Abstract

Malaria outbreaks have been reported in recent years in the Colombian Amazon region, malaria has been re-emerging in areas where it was previously controlled. Information from malaria transmission networks and knowledge about the population characteristics influencing the dispersal of parasite species is limited. This study aimed to determine the distribution patterns of Plasmodium vivax, P. malariae and P. falciparum single and mixed infections, as well as the significant socio-spatial groupings relating to the appearance of such infections. An active search in 57 localities resulted in 2,106 symptomatic patients being enrolled. Parasitaemia levels were assessed by optical microscopy, and parasites were detected by PCR. The association between mixed infections (in 43.2% of the population) and socio-spatial factors was modelled using logistic regression and multiple correspondence analyses. P. vivax occurred most frequently (71.0%), followed by P. malariae (43.2%), in all localities. The results suggest that a parasite density-dependent regulation model (with fever playing a central role) was appropriate for modelling the frequency of mixed species infections in this population. This study highlights the under-reporting of Plasmodium spp. mixed infections in the malaria-endemic area of the Colombian Amazon region and the association between causative and environmental factors in such areas.

Introduction

Malaria is considered as the parasitic disease that has the greatest impact on public health1. Plasmodium spp. infection becomes perpetuated in a cycle of disease and poverty, contributing towards affected individuals’ worsening quality of life and limiting the possibility of eradicating such infections2.

Malaria is transmitted by female mosquitoes from the genus Anopheles, with mammals being the definitive host1,3. Six species from the genus Plasmodium have been described as causing malaria in human beings: P. falciparum, P. vivax, P. malariae, P. ovale curtisi, P. ovale wallikeri and P. knowlesi4,5, with Plasmodium spp. being endemic in 91 countries and causing 212 million cases of infection per year (429,000 leading to death)6.

Current mitigation measures in disease-endemic countries have not had the desired impact since an increase in malaria cases has been reported for countries such as Colombia, where 55,866 cases were confirmed in 2015 (annual parasite index: 5.4 cases per 1,000 inhabitants)7,8. Colombia thus accounts for 10% of cases of malaria in the Americas9–11, with Colombia’s Amazon region being the focus of an outbreak of malaria during the last few years7,12.

The Amazon basin covering a large part of southern Colombia (108,951 km2) is a major transmission and disease load foci13,14, which operates relatively independently from other Colombian regions. The Amazon region’s habitat diversity and its own climatic characteristics (seasonal rainfall effects) determine vector presence and abundance (i.e. Anopheles benarrochi, Anopheles oswaldoi, Anopheles darlingi). Such vectors are anthropophilic and highly efficient regarding parasite transmission and have facilitated the increase in cases of malaria amongst the region’s inhabitants, together with the demographics of human settlements, and clinical and housing conditions in the region and their related dynamics14,15.

Risk factors for acquiring malaria have been described on different levels (genetic, social determinants and environmental) and influence exposure to parasitic infection, its course and outcomes16–19. These factors also facilitate infection by more than one Plasmodium spp. (mixed-species malaria); however, these mixed-species are currently being under-diagnosed given the use of conventional techniques10. Little is currently known regarding the biology and establishment of Plasmodium mixed infections, but insight into the frequency of mixed-species infections in the population and the factors affecting their transmission is essential for developing effective disease elimination measures20,21. The factors involved in malaria transmission and those influencing mixed Plasmodium spp. species infection in highly endemic regions need to be determined, particularly at a time when rapid climatic changes can modify host-vector-pathogen relationship dynamics.

This study aimed to establish the frequency of three Plasmodium spp. within the population, determine the distribution of mixed infections and identify infected patient profiles in the Colombian Amazon region.

Results

Characteristics of the population being analysed

Of the 2,106 patients invited to participate in the study, 5.3% (n = 111) were excluded due to negative results with human β-globin gene amplification; 1,995 subjects thus became the object of statistical analysis. The sampling region was divided into areas in accordance with the population characteristics (Fig. 1); 344 samples were taken in area 1, 257 samples in area 2, 566 samples in area 3 and 828 samples in area 4 (Additional file 1: Table S1). The average age of the population was 26.6 years (SD: 19.8 years) and 48.2% (n = 961) reported a previous episode of malaria, mainly those living in area 4 (n = 441). Table 1 provides the distribution of sociodemographic characteristics amongst the population in accordance with the Plasmodium spp. infection stage (as determined by molecular biology).

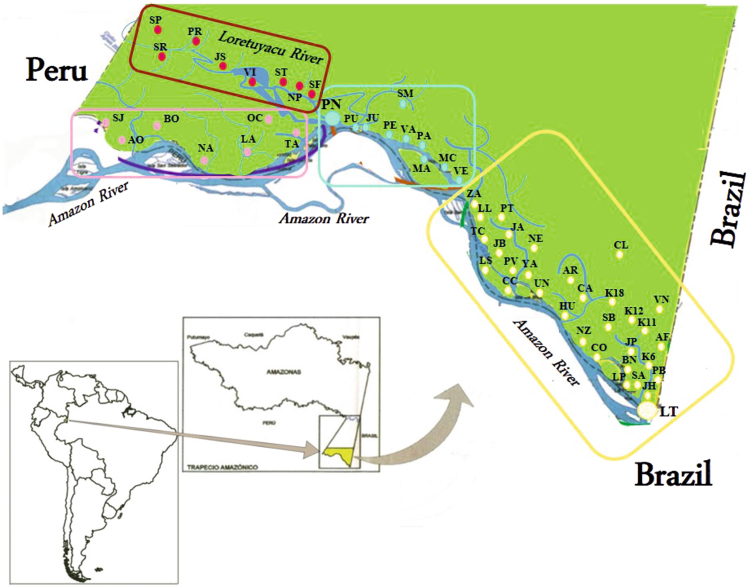

Figure 1.

Geographical locations of the 57 localities where samples were collected (this map was modified from a map downloaded from the Instituto Geográfico Agustín Codazzi, IGAC)60,61. Images are freely accessible and modifiable in accordance with IGAC policies.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics of the sample population.

| Variable | Uninfected (n = 245) | Single infection (n = 906) | Mixed infection (n = 844) | P. vivax (n = 1,412) | P. falciparum (n = 432) | P. malariae (n = 862) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Age in years | ||||||||||||

| ≤5 | 54 | 22 | 138 | 15.2 | 112 | 13.3 | 190 | 13.5 | 67 | 15.5 | 118 | 13.7 |

| 6–12 | 38 | 15.5 | 174 | 19.2 | 165 | 19.5 | 269 | 19.1 | 89 | 20.6 | 170 | 19.7 |

| 13–18 | 17 | 6.9 | 88 | 9.7 | 90 | 10.7 | 150 | 10.6 | 37 | 8.6 | 94 | 10.9 |

| 19–30 | 51 | 20.8 | 164 | 18.1 | 152 | 18 | 256 | 18.1 | 82 | 19 | 153 | 17.7 |

| 31–60 | 75 | 30.6 | 275 | 30.4 | 263 | 31.2 | 436 | 30.9 | 121 | 28 | 273 | 31.7 |

| ≥60 | 10 | 4.1 | 67 | 7.4 | 62 | 7.3 | 111 | 7.9 | 36 | 8.3 | 54 | 6.3 |

| Gender | ||||||||||||

| Male | 125 | 51 | 444 | 49 | 444 | 52.6 | 689 | 48.8 | 227 | 52.5 | 446 | 51.7 |

| Female | 120 | 49 | 462 | 51 | 400 | 47.4 | 723 | 51.2 | 205 | 47.5 | 416 | 48.3 |

| Sampling area | ||||||||||||

| Area 1 | 49 | 20 | 166 | 18.3 | 129 | 15.3 | 246 | 17.4 | 18 | 4.2 | 164 | 19 |

| Area 2 | 21 | 8.6 | 102 | 11.3 | 134 | 15.9 | 197 | 13.9 | 84 | 19.4 | 109 | 12.7 |

| Area 3 | 62 | 25.3 | 271 | 29.9 | 233 | 27.6 | 404 | 28.6 | 123 | 28.5 | 252 | 29.2 |

| Area 4 | 113 | 46.1 | 367 | 40.5 | 348 | 41.2 | 565 | 40 | 207 | 47.9 | 337 | 39.1 |

| Settlement type | ||||||||||||

| Rural | 224 | 91.4 | 791 | 87.3 | 755 | 89.5 | 1,350 | 95.6 | 428 | 99.1 | 828 | 96.1 |

| Urban | 21 | 8.6 | 115 | 12.7 | 89 | 10.5 | 62 | 4.4 | 4 | 0.9 | 34 | 3.9 |

| Stagnant water nearby | ||||||||||||

| No | 90 | 36.7 | 555 | 61.3 | 539 | 63.9 | 893 | 63.2 | 285 | 66 | 533 | 61.8 |

| Yes | 155 | 63.3 | 351 | 38.7 | 305 | 36.1 | 519 | 36.8 | 147 | 34 | 329 | 38.2 |

| Insecticide use | ||||||||||||

| No | 208 | 84.9 | 783 | 86.4 | 752 | 89.1 | 1,232 | 87.3 | 397 | 91.9 | 759 | 88.1 |

| Yes | 37 | 15.1 | 123 | 13.6 | 92 | 10.9 | 180 | 12.7 | 35 | 8.1 | 103 | 11.9 |

| Mosquito net use | ||||||||||||

| No | 13 | 5.3 | 53 | 5.8 | 48 | 5.7 | 83 | 5.9 | 17 | 3.9 | 52 | 6 |

| Yes | 232 | 94.7 | 853 | 94.2 | 796 | 94.3 | 1,329 | 94.1 | 415 | 96.1 | 810 | 94 |

| Public gas supply | ||||||||||||

| No | 230 | 93.9 | 854 | 94.3 | 808 | 95.7 | 1,337 | 94.7 | 421 | 97.5 | 821 | 95.2 |

| Yes | 15 | 6.1 | 52 | 5.7 | 36 | 4.3 | 75 | 5.3 | 11 | 2.5 | 41 | 4.8 |

| Public electricity supply | ||||||||||||

| No | 18 | 7.3 | 78 | 8.6 | 100 | 11.8 | 147 | 10.4 | 39 | 9 | 107 | 12.4 |

| Yes | 227 | 92.7 | 828 | 91.4 | 744 | 88.2 | 1,265 | 89.6 | 393 | 91 | 755 | 87.6 |

| Public water supply | ||||||||||||

| No | 207 | 84.5 | 613 | 67.7 | 554 | 65.6 | 926 | 65.6 | 310 | 71.8 | 560 | 65 |

| Yes | 38 | 15.5 | 293 | 32.3 | 290 | 34.4 | 486 | 34.4 | 122 | 28.2 | 302 | 35 |

| Sewerage service | ||||||||||||

| No | 207 | 89.5 | 666 | 78.6 | 636 | 79.2 | 1,039 | 77.3 | 347 | 81.6 | 641 | 78.2 |

| Yes | 28 | 10.5 | 190 | 21.4 | 175 | 20.8 | 305 | 22.7 | 78 | 78.4 | 179 | 21.8 |

Molecular biology was used for determining the Plasmodium infection stage and species.

Detecting Plasmodium spp. by conventional microscopy and PCR

By analysing thick blood smears (TBS), 37% (n = 737/1,995) of the population were identified as positive for Plasmodium spp., 31.3% (n = 625/1,995) for P. vivax, 6.4% (n = 128/1,995) for P. falciparum and less than 1% (n = 16/1,995) had mixed-species infections (Additional file 2: Fig. S1a). Parasitaemia varied from 32 to 85,320 parasites/µL blood (mean: 10,100; SD: 11,603), being higher in P. vivax (mean: 10,585; SD: 11,920) than in P. falciparum (mean: 7,752; SD: 9,099).

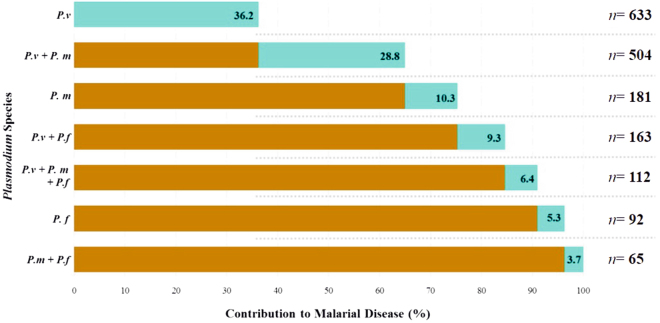

Regarding parasite DNA detection, 88% (n = 1,750/1,995) of the target population were infected with Plasmodium spp., with P. vivax being the most prevalent species (71.0%; n = 1,412/1,995), followed by P. malariae (43.2%; n = 862/1,995) and P. falciparum (21.7%; n = 432/1,995). Mixed infection events (simultaneous infection by ≥2 species) were found in 43.2% (n = 844/1,995) of the target population (Additional file 2: Fig. S1b), with the P. vivax/P. malariae combination being the most frequently detected (n = 504/1,995) (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Cumulative frequency of Plasmodium species and their contribution to malaria in 1,750 people in whom parasitic DNA was identified using molecular techniques. P.v = Plasmodium vivax, P.m = Plasmodium malariae and P.f = Plasmodium falciparum.

It was found that 75% of the cases were infected with P. vivax and P. malariae (Fig. 2). Parasite frequency ranged from 82% to 100% (Additional file 3: Fig. S2a) when evaluating parasite infection with respect to age and P. vivax was the most prevalent species amongst all age groups, showing a greater frequency in the 31–60-year-old age group (p = 0.002; Chi2 tests) (Table 1; Additional file 3: Fig. S2b).

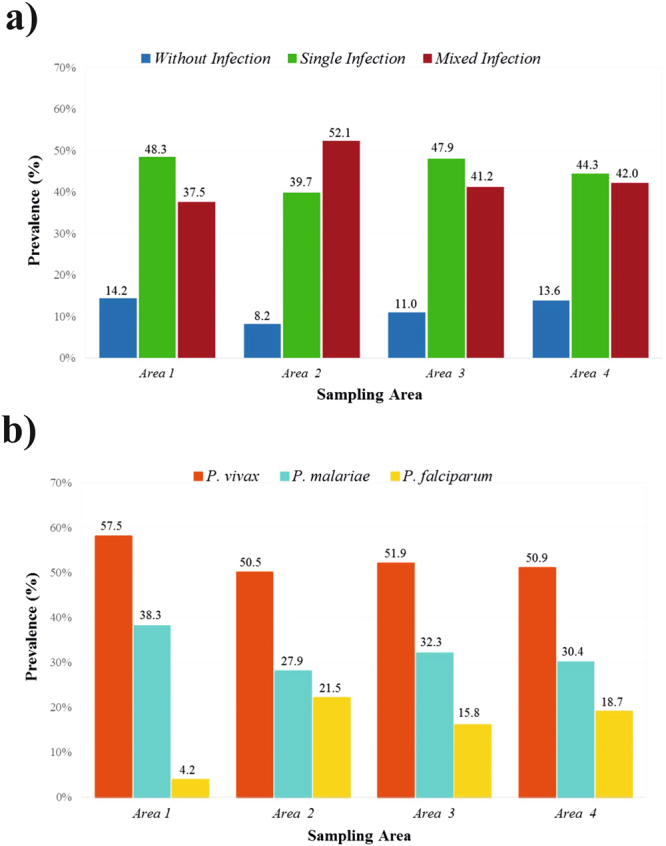

Evaluating the sampling areas and the types of settlement

Additional analysis evaluated the parasite infection status (single and mixed), the mean rate of Plasmodium spp. parasitaemia and the distribution with respect to the area sampled. Sampling area 1 had the highest single infection frequency (48.3%) (not statistically significant: p = 0.561; Chi2 test); mixed infections appeared most frequently in area 2 (p = 0.001; Chi2 test) (Fig. 3a). Mean parasitaemia levels were lower in cases of single infection (9,854 parasites/µL) than in mixed infections (10,394 parasites/µL), but this difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.533; T-test) (Additional file 4: Fig. S3a). However, parasitaemia varied significantly depending on the area being sampled (p = 0.026; ANOVA test). Bonferroni test correction showed significant differences between areas 3 and 4 (p = 0.022) (Additional file 4: Fig. S3b).

Figure 3.

Relative frequency of parasite infection and Plasmodium spp. distribution with respect to the area sampled [area 1 (n = 344), area 2 (n = 257), area 3 (n = 566) and area 4 (n = 828)]. Part (a) shows the distribution of parasite infection frequency with respect to the Plasmodium spp. infection status. Blue represents the uninfected target population. Green represents the proportion of the target population infected by a single species. Dark red represents the proportion of the target population with a mixed species infection. Part (b) shows the relative frequency of Plasmodium spp.

The results of the analysis of Plasmodium spp. distribution with respect to area showed that P. vivax had the greatest frequency (greater than 65%) in almost all localities, except for P. vivax in Punta Brava and Yaguas (Additional file 5: Table S3) and P. malariae (absent in seven localities evaluated) (Additional file 5: Table S3) (40.7% to 47.7% relative frequencies). P. falciparum prevalence was significantly lower in area 1 relative to all other (p = 0.001; Fisher’s exact test) (Fig. 3b).

Parasite infection was evaluated with respect to the type of settlement; Leticia and Puerto Nariño are urban settlements; the remaining localities are rural. There were similar infection percentages for all types of settlement; however, the parasite density index (PDI) was higher for rural areas (index: 57.8). P. falciparum infection was mostly restricted to rural settlements (Additional file 6: Table S3).

Plasmodium spp. infection profiles

A clinical profile was created for each participant based on the symptoms reported in a survey conducted during sampling. Vomiting (p = 0.018; Fisher’s exact test) and diarrhoea (p = 0.005; Fisher’s exact test) occurred most frequently in the study population with single Plasmodium spp. infections, whereas severe headache was most frequently reported in the population with mixed-species infections (p = 0.001; Fisher’s exact test) (Additional file 7: Fig. S4). The distribution of symptoms was similar for all species of infecting Plasmodium, with fever being the most frequently reported symptom amongst the three species (89% to 91%) and a rash being the least frequently reported symptom in the sample population (2.1% to 3.2%) (Additional file 8: Fig. S5).

Logistic regression was used to identify the association between the variables evaluated (age, area, parasitaemia, access to basic services (public water and electricity supply, sewerage service), nearby water stagnations, use of mosquito nets and use of insecticides) and the presence of mixed-species infection. Patients having 2,000 to 4,999 parasites/µL blood parasitaemia [adjusted odds ratio (aOR) 0.61: 0.38–0.98, 95% confidence interval (CI)] or 5,000 to 9,999 parasites/µL blood parasitaemia (aOR 0.48: 0.29–0.77, 95% CI) had a lower probability of acquiring a mixed infection. No significant associations were observed for the other variables included in the model (Table 2).

Table 2.

Risk factors associated with mixed infections.

| Variable | OR Adjusted | 95% CI | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age in years | |||

| ≤5 | 0.91 | 0.52–1.59 | 0.767 |

| 6–12 | 1.11 | 0.57–2.14 | 0.749 |

| 13–18 | 1.12 | 0.62–2.00 | 0.703 |

| 19–30 | 1.13 | 0.66–1.95 | 0.636 |

| 31–60 | Reference | ||

| ≥60 | 0.60 | 0.26–1.30 | 0.237 |

| Gender | |||

| Male | Reference | ||

| Female | 1.17 | 0.85–1.61 | 0.307 |

| Sampling area | |||

| Area 1 | 0.93 | 0.59–1.48 | 0.787 |

| Area 2 | 1.43 | 0.84–2.48 | 0.183 |

| Area 3 | 0.43 | 0.14–1.30 | 0.138 |

| Area 4 | Reference | ||

| Stagnant water nearby | |||

| No | Reference | ||

| Yes | 0.98 | 0.67–1.38 | 0.926 |

| Insecticide use | |||

| No | Reference | ||

| Yes | 0.91 | 0.77–1.07 | 0.284 |

| Mosquito net use | |||

| No | Reference | ||

| Yes | 0.77 | 0.39–1.52 | 0.463 |

| Public gas supply | |||

| No | Reference | ||

| Yes | 0.83 | 0.57–1.20 | 0.332 |

| Public electricity supply | |||

| No | Reference | ||

| Yes | 0.81 | 0.46–1.42 | 0.472 |

| Public water supply | |||

| No | Reference | ||

| Yes | 1.55 | 0.88–2.71 | 0.122 |

| Sewerage service | |||

| No | Reference | ||

| Yes | 0.61 | 0.34–1.11 | 0.112 |

| Fever | |||

| No | Reference | ||

| Yes | 0.91 | 0.41–2.04 | 0.831 |

| Parasitaemia | |||

| 1–1,999 | 0.90 | 0.58–1.37 | 0.629 |

| 2,000–4,999 | 0.61 | 0.38–0.98 | 0.043 |

| 5,000–9,999 | 0.48 | 0.29–0.77 | 0.003 |

| >9,999 | Reference | ||

Values shown in bold p < 0.05. OR adjusted for inhabitants’ age and the urban or rural area in which they reside. Parasitaemia as determined from thick blood smears, and housing conditions, such as the availability of sewerage, drinkable water, gas and electricity services and whether there was stagnant water nearby and whether mosquito nets and insecticides were being used.

Analysing the strength of the association between sociodemographic, clinical and laboratory variables (as previously mentioned), and the combination of parasite species revealed positive associations between area 1 and mixed P. vivax and P. malariae infections (aOR 2.13: 1.33–3.42, 95% CI), access to a public water supply and mixed P. malariae and P. falciparum infections (aOR 6.90: 4.98–8.28, 95% CI) and triple infections (simultaneous infection by the three species being evaluated) (aOR 3.05: 1.20–7.74, 95% CI). Variables showing less significant associations were parasitaemia (5,000 to 9,999 parasites/µL blood) in P. malariae and P. falciparum infections (aOR 0.18: 0.35–0.93, 95% CI) and triple infection events with parasitaemia higher than 2,000 parasites/µL blood and area 1 (Additional file 9: Table S4).

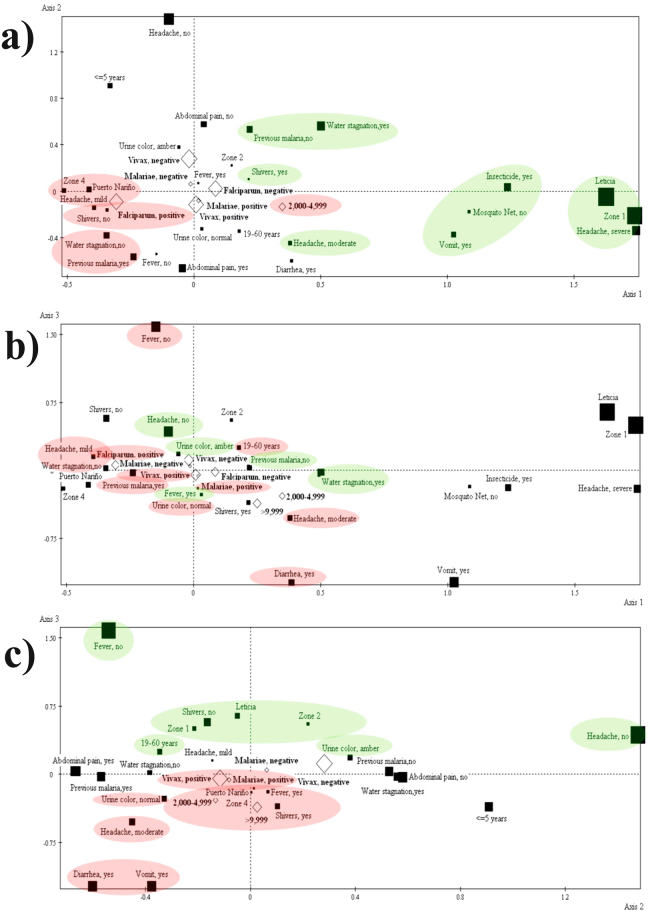

Multiple correspondence analysis (MCA) was used for identifying Plasmodium spp. infection profiles by compiling clinical and sociodemographic variables (Tables 3 and 4). Three main axes emerged after analysing the change in inertia in the histogram showing the eigenvalues of the active variables (Table 5 and Fig. 4). Three profiles were constructed around these axes (epidemiological and clinical variables related to P. falciparum infection, those related to triple infection (P. falciparum, P. vivax and P. malariae) and those related to double infection by P. vivax and P. malariae) (Table 5 and Fig. 4).

Table 3.

Contribution, cosine squared and active variable test values.

| Active variables | n | Contribution | Cosine squared | Test value | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Axis 1 | Axis 2 | Axis 3 | Axis 1 | Axis 2 | Axis 3 | Axis 1 | Axis 2 | Axis 3 | ||

| Age in years | ||||||||||

| ≤5 | 304 | 0.65 | 6.97 | 1.44 | 0.02 | 0.15 | 0.02 | −6.26 | 17.21 | −6.89 |

| 6–12 | 377 | 0.62 | 1.97 | 1.57 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.03 | −6.27 | 9.35 | −7.35 |

| 13–18 | 195 | 0.24 | 0.21 | 0.68 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 3.65 | −2.90 | −4.61 |

| 19–60 | 976 | 0.61 | 3.22 | 2.13 | 0.03 | 0.11 | 0.06 | 7.83 | −15.07 | 10.79 |

| >60 | 143 | 0.02 | 0.82 | 0.88 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.01 | −1.13 | −5.63 | 5.16 |

| Gender | ||||||||||

| Male | 1,013 | 0.02 | 0.06 | 0.80 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 1.54 | 2.12 | −6.73 |

| Female | 982 | 0.02 | 0.06 | 0.82 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.02 | −1.54 | −2.12 | 6.73 |

| Origin | ||||||||||

| Puerto Nariño | 401 | 5.29 | 0.01 | 1.49 | 0.67 | 0.00 | 0.10 | −36.59 | 1.17 | −14.30 |

| Leticia | 1,591 | 20.91 | 0.03 | 5.89 | 0.67 | 0.00 | 0.10 | 36.48 | −1.12 | 14.32 |

| Area | ||||||||||

| 1 | 344 | 20.42 | 0.44 | 3.04 | 0.63 | 0.01 | 0.05 | 35.48 | −4.35 | 10.14 |

| 2 | 257 | 0.11 | 0.34 | 2.79 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.05 | 2.55 | 3.77 | 9.47 |

| 3 | 566 | 1.56 | 0.01 | 1.29 | 0.06 | 0.00 | 0.03 | −10.53 | 0.70 | −7.09 |

| 4 | 828 | 4.27 | 0.00 | 1.25 | 0.19 | 0.00 | 0.03 | −19.30 | 0.14 | −7.73 |

| Mosquito net use | ||||||||||

| No | 114 | 2.64 | 0.10 | 0.13 | 0.07 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 11.95 | −1.97 | −1.95 |

| Yes | 1,881 | 0.16 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.07 | 0.00 | 0.00 | −11.95 | 1.97 | 1.95 |

| Insecticide use | ||||||||||

| No | 1,743 | 1.10 | 0.00 | 0.05 | 0.22 | 0.00 | 0.00 | −21.05 | −0.56 | 3.28 |

| Yes | 252 | 7.59 | 0.01 | 0.34 | 0.22 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 21.05 | 0.56 | −3.28 |

| Stagnant water nearby | ||||||||||

| No | 1,184 | 2.75 | 4.82 | 0.02 | 0.17 | 0.21 | 0.00 | −18.57 | −20.68 | 1.03 |

| Yes | 811 | 4.01 | 7.04 | 0.02 | 0.17 | 0.21 | 0.00 | 18.57 | 20.68 | −1.03 |

| Fever | ||||||||||

| No | 223 | 0.10 | 1.81 | 19.92 | 0.00 | 0.04 | 0.31 | −2.34 | −8.56 | 25.05 |

| Yes | 1,772 | 0.01 | 0.23 | 2.51 | 0.00 | 0.04 | 0.31 | 2.34 | 8.56 | −25.05 |

| Headache | ||||||||||

| No | 285 | 0.05 | 17.26 | 1.86 | 0.00 | 0.36 | 0.03 | −1.79 | 26.93 | 7.79 |

| Mild | 1,082 | 3.28 | 0.62 | 0.84 | 0.18 | 0.02 | 0.03 | −19.12 | −7.00 | 7.15 |

| Moderate | 471 | 1.33 | 2.64 | 4.68 | 0.04 | 0.06 | 0.09 | 9.44 | −11.16 | −13.10 |

| Severe | 157 | 9.40 | 0.51 | 0.24 | 0.26 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 22.81 | −4.45 | −2.70 |

| Vomiting | ||||||||||

| No | 1,769 | 0.60 | 0.11 | 1.58 | 0.13 | 0.02 | 0.20 | −16.37 | 5.99 | 19.75 |

| Yes | 226 | 4.66 | 0.88 | 12.35 | 0.13 | 0.02 | 0.20 | 16.37 | −5.99 | −19.75 |

| Shivering | ||||||||||

| No | 771 | 1.77 | 0.57 | 8.96 | 0.07 | 0.02 | 0.20 | −12.14 | −5.81 | 20.22 |

| Yes | 1,224 | 1.12 | 0.36 | 5.64 | 0.07 | 0.02 | 0.20 | 12.14 | 5.81 | −20.22 |

| Diarrhoea | ||||||||||

| No | 1,809 | 0.06 | 0.19 | 1.05 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.16 | −5.54 | 8.61 | 17.76 |

| Yes | 186 | 0.55 | 1.87 | 10.22 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.16 | 5.54 | −8.61 | −17.76 |

| Urine colour | ||||||||||

| Amber | 982 | 0.07 | 3.92 | 1.12 | 0.00 | 0.14 | 0.03 | −2.62 | 16.68 | 7.87 |

| Brown | 104 | 0.16 | 1.48 | 1.70 | 0.00 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 2.95 | −7.50 | 7.09 |

| Normal | 909 | 0.02 | 2.71 | 2.38 | 0.00 | 0.09 | 0.06 | 1.31 | −13.40 | −11.06 |

| Abdominal pain | ||||||||||

| No | 1,066 | 0.03 | 9.95 | 0.05 | 0.00 | 0.39 | 0.00 | 1.89 | 27.74 | −1.67 |

| Yes | 929 | 0.04 | 11.42 | 0.05 | 0.00 | 0.39 | 0.00 | −1.89 | −27.74 | 1.67 |

| Rash | ||||||||||

| No | 1,933 | 0.05 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.00 | −9.32 | 4.99 | 2.19 |

| Yes | 62 | 1.65 | 0.67 | 0.17 | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 9.32 | −4.99 | −2.19 |

| Previous bouts of malaria | ||||||||||

| No | 1,034 | 0.99 | 8.02 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.30 | 0.00 | 10.25 | 24.49 | 1.37 |

| Yes | 961 | 1.07 | 8.63 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.30 | 0.00 | −10.25 | −24.49 | −1.37 |

Values in bold show the axis on which each modality contributed (contribution value greater than 2.5 indicates a contribution) and where it had greater quality representation (cosine squared). ≤ −2 or ≥ 2 (values in bold) were taken as cut-off points for the test values for significant representation. Modality consists of variables associated with a specific pole for each profile, as identified by the test value sign (negative or positive).

Table 4.

Test values for illustrative variables.

| Supplementary variables | n | Test values | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Axis 1 | Axis 2 | Axis 3 | ||

| P. vivax infection | ||||

| No | 583 | −0.57 | 8.07 | 3.39 |

| Yes | 1,412 | 0.57 | −8.07 | −3.39 |

| P. falciparum infection | ||||

| No | 1,563 | 7.23 | 2.11 | −1.41 |

| Yes | 432 | −7.23 | −2.11 | 1.41 |

| P. malariae infection | ||||

| No | 1,133 | −0.70 | 3.16 | 2.38 |

| Yes | 862 | 0.70 | −3.16 | −2.38 |

| Parasitaemia | ||||

| 1–1,999 | 177 | 0.85 | −1.49 | −0.87 |

| 2,000–4,999 | 159 | 4.58 | −1.76 | −3.73 |

| 5,000–9,999 | 145 | 2.10 | −0.28 | −2.30 |

| >9,999 | 256 | 4.27 | 0.45 | −6.25 |

≤−2 or ≥ 2 (values in bold) were taken as cut-off points for the test values for significant representation. Modality consists of variables associated with a specific pole for each profile, as identified by the test value sign (negative or positive).

Table 5.

Profile structure.

| Pole | Profile | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | |

| Negative | Puerto Nariño | Abdominal pain, yes | Fever, yes |

| Area 4 | Previous bouts of malaria, yes | Shivering, yes | |

| Headache, mild | Stagnant water, no | Vomiting, yes | |

| Stagnant water, no | 19–60 years of age | Diarrhoea, yes | |

| Shivering, no | Normal-coloured urine | Puerto Nariño | |

| Previous malaria, yes | Headache, moderate | Headache, moderate | |

| P. falciparum | Diarrhoea, yes | Normal-coloured urine | |

| Parasitaemia 2,000–4,999 | Fever, no | Area 4 | |

| Headache, mild | P. vivax | ||

| P. falciparum | P. malariae | ||

| P. malariae | Parasitaemia >9,999 | ||

| P. vivax | Parasitaemia 2,000–4,999 | ||

| Positive | Headache, moderate | Fever, yes | Headache, no |

| Previous bouts of malaria, no | Amber-coloured urine | Amber-coloured urine | |

| Mosquito net use, no | ≤5 years | Area 2 | |

| Shivering, yes | Water stagnation, yes | Area 1 | |

| Vomiting, yes | Previous bouts of malaria, no | 19–60 years of age | |

| Stagnant water, yes | Headache, no | Leticia | |

| Insecticide use, yes | Abdominal pain, no | Shivering, no | |

| Headache, severe | Fever, no | ||

| Area 1 | |||

| Leticia | |||

Modality consists of the variables making up each profile (negative and positive poles), taking the contribution, cosine squared and test values into account. Illustrative variables enriching each profile are indicated in bold.

Figure 4.

Multiple correspondence analysis (MCA). Part (a) represents the mode on axes 1 and 2. Part (b) represents the mode on axes 1 and 3. Part (c) represents the mode on axes 2 and 3. The variables contributing towards each profile are highlighted; green indicates the positive pole and red indicates the negative pole variables.

The first profile consisted of variables related to the area in which the patients reside, their sanitary conditions (i.e. nearby stagnant water, mosquito nets and insecticide use) and certain symptoms (i.e. headache, shivering and vomiting). Residing in Puerto Nariño, area 4, having no stagnant water nearby, having a history of malaria and displaying mild symptoms (i.e. mild headache without shivering) correlated with P. falciparum infection (Table 5 and Fig. 4a).

The second profile related to triple P. falciparum, P. vivax and P. malariae infection, and the variables covered age, living conditions, medical history and symptoms (i.e. 19–60 years of age, having no stagnant water nearby, having a history of malaria, symptoms including abdominal pain, normal-coloured urine, slight to moderate headache, diarrhoea and no fever) (Table 5 and Fig. 4b).

The third profile (double P. vivax and P. malariae infection) highlighted more severe symptomatology, together with parasitaemia. The variables included living in Puerto Nariño, area 4, fever, shivering, vomiting, diarrhoea, moderate headache, normal-coloured urine and >9,999 or between 2,000–4,999 parasitaemia (Table 5 and Fig. 4c).

Discussion

The climatic, environmental and geographic characteristics in South America provide favourable conditions for the circulation of Plasmodium spp. and vector-borne diseases such as malaria, which thereby poses a significant threat to public health in countries such as Colombia22. The population living in the Colombian Amazon region is particularly vulnerable, showing high malarial morbidity and mortality7,9.

In this report, most of the study population resided in rural areas lacking access to water, sewerage and/or gas (i.e. public services). Their type of housing is palafitic (i.e. stilt houses over water/alongside a river supported by pillars or simple stakes, or houses built on bodies of calm water such as lakes, lagoons and slow running large rivers), often but not always having palm-leaf roofs and wooden walls, thereby exposing their inhabitants to the environment and the vector’s ecosystem, thus increasing their probability of acquiring parasitic infections23. Such living conditions result in the high prevalence of malaria in this population, and in other populations in Colombia and worldwide8,24,25.

The active search for parasite infections has involved the simultaneous use of molecular and conventional microscopy techniques. This approach has enabled the diagnosis of P. malariae and mixed-species malaria infections (Additional file 2: Fig. S1). TBS as a diagnostic tool for malaria may not be sufficient as it leads to under-reporting (mainly of mixed-species malaria) and is limited in its ability of ensure timely treatment. Its use must thus be complemented by techniques providing greater sensitivity (i.e. molecular techniques)10,13,26,27. Prompt and accurate diagnosis of malarial infection in symptomatic populations and the identification of asymptomatic and sub-microscopic infections contributing to transmission can thus constitute part of the effective control and management of disease, with a view to eliminating malaria28,29.

Using molecular techniques enabled the identification of a large number of parasite infections and a high PDI (Additional file 6: Table S3) for Colombia; municipalities in Colombia’s Pacific region and the Antioquia region have reported similar results in terms of infection and PDI30. Molecular diagnostic tools have enabled the successful and highly sensitive detection of parasite species involved in mixed infections. In this study, more than 40% of the target population had mixed-species infections (Fig. 3 and Additional file 2: Fig. S1b), which was consistent with previous reports in India20, Thailand31, Papua New Guinea32 and Brazil33.

As previously reported for Colombia, P. vivax was associated with the highest frequency of malaria in all localities evaluated (Fig. 2)3,34; conversely, in the Peruvian Amazonian region the prevalence of this species varies in accordance with the area being evaluated35.

P. malariae was the second most highly ranked species in terms of disease frequency and contribution to infections (Fig. 2). This parasite species is known to be widespread across sub-Saharan Africa and south-eastern Asia36; however, molecular detection methods identified a higher proportion of P. malariae compared with microscopy in our study and in previous studies in Colombia and worldwide3,10,31,33.

P. falciparum showed lower prevalence and contribution to cases of malaria in the target population. A differential infection frequency was detected for this species with respect to the type of settlement, with the number of cases of infection with this parasite being greater in rural populations (Fig. 4b and Additional file 6: Table S3).

Differential parasitaemia levels were detected amongst the different areas being sampled. Individuals living in endemic areas who have been exposed to the parasite from an early age display a certain degree of immunity, as exemplified by low parasitaemia levels when exposed to new infections37,38. This may partially explain why the population inhabiting area 4 had the lowest levels of parasitaemia (Additional file 4: Fig S3b), consistent with the fact that more than 50% of this area’s inhabitants had suffered previous episodes of malaria. However, further studies regarding the association between previous episodes of malaria and parasitaemia levels are needed.

Evaluating the factors associated with mixed-species infection revealed that high parasitaemia levels were less frequently associated with simultaneous P. falciparum and P. malariae infection (Table 2 and Additional file 9: Table S4). Cross protection has been reported for these two parasite species39, as they share common antigens37,40, therefore host immunity limits parasitaemia in this type of mixed infection.

Parasite infection may be favoured by certain host characteristics that increase the interaction of parasites with target cells, thereby leading to greater infection success41,42; for example, the probability of being bitten and the transmission frequency is greater in endemic populations32,43,44. Some areas within the Colombian Amazon region were found to be associated with higher levels of parasite infection; mixed infections (P. vivax and P. malariae) were associated with localities in areas 1 and 4 and Puerto Nariño (Additional file 9: Tables S4 and 5), whereas P. falciparum infection was concentrated in rural populations, mainly in localities in area 4 (Table 5 and Additional file 6: Table S3).

Spatial factors influence the parasite-host-vector interaction and contribute towards the appearance of high transmission foci or hotspots within a geographical area45,46. In these foci, high levels of parasite circulation are observed, thereby facilitating dispersion to other localities and contributing to the spread of infections47,48.

The mean parasitaemia values were similar for different types of infection (single or mixed) (Additional file 4: Fig. S3a), suggesting that more than one species of the same organism did not seem to have an additive effect on the amount of circulating parasites. Previous studies have proposed a density-dependent regulation mechanism interacting with other factors such as a species-genotype specific immune response, resulting in stabilisation of the Plasmodium population and episodes that are not dependent on infection by particular species49, which may help to explain our findings.

The coexistence of more than one parasite species in the same individual may be mediated by host and pathogen factors, such as the host immune response initially directed against the species or genotype at the highest density, thereby favouring the persistence of infection at lower density in a particular host39. The species/genotype coexistence model is controlled by parasite density-dependent regulation mechanisms; this model suggests that parasitaemia of the first infecting species (which has the highest prevalence amongst the target population) is downregulated on coinfection with the second species (which has the lowest prevalence). However, when the most prevalent species exceeds a threshold, the hosts’ immune response is triggered to limit the infection; such a mechanism is turned off once the parasite density is under control, thereby favouring population growth of the second species in mixed infections and persistence of the parasites in the host39,44,49.

Such mechanisms are largely modulated by the host. Our study evaluated whether specific clinical profiles amongst the target population were linked to infection with particular Plasmodium species. Fever was the symptom detected at the greatest frequency with all parasite species (Additional file 8: Fig. S5), as well as headaches for mixed infections (Additional file 7: Fig. S4).

MCA revealed dependent relationships between active and illustrative variables (Tables 3 and 4) and three profiles were compiled from the results (Table 5 and Fig. 4). The first profile suggested that symptoms such as headache and diarrhoea, along with previous episodes of malaria, occurred in the target population regardless of the species or infection status (single or mixed). It has been reported that infection-derived immunity in regions with constant parasite circulation (endemic regions), such as the Colombian Amazon region, induces a clinical course with non-specific symptomatology25.

The second profile related to triple infection and a population aged from 19 to 60 years (Fig. 4b and Table 5). High mixed infection frequencies were observed in this age group (Additional file 3: Fig. S2a), i.e. the economically-active population who are potentially those most exposed to mosquito bites and therefore to parasite transmission. The target region’s economic activity is related to artisan-produced handicrafts exploiting wood, fishing, mining and small-scale cultivation in community gardens, all situations that favour the transmission of disease and limit the effectiveness of parasite control measures22,34.

The third profile related to severe symptoms (i.e. fever) and mixed P. vivax and P. malariae infections (Fig. 4c and Table 5). This profile supported the aforementioned parasite density-dependent population regulation model39,49,50. This model illustrates that a parasite species present at higher density would influence the growth of other parasite species activating typical clinical symptoms in the host and maintaining stability of the population dynamics of parasite species51.

In-depth analysis is required for defining infection hotspots. Time series analysis should be used for parasite detection to establish whether infection events are due to transient infection or transmission foci, and risk maps and the population distribution (for host and vector) should be analysed to determine the localities of disease cases16,46,48. Identifying whether a specific area has high disease transmission enables appropriate management strategies to be designed to effectively limit the parasite’s transmission cycle47,48.

Control measures implemented in Colombia have focused on reducing the disease burden by the large-scale provision of insecticide-treated mosquito nets, periodic intra-household spraying and the presence of government agencies responsible for control, diagnosis and treatment12,30,52. Although endemic countries have introduced disease mitigation measures, they have not had the desired impact as the number of malaria cases has increased, particularly in rural areas7.

The present study actively searched for symptomatic patients in geographically isolated localities lacking nearby healthcare posts. The average family income is less than $250 per month in these areas, so a trip to a health centre represents a considerable family expense (around $50 per trip), so many parasitic infections are not seen or treated by healthcare control programmes22.

Greater malaria control efforts are required for progression towards the elimination of this disease; thus, understanding the distribution patterns of particular parasite species and the factors that influence malaria transmission in the Colombian Amazon region is crucial. The results of this study provide additional insight into malarial infections in the Colombian Amazon region, helping define the areas to be prioritised in terms of malaria prevention and control measures, with the aim of decreasing malarial incidence and approaching the long-term goal of eradication.

Methods

Study area and population

This transversal study was carried out from July 2015 to April 2016; it included the population of the Colombian Amazon trapezium, inhabitants from the towns of Leticia and Puerto Nariño and rural settlements located along the banks of the Amazon and Loretuyacu rivers. The Colombian Amazon region represents 42% of Colombia’s territory and is formed by the Caquetá, Putumayo, Vaupés, Guainía, Guaviare and Amazon departments, the latter comprising the greatest geographical area12,53,54. The Amazon department has 77,088 inhabitants (population density: 1.5 inhabitants per km2)12. The town of Leticia and its surrounding communities had a projected population of 41,639 inhabitants according to the Departamento Administrativo Nacional de Estadística (DANE – Colombian Official Statistics Department) 2016 figures; Puerto Nariño and its neighbouring communities accounted for 8,279 inhabitants12.

Fifty-seven localities were sampled and grouped into four areas, taking into account their location and mobilisation towards basins converging on major tributaries (the Amazon and Loretuyacu rivers) (Fig. 1 and Additional file 1: Table S1). Area 1 included 32 localities (including the town of Leticia, the capital of the Amazon department and the remaining rural settlements), area 2 covered 10 localities (one settlement being mainly urban and the rest rural), area 3 covered seven localities (all rural) and area 4 covered eight localities (rural settlements all along the banks of the Loretuyacu river).

Ethical considerations and sample-taking

Inclusion criteria consisted of recognising symptoms related to malarial infection when taking samples, such as headache, fever during the previous 8 days and sweating. People without malaria symptoms were not included in the study (exclusion criterion). The aim of the study was explained to patients; those who accepted an invitation to participate signed an informed consent form. A survey was then conducted that compiled information regarding participants’ socio-demographic characteristics and risk factors for malaria infection. This study was approved and supervised by the Universidad del Rosario’s (Colombia) School of Medicine and Health Sciences (EMCS) Research Ethics Committee (Comité de Ética en Investigacion - CEI) (CEI-ABN026-000161). Patients under 18 years of age who accepted the invitation to participate signed an informed consent, along with their tutors’ written approval. All methods and experiments were performed in accordance with the approved guidelines.

Two blood samples were collected simultaneously by capillary puncture. The first (TBS) was subjected to parasitological diagnosis by optical microscopy following Giemsa staining; the samples were processed and read on site at the time of sample collection. The second sample was stored on Flinders Technology Associates (FTA) cards and transported to the molecular biology laboratory of the FIDIC for molecular identification of the infecting parasite.

Molecular diagnosis of Plasmodium spp

A Pure Link Genomic DNA mini kit (Invitrogen) was used for extracting the DNA from the FTA cards, following the manufacturer’s instructions. This was followed by PCR amplification of the extracted DNA to confirm the presence of the human β-globin constitutive gene segment3,10.

The infecting Plasmodium species (P. vivax, P. falciparum and/or P. malariae) were identified in the β-globin-positive samples by nested PCR. Specific primers against the 18 S rRNA fragment were used in the first round of PCR for genus detection and a second amplification (using the first PCR product as template) was performed to distinguish the P. falciparum, P. vivax and P. malariae species. The amplification conditions for these PCRs have been described previously by our group3,10.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarise the sociodemographic variables, such as the sample-taking area, access to basic services (public water and electricity supply, sewerage service) and risk factors (nearby stagnant water, mosquito nets and insecticide use); these were presented as percentages with their respective 95% confidence intervals (95% CI). Age and parasitaemia (defined by TBS, as the number of parasites per 8,000 white cells/μL/number of white cells) were reported, along with their respective means and standard deviations (SD)55. The parasite density index (PDI) was taken as the amount of confirmed cases of malaria/population at risk56. Mixed infections were defined as the simultaneous detection of two or more Plasmodium spp. Fisher’s exact or Chi2 tests were used for establishing statistically significant differences amongst the data. ANOVA was used for comparing means and Bonferroni test was used for adjusting for multiple comparisons. A t-test was used for comparing the mean values for parasitaemia with the parasite infection status (single and/or mixed infection).

Logistic regression analysis was used for modelling the risk of a mixed infection, taking mixed infections as a dependent variable. Independent variables included in the model were age, residing in an urban or rural area, parasitaemia reported by TBS and housing conditions such as sewerage, gas and electricity supply, nearby stagnant water and mosquito net and insecticide use. STATA 12 software was used for analysing the data.

Multiple correspondence analysis (MCA) was used for establishing patient profiles, taking into account the nature of the clinical, epidemiological and laboratory variables (fundamentally categorical) estimated in this study. MCA was used for evaluating the degree to which each clinical and epidemiological variable participated in the compiling of profiles or groups of clinical significance in terms of similarity with or proximity to the different categories of variables, thus facilitating the incorporation of laboratory variables (infection presence/absence, parasitaemia) into these profiles’ for observing patterns57–59. In this way, groups were identified that had clinical significance from different groupings of categories of variables (i.e. this method was used to identify how sociodemographic characteristics and risk factors were grouped with single or multiple infections).

Two groups of variables were chosen for this analysis: active variables used for constructing factorial axes and supplementary or illustrative variables, which enriched factorial axes interpretation once they had been constructed58.

Sociodemographic, epidemiological and clinical variables were considered active variables, i.e. age, gender, origin, area, mosquito net and insecticide use, nearby stagnant water, fever, headache, vomiting, shivering, diarrhoea, urine colour, abdominal pain, outbreaks on the skin and previous episodes of malaria. The contribution values for each category were analysed for interpreting the axes compiled by the active variables, and the categories with a contribution value of more than 2.5 [mean contribution of 40 categories (100/40 = 2.5%)] were selected57.

Illustrative variables were the presence/absence of P. vivax, P. falciparum and P. malariae infection and parasitaemia. Cosine values were evaluated for estimating the quality of each active variable’s representation on each axis. The test values were used to determine whether the representation of each category on each axis significantly differed from 0 (≤−2 or ≥ 2 cut-off points), thus giving an evaluation of each category’s significance57.

The structure and formation of each profile were analysed using a bi-dimensional graphical representation. The active variables (epidemiological and clinical variables and risk factors) were represented on each axis by filled boxes and the nominal illustrative variables (infection by each of the three species and parasitaemia) were represented by empty rhombuses. The test values sign indicated each modality’s position on the positive or negative pole of each axis. Square size was proportional to each modality’s contribution on the most representative axis. Possible dependence and similarity relationships were identified, taking into account the distance between the variables represented on the graph, regarding the categories thus represented. SPAD-5 software was used for MCA.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Amazon department governorate for sponsoring the project entitled, “Malaria prevention and control strategies in the Amazon region, in response to the recent outbreak of the disease”, which was financed through resources from Colombia’s General System of Royalties and the Colombian Science, Technology and Innovation Department (project BPIN-266, special agreement 020). The financing entities played no part in designing the study, analysing the data and/or preparing the manuscript. The authors would like to thank Carlos H. Niño, Teódulo Quiñonez and Moisés Tomás Cortés Castillo for technical support regarding sample-taking. We would also like to thank Jason Garry for translating the manuscript and Kate Fox, DPhil, from Edanz Group (www.edanzediting.com/ac) for style corrections of the final manuscript.

Author Contributions

M.C., S.C.S.L. and L.R.O. conceived and designed the study, analysed and interpreted the data and prepared the manuscript. A.C.P. and Z.G. analysed the data. E.G. supervised the fieldwork. J.R.C. and P.A.C.A. supervised the laboratory assays. M.E.P. and M.A.P. conceived and designed the study and revised the manuscript. All authors have reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Milena Camargo, Sara C. Soto-De León and Luisa Del Río-Ospina contributed equally to this work.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-018-23801-9.

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.White NJ, et al. Malaria. Lancet. 2014;383:723–735. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60024-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Griffiths, S. Chapter 1: Why research infectious diseases of poverty? Global report for research on infectious diseases of poverty. 1–34 (2012).

- 3.Camargo-Ayala PA, et al. High Plasmodium malariae prevalence in an endemic area of the Colombian Amazon region. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0159968. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0159968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cowman AF, Healer J, Marapana D, Marsh K. Malaria: biology and disease. Cell. 2016;167:610–624. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.07.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lalremruata A, et al. Species and genotype diversity of Plasmodium in malaria patients from Gabon analysed by next generation sequencing. Malar. J. 2017;16:398. doi: 10.1186/s12936-017-2044-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.WHO. World Malaria Report. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland. (2016).

- 7.OPS/OMS. Alerta Epidemiológica: Aumento de casos de malaria, 15 de febrero de 2017. Washington, D.C. (2017).

- 8.PAHO/WHO. Report on the situation of malaria in the Americas, 2000–2015. (2017).

- 9.PAHO. Report on the situation of malaria in the Americas 2012. (2013).

- 10.Nino CH, et al. Plasmodium malariae in the Colombian Amazon region: you don’t diagnose what you don’t suspect. Malar. J. 2016;15:576. doi: 10.1186/s12936-016-1629-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Arevalo-Herrera M, et al. Malaria in selected non-Amazonian countries of Latin America. Acta Trop. 2012;121:303–314. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2011.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carebilla, M. A. P de Desarrollo Amazonas 2016–2019. Gestión y Ejecución para el Bienestar, la Conservación Ambiental y la Paz. (2015).

- 13.Ferreira MU, Castro MC. Challenges for malaria elimination in Brazil. Malar. J. 2016;15:284. doi: 10.1186/s12936-016-1335-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.da Silva-Nunes M, et al. Amazonian malaria: asymptomatic human reservoirs, diagnostic challenges, environmentally driven changes in mosquito vector populations, and the mandate for sustainable control strategies. Acta Trop. 2012;121:281–291. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2011.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hivat H, Bretas G. Ecology of Anopheles darlingi root with respect to vector importance. Parasit. Vectors. 2011;4:177. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-4-177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bannister-Tyrrell M, et al. Defining micro-epidemiology for malaria elimination: systematic review and meta-analysis. Malar. J. 2017;16:164. doi: 10.1186/s12936-017-1792-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Anyanwu PE, Fulton J, Evans E, Paget T. Exploring the role of socioeconomic factors in the development and spread of anti-malarial drug resistance: a qualitative study. Malar. J. 2017;16:203. doi: 10.1186/s12936-017-1849-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Driss A, et al. Genetic polymorphisms linked to susceptibility to malaria. Malar. J. 2011;10:271. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-10-271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gutierrez JB, Galinski MR, Cantrell S, Voit EO. From within host dynamics to the epidemiology of infectious disease: Scientific overview and challenges. Math. Biosci. 2015;270:143–155. doi: 10.1016/j.mbs.2015.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Singh US, Siwal N, Pande V, Das A. Can mixed parasite infections thwart targeted malaria elimination program in India? Biomed. Res. Int. 2017;2017:2847548. doi: 10.1155/2017/2847548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zimmerman PA, Mehlotra RK, Kasehagen LJ, Kazura JW. Why do we need to know more about mixed Plasmodium species infections in humans? Trends Parasitol. 2004;20:440–447. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2004.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Barbosa S, et al. Epidemiology of disappearing Plasmodium vivax malaria: a case study in rural Amazonia. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2014;8:e3109. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0003109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kazembe LN, Mathanga DP. Estimating risk factors of urban malaria in Blantyre, Malawi: A spatial regression analysis. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Biomed. 2016;6:376–381. doi: 10.1016/j.apjtb.2016.03.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.da Silva NS, et al. Epidemiology and control of frontier malaria in Brazil: lessons from community-based studies in rural Amazonia. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2010;104:343–350. doi: 10.1016/j.trstmh.2009.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Arevalo-Herrera M, et al. Clinical profile of Plasmodium falciparum and Plasmodium vivax infections in low and unstable malaria transmission settings of Colombia. Malar. J. 2015;14:154. doi: 10.1186/s12936-015-0678-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wangai LN, et al. Sensitivity of microscopy compared to molecular diagnosis of P. falciparum: implications on malaria treatment in epidemic areas in Kenya. Afr. J. Infect. Dis. 2011;5:1–6. doi: 10.4314/ajid.v5i1.66504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Alemu A, et al. Comparison of Giemsa microscopy with nested PCR for the diagnosis of malaria in North Gondar, north-west Ethiopia. Malar. J. 2014;13:174. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-13-174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lennon SE, et al. Malaria elimination challenges in Mesoamerica: evidence of submicroscopic malaria reservoirs in Guatemala. Malar. J. 2016;15:441. doi: 10.1186/s12936-016-1500-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Oriero EC, Van Geertruyden JP, Nwakanma DC, D’Alessandro U, Jacobs J. Novel techniques and future directions in molecular diagnosis of malaria in resource-limited settings. Expert Rev. Mol. Diagn. 2015;15:1419–1426. doi: 10.1586/14737159.2015.1090878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rodriguez JC, Uribe GA, Araujo RM, Narvaez PC, Valencia SH. Epidemiology and control of malaria in Colombia. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo. Cruz. 2011;106(Suppl 1):114–122. doi: 10.1590/S0074-02762011000900015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhou M, et al. High prevalence of Plasmodium malariae and Plasmodium ovale in malaria patients along the Thai-Myanmar border, as revealed by acridine orange staining and PCR-based diagnoses. Trop. Med. Int. Health. 1998;3:304–312. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3156.1998.00223.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mehlotra RK, et al. Random distribution of mixed species malaria infections in Papua New Guinea. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2000;62:225–231. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2000.62.225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cavasini MT, Ribeiro WL, Kawamoto F, Ferreira MU. How prevalent is Plasmodium malariae in Rondonia, western Brazilian Amazon? Rev. Soc. Bras. Med. Trop. 2000;33:489–492. doi: 10.1590/S0037-86822000000500011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Castellanos A, et al. Malaria in gold-mining areas in Colombia. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo. Cruz. 2016;111:59–66. doi: 10.1590/0074-02760150382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Carrasco-Escobar G, et al. Micro-epidemiology and spatial heterogeneity of P. vivax parasitaemia in riverine communities of the Peruvian Amazon: A multilevel analysis. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:8082. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-07818-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Collins WE, Jeffery GM. Plasmodium malariae: parasite and disease. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2007;20:579–592. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00027-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Collins WE, Jeffery GM. A retrospective examination of sporozoite- and trophozoite-induced infections with Plasmodium falciparum in patients previously infected with heterologous species of Plasmodium: effect on development of parasitologic and clinical immunity. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1999;61:36–43. doi: 10.4269/tropmed.1999.61-036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pombo DJ, et al. Immunity to malaria after administration of ultra-low doses of red cells infected with Plasmodium falciparum. Lancet. 2002;360:610–617. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)09784-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bruce MC, Day KP. Cross-species regulation of malaria parasitaemia in the human host. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2002;5:431–437. doi: 10.1016/S1369-5274(02)00348-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.McKenzie FE, Bossert WH. Multispecies Plasmodium infections of humans. J. Parasitol. 1999;85:12–18. doi: 10.2307/3285692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zimmerman PA, Ferreira MU, Howes RE, Mercereau-Puijalon O. Red blood cell polymorphism and susceptibility to Plasmodium vivax. Adv. Parasitol. 2013;81:27–76. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-407826-0.00002-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lawaly YR, et al. Heritability of the human infectious reservoir of malaria parasites. PLoS One. 2010;5:e11358. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mehlotra RK, et al. Malaria infections are randomly distributed in diverse holoendemic areas of Papua New Guinea. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2002;67:555–562. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2002.67.555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bruce MC, Macheso A, McConnachie A, Molyneux ME. Comparative population structure of Plasmodium malariae and Plasmodium falciparum under different transmission settings in Malawi. Malar. J. 2011;10:38. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-10-38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ostfeld RS, Glass GE, Keesing F. Spatial epidemiology: an emerging (or re-emerging) discipline. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2005;20:328–336. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2005.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Stresman GH, et al. Impact of metric and sample size on determining malaria hotspot boundaries. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:45849. doi: 10.1038/srep45849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bousema T, et al. Identification of hot spots of malaria transmission for targeted malaria control. J. Infect. Dis. 2010;201:1764–1774. doi: 10.1086/652456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bousema T, et al. Hitting hotspots: spatial targeting of malaria for control and elimination. PLoS Med. 2012;9:e1001165. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bruce MC, Day KP. Cross-species regulation of Plasmodium parasitemia in semi-immune children from Papua New Guinea. Trends Parasitol. 2003;19:271–277. doi: 10.1016/S1471-4922(03)00116-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bruce MC, et al. Cross-species interactions between malaria parasites in humans. Science. 2000;287:845–848. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5454.845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gurarie D, Zimmerman PA, King CH. Dynamic regulation of single- and mixed-species malaria infection: insights to specific and non-specific mechanisms of control. J. Theor. Biol. 2006;240:185–199. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2005.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.WHO. Malaria entomology and vector control. Guide for participants, http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/85890/1/9789241505819_eng.pdf (2013).

- 53.SIAT-AC. Territorial-Environmental Information System of Colombian Amazon SIAT-AC http://siatac.co/web/guest/region/referencia (2017).

- 54.Rodriguez, C. A. Plan de desarrollo departamento del Amazonas 2012–2015. Por un buen vivir, somos pueblo, somos más http://cdim.esap.edu.co/BancoMedios/Documentos%20PDF/amazonasplandedesarrollo2012-2015.pdf (2012).

- 55.WHO. Basic malaria microscopy – Part I: Learner’s guide. Second edition http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/44208/1/9789241547826_eng.pdf (2010).

- 56.INS. Protocolo de Vigilancia en Salud Pública-Malaria 1–25, http://www.clinicamedihelp.com/documentos/protocolos/PRO%20Malaria.pdf (2014).

- 57.Del Rio-Ospina L, et al. Multiple high-risk HPV genotypes are grouped by type and are associated with viral load and risk factors. Epidemiol. Infect. 2017;145:1479–1490. doi: 10.1017/S0950268817000188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lebart, L., Morineau, A. & Piron, M. Statistique Exploratoire Multidimensionnelle. Paris: Dunod. 439 (1995).

- 59.Escofier, B. & Pagés, J. Análisis factoriales simples y múltiples: objetivos, métodos e interpretación. España: Universidad del País Vasco. 286 (1992).

- 60.Instituto Geográfico Agustín Codazzi, http://geoportal.igac.gov.co/mapas_de_colombia/igac/mps_fisicos_deptales/2012/Amazonas.pdf (2017).

- 61.Instituto Geográfico Agustín Codazzi: Terms and Conditions of Use, http://www.igac.gov.co/wps/wcm/connect/0b3aa8004eef2fd4a7abf730262db5f2/Licencia_y_condiciones_de_uso_car.pdf?MOD=AJPERES (2017).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.