Introduction

A great deal of research has demonstrated that young women who become pregnant as teens or in their early twenties, particularly those who are unmarried, are disadvantaged relative to their peers. However, less research has examined their partners and the quality of their intimate relationships in the months before their pregnancies. In this Article, we use newly available data on a random sample of 880 young women, ages eighteen and nineteen, from a county in Michigan, who completed weekly five minute surveys for up to two-and-a-half years. Using this longitudinal, population-representative data, we compare the intimate relationships of women who got pregnant during the study to women who did not get pregnant.

Further, because the dataset includes a complete record of all relationships during the study period, we also compare the partners and relationships that produced pregnancies to young pregnant women’s other partners and relationships that did not produce pregnancies. We find that the fathers of the pregnancies are older and less educated than non-pregnant women’s partners, and the intimate relationships are serious, unstable, and conflictual. It is the oldest and least educated partners who father their pregnancies, but young pregnant women’s non-pregnancy relationships are not much different from their peers’ relationships that do not lead to pregnancy. In addition, comparing intimate relationship characteristics during the period before the pregnancy to characteristics after the pregnancy demonstrates that the relationships deteriorate after the pregnancy, breaking up or becoming less serious and also becoming more violent.

Nonmarital childbearing has increased dramatically, from less than 5% of births in 1940 to approximately 40% in 2013.1 Young unmarried women who get pregnant are disadvantaged:2 unmarried mothers and fathers are more likely to be in their teens, to have multi-partner fertility, to be poor, to suffer from depression, to have difficulties with substance abuse, and to have spent time in jail. Unmarried parents are also much more likely to be poor and to rely on public assistance programs than married parents.3

The Fragile Families & Child Well-Being (FFCWB)4 study has revolutionized our understanding of these families. Because couples were interviewed at the time their baby was delivered, FFCWB made it possible to observe the developmental trajectories of these children and of the subsequent relationship between their parents. This design allowed researchers to differentiate among relationships previously characterized as only “unmarried,” and thus to compare child development in different types of families, such as those who are not romantically involved, those who are in a serious relationship but live apart, and those who are cohabiting. Analyses of the FFCWB data show that, on average, less involvement of the father means more disadvantage for children.5

Ethnographic research has also illuminated the inner workings of these relationships. Kathryn Edin and Maria Kefalas studied 162 low-income single mothers in poor neighborhoods over several years.6 Edin and Kefalas found that the experience of becoming a mother was deeply meaningful and life-changing for the women in their study.7 But the women also described intimate partners that they did not want to marry—not because they did not want to get married, but rather because they had not yet created a situation worthy of the significance they attributed to marriage.8 Although Edin and Nelson provide a much more sympathetic picture of young, unmarried men who become fathers when they take the father’s point of view, they still describe intimate relationships that are new, tenuous, and problematic. 9

Building on this rich body of research, we contribute in two ways. Because FFCWB focuses on a sample of children whose unmarried parents were both present at the birth, we know relatively little about fathers who were not present at the birth— perhaps the most fragile families. And, because all of these studies began after the birth of the child, it is difficult to know about the intimate relationships during the time that led up to the pregnancy. Retrospective accounts of the intimate relationships that produced those pregnancies are difficult to interpret in light of the ex post facto rationalizations that are likely to occur in the face of the current situation, when the intimate relationship is likely to be over.10

Research on these questions is made possible by newly available data from the Relationship Dynamics and Social Life (RDSL) Study. The data features weekly measures of relationships for a racially and socioeconomically diverse, population-based random sample of 1,003 young women. We focus here on the 880 young women who ever reported an intimate partner during the two-and-a-half year study period. In the Study, 183 of the RDSL young women experienced 216 pregnancies with 194 distinct partners. Although RDSL interviewed only women, and thus provides information on the relationship only from their perspective, it is a complement to datasets like FFCWB because it provides information on those relationships for which it would be extremely difficult to interview the partners (e.g., casual relationships, abusive partners, etc.).

Further, the prospective design that begins before pregnancy allows us: (1) compare the intimate relationships that led to pregnancies to those that did not; (2) compare the intimate relationship that led to pregnancy to young women’s other relationships (that did not lead to pregnancy); and (3) compare intimate relationships that led to pregnancy at two points in time: before and after the pregnancy.11 Although the RDSL Study does not include data about the children born from the pregnancies, we motivate our analyses in part by focusing on the consequences of intimate relationships for children born into these relationships.

I. Partners

Research demonstrates that children in fragile families are better off with involved fathers.12 Edin and Nelson documented fathers’ strong desires to spend time with their children.13 Yet, fathers in unmarried families tend to be involved with their children in the early years, but that involvement declines over time, probably with the deterioration of the parental relationship.14

A great deal of research has documented that young unmarried fathers are less educated,15 earn less, and pay little in child support.16 Further, young unmarried couples are frequently dealing with multi-partner fertility—when one or both partners have existing children with another partner.17 There are large age gaps with these couples—young unmarried women who get pregnant tend to do so with partners who are older.18

Using the RDSL data, we compare the partners who fathered pregnancies to those who did not. Additionally, we compare the partners of young women who got pregnant—the partners who fathered their pregnancies—and their other partners during a similar time period. Thus, we ask whether the fathers of the pregnancies are more disadvantaged than these women’s other partners. Although we do not have direct measures of the characteristics of the available men in the young women’s lives, we interpret these differences as suggestive of the types of partners they can readily access.

II. Intimate Relationships

A great deal of research has focused on the intimate relationships of young, unmarried women who become pregnant.19 Research from the FFCWB demonstrates that the vast majority of these couples are in serious romantic relationships at the time of the birth and are optimistic about their future together.20 Five years later, however, few remain together.21 Focusing on the period before the pregnancy, other research concluded that, “conception usually happens so quickly that the ‘real relationship’ doesn’t begin until the fuse of impending parenthood has been lit.”22 In other words, the couples had been together for only a short time before the pregnancy, and most had not been in committed or sexually exclusive relationships. In fact, the majority of young fathers have concurrent sexual partners while in an intimate relationship with the mother,23 a major source of conflict in couples.24 Conflict is a particularly important aspect of intimate relationships that affects children.25

These relationships affect children via five crucial mechanisms: resources, mental health, relationship quality, parenting, and father involvement.26 Family structure and family instability are both important for child well-being.27 Children who grow up with two parents are better off than those in single-parent families, with cohabiting parents somewhere in-between.28 Holding family type constant, stability is better for children than instability.29 For some aspects of child well-being, stability is especially important in relation to family type.30

Building on the description of intimate relationships that lead to pregnancy in existing research—casual, conflictual relationships that get more serious at the time of conception but are stable only until the baby is born or shortly thereafter—we take a more in-depth look at the relationships leading up to pregnancy than has previously been possible. We focus on multiple aspects of seriousness, instability, and conflict in intimate relationships. We compare the relationships that led to pregnancy to the pregnant young women’s other relationships (that did not lead to pregnancy). This comparison suggests the extent to which young women who become mothers have opportunities for the types of serious, stable relationships that are best for children.

III. Hypotheses

1. Partners

-

1a

Partners who fathered a pregnancy are older, less educated, and have existing children prior to this relationship, relative to partners who did not father a pregnancy.

-

1b

Among pregnant women, the fathers of their pregnancies are older, less educated, and more likely to have existing children than their other partners who did not father their pregnancies.

2. Relationships

-

2a

Relationships that produced pregnancies are more serious, unstable, and violent than relationships that did not produce a pregnancy.

-

2b

Among pregnant women, relationships that produced pregnancies are more serious, unstable, and violent than pregnant women’s other relationships that did not produce pregnancies.

-

2c

After a pregnancy, relationships become even less serious, more unstable, and more violent than before the pregnancy.

IV. Data and Methods

a. Study Design

The Relationship Dynamics and Social Life (RDSL) Study was based on a simple random sample of the population of young women, ages eighteen to nineteen, residing in Genesee County, Michigan. The sample of 1,003 young women was drawn from driver’s license and personal ID card records. An hour-long face-to-face baseline survey interview was conducted between March 2008 and July 2009, to assess sociodemographic characteristics, attitudes, and adolescent experiences related to pregnancy. The response rate was 84% (94% of located respondents agreed to participate). At the conclusion of this baseline interview, respondents were invited to participate in a two-and-a-half year follow-up study that required completion of weekly online or telephone surveys assessing respondents’ intimate relationships, contraceptive use, pregnancy desires, and pregnancy experiences.

Respondents were mailed a $5 bill in an advance letter and were paid $30 to participate in the baseline interview. They received additional incentives to participate in the weekly surveys: $5 per interview for the first four weeks, and afterwards $1 per interview with $5 bonuses for on-time completion of five interviews in a row.

In all, of the 1,003 young women, 992 of the baseline interview respondents (99%) agreed to participate in the follow-up study, and 953 (96%) of those respondents completed at least one survey after the baseline interview; 84% remained in the study for at least 6 months; 79% continued for at least twelve months; and 75% continued for at least eighteen months. The follow-up study concluded in January 2012, and yielded 58,594 weekly interviews. The analytic sample for the statistical analyses is described in greater detail below. We focus on the 882 women who reported having a partner at any time during the study. Two pregnancies reported by two separate women could not be linked to any partner they ever reported; thus, those women are dropped from our analyses.

b. Measures

i. Pregnancy

In each weekly survey, respondents were asked, “Do you think there might be a chance that you are pregnant right now?” Respondents who answered “yes” were asked, “Has a pregnancy test indicated that you are pregnant?” Respondents who answered “yes” to the question about the pregnancy test were coded 1 for pregnant. Of the 880 women in our analyses, 183 women (21%) reported 216 pregnancies during the study period.

ii. Characteristics of the young women

We investigate differences in family background, sociodemographic characteristics, and adolescent sexual experiences among non-pregnant and pregnant young women. All of these measures refer to experiences at or before the baseline survey interview. We do not describe them in detail here, because they are described in published research elsewhere,31 and are not central to our focus in this paper. We include race, age, and religiosity of the young women in our sample, but do not consider them to be indicators of disadvantage. We similarly include race of the partner as a descriptor, but not an indicator of disadvantage. Descriptive statistics, including mean/proportion and range, are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the Young Women in RDSL

| All respondents (n=880) | Non-pregnant respondents (n=697) | Pregnant respondents (n=183) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||||

| Proportion/Mean | SD | Min | Max | Proportion/Mean | ↔ sig. diff. |

Proportion/Mean | |

|

Number of Pregnancies during the Study Period

| |||||||

| 0 | 79% | 0 | 1 | 100% | – | 0% | |

| 1 | 18% | 0 | 1 | 0% | – | 84% | |

| 2 | 3% | 0 | 1 | 0% | – | 14% | |

| 3+ | 0% | 0 | 1 | 0% | – | 2% | |

|

|

|||||||

| Total | 100% | 100% | 100% | ||||

|

Demographics | |||||||

| Age | 19.18 | .57 | 18.12 | 20.34 | 19.19 | ns | 19.17 |

| Black | .34 | 0 | 1 | .32 | † | .39 | |

|

Family Background | |||||||

| Childhood disadvantage (sum of four indicators: receipt of public assistance, single-parent household, teen mother, mother’s education ≤ high school) | 1.28 | 1.10 | 0 | 4 | 1.18 | *** | 1.66 |

| Highly religious | .58 | 0 | 1 | .57 | ns | .59 | |

|

Socioeconomic Characteristics at the Baseline Survey | |||||||

| High school GPA | 3.12 | .61 | .00 | 4.17 | 3.15 | ** | 3.00 |

| Receiving public assistance | .26 | 0 | 1 | .23 | *** | .39 | |

| Enrolled in a 2- or 4-year post-secondary program | .58 | 0 | 1 | .59 | *** | .42 | |

| Employed | .50 | 0 | 1 | .52 | * | .42 | |

|

Adolescent Experiences Related to Pregnancy | |||||||

| Age at first sex 16 years or less | .53 | 0 | 1 | .48 | *** | .72 | |

| Two or more sex partners | .61 | 0 | 1 | .57 | *** | .76 | |

| Had sex without birth control | .49 | 0 | 1 | .44 | *** | .69 | |

| Any adolescent pregnancies | .26 | 0 | 1 | .21 | *** | .44 | |

Notes:

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001;

p < .10;

two-tailed independent samples t-tests

ns not significant

– no test

iii. Partner characteristics

Respondents were asked a series of questions to ascertain whether they had a partner of any kind during the prior week. These partners ranged from a spouse, fiancé, cohabiter, or romantic partner, to someone with whom the respondent had physical and/or emotional contact (such as kissing, dating, spending time together, sex, or other activities). Respondents who had more than one partner during the prior week were asked to identify the most important or the most serious partner. Ninety percent reported at least one partner during the study period (not shown in tables). Of the 2,499 unique partners reported, 194 (8%) were the fathers of the 216 pregnancies. Whenever the women named a new partner, they were asked that partner’s age, education, fatherhood status, and race.

iv. Relationship characteristics

We define relationships in several ways in our analyses. First, we consider each of the 2,499 partnerships to be a unique relationship. That is, even if a young woman broke up with a partner, had other intimate relationships, and then got back together with a prior partner, we consider that relationship to be a single relationship with a break in the middle. However, we also consider each of the 216 pregnancies to have been produced by its own relationship. That is, even if a single partner fathered two pregnancies, we consider the relationship characteristics separately in regard to each pregnancy. So, for example, we consider the relationship characteristics separately if the first pregnancy occurred in a relationship with no prior pregnancies, and the second pregnancy occurred in a relationship with a prior pregnancy. For this reason, when we consider relationships in the context of pregnancy, there are 2,521 relationships—rather than accounting for 194 relationships, the 194 partners who fathered pregnancies account for 216 relationships.

v. Duration

Each week respondents were asked if their partner was the same as the prior week’s partner, or if not, whether they had ever mentioned the partner before. If the partner differed from the prior week, but was previously mentioned, they chose from a list of names or initials to identify partners from earlier weeks. The RDSL thus has a continuous record of the relationship with each specific partner during the study period, regardless of whether the relationship was continuous. We compute two measures of duration: months in the current relationship type (e.g., months dating, months cohabiting, etc.), and total months with this partner. The total months with the partner measure is computed by summing the number of days since the partner was first identified, and dividing by thirty.

vi. Nights spent together

At each interview, respondents were asked, in reference to the time since the prior interview, “How many nights did you spend all night sleeping in the same bed with _____?” We code this as a percent.

vii. Relationship type

Respondents were asked a series of questions about their relationship with their partner, referring to the prior week: whether they spent a lot of time together (time), whether they had agreed to have sex only with each other and no one else (exclusivity), whether they lived together (cohabitation), and whether they were engaged or married. We use the responses to these questions to form seven indicators of relationship type: Casual (low time, no exclusivity, no cohabitation), Dating (high time together, no exclusivity, no cohabitation), Long-Distance (low time together, exclusivity, no cohabitation), Serious (high time together, exclusivity, no cohabitation), Cohabiting, Engaged, or Married. Sometimes our respondents used these terms, even “married,” loosely. For example, when asked, “Last week you said that you were married to ____. Are you still married to ____?” more than one woman reported that she had never been married to that person.

viii. Instability

Any relationship that included a break—where the respondent reported having no partner or having a different partner in-between two distinct periods with a specific partner—is coded as having broken up. Respondents were asked each week whether they believed that their partner had sex with another partner; weeks with an affirmative answer are coded 1, other weeks are coded 0.

ix. Conflict

Each week, respondents were asked about conflict with their identified partner. Respondents who answered “yes” to “Did you and [partner name/initials] fight or have any arguments [during the period since the last interview]?” were asked follow-up questions about whether their partner swore at/called names/insulted them or treated them disrespectfully (disrespect); threatened them with violence (threats); and/or pushed, hit, or threw something that could hurt them (physical assault). We code each week as 1 (yes) or 0 (no) for each type of intimate partner violence (IPV).

x. Analytic strategy

A series of tables compares young women, partners, and relationships across the full sample, among those who got pregnant, and those who did not get pregnant. Table 1 describes the women in the RDSL sample; Table 2 describes their partners; and Table 3 describes their relationships with those partners. These comparisons allow us to assess whether the pregnant women were more disadvantaged than their peers; whether the fathers were older, less educated, and/or more likely to have existing children than non-fathers; and whether the pregnancy relationships were more serious, more unstable, or more violent than the non-pregnancy relationships.

Table 2.

Partner Characteristics

| All partners (n=2,499) |

Did not father a pregnancy (n=2,305 partners) |

Fathered a pregnancy (n=194 partners) |

Non-father partners of pregnant respondents (n=363 partners) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||||||

| Proportion/Mean | SD | Min | Max | Proportion/Mean | ↔ sig. diff. |

Proportion/Mean | ↔ sig. diff. |

Proportion/Mean | |

|

Number of Pregnancies Fathered with Respondent

| |||||||||

| 0 | 92% | 100% | 0% | – | |||||

| 1 | 7% | 0% | 89% | – | |||||

| 2 | 1% | 0% | 10% | – | |||||

| 3+ | .04% | 0% | 1% | – | |||||

| Total | 100% | 100% | 100% | – | |||||

|

Partner Characteristics | |||||||||

| Age difference (in years) | 2.20 | 3.54 | −5.87 | 33.24 | 2.11 | *** | 3.25 | *** | 2.51 |

| Education (in years) | 12.49 | .02 | 10.00 | 14.00 | 12.53 | *** | 12.04 | * | 12.25 |

| Existing children (prior to this relationship) | .14 | 0 | 1 | .14 | ns | .18 | ns | .21 | |

|

Race | |||||||||

| Black | .36 | 0 | 1 | .35 | ** | .45 | ns | .43 | |

Notes:

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001;

two-tailed independent samples t-tests

ns not significant

Table 3.

Relationship Characteristics

| All relationships (n = 2,499) |

Relationships that did not produce a pregnancy (n = 2,305) |

Relationships that produced a pregnancy (n = 216) |

Relationships that did not produce a pregnancy, among pregnant women (n = 363) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||

| Proportion/Mean | Proportion/Mean | ↔ sig. diff. |

Proportion/Mean | ↔ sig. diff. |

Proportion/Mean | |

|

Seriousness

| ||||||

| Nights spent together (%) | .25 | .22 | *** | .58 | *** | .20 |

| Total duration (in months) | 9.23 | 8.15 | *** | 22.43 | *** | 4.52 |

| Relationship type | ||||||

| Casual | 34% | 36% | *** | 10% | *** | 37% |

| Dating | 13% | 14% | *** | 4% | *** | 18% |

| Long-Distance | 16% | 17% | ** | 10% | * | 17% |

| Serious | 19% | 19% | 17% | 17% | ||

| Cohabiting | 9% | 8% | *** | 21% | *** | 5% |

| Engaged | 6% | 5% | *** | 23% | *** | 5% |

| Married | 3% | 2% | *** | 16% | *** | 2% |

|

Instability | ||||||

| Broke up (ever) | 81% | 83% | *** | 60% | *** | 94% |

| Broke up and got back together (ever) | 5% | 4% | *** | 21% | *** | 1% |

| Partner had sex with another partner (ever) | 20% | 20% | *** | 27% | 29% | |

|

Conflict | ||||||

| Fought | 44% | 41% | *** | 75% | *** | 34% |

| Disrespect | 20% | 18% | *** | 48% | *** | 12% |

| Threats | 5% | 4% | *** | 18% | *** | 4% |

| Physical Assault | 6% | 5% | *** | 21% | *** | 5% |

Notes:

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001;

p < .10;

two-tailed independent samples t-tests

All characteristics are measured at the last observation/end of the relationship.

Tables 2 and 3 compare the partners that fathered the pregnancies to the other partners of pregnant women who did not father their pregnancies, and the relationships that led to pregnancies to the other relationships of pregnant women that did not lead to pregnancy. This comparison, like a fixed-effects model, allows us to assess whether the most unstable, conflictual and/or serious relationships, along with the oldest and least educated partners, have the highest risk of pregnancy, or instead that women who become pregnant at a young age tend to have unstable/serious relationships and older/less educated partners, regardless of pregnancy. Table 4 compares the pregnancy relationships before and after the pregnancy occurred. This allows us to assess whether these relationships are serious, unstable, or conflictual from the start, and whether they deteriorate after the pregnancy. We use independent samples t-tests to test the statistical significance of all comparisons. Table 5 presents a cross tabulation of relationship type at the time of pregnancy and at the end of the relationship (or end of the Study).

Table 4.

Characteristics of Relationships that Produced Pregnancies, before and after Pregnancy (n = 216)

| At the time of pregnancy | After the Pregnancy | ||

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||

| Proportion/Mean | ↔ sig. diff. |

Proportion/Mean | |

|

Seriousness

| |||

| Nights spent together (%) | 55% | ns | 58% |

| Total duration (in months) | 15.71 | *** | 7.29 |

| Relationship type | |||

| Casual | 6% | – | 10% |

| Dating | 2% | – | 4% |

| Long-Distance | 9% | – | 10% |

| Serious | 31% | – | 17% |

| Cohabiting | 21% | – | 21% |

| Engaged | 22% | – | 23% |

| Married | 9% | – | 16% |

|

Instability | |||

| Broke up | |||

| Broke up (total) | 19% | *** | 47% |

| Broke up and got back together | 19% | – | 28% |

| Broke up and did not get back together | 0% | – | 33% |

| Partner had sex with another partner | 22% | ns | 25% |

|

Conflict | |||

| Unequal Decision-making | .05 | ns | .03 |

| Fighting | 74% | * | 66% |

| Disrespect | 40% | ns | 44% |

| Threats | 13% | † | 19% |

| Physical Assault | 16% | ns | 17% |

Notes:

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001;

p< .10;

two-tailed independent samples t-tests

ns not significant

no test

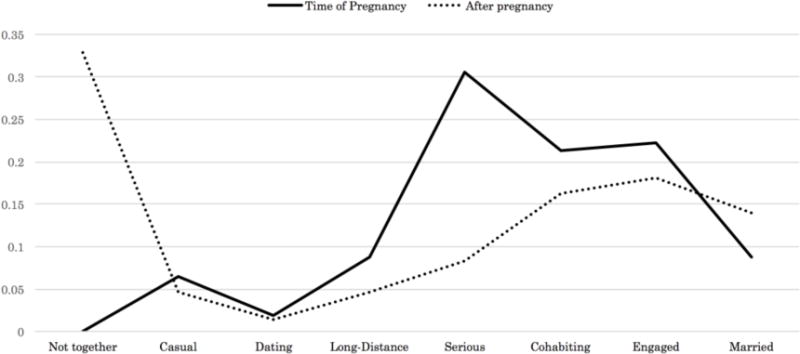

Table 5.

Cross-Tabulation of Relationship Type, before and after Pregnancy (n = 216 relationships)

|

V. Results

The first four columns in Table 1 describe the 880 respondents in our analytic sample. In the sample, 183 women reported 216 pregnancies; the vast majority of pregnant women reported only one pregnancy, but 14% reported two, and 2% reported three or more.

Ages ranged from 18.12 to 20.34, with a mean of 19.18. Thirty-four percent of the young women reported their race as Black or African American. Thirty-six percent reported that their family received public assistance at some point during their childhood; 48% did not grow up with two parents; 36% had a mother who gave birth as a teen; and 9% reported that their mother did not complete high school. The childhood disadvantage index ranged from 0 to 4, with a mean of 1.28. Fifty-eight percent of respondents were highly religious. High school GPA ranged from 0 to 4.17, with a mean of 3.12. Twenty-six percent were receiving public assistance at the beginning of the study period. Fifty-eight percent were enrolled in a 2- or 4-year post-secondary program. Fifty percent were employed. Fifty-three percent of respondents were sixteen or younger when they reported having sex for the first time (“at first sex” in Table 1); 61% reported two or more sexual partners; 49% had at some point had sexual intercourse without using some method of birth control; and 26% reported one or more prior pregnancies.

The final two columns compare the non-pregnant versus pregnant young women in the sample. The vast majority of these measures are significantly different for the non-pregnant versus pregnant. Although the demographics and religiosity of the groups were similar, the pregnant respondents, relative to the non-pregnant, had more childhood disadvantages, disadvantaged current socioeconomic characteristics, and adolescent experiences that put them at a high risk for pregnancy. This is consistent with previous research on young pregnancy, suggesting that socioeconomically advantaged women delay childbearing because they have more degree-granting post-secondary educational opportunities, which result in their being enrolled in school longer relative to their otherwise similar peers.

Table 2 describes the 2,499 partners reported by the 880 women in our analytic sample, and compares the 2,305 partners who did not father a pregnancy to the 194 partners that fathered the 216 pregnancies, and also to 363 other partners of the pregnant young women who did not father their pregnancies.

The age difference ranged from −5.87 (respondent was 5.87 years older than her partner) to 33.24 (partner was 33.24 years older than the respondent), with a mean of 2.2 years older. The mean years of education for partners was 12.49 years. Fourteen percent had existing children from a prior relationship. Thirty-six percent of the partners were Black.

Among those who fathered a pregnancy, the vast majority (89%) fathered only one pregnancy during the study period, nineteen (10%) fathered two pregnancies; and only two partners (1%) fathered three or more pregnancies. Those who fathered a pregnancy differed significantly from those who did not father a pregnancy. Fathers were older and less educated. They were more likely to have existing children from a prior relationship (18%), relative to only 14% of those who did not father a pregnancy, but this difference was not statistically significant. They were also more likely to be Black, which is not surprising given that the Black women in the study had higher pregnancy rates and racial homogamy is high in intimate relationships in the U.S.32

Compared to the non-father partners of pregnant respondents, those who fathered a pregnancy were also older and slightly less educated. They were less likely to have existing children (18%), relative to of non-fathers of pregnant respondents (21%), but this difference was not statistically significant. This suggests that young women who get pregnant are likely to have older and less educated partners. But, it also suggests that partners who father a pregnancy are even older and less educated than the pregnant young woman’s other partners—young women are particularly likely to get pregnant with their oldest and least educated partners.

The first column of Table 3 describes the 2,499 relationships reported by the young women during the two-and-a-half year study period. On average, young women spent 25% of the nights during their relationship sleeping in the same bed as their partner. The mean total duration of the relationships was 9.23 months, but some of these relationships were censored during the study period—that is, they were ongoing at the beginning of the study (left censored), were ongoing at the end of the study (right censored), or were ongoing at both the beginning and end of the study period (right and left censored). In all, 62% of relationships were observed in their entirety, with a mean duration of about two months (not shown in tables). Thirteen percent were ongoing at the beginning of the study but ended during the study period, and they averaged nearly two years in duration. Thirteen percent were ongoing at the end of the study, with a mean duration of about ten months. Twelve percent of relationships were both right and left censored—in other words, ongoing throughout the entire study period—with the longest mean duration of nearly three years.

We also classified each relationship at the end of the period of observation (the end of the relationship, or the end of the Study if right-censored) into seven categories. We defined a relationship as “casual” if the woman reported that she had not spent a lot of time with the partner and they had not agreed to be sexually exclusive (34%). “Dating” indicates that they spent time together but had not agreed to be sexually exclusive (13%). “Long-Distance” relationships are where the couple did not spend a lot of time together but had agreed to be sexually exclusive (16%). Semi-structured interviews with the young women suggested that most of these relationships were boyfriends away in the military, at college, or working in another area. “Serious” relationships indicated spending a lot of time together and sexual exclusivity (19%). When young women said that they had no address separate from their partner, the relationship is categorized as “cohabiting” (9%). Note that all cohabiting relationships involved spending a lot of time together and sexual exclusivity. “Engaged” relationships indicate that the couple agreed to get married in the future (6%), and young women reported whether they were “married” to the partner (3%). Overall, the least serious types of relationships were most common among this age group, with 50% involving no agreement to be sexually exclusive (casual and dating relationships).

In terms of instability, 81% of the relationships broke up at some point (keeping in mind that 25% of relationships were ongoing at the end of the study period, many of which will break up in the future). In 5% of the relationships the couple broke up and got back together at some point. Women reported that their partner had sex with someone else in 20% of their relationships. In terms of conflict, 44% of relationships involved fighting, 20% involved disrespect, 5% included threats, and 6% included physical assault.

The remaining columns in Table 3 compare three types of relationships: those that did not produce a pregnancy, those that produced a pregnancy, and those that did not produce a pregnancy but were experienced by women who became pregnant.

The relationships that produced pregnancies lasted a mean of 22.43 months, which was substantially longer than the non-pregnancy relationships and the pregnant women’s non-pregnancy relationships. Of course, given the length of these relationships, it makes sense that the vast majority of the relationships are censored. Although the duration of the left-censored relationships is reported by the respondents themselves, the right-censored relationships are ongoing, and thus we cannot know their total duration. Even looking within these censorship groups, the pregnancy relationships are substantially longer. Pregnant women’s other relationships that did not produce pregnancies are particularly short (mean = 4.52 months).

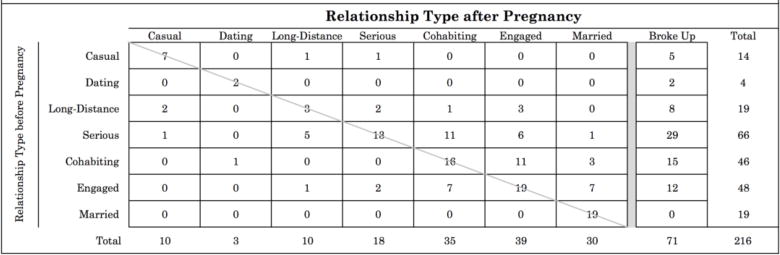

In terms of relationship type, two strong patterns are apparent. First, the 216 relationships that produced pregnancies are relatively serious and long-lasting—only 14% occurred in a relationship that was not sexually exclusive (casual or dating). Another 27% occurred to long-distance or serious relationships. Sixty percent occurred in cohabiting, engaged, or married relationships. Second, the 216 relationships that produced a pregnancy were more serious and longer than the 2,305 relationships that did not produce a pregnancy, and more serious and longer than the 194 pregnant women’s other 363 relationships that did not produce pregnancy. With so many categories, the distributions across relationship type are difficult to compare, so Figure 1 presents a graph of those distributions. The solid line corresponds to the 2,305 non-pregnancy relationships, the dotted line to the 216 pregnancy relationships, and the dashed line to the 363 non-pregnancy relationships of pregnant women. The non-pregnancy relationships (solid) and non-pregnancy relationships of pregnant women (dashed) lines are quite similar. The dotted line, on the other hand, is highly skewed toward the serious end of the distribution, relative to both other lines. In other words, the pregnancy relationships were much more serious than the young women’s other relationships, even the pregnant women’s other relationships that did not produce a pregnancy.

Figure 1.

Distribution of Relationship Type

Pregnancy relationships are more stable than the non-pregnancy relationships: 60% broke up at some point in the relationship, relative to 83% of relationships that did not produce a pregnancy, and 94% of pregnant women’s other relationships that did not produce a pregnancy. Twenty-one percent of the pregnancy relationships got back together after a break-up. The remaining 39% broke up after the pregnancy and did not get back together. But the pregnancy relationships also involve more nonexclusive sexual behavior by the partners. Twenty percent of partners had sex with another partner during non-pregnancy relationships, but did so in 27% of the pregnancy relationships. The pregnant women’s non-pregnancy relationships are the most unstable of all—94% broke up, and only 1% got back together. Twenty-nine percent of partners in those relationships had sex with another partner during the relationship.

Pregnancy relationships are the most conflictual. While less than half (41%) of the non-pregnancy relationships included fighting, and only one-third (34%) of the pregnant women’s non-pregnancy relationships involved fighting, 75% of the pregnancy relationships involved fighting. Similarly, pregnancy relationships included more than twice the amount disrespect as non-pregnancy relationships, more than triple the rate of threats, and four times the rate of physical assault. Interestingly, it is not that the women who got pregnant had violent relationships in general—their non-pregnancy relationships are much less violent than the relationships that led to pregnancy.

Table 4 compares the pregnancy relationships at two time points: before the pregnancy (summary measures from the beginning of the relationship up to the time of pregnancy), and after the pregnancy (summary measures from just after the pregnancy until the end of the relationship/period of observation).

The pregnancy relationships are similar over time in terms of the percent of nights spent sleeping in the same bed—slightly more than half. On average, these relationships had been ongoing for sixteen months at the time of pregnancy. However, the relationships only lasted an average of 7.25 months after the pregnancy. The modal relationship at the time of pregnancy is “serious”—recall that serious relationships are defined as spending time together and agreeing to have sex only with each other, but not cohabiting. Approximately one-third (31%) of pregnancies occurred to partners in this type of relationship at the time of pregnancy. Very few pregnancies occurred in casual or dating relationships, only 8% total. These are the only two relationship types that do not involve a promise of sexual exclusivity. Few young women are married at these ages, so few pregnancies occurred to married couples. The majority of the pregnancies occurred in serious, cohabiting, and engaged relationships.

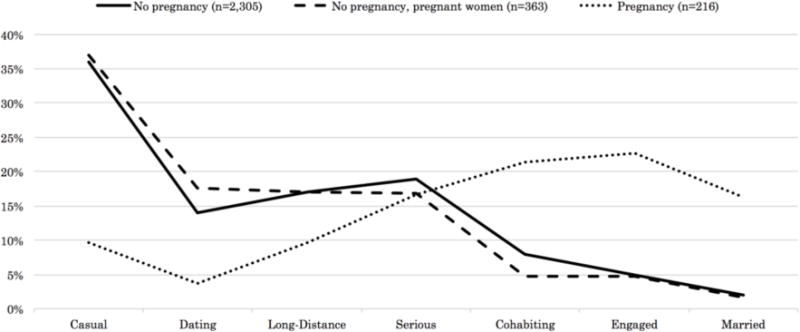

Because it is difficult to compare two distributions with seven categories each, we present the comparison graphically in Figure 2. The solid line represents the relationship type distribution at the time of pregnancy, and the dotted line represents the relationship type distribution after the pregnancy (at the end of the period of observation, either breakup or right censoring). The solid line shows that the bulk of the relationships are in the middle of the distribution at the time of pregnancy—they tend to be serious, along with a substantial fraction either cohabiting or engaged. The dotted line shows that few relationships remained in the serious category, and many relationships broke up (“not together”).

Figure 2.

Distribution of Relationship Type Before and After Pregnancy (N=216)

Table 5 shows this in greater detail, with a cross-tabulation of change over time in the 216 relationships. Relationships in the upper right triangle became more serious, while those in the lower left triangle became less serious. Forty-seven (22%) of the 216 relationships became more serious, 79 (37%) stayed the same, and 90 (42%) became less serious or broke up.

Table 4 further describes the instability in these relationships. Nearly half (47%) broke up after the pregnancy, 28% broke up and got back together, and 33% broke up but did not get back together. (Note that some relationships broke up and got back together, and then later broke up and did not get back together, so the two categories do not sum to the total percent who ever broke up.) Of course, more of these relationships will eventually break up, as our period of observation is relatively short. Additionally, 22% of women reported that their partners had sex with another partner at some point before the pregnancy, and 25% reported it after the pregnancy. Although general fighting decreased slightly, disrespect, threats, and physical assault increased after the pregnancy.

Conclusion

Young women who become pregnant in their late teens and early twenties have older and less educated partners. Consistent with prior research, these young women tend to be in long-term, serious relationships with these partners at the time of pregnancy.33 These intimate relationships tend to become less serious or break up after the pregnancy. The relationships are violent before pregnancy, and become more violent after pregnancy.

These young women’s other partners, who did not get them pregnant, are slightly more educated and younger than those who fathered their pregnancies. Their intimate relationships that did not lead to pregnancy, however, are similar to non-pregnancy relationships among their peers in terms of seriousness, instability, and violence. In other words, if pregnancy could have been avoided in those relationships that are most serious, unstable, and conflictual, those young women may have been in better relationships when they became mothers.

The low quality and deteriorating nature of the relationships that are overrepresented among young pregnant women have important implications for family policy. First, because pregnancies occur in relationships that are more unstable and conflictual than young women’s other relationships, and this is bad for children, continuing support for women who want to delay pregnancy is crucial for child well-being. Just before they became pregnant, only about 10% of the pregnant RDSL women stated a strong desire to get pregnant. Among those, only about half reported after the pregnancy that they had wanted to get pregnant. Contraceptive rights are essential for all women, but in light of the legacy of medical experimentation and forced sterilization of poor and minority women in the U.S. (and abroad),34 it is especially important to maintain a strong focus on choice.

Second, young women who do become pregnant do so within a wide range of intimate relationship situations. Some of these relationships are stable and serious. For example, RDSL young women who were married when they got pregnant were still married when the study ended. However, many of these relationships are quite conflictual—in both absolute and relative terms. Nearly half involve disrespect, and one-fifth involved physical assault. They are four times more violent, in terms of physical assault, than other intimate relationships in this age group. This level of conflict and violence necessitates flexible family policies that take account of individual situations, and attempt to maximize the strengths of families and neutralize their weaknesses. For example, mandating father involvement is not in children’s best interests if it increases contact with violent fathers, or increases violence between their parents. Interventions that focus on communication or co-parenting skills among parents are most appropriate for relationships that are not violent.

Overall, young women get pregnant and give birth for a wide variety of reasons, in a wide variety of situations. Structural inequalities and unequal opportunities shape preferences about whether and when to become a parent. Inequality also shapes young women’s ability to implement those preferences. Moreover, if and when they do become parents, inequality shapes their access to resources that affect their children’s well-being. These analyses have highlighted inequality in access to romantic partners and high quality intimate relationships. Family policies should, in general, attempt to offset these inequalities in an attempt to improve women’s and their children’s overall well-being.

References

- 1.Curtin Sally C, et al. U.S. Dep’t of Health & Hum. Services Recent Declines in Nonmarital Childbearing in The United States. 2014;2 https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db162.pdf. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carlson Marcia J, England Paula. Social Class and Family Patterns in the United States. In: Carlson Marcia J, England Paula., editors. Social Class And CHanging Families in An Unequal America. 2011. pp. 3–5. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rector Robert. The Heritage found, Marriage: America’s Greatest Weapon Against Child Poverty. 2012 Sep 5;7 tbl.6. http://thf_media.s3.amazonaws.com/2012/pdf/sr117.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 4.See Fragile Families & Child Wellbeing Study. Princeton Univ. & Columbia Univ.; http://www.fragilefamilies.princeton.edu/about (last visited Apr. 5, 2017) [Google Scholar]

- 5.McLanahan Sara. Family Instability and Complexity After a Nonmarital Birth: Outcomes for Children in Fragile Families. Social Class and Changing Families in an Unequal America. :124–26. supra note 2. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Edin Kathryn, Kefalas Maria. Promises I Can Keep: Why Poor Women Put Motherhood Before Marriage. 2005;6 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Id. at 11.

- 8.Id. at 9.

- 9.Edin Kathryn, Nelson Timothy J. Doing The Best I Can: Fatherhood in The Inner City. 2013:165–74. [Google Scholar]

- 10.McLanahan Sara, et al. Introducing the Issue. 20 The Future of Children. 2010;3:4–5. discussing empirical research on the causes and consequences of nonmarital child births, including a study that involved interviewing parents of approximately 5,000 newborns in large cities and subsequent follow-up interviews. [Google Scholar]

- 11.We focus on pregnancies in our analyses, not births, because the RDSL period of observation is relatively short.

- 12.McLanahan Introducing the Issue. :8–9. supra note 10. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Edin & Nelson, supra note 9, at 103–29 (detailing stories about fathers’ involvement and provision of care to their child despite a lack of economic resources).

- 14.McLanahan Family Instability and Complexity After a Nonmarital Birth. :124–26. supra note 5. describing factors that contribute to a recorded drop in the proportion of unmarried fathers who live with their children from 51% at year one to 36% at year five. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lerman Robert I. Capabilities and Contributions of Unwed Fathers. 20 Future of Child. 2010;63:64. doi: 10.1353/foc.2010.0001. explaining that unmarried fathers are less educated when compared to all men. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Id.

- 17.Benjamin Guzzo Karen. New Partners, More Kids: Multiple-Partner Fertility in the United States. 654 Annals of The Am Acad of Pol & Soc Sci. 2014;66:73–77. doi: 10.1177/0002716214525571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Duberstein Lindberg Laura, et al. Age Differences Between Minors Who Give Birth and Their Adult Partners. 29 Fam Plan Persp. 1997;61:61–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.See, e.g.; McLanahan Family Instability and Complexity After a Nonmarital Birth. :108–09. supra note 5. providing a brief overview of research on unmarried mothers. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Id. at 115.

- 21.Id. at 117 (reporting that despite “high hopes” at the outset, only fifteen percent of couples in the study were married five years later, and only one third were still romantically involved).

- 22.Edin & Nelson, supra note 9, at 17.

- 23.Hill Heather D. Steppin’ Out: Infidelity and Sexual Jealousy Among Unmarried Parents. In: England Paula, Edin Kathryn., editors. Unmarried Couples With Children. 2007. pp. 112–14. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Id. at 108–09.

- 25.Musick Kelly, Meier Ann. Are Both Parents Always Better than One? Parental Conflict and Young Adult Well-Being. 39 Soc Sci Res. 2010;814:815–16. 822–24. doi: 10.1016/j.ssresearch.2010.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Waldfogel Jane, et al. Fragile Families and Child Wellbeing. 20 Future of Child. 2010;87:87. doi: 10.1353/foc.2010.0002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Id. at 93–94.

- 28.Id. at 97–98.

- 29.See id. at 93–94 (summarizing research on the relative importance of family structure and family stability on child well-being).

- 30.See id. at 103 (discussing studies showing that family stability is a strong factor in child cognitive and health outcomes).

- 31.See, e.g.; Kusunoki Yasamin, et al. Black-White Differences in Sex and Contraceptive Use Among Young Women. 53 Demography. 2016:1399. doi: 10.1007/s13524-016-0507-5. analyzing racial and sociodemographic differences in sexual and contraceptive behavior. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Barber Jennifer S, et al. Black-White Differences in Attitudes Related to Pregnancy Among Young Women. 52 Demography. 2015;751 doi: 10.1007/s13524-015-0391-4. studying Black-White differences in attitudes toward pregnancy and the effects of childhood socioeconomic status, adolescent experiences related to pregnancy, and other factors. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Anderson Ashton, et al. Political Ideology and Racial Preferences in Online Dating. 1 Soc Sci. 2014;28 [Google Scholar]

- 33.McLanahan Sara, Beck Audrey N. Parental Relationships in Fragile Families. 20 Future Child. 2010;17:18–19. doi: 10.1353/foc.2010.0007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.See Barber et al. supra note 31, at 5–7.