Abstract

Background

Despite the large number of studies and reviews available, the evidence regarding the policy determinants of physical activity (PA) is inconclusive. This umbrella systematic literature review (SLR) summarizes the current evidence on the policy determinants of PA across the life course, by pooling the results of the available SLRs and meta-analyses (MAs).

Methods

A systematic online search was conducted on MEDLINE, ISI Web of Science, Scopus and SPORTDiscus databases up to April 2016. SLRs and MAs of observational studies investigating the association between policy determinants of PA and having PA as outcome were considered eligible. The extracted data were assessed based on the importance of the determinants, the strength of evidence and the methodological quality.

Results

Fourteen reviews on 27 policy determinants of PA were eligible for this umbrella SLR. The majority of the reviews were of moderate quality. Among children, a clear association between time spent outdoors and PA emerged. Among adults, working hours were negatively associated with PA, though evidence was limited. At the population level, community- and street-scale urban design and land use policies were found to positively support PA levels, but levels of evidences were low.

Conclusions

With this umbrella SLR the policy determinants of PA at individual-level and population-level have been summarized and assessed. None of the investigated policy determinants had a convincing level of evidence, and very few had a probable level of evidence. Further research is needed, preferably by using prospective study designs, standardized definitions of PA and objective measurement of PA.

Introduction

Regular physical activity (PA) not only reduces the risks of a range of non-communicable diseases (NCDs), but also has significant benefits for health by improving muscular and cardiorespiratory fitness, ameliorating bone and functional health, reducing the risk of falls and of hip or vertebral fractures, and helping with energy balance and weight control.1

Worldwide, 31% of adults are physically inactive.2 Insufficient levels of PA have been identified as the fourth leading risk factor for NCDs and global mortality, causing an estimated 3.2 million deaths globally each year.1 Low levels of PA are thus a current global concern and increasing PA engagement is becoming a priority in current public health policies.

With the overall aim of providing national and regional level policy makers with guidance on the dose-response relationship between the frequency, duration, intensity, type and total amount of PA needed for the prevention of NCDs, the WHO developed ‘Global Recommendations on Physical Activity for Health’.3

Understanding why people are physically active or inactive contributes to evidence-based planning of public health interventions, because effective programs will target factors known to cause inactivity.4 A number of interdependent and multilevel factors (e.g. determinants with a causal relationship or correlates associated with PA) influence active lifestyles,4–7 and several ecological models have been proposed to classify and explain the complex interplay between individual-level and environmental-level factors able to promote or hinder PA behaviours.4,5,7–10

Environmental variables were defined by Ferreira and colleagues as ‘anything outside the individual that can affect his/her PA behaviour’.6 Environmental and policy approaches are designed to provide environmental opportunities, support and cues for the promotion of PA.11 Population-based strategies are complements to individual-based efforts and also have the potential for broad and sustained impact.12

Research into environmental policy determinants able to enhance, maintain, or restrict PA behavior, has increased in the past two decades. However, the wide variability of study aims, studied variables, and measurement methods, limit the potential comparison and aggregation of findings, leading to the lack of unique and structured evidence, and highlighting the need for a systematic analysis of the policy determinants of PA.

Recently, the European Commission endorsed a Joint Programming Initiative to increase research capacity across Member States to engage in a common research agenda on healthy diet and healthy lifestyles13 and the DEterminants of DIet and Physical ACtivity Knowledge Hub (DEDIPAC-KH) project has been approved.14 To expand knowledge and to develop new insights and solutions oriented at the development and implementation of effective health promotion strategies and PA enhancing policies, the Thematic Area 2 of the DEDIPAC-KH project organized seven umbrella systematic literature reviews (SLRs) on biological, psychological,15 behavioral,16 physical,17 socio-cultural, economic and policy determinants of PA.

This umbrella SLR focuses on the policy determinants of PA. The political environment was defined as in the framework provided by Swinburn and colleagues,10 and refers to the rules related to PA. The political environment includes laws, regulations, policies (formal and informal) and institutional rules, at both the micro-environmental (e.g. homes, workplaces, schools and neighborhoods) and the macro-environmental (e.g. city, municipalities and regions) levels.10

The aim of this umbrella SLR is to provide an overview of the studies investigating policy determinants influencing PA across the life course by systematically reviewing and evaluating the available evidence from existing SLRs and meta-analyses (MAs) of primary observational studies.

Methods

This manuscript adheres to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) checklist.18 A common protocol of the seven umbrella SLRs (biological, psychological, behavioral, physical, socio-cultural, socio-economic and policy) was registered and is available on PROSPERO (Record ID: CRD42015010616), the international prospective register of systematic reviews19 Review title, timescale, team details, methods and general information were all recorded in the PROSPERO register prior to completing data extraction.

Search strategy and eligibility criteria

The same search strategy was used for all seven umbrella SLRs. SLRs and MAs investigating the determinants of PA across the life course were systematically searched on MEDLINE, ISI Web of Science, Scopus and SPORTDiscus. The search was limited to reviews published in the English language from 1 January 2004 up to 30 April 2016. Reviews published before 2004 were not included to avoid duplications of the earliest individual studies. The MEDLINE search strategy is shown in Supplementary material (Supplementary table S1); this was also used as the template for the search strategies in the other databases.

In addition to the databases’ systematic search, a snowball method was applied to the references of the reviews to identify any possible missed SLR and MA.

SLRs or MAs of observational primary studies on the association between any determinant and PA, or exercise, or sport as main outcome, were included in seven umbrella SLRs. The following studies were excluded: (i) SLRs and MAs of intervention studies; (ii) SLRs and MAs that focused on specific population groups (e.g. chronic diseases); (iii) umbrella SLRs on the same topic (e.g. reviews of SLRs or MAs of epidemiological studies on variables associated with PA).

The current umbrella SLR focuses only on policy determinants of PA, referring to the rules related to PA as defined in the framework provided by Swinburn and colleagues.10

Selection process

Relevant articles were independently screened and assessed by two reviewers belonging to the DEDIPAC-KH, who screened the titles, the abstracts, and the full texts. Any uncertainty and disagreement was resolved by consulting three further authors (SB, LC, AP).

Data extraction

For each included SLR and MA, data were extracted on a pretested data extraction forms developed by the DEDIPAC-KH and checked by two authors (KA, AP).

In reporting data, authors agreed to define as ‘reviews’ those SLRs and MAs found eligible for the umbrella SLR, and as ‘primary studies’ those studies included in the eligible SLRs and MAs. Moreover, authors agreed to use the term ‘PA’ as inclusive of non-structured (e.g. movements linked with daily life) and structured activities (e.g. PA, exercise and sports) independently from their frequency, duration and intensity.

From each included review, the following information was extracted: year of publication, type of review (either SLR or MA), number of eligible primary studies included in the policy umbrella SLR over the total number of primary studies included in the review; continent/s of the included primary studies, primary study design, overall sample size, age range or mean age, gender proportion, year range of included primary studies; outcome details, type of determinant/s, aim of the review; overall results (descriptive or quantitative), overall recommendations and limitations as provided by the review itself.

Evaluation of importance of determinants and strength of the evidence

The results retrieved from the eligible primary studies included in the reviews were summarized combining two grading scales, previously introduced by Sleddens et al.20 but modified in the current review as explained below. The first grading scale, the importance of the determinants, refers to the consistency of the associations among the reviews, or the individual primary studies. The second grading scale, the strength of evidence, refers to the study design used among individual primary studies.

A determinant for its importance scored a ‘–’ if all reviews, without exception, reported a negative association between the determinant and the outcome, and a ‘−’ if the negative association was found in >75% of the reviews or of the primary studies. The importance of the determinant was scored a ‘0’ if the results were mixed, or more specifically, if the variable was found to be a determinant and/or reported an association (either positive or negative) in 25–75% of available reviews or of the primary studies of these reviews, but not in others. Furthermore, the importance of a determinant scored a ‘+’ if a positive association was found in >75% of the reviews or of the included primary studies and a ‘ ++’ if a positive association was found in all reviews, without exception.

The strength of the evidence was described as ‘convincing’ (Ce) if it was based on a substantial number of longitudinal observational studies, with sufficient size and duration, and showing consistent associations between the determinant and PA. The strength of the evidence was defined as ‘probable’ (Pe) if it was based on at least two cohort studies or five case-control studies showing fairly consistent associations between the determinant and PA. Furthermore, the strength of the evidence was given as ‘limited suggestive evidence’ (Ls) if it was based mainly on findings from cross-sectional studies showing fairly consistent associations between the determinant and PA, and as ‘limited, no conclusive evidence’ (Lns) if study findings were suggestive, but insufficient to provide an association between the determinant and PA [and if no longitudinal data available].

Quality assessment

The methodological quality of the included reviews was assessed using a modified version of the AMSTAR checklist.21 A consensus between the DEDIPAC-KH partners was reached to modify the question referring to the presence of any conflict of interest (criteria number 11), so that the conflict of interest was evaluated in the reviews included and not in the primary studies included in each review.

Two reviewers belonging to the DEDIPAC-KH independently evaluated the included reviews, using the same methodology of Sleddens et al.20 Any uncertainty and disagreement was resolved by consulting three further authors (SB, LC, AP). The eleven criteria were evaluated and scored as a 1 when the criterion was applicable to the analysed review or as a 0 when the criterion was not fulfilled, not applicable to the analysed review, or could not be answered based on the information provided by the review. As a consequence, the total quality score for each included review ranged from 0 to 11. The quality of the review was labeled as weak (score ranging from 0 to 3), moderate (score ranging from 4 to 7), or strong (score ranging from 8 to 11).

Results

SLRs and MAs selection process

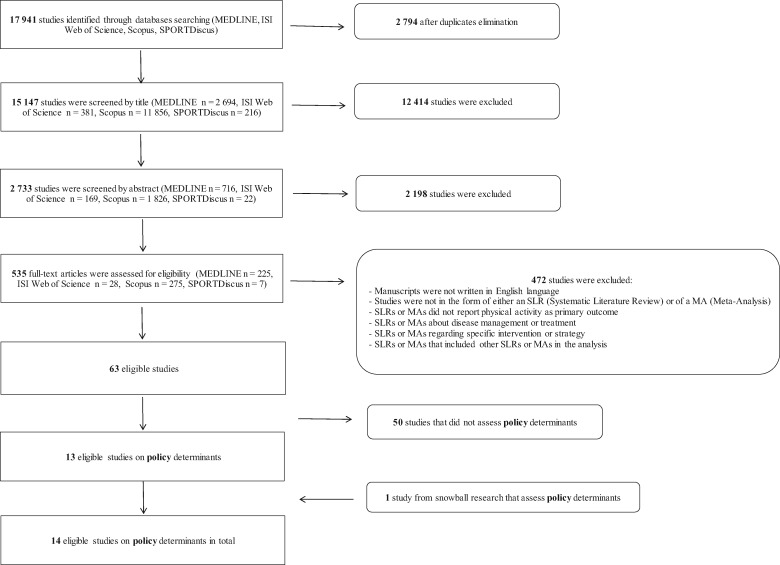

As summarized in figure 1, the systematic search identified a total number of 17 941 studies that were potentially relevant for inclusion in the seven umbrella SLRs. After the removal of duplicates, 15 147 studies remained for screening. After reading title and abstract, 12 414 and 2198 studies were, respectively, excluded because they did not meet the inclusion criteria. Thus, a total number of 535 full-text articles were assessed for eligibility. After the full-text reading phase, a further 472 studies were removed because they did not meet the inclusion criteria resulting in 63 eligible studies. Of these, 50 studies did not include policy determinants of PA and were excluded. One further study was found as eligible from the snowball search of the references. Therefore, the final number of reviews included in the present umbrella SLR on policy determinants of PA was 14.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the literature search

Characteristics of the included reviews

The characteristics of the 14 included reviews are summarized in Supplementary material (Supplementary table S2). No MAs on policy determinants of PA were found. Since some of the reviews included primary studies that examined the associations between non-policy determinants and PA, not all the primary studies included in the individual SLRs were appraised in this umbrella SLR. Of the 14 reviews included, only one reported policy determinants in all its primary studies (n = 19).11 Most of the reviews included primary studies from multiple continents, mostly from North America (n = 52) and Europe (n = 26). Cross-sectional (n = 116) was the predominant study design used among the primary studies.6,11,22–32 Prospective and cohort studies (n = 15) were included in six reviews, either as the only eligible study design33 or as part of the included studies.6,22–24,26

Ten reviews referred to primary studies that included young people only. Among these, preschool children between 4 and 6 years old were assessed in two reviews,27,30 and children in six reviews.6,20,23,24,31,33 One review analysed children (5–12 years old) and adolescents (13–18 years old) together,28 while adolescents between 13 and 18 years old were studied in two reviews.6,32

Four reviews focused on adults. One review included in the umbrella SLR focused on African American adults between 18 and 50 years old and older than 50 years old,29 and another review only on rural women,25 while the remaining two considered the population as a whole.11,26

Measurements of PA

One hundred thirty-five primary studies are included in the 14 reviews included in this umbrella SLR. Among those, 59 studies (44%) from eight reviews used non-objective measurement methods of PA assessment (e.g. self-report, parental report and PA direct observation).6,23–27,30,33 Objective measurements of PA, either assessed by accelerometer or pedometer, were used in 19 of the eligible primary studies (14%), included in four of the included reviews.6,22,24,27 Two primary studies (1%) included in two reviews combined objective with non-objective measures of PA.6,33 Finally, 55 primary studies (41%) from five reviews did not report the exact number of the studies that used objective and non-objective measures.11,28–30,32

The majority of the included reviews evaluated PA as the primary outcome (n = 8),6,22,26,27,29,30,32,33 as reported in table 1. Two reviews reported on measured PA behavior,11,25 two reviews measured MVPA (moderate to vigorous physical activity),24,27 and one review reported on measured habitual PA and acute PA (i.e. a PA single bout).23 Other reviews considered proxy measures of PA, including outdoor and free play,24 recess PA,28 and school break time PA and after-school PA.31 In reporting data, the authors agreed to merge ‘PA behavior’, ‘habitual PA’, and proxy measures of PA with PA as primary outcomes, and to report as ‘overall PA’ (table 2).

Table 1.

Results of the 14 reviews included in the umbrella SLR

| Author, date (type of review) [Ref] | Outcome(s) | Determinant(s) | Review aim | Overall descriptive results of the review | Overall quantitative results of the review | Overall limitations of the studies | Overall recommendations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gray C, 2015(SLR)23 | Habitual PA; Acute PA | Time spent outdoors | To systematically review and evaluate the evidence on the relationship between outdoor time and PA in children aged 3–12 | Outdoor time is positively related to PA in children aged 3–12; positive findings were apparent across ages, sexes, and contexts (e.g. preschool, PE, leisure time) | N.A. | Heterogeneity in the measurement of outdoor time and outcome variables across the included studies; inclusion of studies from developed nations | It is important to preserve time in children's schedules for unstructured outdoor play and to incorporate time outdoors within structured contexts like school and childcare as means of promoting healthy active living |

| Maitland C, 2013(SLR)24 | Outdoor/free play; MVPA time | PA-related home policies (rules, control) | To review the influence of the home physical environment on children’s PA and sedentary behaviour | Evidence for a positive association between PA home related rules and PA | N.A. | Lack of objective assessment and of investigations of the indoor home space beyond equipment; paucity of studies investigating objectively measured sedentary time and home contact specific behaviours | Family rules are of particular interest as they present an avenue for controlling the influence of the physical environment through not allowing screens in bedrooms and living areas or choosing not to purchase media equipment. They may also restrict or encourage the use of home space for active behaviours. Thus far few studies have explored these relationships, and further research is needed. |

| Olsen JM, 2013(SLR)25 | PA behaviour | Work hours | To identify factors that influence PA levels in rural women | Rural women have been found to be less active and experience more barriers to PA than urban women; work hours were identified as a barrier to PA | N.A. | Evaluation of data and analysis was done by one reviewer only; the terms ′rural′ and ′PA′ were inconsistently defined among studies; exclusion of articles studying women outside USA | Additional research that clearly defines and consistently applies the terms rural and PA is needed to strengthen knowledge in this area |

| Brown DR, 2012(SLR)26 | PA | Mass media campaigns | To determine the effectiveness of stand-alone mass media campaigns to increase PA at the population level | Insufficient evidence to determine effectiveness for stand-alone mass media campaigns for increasing PA | N.A. | Heterogeneity in methods (e.g. intensity, duration, population targeted, control and comparison conditions) and outcome measures limited cross-study comparisons; primary reliance on self-reported PA outcome measures that were not validated | Further research on campaign intensity, dose, reach, and duration in influencing behaviour change; on other important outcomes related to benefits, harms, cost-effectiveness, and applicability of findings; Without stronger evidence for their effectiveness, such campaigns may better be used as part of broader multicomponent community-wide intervention to increase awareness and knowledge about the benefits of PA |

| De Craemer M, 2012 (SLR)27 | PA; MVPA | PA-related home policies (rules, control); Parenting styles; Time spent outdoors; Community support at school; PA-related school policies; Recess duration; Class size; Preschool/School quality; Teacher education | To systematically review the correlates of PA, sedentary and eating behaviour in preschool children 4–6 years old | Inverse correlation between having play roles (e.g. staying close to the house, no balls in the house) and overall PA; Higher levels of MVPA were associated with more field trips, and higher education of the teacher; lower levels of MVPA were associated with bigger class size, more time outdoors at school; Lower levels PA during recess were associated with longer recess duration | N.A. | Some limitations regarding the coding of the association of the variables; several studies included wider age-range | Future studies should investigate similar correlates of PA, sedentary behaviour and eating behaviour to develop more effective interventions; Strategies should target both boys and girls, all ethnic groups, and parents of both low and high SES; especially on weekdays, should be a focus on maintaining the level of PA and decreasing the level of sedentary behaviour; on weekends, the focus should be on increasing the level of PA |

| Ridgers ND, 2012(SLR)28 | Recess PA | PA school policy; PA program involvement at school; Organized activities; School-based PE; Recess characteristics; Class size | To examine the correlates of children’s and adolescent’s PA during school recess periods | Inconclusive association between recess duration (typically determined by school PA) and PA; inconclusive association between recess periods and PE in children with special education needs | N.A. | The majority are small-sized and cross-sectional studies; MA is difficult to obtain given the limited number of studies that report effect sizes and the lack of consistency between them; use of a range of PA measures; lack of uniform definitions of recess | More research is needed concerning correlates of PA in recess period, particularly in adolescents; Schools are recommended to increase overall facility provision, to provide unfıxed equipment and to identify methods to increase social support, particularly by peers, to benefit children's and adolescent's PA during recess |

| Stanley AM, 2012(SLR)31 | School break time PA; After-school PA | PA school policy; Organized activities; Recess duration; | To identify the correlates of school break time PA and after-school PA in children 8–14 years | One study provided evidence of positive association between the provision of programs/activities and school break time PA | N.A. | Small number of studies that varied in methodological aspects; possibility that some studies are missed during the search process; majority of cross-sectional studies; narrow age range | Need of high quality evidence upon which PA promotion in young people can be tailored to specific settings and contexts; It is important to focus the attention on context- and setting- specific PA among young people |

| Siddiqi Z, 2011(SLR)29 | PA | Work hours; Inflexible work environment | To systematically examine and summarize factors impacting PA among African American adults | Long working hours as impediments to PA in both women and men aged 18–50 years | N.A. | Inclusion of qualitative studies only; possibility of publication bias; many included studies included only women | Further research is needed to assess the differences on PA levels among different ethnic groups; To effectively promote PA among African Americans, targeted interventions will need to address impediments at multiple levels |

| Sleddens EFC, 2011(SLR)22 | PA | Parenting styles | To synthesize evidence regarding the influence of general parenting on children's diet and activity behaviours, and weight status | The cross-sectional studies reported inconsistent results regarding parenting-PA relationship; findings of the longitudinal studies indicated that authoritative parenting was a positive predictor of PA | N.A. | Lack of measurement tools assessing the broad range of controlling dimension and differences in conceptualization of parenting constructs that may limit study comparisons | Additional research to further study the influence of mediating and moderating factors influencing the general parenting-child weight relationship; need to conduct determinant studies in diverse ethnic samples and age groups; larger samples of fathers should be included to allow comparisons with mothers;Intervention developers are recommended to increase their attention to the family context by creating authoritative environments characterized by parental encouragement of instrumental competence in children |

| Craggs C, 2011(SLR)33 | PA | PA-related home policies (rules, control) | To systematically review the published evidence regarding determinants of change in PA in children and adolescents | Indeterminate association between rules for PA and PA in children aged 10–13 years | N.A. | The heterogeneity in study samples, exposure, and outcome measures limit the ability to draw conclusions | Future research should aim to comprehensively assess potential determinants of PA in youth across all domains of the ecologic model, utilizing validated constructs and objectively measured PA, especially in younger children; further research focused on age-specific tendencies is also needed |

| Hinkley T, 2008(SLR)30 | PA | PA-related home policies (rules, control); Time spent outdoors; Community support at school; PA-related school policies; Class size; Preschool/School quality; Teacher education | To comprehensively investigate the correlates of preschool children’s PA | Children who spend more time in outdoor play spaces are more active than children who spend less time outdoors | N.A. | Small number of studies in preschool children up to date; small and varied sample sizes and potentially non-representative samples, as well as small variability in PA; measurement and analysis tools may not be sensitive enough; MA is impossible given the variety of effect-sizes | Simultaneous investigation of multiple variables across multiple domains may assist in the identification of potential mediating, moderating, or confounding influences on preschool children’s PA; the use of larger samples may allow for the detection of small yet significant associations |

| Van der Horst K, 2007 (SLR)32 | PA | School-based PE | To summarize and update the literature on correlates of young people's PA, insufficient PA, and sedentary behaviour | Positive association between PE/school sports and PA among adolescents | N.A. | Publication bias may be present; possibility of missed studies as a result of the search strategy; the main outcome was overall PA without other classifications; mostly cross-sectional studies included; because of the variability, it was not possible to assess the overall strength of the associations | More prospective studies are needed to gain and more insight into the determinants of change in PA levels or the decline in PA in adolescence; further research is needed on the determinants of PA in children; To achieve substantial behaviour change, preventive interventions should target changes in important determinants from different categories (social, psychological, and environmental) simultaneously |

| Ferreira I, 2006(SLR)6 | PA | PA-related home policies (rules, control); Parenting styles; Time spent outdoors; Community support at school; PA-related school policies; School-based PE; Class size; Preschool/School quality; School type; Health education | To systematically review the environmental correlates of PA in children and adolescents | At the home level, time spent outdoors (PA-related home policies) was consistently associated with higher PA levels of children, whereas parenting styles were unrelated to children's PA; Parenting styles were unrelated to adolescents' PA; At the school level, a positive association between PA-related school policies and children's PA levels was shown by 60% of the included studies; The type of school attended was positively associated, while the provision of instruction on PA and special PE programs were unrelated to adolescents' PA | N.A. | The search terms used to retrieve studies may have not been sensitive enough; the use of English studies only; the exclusion of studies from non-market economies; the main outcome was any form of PA; the used conceptual framework may have led to disputable categorization of correlates of PA | Future studies that use prospective and interventions designs are in great need; it is important to conduct further research with clear, possibly standardized, definitions and objective methods of environmental attributes and PA behaviour assessment; Multilevel intervention should target school-base PA policies and time spent outdoors as potential determinant in children's PA, and attendance of non-vocational schools as a potential determinant of adolescents' PA; the other variables should not be discarded without further investigation |

| Heath GW, 2006(SLR)11 | PA behaviour | Community-scale urban design and land use policies; Street-scale urban design and land use policies; Transportation and travel policies | To review studies addressing environmental and policy strategies to promote PA | Sufficient evidence that community-scale urban design and land use policies can be effective in increasing walking and bicycling; Sufficient evidence that street-scale urban design and land use policies to support PA in small geographic areas is effective in increasing levels of PA; Insufficient evidence to determine the effectiveness of transportation and travel policies in increasing PA | N.A. | Heterogeneity in measurement methods, urban design and land use characteristics, and level of interaction between the social and physical environment | Further research on the economic aspects of the interventions; Practitioners are recommended with strong evidence to create an enhanced access to places for PA combined with informational outreach activities |

Note: MA, meta-analysis; MVPA, moderate to vigorous physical activity; N.A., not applicable; PA, physical activity; PE, physical education; SLR, systematic literature review.

Table 2.

Summary of the results of the 14 included reviews in terms of importance of determinants and strength of evidence

| Determinant | Preschool children (overall PA) | Preschool children (MVPA) | Children (overall PA) | Children (MVPA) | Children (acute PA) | Children and adolescents (overall PA) | Adolescents (overall PA) | Adults (overall PA) | Older adults (overall PA) | Whole population (overall PA) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PA-related home policies (e.g. rules, control) | −, Ls27,30 | 0, Lns27 | 0, Lns24,33 | 0, Ls24 | ||||||

| Parenting styles | 0, Lns27 | 0, Lns6,22 | 0, Lns6 | |||||||

| Time spent outdoors | ++, Ls27,30 | ++, Pe6,23 | ++, Pe23 | |||||||

| Community support at school | 0, Lns27,30 | 0, Lns6 | ||||||||

| PA school policy | 0, Lns31 | +, Ls28 | ||||||||

| PA program involvment at school | 0, Lns28 | |||||||||

| PA-related school policies (e.g. time allowed for free play/spent outside, # field trips) | ++, Ls30 | 0, Lns27 | +, Pe6 | |||||||

| Organized activities | +, Ls31 | 0, Lns28 | ||||||||

| School-based PE | 0, Lns28 | 0, Lns6,32 | ||||||||

| Recess duration | −, Ls27 | 0, Lns31 | 0, Lns28 | |||||||

| Number of daily recess periods | 0, Lns28 | |||||||||

| Class time vs. recess | −, Ls28 | |||||||||

| Fitness break vs. recess | +, Ls28 | |||||||||

| Morning vs. lunchtime recess | 0, Lns28 | |||||||||

| PE vs. recess | 0, Lns28 | |||||||||

| Class size | 0, Lns30 | −, Pe27 | 0, Lns6 | 0, Lns28 | ||||||

| Preschool/School quality | 0, Lns30 | 0, Lns27 | 0, Lns6 | |||||||

| School type (high school vs. vocational/alternative) | +, Pe6 | |||||||||

| Health education | 0, Lns6 | |||||||||

| Teacher education | +, Ls30 | +, Ls27 | ||||||||

| Work hours | −, Ls25,29 | |||||||||

| Inflexible work environment | −, Ls29 | −, Ls29 | ||||||||

| Street-scale urban design and land use policies | ++, Ls11 | |||||||||

| Transportation and travel policies | 0, Lns11 | |||||||||

| Program availability at church/community | +, Ls29 | +, Ls29 | ||||||||

| Community-scale urban design and land use policies | ++, Ls11 | |||||||||

| Mass media campaigns | 0, Lns26 |

Note: Ce, convincing evidence; Lns, limited, no conclusive evidence; Ls, limited, suggestive evidence; Pe, probable evidence; PA, physical activity; MVPA, moderate to vigorous physical activity.

Categorization of the included policy determinants of PA

The policy determinants of PA included in the present umbrella SLR are listed in the Supplementary material (Supplementary table S3). In the preparation phase, a total number of 55 policy determinants of PA were identified. Among those, either duplicates or very close constructs were merged into broader determinants. For example, determinants such as ‘family rules’, ‘play rules’, ‘rules for PA and sedentary activities’ and ‘rules prohibiting television viewing’ were merged into a single determinant ‘PA-related home policies (e.g. rules, control)’. Further 10 determinants were considered separately because an aggregation was not feasible (e.g. ‘PA program involvement at school’, ‘School type (vocational vs. alternative high school)’, ‘Teacher education’, ‘Work hours’, ‘Inflexible work environment’, ‘Street-scale urban design and land use policies’, ‘Transportation and travel policies’, ‘Program availability at church/community’, ‘Community-scale urban design and land use policies’ and ‘Mass media campaigns’). Five additional determinants (‘Number of daily recess periods’, ‘Class time vs. Recess’, ‘Fitness break vs. Recess’, ‘Morning vs. lunchtime recess’ and ‘Physical education (PE) vs. Recess’) were considered separately, even if broadly reported as ‘Recess characteristics’ in table 3.

Table 3.

Quality assessment of the 14 included reviews using the AMSTAR checklist

| Author, date [Ref] | Was an ‘a priori’ design provided? | Was there duplicate study selection and data extraction? | Was a comprehensive literature search performed? | Was the status of publication (i.e. grey literature) used as an inclusion criterion? | Was a list of studies (included and excluded) provided? | Were the characteristics of the included studies provided? | Was the scientific quality of the included studies assessed and documented? | Was the scientific quality of the included studies used appropriately in formulating conclusions? | Were the methods used to combine the findings of studies appropriate? | Was the likelihood of publication bias assessed? | Was the conflict of interest included? | Sum quality scorea | Quality of the reviewb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gray C, 2015 (SLR)23 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | N.A. | Yes | Yes | 9 | Strong |

| Maitland C, 2013 (SLR)24 | No | No | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | N.A. | No | No | 3 | Weak |

| Olsen JM, 2013 (SLR)25 | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | N.A. | No | C.A. | 4 | Moderate |

| Brown DR, 2012 (SLR)26 | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | N.A. | No | No | 5 | Moderate |

| De Craemer M, 2012 (SLR)27 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | N.A. | N.A. | No | Yes | 4 | Moderate |

| Ridgers ND, 2012 (SLR) [28] | Yes | C.A. | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. | Yes | 4 | Moderate |

| Stanley AM, 2012 (SLR)31 | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | N.A. | No | Yes | 4 | Moderate |

| Siddiqi Z, 2011 (SLR)29 | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | N.A. | No | Yes | 6 | Moderate |

| Sleddens EFC, 2011 (SLR)22 | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | 6 | Moderate |

| Craggs C, 2011 (SLR)33 | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | N.A. | No | Yes | 6 | Moderate |

| Hinkley T, 2008 (SLR)30 | Yes | Yes | Yes | N.A. | No | No | No | No | N.A. | No | Yes | 4 | Moderate |

| Van der Horst K, 2007 (SLR)32 | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | N.A. | N.A. | No | No | 3 | Weak |

| Ferreira I, 2006 (SLR)6 | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | Yes | 5 | Moderate |

| Heath GW, 2006 (SLR)11 | Yes | C.A. | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | N.A. | No | No | 6 | Moderate |

Note: C.A., can't answer; N.A., not applicable.

0 when the criteria was not applicable for the included review; 1 when the criteria was applicable for the included review.

Weak (score ranging from 0 to 3); Moderate (score ranging from 4 to 7); Strong (score ranging from 8 to 11).

Thus, a final list of 27 policy determinants of PA was considered in the present umbrella SLR. The determinants were also grouped into the micro and macro environmental settings as defined by the the ANalysis Grid for Elements Linked to Obesity (ANGELO), with a further distinction in specific levels (e.g. home/household, educational institutions, workplaces, neighborhoods and city/municipality/regions)10 (Supplementary table S1).

Summary of the results of the included reviews by importance of determinants and strength of evidence

Table 2 summarizes the results of the associations between the investigated policy determinants and PA, considering different age groups and different types of PA.

Preschool children

Two out of the 14 included reviews specifically assessed the policy determinants of PA behavior in preschool children between 4 and 6 years old.27,30 At the home level, time spent outdoors was positively related to overall PA in all the studies included in the reviews, without exception, with a limited and suggestive level of evidence ( ++, Ls).27,30PA-related home policies were negatively related to overall PA in >75% of the reviews with a limited and suggestive level of evidence (−, Ls),27,30 while limited and no conclusive evidence was found in relation to MVPA.27 At the school level, PA-related school policies were positively related to overall PA in all the studies included in the review, without exception, with a limited and suggestive level of evidence ( ++, Ls),30 while limited and no conclusive evidence was found in relation to MVPA.27 A negative association was found in >75% of the primary studies included in the review, also with a limited and suggestive level of evidence, between recess duration and overall PA during recess (−, Ls).27Teacher education appeared to be positively associated with overall PA and MVPA in >75% of the primary studies included in the review with a limited and suggestive level of evidence (+, Ls),27,30 and no association was reported between both class size and overall PA26 and preschool quality and overall PA and MVPA.27,30

Children

Among the 14 included reviews, six studied the policy determinants of PA in children from the age of 3 to the age of 12.6,22–24,31,33 At the home level, time spent outdoors was positively related to both overall PA,6,23 and acute PA23 in all the studies included in the reviews, without exception, with a probable level of evidence ( ++, Pe). Mixed and inconsistent results were found in regard to PA-related home policies, thus giving limited and no conclusive evidence of its relation with both overall PA (0, Lns)24,33 and MVPA (0, Ls).24 Inconclusive results were also revealed for parenting styles as a potential determinant of overall PA (0, Lns).6,22 At the school level, PA-related school policies and organized activities were positively related to overall PA in the majority of the studies included in the review, the first with a probable level of evidence (+, Pe),6 while the second with a limited and suggestive level of evidence (+, Ls).31

Children and adolescents

One review only examined the policy determinants of overall PA during school recess in children (5–12 years old) and in adolescents (13–18 years old) considered together.28PA school policy (assessed as presence of a written PA school policy) was positively associated with overall PA levels during recess in >75% of the studies included in the review with a limited and suggestive level of evidence (+, Ls). Inconclusive findings were found concerning the recess duration (0, Lns). However, it appeared that class time vs. recess was negatively associated with overall PA (−, Ls) and that fitness break vs. recess was positively associated with overall PA (+, Ls).

Adolescents

The policy determinants of PA among adolescents were investigated by two reviews.6,32 At the home level, no conclusive association was found between parenting styles and overall PA (0, Lns).6 At the school level, a probable evidence of positive association was shown between school type and overall PA in all the studies included in the review, without exception, ( ++, Pe).6

Adults

One review examined the policy determinants of PA among African American adults aged over 18 years old,29 and another review assessed the determinants of PA among rural women.25 Long work hours was revealed to be negatively related to overall levels of PA with a limited and suggestive level of evidence (−, Ls) in both African American adults29 and rural women.25 In the African American adult population, also an inflexible work environment was negatively associated with overall PA with a limited and suggestive level of evidence (−, Ls),29 while the program availability at church/community was instead positively associated with overall PA with a limited and suggestive level of evidence (+, Ls).29

Older adults

One review examined the policy determinants of PA among African American older adults aged over 50 years old.29 Similarly to the results obtained in the adult group, a negative association was revealed between an inflexible work environment and overall PA levels (−, Ls), and a positive association between the program availability at church/community and overall PA levels (+, Ls).

Whole population

Policy determinants of PA across all age groups were studied by two reviews.11,26Street-scale urban design and land use policies and community-scale urban design and land use policies were both positively associated with overall PA in the population in all the studies included in the reviews, without exception, with a limited and suggestive level of evidence ( ++, Ls).11For transportation and travel policies,11 and for mass media campaign,22 the evidence was limited and inconclusive; no association with overall PA levels can be stated (0, Lns).

Evaluation of the quality of the SLRs

The results of the quality assessment using the AMSTAR checklist are reported in table 3. Among the 14 included reviews, the majority were evaluated as being of moderate quality (n = 11),6,11,22,25–31,33 two as weak,24,32 and only one as strong.23 Among those reviews of moderate quality, five were scored with four points,25,27,28,30,31 two with five points,6,26 and four with six points.11,22,29,33

Discussion

The aim of this umbrella SLR was to summarize current evidence on policy determinants of PA across the life course and to evaluate their importance, strength of the evidence, and methodological quality. This systematic collection of evidence relating to policy determinants of able to promote or hinder PA levels took into account the available SLRs of the last 12 years as a first step towards the development of effective health-enhancing approaches.

To date, very few SLRs and no MA have investigated solely the policy determinants of PA. The majority of the reviews included in this umbrella SLR (13 out of 14) analysed policy determinants as a category of environmental determinants of PA, and only one review focused on policies and practices related to PA behavior.11 To our knowledge, this is the first umbrella SLR that grouped the current available evidence on the policy determinants of PA from 135 primary studies summarized in 14 reviews.

The majority of current data on policy determinants of PA has been collected on children and adolescents, with 10 reviews out of 14 analyzing the impact of strategies in increasing PA levels in youth. Several reasons explain this interest on PA levels in the youngest. First, PA levels in youth tend to track into adulthood, and PA promotion in youth is thought to facilitate healthful habits into adulthood and to enhance a lifelong protection from other risk factors.6 Second, political environmental influences are especially relevant to children and adolescents because they have less autonomy in their behavioral choices than adults.34 Last, considering the policy dimension of the environmental domain, children and adolescents are more subjected to the rules at the home level (e.g. parental control on time spent outdoors, television viewing time) and at the school level (e.g. non-curricular time).

At the home level, having playing rules, such as staying close to the house, or not playing in the house, was negatively associated with PA in preschool children,27,30 while time spent outdoors was consistently found to be positively associated with PA in preschool children27,30 and in children.6,23 The evidence of this associations was convincing in children6,23 and suggestive but limited in preschool children.27,30 This finding highlights the importance of preserving time for unstructured outdoor play in children aged 3–12 years, as well as to incorporate time outdoors within organized contexts such as school, more and more oriented towards structured indoor achievement oriented activities.23,35

The importance of time for free and outdoor play in preschool children and children emerged also at the school level.6,30 PA-related school policies, for example, time allowed to free play, time spent outdoors, and the number of field trips, appeared to be consistently positively associated with PA in preschool children and in children. The evidence that children allowed to spend more time in school outdoor spaces are more active than children not allowed is sufficient strength to confirm the importance of unstructured free time in children also at the preschool and school levels. Non-curricular time, such as school recess periods and afterschool programs, provides additional opportunities for children to be physically active within the school environment.36 Several determinants of PA during recess in preschool children27 and in children28,31 have been investigated by three of included reviews. It emerged that a longer recess duration is associated with lower levels of PA in preschool children probably due to the fact that children show a burst of activity when they first go outside, which decreases with time because of fatigue or getting bored.37,38 Efforts in preschool recess management are required, with more than one recess periods per day being preferable in order to allow children to play freely. Evidence for recess duration as a determinant of PA in children29 and adolescents28 was mixed, thus insufficient to draw final conclusions, highlighting the need of a greater understanding of the impact of school recess duration in youth.

Adolescents that attend vocational high schools appeared to be more physically active than adolescents attending alternative high schools that serve one gender or that have a predominant ethnic group.6 Alternative high schools should in turn develop and implement programs that emphasize risk behaviors that occur most often in their students.39 Mixed findings were found with regards to the provision of school-based PE programs, thus indicating it to be unrelated to PA in the adolescents6,32 and in children and adolescents altogether.28

To date, very few studies have investigated environmental policy determinants of PA in adults, and the two reviews included in this umbrella SLR provide the sum of the knowledge available in the literature, with a particular focus on differences in PA levels on at-risk populations.25,29 The work environment emerged to be a source of policy determinants, with long working hours being negatively associated with PA among rural women25 and African American adults.25 Long working hours and an inflexible work environment were negatively associated with PA levels also in African American adults and older adults, whereas program availability at the community and church setting were positively associated with PA levels.29 From these findings, it emerges the need for targeted occupational policies to promote PA in vulnerable populations by taking into account both the socio-cultural background and the working environment.

In addition to individual health promotion policies specific for age, gender, and ethnic groups, increasing PA at the population level can have substantial improvements in public health. Environmental and policy approaches designed to create supportive environments and organizational structures have been systematically reviewed by Heath et al.,11 while the effectiveness of stand-alone mass media campaigns to increase PA at the population level have been described by Brown et al.26 There is a consistent but limited evidence that street-scale urban design and land use policies (micro-environment level) and community-scale urban design and land use policies (macro-environment level) are positively associated with higher levels of PA.11 The evidence suggests the need of inter-sectorial interventions in urban planning able to improve access, safety and attractiveness of neighborhoods (e.g. redesigning access, safety and aesthetics of streets and sidewalks) and cities [e.g. policies oriented at ameliorating sidewalk quality and connectivity, in addition to the promotion of mixed land use (i.e. proximate residential and commercial areas)]. However, the small number of primary studies is unable to provide sufficient evidence in support of the effectiveness of transportation and travel policies, and practices aimed at improving pedestrian and cyclist activity and safety and at reducing car use, highlighting the need of greater research. Modest and inconsistent findings were also shown in regards to the effectiveness of stand-alone mass media campaigns, defined as interventions that rely on mass media channels to deliver messages about PA to large and relatively undifferentiated audiences, for increasing PA.26

This umbrella SLR evaluated policy determinants of PA at individual-level and population-level, relying on all available literature evidence. However, given the heterogeneity of the existing primary studies and SLRs, some limitations of the current umbrella SLR emerged. First, the diversity in research design, population groups, measurement techniques, determinants investigated, and PA outcome across the literature makes it difficult to evaluate the evidence, perform appropriate MAs (none was indeed found) and to draw appropriate conclusions.40 Among the included reviews, the majority included cross-sectional primary studies, thus limiting the strength of the evidence, with very few policy determinants receiving a probable level of evidence and with none receiving a convincing level of evidence. Second, the age range that constitutes each age group often varies in different reviews/studies, and this issue is particularly prominent in the children and adolescents population, thus limiting the capacity of properly discriminating the age categories. Third, non-objective measurement methods of PA assessment were mostly used, providing less accurate estimates of PA levels than those obtained through objective measurements. Last, the determinants investigated and the PA outcome evaluated were both heterogeneous in terms of assessment and of terminology, leading the authors to create groups and categories that could cause a loss of information.

Nonetheless, this umbrella SLR provides evidence on several modifiable policy determinants of PA that may serve as a first step towards the development and implementation of multi- and inter-sectorial interventions. At the individual level, the concept of rules limiting the time for PA emerged as fundamental: parents and schools should acknowledge the importance of unstructured free time spent outdoors in children, while the amount of working hours should be re-set, taking into consideration the socio-cultural background for a more PA conducive environment for adults. At the community level, there is limited evidence that a collaboration between policy makers and urban planners, architects, engineers, developers and public health professional, when planning to improve neighbourhoods and municipalities could increase PA in the population.

In conclusion, it is important to stress the need for future investigations for policy determinants of PA for which this SLR was not able to provide clear evidence or draw conclusions, preferably by using prospective study designs, standardized definitions of PA and objective measurement methods of PA assessment.

Supplementary data

Supplementary data are available at EURPUB online.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Lien N, Lakerveld J, Mazzocchi M, O’Gorman D, Monsivais P, Nicolaou M, Renner B, Volkert D and the DEDIPAC-KH Management team for their helpful support.

They also thank the MIUR (Italian Ministry of Instruction, University and Research, DEDIPAC F.S. 02.15.02 COD. B84G14000040008; and CDR2.PRIN 2010/11 COD. 2010KL2Y73_003), Federal Ministry of Education and Research, Germany (Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung, Förderkennzeichen 01EA1377, 01EA1372C and 01EA1372E), the Health Research Board, Ireland, and the Institut National de la Recherche Agronomique (INRA), Institut National de Prévention et d’Education pour la Sante (INPES) for funding this work within the project entitled ‘Determinants of Diet and Physical Activity; Knowledge Hub to integrate and develop infrastructure for research across Europe’ (DEDIPAC KH).

Funding

This work was supported by the MIUR (Italian Ministry of Instruction, University and Research, DEDIPAC F.S. 02.15.02 COD.B84G14000040008; and CDR2.PRIN 2010/11 COD.2010KL2Y73_003), the Federal Ministry of Education and Research, Germany (Bundesministerium fur Bildung und Forschung, Forderkennzeichen 01EA1377, 01EA1372C and 01EA1372E), the Health Research Board, Ireland, the Institut National de la Recherche Agronomique (INRA), the Institut National de Prevention et d’Education pour la Sante (INPES).

Conflicts of interest: None declared.

Key points

To date, very few systematic literature reviews (SLRs) and no meta-analyses (MAs) have investigated solely the policy determinants of physical activity (PA).

The majority of current data on policy determinants of PA has been collected on children and adolescents, while very few studies have investigated policy determinants of PA in adults.

None of the investigated policy determinants had a convincing level of evidence, and very few had a probable level of evidence, due to the inconsistency of the results among reviews, the quality of the individual studies and the lack of accuracy in the assessment methods used in the individual studies.

The most convincing evidence resulting from this umbrella SLR lays the foundation to preserve time for unstructured outdoor play in children, as well as to incorporate time outdoors within organized contexts such as school.

Further research with the use of prospective study designs, standardized definitions of PA and objective measurement methods of PA assessment is recommended.

References

- 1.WHO | Physical activity. WHO Fact Sheet. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2016. (15 March 2016, date last accessed).

- 2. Hallal PC, Andersen LB, Bull FC, et al. Global physical activity levels: surveillance progress, pitfalls, and prospects. Lancet 380:247–57. Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22818937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. World Health Organization (WHO). Global Recommendations on Physical Activity for Health [Internet]. WHO Fact Sheet. 2010. Available at: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/44399/1/9789241599979_eng.pdf (25 May 2016, date last accessed) [PubMed]

- 4. Bauman AE, Reis RS, Sallis JF, et al. Physical activity 2 correlates of physical activity: why are some people physically active and others not? for the Lancet Physical Activity Series Working Group*. Lancet [Internet] 2012;380:258–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Sallis JF, Cervero RB, Ascher W, et al. An ecological approach to creating active living communities. Annu Rev Public Health [Internet] 2006;27:297–322. Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16533119 (30 May 2016, date last accessed). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ferreira I, Van Der Horst K, Wendel-Vos W, et al. Environmental correlates of physical activity in youth: a review and update. Obes Rev 2007;8:129–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Condello G, Ling FCM, Bianco A, et al. Using concept mapping in the development of the EU-PAD framework (EUropean-Physical Activity Determinants across the life course): a DEDIPAC-study. BMC Public Health [Internet] 2016;16:1145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Glass TA, McAtee MJ. Behavioral science at the crossroads in public health: extending horizons, envisioning the future. Soc Sci Med [Internet] 2006;62:1650–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ooms L, Veenhof C, Schipper-van Veldhoven N, et al. Sporting programs for inactive population groups: factors influencing implementation in the organized sports setting. BMC Sports Sci Med Rehabil 2015;7:12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Swinburn B, Egger G, Raza F. Dissecting obesogenic environments: the development and application of a framework for identifying and prioritizing environmental interventions for obesity. Prev Med 1999;29:563–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Heath GW, Brownson RC, Kruger J, et al. The effectiveness of urban design and land use and transport policies and practices to increase physical activity: a systematic review. J Phys Act Health 2006;3:55–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kumanyika SK, Obarzanek E, Stettler N, et al. Population-based prevention of obesity: The need for comprehensive promotion of healthful eating, physical activity, and energy balance: A scientific statement from American Heart Association Council on Epidemiology and Prevention, Interdisciplinary Commi. Circulation 2008;118:428–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. European Commission. EU Joint Programming Initiative a Healthy Diet for a Healthy Life; 2013. Available at: http://www.healthydietforhealthylife.eu.

- 14. Lakerveld J, van der Ploeg HP, Kroeze W, et al. Towards the integration and development of a cross-European research network and infrastructure: the DEterminants of DIet and Physical ACtivity (DEDIPAC) Knowledge Hub. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2014;11:143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Cortis C, Puggina A, Pesce C, et al. Psychological determinants of physical activity across the life course: A " DEterminants of DIet and Physical ACtivity" (DEDIPAC) umbrella systematic literature review. Buchowski M, editor. PLoS One 2017;12:e0182709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Condello G, Puggina A, Aleksovska K, et al. Behavioral determinants of physical activity across the life course: a “DEterminants of DIet and Physical ACtivity” (DEDIPAC) umbrella systematic literature review. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2017;14:58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Carlin A, Perchoux C, Puggina A, et al. A life course examination of the physical environmental determinants of physical activity behaviour: a “Determinants of Diet and Physical Activity” (DEDIPAC) umbrella systematic literature review. PLoS One 2017;12:e0182083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. J Clin Epidemiol 2009;62:e1–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Capranica L, Donncha C, Mac, Puggina A PROSPERO International prospective register of systematic reviews. Determinants of physical activity : an umbrella systematic literature review. 2015;1–5. Available at: http://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/display_record.asp?ID=CRD42015010616.

- 20. Sleddens E, Kroeze W, Kohl L, et al. Determinants of dietary behavior among youth: an umbrella review. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2015;12:7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Shea BJ, Grimshaw JM, Wells G. a, et al. Development of AMSTAR: a measurement tool to assess the methodological quality of systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol 2007;7:10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Sleddens EFC, Gerards SMPL, Thijs C, et al. General parenting, childhood overweight and obesity-inducing behaviors: a review. Int J Pediatr Obes [Internet] 2011;6:e12–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Gray C, Gibbons R, Larouche R, et al. What is the relationship between outdoor time and physical activity, sedentary behaviour, and physical fitness in children? A systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2015;12:6455–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Maitland C, Stratton G, Foster S, et al. A place for play? The influence of the home physical environment on children’s physical activity and sedentary behaviour. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2013;10:99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Olsen JM. An integrative review of literature on the determinants of physical activity among rural women. Public Health Nurs 2013;30:288–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Brown DR, Soares J, Epping JM, et al. Stand-alone mass media campaigns to increase physical activity: a community guide updated review. Am J Prev Med 2012;43:551–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. De Craemer M, De Decker E, De Bourdeaudhuij I, et al. Correlates of energy balance-related behaviours in preschool children: a systematic review. Obes Rev 2012;13:13–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ridgers ND, Salmon J, Parrish A-M, et al. Physical activity during school recess. Am J Prev Med 2012;43:320–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Siddiqi Z, Tiro J. a, Shuval K. Understanding impediments and enablers to physical activity among African American adults: a systematic review of qualitative studies. Health Educ Res 2011;26:1010–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hinkley T, Crawford D, Salmon J, et al. Preschool children and physical activity. Am J Prev Med 2008;34:435–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Stanley RM, Ridley K, Dollman J. Correlates of children’s time-specific physical activity: a review of the literature. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2012;9:50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Van Der Horst K, Paw MJCA, Twisk JWR, Van Mechelen W. A brief review on correlates of physical activity and sedentariness in youth. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2007;39:1241–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Craggs C, Corder K, van Sluijs EMF, Griffin SJ. Determinants of change in physical activity in children and adolescents. Am J Prev Med 2011;40:645–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Nutbeam D, Aar L, Catford J. Understanding childrens’ health behaviour: the implications for health promotion for young people. Soc Sci Med 1989;29:317–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Valentine G, McKendrck J. Children’s outdoor play: exploring parental concerns about children’s safety and the changing nature of childhood. Geoforum 1997;28:219–35. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Jago R, Baranowski T. Non-curricular approaches for increasing physical activity in youth: a review. Prev Med 2004;39:157–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Cardon G, Van Cauwenberghe E, Labarque V, et al. The contribution of preschool playground factors in explaining children’s physical activity during recess. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2008;5:11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. McKenzie TL, Sallis JF, Elder JP, et al. Physical activity levels and prompts in young children at recess: a two-year study of a bi-ethnic sample. Res Q Exerc Sport 1997;68:195–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Grunbaum JA, Lowry R, Kann L. Prevalence of health-related behaviors among alternative high school students as compared with students attending regular high schools. J Adolesc Health 2001;29:337–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Bauman AE, Sallis JF, Dzewaltowski DA, Owen N. Toward a better understanding of the influences on physical activity: the role of determinants, correlates, causal variables, mediators, moderators, and confounders. Am J Prev Med 2002;23(2 Suppl):5–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.