Abstract

Toxoplasma gondii aspartyl protease 3 (TgASP3) phylogenetically clusters with Plasmodium falciparum Plasmepsins IX and X (PfPMIX, PfPMX). These proteases are essential for parasite survival, acting as key maturases for secreted proteins implicated in invasion and egress. A potent antimalarial peptidomimetic inhibitor (49c) originally developed against Plasmepsin II selectively targets TgASP3, PfPMIX, and PfPMX. To unravel the molecular basis for the selectivity of 49c, we constructed homology models of PfPMIX, PfPMX, and TgASP3 that were first validated by identifying the determinants of microneme and rhoptry substrate recognition. The flap and flap‐like structures of several reported Plasmepsins are highly flexible and critically modulate the access to the binding cavity. Molecular docking of 49c to TgASP3, PfPMIX, and PfPMX models predicted that the conserved phenylalanine residues in the flap, F344, F291, and F305, respectively, account for the sensitivity toward 49c. Concordantly, phenylalanine mutations in the flap of the three proteases increase twofold to 15‐fold the IC 50 values of 49c. Compellingly the selection of mutagenized T. gondii resistant strains to 49c reproducibly converted F344 to a cysteine residue.

Keywords: Aspartyl protease, modeling, Plasmepsin, Plasmodium, Toxoplasma

Subject Categories: Microbiology, Virology & Host Pathogen Interaction; Post-translational Modifications, Proteolysis & Proteomics; Structural Biology

Introduction

The phylum of Apicomplexa includes a large number of obligate intracellular parasites responsible for a wide variety of diseases in humans and animals. Toxoplasma gondii is a ubiquitous, opportunistic pathogen causing toxoplasmosis that can be lethal for immunocompromised individuals and can lead to birth defects or miscarriage during pregnancy (Montoya & Liesenfeld, 2004). Plasmodium falciparum is responsible for the most life‐threatening form of malaria and is one of the top ten causes of worldwide death, with half the world's population currently at risk. The rapid emergence of drug resistance against most of the available antimalarials has further worsened the situation (Daily, 2017). Additionally, Cryptosporidium is a leading cause of waterborne, diarrheal disease among humans, while other apicomplexans including Eimeria, Theileria, and Babesia spp. infect a large number of agricultural animals and are responsible for considerable economic losses (McDonald & Shirley, 2009; Goodswen et al, 2013). Until now, no vaccine or eradicating drug treatments are available against this important group of pathogens (Seeber & Steinfelder, 2016).

Aspartyl proteases are present in all eukaryotes, implicated in a broad range of functions, and therefore represent excellent targets for intervention. In apicomplexans, the aspartyl proteases exhibit several characteristics including two conserved catalytic motifs DTGS or DTGS/DSGT/DTGT, optimal for activity in acidic pH conditions, as well as a polyproline loop and a flap predicted to close over the active site, thereby influencing substrate specificity. Previous studies have reported on the importance of the flap in regulating the opening and closing of the enzyme and thereby providing access or not, to the active site (Karubiu et al, 2015).

The apicomplexan aspartyl proteases group into distinct phylogenetic clusters and share similar biological functions (Shea et al, 2007). Toxoplasma gondii possesses seven genes coding for aspartyl proteases among them TgASP1, TgASP3, and TgASP5 are expressed in the fast‐replicating tachyzoites responsible for acute infection. The human malaria parasite P. falciparum possesses 10 genes, coding for the Plasmepsins. PfPMVI, VII, and VIII are expressed in the exo‐erythrocytic stages (Banerjee et al, 2003). The Plasmepsins expressed during the early‐erythrocytic stages (PfPMI II, IV, and HAP) are localized to the food vacuole and involved in hemoglobin degradation, while the endoplasmic reticulum PfPMV is implicated in the cleavage of proteins destined for export into the host cell. TgASP5 and PfPMV belong to the same cluster and share 33% sequence similarity with key features including an N‐terminal signal peptide, a core aspartyl protease domain, and a C‐terminal transmembrane domain (Hodder et al, 2015). Both proteases are involved in the export of parasite proteins across the parasitophorous vacuole membrane into the host cell (Coffey et al, 2015; Hammoudi et al, 2015; Bedi et al, 2016). PfPMIX and PfPMX are expressed in late schizonts as well as in other invasive stages of the parasite life cycle. TgASP3 is phylogenetically related to PfPMIX and PfPMX, and members of this cluster act as maturases for microneme and rhoptry proteins, playing a crucial role in invasion and in egress in both parasites, respectively (Dogga et al, 2017; Nasamu et al, 2017; Pino et al, 2017). Given their broad relevance in infectious diseases and druggability, aspartic proteases have been largely prioritized as targets for chemotherapy (Meyers & Goldberg, 2012; Huizing et al, 2015). While inhibitors targeting the HIV aspartic protease are potent components of antiretroviral therapies, the inhibitors directed against the malaria hemoglobin‐degrading enzymes became unattractive due to dispensability of these Plasmepsins for parasite survival (Silva et al, 1996; Coombs et al, 2001; Andrews et al, 2006). Recently, a peptidomimetic compound WEHI‐842 as well as a hydroxy‐ethylamine derivative, compound 1 (Arg‐Leu‐[Leu‐HEA‐Ala]‐Glu‐Ala), has been developed to specifically target PMV, mimicking the PEXEL motif involved in substrate recognition (Gambini et al, 2015; Hodder et al, 2015). Moreover, among the hydroxy‐ethylamine scaffold inhibitors directed against Plasmepsin II (PfPMII; Ciana et al, 2013), a few derivatives including compound 49c showed very potent antimalarial effects only after 72 h of treatment with an IC50 of 0.6 nM. Remarkably, 49c blocks invasion and egress of P. falciparum without impacting intraerythrocytic growth (Pino et al, 2017). Moreover, 49c but not 49b specifically inhibits recombinant PfPMIX and PfPMX (r‐PMIXFlag and r‐PMXFlag), recapitulating the defect in invasion and egress of P. falciparum in the erythrocytic blood stages (Pino et al, 2017).

Of relevance, 49c also interferes with invasion and egress in T. gondii by targeting TgASP3 (Dogga et al, 2017). The molecular basis for the selective and powerful action of 49c on the members of this cluster is so far unknown. While crystal structures of PfPMI, II, IV, and V have been solved (Bhaumik et al, 2011; Jaudzems et al, 2014; Hodder et al, 2015; Recacha et al, 2015), no structural data for TgASP3, PfPMIX, and PfPMX exist.

Here, we have generated homology models for TgASP3, PfPMIX, and PfPMX. The three models combined with molecular docking and in vitro experiments were used to address the question of substrate and inhibitor selectivity for this class of enzymes. The three models were tested and validated by interrogating the mechanism of recognition among a series of recently identified rhoptry and microneme protein substrates. A conserved sequence motif “SFVE” was found in almost all the investigated substrates except for TgMIC6, which was further investigated. Structural and sequence comparisons identified conserved phenylalanine residues in the flap and in the adjacent hydrophobic pocket predicted to be critical for the binding of 49c and for discriminating the activities of the series of derivatives of this compound (Ciana et al, 2013). Site‐specific mutations of the predicted key residues in PfPMIX, PfPMX, and TgASP3 led to an increased resistance to 49c without altering its substrate specificity. The importance of the F344 in the flap region of TgASP3 was further supported by the isolation of chemically mutagenized parasites resistant to 49c that reproducibly exhibited a F344C mutation. In light of the shared features between TgASP3, PfPMIX, and PfPMX, the findings reported here should facilitate the rational design of improved, novel, and orally available small molecule‐based antimalarials (Huizing et al, 2015).

Results

Modeling of PfPMIX, PfPMX, and TgASP3 to explore the principles of substrate recognition

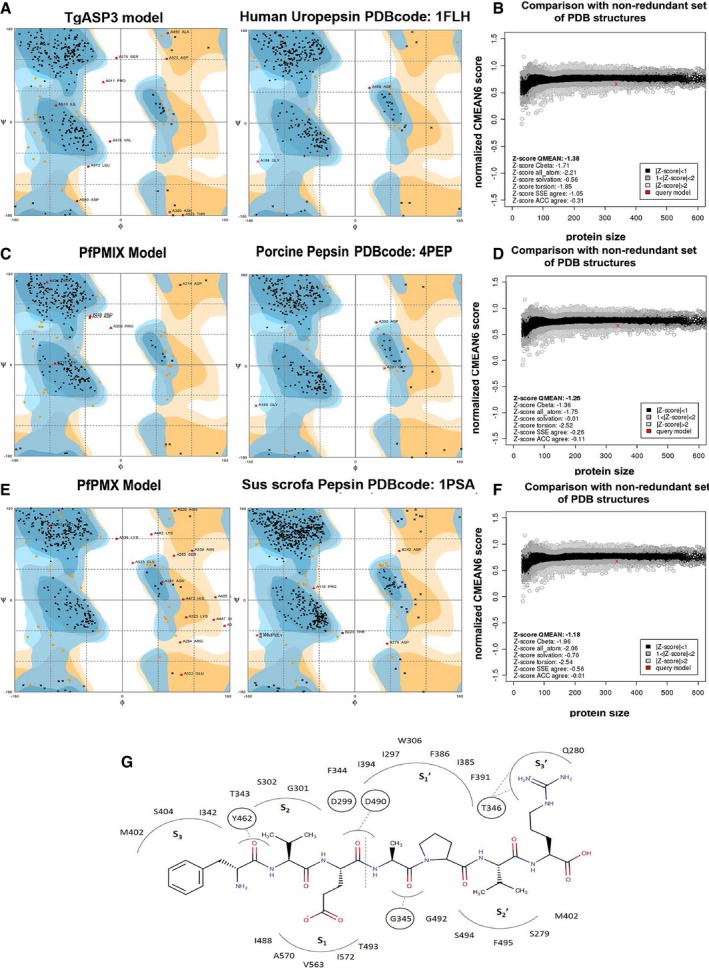

The homology models of the catalytic domain of PfPMIX (Ile 221–Val 608), PfPMX (Ile 229–Lys 564), and TgASP3 (Ile 273–Val 603) were generated based on the amino acid sequence similarity with the following template: porcine pepsin (PDB codes 4PEP, 1PSA) and human uropepsin (PDB code 1FLH). For the three models, the template similarity was around 50%, which is considered sufficient to generate suitable homology models for structure‐based studies in absence of an experimental structure (Schmidt et al, 2014). When superposed to TgASP3, the three models overlap (Fig 1A) with root‐mean‐square deviation (RMSD) values of 1.36 and 1.21 Å for PfPMIX and PfPMX, respectively. The models also recapitulate the typical structural features of the aspartyl proteases (Dunn, 2002; Appendix Fig S1). The two topologically similar domains consist of two β‐sheet lobes that are connected by a pseudo twofold axis. The overall structure can be divided into three parts: the N‐terminal lobe, the central domain composed by five antiparallel β‐sheets forming the backbone of the active site, where the two conserved catalytic aspartic acids (D299 and D490 in TgASP3) are located, and the C‐terminal lobe. The N‐terminal domain contains a β‐hairpin structure, also called flap (F344–G347 in TgASP3) that lies perpendicularly over the active site, facing the flexible loop located at the C‐terminal domain. The QMEAN normalized score, which reflects the global model prediction and ranges from 0 to 1, estimates the quality of the model as good with a value of 0.67 for the PfPMIX and PfPMX and 0.66 for the TgASP3. The quality of the models is further underlined by the QMEAN Z‐Score values of −1.26, −1.18, and −1.38, respectively (Fig EV1B, D and F), where the QMEAN Z‐Score estimates the absolute quality of the model by relating it to a non‐redundant set of reference crystal structures (Benkert et al, 2011). The geometrical quality of the models was assessed via Ramachandran analysis, and the results indicate that the models’ quality is comparable to the ones of the templates (Fig EV1A, C and E). All the residues forming the binding site studied in this work are in the favored regions of the Ramachandran plot.

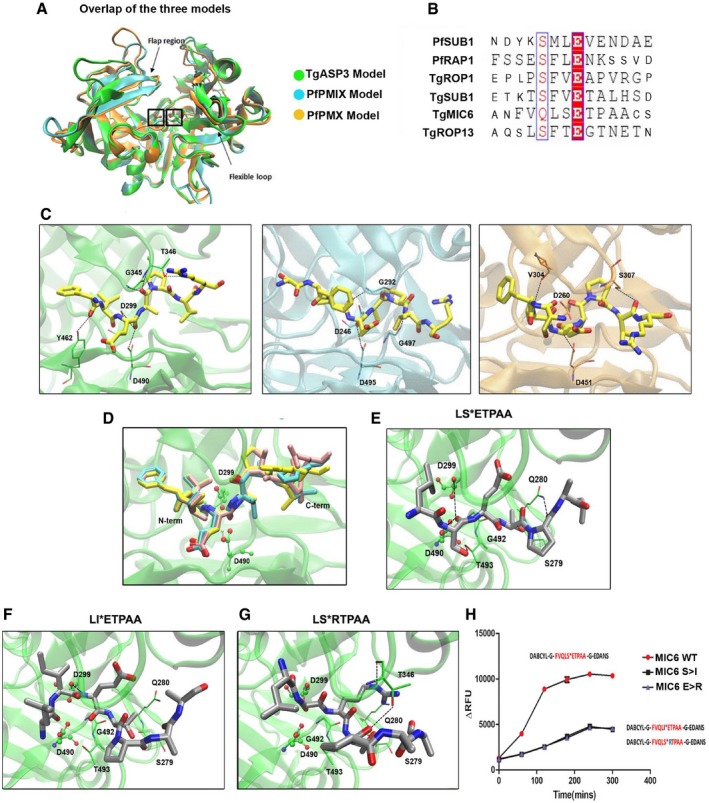

Figure 1. TgASP3 residues involved in substrate recognition.

-

AOverlap of the three models: TgASP3 (green), PfPMIX (cyan), and PfPMX (orange). The catalytic aspartyl residues are marked with a box, while arrows indicate the flexible loop and the flap region.

-

BSequence alignment of the rhoptry and microneme substrates used for the cleavage assay. Synthetic peptides used in the assay are represented in large font.

-

CThe conserved “productive” binding modes of the substrate TgROP1 (yellow) in the three different proteases active sites. From left to right: TgASP3 (green), PfPMIX (cyan), and PfPMX (orange).

-

DOverlap of the docking solutions of the three peptides: TgROP1 (yellow), TgROP13 (pink), and TgSUB1 (cyan). All the peptides are represented in licorice with the P1 and residues colored as atom type (Fig EV1G).

-

EProposed binding mode of TgMIC6 peptide (LSETPAA) in TgAsp3, shown in gray with atom type specified. The side chains of the main interacting residues are reported in licorice with carbon colored in green, and the hydrogen bonds are outlined with black dotted lines.

-

F, GDocking solutions of TgMIC6 mutant peptides: TgMIC6 S>I (F) and TgMIC6 E>R (G). The side chains of the main interacting residues are shown in green; the hydrogen bonds are outlined with black dotted lines.

-

HImmunoprecipitated ASP3ty cleaves wild‐type TgMIC6 peptide (DABCYL‐G‐VQLSETPA‐G‐EDANS) more efficiently than TgMIC6 mutant peptides (DABCYL‐G‐VQLIETPA‐G‐EDANS, DABCYL‐G‐VQLSRTPA‐G‐EDANS). Data represent mean ± SEM, n = 3, from a representative experiment out of three independent assays.

Figure EV1. TgASP3 model validation.

- Ramachandran plot of the TgASP3 model (89.4% favored regions, 7.6% allowed region, and 3.0% outliers) and the corresponding template structure human uropepsin (95.7% favored regions, 3.7% allowed regions, and 0.6% outliers; PDB code: 1FLH) obtained with the http://mordred.bioc.cam.ac.uk/~rapper/rampage.php.

- The Z‐QMEAN score of TgASP3 model compared to a non‐redundant set of PDB structures.

- Ramachandran plot of the PfPMIX model (88.6% favored region, 9.6% allowed region, and 1.8% outliers) and the corresponding template structure of the porcine pepsin (95.6% favored region, 3.4% allowed region, and 0.9% outliers; PDB code: 4PEP)

- The Z‐QMEAN score of PfPMIX model compared to a non‐redundant set of PDB structures.

- Ramachandran plot of the PMX model (85.6% favored region, 9.9% allowed region, and 4.5% outliers) and the corresponding template structure of the Sus scrofa pepsin (95.1% favored region, 4.0% allowed region, and 0.9% outliers; PDB code: 1PSA).

- The Z‐QMEAN score of PfPMX model compared to a non‐redundant set of PDB structures.

- Schematic representation of the TgROP1 binding mode in the TgASP3 binding site. The vertical dotted line indicates the peptide cleavage site. The black dotted lines represent the H‐bonds.

Recently, a set of microneme (TgMIC6, TgSUB1, and PfSUB1) and rhoptry proteins (TgROP1, TgROP13, and PfRAP1) processed at known cleavage sites were identified as substrates of PfPMIX, PfPMX, or TgASP3 (Dogga et al, 2017; Pino et al, 2017; Fig 1B). Importantly, while PfRAP1 and PfSUB1 are selectively cleaved by PfPMIX and PfPMX, respectively, TgROP1 is processed by all three proteases (Dogga et al, 2017; Pino et al, 2017). As the common substrate, TgROP1 shows a similar orientation to the three proteases, pointing the backbone carbonyl of the glutamate in a catalytically favorable position allowing for cleavage at the predicted site (Fig 1C). This substrate orientation is referred to as “productive” binding mode since it allows the substrate to be cleaved, generating the expected peptide products. The docking of PfRAP1 in the three models clearly shows the presence of a major number of “productive” binding modes for PfPMIX in comparison with PfPMX and TgASP3 (Table 1). Similarly, PfSUB1 also recapitulates a major number of “productive” binding modes for PfPMX.

Table 1.

Statistic data of TgROP1, PfRAP1, and PfSUB1 docking poses to assess the substrate specificity against the three models

| TgASP3 | PfPMIX | PfPMX | |

|---|---|---|---|

| TgROP1 |

7 productive BM 76 correct N‐C term orientation |

11 productive BM 42 correct N‐C term orientation |

4 productive BM 26 correct N‐C term orientation |

| PfRAP1 |

0 productive BM 29 correct N‐C term orientation |

6 productive BM 31 correct N‐C term orientation |

2 productive BM 45 correct N‐C term orientation |

| PfSUB1 |

0 productive BM 50 correct N‐C term orientation |

3 productive BM 41 correct N‐C term orientation |

5 productive BM 64 correct N‐C term orientation |

Among the 100 orientations produced by the docking, we report the number of the ones having the same N‐ C‐terminal orientation of the peptide like in the reference protease. To calculate the number of “productive” binding mode (BM), we chose the BM of TgROP1 in TgASP3, PfRAP1 in PfPMIX, and PfSUB1 in PfPMX as reference and considered the poses that repurposed the reference BM as “productive” BM. BM, binding mode.

We describe the binding of TgROP1 to TgASP3 as a representative substrate binding mode. The hydrophobic residues at the N‐terminal part of TgROP1 occupy the S2 and S3 cavities, respectively, whereas the glutamate residue at the P1 position is inserted in the S1 pocket (Fig EV1G). Moreover, the side chain of the arginine interacts with the T346, presumably stabilizing a closed conformation of the flap. The sequence preceding the cleavage sites “SFVE*” for TgSUB1 and TgROP1, “SFTE*” for TgROP13, “SFLE*” for PfRAP1, and “SMLE*” for PfSUB1 was found to be similar among the investigated substrates, indicating a conserved motif recognized by these proteases (Bradley & Boothroyd, 1999; Turetzky et al, 2010; Fig 1B). In agreement with this, the docking poses of TgROP1, TgROP13, and TgSUB1 within TgASP3 perfectly overlap concerning the orientation and space occupancy (Fig 1D).

In contrast, TgMIC6 cleavage site (VQLS|ETPAA) does not exhibit the conserved “SFVE” like motif. In order to determine the relevant features for the substrate recognition, the LSETPAA sequence of TgMIC6 peptide was docked into the active site of TgASP3. The “productive” binding mode supported the cleavage site previously mapped between the serine (P1 position) and the glutamate ( position; Meissner et al, 2002a), where the backbone carbonyl P1 can interact with the two catalytically active aspartic acid residues (Fig 1E). Given the atypical sequence at the cleavage site of TgMIC6 compared to the other substrates, we further explored the cleavage site (S/E) with the insertion of two point mutations in the peptide sequence (isoleucine at P1 and arginine at positions) in order to assess the interference with the cleavage. The docking revealed that the sequence modification induces a disruption of the binding interactions, suggesting that the peptide would be inefficiently cleaved. The replacement of S94 in TgMIC6 with a bulkier isoleucine residue imposes a rotation of the peptide followed by isoleucine occupying the S2 cavity and forcing out the leucine at P2 position (Fig 1F). While maintaining the interaction with T346 of the pocket, the arginine mutation in (LSRTPAA) leads to a torsion of the backbone penalizing the interaction of the carbonyl of serine (P1) with the catalytic dyad and thus affecting the cleavage capacity (Fig 1G). The computational predictions were confirmed experimentally via a cleavage assay using immunoaffinity purified ASP3‐Ty from T. gondii and fluorogenic peptides corresponding to TgMIC6 wild‐type (VQLS|ETPAA) and TgMIC6 mutants (VQLI|ETPAA and VQLS|RTPAA). As predicted, the two mutant peptides were inefficiently cleaved by ASP3‐Ty in vitro thus validating the docking results (Fig 1H).

Docking of hydroxy‐ethylamine scaffold‐based compounds on the three aspartyl proteases

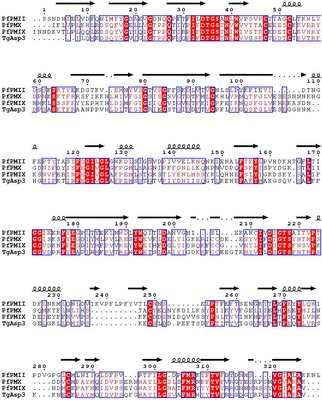

Multiple‐sequence alignment of PfPMIX, PfPMX, and TgASP3 shows an identity ~50%. The DTGS and DSGTS (DTGTS for PfPMX) motifs contain the conserved catalytically active aspartic acid residues (Fig EV2). In particular, the flap region is well conserved among the apicomplexan aspartyl proteases as previously reported (Karubiu et al, 2015) and plays a crucial role in substrate recognition (Karubiu et al, 2015). From a structural point of view and consistent with the experimentally determined structural templates, we noticed that F344, localized in the flap region of TgASP3 model, was pointing toward the binding site, in an “open” position, whereas F291 and F305 are oriented in a “close” conformation in PfPMIX and PfPMX, respectively (Fig 2A). Indeed, crystallographic studies on different uncomplexed and complexed proteases as reported for PfPMI II and HIV‐1 demonstrate the existence of different conformations between free and ligand‐bound proteases, thus, pointing out the high flexibility of this region and its crucial role during ligand accommodation (Asojo et al, 2003; Hornak et al, 2006; Bhaumik et al, 2011).

Figure EV2. PfPMIX and PfPMX models validation.

Multi‐sequence alignment between TgASP3, PMIX, PMX, and PMII. DTGS and DSGTS motifs are highlighted with box. The image was obtained using the ESPript web‐based tool (http://espript.ibcp.fr/ESPript/ESPript/).

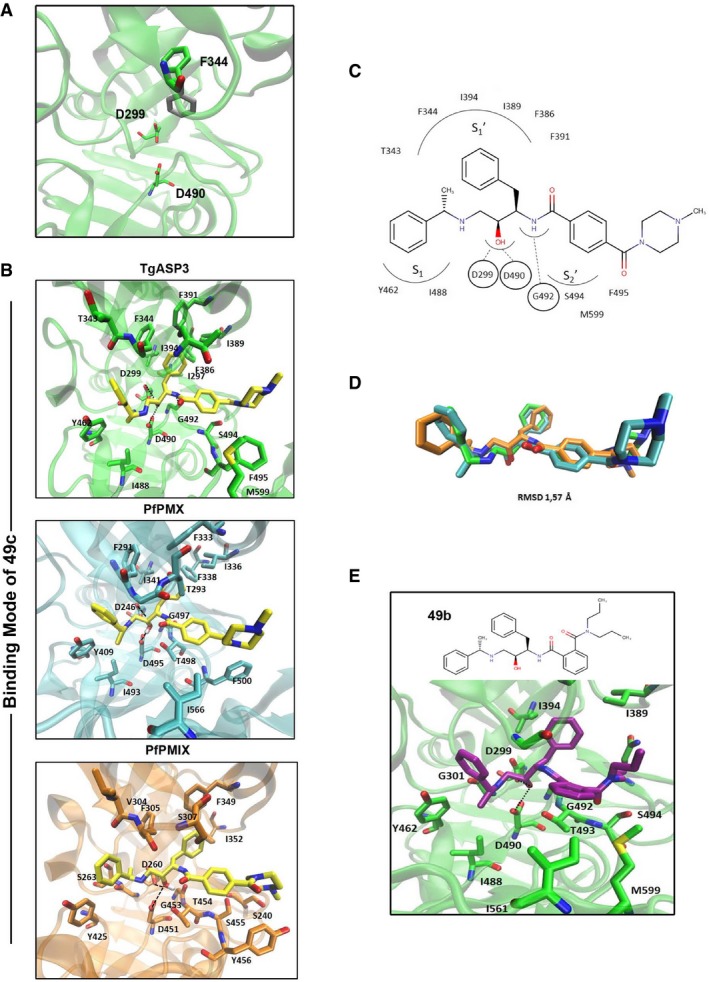

Figure 2. Compound 49c specificity toward PfPMIX, PfPMX, and TgASP3.

- Possible orientations of the F344 located in the Flap region: open conformation (colored in gray) and close conformation (colored in green). The two aspartic acids are reported for completeness. The residues are depicted in licorice.

- The comparable binding mode of 49c between TgASP3 (green), PfPMIX (cyan), and PfPMX (orange). The ligand (colored in yellow) and also the main protein residues are represented in licorice. The key interactions of the catalytic dyad with the hydroxyl group of the compound are shown with black dotted lines (hydrogen bonds).

- Schematic representation of the binding mode of 49c in TgASP3. For clearness, only the interacting residues are reported.

- Superposition of the three binding modes of 49c: In green is the docking solution obtained with TgASP3, in cyan with PfPMIX, and in orange with PfPMX. The RMSD value is 1.57 Å.

- Docking solution of compound 49b in TgASP3. The ligand (colored in magenta) and also the main protein residues are represented with licorice. The key interactions of the catalytic dyad with the hydroxyl group of the compound are shown with black dotted lines (hydrogen bonds).

49c has an IC50 ~ 700 nM against T. gondii tachyzoites ex vivo (Dogga et al, 2017) and an IC50 of ~ 0.6 nM against P. falciparum (Ciana et al, 2013; Table 2). Docking of 49c showed comparable binding mode on the three modeled structures (RMSD 1.57 Å; Fig 2B and D). As described for other hydroxy‐ethylamine compounds, the catalytic dyad (D299–D490 in TgASP3) interacts with the central hydroxyl group, which mimics the transition‐state formed during the cleavage of the peptide (Jaudzems et al, 2014). A second hydrogen bond that strengthens the binding interaction is formed between the benzamide and the backbone carbonyl group of the glycine G492 in TgASP3 (G497 in PfPMIX and G453 in PfPMX).

Table 2.

Comparison of IC50 values determined in different experimental conditions

| ID | IC50 of 49c against | IC50 of 49f against | IC50 of 49b against | IC50 of pyrimethamine against |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P. falciparum parasite | ~0.6 nM (Ciana et al, 2013) | ~0.9 nM (Ciana et al, 2013) | > 500 nM (Ciana et al, 2013) | ND |

| RHCBG99 luciferase T. gondii parasite | ~700 nM (Dogga et al, 2017) | ~500 nM | > 10 μM (Dogga et al, 2017) | ~300 nM (Dogga et al, 2017) |

| Ku80Luc T. gondii parasite | ~700 nM | ND | > 10 μM | ~300 nM |

| Ku80LucASP3/F386Y T. gondii parasite | 2.1 μM | ND | > 10 μM | ~300 nM |

| ASP3ty IP | ~6 nM | ND | > 1 μM | ND |

| ASP3tyF344Y IP | ~50 nM | ND | > 1 μM | ND |

| ASP3tyF386Y IP | ~50 nM | ND | > 1 μM | ND |

| ASP3tyF344C IP | ~40 nM | ND | > 1 μM | ND |

| r‐PfPMIX WT | ~650 nM | ND | > 1 μM | ND |

| r‐PfPMIXF291Y | ~1 μM | ND | > 1 μM | ND |

| r‐PfPMX WT | ~3 nM | ND | > 1 μM | ND |

| r‐PfPMXF305Y | ~45 nM | ND | > 1 μM | ND |

Table comparing IC50 values previously reported elsewhere or reported 1st time in this work. ND, not determined.

In the three complexes, extended protein‐49c interactions are hydrophobic in nature; the two phenyl moieties at the right‐hand side of the amide bond fit in the two hydrophobic pockets and S1 (Fig 2C). 49c was compared to compound 49b, another hydroxy‐ethylamine derivative, which is considerably less active against T. gondii (IC50 ~ 10 μM; Dogga et al, 2017) and P. falciparum (IC50 > 500 nM; Ciana et al, 2013; Table 2). The binding orientation of 49b is similar to 49c; however, the binding pocket does not accommodate deep binding of 49b because the substituent in the ortho position of the second phenyl ring partially hinders its entrance into pocket (Fig 2E). Moreover, within the same series, 49f harboring the para substituent behaves as 49c (IC50 ~ 0.9 nM against P. falciparum; Ciana et al, 2013) and ~500 nM against T. gondii (Fig EV3A, Table 2). This suggests that the cavity of these enzymes favors the binding of stretched molecules and thus this binding propensity may account for the specificity of these hydroxy‐ethylamine derivatives toward PfPMIX, PfPMX, and TgASP3. Furthermore, the modeling predictions also suggest that F344 and F386 in TgASP3, F291 and F338 in PfPMIX, F305 and F355 in PfPMX in the flap and flap‐like hydrophobic pocket, respectively, are presumably critical for the binding of 49c. Remarkably, F344/F291/F305 is replaced by a tyrosine (Y) residue in all the other PfPMs and TgASPs that belong to the distinct phylogenic cluster (Fig EV3B). In contrast, F386 is rigorously conserved in all the TgASPs (ASP1‐7) and in PfPMIX, PfPMX, and PfPMV, whereas it is replaced by a tyrosine residue in the hemoglobin‐degrading Plasmepsins (Fig EV3B). Of relevance, 49c targets selectively TgASP3 and not TgASP5 (Dogga et al, 2017), and concordantly, a comparison between TgASP5 and TgASP3 models highlights important differences in their active sites. Indeed, the presence of Y504 and the hindrance caused by the E506 in the flap of TgASP5 (F344 and T346 in TgASP3) are plausibly responsible for the absence of binding to 49c (Fig EV3C). Moreover, an inspection of the existing crystal structure of the Plasmodium vivax PMV (PDB code: 4ZL4) shows the presence of the same Y139 and the hindrance of E141 residue in the flap that may account for the anticipated resistance to 49c.

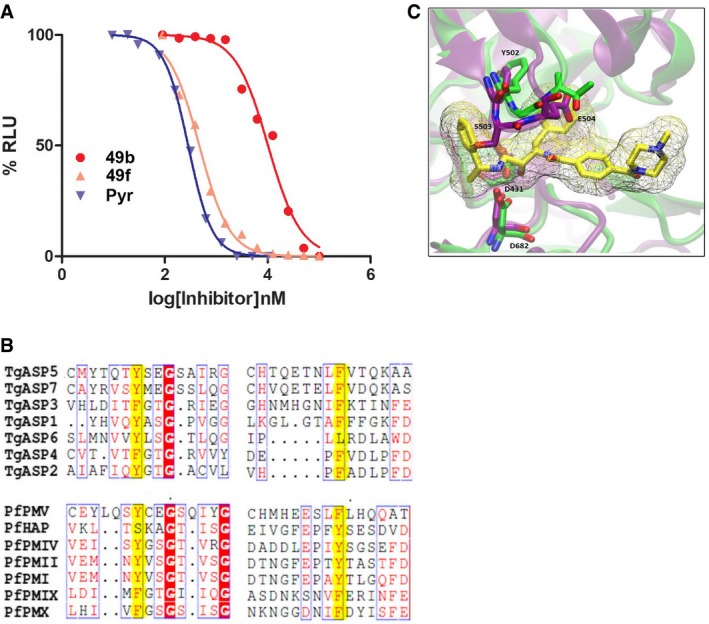

Figure EV3. 49c and 49f specifically target TgASP3.

- Dose–response curve showing significant decrease in growth inhibition of RHCBG99 luciferase parasite in presence of 49b compared to 49f and pyrimethamine. Data represent mean ± SEM, n = 2, from a representative experiment out of three independent assays.

- Multiple amino acid sequence alignment of aspartyl proteases from T. gondii (TgASP5, TgASP7, TgASP3, TgASP1, TgASP6, TgASP4, TgASP2) and P. falciparum (PfPMV, PfHAP, PfPMIV, PfPMII, PfPMI, PfPMIX, and PfPMX) using Espript3 server. The highlighted region reflected amino acids in position 344 and 386 in the Flap and Flap‐like hydrophobic pocket.

- Highlight of the main difference in the Flap region between and TgAsp5 (purple) and TgASP3 (green) with the docking solution of compound 49c (yellow). The ligand is represented with a wireframe surface; meanwhile, the relevant residues and the compound structure are depicted in licorice considering the numeration of the TgASP5 sequence.

Mutation of phenylalanine to tyrosine in the flap causes a decrease in inhibition of PfPMIX and PfPMX by 49c

In order to investigate the role of the phenylalanine residue in the flap, in conferring sensitivity to 49c, we produced and purified r‐PMIXFlag‐F291Y and r‐PMXFlag‐F305Y and compared them to the wild‐type (WT) enzymes. Incubation of r‐PMIXFlag in the presence of 1 μM of 49c leads to an accumulation of the protein, which is not observed, with r‐PMIXFlag‐F291Y (Appendix Fig S2A). Similarly, in the presence of 50 nM 49c, r‐PMXFlag‐F305Y showed a reduced accumulation of the protein as compared to r‐PMXFlag (Appendix Fig S2B). The introduction of the F to Y mutation does not alter the processing of TgROP1 peptide, as both r‐PMIXFlag‐F291Y and r‐PMXFlag‐F305Y readily cleave TgROP1 peptide like their WT counterparts, as reported previously (Pino et al, 2017; Appendix Fig S2C and D).

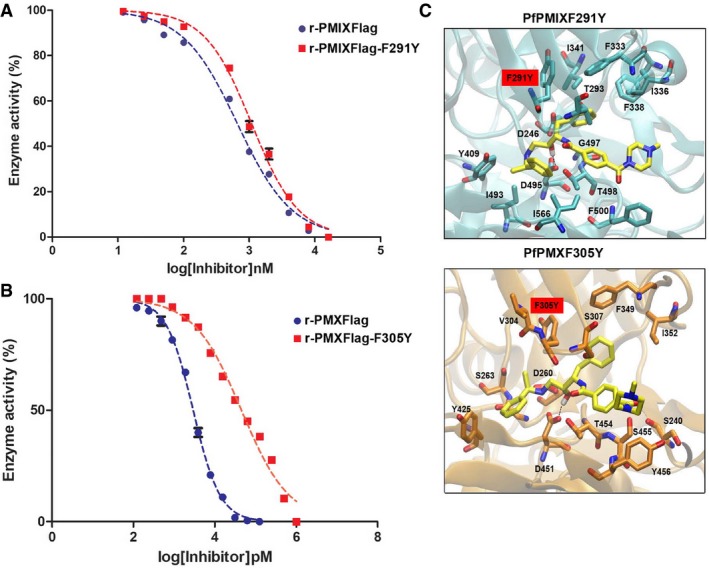

Importantly, while r‐PMIXFlag‐F291Y exhibits a modest increase in IC50 toward 49c as compared to r‐PMIXFlag (from ~650 nM to ~ 1.1 μM), r‐PMXFlag‐F305Y showed a ~15‐fold increase in IC50 toward 49c (from ~3 nM to ~45 nM; Fig 3A and B, Table 2). The insertion of a tyrosine at the corresponding residue (F291Y for PfPMIX and F305Y for PfPMX) does not reveal any particular modification to the binding orientation (Fig 3C). Since the hydroxyl group of the tyrosine is not hindering access to 49c, we might assume that the tyrosine influences the flexibility of the flap, causing a drop in binding affinity. Taken together, these results suggest that the F to Y flap mutation in both PfPMIX and PfPMX increases the susceptibility toward 49c.

Figure 3. PfPMIX and PfPMX phenylalanine to tyrosine mutants are more resistant to 49c.

- Dose–response curve comparing in vitro inhibition of r‐PMIXFlag (IC50: 0.6 ± 0.14 μM) or mutant r‐PMIXFlag‐F291Y (IC50: 1 ± 0.2 μM) activity by 49c. Data represent mean ± SEM, n = 2, from a representative experiment out of three independent assays.

- Dose–response curve comparing in vitro inhibition of r‐PMXFlag (IC50: 2.9 ± 0.3 nM) or mutant r‐PMXFlag‐F305Y (IC50: 45.2 ± 13 nM) activity by 49c. Data represent mean ± SEM, n = 2, from a representative experiment out of three independent assays.

- Molecular docking predictions of the possible effects in the binding mode of 49c (yellow) in the presence of the PfPMIXF291Y (upper panel in cyan) and PfPMXF305Y (lower panel in orange).

The phenylalanine residues in the flap and hydrophobic region of TgASP3 confer susceptibility to 49c

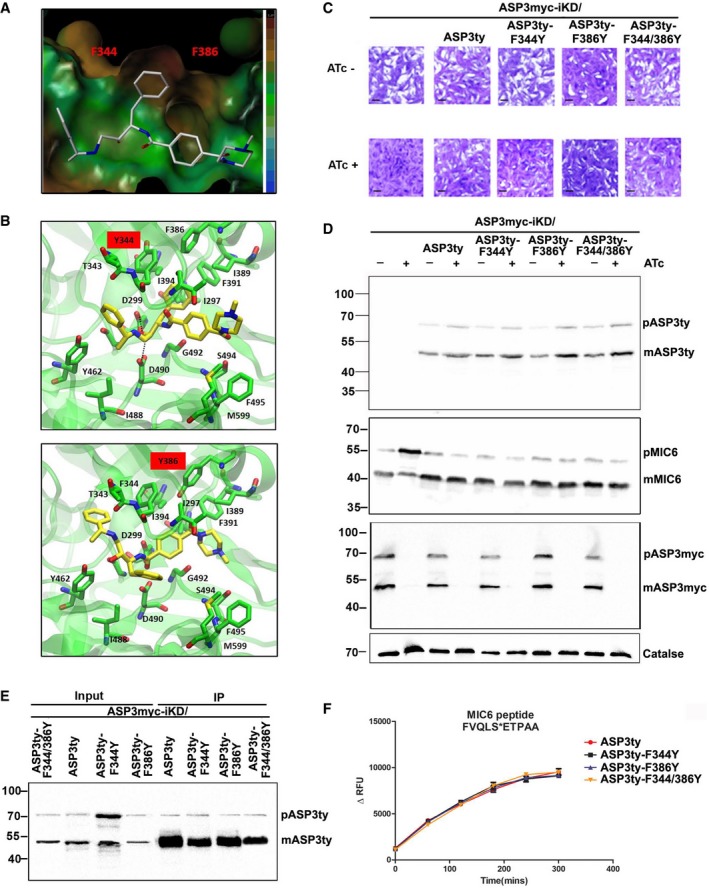

The docking of 49c on the TgASP3 model also uncovered a critical contribution of the conserved F344 and F386 residues in conferring susceptibility toward 49c (Fig 2B, upper panel). Similar to PfPMIX‐F291Y and PfPMX‐F305Y, the docking of 49c on the TgASP3‐F344Y mutant does not impose a dramatic change to the orientation of the binding mode, but causes a decrease in the predicted binding affinity (−5.5 kcal/mol) compared to the wild type (−7.1 kcal/mol; Fig 4B, upper panel). Moreover, F386, which forms the cavity together with other hydrophobic residues I297, I394, I389, F391, contributes to the high lipophilic potential, nicely accommodating the phenyl moiety of 49c (Fig 4A). In contrast, docking of 49c on ASP3‐Ty‐F386Y mutant shows a clear decrease in the predicted binding affinity (−4.2 kcal/mol). The hydroxyl group of the tyrosine forces outside of the cavity the aromatic ring of 49c, losing the interactions with the catalytic aspartic acids (Fig 4B, lower panel).

Figure 4. TgASP3 mutants are functional and not detrimental to parasite fitness.

- Lipophilic potential surface of the binding site of TgASP3 with compound 49c. The colored legend on the right shows the increasing of the lipophilicity from the blue color (bottom) to the brown (upper), highlighting the presence of a hydrophobic cavity between the two F344 and F386.

- Molecular docking predictions of the possible effects in the binding mode of 49c in the presence of the two mutants ASP3‐F344Y (upper panel) and ASP3‐F386Y (lower panel)

- Plaque assay was performed in parental stain ASP3myc‐iKD or parental strain complemented with wild‐type ASP3 (ASP3ty) or with mutant forms of ASP3 (ASP3ty‐F344Y, ASP3ty‐F386Y, ASP3ty‐F344Y/F386Y) in the UPRT locus. Knockdown of ASP3 in presence of ATc resulted in complete impairment of the lytic cycle, as assessed by plaque formation after 7 days, in parental ASP3myc‐iKD strain. Complementation with ASP3ty or with ASP3 mutants (ASP3ty‐F344Y, ASP3ty‐F386Y, and ASP3ty‐F344Y/F386Y) fully restored plaque formation. Scale bar represents 1 μm.

- Western blots analysis comparing lysate of parental ASP3myc‐iKD strain and complemented strain (ASP3myc‐iKD/ASP3ty, ASP3myc‐iKD/ASP3ty‐F344Y, ASP3myc‐iKD/ASP3ty‐F386Y, ASP3myc‐iKD/ASP3ty‐F344Y/F386Y) ± ATc for 48 h. Significant accumulation of TgMIC6 precursor form with reduction of mature form was observed in iKDASP3myc parasites by ASP3 depletion. Parasites complemented with either wild type or with the mutant form of ASP3 as well as untreated parasite showed proper processing of TgMIC6. Regulation of myc‐tagged inducible copy of ASP3 was shown by probing with α‐myc antibody. Catalase is used as loading control.

- Lysate of wild‐type ASP3ty and mutant form of ASP3 (ASP3ty‐F344Y, ASP3ty‐F386Y, ASP3ty‐F344Y/F386Y) stably expressed in the UPRT locus of ASP3myc‐iKD parasites was used to immunoprecipitate (IP) wild‐type or mutant forms of ASP3 using anti‐ty couple beads. Input and bound fractions were analyzed by Western blot and revealed the presence of precursor (pASP3ty) and mature form (mASP3ty) of ASP3ty.

- Immunoprecipitated wild‐type ASP3ty and its mutant forms (ASP3ty‐F344Y, ASP3ty‐F386Y, ASP3ty‐F344Y/F386Y) cleave TgMIC6 fluorogenic peptide (DABCYL‐G‐ FVQLS|ETPAA ‐G‐EDANS) with equal efficiency. Result represents mean ± SD, n = 3, of three independent experiments.

Source data are available online for this figure.

To validate the modeling‐based predictions of the TgASP3 susceptibility toward 49c, ASP3ty, ASP3ty‐F344Y, ASP3ty‐F386Y, and ASP3ty‐F344/386Y were expressed as second copies in WT parasites. The resulting strains were shown to produce comparable levels of ASP3ty and with the same localization as endogenous TgASP3. No defect in intracellular growth was observed either in the absence or in presence of 1 μM 49c (Fig EV4A–C).

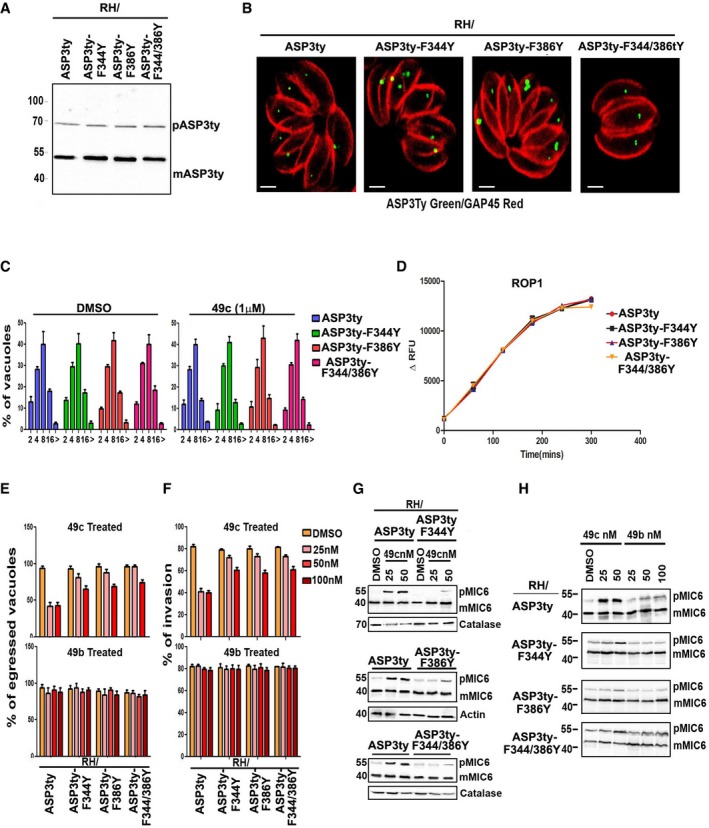

Figure EV4. Expression and localization of ASP3ty‐F344Y and ASP3ty‐F386Y.

- Western blot showing equivalent ectopic expression of wild‐type (ASP3ty) or mutant ASP3 (ASP3ty‐F344Y, ASP3ty‐F386Y, ASP3ty‐F344Y/F386Y) in RH parasites.

- Confocal microscopy reflecting identical localization of ASP3ty and mutants (ASP3ty‐F344Y, ASP3ty‐F386Y, ASP3ty‐F344Y/F386Y) ASP3 in RH parasites. Scale bar represents 2 μm.

- Intracellular growth assay was performed on parasites as in (B) in presence of DMSO (left panel) or 1 μM 49c (right panel). Parasites per vacuole were counted 24 h after inoculation of new host cell. No growth defect was observed in presence of 49c. Data are mean values ± SD from three biological independent experiments where 100 vacuoles were counted for each condition.

- Immunoprecipitated wild‐type ASP3ty and its mutant forms (ASP3ty‐F344Y, ASP3ty‐F386Y, ASP3ty‐F344Y/F386Y) cleave TgROP1 fluorogenic peptide (DABCYL‐G‐PSFVE|APVRG‐G‐EDANS) with equal efficiency. Results represent mean ± SD, n = 3, of three independent experiments.

- Induced egress assay showing a significant increase in egress in case of ASP3 mutant parasites (ASP3ty‐F344Y, ASP3ty‐F386Y, ASP3ty‐F344Y/F386Y) as compared to ASP3 wild‐type parasite (ASP3ty) expressed ectopically in RH in presence of 49c, optimal at 25 nM (upper panel) but not in presence of 49b (lower panel). DMSO treatment is used as a control. Parasites were pretreated with DMSO or 49c or 49b for 12 h before infecting fresh HFF monolayer and allowed to grow for another 30 h in presence of DMSO or drugs (49c, 49b) before inducing egress with 3 μM calcium ionophore (A23187) for 7 min. Data represent mean ± SD, n = 3, of three independent experiments.

- Invasion assay revealed increased invasion in case of ASP3 mutant parasites (ASP3ty‐F344Y, ASP3ty‐F386Y, ASP3ty‐F344Y/F386Y) as compared to ASP3 wild‐type parasite (ASP3ty) expressed ectopically in RH in presence of 49c, optimal at 25 nM (upper panel) but not in presence of 49b (lower panel). DMSO treatment is used as a control. Freshly egressed parasites (pretreated in presence of DMSO or drugs for 48 h) is allowed to invade HFF monolayers within 30 min of inoculation, and comprise means ± SD from at least 100 parasites counted in triplicate from three independent experiments.

- Western blot analysis revealed increased accumulation of unprocessed TgMIC6 (pMIC6) in case of ASP3ty parasites as compared to ASP3 mutants (ASP3ty‐F344Y, ASP3ty‐F386Y, ASP3ty‐F344Y/F386Y) expressed ectopically in RH parasites in presence of 49c. Profilin is used as loading control.

- Western blot showing TgMIC6 processing is not affected in ASP3 wild‐type ASP3ty or mutant parasites (ASP3ty‐F344Y, ASP3ty‐F386Y, ASP3ty‐F344Y/F386Y) expressed ectopically in RH parasites in presence of 49b.

Furthermore, when expressed in ASP3myc‐iKD, the mutants ASP3ty‐F344Y, ASP3ty‐F386Y, and ASP3ty‐F344/386Y successfully complemented the phenotypes caused by depletion of ASP3myc after 48 h anhydrotetracycline (ATc) treatment, as monitored by plaque assay (Fig 4C). Consistent with the rescue of the phenotypes, the processing of TgMIC6 was not affected by the introduction of the mutations in TgASP3 (Fig 4D). TgASP3 and the mutants were purified from the transgenic parasites by immunoaffinity (Fig 4E) and shown by cleavage assays to readily cleave TgMIC6 and TgROP1 fluorogenic peptides (Figs 4F and EV4D).

Increased expression of F344Y or F386Y mutants of TgASP3 enhances parasite resistance to 49c

When expressed in ASP3myc‐iKD, a second copy TgASP3 appeared to be produced at lower levels in the absence of ATc and accumulated in presence of ATc, suggesting that the parasites tolerate only a limited amount of ASP3 (Fig 5A, Appendix Fig S3A). The level of ASP3 mutants also fluctuated in ASP3myc‐iKD/ASP3ty‐F344Y and ASP3myc‐iKD/ASP3ty‐F386Y upon ATc treatment (Fig 5B, Appendix Fig S3B). Remarkably, the parasites expressing these mutants exhibited a significant increase in resistance (up to 100 nM 49c) in both invasion and egress assays (Fig 5C and D). Changes in susceptibility toward 49c but not toward 49b were observed also in RH parasites expressing ASP3ty‐F344Y, ASP3ty‐F386Y, and ASP3ty‐F344 by egress (Fig EV4E) and invasion assays (Fig EV4F). Consistent with this, the processing of TgMIC6 in ASP3myc‐iKD/F386Yty upon depletion of ASP3myc was more resistant to 49c inhibition (Fig 5E and F), although at higher concentrations of 49c (500 nM), the cleavage of TgMIC6 was blocked in both ASP3myc‐iKD/ASP3ty‐F386Y and ASP3myc‐iKD/ASP3ty (Fig 5C–F).

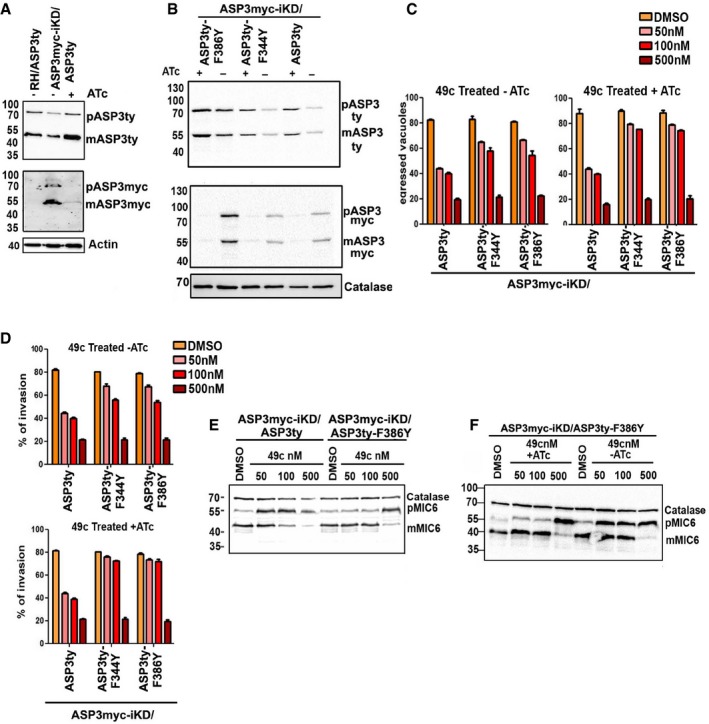

Figure 5. Overexpression of ASP3 mutants confers resistance to 49c.

- Western blot showing increased production of ASP3ty in case of ASP3myc‐iKD/ASP3ty parasites treated with ATc as compared to iKDASP3myc/ASP3ty in absence of ATc or ASP3ty expressed ectopically in RH parasites.

- Western blot showing increased production of ASP3ty in ASP3myc‐iKD/ASP3ty, ASP3myc‐iKD/ASP3ty‐F344Y, ASP3myc‐iKD/ASP3ty‐F386Y parasites in presence of ATc as compared to absence of ATc. Regulation of myc‐tagged inducible copy of ASP3 was shown by probing with α‐myc antibody. Catalase is used as loading control.

- Induced egress assay showing a significant increase in egress in case of ASP3 mutant parasites (ASP3myc‐iKD/ASP3ty‐F344Y, ASP3myc‐iKD/ASP3ty‐F386Y) as compared to ASP3myc‐iKD/ASP3ty parasite when treated with 49c (50 and 100 nM) both in absence (left panel) and in the presence of ATc (right panel). As compared to absence of ATc, presence of ATc resulted in significantly more egress in ASP3 mutant parasites (ASP3myc‐iKD/ASP3ty‐F344Y, ASP3myc‐iKD/ASP3ty‐F386Y). Data represent mean ± SD, n = 3, of three independent experiments.

- Invasion assay showing a significant increase in invasion in case of ASP3 mutant parasites (ASP3myc‐iKD/ASP3ty‐F344Y, ASP3myc‐iKD/ASP3ty‐F386Y) as compared to ASP3myc‐iKD/ASP3ty parasite when treated with 49c (50 and 100 nM) both in absence (upper panel) and in presence of ATc (lower panel). As compared to absence of ATc, presence of ATc resulted in significantly more invasions in ASP3 mutant parasites (ASP3myc‐iKD/ASP3ty‐F344Y, ASP3myc‐iKD/ASP3ty‐F386Y). Data represent mean ± SD, n = 3, from at least 100 parasites of three independent experiments.

- Western blot showing significant accumulation of unprocessed TgMIC6 (pMIC6) in ASP3myc‐KD/ASP3ty parasites as compared to ASP3myc‐iKD/F386Yty parasites when treated with 49c at least up to 100 nM concentration in presence of ATc.

- Western blot showing treatment of 49c (up to 100 nM) resulted in increased accumulation of unprocessed TgMIC6 (pMIC6) in absence of ATc in ASP3myc‐iKD/F386Yty parasites as compared to 49c treated (up to 100 nM) ASP3myc‐iKD/F386Yty parasite in presence of ATc.

Source data are available online for this figure.

Concordantly, the inhibition of TgMIC6 processing reflected the resistance of the mutants toward 49c while no change was observed with 49b in RH parasites (Fig EV4G and H). The increased resistance to 49c occurs at 25 nM but not at 50 nM or higher concentrations. The double ASP3ty‐F344/386Y mutant showed no additive or synergistic effect and was not investigated further.

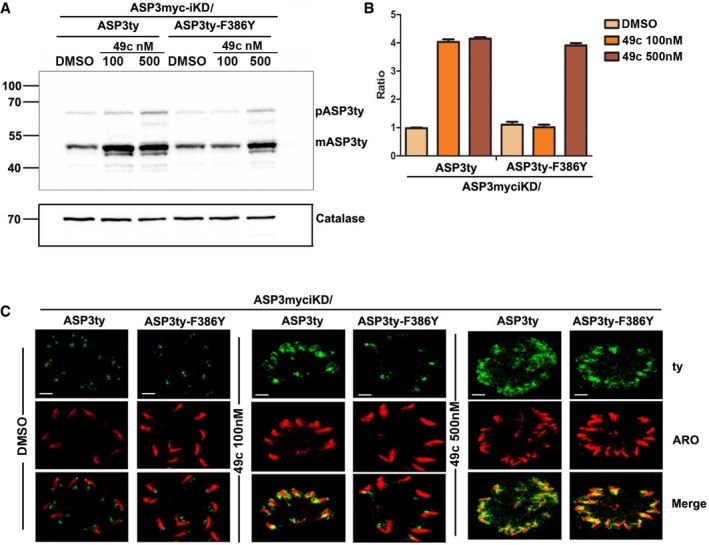

49c fosters the accumulation of ASP3 and to a lesser extent ASP3ty‐F386Y

As observed for PfPMIX and PfPMX in vitro, the treatment of parasites with 100 or 500 nM of 49c led to a significant accumulation of the mature form of TgASP3 (~55 kDa) by Western blot, suggesting that the protease is stabilized upon binding to the peptidomimetic inhibitor. Conversely, ASP3ty‐F386Y, which is predicted to poorly bind to 49c, was not stabilized to the same extent as WT TgASP3 in the presence of 100 nM 49c (Fig 6A). With 500 nM 49c, both ASP3ty and ASP3ty‐F386Y were stabilized. From the densitometry analysis, 49c caused a ~4‐fold increase in TgASP3 level and no increase in ASP3ty‐F386Y levels with respect to DMSO treatment (Fig 6B). 49c is also responsible for a perturbed ASP3 localization as observed by IFA on parasites treated with 100 nM 49c on TgASP3 and with 500 nM 49c on and ASP3ty‐F386Y (Fig 6C).

Figure 6. 49c stabilizes preferentially wt ASP3.

- Western blot revealed an increased accumulation of mature form of (mASP3ty, ˜55 kDa) wild‐type ASP3 (ASP3myc‐iKD/ASP3ty) as compared to mutant ASP3 (ASP3myc‐iKD/ASP3ty‐F344Y, ASP3myc‐iKD/ASP3ty‐F386Y) in presence of 100 and 500 nM 49c. DMSO is used as control for 49c. Catalase is used as loading control.

- Densitometry analysis of Western blot as in (A), quantifying fold decrease in accumulation of mature form of (mASP3ty, ˜55 kDa) in ASP3 mutant parasites (ASP3myc‐iKD/ASP3ty‐F386Y) as compared to wild type (ASP3myc‐iKD/ASP3ty). Data represent mean ± SD, for n = 2, from out of two independent assays.

- Confocal microscopy showing diffused localization of wild‐type ASP3 (ASP3myc‐iKD/ASP3ty) as compared to mutant ASP3 (ASP3myc‐iKD/ASP3ty‐F386Y) in presence of 100 nM 49c. At 500 nM concentration of 49c wild‐type and mutant ASP3 have similar diffused localization. DMSO is used as control. Scale bar represents 2 μm.

Source data are available online for this figure.

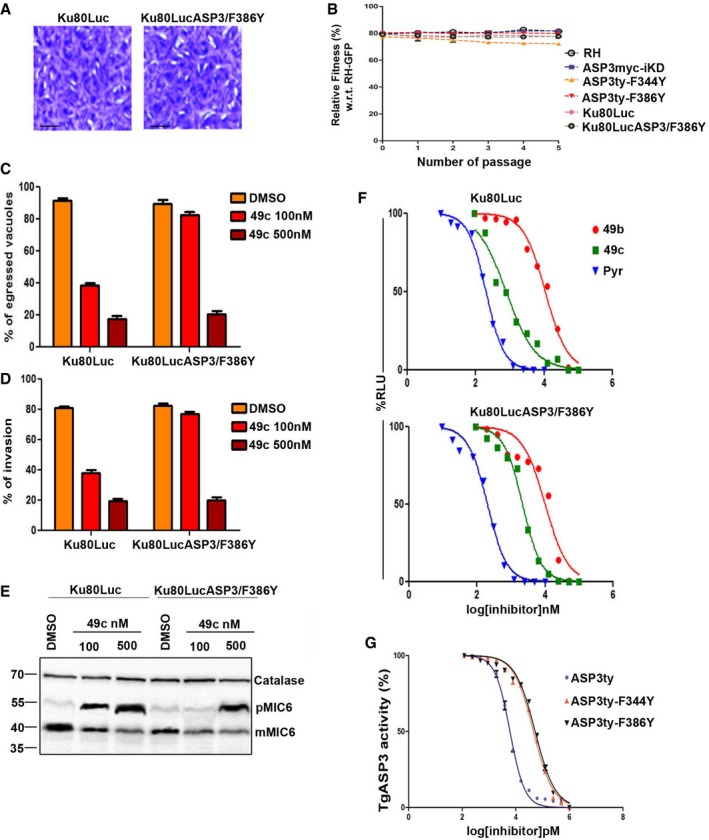

F386Y mutation in the TgASP3 locus confers resistance to 49c in vivo and in vitro

Introduction of mutations F344Y or F386Y or both does not result in detectable defects by plaque assay (Fig 4C). Given that F344Y and F386Y mutations confer resistance to 49c, we introduced a F386Y mutation with the assistance of CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing in the endogenous locus of TgASP3 in Ku80Luc parasites expressing luciferase (CBG99 Luc) to generate Ku80LucASP3/F386Y (Appendix Fig S4). Plaque assays confirmed that ASP3‐F386Y mutation at the endogenous locus was not detrimental to parasite propagation (Fig 7A). Furthermore, competition assay performed between GFP‐expressing RH, and RH, ASP3ty‐F344Y, ASP3ty‐F386Y, Ku80Luc, and Ku80LucASP3/F386Y, did not result in any significant loss of fitness (Fig 7B). Importantly, at 100 nM but not at 500 nM, 49c was ineffective in blocking egress or invasion of Ku80LucASP3/F386Y (Fig 7C and D), corroborated by the efficient processing of TgMIC6 (Fig 7E). Ku80/LucASP3‐F386Y exhibits an increased IC50 from ~700 nM to 2.1 μM compared to Ku80/Luc toward 49c with no change in susceptibility toward 49b (Fig 7F, Table 2). ASP3ty‐F344Y and ASP3ty‐F386Y were immunopurified from the transgenic parasites and compared to ASP3ty in an in vitro cleavage assay using the fluorogenic TgMIC6 peptide. While 49c inhibits ASP3ty with an IC50 of ~6 nM, it shows an increased IC50 of ~50 nM on ASP3ty‐F344Y and ASP3ty‐F386Y (Fig 7G, Table 2).

Figure 7. Resistance of ASP3 mutants toward 49c in vivo and in vitro .

- Plaque assay was performed in parental stain expressing luciferase (Ku80Luc) or parental strain with point mutation (F386Y) in endogenous locus of ASP3 Ku80LucASp3/F386Y. Scale bar represents 2 μm.

- Competition assay showing percentage of RH, ASP3myc‐iKD, ASP3ty‐F344Y, ASP3ty‐F386Y, Ku80Luc, and Ku80LucASp3/F386Y parasites with respect to GFP‐expressing parasites. The parasite ratios were determined over five passages and quantified by FACS. Data represent mean ± SD for n = 2, from out of three independent assay.

- Induced egress assay showing a significant increase in egress in case of ASP3 mutant Ku80LucASP3/F386Y parasites as compared to wild‐type parasite Ku80Luc parasite when treated with 100 nM 49c. 500 nM 49c inhibits induced egress of both Ku80Luc and Ku80LucASP3/F386Y parasite with equal efficiency. Data represent mean ± SD, n = 3, of three independent experiments.

- Invasion assay showing a significant increase in invasion in case of ASP3 mutant parasite (Ku80LucASP3/F386Y) as compared to Ku80Luc parasite when treated with 100 nM 49c. Treatment with 500 nM 49c did not resulted in any significant difference between Ku80Luc and Ku80LucASP3/F386Y parasites. Data represent mean ± SD, n = 3, from at least 100 parasites of three independent experiments.

- Western blot showing severely reduced accumulation of unprocessed TgMIC6 (pMIC6) in case of Ku80LucASP3/F386Y as compared to wild‐type Ku80Luc in presence of 100 nM 49c. Similar accumulation of pMIC6 was observed in case of Ku80Luc and Ku80LucASP3/F386Y parasites with 500 nM treatment of 49c. DMSO treatment is used as a control for 49c. Catalase is used as the loading control.

- Dose–response curve showing significant decrease in growth inhibition of Ku80LucASP3/F386Y (IC50: 2.24 ± 1.3 μM, lower panel) with respect to Ku80Luc (IC50: 0.77 ± 0.06 μM, upper panel) parasite in presence of 49c. No significant change in IC50 was observed in presence of 49b or pyrimethamine. Data represent mean ± SEM, n = 2, from a representative experiment out of three independent assays.

- Dose–response curve comparing in vitro inhibition of ASP3ty (IC50: 6 ± 2.3 nM) or mutant ASP3ty‐F344Y (IC50: 46 ± 10 nM) and ASP3ty‐F386Y (IC50: 52 ± 11 nM) ASP3 activity by 49c. Data represent mean ± SEM, n = 2, from a representative experiment out of three independent assays.

Source data are available online for this figure.

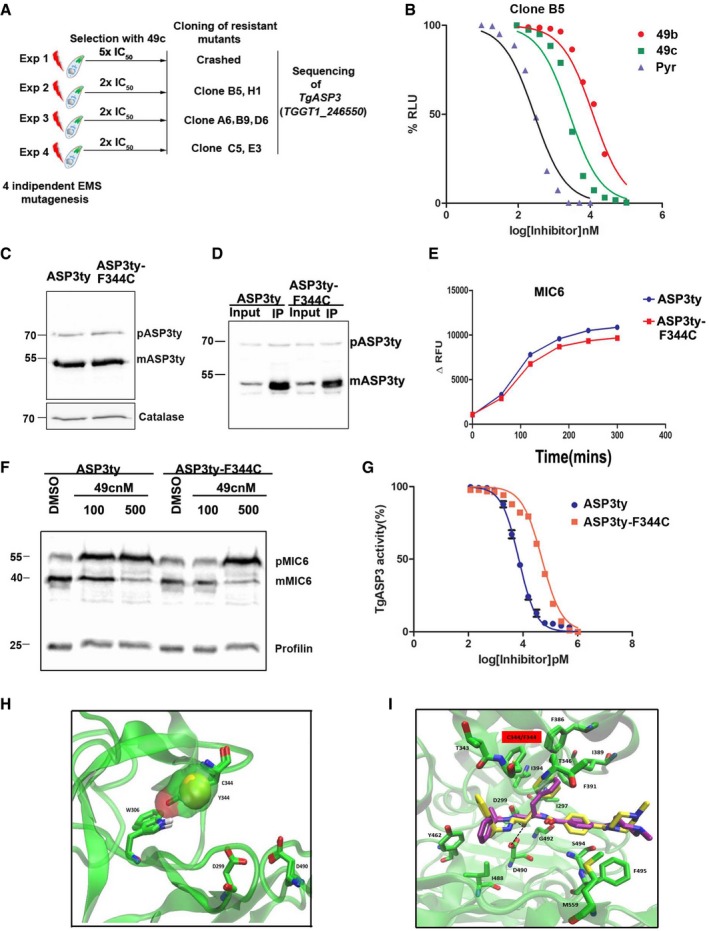

Chemically mutagenized parasites resistant to 49c exhibit a TgASP3‐F344C allele mutation

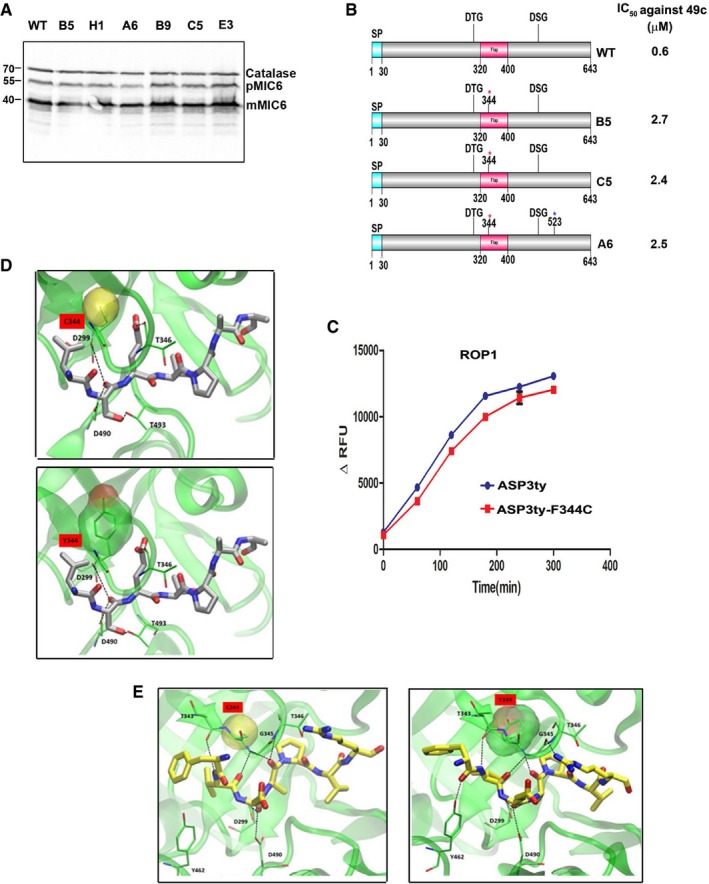

To determine whether other mutant ASP3 alleles could be more resistance to 49c, we selected for parasites that could grow in presence of 49c. First, RH Ku80Luc parasites were exposed to 5 μΜ (~ 5× IC50) and 10 μM (~10× IC50) of 49c; however, no resistant parasites emerged from the long‐term culture. Next, parasites were chemically mutagenized with 7 mM EMS prior to selection in the presence of 5 μΜ or 2 μΜ of 49c (Farrell et al, 2014). Resistant parasites were obtained from three independent mutagenesis experiments in presence of 2 μM of 49c (Fig 8A, Table 3). The parasites were cloned by limited dilution, and the TgASP3 allele was amplified, cloned, and sequenced. Six out of seven independent clones harbored a F344C mutation (either TTC‐TGT or TTC‐TGC) in TgASP3, while clone A6 had a second mutation T523I (Table 3). All these resistant mutants were shown to process TgMIC6 like the WT parental line in absence of 49c, indicating that the F344C mutation does not cause any aberrant defect in substrate recognition (Fig EV5A). Three independent resistant clones (B5, A6, and C5) showed an IC50 for 49c of ~2.5 μM which is comparable to Ku80LucASP3/F386Y and ~3‐fold higher than for WT parasites (Fig EV5B, Table 3). Analysis of mutant B5 established that susceptibility toward 49b and pyrimethamine was not altered (Fig 8B). As a further confirmation, F344C mutation was introduced in the endogenous locus of TgASP3 as described for ASP3‐F386Y in endogenously tagged ASP3ty parasites (Dogga et al, 2017). The ASP3ty‐F344Y mutant showed no defect in the lytic cycle, and ASP3ty‐F344Y is expressed at the same level as in wild‐type parasites in the absence of 49c (Fig 8C). ASP3ty‐F344C immunopurified from transgenic parasites (Fig 8D) was analyzed via the cleavage assay in absence of 49c (Figs 8E and EV5C). TgMIC6 and TgROP1 cleavages were not affected by the mutation (Figs 8E and EV5C), and ASP3ty‐F344C mutant is resistant to 100 nM 49c (Fig 8F). Altogether, ASP3ty‐F344C exhibits a resistance to 49c (~40 nM) comparable to ASP3ty‐F344Y and ASP3ty‐F386Y in the in vitro cleavage assay (Fig 8G, Table 2).

Figure 8. Isolation and characterization of ASP3‐F344C mutant allele in parasites resistant to 49c.

- Schematic representation of the strategy used to obtain Toxoplasma gondii resistant lines to 49c. The mutation in TgASP3 found in three independent experiments is shown.

- Dose–response curve representing growth inhibition of 49c‐resistant Toxoplasma gondii (B5) in presence of 49f, 49b, and pyrimethamine. Data represent mean ± SEM, n = 2, from a representative experiment out of three independent assays.

- Western blot showing equivalent ectopic expression of wild‐type (ASP3ty) or mutant ASP3 (ASP3ty‐F344C). Catalase is used as loading control.

- Lysate of wild‐type ASP3ty and mutant ASP3ty‐F344C parasites was used to immunoprecipitate (IP) wild‐type or mutant forms of ASP3 using anti‐ty antibodies coupled to beads. Input and bound fractions were analyzed by Western blot and revealed the presence of precursor (pASP3ty) and mature form (mASP3ty) of ASP3ty.

- Immunopurified ASP3ty and ASP3ty‐F344C cleaves TgMIC6 fluorogenic peptide (DABCYL‐G‐ FVQLS|ETPAA ‐G‐EDANS) with equal efficiency. Result represents mean ± SD, n = 3, of three independent experiments.

- Western blot showing severely reduced accumulation of unprocessed TgMIC6 (pMIC6) in case of ASP3ty‐F344C as compared to ASP3ty parasite in presence of 100 nM 49c. DMSO treatment is used as a control for 49c, and catalase is used as loading control.

- Dose–response curve comparing in vitro inhibition of ASP3ty (IC50: 7 ± 1.5 nM) or mutant ASP3ty‐F344C activity by 49c (IC50: 40 ± 8 nM). Data represent mean ± SEM, n = 2, from a representative experiment out of three independent assays.

- Overlap of the two mutant models ASP3‐F344C and ASP3‐F344Y. The picture shows the additional interaction that tyrosine and cysteine can make via the hydroxyl and thiol group, respectively, with the W306 and its amino moiety affecting the flexibility of the flap. The C344 and the Y344 residues are represented with the van der Waals surface to appreciate their real space occupancy.

- Overlap of the docking results of 49c obtained with the wt TgASP3 model (yellow) and the ASP3‐F344C mutant model (magenta). The main interacting residues are reported in licorice green, and the black dotted lines show the hydroxyl group interacting with the aspartic catalytic dyad.

Source data are available online for this figure.

Table 3.

Chemically mutagenized 49c‐resistant Toxoplasma gondii lines

| Experiment No. | Clone | Codon change in Flap | Amino acid change | Codon change others | Amino acid change | IC50 against 49c (μM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | B5 | TTC‐TGT | F344C | None | 2.7 | |

| H1 | TTC‐TGT | F344C | ND | |||

| 3 | A6 | TTC‐TGC | F344C | ACC‐ATC | T523I | 2.5 |

| B9 | TTC‐TGT | F344C | ND | |||

| D6 | TTC‐TGN | ND | ND | |||

| 4 | C5 | TTC‐TGT | F344C | None | 2.4 | |

| E3 | TTC‐TGT | F344C | None |

Table showing 49c‐resistant lines generated independently from three independent chemical mutagenized experiments. Codon change in TgASP3 with corresponding amino acid changes has been shown. IC50 of three independent clones against 49c was determined and represented in the table. ND, not determined.

Figure EV5. ASP3‐F344C and ASP3‐F344Y cleave ASP3 substrates.

- Western blot comparing MIC6 processing between RHCBG99 luciferase wild‐type parasites and 49c‐resistant mutant lines. Catalase is used as loading control.

- Schematic representation of TgASP3 in wild‐type and three independent 49c‐resistant mutant lines (B5, A6, C5) with their respective IC50 against 49c. The red asterisks indicate mutation in F344C and blue asterisk indicates mutation T523I.

- Immunoprecipitated wild‐type ASP3ty and its mutant ASP3ty‐F344C cleave TgROP1 fluorogenic peptide (DABCYL‐G‐PSFVE|APVRG‐G‐EDANS) with equal efficiency. Result represents mean ± SD, n = 3, of three independent experiments.

- Conserved binding mode of the TgMIC6 docked in the active site of the ASP3‐F344C (left panel) and ASP3‐F344Y (right panel). The peptide is reported in gray licorice style and the main interacting protein residues in green. The two mutated residues are presented with their van der Waals surface.

- Conserved binding mode of the TgROP1 docked in the active site of the ASP3‐F344C (left panel) and ASP3‐F344Y (right panel). The peptide is reported in yellow licorice style and the main interacting protein residues in green. The two mutated residues present their van der Waals surface.

To validate the modest level of resistance to 49c conferred by F344C, the mutant was examined structurally. The presence of a hydroxyl group in the F344Y or a thiol in the case of F344C allows hypothesizing the formation of a hydrogen bond with the tryptophan W306 (Fig 8H). Such an interaction influences the flexibility of the flap, stabilizing it toward the active site into a “closed conformation” that most probably hinders the entrance of 49c. But the docking of 49c against the ASP3‐F344C model is not predicted to disrupt binding when compared to the docking results of 49c on TgASP3 (Fig 8I). Therefore, we hypothesize that the binding of 49c will occur under thermodynamic penalty caused by the presence of the cysteine together with the less flexible loop. Thermodynamic penalty leads to a reduction of binding affinity and thus could account for the observed resistance (Seeliger et al, 2007). TgMIC6 and TgROP1 peptides binding in ASP3‐F344C and ASP‐F344Y models behave similarly to what has been observed for ASP3 WT (Fig EV5D and E).

Discussion

TgASP3 is implicated in invasion and egress from infected cells by functioning as a pre‐exocytosis maturase for several secreted rhoptry and microneme proteins. Similarly, the orthologous PfPMIX and PfPMX also cleave rhoptry and microneme proteins, respectively (Nasamu et al, 2017; Pino et al, 2017). Consequently, these aspartyl proteases must accommodate a wide range of substrates. TgROP1 is the only substrate known to be efficiently cleaved by all three proteases. Docking results of TgROP1 peptide showed a conserved “productive” binding mode among the three active sites. Conversely, the selective substrates PfRAP1 and PfSUB1 presented a bigger number of “productive” binding modes for the PfPMIX and PfPMX models, respectively. We speculate that single residue changes can contribute to the substrate specificity as we notice a threonine–serine conversion in the flap of the PfPMX. TgASP3 also cleaves TgSUB1 and TgRON13 by recognizing a similar motif “SFVE” or “SFTE” that precedes the glutamic acid cleavage site (Bradley & Boothroyd, 1999; Turetzky et al, 2010; Dogga et al, 2017). Herein, we have described a similar binding mode among the three substrates that share the common motif employing the homology model of TgASP3. TgMIC6, which is cleaved by ASP3 exclusively, does not harbor this common motif. Two specific point mutations at the P1 and position (VQLI|ETPA and VQLS|RTPA) were poorly cleaved in vitro, thus validating the predicted substrates’ binding mode.

Importantly, 49c inhibits TgASP3 and PfPMIX and PfPMX without impacting on other ASPs and PMs, highlighting a common structural feature between the members of this cluster that would immediately become relevant in the context of targeted drug design.

The superposition of the docking results of 49c on the three models TgASP3, PfPMIX, and PfPMX, unraveled a unique shared binding mode with an RMSD of around 1.57 Å. This pinpoints to a certain degree of similarity at the active site level, particularly in the flap region, which is known to be responsible for substrate and ligand accommodation (Asojo et al, 2003). 49b acts as a very poor inhibitor of TgASP3 (IC50 ~ 10 μM) compared to 49c. The proposed binding mode of 49c demonstrates that a stretched conformation is required for accommodation of the compound explaining why the substitution at the second position on the phenyl ring as present in 49b reduces inhibition efficacy. A structural comparison of TgASP5 versus TgASP3 model shows important differences at the binding site level, especially in the nature of the flap that defines the key features responsible for the specificity.

Sequence and structural analysis of the active site of the models revealed two conserved phenylalanine residues critical for the binding of 49c. The phenylalanine in the flap domain is conserved only in TgASP3, PfPMIX, and PfPMX and is replaced by a tyrosine residue in other apicomplexan aspartic proteases. In PfPMX, the flap mutant, F305Y, correlates with an increase in the IC50 values up to 15‐fold. Multiple attempts to generate P. falciparum lines resistant to 49c have failed probably because the compound targets PfPMIX and PfPMX simultaneously (Pino et al, 2017). Moreover, the models revealed that the presence of the Y in the hydrophobic cavity disrupts the accommodation of the hydrophobic phenyl ring of 49c. The relevance of the two phenylalanine residues was validated by the generation of various transgenic T. gondii parasites expressing ASP3ty‐F344Y and ASP3ty‐F386Y. All the mutants showed a comparable increase in resistance toward 49c without any synergistic effect. Noticeably, 49c treatment leads to an accumulation of WT PfPMIX and PfPMX in vitro as well as TgASP3 in vivo, suggesting a stabilization of the protein upon binding to 49c, which is not observed with the resistant mutants unless the concentration of the compound is raised to 500 nM.

Given the modest resistance observed through model‐derived mutations, we performed chemical mutagenesis on parasites followed by selection for 49c resistance. Remarkably, parasite lines resistant to 49c reproducibly harbored a phenylalanine to cysteine mutation in the ASP3 allele, precisely at the position of F344 in the flap as deduced by the model. The docking of 49c to the ASP3‐F344C model does not reveal any obvious steric clashes or hindrance with the compound in the presence of F344C mutation meaning that the mechanism of the resistance is more complex. Indeed, we noticed that an additional hydrogen bond can be formed between the cysteine residue (F344C) and the tryptophan 306 (W306) that could affect the flap flexibility and stiffen the opening and closing, accomplished by the protein to accommodate 49c. The same interaction is formed by the hydroxyl group of the tyrosine in the ASP3‐F344Y mutant. This allows the formation of a hydrogen‐bond network between the flap (W306 and Y344) and the active carboxyls, influencing the ligand binding kinetics, as reported for other proteases (Andreeva & Rumsh, 2001; Bedi et al, 2016). Interestingly, in the absence of 49c, ASP3‐F344C and ASP3‐F344Y show no significant difference in the processing TgMIC6 and TgROP1, underlining the selectivity of the resistance toward 49c. It is not yet clear why the F344C mutation is favored although it does not confer a significant increase in resistance, but it is plausible that F344C allows better accessibility to the substrates. Furthermore, although the bulky sulfur atom occupies almost the entire phenyl ring space, this mutant might also be more versatile in accommodating a broader range of substrates. These findings need to be further investigated in a more systematic way to unravel the mechanism that rules the flap flexibility and substrate specificity (Bedi et al, 2016).

Nowadays, limited drugs are available against the apicomplexan parasites, and all of them have limitations in efficacy and can cause serious side effects. Moreover, no safe vaccine is currently available to fully protect an organism against toxoplasmosis and malaria. The emergence of drug‐resistant parasites exacerbates the problem and highlights the needs for new classes of drugs targeting with high potency and selectivity biochemical pathways essential for the parasites. 49c is effective against T. gondii and Plasmodium species and validates TgASP3 and PfPMIX/PMX as attractive drug targets. Genetic and molecular evidence presented in this study identifies molecular basis for 49c specificity. The shared features between these three proteases and the structural determinants for selectivity grouped within the cavity should facilitate drug repurposing and rational design of improved orally available small molecule‐based drugs to target this cluster of essential apicomplexan aspartic proteases.

Materials and Methods

Homology modeling

The three homology models were prepared using Prime from Schrödinger package (Prime, Schrödinger, LLC, New York, NY, 2016). Based on the BLAST alignment, we selected the corresponding templates: human uropepsin (PDB code: 1FLH) for TgASP3, porcine pepsin (PDB code: 4PEP) for the PfPMIX, and pepsin (PDB code: 1PSA) for the PfPMX. The sequence identity between the query and template was 36, 27, and 33%, respectively, and the sequence similarity was 55, 51, and 52%. After building the models, loop refinement was considered for each model using the VSGB solvation model and OPLS3 force fields, and finally, the whole modeled structure was refined. The structures were then submitted to the model validation procedure using the QMEAN server (https://swissmodel.expasy.org/qmean/cgi/index.cgi) and the Ramachandran plot analysis (http://mordred.bioc.cam.ac.uk/~rapper/rampage.php).

Molecular docking

Protein preparation Wizard from the Schrödinger package was used to prepare the target structures (Madhavi Sastry et al, 2013). Bond orders were assigned and H‐bonds optimized using a pH of 4.5 matching the acidic experimental conditions. Further, in order to resolve putative steric clashes, an all‐atom restrained minimization with a maximum of 0.3 Å RMSD was performed. Biopolymer tool (Sybyl–X.2.1.1) was used to create the mutated residues for both the protein and peptides. The hydroxyl‐ethylamine compounds and the peptide TgROP1, PfRAP1, PfSUB1, TgROP13, and TgSUB1 were drawn in 2D and then geometrically converted into all possible 3D conformations considering the correct reported stereochemistry (2S, 3R) at an acidic pH of 4.5 (Ciana et al, 2013). The TgMIC6 peptide structure was obtained from the available crystal structure PDB code 2K2S. The ligand structures were prepared using the LigPrep tool for both the inhibitors and peptides. The Glide program (Halgren et al, 2004; Schrodinger Release 2016‐4: Glide, Schrödinger, LLC, New York, NY, 2016) was used for molecular docking. The grid box was generated after having performed the Site Map (Halgren, 2009) search, and it was centered to the active site where the two aspartic residues are located. Suitable peptide grids were generated for the substrate docking. Different scoring functions were considered for the evaluation of the docking results: The standard precision and extra precision were preferred for the calculation with the compounds, whereas the SP‐peptide mode was chosen for the docking of the substrates since this scoring function enhanced the number of retained poses improving the docking results (Tubert‐Brohman et al, 2013). After the docking calculations, the poses were energy minimized.

Expression and purification of recombinant PfPMIX and PfPMX

Codon remodeled genes encoding PfMIX and PfMX was cloned into the pFastBacNKI‐LIC‐3C‐2xstrepII‐Flag vector (NKI Protein facility) as described previously (Pino et al, 2017). The genes encoding PMIX and PMX flap mutants (r‐PMIXFlag‐F291Y and r‐PMXFlag‐F305Y) were generated by using Q5 site‐directed mutagenesis kit (NEB) using codon remodeled PMIX and PMX as templates and primers 5′‐GATATTATGTATGGCACCGGC‐3′, 5′‐CAGGTTGGTATGCGGTTC‐3′ for PMIX and 5′‐CATATTGTGTATGGCAGCGGC‐3′, 5′‐CAGGTTTTTTTCAATAAAGCTGC‐3′ for PMX, respectively, and then back‐cloned into pFastBacNKI‐LIC‐3C‐2xstrepII‐Flag vector encoding wild‐type PMIX and PMX. Sf21 cells (Gibco) were transfected using FuGene 6 (Promega) as described before (Buchs et al, 2009). After two rounds of virus amplification, Sf21 cells were infected with the recombinant viruses and harvested 2–4 days post‐infection. Cells were resuspended in PBS supplemented with 2.5% glycerol (PBS‐G), lysed with sonication, and clarified by centrifugation at 38,000 g. Recombinant proteases were captured with a Strep‐Tactin XT superflow cartridge (IBA GmbH), washed with PBS‐G+ 0.5 M NaCl, and eluted 50 mM d‐biotin as described previously (Pino et al, 2017).

Toxoplasma gondii, host cell, and bacteria culture

Toxoplasma gondii tachyzoites parental and modified strains were grown in confluent monolayers of human foreskin fibroblasts (HFFs) in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM, Gibco) supplemented with 5% fetal calf serum (FCS), 2 mM l‐glutamine, and 25 μg/ml gentamicin. Conditional expression of the different constructs was performed with 1 μg/ml anhydrotetracycline (ATc) for the Tet‐inducible system (Meissner et al, 2002b). E. coli XL‐10 Gold chemically competent bacteria were used for all recombinant DNA experiments.

Parasite transfection and selection of stable transgenic parasites

Transfection of parasites was performed as previously reported (Soldati & Boothroyd, 1993). The transgenic parasites were selected with mycophenolic acid and xanthine for HXGPRT selection (Donald et al, 1996) and FUDR (Shen et al, 2014). Clones for all stably transformed strains were obtained by limited dilution and checked by IFA and Western blot.

Plasmids with wild‐type TgASP3 (ASP3ty; Dogga et al, 2017) or with mutation in flap of TgASP3 (ASP3ty‐F344Y, ASP3ty‐F386Y) was generated using Q5 site‐directed mutagenesis kit (NEB) and primers (5′‐GACATTACATACGGGACAGGA C‐3′ and 5′‐GTCCTGTCCCGTATGTAATGTC‐3′ and 5′‐CGGAAACATCTACAAGACTATC‐3′ and 5′‐GATAGTCTTGTAGATGTTTCCG‐3′, respectively). The RH strain was transfected with 40 μg of pT8ASPty‐HX or pT8ASP3ty‐F344Y‐HX or pT8ASP3ty‐F386Y‐HX or pT8ASP3ty‐F344/386Y‐HX (generated by digesting pT8ASP3ty‐F386Y‐HX with BstXI/NsiI and then subcloning into digested pT8ASP3ty‐F344Y‐HX vector) linearized with NotI. iKDASP3‐Myc/Ble strain (Dogga et al, 2017) was transfected with 5′UPRT‐pT8ASP3ty‐3′UPRT (Dogga et al, 2017) or 5′UPRT‐pT8ASP3ty‐F344Y‐3′UPRT or 5′UPRT‐pT8ASP3ty‐F386Y‐3′UPRT or 5′UPRT‐pT8ASP3ty‐F344/386Y‐3′UPRT (generated by digesting pT8ASP3ty‐F344Y‐HX or pT8ASP3ty‐F386Y‐HX or pT8ASP3ty‐F344/386Y‐HX plasmid with ApaI/NsiI and subcloned into digested 5′UPRT‐pT8ASP3ty‐3′UPRT vector) linearized with SpeI/NotI. Ku80 luciferase strain was generated by transfecting with circular 60 μg pT8CBG99‐luciferase‐HX plasmid (Dogga et al, 2017). This Ku80 luciferase strain was transfected with a Cas9‐YFP/CRISPR guide (guideF386, GAGATGTTTCCGTGCATGTTG) targeting the third exon of endogenous TgASP3 (generated using Q5 site‐directed mutagenesis kit (NEB) along with 40 μg of TgASP3 wild‐type or TgASP3‐F386Y synthetic oligonucleotides to generate Ku80Luc or Ku80LucASP3F38Y strain, respectively. Similarly, ASP3ty‐F344C strain was generated by transfecting with a Cas9‐YFP/CRISPR guide (guideF344, GTTCGGGACAGGACGTATTGA) along with TgASP3‐F344C synthetic oligonucleotides in KI‐ASP3ty parasites (Dogga et al, 2017). Transfected parasites were cloned by FACS sorting the green fluorescent parasites into 96‐well plates, 48 h post‐transfection.

Immunofluorescence assay and confocal microscopy

In this study, the following antibodies were used for IFA and Western blot: rabbit anti‐GAP45, mAb anti‐myc myc supernatant, mAb anti‐ty supernatant, rabbit antiprofilin, rabbit anticatalase, rabbit anti‐TgMIC6 (Reiss et al, 2001), rabbit anti‐ARO (Muller & Hemphill, 2013). Infected‐HFF monolayers on coverslips were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA)/0.05% glutaraldehyde (GA) for 10 min, prior to quenching with 0.1M glycine/PBS. Cells were permeabilized with 0.2% Triton/PBS and blocked with 2% BSA/0.2% Triton/PBS, probed with primary antibodies diluted in 2% BSA/0.2% Triton/PBS for 1 hr followed by 0.2% Triton/PBS wash (three times). Cells were then incubated with secondary antibodies (Alexa488‐ or Alexa594‐conjugated goat anti‐mouse or goat anti‐rabbit IgGs) for 1 h. Parasite and HFF nuclei were stained with DAPI (4′,6‐diamidino‐2‐phenylindole; 50 μg/ml in PBS), and coverslips were mounted on Fluoromount G (Southern Biotech) on glass slides and stored at 4°C in the dark. Images were recorded on the LSM700 confocal microscope (Zeiss) at the Bioimaging core facility of the Faculty of Medicine, University of Geneva. Final image analysis and processing were done with ImageJ.

Antibodies and Western blot analysis

Following antibodies were used in this study, rabbit anti‐GAP45, mAb anti‐myc (9E10), mAb anti‐ty1 (BB2), rabbit anti‐MIC6 (Reiss et al, 2001), rabbit anti‐Profilin, rabbit anticatalase, ARO (Muller & Hemphill, 2013), SAG1 (gift from Dr J‐F Dubremetz).

For the Western blot, freshly egressed parasites were pelleted by centrifugation, washed in PBS, and subjected to SDS–PAGE under reducing conditions. Proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose membrane, and immunoblot analysis was performed. Primary and secondary antibodies, conjugated goat anti‐rabbit/mouse (Sigma), are diluted in 5% milk/0.05% Tween/PBS.

Plaque assays

Freshly egressed parasites were inoculated on a confluent monolayer of HFFs and grown for 7 with or without anhydrotetracycline (ATc). Cells were fixed with PFA/GA followed by staining with crystal violet for 5 mins as previously described (Plattner & Soldati‐Favre, 2008).

Intracellular growth assay

HFF were inoculated with freshly egressed parasites in presence of DMSO or 49c (1 μM). Invaded parasites were allowed to grow for 24 h prior to fixation with 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA). IFA was performed using α‐GAP45 Abs, and the number of parasites per vacuole was counted from a total of 100 vacuoles per condition. The data shown are mean values and SDs from three independent experiments.

Induced egress assay

Parasites were grown in 6‐well plate with a 12‐h pretreatment with DMSO or 49c (25, 50, 100, 500 nM). Freshly egressed tachyzoites were added to a new monolayer of HFF and grown for 30 h in presence of DMSO or different concentration of 49c. The infected HFF were then incubated for 5 min at 37°C with DMEM containing either 3 μM of the Ca2+ ionophore A23187 (from Streptomyces chartreusensis, Calbiochem) or DMSO. Host cells were fixed with PFA/GA, and IFA using a‐GAP45 Abs was performed. One hundred vacuoles were counted per strain and per condition, and the number of lysed vacuoles, which are morphologically distinct from intact ones, was scored. The data shown are mean values from three independent experiments.

Invasion assay red/green

The red/green invasion assay was as described previously (Dogga et al, 2017). Briefly, parasites were treated either with DMSO or 49c (25, 50, 100, 500 nM) in 6‐well plates seeded with HFF monolayers for approximately for 36 h. Freshly egressed parasites which were released after complete lysis of this 6‐well plate were inoculated on 24‐well plates with HFF monolayers and were allowed to settle for 15 min at 4°C. Invasion was allowed to take place for 30 min at 37°C prior to fixation using PFA/Glu. Non‐permeabilizing IFA was performed by staining extracellular parasites with α‐SAG1 Abs, followed by permeabilization with PBS/Triton and subsequent staining of invaded parasites with α‐GAP45 Abs. For each experiment, at least 100 parasites were counted. The assay was performed three times independently.

Competition assay

RH, ASP3myc‐iKD, ASP3ty‐F344Y, ASP3ty‐F386Y, Ku80Luc, and Ku80LucASP3F386Y parasites were mixed with GFP‐expressing parasites. The parasite ratios were determined over five passages and quantified by FACS. Parasites were labeled with Hoechst prior to FACS counting of 5,000 parasites. Data are presented as mean values ± SD from two independent experiments.

Purification of TgASP3

Wild‐type or mutant form (F344Y, F386Y, and F344/386Y) of ty tagged T. gondii ASP3 was immunopurified from transgenic parasite lysate as described previously (Boddey et al, 2010). Briefly, freshly released tachyzoites were harvested, washed in PBS, and lysed in PBS containing 1% Triton X‐100 and protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche) with repeated freeze and thaw followed by sonication. Centrifugation of lysate was performed at 21,460 g; 30 min at 4°C, the supernatant was subjected to IP using mouse αTy antibody and proteases bound to agarose were prepared by incubating αty‐agarose in parasite lysate, for 2 h at 4°C, followed by extensive wash in 1% Triton X‐100/PBS and stored in PBS as described previously (Dogga et al, 2017).

Toxoplasma gondii random mutagenesis

RHCBG99 luciferase parasites were chemically mutagenized as described previously (Coleman & Gubbels, 2012; Farrell et al, 2014). Briefly, ~107 tachyzoites growing intracellularly in HFF cells (18–25 h post‐infection) were incubated at 37°C for 4 h in 0.1% FBS DMEM growth medium containing either 7 mM ethyl methanesulfonate (EMS, Sigma, diluted from a 1 M stock solution in DMSO) or with DMSO vehicle controls (Farrell et al, 2014). After exposure to mutagen, parasites were washed three times with PBS, and the mutagenized population was allowed to recover in the absence of drug for 3–5 days. Released tachyzoites were then inoculated into fresh cell monolayers in medium containing 2 μM or 5 μM 49c and incubated until viable extracellular tachyzoites emerged 7–10 days later. Surviving parasites were passaged once more under continued 49c treatment and cloned by limiting dilution. Seven cloned mutants were isolated from four independent mutagenesis experiments.

In vitro measurement of IC50

Toxoplasma gondii tachyzoites expressing luciferase (Ku80 luciferase/WT or Ku80 luciferase/F386Y or RHCBG99 luciferase; 200 parasites) were added in HFF coated 96‐well plate harboring 105 cells per well. Inhibitors (49c or 49b or 49f), along with pyrimethamine (used as a positive control in this experiment (Donald et al, 1996), were diluted in supplemented DMEM and added to the monolayers at various concentrations in triplicates along with DMSO‐treated control for each set. The assay was performed in a 100 μl final volume. The plates were incubated for 96 h at 37°C, cells were washed once with PBS, and lysis was performed in the wells with 100 μl lysis buffer (Dogga et al, 2017). Uninfected host cells were also lysed as negative control. 20 μl of lysate was added to 96‐well MicroliteTM TCT plate and incubated with 20 μl of Luciferase substrate solution (Dogga et al, 2017), and reading was taken immediately. Growth of T. gondii was evaluated by measurement of relative luciferase unit (RLU) in the SynergyH1 multi‐well plate reader (BioTek). Assays were performed in triplicates for each drug, and IC50 (50% reduction in luciferase activity as compared no drug‐treated control) was determined by plotting luminescence against the drug concentrations from analysis of dose–response curve using Prism 5.0 (GraphPad, San Diego, CA).

In vitro cleavage assays

Protease cleavage assays were performed with purified wild‐type or mutant recombinant PMIX and PMX produced from insect cells in presence of 20 μM of synthetic TgROP1 (DABCYL‐G‐PSFVEAPVRG‐G‐EDANS) peptide substrate (Pino et al, 2017). TgASP3 cleavage assays used ASP3ty or with ASP3 mutants (F344Yty, F386Yty, and F344Y/F386Yty, F344Cty) immunopurified from parasite lysates using mouse αTy antibody, as described previously (Boddey et al, 2010; Coffey et al, 2015; Dogga et al, 2017). The assay comprised of approximately 400–500 ng of ASP3ty or ASP3ty‐F344Y or ASP3ty‐F386Y or ASP3ty‐F344/386Y‐agarose in digestion buffer (25 mM Tris HCl, 25 mM MES, pH 5.5; different pH ranges were tested and pH 5.5 was optimal), 20 μM of synthetic peptide substrate (ThermoFisher scientific, > 98% purity) TgMIC6 wild‐type sequence: DABCYL‐G‐FVQLSETPAA‐G‐EDANS or TgMIC6 mutant peptides (DABCYL‐G‐VQLIETPA‐G‐EDANS, DABCYL‐G‐VQLSRTPA‐G‐EDANS) or TgROP1(DABCYL‐G‐PSFVEAPVRG‐G‐EDANS) peptide in 100 μl of total volume. Samples were incubated at 37°C for 5 h and processing measured as fluorescence using a SynergyH1 multi‐well plate reader (BioTek) excited at 340 nm and reading emissions at 490 nm. Samples were gently shaken during incubation to disperse protease agarose. Change in relative fluorescence unit (ΔRFU) was measured for each time point (0, 60, 120, 180, 240, 300 mins) by subtracting RFU from blank (without enzyme) for each time point. Inhibition of proteases by compounds 49c and 49b were performed in exact similar manner as mentioned previously by performing cleavage of TgMIC6 peptide with wild‐type sequence (DABCYL‐G‐FVQLSETPAA‐G‐EDANS) in presence of increasing concentration of 49c. The results were plotted using Prism 5.0 (GraphPad, San Diego, CA).

Author contributions

BM designed and performed the experiments related to expression, characterization, and biochemical assays related to TgASP3, PfPMIX‐X, and the generation and characterization of transgenic parasites; FT designed and performed the molecular modeling and docking experiments; BM and FT analyzed the data; J‐BM purified TgASP3 and JV produced and purified Plasmepsins; IK supervised JV and critically read the manuscript; DS‐F and LS supervised the project and the experiments; BM, FT, DS‐F, and LS wrote the manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Supporting information

Appendix

Expanded View Figures PDF

Source Data for Appendix

Review Process File

Source Data for Figure 4

Source Data for Figure 5

Source Data for Figure 6

Source Data for Figure 7

Source Data for Figure 8

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Gianpaolo Chiriano for providing assistance with the modeling at the beginning of the project and Aarti Krishna for critical reading of the manuscript. This work was supported primarily by Carigest SA (DS‐F and LS) and the Swiss National Science Foundation (FN3100A0‐116722 and IZLIZ3‐156825). JV work was supported by the Academy of Finland (292718 to IK). DS‐F is an HHMI senior international research scholar. BM is recipient of a long‐term EMBO Fellowship.

The EMBO Journal (2018) 37: e98047

Contributor Information

Leonardo Scapozza, Email: leonardo.scapozza@unige.ch.

Dominique Soldati‐Favre, Email: dominique.soldati-favre@unige.ch.

References

- Andreeva NS, Rumsh LD (2001) Analysis of crystal structures of aspartic proteinases: on the role of amino acid residues adjacent to the catalytic site of pepsin‐like enzymes. Protein Sci 10: 2439–2450 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews KT, Fairlie DP, Madala PK, Ray J, Wyatt DM, Hilton PM, Melville LA, Beattie L, Gardiner DL, Reid RC, Stoermer MJ, Skinner‐Adams T, Berry C, McCarthy JS (2006) Potencies of human immunodeficiency virus protease inhibitors in vitro against Plasmodium falciparum and in vivo against murine malaria. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 50: 639–648 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asojo OA, Gulnik SV, Afonina E, Yu B, Ellman JA, Haque TS, Silva AM (2003) Novel uncomplexed and complexed structures of plasmepsin II, an aspartic protease from Plasmodium falciparum . J Mol Biol 327: 173–181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]