Abstract

While the diversity of ‘southern seals’, or Monachinae, in the North Atlantic realm is currently limited to the Mediterranean monk seal, Monachus monachus, their diversity was much higher during the late Miocene and Pliocene. Although the fossil record of Monachinae from the North Atlantic is mainly composed of isolated specimens, many taxa have been erected on the basis of fragmentary and incomparable specimens. The humerus is commonly considered the most diagnostic postcranial bone. The research presented in this study limits the selection of type specimens for different fossil Monachinae to humeri and questions fossil taxa that have other types of bones as type specimens, such as for Terranectes parvus. In addition, it is essential that the humeri selected as type specimens are (almost) complete. This questions the validity of partial humeri selected as type specimens, such as for Terranectes magnus. This study revises Callophoca obscura, Homiphoca capensis and Pliophoca etrusca, all purportedly known from the Lee Creek Mine, Aurora, North Carolina, in addition to their respective type localities in Belgium, South Africa and Italy, respectively. C. obscura is retained as a monachine seal taxon that lived both on the east coast of North America and in the North Sea Basin. However, H. capensis from North America cannot be identified beyond the genus level, and specimens previously assigned to Pl. etrusca from North America clearly belong to different taxa. Indeed, we also present new material and describe two new genera of late Miocene and Pliocene Monachinae from the east coast of North America: Auroraphoca atlantica nov. gen. et nov. sp., and Virginiaphoca magurai nov. gen. et nov. sp. This suggests less faunal interchange of late Neogene Monachinae between the east and west coasts of the North Atlantic than previously expected.

Keywords: Neogene, biodiversity, North Atlantic, Phocidae, Monachinae

1. Introduction

Among the semi-aquatic carnivoran clade of Pinnipedia, the family of true seals, or Phocidae, are remarkable for their biogeography. Phocidae are usually subdivided into two subfamilies, the ‘southern seals’, or Monachinae; and the ‘northern seals’, or Phocinae, see [1]. This reflects the current biogeography of both subfamilies, in which extant Monachinae include the Caribbean, Hawaiian and Mediterranean monk seals, the elephant seals along the eastern shores of the Pacific Ocean, and the elephant seals, leopard seal (Hydrurga leptonyx de Blainville, 1820), Weddell seal (Leptonychotes weddellii Lesson, 1826), crabeater seal (Lobodon carcinophaga Hombron and Jacquinot, 1842) and Ross seal (Ommatophoca rossii Gray, 1844) in the Antarctic and sub-Antarctic waters, which all live southerly of the ‘northern’ Phocinae. Phocinae, on the other hand, are largely restricted to the North Atlantic and North Pacific oceans and the Arctic Ocean. However, the fossil record from the late Neogene shows that ‘southern seals’ were much more common and diverse in the North Atlantic realm than they are today [2–4].

Molecular evidence indicates that stem phocids diverged from other pinnipeds around 23 Ma, at the Oligocene–Miocene boundary, but crown phocids, comprising the two subfamilies Monachinae and Phocinae, diverge in the middle Miocene around 16 Ma [5]. Notwithstanding the molecular inferences, two Monachinae, Afrophoca libyca Koretsky and Domning, 2014 and Monotherium gaudini (Guiscardi, 1870), known only from cranial elements ([6,7]; L. Dewaele 2017, personal observation), are older than 16 Ma: Af. libyca from Libya is Burdigalian in age (early Miocene, ca 19 Ma) [6] and M. gaudini from Italy may range from the Chattian (late Oligocene) to the Aquitanian (early Miocene) ([8,9]; L. Dewaele 2017, personal observation); therefore, neither is within the scope of this study and they will not be discussed in this study. Throughout the middle and late Miocene and early Pliocene, phocid taxa underwent (at least) one dispersal event across the North Atlantic Ocean: Leptophoca proxima (Van Beneden, 1876) and Monotherium aberratum Van Beneden, 1876 from the early-to-middle Miocene and late Miocene, respectively, are known from both sides of the North Atlantic [10,11], and many of the extinct phocid taxa described from the late Miocene and early Pliocene of the southern North Sea Basin by Van Beneden [2,3] have also been identified in the early Pliocene of North Carolina, USA [4]. However, subtle differences between specimens identified as the same taxon from across the Atlantic have led authors to code them as separate operational taxonic units (OTUs) in phylogenetic analyses [12]. Moreover, not all extinct phocid species have been found on both sides of the Atlantic, notably the enigmatic Nanophoca vitulinoides (Van Beneden, 1871) from the southern North Sea Basin [13].

Therefore, a revision of the different phocid OTUs from the North Atlantic realm is required in order to obtain a more conclusive view on their diversity and palaeobiogeography. The abundance of monachines in the North Atlantic temperate latitudes during the late Miocene–early Pliocene is particularly interesting given that they are conspicuously absent from this region today; modern monachines are restricted to the Mediterranean and Caribbean seas, Hawaii and the eastern Pacific and Antarctic and sub-Antarctic waters (e.g. [1,14]).

In this study, we reassess the humeri of the three taxa of monachine seals from the Neogene of the North Atlantic realm: Callophoca obscura Van Beneden, 1876, Homiphoca capensis (Hendey and Repenning, 1972) and Pliophoca etrusca Tavani, 1941 [2–4,12,15]. Humeri are selected and considered for two reasons. First, humeri are considered the most diagnostic postcranial bones in Phocidae[16–18]. Given the overall scarcity of more diagnostic cranial specimens, a taxonomy based on the most complete humeri possible is required to properly identify and compare phocid taxa. Second, due to their robust nature, humeri are among the most commonly preserved fossil phocid bones [4]. This is clearly advantageous over using less diagnostic types of bone that are more rarely preserved in the fossil record.

Messiphoca mauretanica Muizon, 1981 from the Messinian (upper Miocene) of Algeria [19] and Terranectes spp. from the upper Miocene of Maryland, USA [20] have formerly been identified as Monachinae from the North Atlantic realm, with a known humerus, but they are problematic for various reasons. M. mauretanica is represented by an associated left humerus, left ulna, left radius and six dorsal vertebrae (MNHN.F.ORN1, holotype) [19]. An isolated partial cranium (MNHN.F.ORN2, paratype) has been described as well. To date, no other specimens of M. mauretanica are known. Given the overall relatively poor quality of the small fossil record of M. mauretanica, this taxon needs a formal revision, pending the discovery of more complete specimens, i.e. more complete humeri, prior to further research involving this taxon. Nevertheless, in this study, M. mauretanica will be considered for comparison purposes because of the association of multiple bones in the holotype (MNHN.F.ORN1).

The genus Terranectes Rahmat, Koretsky, Osborne, Alford, 2017 was recently described, based on isolated material from the Chesapeake Bay Area, Maryland, USA [20]. Issues regarding the incomparability of both species to each other and to other known taxa make comparison impossible. Rahmat et al. [20] invoke Koretsky's [16] ecomorphotype hypothesis to support the designation of isolated specimens of different types of bone to different taxa. Koretsky's [16] ecomorphotype hypothesis is constructed for mandibles, humeri and femora. Currently, this hypothesis has been inadequately tested to be considered as a diagnostic tool, especially with regard to postcranial bones other than humeri and femora, which have not been considered in the original study by Koretsky [16]. For Terranectes magnus Rahmat, Koretsky, Osborne, Alford, 2017, the holotype specimen CMM-V-4710, is a partial humerus. However, although humeri are usually considered the most diagnostic postcranial bones in Phocidae, the holotype specimen of T. magnus is very incomplete, inhibiting proper comparison with other taxa (see below). Therefore, we judge that there is no scientific basis to support the assumption that the isolated specimens of both T. magnus and Terranectes parvus Rahmat, Koretsky, Osborne, Alford, 2017 indeed belong to the same genus. Pending future discoveries, the genus Terranectes should be considered a nomen dubium.

We also present new fossil phocid material from the east coast of North America, dredged off the Nottoway River bed west of Franklin, Virginia, USA. Previous research showed that the Chowan River tributaries, including the Nottoway and Meherrin rivers yield a large number of vertebrate fossils, including the type and only known specimen from the inoid odontocete Meherrinia isoni Geisler, Godfrey, Lambert, 2012.

2. Method and materials

2.1. Nomenclature

To maintain consistency with recent publications on extinct Phocidae, we follow the nomenclature and terminology used by Dewaele et al. [11,13] for phocid humeral anatomy where possible, and otherwise follow that of Evans & Lahunta [21] for the domestic dog.

2.2. Institutional abbreviations

CMM, Calvert Marine Museum, Solomons, Maryland, USA; IRSNB, Institut Royal des Sciences Naturelles, Brussels, Belgium; MNHN, Muséum National d'Histoire Naturelle, Paris, France; MSNUP, Museo di Storia Naturale, Università di Pisa, Pisa, Italy; SAM, South African Museum, Iziko Museums of South Africa, Cape Town, South Africa; USNM, Department of Paleobiology, National Museum of Natural History, Washington, DC, USA.

2.3. Fossil specimen sample

This study includes all late Miocene–early Pliocene Monachinae from the North Atlantic realm that are known from substantial material in the fossil record: C. obscura, H. capensis and Pliophoca etrusca. Comparison material also includes other Neogene Monachinae Acrophoca longirostris Muizon, 1981, Australophoca changorum Valenzuela-Toro, Pyenson, Gutstein, Suárez, 2016, Piscophoca pacifica Muizon 1981 and Properitpychus argentinus (Ameghino, 1893), all from the Southern Hemisphere. These comparisons are based on personal observations (Ac. longirostris and Pi. pacifica) and bibliographic data (Ac. longirostris, Au. changorum, Pi. pacifica and Pr. argentinus) [22–24].

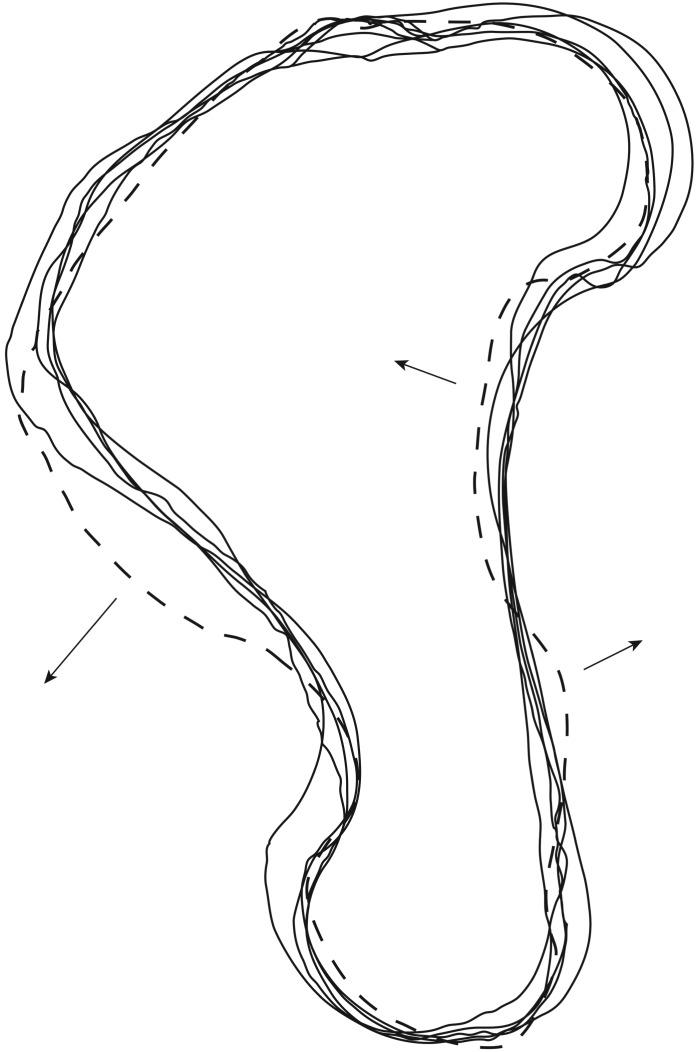

2.4. Intra- and interspecific long bone variation

Understanding intra- and interspecific variation in long bone shape among Monachinae is crucial to assess the degree of completeness required for an isolated fossil humerus to be considered diagnostic. A detailed study on intra- and interspecific monachine humerus shape is beyond the scope of this study. However, preliminary qualitative observations suggest that complete or nearly complete humeri can be treated as diagnostic bones to differentiate between different species of Monachinae. A very basic qualitative comparison of four humeri of (both sexes of) Hydrurga leptonyx and one humerus of Leptonychotes weddellii suggests that humeri are sufficiently diagnostic to distinguish taxa when complete (figure 1). This figure shows that the four complete humeri of H. leptonyx differ relatively little from one another, while the humerus of L. weddellii differs from the humeri of H. leptonyx on key morphological features, such as the curvature of the diaphysis and the morphology of the distal portion of the deltopectoral crest. However, the number of morphologically varying characters is limited, suggesting that complete or nearly complete humeri are required to differentiate between closely related species. All characters listed in the diagnoses of taxa below are considered to represent interspecific variation, intraspecific variation being discarded based on personal quantitative observations of extant Monachinae.

Figure 1.

Line drawings showing the basic morphological differences in the humeri of two different genera of extant Monachine. Five specimens of the leopard seal (Hydrurga leptonyx) indicated by full lines and one specimen of the Weddell seal (Leptonychotes weddellii) indicated by a dashed line. All specimens rescaled to the same proximodistal size. Arrows indicate the most important differences in the humerus between both genera.

3. Geological background and dinoflagellate cyst biostratigraphy

3.1. Callophoca obscura

Callophoca obscura is known from the ‘Scaldisian’ of the southern margin of the North Sea Basin, in Belgium, and of the Yorktown Formation in the Lee Creek Mine, Aurora, North Carolina, USA [2–4]. However, as mentioned above, the Scaldisian is currently considered an obsolete term and its use has been discontinued [25]. Different authors assign different ages and stratigraphic intervals to the Scaldisian ([25]: table 1), but in general, it is considered that the Scaldisian is roughly equivalent to the early Pliocene Kattendijk Formation [26–28]. However, many phocid fossils from the ‘Scaldisian’ show signs of reworking [13]. Most of the vertebrate remains recovered from the Kattendijk Formation come from the basal gravel [29], suggesting reworking of many of the specimens from the underlying Deurne Sands Member of the Diest Formation (late Miocene) or from the latest Miocene–earliest Pliocene depositional hiatus between the Diest and Kattendijk formations. The recent redescription of Nanophoca vitulinoides showed that this taxon actually lived during the Miocene and that most specimens of N. vitulinoides are Miocene in age but reworked into the early Pliocene basal gravel of the Kattendijk Formation [13]. Hence, the historical age determinations should be considered with care. For the Yorktown Formation, Ward & Blackwelder [30] state a Zanclean (early Pliocene) age for the formation in the Chesapeake Bay. Radiometric dating of the Rushmere Member, the second oldest member of the Yorktown Formation, returned an age of 4.4 ± 0.2 Ma [31]. They also considered the basal strata of the Yorktown Formation, the Sunken Meadow Member, equivalent to foraminiferal zone D18, with an onset at 5.0 Ma, unconformably overlying the 6.46 Ma upper strata of the Eastover Formation.

Table 1.

Measurements (in mm) of the holotype humeri of Auroraphoca atlantica and Virginiaphoca magurai. Measurements were taken to the nearest 0.1 mm using an analogous caliper. Measurement approach follows Koretsky [1].

| Auroraphoca atlantica | Virginiaphoca magurai | |

|---|---|---|

| USNM 181419 | USNM 639750 | |

| total length | 159.3 | 134.0 |

| length deltopectoral crest | 108.2 | 86.4 |

| height head | 38.9 | 28.9 |

| height trochlea | 22.1 | 18.9 |

| width head | 44.3 | 40.1 |

| width deltopectoral crest | 29.6 | 25.2 |

| width proximal epiphysis | 62.5 | 56.5 |

| width distal epiphysis | 66.6 | 54.8 |

| distal width trochlea | 39.6 | 34.2 |

| anterior width trochlea | 26.2 | 24.2 |

| transverse width mid-diaphysis | 28.5 | 24.6 |

| anteroposterior thickness proximal epiphysis | 74.0 | 61.4 |

| anteroposterior thickness medial condyle | 32.0 | 25.9 |

| anteroposterior thickness lateral condyle | 34.2 | 26.9 |

| diameter mid-diaphysis and deltopectoral crest in lateral view | 58.0 | 49.3 |

Two sediment samples (sample L15–1105 from the large (possible male) humerus of C. obscura, IRSNB M1156, originally described as Mesotaria ambigua Van Beneden, 1876 and sample L15–1108 from a small (possible female) humerus of C. obscura, IRSNB 1214) recovered from bone cavities were palynologically analysed for organic-walled dinoflagellate cysts (dinocysts) and acritarchs (electronic supplementary material). Unfortunately, the revision of C. obscura humeri proved that the latter specimen cannot be assigned to the species unambiguously. Both sediment samples return a Messinian age (latest Miocene), which can be regarded as a minimum age of the C. obscura specimens. However, because reworking of dinoflagellate cysts has been detected, it is impossible to elucidate an absolute age interval.

3.2. Homiphoca capensis

An age of 5.15 ± 0.1 Ma (earliest Zanclean, earliest Pliocene) had been proposed for the Langeberg quartzose sand and Muishond Fontein peletal phosphorite members of the South African Varswater Formation, containing virtually all South African Homiphoca capensis specimens ([32–34], and references therein). A number of phocid specimens from the Yorktown Formation at Lee Creek Mine, Aurora, North Carolina have been assigned to H. capensis [4], despite the strong geographical distance between the east coast of North America and the only other known (type) locality of H. capensis, the ‘E’ Quarry at Langebaanweg, northwest of Cape Town, South Africa. Others (C. de Muizon 2017, personal communication) disagree with the identification of H. capensis from North America. Nevertheless, the age of the Yorktown Formation roughly corresponds with the Langeberg Quartzose Sand Member (LQSM) and the Muishond Fontein Peletal Phosphorite Member (MPPM) from South Africa. The latter centre around 5.15 Ma [34], while Ward & Blackwelder [30] show that the basal Sunken Meadow Member of the Yorktown Formation has been dated to 5.0 Ma using foraminifera biostratigraphy, and Akers [31] presented a radiometrically measured age of 4.4 ± 0.2 Ma for the overlying Rushmere Member of the Yorktown Formation. Despite the difference, LQSM, MPPM and the Yorktown Formation are entirely Zanclean in age.

3.3. Pliophoca etrusca

From Italy, only the type specimen of Pliophoca etrusca is known. Tavani [35] assigned multiple other isolated and associated bones to Pl. etrusca, but Berta et al. [12] attributed these to Pliophoca cf. Pl. etrusca. A Piacenzian age (late Pliocene) has been assigned to the holotype skeleton: the layer of the Pliocene Argille Azzurre Formation it came from has been dated to 3.19–2.82 Ma [12,36]. The geological and historical background of the North American specimens of ‘Pliophoca etrusca’ is identical to the background of the North American specimens of H. capensis: Pl. etrusca from North America is only known from the Yorktown Formation at the Lee Creek Mine, which had been dated to the Zanclean (early Pliocene) (see above).

3.4. Auroraphoca atlantica nov. gen. et nov. sp.

Two humeri that were previously assigned to Pliophoca etrusca from North America (USNM 181419 and USNM 250290) [4] have both been recovered from the Lee Creek Mine in Aurora, Beaufort County, North Carolina. As has been noted above, the fossiliferous stratum at the Lee Creek Mine is the early Pliocene Yorktown Formation, with the basal Sunken Meadow Member corresponding with the 5.0 Ma foraminiferal zone D18 and the overlying Rushmere Member radiometrically dated to 4.4 ± 0.2 Ma [30,31] (see above).

3.5. Virginiaphoca magurai nov. gen. et nov. sp.

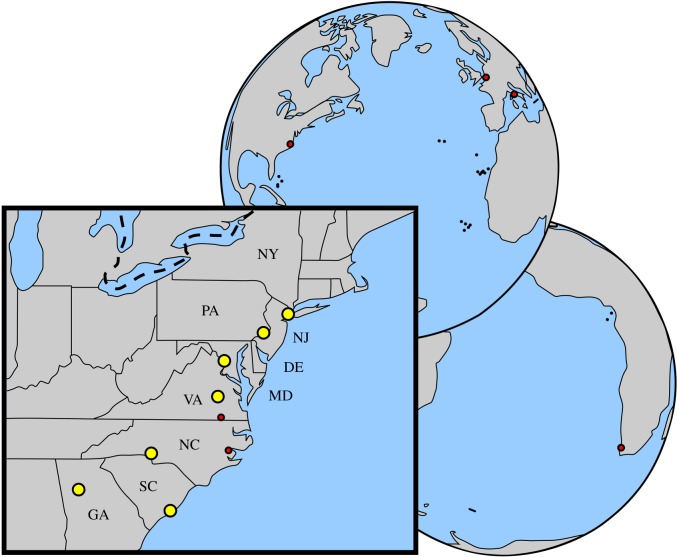

One newly described humerus (USNM 639750) that has been dredged off the Nottoway River bed at Franklin, Virginia, is assigned to the new taxon Virginiaphoca magurai. The holotype and only known specimen, humerus USNM 639750, was found ex situ by Joseph Magura and was ‘clean’, i.e. no original sediment had been attached to the specimens that could be used in elucidating its lithostratigraphic or biostratigraphic origin. However, the specimen shows only few signs of rolling, and hence, fluviatile transport of the specimen must have been limited. The possible stratigraphic provenance covers the upper Miocene Cobham Bay Member (CBM) of the Eastover Formation and the lower Pliocene Yorktown Formation (figure 2), because both outcrop in the river banks and riverbed of the Nottoway River in the Franklin area [30]. A similar strategy had been employed to ‘date’ the fossils of the river dolphin Meherrinia isoni from the nearby Meherrin River in North Carolina [37]. The Yorktown Formation is dated to the Zanclean [30]. Ward & Blackwelder [30] also presented an age of 8.7 ± 0.4 Ma for the lower levels of the CBM, and 6.46 ± 0.15 Ma for subsurface sampling of this member, based on radiometric dating of glauconite. Hence, the CBM is of late Tortonian to Messinian age (late Miocene). Although colour of a fossil bone is only a weak basis to support correlation with a given stratum, specimen USNM 639750 is dark grey with orange stains. And while the majority of the bones from the Yorktown Formation in the Lee Creek Mine are more yellow to beige in colour, Ward & Blackwelder [30, p. 20] argue that the CBM is ‘Grayish blue (5 PB 5/2) where fresh, the Cobham Bay sediments weather to a yellowish orange (10 YR 8/6).’ This description of the colour of the CBM corresponds with the observed colour pattern of specimen USNM 639750. Currently, no specimens that have been recovered from the Yorktown Formation at the Lee Creek Mine can be attributed to V. magurai. Although the latter does not prove the absence of the species throughout the entire Yorktown Formation elsewhere, it supports the claim that the CBM is the more likely origin of the type specimen.

Figure 2.

Map showing the geographical distribution of all Monachinae covered in this study. Localities are indicated by red dots: Callophoca obscura from Belgium, Pliophoca etrusca from Italy, Homiphoca sp. in South Africa; Auroraphoca atlantica nov. gen. et nov. sp., C. obscura and Homiphoca sp. in Aurora, North Carolina and V. magurai nov. gen. et nov. sp. near Franklin, Virginia. DE, Delaware; GA, Georgia; MD, Maryland; NC, North Carolina; NJ, New Jersey; NY, New York; PA, Pennsylvania; SC, South Carolina; VA, Virginia. Dashed line indicates border between Canada and the United States of America. Yellow dots indicate major cities (from east to west: Atlanta, Georgia; Raleigh, North Carolina; Charleston, South Carolina; Charlotte, Virginia; Washington, DC; Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; New York, New York).

Systematic palaeontology

Phocidae Gray, 1821

Monachinae Gray, 1869

Genus Callophoca Van Beneden, 1876

Type and only included species. Callophoca obscura Van Beneden, 1876

Diagnosis. As for the species.

Callophoca obscura Van Beneden, 1876

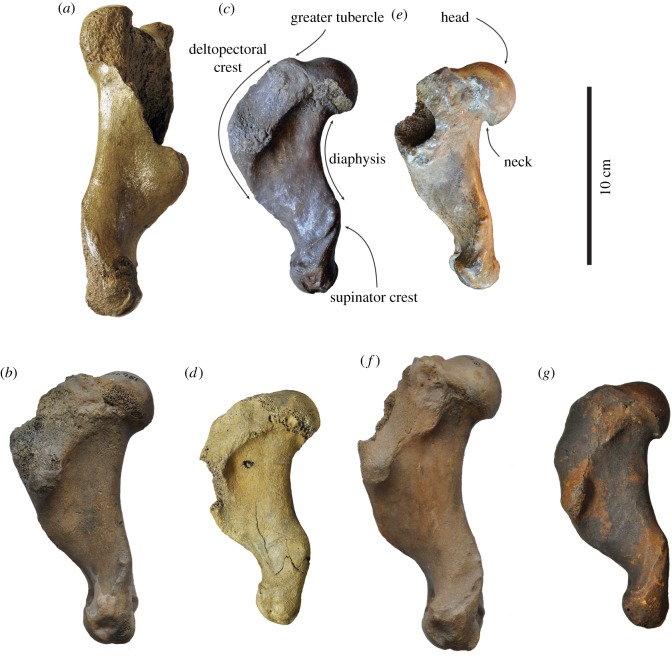

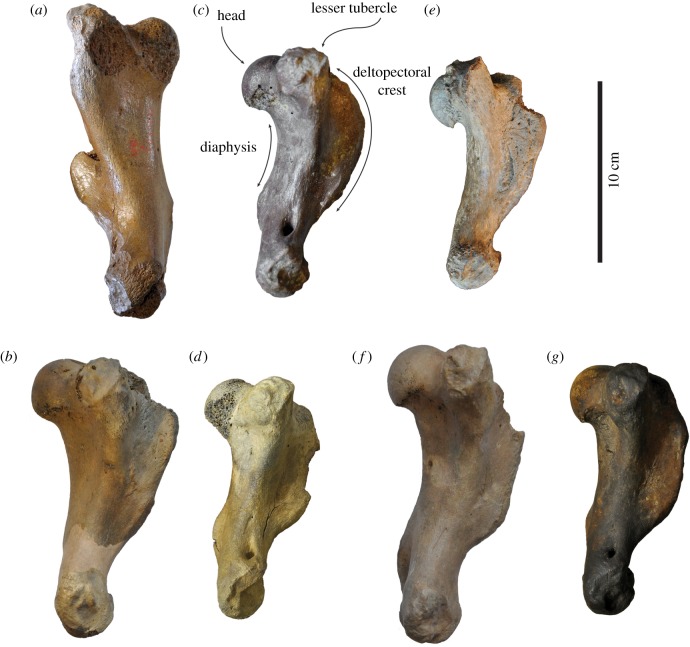

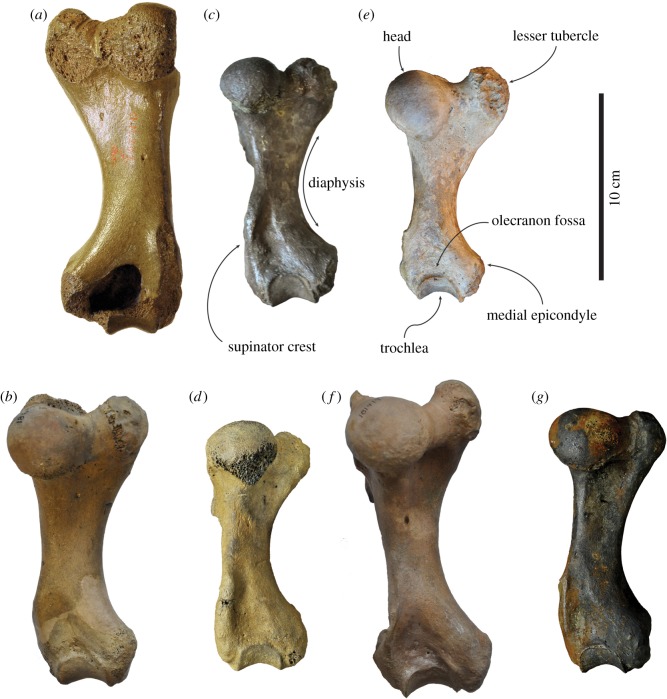

(figures 3a,b, 4a,b, 5a,b and 6a,b)

Figure 3.

Comparison of humeri in lateral view. Right lectotype humerus IRSNB 1156-M177 (a), and left humerus USNM 186944 (b), of Callophoca obscura from Antwerp, Belgium, and the Lee Creek Mine, Aurora, North Carolina, respectively; uncatalogued left humerus (c) and left humerus USNM 187228 (d) of Homiphoca sp. from Langebaanweg, South Africa (c), and the Lee Creek Mine, Aurora, North Carolina (d); left holotype humerus MSNUP I-13993 (e) of Pliophoca etrusca from Tuscany, Italy; left holotype humerus USNM 181419 (f) of Auroraphoca atlantica from Lee Creek Mine, Aurora, North Carolina; and left holotype humerus USNM 639750 (g) of Virginiaphoca magurai dredged from the Nottoway River west of Franklin, Virginia. (b) and (d) have been illustrated by Koretsky & Ray [4]. Scale bar equals 10 cm. Image courtesy for Pl. etrusca: G Bianucci.

Figure 4.

Comparison of humeri in anterior view. Right lectotype humerus IRSNB 1156-M177 (a), and left humerus USNM 186944 (b), of Callophoca obscura from Antwerp, Belgium, and the Lee Creek Mine, Aurora, North Carolina, respectively; uncatalogued left humerus (c) and left humerus USNM 187228 (d) of Homiphoca sp. from Langebaanweg, South Africa (c) and the Lee Creek Mine, Aurora, North Carolina (d); left holotype humerus MSNUP I-13993 (e) of Pliophoca etrusca from Tuscany, Italy; left holotype humerus USNM 181419 (f) of Auroraphoca atlantica from Lee Creek Mine, Aurora, North Carolina; and left holotype humerus USNM 639750 (g) of Virginiaphoca magurai dredged from the Nottoway River west of Franklin, Virginia. (b) and (d) have been illustrated by Koretsky & Ray [4]. Scale bar equals 10 cm. Image courtesy for Pl. etrusca: G Bianucci.

Figure 5.

Comparison of humeri in medial view. Right lectotype humerus IRSNB 1156-M177 (a), and left humerus USNM 186944 (b), of Callophoca obscura from Antwerp, Belgium, and the Lee Creek Mine, Aurora, North Carolina, respectively; uncatalogued left humerus (c) and left humerus USNM 187228 (d) of Homiphoca sp. from Langebaanweg, South Africa (c), and the Lee Creek Mine, Aurora, North Carolina (d); left holotype humerus MSNUP I-13993 (e) of Pliophoca etrusca from Tuscany, Italy; left holotype humerus USNM 181419 (f) of Auroraphoca atlantica from Lee Creek Mine, Aurora, North Carolina; and left holotype humerus USNM 639750 (g) of Virginiaphoca magurai dredged from the Nottoway River west of Franklin, Virginia. (b) and (d) have been illustrated by Koretsky & Ray [4]. Scale bar equals 10 cm. Image courtesy for Pl. etrusca: G Bianucci.

Figure 6.

Comparison of humeri in posterior view. Right lectotype humerus IRSNB 1156-M177 (a), and left humerus USNM 186944 (b), of Callophoca obscura from Antwerp, Belgium, and the Lee Creek Mine, Aurora, North Carolina, respectively; uncatalogued left humerus (c) and left humerus USNM 187228 (d) of Homiphoca sp. from Langebaanweg, South Africa (c), and the Lee Creek Mine, Aurora, North Carolina (d); left holotype humerus MSNUP I-13993 (e) of Pliophoca etrusca from Tuscany, Italy; left holotype humerus USNM 181419 (f) of Auroraphoca atlantica from Lee Creek Mine, Aurora, North Carolina; and left holotype humerus USNM 639750 (g) of Virginiaphoca magurai dredged from the Nottoway River west of Franklin, Virginia. (b) and (d) have been illustrated by Koretsky & Ray [4]. Scale bar equals 10 cm. Image courtesy for Pl. etrusca: G Bianucci.

Synonyms. Mesotaria ambigua Van Beneden, 1876; Phoca (Callophoca) obscura Trouessart, 1897.

Emended diagnosis. Large monachine seal, comparable in size to Hydrurga leptonyx (2.8–3.6 m). Callophoca obscura differs from other extinct Monachinae by the presence of a lesser tubercle that exceeds the proximal level of the humeral head (except Virginiaphoca magurai, newly described taxon in this study), and a deltopectoral crest that is both broad and subtriangular in lateral view. Differs from all extant Monachinae by the smaller anterior projection of the deltopectoral crest and less curving distal termination of the deltopectoral crest. Additionally differs from H. leptonyx and Leptonychotes weddellii by the presence of a bicipital groove.

Lectotype. IRSNB 1198-M203, partial right humerus, ‘Scaldisian’ from the ‘third section’ at Deurne, Antwerp, Belgium. Ilustrated by Van Beneden ([3]: pl. 11, figs 1–4). Lectotype selected by Koretsky & Ray [4].

Type locality and age. Third section at Deurne, Antwerp, Belgium. The ‘third section’ follows Van Beneden's discretization of the nineteenth-century fortification constructions around the city of Antwerp, with the third section at Deurne being located southwest to the Deurne district of Antwerp ([8]: fig. 1) [3,38]. However, it should be noted that this type locality is derived from the original labels associated with the specimen. In his original publications Van Beneden [2,3] did not discuss the geographical provenance of individual specimens of the original fossil record of C. obscura.

V. Beneden (1877, unpublished data) assigned the specimen IRSNB 1198-M203 to the ‘Scaldisien’ (Scaldisian). However, as mentioned above, the Scaldisian is currently considered an obsolete term and the name is no longer used [25]. In addition, many of the apparently Scaldisian phocid remains show signs of reworking and for Nanophoca vitulinoides it has already been shown that the actual fossil record is older than the Pliocene range that is commonly accepted for Scaldisian phocids ([13] contra [4]). Indeed, dinoflagellate cyst biostratigraphy of sediment sample associated with C. obscura (specimen IRSNB 1156-M177) suggests a Messinian age for the sediment sample, thus most likely adjusting the known stratigraphic age for the lectotype of C. obscura from the early Pliocene to the late Miocene (electronic supplementary material).

Other referred specimens. IRSNB 1116-M188. Partial right juvenile humerus missing the proximal epiphysis, from the ‘Scaldisian’ of the ‘third section’ at Deurne, Antwerp, Belgium (originally illustrated as Paleophoca nystii by Van Beneden ([3]: pl. 10, figs 10–13). IRSNB 1156-M177. Partial right humerus, from the ‘Scaldisian’ of the ‘third section’ at Borgerhout, Antwerp, Belgium (illustrated as Mesotaria ambigua by Van Beneden ([3]: pl. 9, figs 9–11). IRSNB VERT-17172-301b. Complete left humerus, from an unknown stratigraphic position at Deurne, Antwerp, Belgium. USNM 186944. Incomplete left humerus, from the early Pliocene Yorktown Formation at the Lee Creek Mine, Aurora, Beaufort County, North Carolina (illustrated by Koretsky & Ray [4]: figs 24E, 25E, 26E, 27E).

Comments. Historically, Callophoca obscura is a very well-known phocid from the southern margin of the North Sea Basin (i.e. Belgium) and the Lee Creek Mine from North Carolina, USA, yielding well over one thousand isolated bones of the North Atlantic Ocean, including a rare partial cranium from North America (USNM 475486) (e.g. [2–4]; C.M. Peredo and L. Dewaele 2017, personal observation). As a result, C. obscura has been considered in many phylogenetic analyses of Phocidae, and Monachinae in particular (e.g. [12,16,39–42]). However, all specimens that have diagnostic value (i.e. cranium, humeri, femora) have been found isolated, and only humeri can be compared with the lectotype humerus. All other types of bones have only tentatively been assigned to C. obscura in the past on the basis of the size of the specimens and the relative abundances in collections (e.g. [3,4]). Although it is likely that most of these specimens indeed belong to C. obscura, we invoke a conservative approach and reassign all non-humerus specimens from C. obscura as Monachinae indet. An individual reassessment of all specimens is beyond the scope of this study and we limit our research to the humeri of the species.

Koretsky & Ray [4] synonymized Callophoca obscura and Mesotaria ambigua because they observed no anatomical differences other than size, arguing that size difference alone represents sexual dimorphism: the smaller C. obscura are proposed to represent females whereas the larger M. ambigua would represent males of the same species. Apart from M. ambigua, Koretsky & Ray [4] also considered Paleophoca nystii Van Beneden, 1876 (and alternative spellings, including Monachus (Pristiphoca) nystii Trouessart, 1897; Palaeophoca nystii Hendey, 1972; Paläophoca nystii Toula 1897; Palaeophoca nysti Allen, 1880; Paloeophoca nysti Allen, 1880; Phoca Nystii Gervais, 1872; Poleophoca nystii Van Beneden, 1876) a junior synonym to C. obscura. Many of the postcranial specimens that have formerly been assigned to Pa. nystii are notably similar to the postcranial bones of C. obscura. However, the holotype of Pa. nystii is an isolated tooth [4,43] that has later been reassigned to the odontocete cetacean Scaldicetus grandis (du Bus, 1872) [4]. Later, Bianucci & Landini [44] questioned the validity of S. grandis, restricting the taxon to its non-diagnostic holotype. Therefore, Pa. nystii cannot technically be considered a synonym to either C. obscura or S. grandis.

Considering the material from the east coast of North America, most of the humeri which have been assigned to Pliophoca etrusca by Koretsky & Ray [4] seem to belong to C. obscura. In addition, Berta et al. [12] noted marked differences between collections from the Eastern and Western Atlantic, considering C. obscura a nomen dubium because the taxon is based on isolated specimens, which they deemed dubious for reliable taxonomy.

Description and comparison

Humerus. Because the lectotype of Callophoca obscura is an isolated partial humerus (IRSNB 1198-M203), other humeri are the only bones that can unambiguously be compared and assigned to C. obscura (figures 3a,b, 4a,b, 5a,b and 6a,b). Four isolated humeri from Belgium and a few tens of specimens from the east coast of North America can be assigned to the taxon. The humeral head is slightly compressed proximodistally, as stated by Koretsky & Ray [4], and the head faces proximoposteriorly, while it projects more posteriorly in Pliophoca etrusca. The humeral neck is poorly developed in C. obscura, while it is much more prominent in the holotype of Pl. etrusca and strongly overhangs the diaphysis posteriorly. The lesser tubercle reaches proximal to the level of the humeral head. This strongly resembles extant Phocidae (except Monachus) which all have a strongly developed lesser tubercle, reaching higher than the level of the humeral head, while other late Neogene Monachinae (e.g. Acrophoca longirostris, Homiphoca capensis, Piscophoca pacifica and Pl. etrusca) all tend to have a lesser tubercle that approximately reaches the same level as the humeral head, or distal to it (e.g. [12,22,23,32,34]). The greater tubercle is also well-developed, reaching the proximal level of the humeral head. A similar condition has been observed in the Neogene Monachinae Ac. longirostris, Auroraphoca atlantica (newly described taxon in this study), H. capensis and Pi. pacifica, in which the greater tubercle reaches the same proximal level as the humeral head, or exceeds it. This contrasts with other Monachinae in which the greater tubercle does not reach the proximal level of the humeral head [22–24].

The deltopectoral crest is poorly preserved in the lectotype humerus IRSNB 1198-M203 of C. obscura, but it is preserved in North American specimens. It is separated from the lesser tubercle by a wide and deep intertubercular groove. In the intertubercular groove, a distinct transverse bicipital bar is present, as in most Monachinae, except the extant Hydrurga leptonyx, Leptonychotes weddellii and the extinct Ac. longirostris, Homiphoca sp., and the newly described Virginiaphoca magurai [22,32]. The deltopectoral crest of C. obscura differs from that in other Monachinae in that it is both broad (contra other extinct Monachinae) and rounded triangular (contra extant Monachinae) in lateral view ([24]: fig. 4). As in other Monachinae, the deltopectoral crest of C. obscura is rounded and distally terminates smoothly just proximal to the coronoid fossa (compare [24]: fig. 4). In lateral view, the deltopectoral crest is widest proximally. The deltoid tuberosity is strongly pronounced on the lateral side of the deltopectoral crest and located just proximal to the middle of the bone. In anterior view, the deltopectoral crest is slightly curving laterally and slightly offset laterally, as in Homiphoca, while it is straight in Pl. etrusca. In lateral view, the deltopectoral crest of C. obscura is uniquely broad yet subtriangular; and diaphysis has only a minor curvature. Extant Monachinae all have a diaphysis with strong curvature, while many extinct Monachinae retain a straighter diaphysis, such as Ac. longirostris, Pi. pacifica and Pl. etrusca. Yet, a number of extinct Monachinae, including Homiphoca and Properiptychus argentinus have a rather strongly curving diaphysis [12,15,22,23,32,45].

At the distal extremity of the humerus of C. obscura, the coronoid fossa on the anterior side is weakly developed, as is the olecranon fossa on the posterior side. The supinator crest on the lateral epicondyle is only little developed, which is a typical monachine trait. The medial epicondyle is better developed and appears as a rounded obtuse triangle in anterior view. Callophoca obscura lacks an entepicondylar foramen, similar to all other Monachinae, except Homiphoca and V. magurai nov. gen. et nov. sp. At the trochlear notch, the anterior margin of the radial head strongly slopes distolaterally, as in Homiphoca. In Pliophoca etrusca, this margin is more proximally convex.

Homiphoca Muizon and Hendey, 1980

Type and only included species. Homiphoca capensis (Hendey and Repenning, 1972)

Diagnosis. As for the species.

Homiphoca capensis (Hendey and Repenning, 1972)

(figures 3c,d, 4c,d, 5c,d, 6c,d)

Synonyms. Prionodelpis capensis Hendey and Repenning, 1972

Diagnosis. As presented by Muizon & Hendey [32, pp. 94–96]: ‘A monachine phocid with a skull superficially similar to that of Monachus. It differs from Monachus in having a relatively large rostrum, which is wide posteriorly and narrow anteriorly. As in Monachus, but unlike Lobodontini, the premaxillae terminate against the nasals, where they are anteroposteriorly elongated. The premaxillae have prominent tuberosities anteriorly. The ascending process of the maxilla is relatively high as in Lobodontini and, viewed anteriorly, is not strongly recurved medially as in Monachus. Dental formula: 2.1.4.1/2.1.4.1. The premolars are morphologically similar to those of Monachus and unlike those of Lobodontini. They differ from those of Monachus in being lower crowned, relatively narrow and in having a pronounced posterolingual expansion of the cingulum. The accessory cusps on the premolars are small but distinct, while the M1 usually lacks such cusps and is distinct in having a strongly recurved and sharp, pointed principal cusp. The M1 is the largest of the cheek teeth, with the principal cusp slanted posteriorly, and often with a small accessory cusp low on the long anterior keel of the principal cusp. The interorbital region is broad and tapers posteriorly as in crabeater seal Lobodon carcinophaga, but unlike all other monachines. In the auditory region the tympanic bulla covers the petrosal, while the mastoid forms a lip overlapping the posterior border of the bulla.’

Holotype. SAM-PQ-L15695, incomplete and partially restored cranium, including left C and P4, and right P3, (illustrated as Prionodelphis capensis by Hendey & Repenning, ([45]: fig. 1); and as Homiphoca capensis by Govender et al. ([34]: fig. 2E, F) and Govender ([46]: figs 4, 8A]).

Type locality and age. ‘E’ Quarry, Langebaanweg, Cape Province, South Africa. Originally from ‘bed 2’ [45], reassigned to the Langeberg quartzose sand and Muishond Fontein peletal phosphorite members of the Varswater Formation, with an age of 5.15 ± 0.1 Ma (Zanclean, early Pliocene) [33].

Comments. Historically, Homiphoca capensis was represented by more than 3000 specimens from the ‘E’ Quarry, Langebaanweg, South Africa [32,34], and a handful of isolated specimens from the Lee Creek Mine in North Carolina [4]. Recent research of the Homiphoca material of the ‘E’ Quarry by Govender et al. [34] and Govender [46] showed the existence of at least two different morphotypes of Homiphoca in the fossil record. Govender et al. [34] presented two morphotypes of the cranium, scapula, humerus, radius, ulna, innominate, femur, and tibia and fibula; with morphological variation apparently exceeding that of intraspecific variation based on extrapolation of extant Monachinae. Later, Govender [46] performed a detailed analysis of the known crania of Homiphoca, confirming the presence of two (and possibly three) different morphotypes of Homiphoca crania.

Moreover, there is considerable disagreement on the possible existence of a yet-undescribed species of Homiphoca. Some researchers suggest that the observed morphological differences between the different morphotypes exceeds intraspecific variation [34,46], while others rather invoke profound sexual dimorphism and consider it unlikely for multiple closely related species to occupy the same ecological niche in the same environment and at the same time (C. de Muizon 2017, personal communication; L. Dewaele 2017, personal observation). Because the fossil record of Homiphoca consists of isolated crania, mandibles and postcranial bones, it is impossible to relate the holotype cranium to any of the isolated postcranial specimens, or to compare the different isolated postcranial bones reciprocally. Therefore, it is impossible to ascertain the correlation between the different morphotypes to different types of bones. Consequently, we judge it appropriate to consider the entire fossil record of Homiphoca with extreme care and only consider the holotype cranium SAM-PQ-L15695 to belong to H. capensis unquestionably. Following the reasoning for Callophoca obscura, all postcranial specimens of H. capensis should be considered as indeterminate monachine. However, the stratigraphy of Homiphoca from South Africa differs from C. obscura from the North Atlantic. Virtually all cranial and postcranial specimens attributed to H. capensis come from the LQSM and MPPM levels of the Varswater Formation in South Africa [32–34,46]. These levels have a very limited temporal range, and are virtually bonebeds. Hence, it can be argued as to what extent multiple closely related taxa can occupy the same ecological niche in the same area and at the same time. Furthermore, the high number of specimens found at Langebaanweg, the only known South African locality of Homiphoca renders it very likely that at least one of both morphotypes of humeri belongs to H. capensis. Therefore, it is safe to assume that all isolated seal specimens, which can be grouped into two morphotypes, may actually represent one sexually dimorphic taxon. But, pending the discovery of more complete articulated skeletons of H. capensis, we judge it most appropriate to consider specimens Homiphoca sp., rather than H. capensis or Monachinae indet. The stratigraphic range of C. obscura, on the other hand, is completely different in that the stratigraphic range of C. obscura from Belgium is poorly delineated and that the Yorktown Formation in North America had been deposited over a longer time span [30,47] with no clear fossiliferous horizon and most fossils recovered from spoil piles with no detailed stratigraphic context other than the formation [48]. The ‘H. capensis’ specimens of the Lee Creek Mine in North Carolina should conservatively be considered Homiphoca sp. as well (contra Koretsky & Ray [4]). A reassessment of the Homiphoca humeri from Koretsky & Ray [4] is presented below.

Homiphoca sp.

Locality. Lee Creek Mine, Aurora, Beaufort County, North Carolina, USA.

Stratigraphy and age. Yorktown Formation. Zanclean, lower Pliocene (see above; [30])

Referred specimen. USNM 187228, subcomplete right humerus, from the early Pliocene Yorktown Formation at the Lee Creek Mine, Aurora, Beaufort County, North Carolina (illustrated by Koretsky & Ray [4]: fig. 50E–H).

Comments. The holotype specimen of Homiphoca capensis, the sole species currently defined in the genus Homiphoca, is a partial cranium that has been found isolated [32,45]. Recent research by Govender et al. [34] and Govender [46] showed that virtually all cranial and postcranial specimens attributed to H. capensis have been found isolated and that at least two different morphotypes exist, hypothesizing the presence of at least a second species of Homiphoca. However, the presence of two closely related taxa in the same locality and occupying the same ecological niche is questionable, as noted above.

Description and comparison

Humerus. Koretsky & Ray [4] assigned two humeri from the Yorktown Formation at the Lee Creek Mine to Homiphoca capensis: USNM 187228 and USNM 214550 (figures 3c,d, 4c,d, 5c,d, 6c,d). However, the whereabouts of the latter specimen are unknown and the current study only focuses on specimen USNM 187228. The humeral head of Homiphoca specimen USNM 187228 from the east coast of North America faces proximoposteriorly, similar to Callophoca obscura and Homiphoca from South Africa. The neck is well developed and it is morphologically similar to that of Homiphoca from South Africa, but unlike that of C. obscura in which it is less developed, or Pliophoca etrusca in which it is also well developed but more strongly overhanging the diaphysis. The lesser tubercle of Homiphoca from North America reaches the proximal level of the humeral head, as in C. obscura, Homiphoca from South Africa, and Virginiaphoca magurai nov. gen. et nov. sp. (see below) from the Nottoway River, but unlike Pl. etrusca and Auroraphoca atlantica nov. gen. et nov. sp. (see below) previously considered Pl. etrusca from North America, which has a lesser tubercle that exceeds the level of the humeral head. A reduced lesser tubercle is considered a plesiomorphic trait among pinnipeds [22,49]. The lesser tubercle diverts strongly off the diaphysis. The greater tubercle does not reach the proximal level of the humeral head, which is considered a derived character in Phocidae, but appears to be present in all extant Phocidae and only some extinct Phocidae (see, e.g. Dewaele et al. [11,13]).

The deltopectoral crest is moderately well preserved in USNM 187228. It is separated from the lesser tubercle by a wide intertubercular groove. In the intertubercular groove, there is no transverse bicipital bar present. As mentioned above, such a bicipital bar is present in most Monachinae, except the extant Hydrurga leptonyx, Leptonychotes weddellii and the extinct Acrophoca longirostris, Homiphoca sp. from South Africa and V. magurai [22]. The deltopectoral crest of USNM 187228 is rounded and terminates distally proximal to the coronoid fossa. On the lateral side of the deltopectoral crest, the deltoid tuberosity overhangs the diaphysis, along the entire length of the tuberosity. This condition varies among Neogene Monachinae from the North Atlantic. In anterior view, the deltopectoral crest is slightly curving laterally and slightly offset laterally, as in C. obscura and Homiphoca from South Africa, while it is straight in Pliophoca etrusca. In lateral view, the diaphysis has a strong curvature, as in Homiphoca from South Africa and extant Monachinae. Many other extinct Monachinae retain a straighter diaphysis, such as Ac. longirostris, C. obscura, Piscophoca pacifica and Pl. etrusca [12,22].

At the distal extremity of the humerus of USNM 187228, the coronoid fossa on the anterior side is weakly developed, as is the olecranon fossa on the posterior side. The supinator crest on the lateral epicondyle is better developed than in other Monachinae, except Homiphoca from South Africa, and hence, also better than in C. obscura and Pl. etrusca. The medial epicondyle bears an entepicondylar foramen, which is a symplesiomorphic trait shared with Phocinae and other Pinnipedia, except Monachinae. Among Monachinae, the presence of an entepicondylar foramen is unique to Homiphoca and V. magurai nov. gen. et nov. sp. (USNM 639750, see below). Monotherium also has an entepicondylar foramen and has been considered a monachine [12,22], but the humeri of Monotherium aberratum and Monotherium affine Van Beneden, 1876 are considered to be phocine in a recent study by Dewaele et al. [50]. Overall morphology and the description of the Homiphoca specimens from the Lee Creek Mine, show noticeable similarities with the Homiphoca humeri from South Africa. The study of Govender et al. [34] shows relatively little difference between the two humerus morphotypes of Homiphoca from South Africa. Two of the most prominent differences observed are the degree of development and curvature of the deltopectoral crest and the shape of the deltoid tuberosity. The deltoid tuberosity is very incompletely preserved in specimen USNM 187228. The shape of the deltopectoral crest of USNM 187228 corresponds to that of morphotype I from South Africa, in which the deltopectoral crest ‘does not follow the curve of the bone’ [34, p. 142]. Overall, the humerus USNM 187228 is strongly similar to that of morphotype I of Homiphoca from South Africa, and differences are negligible. Therefore, it is indeed safe to consider Homiphoca sp. to be present in the Yorktown Formation of the east coast of North America.

Pliophoca Tavani, 1941

Type and only included species. Pliophoca etrusca Tavani, 1941

Diagnosis. As for the species.

Pliophoca etrusca Tavani, 1941

Emended diagnosis. We retain the holotype specimen, described by Tavani [15], and redescribed by Berta et al. [12] as the sole unquestionable specimen of Pliophoca etrusca. We only emend the part of the humerus in the diagnosis presented by Berta et al. [12] and exclude Leptophoca True, 1906 from the list of stem monachines, following recent recent phylogenetic analysis of the taxon by Dewaele et al. [11,13]: Pliophoca is distinguished from Monachus by medial tuberosity on premaxillary reduced or absent, lateral extension on premaxillary present, upper incisors transversely compressed, femur epiphyses in which the distal epiphysis is wider than the proximal epiphysis, greater trochanter of femur higher than the head, and calcaneum slightly longer than the astragalus. Pliophoca is distinguished from stem monachines (i.e. Acrophoca, ‘Callophoca’, Homiphoca and Piscophoca) by the following derived characters: humeral head strongly overhanging the humeral neck, supinator ridge on humerus absent or poorly developed and metacarpal I longer than metacarpal II. Pliophoca is distinguished from Mirounga and lobodontines in retention of the following primitive characters: medial tuberosity on the premaxillary reduced or absent, mastoid lip does not cover the external cochlear foramen, procumbent upper incisors absent and intercondylar region of femur narrow and deep.

Holotype. MSNUP I-13993, partial skeleton including the cranium (rostrum and fragmentary left half of the cranium); fragmentary cervical, thoracic, lumbar, sacral and caudal vertebrae; partial fore flippers (including a subcomplete left humerus, missing part of the deltopectoral crest) and partial hind flippers (illustrated as Pliophoca etrusca by Tavani ([15]: figs 1, 2, 10, 13, 20, 24) and Berta et al. ([12]: figs 2, 3A–C, 3F, 4–10).

Type locality and age. Casa Nuova, Orciano Pisano, Tuscany, Italy. Piacenzian (late Pliocene) layer of the Argille Azzurre Formation, dated at 3.19–2.82 Ma [36].

Comments. The holotype specimen MSNUP I-13993 is the only known specimen that can be attributed to the species Pliophoca etrusca [12]. However, this holotype is relatively complete, including a partial cranium, limb bones and vertebral bodies [12,15,35], making it one of the most completely known phocid fossils. Originally, Tavani [35] assigned additional material to the species: A fragment of a mandible from Orciano Pisano and specimens attributed to multiple individuals, including the left and right mandibles of a single individual and multiple other cranial, axial and appendicular bones from near Saline di Volterra, are housed at the Museo di Geologia e Paleontologia in Florence and were referred to Pl. etrusca by Tavani [35]. However, Berta et al. ([12]: e889144-16) approached the material more conservatively and only retained the holotype specimen as Pl. etrusca, arguing about the additional specimens that ‘most of it is from a different locality than the holotype and it consists, in part, of some noncomparable elements to the holotype (e.g. mandible), we feel that it is more appropriately referred to Pliophoca cf. Pl. etrusca’. In the current study, we encourage a more conservative approach in phocid palaeontology, advocating against the widespread practice of assigning isolated incomparable specimens to one or another taxon. Therefore, we support Berta et al. [12] in considering that it is not appropriate to consider the very partial specimens from the Museo di Geologia e Paleontologia in Florence as Pl. etrusca. In their review of Pliocene Phocidae from the east coast of North America, Koretsky & Ray [4] presented 171 specimens of Pl. etrusca from different localities in North Carolina and Florida: mostly isolated bones, but also including one associated scapula, humerus, radius and ulna (USNM 250290), and one associated humerus and femur (USNM 374222). Furthermore, this collection includes 16 maxillae, 8 isolated maxillary teeth, 44 mandibles, 18 isolated mandibular teeth, 35 humeri, 24 radii and 17 femora, based on the study by Koretsky & Ray [4]. However, these specimens show little similarities with the holotype from Italy, and are all reassigned to other taxa (see below) or as indeterminate Monachinae. This has also been postulated by Berta et al. [12], considering Koretsky & Ray's [4] allegedly North American specimens of Pl. etrusca as ‘Pliophoca aff. ‘Pl. etrusca’ USNM’.

Genus Auroraphoca nov. gen.

LSID. urn:lsid:zoobank.org:act:32C1A028-255C-4E3C-9F29-11A3CE7E5802

Type and only included species. Auroraphoca atlantica nov. gen. et nov. sp.

Etymology. From the toponym ‘Aurora’ and the Greek noun ‘phoke’. ‘Aurora’ is the town in Beaufort County, North Carolina where the Lee Creek Mine is located. The Yorktown Formation in the Lee Creek Mine is one of the most prolific fossil seal localities in the Northern Hemisphere [4] and is also the locality where the holotype of Auroraphoca atlantica was discovered. ‘Phoké’ means ‘seal’.

Diagnosis. As for the species.

Auroraphoca atlantica nov. gen. et nov. sp.

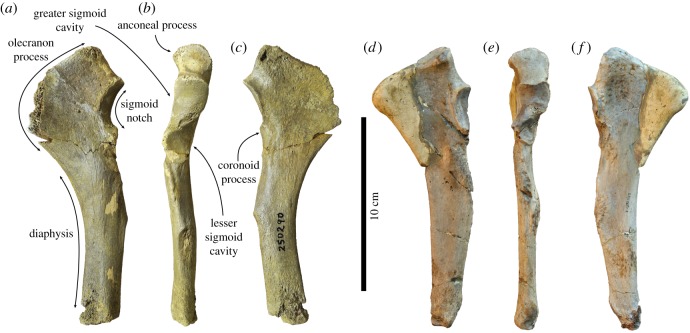

(figures 3f, 4f, 5f, 6f, 7a–c)

Figure 7.

Left ulna USNM 250290 of Auroraphoca atlantica in (a) medial, (b) anterior, and (c) lateral view, formerly considered to represent Pliophoca etrusca from the Lee Creek Mine, Aurora, Beaufort County, North Carolina, USA [4]. This specimen is considerably different from the holotype left ulna MSNUP I-13993 from Pl. etrusca of Italy, in (d) medial, (e) anterior and (f) lateral view. Note the incompleteness of the olecranon process in both specimens, which has been reconstructed in specimen MSNUP I-13993 (d,f). Scale bar equals 10 cm. Image courtesy for Pl. etrusca: G Bianucci.

LSID. urn:lsid:zoobank.org:act:1C376335-3827-4B67-BFE7-DE4A6B5CF443

Diagnosis. Auroraphoca atlantica is a medium-sized phocid, comparable in size to the extant Lobodon carcinophaga, different from other extant and other extinct Monachinae by the abrupt distal termination of the deltopectoral crest, and the presence of a reduced and distally located epicondylar crest. It differs from all extinct Monachinae (except C. obscura) by the strong development of the lesser tubercle, exceeding the proximal level of the humeral head, and from all extinct Monachinae (except Pliophoca etrusca) by the weak development of the anconeal process on the ulna.

Etymology. The specific name ‘atlantica’ refers to the Atlantic Ocean. The holotype specimen of Auroraphoca atlantica was recovered from the Yorktown Formation, deposited at the east coast of North America during the Pliocene.

Holotype. USNM 181419, incomplete left humerus, from the early Pliocene Yorktown Formation at the Lee Creek Mine, Aurora, Beaufort County, North Carolina (illustrated as Pliophoca etrusca by Koretsky & Ray ([4]: figs 24E, 25E, 26E, 27E).

Paratype. USNM 250290, articulated proximal portion of a left scapula, partial left humerus and left ulna, from the early Pliocene Yorktown Formation at the Lee Creek Mine, Aurora, Beaufort County, North Carolina (illustrated as Pliophoca etrusca by Koretsky & Ray [4] figs 44, 47).

Type locality. Lee Creek Mine, Aurora, Beaufort County, North Carolina, USA.

Type horizon. Yorktown Formation. Zanclean, lower Pliocene, based on foraminifer biostratigraphy [30].

Description and comparison

Scapula—One very incomplete scapula can be assigned to Auroraphoca atlantica. Of this bone, from specimen USNM 250290, only the proximal portion is preserved, but its identification as Au. atlantica is based on its articulation with a humerus that can be identified as Au. atlantica. The specimen is not described here because it is too incompletely preserved, rendering the significance of a description futile.

Humerus—Humeri USNM 181419 and USNM 250290 differ morphologically from both Callophocaobscura and Pliophoca etrusca, although Koretsky & Ray [4] formerly assigned both specimens to Pl. etrusca (figures 3f, 4f, 5f, 6f). Humerus USNM 181419 is nearly complete, missing only the anteroproximal portion of the deltopectoral crest. Humerus USNM 250290 is associated with a partial scapula and an ulna. This specimen is only partially preserved and is clearly not an adult, as can be judged from the clearly visible suture between the proximal epiphysis and the diaphysis. The humerus of Auroraphoca atlantica is overall relatively slender compared with other contemporaneous monachine humeri [4,12,15,32] (table 1). The humeral head is rounded, hemispherical and much smaller than in the holotype humerus of Pl. etrusca. The humeral head appears negligibly smaller than in other contemporaneous Monachinae from the North Atlantic and Homiphoca from South Africa. The greater tubercle extends proximally to the humeral head, and the lesser tubercle reaches proximal to both the humeral head and the greater trochanter. Among Monachinae, and Phocinae in general, the development of the lesser and great tubercles of the humerus show evolutionary trends [11,13,22]. Among Phocidae, the development of the greater and lesser trochanter shows opposite evolutionary trends, with the greater trochanter usually being well developed in extant Phocidae (except Monachus monachus), and less well developed in extinct Phocidae (except Callophoca obscura and Pl. etrusca) ([11,13]; this study). Dewaele et al. [11,13] and Muizon [22] noted the reverse for the development of the lesser tubercle of the humerus in Phocidae. The strong development of the lesser tubercle in the humerus of Au. atlantica corresponds more with extant Phocidae and C. obscura and Pl. etrusca than with most extinct Phocidae. A broad bicipital groove separates the lesser tubercle from the greater tubercle and the deltopectoral crest. In the intertubercular groove, there is a transverse bicipital bar. The deltopectoral crest extends for almost two-thirds along the anterior side of the diaphysis, terminating rather abruptly, distally. This abrupt distal termination separates the humerus of Au. atlantica from the humeri of extant and other extinct Monachinae, which all have a smooth and more gradual distal termination [49,51]. The deltoid tuberosity extends along the proximal two-thirds of the lateral side of the deltopectoral crest. This tuberosity overhangs the diaphysis laterally in two distinct places, anteriorly and posteriorly. This condition varies among different taxa of Monachinae from the Neogene of the North Atlantic. A similar condition to Au. atlantica is observed only in the newly described humerus USNM 639750 from Virginiaphoca magurai (see below). In anterior view, the deltopectoral crest of humerus USNM 181419 is slightly convex laterally, and the crest terminates above the coronoid process. The diaphysis of the humerus of Au. atlantica is slender compared with the humerus of other Monachinae from the Neogene of the North Atlantic. Proximally on the posterior surface of the diaphysis of the humerus there is a deep fossa serving as the attachment surface for the triceps brachii muscle. Among phocids, a similar condition has only been observed in Monotherium aberratum, Monotherium affine and Piscophoca pacifica ([22]; L. Dewaele 2017, personal observation).

In anterior view, the distal epiphysis of USNM 181419 is equally wide as the proximal epiphysis. This character is shared with Homiphoca and with the newly described humerus from the Nottoway River (see below). In C. obscura and Pl. etrusca, the proximal epiphysis is broader than the distal epiphysis. The medial epicondyle strongly reaches distally. The epicondylar crest is poorly developed, but forms a short and prominent protuberance distally, compared with the condition in other Monachinae, resulting in a strongly reduced attachment surface for multiple manual extensor muscles. This condition is unique in Phocidae. In extant Monachinae, Pl. etrusca, and V. magurai nov. gen. et nov. sp., the epicondylar crest is absent or poorly developed, while it is moderately well developed along the epicondyle in other extinct Monachinae [12,22]. There is no entepicondylar foramen, a synapomorphy among Monachinae. Among Phocidae, only the extinct monachines Homiphoca and Monotherium, and Phocinae have an entepicondylar foramen [2–4,22,32,45,49,51,52]. Correlated, the weak development of the epicondylar crest yields an apparently straighter humerus in lateral view than it does in Homiphoca or V. magurai nov. gen. et nov. sp. from the Nottoway River, but not as straight as in C. obscura or Pl. etrusca. The olecranon and coronoid fossae are strongly reduced, and the trochlea is small. The medial ulnar lip of the trochlea is well-developed, forming a sharp ridge, as in Pl. etrusca and V. magurai, but unlike C. obscura and Homiphoca.

Ulna—Contrasting to other types of bone, Koretsky & Ray [4] assigned only one ulna from North America to Pliophoca etrusca: USNM 250290, which is associated with a scapula and a humerus. In the current study, this specimen is reassigned to Auroraphoca atlantica (figure 7a–c). Although the proximal epiphysis of the specimen is fused to the diaphysis, the absence of the distal epiphysis argues that this specimen belonged to a skeletally subadult seal [23], as had been argued by Koretsky & Ray [4]. Although incomplete, the total length of ulna USNM 250290 of Au. atlantica falls near the estimated total length of 170 mm for the ulna of Homiphoca [22]. USNM 250290 is only slightly longer than the holotype ulna MSNUP I-13993 of Pl. etrusca, and the holotype MNHN.F.ORN1 of M. mauretanica, but still within the range of natural intraspecific variation (L. Dewaele 2017, personal observation). The state of preservation of the olecranon process in both USNM 250290 and Pl. etrusca specimen MSNUP I-13993 limits comparative description of the process. However, it appears that the olecranon process in USNM 250290 is more strongly sloping than in Homiphoca and Pl. etrusca. The proximal portion of the ulna of M. mauretanica is also strongly sloping, with a strongly concave proximal margin of the olecranon process [19]. The anconeal process on the medial side of the proximal portion of the olecranon process is weakly developed, as in Pl. etrusca. This condition had been considered a monachine trait by Hendey & Repenning [45] (except Piscophoca pacifica). The sigmoid notch is strongly concave, contrasting to Homiphoca, M. mauretanica and Pl. etrusca. Partly related to this strong curvature of the sigmoid notch in lateral view, the coronoid process of USNM 250290 is more strongly pronounced than in Homiphoca and Pl. etrusca. The greater sigmoid cavity is saddle-shaped and simple (reversed) tear-drop shaped in USNM 250290, while it is much more sigmoidal in the Pl. etrusca holotype MSNUP I-13993, in which the distal extremity of this cavity strongly deflects medially; and the lesser sigmoid cavity is circular and flat, while it is slightly concave in Pl. etrusca. Overall, the sigmoid notch of ulna USNM 250290 resembles that of M. mauretanica. However, comparison involved illustrations of M. mauretanica and no direct observations. Moreover, the limited diagnostic value of ulna for Phocidae precludes comparing USNM 250290 with M. mauretanica.

The diaphysis of the ulna USNM 250290 is robust and strongly curved. In lateral view, the diaphysis is thicker than in Homiphoca, M. mauretanica and Pl. etrusca. In anterior view, the diaphysis is approximately equal to the proximal portion of the coronoid process, in USNM 250290 and Homiphoca, while the proximal portion of the coronoid process is wider than the diaphysis in Pl. etrusca, and while the diaphysis is wider than the proximal portion of the coronoid process in M. mauretanica. In lateral view, the posterior margin of the diaphysis is strongly curving in USNM 250290, as in Homiphoca and M. mauretanica, but contrasting to Pl. etrusca, in which this margin is relatively straight.

Genus Virginiaphoca nov. gen.

LSID. urn:lsid:zoobank.org:act:C5C2FBDF-F501-4253-BAE1-F550BB5B7F4

Type and only included species. Virginiaphoca magurai nov. gen. et nov. sp.

Etymology. From the toponym ‘Virginia’ and the Greek noun ‘phoke’. ‘Virginia’ refers to the state of Virginia (United States of America), alluding to the locality of the holotype specimen being dredged off the riverbed of the Nottoway River near Franklin, Virginia. ‘Phoké’ means ‘seal’.

Diagnosis. As for the species.

Type locality and age. As for the species.

Virginiaphoca magurai nov. gen. et nov. sp.

LSID. urn:lsid:zoobank.org:act:8035E57E-F9D4-40B3-9771-AA4EF0DC8EEC

Diagnosis. Virginiaphoca magurai is a medium-sized phocid, comparable in size to the extant phocine Phoca vitulina (1.5–1.9 m). Virginiaphoca magurai is typically monachine in that the deltopectoral crest terminates smoothly distally, and differs from extant and other extinct Monachinae by the following characters: strong proximodistal compression of the humeral head (except Monachus spp., Ommatophoca rossii), a very reduced overhanging humeral neck, and the presence of an entepicondylar foramen (also present in H. capensis and Monotherium). Differs additionally from Homiphoca sp. by the reduction of the epicondylar crest.

Etymology. The specific name ‘magurai’ is a tribute to Joseph ‘Joe’ Magura who discovered the holotype specimen.

Holotype. USNM 639750, subcomplete left humerus from the Nottoway River, west of Franklin, Virginia, USA.

Type locality. Nottoway River, west of Franklin, Virginia, USA. Approximate coordinates: 36°40′ N, 77°01′ W.

Type horizon. Cobham Bay Member of the Eastover Formation, or the Yorktown Formation. The Cobham Bay Member of the Eastover Formation is radiometrically dated to the late Miocene. The Yorktown Formation is dated to the Zanclean, lower Pliocene, based on foraminifer biostratigraphy and radiometric dating [30,31].

Comments. In addition to humerus USNM 639750, other phocid specimens, including two complete femora (USNM 639748 and 639749), two radii (USNM 639751 and 639752), a tibia (USNM 639753), and two metatarsals (USNM 639754 and 639755), as well as terrestrial mammal vertebra (USNM 639756) have been dredged off the Nottoway River bed. These show a similar state of preservation with respect to completeness of the bone and color. However, a detailed description of the other phocid specimens is beyond the scope of the present study.

Description and comparison

Humerus—The left humerus USNM 639750 of Virginiaphoca magurai is completely preserved. The humerus is short and robust (table 1; figures 3g, 4g, 5g, 6g). The humeral head is hemispherical and slightly compressed proximodistally. The degree of proximodistal compression is higher than in other monachine humeri from the Neogene of the North Atlantic. The neck is strongly reduced, compared with other Monachinae from the North Atlantic, giving the entire humerus a moderately straight appearance in lateral view: straighter than in Homiphoca sp. from North America and South Africa, similarly straight as humerus USNM 181419 of Auroraphoca atlantica, but not as straight as in Callophoca obscura or Pliophoca etrusca. Extant Phocidae and other extinct Phocidae all have a relatively more curved humeral diaphysis in lateral view. The lesser tubercle almost reaches the same proximal level as the head and does not divert strongly medially from the axis of the humerus. In living monachines, except the monk seals of the genus Monachus, the lesser tubercle is strongly developed and exceeds the level of the humeral head. This condition varies among extinct Monachinae, with, e.g. C. obscura, Homiphoca sp. and Pl. etrusca having a well-developed lesser tubercle, while Acrophoca longirostris, Piscophoca pacifica and Properiptychus argentinus from South America all have a relatively small lesser tubercle ([22,51]; this study). The bicipital groove is moderately deep and wide. In the intertubercular groove, there is no transverse bicipital bar. The greater tubercle reaches slightly lower than the humeral head, as in extant Phocidae [22]. However, a number extinct monachine taxa have a greater tubercle that exceeds the level of the humeral head, including C. obscura and Homiphoca sp. (this study). The deltopectoral crest is long, approximately two-thirds the length of the entire bone and reaching the level of the proximal portion of the medial epicondyle. In lateral view, the humerus USNM 639750 of V. magurai is semicircular. This condition is roughly intermediate between the less expanded deltopectoral crest of Ac. longirostris, morphotype II in Homiphoca, Pl. etrusca and Pr. argentinus; and the deltopectoral crest of C. obscura, morphotype I of Homiphoca and Piscophoca pacifica (see [12,15,22,23,34]). The deltoid rugosity on the lateral surface of the deltopectoral crest is proximodistally elongated, widest proximally and tapering distally, and slightly overhanging the lateral surface of the deltopectoral crest in two separate places. The latter condition is observed in the humerus of Au. atlantica, but otherwise this varies among extinct Monachinae. In anterior view, the deltopectoral crest of V. magurai does not deflect as much laterally as it does in other Neogene Monachinae from the North Atlantic, except Pl. etrusca, and largely remains within the anteroposterior plane through the axis of the humerus. Among Monachinae, the presence of an entepicondylar foramen is a feature unique to the genus Homiphoca [22,32,45,49]. An entepicondylar foramen is also known to exist in Monotherium [22]. However, a study contesting Monotherium as a monachine genus is in review. However, it is also present in USNM 639750. The distal portion of the humerus of V. magurai does not differ significantly from that of Homiphoca, with a broad and little-developed medial epicondyle. The epicondylar crest is little developed, as is common in all extant Monachinae, Au. atlantica, and Pl. etrusca, while it is moderately developed in other extinct Monachinae [12,22]. As Berta et al. [12] observed in Pl. etrusca, V. magurai has a narrow but well-marked attachment surface for the m. extensor carpi radialis on the posterolateral margin of the epicondylar crest. This attachment surface appears less strongly developed in C. obscura and Homiphoca. The coronoid fossa is rather shallow and the roughly oval olecranon fossa is moderately deep. The shared presence of an entepicondylar foramen in V. magurai and Homiphoca sp. and the absence of a transverse bicipital bar in the intertubercular groove may suggest a phylogenetic relationship between both taxa. However, the incompleteness of the fossil record of V. magurai inhibits a detailed phylogenetic analysis.

Monachinae indet.

Locality. Lee Creek Mine, Aurora, Beaufort County, North Carolina, USA.

Stratigraphy and age. Yorktown Formation. Zanclean, lower Pliocene [30].

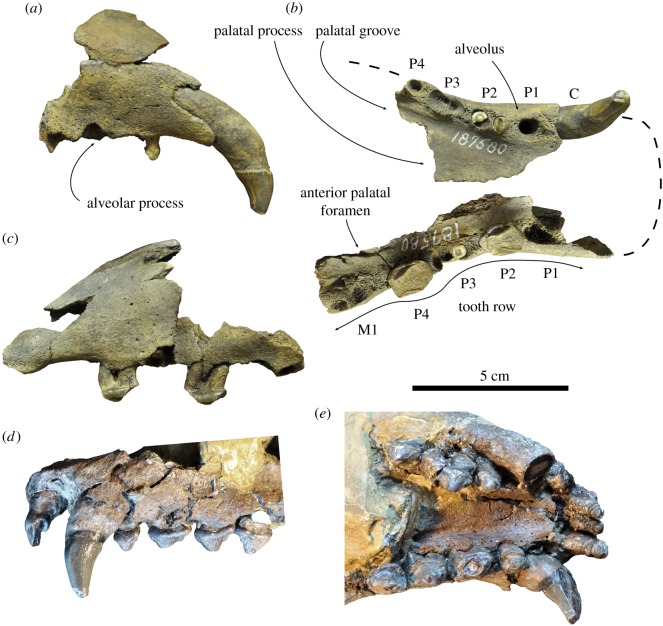

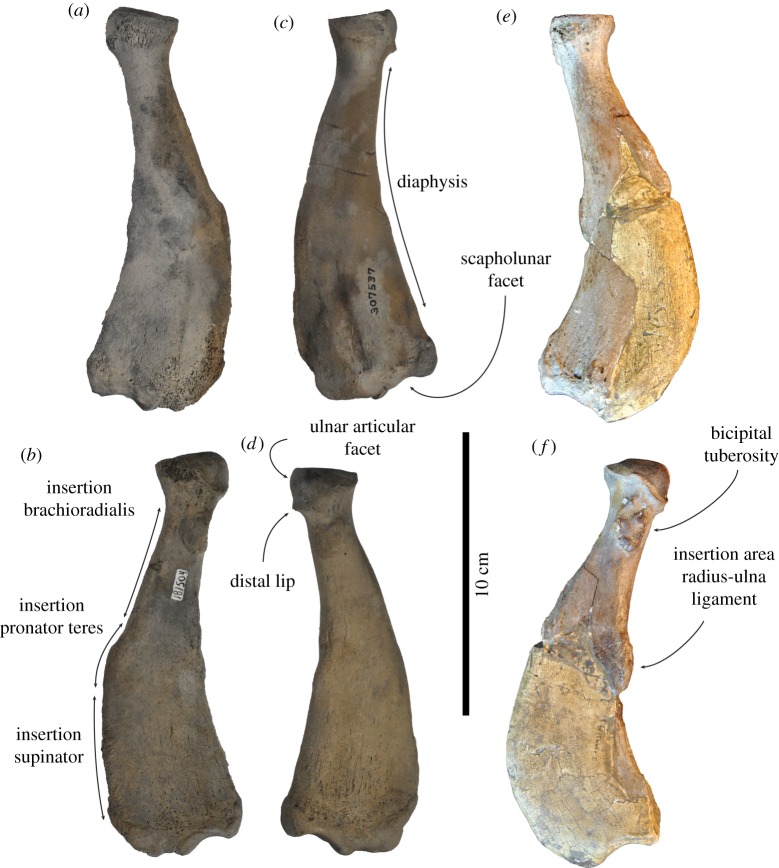

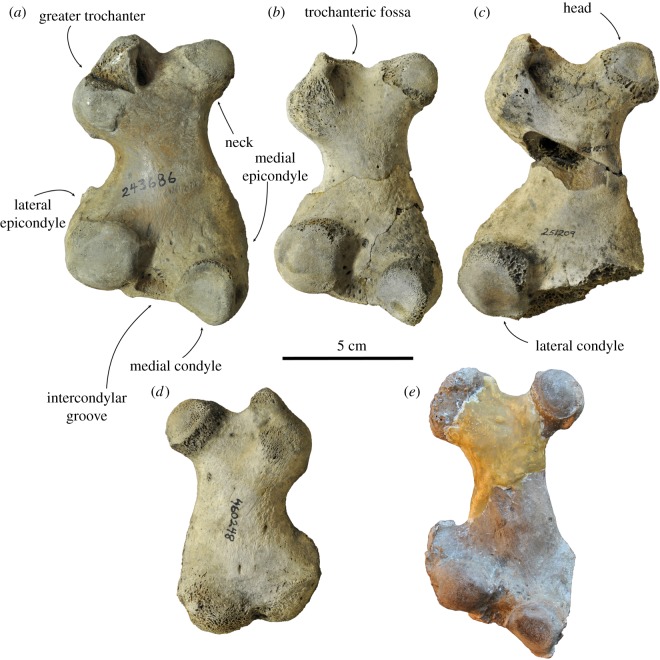

Referred specimens. USNM 187580. Partial maxillae, from the early Pliocene Yorktown Formation at the Lee Creek Mine, Aurora, Beaufort County, North Carolina, USA (illustrated as Pliophoca etrusca by Koretsky & Ray [4]: fig. 41A, E). USNM 181504. Right radius, from the early Pliocene Yorktown Formation at the Lee Creek Mine, Aurora, Beaufort County, North Carolina (= Pliophoca etrusca Koretsky & Ray [4]). USNM 307537. Left radius, from the early Pliocene Yorktown Formation at the Lee Creek Mine, Aurora, Beaufort County, North Carolina (illustrated as Pliophoca etrusca by Koretsky & Ray [4]: fig. 46). USNM 243686. Left femur, from the early Pliocene Yorktown Formation at the Lee Creek Mine, Aurora, Beaufort County, North Carolina (= Pliophoca etrusca Koretsky & Ray [4]). USNM 250293. Left femur, from the early Pliocene Yorktown Formation at the Lee Creek Mine, Aurora, Beaufort County, North Carolina (= Pliophoca etrusca Koretsky & Ray [4]). USNM 251209. Left femur, from the early Pliocene Yorktown Formation at the Lee Creek Mine, Aurora, Beaufort County, North Carolina (= Pliophoca etrusca Koretsky & Ray [4]). USNM 460248. Right femur, from the early Pliocene Yorktown Formation at the Lee Creek Mine, Aurora, Beaufort County, North Carolina (= Pliophoca etrusca Koretsky & Ray [4]).

Comments. Fossil phocid specimens that Koretsky & Ray [4] assigned to Pliophoca etrusca from North America are reconsidered in this study (see below). Our reassessment shows that some specimens are incomparable with the holotype (and currently only definitely known) specimen of Pl. etrusca, such as is the case for mandibles and the mandibular dentition ([4] versus [12]). Specimens from the Neogene of North America that are comparable with the Italian holotype of Pl. etrusca show noticeable differences with the holotype, despite the designation by Koretsky & Ray [4] (see below). Consequently, given the overall incompleteness of the fossil record of Monachinae from the North Atlantic, most of these redescribed specimens are to be considered Monachinae indet.

In the current study, we argue that only nearly complete or complete humeri should be used in the designation of new monachine taxa, in the absence of more complete and articulated specimens. Indeed, the Auroraphoca atlantica humerus USNM 250290 is articulated with a partial scapula and an ulna. However, the specimen is clearly juvenile, which we consider inappropriate for holotype designation.

Description and comparison

Maxilla and maxillary postcanines (figure 8a–c)—Koretsky & Ray [4] assigned 16 isolated maxillae, of which some include maxillary teeth, and eight isolated maxillary teeth from different localities in North Carolina and Florida to Pliophoca etrusca. For the original material of Pl. etrusca from Italy, i.e. the holotype, no mandibles or mandibular teeth are known [12]. In the absence of articulated specimens having both mandibles and mandibular teeth as well as bones that are comparable to the holotype specimen, it remains impossible to assign isolated mandibles and mandibular teeth to the taxon. The maxilla, on the other hand, is known from the holotype of Pl. etrusca and can be compared with specimens from North America; although they are very incomplete.

Figure 8.

Partial snout USNM 205397 of an indeterminate monachine seal in (a) right, (b) ventral, and (c) left view, formerly considered to represent Pliophoca etrusca from the Lee Creek Mine, Aurora, Beaufort County, North Carolina, USA [4]. The fractured holotype snout MSNUP I-13993 from Pl. etrusca of Italy, in (d) left and (e) ventral view. Scale bar equals 5 cm. Image courtesy for Pl. etrusca: G Bianucci.

The state of preservation of the referred and illustrated specimens from North America inhibits a detailed description. The postcanine tooth row is positioned on a lowly raised alveolar process. The postcanine tooth row is slightly diverging posteriorly, as in Homiphoca. However, the incomplete state of preservation of the holotype cranium of Pl. etrusca from Italy inhibits comparison between the referred specimens and the Pl. etrusca holotype. The alveoli for the maxillary teeth in specimen USNM 205397 show that P1 is single-rooted, while the other postcanine teeth are double-rooted. Spacing between the alveolus of P1 and C and P2 is large and shows the presence of a diastema.

On the ventral surface of maxilla USNM 205397, on the palatal process of the maxilla, there is a broad and shallow groove parallel and close to the tooth row. Posteriorly, this groove terminates into the anterior palatal foramen, located at the level between P4 and M1. This condition strongly differs from Homiphoca (narrow, deep groove and termination posterior to the anterior alveolus of M1) and from the holotype of Pl. etrusca (shallow groove terminating anterior at the level of the posterior alveolus of P3)

Consequently, although the maxillae are very incomplete, both for the referred specimens from North America and the holotype of Pl. etrusca, there are a few differences that set both operational taxonomic units (OTUs) apart from each other. We consider it more conservative to consider the referred specimens from North America as Monachinae indet.

Radius—Koretsky & Ray [4] assigned 24 radii from the east coast of North America to the species Pliophoca etrusca (figure 9a–d). One subadult specimen, USNM 250290 has been found associated with a scapula, a humerus and an ulna [4] (see above). However, the radii Koretsky & Ray [4] assigned to Pl. etrusca show marked differences with the Pl. etrusca holotype radius MSNUP I-13993.

Figure 9.

Right radius USNM 181504 in (a) lateral, and (b) medial view, left radius USNM 307537 in (c) lateral, and (d) medial view, and formerly considered to represent Pliophoca etrusca from the Lee Creek Mine, Aurora, Beaufort County, North Carolina, USA [4]. These specimens differ from the holotype left ulna MSNUP I-13993 from Pl. etrusca of Italy, in (e) lateral, and (f) medial view. Note the incompleteness of the radius of MSNUP I-13993 (e,f). Scale bar equals 10 cm. Image courtesy for Pl. etrusca: G Bianucci.