Abstract

Background

International migration across Europe is increasing. High rates of net migration may be expected to increase pressure on healthcare services, including emergency services. However, the extent to which immigration creates additional pressure on emergency departments (EDs) is widely debated. This review synthesizes the evidence relating to international migrants’ use of EDs in European Economic Area (EEA) countries as compared with that of non-migrants.

Methods

MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL, The Cochrane Library and The Web of Science were searched for the years 2000–16. Studies reporting on ED service utilization by international immigrants, as compared with non-migrants, were eligible for inclusion. Included studies were restricted to those conducted in EEA countries and English language publications only.

Results

Twenty-two articles (from six host countries) were included. Thirteen of 18 articles reported higher volume of ED service use by immigrants, or some immigrant sub-groups. Migrants were seen to be significantly more likely to present to the ED during unsocial hours and more likely than non-migrants to use the ED for low-acuity presentations. Differences in presenting conditions were seen in 4/7 articles; notably a higher rate of obstetric and gynaecology presentations among migrant women.

Conclusions

The principal finding of this review is that migrants utilize the ED more, and differently, to the native populations in EEA countries. The higher use of the ED for low-acuity presentations and the use of the ED during unsocial hours suggest that barriers to primary healthcare may be driving the higher use of these emergency services although further research is needed.

Introduction

The demand for emergency care in Europe has increased over the last few decades creating additional pressure on emergency departments (EDs).1 This increased demand has coincided with rapid population change; in particular, high rates of international immigration into, and across, Europe. Higher rates of net migration and sustained levels of population growth may be expected to increase pressure on public services, although the extent to which international immigration is creating additional pressure on EDs is a topic of some debate. Some studies suggest that EDs are used more, and differently, by new migrants which may be as a result of unfamiliarity with the healthcare systems and difficulties accessing primary healthcare (PHC) services.2,3 However, little consistent evidence exists to quantify migrants’ use of the ED or to analyse its origins. Furthermore, little is known about the emergency and urgent healthcare systems preparedness and responsiveness in dealing with the healthcare needs of migrant patients.

Migrants, like all citizens, require health and social services and one of the greatest challenges facing host countries lies in ensuring that healthcare services are equitable, accessible and able to meet the needs of diverse populations. Migrant populations are often healthier than the host population on arrival,4 this phenomenon is often referred to as the ‘healthy (im)migrant effect’5 and so generally do not have high healthcare needs. However, ‘migrants’ are a very diverse group and some migrant patients face particularly vulnerable circumstances (e.g. refugees and asylum seekers) or they may be undocumented and this may affect their health-seeking practices. These factors, and others, make the process of establishing patterns and underlying reasons for migrants’ use of ED and other healthcare services particularly challenging. The unique nature of the European Union (EU), allowing free movement of member citizens between countries, means that many challenges relating to population change are shared across the member states.6 This is particularly acute in the contemporary context of conflict and instability around European borders. Migrant health, and the need to address any particular healthcare needs of migrants is increasingly being recognized.4 However, without adequate monitoring procedures, many countries in Europe are unable to measure the healthcare needs and practices of migrants and it is difficult to establish the extent to which health services are accessible to migrant patients.4 It is clear that a greater understanding of the healthcare needs of migrants and how they utilize emergency healthcare services, including EDs, in Europe is needed if we are to be able to support and improve migrant health, manage healthcare costs and healthcare resources, and promote social and economic development.7

Differences in healthcare use between migrants and non-migrants have been well documented (e.g. Refs 6 and 8) although the results from these studies set in differing contexts, using differing methodologies and including differing migrant populations show a diverging picture of both higher, lower and equal levels of healthcare services use. Analysis of differences in the use of emergency services, in particular, is lacking. A review looking at the use of somatic health services by migrants in Europe identified six articles which reported on emergency room use.6 However, the findings from these studies differ and drawing conclusions about migrants’ use of EDs, as compared with that of non-migrants, are difficult. Furthermore, this review focused only on volume of service utilization at an emergency room; understanding how, when and for what clinical reasons migrants use EDs and whether this differs for non-migrants remains unknown.

Our review aimed to identify, and synthesize, available literature relating to international migrants’ utilization of EDs in European Economic Area (EEA) countries as compared with that of non-migrants. The research question for this review was

‘Are there differences in international migrants’ use of emergency departments as compared to that of non-migrants in European Economic Area (EEA) countries?’

Methods

The methods for undertaking this review were pre-specified and the protocol registered on PROSPERO (registration number: CRD42016037650).

Information sources and searches

Electronic databases of MEDLINE (via Ovid), EMBASE (via Ovid), CINAHL (EBSCO), The Cochrane Library and The Web of Science were searched in January 2016 using a pre-determined search strategy for the years 2000–16 (current). Grey literature was searched using OpenGrey (March 2016). To enhance this search, supplementary search methods were employed, including: citation searching of key references, reference list checking of included articles and relevant systematic reviews, as well as hand-searching of key journals (BMC Health Services Research, European Journal of Public Health and Social Science and Medicine) for the 6 months prior to the start of the database searches. The search was restricted to English language publications.

A highly sensitive search strategy using keywords and exploded MeSH terms was developed for Medline (available as Supplementary Material) and translated for the other databases.

Eligibility criteria

Studies that report on ED utilization by international immigrants were eligible for inclusion. To be eligible for inclusion, studies needed to report a definition of a ‘migrant’ that included: country of birth, citizenship or participant nationality. Studies were excluded if patients were classified by ‘ethnicity’ or in cases where ethnicity was used as a proxy for migrant status. The use of EDs by migrant adults or migrant parents for their children, irrespective of place of birth of the child, was eligible for inclusion. Studies reporting utilization of EDs by patients for specific conditions were excluded. All included studies had a comparison group of non-migrants or a population considered similar to the native population. Furthermore, the comparison group originated from the same source population as the migrant group.

We included studies that reported at least one outcome relating to: volume of ED service use; time of ED utilization; type of clinical presentation and ‘appropriateness’ of ED use (as defined by the study).

Studies set in emergency or acute care settings that are not integrated in a hospital setting, including emergency primary care services, or studies that report on use of these services (e.g. population surveys), were not eligible for inclusion. Finally, included studies were restricted to those conducted in EEA countries (including Switzerland).

Study selection

The initial database search, title and abstract screen and the full text review of articles were conducted by a single author (S.H.C.). A second reviewer (E.S.) reviewed articles that were initially included at the title and abstract screen but were excluded at full paper review. Where there was uncertainty or disagreement between the two reviewers this was resolved by discussion with a third reviewer (S.M.).

Data extraction and quality assessment

A single author (S.H.C.) extracted data onto a standardized and piloted data extraction form, and a random sample of 10% was extracted by a second author (E.S.). The following data were extracted for each paper: author, year of publication, host country, study design, sample size, study population, definition of ‘migrant’, definition of ‘control’, outcomes, as well as potential confounders adjusted for in analysis. The full list of data items extracted is available on request.

Quality assessment for the articles included in this review was undertaken using The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence’s tool (adapted for this review): ‘Quality appraisal checklist- quantitative studies reporting correlations and associations’.9 Using this checklist the external and internal validity were assessed, according to key aspects of study design, to determine the overall study quality. Quality assessment was undertaken by S.H.C. and a second reviewer (E.S.) checked the quality assessment on a random sample of 20% of the included articles. Studies were not excluded from the review based on their quality, but study quality was considered in synthesizing the results and greater emphasis placed on the results of studies appraised to have higher internal and external validity. The final list of included studies was agreed by consensus with all study authors (S.H.C., E.S., S.M.)

Data synthesis and analysis

Study data were tabulated according to utilization of health services by the review outcomes of interest. Statistical meta-analysis of the included studies was not deemed to be appropriate due to the considerable heterogeneity between the studies. Using the data extracted from the studies, results of the quality assessment along with information provided in the text of the articles, a narrative synthesis of the available evidence was conducted.

Results

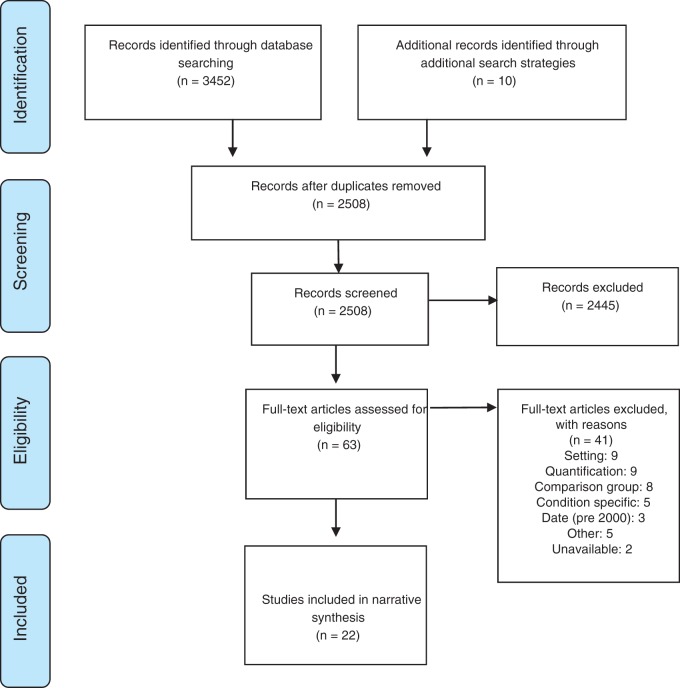

The database searches yielded 3452 records, an additional 10 were identified though the supplementary search strategies. 2445 records were excluded during title and abstract screen and the full-texts of 63 articles were reviewed. Twenty-two articles met the inclusion criteria and are included in this review (figure 1).

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram of results of literature identification, eligibility and inclusion

Included studies

A summary of the main characteristics of the included studies are shown in table 1 (more detail is available in Supplementary tables S3 and S4). Papers were identified from six host countries with the majority of the papers reporting on studies conducted in Spain. Five of these used data from the Spanish Health Surveys; either from the 2003 survey, the 2006 survey or a combination of data from both surveys.10–14 Just less than a third (7/22) of studies were conducted at a national level, while 15/22 were conducted at local or regional level. Fourteen studies were conducted within an ED setting, while the remaining eight report on patients’ self-reported ED use.

Table 1.

Summary of main study characteristics and key findings by review outcomes of interest

| Volume of ED utilization | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reference and host country | Study design (sampling method) | Sample and number of migrants | Migrant definition | Overall quality assessment rating for internal validity (IV) and external validity (EV) | Key findings | |

| IV | EV | |||||

| Ballotari et al. (2013), Italy28 | Cohort (Record linkage of three databases) | Healthy singleton live births in the years 2008–09 followed for the first year of life (n = 8788) migrants (n = 2383) | Maternal citizenship. Mothers who were citizens of HMCs. | ++ | ++ | Higher use of ED in the first year of life by immigrant mothers.g |

| De Luca et al. (2013), Italy29 | Cross-sectional (Population survey: Italian health conditions survey 2004/05) | Nationally representative population sample (0–64 years) (n = 102 857) migrants (n = 5167). | Place of birth and citizenship. | ++ | + | Immigrants have a higher probability of using emergency services than natives. a,b,c,d,f |

| First generation migrants: born outside Italy without Italian citizenship. | ||||||

| Second generation: born in Italy without Italian citizenship. | Highest use in immigrants from Morocco, Africa and Albania. | |||||

| Naturalized Italians: (born outside Italy with Italian citizenship). | ||||||

| Zinelli et al. (2014), Italy16 | Cross-sectional (ED database) | Visits to the ED by Italian-native and foreign born patients during 2008–12 (n = 424 466 visits) (migrants 64 435 visits) | Country of birth. ‘Foreign-born’ persons born outside Italy, whose parents were either foreign citizens or born outside the national territory. (first generation) | + | + | Higher ED use in immigrants. |

| Clement et al. (2010), Switzerland25 | Cross-sectional (ED database) | Patients attending the ED with non-urgent problems (n = 11258) migrants (n = 2948) | Nationality. | + | + | Higher proportion of visits by non-Swiss nationals. |

| Diserens et al. (2015), Switzerland15 | Cross-sectional (Patient survey) | Patients (>16 years) presenting to ED with non-life-threatening condition (n = 1082) migrants (n = 465) | Nationality. | - | + | Higher proportion of visits by non-Swiss nationals. |

| Ruud et al. (2015), Norway27 | Cross-sectional (Patient survey) | Walk-in patients with non-urgent or semi-urgent health conditions attending A&E outpatient clinic (n = 3864). migrants (n = 1364) | Country of birth. | + | + | First and Second generation immigrants use ED more than Norwegians.a,b |

| First generation immigrants: patient and both parents born abroad. | Second generation: Norwegian born with immigrant parents. | |||||

| Higher use among Swedish, Pakistani and Somali. No difference in visits among Polish.a,b | ||||||

| Shah and Cook (2008), England31 | Cross-sectional (Population survey: British general household survey 2004–05) | Persons living in private households in Britain (n = 20421) migrants (n = 1728). | Country of birth. | + | + | No significant difference in use of casualty by immigrants vs. UK born person. a,b,d,f |

| Hargreaves et al. (2006), England26 | Cross-Sectional (Patient survey) | Walk-in patients attending the A&E (n = 1611). migrants (n = 720). | Country of birth and Nationality. | + | + | Overseas-born over-represented in A&E. |

| Nielsen et al. (2012), Denmark30 | Cross-sectional (Nationwide survey, data linked to healthcare registries) | Random sample of each immigrant group and Danes (≥18–66) from nationwide survey (n = 4952) migrants (n = 2866). | Country of birth and citizenship. | ++ | + | Higher among all immigrant groups (except Lebanese). Highest use among Pakistanis, former Yugoslavia and Iran.a,b,f |

| Higher use among second generation immigrants from Turkey.a,b,f No difference in service use for decedents from Pakistan. Increased use of emergency room with increased length of stay in host country, multiplicative effect 2.32-3.03 (except for Iraqi and Turkish immigrants)a,b,c,d,f | ||||||

| Norredam et al. (2004), Denmark22 | Cross-sectional (Data from Statistical office of the Municipality of Copenhagen) | Patients (≥20 years) attending ER (n = 152,253) migrants (n = 24 433). | Country of birth. | ++ | + | Higher ER utilization for persons born in Somali, Turkey and ex-Yugoslavia compared with Danish-born residents.a,b,c |

| Lower ER utilization for persons born in other Nordic countries, the European countries and North Americaa,b,c | ||||||

| No difference in utilization rates for persons born in Iraq, Pakistan and ‘other countries’.a,b,c | ||||||

| Carrasco-Garrido et al. (2009), Spain12 | Cross-sectional (Secondary analysis of survey data: Spanish National Health Survey 2006–07) | Sample of Non-institutionalized adults (≥16 years) resident in Spain (n = 29 478) migrants (n = 1436). | Nationality. Those not from EU, USA or Canada defined as ‘economic migrants’. | + | + | Higher use of emergency services by economic migrants.a,b,d |

| Carrasco-Garrido et al. (2007), Spain11 | Cross-sectional (Secondary analysis of survey data: Spanish National Health Survey 2003) | Sample of non-institutionalized adults (≥16 years) resident in Spain (n = 1506) migrants (n = 502). | Nationality. Non-EU migrants (not from EU, the USA or Canada). | − | + | No significant difference in emergency service use.a,b |

| Hernández-Quevedo and Jiménez-Rubio (2009), Spain13 | Cross-sectional (Secondary analysis of survey data: Spanish National Health Survey 2003 and 2006) | Sample of non-institutionalized adults (≥16 years), resident in Spain (n = 49 123) migrants (n = 2705). | Nationality. | ++ | + | Higher use among non-Spaniards.a,b,c,d,f |

| Highest probability of use among Latin-Americans and Africans. | ||||||

| Lower use among patients from EU and Europe. | ||||||

| No significant difference those from Asia, North America and Oceania.a,b,c,d | ||||||

| Antón and Muñoz de Bustillo (2010), Spain10 | Cross-sectional (Secondary analysis of survey data: Spanish National Health Survey 2006–07) | Sample of non-institutionalized adults (≥16 years), resident in Spain (n = 25 033) migrants (n = 3042). | Country of birth. | ++ | + | Higher use of ED among Non-EU15. EU-15 immigrants show lower rates of emergency service use.a,b,c,d,f |

| Sanz et al. (2011), Spain14 | Cross-sectional (Secondary analysis of survey data: Spanish National Health Survey 2006) | Sample of non-institutionalized adults (≥16–74), resident in Spain (n = 26 728) migrants (n = 3570). | Country of birth. | + | + | Higher, equal and less use by different sub groups. a,b,c,d,f |

| Higher use by men from Latin America; no difference those from Sub-Saharan Africa or North Africa and less use by those from: Western Countries, Eastern Europe and Asia/Oceania. a,c,d,f | ||||||

| Higher use by women from Sub-Saharan Africa.a,c,d,f | ||||||

| Buron et al. (2008), Spain19 | Cross-sectional (ED patient register) | All emergency care episodes for registered patients (≥15 years) living in study area (n = 29 451 visits). Visits by migrants (n = 10 224). | Country of birth. | ++ | ++ | Lower utilization of ED by foreign born.a,b,f |

| López Rillo and Epelde (2010), Spain23 | Cross-sectional (Medical records) | Patients attending the ED during a 2-week period (n = 5660) migrants (n = 792). | Country of origin. | − | + | No significant difference. |

| Rue et al. (2008), Spain24 | Cross-sectional (Hospital database) | Emergency visits in patients (15–64 years) during 2004 and 2005 (n = 96 916 visits) migrants (n = 20 663 visits). | Country of birth. | + | + | Higher use of emergency by immigrants.a |

| Women from Maghreb, Sub-Saharan Africa, Latin America, Eastern Europe and HIC had higher use than Spanish. | ||||||

| Men from Maghreb, HIC, Latin America and Eastern Europe. Rates were lower for other LIC and Sub-Saharan Africa.a | ||||||

| Patient’s presenting condition to the ED | ||||||

| IV | EV | |||||

| Grassino et al. (2009), Italy21 | Cross-sectional. | Patients (0-adolescent) admitted to the ED n = 4874 foreign (n = 2437). | Parents’ country of birth. One or both parents born outside Italy and the EU. | – | + | No difference in presenting pathologies.* |

| Survey of paediatric ED clinical notes. | ||||||

| Buja et al. (2014), Italy18 | Cross-sectional (not stated in paper) (Record linkage database) | Patients (18–65 years) attending A&E (n = 35 541) migrants (n = 5385) | ‘Citizenship’. Nationality assumed to be that of country of birth if not born in Italy. | ++ | + | Significant difference in presenting conditions. |

| Higher digestive disease in TPF males and those from HMPC. | ||||||

| Higher obstetric and gynaecology diagnoses in TPF women. | ||||||

| Clement et al. (2010), Switzerland25 | Cross-sectional (ED database) | Patients attending the ED with non-urgent problems (n = 11 258) migrants (n = 2948). | Nationality. | + | + | No significant difference in admission reason (trauma or other). |

| Ruud et al. (2015), Norway27 | Cross-sectional (Patient survey) | Walk-in patients with non-urgent or semi-urgent health conditions attending A&E outpatient clinic (n = 3864) migrants (n = 1364). | Country of birth. | + | + | Higher use of general emergency clinic (vs. trauma clinic) for migrants. |

| First generation immigrants: patient and both parents born abroad. | ||||||

| Second generation: Norwegian born with immigrant parents. | ||||||

| Buron et al. (2008), Spain19 | Cross-sectional (ED patient register) | All emergency care episodes for registered patients (≥15 years) living in study area (n = 29 451 visits). Visits by migrants (n = 10 224). | Country of birth. | ++ | ++ | Lower use of surgery, traumatology, medicine and psychiatry among foreign-born a,b,f |

| No significant difference In gynaecology, utilization among foreign-born women.a,f | ||||||

| López Rillo & Epelde (2010), Spain23 | Cross-sectional (Medical records) | Patients attending the ED during a 2-week period (n = 5660) migrants (n = 792). | Country of origin. | − | + | Higher rates of presentation with obstetric and gynaecological disease among migrant women. |

| Higher presentation with digestive tract disease among migrants. | ||||||

| Cots et al. (2007) Spain20 | Cross-sectional (Hospital database) | All emergency visits between 2002 and 2003 (n = 165 257 visits) (migrants = 32 822 visits | Country of origin. Neonates classified by parents’ country of origin. | + | ++ | Higher use of gynaecology and obstetric services among migrant women.* |

| Lower use of medicine and traumatology.* | ||||||

| Appropriateness of ED presentation by severity of presenting condition. | ||||||

| References and host country | Study design (sampling method) | Sample and number of migrants | Migrant definition | Quality assessment | Key findings | |

| IV | EV | |||||

| Ballotari et al. (2013), Italy28 | Cohort | Healthy singleton live births in the years 2008–09 followed for the first year of life (n = 8788) migrants (n = 2383) | Maternal citizenship. Mothers who were citizens of HMCs. | ++ | ++ | Immigrants more likely to visit the ER inappropriately.g |

| (Record linkage of three databases) | ||||||

| Grassino et al. (2009), Italy21 | Cross-sectional. | Patients (0-adolescent) admitted to the ED (n = 4874) foreign (n = 2437) | Parents’ country of birth. One or both parents born outside Italy and the EU. | − | + | Both immigrant and Italian patients access ED mostly for non-urgent or semi-urgent conditions. Higher proportion white triage codes among foreigners.* |

| Survey of paediatric ED clinical notes. | ||||||

| Brigidi et al. (2008), Italy17 | Cross-sectional (ED patient database) | Patients attending ED. 51 000 patients treated (Latin Americans n = 3832). | Country of origin: Latin America. | − | + | Latin American users of the ED use the ED for non-urgent rather than emergency medical treatment. Higher percentage of white triage codes among Latin Americans.* |

| Buja et al. (2014), Italy18 | Cross-sectional (not stated in paper) (Record linkage database) | Patients (18–65 years) attending A&E (n = 35 541) migrants (n = 5385). | ‘Citizenship’. Nationality assumed to be that of country of birth if not born in Italy. | ++ | + | Foreigners more likely to attend A&E with non-urgent clinical conditions. |

| Zinelli et al. (2014), Italy16 | Cross-sectional (ED database) | Visits to the ED by Italian-native and foreign born patients during 2008–12 (n = 424 466 visits. (migrants 64 435 visits) | Country of birth. ‘Foreign-born’ persons born outside Italy, whose parents were either foreign citizens or born outside the national territory. (first generation) | + | + | Higher rate of use of ED for non-urgent conditions among migrants. |

| Clement et al. (2010), Switzerland25 | Cross-sectional (ED database) | Patients attending the ED with non-urgent problems n = 11 258. Migrants (n = 2948) | Nationality. | + | + | Significantly higher attendance at ED with non-urgent conditions among foreigners. |

| Diserens et al. (2015), Switzerland15 | Cross-sectional (Patient survey) | Patients (≥16 years) presenting to ED with non-life-threatening condition. N = 1082 (Migrants n = 465) | Nationality. | − | + | Higher proportion of foreigners visits ED with non-urgent conditions.* |

| López Rillo and Epelde (2010), Spain23 | Cross-sectional (Medical records) | Patients attending the ED during a 2-week period (n = 5660) migrants (n = 792). | Country of origin. | − | + | No significant difference in severity of triage scores. |

| Cots et al. (2007), Spain20 | Cross-sectional (Hospital database) | All emergency visits between 2002 and 2003 (n = 165 257 visits) (migrants = 32 822 visits | Country of origin. Neonates classified by parents’ country of origin. | + | ++ | Lower cost of treating migrants in ED compared with Spanish patients reflects lower complexity of emergency care and workload.a,b,f |

| Patient’s arrival time at the ED | ||||||

| References and host country | Study design (sampling method) | Sample and number of migrants | Migrant definition | Quality assessment (IV) and external | Key findings | |

| IV | EV | |||||

| Zinelli et al. (2014), Italy16 | Cross-sectional (ED database) | Visits to the ED by Italian-native and foreign born patients during 2008–12 (n = 424 466 visits) (migrants 64 435 visits) | Country of birth. ‘Foreign-born’ persons born outside Italy, whose parents were either foreign citizens or born outside the national territory. (first generation) | + | + | No significant difference between the percentage of Italians and migrants seen during the day and night shifts. |

| Clement et al. (2010), Switzerland25 | Cross-sectional (ED database) | Patients attending the ED with non-urgent problems (n = 11 258) migrants (n = 2948) | Nationality. | + | + | Non-Swiss nationals significantly more likely to present to ED during unsocial hours. |

| López Rillo and Epelde (2010), Spain23 | Cross-sectional (Medical records) | Patients attending the ED during a 2-week period (n = 5660) migrants (n = 792). | Country of origin. | - | + | Immigrants significantly more likely to present during unsocial hours. |

| No differences in day of week patients attend. | ||||||

| Grassino et al. (2009), Italy21(paediatric) | Cross-sectional. | Patients (0-adolescent) admitted to the ED n = 4874. (Foreign n = 2437) | Parents’ country of birth. One or both parents born outside Italy and the EU. | − | + | No Difference* |

| Survey of paediatric ED clinical notes. | ||||||

| Buja et al. (2014), Italy18 | Cross-sectional (not stated in paper) (Record linkage database) | Patients (18–65 years) attending A&E (n = 35 541) migrants (n = 5385) | ‘Citizenship’. Nationality assumed to be that of country of birth if not born in Italy. | ++ | + | Patients arriving at weekends and bank holidays mainly Temporarily Present Foreigners and those from High Migratory Pressure Countries. |

| Most patients arrive at A& E between 08:00–16:00 h, patients arriving between 16:00 and 24:00 h mainly from HMPC group. | ||||||

Note: A study that reported more than one review outcomes of interest will appear more than once in the table. ++, all or most of the checklist criteria have been fulfilled; where they have not been fulfilled the conclusions are very unlikely to alter. +, some of the checklist criteria have been fulfilled, where they have not been fulfilled, or not adequately described, the conclusions are unlikely to alter. −, few or no checklist criteria have been fulfilled and the conclusions are likely or very unlikely to alter.9

Adjusted for age.

Adjusted for gender.

Adjusted for socio-economic status.

Adjusted for health status.

Adjusted for time in host country.

Adjusted for other factors (region, marital status, Attending speciality, Triage colour).

Adjusted for mother’s age at delivery, mother’s educational level, child gender, previous live births.

Not tested for significance.

The sample sizes (and number of migrants included) varied greatly between the studies. These ranged from a sample of 1082 (including 465 migrants)15 to a cross sectional study of 424 466 ED visits of which 64 435 were visits by migrant patients.16 Eighteen studies include more than 1000 migrants.

The sample of patients included in the studies set within EDs varied with regard to the severity of presenting conditions. The population of interest in nine studies consisted of all patients or all ED visits in a defined time period16–24 while four studies only included patients presenting with non-urgent/non-life-threatening conditions or ‘walk-in’ patients.15,25–27 The one cohort study included in this review followed a cohort of healthy children for their first year of life.28

The definitions used for ‘migrants’ varied between the included studies. Information on ‘country of birth’ or ‘country of origin’ was used to determine migrant status in 15/22 articles, while ‘nationality’ or ‘citizenship’ was used in 10 studies (3 articles recorded both country of birth and nationality/citizenship). Three studies further classified patients as first or second generation migrants for their analyses.27,29,30 In the studies that include a paediatric sample, parents’ country of birth or maternal citizenship was used to determine migrant status.

In the results presented in the studies, sub-group analysis was undertaken in many studies where the authors used country-of-birth/origin to categorize patients. These sub-groups were based on the predominant migrant groups in the region or country studied. Categories for sub-group analysis were also determined by the economic status or level of economic development of the countries of origin, irrespective of whether the country was considered a high migration country (HMC) or not, and whether the country belongs within or outside the EU. Fourteen studies included adjustment for socio-demographic factors in their analysis of the outcomes of interest (table 2).

Table 2.

Socio-demographic factors adjusted for in the analyses of 14 of the 22 included studies

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ballotari et al. (2013)28 | • | ||||||

| De Luca et al. (2013)29 | • | • | • | • | • | ||

| Ruud et al. (2015)27 | • | • | |||||

| Shah and Cook (2008)31 | • | • | • | • | |||

| Nielsen et al. (2012)30 | • | • | • | • | • | • | |

| Norredam et al. (2004)22 | • | • | • | ||||

| Carrasco-Garrido et al. (2009)12 | • | • | • | ||||

| Carrasco-Garrido et al. (2007)11 | • | • | |||||

| Hernández-Quevedo and Jiménez-Rubio (2009)13 | • | • | • | • | • | ||

| Antón and Muñoz de Bustillo (2010)10 | • | • | • | • | • | ||

| Sanz et al. (2011)14 | • | • | • | • | • | ||

| Buron et al. (2008)19 | • | • | • | ||||

| Rue et al. (2008)24 | • | ||||||

| Cots et al., 200720 | • | • | • | ||||

| Remaining Eight studies |

Note: a, adjusted for age; b, adjusted for gender; c, adjusted for socio-economic status; d, adjusted for health status; e, adjusted for time in host country; f, adjusted for other factors (e.g. region, marital status, attending speciality, Triage colour); g,adjusted for mother’s age at delivery, mother’s educational level, child gender, previous live births.

Utilization of EDs by volume of service use

The studies included in this review differ in the utilization indicators used to describe volume of ED service use. Differences are apparent in whether service use measured ED contacts or visits; in the time scale used to measure the probability of service use (previous 4 weeks, 3 months, 12 months); and in the choice of comparison group (non-migrant patients attending the ED/proportion of migrants in the population).

Fifteen studies report on ED use by migrants as compared with non-migrants.10–13,15,16,19,20,23–29,31 A further three studies provide estimates of ED utilization by immigrant sub-group only.14,22,30 The trend that is evident in these results is that migrants have higher ED utilization than non-migrants and that the use of the ED differs by immigrant sub-group (country of origin and gender sub-groups). One study looking at utilization of the ED for children showed that, in Italy, immigrant mothers were significantly more likely to use the ED than non-migrant mothers.28 This higher use was apparent for mothers from all geographic regions and was twice as high for mothers from Sub-Saharan Africa.28

Ten studies show higher use of the ED for adult migrants.10,12,13,15,16,24–27,29 Four of these adjusted for health status in their analyses.10,12,13,29 In an additional three studies immigrants from particular countries were found to have higher use of the ED as compared with non-migrants.14,22,30 No-significant difference in utilization by immigrants as compared with non-migrants was seen in three studies.11,23,31 Of these, only the study by Shah, 2008, adjusted for health status. In contrast to these findings, a Spanish study showed lower use of the ED by migrants.19 This study adjusted for age, sex and emergency specialty.

Significant differences in ED utilization by migrant originating country were found in nine studies.10,13,14,22,24,27–30 In Italy, Moroccan immigrants have been seen to have the greatest probability of using the ED compared with native Italians.29 A study from Norway showed that migrants from Pakistan, Somalia and Sweden used the ED significantly more.27 Similarly, in Denmark patients from Pakistan30 and those from Somalia22 have been shown to use the ED more than natives. In Spain, higher service use was most pronounced for Latin Americans and Africans.13 A further two Spanish studies found that Latin American men and sub-Saharan African women,14 and men and women from the Maghreb,24 showed a higher probability of ED use than natives. Among the paediatric population in Italy, mothers from all geographic regions were more likely to use the ED than Italian mothers; the likelihood of ED utilization was doubled for mothers from sub-Saharan Africa.28

Looking specifically at ED use by migrants from within Europe, lower utilization of the ED by migrants from European countries was found in four studies.10,12,13,22 This association remained when three of these studies adjusted for health status.10,12,13

Utilization of ED services by arrival time at the ED

Five studies analysed differences in time of patient arrival at the ED between migrants and non-migrants.16,18,21,23,25 Three of these showed that migrants were significantly more likely than non-migrants to present to the ED during unsocial hours.18,23,25 In contrast, one study reported no statistically significant difference between the percentage of migrants vs. natives seen during day and night shifts.16 The only study reporting on paediatric ED visits showed no difference between the comparison groups, although this was not tested for significance.21 Looking at specific migrant sub-groups in Switzerland, patients from Balkan and African countries have been found to visit the ED significantly more frequently during unsocial hours as compared with Swiss nationals.25

Two studies assessed the utilization of the ED by the day of the week, with contrasting results. In Italy, patients arriving at weekends and on bank holidays were most likely to be ‘temporarily present foreigners’ or migrants from high migratory pressure countries.18 In contrast, no significant difference in day of the week of patient attendance was observed in Spain, with the majority of patients presenting during weekdays.23

Utilization of ED by presenting condition

Seven articles provided information about the differences in presenting conditions between migrants and non-migrants. Grassino et al. (2009), reported that there was no difference in the presenting pathologies between foreign or Italian children and that both groups of patients presented most often with respiratory or gastro-enteric diseases. Differences in presenting pathologies among adult migrants were evident in four articles.18–20,23 Common to three of these articles was the finding of a higher rate of obstetric and gynaecology diagnoses among migrant women.18,20,23 Buja et al. (2014) and Lopez Rillo and Epelde (2010), also found that adult migrants were more likely to present with digestive diseases.18,23

The findings regarding the use of particular specialities among adult migrants vary, showing no difference in attending speciality25 nor any greater use of general emergency clinic than trauma clinic.27 Two further studies show lower use of surgery, traumatology and medicine for migrants as compared with non-migrants.19,20

Utilization of ED by appropriateness of presentation

The severity of patient presentation (reflecting the clinical ‘appropriateness’ of service use) was measured in eight articles according to the triage categories given to each patient at initial assessment. In addition, one paper assessed the variable cost of treating patients and used this as a proxy to reflect the complexity of emergency care involved in patient treatment.20 Two articles reporting on severity of paediatric presentations both show a higher use of the ED for non-urgent conditions by immigrant patients.21,28 One of these was not tested for significance.21

Five of the six studies that used a triage scale to assess the severity of presentation among adult patients showed that migrant patients were more likely than native patients to use the ED for low-acuity presentations. Three of these articles tested their results for significance and the associations remained.16,18,25 A further two studies appear to show higher percentages of low-acuity triage codes among migrants, although these were not tested for significance.15,17 Only one study showed no significant difference in the severity of triage scores between the two populations.23 This study concluded that both migrants and non-migrants consult for mostly non-urgent conditions, which reflects the findings of many other studies.23

The final study included in this analysis compared the average direct cost of treating migrants as compared with non-migrants. The findings from this study showed that the cost of treating migrants was significantly lower than non-migrants, reflecting lower complexity of emergency care involved in treatment.20

Discussion

The principal findings of this review are that migrants in EEA countries show higher use of the ED than the native population and that different immigrant subgroups use the ED differently. These results are similar to those from a review by Norredam et al. (2010), which showed a trend towards higher utilization of the ED by migrants in Europe.6 These findings also suggest that migrants attend the ED for presentations that could be better managed in PHC settings. ‘Irrelevant’ visits to the ED by immigrants have previously been reported in a Danish study.2 The higher use of the ED for low-acuity presentations suggests that migrant patients are not necessarily an unhealthy population in need of emergency care but, rather, that there may be barriers to accessing more appropriate healthcare services in their host countries.

Thirteen articles report higher volume of ED service-use either by immigrants as a whole or by some immigrant sub-groups, The higher rates of ED utilization appear to pertain mostly to non-European immigrants, particularly those from the ‘global South’, with lower utilization rates by migrants from European countries found in three studies.10,13,22 It is important to highlight these findings, given the highly politicized nature of migration, particularly with regard to the free flow of migrants between countries in the EU, and the perceived pressure that European migrants place on public services within these countries.

Possible explanations for review findings

The use of healthcare services can be seen as a function of environmental factors as well as factors in the external environment and particular population characteristics that may act to either facilitate or impede the use of particular healthcare services.32 Although limited evidence exists to quantify migrants’ use of EDs or to provide qualitative evidence of their reasons for the use of these services, a number of explanations for the differences in ED utilization between migrants and native populations are proposed.

Despite universal access to emergency care services in many settings, barriers to PHC may mean that migrant patients preferentially access ED services. Migrants may not register with a GP due to a lack of awareness, or knowledge of entitlement to available services.33 In addition, short duration of stay in the host country and language barriers may prevent registration and consultation with a primary care provider.33 These barriers to PHC service use may partly explain the higher percentage of low-acuity presentations to the ED. Furthermore, in three articles migrants were found have higher self-referral rates to the ED which, again, may be evidence of barriers to more appropriate healthcare.16,18,25 The findings that show higher use of obstetric and gynaecology services by migrant women may serve as a further example. Migrant women, who are generally of reproductive age, may face barriers to accessing antenatal or gynaecology services in the PHC setting and as a result seek these services in an ED.23,24

Health literacy, in particular a lack of understanding of the healthcare system, has been suggested as a reason for ED use, as the ED is a highly visible and accessible service.2,33 In many European countries GPs act as gate-keepers to more specialized care and many migrants may be unfamiliar with this design.34 Without knowing where or how to access PHC, patients may instead use the ED in times of healthcare need. This review found that, on sub-group analysis, migrants from the ‘global South’ showed higher levels of ED service use. For migrants moving from the South to the North (moving from ‘developing’ to ‘developed country’) it may be important to consider their educational background, socio-economic status and language capabilities when interrogating the patterns of, and reasons for, the use of EDs. The observed differences in the utilization of EDs by different immigrant sub-groups may reflect differences in the need for healthcare, or may serve as an indication of particular barriers to receiving healthcare faced by some immigrant groups. This highlights the importance of separately assessing migrants’ use of the EDs by different legal statuses and countries of origin.

The restricted opening hours of PHC facilities may be a further contributing factor to the over-utilization of the ED. Migrants, many of whom are in unstable employment situations, may have difficulty visiting a doctor during normal working hours.24 Accessing care in the ED for low-acuity conditions could serve as further evidence that immigrants are, in some instances, forced to seek healthcare out-of-hours as a result of inflexible working conditions.

It is also important to consider the differences in healthcare utilization in light of the analyses undertaken in each study, particularly to assess whether confounding may distort the relationships seen. Few studies included in this review adjusted their analyses for factors other than ‘age’ or ‘gender’ and thus confounding may be present in the results observed. Socio-economic status may be one such confounder that was only adjusted for in six studies. A high proportion of newly arriving migrants settle in deprived urban areas in their host countries35 and it is know that, in some settings, healthcare services serving deprived areas have high rates of potentially avoidable admissions.3

In addition, duration of residence in a host country may be another important confounder. It may be hypothesized that with increasing length of stay migrants have access to additional healthcare resources, may become better integrated into the society and acquire a greater understanding of the healthcare system, and this in turn may impact on how they use healthcare services. Significant differences in healthcare utilization by recent immigrants have been found to decrease with increasing duration of residence in the USA.36 However, only one study in this review adjusted for length of stay and this analysis found that the use of the ED increased with length of stay for most migrant groups.30 Without data on length of stay in the host country in more than one study it is not possible to determine whether this pattern is evident in other settings.

Strengths and weaknesses of the study

This is the first systematic review that looks at migrants’ use of emergency services beyond ‘volume of ED service use’ only. A carefully designed, highly sensitive search strategy was used in this review and it is thought unlikely that the search failed to identify additional articles that would have altered the overall findings significantly. However, it is possible that additional, eligible studies may not have been identified.

Studies included in this review were limited to English language publications and it is possible that important publications in other European languages could have been excluded. Studies were also restricted to those from 2000 onwards to ensure that only the most recent evidence was included and this may be seen as a limitation. As a result, previous findings that have been excluded may have altered the overall review findings. Finally, studies that looked at specific conditions in migrant patients attending the ED (e.g. psychiatric diagnoses) were excluded from this review and the utilization patterns for specific conditions may have implications for the healthcare services.

The quality of the included studies varied greatly, with considerable risk of bias and lack of external validity in some of them. This high risk of bias lies mainly with the observational design of these studies, selection bias, and analyses that didn’t fully control for factors that might have confounded the results. Although no great difference in the overall direction of the observed associations and the strength of these associations was apparent between the studies that adjusted for confounders and those that did not, drawing general conclusions across these study findings is made more difficult because of the methodological inconsistencies between studies. The risk of bias in many of the included studies was also affected by the outcome measures used and the reliability of the procedures for measuring these outcomes.

There are no universally accepted definitions for migrants and migration research and, as a result, the definitions for migrants used in the included articles varied greatly. Furthermore, in some instances the definitions provided for the comparison groups were vague. Without standard definitions, comparing these studies to one another is a problem. What is clear, and has been highlighted in a previous review, is that common definitions need to be used in future research to ensure comparability across studies.6

The literature identified in this review suggests that there is limited evidence regarding particular aspects of migrants’ use of EDs. Only three studies were identified that included a paediatric population. There may be differences in migrants’ use of EDs for their own care as compared with their use of services for their children. In addition, limited evidence pertaining to asylum seekers, refugees and undocumented migrants as compared with the autochthonous population was found. Understanding how services are used by these populations will aid in determining whether specific barriers to care are present for particular groups of patients. With very limited evidence it is not possible to make meaningful statements on the use of EDs for children, or asylum seekers, refugees or undocumented migrants and further research is needed to address these research gaps.

The studies included in this review represent a number of different countries that have very different migrant populations as well as differing healthcare systems. In addition, a number of studies were conducted at local or regional level and the results of these studies may only be applicable to these settings. Although the results of individual studies may not be generalizable across wider populations, what is clear is that some of the trends seen regarding migrants’ use of EDs are not country-specific but are evident in many of the EEA country settings. These trends are important as many cross-border healthcare policies impact on healthcare services within the EU.

Research implications

Considerable scope exists for further research to understand fully how and why migrants use EDs. In designing future studies careful consideration needs to be given to how migrants are defined and to the outcomes to be reported so as to enable comparisons between studies.6 Ideally, both country of birth and citizenship should be collected to enable migration history to be determined. Studies should also capture the time since arrival in the host country as this is an important predictor of healthcare utilization37 and provides information regarding migration history.

It is clear is that there is a need to understand the relationship between primary care and ED use by patients within specific settings. The differences in the organization of PHC systems and patients’ entitlement to use these services across Europe make it difficult to establish whether the barriers to PHC mentioned as possible reasons for over utilization of the ED are applicable within and between healthcare systems in the EU. The differences in utilization of EDs are likely to reflect differing needs for healthcare and the accessibility of the healthcare services in particular settings, and this will have particular implications for specific healthcare services. Furthermore, in-depth qualitative research is needed that looks at migrants’ reasons for using EDs.

Conclusion

This systematic review synthesizes available evidence on the differences in utilization of EDs between migrants and non-migrants in EEA countries. The findings from this review show that migrants use EDs in Europe more, and differently, to non-migrants and this may reflect barriers to more appropriate healthcare.

Migration across Europe is increasing and to ensure equity in access, healthcare services need to be appropriately designed to meet the needs of the populations they serve. It is clear that further research is needed that quantifies migrants’ use of emergency services and interrogates migrants’ reasons for using EDs. A clearer understanding of migrants’ use of EDs will inform healthcare service planning and service delivery and help to ensure that these services are designed to meet the needs of the demographically changing population in Europe.

Supplementary data

Supplementary data are available at EURPUB online.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Institute for Health Research Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care Yorkshire and Humber (NIHR CLAHRC YH) grant number: IS-CLA-0113-10020. www.clahrc-yh.nihr.ac.uk. The views and opinions expressed are those of the author(s), and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health.

Conflict of interest: None declared.

Key points

The review findings suggest that migrants show higher levels of emergency department (ED) utilization, and that their use of the ED differs to that of non-migrants across Europe.

Trends may reflect differing health needs and problems in accessing alternative healthcare.

The higher use of the ED for low-acuity presentations and the use of the ED during unsocial hours suggest that barriers to primary healthcare may be driving the higher use of ED services.

A greater understanding of migrants’ healthcare needs and how they utilize EDs in Europe is needed to inform healthcare services, to ensure they are designed to meet the needs of the demographically changing population.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1. Pines JM, Hilton JA, Weber EJ, et al. International perspectives on emergency department crowding. Acad Emerg Med 2011;18:1358–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Norredam M, Mygind A, Nielsen AS, et al. Motivation and relevance of emergency room visits among immigrants and patients of Danish origin. Eur J Public Health 2007;17:497–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. O’Cathain A, Knowles E, Turner J, Maheswaran R, Goodacre S, Hirst E, et al. Explaining variation in emergency admissions: a mixed-methods study of emergency and urgent care systems. Health Serv Deliv Res 2014;2:48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Rechel B, Mladovsky P, Ingleby D, et al. Migration and health in an increasingly diverse Europe. Lancet 2013;381:1235–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Urquia ML, Gagnon AJ. Glossary: migration and health. J Epidemiol Commun Health 2011;65:467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Norredam M, Nielsen SS, Krasnik A. Migrants' utilization of somatic healthcare services in Europe-a systematic review. Eur J Public Health 2010;20:555–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Gushulak B, Weekers J, Macpherson D. Migrants and emerging public health issues in a globalized world: threats, risks and challenges, an evidence-based framework. Emerg Health Threats J 2010;2:e10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Clough J, Lee S, Chae DH. Barriers to health care among Asian immigrants in the United States: a traditional review. J Health Care Poor Underserved 2013;24:384–403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Methods for the Development of NICE Public Health Guidance, 3rd edn. London: National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, 2012. [PubMed]

- 10. Anton JI, Munoz de Bustillo R. Health care utilisation and immigration in Spain. Eur J Health Econ 2010;11:487–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Carrasco-Garrido P, De Miguel AG, Barrera VH, Jiménez-García R. Health profiles, lifestyles and use of health resources by the immigrant population resident in Spain. Eur J Public Health 2007;17:503–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Carrasco-Garrido P, Jimenez-Garcia R, Barrera VH, et al. Significant differences in the use of healthcare resources of native-born and foreign born in Spain. BMC Public Health 2009;9:201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hernández-Quevedo C, Jiménez-Rubio D. A comparison of the health status and health care utilization patterns between foreigners and the national population in Spain: New evidence from the Spanish National Health Survey. Soc Sci Med 2009;69:370–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Sanz B, Regidor E, Galindo S, et al. Pattern of health services use by immigrants from different regions of the world residing in Spain. Int J Public Health 2011;56:567–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Diserens L, Egli L, Fustinoni S, Santos-Eggimann B, Staeger P, Hugli O. Emergency department visits for non-life-threatening conditions: evolution over 13 years in a Swiss urban teaching hospital. Swiss Med Wkly 2015;145: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Zinelli M, Musetti V, Comelli I, et al. Emergency department utilization rates and modalities among immigrant population. A 5- year survey in a large Italian urban emergency department. Emerg Care J 2014;10:22–5. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Brigidi S, Cremonesi P, Cristina ML, et al. Inequalities and health: analysis of a model for the management of Latin American users of an emergency department. J Prev Med Hyg 2008;49:6–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Buja A, Fusco M, Furlan P, et al. Characteristics, processes, management and outcome of accesses to accident and emergency departments by citizenship. Int J Public Health 2014;59:167–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Buron A, Cots F, Garcia O, et al. Hospital emergency department utilisation rates among the immigrant population in Barcelona, Spain. BMC Health Serv Res 2008;8:51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Cots F, Castells X, Garcia O, et al. Impact of immigration on the cost of emergency visits in Barcelona (Spain). BMC Health Serv Res 2007;7:9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Grassino EC, Guidi C, Monzani A, et al. Access to paediatric emergency departments in Italy: A comparison between immigrant and Italian patients. Ital J Pediatr 2009;35: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Norredam M, Krasnik A, Moller Sorensen T, et al. Emergency room utilization in Copenhagen: a comparison of immigrant groups and Danish-born residents. Scand J Public Health 2004;32:53–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lopez Rillo N, Epelde F. Immigrants' use of hospital emergency services. Emergencias 2010;22:109–12. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Rue M, Cabre X, Soler-Gonzalez J, et al. Emergency hospital services utilization in Lleida (Spain): a cross-sectional study of immigrant and Spanish-born populations. BMC Health Serv Res 2008;8:81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Clement N, Businger A, Martinolli L, Zimmermann H, Exadaktylos AK. Referral practice among Swiss and non-Swiss walk-in patients in an urban surgical emergency department. Swiss Med Wly 2010;140:w13089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hargreaves S, Friedland JS, Gothard P, et al. Impact on and use of health services by international migrants: questionnaire survey of inner city London A&E attenders. BMC Health Serv Res 2006;6:153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ruud SE, Aga R, Natvig B, Hjortdahl P. Use of emergency care services by immigrants-a survey of walk-in patients who attended the Oslo Accident and Emergency Outpatient Clinic. BMC Emerg Med 2015;15:25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ballotari P, D'Angelo S, Bonvicini L, et al. Effects of immigrant status on Emergency Room (ER) utilisation by children under age one: a population-based study in the province of Reggio Emilia (Italy). BMC Health Serv Res 2013;13:458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. De Luca G, Ponzo M, Andres AR. Health care utilization by immigrants in Italy. Int J Health Care Finance Econ 2013;13:1–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Nielsen SS, Hempler NF, Waldorff FB, et al. Is there equity in use of healthcare services among immigrants, their descendents, and ethnic Danes?. Scand J Public Health 2012;40:260–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Shah SM, Cook DG. Socio-economic determinants of casualty and NHS Direct use. J Public Health 2008;30:75–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Andersen RM. Revisiting the behavioral model and access to medical care: does it matter?. J Health Soc Behav 1995;36:1–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Mahmoud I, Eley R, Hou XY. Subjective reasons why immigrant patients attend the emergency department. BMC Emerg Med 2015;15:4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Smaland Goth UG, Berg JE. Migrant participation in Norwegian health care. A qualitative study using key informants. Eur J Gen Pract 2011;17:28–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Robinson D. The Neighbourhood Effects of New Immigration. Environ Plan A 2010;42:2451–66. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Leclere FB, Jensen L, Biddlecom AE. Health care utilization, family context, and adaptation among immigrants to the United States. J Health Soc Behav 1994;35:370–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Dias SF, Severo M, Barros H. Determinants of health care utilization by immigrants in Portugal. BMC Health Serv Res 2008;8:207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.