Abstract

Carotid artery stenting (CAS) has been recommended as an alternative treatment to carotid endarterectomy for patients with significant carotid stenosis. Only a few studies have analyzed clinical/anatomical and technical variables that affect perioperative outcomes of CAS. Following a comprehensive Medline search, it was reported that clinical factors, including age of >80 years, chronic renal failure, diabetes mellitus, symptomatic indications, and procedures performed within 2 weeks of transient ischemic attack symptoms, are associated with high perioperative stroke and death rates. They also highlighted that angiographic variables, e.g., ulcerated and calcified plaques, left carotid intervention, >90% stenosis, >10-mm target lesion length, ostial involvement, type III aortic arch, and >60°-angulated internal carotid and common carotid arteries, are predictors of increased stroke rates. Technical factors associated with increased perioperative risk of stroke include percutaneous transluminal angioplasty (PTA) without embolic protection devices, PTA before stent placement, and the use of multiple stents. This review describes the most widely quoted data in defining various predictors of perioperative stroke and death after CAS. (This is a review article based on the invited lecture of the 45th Annual Meeting of Japanese Society for Vascular Surgery.)

Keywords: carotid artery stenting, perioperative stroke, perioperative death

Introduction

Carotid artery stenting (CAS) has been recommended as an alternative to carotid endarterectomy (CEA) for treating patients with significant carotid stenosis, particularly in high-risk surgical patients.1–3) A proper selection of these patients is critical to successful CAS outcomes. However, only a few studies have analyzed the various clinical/anatomical and technical variables that affect perioperative outcomes of CAS.

Following a comprehensive Medline search of over a 15-year period, Khan and Qureshi3) reported that clinical factors, including age of >80 years, diabetes mellitus, chronic renal failure, and symptomatic indications, are associated with high perioperative stroke and death rates. The authors also suggested that procedures performed within 2 weeks of transient ischemic attack (TIA) symptoms are associated with increased 30-day perioperative stroke and death rates. They concluded that angiographic variables, including ulcerated and calcified plaques, left carotid artery intervention, >10-mm target lesion length, >90% stenosis, ostial involvement, type III aortic arch, and >60°-angulated internal carotid and common carotid arteries, are predictors of increased perioperative stroke rates. Furthermore, they reported that technical factors related to increased perioperative risk of stroke include percutaneous transluminal angioplasty (PTA) without embolic protection devices, PTA before stent placement, and the use of multiple stents for the target lesion. In another study, Gray et al.2) obtained similar results based on the Carotid RX Acculink/Accunet Post-Approval Trial to Uncover Unanticipated or Rate Events (CAPTURE) registry, a prospective multicenter registry created to evaluate CAS outcomes in a non-investigational setting, after device approval for high-risk surgical patients (both asymptomatic with >80% stenosis and symptomatic with ≥50% stenosis). The study enrolled 3,500 patients from 144 sites served by 353 physicians of varying specialty backgrounds and experience. The authors found that adverse outcomes can be predicted by factors, such as being a symptomatic patient, age, predilatation prior to embolic protection device placement, use of multiple stents, and time from symptoms to the CAS procedure.2) Furthermore, Aronow et al.4) pooled carotid stent data from four Cordis-sponsored trials that included 2,104 patients (24% of whom were symptomatic) to characterize predictors of perioperative stroke. They showed that the risk of perioperative neurological outcomes among symptomatic patients declined with increasing time between the incidence of the neurological event and the CAS procedure. In addition, using a multivariable logistic regression model, the authors found that advanced age, visible thrombus on angiography in symptomatic patients, procedural TIA, >30% final residual stenosis, procedural use of glycoprotein IIb and IIIa inhibitors, and preprocedural use of protamine or vasopressors are predictive of perioperative neurological events.4)

Our present study describes the most widely quoted data in defining various predictors of perioperative stroke and death after CAS.

Clinical Predictors of Perioperative Stroke and Death after CAS

Age

Several studies have found that patients aged ≥80 years undergoing CAS have significantly high perioperative stroke rates.2,5–7) Notably, the evaluation of the CAPTURE registry revealed a 30-day stroke rate of 7.2% in patients aged ≥80 years compared with 4% in those aged <80 years.2) Similarly, in the CAPTURE 2 study, a perioperative stroke rate of 3.8% was found in patients aged >80 years compared with that of 2.4% in patients aged <80 years.5) Another study, the SPACE study (Stent-Protected Angioplasty versus Carotid Endarterectomy in Symptomatic Patients), showed that patients aged >68 years were at a high risk of perioperative stroke and death after CAS.6) The Carotid Revascularization Endarterectomy versus Stenting Trial (CREST) also showed that patients aged ≥70 years were at a higher risk of stroke at 4 years after CAS than patients aged <70 years.7) Furthermore, the CAPTURE 2 trial also compared the incidence of calcified carotid target lesions and type III aortic arch lesions in patients aged <80 years and those aged >80 years. It was found that compared with patients in the younger age group, those in the older age group had a higher incidence of calcified carotid target lesions (22% versus 27%) and type III aortic arch lesions (10% versus 20%). The authors hypothesized that these findings accounted for the higher incidence of stroke and death in the older patients than in the younger patients. Comparable observations were made by the SPACE investigators; however, the results were questioned given the low contralateral stroke rate in the older patients.5,6) Other studies have demonstrated that advanced age is an independent predictor of procedural stroke.8–12) However, it should be noted that although most prospective studies have shown a high rate of stroke and death among patients aged >80 years, these data do not support complete exclusion of these patients from undergoing CAS. Notably, the Stenting and Angioplasty with Protection in Patients at High Risk for Endarterectomy (SAPPHIRE) study demonstrated a lower rate of stroke and death in high-risk surgical patients at 1 month and at 1–3 years after CAS than that after CEA.1) Wang et al.13) analyzed high-risk surgical patients from the Medicare population and demonstrated no difference in 1-year stroke and death rates between patients aged >80 years and those aged <80 years. These data supported the importance of CAS in high-risk surgical patients aged >80 years in the current practice; however, caution is usually advised.

Sex

Higher perioperative stroke rates in females compared with that in males has been controversial. A subgroup analysis of the CREST revealed that women tended to have a high 4-year stroke rate (5.5% in women versus 3.3% in men).14) The observed trend can be explained by the smaller diameter of the carotid artery in women than in men.15) Indeed, a similar observation was made by Dua et al.16) who analyzed data from 1,756,445 patients undergoing CEA or CAS between 1998 and 2012. The data was derived from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality National Inpatient Sample and State Ambulatory Services Databases and included 1,583,614 asymptomatic CEA, 7,317 asymptomatic CAS, 162,362 symptomatic CEA, and 3,149 symptomatic CAS patients. The analysis showed that for risk-matched asymptomatic and symptomatic patients, female sex (p<0.001) was associated with a higher stroke risk than male sex. They also indicated that female sex was one of the strongest overall predictors of adverse outcome after CAS (odds ratio, 21.39 for death; p<0.001).16) However, it should be noted no other trial has demonstrated a significant difference between men and women in the 30-day stroke and death rates after CAS. Although the CAPTURE registry revealed a perioperative stroke rate of 5.6% for women versus 4.3% for men,2) similar findings were also found in the SPACE trial that showed no significant difference in perioperative stroke rates between women and men (8.2% versus 6.4%).6) In addition, data from a nationwide registry showed that perioperative stroke rates between women and men were comparable (2.7% versus 2%).17)

Indication and timing of CAS

Several studies have demonstrated that after CAS, symptomatic patients have a higher 30-day stroke rate than asymptomatic patients. The SAPPHIRE trial demonstrated that the cumulative incidence of stroke, death, and/or myocardial infarction (MI) was 16.8% in symptomatic patients versus 9.9% in asymptomatic patients at 1 year after CAS.1) A pooled data analysis of 2,104 patients included in four major Cordis-sponsored studies (SAPPHIRE, CASES, CNC, and ADVANCE), of which 24% of patients were symptomatic, revealed a 30-day stroke/death rate of 3.8% in asymptomatic patients versus 5.3% in symptomatic patients.4) The analysis further revealed that symptomatic patients had higher stroke rates of 8.8% when CAS was performed within 14 days of the index event compared with 5.9% when CAS was performed within 180 days. The CREST7) that included symptomatic patients (53%) who underwent CAS within 180 days of an ischemic event revealed that the stroke rate at 1 month was 5.5%. Interestingly, the CREST reported a lower 4-year stroke/death rate of 4.5% in asymptomatic patients compared with 8% in symptomatic patients. Khan and Qureshi in their review of CAS trials found that the 30-day stroke rate was 8.3% in symptomatic patients compared with 6% in asymptomatic patients.3) In a subgroup analysis of the pro-CAS data, Theiss et al.12) concluded that the hospital mortality and stroke rate was 3.6% and that prior symptoms were significant predictors of perioperative stroke and death. Several single-center studies have confirmed that CAS for symptomatic patients is associated with a higher stroke rate than CAS for asymptomatic patients.18–22) This higher stroke rate can be attributed to the higher carotid plaque vulnerability in these patients.

Cardiovascular risk factors

Several studies, including CAPTURE and CAPTURE 2 trials, have demonstrated that increasing perioperative stroke and death rates are not associated with a history of coronary artery disease, recent MI, unstable angina, pre-existing hypertension, hyperlipidemia, peripheral arterial disease, cigarette smoking, or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.2,5,8,10)

Chronic kidney disease (CKD)

The perioperative stroke and death rates after CAS in patients with CKD are variable. The CAPTURE registry included 8.2% patients with renal failure defined by history, and the CAPTURE 2 trial included 3.2% patients with renal failure defined by history; both failed to demonstrate that CKD had any effect on the 30-day stroke rates in patients undergoing CAS.2,5) Similarly, the SAPPHIRE trial, wherein 6% patients had renal failure as defined by history, did not identify an effect on the 30-day perioperative stroke rates after CAS in patients with renal failure. However, several single-center studies have demonstrated that patients with CKD, defined by a serum creatinine level of ≥1.3 mg/dL of blood, who were undergoing CAS had a higher 30-day stroke rate (11.1%) that those with normal renal function (0.6%).23,24) Similar observations were also made by our group.25)

Anatomical/Physiological Predictors of Perioperative Stroke/Death after CAS

Lesion location (left versus right) and ostial location

In a pooled data analysis of 34,398 CAS procedures, Naggara et al.26) showed that CAS of the left carotid artery stenosis was associated with a higher 30-day perioperative stroke/death rate than CAS of the right carotid artery stenosis (7.5% versus 6%). This was hypothesized to be due to the difficulty in accessing these lesions from the aortic arch. However, other studies did not report significant differences in stroke and death rates between patients undergoing right-sided CAS and those undergoing left-sided CAS.2,5) In a recent study, AbuRahma et al.27) showed that the 30-day perioperative stroke rate was 2.6% for all left-sided carotid lesions compared with 1.7% for right carotid lesions and that the 30-day major adverse event (MAE) rate (stroke, death, and MI) was 6.1% for left carotid lesions compared with 2.8% for right carotid lesions (p=0.1164). Further, the 30-day stroke rate was 3.1% for left internal carotid artery (ICA) lesions compared with 1.5% for right ICA lesions, and the 30-day MAE rate was 6.2% for left ICA lesions compared with 2.9% for right ICA lesions (p=0.1808). Thus, there was a trend toward lower stroke and MAE rates in right ICA lesions than in left ICA lesions.

Several studies have suggested that ostial involvement of the ICA at the maximum point of stenosis is associated with a high stroke rate.28,29) Setacci et al.28) observed a 30-day stroke rate of 8.8% in patients with ostial lesions compared with 2.5% in those without ostial lesions. This observation may be explained by the difficulty in engaging the ostium during catheter manipulation, resulting in an increased incidence of embolic particles; it may also be due to the stimulation of the baroreceptors within the carotid wall ostia, which may predispose patients to hemodynamic instability, as evident through bradycardia, hypertension/hypotension, or transient asystole, secondary to carotid sinus stimulation during the angioplasty and/or stent placement.

Aortic arch type

The EVA-3S trial (Endarterectomy versus Angioplasty in Patients with Symptomatic Severe Carotid Stenosis) reported that patients with a type III aortic arch had a higher incidence of 30-day perioperative stroke (17.2%) than those with type II and III aortic arches (8.1%).26) We could not demonstrate significant differences between arch types from our experience,27) which was, perhaps, secondary to the fact that most of our patients had type I and II aortic arches, with only 32 patients having type III aortic arch. It was also reported that aortic arch calcification was significantly higher in patients aged >80 years than in those aged <80 years (59% versus 30%), whereas a type III aortic arch is more common in patients aged >80 years than in those aged <80 years (82% versus 56%).30,31)

Target lesion length

A few studies have analyzed the link between carotid target lesion lengths and perioperative CAS outcomes and have found that longer lesions are associated with higher 30-day perioperative stroke rates.5,8,29,32) Mathur et al.8) found a 30-day stroke rate of 11.4% for lesions longer than 10–15 mm and a 3.8% rate for lesions shorter than 10 mm. These findings were confirmed by others. Notably, Sayeed et al.29) reported a stroke rate of 17% for lesions longer than 10–15 mm and that of 2.1% for lesions shorter than 10 mm, and Setacci et al.28) found a stroke rate of 5.6% for lesions longer than 10–15 mm and that of 2.6% for lesions shorter than 10 mm. Recently, Moore et al.32) reported the carotid angiographic characteristics in the CREST and discovered that perioperative stroke/death was more likely in longer target lesions in patients undergoing CAS than in patients undergoing CEA. They also found that the lesion length of ≥12.85 mm and lesions that were contiguous or sequential and non-contiguous extending remote from the bulb affected CAS outcomes more than CEA outcomes, indicating that the risk in CAS patients was higher than that in CEA patients, with an odds ratio of 3.42.

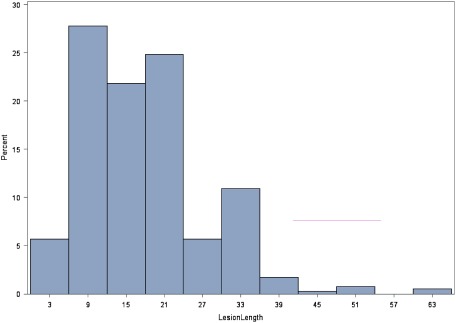

In a recent study,27) however, we could not demonstrate a correlation with lesion length, which may be attributed to the small sample size or to the fact that most of the treated lesions were <20–30 mm long (Fig. 1). It has been hypothesized that long lesions are associated with a greater atherosclerotic burden, which may lead to a higher risk of dislodgment of emboli during PTA and/or stent placement. Russjan et al.9) analyzed predictors of periprocedural brain lesions associated with carotid stenting in 127 patients who had undergone diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) before and on the day of CAS; the authors concluded that among all variables that were assessed, only age, length of stenosis, and carotid intima-media thickness significantly modified the risk of new lesions after stenting.9)

Fig. 1 Distribution of lesion length (in mm) in this series.

Target site calcification

A few studies have reported that a higher target site calcification is associated with a higher 30-day stroke rate. Setacci et al.28) found that the presence of target site calcification was associated with a higher 30-day perioperative stroke rate. Notably, they found a stroke rate of 6.5% in patients with target site calcification compared with 2.3% in patients without target site calcification. Similar findings were also reported by AbuRahma et al.27) In their study, patients with heavily calcified lesions had a 30-day stroke rate of 6.3%, whereas those with non-calcified/mildly calcified lesions had a stroke rate of 1.2% (p=0.046).

Severity of carotid stenosis/other lesion characteristics

A few studies2,5) have reported no difference between the mean severity of carotid stenosis and perioperative outcomes of CAS. Our study confirmed these findings.27) Theiss et al.12) also reported no statistical significance between perioperative outcomes and the side of CAS or the degree of carotid stenosis. However, in a single-center study, Mathur et al.8) showed that CAS performed for lesions with >90% stenosis was associated with higher 30-day perioperative stroke rates than CAS performed for lesions with <90% stenosis (14.9% versus 3.5%). Other carotid lesion characteristics, such as ulceration and irregularity, were related to an increasing incidence of periprocedural ischemic stroke. A single-center prospective registry revealed that the presence of lesion ulceration, as determined by angiography, was associated with a higher 30-day stroke rate of 7.9% after CAS compared with a lower rate of 2% in patients with no ulceration.28)

ICA/common carotid artery (CCA) angulation/tortuosity

Naggara et al.26) analyzed 262 patients from the EVA-3S trial and revealed that an ICA/CCA angulation of >60° was associated with a high 30-day stroke rate. Patients with >60° ICA/CCA angulation had a 30-day stroke rate of 10.7%, whereas those with <60° angulation had a rate of 2.3%. Other single-center studies found a higher 30-day stroke rate in patients with severe ICA/CCA angulation of >60° than in those with less severe angulation (13.6% versus 5.2%).31,33) This tortuosity or increasing angulation results in greater catheter manipulation during CAS, which may lead to a higher rate of perioperative stroke.

Hemodynamic instability

Hemodynamic instability during CAS may affect the incidence of perioperative stroke. Some authors have reported a higher incidence of periprocedural stroke in patients with pre- and post-procedural hypotension.34,35) However, other studies could not confirm these findings.2,5) Ullery et al.34) retrospectively analyzed 257 CAS procedures and reported the incidence, predictors, and outcomes of hemodynamic instability. In their study, the presence of periprocedural hemodynamic instability was defined by hypertension (systolic blood pressure of >160 mmHg), hypotension (systolic blood pressure of <90 mmHg), and/or bradycardia (heart rate of <60 beats per minute). A clinically significant hemodynamic instability was defined as periprocedural hemodynamic instability lasting longer than 1 h. The incidences of hypertension, hypotension, and bradycardia were 54%, 31%, and 60%, respectively, whereas 63% of CAS procedures involved a clinically significant hemodynamic instability. Experience of a recent stroke was found to be an independent risk factor for the development of clinically significant hemodynamic instability (odds ratio, 5.24; p=0.02). Patients with clinically significant hemodynamic instability were also more likely to develop a perioperative stroke than those without it (8% versus 1%, p=0.03). The authors concluded that hemodynamic instability represents a common occurrence following CAS and can be associated with increased risk of perioperative stroke.34)

Technical Predictors of Perioperative Stroke/Death after CAS

Stent type (open versus closed cell)

The type of stent or stent design used and its effect on perioperative stroke rates after CAS has been controversial. Stents are generally classified into closed or open cell depending on the density of the struts. In general, if a free-cell area is >7 mm2, the stent is considered an open cell. A multicenter study involving 3,179 patients concluded that a free-cell area of >7.5 mm2 was associated with a high perioperative 30-day stroke rate. The 30-day stroke rate was 3.4% in patients with open-cell stents with a free-cell area of >7.5 mm2 compared with 1.3% in other patients, suggesting that closed-cell stents are associated with low perioperative stroke rates.36) However, in a recent randomized controlled trial of 40 CAS procedures, Timaran et al.37) compared CAS procedures performed using open-cell with those closed-cell stents and found no statistical difference in the embolic event rate, as revealed using transcranial Doppler (TCD) and diffusion-weighted MRI. Similarly, the Society of Vascular Surgery Registry reported no significant difference in perioperative stroke rates, regardless of the stent design.38) Theiss et al.12) also showed that there is no significant difference in perioperative stroke regardless of the stent type.

Stent length/multiple stents

Gray et al. analyzed the CAPTURE trial data and demonstrated that the use of multiple carotid stents was associated with a higher 30-day stroke rate of 9.7%, compared with a stroke rate of 4.5% in patients that required only one stent placement.2) It is widely assumed that the use of multiple stents is a surrogate marker of lesion length, which is associated with a high rate of ischemic events. However, in a recent study, AbuRahma et al.27) demonstrated that there is no significant difference in perioperative stroke and MAE rates in terms of the applied stent type or design, number of stents used, stent diameter, and stent length. Notably, only 24 of 409 patients had more than one stent in the abovementioned study.

PTA prior to embolic protection device (EPD) insertion, pre-stenting PTA, and/or post-PTA stenting

Few number of studies have determined that microembolization can occur during all phases of CAS, starting with the wiring, the insertion of the EPD, pre-stenting PTA, and post-stenting PTA, as demonstrated by TCD. It has also been suggested that the most showering occurs during the post-stenting PTA, which can be due to PTA fractures of the plaque that facilitates the pushing of some embolic debris through the stent mesh.2,35)

The CAPTURE study2) showed that pre-PTA without EPD insertion was associated with a high perioperative stroke rate; the perioperative stroke rate was 15.4% in patients with pre-PTA without EPD insertion and 4.3% in patients with stroke without pre-PTA. Theiss et al. showed a higher periprocedural stroke rate of 4.1% in patients with pre-PTA versus 3% in patients without it based on the pro-CAS registry data.12) Recently, Obeid et al.35) analyzed patients who underwent CAS between 2005 and 2014 from the Vascular Quality Initiative Database that included a total of 3,772 patients. They reported that post-stent PTA was associated with a 2.4-fold higher periprocedural stroke/death rate of 3% than pre-stent PTA. Post-stenting PTA is thought to lead to increased embolic showering and hemodynamic depression, which may persist into the postoperative period.

AbuRahma et al.27) reported a perioperative stroke rate of 9.1% in patients with PTA before EPD insertion. In contrast, the stroke rate was found to be 1.8% in patients without PTA before EPD insertion. Furthermore, 2.6% of patients with post-stenting PTA had a stroke, whereas no patient without PTA had a stroke. The MAE rate was 5.6% in patients with post-stenting PTA compared with 0% in patients without PTA (p=0.0536). A multivariate analysis also showed that PTA prior to EPD insertion had an odds ratio of 6.15 for stroke (p=0.062). These findings reiterate the fact that PTA before filter insertion or before stenting or both and after stenting is associated with a significant adverse event rate.

Use of embolic protection devices

Cerebral EPDs are used to reduce embolic events during CAS, and they have been successful in reducing the number of embolic particles detected by TCD39,40) and decreasing perioperative stroke rates (1.7% with EPD versus 4.1% without EPD). The EVA-3S trial showed that the use of EPDs is associated with a lower perioperative stroke rate.26) Nonetheless, EPDs cannot eliminate the emboli detected by TCD.41,42) Indeed, EPD use can be associated with technical difficulties in traversing the lesion, which may lead to an additional risk of embolization during the manipulation of the device. The International Carotid Stenting Study (ICSS) trial showed that CAS using EPD was associated with a significantly higher number of new diffusion weighted-MRI lesions than CAS without EPD at 1 month (73% versus 34%, p=0.019).43) A further randomized trial comparing CAS with (n=44) and without EPDs (n=35) found no significant difference in 30-day stroke rates (11.1% versus 11.1%).44) However, this trial observed a trend toward a higher number of lesions, as detected by diffuse-weighted imaging, in patients undergoing CAS with EPDs (72%) than in those undergoing CAS without EPD (44%) at 1 month.44)

Residual stenosis

Residual stenosis is generally defined as ≥30% stenosis. In a pooled data analysis of four major Cordis-sponsored studies (CASES, SAPPHIRE, CNC, and ADVANCE) involving 2,104 patients, Aronow et al.4) found that the severity of >30% final residual stenosis was a predictor of perioperative strokes in patients undergoing CAS. However, it was not clear from their analysis whether the higher risk was due to greater residual stenosis or a reflection of high-risk patients in whom lesser residual stenosis was not attainable. However, Gray et al.2) identified <10% residual stenosis as a univariable predictor of a poor outcome after CAS.

Perioperative medication predictors

The use of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors,45–48) but not of protamine and vasopressors, has been associated with poor outcomes after CAS in previous studies.

Qureshi et al. reported a lower periprocedural ischemic stroke rate of 3% in patients treated with platelet glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors compared with a rate of 12% in those who underwent CAS without such inhibitors; however, this benefit was offset by high rates of intracranial hemorrhage.47) A comparative study showed that the use of EPDs alone had a lower perioperative stroke rate (0%) than the use of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa alone (5.1%).48) Thus, a selection bias in patients receiving platelet glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors should be accounted for as they are considered as being at high risk of ischemic events during CAS.

A pro-CAS trial also found that high doses of IV heparin (>5,000 IU) were associated with a high periprocedural stroke rate (4.5% high dose of IV heparin versus 2.9% lower doses of IV heparin, p=0.0019).12) This higher rate may be related to more complex procedures that necessitate higher doses of anticoagulation or medication. Notably, Gröschel et al. found a lower 30-day stroke/MI/death rate of 4% in CAS patients using statins compared with a rate of 15% in patients not using statins.49)

CAS volume/provider experience

A pooled data analysis of four major Cordis-sponsored studies4) and the CAPTURE2) trial showed a significant difference in 30-day stroke and death rates associated with the center experience. Experienced centers were defined as those who had enrolled >20 patients according to the pooled data analysis of the Cordis-sponsored studies4) and >25 CAS-treated patients in the CAPTURE trial.2) The CAPTURE 2 trial showed that high-volume centers (where >70 CAS procedures are performed annually) had lower 30-day stroke/death rates (<3%) than low-volume centers, which had a 30-day stroke rate of >3%.50) Pro-CAS data also highlighted that experienced centers, here defined as those where >50 CAS procedures are performed annually, had low periprocedural stroke rates.12) An analysis of the Medicare data also revealed that 30-day death rates were as low as 1.4% in patients undergoing CAS at high-volume centers (here defined as centers where >24 CAS procedures are performed annually) compared with 2.5% in low-volume centers.51)

Setacci et al. reported that operator experience of <50 CAS procedures was associated with a high 30-day stroke rate,28) whereas Verzini et al. further demonstrated that peri- and post-procedural stroke rates decreased with increasing number of CAS procedures performed by the operator, stabilizing at <2% when 195 CAS procedures were performed by a single operator.52) The Medicare data analysis also revealed that 30-day stroke rates were low after operators had performed 12 CAS procedures.53) A study showed that stroke and mortality rates did not differ when CAS was performed by vascular surgeons and non-vascular surgeons (interventional cardiologists and interventional neuroradiologists).53) In contrast, the recently published data from the lead-in phase of the CREST revealed that interventional cardiologists and neuroradiologists were associated with low periprocedural stroke rates of 3.9% and 1.6%, respectively, whereas vascular surgeons (7.7%) and interventional radiologists were associated with high periprocedural stroke rates of 7.7% and 6.6%, respectively.54)

Timaran et al.55) reported differential outcomes of CAS and CEA performed exclusively by vascular surgeons in the CREST. When procedures were performed exclusively by vascular surgeons, the primary endpoint did not differ between CAS and CEA at 4-year follow-up. Notably, the stroke rates for CAS and CEA were 6.2% and 5.6%, respectively (hazard ratio, 1.30; p=0.41). The periprocedural stroke and death rates were higher after CAS than after CEA for symptomatic patients in this subgroup (6.1% versus 1.3%; p=0.01). Similarly, asymptomatic patients who underwent CAS also had slightly higher stroke and death rates than those who underwent CEA (2.6% versus 1.1%; p=0.20), although the difference between the rates was not statistically significant. Outcomes for the periprocedural primary endpoint after CAS procedures performed by vascular surgeons were comparable to those after CAS performed by all other interventionists (hazard ratio, 0.99) after adjusting for age, sex, and symptoms. These results suggested that appropriately trained vascular surgeons safely offer both CEA and CAS for the prevention of stroke. Notably, in the CREST, the stroke and death rates after CEA performed by vascular surgeons were remarkably low, particularly in symptomatic patients.55)

AbuRahma et al.56) analyzed the correlation of CAS outcomes with operator’s specialty and volume. In their study, they analyzed prospectively collected data from 414 CAS procedures performed at their institution over a 10-year period. MAEs (30-day stroke, myocardial infarction, and death) were compared according to operator’s specialty (vascular surgeons, interventional cardiologists, interventional radiologists, or interventional vascular medicine) and volume (≥5 CAS per year versus <5 CAS per year). MAE rates were not significantly different among various specialties. Highest event rates were associated with interventional radiologists (7.1%), followed by those with interventional vascular medicine (6.7%), vascular surgeons (6.3%) and interventional cardiologists (3.1%) (p=0.3121). When physicians with <5 CAS per year were excluded, the MAE rates were 6.7% for interventional vascular medicine, 4.7% for vascular surgeons, and 3.1% for interventional cardiologists (p=0.5633). In contrast, when vascular surgeons were compared with non-vascular surgeons and physicians with <5 CAS per year were excluded, the MAE rates were 4.7% for vascular surgeons compared with 3.6% for non-vascular surgeons (p=0.5958). The MAE rates associated with low-volume operators, regardless of their specialty, were 9.5% compared with 4% associated with high-volume operators (p=0.1002). AbuRahma et al. concluded that perioperative MAE rates for CAS were similar between various operators, regardless of their specialty, particularly for vascular surgeons with volume similar as that of non-vascular surgeons. Clearly, low-volume operators were associated with high MAE rates.56)

Other Predictors of CAS Outcomes

Hawkins et al.57) reported pre-procedural risk quantification for carotid stenting using the CAS score. The authors developed and internally validated a risk score to predict in-hospital stroke or death after CAS. Patients undergoing CAS without acute evolving stroke from April 2005 to June 2011 were included as part of the National Cardiovascular Data Registry (NCDR) and Carotid Artery Revascularization and Endarterectomy Registry. Stroke/death was modeled using a logistic regression with a total of 35 candidate variables. In total, 271 primary endpoint events were noted during 11,122 procedures (2.4%). Among the candidate variables were impending major surgery, symptomatic lesion, age, previous stroke, atrial fibrillation, and absence of previous ipsilateral CEA. The inclusion of available angiographic parameters did not improve model performance. The authors concluded that the NCDR score, comprising six clinical parameters, could satisfactorily predict in-hospital stroke/death after CAS. Such models may be useful to clinicians in evaluating optimal management and improve patient selection for CAS.57)

Our clinical experience

We conducted a retrospective analysis of prospectively collected data from 409 of 456 patients who underwent CAS at our center. A logistic regression analysis was used to determine the effects of anatomical and technical factors on perioperative stroke, death, and myocardial infarction (MAEs). The stroke rate was 2.2%, and the MAE rate was 4.7%. The stroke rate among asymptomatic patients was 0.46%. The MAE rate in patients with TIA was 7%, whereas the stroke rate in patients with other indications was 3.2% (p=0.077). If heavily calcified lesions were present, the stroke rate was 6.3%, whereas in the case of mildly calcified/non-calcified lesions, the stroke rate was as low as 1.2% (p=0.046). No significant difference was observed in stroke and MAE rates in relation to other anatomical features. We found a stroke rate of 9.1% in patients with PTA before EPD insertion and of 1.8% in patients without PTA (p=0.07). The stroke rate in patients with post-stenting PTA was 2.6%, whereas that in patients without post-stenting PTA was 0%. The MAE rate in patients with post-stenting PTA was 5.6%, whereas that in patients without post-stenting PTA was 0% (p=0.0536). Furthermore, the MAE rate in patients with the ACCUNET EPD was 1.9%, whereas that in patients with other types of EPD was 6.7% (p=0.029). The difference between stroke and MAE rates for other technical features was not significant. A regression analysis for stroke as outcome showed that the odds ratio for asymptomatic indications was 0.1 (p=0.031), for TIA indications was 13.7 (p=0.014), for PTA performed before EPD insertion was 6.1 (p=0.0303), for PTA performed before stenting was 1.7 (p=0.4413), and for heavily calcified lesions was 5.4 (p=0.0315). Another multivariate analysis showed that patients with TIA had an odds ratio of 11.05 for stroke (p=0.029). In addition, patients with PTA performed before EPD insertion had an odds ratio of 6.15 for stroke (p=0.062). If heavily calcified lesions were present, an odds ratio of 4.25 for stroke (p=0.087) was obtained. The MAE odds ratio for ACCUNET versus other EPDs was 0.27 (p=0.0389) (Tables 1–3).

Table 1 Anatomical predictors of perioperative stroke.

| Predictor | Stroke, No. (%) | p value |

|---|---|---|

| Lesion location | ||

| All carotid lesions | 0.7371 | |

| Right side* | 3/179 (1.7) | |

| Left side* | 6/230 (2.6) | |

| ICA lesions only | 0.4584 | |

| Right side | 2/137 (1.5) | |

| Left side | 5/161 (3.1) | |

| Preoperative stenosis | 0.4626 | |

| 50%–69% | 1/27 (3.7) | |

| 70%–99% | 8/382 (2.1) | |

| CAS for post-CEA | 1/147 (0.7) | |

| Primary CAS | 8/261 (3.1) | 0.1656 |

| Lesion length | ||

| <15 mm | 4/175 (2.3) | 1 |

| ≥15 mm | 5/228 (2.2) | |

| <20 mm | 6/230 (2.6) | 0.7380 |

| ≥20 mm | 3/173 (1.7) | |

| Lesion calcification | 0.46 | |

| Heavy | 3/48 (6.3) | |

| None to mild | 4/332 (1.2) | |

| Aortic arch type | 1 | |

| Type I | 4/179 (2.2) | |

| Type II | 3/170 (1.8) | |

| Type III | 1/32 (3.1) | |

| Unknown | 1/28 (3.6) |

* Includes all common carotid artery, carotid bifurcation, and ICA lesions.

Table 2 Technical predictors of perioperative stroke.

| Predictor | Stroke No. (%) | p value |

|---|---|---|

| Type of EPD: | ||

| Accunet | 3/158 (1.9)*** | 0.745 |

| Emboshield NAV6 | 4/198 (2) | |

| Others (including Emboshield) | 5/240 (2) | |

| Type of stent: | ||

| ACCULINK | 4/209 (1.9) | 0.7449 |

| Xact | 4/155 (2.6) | |

| Others | 1/42 (2.4) | |

| No. of stents: | ||

| 1 | 9/383 (2.4) | 1 |

| >1 | 0/24 | |

| Stent length: | ||

| ≤30 mm | 3/119 (2.5)*** | 0.426 |

| >30 mm | 4/284 (1.4) | |

| PTA prior to EPD insertion: | ||

| Yes | 2/22 (9.1) | 0.0791 |

| No | 7/387 (1.8) | |

| PTA prior to stenting: | ||

| Yes | 6/244 (2.5) | 0.7451 |

| No | 3/165 (1.8) | |

| PTA post-stenting: | ||

| Yes | 9/341 (2.6) | 0.3666 |

| No | 0/68 |

Table 3 Logistic regression analysis.

| Multivariate: early stroke variable | OR | 95% CI | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| TIA indication | 11.05 | (1.28–95.47) | 0.029 |

| Pre-PTA performed prior to EPD* | 6.15 | (0.91–41.44) | 0.062 |

| Target site calcification: heavy | 4.25 | (0.81–22.32) | 0.0871 |

| Multivariate: early MI/stroke/death variable | OR | 95% LCL | p value |

| EPD*-ACCUNET vs. other | 0.27 | (0.08–0.94) | 0.0389 |

* EPD (Embolic Protection Device)

We concluded that calcific lesions and PTA before EPD insertion or after stenting were associated with higher stroke or MAE rates. There was no relationship between other anatomical/technical variables and CAS outcomes.27)

Acknowledgments

The author gratefully acknowledges Mona Lett for her editorial assistance in the preparation of this manuscript.

Disclosure Statement

I have no conflicts of interest to declare.

This is a review article based on the invited lecture of the 45th Annual Meeting of Japanese Society for Vascular Surgery.

References

- 1).Yadav JS, Wholey MH, Kuntz RE, et al. Protected carotid artery stenting versus endarterectomy in high-risk patients. N Engl J Med 2004; 351: 1493-501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2).Gray WA, Yadav JS, Verta P, et al. The CAPTURE registry: predictors of outcomes in carotid artery stenting with embolic protection for high surgical risk patients in the early post-approval setting. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv 2007; 70: 1025-33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3).Khan M, Qureshi A. Factors associated with increased rates of post-procedural stroke or death following carotid artery stent placement: a systematic review. J Vasc Interv Neurol 2014; 7: 11-20. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4).Aronow HD, Gray WA, Ramee SR, et al. Predictors of neurological events associated with carotid artery stenting in high-surgical-risk patients. Circ Cardiovasc Interv 2010; 3: 577-84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5).Chaturvedi S, Matsumura JS, Gray W, et al. Carotid artery stenting in octogenarians: periprocedural stroke risk predictor analysis from the multicenter Carotid ACCULINK/ACCUNET Post Approval Trial to Uncover Rare Events (CAPTURE 2) clinical trial. Stroke 2010; 41: 757-64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6).Stingele R, Berger J, Alfke K, et al. Clinical and angiographic risk factors for stroke and death within 30 days after carotid endarterectomy and stent-protected angioplasty: a subanalysis of the SPACE study. Lancet Neurol 2008; 7: 216-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7).Brott TG, Hobson RW, Howard G, et al. Stenting versus endarterectomy for treatment of carotid artery stenosis. N Engl J Med 2010; 363: 11-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8).Mathur A, Roubin GS, Iyer SS, et al. Predictors of stroke complicating carotid artery stenting. Circulation 1998; 97: 1239-45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9).Russjan A, Goebell E, Havemeister S, et al. Predictors of periprocedural brain lesions associated with carotid stenting. Cerebrovasc Dis 2012; 33: 30-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10).Kastrup A, Groschel K, Schulz JB, et al. Clinical predictors of transient ischemic attack, stroke, or death within 30 days of carotid angioplasty and stenting. Stroke 2005; 36: 787-91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11).Kawabata Y, Sakai N, Nagata I, et al. Clinical predictors of transient ischemic attack, stroke, or death within 30 days of carotid artery stent placement with distal balloon protection. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2009; 20: 9-16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12).Theiss W, Hermanek P, Mathias K, et al. Predictors of death and stroke after carotid angioplasty and stenting: a subgroup analysis of the Pro-CAS data. Stroke 2008; 39: 2325-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13).Wang FW, Esterbrooks D, Kuo YF, et al. Outcomes after carotid artery stenting and endarterectomy in the Medicare population. Stroke 2011; 42: 2019-25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14).Howard VJ, Lutsep HL, Mackey A, et al. Influence of sex on outcomes of stenting versus endarterectomy: a subgroup analysis of the Carotid Revascularization Endarterectomy versus Stenting Trial (CREST). Lancet Neurol 2011; 10: 530-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15).Bond R, Rerkasem K, Cuffe R, et al. A systematic review of the associations between age and sex and the operative risks of carotid endarterectomy. Cerebrovasc Dis 2005; 20: 69-77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16).Dua A, Romanelli BS, Upchurch GR Jr, et al. Predictors of poor outcome after carotid intervention. J Vasc Surg 2016; 64: 663-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17).Rockman CB, Garg K, Jacobowitz GR, et al. Outcome of carotid artery interventions among female patients, 2004 to 2005. J Vasc Surg 2011; 53: 1457-64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18).Qureshi AI, Janardhan V, Memon MZ, et al. Initial experience in establishing an academic neuroendovascular service: program building, procedural types and outcomes. J Neuroimaging 2009; 19: 72-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19).Qureshi AI, Luft AR, Janardhan V, et al. Identification of patients at risk for periprocedural neurological deficits associated with carotid angioplasty and stenting. Stroke 2000; 31: 376-82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20).Mas JL, Trinquart L, Leys D, et al. Endarterectomy Versus Angioplasty in Patients with Symptomatic Severe Carotid Stenosis (EVA-3S) trial: results up to 4 years from a randomised, multicenter trial. Lancet Neurol 2008; 7: 885-92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21).Alberts MJ. Results of a multicenter prospective randomized trial of carotid stenting vs carotid endarterectomy. Stroke 2001; 32: 325. [Google Scholar]

- 22).Steinbauer MG, Pfister K, Greindl M, et al. Alert for increased long-term follow-up after carotid artery stenting: results of a prospective, randomized, single-center trial of carotid artery stenting vs carotid endarterectomy. J Vasc Surg 2008; 48: 93-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23).Jackson BM, English SJ, Fairman RM, et al. Carotid artery stenting: identification of risk factors for poor outcomes. J Vasc Surg 2008; 48: 74-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24).Bergeron P, Roux M, Khanoyan P, et al. Long-term results of carotid stenting are competitive with surgery. J Vasc Surg 2005; 41: 213-21; discussion, 221-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25).AbuRahma AF, Alhalbouni S, Abu-Halimah S, et al. Impact of chronic renal insufficiency on the early and late clinical outcomes of carotid artery stenting using serum creatinine vs glomerular filtration rate. J Am Coll Surg 2014; 218: 797-805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26).Naggara O, Touze E, Beyssen B, et al. Anatomical and technical factors associated with stroke or death during carotid angioplasty and stenting: results from the Endarterectomy Versus Angioplasty in Patients with Symptomatic Severe Carotid Stenosis (EVA-3S) trial and systematic review. Stroke 2011; 42: 380-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27).AbuRahma AF, DerDerian T, Hariri N, et al. Anatomical and technical predictors of perioperative clinical outcomes after carotid artery stenting. J Vasc Surg 2017; 66: 423-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28).Setacci C, Chisci E, Setacci F, et al. Siena carotid artery stenting score: a risk modeling study for individual patients. Stroke 2010; 41: 1259-65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29).Sayeed S, Stanziale SF, Wholey MH, et al. Angiographic lesion characteristics can predict adverse outcomes after carotid artery stenting. J Vasc Surg 2008; 47: 81-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30).Lam RC, Lin SC, DeRubertis B, et al. The impact of increasing age on anatomic factors affecting carotid angioplasty and stenting. J Vasc Surg 2007; 45: 875-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31).Faggioli G, Ferri M, Gargiulo M, et al. Measurement and impact of proximal and distal tortuosity in carotid stenting procedures. J Vasc Surg 2007; 46: 1119-24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32).Moore WS, Popma JJ, Roubin GS, et al. Carotid angiographic characteristics in the CREST trial were major contributors to periprocedural stroke and death differences between carotid artery stenting and carotid endarterectomy. J Vasc Surg 2016; 63: 851-8.e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33).Silvestro A, Civelli P, Laffranchini G, et al. Influence of anatomical factors on the feasibility and safety of carotid stenting in a series of 154 consecutive procedures. J Cardiovasc Med (Hagerstown) 2008; 9: 137-41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34).Ullery BW, Nathan DP, Shang EK, et al. Incidence, predictors, and outcomes of hemodynamic instability following carotid angioplasty and stenting. J Vasc Surg 2013; 58: 917-25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35).Obeid T, Arnaoutakis DJ, Arhuidese I, et al. Post-stent ballooning is associated with increased periprocedural stroke and death rate in carotid artery stenting. J Vasc Surg 2015; 62: 616-23.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36).Bosiers M, de Donato G, Deloose K, et al. Does free cell area influence the outcome in carotid artery stenting? Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 2007; 33: 135-41; discussion, 142-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37).Timaran CH, Rosero EB, Higuera A, et al. Randomized clinical trial of open-cell vs closed-cell stents for carotid stenting and effects of stent design on cerebral embolization. J Vasc Surg 2011; 54: 1310-6.e1; discussion, 1316.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38).Jim J, Rubin BG, Landis GS, et al. Society for Vascular Surgery Vascular Registry evaluation of stent cell design on carotid artery stenting outcomes. J Vasc Surg 2011; 54: 71-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39).Vos JA, van den Berg JC, Ernst SM, et al. Carotid angioplasty and stent placement: comparison of transcranial Doppler US data and clinical outcome with and without filtering cerebral protection devices in 509 patients. Radiology 2005; 234: 493-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40).Ohki T, Veith FJ. Carotid stenting with and without protection devices: should protection be used in all patients? Semin Vasc Surg 2000; 13: 144-52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41).Maleux G, Demaerel P, Verbeken E, et al. Cerebral ischemia after filter-protected carotid artery stenting is common and cannot be predicted by the presence of substantial amount of debris captured by the filter device. Am J Neuroradiol 2006; 27: 1830-3. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42).Tübler T, Schlüter M, Dirsch O, et al. Balloon-protected carotid artery stenting: relationship of periprocedural neurological complications with the size of particulate debris. Circulation 2001; 104: 2791-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43).Bonati LH, Jongen LM, Haller S, et al. New ischemic brain lesions on MRI after stenting or endarterectomy for symptomatic carotid stenosis: a substudy of the International Carotid Stenting Study (ICSS). Lancet Neurol 2010; 9: 353-62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44).Barbato JE, Dillavou E, Horowitz MB, et al. A randomized trial of carotid artery stenting with and without cerebral protection. J Vasc Surg 2008; 47: 760-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45).Zahn R, Ischinger T, Hochadel M, et al. Glycoprotein IIb/IIIa antagonists during carotid artery stenting: results from the carotid artery stenting (CAS) registry of the Arbeitsgemeinschaft Leitende Kardiologische Krankenhausärzte (ALKK). Clin Res Cardiol 2007; 96: 730-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46).Wholey MH, Wholey MH, Eles G, et al. Evaluation of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors in carotid angioplasty and stenting. J Endovasc Ther 2003; 10: 33-41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47).Qureshi AI, Suri MF, Ali Z, et al. Carotid angioplasty and stent placement: a prospective analysis of perioperative complications and impact of intravenously administered abciximab. Neurosurgey 2002; 50: 466-73; discussion, 473-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48).Chan AW, Yadav JS, Bhatt DL, et al. Comparison of the safety and efficacy of emboli prevention devices versus platelet glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibition during carotid stenting. Am J Cardiol 2005; 95: 791-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49).Gröschel K, Ernemann U, Schulz JB, et al. Statin therapy at carotid angioplasty and stent placement: effect on procedure-related stroke, myocardial infarction, and death. Radiology 2006; 240: 145-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50).Gray WA, Rosenfield KA, Jaff MR, et al. Influence of site and operator characteristics on carotid artery stent outcomes: analysis of the CAPTURE 2 (Carotid ACCULINK/ACCUNET Post Approval Trial to Uncover Rare Events) clinical study. JACC Cardiovasc Interv 2011; 4: 235-46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51).Nallamothu BK, Gurm HS, Ting HH, et al. Operator experience and carotid stenting outcomes in Medicare beneficiaries. JAMA 2011; 306: 1338-43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52).Verzini F, Cao P, De Rango P, et al. Appropriateness of learning curve for carotid artery stenting: an analysis of periprocedural complications. J Vasc Surg 2006; 44: 1205-11; discussion, 1211-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53).Steppacher R, Csikesz N, Eslami M, et al. An analysis of carotid artery stenting procedures performed in New York and Florida (2005–2006): procedure indication, stroke rate, and mortality rate are equivalent for vascular surgeons and non-vascular surgeons. J Vasc Surg 2009; 49: 1379-85; discussion, 1385-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54).Hopkins LN, Roubin GS, Chakhtoura EY, et al. The Carotid Revascularization Endarterectomy versus Stenting Trial: credentialing or interventionalists and final results of lead-in phase. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis 2010; 19: 153-62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55).Timaran CH, Mantese VA, Malas M, et al. Differential outcomes of carotid stenting and endarterectomy performed exclusively by vascular surgeons in the Carotid Revascularization Endarterectomy versus Stenting Trial (CREST). J Vasc Surg 2013; 57: 303-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56).AbuRahma AF, Campbell JE, Hariri N, et al. Clinical outcome of carotid artery stenting according to provider specialty and volume. Ann Vasc Surg 2017; 44: 361-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57).Hawkins BM, Kennedy KF, Giri J, et al. Pre-procedural risk quantification for carotid stenting using the CAS score: a report from the NCDR CARE Registry. J Am Coll Cardiol 2012; 60: 1617-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]