Abstract

Purpose

To determine parents’ knowledge and attitudes regarding human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccinations in their adolescent children and to describe parents’ perceptions of adolescent vaccinations in community pharmacies.

Methods

In-depth interviews were completed with parents or guardians of children ages 11–17 years from Alabama's Lee and Macon counties. One-hour long, open-ended telephonic or in-person interviews were conducted until the saturation point was reached. Using ATLAS.ti software and thematic analysis, interview transcripts were coded to identify themes.

Results

Twenty-six parents were interviewed, most of whom were female (80.8%) and white (50%). A total of 12 themes were identified. First, two themes emerged regarding elements facilitating children's HPV vaccination, the most common being positive perception of the HPV vaccine. Second, elements hindering children's vaccination contained seven themes, the top one being lack of correct or complete information about the HPV vaccine. The last topic involved acceptance/rejection of community pharmacies as vaccination settings, and the most frequently cited theme was concern about pharmacists’ clinical training.

Conclusions

Physician-to-parent vaccine education is important, and assurances of adequate pharmacy immunization training will ease parents’ fears and allow pharmacists to better serve adolescents, especially those who do not see physicians regularly.

Keywords: Human papillomavirus, Adolescent immunization, Community pharmacy, Cervical cancer prevention

Highlights

-

•

Physicians play a crucial role in parents’ HPV vaccination decisions.

-

•

Parents are reluctant to use pharmacists as HPV vaccine providers.

-

•

Parents are concerned about pharmacists’ training and pharmacy infrastructure.

-

•

Community pharmacists must work in conjunction with physicians.

1. Introduction

Human papillomavirus (HPV) is one of the most common sexually transmitted infections. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), about 79 million Americans are currently infected and 14 million people become infected each year [1]. Three vaccines are approved, including Gardasil® (for girls and boys age 9–26 years), Gardasil 9® (for girls age 9–26 years and boys age 9–15 years), and Cervarix® (for girls age 9–25 years) [2]. All three vaccines protect against HPV strains 16 and 18, which cause over 70% of cervical cancer cases. Gardasil® also protects against an additional two and Gardasil 9® protects against an additional seven less common strains [2]. Administration is recommended between the ages of 11 and 12 as a three-dose series over six months [2].

Despite the availability of vaccines to prevent HPV, the U.S. vaccination rate falls below the 80% national objective [3]. The national vaccination rates in 2014 for adolescents ages 13–17 years who received at least one dose were 60% for girls and 41.7% for boys [3]. Among those who initiated the series, only 69.3% of girls and 57.8% of boys completed all three doses [3]. Additionally, disparities in HPV vaccination coverage continues to be a problem. For example, the southern United States has lower vaccination rates than elsewhere in the country. Disparities in knowledge also exist; parents of adolescents in rural areas are less aware of the HPV vaccine because they are less likely to be presented with the information [5], [6].

Recommendations from healthcare professionals are key to HPV vaccine acceptability [7], [8], [9], [10]. Interestingly, physicians do not rank the HPV vaccine as important when compared to other vaccines (Tdap and meningococcal vaccines) and often discuss the HPV vaccine last during patient visits [11]. Furthermore, previous research has reported the associations between HPV vaccine acceptability and parental characteristics, including sociodemographic factors, knowledge, perceived vaccine effectiveness, risk perceptions, and vaccine cost [12], [13], [14], [15], [16]. Given variations in vaccination coverage in certain regions of the U.S., it is important to explore attitudes and knowledge among parents of adolescents residing in southern states where vaccination rates are low.

The low completion rate of the HPV vaccine series is concerning [17]. Although lack of physician recommendation is a key barrier to HPV vaccine series initiation, additional barriers, such as irregular preventive care, may hinder series completion [18]. Taking into account this potential difference in barriers, pharmacies may be a good choice for completing the series. Thus, this study explores parental perceptions of pharmacists as non-traditional immunizers for HPV vaccinations in adolescents. Because pharmacists/pharmacies are readily accessible during extended hours and on weekends, with no appointments or visit copayments required [19], [20], [21], [22], [23], pharmacies are well-suited to accommodate many adolescents who do not frequently visit physicians, and provide a convenient alternative vaccination setting [24]. Given pharmacists’ established role as providers of adult immunizations, pharmacy-based vaccination services have great potential to increase HPV vaccination and completion rates among adolescents [25], [26]. However, little is known about parental acceptance of pharmacists as immunizers for HPV vaccinations in their adolescent children.

The objectives of this study were to determine parents’ knowledge and attitudes related to HPV vaccinations for their adolescent children as well as describe parents’ perceptions of adolescent vaccinations in community pharmacies. Better understanding of these may help to improve communication of HPV information between parents, adolescents and healthcare providers, and identify opportunities for community pharmacists to help traditional immunizers increase HPV vaccination coverage and completion rates.

2. Methods

2.1. Study design and participants

This was a qualitative study using telephone or face-to-face interviews with open-ended questions. All procedures were approved as an expedited review by the Institutional Review Board at the first author's institution. The population of interest was parents/guardians of adolescent children, regardless of children's HPV vaccination status. Participants were recruited from Lee and Macon counties in Alabama in June-August 2014 via newspaper advertisements, flyers in public/community locations, a website hosted by the first author's institution, Craigslist ads, and a Facebook group for people in the community. All advertisements included the study's website address and the first author's telephone number. The website contained detailed information about the study, the IRB-approved consent form, and an interest form. Individuals were screened for eligibility via the online or telephone-administered interest form. Individuals were eligible to participate if they were: parents or legal guardians of children ages 11–17 years, residents of Lee or Macon County in Alabama, and able to read and write in the English language. Individuals were excluded from participation if they resided in the same household as another participant. Next, the principal investigator contacted eligible individuals to explain the study's details, obtain a mail/email address to send a consent form, and schedule an interview. Written consent was obtained from each participant before conducting interviews. A financial incentive of $35 was provided to each participant upon interview completion.

2.2. Data collection and measures

A total of 26 interviews were conducted, 11 via telephone and 15 in-person. Recruitment continued until the saturation point was reached (when no new information was obtained from additional interviews). Each interview session included two components: 1) administration of a participant questionnaire, and 2) in-depth interviews. The participant questionnaire was used to elicit demographic characteristics, including age, sex, race, education level, annual income, insurance status, children's usual source of care, and children's vaccination history. Next, in-depth interviews were conducted using open-ended questions to elicit participants’ knowledge and perceptions of HPV vaccines and provision of the vaccination in a community pharmacy. For example, questions included “describe the relationship with your pharmacist” and “what kind of things, positive or negative, have you heard about the HPV vaccine?” If interviewees had limited knowledge of HPV or the vaccine, information in the CDC HPV Vaccine Information Statement was provided, followed by asking, “What do you think about this information?” Interviews ranged from 18 to 50 min with an average of 31 min, and were digitally audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. Throughout the data collection period, quality control procedures were implemented. For example, the three interviewers listened to and discussed the first five recorded interviews to ensure consistency among interviewers.

2.3. Data analysis

Using ATLAS.ti 7.5.6 Qualitative Data Analysis software (ATLAS.ti Scientific Software Development GmbH, Berlin, Germany) and thematic analysis, interview transcripts were coded to identify themes using methods outlined by Braun and Clarke [27] and validated by Conklin et al. [28]. First, patterns within the data were independently identified by two researchers (SM and KW) and used to generate open codes. These codes were discussed and agreed upon, with discrepancies resolved via discourse and consensus. To ensure reliability, open coding was repeated by two additional researchers (LH and TH) for three randomly selected participants. Finalized codes were agreed upon and themes were named by the research team. The primary coder (SM) then identified the frequency of each theme, and themes were clustered into broad topic categories.

3. Results

Of the 26 interviewed parents (Table 1), many were female (80.8%) and between 40 and 49 years of age (42.3%). Half of the participants self-identified as White, with 42.3% having some college education and 30.8% reporting an annual household income from $50,000-$99,999. Among participants, 42.3% had children who received an influenza vaccine during the previous year while only 15.4% had children who received at least one dose of the HPV vaccine.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of Study Participants (n=26).

| Characteristics | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Female | 21 (80.8) |

| Male | 5 (19.2) |

| Age in years | |

| 20–39 | 11 (42.3) |

| 40–49 | 11 (42.3) |

| 50–59 | 3 (11.5) |

| Race | |

| White | 13 (50.0) |

| Black | 10 (38.5) |

| Other | 3 (14.9) |

| Ethnicity | |

| Non-Hispanic | 24 (92.3) |

| Hispanic | 2 (7.7) |

| Education | |

| High school or less | 3 (11.5) |

| Some college or Associate's degree | 11 (42.3) |

| Bachelor's degree | 3 (11.5) |

| Master's or professional degree | 9 (34.6) |

| Insurance coverage for children | |

| Employer-sponsored insurance | 11 (42.3) |

| Medicaid | 9 (34.6) |

| Private individual insurance | 3 (11.5) |

| Other government-sponsored insurance | 3 (11.5) |

| Annual household income | |

| Under $15,000 | 6 (23.1) |

| $15,000 – $34,999 | 3 (11.5) |

| $35,000 – $49,999 | 6 (23.1) |

| $50,000 – $99,999 | 8 (30.8) |

| $100,000 or above | 3 (11.5) |

| Number of children age 11–17 years | |

| One | 20 (76.9) |

| Two | 4 (15.4) |

| Three | 2 (7.7) |

| Children aged 11–17 ever received human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine | |

| Yes | 4 (15.4) |

| No | 20 (76.9) |

| Unsure | 2 (7.7) |

| Children aged 11–17 received influenza vaccine in previous year | |

| Yes | 11 (42.3) |

| No | 14 (53.8) |

| Unsure | 1 (3.8) |

Themes from in-depth interviews were organized into three broad topic categories for ease of presentation and include: 1) elements facilitating HPV vaccine uptake (or acceptability), 2) elements hindering HPV vaccine uptake, and 3) perceptions of and barriers to community pharmacies as nontraditional vaccination settings. A total of 12 themes were identified regarding HPV vaccination (Table 2).

Table 2.

Thematic analysis of in-depth interviews of parents regarding human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccinations for adolescents (n=26).

| Topic | Theme | Excerpt |

|---|---|---|

| Elements facilitating children being vaccinated | Positive perception of the HPV vaccine | “[The HPV vaccine] is something that is for life. This is not one season of the flu. So [the HPV vaccine] is way more serious for me…I guess the severity of [HPV], it's just [important] to me.” |

| “Well the positives I heard are [the HPV vaccine] will protect your child.” | ||

| Influence of a reputable source of information | “…if the doctor said…then I would go ahead and get [my son] vaccinated. If we ended up at the doctor in October and he even mentioned [the HPV vaccine], I would probably go ahead and [vaccinate my son].” | |

| “[There are] not [any other people] that I would listen to really. Just [my son's] doctor…that's who I trust.” | ||

| Elements hindering children being vaccinated | Lack of correct or complete information about the HPV vaccine or HPV infection | “I don’t know if [HPV] could cause [my son] to go sterile…I’m mostly just focused on the women's side…For the males, I’m not sure.” |

| “Is [the HPV vaccine] something that [is recommended] to kids and why at a young age? ” | ||

| Influence of a non-reputable source of information | “…my other family members have gotten [sick from vaccination]….” | |

| “…I will probably Google [information about the HPV vaccine].” | ||

| Concern about side effects from the HPV vaccine | “Especially Gardasil…there have been studies where they have shown…things similar to autism…” | |

| “I think she is safer without [the HPV vaccine] than with it – there are too many side effects…” | ||

| Concern about increased sexual activity due to the HPV vaccine | “I don’t want to plant that seed because…getting this [HPV] vaccine that is just going to protect [my children] so [they] will just go out there and do it.” | |

| “…[the HPV vaccine] would push [my son] towards having sex and him becoming a young father…” | ||

| Personal or economic barrier to receive the vaccine | “One of us [would have] to take off work and go with [my son].” | |

| “…if I had to pay for [the HPV vaccine] I wouldn’t get it.” | ||

| “I have had appointments sometimes that…take a month or more…” | ||

| Belief that child is not susceptible to HPV infection | “I am not worried about [my daughter] getting that virus if sexual transmission is the only way you can get it.” | |

| “[My son] said he didn’t need [the HPV vaccination]. He said he didn’t need it because he's not sexually active.” | ||

| Negative perception of vaccines in general | “…I think [vaccination] is another tool to make more money.” | |

| “…I think children today are over vaccinated.” | ||

| Perceptions and barriers regarding community pharmacies as non-traditional vaccination settings | Concern about pharmacists’ clinical training | “[A pharmacist giving vaccinations is] like me giving immunizations to everybody else…a pharmacy…just fills bottles with pills…” |

| “I don’t know if [pharmacists] have that type of preparation.” | ||

| Concern about infrastructure of pharmacy facility | “I would rather take [my children] to the pediatrician because I know they have our records and that way they will keep records of everything….” | |

| “No, we don’t go [to the pharmacy for vaccinations]. I don’t know… It just doesn’t seem very clinical… I want that clinical experience… you know? ” | ||

| “…for my son, I would like for [vaccinations] to be in a private setting.” | ||

| “I just like to have everything documented. You go into the pharmacy and they give you a shot and you just walk out.” | ||

| Lack of relationship with the pharmacist | “There's a different [pharmacist] every time so it's not somebody that I consult with” |

|

| “I have never asked [the pharmacist] any opinions…I just get my pills from the pharmacy tech most of the time.” | ||

3.1. Elements facilitating HPV vaccine uptake

Two themes were identified from the interviews regarding elements facilitating actual or intended vaccine uptake in participants’ children, including: 1) positive perception of the HPV vaccine, and 2) influence of a reputable source of information. Positive perception of the HPV vaccine was the most frequently cited theme. For example, one participant stated that she believed the HPV vaccine would enable her child to “avoid…symptoms and the risk of cancer.” Another mother stated that, “If [the HPV vaccine] would have been an option for me, I would have done it.” The second theme involved the influence of a reputable source of information. Many parents cited information from pediatricians or family physicians as leading them to vaccinate their children against HPV. For example, one parent stated, “[our family physician] is the only person that I allow to influence my [vaccination] decision.”

3.2. Elements hindering HPV vaccine uptake

The most frequently discussed topic was elements hindering the vaccination of children against HPV, with seven themes identified (Table 2). First, lack of correct or complete information about the HPV vaccine was the most frequently cited theme. For example, one male participant stated that he had not “researched [the HPV vaccine]…[because] that's female issues.” Other parents did not understand the need for the HPV vaccine at a young age. Second, participants were influenced by non-reputable sources of information, such as online searches or negative reports from friends and family. For example, one parent stated, “I have some friends who were vaccinated and they complained.” The third theme was related to harmful effects caused by the vaccine. For example, one parent expressed a serious concern regarding autism caused by vaccines and went as far as providing the researcher with a website that discussed this harm. Fourth, parents expressed reluctance to vaccinate and/or discuss the HPV vaccine with their children, as they believed the vaccine might increase sexual activity due to the child's perception of general protection against sexually transmitted diseases. For example, one mother stated that, “[the HPV vaccine] could possibly… push [my son] towards having sexual intercourse as opposed to staying abstinent.”

The fifth theme involved personal or economic barriers to receiving the HPV vaccine. Many parents were concerned about cost and insurance coverage for the vaccine, as well as missing work and time needed to wait for appointments. Compared to other vaccines that are not administered as a series, such as influenza, parents stated that the HPV vaccine is not a priority because “you have got to go get a series of three shots.” Sixth, parents believed that their children were not susceptible to HPV infection. This was mainly due to a perception that the vaccine was needed only if their children were currently sexually active, with one parent stating that, “…because [HPV] is behavior oriented I don’t have the concern that I have for the flu.” Lastly, the seventh theme involved a negative perception of vaccines in general, with parents viewing vaccination as a commercial enterprise.

3.3. Perceptions and barriers regarding community pharmacies as vaccination settings

Three themes were identified relevant to participants’ perceptions and barriers regarding community pharmacies as nontraditional vaccination settings, including: 1) concern about pharmacists’ clinical training, 2) concern about the infrastructure of pharmacy facilities, and 3) lack of a relationship with the pharmacist. Most parents preferred not to vaccinate their children at community pharmacies. Concern about pharmacists’ clinical training was the most frequently cited theme. In fact, one parent stated that she was not aware pharmacists were trained to give shots, contributing to apprehension and reluctance to utilize community pharmacists as vaccination providers for her children. The second theme focused on the infrastructure of pharmacy settings in general. Many participants were concerned about the record-keeping ability of community pharmacies, with uncertainty regarding the completeness of children's vaccination records or unease with respect to records in multiple locations. Lack of privacy, frequent personnel changes, and the profusion of customers in chain pharmacies also contributed to this wariness of community pharmacies as vaccination settings. The third theme identified that parents lack a relationship with their pharmacists, with one participant stating that her pharmacy experiences were “more of a business transaction” and therefore she preferred to utilize physician-based vaccination services for her children.

4. Discussion

Disparities in HPV vaccination coverage exist among racial/ethnic groups, socioeconomic statuses, and regions in the U.S. [4]. Although HPV vaccination rates are below the national objective across all regions, they are disproportionately lower in the South [4], [29]. This lower rate of HPV vaccination is particularly alarming due to the South's disproportionately higher rate of cervical cancer [30]. Thus, research focusing on HPV vaccination is warranted in the southern region, yet few studies have explored this issue [9], [12], [13]. Consistent with this study, previous research found that the influence of a reputable source of information, a healthcare provider, was a significant predictor of parental intention to vaccinate children in Alabama [9]. In North Carolina, research found that parents who were more knowledgeable of HPV vaccines were more likely to vaccinate their adolescent daughters and they preferred to have their daughters vaccinated at a private physician's office; this is also consistent with our findings [12]. Studies reported a lack of awareness of HPV and the HPV vaccine in Southern regions [12], [13]. Given the lack of awareness and importance of reputable information and knowledge in vaccination decision-making, healthcare providers, particularly those in southern states, should be proactive in recommending the HPV vaccine and taking the time to address parental concerns.

This study was the first identifiable study that explored parents’ perceptions of pharmacists as immunizers for their children. Several articles have recognized that community pharmacies are an underused setting to deliver the HPV vaccine; as such, they have advocated for pharmacy-based HPV immunization services [31], [32], [33], [34]. Previous research reported that about 60% of states allow pharmacists to administer vaccines to adolescents [31]. Pharmacists were also supportive of an expanded role in providing HPV vaccines [33]. Because of this, community pharmacies are in a good position to support traditional immunizers in order to accommodate adolescents who do not frequently visit physicians. This could be accomplished through a partnership model between physician offices and community pharmacies, in which physicians administer the first dose of the HPV vaccine at their office and write a prescription for subsequent doses at community pharmacies. This is more convenient for patients since pharmacies are open after traditional school hours and do not require appointments. Previous research reported that pediatricians were in support of collaboration with non-traditional immunizers, especially for healthy school-aged children [35].

Interestingly, parents explained that they do not generally have a relationship with their pharmacists, and some parents were unaware that pharmacists are trained to provide immunizations. By building relationships with patients and advertising their training and patient care services, including immunizations, pharmacists may be able to overcome this barrier to HPV vaccination provision in pharmacies. This public trust is a key element of vaccine confidence [36]. Additionally, for parents who knew pharmacists could provide immunizations, many would not consider having their child immunized at a community pharmacy because of perceived inability of the pharmacy to keep an accurate and complete record of their child's immunizations. If pharmacists improved their relationships with patients and physicians, it could be easier to convince parents that accurate vaccination records are kept at the pharmacy and reported to the physicians’ offices. This issue also brings up an important point about the need for pharmacists to report vaccination data to their state's immunization registry; only 35% of pharmacies report vaccinations to an immunization registry [37]. The methods presented here to build trust in pharmacists as vaccine providers may thus reduce HPV vaccine hesitancy in U.S. southern states, which could facilitate vaccine uptake.

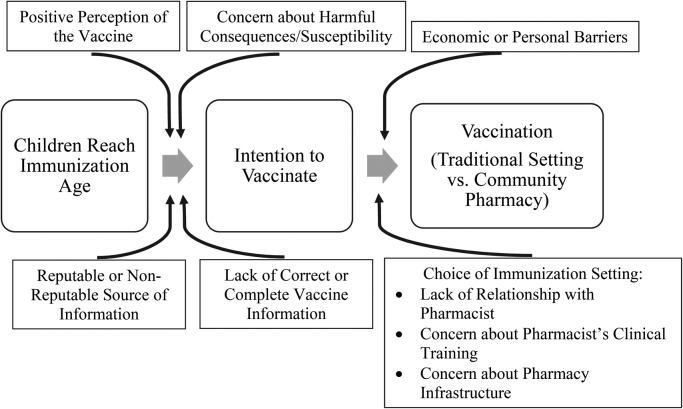

Fig. 1 illustrates a theoretical model of parents’ vaccination decision-making derived from this study's themes (Table 2). This model is consistent with previous research suggesting parents lack credible vaccine information and have barriers to immunization access [34], [38]. The vaccination decision-making model uses elements of behavior change theory [39] and postulates that parents’ intention to vaccinate their children is a proximal mediator of actual vaccination behavior. Once children reach the age for immunization, a higher level of positive perception towards the HPV vaccine and concern about susceptibility to infection, in combination with lower concern about harmful vaccine consequences, leads to greater intention for parents to vaccinate their children. Influence of a more reputable source of information and possession of more correct vaccine information further contribute to vaccination intention. The choice of vaccination setting, however, is moderated by several factors. A lack of relationship with the pharmacist, concern about pharmacists’ clinical training, and concern about pharmacy infrastructure lead to the decision to vaccinate in a traditional setting versus a community pharmacy. Economic and personal barriers to vaccination, such as not being able to afford the vaccine or not highly prioritizing vaccination, also moderate the path from parents’ intention to vaccinate and actual vaccination of their children. Previous research yielded similar results regarding “environmental and tangible” barriers to HPV vaccination and lends credence to the model [34].

Fig. 1.

Parents’ Vaccination Decision-Making for Their Adolescent Children. A model illustrating the influence of parents’ intention to vaccinate their children and the actual vaccination result. Various factors influence the pathway, as gleaned from themes identified in this study.

The current study has limitations to consider. First, the study included 26 participants from Lee and Macon counties. Thus, participants may not be representative of the population of Alabama or the population of other rural southern states. For example, a large percentage of participants reported an annual household income of $50,000-$99,999, which is above the 2010 average of $40,000 in non-metropolitan U.S. regions and the 2014 median of $44,000 in Alabama [40], [41]. Future studies may expand to other regions of Alabama and surrounding southern states to more effectively capture the desired demographic.

Second, the use of thematic analysis may lead to varied interview interpretations depending upon coder, potentially misrepresenting study findings. However, data analysis techniques were adapted from validated sources [27], [28] and coding was rigorously checked by multiple trained researchers to increase internal validity.

Third, our line of questioning was not specifically tailored to analyze parents’ attitudes towards HPV vaccine series initiation versus series completion. This may be an important area for future studies to evaluate, as parents’ willingness to vaccinate their children against HPV in a community pharmacy may change depending on the child's location in the series.

5. Conclusion

Parents based vaccination decisions for their children on availability and quality of vaccine information, and level of confidence in the vaccination provider and setting. Thus, physician-to-parent vaccine education is important, and assurances of adequate pharmacy immunization training will ease parents’ fears. Education should focus on cancer prevention due to the HPV vaccine, while allaying parents’ fears regarding side effects and increased sexual activity gleaned from non-reputable sources. Clear procedures and explanations regarding reporting vaccinations to physicians’ offices and state immunization registries will also promote parental acceptance of community pharmacies as vaccination providers for their children.

Conflicts of Interest

None.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to acknowledge Auburn University Research Initiative in Cancer (AURIC) for their role in funding this study.

Contributor Information

Salisa C. Westrick, Email: westrsc@auburn.edu.

Lindsey A. Hohmann, Email: lah0036@auburn.edu.

Stuart J. McFarland, Email: sjm0020@auburn.edu.

Benjamin S. Teeter, Email: BSTeeter@uams.edu.

Kara K. White, Email: kkw0005@auburn.edu.

Tessa J. Hastings, Email: tjh0043@auburn.edu.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Human Papillomavirus (HPV).2015. 〈http://www.cdc.gov/std/HPV/STDFact-HPV.htm#a7〉

- 2.National Cancer Institute. Human Papillomavirus (HPV) Vaccines.2015. 〈http://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/causes-prevention/risk/infectious-agents/hpv-vaccine-fact-sheet〉

- 3.Elam-Evans L.D., Yankey D., Jeyarajah J., Singleton J.A., Curtis C.R., MacNeil J. National, regional, state, and selected local area vaccination coverage among adolescents aged 13-17 years -- United States, 2013. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2014;63:625–633. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reagan-Steiner S., Yankey D., Jeyarajah J., Elam-Evans L.D., Curtis C.R., MacNeil J. National, regional, state, and selected local area vaccination coverage among adolescents aged 13-17 years - United States, 2015. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2016;65:850–858. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6533a4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Donahue K.L., Stupiansky N.W., Alexander A.B., Zimet G.D. Acceptability of the human papillomavirus vaccine and reasons for non-vaccination among parents of adolescent sons. Vaccine. 2014;32:3883–3885. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.05.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mullins T.L., Widdice L.E., Rosenthal S.L., Zimet G.D., Kahn J.A. Risk perceptions, sexual attitudes, and sexual behavior after HPV vaccination in 11-12 year-old girls. Vaccine. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.06.060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fontenot H.B., Domush V., Zimet G.D. Parental attitudes and beliefs regarding the nine-valentnine-valent human papillomavirus vaccine. J. Adolesc. Health. 2015;57:595–600. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2015.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moss J.L., Gilkey M.B., Rimer B.K., Brewer N.T. Disparities in collaborative patient-provider communication about human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination. Hum. Vaccin Immunother. 2016:0. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2015.1128601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Litton A.G., Desmond R.A., Gilliland J., Huh W.K., Franklin F.A. Factors associated with intention to vaccinate a daughter against HPV: a statewide survey in Alabama. J. Pedia. Adolesc. Gynecol. 2011;24:166–171. doi: 10.1016/j.jpag.2011.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kang H.S., Moneyham L. Attitudes, intentions, and perceived barriers to human papillomavirus vaccination among Korean high school girls and their mothers. Cancer Nurs. 2011;34:202–208. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0b013e3181fa482b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gilkey M.B., Moss J.L., Coyne-Beasley T., Hall M.E., Shah P.D., Brewer N.T. Physician communication about adolescent vaccination: how is human papillomavirus vaccine different? Prev. Med. 2015;77:181–185. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2015.05.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fazekas K.I., Brewer N.T., Smith J.S. HPV vaccine acceptability in a rural Southern area. J. Women's Health. 2002;2008:539–548. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2007.0489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cates J.R., Brewer N.T., Fazekas K.I., Mitchell C.E., Smith J.S. Racial differences in HPV knowledge, HPV vaccine acceptability, and related beliefs among rural, southern women. J. Rural Health. 2009;25:93–97. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.2009.00204.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Allen J.D., Coronado G.D., Williams R.S., Glenn B., Escoffery C., Fernandez M. A systematic review of measures used in studies of human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine acceptability. Vaccine. 2010;28:4027–4037. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.03.063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thompson V.L., Arnold L.D., Notaro S.R. African American parents' attitudes toward HPV vaccination. Ethn. Dis. 2011;21:335–341. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liau A., Stupiansky N.W., Rosenthal S.L., Zimet G.D. Health beliefs and vaccine costs regarding human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination among a U.S. national sample of adult women. Prev. Med. 2012;54:277–279. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2012.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Richards M.J., Peters M., Sheeder J. Human Papillomavirus Vaccine: Continuation, Completion, and Missed Opportunities. J. Pedia. Adolesc. Gynecol. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.jpag.2015.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Holman D.M., Benard V., Roland K.B., Watson M., Liddon N., Stokley S. Barriers to human papillomavirus vaccination among US adolescents: a systematic review of the literature. JAMA Pediatr. 2014;168:76–82. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.2752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ernst M.E., Chalstrom C.V., Currie J.D., Sorofman B. Implementation of a community pharmacy-based influenza vaccination program. J. Am. Pharm. Assoc. 1997;37:570–580. doi: 10.1016/s1086-5802(16)30253-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hogue M., Benske J.A. Pharmacists as immunization advocates. Wis. Pharm. 1997;66:82–85. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Grabenstein J.D., Guess H.A., Hartzema A.G., Koch G.G., Konrad T.R. Effect of vaccination by community pharmacists among adult prescription recipients. Med. Care. 2001;34:340–348. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200104000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Madhavan S.S., Rosenbluth S.A., Amonkar M., Borker R.D., Richards T. Pharmacists and immunizations: a national survey. J. Am. Pharm. Assoc. 2001;41:32–45. doi: 10.1016/s1086-5802(16)31203-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bearden D.T., Holt T. Statewide impact of pharmacist-delivered adult influenza vaccinations. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2005;29:450–452. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2005.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Reiter P.L., Brewer N.T., Gottlieb S.L., McRee A.L., Smith J.S. Parents' health beliefs and HPV vaccination of their adolescent daughters. Soc. Sci. Med. 2009;69:475–480. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.S. Westrick, J. Owen, H. Hagel, J. Owensby, T. Lertpichitkul, Impact of the RxVACCINATE Program for Pharmacy-Based Pneumococcal Immunization: A Cluster Randomized Controlled Trial. J Am Pharm Assoc, In Press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Westrick S.C. Pharmacy characteristics, vaccination service characteristics, and service expansion: an analysis of sustainers and new adopters. J. Am. Pharm. Assoc. 2010;50:52–60. doi: 10.1331/JAPhA.2010.09036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Braun V., Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006;3:77–101. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Conklin J., Farrell B., Ward N., McCarthy L., Irving H., Raman-Wilms L. Developmental evaluation as a strategy to enhance the uptake and use of deprescribing guidelines: protocol for a multiple case study. Implement. Sci. 2015;10:91. doi: 10.1186/s13012-015-0279-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rahman M., Laz T.H., Berenson A.B. Geographic variation in human papillomavirus vaccination uptake among young adult women in the United States during 2008–2010. Vaccine. 2013;31:5495–5499. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.09.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Watson M., Saraiya M., Ahmed F., Cardinez C.J., Reichman M.E., Weir H.K. Using population-based cancer registry data to assess the burden of human papillomavirus-associated cancers in the United States: overview of methods. Cancer. 2008;113:2841–2854. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brewer N.T., Chung J.K., Baker H.M., Rothholz M.C., Smith J.S. Pharmacist authority to provide HPV vaccine: novel partners in cervical cancer prevention. Gynecol. Oncol. 2014;132:S3–S8. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2013.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Navarrete J.P., Padilla M.E., Castro L.P., Rivera J.O. Development of a community pharmacy human papillomavirus vaccine program for underinsured university students along the United States/Mexico border. J. Am. Pharm. Assoc. 2014;54:642–647. doi: 10.1331/JAPhA.2014.13222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Richman A.R., Swanson R.S., Branham A.R., Partridge B.N. Measuring North Carolina pharmacists' support for expanded authority to administer human papillomavirus vaccines. J. Pharm. Pract. 2013;26:556–561. doi: 10.1177/0897190013488801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mills L.A., Head K.J., Vanderpool R.C. HPV vaccination among young adult women: a perspective from Appalachian Kentucky. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2013:10. doi: 10.5888/pcd10.120183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kempe A., Wortley P., O'Leary S., Crane L.A., Daley M.F., Stokley S. Pediatricians' attitudes about collaborations with other community vaccinators in the delivery of seasonal influenza vaccine. Acad. Pediatr. 2012;12:26–35. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2011.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.H. Larson, The State of Vaccine ConfidenceIn: London School of Hygiene andTropical Medicine, editor. The Vaccine Confidence Project.〈http://www.vaccineconfidence.org/research/the-state-of-vaccine-confidence/〉, 2015.

- 37.Department of Health and Human Services National Vaccine Program Office. Annual Pharmacy- Based Influenza and Adult Immunization Survey. Medication Therapy Management Digest: American Pharmacists Association; 2013. 〈https://www.pharmacist.com/sites/default/files/files/Annual%20Immunization%20Survey%20Report.pdf〉.

- 38.Kim K., Kim B., Choi E., Song Y., Han H.R. Knowledge, perceptions, and decision making about human papillomavirus vaccination among Korean American women: a focus group study. Women’s Health Issues. 2015;25:112–119. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2014.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ajzen I. Theories of cognitive self-regulation, the theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991;50:179–211. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Housing Assistance Council. Poverty in Rural America. 2011. 〈http://www.ruralhome.org/storage/documents/info_sheets/povertyamerica.pdf〉

- 41.U.S. Census Quickfacts. Population estimates, July 1, 2014, (V2014). 2015. 〈http://www.census.gov/quickfacts/〉