Abstract

Objective

To compare the effectiveness of current contralateral routing of signal technology (CROS) to bone-anchored implants in experienced bone anchored implant users with unilateral severe-profound sensorineural hearing loss.

Design

Prospective, within-subject repeated-measures comparison study

Setting

Tertiary referral center

Patients

Adult, English speaking patients (n=12) with severe-profound unilateral sensorineural hearing loss implanted with a bone-anchored implant for the indication of single-sided deafness.

Intervention

Subjects were fitted with contralateral routing of signal amplification and tested for speech in noise performance and localization error.

Outcome measures

Speech perception in noise was assessed using the BKB-SIN™ test materials. Localization was assessed using narrow band noises centered at 500 and 4000 Hz, as well as a broadband speech stimulus presented at random to the front hemifield by 19 speakers spatially separated by 10 degrees.

Results

There was no improvement in localization ability in the aided condition and no significant difference in performance with CROS versus BAI. There was a significant improvement in speech in noise performance for monaural listeners in the aided condition for speech poorer ear/noise better ear, speech front/noise front, and speech front/noise back. No significant difference was observed on performance with CROS versus BAI subjects.

Conclusions

Contrary to earlier studies suggesting improved performance of BAIs over CROS, the current study found no difference in performance in BAI over CROS devices. Both CROS and BAI provide significant benefit for monaural listeners. The results suggest that non-invasive CROS solutions can successfully rehabilitate certain monaural listening deficits, provide improved hearing outcomes and expand the reach of treatment in this population.

Keywords: Unilateral hearing loss, single-sided deafness, bone anchored implant, bone anchored hearing aid, contralateral routing of signal, BAI, BAHA, CROS, monaural listening

INTRODUCTION

Individuals with a severe-to-profound unilateral hearing impairment lose access to critical cues provided through binaural hearing. These cues provide key information regarding the timing and intensity of the signal, allowing a listener to perform complex tasks of auditory function such as the ability to determine the location of a sound and to separate speech from background noise1,2. As a consequence, monaural listeners are subject to reduced sound awareness, poor speech perception in noise, and inability to localize sounds1. Despite these handicaps, individuals with severe-profound unilateral hearing loss have gone largely untreated historically. This is due in part to the common misconception that monaural listeners have a low handicap/disability index3, and that normal hearing in one ear is sufficient for most everyday communication. On the contrary, several studies have shown that monaural listeners do in fact experience significant handicap and disability4-6 and consistently display poor performance on behavioral tasks of auditory function3,7-11. Additionally, limited treatment options for monaural listeners with inadequate outcomes resulted in lack of successful treatment in the population.

Early studies using contralateral routing of signal (CROS) hearing aids demonstrated that lifting the head-shadow can significantly improve listening in noise ability in monaural listeners12. Despite this benefit, CROS hearing aids did not find widespread use in this population. CROS hearing aids consist of a microphone that is placed at the impaired ear, which then routes the acoustic signal to a hearing aid worn in the normally functioning ear, requiring individuals with normal hearing in one ear to use two hearing aids. This along with acoustic limitations of the device led to complaints of occlusion in the better ear, poor sound quality, and discomfort13,14. As an alternative to CROS, bone anchored implants (BAI)7,8,15-17 were introduced for the treatment of unilateral sensorineural hearing loss in 2002. BAIs utilize a small titanium implant in the temporal bone on the impaired side that couples to an external processor. The implant utilizes transcranial bone conduction to send the signals of interest to the contralateral (normal) cochlea. This treatment approach overcame much of the limitations of early CROS devices leading to a sudden increase in treatment of monaural listeners. Studies comparing CROS and BAI devices have since suggested that the BAI system is superior to CROS technology for the treatment of unilateral severe-to-profound sensory-neural hearing loss3,7,8,10,16,17. Niparko et al.3 compared BAI to CROS for speech presented to the front in quiet, in noise, and with noise lateralized to the normal and impaired ears. Significant improvements were found in both BAI and CROS devices over the unaided condition, and BAI out performed CROS in quiet and when speech and noise were directed at the front. Interestingly, when noise was masking the better hearing ear, arguably the most challenging listening configuration for monaural listeners, there was no difference in device systems. Others also found no difference in BAI and CROS devices for lifting the head-shadow, although subjective measures suggested increased benefit with BAIs over CROS7,8,17. The interpretation of these comparative studies relied considerably on subjective report. The investigative design, where subjects rejected CROS prior to BAI, lacked internal validity related to selection bias. None of these studies included a reverse comparison of assessing BAI users’ performance post-operatively using CROS hearing devices. Lastly, early comparison studies of CROS versus BAIs in monaural listeners reflect outdated technology. Previous CROS devices suffered from audible transmission delays and required occlusion of the normal hearing ear, negatively affecting the only hearing ear. These acoustic limitations, which cannot be separated from the subjective reports of limited benefit, have been largely overcome. New CROS systems utilize an open fitting, no longer occluding the normal hearing ear. Additionally, new CROS systems allow for wireless transmission the acoustic signal improving both signal transmission and aesthetic appeal.

Current studies of performance are warranted to determine the benefit of BAIs versus non-invasive, less expensive CROS treatment options in the monaural listener population. We have recently shown no significant difference in objective performance or subjective outcomes when comparing a group of CROS hearing aid users to a group of BAI users18. Our results clearly suggest that CROS hearing aid systems are similarly capable of rehabilitating the deficits associated with monaural listening, as are BAIs. However, we have also shown that monaural listeners display a high inter-subject variability on tasks of speech perception in noise9. Based on our earlier studies in BAI users9,19, it is expected that variations in performance are individual specific and independent of device use. Specifically, the degree of benefit associated with lifting the head-shadow does not vary within the same subject with respect to current technology, and is characterized by each individual’s auditory processing capabilities. It is possible that average performance between these two groups does not accurately reflect this inter-subject variability and the inability to detect differences in performance may be attributed to the study design. As such, we sought to replicate early studies comparing CROS and BAI where comparisons in device performance are made within subject. Further, we sought to use previously implanted BAI users rather than failed CROS users as an additional modification to earlier comparison studies7,8,17.

The purpose of this investigation was to compare the benefits of current wireless CROS technology to BAI technology in monaural listeners using a BAI. We hypothesized that non-invasive wireless CROS technology is capable of providing similar benefit to the more invasive BAI system for unilateral severe-profound hearing loss. In particular, we compared the speech perception in noise and localization abilities of monaural listeners using a percutaneous BAI to the same subject group using a CROS hearing aid.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

University of Miami Institutional Review Board approval was obtained for this study. Adults, 18 years of age and older, who were primary English speakers and using a BAI as treatment for unilateral severe-profound sensorineural hearing loss were prospectively enrolled for study. All subjects used a percutaneous implant system. The normal hearing ear must have demonstrated a pure tone average of < 25 dB HL at 500, 1000, 2000, and 3000 Hz. The impaired ear was confirmed to be clinically unaidable as defined by severe-profound threshold responses with poor word recognition ability defined as < 40% on NU-6 speech perception tests20. Results were compared to a control group demonstrating normal hearing bilaterally as defined by a pure tone average of less than 25dBHL at 500, 1000, 2000, and 4000 Hz. In total, 45 normal hearing subjects, and 12 BAI subjects were included for study.

Procedures

This study was designed as a prospective, within-subject repeated-measures experiment in which each subject served as his/her own control. Experienced unilateral severe-profound sensorineural hearing loss subjects using a BAI and with normal hearing in the contralateral ear (< 25dB) were studied in the BAI aided and the CROS aided listening conditions using localization and measures of speech in noise perception between test conditions. Level of impairment was compared to normal hearing adults (n=45) demonstrating thresholds < 25 dB from 250 – 8000 Hz bilaterally.

Subjects were evaluated in two conditions. Each condition was randomized to either the BAI or CROS condition. Each phase consisted of two intervals with random assignment of either SIN testing or localization testing. Subjects underwent randomized assignment of the testing in either the CROS or BAI condition, including randomized intervals of SIN versus localization testing. All subjects were allowed a minimum 15-minute break between intervals. For the second condition, subjects underwent testing in either the CROS or BAI condition, alternate to condition one. The second condition also included two randomized intervals identical in set-up and procedure as condition one. All subjects were evaluated acutely with no adaptation to the CROS condition.

The CROS hearing aid system wirelessly transmits full audio bandwidth (130 Hz–6.0 kHz) from the CROS transmitter to the hearing aid worn in the normal ear by way of omnidirectional microphone. All subjects used a Phonak Audeo V50® CROS open fit hearing aid system. Devices were fit using NAL1 prescriptive targets and gain prescribed according to better ear thresholds. During testing conditions, volume control was inactive to ensure prescriptive targets were maintained. All subjects underwent real-ear measures to ensure absence of occlusion in the normal ear and that transmission of the CROS signal approximates the real ear unaided response21. Although exact fitting methods cannot be replicated across devices, gain for BAIs were prescribed according to better ear hearing thresholds. Eleven subjects were users of Cochlear Baha® processors consisting of three Divino, four BP100 and four Baha 5 processors. One subject used an Oticon Medical Ponto Pro processor. As with CROS subjects, the volume control was inactive and the omnidirectional mode was maintained for BAI subjects.

Localization

Methods related to the study of localization error have been detailed previously18. Briefly, stimuli were presented in a custom 4m×4m×2m sound booth with 19 loudspeakers setup at a radius of 1.3m and spatially separated by 10°, spanning +/− 90° Stimuli were generated by a custom-designed MATLAB (Mathworks, Natick, MA) front-end for TDT RX8 real-time multichannel processor (Tucker Davis Technologies, Alachua, FL), and a series of Crown Audio CT-8150 8-channel amplifiers. Laboratory testing was calibrated as specified by ISO 8253-2:2009 by warble-tone RMS-intensity measurements. Stimuli generated were corrected for individual speaker calibration characteristics. Localization stimuli included a narrowband 350-ms, 1/3 octave noise centered at 500Hz, a narrowband 350-ms, 1/3 octave noise centered at 4kHz, and a broadband 189-ms male-voiced ‘hey’, band-passed from 100–8000 Hz. Each stimulus was presented three times at 65 dB SPL roved by +/− 4dB for a total of 171 stimuli per subject per condition. The perceived locations of the sound sources were recorded utilizing a custom-designed, arduino-based 24-pushbutton feedback panel. Results were compared to normal hearing controls as previously described.

Speech in noise

Recorded commercially available BKB-SINTM 22 sentences were used for assessment of speech in noise perception. The BKB-SIN™ uses Bamford-Kowal-Bench sentences23 recorded in four-talker babble to estimate signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) loss. SNR loss is defined as the increase in SNR required by a listener to obtain 50% correct words in sentences compared to normal performance24. A minimum of two lists of ten sentences were completed for each condition and averaged to determine the SNR level in decibels (dB) required to obtain 50% accuracy. Speech stimuli were presented at 62 dB SPL. The test was conducted in the sound field and subjects were evaluated in the speech front/noise front (0°/0° azimuth), speech poorer ear/noise better ear (90°/270° azimuth), speech better ear/noise poorer ear (270°/90° azimuth), and speech front/noise back (0°/180° azimuth) configurations. All test protocols were repeated in the aided conditions (with CROS or BAI on) to characterize performance changes in this condition.

Statistical analyses were performed using Wilcoxon signed rank tests for nonparametric data and paired-sample. Statistical significance was set to p > 0.05. Power analysis indicated that a minimum of 7 subjects were required to be sufficiently powered at 90% utilizing a previously described BKB-SIN minimally clinically important difference of 1.8 dB. All analyses were performed using SAS JMP™ software (version 12.1; Cary, NC).

RESULTS

Twelve subjects and 45 controls were included in the analysis. The subjects ranged in age from 41–78 years (mean, 62 years ± 4 years) and the controls ranged in age from 22 – 57 years (mean, 31 years ± 9 years). There were eight female and four male monaural test subjects. Seven left ears and five right ears were impaired. Etiology of hearing loss varied across subjects including acoustic neuroma, sudden hearing loss, Meniere’s disease, iatrogenic, and meningitis. BAI users had a mean device use of 6.2 years (SD, ± 0.72 years).

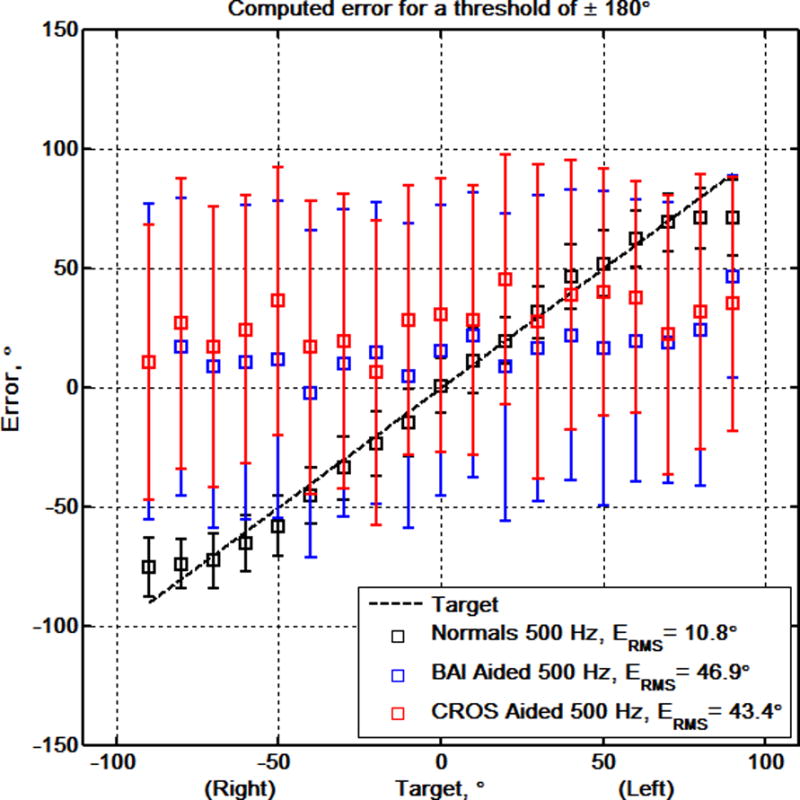

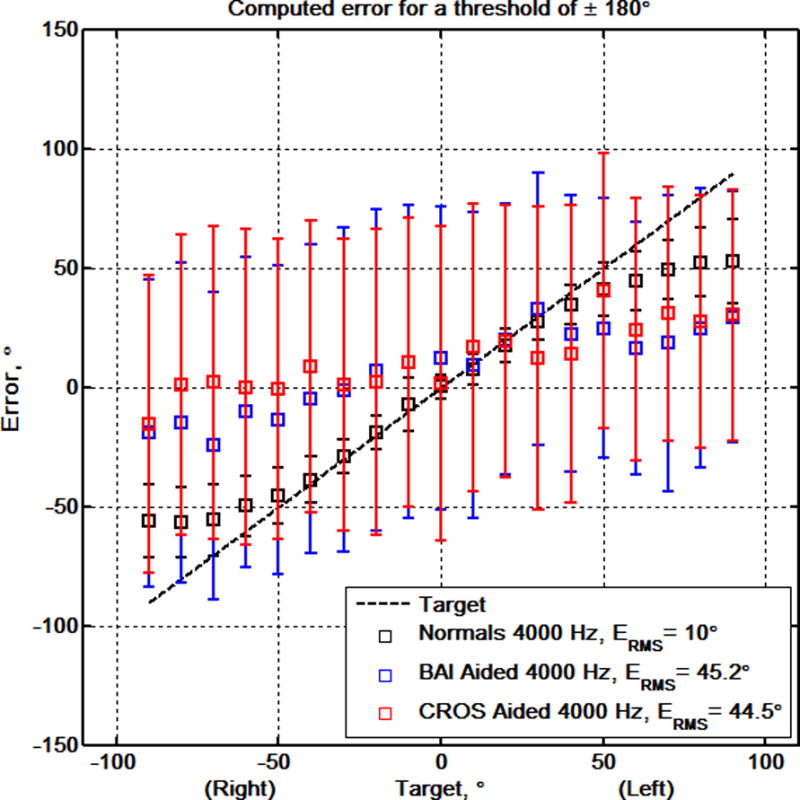

Compared to normal hearing controls, monaural listeners displayed high degrees of localization error. For the broadband signal voiced ‘hey’ unaided RMS error was observed at 42.3° versus 6.8° in normal hearing listeners. For the 1/3 octave 500 Hz narrowband signal unaided RMS error was observed at 44.7° versus 10.8° in normal hearing listeners. For the 1/3 octave 4000 Hz unaided RMS error was observed at 46.7° versus 10° in normal hearing listeners. Aided localization results can be found in Figure 1. There was no improvement in localization ability for either the BAI or CROS aided condition for any of the presented stimuli. No significant difference in aided localization performance was observed between the BAI and CROS aided conditions (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Localization performance represented in RMS error for aided BAI (blue) versus CROS (red) performance for the voiced ‘hey’, 500 Hz 1/3 oct., & 4000 Hz 1/3 oct noise, respectively. Aided responses are plotted against normative (black).

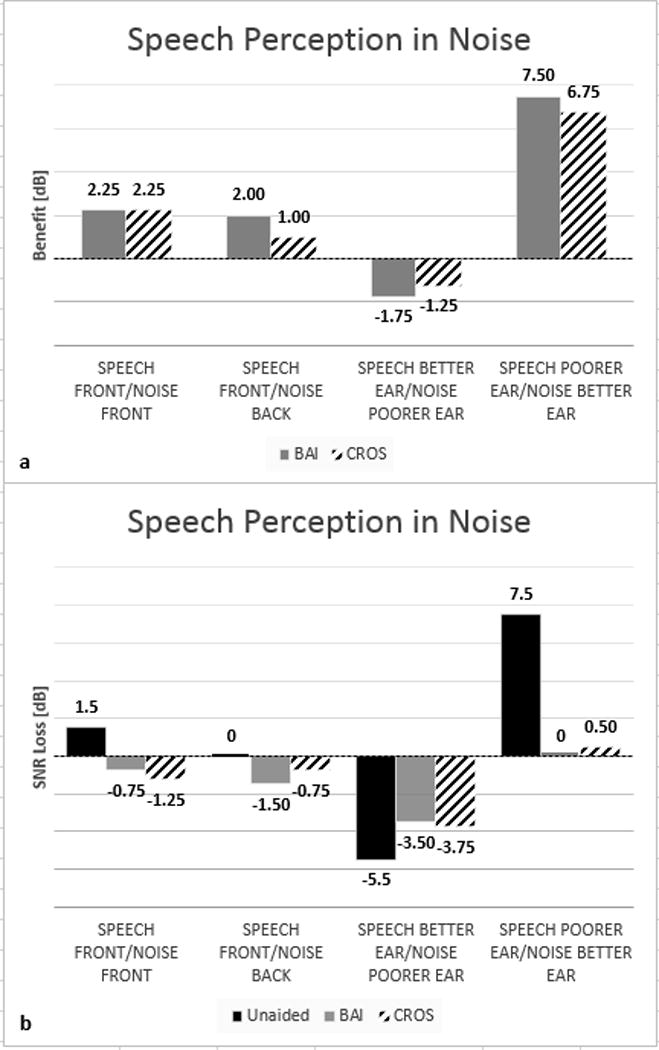

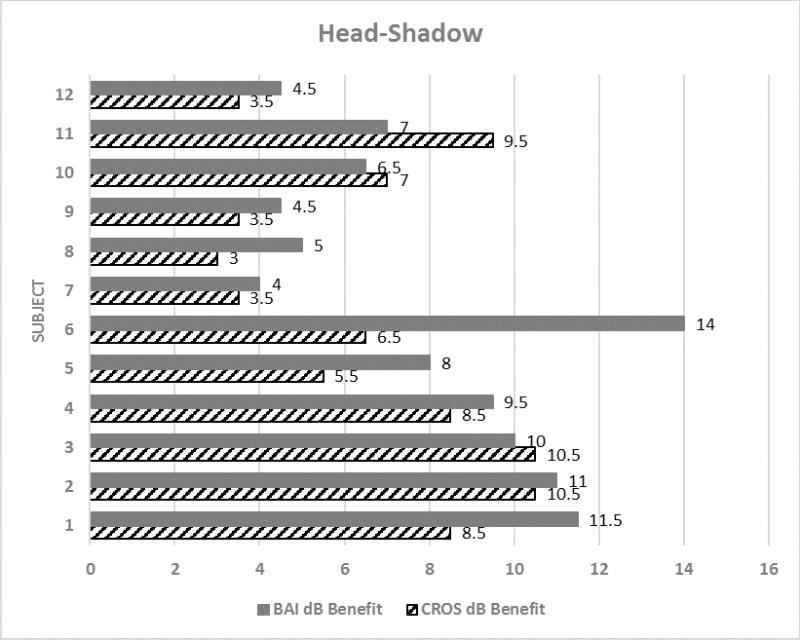

The median SNR benefit for CROS aided and BAI aided conditions for each of the four experimental configurations is presented in Figure 2a where the larger the dB value the better the performance. Figure 2b shows the median absolute performance in terms of SNR loss for the unaided and aided conditions across the four speech in noise test configurations. Monaural listeners are at the greatest disadvantage for listening when the speaker is at the impaired ear and noise is masking the better ear. In this configuration, performance was essentially equal with median aided benefit of 7.5 dB in the BAI aided condition and 6.75 dB in the CROS aided condition. The same observation was maintained for speech front/noise front (BAI = 2.25 dB, CROS = 2.25 dB) and speech front/noise back (BAI = 2.0 dB, CROS = 1.00 dB). Likewise, the decrement observed for speech directed at the better ear while noise is directed at the BAI or CROS was not significantly different (BAI = −1.75 dB, CROS = −1.25 dB). For Figure 2b, better performance corresponds with lower SNRs. A significant improvement in SNR loss was observed from the unaided to CROS aided and BAI aided condition for the speech front/noise front (p<0.01; p<0.01), speech front/noise back (p<0.05; p<0.01), and speech poorer ear/noise better ear (p<0.0005; p<0.0005) configurations (Figure 2b). A slight decrement in performance was observed for both the CROS and BAI aided conditions when speech was directed at the better ear and noise was at the poorer ear (p<0.01). Analysis of absolute aided performance as well as overall aided benefit resulted in no statistically significant difference between BAI and CROS test conditions for any of the listening configurations (p > 0.05, Wilcoxon signed rank; Table 1). Post-hoc analysis resulted in an observed power of 0.977 based on the calculated effect size of 1.3 dB. Individual subject data can be found in Figure 3 demonstrating both the within and between subject differences for lifting of the head-shadow (speech poorer ear/noise better ear).

Figure 2.

SNR benefit for CROS aided and BAI aided conditions for each of the four experimental configurations is presented in (a) where larger dB values represent better performance. SNR loss for the unaided and aided conditions is presented in (b) where better performance corresponds with lower SNRs. No significant difference between systems is observed in aided benefit or absolute performance across the listening configurations (p>0.05, Wilcoxon signed-rank).

Table 1.

Statistical significance for absolute CROS and BAI performance from unaided to the aided condition, absolute aided BAI versus CROS performance, and overall dB benefit for CROS and BAI for the speech front/noise front (0°/0° azimuth), speech front/noise back(0°/180° azimuth), speech better ear/noise poorer ear (90°/270° azimuth), and speech poorer ear/noise better ear (90°/270° azimuth) configurations.

| CROS | BAI | CROS v BAI | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Speech front/noise front | 0°/0° | p<0.01 | p<0.01 | p>0.05 |

| Speech front/noise back | 0°/180° | p<0.05 | p<0.01 | p>0.05 |

| Speech better ear/noise poorer ear* | 270°/90° | p<0.01 | p<0.01 | p>0.05 |

| Speech poorer ear/noise better ear | 90°/270° | p<0.0005 | p<0.0005 | p>0.05 |

Figure 3.

Individual subject data demonstrating the inter-subject variability in degree of benefit (dB) that occurs in monaural listeners for lifting of head-shadow (speech poorer ear/noise better ear). Inter-subject differences for device performance are also presented.

DISCUSSION

We have previously reported that CROS provides similar benefit to BAIs for monaural listeners25. This within subject comparison of experienced BAI users with wireless CROS technology supports our earlier findings. Both BAI and CROS serve to reroute the signal of interest from the impaired ear to the normal hearing ear. The head creates an acoustic shadow for sounds arriving from different locations. Sounds arrive earlier and at higher intensities for the ear closest to the signal whereas a reduction in amplitude and a timing delay occurs at the far ear. In normal hearing, this acoustical phenomenon benefits the listener as they are able to rely on the more favorable signal to noise ratio that results from the head attenuating interfering signals (i.e. noise). In monaural listeners, this advantage is lost as all sounds arrive to the normal hearing ear at the same time and intensity. This is further complicated with increasing noise, particularly when noise is interfering with the monaural ear and speech is presented to the impaired ear. For lateralized signals (±90° azimuth) the head shadow results approximately a 6 dB attenuation26. The negative impact of this on speech perception in noise in monaural listeners is clearly demonstrated in Figure 2. Our findings demonstrate that both BAI and CROS are successful at lifting this head-shadow effect. However, review of individual data (Figure 3) shows that while differences between BAI and CROS performance do not reach statistical significance, a greater number of patients experienced increased benefit with the BAI device than do those with the CROS device. In one subject, the benefit with the CROS is 6.5 dB while the BAI benefit is 14 dB resulting in 7.5 dB greater performance with BAI than with the CROS. It is important to note that the patient receives benefit with the CROS consistent with the impairment expected by the head-shadow effect26. This suggests that while the majority of patients will likely have similar performance with BAIs and CROS, there are some patients who may experience increased benefit with one device over the other. Pre-treatment assessment19 of head-shadow benefit with CROS and BAI devices can performed using the speech poorer ear/noise better ear test configuration to determine individualized predictors regarding invasive versus non-invasive device selection.

Early reports of benefit in monaural listeners with CROS hearing devices suggested that lifting of the head-shadow resulted in significant benefit to this population14. However, the acoustic limitations of early CROS systems resulted in complaints of poor sound quality and discomfort with device use13,14. Some have attributed poor acceptance of CROS technology to the inability to restore binaural function11 as rerouting the signal to the normal hearing ear does not provide distinct binaural processing for advanced auditory processing abilities such as localization. The success of BAIs in the monaural listening population contradicts this and suggests that binaural function may not be a requirement for successful rehabilitation of some monaural listeners. Further, it suggests that the inability to restore binaural function may not be a limiter to seeking treatment.

These results suggest that both BAIs and CROS hearing devices improve speech perception in noise for the speech front/noise front (0°/0° azimuth), speech front/noise back (0°/180° azimuth), and speech poorer ear/noise better ear (90°/270° azimuth) listening configurations. Our findings, however are not in agreement with earlier studies3,7,8,17 suggesting a distinct advantage of BAIs over CROS devices. Niparko and colleagues3 suggested that the improved performance of BAIs over CROS devices was a result in greater efficiency in bone-conducted sound. The head-shadow effect is most significant for high-frequency sounds above 1000 Hz27, and transcranial attenuation has been shown to be greatest in the 3–4 KHz region28,29. This would suggest that transcranial bone-conducted sound is at a distinct disadvantage for rerouting of signal, specifically for high frequency signals. In accordance with this, studies of transcranial attenuation have failed to demonstrate any correlation to speech perception abilities25. Due to the head shadow effect, the greatest deficit for monaural listeners is incurred by high frequency sounds, which directly contributes to clarity of speech. The shorter wavelengths are subject to absorption and reflectance by the head resulting in as much as a 20 dB attenuation of the signal27. It is more likely that earlier CROS systems resulted in a disruption of the ability to use the monaural ear effectively8. Along these lines, Wazen and colleagues16 attributed the natural sound provided by BAIs and lack of interference in monaural ear hearing to the increased benefit observed over CROS devices. Now that both BAI and CROS systems allow for an open ear, this negative effect has been greatly reduced. While the acute test design of the present study did not allow for valid assessment of subjective outcomes, this is supported by recent between group comparisons of contemporary CROS hearing aid users to BAI users where subjective outcomes, including device benefit, satisfaction, and post-treatment disability were comparable18.

As observed here, the largest benefit for BAI and CROS systems occurs when the signal of interest is directed at the impaired ear and noise is masking the better hearing ear. Likewise, unaided monaural listeners are the most debilitated by this listening condition. Although listeners are able to benefit from both BAI and CROS systems for speech directed at the front or the better ear, the degree of this benefit is nominal which in part, may account for the variability in reported benefit for such systems7,11,16,30-32. It is plausible that benefit may be a function of lifestyle and listening demands. In low noise environments where the normal hearing ear can easily access the target signal, the benefit of rerouting is marginal. However, for those individuals who are more often in noisy environments and/or dynamic listening situations where a speaker of interest may be positioned at the impaired ear, rerouting of signal proves to provide significant benefit. According to the authors22, normal hearing adults are expected to obtain a mean performance of −2.5 dB +/− 1.6 dB on the BKB-SIN™ test. At −5.5 dB, our subject group outperformed the reported normal hearing performance for speech directed at the better hearing ear. In this listening condition, the monaural listener is at an advantage as the head shadow creates an acoustic barrier for noise coming from the opposite ear, thereby providing increased separation of masker and target. When speech was directed to the front where the normal hearing ear can actively contribute to speech understanding, results did not fall far outside the range for normal hearers (1.5 dB and 0.0 dB, respectively). Conversely, for speech directed at the impaired ear where the head acts as an acoustic barrier to speech and noise is masking the normal hearing ear, we observed a deficit of more than 8 dB compared to normal hearing performance. Specifically, in this condition the monaural listener would require the signal to be more than 8 dB louder than a normal hearing individual to achieve similar speech perception abilities in noise.

Both CROS and BAI systems have undergone considerable technological and design changes since the first introduction of BAIs for monaural listeners. For example, the introduction of transcutaneous implant systems has allowed for bone conduction stimulation while avoiding the permanent disruption of the skin required with percutaneous implants. Although percutaneous implant systems disrupt the skin, they allow for the most direct path of bone conduction. Transcutaneous systems have been shown to further attenuate the signal with the most significant reduction in the high frequencies33. To control for this unknown variable, the present study was limited to percutaneous BAI users only. Provided that monaural listeners are most dependent on high frequency information, transcutaneous stimulation in this population may result in poorer outcomes than presented here. Further study of transcutaneous implant systems are warranted to better understand their role in the treatment of monaural listeners.

Unlike previous studies comparing CROS to BAI in monaural listeners, we did not provide the BAI user with an adaptation period to CROS listening. Despite the considerable experience subjects had with BAI listening, performance in CROS aided condition was not significantly different from the BAI condition. Both the CROS and the BAI serve to reduce the head-shadow effect through rerouting of signals from the impaired ear to the normal hearing ear. Improving the signal to noise ratio for signals presented to the impaired ear to reduce the head-shadow experienced by monaural listeners should not require adaptation as this is purely a physical phenomenon. Despite this, our subjects did trend towards better performance with their BAI, although this did not reach significance, as it was approximately 1 dB for most subjects. For BKB-SIN™ test materials the difference in scores must be greater than 2.2 dB for one list pair in each of two conditions to be significant at the 95% confidence interval or greater than 1.8 to be significant at the 80% confidence interval22. It is possible that with increased exposure listeners will experience improved performance with the CROS system. The finding that CROS hearing aid systems can provide similar benefit to BAI in experienced users without an adaptation further supports the consistency in performance between these treatment options.

CONCLUSIONS

Experienced unilateral severe-profound sensorineural hearing loss subjects using a BAI and with normal hearing in the better hearing ear (<25dB) were studied in the BAI aided and CROS aided conditions using localization and measures of SIN perception. Level of impairment was compared to the subject’s own performance in the unaided condition. The results reported in this study support the findings of others that monaural listeners benefit from reduction in the head shadow effect, specifically when speech is directed at the impaired ear, and do not gain any localization benefit from rerouting the signal from the impaired ear3,8,10,17. When compared to their own performance, monaural listeners demonstrate no statistically significant difference in BAI and CROS performance. As others and we have shown3,7,10,18, rerouting of signal does not result in restoration of binaural function, but serves to reduce the head-shadow effect. Our findings reveal that monaural listeners receive significant objective benefit as measured by behavioral tests of speech perception in noise for both BAI and CROS devices. The results of this study provide evidence that it is possible to achieve satisfactory hearing results in monaural listeners with wireless CROS technology. Wireless CROS provides a non-invasive, less expensive solution for monaural listeners, thereby expanding access to rehabilitation in this population.

Footnotes

Presented in part at Association for Research in Otolaryngology, 2017 Baltimore, MD

Hillary Snapp, Au.D., Ph.D. is an advisory board member for Advanced Bionics, LLC

References

- 1.Giolas TG, Wark DJ. Communication problems associated with unilateral hearing loss. The Journal of speech and hearing disorders. 1967;32(4):336–343. doi: 10.1044/jshd.3204.336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sargent EW, Herrmann B, Hollenbeak CS, Bankaitis AE. The minimum speech test battery in profound unilateral hearing loss. Otology & neurotology. 2001;22(4):480–486. doi: 10.1097/00129492-200107000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Niparko JK, Cox KM, Lustig LR. Comparison of the bone anchored hearing aid implantable hearing device with contralateral routing of offside signal amplification in the rehabilitation of unilateral deafness. Otology & neurotology. 2003;24(1):73–78. doi: 10.1097/00129492-200301000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Silverman CA, Silman S, Emmer MB, Schoepflin JR, Lutolf JJ. Auditory deprivation in adults with asymmetric, sensorineural hearing impairment. Journal of the American Academy of Audiology. 2006;17(10):747–762. doi: 10.3766/jaaa.17.10.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sano H, Okamoto M, Ohhashi K, Iwasaki S, Ogawa K. Quality of life reported by patients with idiopathic sudden sensorineural hearing loss. Otology & neurotology. 2013;34(1):36–40. doi: 10.1097/MAO.0b013e318278540e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Augustine AM, CS, Thenmozhi K, Rupa V. Assessment of auditory and psychosocial handicap associated with unilateral hearing loss among Indian patients. Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2013;65(2):120–125. doi: 10.1007/s12070-012-0586-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bosman AJ, Hol MK, Snik AF, Mylanus EA, Cremers CW. Bone-anchored hearing aids in unilateral inner ear deafness. Acta oto-laryngologica. 2003;123(2):258–260. doi: 10.1080/000164580310001105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lin LM, Bowditch S, Anderson MJ, May B, Cox KM, Niparko JK. Amplification in the rehabilitation of unilateral deafness: speech in noise and directional hearing effects with bone-anchored hearing and contralateral routing of signal amplification. Otology & neurotology. 2006;27(2):172–182. doi: 10.1097/01.mao.0000196421.30275.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Snapp H, Angeli S, Telischi FF, Fabry D. Postoperative validation of bone-anchored implants in the single-sided deafness population. Otology & neurotology. 2012;33(3):291–296. doi: 10.1097/MAO.0b013e3182429512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wazen JJ, Ghossaini SN, Spitzer JB, Kuller M. Localization by unilateral BAHA users. Otolaryngology--head and neck surgery. 2005;132(6):928–932. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2005.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Arndt S, Aschendorff A, Laszig R, et al. Comparison of pseudobinaural hearing to real binaural hearing rehabilitation after cochlear implantation in patients with unilateral deafness and tinnitus. Otology & neurotology. 2011;32(1):39–47. doi: 10.1097/MAO.0b013e3181fcf271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harford E, Barry J. A Rehabilitative Approach to the Problem of Unilateral Hearing Impairment: The Contralateral Routing of Signals Cros. The Journal of speech and hearing disorders. 1965;30:121–138. doi: 10.1044/jshd.3002.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Williams VA, McArdle RA, Chisolm TH. Subjective and objective outcomes from new BiCROS technology in a veteran sample. Journal of the American Academy of Audiology. 2012;23(10):789–806. doi: 10.3766/jaaa.23.10.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ericson H1 SI, Högset O, Devert G, Ekström L. Contralateral routing of signals in unilateral hearing impairment. A better method of fitting. Scand Audiol. 1988;17(2):111–116. doi: 10.3109/01050398809070699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.FDA. Summary and Certification. 510(k) Summary Number K021837. 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wazen JJ, Spitzer JB, Ghossaini SN, et al. Transcranial contralateral cochlear stimulation in unilateral deafness. Otolaryngology--head and neck surgery. 2003;129(3):248–254. doi: 10.1016/S0194-5998(03)00527-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hol MK, Bosman AJ, Snik AF, Mylanus EA, Cremers CW. Bone-anchored hearing aid in unilateral inner ear deafness: a study of 20 patients. Audiology & neuro-otology. 2004;9(5):274–281. doi: 10.1159/000080227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Snapp HA, Holt FD, Liu X, Rajguru SM. Comparison of Speech-in-Noise and Localization Benefits in Unilateral Hearing Loss Subjects Using Contralateral Routing of Signal Hearing Aids or Bone-Anchored Implants. Otology & neurotology. 2017;38(1):11–18. doi: 10.1097/MAO.0000000000001269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Snapp HA, Fabry DA, Telischi FF, Arheart KL, Angeli SI. A clinical protocol for predicting outcomes with an implantable prosthetic device (Baha) in patients with single-sided deafness. Journal of the American Academy of Audiology. 2010;21(10):654–662. doi: 10.3766/jaaa.21.10.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.AAO-HNSF. Committee on Hearing and Equilibrium guidelines for the evaluation of hearing preservation in acoustic neuroma (vestibular schwannoma). American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery Foundation, INC. Otolaryngology--head and neck surgery. 1995;113(3):179–180. doi: 10.1016/S0194-5998(95)70101-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dillon H. Hearing Aids. New York: Thieme; 2001. pp. 434–450. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bamford-Kowal-Bench Speech-in-Noise Test (version 1.03) [Audio CD] Elk Grove Village, IL: Author; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bench J, Kowal A, Bamford J. The BKB (Bamford-Kowal-Bench) sentence lists for partially-hearing children. British journal of audiology. 1979;13(3):108–112. doi: 10.3109/03005367909078884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Killion MC, Niquette PA, Gudmundsen GI, Revit LJ, Banerjee S. Development of a quick speech-in-noise test for measuring signal-to-noise ratio loss in normal-hearing and hearing-impaired listeners. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 2004;116(4 Pt 1):2395–2405. doi: 10.1121/1.1784440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Snapp HA, Morgenstein KE, Telischi FF, Angeli S. Transcranial Attenuation in Patients with Single-Sided Deafness. Audiology & neuro-otology. 2016;21(4):237–243. doi: 10.1159/000447044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tillman TW, Carhart R, Nicholls S. Release from multiple maskers in elderly persons. Journal of speech and hearing research. 1973;16(1):152–160. doi: 10.1044/jshr.1601.152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Middlebrooks JC, Green DM. Sound localization by human listeners. Annual review of psychology. 1991;42:135–159. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ps.42.020191.001031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stenfelt S. Transcranial attenuation of bone-conducted sound when stimulation is at the mastoid and at the bone conduction hearing aid position. Otology & neurotology. 2012;33(2):105–114. doi: 10.1097/MAO.0b013e31823e28ab. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nolan M, Lyon DJ. Transcranial attenuation in bone conduction audiometry. The Journal of Laryngology & Otology. 1981;95(6):597–608. doi: 10.1017/s0022215100091155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Faber HT, de Wolf MJF, Cremers CWRJ, Snik AFM, Hol MKS. Benefit of Baha in the elderly with single-sided deafness. Eur Arch Oto-Rhino-L. 2013;270(4):1285–1291. doi: 10.1007/s00405-012-2151-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schroder SA, Ravn T, Bonding P. BAHA in single-sided deafness: patient compliance and subjective benefit. Otology & neurotology. 2010;31(3):404–408. doi: 10.1097/MAO.0b013e3181d27cc0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pennings RJ, Gulliver M, Morris DP. The importance of an extended preoperative trial of BAHA in unilateral sensorineural hearing loss: a prospective cohort study. Clinical otolaryngology. 2011;36(5):442–449. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-4486.2011.02388.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Reinfeldt S, Hakansson B, Taghavi H, Eeg-Olofsson M. New developments in bone-conduction hearing implants: a review. Med Devices (Auckl) 2015;8:79–93. doi: 10.2147/MDER.S39691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]