Abstract

Introduction:

Primary hepatic mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma is extremely rare and we herein report a case of a patient suffering from primary hepatic MALT lymphoma with concomitant hepatitis B virus infection.

Diagnostic modalities and outcome:

Double masses were found in a 59-year-old Chinese female patient. We reported the laboratory results, computed tomography (CT) and fluorine-18-fluorodeoxyglucose (18F-FDG) positron emission tomography (PET)/CT images among other findings. As far as we know, only 9 cases have been reported till now using 18F-FDG PET/CT imaging. Our patient's lesions were found to conform to standard uptake values of FDG.

Conclusion:

It indicates that hepatic MALT lymphoma can be studied with 18F-FDG PET/CT like other 18F-FDG-avid lymphomas. It was also noted that delayed-time-point FDG PET imaging may further improve the detection of the MALT lymphoma in liver. Although the patient in this case refused further treatment, potential management options, including rituximab, which is also discussed in this review.

Keywords: 18F-FDG PET/CT, delayed-time-point, MALT, primary hepatic lymphoma

1. Introduction

Primary lymphoma of the liver refers to lesions confined only to the liver, whereas spleen, lymph nodes, bone marrow, or other lymphoid tissues are not involved. Although the liver is commonly affected secondarily as an extranodal involvement in non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL), it is seldom the primary site of NHL, whereas primary hepatic mucosa-associated marginal zone B-cell lymphoma is even rarer. So far, the prognostic value of 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) PET/CT in the workup of primary hepatic mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma has rarely been described. In this article, we retrospectively report the clinical characteristics, laboratory results, image findings plus 18F-FDG positron emission tomography/computed tomography (PET/CT) results of 1 case of primary hepatic MALT lymphoma and discuss about the related literature reviews.

2. Case report

2.1. Clinical characteristic

2.1.1. Medical history

Our patient, a 59-year-old female, with a history of hepatitis B infection for >20 years, has never been on any antineoplastic therapy because of her difficult financial situation. She was put on anti-hepatitis B treatment since from January 2015. The patient's only complaint was that of long-term abdominal discomfort with fatigue. No cough or expectoration, no abdominal pain, no diarrhea, no rash or joint pain was reported. Patient denied any history of hypertension, diabetes, tuberculosis, tobacco smoking, or alcohol abuse. She underwent menopause at the age of 52 years. She was diagnosed primary hepatic MALT lymphoma since 2015, but she refused to receive further treatment.

2.1.2. Physical examination

General condition of the patient was good. No icterus was apparent and superficial lymph nodes were not palpable. Cardiovascular and respiratory examinations were normal. Liver and spleen were not palpable per abdomen. Abdomen was non-tender and bowel sounds were fine.

2.2. Laboratory results

Her blood investigations (Table 1) were within the normal ranges except for an elevated gamma glutamyl peptidase (γ-GT) of 58 U/L, decreased white blood cell (WBC) of 3.7 × 109 cells/L, and elevated monocyte and eosinophil percentage of 10.6% and 6.1%. Urine analysis, stool examination, blood tumor biomarkers, autoimmune antibody, and other routine biochemical tests were all within normal limits. Anti-hepatitis C antibodies were positive and hepatitis B surface antigen was negative.

Table 1.

Laboratory data on admission.

2.3. Imaging examination

2.3.1. Chest and abdominal CT

Chest and abdominal CT showed multiple low-density lesions in liver without obvious boundaries or intensifications. Mediastinal and retroperitoneal lymph nodes were not seen.

2.3.2. Whole-body 18F-FDG PET/CT

PET/CT was performed for further elevation which revealed a low-density lesion of about 2.9cm × 2.0 cm in the medial segment of left liver with unclear borders. PET/CT fusion images showed a slightly increased uptake of standard uptake value (SUV) (SUVmax, 4.09). On delayed FDG PET/CT scan (performed 2 hours after injection of tracer), the maximum value was about 4.2 (Fig. 1). At the right hepatic lobe margin, a low-density lesion with diameter of about 1.15 cm was noticed. PET/CT fusion images showed that the FDG uptake was increased slightly (SUVmax, 3.42). The maximum value was about 3.51 in delayed FDG PET/CT scan (Fig. 2). For the rest of the structures, 18F-FDG PET/CT imaging demonstrated no obvious changes: no enlargement of lymph nodes or spleen, no abnormal uptake of FDG of bone marrow and other areas.

Figure 1.

Cross-sectional positron emission tomography/computed tomography imaging 1.

Figure 2.

Cross-sectional positron emission tomography/computed tomography imaging 2.

2.4. Pathology

The patient underwent a percutaneous liver biopsy on January 2015, and the histopathological analysis revealed a MALT lymphoma. Analysis further confirmed an abnormal proliferation of B lymphocytes in liver tissue. The immunohistochemical (IH) staining was positive for BcL-2, CD3, CD5, CD2, CD4, CD79a, CD43, CD20, CD21, CD2 (positive in follicular dendritic cell), and part of CD7 and CD8. Conversely, Bcl-6, CD10, and CyclinD1 were negative. Ki-67 index was about 10%. The Shanghai Cancer Hospital, after evaluation of the liver biopsy specimen of our patient, agreed and confirmed the diagnosis of a mucosa associated lymphoid tissue extranodal marginal zone lymphoma.

3. Discussion

Lymphomas of MALT are low-grade extranodal marginal zone B-cell lymphoma[1] (accounting for approximately 8% of all NHL).[2,3] MALT lymphomas originate from cells which can differentiate into edged monocyte-like B cells and cells near the plasma germinal center, which is one of the most common extranodal low-grade malignant lymphoma. They commonly occur in the gastrointestinal tract such as stomach, and nongastrointestinal sites like salivary glands, thyroid, and lungs.[4,5] Liver, however, is a rare site of primary lymphoid malignancy, accounting for <1% of extranodal NHL lymphomas.[6] Primary hepatic lymphoma refers to localized lesions in the liver, without spleen, lymph node, bone marrow or other systemic lymphoid tissue involvement evidence. Most of these reported pathological types are diffuse large B cell lymphomas, whereas primary hepatic marginal zone B cell lymphoma of MALT lymphomas is extremely rare, accounting for only 2% to 4% of the primary hepatic lymphomas.[7–11]

The etiology of liver MALT lymphoma is still indistinct. Chronic inflammation owing to conditions like infections or autoimmune diseases has often been linked to most extranodal MALT lymphomas. Nagata et al[12,13] described 51 hepatic MALT lymphoma cases. They stated that only 25% patients were not associated with any disease condition. Twenty-one percent of those liver MALT lymphomas were associated with carcinomas, 20% were related to viral and drug related-hepatitis, and the rest were biliary cirrhosis, liver cirrhosis, ascariasis, gastric MALT lymphoma, and rheumatoid arthritis and so on. [11,14] Doi et al[15–19] reported 46 such cases, mainly elderly patients (mean age 61.4 years). The ratio of male and female was 0.9:1.0. Most patients were diagnosed either by liver surgery, liver imaging, or incidentally through examinations for other diseases. Liver diseases were found in 16 patients, including primary biliary cirrhosis and liver infections (such as hepatitis B virus, hepatitis C virus, and ascariasis). Some scholars believe that[8,15] chronic inflammation of the liver is one of the most significant factors predisposing to MALT, as well as hepatitis C virus infection. Along these lines, we have presented a retrospective report of a female patient with primary hepatic MALT lymphoma, with a history of hepatitis B infection for >20 years. No other abnormal findings indicating other cause of chronic liver disease were detected.

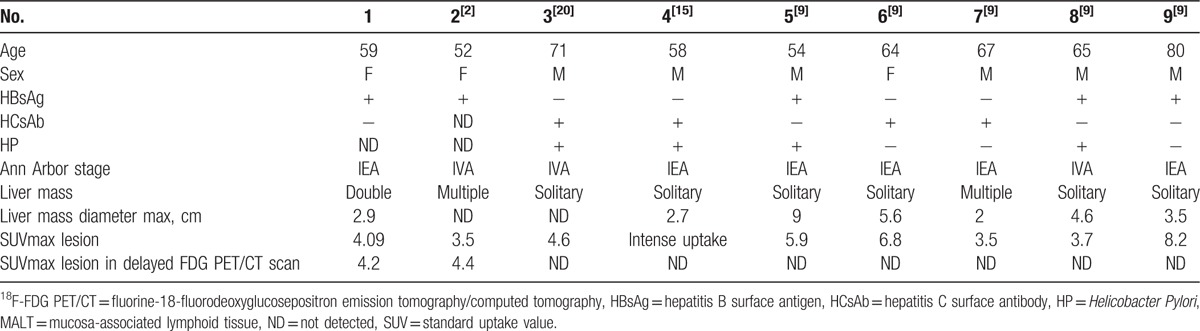

Precise staging of MALT lymphoma by radiologic studies is essential for optimizing its treatment. As the imaging characteristics of hepatic MALT lymphoma have rarely been studied, the significance of 18F-FDG PET/CT in evaluating MALT lymphomas is still controversial and unclear. The potential metabolic behavior and the utility of 18F-FDG PET/CT in primary hepatic lymphoma still remain unknown. We have, in the past, reviewed 9 cases of primary hepatic MALT patients (Table 2)[2,9,15,20] with solitary lesions, and double or multiple lesions (66.7% [6/9] and 33.3% [3/9], respectively). These figures correspond to the report of Doi et al[15–19] on liver MALT lymphoma with solitary lesions being more common (76.2% or 32/42) than double (9.5% or 4/42) and multiple (14.3% or 6/42) ones.[15] Primary hepatic MALT was easily misdiagnosed as primary liver cancer; hence, differential diagnosis of imaging is particularly important. Hepatocellular carcinomas are recognized on ultrasound by hyperechoic lesions, whereas CT scan shows lesions which are significantly enhanced in the arterial phase and of equal or low density in delayed portal venous phase. In contrast, primary hepatic MALT lymphomas are displayed as hypoechoic lesions under ultrasound, and show low attenuation with or without enhancement in CT scan.

Table 2.

Summary of clinical data of 9 patients with hepatic MALT lymphoma who underwent 18F-FDG PET/CT.

Doi et al[15] reported the first case of primary liver MALT investigated by 18F-FDG PET/CT scan, which showed a high metabolic liver disease sign. This yielded additional data related to the lesion site and stage of the disease. Perry et al[19] as well reported that 18F-FDG PET/CT imaging for primary liver MALT lymphoma demonstrated high FDG uptake by the lesions. It is noteworthy that MALT lymphoma shows lower FDG uptake comparing to other aggressive lymphomas such as diffuse large B cell lymphoma.[21,22]

The 18F-FDG PET/CT imaging is particularly helpful in distinguishing the initial stages of extranodal MALT lymphoma. In our case report, 18F-FDG PET/CT scan showed left and right hepatic subcapsular liver low-density lesions, with slightly increased uptake of FDG (SUVmax = 4.09, 3.42). In addition, PET/CT imaging can pinpoint high metabolic sites for biopsy, and at the same time exclude abnormalities of other parts of the body. Histopathological and immunohistochemical studies are, however, necessary for the definitive diagnosis.

Albano et al[9,20,23] described 5 cases of primary hepatic MALT lymphoma and reported a series of 18F-FDG PET/CT scans performed to evaluate those patients. They recognized that hepatic MALT lymphomas could be studied with 18F-FDG PET/CT like other 18F-FDG-avid lymphomas. According to the Lugano classification,[23] primary liver MALT lymphoma can use 18F-FDG PET/CT-high metabolic activity as other lymphoma shows. Therefore, 18F-FDG PET/CT high metabolic uptake can be helpful in various aspects, notably: in staging the disease, evaluation of treatment response, and in monitoring on the liver for relapse and recurrence. Although the number of cases is small, accumulating experience of using 18F-FDG PET/CT in diagnosing liver cancer and primary hepatic lymphoma MALT is necessary.

In our review, all 9 cases showed increased uptake of FDG of the hepatic MALT lesions. In 2 of the cases the hypermetabolic hepatic lesions were apparent with delayed FDG PET imaging. This may indicate that delayed FDG PET/CT imaging may be more trustworthy in detecting tumors. Mayerhoefer et al[24] also described that, compared with standard-time-point FDG PET, delayed time-point FDG PET imaging can increase lesion-to-liver and lesion-to-blood contrast and may improve detectability of MALT lymphoma in liver.

The discussed literatures suggest that 18F-FDG PET/CT potentially offers new diagnostic insights for primary hepatic MALT lymphoma, even though it cannot substitute pathological evidence for a definitive diagnosis. The analysis of SUV of primary hepatic MALT lymphoma remains to be validated by more proof. Further investigation is needed to come up with an agreed-upon SUV of primary MALT lymphoma.[25]

In our present study, hepatic marginal zone B cell lymphoma displayed a 5-year overall survival (OS) (60%) and median OS (82.9 months), similar to what have been reported with 8 Japanese primary hepatic MALT lymphoma cases (84 months).[26] In another review, median OS was reported to be 65 months for 18 cases analyzed.[26]

Because of the small population of primary hepatic MALT lymphoma patients, there are no strict recommended treatment guidelines or consensus.[15,25,27,28] The treatment options currently include surgery, chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and combined therapy. For the solitary lesions of small size with preserved liver function, resection is mostly preferred and prognosis is better. Surgical treatment can be performed either before or after chemotherapy to reduce tumor burden. It is reported that the recurrence rate (48%) of non-gastric lymphoma (including liver) is significantly higher than gastric MALT lymphoma (22.2%).[20,23] So it is recommended that MALT should be combined with chemotherapy or immunotherapy after operation. Rituximab[29] or Idelalisib is an appropriate treatment in relapsed cases.[12] Rituximab[30,31] is an anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody and has been shown to be effective in MALT lymphoma with remission rates of 55% to 73% without risk of HCV reactivation.[13] Patients with hepatic MALT lymphoma should be closely followed up for recurrence. However, it is regretful that our patient has refused any further treatment.

Primary hepatic MALT lymphoma is a rare disease. There is no specific feature to accurately diagnose it from its clinical manifestations, laboratory examinations, or imaging studies. As far as 18F-FDG PET/CT imaging is concerned, MALT lymphoma demonstrates an increased FDG uptake. Delayed FDG PET/CT scan is also an option and is believed to improve detection of hepatic MALT lymphoma lesions. The pathological examinations including immunohistochemistry, flow cytometry, and karyotype analysis remain the most reliable tools that may help through the differential diagnosis. Unfortunately, there is no uniform guideline for the treatment of primary hepatic lymphoma MALT presently. Recent data on 18F-FDG PET/CT imaging in the evaluation of hepatic MALT lymphoma have possibly brought to light a prospective gateway toward an improved management. Nonetheless, further clinical and experimental studies, together with multicenter collaboration, are needed to supplement and polish our current understanding of the disease.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the patient and all the investigators, including the physicians, nurses, and laboratory technicians associated with this study.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: γ-GT = gamma glutamyl peptidase, 18F-FDG PET = fluorine-18-fluorodeoxyglucosepositron emission tomography, CT = computed tomography, IH = immune histochemical, MALT = mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue, NHL = non-Hodgkin lymphoma, SUV = standard uptake value, WBC = white blood cell.

CB and JW have equally contributed to this work.

Funding: This study is sponsored by Natural Science Project of Zhejiang Province (GF18H180002).

Ethical approval: This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent: Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- [1].Takahashi H, Sawai H, Matsuo Y, et al. Reactive lymphoid hyperplasia of the liver in a patient with colon cancer: report of two cases. BMC Gastroenterol 2006;6:25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Dong A, Xiao Z, Yang J, et al. CT, MRI, and 18F-FDG PET/CT findings in untreated pulmonary and hepatic b-cell lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) over a five-year period: a case report. Medicine 2016;95:e3197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Thieblemont C, Berger F, Dumontet C, et al. Mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma is a disseminated disease in one third of 158 patients analyzed. Blood 2000;95:802–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Li LX, Zhou ST, Ji X, et al. Misdiagnosis of primary hepatic marginal zone B cell lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue type, a case report. World J Surg Oncol 2016;14:69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Ianotto JC, Tempescul A, Eveillard JR, et al. Acute dyspnoea and single tracheal localisation of mantle cell lymphoma. J Hematol Oncol 2010;3:34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].El-Fattah MA. Non-Hodgkin lymphoma of the liver: a US population-based analysis. J Clin Transl Hepatol 2017;5:83–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Yang XW, Tan WF, Yu WL, et al. Diagnosis and surgical treatment of primary hepatic lymphoma. World J Gastroenterol 2010;16:6016–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Zucca E, Conconi A, Pedrinis E, et al. Nongastric marginal zone B-cell lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue. Blood 2003;101:2489–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Albano D, Giubbini R, Bertagna F. 18F-FDG PET/CT and primary hepatic MALT: a case series. Abdom Radiol (New York) 2016;41:1956–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Bronowicki JP, Bineau C, Feugier P, et al. Primary lymphoma of the liver: clinical-pathological features and relationship with HCV infection in French patients. Hepatology (Baltimore, Md) 2003;37:781–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Hayashi M, Yonetani N, Hirokawa F, et al. An operative case of hepatic pseudolymphoma difficult to differentiate from primary hepatic marginal zone B-cell lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue. World J Surg Oncol 2011;9:3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Obiorah IE, Johnson L, Ozdemirli M. Primary mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma of the liver: a report of two cases and review of the literature. World J Hepatol 2017;9:155–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Nagata S, Harimoto N, Kajiyama K. Primary hepatic mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma: a case report and literature review. Surg Case Rep 2015;1:87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Zhong Y, Wang X, Deng M, et al. Primary hepatic mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma and hemangioma with chronic hepatitis B virus infection as an underlying condition. Biosci Trends 2014;8:185–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Doi H, Horiike N, Hiraoka A, et al. Primary hepatic marginal zone B cell lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue type: case report and review of the literature. Int J Hematol 2008;88:418–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Iida T, Iwahashi M, Nakamura M, et al. Primary hepatic low-grade B-cell lymphoma of MALT-type associated with Helicobacter pylori infection. Hepatogastroenterology 2007;54:1898–901. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Isaacson PG, Banks PM, Best PV, et al. Primary low-grade hepatic B-cell lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT)-type. Am J Surg Pathol 1995;19:571–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Raderer M, Streubel B, Woehrer S, et al. High relapse rate in patients with MALT lymphoma warrants lifelong follow-up. Clin Cancer Res 2005;11:3349–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Perry C, Herishanu Y, Metzer U, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of PET/CT in patients with extranodal marginal zone MALT lymphoma. Eur J Haematol 2007;79:205–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Hamada T, Kakizaki S, Koiso H, et al. Primary hepatic mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma. Clin J Gastroenterol 2013;6:150–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Weiler-Sagie M, Bushelev O, Epelbaum R, et al. (18)F-FDG avidity in lymphoma readdressed: a study of 766 patients. J Nucl Med 2010;51:25–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Park YK, Choi JE, Jung WY, et al. Mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma as an unusual cause of malignant hilar biliary stricture: a case report with literature review. World J Surg Oncol 2016;14:167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Cheson BD, Fisher RI, Barrington SF, et al. Recommendations for initial evaluation, staging, and response assessment of Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin lymphoma: the Lugano classification. J Clin Oncol 2014;32:3059–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Mayerhoefer ME, Giraudo C, Senn D, et al. Does delayed-time-point imaging improve 18F-FDG-PET in patients with MALT lymphoma?: Observations in a series of 13 patients. Clin Nucl Med 2016;41:101–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Yu YD, Kim DS, Byun GY, et al. Primary hepatic marginal zone B cell lymphoma: a case report and review of the literature. Indian J Surg 2013;75(Suppl 1):331–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Kikuma K, Watanabe J, Oshiro Y, et al. Etiological factors in primary hepatic B-cell lymphoma. Virchows Archiv 2012;460:379–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Cirocchi R, Farinella E, Trastulli S, et al. Surgical treatment of primitive gastro-intestinal lymphomas: a systematic review. World J Surg Oncol 2011;9:145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Brito-Zeron P, Kostov B, Fraile G, et al. Characterization and risk estimate of cancer in patients with primary Sjogren syndrome. J Hematol Oncol 2017;10:90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Dong S, Chen L, Chen Y, et al. Primary hepatic extranodal marginal zone B-cell lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue type: a case report and literature review. Medicine 2017;96:e6305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Epperla N, Ahn KW, Ahmed S, et al. Rituximab-containing reduced-intensity conditioning improves progression-free survival following allogeneic transplantation in B cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma. J Hematol Oncol 2017;10:117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Cang S, Mukhi N, Wang K, et al. Novel CD20 monoclonal antibodies for lymphoma therapy. J Hematol Oncol 2012;5:64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]