Abstract

Mutations of cysteine are often introduced to e.g. avoid formation of non-physiological inter-molecular disulfide bridges in in-vitro experiments, or to maintain specificity in labeling experiments. Alanine or serine is typically preferred, which usually do not alter the overall protein stability, when the original cysteine was surface exposed. However, selecting the optimal mutation for cysteines in the hydrophobic core of the protein is more challenging. In this work, the stability of selected Cys mutants of 14-3-3ζ was predicted by free-energy calculations and the obtained data were compared with experimentally determined stabilities. Both the computational predictions as well as the experimental validation point at a significant destabilization of mutants C94A and C94S. This destabilization could be attributed to the formation of hydrophobic cavities and a polar solvation of a hydrophilic side chain. A L12E, M78K double mutant was further studied in terms of its reduced dimerization propensity. In contrast to naïve expectations, this double mutant did not lead to the formation of strong salt bridges, which was rationalized in terms of a preferred solvation of the ionic species. Again, experiments agreed with the calculations by confirming the monomerization of the double mutants. Overall, the simulation data is in good agreement with experiments and offers additional insight into the stability and dimerization of this important family of regulatory proteins.

Keywords: 14-3-3 protein, Protein stability, Molecular dynamics simulation, Differential scanning calorimetry, Free energy calculation, Thermodynamic integration

1. Introduction

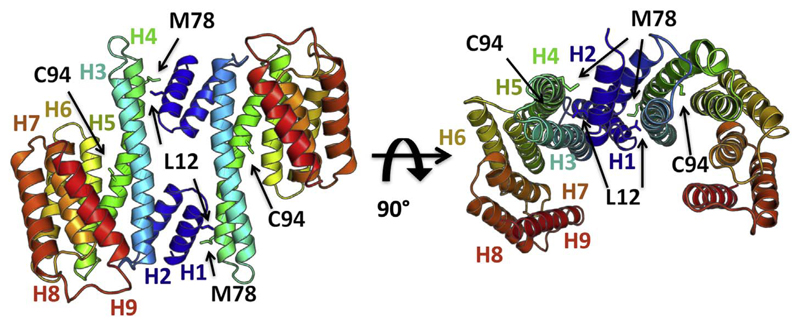

The 14-3-3 proteins form a family of acidic proteins with molecular weight of approximately 30 kD [1] ubiquitous in all eukaryotic organisms. There are seven highly conserved isoforms of the 14-3-3 family in mammals, two in yeast and fifteen in plants [2–4]. The 14-3-3 proteins function mostly as hetero and homo dimers [5,6], with each of the monomers consisting of nine antiparallel helices. The complete structure of the protein is shown in Fig. 1. The first four helices, starting from the N-terminus, create a hydrophobic dimer interface and the floor of the binding channel. The next 5 helices create the amphipathic interior of the peptide-binding channel [7,8]. Residues aligning the channel belong to the most highly conserved residues among all isoforms, while the sequence of the surface and flexible C-terminal residues is more diverse and responsible for isoform-substrate specificity [1,5,9].

Fig. 1.

14-3-3ζ protein with helices H1-H9 marked in one monomer and the mutated residues L12, M78 and C94 indicated in stick representation. The unstructured C-terminus (residues 229–245) was removed because of its high flexibility.

14-3-3 proteins play a key role in regulating intracellular signaling pathways, common cellular processes, primary metabolism, antiapoptotic pathways and cellular proliferation [10,11]. They act as adapters for > 200 binding partners by either allosteric modification of enzymes or controlling the assembly of protein complexes [12–16]. Among the best known 14-3-3 binding partners are tyrosine hydroxylase, Raf-1 (RAF proto-oncogene ser/thr-protein kinase), BCR (B-cell receptor), PKC (protein kinase C), MLK (mixed lineage ser/thr kinase), Tau protein or p53 (cellular tumor antigen p53) [16–18]. Their protein binding partners usually contain intrinsically disordered regions, typically containing motifs involving phosphoserine or phosphothreonine with a consensus sequence RSXpSXP (mode I) or RX[FY]XpSXP (mode II) [19]. Enhanced sampling molecular dynamics (MD) simulations of the phosphopeptides binding to 14-3-3ζ showed the presence of a dominant binding pathway, roughly following helix 3. In the process of phosphopeptide binding, 14-3-3ζ was observed to adopt a so-called “wide-opened” conformation that is not usually present in the apo or holo states [20]. 14-3-3 dimers contain two binding sites and are therefore able to accommodate also doubly-phosphorylated binding partners. In addition to the traditionally considered single partner with two phosphorylation sites occupying the individual binding cavities within the 14-3-3ζ dimer [21,22], two more major binding modes were confirmed by 31P NMR titration experiments [23].

In this paper, we focus on computational predictions of the stability of the 14-3-3ζ isoform upon mutations, using MD simulations and thermodynamic integration (TI) to compute free-energy differences. Our computational predictions are compared to experimentally determined melting temperatures (TM) as obtained from differential scanning calorimetry and to native gel electrophoresis experiments, as indirect measures of protein stability and dimerization [24]. While the thermodynamic stability as computed from our simulations is not expected to quantitatively correlate with TM, both are measures of stability of the protein [25]. A comparison of homologous proteins from mesophillic and thermophilic organisms e.g. reveals that for the majority of cases, the melting temperature is increased as the result of an increase of the unfolding free energy at the entire temperature range [26].

Mutations of cysteine may be introduced for multiple practical reasons. Cysteine contains a reactive sulfhydryl group, allowing for the formation of disulfide bridges. However, cysteines that are not involved in intramolecular disulfide bridges may be prone to unwanted oxidation or crosslinking under experimental conditions. On the other hand, various experimental methods make use of specific labels that are anchored to the protein (e.g. chromopohoric or spin labels) to gain insight into the function and dynamics of proteins. To maintain the specificity in labeling, other cysteines, naturally occurring in the sequence need to be replaced by other amino acids preferably without altering the overall protein stability. This is commonly done by a replacement by alanine or serine. While mutating the surface exposed single cysteines for alanines or serines usually does not alter the overall protein stability, it is much more complicated when mutating the cysteins in the hydrophobic core of the protein. The 14-3-3ζ protein contains three cysteines, of which two (Cys25 and Cys189) are located on the protein surface and their mutagenesis for the Ala has negligible impact on the protein stability [23]. The third, Cys94, is located in the central helix H4 and buried in a hydrophobic pocket, therefore its mutation influences the overall stability of the protein. Here, we investigate the possibility to propose protein mutants by MD simulations that would sustain or improve protein stability upon cysteine mutation and verify our results by experimental melting temperatures. Apart from the most common choices C94A and C94S, we have further considered three more hydrophobic mutants, C94I, C94L and C94V, based on the location of the residue in the hydrophobic core of the protein.

Further, we investigate a double mutation of Leu12 and Met78, which are located at the dimer interface and influence protein dimerization. In the 14-3-3ζ homodimer several salt bridges as well as buried polar and hydrophobic residues are engaged in the formation of a stable dimer interface [8]. The double mutant Leu12Glu/Met78Lys was identified to destabilise this interface and thereby hinder dimer formation while at the same time it does not change the overall charge of the 14-3-3ζ monomeric unit. As the mutations are in a position that would allow for stable salt bridges, a destabilization of the dimer interface seems somewhat counter intuitive. Here, our aim is to rationalize the experimental results by molecular simulations.

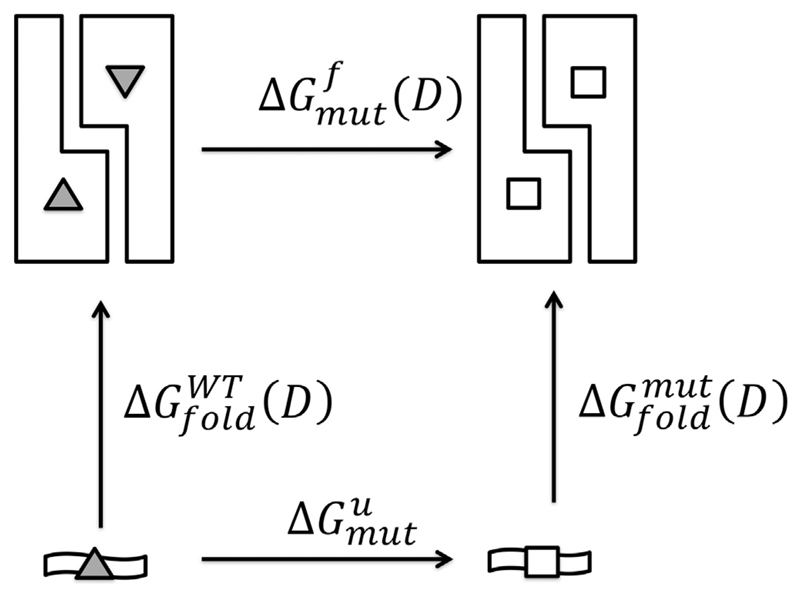

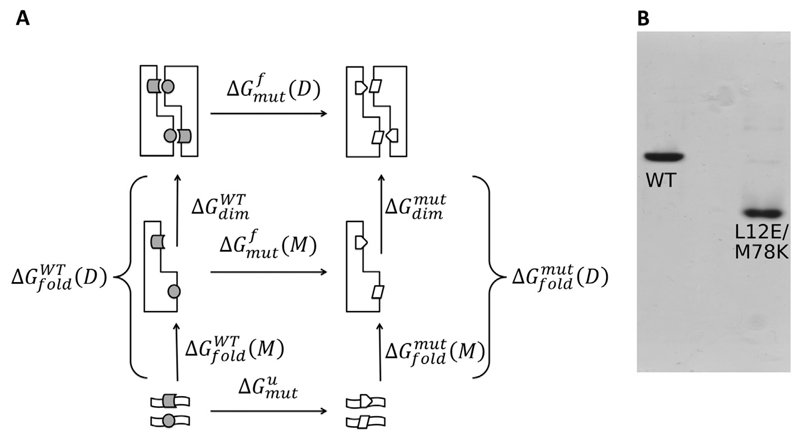

For the calculation of free energy differences, we make use of thermodynamic cycles. The one we use for the mutations of Cys94 can be seen in Fig. 2. In this figure, the dimeric 14-3-3ζ is indicated by two roughly L-shaped figures with the wildtype residue (Cys94) indicated with a triangle. A hypothetical unfolded protein is indicated by a wavy bar at the bottom of the cycle. Mutations are implied by the white squares.

Fig. 2.

Thermodynamic cycle for the mutation of Cys94. The upper arrow corresponds to the free energy of mutation in the dimer, the lower arrow in the unfolded state. Grey triangles represent WT Cys94, white squares the mutants.

Considering that the Gibbs free energy is a state function [27] the value around the cycle is equal to zero. This allows us to write:

| (1) |

where ΔΔGmut(D) represents the relative free energy difference of mutation of one aminoacid into another, which can be computed as the difference of the mutation free energy in the dimer, ΔGmutf(D) and in the unfolded state ΔGmutu. The same quantity can be written as ΔΔGfold(D), which is the relative free energy of folding and is the difference of the folding free energy of the wildtype, ΔGfoldWT(D), and of the mutant, ΔGfoldmut(D). The addition (D) explicitly refers to the dimeric state. Current computational resources do not allow us to simulate the full process of protein folding and unfolding to determine ΔΔGfold(D) directly. However, we are able to estimate this value from free energy perturbation in a folded and unfolded state [28,29]. Selection of the right representation of the unfolded state is crucial for free energy calculations [30]. We have decided to use a tripeptide with its central residue being mutated and two neighbouring residues resembling the ones in protein context, as was previously shown to agree well with experimental results [31]. For the folded state, we simulated both the monomer and the dimer to obtain a better understanding of the impact of dimerization on the stability of the protein.

2. Methods

2.1. Experimental

2.1.1. Cloning, expression, and purification of 14-3-3ζ variants

A codon-optimized gene for 14-3-3ζ (GenScript, Piscataway Township, NJ) was inserted into pET15b and two mutations C25A and C189A were inserted. Due to the fact that these mutations have negligible impact on the protein stability (TM is slightly increased from 59.5 °C to the 60.3 °C) and avoid the formation of any intermolecular artificial disulfide bonds, we used this construct as a 14-3-3ζ pseudo-WT. The 14-3-3ζ gene with the C25A and C189A mutations was therefore used as the “parental” construct for all other studied mutations, which were introduced by using the QuikChange Lightning Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA). The DNA sequence for all constructs was confirmed by sequencing (Macrogene, Seoul, Rep. of Korea). All 14-3-3ζ variants were expressed and purified by procedure described in Hritz et al. [23]. Final purity of the prepared protein variants was verified by MALDI-TOF-MS spectroscopy.

2.1.2. Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC)

Melting temperatures (TM) were obtained from DSC measurements carried out at a VP-DSC instrument (MicroCal Inc., Northampton, MA) at a heating scan rate of 1 °C per minute from 25 to 80 °C. Samples of 14-3-3ζ C94 mutants were prepared at 1 mg/ml concentration and dialyzed against a degassed 20 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 6.0). DSC data were analyzed using the Microcal Origin 7.0 software (MicroCal Inc., Northampton, MA).

2.1.3. Native polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (Native-PAGE)

10 μl of 2 μM protein sample were mixed with 10 μl of 2 × loading buffer containing 2% glycerol, 2% Bromophenol Blue, and 160 mM TRIS-HCl (pH = 6.8). Samples were then loaded into a freshly prepared 12.5% native minigel. Electrophoresis was conducted for approximately 200 min using constant voltage (95 V) in a native electrophoretic buffer (2.5 mM TRIS-HCl, 19.2 mM Glycine, pH 8.3). The apparatus was cooled down on ice during whole procedure in order to prevent the thermal denaturation of the studied proteins. Finally, the gel was stained by Coomassie Brilliant Blue R-250 (AppliChem, Darmstadt, Germany).

2.2. MD simulations

As starting configuration for molecular dynamics simulations we used an apo 14-3-3ζ crystal structure (PDB ID:1A4O [8]) at a 2.8 Å resolution. Missing loops and residues were remodelled from a holo crystal structure (PDB ID:4HKC [32]). C-terminal residues 229–245 were removed from the structure to avoid interactions of the highly flexible and unstructured C-terminus with the rest of the protein. In preliminary simulations, a high strain in the backbone of Arg18 was observed, leading to failures of the SHAKE algorithm to constrain bond lengths. It appeared that the ϕ and ψ angles of Glu17 were at the very bottom of the left-handed helical configuration in the Ramachandran plot (ϕ = 73°, ψ = −16°), leading to strain in the loop. By turning ψ of A16 and ϕ of E17 by approximately 180°, the strain was released and no further SHAKE failures were observed. All arginines, lysines and cysteines were protonated, while aspartates and glutamates were deprotonated. His164 was protonated on Nε, which was based on better hydrogen bonding possibilities in its surrounding. All MD simulations were carried out using the GROMOS11 software simulation package [33], employing the 54a8 forcefield [34]. Proteins were energy-minimized in vacuum using the steepest-descent algorithm and subsequently solvated in a rectangular, periodic and pre-equilibrated box of single point charge (SPC) water [35]. Minimum solute to box-wall distances were set to 2, 2, and 2.5 nm for dimer and 1, 1 and 2.5 nm for monomer in the x,y and z-dimensions, respectively, after alignment of the largest intramolecular distance with the z-axis. This led to systems containing about 50 to 60 thousand atoms for the monomer and 110 to 117 thousand atoms for the dimer. Another minimization in water was performed using the steepest descent algorithm. To achieve electroneutrality of the system with monomer and dimer 8 and 16 sodium ions were added to the system, respectively. Because previous simulations on very similar systems were shown to have increased structural stability at higher salt concentrations [20], simulations were additionally performed at a concentration of 300 mM NaCl. To achieve this, additional 94–127 sodium and chloride ions were added to the box of monomer and 209–219 sodium and chloride ions were added to the box of dimer. For the equilibration, the following protocol was used: initial velocities were randomly assigned according to a Maxwell–Boltzmann distribution at 60 K. All solute atoms were positionally restrained with a harmonic potential using a force constant of 2.5 × 104 kJ/mol nm−2. In each of the four subsequent 20 ps MD simulations, the force constant of the positional restraints was reduced by one order of magnitude and the temperature was increased by 60 K. Subsequently, the positional restraints were removed and rototranslational constraints were introduced on all solute atoms [36]. The last step of equilibration was performed at a constant pressure of 1 atm for 300 ps. After equilibration production runs of 60 ns were performed with constant number of particles, constant temperature (300 K) and constant pressure (1 atm). To sustain a constant temperature, we used the weak-coupling thermostat [37] with a coupling time of 0.1 ps. The pressure was maintained using a weak coupling barostat with a coupling time of 0.5 ps and an isothermal compressibility of 4.575 × 10−4 kJ−1 mol nm−3. Solute and solvent were coupled to separate temperature baths. Implementation of the SHAKE algorithm [38] to constrain bond lengths of solute and solvent to their optimal values allowed for a 2-fs time-step. Nonbonded interactions were calculated using a triple range scheme. Interactions within a short-range cutoff of 0.8 nm were calculated at every time step from a pair list that was updated every fifth step. At these points, interactions between 0.8 and 1.4 nm were also calculated explicitly and kept constant between updates. A reaction field [39] contribution was added to the electrostatic interactions and forces to account for a homogenous medium outside the long-range cutoff using a relative dielectric constant of 61 as appropriate for the SPC water model [40]. Coordinate and energy trajectories were stored every 0.5 ps for subsequent analysis. To study the overall stability of the WT protein, a total of eight independent simulations were performed: Two independent simulations of both monomer and dimer in both 0 and 300 mM NaCl, further noted as MD1 and MD2.

2.3. Thermodynamic integration (TI)

Using thermodynamic integration, the free energy difference between two states A and B can be computed via multiple discrete intermediate steps using a coupling parameter λ. If λ is equal to 0, the system is in state A and, on the other hand the system is in state B when λ is equal to 0. At each intermediate step the average of the derivative of the Hamiltionian with respect to λ is calculated. By integrating over the derivatives along the path we obtain the total free energy difference (ΔGBA).

| (2) |

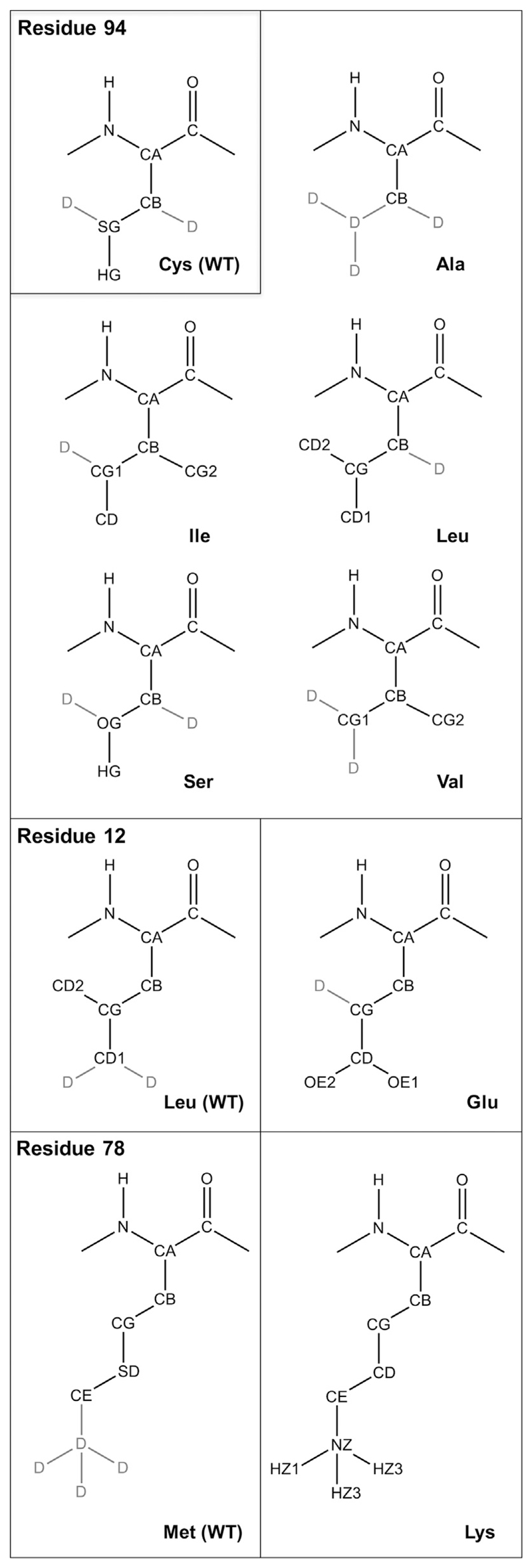

TI calculations for perturbations of selected amino acid were initially performed at 11 evenly spaced λ steps. Starting from initial structures taken after above mentioned equilibration with low salt content, 20 ps of equilibration at each λ value were followed by 1 ns of production run. If necessary, the simulations were prolonged to maximally 5 ns per λ point or additional λ points were added to decrease the overall error estimate below 3 kJ/mol. For perturbed atoms we used soft-core parameters of 0.5 for the van der Waals and 0.5 nm2 for electrostatic interactions [41]. A single topology approach was used, by introducing dummy atoms where necessary. Dummy atoms have all nonbonded interactions set to zero while the bonded interactions and the masses of individual atoms remain the same as for real atoms. This way we can selectively convert real atoms into dummy atoms and vice versa to switch between particular residues. Fig. 3 shows the complete list of structural formulas of perturbed residues, including the dummy atoms, for both sets of mutations.

Fig. 3.

Structural formulas of perturbed residues. D stands for dummy atoms.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Overall protein stability

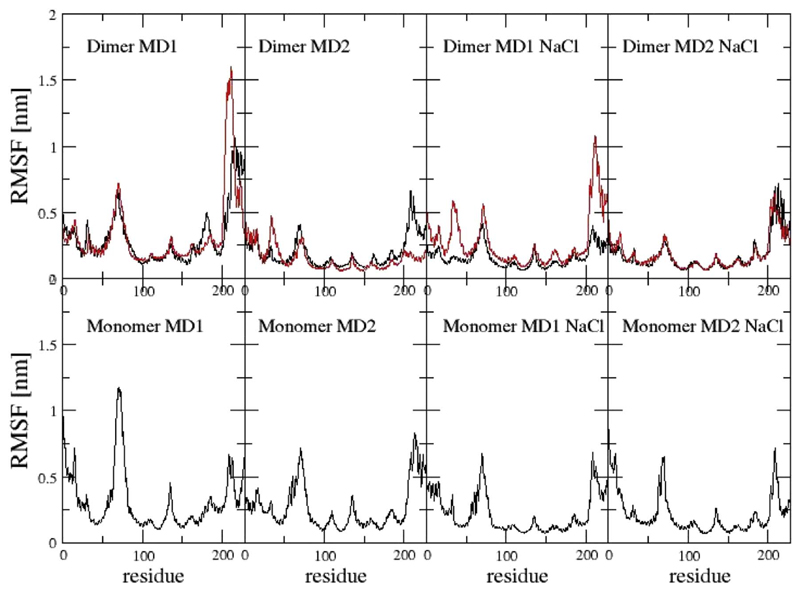

First, we investigated the overall stability of 14-3-3ζ as WT protein. We performed plain MD simulations of monomers and dimers in 0 and 300 mM NaCl for 60 ns. For each of the simulation two independent simulations were performed, noted as MD1 and MD2. The atom-positional root-mean-square deviation of Cα atoms per monomer increased up to a maximum of 1 nm after 30 ns of the dimer simulation MD1. Time series of the root-mean-square deviations of all simulations can be found in the Supplementary Material (Fig. S1). The root-mean-square fluctuations of Cα atoms (Fig. 4) as well as the secondary structure analysis (Fig. 5) shows, that the monomer simulations are characterized by a lower stability, especially in the first three helices H1 to H3 (residues 1–70), than the dimer simulations. In contrast, the last three helices (residues 162–228) seem to be less stable in simulation of dimers, which is in agreement with previous studies [20].

Fig. 4.

RMSF of Cα atoms of dimers and monomers. First monomer of the dimer in red, second in black. NaCl indicates the simulations that were performed at 300 mM NaCl concentration.

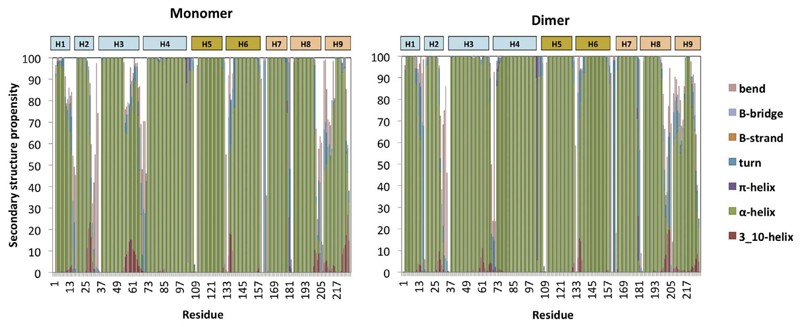

Fig. 5.

Secondary structure propensities as calculated by the DSSP program [42] for 14-3-3ζ monomer and dimer simulations, averaged over all plain WT simulations.

For the secondary structure analysis we used the DSSP algorithm (Define Secondary Structure of Proteins) [42]. Fig. 5 shows the average secondary structure propensity per residue for all simulations, i.e. MD1 and MD2 in 0 and 300 mM NaCl for the monomer simulations and averaged over both monomers for the dimer simulations. In the dimer simulation, these helices keep their α-helical secondary structure for almost the entire simulation, whereas in the monomer simulation we observe unfolding of the first three helices. Exactly these three helices are necessary for maintaining the dimer interface. After monomer separation, the interface residues become unstable which, after some time, results in a disruption of the secondary structure.

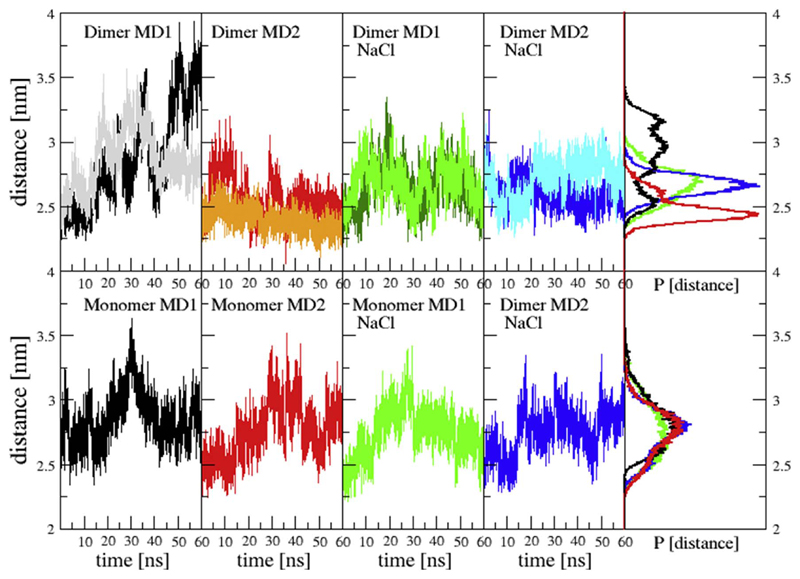

Apart from the changes in the local secondary structure of the protein a global opening and closing of the binding channel occurs. As previously described [20,43], the distance between the third and eighth helix fluctuates significantly. Fig. 6 shows the distance between Cα carbons of Gly53 and Leu191. This distance was previously suggested to describe the openness of 14-3-3ζ. While the opening distance of monomers in the dimer simulations seems to yield different distributions for every simulation, all four monomer simulations consistently show the maximum in the distance distribution at 2.8 nm. In particular the simulations of dimers at a low salt concentration seem to be more diverse in the openness of the binding channel.

Fig. 6.

Monomer opening: Distances between Cα carbons of Glu53 and Leu191. Different colours in dimer graphs correspond to monomer 1 and monomer 2. NaCl indicates the simulations that were performed at 300 mM NaCl concentration.

Furthermore, similarly to the previous work of Nagy et al. [20], an inter-monomer twist of 14-3-3ζ was observed. It means that one of the monomers is rotating with respect to the other by up to 80°. The time series of a dihedral angle showing this twist, represented by the dihedral angle Leu43(M1)-Ala54(M1)-Ala54(M2)-Leu43(M2), where M1 and M2 represents monomer 1 and 2 respectively, can be found in the Supplementary material (Fig. S2). Our analysis shows, that a large variability is observed in simulations with salt concentration of 0 and 300 mM NaCl, with intermonomer twists ranging between 15 and 80°.

3.2. Mutation of Cys94

Cysteine 94 is located in a hydrophobic environment in the middle of helix 3. We have perturbed this residue into 5 different amino acids: Alanine, Isoleucine, Leucine, Valine and Serine. The structural formulas and details of these mutations are shown in Fig. 3. The free energy differences for TI perturbations in Ile-Cys-Asn tripeptide as well as in protein were evaluated based of the thermodynamic cycle, shown in Fig. 2. Perturbation in the protein was carried out in both, monomer and dimer. Fig. S3 shows the TI curves of the perturbations in tripeptide, monomer and dimer for all five mutations. Perturbation free energies for tripeptide (ΔGmutu) as well as monomer (ΔGmutf(M)) were multiplied by two, to be comparable with the double perturbation in dimer (ΔGmutf(D)). Table 1 summarizes the free energies obtained from the simulations. The free energies as obtained for the monomers agree very well with the stability predicted for the dimers. Both sets of simulations suggest that the Ala and Ser mutations lead to a loss of stability (ΔΔGmutf > 0) while the Val mutant shows comparable stability as the wildtype and Leu and Ile increase the stability at the simulated temperature. For comparison, the experimental melting temperatures as determined by DSC (experimental details described in the Methods) are also included in Table 1.

Table 1.

Predicted free-energy differences, ΔG, for monomer, dimer and tripeptide simulation and their differences ΔΔG in kJ/mol. TM corresponds to the experimentally determined melting temperatures in °C.

| 2ΔGmutf(M) | ΔGmutf(D) | 2ΔGmutu | 2ΔΔGmutf(M) | ΔΔGmutf(D) | TM | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [kJ/mol] | [°C] | |||||

| Ala | 55 ± 1 | 59 ± 1 | 41 ± 2 | 14 ± 2.0 | 18 ± 2 | 54.0 |

| Ile | 24 ± 3 | 29 ± 4 | 51 ± 3 | −26 ± 4 | −22 ± 5 | 55.6 |

| Leu | 21 ± 2 | 23 ± 2 | 34 ± 2 | −13 ± 3 | −11 ± 2 | 57.0 |

| Ser | 2 ± 1 | 9 ± 1 | −46 ± 1 | 47 ± 1 | 55 ± 1 | 52.5 |

| Val | 56 ± 1 | 61 ± 2 | 60 ± 1 | −4 ± 2 | 1 ± 2 | 55.0 |

| Cys (WT) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 60.3 |

While ΔΔGmutf is a measure of stability at a given thermodynamic state (here at a temperature of 300 K), the melting temperature depends on the behavior of the protein at a range of different temperatures. Therefore, and because the thermal unfolding of the 14-3-3 constructs was observed to be fully irreversible, ΔΔGmutf and TM cannot be expected to correlate exactly. Still, both quantities are indicative of protein stability. In fact, a common strategy by which thermophilic proteins increase the melting temperature is to decrease the free energy of folding over the entire temperature range [26]. Arguably, a single point mutation is more likely to crease the folding free energy at the entire temperature range, than to have a significant effect on the protein heat capacity, leading to alternative temperature dependencies.

Our simulation data agrees with the experimental stability estimates by identifying Ser and Ala as the two least stable mutants, with ΔΔGmut(D) of 54 kJ/mol and 18 kJ/mol, respectively. However, the simulations predict Ile and Leu to be more stable than the WT, while the experimentally determined TM is slightly lower than for the wildtype. The large instability of Ala and Ser is striking, as these are typically the first mutations suggested to replace Cys in experiments. Both simulations and the experimentally determined melting temperatures show that these particular mutations are rather unfortunate choices to replace Cys94 in 14-3-3ζ.

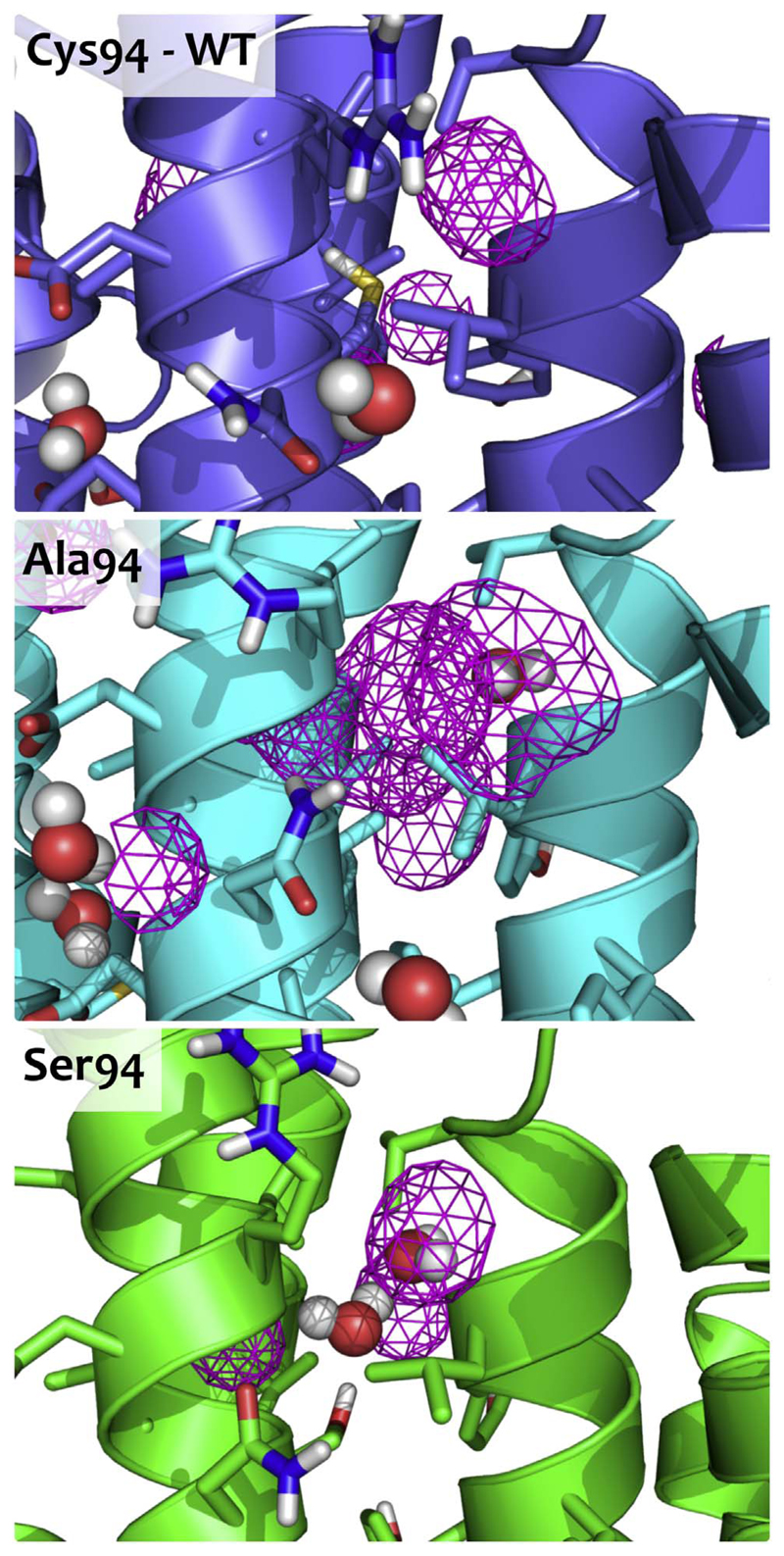

Our rationalization of the destabilizing effect of the C94A and C94S mutants is that these mutations disrupt the hydrophobic core in that region [44]. Considering that position 94 is located in a very hydrophobic region among three helices, any disturbance of this hydrophobicity might lead to a decrease of protein stability. Detailed snapshots from the last step of simulations are shown in Fig. 7. When a hydrophobic cysteine residue [45] is replaced by a hydrophilic serine, there are only a few possibilities for serine to create hydrogen bonds within its surrounding. Hydrogen bonding between the sidechain oxygen of Ser94 and the backbone oxygen of Leu90 was observed in 45% of simulation time in the last simulation of the TI simulations (λ = 1.00). Interestingly, in one monomer we could see a hydrogen bond between a water molecule and Ser94. While hydrogen bonding is energetically favourable, introducing water molecules into a hydrophobic core might lead to structural reorganization and destabilization. On the other hand, after insertion of alanine into a densely packed core, a voluminous hydrophobic cavity is created. It has been previously shown, that substitution of bulky hydrophobic amino acids by smaller, cavity-creating ones is unfavourable and leads to a loss of stability [46]. The other branched hydrophobic aminoacids, on the contrary, fill the cavity and contribute favourably to the hydrophobic interactions in the core and, thus, stabilise the protein.

Fig. 7.

Snapshots of the most the WT and the two most destabilizing mutants of Cys94. The cavities inside of the protein as computed by Pymol [47] are shown in pink.

3.3. Mutation of Leu12 and Met78

3.3.1. Experimental

Under normal circumstances, without any posttranslational modifications the monomer/dimer equilibrium of the 14-3-3ζ isoform is strongly shifted towards the dimer [48]. A variety of 14-3-3 dimer-in-capable forms were reported over last two decades and they are nicely summarized in Table 1 of the review of Sluchanko et al. [48] The listed mutations shifting this equilibrium towards monomer change the overall charge of 14-3-3 monomer with respect to the WT. Here, we designed a double mutation Leu12Glu and Met78Lys which does not change the overall charge of the 14-3-3ζ monomer and at the same time is almost exclusively in monomeric state at a μM concentration range. Fig. 8B shows a native PAGE gel of WT and the double mutant at 1 μM concentration. The L12E/M78K double mutant is propagating faster through the PAGE than WT. Considering that both of these proteins have the same overall charge per monomer our interpretation is that the L12E/M78K double mutant is in the monomeric form in contrast to the dimeric form of the 14-3-3ζ WT at the given conditions.

Fig. 8.

A) Thermodynamic cycle of mutations at the 14-3-3ζ dimeric interface. WT Leu12 and Met78 are in grey cylinder and circle and Glu12 and Lys78 in white pentagon and parallelogram. B) Native PAGE of 14-3-3ζ (pseudo) WT and the L12E/M78K double mutant at 1 μM concentration showing the higher oligomeric state of WT.

3.3.2. Simulation

To rationalize the experimental results computationally, we have performed in silico mutations L12E and M78K in three different systems. One of them was, again, a tripeptide representing the unfolded state within a protein context, Lys11-Leu12-Ala13 and Gln77-Met78-Ala79. The other two were in dimer and monomer simulations. In contrast to the mutations applied to Cys94, the individual mutations involve full charge changes. The L12E mutation leads to negative charges, while the M78K mutations leads to a positive charge (see Fig. 3). Thus, the overall charge of the system stays neutral and there is no need for additional corrections [49]. The total scheme of the resulting thermodynamic cycles can be seen in Fig. 8A. Here, we compute the relative dimerization free energies, ΔΔGdim as the difference between the dimerization free energies of the mutant and the wildtype, which is the same as the difference in the mutation free energy in the mutant and in the monomers,

| (3) |

Similarly to the Cys94 mutations, we can also define the relative folding free energy of the monomers as

| (4) |

where in this case the mutational free energy of the unfolded state is the sum of two independent simulations of the tripeptides

| (5) |

The folding free energy of the complete dimers is subsequently related to the previous properties as

| (6) |

Table 2 shows the resulting free energy differences and TI curves for the mutations in all three systems can be found in Fig. S4. The free-energy calculations show that the difference of free energy between the mutant and the WT is 90 kJ/mol for dimer, i.e. 45 kJ/mol per monomer in dimer. Despite the fact, that these values are unusually high, they show that the 14-3-3ζ WT is much more stable in its dimeric form than the L12E-M78K double mutant. Our predictions agree with the experimental assay, where at 1 μM concentration no trace of a monomeric state was found for the WT, while the monomeric state was dominant for the L12K/M78E mutant (Fig. 8B).

Table 2.

Free energy of mutation in different systems, and their differences, ΔΔG, in kJ/mol.

| ΔG | [kJ/mol] |

|---|---|

| ΔGmutf(D) | −1169 ± 9 |

| 2ΔGmutf(M) | −1259 ± 11 |

| 2ΔGmutu | −1296 ± 8 |

| 2ΔΔGfold(M) | 37 ± 14 |

| 2ΔΔGdim | 90 ± 14 |

| 2ΔΔGfold(D) | 127 ± 12 |

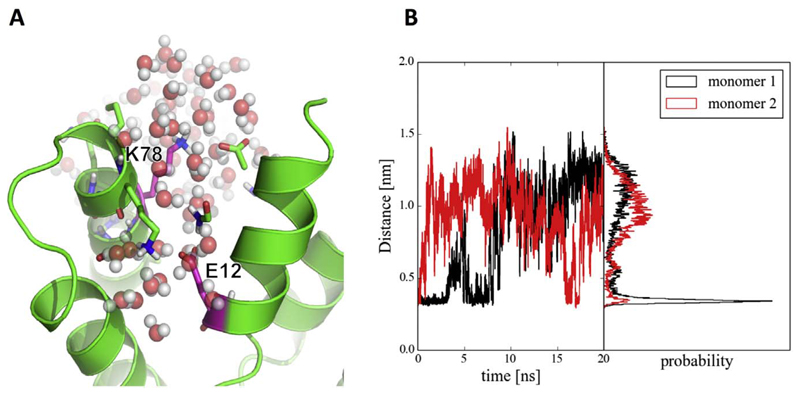

The exact role of salt bridges in stabilising of protein complexes has been a source of dispute for a long time [50]. The driving forces for salt bridge formation are primarily energetically favourable Coulombic charge-charge interactions between two ionized amino acids. In order to build a stable salt bridge, however, two additional factors play a key role: the orientation of interacting sidechains and the local context [51]. The sidechain orientation is crucial for keeping charged moieties in close vicinity, which is necessary for electrostatic interactions. This might, however, lead to an unfavourable loss in entropy. If the local context is rich in other possible interaction partners, the probability of salt bridge formation might be decreased as well. Therefore, due to the immobilization and desolvation of the interacting residues, creating a salt bridge in solvent may be unfavourable. The time series of the distance between Leu12 and Met78 throughout the TI simulation resembles this case (Fig. S5). In the beginning of the simulation, the residue distance varies between 0.2 and 1.0 nm. In this phase, these neutral residues interact via hydrophobic interactions. After introducing small charges to the perturbing residues, the residues start to create a stable salt bridge with a length of about 0.3 nm. In the last perturbation step, nevertheless, the distance increases again. This may be ascribed to the high charge of both residues and preferential interaction of Lys78 with solvent. A snapshot of the final state can be seen in Fig. 9A. The simulation of the double mutant L12E, M78K was prolonged up to 20 ns. In monomer 1, the salt bridge was formed for the first 3 ns, then lost for a host time and reformed for another 4 ns, before it was lost completely. In monomer 2, the salt bridge was immediately lost, only to be formed transiently again after 15 ns (Fig. 9B). This indicates that, while the salt bridge could be formed theoretically, the residues prefer to interact favourably with the solvent.

Fig. 9.

A) A snapshot from the simulation at the last perturbation step (λ = 1.00), corresponding to the double mutant, K78 is solvated. B) Distance between NZ in K78 and CD in Glu12 from prolonged simulations at λ = 1.00.

4. Conclusion

Two types of mutation of the human regulatory protein 14-3-3ζ were studied by free energy calculations and experimental stability measurements. Both computational and experimental approaches agreed that the common Ala and Ser replacements of Cys94 leads to considerable protein destabilization. The folding free energies were significantly reduced, as was confirmed by a lower melting temperature. These findings could be rationalized at a molecular level by the hydrophobic nature of the particular position and the formation of small cavities upon mutation to Ala.

Similarly, free energy calculations on a double mutant (L12K/M78E) that was found to show a significantly reduced tendency to dimerize were performed and found to be in agreement with the experimental findings. The putative salt bridge that was introduced in the double mutant was only observed for a limited amount of time, while the ionic species of the sidechains, in particular Lys78, are more favourably solvated individually in the individual monomers.

Overall, our work nicely demonstrates the strength of molecular simulations and free energy calculations as a complementary tool to experimental observation. The simulations offer explanations at a molecular level that are not easily accessible experimentally. This type of computational tools can be also used for the more efficient rational design of mutations having desired physico-chemical properties.

Supplementary Material

The Transparency document associated with this article can be found, in online version.

Acknowledgments

Financial support of the Austrian Science Fund (grant numbers W1224 and I 1999-N28) is gratefully acknowledged. J.H., Z.T. and V.W. acknowledge the financial support of the Czech Science Foundation (GF15-34684L). CIISB research infrastructure project LM2015043, funded by Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports of the Czech Republic (MEYS CR), is gratefully acknowledged for partial financial support of the measurements at the Proteomics and Biomolecular Interactions Core Facilities, CEITEC – Masaryk University.

References

- [1].Aitken A, Collinge DB, van Heusden BPH, Isobe T, Roseboom PH, Rosenfeld G, Soll J. 14-3-3 proteins: a highly conserved, widespread family of eukaryotic proteins. Trends Biochem Sci. 17:498–501. doi: 10.1016/0968-0004(92)90339-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Wang W, Shakes DC. Molecular evolution of the 14-3-3 protein family. J Mol Evol. 1996;43:384–398. doi: 10.1007/BF02339012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Rosenquist M, Sehnke P, Ferl RJ, Sommarin M, Larsson C. Evolution of the 14-3-3 protein family: does the large number of isoforms in multicellular organisms reflect functional specificity? J Mol Evol. 2000;51:446–458. doi: 10.1007/s002390010107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Aitken A. 14-3-3 proteins: a historic overview. Semin Cancer Biol. 2006;16:162–172. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2006.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Jones DH, Ley S, Aitken A. Isoforms of 14-3-3 protein can form homo- and heterodimers in vivo and in vitro: implications for function as adapter proteins. FEBS Lett. 1995;368:55–58. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(95)00598-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Messaritou G, Grammenoudi S, Skoulakis EMC. Dimerization is essential for 14-3-3 zeta stability and function in vivo. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:1692–1700. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.045989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Yang XW, Lee WH, Sobott F, Papagrigoriou E, Robinson CV, Grossmann JG, Sundstrom M, et al. Structural basis for protein-protein interactions in the 14-3-3 protein family. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:17237–17242. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605779103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Liu D, Bienkowska J, Petosa C, Collier RJ, Fu H, Liddington R. Crystal structure of the zeta isoform of the 14-3-3 protein. Nature. 1995;376:191–194. doi: 10.1038/376191a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Gardino AK, Smerdon SJ, Yaffe MB. Structural determinants of 14-3-3 binding specificities and regulation of subcellular localization of 14-3-3-ligand complexes: a comparison of the X-ray crystal structures of all human 14-3-3 isoforms. Semin Cancer Biol. 2006;16:173–182. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2006.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Burbelo PD, Hall A. 14-3-3 proteins. Hot numbers in signal transduction. Curr Biol. 1995;5:95–96. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(95)00022-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Rubio MP, Geraghty KM, Wong BHC, Wood NT, Campbell DG, Morrice N, Mackintosh C. 14-3-3-affinity purification of over 200 human phosphoproteins reveals new links to regulation of cellular metabolism, proliferation and trafficking. Biochem J. 2004;379:395–408. doi: 10.1042/BJ20031797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Johnson LN, Barford D. The effects of phosphorylation on the structure and function of proteins. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct. 1993;22:199–232. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bb.22.060193.001215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Hubbard MJ, Cohen P. On target with a new mechanism for the regulation of protein phosphorylation. Trends Biochem Sci. 1993;18:172–177. doi: 10.1016/0968-0004(93)90109-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Pawson T, Scott JD. Signaling through scaffold, anchoring, and adaptor proteins. Science. 1997;278:2075–2080. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5346.2075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Pawson T, Raina M, Nash P. Interaction domains: from simple binding events to complex cellular behavior. FEBS Lett. 2002;513:2–10. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(01)03292-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Mackintosh C. Dynamic interactions between 14-3-3 proteins and phosphoproteins regulate diverse cellular processes. Biochem J. 2004;381:329–342. doi: 10.1042/BJ20031332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Nagata K, Puls A, Futter C, Aspenstrom P, Schaefer E, Nakata T, Hirokawa N, et al. The MAP kinase kinase kinase MLK2 co-localizes with activated JNK along microtubules and associates with kinesin superfamily motor KIF3. EMBO J. 1998;17:149–158. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.1.149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Tzivion G, Shen YH, Zhu J. 14-3-3 proteins; bringing new definitions to scaffolding. Oncogene. 2001;20:6331–6338. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Yaffe MB, Rittinger K, Volinia S, Caron PR, Aitken A, Leffers H, Gamblin SJ, et al. The structural basis for 14-3-3:phosphopeptide binding specificity. Cell. 1997;91:961–971. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80487-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Nagy G, Oostenbrink C, Hritz J. Exploring the binding pathways of the 14-3-3zeta protein: structural and free-energy profiles revealed by Hamiltonian replica exchange molecular dynamics with distancefield distance restraints. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0180633. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0180633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Yaffe MB. How do 14-3-3 proteins work?— gatekeeper phosphorylation and the molecular anvil hypothesis. FEBS Lett. 2002;513:53–57. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(01)03288-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Johnson C, Crowther S, Stafford MJ, Campbell DG, Toth R, MacKintosh C. Bioinformatic and experimental survey of 14-3-3-binding sites. Biochem J. 2010;427:69–78. doi: 10.1042/BJ20091834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Hritz J, Byeon IjL, Krzysiak T, Martinez A, Sklenar V, Gronenborn AM. Dissection of binding between a phosphorylated tyrosine hydroxylase peptide and 14-3-3ζ: a complex story elucidated by NMR. Biophys J. 2014:2185–2194. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2014.08.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Rees DC, Robertson AD. Some thermodynamic implications for the thermostability of proteins. Protein Sci. 2001;10:1187–1194. doi: 10.1110/ps.180101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Becktel WJ, Schellman JA. Protein stability curves. Biopolymers. 1987;26:1859–1877. doi: 10.1002/bip.360261104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Razvi A, Scholtz JM. Lessons in stability from thermophilic proteins. Protein Soc. 2006;15:1569–1578. doi: 10.1110/ps.062130306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Cohen R, Tom, Frey JG, Holström B, IUPAC . Quantities, Units and Symbols in Physical Chemistry. 2nd ed. Blackwell Scientific Publications; Oxford: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- [28].Shi YY, Mark AE, Wang CX, Huang F, Berendsen HJ, van Gunsteren WF. Can the stability of protein mutants be predicted by free energy calculations? Protein Eng. 1993;6:289–295. doi: 10.1093/protein/6.3.289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Christ CD, Mark AE, van Gunsteren WF. Feature article basic ingredients of free energy calculations: a review. J Comput Chem. 2010;31:1569–1582. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Sugita Y, Kitao A. Dependence of protein stability on the structure of the denatured state: free energy calculations of I56V mutation in human lysozyme. Biophys J. 1998;75:2178–2187. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(98)77661-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Eichenberger AP, van Gunsteren WF, Riniker S, von Ziegler L, Hansen N. The key to predicting the stability of protein mutants lies in an accurate description and proper configurational sampling of the folded and denatured states. Biochim Biophys Acta Gen Subj. 2015;1850:983–995. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2014.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Bonet R, Vakonakis I, Campbell ID. Characterization of 14-3-3-zeta interactions with integrin tails. J Mol Biol. 2013;425:3060–3072. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2013.05.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Schmid N, Christ CD, Christen M, Eichenberger AP, van Gunsteren WF. Architecture, implementation and parallelisation of the GROMOS software for biomolecular simulation. Comput Phys Commun. 2012;183:890–903. [Google Scholar]

- [34].Reif MM, Winger M, Oostenbrink C. Testing of the GROMOS force-field parameter set 54A8: structural properties of electrolyte solutions, lipid bilayers, and proteins. J Chem Theory Comput. 2013;9:1247–1264. doi: 10.1021/ct300874c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Berendsen HJC, Postma JPM, van Gunsteren WF, Hermans J. Interaction models for water in relation to protein hydration. In: Pullman B, editor. Intermolecular Forces: Proceedings of the Fourteenth Jerusalem Symposium on Quantum Chemistry and Biochemistry Held in Jerusalem, Israel, April 13–16, 1981; Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands; 1981. pp. 331–342. [Google Scholar]

- [36].Amadei A, Chillemi G, Ceruso MA, Grottesi A, Di Nola A. Molecular dynamics simulations with constrained roto-translational motions: theoretical basis and statistical mechanical consistency. J Chem Phys. 2000;112:9–23. [Google Scholar]

- [37].Berendsen HJC, Postma JPM, Vangunsteren WF, Dinola A, Haak JR. Molecular dynamics with coupling to an external bath. J Chem Phys. 1984;81:3684–3690. [Google Scholar]

- [38].Ryckaert JP, Ciccotti G, Berendsen HJC. Numerical integration of cartesian equations of motion of a system with constraints - molecular dynamics of N-alkanes. J Comput Phys. 1977;23:327–341. [Google Scholar]

- [39].Tironi IG, Sperb R, Smith PE, van Gunsteren WF. A generalized reaction field method for molecular dynamics simulations. J Chem Phys. 1995;102:5451–5459. [Google Scholar]

- [40].Heinz TN, van Gunsteren WF, Hünenberger PH. Comparison of four methods to compute the dielectric permittivity of liquids from molecular dynamics simulations. J Chem Phys. 2001;115:1125–1136. [Google Scholar]

- [41].Beutler TC, Mark AE, van Schaik RC, Gerber PR, van Gunsteren WF. Avoiding singularities and numerical instabilities in free energy calculations based on molecular simulations. Chem Phys Lett. 1994;222:529–539. [Google Scholar]

- [42].Kabsch W, Sander C. Dictionary of protein secondary structure: pattern recognition of hydrogen-bonded and geometrical features. Biopolymers. 1983;22:2577–2637. doi: 10.1002/bip.360221211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Hu G, Li H, Liu JY, Wang J. Insight into conformational change for 14-3-3sigma protein by molecular dynamics simulation. Int J Mol Sci. 2014;15:2794–2810. doi: 10.3390/ijms15022794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Dill KA. Dominant forces in protein folding. Biochemistry. 1990;29:7133–7155. doi: 10.1021/bi00483a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Nagano N, Ota M, Nishikawa K. Strong hydrophobic nature of cysteine residues in proteins. FEBS Lett. 1999;458:69–71. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(99)01122-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Eriksson AE, Baase WA, Zhang XJ, Heinz DW, Blaber M, Baldwin EP, Matthews BW. Response of a protein structure to cavity-creating mutations and its relation to the hydrophobic effect. Science. 1992;255:178–183. doi: 10.1126/science.1553543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Schrödinger L. The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System. Version~1. 8 ed. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- [48].Sluchanko NN, Gusev NB. Oligomeric structure of 14-3-3 protein: what do we know about monomers? FEBS Lett. 2012;586:4249–4256. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2012.10.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Reif MM, Oostenbrink C. Net charge changes in the calculation of relative ligandbinding free energies via classical atomistic molecular dynamics simulation. J Comput Chem. 2014;35:227–243. doi: 10.1002/jcc.23490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Strop P, Mayo SL. Contribution of surface salt bridges to protein stability. Biochemistry. 2000;39:1251–1255. doi: 10.1021/bi992257j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Makhatadze GI, Loladze VV, Ermolenko DN, Chen X, Thomas ST. Contribution of surface salt bridges to protein stability: guidelines for protein engineering. J Mol Biol. 2003;327:1135–1148. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(03)00233-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.