cAMP signaling regulates Schwann myelination by a mechanism that is not clearly understood. The authors provide in vitro and in vivo data showing that cAMP shuttles HDAC4 into the nucleus, where it forms a complex with NcoR1/HDAC3 to repress the expression of c-Jun, inducing Schwann cell differentiation and myelin development.

Abstract

Schwann cells respond to cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) halting proliferation and expressing myelin proteins. Here we show that cAMP signaling induces the nuclear shuttling of the class IIa histone deacetylase (HDAC)–4 in these cells, where it binds to the promoter and blocks the expression of c-Jun, a negative regulator of myelination. To do it, HDAC4 does not interfere with the transcriptional activity of MEF2. Instead, by interacting with NCoR1, it recruits HDAC3 and deacetylates histone 3 in the promoter of c-Jun, blocking gene expression. Importantly, this is enough to up-regulate Krox20 and start Schwann cell differentiation program–inducing myelin gene expression. Using conditional knockout mice, we also show that HDAC4 together with HDAC5 redundantly contribute to activate the myelin transcriptional program and the development of myelin sheath in vivo. We propose a model in which cAMP signaling shuttles class IIa HDACs into the nucleus of Schwann cells to regulate the initial steps of myelination in the peripheral nervous system.

Introduction

Myelination allows saltatory conduction of action potentials and maintains axon integrity by providing trophic support. During early peripheral nervous system (PNS) development, immature Schwann cells associate with multiple axons but do not form myelin. Later some of these cells will sort large-caliber axons and wrap around them (Jessen and Mirsky, 2005). Signaling molecules on the surface of these axons will induce Schwann cells to differentiate. Interestingly, contact with axons can be overcome in vitro by increasing cAMP levels in Schwann cells (Salzer and Bunge, 1980), suggesting this second messenger has an in vivo role in myelination. Recently it has been shown that the activation of Gpr126 (a G-protein–coupled receptor expressed on the cell surface) increases intracellular cAMP, inducing Schwann cell differentiation and myelin development (Monk et al., 2009, 2011; Mogha et al., 2013; Petersen et al., 2015). cAMP activates protein kinase A (PKA) and the exchange protein directly activated by cAMP (Bacallao and Monje, 2013; Guo et al., 2013; Shen et al., 2014); however, how this induces Schwann cell differentiation and myelin gene expression still remains obscure. Intriguingly, cAMP down-regulates c-Jun, a basic leucine zipper domain transcription factor expressed by immature Schwann cells that negatively regulates the expression of the myelin master gene Krox20 (Monuki et al., 1989; Parkinson et al., 2008). Although c-Jun expression is low in adult nerves, it is strongly reexpressed after injury, enforcing differentiated cells to reprogram into repair Schwann cells, a phenotype that, although different in size and morphology (Gomez-Sanchez et al., 2017), shares the expression of some genes with immature Schwann cells (Arthur-Farraj et al., 2012; Fontana et al., 2012).

Histone deacetylases (HDACs) have crucial roles in development, mainly through their repressive influence on transcription. They are usually classified into four main families: classes I, IIa, IIb, and IV. In addition to these classical HDACs, mammalian genome encodes another group of structurally unrelated deacetylases known as class III HDACs or sirtuins (Haberland et al., 2009). Recently it has been elegantly shown that class I HDACs are pivotal for myelin development and nerve repair (Chen et al., 2011; Jacob et al., 2011a,b, 2014; Brügger et al., 2017). However, little is known about the role of other HDACs in this process. At variance with other members of the family, class IIa HDACs (4, 5, 7, and 9) are expressed in a restricted number of tissues and cell types (Parra, 2015). Also they have no prominent protein-deacetylase activity, as a pivotal tyrosine in the catalytic site is mutated to histidine (Lahm et al., 2007). Thus they cannot directly modulate gene transcription by affecting chromatin condensation. Indeed, class IIa HDACs work mainly as corepressors. Thus, it is known that the N-terminal domain of HDAC4 binds to Mef2-DNA complexes, blocking Mef2-dependent gene expression (Backs et al., 2011). In addition to Mef2, class IIa HDACs bind and regulate the activity of other transcription factors such as Runx2 and CtBP (Vega et al., 2004). Class IIa HDACs are required for the proper development of different tissues. It has been shown that HDAC4 deletion delays Runx2 down-regulation in chondrocytes and provokes premature ossification (Vega et al., 2004). By blocking several promoters critical for muscle differentiation, class IIa HDACs also control myogenesis (McKinsey et al., 2000). Biological activity of this family of proteins is mainly regulated by shuttling between the nucleus and cytoplasm. Phosphorylation of three conserved serines (Ser246, Ser467, and Ser632 in the human sequence) mediates its binding to the chaperone 14-3-3 protein and interferes with a nuclear importation sequence, promoting sequestration in the cytoplasm (McKinsey et al., 2000; Backs et al., 2006; Walkinshaw et al., 2013). cAMP-dependent PKA signaling has the opposite effect by indirectly interfering with serine phosphorylation, which blocks nuclear exportation (Walkinshaw et al., 2013). PKA also directly phosphorylates serine 265/266, hampering its binding to 14-3-3 (Ha et al., 2010; Liu and Schneider, 2013). Interestingly, it has been recently shown that the cAMP-induced nuclear shuttling of HDAC4 in vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs) represses c-Jun expression by a Mef2-dependent mechanism (Gordon et al., 2009).

Here we explore the possibility that class IIa HDACs mediate cAMP signaling and the establishment of the myelinating phenotype of Schwann cells. First we demonstrate that HDAC4 responds to cAMP by shuttling into the nucleus of Schwann cells. Second, we show that the down-regulation of HDAC4 (with shRNAi) interferes with the capacity of cAMP to down-regulate c-Jun and induce differentiation markers such as Krox20 and Periaxin. Importantly, we show that the expression of a constitutively active form of HDAC4 (HDAC4 3SA) is sufficient to block c-Jun expression. Our data show that once in the nucleus, HDAC4 recruits the complex NCoR1/HDAC3 and deacetylates histone 3 on the promoter of c-Jun to repress the expression of this gene. Strikingly, HDAC4 3SA expression is enough to induce Schwann cells to strongly express Krox20 and enter the myelin gene transcriptional program. Finally, by using Schwann cell–specific conditional knockouts (KOs), we show that class IIa HDAC4 and HDAC5 redundantly contribute to regulate myelin development in vivo.

Results

HDAC4 mediates cAMP-dependent repression of c-Jun in cultured Schwann cells

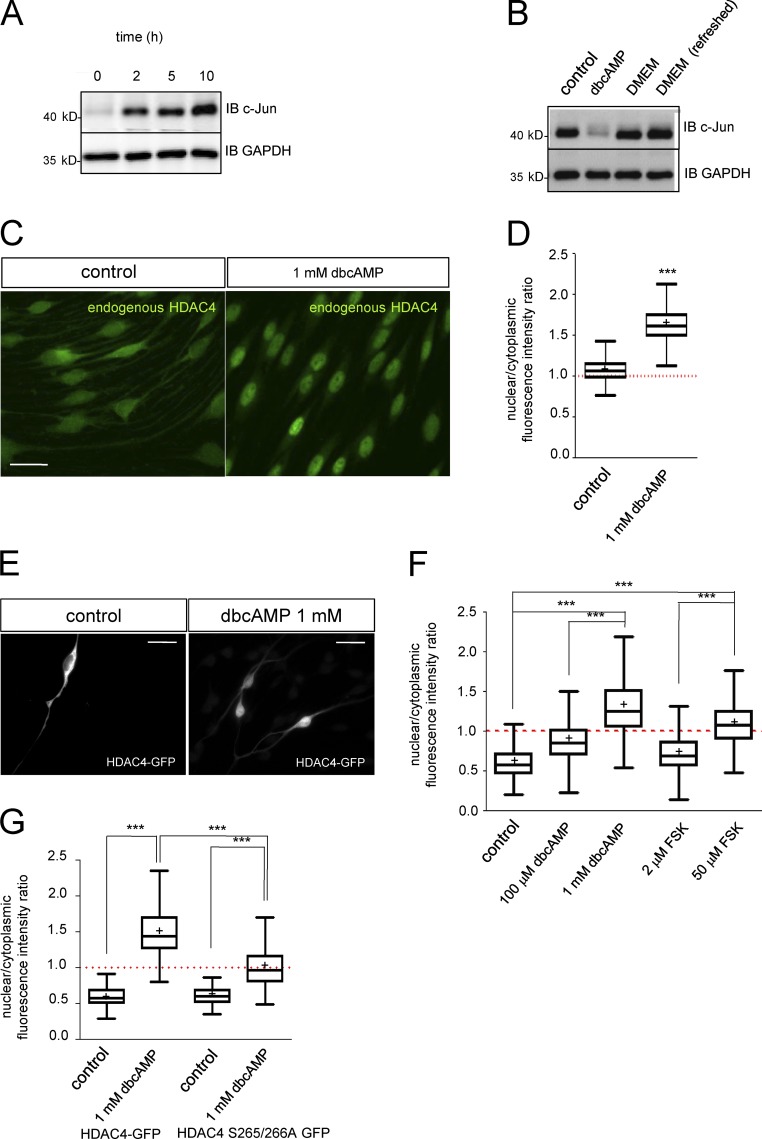

Cultured rat Schwann cells express high levels of c-Jun but neither Krox-20 nor myelin proteins. When exposed to a sustained high concentration of cAMP analogues, they lose the typical bipolar shape and adopt a flat morphology with low c-Jun and high Krox20 and other differentiation markers (Parkinson et al., 2004, 2008; Monje et al., 2009, 2010; Bacallao and Monje, 2013). It has been shown that cAMP produces a drop in c-Jun mRNA by Northern blot (Monuki et al., 1989). A similar result was obtained by RT–quantitative PCR (qPCR), suggesting cAMP activates a signaling pathway that represses the transcription of this gene and decreases protein levels (Fig. S1, A and B). When the cAMP analogue was removed, c-Jun protein was detected as early as 2 h later, reaching a maximum 10 h later (Fig. 1 A). Refreshing the medium every 30 min produced no change in c-Jun levels, suggesting that this gene is reexpressed in a cell-autonomous way, in agreement with previous results (Monje et al., 2010; Fig. 1 B). Together these data suggest that cAMP activates and maintains a transcriptional repressive mechanism that blocks c-Jun gene expression in Schwann cells.

Figure 1.

Strong and sustained cAMP signaling induces nuclear shuttling of HDAC4 in Schwann cells. (A) Kinetics of c-Jun reexpression. Immunoblot (IB) for c-Jun from extracts of cultured rat Schwann cells incubated in SATO medium for 2, 5, and 10 h after down-regulation of c-Jun by 1 mM dbcAMP. (B) Reexpression of c-Jun is cell autonomous. After incubation with 1 mM dbcAMP, Schwann cells were incubated in DMEM for 10 h (DMEM) or for the same period but replacing the DMEM every 30 min (DMEM refreshed). The same amount of protein was loaded in each lane and immunoblotted with anti–c-Jun. GAPDH was used as a loading control. (C) cAMP signaling induces shuttling of HDAC4 into the nucleus of Schwann cells. Cultured rat Schwann cells were incubated in SATO medium (control) or in SATO + 1 mM dbcAMP for 24 h, fixed, and submitted to immunofluorescence with anti-HDAC4. (D) A Tukey’s box plot of the ratio between the density of fluorescence in the nucleus and the cytoplasm of 900 cells per condition (three different experiments from three different cultures) is shown. Data were analyzed with the unpaired t test (two-sided). (E) To better determine HDAC4 response to cAMP signaling, rat Schwann cells were transfected with the HDAC4-GFP construct and incubated for 24 h in SATO medium with the indicated compounds. (F) Only prodifferentiating (but not mitogenic) concentrations of dbcAMP and forskolin (FSK) were able to efficiently induce HDAC4-GFP nuclear shuttling (>1). A Tukey’s box plot of the nuclear/cytoplasmic fluorescence intensity ratio for 900 cells per condition of three different experiments is shown. Data were analyzed with the one-way ANOVA, Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. (G) PKA phosphorylation of Ser265 and Ser266 mediates HDAC4 shuttling in response to cAMP signaling. HDAC4 S265/266A GFP–transfected rat Schwann cells were incubated in SATO medium or SATO + 1 mM dbcAMP for 24 h. Shuttling was determined as before and compared with HDAC4-GFP wild-type transfected cells. As shown, Ser265 and Ser266 elimination partially prevented cAMP-induced nuclear shuttling of HDAC4. Tukey’s box plot of the nuclear/cytoplasmic fluorescence intensity ratio for 300 cells per condition of three different experiments is shown. Data were analyzed with the one-way ANOVA, Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001. Mean is plotted as a “+.” Bars, 25 µm.

VSMCs respond to blood vessel injury by expressing c-Jun and changing to an “activated phenotype” that contributes to vessel repair (Owens et al., 2004). Interestingly, c-Jun up-regulation and the transition to the activated phenotype can be blocked by cAMP. This treatment shuttles HDAC4 into the nucleus and blocks the transcriptional activity of Mef2 on the promoter of c-Jun (Gordon et al., 2009). To determine whether a similar mechanism regulates c-Jun in Schwann cells, we first examined the expression of these proteins in cultured Schwann cells and in vivo (in mouse sciatic nerves). As shown in Fig. S2 A, HDAC4 and Mef2 are expressed by sciatic nerves and in both proliferating and differentiated cultured rat Schwann cells. In addition, Schwann cells express other members of the class IIa HDAC group, such as HDAC5 and HDAC7. We could not, however, detect the mRNA for HDAC9 (Fig. S2 B). We also explored the expression of these genes in mouse sciatic nerves during postnatal development. Interestingly, mRNA for HDAC4 is highly expressed at P2 and decreases as myelination proceeds. In contrast, HDAC5 and HDAC7 are more stably expressed during this period (Fig. S2, C–E).

We next examined how HDAC4 responds to cAMP signaling in Schwann cells. In control cells, HDAC4 immunoreactivity was found widely distributed in Schwann cells with similar signal intensity in both cytoplasmic and nuclear compartments (nuclear/cytoplasmic ratio [rn/c] = 1.066 ± 0.004; Fig. 1 C). Interestingly, 1 mM dbcAMP (a concentration high enough to down-regulate c-Jun and induce Schwann cell differentiation) dramatically translocated immunoreactivity to the nucleus (rn/c = 1.631 ± 0.008; Fig. 1 B). To obtain further insight, an HDAC4-GFP fusion construct was transfected in Schwann cells. In control conditions (SATO medium), HDAC4-GFP was mainly excluded from the nucleus and retained in the cytoplasm (rn/c = 0.623 ± 0.012; Fig. 1, E and F). When Schwann cells were exposed to 1 mM dbcAMP, HDAC4-GFP shuttled into the nucleus (rn/c = 1.347 ± 0.017), although there was still protein in the cytoplasm (probably because of the high level of protein expression driven by the cytomegalovirus [CMV] promoter). 20 µM forskolin (which strongly induces cAMP biosynthesis and induces Schwann differentiation; Arthur-Farraj et al., 2011) produced a similar effect (rn/c = 1.117 ± 0.012). Importantly, concentrations of dbcAMP (100 µM) and forskolin (2 µM) that do not induce differentiation but have a strong mitogenic effect on Schwann cells were not able to efficiently shuttle HDAC4-GFP into the nucleus (rn/c = 0.892 ± 0.012 and 0.722 ± 0.008, respectively; Fig. 1 F).

cAMP activates PKA that can induce HDAC4 shuttling by both direct phosphorylation of Ser265 and Ser266 or by indirect inhibition of Ser246, Ser467, and Ser632 phosphorylation (Ha et al., 2010; Liu and Schneider, 2013; Walkinshaw et al., 2013). To dissect the contribution of each mechanism, we mutated Ser265 and Ser266 simultaneously to Ala in HDAC4-GFP and explored shuttling in response to cAMP. As shown in Fig. 1 G, this mutant was not very efficiently shuttled in response to cAMP (rn/c = 1.012 ± 0.018 for the Ser265/266Ala vs. 1.479 ± 0.018 for the wild type), demonstrating a role for direct phosphorylation by PKA in the nuclear translocation of HDAC4 in Schwann cells. However, it still showed a response to cAMP signaling when compared with control (rn/c = 0.595 ± 0.018 for the Ser265/266Ala in SATO). Together, our data indicate that although the direct phosphorylation of Ser265/266 by PKA regulates the HDAC4 nuclear shuttling in Schwann cells, other indirect mechanisms are also involved.

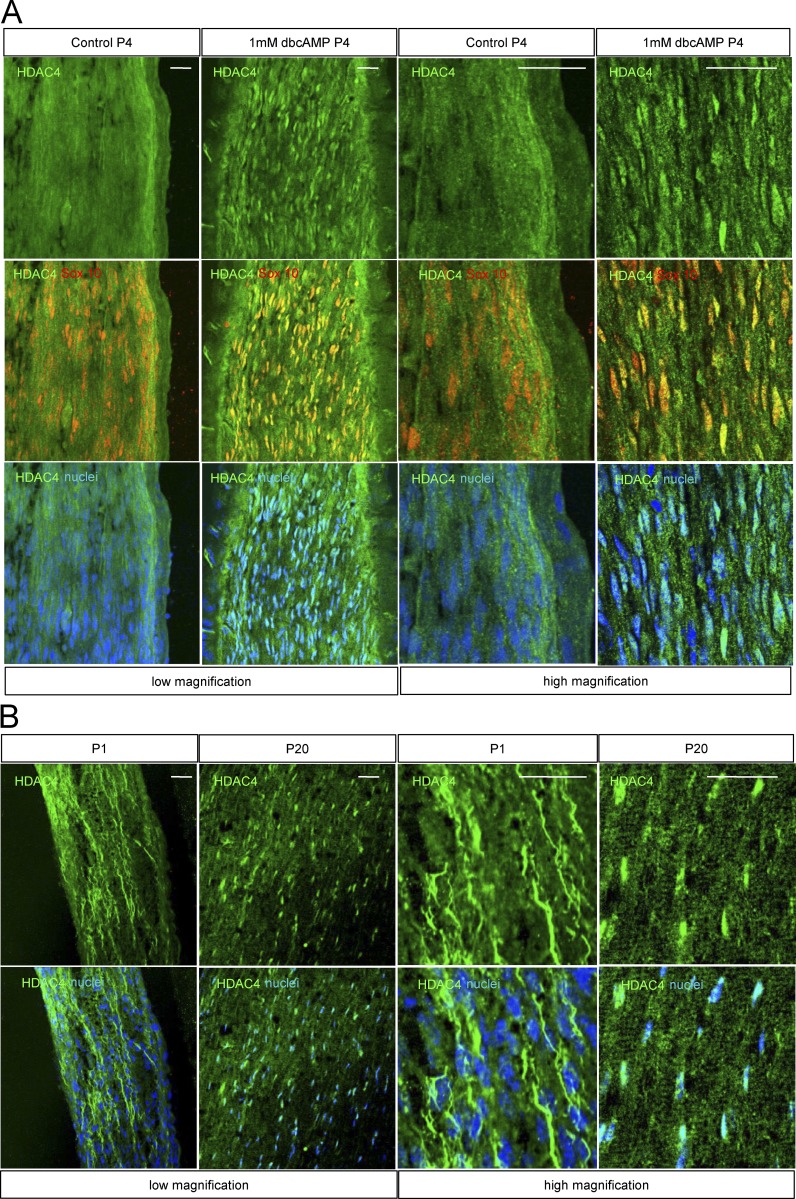

To check whether cAMP signaling also induces HDAC4 shuttling in vivo, P4 rats were anesthetized, and the sciatic nerve was exposed and covered with a solution of 1 mM dbcAMP in saline. The same experiment was performed with saline alone as a control. After 1 h of treatment, rats were sacrificed and sciatic nerves extracted and processed for immunolabeling with anti-HDAC4 antibody. As shown in Fig. 2 A, whereas anti-HDAC4 labeling was diffuse, suggesting a predominantly cytoplasmic distribution, cAMP incubation induced a change toward a predominantly nuclear accumulation of HDAC4. Interestingly, HDAC4 shows a predominantly cytoplasmic pattern at P1 (incipient myelination) that changes to a predominantly nuclear distribution in the P20 (advanced myelination) mouse sciatic nerve (Fig. 2 B). Together these data suggest that in vivo also, HDAC4 responds to cAMP signaling by shuttling into the Schwann cell nucleus.

Figure 2.

HDAC4 nuclear shuttling in vivo. (A) P4 rat pups were anesthetized, and the sciatic nerve exposed and immersed in a solution of 1 mM dbcAMP in saline for 1 h. A control with saline was also performed. Then nerves were removed fixed and submitted to immunofluorescence with anti-HDAC4 antibody. Schwann cells were identified by Sox10 expression (red). Nuclei were counterstained with Hoechst. Representative confocal images at low and high magnification are shown. (B) Distribution pattern of HDAC4 in the sciatic nerve changes during postnatal development. At P1, anti-HDAC4 immunofluorescence is widely distributed, whereas at P20, immunoractivity has mainly accumulated in the nucleus. P1 and P20 wild-type mice sciatic nerves were fixed and submitted to immunofluorescence with the anti-HDAC4 antibody. Nuclei were counterstained with Hoechst and images obtained with a confocal microscope. Bars, 25 µm.

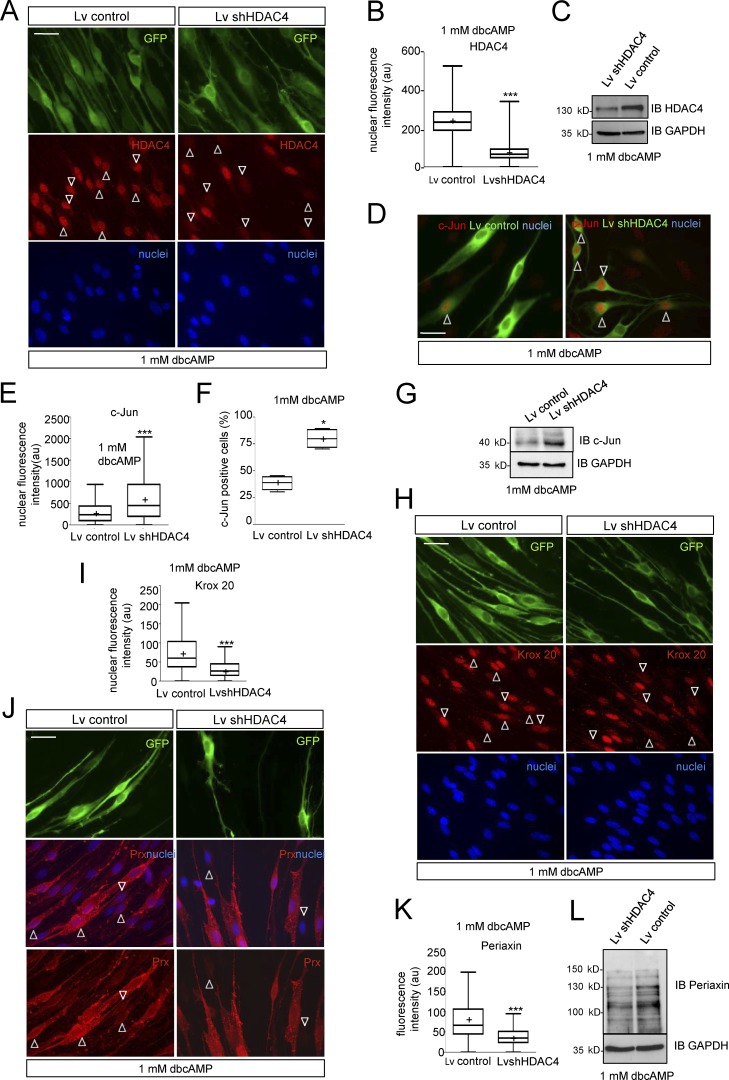

So far our data show that cAMP signaling induces a PKA-mediated shuttling of HDAC4 into the nucleus of Schwann cells. To determine whether this translocation is involved in c-Jun down-regulation, we performed loss of function experiments. For simplicity, we first used RT4D6 cells, a rat schwannoma–derived cell line that retains many of the properties of Schwann cells (Hai et al., 2002). Interestingly, the shRNAi-mediated block of HDAC4 expression prevented the ability of dbcAMP to down-regulate c-Jun in these cells. In contrast, this transcription factor was efficiently down-regulated in cells transfected with a control shRNAi (shEGFP) and in nontransfected cells (Fig. S3 A). Next, we performed related experiments using cultured rat Schwann cells. We generated lentiviral particles harboring the shRNAi for HDAC4 (lentivirus [Lv] shHDAC4). To identify the infected cells, Lv was engineered to incorporate GFP. A GFP-expressing Lv was used as control (Lv control). Schwann cells were infected and incubated in SATO medium with 1 mM dbcAMP for 24 h. As shown in Fig. 3 A, the anti-HDAC4 immunofluorescence signal notably decreased in Lv shHDAC4 but not in Lv control infected cells (immunofluorescence intensity = 73.17 ± 2.65 and 240.80 ± 4.57 a.u., respectively; Fig. 3 B). A similar result was obtained by Western blot (Fig. 3 C). Interestingly, whereas anti–c-Jun immunoreactivity was 309.4 ± 14.29 a.u. in Lv control–infected Schwann cells, it increased to 676.4 ± 37.95 a.u. in Lv shHDAC4–infected cells (Fig. 3, D and E). A similar result was obtained when c-Jun expression was evaluated as the percentage of c-Jun–positive cells (30.25 ± 2.53% in control vs. 63.50 ± 3.57% in Lv shHDAC4–infected cells; Fig. 3 F) or Western blot (Fig. 3 G). Loss of HDAC4 function prevented not only cAMP-induced c-Jun down-regulation but also induction of Krox20 (immunofluorescence intensity = 74.89 ± 1.89 a.u. for Lv control–infected cells and 30.36 ± 0.78 a.u. for Lv shHDAc4–infected Schwann cells; Fig. 3, H and I) and Periaxin (81.29 ± 2.28 in control vs. 42.63 ± 1.52 in Lv shHDAC4–infected cells; Fig. 3, J–L).

Figure 3.

Loss of HDAC4 function prevents cAMP-induced Schwann cell differentiation. (A) Cultured rat Schwann cells were infected with a Lv expressing an shRNAi for HDAC4 (Lv shHDAC4), incubated in SATO medium with 1 mM dbcAMP, and submitted to immunofluorescence with anti-HDAC4. Nuclei were counterstained with Hoechst. Infected cells were identified by GFP expression. As shown, the Lv shHDAC4 (but not the empty Lv control) blocks HDAC4 expression (arrowheads). (B) Tukey’s box plot of the HDAC4 fluorescence intensity for 300 cells per condition (three different experiments from three different cultures) is included. Data were analyzed with the unpaired t test (two-sided). (C) Immunoblot with anti-HDAC4 confirmed the results. (D) Loss of HDAC4 prevents cAMP-mediated c-Jun down-regulation. Whereas most of the Lv shHDAC4–infected cells retained c-Jun expression after 24 h of 1 mM dbcAMP treatment, most of the Lv control–infected ones were c-Jun negative. (E) A Tukey’s box plot of the nuclear c-Jun fluorescence intensity for 450 cells per condition from four different experiments is shown. Data were analyzed with the unpaired t test (two-sided). (F) We also show a Tukey’s box plot of counts of c-Jun–positive cells expressed as a percentage of the total. These data were analyzed with the Mann-Whitney U test. (G) Finally, the immunoblot with anti–c-Jun confirmed the results. GAPDH was used as a loading control. (H) Loss of HDAC4 prevents Krox20 induction. Schwann cells were infected and incubated as described in A. As is shown, Lv shHDAC4–infected Schwann cells (arrowheads) lost the capacity to induce Krox20 in response to cAMP, whereas the Lv control–infected ones did not. (I) A Tukey’s box plot of the nuclear Krox20 fluorescence intensity for 900 cells per condition, from three different experiments, is shown. Data were analyzed with the unpaired t test (two-sided). (J) Periaxin expression was also impaired in these cells. (K) A Tukey’s box plot of the Periaxin cytoplasmic fluorescence intensity for 600 cells per condition, from three different experiments, is shown. Data were analyzed with the unpaired t test (two-sided). (L) Immunoblot with anti-Periaxin confirmed the results. GAPDH was used as a loading control. *, P < 0.05; **P, < 0.01; ***P, < 0.001. Mean is plotted as a “+.” Bars, 25 µm.

HDAC4 binds to the c-Jun promoter and down-regulates gene expression by a Mef2-independent mechanism

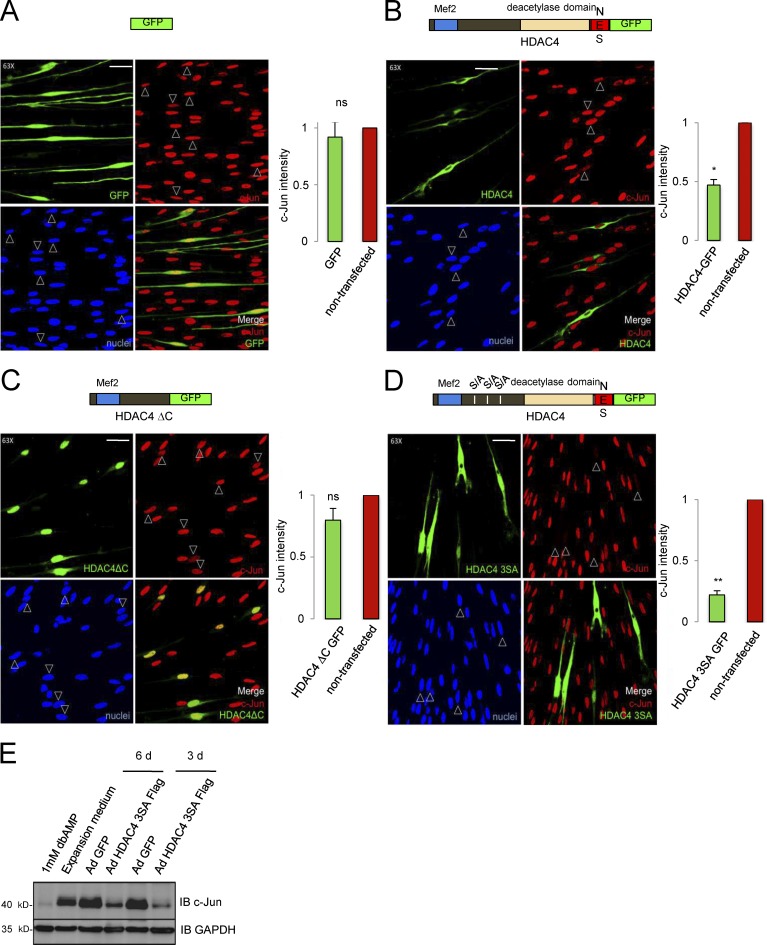

We next performed HDAC4 gain-of-function experiments. We transfected Schwann cells with a plasmid encoding the HDAC4-GFP fusion protein. 24 h after transfection, cells were incubated in SATO medium for an additional 24 h and fixed for immunolabeling. c-Jun expression was quantified as the immunofluorescence intensity in transfected cells (GFP+) and expressed as a ratio of c-Jun expression in neighboring nontransfected cells (GFP−) on the same coverslip. GFP expression by itself produced no significant changes in c-Jun levels, validating our approach (ratio = 0.90 ± 0.13; Fig. 4 A). In contrast, HDAC4-GFP down-regulated c-Jun expression to 0.47 ± 0.05 (Fig. 4 B). However, c-Jun was still clearly detected in the nuclei in many of these cells. Because the fusion protein was mainly located in the cytoplasm, we reasoned that there might not be enough HDAC4 protein in the nucleus to achieve complete down-regulation of c-Jun. It has been shown that the N-terminal domain of HDAC4 is necessary and sufficient to bind and repress Mef2-dependent transcriptional activity (Arnold et al., 2007), whereas the nuclear exportation signal of HDAC4 is located in the C-terminal end of the protein. Thus we deleted the C-terminal domain to generate the fusion protein HDAC4 ΔC GFP, which was highly expressed and accumulated as expected in the nucleus (Fig. 4 C). Unexpectedly, c-Jun was expressed at similar levels as in the nontransfected or GFP-transfected Schwann cells (0.88 ± 0.09), suggesting that partial down-regulation by HDAC4-GFP (Fig. 4 B) is not mediated by the N-terminal domain, and is therefore Mef2-independent. Therefore, we decided to increase the amount of the full-length protein in the nucleus. We transfected Schwann cells with HDAC4 3SA GFP, a construct with three serine residues (Ser246, Ser467, and Ser632) mutated to a nonphosphorylatable alanine, that cannot be retained efficiently in the cytoplasm (Parra, 2015). Interestingly, the construct dramatically down-regulated c-Jun (0.22 ± 0.03) and changed the cell morphology (Fig. 4 D), which looked flatter and lost the typical bipolar shape of cultured Schwann cells. To confirm these results, we infected Schwann cells with adenovirus expressing the HDAC4 3SA tagged with a Flag epitope at the C-terminal domain (Ad HDAC4 3SA Flag) and explored c-Jun expression by Western blot. Adenoviral GFP was used as control. As shown in Fig. 4 E, Ad HDAC4 3SA Flag produced notable down-regulation of c-Jun in the Western blot. Together our data show that when the full-length HDAC4 is forced to shuttle into the nucleus, Schwann cells down-regulate c-Jun and change morphology.

Figure 4.

Gain of HDAC4 function down-regulates c-Jun. (A) Control experiment: the enforced expression of GFP in Schwann cells produced no significant changes in the endogenous c-Jun expression. (B) c-Jun is partially down-regulated in HDAC4-GFP–transfected Schwann cells. (C) HDAC4 ΔC-GFP, which retains the Mef2-binding domain, produced no changes in c-Jun expression. (D) In contrast, the construct HDAC4 3SA GFP dramatically down-regulated c-Jun expression and induced morphological changes in the cells. Cultured rat Schwann cells were transfected and submitted to immunofluorescence with anti–c-Jun antibody. Transfected cells were identified by GFP expression (arrowheads). The graph shows the ratio of c-Jun fluorescence intensity in transfected relative to nontransfected cells on the same coverslip obtained from 300 cells per condition in three different experiments. Data are given as mean ± SE and analyzed with the t test (two-sided). *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001. (E) Cultured rat Schwann cells were infected with Ad HDAC4 3SA Flag or Ad GFP and harvested 3 or 6 d later after 24 h of incubation in SATO medium. Protein extracts were immunoblotted with anti–c-Jun. Extracts from noninfected Schwann cells grown in expansion medium or treated during 24 h with 1 mM dbcAMP were also included. GAPDH was used as a loading control. Bars, 25 µm. Mef2, Mef2 binding site; S/A, serine residues mutated to alanine; NES, nuclear exportation signal.

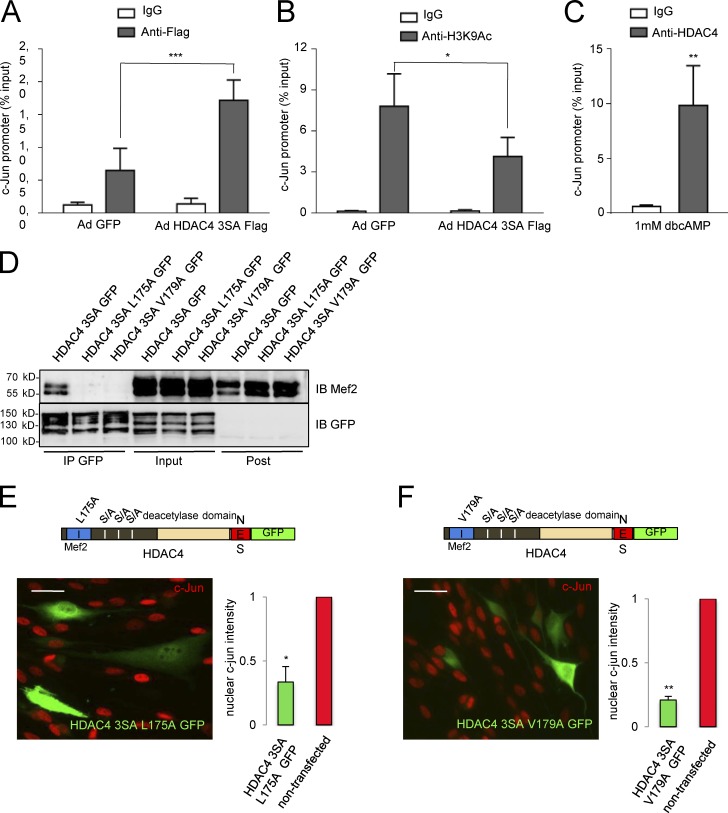

To find out whether HDAC4 3SA Flag blocks c-Jun expression by interacting directly with c-Jun promoter, we performed chromatin immunoprecipitation assays (ChIPs) coupled to qPCR, with an anti-Flag antibody in Ad HDAC4 3SA Flag and Ad GFP–infected Schwann cells. As shown in Fig. 5 A, the c-Jun promoter was pulled down more efficiently from HDAC4 3SA Flag (1.72 ± 0.31% of the input) than from GFP expressing Schwann cells (0.65 ± 0.33%), suggesting interaction of HDAC4 with the promoter region of c-Jun. Nonspecific IgG pulled down less promoter in both cases (0.30 ± 0.12 and 0.27 ± 0.10, respectively). We then determined the amount of acetylated lysine 9 in histone 3 (a marker of active promoters) on c-Jun promoter by ChIP assay. As shown in Fig. 5 B, anti-H3K9Ac pulled down more c-Jun promoter from Ad GFP than from Ad HDAC4 3SA Flag–infected Schwann cells.

Figure 5.

HDAC4 binds to the promoter region of c-Jun in a Mef2–independent way and deacetylates lysine 9 of histone 3. (A) Schwann cells infected with Ad HDAC4 3SA Flag or Ad GFP were cross-linked with PFA. Chromatin was purified and immunoprecipitated with anti-Flag monoclonal antibody or a nonspecific mouse IgG (ChIP grade). qPCR was performed with specific primers for the promoter region of c-Jun. As shown, the recovery of the c-Jun promoter region in the immunoprecipitate was clearly enhanced in HDAC4 3SA Flag–expressing Schwann cells. Nonsignificant recovery was obtained with the nonspecific IgG. Data from five different experiments are given as mean ± SE and analyzed with the paired t test (two-sided). (B) In a parallel series of experiments, chromatin was immunprecipitated with anti-H3K9Ac. Less c-Jun promoter was recovered from the HDAC4 3SA Flag–infected cells than from control cells, suggesting that HDAC4 promotes the deacetylation of lysine 9 from histone 3 in the c-Jun promoter. Data from five different experiments are given as mean ± SE and analyzed with the paired t test (two-sided). (C) To confirm these observations, cultured rat Schwann cells were treated with 1 mM dbcAMP for 24 h and cross-linked with PFA. Chromatin was purified and immunoprecipitated with anti-HDAC4 monoclonal antibody or a nonspecific mouse IgG (ChIP grade). As shown, c-Jun promoter was recovered with the anti-HDAC4 but not with the nonspecific mouse IgG. Data from five different experiments are given as mean ± SE and analyzed with the Mann-Whitney U test. (D) Mutating L175A or V179A in the HDAC4 3SA GFP construct blocks interaction with Mef2. We introduced mutations L174A or V179A in the HDAC4 3SA GFP construct and transfected the resultant constructs into the Schwannoma cell line RT4D6. Cell extracts were pulled down with a GFP-trap (Chromotek) and immunoblotted with anti-Mef2. Whereas Mef2 was efficiently pulled down by HDAC4 3SA GFP, it was not found in the HDAC4 3SA L175A GFP or HDAC4 3SA V179A GFP immunoprecipitates. Expression and immunoprecitation of the transfected constructs were checked by immunoblotting with anti-GFP antibodies. (E) HDAC4 3SA GFP L175A mutant was still able to down-regulate c-Jun, suggesting that interaction with Mef2 is dispensable. (F) The same result was obtained with the HDAC4 3SA GFP V179A. The graph shows the ratio of c-Jun fluorescence intensity in transfected relative to nontransfected cultured rat Schwann cells of the same coverslip obtained from 300 cells per condition in three different experiments. Data are given as mean ± SE and analyzed with the t test (two-sided). *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001. Bars, 25 µm.

To confirm these results, we explored whether endogenous HDAC4 also binds to the c-Jun promoter. Schwann cells were treated with dbcAMP, cross-linked, and immunopercipitated with anti-HDAC4, and the amount of recovered c-Jun promoter was determined. As shown in Fig. 5 C, anti-HDAC4 antibody pulled down 9.85 ± 3.63% of the input, whereas nonspecific IgG pulled down only 0.60 ± 0.14%. Together our data show that once in the nucleus, HDAC4 binds to and deacetylates histone 3 on the c-Jun promoter to block the expression of this gene in Schwann cells.

Class IIa HDACs do not bind directly DNA but are directed to promoter regions by interaction with transcription factors. Although our data clearly show that the C-terminal domain of the protein enables HDAC4 to down-regulate c-Jun, it is still possible that the interaction of HDAC4 with Mef2 might be necessary to locate HDAC4 in the promoter region of c-Jun. To answer this question, we mutated the N-terminal domain of HDAC4 to impair its interaction with the Mef2-DNA complex in the c-Jun promoter (Han et al., 2005). We generated two distinct constructs, HDAC4 3SA L175A GFP and HDAC4 3SA V179A GFP. To check whether these point mutations indeed block interaction of HDAC4 and Mef2, we transfected the Schwannoma cells with these constructs and looked for Mef2 in the anti-GFP immunoprecipitates. As shown in Fig. 5 D, whereas HDAC4 3SA GFP efficiently pulled down Mef2, these mutants failed to do so. Then we evaluated their capacity to down-regulate c-Jun in cultured rat Schwann cells. As shown in Fig. 5 (E and F), both mutants efficiently down-regulated c-Jun (ratio = 0.30 ± 0.03 and 0.24 ± 0.04, respectively), suggesting that the binding of HDAC4 to Mef2 in the promoter is not needed to block c-Jun expression in Schwann cells. In summary, our data show that in Schwann cells, activated HDAC4 binds to the promoter and blocks c-Jun expression by a Mef2-independent mechanism.

HDAC4 recruits the deacetylase activity of other HDACs to down-regulate c-Jun

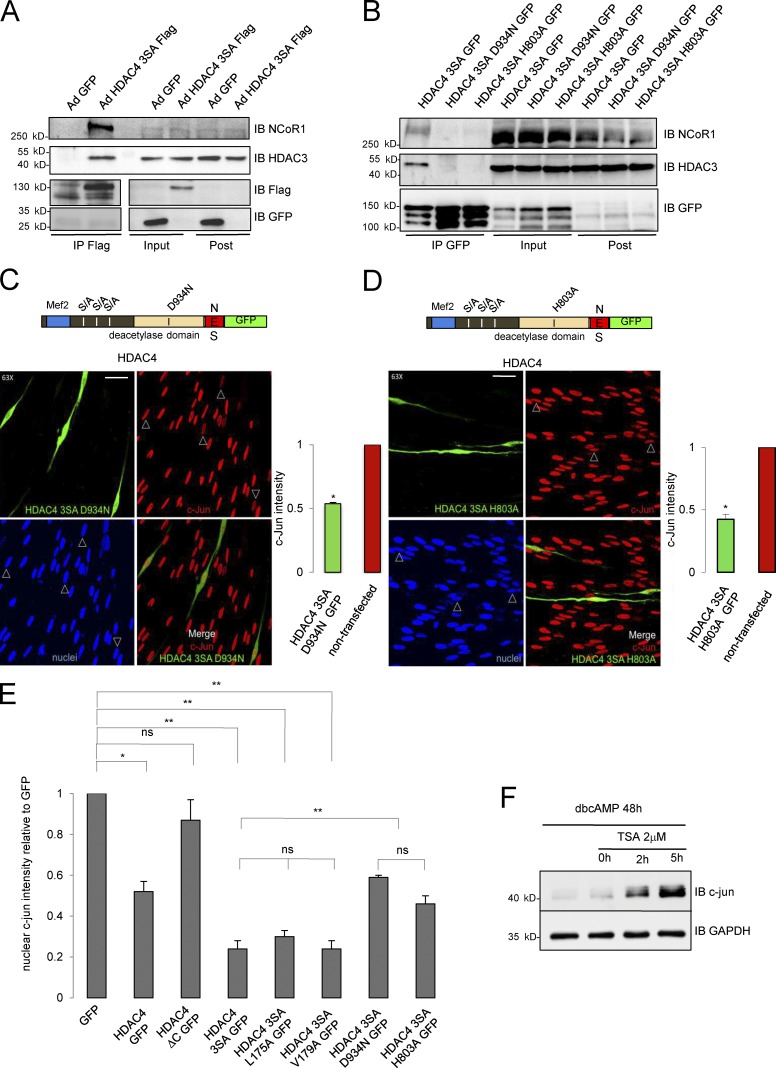

Our data suggest that the capacity of HDAC4 to down-regulate c-Jun in Schwann cells resides in the C-terminal, where the dead deacetylase domain is located (Lahm et al., 2007). Although there is no transcription factor–binding site described in this domain, it has been elegantly demonstrated that it recruits HDAC3 by forming a multiprotein complex with the N-CoR1/SMRT corepressor, and it is possible to introduce point mutations to abrogate the interaction of this domain with NCoR1 and prevent recruitment of HDAC3 (Fischle et al., 2002). To test whether this mechanism could be working in Schwann cells, we first checked whether HDAC4 interacts with NCoR1 and HDAC3 in these cells. NCoR1 and HDAC3 were efficiently pulled down by the anti-Flag antibody from Ad HDAC4 3SA Flag but not from Ad GFP (Fig. 6 A) or Ad CMV Flag (Fig. S3 B)–infected Schwann cells. To see whether the interaction is required to block c-Jun expression in Schwann cells, aspartate 934 was mutated to an asparagine in the HDAC4 3SA GFP fusion protein. We also generated a second construct by mutating histidine 803 to alanine (Fischle et al., 2002). To check if these mutants have lost the capacity to interact with the NCoR1/HDAC3 complex, we transfected HDAC4 3SA D934N GFP and the HDAC4 3SA H803A GFP into the Schwannoma cell line RT4D6 and looked for NCoR1 and HDAC3 in the immunoprecipitates of these fusion proteins. As is shown in Fig. 6 B, both mutations were sufficient to block the interaction with the complex. The constructs were then transfected into cultured rat Schwann cells. As shown in Fig. 6 C, the efficiency of the construct HDAC4 3SA D934N GFP to block c-Jun expression was notably (but not totally) hampered when compared with the nonmutated HDAC4 3SA GFP protein (Fig. 6, C and E). A similar result was obtained for HDAC4 3SA H803A GFP (Fig. 6, D and E). Together, our results suggest that HDAC4 down-regulates c-Jun by recruiting the deacetylase activity of HDAC3 to the promoter of this gene through the interaction with the NCoR1 complex. To determine if this model is correct, we treated Schwann cells with dbcAMP to down-regulate c-Jun, and then inhibited HDAC activity with 2 µM trichostatin A (TSA), a pan-HDAC inhibitor relatively inefficient for class IIa HDACs (in vitro Ki for HDAC4 = 3.36 µM vs. <0.004 µM for class I HDACs such as HDAC1, 2 and 3; and <0.001 for the class IIb HDAC6 and HDAC10; Lobera et al., 2013). 2 h after TSA incubation, c-Jun was clearly up-regulated (Fig. 6 F). Up-regulation was even higher after 5 h of treatment, suggesting that the repressive effects of cAMP on c-Jun expression depend on the enzymatic activity of a fully active HDAC. In summary, our data suggest that once in the Schwann cell nucleus and close to the promoter, HDAC4 recruits a bona fide HDAC (probably HDAC3) to locally deacetylate histones and block c-Jun expression.

Figure 6.

HDAC4 recruits the deacetylase activity from other HDACs through interaction with NcoR1 to down-regulate c-Jun. (A) HDAC4 interacts with the NCoR1/HDAC3 complex in Schwann cells. Schwann cells were infected with Ad HDAC4 3SA Flag or Ad GFP, lysed, and extracts pulled down with anti-Flag agarose beads. Immunoprecipitates, inputs, and postimmunoprecipitates were immunobloted with anti-NCoR1 or anti-HDAC3. NCoR1 and HDAC3 were recovered exclusively from Ad HDAC43SA Flag–infected cells. Expression and immunoprecitation of the introduced proteins was checked by immunoblotting with anti-Flag and anti-GFP antibodies. (B) We introduced mutations D934N or H803A in the HDAC4 3SA GFP construct and transfected the resultant construct into the Schwannoma cell line RT4D6. Cell extracts were pulled down with GFP-trap (Chromotek) and immunoblotted with anti-NCoR1 and anti-HDAC3 antibodies. Whereas NCoR1 and HDAC3 were efficiently pulled down by HDAC4 3SA GFP, none of these proteins were found in the HDAC4 3SA D934N GFP or HDAC4 3SA H803A GFP immunoprecipitates. Expression and immunoprecitation of the transfected constructs were checked by immunoblotting with anti-GFP antibodies. (C) Blocking the interaction of HDAC4 3SA with the multiprotein complex NcoR1/HDAC3 by the mutation D934N interferes with its capacity to down-regulate c-Jun. Cultured Schwann cells were transfected with this mutant and submitted to immunofluorescence with the c-Jun antibody. Transfected cells were identified by GFP expression (arrowheads). The graph shows the ratio of c-Jun fluorescence intensity in transfected relative to nontransfected cells of the same coverslip obtained from 300 cells per condition in three different experiments. Data are given as mean ± SE and analyzed with the t test (two-sided). *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001. (D) A similar result was obtained with the HDAC4 3SA H803A GFP protein. Bars, 25 μm. (E) Summary statistical analysis of the effects of the different mutations introduced in HDAC4 on c-Jun expression levels normalized for GFP transfected Schwann cells. Data are given as mean ± SE and analyzed with the t test (two-sided). *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001. (F) c-Jun down-regulation by cAMP depends on a protein with deacetylase activity. Cultured rat Schwann cells were incubated with 1 mM dbcAMP for 48 h to down-regulate c-Jun. Then, and still in the presence of dbcAMP, a pan-HDAC inhibitor was added (2 µM TSA). Cells were harvested at different time points and immunoblotted for c-Jun. GAPDH was used as a loading control. As shown, inhibition of deacetylase activity reverts the down-regulation of c-Jun by dbcAMP.

Nuclear shuttling of HDAC4 starts the myelin gene program of Schwann cells

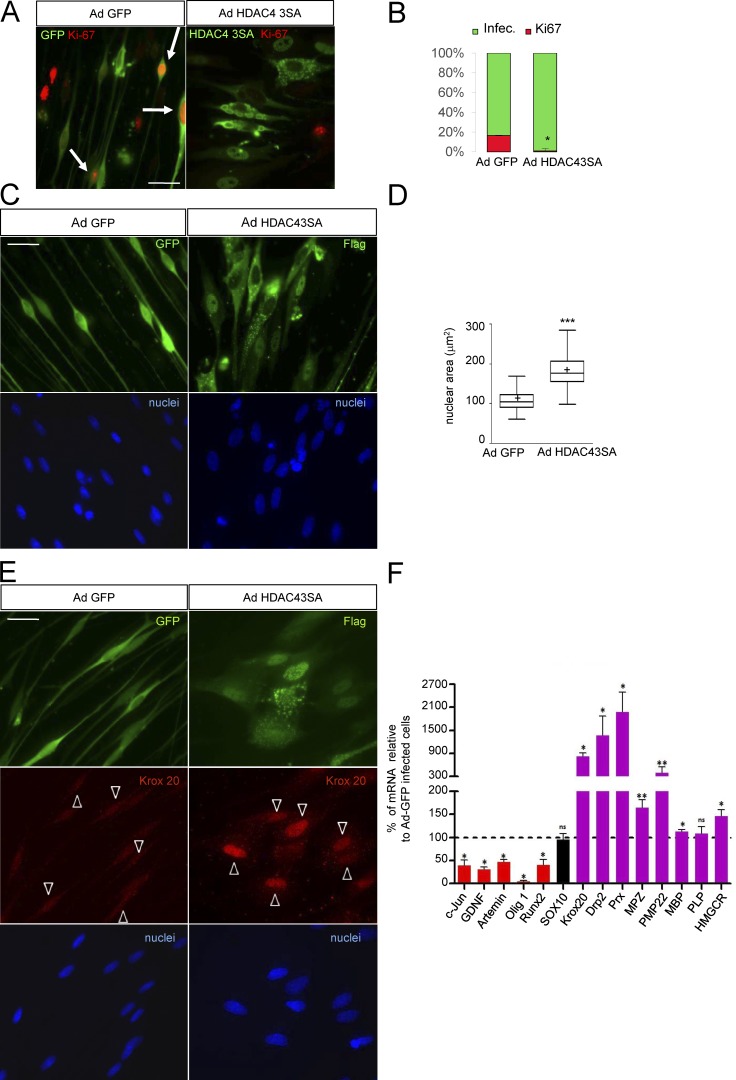

To learn whether the nuclear shuttling of HDAC4 simply blocks c-Jun expression or, in contrast, has a wider effect on the phenotype of Schwann cells, we evaluated the cell cycle in Ad HDAC4 3SA Flag–infected cells by using Ki-67 immunolabeling (Fig. 7 A). Virtually no Ad HDAC4 3SA Flag–infected Schwann cells expressed Ki-67 (0.8 ± 0.2%), whereas a considerable fraction of Ad GFP-infected cells did so (16.6 ± 2.5%), suggesting that HDAC4 takes Schwann cells out of cell cycle (Fig. 7 B). As mentioned above we also noticed that HDAC4 3SA expression produces a strong effect on Schwann cell morphology. Whereas cultured rat Schwann cells adopt the typical bipolar morphology, those cells expressing HDAC4 3SA assumed a flatter morphology, lost their bipolar shape, and showed an enlarged nucleus reminiscent of the changes observed in cAMP–differentiated Schwann cells (Monje et al., 2009; Fig. 7 C). To substantiate these changes, we quantified the nuclear area of Ad HDAC4 3SA Flag–infected Schwann cells and compared it with the control Ad GFP–infected ones. As is shown, the nuclear area increased from 112.4 ± 17 µm2 in control cells to 187.0 ± 2.0 µm2 in the Ad HDAC4 3SA Flag–infected Schwann cells, confirming the observed morphological change (Fig. 7 D).

Figure 7.

HDAC4 gain of function induces Schwann cell differentiation. (A) HDAC4 3SA blocks Schwann cell proliferation. Schwann cells were infected with Ad HDAC4 3SA Flag or Ad GFP and incubated in SATO medium. 24 h later, cells were fixed and examined by immunofluorescence with ant-Ki67 antibodies. Infected cells were identified with anti-GFP or anti-flag antibodies. Arrows indicate Ki67-postive infected cells. (B) Quantification of more than 600 cells from three different experiments is shown. Data are given as mean ± SE and analyzed with the unpaired t test (two-sided). *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001. (C) HDAC4 3SA induces profound morphological changes. Ad GFP–infected Schwann cells show the typical bipolar shape, which changes to an expanded flat epithelial-like morphology with enlarged nucleus in the Ad HDAC4 3SA Flag–infected cells. (D) To substantiate these changes, nuclear area was quantified in 668 cells per condition from three different experiments. A Tukey’s box plot of the results is shown. Data were analyzed with the unpaired t test (two-sided). *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001. (E) HDAC4 3SA induces Krox20 expression. Schwann cells were infected with Ad HDAC4 3SA or Ad GFP and incubated in SATO medium. 24 h later, cells were fixed and examined by immunofluorescence with anti-Krox20 antibody. As is shown, only HDAC4 3SA–infected cells expressed Krox20. Arrowheads indicate infected cells. (F) Quantification of mRNA levels expressed typically by nonmyelin-forming (red) and by myelin-forming Schwann cells (magenta) in Ad HDAC4 3SA Flag–infected cells normalized for controls (Ad GFP–infected Schwann cells). Sox10, a gene that is expressed by both, is in black. As shown, HDAC4 3SA induces a clear shift toward the myelin gene expression program. As expected, no changes were observed for Sox10. Data are given as mean ± SE and analyzed with the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001. Bars, 25 µm.

c-Jun prevents Schwann cell differentiation in vitro by blocking the expression of Krox20, a master gene that controls the myelin transcriptional program (Parkinson et al., 2008). To learn if HDAC4 nuclear shuttling and c-Jun down-regulation are enough to start the Schwann cell myelin gene expression program, we examined the expression of Krox20 by immunofluorescence. As is shown in Fig. 7 E, Ad HDAC4 3SA Flag robustly induced Krox20 expression, whereas no expression could be detected in Ad GFP–infected cells. Periaxin (an early marker of Schwann cell differentiation) was also induced by HDAC4 3SA Flag (Fig. S4, A and B).

To have a more complete insight into the phenotypic changes induced by HDAC4 3SA, we measured the mRNA of several negative and positive regulators of myelination. First, we confirmed the down-regulation of c-Jun mRNA (38 ± 12% of the control in the Ad HDAC4 3SA Flag–infected cells; Fig. 7 F). It has been shown that Gdnf and Artemin, two pivotal PNS injury–induced genes, are direct c-Jun targets (Fontana et al., 2012). Interestingly, we found that nuclear HDAC4 3SA Flag efficiently blocked the mRNA expression of Gdnf (31 ± 6%) and Artemin (47 ± 5%). In vivo expression of Olig1 is also controlled by c-Jun (Arthur-Farraj et al., 2012). We found that Olig1 is highly expressed by cultured rat Schwann cells and, interestingly, dramatically down-regulated by HDAC4 3SA Flag (5 ± 1%). It was recently suggested that Runx2 is another injury-induced gene controlled by c-Jun (Hung et al., 2015). Importantly, Runx2 is also a well-known direct target for HDAC4 in chondrocytes. We observed that cultured Schwann cells abundantly express Runx2 mRNA, which is blocked by expression of HDAC4 3SA Flag (40 ± 12%; Fig. 7 D). Thus, our data show that the nuclear shuttling of HDAC4 down-regulates several c-Jun targets in Schwann cells. Next we looked at positive regulators of myelination and myelin protein genes. First we confirmed Krox20 mRNA induction by HDAC4 3SA Flag (815 ± 102% of the control). We also found a dramatic increase in the mRNA for both Drp2 and Periaxin, two early markers of myelination (1,371 ± 497% and 1,977 ± 515%, respectively). We could detect notably increased levels of Mpz and Pmp22 mRNAs (165 ± 17% and 396 ± 151%) in both myelin structural proteins. Importantly, we also found a clear increase in the expression of the rate-limiting enzyme for cholesterol biosynthesis, HMG-CoA reductase (147 ± 14%), a pivotal gene for myelin sheath (MS) development. However, we observed only minor changes in Mbp (112 ± 4%) and no changes in Plp mRNA (108 ± 16%; see Discussion). As expected, no differences were found in the expression of Sox10 (95 ± 13%; Fig. 7 F). Together our data show that the nuclear shuttling of HDAC4 is sufficient to induce the expression of Krox20 and start the myelin transcriptional program in Schwann cells.

HDAC4 and HDAC5 contribute to Schwann cell differentiation and myelin development in vivo

We then explored the role of HDAC4 in the differentiation of Schwann cells and myelin development in vivo. Because HDAC4(−/−) mice are not viable (Vega et al., 2004), we generated Schwann cell conditional KOs (P0-Cre+/−; HDAC4flx/flx; Fig. S5, A and B) and determined mRNA levels for several negative and positive regulators of myelination in the sciatic nerves of these mice (Fig. S5 C). At postnatal day 0 (P0), P0-Cre+/−; HDAC4flx/flx mice showed a tendency (non–statistically significant) to express more c-Jun, and a slight (but statistically significant) decrease in some myelin genes (Periaxin, Mpz, and Hmgcr). At P2, conditional KO mice expressed twice the level of c-Jun mRNA (207 ± 11%) as the P0-Cre−/−; HDAC4flx/flx littermates. Changes in Runx2 were not statistically significant. On the other hand, although we found a significant decrease in the expression of Hmgcr (68 ± 10%), other myelination markers were not changed (101 ± 7% for Prx and 104 ± 10% for Mpz). In addition, a slight but statistically significant increase in Krox 20 mRNA was found (121 ± 6%). At later stages (P5), c-Jun mRNA was still high (140 ± 7%) and Runx2 expression was increased (223 ± 11%), but no decrease in the expression of myelin genes could be detected (113 ± 5% for Krox20, 107 ± 3% for Periaxin, 119 ± 2% for Mpz, and 113 ± 7% for Hmgcr; Fig. S5 C).

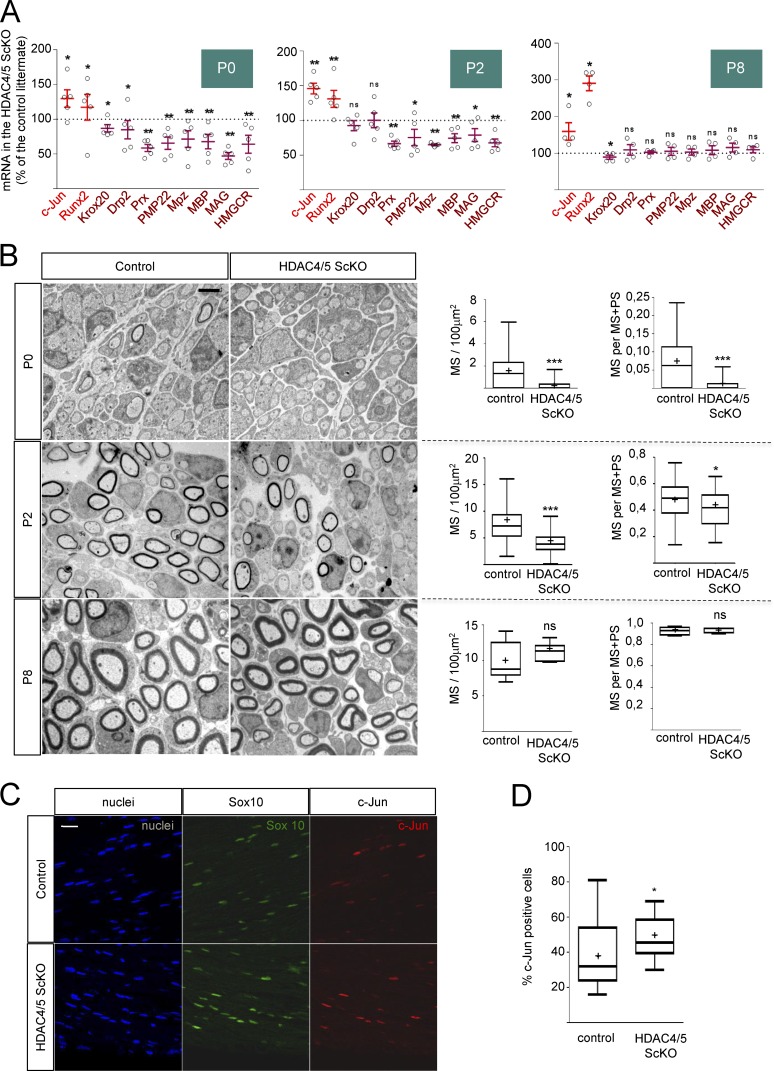

Although encoded by different genes, all class IIa HDACs share molecular profiles and regulate equivalent genetic programs in other tissues (Parra and Verdin, 2010; Parra, 2015). Thus, it has been shown that distinct class IIa HDACs redundantly regulate slow oxidative muscular fiber gene expression. In fact, it is necessary to remove at least four alleles of some of the skeletal muscle expressed class IIa HDACs (4, 5, 7, and 9) to observe a change in the muscle fiber phenotype (Potthoff et al., 2007). To learn whether other class IIa HDACs could compensate for the loss of HDAC4, we generated HDAC4;HDAC5 Schwann cell double KOs. Because HDAC5(−/−) is viable and has no obvious myelination phenotype, we first explored the myelin gene expression profile in the sciatic nerves of these mice. As shown in Fig. S5 D, no changes in c-Jun or Runx2 expression were found. Expression of myelin genes was not decreased (and even slightly increased in some cases). We then generated P0-Cre+/−; HDAC4flx/flx; HDAC5−/− mice, which lack four class IIa HDAC alleles (hereafter called HDAC4/5 ScKO) and evaluated myelin gene expression in these nerves. The results were normalized against P0-Cre−/−; HDAC4flx/flx; HDAC5−/− littermates (hereafter called control). As shown in Fig. 8 A, at P0 we found a slight increase in c-Jun mRNA (130 ± 13%) and in Runx2 mRNA (117 ± 19%) in the HDAC4/5 ScKO. Interestingly, the mRNA for the master myelination gene Krox20 was slightly decreased (87 ± 5%). In agreement with this, mRNAs for myelination markers were significantly down-regulated (85 ± 13% for Drp2, 59 ± 5% for Prx, 66 ± 9% for Pmp22, 71 ± 12% for Mpz, 68 ± 10% for Mbp, 47 ± 5% for Mag, and 64 ± 13% for Hmgcr), suggesting a delay in the expression of the myelin gene program in these mice. To substantiate this result, we obtained EM images and quantified MS density. As shown in Fig. 8 B, the number of myelin profiles per nerve area is significantly reduced in the HDAC4/5 ScKO, supporting the notion of a delay in myelination in the double KO mice (1.47 ± 0.16 MS/100 µm2 in the control vs. 0.18 ± 0.04 MS/100 µm2 in the HDAC4/5 ScKO). To find out whether this is caused by a delay in the transition between the promyelinating and the myelinating stages, we counted the number of MSs and expressed it as a ratio of the number of segregated axons (both myelinated and in the promyelinating stage [PS]). As shown, this ratio is decreased in HDAC4/5 ScKO nerves (0.069 ± 0.008 in control vs. 0.008 ± 0.002 in HDAC4/5 ScKO), suggesting a delay in the transition from the promyelinating stage to the myelin-forming stage rather than a radial sorting defect (Fig. 8 B). We then evaluated gene expression at P2. As shown in Fig. 8 A, c-Jun and Runx2 remained elevated (145 ± 8% and 131 ± 12%, respectively). No changes were found in Krox20 and Drp2 (93 ± 7% and 100 ± 11%, respectively), whereas a significantly decreased expression of other myelin genes was observed (67 ± 4% for Prx, 75 ± 12% for Pmp22, 65 ± 1% for Mpz, 75 ± 6% for Mbp, 79 ± 9% for Mag, and 68 ± 6% for Hmgcr). Morphologically, myelination was still delayed (8.83 ± 0.43 MS/100 µm2 and 0.47 ± 0.02 MS/[MS+PS] for control and 3.99 ± 0.26 MS/100 µm2 and 0.41 ± 0.02 MS/[MS+PS] for HDAC4/5 ScKO). When myelination at P8 was evaluated, we found that although c-Jun and Runx2 remained elevated (159 ± 24% and 290 ± 20%, respectively) and Krox20 was slightly decreased, myelin gene expression was not different from that of control littermates. Moreover, morphological parameters of myelin maturation were similar (9.88 ± 0.77 MS/100 µm2 and 0.93 ± 0.01 MS/[MS+PS] in the controls and 11.39 ± 0.36 MS/100 µm2 and 0.92 ± 0.01 MS/[MS+PS] in the HDAC4/5 ScKO nerves; Fig. 8, A and B). A similar result was found for P15 double KOs (Fig. S6 A). Myelination parameters were also normal in older animals (Fig. S7, B and C), suggesting that other factors (such as other deacetylases) can compensate for the absence of HDAC4 and HDAC5 during MS formation. Interestingly, although c-Jun expression and myelination parameters are normal in the adult HDAC4/5 ScKO, we observed that after nerve injury, c-Jun is reexpressed more efficiently in these mice (Fig. 8, C and D; and Fig. S7), suggesting that HDAC4 and HDAC5 contribute to slow down the up-regulation of c-Jun after injury. Together our data suggest that HDAC4 and HDAC5 contribute to the establishment of the myelin transcriptional program and differentiation of Schwann cells in vivo.

Figure 8.

HDAC4 and HDAC5 redundantly contribute to Schwann cell differentiation and myelin development in vivo. (A) Removal of HDAC4 and HDAC5 in Schwann cells delays myelin gene expression. mRNA quantification for markers of nonmyelin- and myelin-forming cells in the PNS. P0 sciatic nerves were removed and total RNA extracted. RT-qPCR with mouse-specific primers for the indicated genes was performed and normalized to 18S rRNA. Graph shows the percentage of mRNA for each gene in the HDAC4/5 ScKO (P0-Cre(+/−); HDAC4(flx/flx); HDAC5(−/−)) normalized for the control (P0-Cre(−/−); HDAC4(flx/flx); HDAC5(−/−)) littermates. At least four mice from four different litters were used per genotype. Data were analyzed with the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. A scatter plot is shown with the results obtained in each different experiment, which include also the mean ± SE. (B) Retardation in myelin gene expression is reflected in a delay in myelin development. Transmission EM of P0, P2, and P8 sciatic nerves. Tukey’s box plots show the quantification of MS density (MS/100 µm2) and the myelination index (ratio of the number of myelin profiles [MS] to the total number of 1:1 segregated axons [MS+PS]). As is shown, whereas both parameters are decreased in the HDAC4/5 ScKO at P0 and P2, no differences could be found at P8. For P0, 80 images from four different mice per genotype were quantified; for P2, 78 images from six mice; for P8, 11 images from two different mice per genotype. Data were analyzed with the Mann-Whitney U test. Mean is plotted as a “+.” *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001. Bar, 2 µm. (C) c-Jun is up-regulated faster after nerve injury in the HDAC4/5 ScKO. The sciatic nerves of three HDAC4/5 ScKO and three control mice were injured and analyzed 16 h later. Transverse cryosections were incubated with the indicated primary antibodies. Imaging was performed on a confocal microscope. Schwann cells were identified as Sox10-positive cells. (D) A Tukey’s box plot of the percentage of c-Jun–positive cells. Six images per animal were counted using Image J software. Data were analyzed with the Mann-Whitney U test. Mean is plotted as a “+.” *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001. Bar, 25 µm.

Discussion

During postnatal development, Schwann cells activate the myelin gene expression program to synthesize the lipids and proteins necessary for the development of the MS. Recently it has been elegantly shown that Gpr126 controls this phenotypic transition in vivo (Monk et al., 2009, 2011; Mogha et al., 2013; Paavola et al., 2014; Petersen et al., 2015). Gpr126 activation stimulates adenylate cyclase activity and increases the intracellular cAMP concentration, which is necessary for induction of Schwann cell differentiation and myelin membrane development (Monk et al., 2009). Although it has been proposed that rising cAMP in Schwann cells activates both PKA and the exchange protein directly activated by cAMP (Bacallao and Monje, 2013), the precise downstream mechanisms that connect it to the activation of the myelin gene expression program remain largely undefined. Schwann cell myelination is controlled by the tuning of positive regulators such as Krox20, Oct-6, Sox10, and YY1, and negative regulators such as c-Jun, Sox2, Ednrb, Id1, and Notch (Brennan et al., 2000; Jessen et al., 2015a,b). Although some details are still missing, it is clear that Krox20 expression is necessary and sufficient to induce high levels of myelin gene expression (Parkinson et al., 2004). In addition, several “negative regulators” need to be down-regulated to allow Schwann cells to express Krox20 (Parkinson et al., 2008). Some of these inhibitors (such as c-Jun) are promptly reexpressed after nerve injury, when the myelin gene expression program is down-regulated and Schwann cells transdifferentiate into a repair cell that contributes to nerve regeneration (Jessen et al., 2015b). Although repair cells are quite distinct from immature Schwann cells, they share many genetic and biological properties, and can reenter the myelin gene expression program once the relationship with the axons has been reestablished (Jessen et al., 2015a; Benito et al., 2017).

It has been recently shown that the repressor Zeb2 is essential for Schwann cell differentiation. When Zeb2 is inactivated, the expression of Sox2 and Ednrb (two potent negative regulators of myelination) is dramatically up-regulated, and Schwann cells cannot express Krox20 or myelin genes. Thus, the repression of “negative regulators” by Zeb2 is a necessary step for myelination (Quintes et al., 2016; Wu et al., 2016). Here we add new evidence suggesting that repression of another “negative regulator” of myelination (c-Jun) by class IIa HDACs is also important for myelin development. Our data show that the activation of one of these deacetylases (HDAC4) is sufficient to switch on myelin gene expression. Importantly, the dependence of class IIa HDAC activity on cAMP levels provides a putative link between Gpr126 signaling and the activation of the myelin transcriptional program by Schwann cells. Although the transcriptional repression of the c-Jun promoter can explain many of the effects of HDAC4 in Schwann cells, we found that this protein also binds the promoters of Runx2 and Gdnf (Fig. S8, A and B), suggesting that HDAC4 could contribute to regulate the expression of these genes (and maybe of others repressed in myelinating Schwann cells) through a c-Jun–independent mechanism.

It has been known for a long time that the increase of intracellular cAMP levels potentiates the mitogenic effect of some trophic factors on Schwann cells (Raff et al., 1978; Salzer and Bunge, 1980). Conversely, cAMP analogues used at high concentrations (such as dbcAMP) can also act as cell cycle inhibitors and strong inducers of Schwann cell differentiation (Sobue et al., 1986; Bacallao and Monje, 2013). These apparently contradictory observations have been clarified only recently. Thus, it was shown that forskolin is mitogenic at low concentrations (0.2–5 µM) and becomes a differentiation factor at higher concentrations (10 µM). In parallel, dbcAMP is mitogenic at low concentrations (<100 µM) and prodifferentiating at high concentrations (1 mM; Morgan et al., 1991; Monje et al., 2009; Arthur-Farraj et al., 2011; Bacallao and Monje, 2013). Interestingly, we found that only prodifferentiating concentrations of forskolin and dbcAMP can efficiently shuttle HDAC4 into the nucleus of Schwann cells (Fig. 1 F). These data suggest that only those conditions that elicit cAMP-signaling that is sufficient to translocate class IIa HDACs into the nucleus can repress c-Jun and start the myelin gene program. Our data show that HDAC4 translocation is mediated by the direct phosphorylation of Ser265 and Ser266 by PKA. Nevertheless, other mechanisms are probably also involved as a construct mutant for these two serines can still shuttle into the nucleus in response to cAMP (Fig. 1 G).

We show that HDAC4 binds to the promoter of c-Jun to regulate its expression in Schwann cells (Fig. 5, A–C). Surprisingly, and at variance with VSMC and other cell types (Vega et al., 2004; Gordon et al., 2009), we found that HDAC4 effects on c-Jun are not mediated by Mef2. First, a construct with the N-terminal domain of HDAC4 containing the Mef2 binding site produced no effect on c-Jun expression (Fig. 4 C). Second, the introduction of point mutations that block the interaction with Mef2 in the full-length HDAC4 3SA GFP did not affect its efficacy to down-regulate c-Jun (Figs. 5, D–F). Strikingly, we found that the effects on c-Jun are mediated by the C-terminal domain of HDAC4, and depend on its capacity to interact with NCoR1 and recruit a bona fide HDAC. First, we show that the full-length HDAC4 3SA Flag construct reduced the levels of H3K9Ac associated with the c-Jun promoter (Fig. 5 B). Second, two distinct point mutations in the C-terminal domain that block the interaction of HDAC4 with the NCoR1/HDAC3 complex decreased its efficacy to down-regulate c-Jun (Fig. 6, A–E). Finally, c-Jun down-regulation by cAMP was reversed by incubation with 2 µM TSA, a deacetylase inhibitor that efficiently inhibits class I HDACs (including HDAC3) and class IIb HDACs but not class IIa HDACs (Lobera et al., 2013; Fig. 6 F).

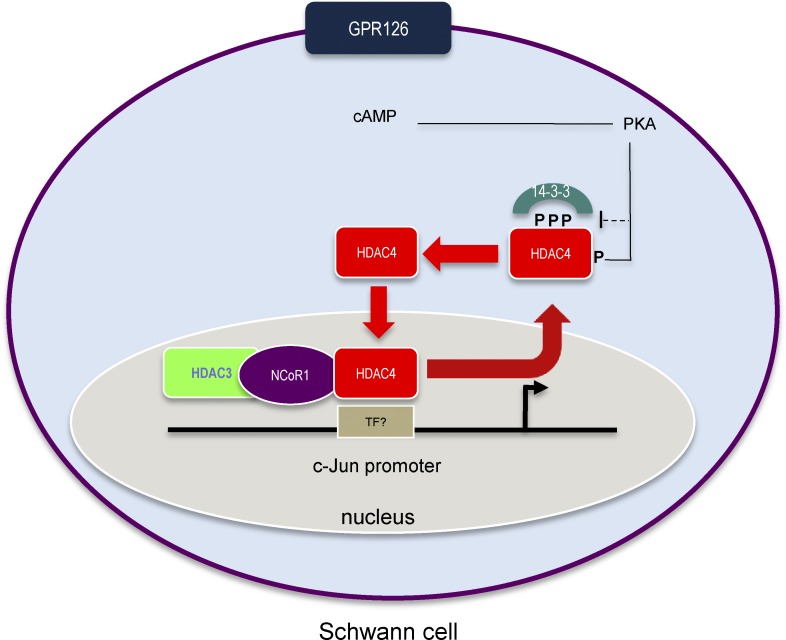

In summary, our data suggest that the activation of PKA by cAMP shuttles HDAC4 into the Schwann cell nucleus, where it binds (probably through an unidentified transcription factor) to the c-Jun promoter and recruits the NCoR1/HDAC3 complex to block the expression of this gene (Fig. 9). However, although HDAC3 is the most probable effector of this complex, we cannot completely rule out a role for other deacetylases (such as HDAC1) that can form complexes with NCoR1 (Cartron et al., 2013). Indeed, as mentioned before, HDAC1 and HDAC2 have been shown to be central for myelin development, and the combined elimination of both genes in vivo blocks completely PNS myelin development (Chen et al., 2011; Jacob et al., 2011a).

Figure 9.

Proposed working model. Gpr126 activation raises intracellular cAMP-activating PKA, which phosphorylates HDAC4 in Ser265/266. This (together with another indirect mechanism) shuttles HDAC4 into the nucleus, where it binds to the promoter of c-Jun (through a not yet identified transcription factor [TF]) recruiting the NCoR1/HDAC3 complex to block gene expression.

We show that HDAC4 3SA also blocks the expression of c-Jun downstream genes such as Runx2, Artemin, Gdnf, and Olig1. Interestingly, the activated form of HDAC4 is enough to strongly induce Krox20 expression, the master gene for myelin development. It also enhances the gene expression of HMGCoA reductase (the rate-limiting enzyme for cholesterol biosynthesis) and of many myelin protein genes such as Drp2, Periaxin, Mpz, and Pmp22 (Fig. 7, E and F). We also found a statistically significant increase in Mbp, but it seems too small to have biological relevance. In contrast, no changes in Plp expression were detected. Thus, although HDAC4 3SA can induce a clear change in the gene expression pattern of Schwann cells toward the myelinating phenotype, some genes are not directly regulated by this deacetylase and probably require the activation of other signaling pathways, the identity of which is being currently explored in our laboratory.

Distinct class IIa HDACs can be expressed in the same cell type or tissue, where they can have redundant roles. As it has been discussed above, at least four alleles of class IIa HDACs must be removed to observe a change in the phenotype of muscle fibers (Potthoff et al., 2007). Here we show that, although the removal of HDAC4 or HDAC5 alone from Schwann cells does not have a strong impact, the elimination of both proteins at the same time produces a delay in the activation of the myelin gene expression program that is reflected in a decrease in the density of MSs (Fig. 8, A and B). Our data also suggest that the decrease in myelin density involves a delay in the transition from the promyelin to the myelin-forming stages (Fig. 8 B). However, this delay is later compensated and myelination appears normal in older mice (Fig. S6, A–C). A similar phenomenon occurs for other positive regulators of myelination such as Oct-6 (Jaegle et al., 1996). We do not yet know the identity of the compensatory mechanisms, but it is worth mentioning that Schwann cells express other class IIa HDACs such as HDAC7. Therefore, the possibility exists that they could compensate for the absence of HDAC4 and HDAC5, allowing myelination to proceed and become normalized at later stages. Interestingly, and although c-Jun expression is normally repressed in the adult HDAC4/5 ScKO, we observed that it is reexpressed more efficiently after nerve injury (Fig. 8, C and D; and Fig. S7). In summary, we propose a model in which class IIa HDACs are pivotal components of an intracellular cAMP sensor mechanism that blocks c-Jun, allowing the activation of the myelin gene expression program and differentiation of Schwann cells.

Materials and methods

Plasmids

pEGFP-N1 was obtained from Clontech Laboratories. phHDAC4-GFP was provided by C. Brancolini, University of Udine, Udine, Italy (Paroni et al., 2004). phHDAC4ΔC-GFP was generated from phHDAC4-GFP by digestion with XcmI restriction enzyme, polishing with T4 DNA polymerase and ligation with T4 DNA ligase. Competent Escherichia coli were transformed with the generated plasmid. The correct sequence of the construct was confirmed by sequencing. phHDAC4-GFP 3SA was provided by C. Brancolini (Paroni et al., 2007, 2008). phHDAC4-GFP 3SA D934N, phHDAC4-GFP 3SA H803A, phHDAC4-GFP 3SA L175A, and phHDAC4-GFP 3SA V179A were generated by site-directed mutagenesis following the protocol described in QuikChange Site-Directed Mutagenesis kit (Stratagene) with the primers listed in Table S2. The correct sequence of the construct was confirmed by sequencing. HDAC4 shRNAi was obtained from Addgene pENTR/U6 HDAC4 shRNA (32220; Addgene). GFP shRNA was obtained from Addgene pENTR/pTER shEGFP (17470; Addgene). Plasmid purification was performed with the NucleoBond Xtra Midi kit (Macherey-Nagel) following the kit instructions.

Animal studies

All animal work was conducted according to European Union guidelines and with protocols approved by the Comité de Bioética y Bioseguridad del Instituto de Neurociencias de Alicante, Universidad Hernández de Elche and Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas (http://in.umh.es/). To avoid suffering, animals were anesthetized before euthanasia. P0-Cre mice were provided by L. Wrabetz (University at Buffalo, Buffalo, NY) and have been previously described in Feltri et al. (1999). HDAC4 floxed mice are described in Lehmann et al. (2018) and Potthoff et al. (2007). The HDAC5 KO mouse was provided by E. Olson (University of Texas Southwestern, Dallas, TX) and described in Chang et al. (2004).

Cell cultures

Schwann cells were cultured from sciatic nerves of neonatal rats as described previously (Brockes et al., 1979) with minor modifications. We used P3-P4 Wistar rat pups. The sciatic nerves were cut out from just below the dorsal root ganglia and at the knee area. During the extraction and cleaning, the nerves were introduced into a 35-mm cell culture dish containing 2 ml of cold Leibovitz’s F-15 medium (Invitrogen) placed on ice. The nerves were cleaned, desheathed, and placed in a new 35-mm cell culture dish containing DMEM with 1 mg/ml of collagenase A (Roche). Subsequently they were cut into very small pieces using a scalpel and left in the incubator for 2 h. Nerve pieces were homogenized using a 1 ml pipette, digestion reaction stopped with complete medium, and the homogenate poured through a 40-µm Falcon Cell Strainer (Thermo Fisher Scientific). We then centrifuged the homogenate at 210 g for 10 min at room temperature and resuspended the pellet in complete medium supplemented with 10 µM of cytosine-β-D-arabinofuranoside (Sigma-Aldrich) to prevent fibroblast growth. The resuspended cells were then introduced into the poly-l-lysine–coated 35-mm cell culture dishes. After 72 h, the medium was removed and cell cultures expanded in DMEM supplemented with 3% FBS, 5 µM forskolin, and 10 ng/ml recombinant NRG1 (R&D Systems). Where indicated, cells were incubated in SATO medium (composed of a 1:1 mixture of DMEM and Ham’s F12 medium [Invitrogen] supplemented with ITS [1:100; Gibco], 0.1 mM putrescine, and 20 nM of progesterone; Bottenstein and Sato, 1979).

RT4D6-P2T rat Schwannoma cells (Hai et al., 2002) were obtained from D. Meijer (Centre for Neuroregeneration, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, Scotland, UK). HEK 293 cells were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich. The cells were grown in noncoated flasks with DMEM GlutaMAX, 4.5 g/l glucose (Invitrogen) supplemented with 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 U/ml streptomycin, and 5% (RT4D6) or 10% (HEK 293) bovine fetal serum. Where indicated, cells were transfected with plasmid DNA using Lipofectamine 2000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific) following the manufacturer’s recommendations.

In vivo translocation of HDAC4

P4 rat pups were anesthetized with isofluorane. The sciatic nerve was exposed and immersed in a solution of 1 mM dbcAMP in saline. A control with only saline was also performed. After 1 h, nerves were removed, fixed, and submitted to immunofluorescence with rabbit polyclonal anti-HDAC4 antibody. Schwann cells were identified by Sox10 expression and nuclei counterstained with Hoechst. Samples were mounted with Fluoromount G. Imaging was performed at room temperature on a confocal microscope (TCS SPE; Leica) controlled with Leica confocal software. A 63× oil-immersion objective lens (HCXPL APO 1.40–060 OIL ∞/0.17/E; Leica) was used for analysis.

Nerve injury experiments

Mice were anesthetised with isofluorane, and the sciatic nerve was exposed and cut at the sciatic notch. The wound was closed using veterinary autoclips. The nerve distal to the cut was excised for analysis after 16 h and fixed with 4% PFA/PBS for 4 h at 4°C, then 15% sucrose/PBS overnight at 4°C, and then embedded in optimal cutting temperature compound. Transverse sciatic nerve cryosections (10 µm) were postfixed with 4% PFA/PBS for 10 min, blocked in 0.2% Triton X-100, 10% horse serum in PBS, and subsequently incubated with primary antibodies in blocking solution overnight at 4°C, followed by 1 h in secondary antibodies and DAPI to identify cell nuclei (1:30,000; Thermo Fisher Scientific). Samples were mounted with Fluoromount G. Imaging was performed at room temperature on a confocal microscope (TCS SPE; Leica) controlled with Leica confocal software. A 40× oil-immersion objective lens (40× HCX PL APO 1.25–0.75 OIL CS; Leica) was used for analysis. All confocal images represent the maximum projection from total stacks from 0–1 mm to the cut point, and six images per animal were counted using ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health).

Nerve explants

Sciatic nerves from adult mice were extracted and cut into 2-mm-long pieces. We then carefully cleaned the pieces and completely removed the epineurum layer. During these steps, the nerves were kept in 35-mm cell culture dishes containing cold Leibovitz’s F-15 medium and placed on ice. The nerve fragments were subsequently transferred to a 24-well plate containing nerve explant medium (DMEM GlutaMAX supplemented with 5% FBS, 100 U/ml penicillin, and 100 U/ml streptomycin.). Three to four nerve fragments were introduced into each well. As an intact nerve control, the same number of nerve fragments was immediately transferred to an Eppendorf and frozen. After 24 h, total RNA was extracted from the nerve explants and intact nerves.

Virus generation and Schwann cell infection

Lv HDAC4 shRNA was generated by Gateway technology, following the protocol described in BLOCK-iT Lentiviral RNAi Expression System (Invitrogen). As an entry vector, pENTR/U6 HDAC4 shRNA (32220; Addgene) was used, and as a destination vector, pLenti-CMV-GFP-DEST (736-1; 19732; Addgene), was used. Lv GFP was generated in the same way as explained above, but as entry construct, we used pENTR/U6 (17387; Addgene), and as destination vector, pLenti CMV GFP DEST (19732; Addgene). To generate Lv HDAC4-GFP, the HDAC4-GFP cDNA was subcloned to generate a pENTR-hHDAC4-GFP construct, which was transferred into the destination vector pLenti CMV Neo DEST (705-1; 17392; Addgene) using Gateway technology. Constructs were verified by sequencing. 15 µg of the resulting construct were cotransfected with the packaging vectors pCMV-VSV-G (3 µg) and pCMVΔ8.9 (20 µg) into HEK293T cells, following the protocol described in Campeau et al. (2009). 48 h after the cotransfection, the HEK293T medium was collected, filtered, and aliquoted. Premade adenovirus Ad-GFP (000541A) and Ad-HDAC4 3SA Flag (000547A) were obtained from Abm and amplified in HEK293 cells as suggested by the manufacturer. Ad CMV Flag was from SignaGen (SL100980). To infect Schwann cells, viral particles were incubated for 24 h and then removed. Infected Schwann cells were cultured in expansion medium for 5 d (Lv) or 3 d (adenovirus). 24 h before the experiment started, cells were incubated in SATO medium.

mRNA detection and quantification by RT-qPCR

To extract total RNA from sciatic nerves and cultured rat Schwann cells, we used the Purelink Micro-To-Midi kit and followed the instructions of the manufacturer (Invitrogen). Genomic DNA was removed by incubation with RNase free DNase I (Fermentas), and RNA was primed with random hexamers and retrotranscribed to cDNA with Super Script II Reverse transcription (Invitrogen). Control reactions were performed omitting retrotranscriptase. qPCR was performed using the Applied Biosystems 7500 Real Time PCR System and 5× PyroTaq EvaGreen qPCR Mix Plus (CMB). To avoid genomic amplification, PCR primers were designed to fall into separate exons flanking a large intron when possible. Reactions were performed in duplicates of three different dilutions, and threshold cycle values were normalized to the housekeeping gene 18S. The specificity of the products was determined by melting curve analysis and gel electrophoresis. The ratio of the relative expression for each gene to 18S was calculated by using the 2ΔCT formula. Amplicons were of similar size (≈100 bp) and melting points (≈85°C). Similar amplification efficiency for each product was confirmed by using duplicates of three dilutions for each sample.

Immunofluorescence and EM studies

For immunofluorescence, cells on coverslips were fixed in 4% PFA/PBS and blocked for 1 h in 10% horse serum and 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS. Primary antibodies were diluted in blocking solution and incubated overnight at 4°C. Coverslips were then washed with PBS, and detection was performed by applying the appropriate fluorescent secondary Alexa Fluor conjugated antibody (Table S1). Nuclei were counterstained with bisbenzimide (Hoechst nuclear stain) in PBS. Samples were mounted in Fluoromount G (Southern Biotechnology Associates). Anti-Krox-20 immunofluorescence was performed as described by Le et al. (2005). Images were obtained at room temperature using a confocal ultraspectral microscope (TCS SP2; Leica) with a 63× Leica objective (HCXPL APO 1.40–060 oil ∞/0.17/E) and using Leica confocal software. Images were analyzed with the ImageJ software and MetaMorph 7.1.2.0 (Molecular Devices). Immunofluorescence images were also obtained using a Nikon Eclipse TE2000-S fluorescence microscope with a Nikon objective 60× (Plan APO 1.40 OIL 60× ∞/0.17 WD 0.13) or a 20× (S Fluor 20×/0.75 ∞/0.17 WD 1.0), and a camera ORCA AG (C4742-80-12-AG; Hamamatsu Photonics) controlled with the MetaMorph software.

For ultrastructural images, mice were anesthetized by intraperitoneal injection of 40 mg/kg ketamine and 30 mg/kg xylazine and then intracardially perfused with 2% PFA, 2.5% glutaraldehyde, and 0.1 M phosphate buffer, pH 7.4. Tissues were dissected and immersed in the same fixative solution at 4°C overnight, washed in phosphate buffer, postfixed in 1% osmium tetroxide, dehydrated in graded ethanol series, and embedded in epoxyresin (Durcupan). Semithin sections were cut with a glass knife at 1–3 mm and stained with toluidine blue to check the quality of the tissue before the EM studies. For EM, ultrathin sections (70–90 nm) were cut on an ultramicrotome (Reichert Ultracut E; Leica) and collected on 200-mesh nickel grids. Staining was performed on drops of 1% aqueous uranyl acetate, followed by Reynolds’s lead citrate. Ultrastructural analyses were performed in a 1010 Jeol electron microscope with Gatan software and analyzed with ImageJ.

Immunoprecipitation

Cells were harvested by centrifugation (210 g, 5 min) and washed with PBS twice. Pellets were lysed in 1 ml of 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 120 mM NaCl, 0.5 mM EDTA 0.5%, Nonidet P-40 with phosphatase, and protease inhibitors and centrifuged 20 min at 12,000 g at 4°C. Supernatants were recovered and precleared. 100 µl of anti-FLAG M1 Agarose Affinity Gel (Sigma-Aldrich) or GFP-Trap agarose beads (Chromotek) were added and samples were incubated overnight at 4°C under gentle rotation. Beads were washed three times with TBS with protease and phosphatase inhibitors, eluted with sample buffer, subjected to SDS-PAGE, and immunobloted with the indicated antibody.

SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting

Cells were homogenized at 4°C in radio-immunoprecipitation assay buffer (PBS, 1% Nonidet P-40, 1% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS, and 5 mM EGTA) containing protease inhibitors (Complete MINI tablets; Roche) and, where necessary, phosphatase inhibitors (Phospho STOP tablets; Roche). Protein concentrations were determined by the BCA method (Pierce). 10–50 µg of total protein was subjected to SDS-PAGE and blotted onto Protran nitrocellulose membrane (Whatman). Membranes were blocked and incubated overnight at 4°C with the indicated primary antibody, washed and incubated with secondary antibodies, and developed with ECLplus (GE Healthcare). The secondary antibodies were conjugated with horseradish peroxidase (1:2,000; Sigma-Aldrich).

ChIPs

The ChIP assay was a modification of the method described by Jang et al. (2006). In brief, cell cultures were incubated in PBS/1% PFA for 25 min at room temperature. Cells were harvested by centrifugation (1,000 g, 3 min) and washed with PBS. The pellet was resuspended in 1.2 ml of buffer A (150 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol, 0.3% Triton X-100, 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8, and protease inhibitors), homogenized, and sonicated (20 pulses of 20 s separated by 40 s on ice between each pulse) to “High Power” in the Bioruptor (Diagenode). Chromatin was clarified by centrifugation at 21,000 g for 30 min at 4°C. Protein concentration in the supernatant was quantified by the BCA method (Pierce). An aliquot was saved as input. The volume corresponding to 60–100 µg of protein was incubated with the corresponding antibody overnight at 4°C to form immunocomplexes. Meanwhile, protein A sepharose (CL-4B; GE Healthcare) was resuspended in distilled water and pelleted by centrifugation (<500 g). The resin was resuspended in water with 0.5 mg/ml of bovine albumin and 0.2 mg/ml of sonicated DNA (herring sperm; Sigma-Aldrich). 40 µl of this slurry was added to the immunocomplex and incubated for 1 h at 4°C. Immune complexes were centrifuged (500 g, 3 min) and washed twice with 1 ml of “low-salt buffer” (0.1% SDS, 1% Triton X-100, 2 mM EDTA, 20 mM Tris, pH 8.1, 150 mM NaCl, and protease inhibitors; Roche), and then washed once with 1 ml of “high-salt buffer” (the same but with 500 mM NaCl) and washed three times with 1 ml of LiCl buffer (0.25 M LiCl, 1% IGEPAL, 1% sodium deoxycholate, 1 mM EDTA, 10 mM Tris, pH 8.1, and protease inhibitors). Chromatin from immunocomplexes and input was eluted with 200 µl of 1% SDS, 0.1 M NaHCO3, and 200 mM NaCl and incubated at 65°C for 6 h (to break the DNA–protein complexes). DNA was purified using a column purification kit (GE Healthcare) and submitted to SYBR green qPCR with the indicated primers.

Statistics

Values are given as means ± standard error (SE). Statistical significance was estimated with the Student’s t test, one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test, the Mann-Whitney U test, and the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. A p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. For the parametric tests (t test and ANOVA), data distribution was assumed to be normal (Gaussian), but this was not formally tested. Analysis was performed using GraphPad software (version 6.0). Statistics for each experiment are described in more detail in the legends to figures. In the Tukey’s box plots, the bottom and top of the box are the first and third quartiles, and the band inside the box is the median. The “+” sign represents the mean. For the bars, the lowest datum is 1.5 interquartile range of the lower quartile, and the highest datum still within 1.5 interquartile range of the upper quartile.

Online supplemental material

A list of the antibodies and dilutions used can be found in Table S1. The sequence of the oligonucleotides used for RT-qPCR, ChIP assays, and genotyping is listed in Table S2. Fig. S1 shows the down-regulation of c-Jun in Schwann cells induced by cAMP and quantified by RT-qPCR. Fig. S2 shows the expression of the different class IIa HDACs in Schwann cells and sciatic nerves. Fig. S3 A shows a loss-of-HDAC4-function experiment in RT4D6 Schwannoma cells. Fig. S3 B is an additional control for Fig. 6 A. Fig. S4 shows the induction of Periaxin expression by Ad HDAC4 3SA in Schwann cells, by immunofluorescence. Fig. S5 (A–C) shows the Cre-induced recombination of the HDAC4flx/flx gene in Schwann cells and its consequences on myelin gene expression. Fig. 5 D shows that myelin gene expression is basically normal in the HDAC5(−/−) mice. Fig. S6 shows myelination of sciatic nerves in the HDAC4/5 ScKOs at different ages. Fig. S7 shows the induction of c-Jun in nerve explants of different class IIa HDAC KOs. Fig. S8 proves that HDAC4 binds to the Runx2 and GDNF promoters.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank C. Morenilla-Palao for advice in ChIP and other molecular biology experiments. We thank Dr. Claudio Brancolini for providing phHDAC4-GFP and phHDAC4 3SA plasmids, L. Wrabetz and L. Feltri for P0-Cre mice, E. Olson for HDAC4 floxed and HDAC5 KO mice, P. Brophy and D. Sherman (University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, Scotland, UK) for Periaxin antibody, and Dies Meijer for RT4D6 cells. We thank R. Mirsky (University College London, London, England, UK) for insightful comments on the manuscript. We also thank P. Morenilla-Ayala for technical assistance.

J. Backs was supported by grants from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (SFB 1118), the European Commission (FP7-Health-2010 and MEDIA-261409), the Deutsches Zentrum für Herz-Kreislauf-Forschung, and the German Ministry of Education and Research. This work has been funded by grants from the Ministerio de Economía y Competitividad (SAF2008-04106, PI012/164, and BFU2016-75864R), Conselleria Educació Generalitat Valenciana (PROMETEO 2008/134), and Fundación para el Fomento de la Investigación Saniatria y Biomédica de la Comunidad Valenciana (UGP-15-211) to H. Cabedo. The Instituto de Neurociencias is a ‘‘Center of Excellence Severo Ochoa” (Ministerio de Economía y Competitividad SEV-2013-0317).

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Author contributions: S. Velasco-Aviles, C. Gomis-Coloma, J.A. Gomez-Sanchez, A. Casillas-Bajo, and H. Cabedo performed the experiments. J. Backs provided mice. S. Velasco-Aviles, C. Gomis-Coloma, J.A. Gomez-Sanchez, and H. Cabedo conceived and designed the experiments. H. Cabedo wrote the paper.

References

- Arnold M.A., Kim Y., Czubryt M.P., Phan D., McAnally J., Qi X., Shelton J.M., Richardson J.A., Bassel-Duby R., and Olson E.N.. 2007. MEF2C transcription factor controls chondrocyte hypertrophy and bone development. Dev. Cell. 12:377–389. 10.1016/j.devcel.2007.02.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arthur-Farraj P., Wanek K., Hantke J., Davis C.M., Jayakar A., Parkinson D.B., Mirsky R., and Jessen K.R.. 2011. Mouse schwann cells need both NRG1 and cyclic AMP to myelinate. Glia. 59:720–733. 10.1002/glia.21144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]