Abstract

Purpose

To discern the efficacy and toxicity of SABR in the elderly population (age ≥75), and to consider how it compares to surgical outcomes historically reported in the elderly.

Methods and Materials

772 patients with clinically early-stage I-II NSCLC (T1-T3 N0M0) were treated with SABR (50 Gy in 4 fractions or 70 Gy in 10 fractions) between 2004-2014 at our center (n=442 age <75, n=330 age ≥75). Primary end points included overall survival, progression-free survival, and grade ≥3 toxicity. Median follow-up time was approximately 55 months.

Results

Compared to patients age <75, patients age ≥75 had no difference in progression free survival (p=0.419), lung cancer-specific survival (p=0.275), or toxicity (p=0.536). Overall survival was the same between both age groups at 2-years of follow-up but diverged thereafter, with patients aged <75 when treatment began having higher overall survival rates at 5 years. Median OS rates for patients age ≥75 were 86% at 1 year, 57.5% at 2 years, and 39.5% at 5 years. No patient ≥75 experienced any grade 4 or 5 toxicity.

Conclusions

SABR’s effectiveness based on lung cancer-specific survival and progression-free survival is the same in the elderly as it is the average age population. It also poses no increased toxicity. Compared to historical outcomes with surgery in the elderly, SABR outcomes here are considered comparable for stage I-II disease but have less morbidity.

Keywords: Surgery, SBRT, Elderly, Lung Cancer, Sublobar

Introduction

The continuing growth of the geriatric population poses a unique challenge to medical, surgical, and radiation thoracic oncologists. Patients age ≥75 years-old with non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) continue to comprise a larger portion of the patients being diagnosed and treated for early stage disease (1). This is due, in part, to the earlier detection of early stage NSCLC with CT screening, but also to the rapid expansion of the 80-and-over population throughout the US (2), (3), (4). Studies confirm that the co-morbidity level of this older population is higher than the average, reflecting the impact of their underlying disease processes such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, emphysema, cardiac disease, and other smoking and non-smoking-related conditions having a greater time period to run their course, and leaving these patients with less reserve (5), (6), (7). This higher co-morbidity rate demands a better understanding of how the treatments available may be different in this unique population, in which morbidity related to therapy is a major concern. Unfortunately, oncologic literature is lacking in studies, including those on lung cancer, that focus on, or include the elderly (age ≥75) (8). The need for such studies is imperative in the field of lung cancer, given that patients who present with NSCLC are already at advanced age.

Today, the primary treatment options for early stage NSCLC include definitive surgery or stereotactic ablative radiotherapy (SABR). Although surgery remains the first-line treatment for most operable patients with NSCLC, it is well recognized that surgical morbidity and mortality are significantly higher in elderly patients (9), (10). Thus, there has been a trend within the surgical community to refer elderly operable patients to less-morbid sublobar or wedge resections (11). While these less extensive resections sacrifice less lung parenchyma and offer reduced surgical-associated morbidity and mortality, these modified techniques also have inferior local control and potentially disease free survival compared to the more extensive and effective standard lobectomy in the average age population (12). Recently, SABR has been suggested to have comparable outcomes to lobectomy in both inoperable and operable patients, and thus may have a role as an acceptable treatment option for certain subsets of operable patients (13), (14), (15), (16), (17). The very low morbidity and mortality with SABR compared to surgery, along with evidence it can provide comparable local control and survival outcomes in certain patients when compared to surgery, may make it particularly well positioned to treat elderly operable patients. In particular, SABR may be well positioned to treat elderly patients who, because of their poorer health, are being referred for sub-lobar surgical techniques that may carry more morbidity compared to non-invasive radiation therapy.

We therefore aimed to review outcomes at our center using SABR as definitive treatment of early stage NSCLC (stage I-II) in elderly patients (age ≥75) from 2004-2014. The end points of overall survival (OS), progression-free survival (PFS), and grade ≥3 toxicity were assessed. The primary goal was to discern the efficacy and toxicity of SABR in elderly patients with lung cancer (age ≥75), and to consider how it compares to historical surgical outcomes reported in this population.

Methods

Patients

From 2004 to 2014, 772 patients with clinical T1-T3 (satellite nodule) N0M0 NSCLC, not involving the bronchial tree or blocking the airway, with or without previous lung cancer history, were treated with image-guided SABR through our institutional SABR program. For most patients with prior lung cancer, the previous lesion was treated with either surgical resection or SABR, and all remained without evidence of previous disease. If previous lung cancer involved radiation therapy, it was required that the current cancer be outside the previously irradiated field, defined as the 20 Gy or higher isodose line. All patients were registered prospectively in this program and their records retrospectively reviewed for this study. This study was approved by the institutional review board. Prior to SABR each patient’s cancer was staged with chest computed tomography, brain magnetic resonance imaging, and/or positron emission tomography (PET)/CT; suspected mediastinal disease was staged by endobronchial ultrasound biopsy.

Radiation therapy protocol

Simulation and planning techniques for SABR have been described previously (18), (19). Four-dimensional CT images were obtained in all cases to allow tumor motion to be taken into consideration for treatment planning, and breath-hold scan was acquired when indicated. In our early cases, before 2012, our SABR clinical target volume (CTV) included an 8-mm expansion of the internal gross target volume (GTV) and was further expanded by 3 mm to create the PTV. Beginning in 2012, CTV was set to zero for all SABR patients, and the PTV margin was increased to a 5-mm margin. All SABR plans were optimized by using 6-12 coplanar or non coplanar 6-MV photon beams or 1-3 arc volumetric modulated arc therapy (VMAT). Patients with a large tumor or central lesion (defined as a tumor within 2 cm of critical mediastinal structures or the brachial plexus) or who did not meet normal tissue dose-volume constraints using 50 Gy in 4 fractions were treated with 70 Gy in 10 fractions and or other regimens with lower BED (typically in the early phase of our SABR program when we were not certain about normal tissue tolerance) (20), (21). The treatment was delivered on consecutive weekdays with a break on intervening weekend days if applicable. Cone-beam CT or CT-on-rails was used to verify the tumor location, adjust coverage of the target volume, and ensure sparing of critical structures before each radiation therapy fraction. Further specifics pertaining to SABR planning used have been reported by us previously (22).

Follow-up evaluations and definition of treatment failure

Follow-up evaluations included chest CT scans every 3 months for the first 2 years, every 6 months for the next 3 years, and annually thereafter. Scanning with PET/CT was recommended at 3-12 months after SABR. Local control was defined as the absence of local failure, which included both the primary tumor and the involved lobe. Recurrence at the original tumor site (in-field recurrence) was defined as primary failure (23). Local recurrence (LR) was defined as CT evidence of progressive soft tissue abnormalities in the same lobe as the primary tumor that corresponded to PET-avid areas (maximum standardized uptake value [SUVmax] >5) at the first date of changes after SABR, or positive biopsy findings (24), whereas regional recurrence (RR) was defined as the same findings in the hila or mediastinum. Recurrence within previously uninvolved lobes or outside the thorax was defined as distant failure or distant metastasis (DM). Simultaneous failure was defined as co-occurrence of local, regional, and/or distant metastases together. Biopsy was strongly recommended to confirm suspected recurrence.

Statistical analysis

Patterns of failure were analyzed in these patient cohorts. The Kaplan-Meier method was used to estimate the probability of PFS and overall survival (OS). OS was defined as the length of time from the completion of SABR to death from any cause. PFS was defined as the length of time from the completion of SABR to the first failure at any site. Death was excluded as an event as this was not predicted to be randomly distributed in patients age ≥75. Time to local, regional, and distant recurrence was defined as the length of time to first local, regional, or distant failure. Secondary endpoints included cause of death (lung cancer vs other disease), median lung-cancer specific survival, and grade ≥3 toxicity, assessed with the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) v 4.0. Secondary analysis of OS by patient age at time of treatment was also performed (<65, 65-75, and ≥75). A 2-sided p-value <.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance. Data were analyzed with statistical software packages SPSS 21.0 (IBM, Armonk, NY) and R 3.1.2 with packages cmprsk_v2.2-7, Rarity v1.3-4, and survival_v2.38-1.

Results

Patient, tumor, and treatment characteristics

A total of 772 patients were identified, representing 764 biopsy-proven clinical stage I-II NSCLC, based on AJCC Seventh Edition TNM classification. Patients with a metastatic tumor involving the lung were not included in this study. Of these 772 patients, 330 were age ≥75, leaving 442 <75 years of age for comparative analyses. For patients in the ≥75 years of age cohort, mean age was 80.8 years and 52.7% were men. The majority of tumors were adenocarcinoma histology (51.8%), followed by squamous (36.1%) and then other (2.4%). Other than age, there were no differences in the demographics or disease characteristics of the elderly population (≥75) compared to those <75 years of age (Table 1).

Table 1.

Patient characteristics

| Characteristics | Number of patients (%)

|

P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| < 75 years (n=442) |

≥ 75 years (n=330) |

||

| Mean age, years | 67.0 | 80.8 | |

| Median age, years (range) | 68.5 (46-74) | 80.1 (75.0-91.8) | |

| Sex | 0.212 | ||

| Male | 229 (51.8) | 156 (47.3) | |

| Female | 213 (48.2) | 174 (52.7) | |

| Tumor stage* | 0.219 | ||

| T1 | 376 (85.1) | 266 (80.6) | |

| T2 (T2a: ≤5 cm, pleural invasion) | 60 (13.6) | 60 (18.2) | |

| T3 (with satellite nodule) | 6 (1.4) | 4 (1.2) | |

| Histology | 0.961 | ||

| Adenocarcinoma | 234 (52.9) | 171 (51.8) | |

| Squamous | 149 (33.7) | 119 (36.1) | |

| Other | 11 (2.5) | 8 (2.4) | |

| NSC NOS | 43 (9.7) | 29 (8.8) | |

| No pathology | 5 (1.1) | 3 (0.9) | |

The IASLC Lung Cancer Staging Project: Proposals for the revision of the TNM stage groupings in the forthcoming (seventh) edition of the TNM classification of malignant tumors. J Thorac Oncol 2007;2:706-714.

Recurrence and survival characteristics in the elderly (≥75)

For patients ≥75, the overall combined cumulative local and regional recurrence rate was 17.3% with an average follow-up time of 55.2 months. The median time to local recurrence was 14.4 months and that of regional recurrence, 9.5 months. A total of 16.7% of patients experienced distant failure at a median time of 11.7 months. OS rates were 86% at 1 year, 57.5% at 2 years, and 39.5% at 5 years.

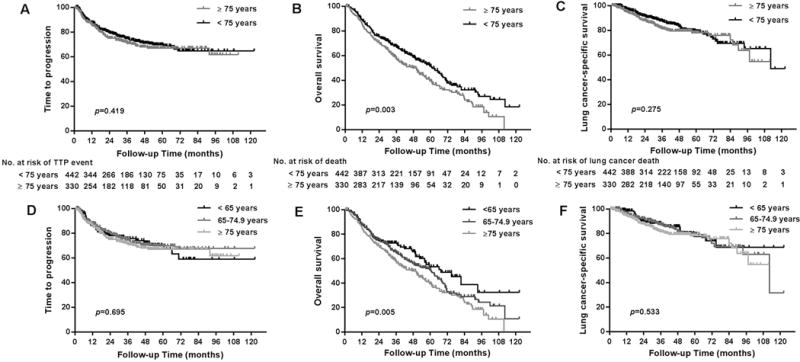

Progression-free and overall survival in patients age ≥75 compared to <75

The rates of local, regional, and distant failure did not differ between patients ≥75 years of age and those <75 years of age. There was no difference between the two groups in regard to median time to recurrence or in cancer-related mortality or lung-cancer specific survival (Table 2). There was also no difference in the PFS rate between patients age ≥75 and those <75 years of age (p=0.419; Figure 1a). OS was the same between the ≥75 and <75 age groups 2 years out from treatment, but then diverged with better overall survival seen in the younger <75 years of age cohort at 5-years (p=0.004; Figure 1b). Overall survival decreased as a function of increasing age in secondary analysis (<65, 65≤ to <75, and ≥75) (p=0.005, Figure 1c).

Table 2.

Patient outcomes

| Characteristics | Number of Patients (%)

|

P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| < 75 years (n=442) |

≥ 75 years (n=330) |

||

| First recurrence site | 111 (25.1) | 88 (26.7) | 0.625 (recurrence vs. no recurrence) |

| Local recurrence | 22 (5.0) | 14 (4.2) | |

| Regional recurrence | 26 (5.9) | 18 (5.5) | |

| Distance metastases | 45 (10.2) | 35 (10.6) | |

| Simultaneous failure | 18 (4.1) | 21 (6.4) | |

| Cumulative events | 0.763 | ||

| Local recurrence | 32 (7.2) | 23 (7.0) | |

| Regional recurrence | 40 (9.0) | 34 (10.3) | |

| Distance metastases | 60 (13.6) | 55 (16.7) | |

| Median time to any recurrence, mo (min–max) | 13.6 (2.6–70.7) | 12.0 (0.7–91.9) | 0.262 |

| Median time to LR | 14.7 (4.1-60.6) | 14.4 (3.3–91.9) | |

| Median time to RR | 12.3 (2.6-70.7) | 9.5 (2.5–41.6) | |

| Median time to DM | 14.2 (2.8-68.1) | 11.7 (0.7–91.9) | |

| Death | 210 (47.5) | 190 (57.6) | 0.006 (dead vs. alive) |

| From lung cancer | 71 (33.8) | 58 (30.5) | 0.755 (cause of death) |

| From other disease | 101 (48.1) | 94 (47.9) | |

| Unknown | 38 (18.1) | 38 (20.0) | |

| Median follow-up time, mo (min–max) | 54.6 (51.3–57.8) | 55.2 (49.6–60.8) | 0.706 |

| Median PFS time, mo PFS rates, % | Not reached | Not reached | 0.419 |

| 1 year | 87.3 | 86.0 | |

| 3 years | 74.6 | 71.3 | |

| 5 years | 69.7 | 66.9 | |

| Median OS time, mo (min–max) OS rates, % | 61.2 (53.2–69.2) | 47.7 (39.6–55.9) | 0.003 |

| 1 year | 89.1 | 86.0 | |

| 3 years | 67.6 | 57.5 | |

| 5 years | 51.5 | 39.5 | |

| Median lung cancer-specific OS time, mo | 112.3 | Not reached | 0.275 |

Abbreviations: LR, local recurrence; RR, regional recurrence; DM, distant metastasis; PFS, progression-free survival; OS, overall survival.

Fig. 1.

Kaplan-Meier estimates of progression-free survival (PFS; panel A) and overall survival (OS) (panel B) according to age <75 or ≥75 years at stereotactic ablative radiotherapy (SABR). No difference was found in PFS (P=0.475) or in OS for the first 2 years after treatment, is the same up to 2 years after treatment, but differences in OS according to age became apparent after that time (P=0.003). OS was also found to decrease as a function of age in a secondary univariate analysis (panel C, P=0.001).

Toxicity with SABR in the elderly

Overall rates of toxicity were the same between age groups (p=0.536). No patient aged ≥75 experienced any grade 4 or 5 toxic events, although one patient in the <75 group had grade 5 hemoptysis. Rates of grade 2-3 toxicity did not differ according to age for fatigue, dermatitis, esophagitis, pneumonitis, brachial plexopathy, hemoptysis, and rib fracture (Table 3). We also extracted information from the medical records on nonspecific cardiac events occurring after SABR (Table 4). The rate at which these events took place was no different in the two age groups (p=0.896), and no patient with any cardiac event after SABR had had heart radiation doses exceeding heart dose-volume constraints (Table 4). Cardiac events did not seem to correlate with left-sided treatment, V20, V40, or other radiation-related factors. Finally, most of the patients who experienced cardiac events in either group had had prior cardiovascular disease or risk factors.

Table 3.

Toxicity Incidence and Severity After SABR by Age*

| Toxicity Severity | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grade 2 | Grade 3 | |||||

| Toxicity Rates, %† | <75 | ≥75 | P Value | <75 | ≥75 | P Value |

| Fatigue | 5.9 | 5.4 | 0.875 | 0.9 | 0.0 | 0.139 |

| Dermatitis | 1.1 | 2.4 | 0.257 | 0.5 | 0.3 | 1.0 |

| Esophagitis | 0.9 | 0.9 | 1.0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Pneumonitis | 3.1 | 4.5 | 0.343 | 1.1 | 0.6 | 0.704 |

| Chest wall pain | 3.6 | 3.3 | 1.0 | 0.45 | 0.6 | 1.0 |

| Hemoptysis | 0.0 | 0.3 | 0.427 | 0 | 0 | |

| Brachial plexopathy | 0.2 | 0 | 1.0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Rib fracture | 2.7 | 1.5 | 0.326 | 0 | 0 | |

Scored according to the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events v4.0.

No patient experienced grade ≥4 toxicity except for one patient aged <75 years with grade 5 hemoptysis. There was no difference in overall events (all grades of toxicity) between both age groups (p=0.536).

Table 4.

Cardiac Events After SABR by Age

| Patient Age | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Cardiac Events | <75 years | ≥75 years | P Value |

| No. of events | 16 | 8 | 0.896 |

| Prior CVD | 81% (13/16) | 75% (6/8) | |

| Heart dose-volume metrics, mean (range) | |||

| Dmax, Gy | 15.5 (0.26–49.56) | 36.2 (2.1–69.9) | |

| Dmean, Gy | 1.54 (0.05–6.57) | 4.9 (0.56–9.3) | |

| V20, % | 0.66 (0-9) | 2.6 (0-12) | |

| V40, % | 0.0 | 0.12 (0-1) | |

| Tumor ≥2 cm from pericardium | 87.5% (14/16) | 75% (6/8) | |

| Left-sided tumor | 31.2% (5/16) | 37.5% (3/8) | |

Abbreviations: CVD, cardiovascular disease

Discussion

In NSCLC, success of CT-based surveillance has led to more elderly patients being diagnosed with early, potentially curable stage, lung cancer (2), (3). Anatomic surgical resection with lobectomy or more rarely, pneumonectomy, has been the standard of care for patients with operable early stage disease, with definitive SABR traditionally reserved for patients who are deemed medically inoperable. While surgery remains the preferred treatment for patients with good performance and pulmonary status, data consistently show that the morbidity and mortality associated with surgical resection significantly increases in elderly patients (9), (10), (25). SABR, which has reduced morbidity and mortality compared to surgery, may be a unique alternative for this population (14), (17). Although controversial, SABR, compared to surgery, has been suggested to have comparable overall and cancer-specific survival rates up to 5 years out in select patients, particularly those with small size (≤2cm) disease (13), (14), (15), (16), (17), (23), (26), (27), (28), (29), (30), (31), (33), (34). Thus, SABR, which shows excellent control and low morbidity/mortality in the average- age NSCLC population, may be particularly well positioned to treat elderly patients, particularly those who are considered operable, but may do worse after surgery when co-morbidities make them higher risk, or those who have poorer pulmonary health and are being referred to less-effective sublobar resection techniques.

To date, it has not been studied whether the low morbidity and efficacy of SABR observed in the normal NSCLC population translates to elderly patients as well. Here, we reviewed the effectiveness of SABR in patients ≥75 to those <75 years of age using the primary end points of PFS and OS. We also evaluated the incidence of toxicity-related adverse events in patients ≥75 who have received SABR treatment.

Overall, we found that PFS was not different in patients ≥75 years old compared to those <75 who received SABR treatment for early stage I-II NSCLC (67-70% disease control at 5 years). Therefore, the local and distant control benefits of SABR are maintained in younger as well as elderly patients. In terms of survival, our median OS rates were 86% at 1 year, 57.5% at 3 years, and 39.5% at 5 years for patients age ≥75. Compared with the <75 years of age cohort, survival in the ≥75 years of age patients was similar up to 2 years out of follow-up suggesting comparable early tumor control rates for both groups, with survival rates then diverging thereafter. This divergence in survival after 2 years was not surprising and was, in fact, a reflection of the increased non-cancer-related morbidity and mortality inherent to the ≥75 age group as lung cancer-related death was no different between the ≥75 and <75 age patients. Therefore, SABR also maintains its curative effectiveness in elderly patients. In terms of toxicity, SABR was extremely well tolerated in patients age ≥75. Pneumonitis incidence was low, and on the order of that observed historically in the average- age population, with only 1-2% of patients age ≥75 experiencing any grade 3 events. Importantly, no patients age ≥75 experienced any grade 4 or higher toxicity of any type. There was no significant hemoptysis, brachial plexopathy, fatigue, or esophagitis. Chest wall pain was also minimal, seen in only 1-4% of patients and managed successfully with medication. While higher radiation dosing regimens have raised concern about increasing the risk of cardiac events, we did not find this to be the case, as the nonspecific cardiac events documented in our analysis were not attributable to radiotherapy according to dosimetric variables (Table 4). Furthermore, comparison to toxicity rates in patients <75 years of age showed no difference, indicating that the very low morbidity associated with SABR is still enjoyed and maintained in elderly patients. Therefore, PFS, OS, and lung cancer-specific survival all demonstrate SABR maintains its effectiveness in the elderly, and toxicity is considered excellent in patients age ≥75 with stage I-II disease and does not differ compared to their younger counterparts. Further, the OS rates in our cohort are particularly encouraging, given the practice at our institution of referring patients who are not considered good candidates for surgery to SABR. It is very likely that OS after SABR would be even higher among older patients who are surgical candidates, because such patients who are considered operable generally have less co-morbidity.

Compared to historical outcomes of surgery in the elderly, SABR outcomes reviewed in this report appeared comparable. This suggests that SABR may be an option for operable elderly patients. In the average- age population, lobectomy offers an approximately 60-70% survival at 5-years for Stage IA disease, higher than sublobar resection, which has a survival of approximately 40-50% (12). PFS is also higher, around 80% at 5-years with lobectomy, versus 50-60% with sublobar techniques (12). However, in the elderly age population, both lobectomy and sublobar resection survival rates become significantly lower, on the order of 30%-40% at 5 years for patients with stage I-II disease (11), (35). Our report shows a highly comparable rate with SABR of roughly 40% at 5 years. Furthermore, while lobectomy is superior to sublobar surgery in the non-elderly population, lobectomy survival rates become similar to that of wedge/sublobar resection in patients age ≥75, reflecting a reduced benefit of lobectomy in older patients (36), (37). Reasons for this include the increased morbidity rates associated with the more extensive resection, as 90-day mortality more than doubles after lobectomy in patients age >70 (10), highlighting the fact that the cancer-related survival benefit with lobectomy over sublobar resection is likely offset by the increased surgical-related morbidity and mortality in this fragile population. Notably, while only 1-2% of patients ≥75 years old treated with SABR experience significant morbidity in our study (grade ≥3 toxicity), 45-50% of patients ≥70 years of age experience significant morbidity after surgery (38). Therefore, while surgery can provide excellent outcomes for some elderly patients, even octogenarians (39), many reports show surgery not only has higher morbidity, but also reduced benefit when compared to average-age patients (9), (10), (11), (25), (35), (36), (37). As shown here, however, SABR had similar effectiveness (lung cancer-related survival, PFS) and minimal toxicity in the elderly compared to non-elderly patients. Therefore, assuming comparable cancer related outcomes of SABR to surgery, and SABR’s minimal toxicity, SABR may be an option for even potentially operable elderly patients. In particular, SABR may become an option for patients referred for sublobar resection as both procedures can be considered focused localized approaches – as neither treat lymph nodes – though, surgery is more invasive. Still, long-term data on operable patients assigned to SABR or surgery in phase III randomized studies are needed to draw solid conclusions.

Overall, these results show SABR is very well tolerated in the elderly and is not compromised with respect to either toxicity or efficacy compared to younger patients. These findings should encourage clinicians who find themselves treating an elderly patient with early stage lung cancer to discuss all local treatment modalities, as morbidity related to treatment is a critical concern. This discussion ideally should take place in the setting of a multidisciplinary tumor board that includes surgeons, medical oncologists and radiation oncologists. This institutional report, the largest to date to evaluate SABR in the growing elderly population, verifies that SABR is a very safe and effective tool to treat elderly patients with early stage lung cancer.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge medical physics, dosimetry, and Christine Wogan, for their help and support.

Supported in part by Cancer Center Support (Core) Grant CA016672 from the National Cancer Institute to The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: Please refer to COI disclosures.

References

- 1.Yancik R, Ries LA. Aging and cancer in america. Demographic and epidemiologic perspectives. Hematology/oncology clinics of North America. 2000;14:17–23. doi: 10.1016/s0889-8588(05)70275-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aberle DR, et al. Reduced lung-cancer mortality with low-dose computed tomographic screening. The New England journal of medicine. 2011;365:395–409. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1102873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Henschke CI, et al. Survival of patients with stage i lung cancer detected on ct screening. The New England journal of medicine. 2006;355:1763–1771. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa060476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smith BD, et al. Future of cancer incidence in the united states: Burdens upon an aging, changing nation. Journal of clinical oncology: official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2009;27:2758–2765. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.8983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mannino DM, Buist AS. Global burden of copd: Risk factors, prevalence, and future trends. Lancet (London, England) 2007;370:765–773. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61380-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schellevis FG, et al. Comorbidity of chronic diseases in general practice. Journal of clinical epidemiology. 1993;46:469–473. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(93)90024-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vestbo J, et al. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: Gold executive summary. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2013;187:347–365. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201204-0596PP. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Edwards BK, et al. Annual report to the nation on the status of cancer, 1973-1999, featuring implications of age and aging on u.S. Cancer burden. Cancer. 2002;94:2766–2792. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jaklitsch MT, et al. New surgical options for elderly lung cancer patients. Chest. 1999;116:480s–485s. doi: 10.1378/chest.116.suppl_3.480s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rivera C, et al. Surgical management and outcomes of elderly patients with early stage non-small cell lung cancer: A nested case-control study. Chest. 2011;140:874–880. doi: 10.1378/chest.10-2841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mery CM, et al. Similar long-term survival of elderly patients with non-small cell lung cancer treated with lobectomy or wedge resection within the surveillance, epidemiology, and end results database. Chest. 2005;128:237–245. doi: 10.1378/chest.128.1.237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ginsberg RJ, Rubinstein LV. Randomized trial of lobectomy versus limited resection for t1 n0 non-small cell lung cancer. Lung cancer study group. The Annals of thoracic surgery. 1995;60:615–622. doi: 10.1016/0003-4975(95)00537-u. discussion 622-613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chang JY, et al. Stereotactic ablative radiotherapy versus lobectomy for operable stage i non-small-cell lung cancer: A pooled analysis of two randomised trials. The Lancet Oncology. 2015;16:630–637. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(15)70168-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Crabtree TD, et al. Stereotactic body radiation therapy versus surgical resection for stage i non-small cell lung cancer. The Journal of thoracic and cardiovascular surgery. 2010;140:377–386. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2009.12.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Paul S, et al. Long term survival with stereotactic ablative radiotherapy (sabr) versus thoracoscopic sublobar lung resection in elderly people: National population based study with propensity matched comparative analysis. BMJ (Clinical research ed) 2016;354:i3570. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i3570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shirvani SM, et al. Lobectomy, sublobar resection, and stereotactic ablative radiotherapy for early-stage non-small cell lung cancers in the elderly. JAMA surgery. 2014;149:1244–1253. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2014.556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Verstegen NE, et al. Stage i-ii non-small-cell lung cancer treated using either stereotactic ablative radiotherapy (sabr) or lobectomy by video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (vats): Outcomes of a propensity score-matched analysis. Annals of oncology: official journal of the European Society for Medical Oncology. 2013;24:1543–1548. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdt026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chang JY, et al. Clinical outcome and predictors of survival and pneumonitis after stereotactic ablative radiotherapy for stage i non-small cell lung cancer. Radiation oncology (London, England) 2012;7:152. doi: 10.1186/1748-717X-7-152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chang JY, et al. Stereotactic ablative radiotherapy: A potentially curable approach to early stage multiple primary lung cancer. Cancer. 2013;119:3402–3410. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chang JY, et al. Stereotactic ablative radiation therapy for centrally located early stage or isolated parenchymal recurrences of non-small cell lung cancer: How to fly in a “no fly zone”. International journal of radiation oncology, biology, physics. 2014;88:1120–1128. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2014.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang X, et al. Positron emission tomography for assessing local failure after stereotactic body radiotherapy for non-small-cell lung cancer. International journal of radiation oncology, biology, physics. 2012;83:1558–1565. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2011.10.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhao L, et al. Planning target volume d95 and mean dose should be considered for optimal local control for stereotactic ablative radiation therapy. International journal of radiation oncology, biology, physics. 2016;95:1226–1235. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2016.01.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lagerwaard FJ, et al. Outcomes of risk-adapted fractionated stereotactic radiotherapy for stage i non-small-cell lung cancer. International journal of radiation oncology, biology, physics. 2008;70:685–692. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2007.10.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li Q, et al. Stereotactic ablative radiotherapy (sabr) using 70 gy in 10 fractions for non-small cell lung cancer: Exploration of clinical indications. Radiotherapy and oncology: journal of the European Society for Therapeutic Radiology and Oncology. 2014;112:256–261. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2014.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ginsberg RJ, et al. Modern thirty-day operative mortality for surgical resections in lung cancer. The Journal of thoracic and cardiovascular surgery. 1983;86:654–658. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Grills IS, et al. Outcomes after stereotactic lung radiotherapy or wedge resection for stage i non-small-cell lung cancer. Journal of clinical oncology: official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2010;28:928–935. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.25.0928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lagerwaard FJ, et al. Outcomes of stereotactic ablative radiotherapy in patients with potentially operable stage i non-small cell lung cancer. International journal of radiation oncology, biology, physics. 2012;83:348–353. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2011.06.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Palma D, et al. Treatment of stage i nsclc in elderly patients: A population-based matched-pair comparison of stereotactic radiotherapy versus surgery. Radiotherapy and oncology: journal of the European Society for Therapeutic Radiology and Oncology. 2011;101:240–244. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2011.06.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Robinson CG, et al. Patterns of failure after stereotactic body radiation therapy or lobar resection for clinical stage i non-small-cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2013;8:192–201. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e31827ce361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rosen JE, et al. Lobectomy versus stereotactic body radiotherapy in healthy patients with stage i lung cancer. The Journal of thoracic and cardiovascular surgery. 2016;152:44–54 e49. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2016.03.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Taremi M, et al. Stereotactic body radiotherapy for medically inoperable lung cancer: Prospective, single-center study of 108 consecutive patients. International journal of radiation oncology, biology, physics. 2012;82:967–973. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2010.12.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Timmerman R, et al. Stereotactic body radiation therapy for inoperable early stage lung cancer. Jama. 2010;303:1070–1076. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zheng X, et al. Survival outcome after stereotactic body radiation therapy and surgery for stage i non-small cell lung cancer: A meta-analysis. International journal of radiation oncology, biology, physics. 2014;90:603–611. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2014.05.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Noordijk EM, et al. Radiotherapy as an alternative to surgery in elderly patients with resectable lung cancer. Radiotherapy and oncology: journal of the European Society for Therapeutic Radiology and Oncology. 1988;13:83–89. doi: 10.1016/0167-8140(88)90029-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kilic A, et al. Anatomic segmentectomy for stage i non-small cell lung cancer in the elderly. The Annals of thoracic surgery. 2009;87:1662–1666. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2009.02.097. discussion 1667-1668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Okami J, et al. Sublobar resection provides an equivalent survival after lobectomy in elderly patients with early lung cancer. The Annals of thoracic surgery. 2010;90:1651–1656. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2010.06.090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Allen MS, et al. Morbidity and mortality of major pulmonary resections in patients with early-stage lung cancer: Initial results of the randomized, prospective acosog z0030 trial. The Annals of thoracic surgery. 2006;81:1013–1019. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2005.06.066. discussion 1019-1020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dell’Amore A, et al. Lobar and sub-lobar lung resection in octogenarians with early stage non-small cell lung cancer: Factors affecting surgical outcomes and long-term results. General thoracic and cardiovascular surgery. 2015;63:222–230. doi: 10.1007/s11748-014-0493-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]