Abstract

Table olives are increasingly recognized as a vehicle as well as a source of probiotic bacteria, especially those fermented with traditional procedures based on the activity of indigenous microbial consortia, originating from local environments. In the present study, we report characterization at the species level of 49 Lactic Acid Bacteria (LAB) strains deriving from Nocellara del Belice table olives fermented with the Spanish or Castelvetrano methods, recently isolated in our previous work. Ribosomal 16S DNA analysis allowed identification of 4 Enterococcus gallinarum, 3 E. casseliflavus, 14 Leuconostoc mesenteroides, 19 Lactobacillus pentosus, 7 L. coryniformis, and 2 L. oligofermentans. The L. pentosus and L. coryniformis strains were subjected to further screening to evaluate their probiotic potential, using a combination of in vitro and in vivo approaches. The majority of them showed high survival rates under in vitro simulated gastro-intestinal conditions, and positive antimicrobial activity against Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium, Listeria monocytogenes and enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli (ETEC) pathogens. Evaluation of antibiotic resistance to ampicillin, tetracycline, chloramphenicol, or erythromycin was also performed for all selected strains. Three L. coryniformis strains were selected as very good performers in the initial in vitro testing screens, they were antibiotic susceptible, as well as capable of inhibiting pathogen growth in vitro. Parallel screening employing the simplified model organism Caenorhabditis elegans, fed the Lactobacillus strains as a food source, revealed that one L. pentosus and one L. coryniformis strains significantly induced prolongevity effects and protection from pathogen-mediated infection. Moreover, both strains displayed adhesion to human intestinal epithelial Caco-2 cells and were able to outcompete foodborne pathogens for cell adhesion. Overall, these results are suggestive of beneficial features for novel LAB strains, which renders them promising candidates as starters for the manufacturing of fermented table olives with probiotic added value.

Keywords: foodborne bacteria, fermented foods, nematode, autochtonous bacteria, plant food matrix

Introduction

The most recent definition of “probiotic” was formulated by an expert consultation of international scientists working on behalf of FAO/WHO (Food and Agriculture Organization/World Health Organization), and refers to viable, non-pathogenic microorganisms (bacteria and/or yeast) that when ingested in adequate amounts, are able to reach and colonize the Gastro-Intestinal (GI) tract and to confer health benefits to the host (FAO/WHO, 2006). The main benefits associated with probiotic intake include gut health and immune modulation (Ritchie and Romanuk, 2012; Hill et al., 2014). In particular, probiotic consumption can influence the microbial composition and balance within the intestinal microbiota. Production of antimicrobial substances such as organic acids, hydrogen peroxide, antifungal peptides, and bacteriocins, contributes to decrease harmful microorganisms and promotes growth and stability of beneficial bacteria, such as lactobacilli and bifidobacteria (Magnusson and Schnürer, 2001; Baker et al., 2009; Abriouel et al., 2012; Amund, 2016; Hegarty et al., 2016). Probiotic capacity greatly varies among strains belonging to different genera and species. The most common bacterial strains employed as probiotics are found within LAB (Lactic Acid Bacteria) species belonging to the Bifidobacterium, Lactobacillus, and Streptococcus genera (Saulnier et al., 2009). Members of the Lactobacillus genus are especially relevant as foodborne probiotics because they can be exploited also from the technological viewpoint, as their metabolic properties lead to production of a wide spectrum of molecules conferring specific organoleptic quality to fermented products. Moreover, several lactobacilli are considered Generally Recognized as Safe (GRAS) and are largely used as starter and/or protective cultures in fermented vegetables, sausages, fish and dairy products (Giraffa et al., 2010; Garrigues et al., 2013; Montoro et al., 2016).

The growing demand for plant-based foods is presently driving selection of bacteria which are able to grow on fermentable vegetable sources (Granato et al., 2010). Vegetable fermented foods such as table olives, pickles, sauerkraut, and kimchi, are slowly overtaking the role of fermented products of animal origin (dairies and sausages) as leading source of live bacteria in human diets, and they are also increasingly considered as novel reservoirs of yet uncharacterized probiotic strains (Ranadheera et al., 2010). Table olives could therefore represent a natural source for the isolation of novel probiotic bacterial strains. This is especially true for those olives fermented with traditional procedures relying on the activity of indigenous microbial consortia of environmental origin. The microbiota of processed olives and brines includes, among others, several LAB species such as L. plantarum, L. pentosus, L. paracasei, L. rhamnosus, Leuconostoc mesenteroides (Arroyo-López et al., 2008; Hurtado et al., 2012; Zinno et al., 2017).

Fermented vegetable matrices are presently recognized not only as a source, but also as a vehicle of probiotic bacteria. Recent studies demonstrated that LAB species isolated from different table olive cultivars exhibit probiotic features, such as resistance to acid and bile salts, antimicrobial activity and interaction with intestinal epithelial cells. This suggests their potential application as novel probiotic candidates for in vivo studies in animals and humans (Bevilacqua et al., 2010; Abriouel et al., 2012; Argyri et al., 2013; Botta et al., 2014; Montoro et al., 2016). However, simplified in vitro/in vivo models represent useful and less expensive screening tools to identify probiotic strains from a large number of microbial candidates. Human intestinal epithelial Caco-2 cells are a well characterized enterocyte-like cell line, capable of expressing the morphological and functional differentiation features which are typical of mature enterocytes, including cell polarity and a functional brush border (Sambuy et al., 2005). The Caco-2 cell line has been extensively used as a reliable in vitro system to study the adhesion capacity of lactobacilli as well as their probiotic effects, such as protection against intestinal injury induced by pathogens (Liévin-Le Moal et al., 2002; Resta-Lenert and Barrett, 2003; Roselli et al., 2006; Montoro et al., 2016).

The nematode Caenorhabditis elegans is becoming an increasingly valuable in vivo model to study host-probiotic interactions. Its success lies in the transparency of the body, in the small size and in the absence of ethical issues. Moreover, it is inexpensive to maintain and suitable for screening studies (Clark and Hodgkin, 2014). C. elegans is a powerful tool to test the effects of ingested bacteria on host physiology and it can also be useful in providing mechanistic insights on the beneficial effects of probiotics. A growing number of studies employing the C. elegans model system demonstrated that ingestion of lactobacilli and bifidobacteria can prolong the lifespan of nematodes and modify host defense (Kim and Mylonakis, 2012; Komura et al., 2013; Park et al., 2015). The L. gasseri strain SBT2055, which was reported to exert beneficial effects in mice and humans, showed a positive impact on longevity and/or aging in this nematode (Nakagawa et al., 2016). The health-promoting L. delbrueckii subspecies bulgaricus was also found to increase the lifespan of nematodes (Zanni et al., 2017), further highlighting the power of this in vivo model.

The aim of the present study was the identification and characterization of novel potentially probiotic strains of L. pentosus and L. coryniformis, deriving from a LAB collection of isolates from Nocellara del Belice table olives (Zinno et al., 2017). We used a combination of in vitro and in vivo approaches, including Caco-2 cell cultures and the C. elegans nematode model, to select specific strains displaying beneficial host-microbe interactions. The autochtonous nature of the food fermenting microbiota of origin, as well as the GRAS status of LAB species, allows to employ these strains as starter cultures in food fermentations, with the added value of providing health promoting traits.

Materials and methods

Bacterial strains and growth conditions

The LAB strains described in this work, as well as reference strains L. plantarum ATCC® 14917™, L. pentosus ATCC® 8041™ and L. rhamnosus GG ATCC® 53103™ (LGG), were grown in De Man Rogosa Sharpe (MRS) medium for 24–48 h at 30 or 37°C under anaerobic conditions. The enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli strain K88 (ETEC, O149:K88ac, provided by The Lombardy and Emilia Romagna Experimental Zootechnic Institute, Reggio Emilia, Italy) and E. coli strain OP50 were grown in Luria-Bertani (LB) broth at 37°C overnight. Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium LT2 and Listeria monocytogenes OH were routinely grown in Tryptone Soya Broth (TSB) at 37 and 30°C, respectively. All media and supplements were provided by Oxoid (Milan, Italy).

Species identification

For taxonomical identification, 16S rDNA gene fragments were amplified from LAB isolates using the P0-P6 primer pair (P0: 5′-GAGAGTTTGATCCTGGCT-3′; P6: 5′-CTACGGCTACCTTGTTAC-3′; Di Cello and Fani, 1996). Two μl of DNA extracted by microlysis were used for PCR amplification with the following program: 95°C for 10 min, 30 cycles at: 94°C for 1 min, 55°C for 90 s, 72°C for 150 s; one step at 55°C for 10 min followed by a final step at 72°C for 10 min. Amplified PCR fragments were analyzed by gel electrophoresis in 0.8% agarose in 1X TAE and then purified with NucleoSpin Gel and PCR clean-up purification kit (Macherey-Nagel, Germany). Sequencing of purified 16S rDNA fragments was performed at Bio-Fab Research (Italy) laboratories. For taxonomical identification, DNA sequences were compared with those reported in the BLAST NCBI (National Center for Biotechnology Information, Bethesda, USA) database. Nucleotide sequences of the amplified 16S rDNA from each LAB isolate were submitted to GenBank, and the corresponding accession numbers are reported in Table 1.

Table 1.

List of LAB isolates deriving from Nocellara del Belice table olives fermented with Sivigliano or Castelvetrano methods and related species identified by 16S rDNA sequencing.

| Strain ID | Bacterial species | % Identity with reference species in BLAST database | Source of isolation | GenBank accession number |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C303.8 | Enterococcus gallinarum | 99 | Castelvetrano | MG585222 |

| C301.1 | Enterococcus gallinarum | 99 | Castelvetrano | MG585223 |

| C302.1 | Enterococcus casseliflavus | 99 | Castelvetrano | MG585224 |

| C302.4 | Enterococcus casseliflavus | 99 | Castelvetrano | MG585225 |

| C303.6 | Enterococcus casseliflavus | 99 | Castelvetrano | MG585226 |

| C304.2 | Leuconostoc mesenteroides | 99 | Castelvetrano | MG585227 |

| I307.27 | Leuconostoc mesenteroides | 99 | Sivigliano | MG953414 |

| G307.7 | Leuconostoc mesenteroides | 99 | Sivigliano | MG585228 |

| G3010.28 | Leuconostoc mesenteroides | 99 | Sivigliano | MG585229 |

| G3010.29 | Leuconostoc mesenteroides | 99 | Sivigliano | MG585230 |

| H306.1 | Leuconostoc mesenteroides | 99 | Sivigliano | MG585231 |

| I307.20 | Leuconostoc mesenteroides | 99 | Sivigliano | MG585232 |

| I307.22 | Leuconostoc mesenteroides | 99 | Sivigliano | MG585233 |

| I307.29 | Leuconostoc mesenteroides | 99 | Sivigliano | MG585234 |

| I306.9 | Leuconostoc mesenteroides | 99 | Sivigliano | MG585235 |

| I3010.34 | Leuconostoc mesenteroides | 99 | Sivigliano | MG585236 |

| L309.4 | Leuconostoc mesenteroides | 98 | Sivigliano | MG585237 |

| C305.2 | Leuconostoc mesenteroides | 99 | Castelvetrano | MG585238 |

| C305.16 | Leuconostoc mesenteroides | 99 | Castelvetrano | MG585257 |

| C305.5 | Lactobacillus pentosus | 99 | Castelvetrano | MG585239 |

| D301.4 | Lactobacillus pentosus | 99 | Castelvetrano | MG585240 |

| D302.23 | Lactobacillus pentosus | 98 | Castelvetrano | MG585241 |

| D302.29 | Lactobacillus pentosus | 99 | Castelvetrano | MG585242 |

| G306.1 | Lactobacillus pentosus | 99 | Sivigliano | MG585243 |

| G306.2 | Lactobacillus pentosus | 99 | Sivigliano | MG585244 |

| G308.65 | Lactobacillus pentosus | 99 | Sivigliano | MG953413 |

| H3010.5 | Lactobacillus pentosus | 99 | Sivigliano | MG585245 |

| I306.2 | Lactobacillus pentosus | 99 | Sivigliano | MG585246 |

| H308.2 | Lactobacillus pentosus | 99 | Sivigliano | MG585247 |

| I308.32 | Lactobacillus pentosus | 100 | Sivigliano | MG585248 |

| D303.36 | Lactobacillus pentosus | 99 | Castelvetrano | MG585249 |

| H3010.1 | Lactobacillus pentosus | 99 | Sivigliano | MG585250 |

| I306.12 | Lactobacillus coryniformis | 99 | Sivigliano | MG585251 |

| H307.1 | Lactobacillus coryniformis | 99 | Sivigliano | MG585252 |

| C305.1 | Lactobacillus coryniformis | 99 | Castelvetrano | MG585253 |

| H307.6 | Lactobacillus coryniformis | 99 | Sivigliano | MG585254 |

| C303.1 | Lactobacillus oligofermentans | 99 | Castelvetrano | MG585255 |

| G3010.31 | Lactobacillus oligofermentans | 99 | Sivigliano | MG585256 |

| C371.10 | Enterococcus gallinarum | 97 | Castelvetrano | MG585258 |

| C373.1 | Enterococcus gallinarum | 98 | Castelvetrano | MG585259 |

| D371.5 | Lactobacillus pentosus | 99 | Castelvetrano | MG585260 |

| D372.20 | Lactobacillus pentosus | 99 | Castelvetrano | MG585261 |

| D373.37 | Lactobacillus pentosus | 99 | Castelvetrano | MG585262 |

| I379.8 | Lactobacillus pentosus | 99 | Sivigliano | MG585263 |

| G377.8 | Lactobacillus pentosus | 99 | Sivigliano | MG585264 |

| G378.30 | Lactobacillus pentosus | 99 | Sivigliano | MG585265 |

| H376.2 | Lactobacillus coryniformis | 98 | Sivigliano | MG585266 |

| H376.5 | Lactobacillus coryniformis | 99 | Sivigliano | MG585267 |

| H377.3 | Lactobacillus coryniformis | 99 | Sivigliano | MG585268 |

Multiplex PCR assay

L. plantarum/L. pentosus strains were subjected to a multiplex PCR assay using the recA gene-based primers paraF (5′-GTC ACA GGC ATT ACG AAA AC-3′), pentF (5′-CAG TGG CGC GGT TGA TAT C-3′), planF (5′-CCG TTT ATG CGG AAC ACC TA-3′), and pREV (5′-TCG GGA TTA CCA AAC ATC AC-3′; Torriani et al., 2001). The PCR mixture included 1.5 mM MgCl2, the primers paraF, pentF, and pREV (0.25 μM each), 0.12 μM primer planF, 0.2 mM dNTPs, 3 U Taq DNA Polymerase (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, USA). Two μl of DNA extracted by microlysis were used for the reaction. PCR programs consisted of an initial denaturation step at 94°C for 3 min, followed by 30 cycles of amplification (denaturation at 94°C for 30 s, annealing at 56°C for 10 s, and elongation at 72°C for 30 s), and a final extension step at 72°C for 5 min. The PCR products were visualized on a 2% agarose gel in 1X TAE buffer and digitally captured by using ImageQuant LAS 4000 (GE Healthcare Life Sciences, Little Chalfont, UK).

Rep-PCR fingerprinting

Two μl of DNA extracted by microlysis from selected L. coryniformis and L. pentosus strains (Microzone, Haywards Heath, UK) were used for PCR amplification with primer GTG5 (5′-GTGGTGGTGGTGGTG-3′), as previously described (Zinno et al., 2017), or with the ERIC primer (ERIC1R: 5′-ATGTAAGCTCCTGGGGATTCAC-3′; ERIC2: 5′-AAGTAAGTGACTGGGGTGAGCG-3′; de La Puente-Redondo et al., 2000).

For ERIC Rep-PCR, DNA amplification was carried out in 25 μl PCR mixture containing 1X PCR buffer, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM dNTPs, 3 U of Taq DNA Polymerase (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, USA) and 0.6 μM primers. Each cycle consisted of an initial denaturation step at 95°C for 3 min followed by 30 cycles of amplification (94°C for 1 min, 40°C for 1 min, 72°C for 1 min), and a final extension step at 72°C for 8 min. Amplified products were analyzed by gel electrophoresis (80 V for 4 h) in 1.8% agarose in 1X TAE. The gels were visualized under UV and digitally captured by using ImageQuant LAS 4000 (GE Healthcare Life Sciences, Little Chalfont, UK).

Acid and bile salt tolerance assay

Tolerance to gastrointestinal conditions of selected L. coryniformis and L. pentosus strains was evaluated according to (Vizoso Pinto et al., 2006). Three ml of overnight bacterial suspensions were centrifuged at 5,000 × g for 15 min at 4°C and the corresponding pellet was diluted 1:1 in a sterile electrolyte solution simulating salivary juice (Simulated Salivary Juice, SSJ), composed of 6.2 g/l NaCl, 2.2 g/l KCl, 0.22 g/l CaCl2, 1.2 g/l NaHCO3 pH 6.9 in which lysozyme was added to a final concentration of 100 mg/l. The mixed suspension was incubated for 5 min at 37°C. Subsequently, the sample was diluted 3:5 with Simulated Gastric Juice (SGJ) containing 6.2 g/l NaCl, 2.2 g/l KCl, 0.22 g/l CaCl2, 1.2 g/l NaHCO3 pH 2.5 and 3 g/l pepsin, and incubated for 1 h at 37°C. After incubation, 1 ml aliquot of the sample was serially diluted and plated, in triplicate, onto MRS agar. The remaining sample was diluted 1:4 in Simulated Pancreatic Juice (SPJ) consisting of 6.4 g/l NaHCO3, 0.239 g/l KCl, 1.28 g/l NaCl, 0.5% bile extract, 0.1% pancreatin at pH 7.2, and incubated for 3 h at 37°C. At 2 and 3 h incubation times, 1 ml aliquots were withdrawn, serially diluted and plated on MRS agar. Aliquots of overnight inocula were also tested to determine the CFU/ml at the initial time point (t0) for each strain. In parallel, control samples were treated with Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS) and subjected to the same procedure. Survival capacity was calculated as the percentage of 1– [(log CFU/mlt0-log CFU/mlSPJ3h)/log CFU/mlt0], where CFU/mlSPJ3h represented the total viable counts (CFU/ml) for each strain at the final time point of incubation in SPJ, and CFU/mlt0 represented the total viable counts at the initial time point. All enzymes and salts used in the assay were provided by Sigma Aldrich (Milan, Italy).

Antibiotic susceptibility tests

Antibiotic susceptibility was performed for a selected panel of antibiotics, namely ampicillin, tetracycline, chloramphenicol, and erythromycin, chosen as representatives of the most commonly used pharmacological classes of antimicrobials. For L. pentosus, each antibiotic was used at the breakpoint concentration defined by the FEEDAP Panel (EFSA, 2012). For L. coryniformis, which was not listed in the EFSA guidance document, we referred to the antibiotic concentrations reported by (Lara-Villoslada et al., 2007). Two μl of overnight bacterial cultures (OD600 = 1.3) were spotted onto MRS agar plates containing ampicillin, tetracycline, chloramphenicol or erythromycin, which were used at the following breakpoint concentrations: 2 mg/l, 32 mg/l, 8 mg/l, 1 mg/l, respectively, for L. pentosus, and 10 mg/l, 30 mg/l, 30 mg/l, 15 mg/l, respectively, for L. coryniformis. Plates were incubated for 24 h at 37°C in anaerobic conditions. Strains able to grow were considered resistant (R). The Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) for ampicillin and erythromycin of selected resistant strains was determined by broth microdilution assay, as described in (Devirgiliis et al., 2008). The antibiotic concentrations tested ranged from 1 to 20 mg/l and from 0.5 to 10 mg/l for ampicillin and erythromycin, respectively. Antibiotics were provided by Sigma Aldrich (Milan, Italy).

Antimicrobial activity

To evaluate the antagonistic activity of L. coryniformis and L. pentosus strains against pathogens the agar double-layer diffusion method was performed (Damaceno et al., 2017). The indicator strains used were: S. enterica serovar Typhimurium LT2, L. monocytogenes OH and ETEC K88. Two μl/each of L. coryniformis and L. pentosus overnight cultures (OD600 = 1.3) were spotted onto MRS agar and incubated at 37°C for 24 h in anaerobic conditions. After incubation, cells were killed by chloroform exposure for 30 min. Plates were then overlaid with 7 ml TSA soft agar, which had been previously inoculated with 1% (v/v) of each pathogen indicator strain, and incubated at the corresponding optimal growth temperature for 24 h. The antagonist activity was recorded as the diameter (mm) of growth inhibition halo around each spot.

Caco-2 cell culture and growth conditions

The human intestinal Caco-2/TC7 cell line was provided by Monique Rousset (Institute National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale, INSERM, France). These cells derive from parental Caco-2 cells, exhibit a more homogeneous expression of differentiation traits, and have been reported to express higher metabolic and transport activities than the original cell line, more closely resembling small intestinal enterocytes (Caro et al., 1995). The Caco-2/TC7 cells were routinely maintained at 37°C in an atmosphere of 10% CO2/95% air at 90% relative humidity and grown on plastic tissue culture flasks (Becton Dickinson, Milan, Italy) in Dulbecco's modified Minimum Essential Medium (complete DMEM: 3.7 g/L NaHCO3, 4 mM glutamine, 10% heat inactivated fetal calf serum, 1% nonessential amino acids, 105 U/l penicillin and 100 mg/l streptomycin). All cell culture reagents were from Euroclone (Milan, Italy).

Competition assay for pathogen adhesion to Caco-2 cells

Caco-2 cells were seeded in 12-well plates (Becton Dickinson) and, after confluency, were left for 14-17 days to allow differentiation (Sambuy et al., 2005). Medium was changed three times a week. Complete DMEM was replaced with antibiotic- and serum-free DMEM 16 h before the assay. To test the capacity of the selected L. pentosus and L. coryniformis strains to compete with pathogens for adhesion to Caco-2 cells, S. enterica serovar Typhimurium LT2 and L. monocytogenes OH pathogens were used as test strains. Preliminary experiments were performed to set up the optimal growth conditions for pathogens as well as for lactobacilli, to ensure that each strain could be used at the exponential growth phase. The viability of pathogens and lactobacilli in DMEM was also previously verified. On the day of the assay, overnight bacterial cultures were diluted 1:10 in LB (pathogens) or MRS media (lactobacilli) and grown for 4, 5, or 6 h to the exponential growth phase, according to the respective optimal conditions previously identified for each strain. After monitoring the OD600, appropriate amounts of bacterial cells were harvested by centrifugation at 5,000 × g for 10 min, resuspended in antibiotic- and serum-free DMEM and added to cell monolayers at a concentration of 1 × 107 CFU/well (pathogens) or 1 × 108 CFU/well (lactobacilli). Cells were incubated at 37°C for 1.5 h with either one of the two pathogens, alone or in combination with one of the two Lactobacillus strains. After incubation at 37°C for 1.5 h, non-adhering bacteria were removed by 5 washes with Hanks' Balanced Salt solution (HBSS: 137 mM NaCl, 5.36 mM KCl, 1.67 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MgCl2, 1.03 mM MgSO4, 0.44 mM KH2PO4, 0.34 mM Na2HPO4, 5.6 mM glucose) and cell monolayers were lysed with 1% Triton-X-100, according to (Roselli et al., 2006). Adhering, viable pathogen cells were quantified by plating appropriate serial dilutions of Caco-2 lysates on Violet Red Bile Glucose Agar (VRBGA, for Salmonella) or Listeria Selective Agar Base (Oxford, for Listeria). These two media were selective for pathogens, preventing the growth of lactobacilli.

C. elegans strain and growth conditions

The wild-type C. elegans strain, Bristol N2, was grown at 16°C on Nematode Growth Medium NGM plates covered by a layer of E. coli OP50, LGG, L. coryniformis, or L. pentosus strains, which were prepared as described in (Zanni et al., 2015).

C. elegans lifespan assay

Synchronized N2 adults were placed to lay embryos for 2 h on NGM plates, lawned with different bacteria, and then sacrificed. All lifespan assays started when the progeny became fertile (t0). Animals were transferred to new plates seeded with fresh lawns and monitored daily. They were scored as dead when they no longer responded to gentle touch with a platinum wire. At least 60 nematodes per condition were used in each experiment.

Estimation of bacterial titer within the nematode gut

For each experiment, 10 days old animals were washed and lysed according to (Uccelletti et al., 2010). Worm lysates were then plated onto MRS-agar plates. The number of CFU was counted after 48 h of incubation at 37°C, anaerobically.

Nematode brood size measurements

Progeny production was evaluated according to (Zanni et al., 2015) with some modifications. Briefly, synchronized worms obtained as above were grown on NGM plates seeded with bacteria and then allowed to lay embryos at 16°C. Next, animals were transferred onto a fresh bacteria plate every day, and the number of progeny was counted with a Zeiss Axiovert 25 microscope. The procedure was repeated until the mother worms stopped laying eggs. Each day the progeny production was recorded and was compared with the OP50- or LGG-fed nematodes.

Pharyngeal pumping assay

Pharyngeal pumping was analyzed as described in (Uccelletti et al., 2008) under Zeiss Axiovert 25 microscope by counting the number of grinder contractions of 10 animals for each treatment, during a period of 30 s. The analysis was performed in 13-days-adult worms, grown on different bacteria starting from embryo stage.

Body bending evaluation

The locomotion behavior of nematodes, fed with different bacteria from embryos hatching, was analyzed by body bending counting after 30 s. After several washes in M9 buffer to remove bacteria, nematodes were placed in 10 μl of M9 buffer allowing them to swim freely. About 10 worms for each experimental condition were monitored.

Lipofuscin analysis

The autofluorescence of intestinal lipofuscin was measured as an index of senescence at day 13 of adulthood. Randomly selected worms from the plate lawned with bacteria were washed three times with M9 buffer. Worms were then placed onto a 3% agar pad containing 20 mM sodium azide. Lipofuscin autofluorescence was detected by fluorescence microscopy (Zeiss Axiovert 25).

C. elegans killing assay

For killing assay 35 mm-NGM plates were spread with 60 μl of L. pentosus D303.36 or L. coryniformis H307.6 mixed with S. enterica serovar thyphimurium LT2 or L. monocytogenes OH, in 1:1 ratio; the strains were grown as indicated above. C. elegans synchronous L4 larvae were transferred onto the bacterial lawn and incubated at 25°C. Worms were monitored every day. Nematodes fed with pathogen alone were taken as control. A worm was considered dead when it failed to respond to touch.

Statistical analysis

All experiments were performed at least in triplicate. Data are presented as mean ± SD. Prior to the analysis, normal distribution and homogeneity of variance of all variables were assumed with Shapiro-Wilk and Levene's tests, respectively. For in vivo experiments in C. elegans the statistical significance was determined by Student's t-test or one-way ANOVA analysis coupled with a Bonferroni post test (GraphPad Prism 5.0 software, GraphPad Software Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA). For in vitro experiments, statistical significance was evaluated by one-way ANOVA, followed by post-hoc Tukey honestly significant difference (HSD) test. Statistical univariate analysis was performed with the “Statistica” software package (version 5.0; Stat Soft Inc., Tulsa, OK). Differences with p-values < 0.05 were considered significant and were indicated as follows: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001.

Results

Species identification of LAB isolates

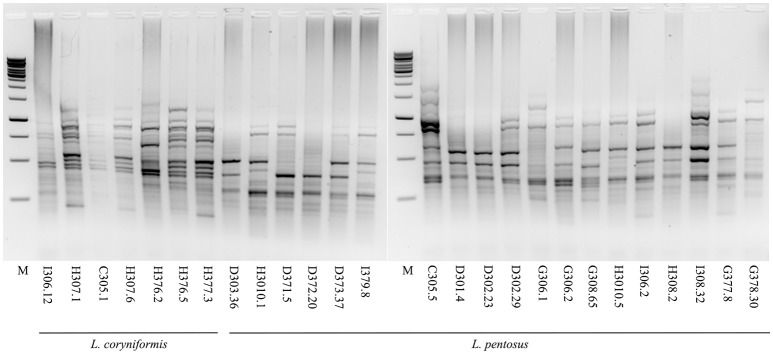

A total of 49 Lactic Acid Bacteria strains deriving from Nocellara del Belice table olives fermented with Spanish or Castelvetrano methods, recently collected in our previous work (Zinno et al., 2017), were characterized at the species level. Ribosomal 16S DNA sequencing allowed the identification of 4 Enterococcus gallinarum, 3 E. casseliflavus, 14 L. mesenteroides, 7 L. coryniformis and 2 L. oligofermentans (Table 1). For 19 isolates, however, similarity searches using sequenced ribosomal DNA fragments retrieved ambiguous species assignments, as the genomic sequences matched both L. pentosus and L. plantarum with similar scores. These isolates were therefore subjected to a multiplex PCR assay, using recA gene-based primers, which are able to discriminate L. plantarum, L. paraplantarum, and L. pentosus species (Torriani et al., 2001). The PCR results clarified that all 19 strains belonged to the L. pentosus species (Figure S1). L. pentosus and L. coryniformis isolates were chosen as potential probiotic candidates for further screening, as these two species are widely employed as starter and/or protective cultures in table olive manufacturing. To assess the presence of unique strains, these isolates were subjected to strain typing using a combination of GTG5 rep-PCR (Figure 1) and of Enterobacterial Repetitive Intergenic Consensus sequence PCR (ERIC-PCR, data not shown). The results shown in Figure 1 revealed the presence of distinct fingerprinting profiles characterizing each strain within both species, indicating that each of the 19 L. pentosus and 7 L. coryniformis isolates represented a unique strain. Therefore, they were all subjected in parallel to the subsequent assays aimed at characterizing probiotic capacity.

Figure 1.

Strain typing of the selected L. pentosus and L. coryniformis isolates by rep-PCR. Agarose gel electrophoresis of GTG5 rep-PCR fingerprinting profiles of L. coryniformis and L. pentosus strains. M: 1 kb DNA ladder (Microzone, UK).

In vitro tolerance to simulated gastro-intestinal conditions

Tolerance to gastrointestinal conditions was assayed using a series of sequential treatments that simulate bacterial transit along the mammalian GI tract. As shown in Table 2, each treatment differentially affected survival of the tested strains. In particular, 1 h incubation in SGJ, characterized by acidic pH (2.5), exerted a mild but significant reduction of bacterial counts for all the L. coryniformis and L. pentosus strains. Percent survival was close to 90% in all cases, with the exception of L. coryniformis isolate I306.12 which was almost unaffected by this treatment (98% survival), while two other L. coryniformis strains (C305.1 and H376.2) were unable to survive this condition (Table 2). Subsequent treatment of the surviving strains with SPJ containing bile salts and pancreatin, displayed a more severe impact on overall bacterial survival, as revealed by the inability of 5 L. pentosus strains to tolerate pancreatic conditions after 2 h of incubation (Table 2). Both 2 and 3 h treatments in SPJ are usually employed to mimick transit time in the GI tract. In our case however, 3 h incubation in SPJ did not affect overall bacterial survival any further than the 2 h incubation timepoint, with the exception of the L. pentosus strain G378.30 which did not survive, and of 5 L. pentosus strains that showed a decrease of about 1.5 log in CFU/ml. In order to compare the results obtained, survival capacity was calculated for each strain as well as for the reference probiotic strain LGG (see Materials and Methods). Overall, the capacity of the tested strains to tolerate gastrointestinal conditions ranged between 50 and 80%. Notably, 7 L. pentosus and 4 L. coryniformis strains showed survival capacities similar or higher than those of the reference probiotic strain LGG, namely about 70% at the end of both treatments (Table 2).

Table 2.

Survival of L. pentosus and L. coryniformis strains under in vitro simulated gastro-intestinal conditions.

| Bacterial species | Strain ID | t0 | SGJ | SPJ 2h | SPJ 3h | Survival capacity (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L. pentosus | C305.5 | 8.20 ± 0.02a | 7.53 ± 0.03b | 6.18 ± 0.02c | 6.14 ± 0.03c | 74.92 |

| D301.4 | 9.12 ± 0.08a | 7.75 ± 0.15b | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| D302.23 | 8.93 ± 0.03a | 8.40 ± 0.07b | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| D302.29 | 9.23 ± 0.003a | 8.70 ± 0.05b | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| G306.1 | 8.31 ± 0.18a | 7.77 ± 0.05b | 5.97 ± 0.07c | 5.94 ± 0.07c | 71.44 | |

| G306.2 | 8.91 ± 0.12a | 8.43 ± 0.02b | 6.99 ± 0.02c | 6.91 ± 0.05c | 77.60 | |

| G308.65 | 9.09 ± 0.06a | 8.30 ± 0.02b | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| H3010.5 | 9.49 ± 0.09a | 8.48 ± 0.05b | 6.20 ± 0.12c | 4.72 ± 0.15d | 49.76 | |

| I306.2 | 8.61 ± 0.13a | 8.07 ± 0.09b | 6.69 ± 0.03c | 6.50 ± 0.10c | 75.47 | |

| H308.2 | 8.63 ± 0.24a | 8.10 ± 0.05b | 6.66 ± 0.04c | 5.99 ± 0.10d | 69.43 | |

| I308.32 | 9.19 ± 0.01a | 8.06 ± 0.02b | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| G377.8 | 9.38 ± 0.32a | 8.23 ± 0.01b | 6.77 ± 0.02c | 6.44 ± 0.07c | 68.64 | |

| G378.30 | 9.17 ± 0.19a | 8.08 ± 0.07b | 5.52 ± 0.30c | 0 | 0 | |

| D303.36 | 9.05 ± 0.14a | 8.54 ± 0.03b | 5.21 ± 0.07c | 4.68 ± 0.04d | 51.65 | |

| H3010.1 | 8.92 ± 0.21a | 6.81 ± 0.35b | 5.01 ± 0.06c | 4.74 ± 0.15c | 53.17 | |

| D371.5 | 8.66 ± 0.04a | 7.84 ± 0.04b | 5.62 ± 0.51c | 5.32 ± 0.05c | 61.43 | |

| D372.20 | 9.10 ± 0.06a | 7.85 ± 0.03b | 5.99 ± 0.03c | 4.56 ± 0.33d | 50.09 | |

| D373.37 | 8.53 ± 0.05a | 7.57 ± 0.09b | 6.27 ± 0.2c | 6.23 ± 0.02c | 72.99 | |

| I379.8 | 8.95 ± 0.04a | 8.25 ± 0.03b | 7.02 ± 0.04c | 6.88 ± 0.02d | 76.88 | |

| L. coryniformis | I306.12 | 8.71 ± 0.093a | 8.56 ± 0.12a | 6.80 ± 0.25b | 6.71 ± 0.03b | 77.04 |

| H307.1 | 8.80 ± 0.09a | 8.09 ± 0.13b | 6.13 ± 0.06c | 6.18 ± 0.04c | 70.20 | |

| C305.1 | 8.25 ± 0.01 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| H307.6 | 9.66 ± 0.24a | 8.54 ± 0.04b | 7.80 ± 0.05c | 7.09 ± 0.10d | 73.44 | |

| H376.2 | 8.55 ± 0.05 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| H376.5 | 8.35 ± 0.01a | 7.54 ± 0.14b | 5.55 ± 0.41c | 5.49 ± 0.15c | 65.82 | |

| H377.3 | 8.76 ± 0.06a | 8.21 ± 0.04b | 6.98 ± 0.04c | 6.96 ± 0.01c | 79.49 | |

| L. rhamnosus | GG | 8.7 ± 0.021a | 8.1 ± 0.39b | 6.9 ± 0.04c | 6.1 ± 0.04d | 69.91 |

Values represent mean log (CFU/ml) ± standard deviation. Distinct letters indicate significance at p value < 0.05 among log (CFU/ml) values for the different tested conditions, within each strain.

Survival capacity is expressed as the percentage of 1– [(log CFU/mlt0 – log CFU/mlSPJ3h)/log CFU/mlt0].

Antibiotic resistance

The L. coryniformis and L. pentosus strains were analyzed for resistance to ampicillin, tetracycline, chloramphenicol, and erythromycin, as representatives of different pharmacological classes of antimicrobials widely employed in human and veterinary medicine. The selected antibiotics were used at the breakpoint concentrations proposed by the European Food Safety Agency (EFSA) for L. pentosus (EFSA, 2012), while for L. coryniformis they were chosen according to (Lara-Villoslada et al., 2007). Table 3 shows the antibiotic resistance panel for each tested bacterial strain. Overall, the majority of the tested strains displayed susceptibility to the selected antibiotics. However, all L. pentosus strains displayed resistance to ampicillin, with the exception of isolate C305.5. As for the other antibiotics, all 19 L. pentosus strains were sensitive to tetracycline and chloramphenicol, while 3 strains, namely D303.36, H3010.1, and I379.8, displayed phenotypic resistance to erythromycin. All L. coryniformis strains resulted susceptible to all tested antibiotics (Table 3). The ampicillin and erythromycin resistant L. pentosus strains were further investigated by quantifying their MIC values for the two antibiotics. MIC values above the breakpoints, corresponding to 2 mg/l for ampicillin and 1 mg/l for erythromycin, were considered indicative of phenotypic antibiotic resistance. The results show that ampicillin MIC values ranged between 2 and 20 mg/l, with variable distribution within the 18 analyzed strains. Three of them, namely L. pentosus D303.36, H3010.1, and I379.8, which were resistant to both antibiotics, also displayed erythromycin MIC values of 1.125 or 2.5 mg/l (Table 3).

Table 3.

Antibiotic resistance of L. pentosus and L. coryniformis strains.

| Antibiotica | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bacterial species | Strain ID | Ampicillin (2 mg/l) | Tetracycline (32 mg/l) | Chloramphenicol (8 mg/l) | Erythromycin (1 mg/l) |

| L. pentosus | C305.5 | S | S | S | S |

| D301.4 | R (20) | S | S | S | |

| D302.23 | R (20) | S | S | S | |

| D302.29 | R (2) | S | S | S | |

| G306.1 | R (8) | S | S | S | |

| G306.2 | R (4) | S | S | S | |

| G308.65 | R (16) | S | S | S | |

| H3010.5 | R (4) | S | S | S | |

| I306.2 | R (8) | S | S | S | |

| H308.2 | R (12) | S | S | S | |

| I308.32 | R (8) | S | S | S | |

| G377.8 | R (4) | S | S | S | |

| G378.30 | R (8) | S | S | S | |

| D303.36 | R (16) | S | S | R (2.5) | |

| H3010.1 | R (4) | S | S | R (1.25) | |

| D371.5 | R (4) | S | S | S | |

| D372.20 | R (8) | S | S | S | |

| D373.37 | R (8) | S | S | S | |

| I379.8 | R (4) | S | S | R (2.5) | |

| Ampicillin (10 mg/l) | Tetracycline (30 mg/l) | Chloramphenicol (30 mg/l) | Erythromycin (15 mg/l) | ||

| L. coryniformis | I306.12 | S | S | S | S |

| H307.1 | S | S | S | S | |

| C305.1 | S | S | S | S | |

| H307.6 | S | S | S | S | |

| H376.2 | S | S | S | S | |

| H376.5 | S | S | S | S | |

| H377.3 | S | S | S | S | |

Each antibiotic was used at the microbiological breakpoint indicated in parenthesis, according to the bacterial species.

LAB strains resulting sensitive or resistant to antibiotic are referred as S or R, respectively.

MIC values (expressed as mg/l) for resistant strains are indicated in parenthesis.

Antimicrobial activity against pathogens

The great majority of the L. pentosus and L. coryniformis strains displayed antagonistic activity in the agar double-layer diffusion test against all three pathogens chosen as indicator strains (S. enterica serovar Typhimurium LT2, L. monocytogenes OH, and ETEC K88). The strength of such inhibition was variable among the different lactobacilli, as shown by broad variability of the inhibition halo diameters on all 3 pathogen test strains (Table S1). The only exception was represented by L. pentosus strain C305.5, which was unable to inhibit growth of S. enterica serovar Typhimurium LT2 (Table 4). In particular, the majority of the 19 L. pentosus strains produced inhibition halo diameters above median value when tested against all three pathogens. The L. coryniformis strains, on the other hand, showed overall inhibition halo diameters between 1 mm and the corresponding median value against all three pathogens, with the exception of two strains, namely H307.1 and H377.3, both displaying inhibition halo diameters above the median against Salmonella and ETEC (Table 4). Notably, both of these latter strains had shown survival capacities comparable to that of the well characterized probiotic strain LGG following simulated gastro-intestinal condition, and were both susceptible to all tested antibiotics.

Table 4.

Antimicrobial activity of L. pentosus and L. coryniformis strains against indicator pathogens.

| Pathogen strain | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bacterial species | Strain ID | S. enterica serovar Typhimurium LT2 | L. monocytogenes OH | ETEC K88 |

| L. pentosus | C305.5 | − | + | + |

| D301.4 | ++ | + | ++ | |

| D302.23 | ++ | ++ | ++ | |

| D302.29 | ++ | + | + | |

| G306.1 | ++ | + | + | |

| G306.2 | ++ | ++ | ++ | |

| G308.65 | ++ | + | + | |

| H3010.5 | + | ++ | ++ | |

| I306.2 | ++ | ++ | ++ | |

| H308.2 | ++ | + | ++ | |

| I308.32 | ++ | ++ | + | |

| G377.8 | + | ++ | ++ | |

| G378.30 | + | ++ | ++ | |

| D303.36 | ++ | + | + | |

| H3010.1 | ++ | ++ | ++ | |

| D371.5 | + | ++ | ++ | |

| D372.20 | + | ++ | ++ | |

| D373.37 | + | + | ++ | |

| I379.8 | + | ++ | ++ | |

| L. coryniformis | I306.12 | + | + | + |

| H307.1 | ++ | + | ++ | |

| C305.1 | + | + | + | |

| H307.6 | + | + | + | |

| H376.2 | + | + | + | |

| H376.5 | + | + | + | |

| H377.3 | ++ | + | ++ | |

Inhibitory activities refer to the measured inhibition halo diameter and are indicated as: – (diameter <1 mm);

+ (1 mm < diameter < median value); ++ (diameter > median value).

In vivo screening in C. elegans

In vivo screening of the L. pentosus and L. coryniformis strains for health-promoting traits was performed in the C. elegans model system, which was shown to display beneficial effects in response to administration of probiotic bacteria (Nakagawa et al., 2016). Lifespan analysis was initially used as a pre-screening assay to select those bacterial strains able to prolong worm longevity. To this aim, the lifespan of animals separately fed each of the isolated Lactobacillus strains starting from embryo hatching, was compared with that of control worms grown on LGG as the only bacterial source, or on the standard E. coli OP50 diet. The results are reported in Figure S2. Among the tested strains, the L. pentosus D303.36 diet induced a relevant increase in C. elegans longevity (Figure S2A), and animals fed L. coryniformis H307.6 showed similar viability with respect to those fed the probiotic strain LGG (Figure S2B). On the other hand, when compared to the control OP50 diet, none of the other tested strains determined significant increase in worm lifespan, with the exception of L. pentosus D371.5 (Figure S2A) and L. coryniformis H376.2 (Figure S2B), which led to significant lifespan reduction when used as the sole dietary source of bacteria. The L. coryniformis strain I306.12 induced an embryonic lethal phenotype, since embryos failed to develop into larvae (data not shown).

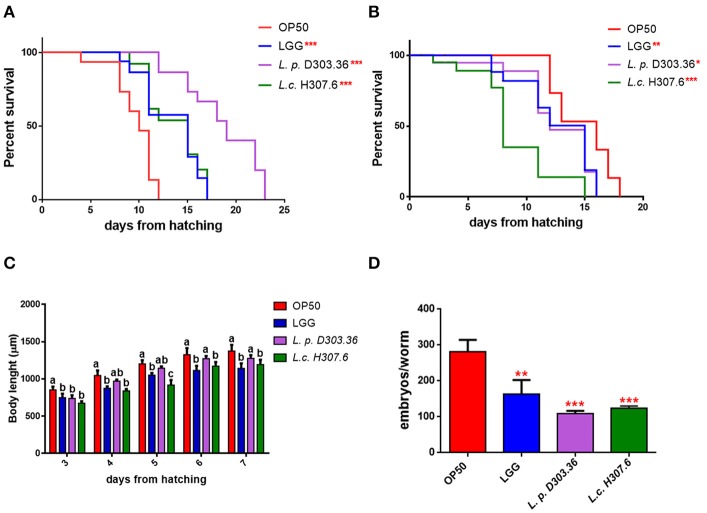

Therefore, the two L. pentosus D303.36 and L. coryniformis H307.6 strains were considered as the most promising candidates in terms of health-promoting features, and were selected for further analysis. Figure 2A shows that nematode median survival was recorded at days 18 and 15 when worms were fed L. pentosus D303.36 and L. coryniformis H307.6, respectively, as compared to 9.5 days in the case of OP50-fed worms. The above described effects on the longevity phenotype were not observed when worms were fed heat-killed bacteria, as shown in Figure 2B.

Figure 2.

Effect of the L. pentosus D303.36 and L. coryniformis H307.6 strains on C. elegans lifespan, body length, and fertility. (A) Kaplan–Mèier survival plots of N2 fed L. p. D303.36 and L. c. H307.6 strains, starting from embryo hatching; n = 60 for each single experiment. Lifespans of OP50- and LGG-fed animals are reported as controls. (B) Survival of C. elegans fed heat killed bacterial strains. Statistical analysis was evaluated by one-way ANOVA with the Bonferroni post-test; asterisks indicate significant differences (*p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001). (C) Effect of bacteria on larval development. Worm length was measured from head to tail at the indicated time points. Statistical analysis was performed by one-way ANOVA with the Bonferroni post-test; different letters indicate significant differences (p < 0.05). (D) Embryo production per worm in animals fed different bacterial strains. Bars represent the mean of three independent experiments (**p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001).

Microscopic observation allowed to evaluate other physiological effects promoted by the Lactobacillus strains in C. elegans: animals fed L. pentosus D303.36 or L. coryniformis H307.6 displayed reduced size with respect to OP50-fed animals along all developmental stages, similarly to the effect of feeding the probiotic strain LGG (Figure 2C). Moreover, C. elegans progeny production was significantly reduced when nematodes were fed L. pentosus D303.36 or L. coryniformis H307.6, with about 60% reduction of progeny number in both cases as compared to OP50-fed animals. A similar reduction was also observed in the case of LGG-fed animals, although to a lesser extent (Figure 2D).

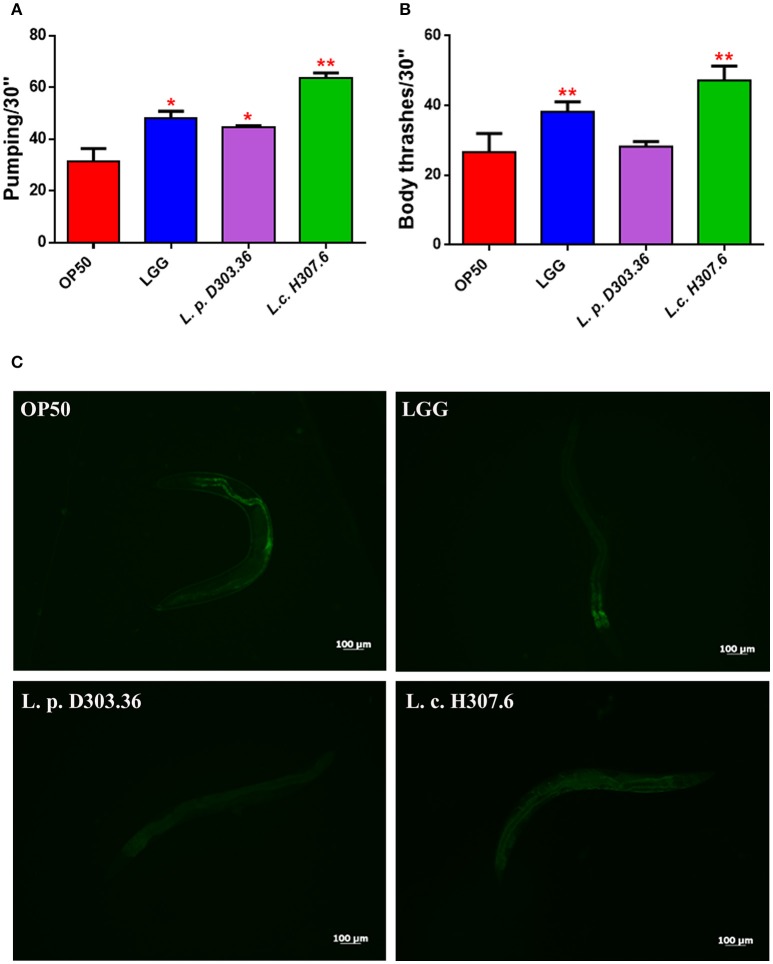

Subsequently, aging biomarkers were analyzed in order to evaluate the prolonged lifespan of C. elegans supplemented with the different isolates at 13 days of adulthood. The neuromuscular functionality of nematodes was investigated by measuring contractions of the pharynx to assess whether L. pentosus D303.36 and L. coryniformis H307.6 strains could impact on C. elegans swallowing capacity. Pharyngeal pumping rates increased when each of the two strains were administered to nematodes, with respect to the OP50 control (Figure 3A). In parallel, analysis of the locomotion behavior was performed to determine possible modifications of C. elegans mobility. Similarly to LGG-fed worms, body bending was increased when feeding L. coryniformis H307.6 as compared to OP50. On the other hand, the L. pentosus D303.36-based diet did not show any effect (Figure 3B). Evaluation of intestinal lipofuscin accumulation was performed as an additional aging biomarker. Fluorescence microscope analysis revealed a reduced fluorescent signal, diffused throughout the body of nematodes fed L. pentosus D303.36 or L. coryniformis H307.6. Similar results were obtained when feeding the probiotic control strain LGG. By contrast, nematodes fed OP50 showed intense fluorescence accumulating in large granules along the intestine, typical of aged animals (Figure 3C).

Figure 3.

Analysis of aging markers in C. elegans fed the L. pentosus D303.36 and L. coryniformis H307.6 strains. (A) Pumping rate of 13-days-old worms, measured for 30 s and determined from the mean of 10 worms for each bacterial strain. Worms fed OP50 or LGG were used as controls. (B) Body bend frequency, measured for 30 s, of C. elegans fed different Lactobacillus strains or OP50. Statistical analysis was performed by one-way ANOVA with the Bonferroni post-test; asterisks indicate significant differences (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01). (C) Autofluorescence of lipofuscin granules in C. elegans fed different bacterial strains on day 13. Ten worms were used for each measurement. Scale bar = 100μm.

To evaluate their colonization capacity, bacteria were recovered from C. elegans gut and quantified by measuring CFUs at 10-days adulthood stage. Both L. pentosus D303.36 and L. coryniformis H307.6 strains showed a colonization capacity almost identical to that of the probiotic control strain LGG (data not shown).

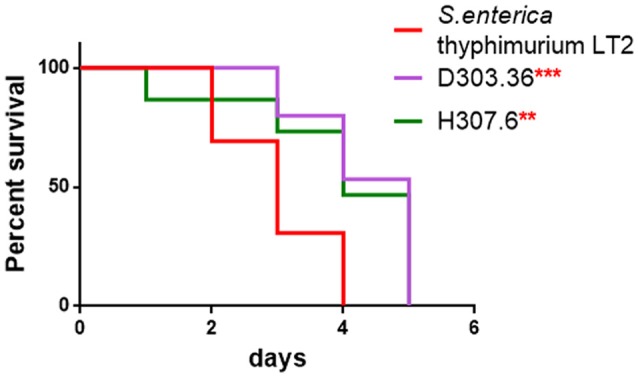

Probiotic strains were reported to protect C. elegans against infection mediated by several pathogens (Park et al., 2014; Neuhaus et al., 2017). Since both L. pentosus D303.36 and L. coryniformis H307.6 strains displayed antimicrobial activity against the three tested pathogens (Table 4), these two LAB strains were evaluated also for their protective potential in C. elegans against pathogen infection mediated death. S. enterica serovar Thyphimurium LT2 or L. monocytogenes OH were chosen for the assay as they represent important foodborne pathogens. The results in Figure 4 demonstrate that C. elegans displayed reduced survival on NGM medium when fed S. enterica Thyphimurium LT2 alone, as compared to nematodes supplemented with co-cultures of the same pathogen with L. pentosus D303.36 or L. coryniformis H307.6. In the case of L. monocytogenes OH, on the other hand, neither one of the co-cultures was able to abrogate premature death of the animals (data not shown).

Figure 4.

Rescuing potential of L. pentosus D303.36 and L. coryniformis H307.6 against Salmonella enterica infection. Kaplan–Mèier Survival plot of C. elegans fed L. pentosus D303.36 or L. coryniformis H307.6 in a 1:1 co-colture with S. enterica serovar Thyphimurium LT2. Worms fed Salmonella alone were taken as control (**p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001).

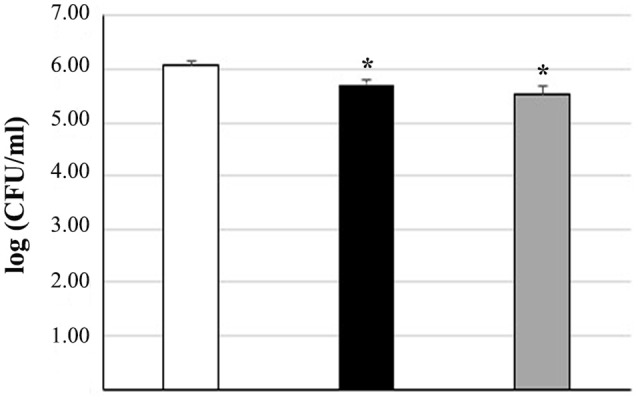

Reduction of pathogen adhesion to human intestinal epithelial cells by L. pentosus D303.36 and L. coryniformis H307.6 strains

Several pathogens, including S. enterica serovar Typhimurium, L. monocytogenes and ETEC, are able to adhere to the brush border of intestinal cells, damaging the structure of tight or adherens junctions (Boyle and Finlay, 2003; Köhler et al., 2007). Increasing evidence highlights the capacity of lactobacilli to inhibit pathogen adhesion to the intestinal mucosa and counteract the associated inflammatory processes, thus preventing intestinal disease in both humans and animals (Zhou et al., 2010; Asahara et al., 2011). The two L. pentosus D303.36 and L. coryniformis H307.6 strains were therefore analyzed for their capacity to reduce pathogen adhesion to Caco-2 cells, which represent a valuable in vitro model of human intestinal epithelium. Both strains, which were previously tested for their adhesion ability to Caco-2 cells (data not shown), were co-cultured with intestinal cells in combination with S. enterica serovar Typhimurium LT2 or L. monocytogenes OH.

Treatment of intestinal cells with L. pentosus D303.36 or L. coryniformis H307.6 reduced adhesion of S. enterica serovar Typhimurium LT2 by about 0.5 log CFU/ml (Figure 5). Statistical analysis performed by ANOVA revealed p-values < 0.05, indicating that, although to a mild extent, both strains were able to significantly counteract pathogen attachment to the cells. On the other hand, no protective effect of L. pentosus D303.36 or L. coryniformis H307.6 against L. monocytogenes OH could be observed (data not shown).

Figure 5.

Reduction of Salmonella enterica adhesion to Caco-2 cells by L. pentosus D303.36 and L. coryniformis H307.6. Cell counts of viable S. enterica serovar Thyphimurium LT2 adhering on differentiated Caco-2 cells treated with: S. enterica alone (control, white column); S. enterica in combination with L. pentosus D303.36 (black column) or L. coryniformis H307.6 (gray column). Columns represent the mean ± SD of four independent experiments. Data are reported as log of bacterial CFU recovered after plating. Statistical analysis was performed by one-way ANOVA, followed by post-hoc Tukey honestly significant difference (HSD) test. Asterisks indicate significant differences (*p < 0.05 vs. control).

Discussion

Table olives are increasingly recognized as a potential natural source of probiotic bacteria that could be exploited to obtain a health-promoting functional product (Bonatsou et al., 2017). Different olive cultivars are characterized by specific autochtonous fermenting microbiota (Heperkan, 2013), representing a valuable reservoir of novel strains of environmental origin. In particular, Nocellara del Belice is an important Italian olive cultivar, awarded the official PDO designation (Protected Designation of Origin, EC Regulation No 134/1998), whose microbial composition is dominated by several LAB species of technological and health-related interest (Aponte et al., 2010, 2012; Zinno et al., 2017). In the present work, a combination of in vitro and in vivo approaches was used to select novel potentially probiotic Lactobacillus strains deriving from a LAB collection of isolates from Nocellara del Belice table olives fermented with Spanish or Castelvetrano methods, that was previously established in our laboratory (Zinno et al., 2017). Characterization of LAB isolates at the species level identified Leuconostoc mesenteroides, L. pentosus, and L. coryniformis as the predominant species, along with L. oligofermentans, E. gallinarum, and E. casseliflavus as minor components. Among these isolates, L. pentosus and L. coryniformis were chosen as potential probiotic candidates for further analysis since increasing experimental evidence reports on health-promoting features displayed by several strains belonging to these species (Olivares et al., 2006; Abriouel et al., 2017; Bendali et al., 2017). Probiotic traits are known to be strain-specific (Saulnier et al., 2009; Amund, 2016), it is therefore important to consider that all selected L. pentosus and L. coryniformis isolates analyzed in this work displayed distinct fingerprinting profiles, therefore representing unique and novel strains.

Resistance to the harsh conditions of the upper GI tract is a key pre-requisite for efficient colonization by a probiotic strain (Dicks and Botes, 2010). As a first predictive phenotypic trait, tolerance to gastrointestinal conditions was assessed by evaluating the survival capacity of each strain in comparison with the well-characterized, commercial probiotic strain L. rhamnosus GG. Overall, the majority of the investigated strains showed 50–80% survival capacity to gastric and pancreatic juice treatments, with strain-dependent variability. Notably, 11 of the 26 Lactobacillus strains assayed in this study displayed survival rates equal or higher than that of the well characterized probiotic control strain LGG (70%) at the end of simulated digestion treatments, thus pointing at the diet, and to fermented foods in particular, as a relevant source of live microorganisms that can reach the host gut microbiota in a metabolically active state, where they can transiently colonize and interact with resident gut bacteria. An important trait to be verified for safety purposes concerns antibiotic resistance profiling (Imperial and Ibana, 2016). To this aim, all the L. coryniformis and L. pentosus strains were also analyzed for resistance to ampicillin, tetracycline, chloramphenicol or erythromycin, as representatives of distinct pharmacological classes of antimicrobials commonly used in human and veterinary medicine (Aminov, 2017). While the majority of the tested strains were susceptible to these antibiotics, all but one of the L. pentosus isolates showed phenotypic resistance to ampicillin, with a few of them diplaying erythromycin resistance as well. These strains will be subjected to further analysis to identify the corresponding antibiotic-resistance determinants and their genomic contexts, so that possible horizontal transmission can be ascertained.

Probiotics are known to be effective in preventing or counteracting foodborne infections by reducing the growth of enteric pathogens through different mechanisms, involving competitive exclusion or the production of inhibitory molecules (Karami et al., 2017; Mathipa and Thantsha, 2017). We therefore tested the antimicrobial activity exerted by the L. pentosus and L. coryniformis strains against three common pathogens, namely S. enterica serovar Typhimurium, L. monocytogenes and ETEC. The great majority of the Lactobacillus isolates screened in this work resulted to be active against all three pathogens in vitro, although with variable, strain-specific efficacy.

At the end of this in vitro screening, 3 L. coryniformis strains appeared to be good candidate probiotics on the basis of their positive performance under simulated gastro-intestinal digestion, antibiotic susceptibility, and antimicrobial activity. However, only one of these strains was also selected by parallel screening for health-promoting traits in the in vivo nematode model C. elegans. This simplified model organism lives on bacteria as the only food source, but a substantial number of bacterial cells escape the grinding capacity of the worm larynx and can proceed to colonize the nematode gut (Nakagawa et al., 2016). The L. coryniformis H307.6 strain was able to significantly increase C. elegans lifespan as compared to the OP50 control strain, overlapping the effect exerted by the well characterized probiotic strain LGG, while positively impacting also on other well-established aging biomarkers such as pharyngeal pumping rate, body size, brood size, and lipofuscin (Lee et al., 2015). These results further confirm the ability of specific LAB strains to extend nematode lifespan as reported in previous studies (Ikeda et al., 2007; Komura et al., 2013; Nakagawa et al., 2016). Moreover, the L. coryniformis H307.6 displayed health-promoting activities also in host defense against S. enterica serovar Typhimurium, both in vitro (inhibiting pathogen growth as well as competing with pathogen for intestinal cell adhesion), and in vivo (increasing survival of infected worms). It is worth mentioning in this respect that host-pathogen interactions have been investigated in C. elegans for a number of pathogens of human and animal origin (Clark and Hodgkin, 2014), including S. enterica and L. monocytogenes which are able to colonize the worm gut and infect the nematode (Aballay et al., 2000; Thomsen et al., 2006). A second isolate, namely L. pentosus D303.36, was positively selected in C. elegans as a lifespan extending, health-promoting strain. This strain, however, did not display good performance with respect to tolerance to GI tract conditions, and was also resistant to ampicillin and erythromycin. Therefore, further molecular characterization is necessary to exclude potential horizontal transmission of antibiotic resistance before it can be considered a promising probiotic candidate.

On the other hand, L. coryniformis strains H307.1 and H377.3, that were selected as very good performers in the initial in vitro testing screens, were both antibiotic susceptible, as well as capable of inhibiting pathogen growth in the agar double-layer diffusion assay. However, neither one of these two strains could positively impact on C. elegans longevity. Table 5 summarizes the main features displayed by the candidate probiotic strains identified in this study. In light of the recent findings indicating that probiotic capacity of mixed foodborne microbial consortia might be more effective than single strain supplementation (Foligné et al., 2016; Roselli et al., 2017), testing these strains as members of a multistrain probiotic complex could open new avenues for their applications in vegetable food fermentations.

Table 5.

Summary table listing the main features displayed by the candidate probiotic strains identified in this study.

| Species/strain ID | C. elegans | GI tract survival (%) | Antimicrobial activity | Antibiotic resistance | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Longevity | Colonization | In vitro | Caco-2 | C. elegans | Growth on antibiotic* | MIC (mg/ml) | ||

| L. coryniformis H307.1 | − | ND | 70.20 | +++ | ND | ND | S | NA |

| L. coryniformis H377.3 | − | ND | 79.49 | +++ | ND | ND | S | NA |

| L. coryniformis H307.6 | + | + | 73.44 | + | +(Salmonella) | +(Salmonella) | S | NA |

| L. pentosus D303.36 | ++ | + | 51.65 | ++ | +(Salmonella) | +(Salmonella) | R(Amp, Ery) | Amp = 16Ery = 2.5 |

growth in the presence of breakpoint concentration of antibiotics; R, Resistant to the specified antibiotics; S, Susceptible to all tested antibiotics.

MIC, Minimum Inhibitory Concentration, determined only for strains which survived breakpoint concentrations for the specified antibiotics.

ND, Not Determined; NA, Not Applicable.

Conclusions

Extensive in vitro and in vivo characterization of 26 Lactobacillus strains previously isolated from fermented Nocellara del Belice table olives, led to the identification of various potential candidate probiotics. Of these, three L. coryniformis strains displayed good probiotic features in vitro, although only one of them could also exert prolongevity and protective effects in the simplified model organism C. elegans. The GRAS status of Lactobacilli allows to consider their application as starters of fermentation with probiotic added value. However, further validation in in vivo trials with more complex animal or human systems should be performed to gain deeper understanding of their potential health promoting features for human health.

Author contributions

CD and DU conceived and designed the experiments. CD and DU wrote the paper. GP and CP critical revision of manuscript. ES performed animal experiments/treatments. PZ and BG performed microbiological analyses. MR and BG performed cell culture experiments.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Kariklia Pascucci for her kind support in daily lab work, Dr. Domenico Carminati for providing L. monocytogenes OH, L. plantarum ATCC® 14917™ and L. pentosus ATCC® 8041™ bacterial strains. This work was supported in part by a grant from Regione Lazio (Reg. CE1698/2005, Misura 124, Cooperazione per lo sviluppo di nuovi prodotti, processi e tecnologie, nel settore agricolo, alimentare e forestale).

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmicb.2018.00595/full#supplementary-material

References

- Aballay A., Yorgey P., Ausubel F. M. (2000). Salmonella typhimurium proliferates and establishes a persistent infection in the intestine of Caenorhabditis elegans. Curr. Biol. 10, 1539–1542. 10.1016/S0960-9822(00)00830-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abriouel H., Benomar N., Cobo A., Caballero N., Fernández Fuentes M. Á., Pérez-Pulido R., et al. (2012). Characterization of lactic acid bacteria from naturally-fermented Manzanilla Alorena green table olives. Food Microbiol. 32, 308–316. 10.1016/j.fm.2012.07.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abriouel H., Perez Montoro B., Casimiro-Soriguer C. S., Pérez Montoro A. J., Knapp C. W., Caballero Gómez N., et al. (2017). Insight into potential probiotic markers predicted in Lactobacillus pentosus MP-10 genome sequence. Front. Microbiol. 8:891. 10.3389/fmicb.2017.00891 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aminov R. (2017). History of antimicrobial drug discovery: major classes and health impact. Biochem. Pharmacol. 133, 4–19. 10.1016/j.bcp.2016.10.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amund O. D. (2016). Exploring the relationship between exposure to technological and gastrointestinal stress and probiotic functional properties of lactobacilli and bifidobacteria. Can. J. Microbiol. 62, 715–725. 10.1139/cjm-2016-0186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aponte M., Blaiotta G., Croce F. L., Mazzaglia A., Farina V., Settanni L., et al. (2012). Use of selected autochthonous lactic acid bacteria for Spanish-style table olive fermentation. Food Microbiol. 30, 8–16. 10.1016/j.fm.2011.10.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aponte M., Ventorino V., Blaiotta G., Volpe G., Farina V., Avellone G., et al. (2010). Study of green Sicilian table olive fermentations through microbiological, chemical and sensory analyses. Food Microbiol. 27, 162–170. 10.1016/j.fm.2009.09.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Argyri A. A., Lyra E., Panagou E. Z., Tassou C. C. (2013). Fate of Escherichia coli O157:H7, Salmonella Enteritidis and Listeria monocytogenes during storage of fermented green table olives in brine. Food Microbiol. 36, 1–6. 10.1016/j.fm.2013.04.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arroyo-López F. N., Querol A., Bautista-Gallego J., Garrido-Fernandez A. (2008). Role of yeasts in table olive production. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 128, 189–196. 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2008.08.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asahara T., Shimizu K., Takada T., Kado S., Yuki N., Morotomi M., et al. (2011). Protective effect of Lactobacillus casei strain Shirota against lethal infection with multi-drug resistant Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium DT104 in mice. J. Appl. Microbiol. 110, 163–173. 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2010.04884.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker H. C., Tran D. N., Thomas L. V. (2009). Health benefits of probiotics for the elderly: a review. J. Foodserves 20, 250–252. 10.1111/j.1748-0159.2009.00147.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bendali F., Kerdouche K., Hamma-Faradji S., Drider D. (2017). In vitro and in vivo cholesterol lowering ability of Lactobacillus pentosus KF923750. Benef. Microbes 8, 271–280. 10.3920/BM2016.0121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bevilacqua A., Cannarsi M., Gallo M., Sinigaglia M., Corbo M. R. (2010). Characterization and implications of Enterobacter cloacae strains, isolated from Italian table olives “Bella di Cerignola”. J. Food Sci. 75, M53–M60. 10.1111/j.1750-3841.2009.01445.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonatsou S., Tassou C. C., Panagou E. Z., Nychas G. E. (2017). Table olive fermentation using starter cultures with multifunctional potential. Microorganisms 5:30. 10.3390/microorganisms5020030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botta C., Langerholc T., Cencic A., Cocolin L. (2014). In vitro selection and characterization of new probiotic candidates from table olive microbiota. PLoS ONE 9:e94457. 10.1371/journal.pone.0094457 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyle E. C., Finlay B. B. (2003). Bacterial pathogenesis: exploiting cellular adherence. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 15, 633–639. 10.1016/S0955-0674(03)00099-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caro I., Boulenca X., Rousset M., Meunier V., Bourrié M., Julian B., et al. (1995). Characterisation of a newly isolated Caco-2 clone (TC-7), as a model of transport processes and biotransformation of drugs. Int. J. Pharm. 116, 147–158. 10.1016/0378-5173(94)00280-I [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Clark L. C., Hodgkin J. (2014). Commensals, probiotics and pathogens in the Caenorhabditis elegans model. Cell. Microbiol. 16, 27–38. 10.1111/cmi.12234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damaceno Q. S., Souza J. P., Nicoli J. R., Paula R. L., Assis G. B., Figueiredo H. C., et al. (2017). Evaluation of potential probiotics isolated from human milk and colostrum. Probiotics Antimicrob. Proteins 9, 371–379. 10.1007/s12602-017-9270-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de La Puente-Redondo V. A., del Blanco N. G., Gutiérrez-Martín C. B., García-Peña F. J., Rodríguez Ferri E. F. (2000). Comparison of different PCR approaches for typing of Francisella tularensis strains. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38, 1016–1022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devirgiliis C., Caravelli A., Coppola D., Barile S., Perozzi G. (2008). Antibiotic resistance and microbial composition along the manufacturing process of Mozzarella di Bufala Campana. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 128, 378–384. 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2008.09.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Cello F., Fani R. (1996). A molecular strategy for the study of natural bacterial communities by PCR-based techniques. Minerva Biotecnol. 8, 126–134. [Google Scholar]

- Dicks L. M., Botes M. (2010). Probiotic lactic acid bacteria in the gastro-intestinal tract: health benefits, safety and mode of action. Benef. Microbes 1, 11–29. 10.3920/BM2009.0012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EFSA (2012). Guidance on the assessment of bacterial susceptibility to antimicrobials of human and veterinary importance. EFSA J. 10:2740. 10.2903/j.efsa.2012.2740 [Google Scholar]

- FAO/WHO (2006). Probiotics in Food. Health and nutritional properties and guidelines for evaluation. Available online at: http://www.fao.org/food/food-safety-quality/a-z-index/probiotics/en/

- Foligné B., Parayre S., Cheddani R., Famelart M. H., Madec M. N., Plé C., et al. (2016). Immunomodulation properties of multi-species fermented milks. Food Microbiol. 53, 60–69. 10.1016/j.fm.2015.04.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrigues C., Johansen E., Crittenden R. (2013). Pangenomics–an avenue to improved industrial starter cultures and probiotics. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 24, 187–191. 10.1016/j.copbio.2012.08.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giraffa G., Chanishvili N., Widyastuti Y. (2010). Importance of lactobacilli in food and feed biotechnology. Res. Microbiol. 161, 480–487. 10.1016/j.resmic.2010.03.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granato D., Branco G. F., Nazzaro F., Cruz A. G., Faria J. A. F. (2010). Functional foods and non-dairy probiotic food development: trend, concepts, and products. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Saf. 9, 292–302. 10.1111/j.1541-4337.2010.00110.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hegarty J. W., Guinane C. M., Ross R. P., Hill C., Cotter P. D. (2016). Bacteriocin production: a relatively unharnessed probiotic trait? F1000Res 5, 2587. 10.12688/f1000research.9615.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heperkan D. (2013). Microbiota of table olive fermentations and criteria of selection for their use as starters. Front. Microbiol. 4:143. 10.3389/fmicb.2013.00143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill C., Guarner F., Reid G., Gibson G. R., Merenstein D. J., Pot B., et al. (2014). Expert consensus document. The International Scientific Association for Probiotics and Prebiotics consensus statement on the scope and appropriate use of the term probiotic. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 11, 506–514. 10.1038/nrgastro.2014.66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurtado A., Reguant C., Bordons A., Rozès N. (2012). Lactic acid bacteria from fermented table olives. Food Microbiol. 31, 1–8. 10.1016/j.fm.2012.01.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikeda T., Yasui C., Hoshino K., Arikawa K., Nishikawa Y. (2007). Influence of lactic acid bacteria on longevity of Caenorhabditis elegans and host defense against salmonella enterica serovar enteritidis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73, 6404–6409. 10.1128/AEM.00704-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imperial I. C., Ibana J. A. (2016). Addressing the antibiotic resistance problem with probiotics: reducing the risk of its double-edged sword effect. Front. Microbiol. 7:1983. 10.3389/fmicb.2016.01983 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karami S., Roayaei M., Hamzavi H., Bahmani M., Hassanzad-Azar H., Leila M., et al. (2017). Isolation and identification of probiotic Lactobacillus from local dairy and evaluating their antagonistic effect on pathogens. Int. J. Pharm. Investig. 7, 137–141. 10.4103/jphi.JPHI_8_17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y., Mylonakis E. (2012). Caenorhabditis elegans immune conditioning with the probiotic bacterium Lactobacillus acidophilus strain NCFM enhances gram-positive immune responses. Infect. Immun. 80, 2500–2508. 10.1128/IAI.06350-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Köhler H., Sakaguchi T., Hurley B. P., Kase B. A., Reinecker H. C., McCormick B. A. (2007). Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium regulates intercellular junction proteins and facilitates transepithelial neutrophil and bacterial passage. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 293, G178–G187. 10.1152/ajpgi.00535.2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komura T., Ikeda T., Yasui C., Saeki S., Nishikawa Y. (2013). Mechanism underlying prolongevity induced by bifidobacteria in Caenorhabditis elegans. Biogerontology 14, 73–87. 10.1007/s10522-012-9411-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lara-Villoslada F., Sierra S., Martín R., Delgado S., Rodríguez J. M., Olivares M., et al. (2007). Safety assessment of two probiotic strains, Lactobacillus coryniformis CECT5711 and Lactobacillus gasseri CECT5714. J. Appl. Microbiol. 103, 175–184. 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2006.03225.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J., Kwon G., Lim Y. H. (2015). Elucidating the mechanism of weissella-dependent lifespan extension in Caenorhabditis elegans. Sci. Rep. 5:17128. 10.1038/srep17128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liévin-Le Moal V., Amsellem R., Servin A. L., Coconnier M. H. (2002). Lactobacillus acidophilus (strain LB) from the resident adult human gastrointestinal microflora exerts activity against brush border damage promoted by a diarrhoeagenic Escherichia coli in human enterocyte-like cells. Gut 50, 803–811. 10.1136/gut.50.6.803 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magnusson J., Schnürer J. (2001). Lactobacillus coryniformis subsp. coryniformis strain Si3 produces a broad-spectrum proteinaceous antifungal compound. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67, 1–5. 10.1128/AEM.67.1.1-5.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathipa M. G., Thantsha M. S. (2017). Probiotic engineering: towards development of robust probiotic strains with enhanced functional properties and for targeted control of enteric pathogens. Gut Pathog. 9, 28. 10.1186/s13099-017-0178-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montoro B. P., Benomar N., Lavilla Lerma L., Castillo Gutiérrez S., Gálvez A., Abriouel H. (2016). Fermented alorena table olives as a source of potential probiotic Lactobacillus pentosus strains. Front. Microbiol. 7:1583. 10.3389/fmicb.2016.01583 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakagawa H., Shiozaki T., Kobatake E., Hosoya T., Moriya T., Sakai F., et al. (2016). Effects and mechanisms of prolongevity induced by Lactobacillus gasseri SBT2055 in Caenorhabditis elegans. Aging Cell 15, 227–236. 10.1111/acel.12431 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neuhaus K., Lamparter M. C., Zölch B., Landstorfer R., Simon S., Spanier B., et al. (2017). Probiotic Enterococcus faecalis symbioflor® down regulates virulence genes of EHEC in vitro and decrease pathogenicity in a Caenorhabditis elegans model. Arch. Microbiol. 199, 203–213. 10.1007/s00203-016-1291-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olivares M., Díaz-Ropero M. A., Gómez N., Lara-Villoslada F., Sierra S., Maldonado J. A., et al. (2006). Oral administration of two probiotic strains, Lactobacillus gasseri CECT5714 and Lactobacillus coryniformis CECT5711, enhances the intestinal function of healthy adults. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 107, 104–111. 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2005.08.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park M. R., Oh S., Son S. J., Park D. J., Kim S. H., et al. (2015). Bacillus licheniformis isolated from Traditional Korean Food resources enhances the longevity of Caenorhabditis elegans through serotonin signaling. J. Agric. Food Chem. 63, 10227–10233. 10.1021/acs.jafc.5b03730 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park M. R., Yun H. S., Son S. J., Oh S., Kim Y. (2014). Short communication: development of a direct in vivo screening model to identify potential probiotic bacteria using Caenorhabditis elegans. J. Dairy Sci. 97, 6828–6834. 10.3168/jds.2014-8561 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ranadheera R. D. C. S., Baines S. K., Adams M. C. (2010). Importance of food in probiotic efficacy. Food Res. Int. 43, 1–7. 10.1016/j.foodres.2009.09.009 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Resta-Lenert S., Barrett K. E. (2003). Live probiotics protect intestinal epithelial cells from the effects of infection with enteroinvasive Escherichia coli (EIEC). Gut 52, 988–997. 10.1136/gut.52.7.988 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritchie M. L., Romanuk T. N. (2012). A meta-analysis of probiotic efficacy for gastrointestinal diseases. PLoS ONE 7:e34938. 10.1371/journal.pone.0034938 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roselli M., Devirgiliis C., Zinno P., Guantario B., Finamore A., Rami R., et al. (2017). Impact of supplementation with a food-derived microbial community on obesity-associated inflammation and gut microbiota composition. Genes Nutr. 12:25. 10.1186/s12263-017-0583-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roselli M., Finamore A., Britti M. S., Mengheri E. (2006). Probiotic bacteria Bifidobacterium animalis MB5 and Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG protect intestinal Caco-2 cells from the inflammation-associated response induced by enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli K88. Br. J. Nutr. 95, 1177–1184. 10.1079/BJN20051681 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sambuy Y., De Angelis I., Ranaldi G., Scarino M. L., Stammati A., Zucco F. (2005). The Caco-2 cell line as a model of the intestinal barrier: influence of cell and culture-related factors on Caco-2 cell functional characteristics. Cell Biol. Toxicol. 21, 1–26. 10.1007/s10565-005-0085-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saulnier D. M., Spinler J. K., Gibson G. R., Versalovic J. (2009). Mechanisms of probiosis and prebiosis: considerations for enhanced functional foods. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 20, 135–141. 10.1016/j.copbio.2009.01.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomsen L. E., Slutz S. S., Tan M. W., Ingmer H. (2006). Caenorhabditis elegans is a model host for Listeria monocytogenes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72, 1700–1701. 10.1128/AEM.72.2.1700-1701.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torriani S., Felis G. E., Dellaglio F. (2001). Differentiation of Lactobacillus plantarum, L. pentosus, and L. paraplantarum by recA gene sequence analysis and multiplex PCR assay with recA gene-derived primers. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67, 3450–3454. 10.1128/AEM.67.8.3450-3454.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uccelletti D., Pascoli A., Farina F., Alberti A., Mancini P., Hirschberg C. B., et al. (2008). APY-1, a novel Caenorhabditis elegans apyrase involved in unfolded protein response signalling and stress responses. Mol. Biol. Cell 19, 1337–1345. 10.1091/mbc.E07-06-0547 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uccelletti D., Zanni E., Marcellini L., Palleschi C., Barra D., Mangoni M. L. (2010). Anti-pseudomonas activity of frog skin antimicrobial peptides in a Caenorhabditis elegans infection model: a plausible mode of action in vitro and in vivo. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 54, 3853–3860. 10.1128/AAC.00154-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vizoso Pinto M. G., Franz C. M., Schillinger U., Holzapfel W. H. (2006). Lactobacillus spp. with in vitro probiotic properties from human faeces and traditional fermented products. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 109, 205–214. 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2006.01.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zanni E., Laudenzi C., Schifano E., Palleschi C., Perozzi G., Uccelletti D., et al. (2015). Impact of a complex food microbiota on energy metabolism in the model organism Caenorhabditis elegans. Biomed Res. Int. 2015:621709. 10.1155/2015/621709 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zanni E., Schifano E., Motta S., Sciubba F., Palleschi C., Mauri P., et al. (2017). Combination of metabolomic and proteomic analysis revealed different features among Lactobacillus delbrueckii subspecies bulgaricus and lactis strains while in vivo testing in the model organism Caenorhabditis elegans highlighted probiotic properties. Front. Microbiol. 8:1206. 10.3389/fmicb.2017.01206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Y., Qin H., Zhang M., Shen T., Chen H., Ma Y., et al. (2010). Lactobacillus plantarum inhibits intestinal epithelial barrier dysfunction induced by unconjugated bilirubin. Br. J. Nutr. 104, 390–401. 10.1017/S0007114510000474 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zinno P., Guantario B., Perozzi G., Pastore G., Devirgiliis C. (2017). Impact of NaCl reduction on lactic acid bacteria during fermentation of Nocellara del Belice table olives. Food Microbiol. 63, 239–247. 10.1016/j.fm.2016.12.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data