Abstract

ProMED-mail (ProMED) was launched in 1994 as an email service to identify unusual health events related to emerging and re-emerging infectious diseases and toxins affecting humans, animals and plants. It is used daily by public health leaders, government officials at all levels, physicians, veterinarians and other healthcare workers, researchers, private companies, journalists and the general public. Reports are produced and commentary provided by a global team of subject matter experts in a variety of fields including virology, parasitology, epidemiology, entomology, veterinary and plant disease specialists. ProMED operates 24 hours a day, 7 days a week and has over 83 000 subscribers, representing every country in the world. Additionally, ProMED disseminates information via its website and through social media channels such as Twitter and Facebook as well as through RSS feeds. Over the last 22 years, it has been the first to report on numerous major and minor disease outbreaks including SARS, MERS, Ebola and the early spread of Zika. ProMED is transparent, apolitical, open to all and free of charge, making it an important and longstanding contributor to global health surveillance.

Keywords: Emerging infectious diseases, EpiCore, Outbreaks, ProMED-mail, Surveillance

Introduction

ProMED-mail (ProMED) was launched in 1994 as an email list to identify unusual health events related to emerging and re-emerging infectious diseases and toxicities affecting humans, animals and plants. A groundbreaking venture into using non-traditional or informal information sources to generate reports of outbreaks, the efficacy of this approach has been demonstrated repeatedly.1–3 ProMED was also, from the beginning, built around the One Health concept that recognizes the intersection of diseases in humans, animals and plants.

From its beginnings with only 40 members, ProMED has grown during the last 22 years to over 83 000 subscribers in more than 200 countries. ProMED is used by a wide range of individuals and organizations. These include public health leaders, government officials at all levels, physicians, veterinarians and other healthcare workers, researchers, private companies, journalists and the general public. Funded by a mix of grants, generous donations from supporters around the world and the International Society for Infectious Diseases (ISID), ProMED is transparent, apolitical, open to all and free of charge, making it an important part of the global public health community.

Structure

ProMED is based on innovative and informal disease surveillance, which allows it to disseminate information faster than traditional surveillance systems. By relying on local media, professional networks and on-the-ground experts, ProMED is able to highlight occurrences of emerging infectious diseases and outbreaks to its subscribers in near real-time. Reports are curated by specialist moderators who provide expert commentary, supply references to previous reports and to the scientific literature, and put the report in perspective for a diverse readership.4 These reports are simultaneously sent out to subscribers via email and posted to ProMED's website,5 which receives thousands of visits each day. Reports are also disseminated by social media, RSS feeds and smartphone apps.

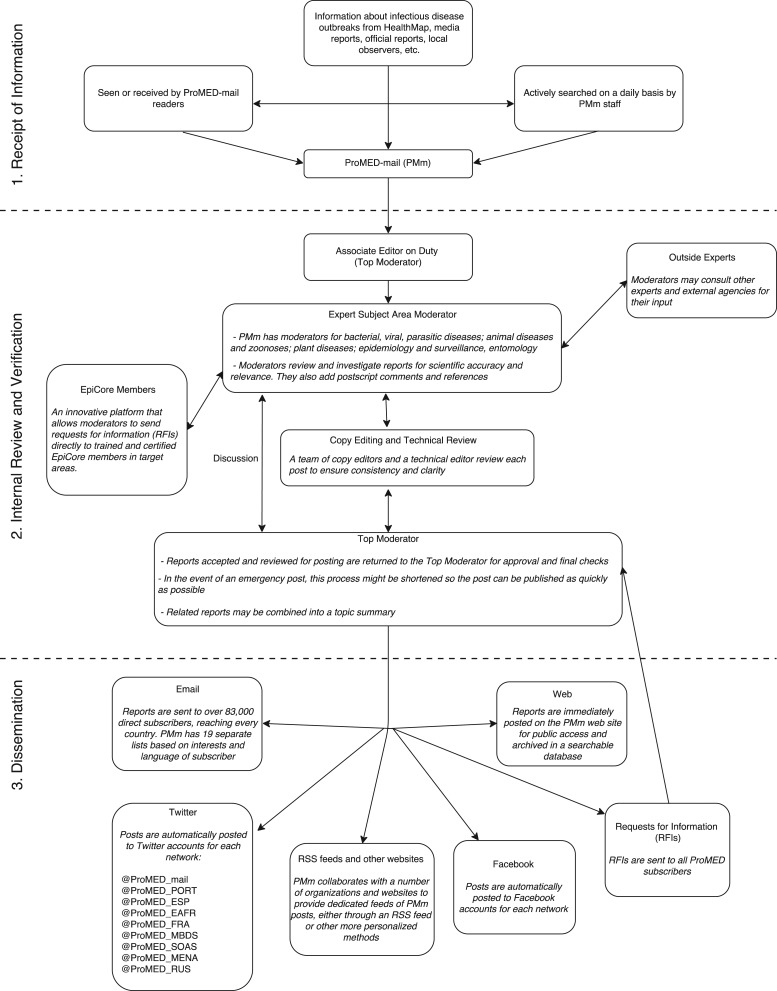

ProMED is composed of one global network and eight regional networks that operate in multiple languages including French, Spanish, Portuguese, Russian and Arabic. Subscribers are able to choose which lists they wish to receive, whether in real-time or as a digest, and additionally posts focused only on plants, zoonotic and animal diseases or posts that relate only to disease occurrence (without commentary and discussion). The specialist moderators (experts in specific subject matter or in regional diseases) are located in 37 countries and are constantly scanning for, reviewing and posting information to the network. Figure 1 shows the locations of moderators, staff and volunteers. ProMED reports data on outbreaks globally, 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, averaging eight outbreak reports per day. In order to maintain a level of consistency, as well as highlight the most important events of the day, ProMED staff carefully consider each post and aim for quality of reporting and accuracy over quantity of posts. Figure 2 shows the ProMED information flowchart, detailing the process that each piece of information goes through prior to being posted on ProMED.

Figure 1.

Map of ProMED-mail moderators, staff and volunteers.

Figure 2.

ProMED-mail information flowchart (adapted and updated from Madoff 2004).13 PMm: ProMED-mail; RFI: request for information; RSS: rich site summary; ProMED-EAFR (English language posts focusing on Anglophone Africa); ProMED-ESP (Spanish language posts focusing on Latin America); ProMED-FRA (French language posts focusing on Francophone Africa); ProMED-MBDS (English language posts focusing on the Mekong Basin region of Southeast Asia); ProMED-MENA (English language posts with summaries in Arabic focusing on the Middle East); ProMED-PORT (Portuguese language posts focusing on Latin America); ProMED-RUS (Russian language posts focusing on the independent states of the former Soviet Union); ProMED-SOAS (English language posts focusing on South Asia).

While ProMED is one of the oldest digital surveillance systems, it is certainly not the only one. Barboza et al.6 describe six internet-based biosurveillance systems, including ProMED. The systems include both human-curated, such as ProMED, and automated. The authors explored the strengths and limitations of each when compared to disease events reported in the 2010 French Institute for Public Health Surveillance weekly international epidemiological bulletin. Barboza et al.6 found that ProMED tended to score highly on its ability to detect confirmed disease outbreaks, as well as to detect these outbreaks before they were publicized in the weekly international epidemiology bulletin. A more recent paper by Bijkerk et al.7 analyzed the ten sources, including ProMED, used by the Netherlands Early Warning Committee to identify threats from abroad. They found that ProMED, along with the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control Round Table Report, were the most complete sources and that when combined they reported “95% of all threats a timely manner”.7 These findings corroborate ProMED's own experiences with being the first to report on numerous events over the past decades, also described below.

EpiCore

In 2014, ISID and ProMED, along with Skoll Global Threats Fund, HealthMap, and Training Programs in Epidemiology and Public Health Intervention Network (TEPHINET), began work on another innovative tool for disease surveillance, the EpiCore program.8 EpiCore was created to build a network of field epidemiologists and health professionals who can validate reported and suspected outbreaks. ProMED moderators send requests for information (RFIs) directly to EpiCore members in a specific area of the world, whether country or region. These volunteers then use their professional networks and other resources available to them to offer further data, confirmation of facts, or to correct information. All of the information is submitted through EpiCore's secure online reporting platform. When someone applies to become an EpiCore member, they must provide information about their professional qualifications and location as well as undergo training that is verified by the EpiCore program manager. However, in an effort to protect them as well as their contacts, EpiCore members are able to respond to RFIs anonymously, provide their information but ask it not be included in the report, or allow their name to be associated with the report.

While ProMED has always welcomed a feedback loop and encouraged subscribers to submit reports and information of interest, EpiCore has brought participation in ProMED to a new level. In the past, the response rates of ProMED RFIs to the general subscriber lists have been low with relatively few comments or additional information submitted. Through EpiCore, targeted RFIs are reaching a dedicated group that is eager to help gather further information and thus enhance ProMED's surveillance and reporting abilities.

Fully launched in March 2016, EpiCore has grown rapidly and currently includes more than 1800 members in 136 countries. The specialties of the EpiCore membership reflect ProMED's One Health approach with experts in animal, environmental and human health all represented. ProMED moderators consistently rate the responses they receive as being helpful and include these responses in follow-up posts. This demonstrates the added benefit of consulting the EpiCore community. According to membership surveys carried out in February and March 2017, most members report that they have greatly enjoyed their role so far. As EpiCore continues to grow, further opportunities for its members to contribute are being explored.

Successes

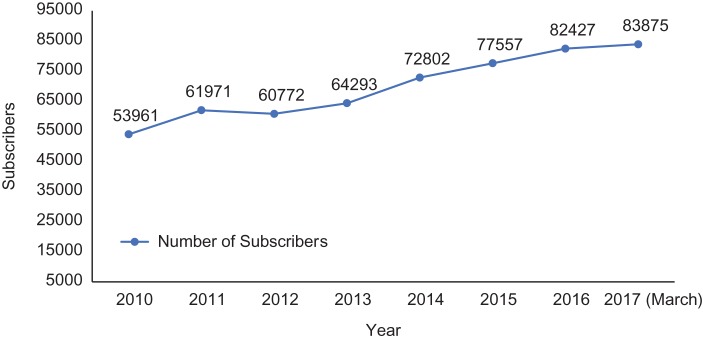

The strength and popularity of ProMED has grown considerably since it began in 1994. Over the past six years, since 2010, subscribership has increased by nearly 30 000 readers (Figure 3). The decline in subscribership in 2012 was due to removing duplicates and inactive email addresses; since that time, this is now done on a regular basis. In addition, the number of posts per day has been steadily rising, as can be seen in Table 1. While this table represents only the global English network, a similar increase can be observed on the regional networks as well.

Figure 3.

Total number of ProMED-mail email subscribers by year; 2010 to March 2017.

Table 1.

ProMED-mail global network total annual posts and posts per day

| Year | Posts | Posts/day |

|---|---|---|

| 2010 | 2613 | 7.2 |

| 2011 | 2588 | 7.1 |

| 2012 | 2930 | 8.0 |

| 2013 | 2924 | 8.0 |

| 2014 | 3035 | 8.2 |

| 2015 | 3154 | 8.6 |

| 2016 | 3327 | 9.1 |

ProMED has also become more prominent on social media in recent years. ProMED's main Facebook page has over 4400 followers and the main Twitter account (@ProMED_mail) counts more than 6800 Twitter followers, regularly adding over 100 new followers a month since early 2016. Thousands of others access ProMED daily through iOS and Android smartphone apps, via RSS feeds or from the website. ProMED also includes a feature on both the apps and the website allowing the public to send information and links to reports, news stories and other resources. When the information is provided and permission given, ProMED always acknowledges the origin of these contributions as it recognizes the strength of the general public.

ProMED has also worked hard to expand the number and location of networks and moderators to include those where emerging diseases and outbreaks are particularly concerning such as Francophone Africa and South-East Asia. In the past ten years, ProMED has added ProMED-MENA (Middle East and North Africa), ProMED-SOAS (South Asia), ProMED-EAFR (Anglophone Africa) and ProMED-FRA (Francophone Africa).

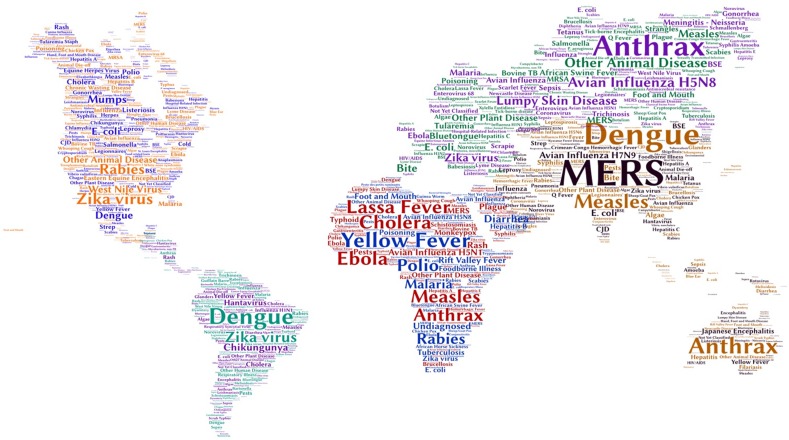

In order to show the broad scope of outbreaks and infectious disease events going on in the world, ProMED creates and publicizes word clouds on a quarterly basis on social media. These word clouds are based on all posts in the global ProMED network in the given time period and the size of the text corresponds to how many posts relate to that disease or event. The words are grouped by region but are not necessarily placed directly in the countries where the disease or outbreak occurred. Figure 4 is an end of year world cloud comprising all the posts from the global ProMED network from 01 January 2016 to 31 December 2016.

Figure 4.

Word cloud showing the most popular ProMED-mail topics by region from 01 January 2016 to 31 December 2016.

Table 2 shows the top five diseases reported in each region, along with how many posts this resulted in and the percentage this represented of total posts in the region on the ProMED global list. While there are differences in the number of total posts per region, with North America, Asia and Oceania showing at least double that of other regions, the percentages show that in fact there is a wide range of diseases being reported in each region as most of the top five diseases reported make up less than 10% of the total number of posts. The large percentage of post on yellow fever in Africa can be tied directly to the 2016 yellow fever outbreak in Angola. Similarly, the large number of posts on dengue and Zika virus in the South and Central America regions correspond to outbreaks there in 2016.

Table 2.

Top five reported diseases with number of pertinent posts and percentage of total posts in each region based on number of ProMED-mail global list posts from 1 January 2016 to 31 December 2016

| Africa (n=704) | Asia and Oceania (n=1481) | Central and South America (n=510) | Europe (n=683) | North America (n=1816) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yellow fever (188/26.7%) | MERS (160/10.8%) | Dengue (116/22.7%) | Anthrax (51/7.5%) | Rabies (116/6.4%) |

| Cholera (70/9.9%) | Dengue (133/9%) | Zika virus (103/20.1%) | Avian influenza H5N8 (47/6.8%) | Mumps (70/3.9%) |

| Ebola (66/9.4%) | Anthrax (101/6.8%) | Chikungunya (47/9.2%) | Disease (44/6.4%) | E. coli (60/3.3%) |

| Lassa fever (50/7.1%) | Measles (81/5.5%) | Hantavirus (31/6.1%) | Lumpy skin disease (44/6.4%) | Zika virus (58/3.2%) |

| Anthrax (37/5.3%) | Avian influenza H7N9 (62/4.2%) | Yellow fever (21/4.1%) | Zika virus (36/5.3%) | West Nile virus (57/3.1%) |

True to its purpose, ProMED has been one of the first outlets to report on numerous major and minor disease outbreaks over the years. Some examples include: cholera in Manila, Philippines (1996); meningococcal meningitis in Vietnamese immigrants in Russia (1997); fatal pediatric hand, foot and mouth disease in Malaysia (1998); yellow fever in Bolivia (1999); anthrax-contaminated heroin in Norway (2000); post 9/11 anthrax mail attacks (2001); measles in Papua New Guinea (2002); severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) global outbreak (2003); Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) in Saudi Arabia (2012); undiagnosed hemorrhagic fever in Guinea, later confirmed as Ebola (2014); early Zika spread in the Americas (2015); highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) among poultry in Europe (2016).

In addition, ProMED has been involved in efforts to bring global attention directly to a cause or outbreak. In 2015 one of ProMED's co-founders, the late John (Jack) P. Woodall, became concerned with the growing yellow fever outbreak in Angola and its potential for spread. Through various publications, quotes in newspapers such as the New York Times and Scientific American, and constant updates through ProMED, Woodall kept warning the scientific community but perhaps more importantly, also offering a potential solution.9–12 In two published manuscripts (Woodall and Yuill11 and Calisher and Woodall9), as well as in newspaper articles, Woodall and his colleagues proposed the use of a fractional dose of yellow fever vaccine so that the 7 million vaccines in the stockpile could meet demand and avoid a pandemic. This strategy was adopted by WHO, and begun in Angola and surrounding countries in August 2016, effectively limiting the spread in Angola and preventing global spread.

Limitations and constraints

While ProMED has had many successes, and has grown tremendously over the past two decades, there remain constraints and limitations to the work being carried out. ProMED prides itself on being open access and free of charge, with the goal of being able to disseminate this important information transparently and without limitations. Factors that improve emerging disease reporting include ready access to the internet, freedom from political and legal constraints on the exchange of information, and a vigorous media. Part of the impetus for the development of ProMED's regional networks has been to enhance reporting in areas where these features were absent or underdeveloped. However, impediments to rapid and transparent reporting continue to exist in many areas of the globe.

One of ProMED's strengths could also be considered a limitation. The use of human moderators and curators instead of an algorithm or automation (as used by systems such as HealthMap or MEDISYS), means that the importance of an article or event is judged on a case-by-case basis and therefore determined by expert opinion. ProMED operates as a team and there are daily discussions between the moderators and editors regarding the content that is posted. Nonetheless, there is always the opportunity for personal bias to influence some of the choices made by moderators.

While the ProMED archive contains over 22 years of posts on emerging infectious diseases and outbreaks, it is not currently equipped to provide, in many instances, detailed epidemiological data. For example, ProMED often does not report case or death counts beyond what is included in the text of a post. In order to extract this information from ProMED posts in a systematic way further analysis is required.

A further constraint is that while ProMED has been actively working to expand and grow its networks, seeking to add moderators in key regions and countries, gaps remain. Limited resources mean that it takes careful planning and a selective approach to bring on new moderators and regions, as the goal is always to sustain any new network indefinitely.

Future developments

Despite the identified constraints, ProMED continues to make plans to improve and expand in order to fulfill its mission of rapid and complete reporting of important outbreaks. There is a need to fill regional gaps, particularly in hotspots for disease emergence but where access to information is incomplete. Greater coverage in Africa and China, for example, would be highly beneficial.

ProMED is also working to improve its user experience and incorporate images and graphics within posts. This requires balancing content with bandwidth constraints that remain limiting in many parts of the world, and is also limited by the high costs of technology development. One of the most recent additions has come from a collaboration between ProMED and the EcoHealth Alliance to include a dynamic timeline of events on ProMED posts. This timeline is currently only available on the website version of a post but it allows a user to see any past events linked to that disease or outbreak. Furthermore, if they are looking at a post that was published in the past, any events that may have occurred after that post will also appear on the timeline.

In order to serve the public health community in as many ways as possible, ProMED encourages the use of its data for research and public health purposes. Tens of thousands of emerging disease reports dating back to the 1990s are currently housed in its archives. Public access, however, is currently limited to a web search tool, although individual requests for more refined datasets are honored whenever possible. ProMED is continually working to enhance the accessibility and visualization of its data.

Conclusion

ProMED is a global digital disease surveillance system that embraces the One Health model and prides itself on being an innovator in the field. Since its inception in 1994, ProMED has worked to communicate on emerging diseases and outbreaks faster than traditional surveillance systems. Now in its 23rd year of operation, ProMED continues to be one of the longest standing and most active non-traditional emerging disease surveillance systems.

While there are limitations to the current power of the ProMED system, the documented successes over the past decades show the strength of its model and the drive of a small but dedicated staff. As ProMED continues to grow and expand in the coming years, it actively seeks collaborations with individuals and organizations that share its mission and values in the interests of global health.

Acknowledgments

Authors’ contributions: MC and LCM both conceived and drafted the paper. MC and LCM also critically revised the manuscript for intellectual content. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript. LCM is the guarantor of the paper.

Acknowledgements: ProMED is a program of the International Society for Infectious Diseases (ISID). We thank our staff and participants. The ISID receives support for ProMED from the Wellcome Trust, the Skoll Global Threats Fund, CRDF Global, OIE and generous donors. HealthMap provides in-kind support. Thank you to John Ramatowski of ISID for creating the word cloud in Figure 4.

Funding: None.

Competing interests: Not declared.

Ethical approval: Not required.

References

- 1. Brownstein JS, Freifeld CC, Madoff LC. Digital disease detection—harnessing the web for public health surveillance. N Engl J Med 2009;360:2153–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Chan EH, Brewer TF, Madoff LC et al. Global capacity for emerging infectious disease detection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2010;107:21701–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hartley DM, Nelson NP, Arthur RR et al. An overview of internet biosurveillance. Clin Microbiol Infect 2013;19:1006–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Madoff LC, Li A.. Web-based surveillance systems for human, animal, and plant diseases. Microbiol Spectr 2014;2:OH-0015-2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. ISID ProMED-mail. Brookline, MS, USA; International Society for Infectious Diseases; http://www.promedmail.org [accessed 01 June 2016]. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Barboza P, Vaillant L, Le Strat Y et al. Factors influencing performance of internet-based biosurveillance systems used in epidemic intelligence for early detection of infectious diseases outbreaks. PLoS One 2014;9:e90536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bijkerk P, Monnier A, Fanoy E et al. ECDC Round Table Report and ProMed-mail most useful international information sources for the Netherlands Early Warning Committee. Euro Surveill 2017;22:pii:30502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. EpiCore http://www.epicore.org [accessed 01 June 2017].

- 9. Calisher CH, Woodall JP. Yellow fever-more a policy and planning problem than a biological one. Emerg Infect Dis 2016;22:1859–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Woodall JP. Another pandemic disaster looms: yellow fever spreading from Angola. Pan Afr Med J 2016;24:107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Woodall JP, Yuill TM. Why is the yellow fever outbreak in Angola a “threat to the entire world”. Int J Infect Dis 2016;48:96–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Monath TP, Woodall JP, Gubler DJ, et al. Yellow fever vaccine supply: a possible solution. Lancet 2016;387:1599–1600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Madoff LC. ProMED-mail: an early warning system for emerging diseases. Clin Infect Dis 2004;39:227–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]