutic classes in two separate databases, suggesting that our results are generalizable. Nevertheless, there are some limitations of this study worth discussing. First, administrative claims data are well suited to characterize patterns of drug utilization in routine clinical care (eg, substitution and switchback analysis) but do not contain information on the reasons behind an individual’s decision to switch treatments or explicit information regarding patient or provider perceptions of generic drug products. Therefore, our analysis is unable to distinguish between differences in actual clinical experiences with authorized generics or generics and differences in perceptions of these products. Second, no narrow therapeutic index drugs, which have generated particular concern over generic safety and efficacy, met our inclusion criteria. Our results may therefore not generalize to these types of drugs.

Conclusions

Among patients taking branded drug products who switched to generic drug products, switchbacks occurred frequently. Patients who switched to authorized generic drug products, which have the same active ingredients, appearance, and excipients, had lower rates of switchbacks compared with patients who switched to generic drug products, which may have a different appearance and excipients compared with the branded drug product. Given that authorized generic and generic drug products have identical active ingredients, our results indicate that the higher switchbacks observed among generic switchers may in part be driven by negative perceptions of generic drug products. Interventions to reduce switchbacks may provide an opportunity for major cost savings.

What is already known on this topic

Differences in appearance and excipients between branded and generic drug products may contribute to negative perceptions of generic drugs

Patients switching back to branded drug products from authorized generic or generic drug products results in a substantial cost to the healthcare system

Authorized generics are generic drug products manufactured by the branded drug product manufacturer, therefore both drug products have the same active ingredients, appearance, and excipients

What this study adds

Patients who switched from branded to authorized generic drug products had lower rates of brand switchbacks compared with patients who switched from branded to generic drug products

Interventions to improve patient-provider communication to increase patient awareness regarding similarity between branded and generic drug products in terms of quality, safety, and efficacy may be crucial to prevent brand switchbacks

Consistency in appearance between branded and generic drug products may also help in preventing brand switchbacks

Acknowledgments

For US Federal Government employees acting in the course of their employment: The following Author Warranties apply (excluding 1.iii)....1. The author(s) warrant that: i) they are the sole author(s) of the Contribution which is an original work; ii) the whole or a substantial part of the Contribution has not previously been published; iii) they or their employers are the copyright owners of the Contribution; iv) to the best of their knowledge that the Contribution does not contain anything which is libellous, illegal or infringes any third party’s copyright or other rights; v) that they have obtained all necessary written consents for any patient information which is supplied with the Contribution and vi) that they have declared or will accurately declare all competing interests to the Publisher.

Contributors: RJD, AS, JB, JC, ASK, MAF, SKD, SR, and JJG conceived and designed the study. RJD, SD, NFK, JL, and JRR analyzed the data. All authors interpreted the data and drafted the manuscript. All authors had full access to the data in the study and can take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. RJD is the guarantor.

Funding: This study was supported by the US Food and Drug Administration, Office of Generic Drugs (U01FD005279). Views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the official policies of the Department of Health and Human Services, nor does any mention of trade names, commercial practices, or organization imply endorsement by the US Government.

Competing interests: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf and declare: JJG is principal investigator of research grants from Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation and Eli Lilly and Company to the Brigham and Women’s Hospital. JGG is a for Optum, Inc and Aetion, Inc. RJD is principal investigator of a research grant from Merck to the Brigham and Women’s Hospital. JRR is a consultant to Aetion Inc. SKD and SR are employees of the FDA.

Ethical approval: The study was approved by the Brigham and Women’s Hospital Institutional Review Board and the FDA’s Research in Human Subjects Committee.

Data sharing: Additional aggregate level data available from the corresponding author at rdesai@bwh.harvard.edu.

Transparency: The lead author (RJD) affirms that the manuscript is an honest, accurate, and transparent account of the study being reported; that no important aspects of the study have been omitted; and that any discrepancies from the study as planned (and, if relevant, registered) have been explained.

References

- 1.Generic Pharmaceutical Association. Washington DC, 2016. Generic Drug Savings & Access in the United States Report. http://www.gphaonline.org/media/generic-drug-savings-2016/index.html.

- 2. Duerden MG, Hughes DA. Generic and therapeutic substitutions in the UK: are they a good thing? Br J Clin Pharmacol 2010;70:335-41. 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2010.03718.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.United States Food & Drug Administration. What are generic drugs? https://www.fda.gov/Drugs/ResourcesForYou/Consumers/BuyingUsingMedicineSafely/GenericDrugs/default.htm, accessed 2/15/2017.

- 4. Gagne JJ, Choudhry NK, Kesselheim AS, et al. Comparative effectiveness of generic and brand-name statins on patient outcomes: a cohort study. Ann Intern Med 2014;161:400-7. 10.7326/M13-2942 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Gagne JJ, Kesselheim AS, Choudhry NK, Polinski JM, Hutchins D, Matlin OS, et al. Comparative effectiveness of generic versus brand-name antiepileptic medications. Epilepsy Behav 2015;52:14-8. 10.1016/j.yebeh.2015.08.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Jackevicius CA, Tu JV, Krumholz HM, et al. Comparative Effectiveness of Generic Atorvastatin and Lipitor® in Patients Hospitalized with an Acute Coronary Syndrome. J Am Heart Assoc 2016;5:e003350. 10.1161/JAHA.116.003350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kesselheim AS, Misono AS, Lee JL, et al. Clinical equivalence of generic and brand-name drugs used in cardiovascular disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA 2008;300:2514-26. 10.1001/jama.2008.758 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Corrao G, Soranna D, Arfè A, et al. Are generic and brand-name statins clinically equivalent? Evidence from a real data-base. Eur J Intern Med 2014;25:745-50. 10.1016/j.ejim.2014.08.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Corrao G, Soranna D, Merlino L, Mancia G. Similarity between generic and brand-name antihypertensive drugs for primary prevention of cardiovascular disease: evidence from a large population-based study. Eur J Clin Invest 2014;44:933-9. 10.1111/eci.12326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Shrank WH, Cox ER, Fischer MA, Mehta J, Choudhry NK. Patients’ perceptions of generic medications. Health Aff (Millwood) 2009;28:546-56. 10.1377/hlthaff.28.2.546 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Shrank WH, Liberman JN, Fischer MA, Girdish C, Brennan TA, Choudhry NK. Physician perceptions about generic drugs. Ann Pharmacother 2011;45:31-8. 10.1345/aph.1P389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Pasina L, Urru S, Mandelli S, SGCP Investigators Why do patients have doubts about generic drugs in Italy? Eur J Clin Pharmacol 2016. 10.1007/s00228-016-2069-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Brennan TA, Lee TH. Allergic to generics. Ann Intern Med 2004;141:126-30. 10.7326/0003-4819-141-2-200407200-00011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Figueiras MJ, Alves NC, Marcelino D, Cortes MA, Weinman J, Horne R. Assessing lay beliefs about generic medicines: Development of the generic medicines scale. Psychol Health Med 2009;14:311-21. 10.1080/13548500802613043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bingel U, Placebo Competence Team Avoiding nocebo effects to optimize treatment outcome. JAMA 2014;312:693-4. 10.1001/jama.2014.8342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Faasse K, Cundy T, Gamble G, Petrie KJ. The effect of an apparent change to a branded or generic medication on drug effectiveness and side effects. Psychosom Med 2013;75:90-6. 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3182738826 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. LeLorier J, Duh MS, Paradis PE, et al. Clinical consequences of generic substitution of lamotrigine for patients with epilepsy. Neurology 2008;70:2179-86. 10.1212/01.wnl.0000313154.55518.25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Andermann F, Duh MS, Gosselin A, Paradis PE. Compulsory generic switching of antiepileptic drugs: high switchback rates to branded compounds compared with other drug classes. Epilepsia 2007;48:464-9. 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2007.01007.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Molinier A, Palmaro A, Rousseau V, et al. Does substitution of brand name medications by generics differ between pharmacotherapeutic classes? A population-based cohort study in France. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 2017;73:471-7. 10.1007/s00228-016-2185-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Shrank WH, Liberman JN, Fischer MA, et al. The consequences of requesting “dispense as written”. Am J Med 2011;124:309-17. 10.1016/j.amjmed.2010.11.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.United States Food & Drug Administration. List of Authorized Generic Drugs. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/developmentapprovalprocess/howdrugsaredevelopedandapproved/approvalapplications/abbreviatednewdrugapplicationandagenerics/ucm126389.htm, accessed 2/15/2017.

- 22. Colloca L. Nocebo effects can make you feel pain. Science 2017;358:44-44. 10.1126/science.aap8488 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Weissenfeld J, Stock S, Lüngen M, Gerber A. The nocebo effect: a reason for patients’ non-adherence to generic substitution? Pharmazie 2010;65:451-6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kesselheim AS, Bykov K, Avorn J, Tong A, Doherty M, Choudhry NK. Burden of changes in pill appearance for patients receiving generic cardiovascular medications after myocardial infarction: cohort and nested case-control studies. Ann Intern Med 2014;161:96-103. 10.7326/M13-2381 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kesselheim AS, Misono AS, Shrank WH, et al. Variations in pill appearance of antiepileptic drugs and the risk of nonadherence. JAMA Intern Med 2013;173:202-8. 10.1001/2013.jamainternmed.997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Privitera MD, Welty TE, Gidal BE, et al. Generic-to-generic lamotrigine switches in people with epilepsy: the randomised controlled EQUIGEN trial. Lancet Neurol 2016;15:365-72. 10.1016/S1474-4422(16)00014-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ting TY, Jiang W, Lionberger R, et al. Generic lamotrigine versus brand-name Lamictal bioequivalence in patients with epilepsy: A field test of the FDA bioequivalence standard. Epilepsia 2015;56:1415-24. 10.1111/epi.13095 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hansen RA, Qian J, Berg RL, et al. Comparison of outcomes following a switch from a brand to an authorized versus independent generic drug. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2018;103:310-7. 10.1002/cpt.591 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Desai R, Sarpatwari A, Dejene S, et al. Assessing the Post-marketing Safety of Authorized Generic Drug Products. Paper presented at Substitutability of Generic Drugs: Perceptions and Reality’ Workshop, Food & Drug Administration, Silver Spring, MD 2016. https://www.jhsph.edu/research/centers-and-institutes/center-of-excellence-in-regulatory-science-and-innovation/news-and-events/substitutability-of-generic-drugs-perceptions-and-reality.html [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hansen RA, Qian J, Berg R, et al. Comparison of Generic‐to‐Brand Switchback Rates Between Generic and Authorized Generic Drugs. Pharmacotherapy 2017;37:429-37 10.1002/phar.1908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Sarpatwari A, Choudhry NK, Avorn J, Kesselheim AS. Paying physicians to prescribe generic drugs and follow-on biologics in the United States. PLoS Med 2015;12:e1001802. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Greene JA, Kesselheim AS. Why do the same drugs look different? Pills, trade dress, and public health. N Engl J Med 2011;365:83-9. 10.1056/NEJMhle1101722 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]