Abstract

In recent years, Mexico has seen one of the largest increases in suicide rate worldwide, especially among adolescents and young adults. This study uses data from the 1,071 respondents that participated in a two wave longitudinal study when they were between 12 and 17 years of age, and again when they were between 19 and 26 years of age. The World Mental Health Composite International Diagnostic Interview assessed suicidal behavior and DSM-IV mental disorders. We used Cox regressions to evaluate which socio-demographic and psychiatric factors and life events predicted the incidence and remission of suicide ideation, plan, and attempt throughout the 8-year span. The eight-year incidence of suicide ideation, plan and attempt was 13.3%, 4.8% and 5.9% respectively. We found that the number of traumatic life-events during childhood, no longer being in school, and tobacco use predicted which adolescents developed suicide behaviors as they transitioned into young adulthood. Psychiatric disorders, particularly anxiety disorders, played a larger role in the persistence of those who already had suicidal behavioral while behavioral disorders played a role in the transition from ideation to attempts. This distinction may be useful for clinicians to assess the risk of suicide.

Keywords: suicide, longitudinal study, incidence, traumatic life events, Mexico

In recent years, the suicide rate in many countries has been decreasing (WHO, 2014). However, Mexico is experiencing one of the largest increments when compared to 28 other countries (Bridge, Goldstein, & Brent, 2006). This rise has been especially high for adolescents and young adults (Borges, García, Orozco, Benjet, & Medina-Mora, 2014). Suicide related outcomes (SROs) such as ideation, plan and attempts are precursors to suicide death and thus are important risk factors. Previous epidemiological research found that 11.5% of adolescents in Mexico had suicide ideations, and 3.1% had made a suicide attempt (Borges, Benjet, Medina-Mora, Orozco, & Nock, 2008c). Because this demographic is at especially high risk, it is imperative to identify risk factors and create predictive models that may be useful for intervention programs to target those in need.

Cross-sectional representative community surveys have shown that suicide ideation is common in the general population and often acts as a precursor of suicide attempts (Bernal et al., 2007; Borges, Nock, Medina-Mora, Benjet, Lara, Chiu, & Kessler, 2007). Other risk factors identified include: being female (Borges et al., 2008c), having lived through a traumatic life event (Borges, Benjet, Medina-Mora, Orozco, Molnar, & Nock, 2008b), using, abusing, and depending on alcohol, tobacco, or drugs (Miller, Borges, Orozco, Mukamal, Rimm, Benjet, & Medina-Mora, 2011), low education (Sánchez-Cervantes, Serrano-González, & Márquez-Caraveo, 2015), and having a psychiatric disorder (Bernal et al., 2007). However, these studies are cross-sectional, and thus limited when trying to make temporal or causal inferences.

Longitudinal prospective studies of SROs, all but one conducted in high income countries, show that drug and alcohol abuse (Allebeck, & Allgulander, 1990a; Flensborg-Madsen et al., 2009), stressful life events (Caspi et al., 2003), a history of major depressive disorder (Werbeloff et al., 2016), adverse childhood experiences (Cluver, Orkin, Boyes, & Sherr, 2015) increase the risk of SROs. The only articles we found looking at suicide behaviors in the transition from adolescence to young adulthood show that the onset of depression (Fergusson, and Lynskey, 1995) and increased use of multiple drugs throughout adolescence (Newcomb, Scheier, & Bentler, 1993) increases the risk of attempting suicide.

The present study evaluates data of a two-wave longitudinal study of adolescents transitioning into young adulthood in Mexico City in order to understand how SROs change through emerging adulthood in the context of a developing country with low, but increasing, rates of suicide mortality. This study is novel in that we measured all SROs and a more complete set of psychiatric disorders (aside from anxiety and depression) during the vulnerable life transition from adolescence to early adulthood. In addition, we provide prospective data from a developing country, and more specifically from Latin America. The only other prior study from a developing country, namely South Africa (Cluver et al, 2015) only followed adolescents for one-year, and thus is not informative about the transition to young adulthood. We will focus on identifying which factors from adolescence predict the incidence and remission of SROs. We use the data from the first wave to predict SROs in the second wave. In addition, the longitudinal design allows us to establish temporal relations between risk factors and SROs.

Method

Participants

3005 adolescents between the ages of 12–17 participated in wave I of the Mexican Adolescent Mental Health Survey. This survey was a stratified multistage area probability sample representative of the nearly two million adolescents that resided in the Mexico City Metropolitan Area in 2005. Eight years later we attempted to locate all the respondents from wave I that gave contact information in order to do a follow-up interview. We were able to re-interview 1071 of the original respondents, now young adults between the ages of 19–26. More details about the design and procedures of the study have been published elsewhere (Benjet, Borges, Medina-Mora, Zambrano, Aguilar-Gaxiola, 2009 for wave I, and Benjet et al, 2016 for wave II). This paper will only look at the data of those 1071 that completed both interviews.

Procedure

The interviews for both waves were conducted face-to-face in the homes of the respondents. Trained lay interviewers provided a verbal and written explanation of the study and obtained informed consent before carrying out the interviews. All study respondents were given a pamphlet of the study findings from wave I and contact information for institutions from which they could seek services should they wish to do so.

Measures

Suicide-related outcomes

Suicide ideation, plan, attempt, and potential risk factors were assessed using the World Mental Health Composite International Diagnostic Interview (WMH-CIDI). The WMH-CIDI contains a module that assesses suicide ideation (“Have you ever seriously thought about committing suicide?”), suicide plans (“Have you ever made a plan for committing suicide?”), and suicide attempts (“Have you ever attempted suicide?”). These questions were printed in a self-administered booklet and referred to by letter, given that reporting of potentially embarrassing behaviors are higher in self-administered questionnaires (Turner et al. 1998). Experience A referred to suicide ideation, B to suicide plan, and C to suicide attempt. Interviewers asked respondents to report whether the experiences had ever happened to them (“Three experiences are listed in your booklet on page 19 labeled A, B, and C. Did experience A ever happen to you?”) and, if so, to report the age of onset (AOO). Respondents were also asked to report if the event happened in the last 12 months. If the event did not happen in the last 12 months, participants were asked for the age of recency. Incident cases were defined as those that met lifetime criteria for the SRO in question at wave II, but did not report that SRO at wave I. Persistent cases were defined as those that reported the same SROs in both waves.

Predictors

Interviews also examined three sets of risk factors: sociodemographic factors, psychiatric disorders in the 12 months leading up to the first interview, and traumatic life events. The sociodemographic factors were sex, whether the adolescent had dropped out of school, and whether at least one of the parents finished high school.

Psychiatric disorders were assessed by the WHM-CIDI according to DSM-IV criteria. We examined mood (major depressive disorder, dysthymia, and bipolar disorder), anxiety (panic disorder, agoraphobia without panic disorder, specific phobia, social phobia, generalized anxiety disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder, and separation anxiety disorder), behavioral (oppositional-defiant disorder, conduct disorder, and attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder), and substance use (alcohol abuse, drug abuse, alcohol abuse with dependence, and drug abuse with dependence) disorders. Wave I used the adolescent version of the CIDI, while Wave II used the adult version modified for follow-up. Prior research showed that CIDI diagnoses have good concordance with diagnoses based on the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (First, Spitzer, Gibbon, & Williams, 2002) in respondents from the U.S. (Kessler, Berglund, Demler, Jin, Merikangas, & Walters, 2002) and elsewhere (Haro et al., 2006).

The CIDI also assessed 21 different traumatic life events, such as rape, violence, serious injuries, domestic violence or serious illness. After the presentation of this list of events, the respondent was also able to add “Other” and “Private” events. Participants that answered “other” were asked to give details about the event. The Private Event category was reserved for those that did not feel comfortable disclosing the nature of the trauma (for a full list of the traumatic life events assessed please see the appendix in Orozco, Borges, Benjet, Medina-Mora, & Lopez-Carrillo, 2008).

Parental mental illness was based on participants´ reports of each of their parents´ symptoms of depression, generalized anxiety, or panic disorder, whether these symptoms occurred most of the time, interfered with their parent´s life and whether their parent sought treatment for these symptoms (see Benjet, Borges, & Medina-Mora, 2010 for greater detail).

Analysis

First, we used χ2 tests to evaluate any differences in baseline suicidality between those that did and did not participate in wave II. Second, we performed descriptive analyses to estimate the incidence and remission of SROs and Kaplan-Meier survival curves for age of onset of incident cases and age of remission for persistent cases (Kaplan, & Meier, 1958; Rich, Neely, Paniello, Voelker, Nussenbaum, & Wang, 2010). Then, to assess risk factors for incident cases of SROs we ran three separate survival analyses using Cox regression (Cox, 1975; Grambsch, & Therneau, 1994). For all analyses, we included sex, and the following variables reported in 2005: whether the participant attended school, parental education, whether the participant had an anxiety, mood, behavioral, or substance use disorder, number of lifetime traumatic events, whether the participant had ever smoked tobacco, and reports of parental mental illness as predictors in our model. For the model of persistence we also include whether the participant had sought any mental health services. Additionally, whether the participant reported having a suicide plan in 2005 was included as a predictor in all the analyses of suicide attempts.

We calculated the survival time for incidence by subtracting the participant´s age in 2005 from their AOO plus one. We calculated the survival time for remission by subtracting the AOO from the age of recency in 2013 or the participant’s age in 2013 if they had experienced the event in the last 12 months. When the AOO reported in 2013 did not match the one reported in 2005, we used the one reported in 2005 as it is less likely to have been influenced by forgetting. Some participants reported experiencing the SRO but did not provide AOO or age of recency at either time period; we gave these participants a survival time of 1 to reflect that they had experienced the event.

All results were weighted to adjust for non-response bias to represent the initial 2005 wave I sample. The weights were created by using the variables in 2005 that differed between people that completed wave II and those that did (for more information see Benjet et al., 2016). Additionally, given that wave I was a stratified multistage probabilistic sample based on census data, we used the sample design variables in all of our analysis to adjust the standard errors for the sampling procedure. All percentages reported are weighted as described above.

Results

First, we tested for the possibility of an attrition bias with regards to SROs. Respondents that participated in Wave II did not differ from those that did not in terms of lifetime ideation (χ2(1, N = 3,005) = 1.40, ns), plan (χ2(1, N = 3,005) = 1.11, ns) or attempt (χ2(1, N = 3,005) = .97, ns) nor 12-month ideation (χ2(1, N = 3,005) = .96, ns), plan (χ2(1, N = 3,005) = .85, ns) or attempt (χ2(1, N = 3,005) = .22, ns) at baseline.

Incidence

Ideation

Of the 960 respondents that did not report ever having ideation in 2005, 121 (13.37%) (this and following proportions are weighted) reported having developed suicide ideation in the eight years between 2005 and 2013. The mean AOO for the new cases of ideation was 16.69 (SD = 2.47). Thirty-six (30.50%) of the new cases of ideation also reported making a plan in the last eight years, and 12 (9.81%) in the last 12 months. The mean AOO for making a plan among the new cases of ideation was 16.61 (SD = 2.69). Of the incident cases of ideation, 53 (43.04%) also reported an attempt in the last eight years, and 14 (8.21%) reported an attempt in the last 12 months. The mean AOO for suicide attempt among the new cases of ideation was 16.75 (SD = 2.46).

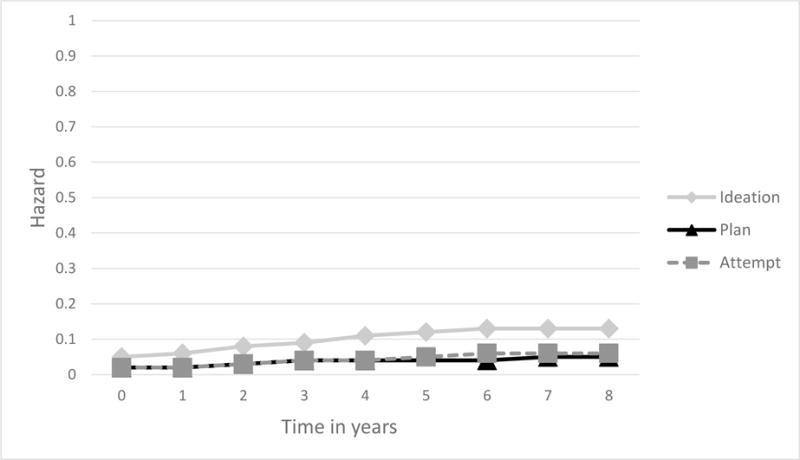

Table 1 shows the wave I socio-demographic, psychiatric and life event predictors of SROs in the transition from adolescence to early adulthood as estimated by hazard ratios (HR) in multivariate models. Figure 1 displays the hazard curves for the incidence of the SROs. For suicidal ideation, the adjusted model showed that an increment of one traumatic life event at baseline (HR = 1.26; 95%CI = 1.14–1.41; p < .001) increased 26% the risk of having incident suicide ideation. Participants had between zero and nine traumatic life events, with a mean of 2.22 events. Being a student in 2005 reduced the risk of suicide ideation (HR = .46; 95%CI = .26 – .81; p = .005).

Table 1.

Socio-demographic, psychiatric and life events predictors of incidence of suicidal behavior in the transition from adolescence to early adulthood

| Ideation

|

Plan

|

Attempt

|

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 960, incidence = 121

|

N = 1036, incidence = 47

|

N = 1041, incidence = 61

|

||||||||

| Wave I factors | HR | 95% CI | p | HR | 95% CI | p | HR | 95% CI | p | |

| Demographic | ||||||||||

| Female Sex | 1.64 | .81–3.32 | .154 | 1.73 | .83–3.61 | .128 | 2.07 | .76–5.62 | .138 | |

| In school | .46 | .26–.81 | .005 | 0.94 | .37–2.39 | .892 | .68 | .30–1.52 | .326 | |

| Parental education | .96 | .60–1.53 | .851 | 1.09 | .60–1.97 | .772 | .98 | .59–1.62 | .920 | |

| Psychiatric disorders | ||||||||||

| Any Anxiety disorders | .99 | .59–1.67 | .984 | .64 | .33–1.25 | .178 | .58 | .28–1.17 | .114 | |

| Any Mood disorders | 1.06 | .50–2.24 | .871 | 1.08 | .38–3.06 | .878 | 1.02 | .31–3.36 | .974 | |

| Any Behavioral disorders | 1.50 | .78–2.87 | .207 | 1.69 | .66–4.33 | .256 | 1.48 | .86–2.57 | .144 | |

| Any Substance use disorders | 1.02 | .37–2.79 | .974 | 1.19 | .22–6.45 | .836 | 1.10 | .19–6.22 | .911 | |

| Life events | ||||||||||

| Number of traumatic life events | 1.26 | 1.14–1.41 | < .001 | 1.24 | 1.02–1.52 | .027 | 1.36 | 1.15–1.61 | < .001 | |

| Lifetime tobacco use | 1.21 | .73–2.02 | .444 | 2.23 | 1.20–4.14 | .008 | 1.55 | .97–2.48 | .058 | |

| Parent mental illness | .71 | .40–1.24 | .209 | 1.40 | .60–3.29 | .417 | .83 | .39–1.78 | .614 | |

| Suicide | ||||||||||

| Plan | Not Applicable | Not Applicable | .76 | .10–5.72 | .784 | |||||

| χ2= 184.77; p < 0.001 | χ2= 57.29; p < 0.001 | χ2= 274.9; p < 0.001 | ||||||||

Figure 1.

Hazard curves for the incidence of SROs

Plan

Out of the 1036 respondents that did not report making a suicide plan in their lifetime in 2005 (whether or not they had ideations or attempts), 47 (4.84%) reported having made a plan in the eight years between 2005 and 2013. The mean AOO for the incident cases of making a plan was 16.57 (SD = 2.62). Of these 47 new cases of plan, 31 (67.34%) had attempted suicide since 2005, and 8 (11.38%) had attempted suicide in the last 12 months.

Also shown on Table 1, the adjusted survival model showed that having more traumatic life events at baseline (HR = 1.24; 95%CI = 1.02–1.52; p = .027), and smoking tobacco (HR = 2.23; 95%CI = 1.20–4.14; p = .008) increased the risk of making an incident suicide plan. As shown on Table 2, among those that had suicide ideation in 2005, having parents that finished high school (HR = 4.26; 95%CI = 1.30–14.01; p = .013), and having parents with a history of mental illness (HR = 18.09; 95%CI = 3.45–94.75; p < .001) increased the risk of making a suicide plan. Having more traumatic events (HR = .58; 95%CI = .35–.97; p = .030) and having a behavioral disorder (HR = .22; 95%CI = .05–.88; p = .026) reduced the risk of making a suicide plan.

Table 2.

Socio-demographic, psychiatric and life events predictors of the incidence of suicide plans and attempts among people with suicide ideation in 2005

| Incidence of Plan among ideators

|

Incidence of Attempt among ideators

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 76, incidence = 11

|

N = 81, incidence = 8

|

|||||

| Wave I factors | HR | 95% CI | p | HR | 95% CI | p |

| Demographic | ||||||

| Female Sex | 1.61 | .29–8.89 | .573 | 13.20 | 2.17–80.16 | .004 |

| In school | .53 | .08–3.34 | .481 | 1.63 | .01–266.86 | .845 |

| Parental education | 4.26 | 1.30–14.01 | .013 | 4.41 | .46–42.43 | .182 |

| Psychiatric disorders | ||||||

| Any Anxiety disorders | 1.17 | .26–5.34 | .832 | .81 | .03–22.46 | .899 |

| Any Mood disorders | 1.72 | .43–6.92 | .429 | .23 | .01–7.88 | .393 |

| Any Behavioral disorders | .22 | .05–.88 | .026 | 27.45 | 4.65–165.9 | < .001 |

| Any Substance use disorders | Too few to estimate | Too few to estimate | ||||

| Life events | ||||||

| Number of traumatic life events | .58 | .35–.97 | .030 | 1.48 | 1.09–2.00 | .008 |

| Lifetime tobacco use | .40 | .11–1.44 | .145 | 1.61 | .13–20.27 | .701 |

| Parent mental illness | 18.09 | 3.45–94.75 | < .001 | 7.68 | 1.56–37.80 | .009 |

| Suicide | ||||||

| Plan | Not Applicable | .51 | .09–2.93 | .433 | ||

| χ2= 316.45; p < 0.001 | χ2= 336.85; p < 0.001 | |||||

Attempt

Of the 1041 respondents that did not report ever attempting suicide when interviewed in 2005 (whether or not they had made a plan), 61 (5.87%) reported having a suicide attempt in the following eight years. Of those, 30 (52.81%) reported making a plan since 2005 and 9 (13.96%) reported making a plan in the last 12 months. The mean AOO for the incidence of attempting suicide was 16.70 (SD = 2.40). Attempters without a plan tended to have a later AOO (M = 17.30, SD = 2.22) when compared to attempters with a plan (M = 16.19, SD = 2.62), however this difference was only marginally significant, t (57.85) = 1.87, p = .067.

The adjusted model for incident suicide attempts presented on Table 1 showed that each traumatic life event increased the risk of attempting by 36% (HR = 1.36; 95%CI = 1.15–1.61; p < .001). Among those that had suicide ideation in 2005, but had not made an attempt (as shown on Table 2), being female (HR = 13.20; 95%CI = 2.17–80.16; p = .004), having more traumatic life events (HR = 1.48; 95%CI = 1.09–2.00; p = .008), having a behavioral disorder (HR = 27.45; 95%CI = 4.64–165.9; p < .001), and having parents with a history of mental illness (HR = 7.68; 95%CI = 1.56–37.80; p = .009) increased the risk of subsequently attempting suicide.

Persistence and remission

Ideation

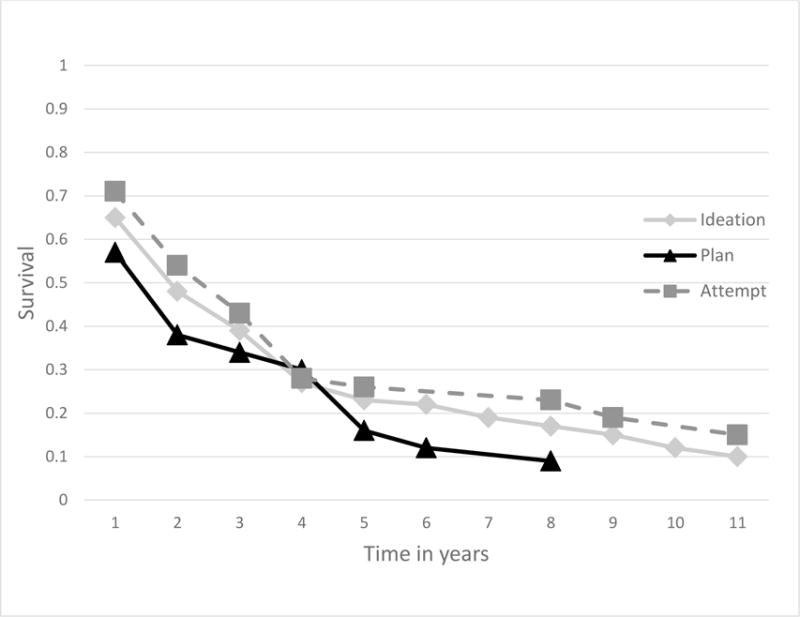

Out of the 111 respondents that reported ever having ideation when interviewed in 2005, 13 (10.64%) reported having an ideation in the last 12 months in 2013. The mean age of recency was 16.50 (SD = 2.53) for all ideators that remitted, and respondents reported having ideations for a mean of 4.20 years (SD = 3.57). Of these persistent cases, 48.28% also reported making a plan in the last 12 months. Additionally, 34.54% reported attempting suicide in the last 12 months. Figure 2 displays the Kaplan-Meier survival curves for remission of the SROs, the probability of survival as a function of time. The x-axis goes beyond the eight-year span of our study because some participants reported having SROs before wave I. The figure shows that most people that have SROs will remit in the first five years, and that the number that has had them for longer becomes stable over time.

Figure 2.

Survival curves for the remission of SROs

Table 3 presents the socio-demographic, psychiatric, and life event predictors of remission. The adjusted model for the remission of suicide ideation showed that having an anxiety disorder (HR = 0.54; 95%CI = 0.32–0.91; p = .016) and having parents that completed high school (HR = 0.58; 95%CI = 0.39–0.85; p = .004) reduced the likelihood of remission.

Table 3.

Socio-demographic, psychiatric and life events predictors of remission of suicidal behaviors in the transition for adolescence to early adulthood

| Ideation

|

Plan

|

Attempt

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 111, remission = 98

|

N = 35, remission = 32

|

N = 30 remission = 26

|

|||||||

| Wave I factors | HR | 95% CI | p | HR | 95% CI | p | HR | 95% CI | p |

| Demographic | |||||||||

| Female Sex | .85 | .54–1.32 | .444 | .89 | .51–1.55 | .667 | 2.57 | 1.27–5.20 | .006 |

| In school | 1.27 | .61–2.64 | .502 | .29 | .10–.82 | .016 | .54 | .22–1.35 | .171 |

| Parental education | .58 | .39–.85 | .004 | .77 | .41–1.46 | .406 | 1.07 | .47–2.48 | .863 |

| Psychiatric disorders | |||||||||

| Any Anxiety disorders | .54 | .32–.91 | .016 | .71 | .34–1.51 | .358 | .24 | .08–.74 | .010 |

| Any Mood disorders | 1.28 | .76–2.15 | .336 | 1.04 | .36–2.94 | .946 | .35 | .12–1.02 | .045 |

| Any Behavioral disorders | .97 | .60–1.58 | .900 | .27 | .13–.54 | <.001 | 2.15 | .95–4.89 | .057 |

| Any Substance use disorders | 1.64 | .84–3.18 | .129 | .79 | .14–4.54 | .786 | .89 | .26–3.04 | .847 |

| Life events | |||||||||

| # of traumatic life events | 1.01 | .92–1.12 | .796 | .92 | .75–1.13 | .412 | 1.23 | 1.11–1.37 | <.001 |

| Lifetime tobacco use | .78 | .49–1.25 | .284 | 2.15 | .90–5.16 | .073 | 1.49 | .79–2.81 | .197 |

| Any lifetime mental health service use | .99 | .59–1.67 | .983 | 1.35 | .69–2.64 | .354 | .65 | .20–2.18 | .470 |

| Parent mental illness | .89 | .52–1.54 | .665 | .86 | .40–1.88 | .703 | 2.16 | .67–6.91 | .178 |

| Suicide | |||||||||

| Plan | Not Applicable | Not Applicable | .71 | .26–1.94 | .486 | ||||

| χ2= 40.35; p < .001 | χ2= 146.48; p < .001 | χ2= 283.89; p < .001 | |||||||

Plan

Of the 35 respondents that reported making a plan when interviewed in 2005, three (9.23%) reported making a plan in the last 12 months when interviewed in 2013. The mean age of recency was 17.25 (SD = 2.54), and respondents reported having a plan for a mean of 3.56 years (SD = 3.29).

The adjusted model for the remission of suicide plan as presented on Table 3 showed that having a behavioral disorder (HR = 0.27; 95%CI = 0.13–0.54; p < .001) and being in school in 2005 (HR = 0.29; 95%CI = 0.10–0.82; p = .016) reduced the likelihood of remission.

Attempt

Out of the 30 participants that reported a suicide attempt when interviewed in 2005, four (13.79%) reported attempting suicide in the last 12 months when interviewed in 2013.

The adjusted model for the remission of suicide attempt presented on Table 3 showed that having an anxiety (HR = 0.24; 95%CI = 0.08–0.74; p = .010) or mood disorder (HR = 0.35; 95%CI = 0.12–1.02; p = .045) reduced the likelihood of remission. Additionally, being female (HR = 2.57; 95%CI = 1.27–5.20; p = .006) and having more traumatic life events (HR = 1.23; 95%CI = 1.11–1.37; p < .001) increased the probability of remission. Table 3 shows the results of the multivariate model for the remission of attempt.

Discussion

We evaluated the incidence and persistence of suicidal behavior in an eight-year period from adolescence to young adulthood in Mexican youth from Mexico City. Our findings show that even though the incidence rate is high (13.37% for ideation) fortunately the eight year persistence was low. This is not to say that incidence is not worrisome as a fatality may occur on the first attempt. Because traumatic life events increased the risk of incident SROs, suicide behaviors are likely to be triggered by a specific traumatic event. It is possible that once the event passes or the psychological consequences of the event subside, so does suicidal behavior. It is at this point, where having a psychiatric disorder (whether it is a mood, anxiety, or behavioral disorder), increases the odds of persistent suicide behaviors. Therapy would help support the adolescent until the triggering event passes, and treatment of anxiety disorders, in particular, may help increase the chances of remission.

For incidence, all SROs had a mean AOO around 16 years of age indicating this as a critical age in the development of suicide behaviors. In Mexico, this is the age in which adolescents either enter high school, or stop studying. Given that being in school was a protective factor for the incidence of ideation, it is imperative to focus on those that drop out of school at the age of 16 as they may be more likely to develop SROs. Having more traumatic life events by adolescence increased the likelihood of developing all suicide behaviors by young adulthood. Among people that had suicide ideation, having a parent with a history of mental illness predicted the worsening of their condition, making them more likely to develop a plan and attempt suicide.

Many studies have found that psychiatric disorders increase the risk of having suicide behaviors (Andrews, & Lewinsohn, 1992; Bernal et al., 2007; Borges, Angst, Nock, Ruscio, & Kessler, 2008a; Clarke et al., 2014; Reinherz et al., 1995), however we did not find this in our study in the multivariate models though several showed associations in bivariate models (not shown here). One possibility for the lack of association is that experiencing traumatic events before adolescence causes both psychiatric disorders and suicide behaviors. Some studies have already shown that traumatic life events may lead to the development of psychiatric disorders above and beyond posttraumatic stress disorder (Avenevoli, Knight, Kessler, & Merikangas, 2008; Benjet et al., 2016). By including the diagnostic clusters in the models, we could be masking the effects of individual disorders, but small sample sizes impeded including individual disorders and this lack of statistical power may also explain the null effects. In addition, Fergusson and Lynskey (1995) and Cluver et al. (2015) showed that early childhood adversities increase the odds of developing suicide behaviors. If both conditions have the same root cause, they might appear to be related, but this relation might not be causal.

Another possibility is that psychiatric disorders might be better predictors of suicidality during adulthood than during the transition between adolescence and young adulthood. During this developmental stage, other factors such as one’s relationship with parents (Bridge et al, 2006), abuse of substances (Allebeck, & Allgulander, 1990a; Allebeck, & Allgulander, 1990b; Chávez-Hernández, & Macías-García, 2016; Reinherz et al., 1995), not being in school (Benjet et al. 2016), and knowing peers that attempted suicide (Ho, Leung, Hung, Lee, & Tang, 2000) might play a bigger role in determining which adolescents will develop suicide behaviors.

While psychiatric disorders did not play a role in the overall incidence of suicidal behavior, they did play a role in the incidence of transition from ideation to plan and from ideation to attempt. Among ideators, having a behavioral disorder decreased the likelihood of making a plan, but increased the risk of attempting suicide more than 20-fold. Adolescents with behavioral disorders may lack the impulse control necessary to not attempt suicide once the ideations occur, thus their attempts may not be premeditated.

Finally, it is possible that psychiatric disorders do not play a big role in the development of suicide behaviors, but do so in the persistence of these behaviors. We found that adolescents that had an anxiety disorder as well as suicide ideations or attempts were more likely to continue experiencing those behaviors. This is consistent with previous studies that analyzed the impact of anxiety disorders, as a cluster, on suicide ideation and attempt in a community sample (Sareen, Cox, Afifi, de Graaf, Asmundson, Have, Stein, 2005). Additionally, adolescents that had behavioral disorders were more likely to persist in making a suicide plan, and those who had mood disorders were more likely to continue having suicide attempts. This is consistent with research that shows people that are admitted into the emergency room for attempting suicide are more likely to have mood disorders (Kawashima, Yonemoto, Inagaki, & Yamada, 2014), and longitudinal studies showing that having a mood disorder increases the risk of attempting suicide (Clarke et al., 2014).

The results should be interpreted in light of the current study´s limitations. One of the limitations is that the small sample sizes of those that engaged in SROs limited statistical power, especially for remission, thus confidence intervals are large and lack of associations with psychiatric disorders may be due to this. Likewise, because of this, we were unable to include individual disorders in the models, but rather groups of disorders. Another limitation is the attrition rate. However, we did not find any difference among those that did or did not complete the second interview with regard to SROs or psychiatric disorders (Benjet et al, 2016) at baseline. Also, given that participants were not interviewed on a yearly basis we cannot be certain about the exact beginning and end points of their suicide behaviors. Further, adolescents that were institutionalized and homeless did not to participate. This at-risk population could differ from the study population in frequency or onset of SROs. Additionally, while we assessed a large array of psychiatric disorders, we did not assess for all disorders included in the DSM- IV. Schizophrenia, for example was not included, but is likely to be related to an increase in suicide behaviors (Harkavy-Friedman, Nelson, Venarde, & Mann, 2004). Finally, this study only included adolescents living in the Mexico City Metropolitan Area, which limits the generalization to youth living elsewhere.

In spite of these limitations the current research has several strengths. It is novel because we assessed suicide behaviors at a critical transition period. This is also one of the few longitudinal studies regarding SROs carried out in a developing country, and among those studies we assessed a greater number of psychiatric disorders and for a longer period of time. These findings have implications for future research, clinical practice and public policy. First, 16 years of age seems to be a pivotal age for adolescents developing suicide behaviors. Clinicians should place more attention at this age in order to prevent deaths by suicide. Future research should investigate the changes that occur at this age to lead to this increase. Second, the number of traumatic life events and not psychiatric disorders increased the risk of developing SROs. Third, having an anxiety disorder increased the risk of continuing to engage in suicide behaviors once they’ve started. Clinicians should be aware of this difference in risk factors to better assess the likelihood of subsequent suicidal behaviors. Fourth, because traumatic life events rather than psychiatric disorders predicted incident suicidal behaviors, many youth that are never seen in clinical settings are at risk.

Acknowledgments

Wave I of the Mexican Adolescent Mental Health Survey was supported by the National Council on Science and Technology and Ministry of Education (grant CONACYT-SEP-SSEDF-2003-CO1-22). Wave II was supported by the National Council on Science and Technology (grant CB-2010-01-155221) with supplementary support from Fundación Azteca. The survey was carried out in conjunction with the World Health Organization World Mental Health (WMH) Survey Initiative. We thank the WMH staff for assistance with instrumentation, fieldwork, and data analysis. Writing of the manuscript was supported in part by a grant from the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities, T37 MD003405.

Footnotes

MR. DAVID MENENDEZ (Orcid ID : 0000-0002-0248-5940)

DR. RICARDO OROZCO (Orcid ID : 0000-0002-6580-585X)

References

- Allebeck P, Allgulander C. Psychiatric diagnoses as predictors of suicide a comparison of diagnoses at conscription and in psychiatric care in a cohort of 50 465 young men. British Journal of Psychiatry. 1990a;157:339–344. doi: 10.1192/bjp.157.3.339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allebeck P, Allgulander C. Suicide among young men: psychiatric illness, deviant behaviour and substance abuse. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1990b;81:565–570. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1990.tb05500.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews JA, Lewinsohn PM. Suicidal attempts among older adolescents: prevalence and co-occurrence with psychiatric disorders. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1992;31:655–662. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199207000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avenevoli S, Knight E, Kessler RC, Merikangas KR. Epidemiology of depression in children and adolescents. Handbook of depression in children and adolescents. 2008:6–32. [Google Scholar]

- Benjet C, Borges G, Medina-Mora ME. Chronic childhood adversity and onset of psychopathology during three life stages: Childhood, adolescence and adulthood. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2010;44:732–740. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2010.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjet C, Borges G, Medina-Mora ME, Zambrano J, Aguilar-Gaxiola S. Youth mental health in a populous city of the developing world: results from the Mexican Adolescent Mental Health Survey. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2009;50(4):386–395. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2008.01962.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjet C, Borges G, Mendez E, Albor Y, Casanova L, Orozco R, Medina-Mora ME. Eight-year incidence of psychiatric disorders and service use from adolescence to early adulthood: longitudinal follow-up of the Mexican Adolescent Mental Health Survey. European Child Adolescent Psychiatry. 2016;25:163–173. doi: 10.1007/s00787-015-0721-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernal M, Haro JM, Bernert S, Brugha T, de Graaf R, Bruffaerts R, Alonso J. Risk factors for suicidality in Europe: results from the ESEMED study. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2007;101:27–34. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2006.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bridge JS, Goldstein TR, Brent DA. Adolescent suicide and suicidal behavior. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2006;47:372–394. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2006.01615.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borges G, Angst J, Nock MK, Ruscio AM, Kessler RC. Risk factors for the incidence and persistence of suicide-related outcomes: a 10-year follow-up study using the National Comorbidity Surveys. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2008a;105:25–33. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2007.01.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borges G, Benjet C, Medina-Mora ME, Orozco R, Molnar BE, Nock MK. Traumatic events and suicide-relates outcomes among Mexico City adolescents. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2008b;49:654–666. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01868.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borges G, Benjet C, Medina-Mora ME, Orozco R, Nock M. Suicide ideation, plan, and attempt in the Mexican adolescent mental health survey. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2008c;47:41–52. doi: 10.1097/chi.0b013e31815896ad. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borges G, Nock MK, Medina-Mora ME, Benjet C, Lara C, Chiu WT, Kessler RC. The epidemiology of suicide-related outcomes in Mexico. Suicide and the Life-Threatening Behavior. 2007;37:627–640. doi: 10.1521/suli.2007.37.6.627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borges G, García JA, Orozco R, Benjet C, Medina-Mora ME. Suicidio. In: de la Fuente JR, Heinze G, editors. Salud Mental y Medicina Psicológica. McGraw-Hill; Interamericana Editores: 2014. pp. 195–202. [Google Scholar]

- Caspi A, Sugden K, Moffitt TE, Taylor A, Craig IW, Harrington H, Poulton R. Influence of life stress on depression: moderation by a polymorphism in the 5-HTT gene. Science. 2003;301:386–389. doi: 10.1126/science.1083968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chávez-Hernández AM, Macías-García LF. Understanding suicide in socially vulnerable contexts: psychological autopsy in a small town in Mexico. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. 2016;46:3–12. doi: 10.1111/sltb.12166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke MC, Coughlan H, Harley M, Connor D, Power E, Lynch F, Cannon M. The impact of adolescent cannabis use, mood disorders and lack of education on attempted suicide in young adulthood. World Psychiatry. 2014;13:322–323. doi: 10.1002/wps.20170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cluver L, Orkin M, Boyes ME, Sherr L. Child and adolescent suicide attempts, suicide behavior, and adverse childhood experiences in South Africa: a prospective study. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2015;57:52–59. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2015.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox DR. Partial likelihood. Biometrika. 1975;62(2):269–276. [Google Scholar]

- Fergusson DM, Lynskey MT. Suicide attempts and suicidal ideation in a birth cohort of 16-year-old New Zelanders. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1995;34:1308–1317. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199510000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams J. Structural Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (SCID-IV) New York: Biometrics Research Department, New York State Psychiatric Institute; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Flensborg-Madsen T, Knop J, Mortensen EL, Becker U, Sher L, Grønbæk M. Alcohol use disorders increase the risk of completed suicide- irrespective of other psychiatric disorders. A longitudinal cohort study. Psychiatry Research. 2009;167:123–130. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2008.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grambsch PM, Therneau TM. Proportional hazards tests and diagnostics based on weighted residuals. Biometrika. 1994;81(3):515–526. [Google Scholar]

- Harkavy-Friedman JM, Nelson EA, Venarde DF, Mann JJ. Suicidal behavior in schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder: examining the role of depression. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. 2004;34(1):66–76. doi: 10.1521/suli.34.1.66.27770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haro JM, Arbabzadeh-Bouchez S, Brugha TS, De Girolamo G, Guyer ME, Jin R, Sampson NA. Concordance of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview Version 3.0 (CIDI 3.0) with standardized clinical assessments in the WHO World Mental Health surveys. International journal of methods in psychiatric research. 2006;15:167–180. doi: 10.1002/mpr.196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho TP, Leung PW, Hung SF, Lee CC, Tang CP. The mental health of the peers of suicide completers and attempters. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2000;41:301–308. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan EL, Meier P. Nonparametric estimation from incomplete observations. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 1958;53:457–81. [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Merikangas KR, Walters EE. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of general psychiatry. 2005;62:593–602. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawashima Y, Yonemoto N, Inagaki M, Yamada M. Prevalence of suicide attempters in emergence departments in Japan: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal od Affective Disorders. 2014;163:33–39. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2014.03.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller M, Borges G, Orozco R, Mukamal K, Rimm EB, Benjet C, Medina-Mora ME. Exposure to alcohol, drugs and tobacco and the risk of subsequent suicidality: Findings from the Mexican Adolescent Mental Health Survey. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2011;113:110–117. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newcomb MD, Scheier LM, Bentler PM. Effects of adolescent drug use on adult mental health: a prospective study of a community sample. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 1993;1:215–241. [Google Scholar]

- Orozco R, Borges G, Benjet C, Medina-Mora ME, López-Carrillo L. Traumatic life events and posttraumatic stress disorder among Mexican adolescents: results from a survey. Salud pública de México. 2008;50:29–37. doi: 10.1590/s0036-36342008000700006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinherz HZ, Giaconia RM, Silverman AB, Friedman A, Pakiz B, Frost AK, Cohen E. Early psychosocial risks for adolescent suicidal ideation and attempts. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1995;34:599–611. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199505000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rich JT, Neely JG, Paniello RC, Voelker CCJ, Nussenbaum B, Wang EW. A practical guide to understanding kaplan-meier curves. Otolaryngology--Head and Neck Surgery : Official Journal of American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery. 2010;143(3):331–336. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2010.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Cervantes FS, Serrano-González RE, Márquez-Caraveo ME. Suicidios en menores de 20 años. México 1998–2011 [Suicides in minors less tan 20 years old. Mexico 1998–2011] Salud Mental. 2015;38:379–389. [Google Scholar]

- Sareen J, Cox BJ, Afifi TO, de Graaf R, Asmundson GJG, Have MT, Stein MB. Anxiety disorders and risk for suicidal ideation and suicide attempts, a population-based longitudinal study of adults. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:1249–1257. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.11.1249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner CF, Ku L, Rogers SN, Lindber LD, Pleck JH, Sonenstein FL. Adolescent sexual behavior, drug use, and violence: increased reporting with computer survey technology. Science. 1998;280:867–873. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5365.867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werbeloff N, Dohrenwend BP, Levav I, Haklai Z, Yoffe R, Large M, Weiser M. Demographic, behavioral, and psychiatric risk factors for suicide a 25-year longitudinal cohort study. Crisis. 2016;37:104–111. doi: 10.1027/0227-5910/a000359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO. Preventing suicide: A global imperative. WHO; Geneva, Switzerland: 2014. [Google Scholar]