A 33-year-old man with HIV/AIDS (CD4 50) with a recent diagnosis of disseminated mycobacterium avium complex presented 3 months later with headaches, new-onset seizures, right-sided blindness, and flaccid lower extremity paralysis. Lumbar puncture showed a lymphocytic pleocytosis and an elevated protein of 887.

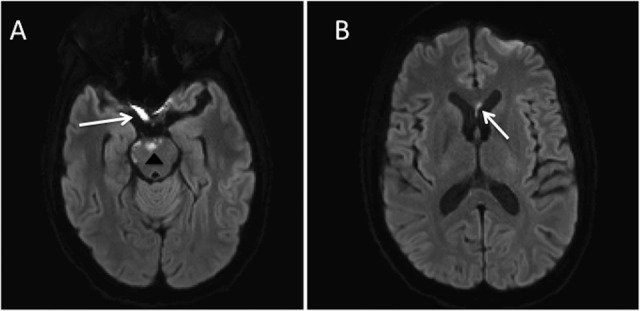

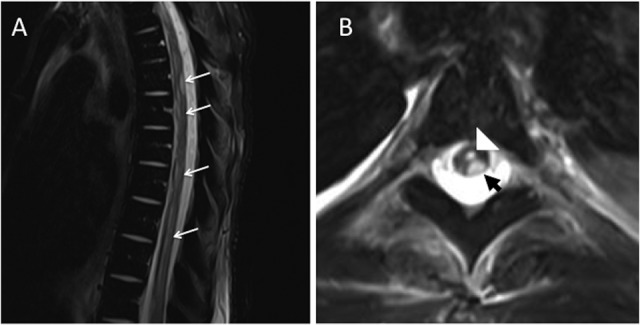

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain demonstrated multifocal small-vessel territory ischemic infarcts (Figure 1). Magnetic resonance angiography demonstrated a mild beaded appearance of the intracranial vasculature most prominent in the right M1 branch of the middle cerebral artery. These findings are consistent with a mixed large-vessel and small-vessel vasculopathy. T2-weighted MRI of the thoracic spine demonstrated cord signal abnormalities (Figure 2), consistent with longitudinally extensive transverse myelitis. Central canal prominence (Figure 2B) may be related to alterations in cerebrospinal fluid flow dynamics. Cerebrospinal fluid polymerase chain reaction was confirmatory for varicella zoster virus. The patient was treated with parenteral and then oral acyclovir; however, his neurologic deficits of lower extremity paralysis and right monocular vision loss still persisted.

Figure 1.

A, Axial diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging (DW-MRI) demonstrates multifocal areas of restricted diffusion involving the pons (arrowhead) and right prechiasmatic optic nerve (arrow). B, There was additionally restricted diffusion in the corpus callosum (arrow).

Figure 2.

A, Sagittal T2-weighted magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the thoracic spine demonstrates a long segment of T2 hyperintense cord signal abnormality (white arrows). B, Axial T2-weighted MRIs of the thoracic spine (T5-T6 level) demonstrate T2 hyperintense cord signal abnormality, which predominantly involves the left dorsal column (short arrow). Prominence of the central canal is also seen (white arrowhead).

Varicella zoster virus reactivation can result in myriad neurologic sequelae, including vasculopathy, ischemic optic neuropathy, and transverse myelitis.1,2 This patient has involvement of the optic nerve, which is rare. The pathophysiology is ischemic optic neuropathy likely due to involvement of the temporal artery, which can mimic giant cell arteritis.1 Restricted diffusion can be used to help differentiate ischemic optic neuropathy from optic neuritis, which can present similarly and also occurs in the immunocompromised.1,3-6

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1. Gilden D, Nagel MA, Cohrs RJ, Mahalingam R. The variegate neurological manifestations of varicella zoster virus infection. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2013;13(9):374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Gilden DH, Kleinschmidt-DeMasters BK, LaGuardia JJ, Mahalingam R, Cohrs RJ. Neurologic complications of the reactivation of varicella-zoster virus. N Engl J Med. 2000;342(9):635–645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Horton JC, Douglas VC, Cha S. Reduced apparent diffusion coefficient in NMO-associated optic neuropathy. J Neuroophthalmol. 2015;35(1):101–102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Franco-Paredes C, Bellehemeur T, Merchant A, Sanghi P, DiazGranados C, Rimland D. Aseptic meningitis and optic neuritis preceding varicella-zoster progressive outer retinal necrosis in a patient with AIDS. AIDS. 2002;16(7):1045–1049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Duda JF, Castro JG. Bilateral retrobulbar optic neuritis caused by varicella zoster virus in a patient with AIDS. Br J Med Med Res. 2015;5(11):1381–1386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Liu JZ, Brown P, Tselis A. Unilateral retrobulbar optic neuritis due to varicella zoster virus in a patient with AIDS: a case report and review of the literature. J Neurol Sci. 2005;237(1-2):97–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]