Abstract

Background:

Toll-like receptors play an integral role in the process of inflammatory response after ischemic in-jury. The therapeutic potential acting on TLRs is worth of evaluations. The aim of this review was to introduce readers some potential medications or compounds which could alleviate the ischemic damage via TLRs.

Methods:

Research articles online on TLRs were reviewed. Categorizations were listed according to the follows, methods acting on TLRs directly, modulations of MyD88 or TRIF signaling pathway, and the ischemic tolerance induced by the pre-conditioning or postconditioning with TLR ligands or minor cerebral ischemia via acting on TLRs.

Results:

There are only a few studies concerning on direct effects. Anti-TLR4 or anti-TLR2 therapies may serve as promis-ing strategies in acute events. Approaches targeting on inhibiting NF-κB signaling pathway and enhancing interferon regu-latory factor dependent signaling have attracted great interests. Not only drugs but compounds extracted from traditional Chinese medicine have been used to identify their neuroprotective effects against cerebral ischemia. In addition, many re-searchers have reported the positive therapeutic effects of preconditioning with agonists of TLR2, 3, 4, 7 and 9. Several trails have also explored the potential of postconditioning, which provide a new idea in ischemic treatments. Considering all the evidence above, many drugs and new compounds may have great potential to reduce ischemic insults.

Conclusion:

This review will focus on promising therapies which exerting neuroprotective effects against ischemic injury by acting on TLRs.

Keywords: Toll-like receptors, cerebral ischemia, inflammation, MyD88, TRIF, medication, compound

1. INTRODUCTION

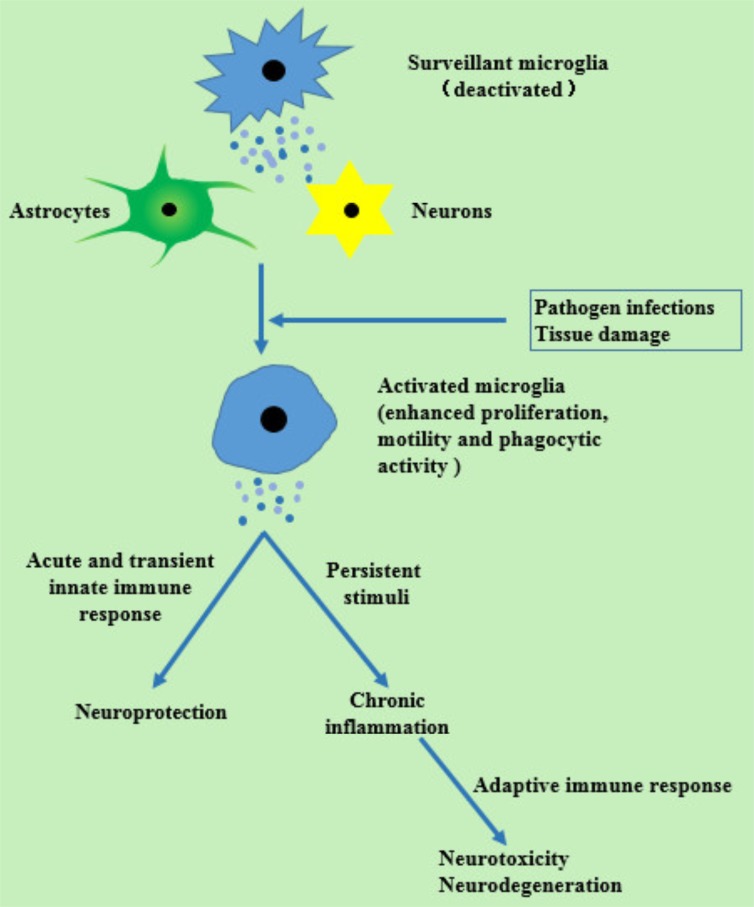

Recent decades have witnessed the high morbidity, mortality and disability rate of stroke [1-3]. In the United States, stroke is the fifth leading cause of death [2]. Moreover, because of the high rate of disability, there are unavoidably high burdens on stroke patients. Among all types of strokes, ischemic ones are the most prevalent type. Unfortunately, until now only thrombolysis therapy with recombinant tissue plasminogen activator (rt-PA) has been identified effective against ischemic stroke [4, 5]. At worst, the narrow time window (within 4.5h after onset) and the reperfusion injury have largely limited the clinical application of rt-PA intravenous thrombolysis [6]. Hence, other potential therapies are urgently needed. Inducing the endogenous protective mechanism to alleviate cerebral ischemic damage, as a result, come into our view. Neuronal death resulted from cerebral ischemia, will induce post-stroke neuroinflammation, which is a double-edged sword. On one hand, cell debris can be removed and repairs can be facilitated by an acute and transient immune response. On the other hand, an inflammatory response could contribute to a secondary brain damage. Additionally, when faced with persistent stimulating factors and maladjusted mechanism of inflammatory development, a chronic inflammatory response will take place, and ends up in neurodegenerative, autoimmune or circulatory diseases [7, 8]. Microglia respond earliest to pathogen infections or injuries in Central Nerves System (CNS) [9]. Stimulated by these changes in CNS, microglia transform from a deactivated state to activated, and then recruit other immune cells [10] (Fig. 1). In the pathogenesis of ischemic stroke and reperfusion injury, toll-like receptors (TLRs) play an integral role by initiating an inflammatory cascade in response to stimuli [14-16]. So targeting on TLRs may be a promising therapy for cerebral ischemic stroke.

Fig. (1).

Inflammatory reactions after stimuli with damage and pathogens [10-13]. There are changes of microglia in morphology, phenotype and function after stimuli. Cytokines and reacted oxygen species (respond to tissue injuries) and proinflammatory cytokines, adhesion molecules and free radicals (respond to pathogen infections) are released by activated microglia instead of anti-inflammatory immune factors and neurotropic growth factors which can influence astrocytes and neurons.

2. AN INTRODUCTION OF TLRS

2.1. Functions of TLRs

TLRs, originally called toll proteins, were initially discovered in Drosophila, and identified as receptors necessary for dorsal-ventral patterning during development [17]. Subsequently, they were reported to be protective especially against fungal infection in Drosophila in 1995 through mediating innate immunity [18]. Charles Janeway and Ruslan Medzhitov put forward that a toll protein (named TLR4 later) could activate adaptive immunity by inducing the expressions of NF-κB-controlled genes [19]. TLRs are now recognized as pattern-recognition receptors (PRRs) constituted by a family of type I transmembrane receptors. TLRs can detect pathogen or tissue damage and are involved in the activation of inflammatory responses. Recently, TLRs have been found playing a modulating role in ischemic stroke [20]. Pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) from exogenous sources and damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) from endogenous ones are recognized by TLRs to provoke immune responses and then induce the expressions of proinflammatory mediators [21, 22]. Endogenous ligands may consist of heat shock protein (HSP), high mobility group box 1 protein (HMGB1), eosinophil-derived neurotoxin, surfactant proteins A and D, hyaluronan and fibrinogen [23-26]. (For more ligands see Table 1).

Table 1.

TLRs: location and the ligands.

| Origin of Ligand | Ligands | TLRs | Location | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PAMPs | Bacteria | |||

| Gram-positive bacteria | Peptidoglycan LAM Phenol-soluble modulin |

TLR2 | Cell surface | |

| Triacyl lipopeptides | TLR1 | Cell surface | ||

| LTA | TLR2,TLR6 | Cell surface | ||

| Flagellin | TLR5 | Cell surface | ||

| CpG-containing DNA | TLR9 | Intracellular | ||

| Gram-negative bacteria | Lipoprotein/lipopeptides | TLR1,TLR2 | Cell surface | |

| Atypical LPS Porins |

TLR2 | Cell surface | ||

| LPS | TLR4 | Cell surface | ||

| Flagellin | TLR5 | Cell surface | ||

| CpG-containing DNA | TLR9 | Intracellular | ||

| Viruses | ds-RNA | TLR3 | Intracellular | |

| Envelope protein Fusion protein |

TLR4 | Cell surface | ||

| ss-RNA | TLR7,TLR8 | Intracellular | ||

| Chlamydia | HSP 60 | TLR4 | Cell surface | |

| Mycoplasma | Diacyl lipopeptides | TLR2,TLR6 | Cell surface | |

| Spirochaete | Atypical LPS Glycolipids |

TLR2 | Cell surface | |

| Fungi | Zymosan | TLR2,TLR6 | Cell surface | |

| Parasites | Glycoinositolphospholipids | TLR2 | Cell surface | |

| Synthetic compounds | Poly I:C | TLR3 | Intracellular | |

| Taxol | TLR4 | Cell surface | ||

| Imidazoquinoline | TLR7,TLR8 | Intracellular | ||

| Loxoribine Bropirimine |

TLR7 | Intracellular | ||

| DAMPs | Host | HSP 70 | TLR2,TLR4 | Cell surface |

| Fibrinogen Type III repeat extra domain A of fibronectin Polysaccharide fragments of heparan sulphate Oligosaccharides of hyaluronic acid |

TLR4 | Cell surface | ||

PAMPs: pathogen-associated molecular patterns; DAMPs: damage-associated molecular patterns; LAM: lipoarabinomannan; LTA: lipoteichoic acid; CpG: cytidine phosphate guanosine; LPS: lipopolysaccharide; ds-RNA: double-stranded RNA; ss-RNA: Single-stranded RNA; HSP: Heat-shock protein; Poly I:C: polyinosinic-polycytidylic acid.

2.2. Species and Distributions of TLRs

Thirteen kinds of TLRs have been found so far, among which 11 exist in humans (TLR1-TLR11) and 13 in mice [27, 31, 32]. TLR family members are reported expressed in immune cells such as monocytes/macrophages and dendritic cells [33]. TLRs are also observed existing in a variety of other types of cells, including epithelial cells, vascular endothelial cells, adipocytes, and cardiac myocytes [34]. In addition, nine TLRs have been identified in Nervous System. Neurons, astrocytes and microglia are common cell types which TLRs are located on [35-39].

All contents listed above are summarized according to [27-30].

2.3. Ultrastructure of TLRs

The structures of TLR are characterized by an extracellular leucine-rich repeat (LRR) domain and an intracellular Toll/Interleukin-1 (IL-1) receptor (TIR) domain [17, 19, 40], and are highly conservative both in insects and in humans. The extracellular LRR participates in the selection and binding of ligands derived from pathogens [41]. The central transmembrane domain is the bridge of inner and outer domains [42]. Inside the cells, TIR domain is a conserved cytoplasmic domain [28] and recruits downstream signaling molecules, such as myeloid differentiation primary-response protein 88 (MyD88), tumor-necrosis factor (TNF)-receptor-associated factor 6 (TRAF6), IL-1 receptor-associated kinases (IRAKs) and so on [32, 43].

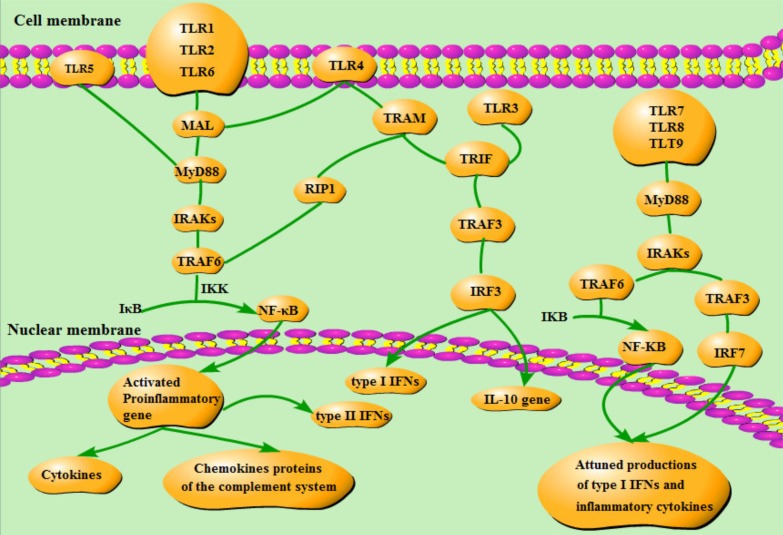

2.4. Two Signaling Pathways

Two signaling pathways (the MyD88-dependent and the MyD88-independent signaling pathways) are utilized in the TLR involved modulations of inflammatory and antiviral responses. Downstream kinases and transcription factors will be activated upon the recruitment of the following four molecules: MyD88, MyD88 adaptor-like protein (MAL, also called TIRAP), the TIR domain-containing adaptor inducing interferon (TRIF) and the TRIF-related adaptor molecule (TRAM) [41] (Fig. 2 shows these two pathways).

Fig. (2).

Two signaling pathways [44-47]. MAL is the bridge connecting TLR1/2/4/6 and MyD88. When MyD88 bound to the receptor, the TIR domain of TLRs can then interact with MyD88. At the same time TIR domains can lead to the phosporylation of the IRAK-1 and -4. Both IRAKs lead to the activation and polyubiquitination of the oligomer itself through interaction with TRAF6. The connection between IRAKS and TRAF6 results in the activation of inhibitor of NF-κB (IκB) kinase (IKK), which frees NF-κB from IκB. NF-κB will translocate to the nucleus, and activate some proinflammatory genes. TRAM is necessary for TLR4 but not for TLR3 in TRIF signaling pathway. TRAF3 activated by TRIF will make IRF3 phosphorylated. Phosphorylated IRF3 will translocate into the nuclear to induce type I IFNs and activate IL-10 gene. TRIF can also influence NF-κB through RIP1 and TRAF6. Except for interacting with TRAF6, TLR7, 8 and 9 can also take part in anti-inflammation effects by interacting with TRAF3.

2.4.1. MyD88-dependent Signaling Pathway

The MyD88-dependent pathway signals include MyD88, IRAKs, and TRAF6, which ultimately lead to the activation of nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB). All TLRs except TLR3 can utilize the MyD88 signaling pathway. The MyD88-dependent signaling pathway begins with the activation of the TIR domain. Upon connecting to MAL, MyD88, IRAKs and TRAF6, TLRs can set free of NF-κB [44]. This pathway will eventually activate some proinflammatory genes, which encode cytokines, chemokines proteins of the complement system and immune receptors [45], to initiate inflammatory responses as well as the innate immune response [46].

Since almost all TLRs except TLR3 function through Myd88-dependent pathway and TLR4 acts mainly on it, it will be emphasized in the following text.

2.4.2. MyD88-independent Signaling Pathway

As to the MyD88-independent signaling pathway, a so-called TRIF signaling pathway, it can only react to TLR3 and TLR4. TRIF is recruited directly by TLR3 while the adaptor protein TRAM is necessary for TLR4. Therefore, TLR4 can bind both MyD88 (with the help of MAL) and TRIF (via TRAM). After the activation of TRAF3 by interacting with TRIF, interferon (IFN) regulatory factor 3(IRF3) will be phosphorylated [44], and then translocated into nucleus to play a proinflammatory role.

Activation of TRAF6 and receptor interacting protein 1 (RIP1) recruited by TRIF can also enable the NF-κB pathway [46]. Besides, TLR7, TLR8 and TLR9 have the ability to attune the productions of type I IFNs and inflammatory cytokines via either IRF7 or NF-κB [47].

3. TLR IN CEREBRAL ISCHEMIA

Many researches have been conducted to detect the role TLRs play in cerebral ischemia. Whether they are responsible for the development of ischemic injury has aroused many attentions.

3.1. TLRs Expression and Ischemic Stroke

Most types of TLRs are upregulated after onset of cerebral ischemia. A study posed that the expressions of TLR4 and TLR5 were raised in the animal trails after permanent occlusion of the middle cerebral artery (pMCAO) [48]. Hyakkoku et al. met the same conclusions that TLR4 actively increased in post-stroke animal models [49]. The levels of TLR1 and TLR2 were also reported rising in injured areas of the brain [50]. These observations, in other manner, confirmed that intervention and regulations of TLRs might bring benefit to ischemic stroke.

TLR2 and TLR4 are the two subjects under extensive studies. In animal trials, a decreased lesion size was measured in TLR4 deficient mice compared with wild types, no matter in the ischemia/reperfusion (I/R) models [51, 52], or in the models of pMCAO [14]. Contradictory results were observed on TLR2. Teams of Lehnardt and Ziegler both had drawn the conclusion that TLR2 produced a detrimental spike in I/R injuries [15, 53]. On the contrary, Hua et al. held the view that TLR2 had a protective effect because increased infarct volume and mortality were observed in TLR2 knockout (KO) mice [46]. It may be the different time points chosen to observe the infarct volume that made the different outcomes. In fact, a subsequent exacerbation of the damaged area had been measured in TLR2 KO mice, suggesting that the deficiency of TLR2 delayed the evolution of ischemic damage [54].

3.2. TLRs and Cerebral Ischemia Outcome

TLR7 and TLR8 on admission were reported correlating with IL-6 and IL-1β, suggesting that TLR7 and TLR8 are involved in the activation of the inflammatory responses [55]. Remarkably, more detections of TLR7 and TLR8, not TLR3 or TLR9, were associated with poor outcomes in ischemic stroke patients [55]. In vitro data also indicated that the activation of TLR8 aggravated ischemic brain insults [56]. TLR7 and TLR8 can be thereby considered as biomarkers of evil outcomes for acute ischemic stroke patients. However, the exact mechanisms how TLR7 and TLR8 involve in remain to be clarified. In addition, clinical data have demonstrated that increased levels of TLR2 and TLR4 may be associated with a poorer prognosis [16, 55, 57, 58]. In regard to TLR3, although no effects on lesion size have been found in TLR3 KO mice after I/R injuries [49], researches have shown that TLR3-mediated TRIF-dependent IFN signaling may exert a protective effect. Similar to TLR3, there has been no evidence to show the role of TLR9 playing in ischemic injuries [49, 53].

4. POTENTIAL MEDICATIONS OR COMPOUNDS ACTING ON TLRS to promote ischemiC DAMAGE RECOVERY

Given that TLRs play an essential role in the inflammatory processes of ischemic stroke and I/R injury, pharmacological modulation of TLR activation has shown a significant therapeutic potential against cerebral ischemia.

4.1. Inhibitions of TLR4

In recent years, considerable interest has been aroused in understanding the role of TLR4 in the processes of inflammation after ischemic infarction. Since TLR4 may exacerbate the damage of inflammation, many researches have been conducted to suppress the expression of TLR4 or inhibit the TLR4 signaling pathway.

4.1.1. Acting on Upstream Signaling

Some reports suggested that HMGB1 released rapidly from damaged cells after stroke onset and may interact with TLR4 receptors in adjacent brain, thus raising the level of matrix metalloproteinase 9 (MMP-9) and exaggerating ischemic brain injury [23, 59]. Mediators of the HMGB1/TLR4 signaling pathway may be novel therapeutic methods for ischemic stroke. Therefore, tanshinone II A [60], glycyrrhizin [61] and atorvastatin [62] were raised to have the ability to attenuate the over-expressions of HMGB1 and TLR4. By suppressing miR-155 expression, acetylbritannilactone may downregulate TLR4 and upregulate the expressions of suppressor of cytokine signaling 1 (SOCS1) and MyD88 to exert its anti-inflammatory effect [63]. Dioscin restrained the expression and the cytosolic translocation of HMGB-1 to downregulate the expression of TLR4 [64]. Intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIg) could protect neurons from death induced by HMGB1 via modulating TLR and receptor for advanced glycation endproducts (RAGE) expressions, resulting in decreased expressions of TLR2, TLR4, TLR8, RAGE and pro-apoptotic caspase-3 cleavage, and inhibited phosphorylations of the cell apoptotic-associated kinases and the p65 subunit of NF-κB. Anti-apoptotic protein B-cell lymphoma 2 (Bcl-2) was elevated additionally [65]. In a rat MCAO model, tetramethylpyrazine could alleviate neutrophil migration, endothelium adhesion and nitric oxide (NO) production. In parallel, activations of inflammation-associated signaling molecules, like plasma HMGB1 and neutrophil TLR4, protein kinase B (PKB, a.k.a Akt), extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) and inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) were suppressed [66]. All candidates above are easily obtained and several have been applied in the treatments after ischemicstroke, so they may be practicaltherapeutic methods.

4.1.2. Acting on TLR4 and Downstream Effectors

A lot of medicine or compounds have been detected to downregulate the expression of TLR4. For example, Anti-TLR4-Antibody MTS510 exerted its positive effect on improving neurological performance and reducing infarct volumes and brain swelling [67].

Apart from decreased expression of TLR4, different downstream proinflammatory mediatorshave been studied to downregulate at the same time. For instance, curcumin attenuated the expressions of TLR4, TNF-α, IL-1β and NF-κB, in order to inhibit apoptosis and inflammation [68]. MicroRNA (miR)-181c could not only suppress the expression of TLR4 by directly binding its 3’-untranslated region but also inhibit NF-κB activation and productions of downstream like TNF-α, IL-1β, and iNOS [69]. Baicalin might lessen the expressions of TLR4 and NF-κB, reduce the expressions and activities of iNOS and cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) [70]. Table 2 summarizes other medicine or compounds acting on both TLR4 and downstream proinflammatory mediators. All candidates listed in Table 2 have been studied only in laboratory, but some of them (some traditional Chinese medicine and other common western medicine) are applied in clinical treatments frequently. Therefore, more studies needs to be carried out to evaluate whether they are practical therapeutic methods. Albumin has been applied in treatments of other diseases, so whether it is benefit for ischemic stroke patients need to be verified. With regard to ADMSC, the safety and feasibility of stem cell treatment are still unclear.

Table 2.

Medicine or compounds acting on both TLR4 and downstream proinflammatory mediators.

| Medicine or Compounds | Models | Effects | Refs. | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| miR-181c | OGD | Decreased expressions of TLR4, NF-κB, TNF-α, IL-1β, and iNOS | [69] | ||||

| Picroside 2 | MCAO | Decreased expressions of TLR4, NF-κB and TNF-α | [71] | ||||

| Albumin | MCAO | Decreased expression of TLR4 Increase expressions of IL-10, TGF-β1 and Treg cells |

[72] | ||||

| Baicalin | MCAO | Decreased expressions of TLR2, TLR4 and NF-κB Decreased expressions and activations of iNOS and COX-2 |

[70] | ||||

| In vitro OGD/R and in vivo ligating carotid arteries | Decreased expressions of TLR2, TLR4 and TNF-α | [73] | |||||

| Candesartan and glycyrrhizin |

MCAO | Reduced increased expressions of TLR2, TLR4, MyD88, TRIF, IRF3, TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6 and NF-κB |

[74] | ||||

| Cinnamaldehyde | MCAO | Decreased expressions of TLR4 and TRAF6 Decreased nuclear translocation of NF-κB |

[75] | ||||

| Curcumin | pMCAO | Decreased expressions of TLR2, TLR4, TNF-α and IL-1β Decreased expression and activity of NF-κB |

[68] | ||||

| D-4F | pMCAO | Increased MBP and IGF1 Decreased expressions of TLR4 and TNF-α |

[76] | ||||

| Dioscin | In vitro OGD/R and in vivo MCAO | Blockade of the TLR4/MyD88/TRAF6 signaling pathway | [64] | ||||

| Fructus mume | BCCAo | Reduced increased expressions of COX-2, IL-1β and IL-6, as well as the activations of TLR4/MyD88 and p38 MAPK signaling | [77] | ||||

| Fullerenol and glucosamine-fullerene conjugates | tMCAO | Ameliorated neurological symptoms Decreased expressions of IL-1β and TLR-4 |

[78] | ||||

| Geniposide | In vitro OGD and in vivo MCAO | Reduced the infarct volume and inhibited the activations of microglial cells Decreased expressions of TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8 and IL-10, reduced increased expressions of TLR4 mRNA and protein levels, inhibitedphosphorylations of ERK, IκB and p38, and nuclear transcriptional activity of NF-κB p65 |

[79] | ||||

| Hydroxysafflor yellow A | MCAO | Decreased expressions of TLR4, TNF-α, IL-1β and NO Inhibited phosphorylations of NF-κB, p-p65, ERK1/2, JNK and p38 |

[80] | ||||

| Isoquercetin | OGD/R | Decreased expressions of TLR4, NF-κB, and mRNA expression of TNF-α and IL-6 Deactivations of ERK, JNK and p38, and inhibition of activity of caspase-3 |

[81] | ||||

| Ligustilide | MCAO | Decreased expression of TLR4 Inhibited phosphorylation of ERK1/2 and transcriptional activities of NF-κB and STAT3 |

[82] | ||||

| Luteolin | pMCAO | Decreased expressions of TLR4, TLR5, NF-κB and p38 MAPK Increased expression of ERK |

[48] | ||||

| Propyl gallate | MCAO | Decreased transcriptions and expressions of TLR-4 and HSP70 Inhibited activity of NF-κB and decreased expressions of COX-2 and TNF-α |

[83] | ||||

| Neamine | MCAO | Decreased nuclear angiogenin, RAGE number and reduced TLR4 positive area Inhibited NF-kB activity Increased expression of angeopoietin-1 |

[84] | ||||

| Bicyclol | pMCAO | Decreased expressions of TLR4, TLR9, TRAF6, NF-κB and MMP-9 Increased expression of claudin-5 |

[85] | ||||

| Rhynchophylline | pMCAO | Ameliorated neurological deficits, infarct volume and brain edema Activation of PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling while inhibition of TLRs/NF-κB pathway Increased expressions of claudin-5 and BDNF Decreased expressions of TLR2, TLR4, MyD88 and inhibition of NF-κB p65 translocation |

[86] | ||||

| Medicine or Compounds | Models | Effects | Refs. | ||||

| Oxymatrine | MCAO | Decreased expressions of TLR4, TLR2, MyD88 and NF-κB | [87] | ||||

| Resatorvid | MCAO | Reduced infarct area and volume in a doserelated manner Inhibition of oxidative/nitrative stress and neuronal apoptosis Inhibition of TLR4 signaling Decreased expressions of NOX4, phospho-p38, NF-κB, and MMP-9, and inhibited phosphorylations of p38 and c-jun |

[88] | ||||

| Shikonin | MCAO | Improved neurological deficit and BBB permeability Reduced infarct volume and edema Decreased expressions of pro-inflammatory mediators, and inhibited phosphorylations of p38 MAPK and over-expression of MMP-9 Increased expression of claudin-5 |

[89] | ||||

| Salvia miltiorrhiza | BCCAo | Attenuated activation of microglial cells Decreased expressions of TNF-α, IL-1β and IL-6 Elevated decreased levels of MBP |

[90] | ||||

| Salvianolic acid B | In vitro OGD/R and in vivo MCAO | Increased viability of primary cortical neurons Ameliorated release of NeuN Inhibition of the TLR4/MyD88/TRAF6 pathway Inhibited transcriptional activity of NF-kB and decreased expressions of IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α |

[91] | ||||

| TAK-242 | tMCAO | Reduced cerebral infarction and improved neurologic function Inhibited phosphorylations of downstream protein kinases, and decreased expressions of inflammatory cytokines |

[92] | ||||

| ADMSC | Occlusion of distal left internal carotid artery | Limited brain infarction area and improved sensorimotor dysfunction Decreased mRNA expressions of Bax, caspase 3, IL-18, TLR-4 and PAI-1 Increased Bcl-2, IL-8/Gro, CXCR4, SDF-1, vWF and doublecortin |

[93] | ||||

OGD: oxygen-glucose deprivation; MCAO: Middle Cerebral Artery Occlusion; pMCAO: permanent middle cerebral artery occlusion; tMCAO: transient middle cerebral artery occlusion; iNOS: inducible nitric oxide synthase; NO: nitric oxide; Treg cells: regulatory T lymphocytes; COX-2: cyclooxygenase-2; IGF1: insulin-like growth factor-1; OGD/R: oxygen–glucose deprivation and reoxygenation; AP-1: jun oncogene; MAPK: mitogen- activated protein kinase; STAT3: signal transducer and activator of transcription 3; BCCAo: permanent bilateral common carotid artery occlusion; ERK: extracellular regulated protein kinases; IκB: inhibitor of NF-κB; JNK: c-Jun N-terminal kinase, also named stress-activated protein kinase (SAPK);RAGE: receptor for advanced glycation endproducts; T1DM: Type one diabetes;BDNF: brain-derived neurotrophic factor; MMP-9: matrix metalloproteinase 9; NOX: NADPH oxidase; BBB: blood–brain barrier; MBP: myelin basic protein; ADMSC: adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cell; PAI-1: plasminogen activator inhibitor-1; SDF-1: stromal-cell derived factor-1; CXCR4: chemokine receptor-4; vWF: von Willebran factor.

Mediations on different downstream elements of the TLR4 pathway have also come into scientific focuses. VELCADE in combination with tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) can increase miR-l46a levels, resulting in the decrease of vascular IRAK1 immunoreactivity, which may provide neuroprotective effects against acute stroke [94]. Through mediating the regulation of NF-κB and signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3), argon reduce the expression of IL-8 in neuroblastoma cells and in rat retina [95]. Ginkgolide B may downregulate the expression of NF-κB and pro-apoptotic proteins to inhibit the PI3K/Akt pathway and TLR4/NF-κB pathway, coincide with the elevated expressions of sirt1, heme oxygenase 1 and anti-apoptotic protein, the incremental secretion of erythropoietin and the improvement of endothelial NO synthesis [96]. MiR-203 could negatively regulate MyD88. Furthermore, negative feedback that upregulated the expression of miR-203 or MyD88 small interfering RNA (siRNA) silencing could suppress downstream NF-κB signaling and microglia activation [97]. Candidates above need more trails to testify their curative effects. Argon is cheap and widely used in industry. Its advantage of treating ischemic stroke may be worth to explore.

In a total of 89 ischemic stroke patients and 166 controls observation, aspirin reduced the IL-8 expression after stroke [98]. Aspirin is used in almost all ischemic stroke patients without other contra-indications, so more clinical researches are needed to verify its anti-inflammatory effect.

As introduced above, TLR4 is the only receptor which can utilize both MyD88 and TRIF signaling pathways. However, the majority of therapeutic candidates were found affecting on the MyD88 signaling pathway, while candesartan and glycyrrhizin had the ability to suppress the two classical pathways. None was found exerting protective effect only through inhibiting the TRIF pathway.

4.1.3. Preconditioning with TLR4 Ligands or other Compounds

An idea has been put up that immune tolerance induced by a small dose of TLR ligands may be a novel therapy to protect brain from cerebral ischemic damage. With LPS preconditioned, a noticeable upregulation of type I IFN-associated genes following MCAO was appeared. Inhibitors of NF-κB, such as Ship1, Tollip, and p105 acted the same. Combination with the inhibited activity of NF-κB p65, LPS preconditioning provided neuroprotection by redirecting TLR4 signaling and enhancing the TLR4/TRIF/IRF3 signaling pathway [99]. In the preterm ovine fetal brain, an up-regulation of TLR4, TLR7 and IFN-β mRNA and plasma IFN-β concentrations was associated with repeated low-dose LPS preconditioning, resulting in reduced cellular apoptosis, inhibited microglial activation and reactive astrogliosis in response to hypoxia-ischemia (HI) injury [100]. On the basis of LPS preconditioning, Gong et al. studied the function of LPS response gene (Lrg). Lrg-siRNA in mice after MCAO gave rise to IRAK1 and NF-κB p65 protein, and decreased the IRF3 protein level [101]. So, inhibition of Lrg may be a promising therapeutic target to regulate TLR4 signaling pathway (Table 3 summarized several gene regulations on TLRs). Apart from pretreatment with LPS, preconditioning with recombinant high-mobility group box 1 (rHMGB1) could increase the expression of IRAK-M after I/R injury, and then inhibit the phosphorylation of IRAK-1 [103].

Table 3.

Gene regulation on TLRs.

| Regulation | TLR | Effects | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acetylbritannilactone | TLR4 | Inhibited expressions of miR-155 and TLR4 Upregulated expressions of SOCS1 and MyD88 |

[63] |

| Geniposide | TLR4 | Reduced increased expressions of TLR4 mRNA and protein levels, downregulated phosphorylations of ERK, IκB and p38, and inhibited nuclear transcriptional activity of NF-κB p65 | [79] |

| VELCADE in combination with tPA | TLR4 | Increased miR-l46a levels Decreased vascular IRAK1 immunoreactivity |

[94] |

| LPS pretreatment | TLR4, TLR7 | Upregulation of TLR4, TLR7 and IFN-β mRNA and IFN-β concentrations | [100] |

| Lrg-siRNA | TLR4 | Increased IRAK1 and NF-κB p65 protein Decreased IRF3 protein level |

[101] |

| CpG pretreatment | TLR9 | Activated natural killer cell-associated genes and the GATA-3 transcriptional regulatory element Upregulated type I interferon-associated genes, and transcriptional regulatory elements |

[102] |

SOCS1: suppressor of cytokine signaling 1;tPA: tissue plasminogen activator; IRAK1: IL-1 receptor-associated kinases 1;LPS: lipopolysaccharide; Lrg: LPS response gene; IRF3: interferon regulatory factor 3.

Except pretreatment with TLR4 ligands, preconditioning with pituitary adenylate cyclise-activating polypeptide (PACAP) also exerted a neuroprotective effect by suppressing the activation of the TLR4/MyD88/NF-κB signaling pathway, the expression of inflammatory cytokines, and the apoptosis in microglia [104]. Isoflurane (ISO) preconditioning reduced the up-regulation of TLR4 and inhibited the activation of JNK and NF-κB, as well as the production of TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6 and NO [105]. Subsequently, alleviated neurological deficits and neuronal apoptosis, reduced the infarct volume, and inhibited microglial activation were observed in the ischemic penumbra induced by ISO preconditioning. Furthermore, there were decreased expression of HSP 60, TLR4 and MyD88 and increased expression of IκB-α in vivo, coinciding with less expressions of TLR4, MyD88, IL-1β, TNF-α and Bax, elevated expression of IκB-α and Bcl-2 in vitro. CLI-095, a specific inhibitor of TLR4, had the same effect with isoflurane on attenuating neuronal apoptosis induced by microglial activation [106]. Xiao et al. had also observed decreased expression levels of TLR4, MyD88 and NF-κB [107]. In MCAO rats, tongxinluo pretreatment reduced brain edema and AQP4 expression, while restrained the activation of microglia, HMGB1, TLR4, NF-κB and

Many candidates had shown their neuroprotective effects by regulating the expressions of signaling effectors, so we only made a brief description on some typical gene regulations in Table 3 to avoid lengthiness and duplications.

TNF-α [108]. Pretreatment induced immune tolerance is a potential therapy against ischemic stroke and worth of more researches. (Table 4 summarized pretreatments acting on all TLRs).

Table 4.

Preconditioning with TLR ligands or compounds.

| Pretreatment | Models | TLR | Effects | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LPS | MCAO | TLR4 | Upregulation of anti-inflammatory and type I IFN-associated genes, increased expression of NF-κB inhibitors No differential modulation in pro-inflammatory genes |

[99] |

| HI | TLR4, TLR7 | Upregulation of TLR4, TLR7 and IFN-β mRNA and plasma IFN-β concentrations | [100] | |

| rHMGB1 | MCAO | TLR4 | Reduced neurological deficits, brain swelling, infarct size and BBB permeability Increased IRAK-M |

[103] |

| PACAP | OGD/R | TLR4 | Inhibited upregulation of TLR4, MyD88 and NF-κB Reduced production of proinflammatory cytokines and apoptosis |

[104] |

| isoflurane | OGD | TLR4 | Inhibited upregulation of TLR4 and activation of JNK and NF-κB Reduced proinflammatory productions |

[105] |

| In vitro OGD and in vivo I/R | TLR4 | Reduced infarct volume, apoptosis and weakened microglial activation Decreased TLR4, MyD88 and neuroinflammation |

[106] | |

| MCAO | TLR4 | Weakened astrocyte and microglial activation Decreased expressions of TLR4, MyD88 and NF-κB |

[107] | |

| Tongxinluo | MCAO | TLR4 | Decreased brain edema and lesion volume ratio and downregulated AQP4 expression Inhibited the activation of microglia, HMGB1, TLR4, NF-κB and TNF-α |

[108] |

| Pam3CSK4 | MCAO | TLR2 | Reduced brain infarct size, acute mortality, brain edema and loss of the tight junction protein occludin Preserved BBB function |

[109] |

| MCAO | TLR2 | Reduced infarct size and neuronal damage Increased Hsp27, Hsp70, and Bcl2 Decreased Bax and inhibited NF-κB-binding activity |

[110] | |

| Poly I:C | In vitro OGD/R and in vivo MCAO | TLR3 | Inhibited astrocyte proliferation, reactive astrogliosis and reduced brain infarction volume Upregulated TLR3 expression IFN-β and downregulated IL-6 |

[111] |

| MCAO | TLR3 | Reduced the infarct volume, neuronal damage Promoted IRF3 phosphorylation Inhibited activations of NF-κB, caspase-3 and -8 and interaction of Fas and FADD |

[112] | |

| chloroquine | tGCI | TLR3 | Enhanced rats' short-term spatial memory capacity Decreased expression of TLR3, IRF3, and IFN-β |

[113] |

| IPC | In vitro OGD and in vivo pMCAO | TLR3 | Reduced brain damage and Increased expression of TLR3 and phosphorylated NF-κB |

[114] |

| CpG ODN | MCAO | TLR9 | Reduced ischemic damage Increased serum TNF-α |

[115], [116] |

| CpG | MCAO | TLR9 | Activated natural killer cell-associated genes and the GATA-3 transcriptional regulatory element Upregulated type I interferon-associated genes, and transcriptional regulatory elements |

[102] |

| GDQ | MCAO | TLR7 | Reduced infarct volume and functional deficits Increased plasma IFN-α |

[117] |

OGD: oxygen-glucose deprivation; MCAO: Middle Cerebral Artery Occlusion; HI: hypoxia-ischemia; BBB: blood–brain barrier; IRAK-M: interleukin-1R-associated kinase-M;PACAP:pituitary adenylate cyclise-activating polypeptide; OGD/R: oxygen–glucose deprivation and reoxygenation; JNK: c-Jun N-terminal kinase; AQP4: aquaporin-4; Poly IC: polyinosinic-polycytidylic acid; poly-ICLC: TLR3 ligand, which consists of carboxymethylcellulose, polyinosinic-polycytidylic acid, and poly-L-lysine double-stranded RNA; tGCI: transient global cerebral ischemia; IRF3: interferon regulatory factor 3; IPC: cerebral ischemic preconditioning; pMCAO: permanent middle cerebral artery occlusion; ODN: oligodeoxynucleotide; GDQ:ardiquimod.

4.1.4. Postconditioning Acting on TLR4

Getting elicitation through the neuroprotective effects of pretreatment against cerebral ischemia, several studies have explored the protective potential of postconditioning. Tongxinluo exerted anti-inflammatory effect via both preconditioning and postconditioning [108]. Poly I:C was also a promising candidate affecting on TLR4 as well as TLR3 [118]. Additionally, remote ischemic postconditioning was suggested to significantly ameliorate neurological deficits and reduce infarct volume, with decreased overexpression of TLR4 and NF-κB [119]. Postconditioning is a novel way to study therapeutic methods and more evidences are needed.

4.1.5. Other Methods Acting on TLR4

Except for medicine or compounds listed above, some studies downregulate TLR4 in other ways. Exercise could reduce the expression of TLR4 and alleviate brain infarct volume [120]. A single treatment of hyperbaric oxygen significantly attenuated edema and improved perfusion [121]. Electroacupuncture on rats was tested to suppress the secretion of inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α, IL-1β and IL-6, via inhibiting of TLR4/NF-κB signaling pathway [122, 123]. Splenectomy in ischemic stroke was suggested to be neuroprotective by inhibiting TLR4/NF-κB inflammatory pathway in MCAO rats [124]. Hypoxia preconditioning could induce brain ischemic tolerance as well [125]. However, splenectomy and hypoxia preconditioning seem to have low feasibility.

4.2. Inhibitions of TLR2

More and more researches have been done to explore therapies acting on TLR2. Since TLR2 aggravates a delayed inflammatory insult, how to downregulate the expression of TLR2 becomes the topic.

4.2.1. Acting on Signalings of TLR2 Signaling Pathway

The same to TLR4, IVIg [65], curcumin [68], baicalin [70], candesartan and glycyrrhizin [74], rhynchophylline [86], oxymatrine [87] and argon [95], performed on TLR2 to protect brain from ischemia as well. Besides, 4, 4'-diisothio-cyanostilbene-2, 2'-disulfonic acid alleviated neuronal injury partially by blocking the TLR2 pathway, ending up with decreased over-expression of IL-1β and attenuated cell death [126]. Increased docosahexaenoic acid intake may also provide anti-inflammation function [127]. Hyaluronan tetrasaccharide administration provided neuroprotective effect via suppressing the activation of NF-κB and downregulating the expression of IL-1β after neonatal hypoxic-ischemic brain damage [128]. Transplantation of mesenchymal stem cells (MSC) could downregulate the expression of proinflammatory gene, CD40 and TLR2, and finally caused a lower activation of NF-κB in macrophage/microglia after cerebral infarction [129]. Furthermore, an additional improved learning-memory function and decreased IL-10 release were observed after MSC transplantation [130]. Guanmaitong tablet, a Chinese patent medicine, suppressed expression of TLR2, ERK, p-ERK, p38, p-p38 and reduced the content of IL-1β and IL-6 in order to protect neurons [131].

4.2.2. Preconditioning with TLR2 Ligands

As to preconditioning with TLR2 ligand, Pam3CSK4, which is TLR2 specific, could reduce brain infarct size, acute mortality and brain edema, in parallel with a maintained function of blood-brain barrier (BBB) with decreased leakage of serum albumin [109]. A further investigation was conducted to suggest that through a TLR2/PI3K/Akt-dependent mechanism, Pam3CSK4 pretreatment could elevate the levels of Hsp27, Hsp70, and Bcl2, and lower Bax levels and NF-κB-binding activity [110].

4.3. Upregulation of TLR3 Exerts Neuroprotective effect after Ischemic Stroke

Several potential medications or compounds acting on TLR3 were also studied, and most researches focused on polyinosinic-polycytidylic acid (Poly I:C).

4.3.1. Poly I:C

Poly I:C, an artificially synthesized analogue of double-stranded RNA, was found to be a possible neuroprotective agent functioning in several mechanisms.

A research [111] found that Poly I:C, TLR3-dependent, could inhibit astrocyte proliferation, upregulate TLR3 expression, increase the level of IFN-β, and downregulate IL-6, which always increases after ischemic stroke. In another study, Poly I:C was reported to play a protective effect against cerebral injury through downregulating TLR4 signaling via TLR3 [99]. Together with LPS, Poly I:C could induce an increase in microglial CLM-1 mRNA levels in vitro [132]. The CLM-1 is associated with the regulation of microglial activation. We suppose that Poly I:C may work in an indirect way inhibiting the microglial activation to promote the neurons restoration after cerebral ischemia.

In addition, Poly I:C treatment could play a role in neuroprotection through modulation of TLR3, as well as by inhibiting NF-κB activation in the brain [112]. Hypoxia/reoxygenation (H/R) induces interaction between Fas and FADD as well as caspase-3 and caspase-8 activation in microglial cells, which cause injury to the brain tissues. In vitro, Poly I:C could prevent it. Poly I:C treatment induced connection between TLR3 and Fas, which impeding the interaction of Fas and FADD. In another way, the above points illustrated the potential effect of Poly I:C on protecting against ischemic stroke via TLR3.

4.3.2. Poly-ICLC

An emerging proof-of-concept studies [133] provided that a TLR3 ligand, which consists of carboxymethylcellulose, polyinosinic-polycytidylic acid, and poly-L-lysine double-stranded RNA (named poly-ICLC) working as an activation of TLR3 in microglia is also neuroprotective. After focal cerebral ischemia, as well as OGD, TLR3 and IL-6 were found downregulated in microglia/macrophage. In another way, the above illustrated that Poly-ICLC could protect TLR3 and IL-6 after ischemia. In vitro, microglia treated with poly-ICLC decreased OGD-induced neuron death, which agreed with the in vivo findings. While Poly-ICLC was reported requiring MDA5 (Melanoma Differentiation-Associated Protein 5), not TLR3, to induce neuroprotection [134]. The chemical modifications of poly-ICLC and Poly I:C were thought to be the cause of the different responses. However, the detailed mechanism still needs to be identified.

4.3.3. Chloroquine

Cui G et al. proved that chloroquine preconditioning of ischemic stroke suppressed inflammatory response [109]. The TLR3/IFR3-IFN-β signaling pathway may involve in the inhibited inflammation after cerebral ischemia, thus letting us considering chloroquine as a potential therapeutic agent for the treatment of stroke. Further investigation is worthy to be done.

4.3.4. Cerebral Ischemic Preconditioning

In addition, Pan LN et al. [110] suggested that cerebral ischemic preconditioning (IPC) might induce ischemic tolerance via activation of the TLR3/TRIF/IRF3 signaling pathway in astrocytes. This reprogramming of TLR3 signaling may exert effects on suppressing the post-ischemic inflammatory response and thus protect against ischemic damage.

4.4. Inhibition of TLR9

CpG oligodeoxynucleotide (ODN) [111], a TLR9 ligand, is thought as a neuroprotection agent against ischemic brain through a mechanism that shares the same elements with LPS preconditioning via TLR4. Otherwise, CpG ODN preconditioning could actively protect both neurons and tissues from ischemic injury coordinating systemic and central immune components [121]. In the evidence of present researches, ODN is the most likely mediator which could exert effect on neuroprotection after cerebral ischemic damage.

4.5. Inhibitions of TLR7

In MCAO models, Philberta Y. Leung, PhD [112] found that Gardiquimod (GDQ) preconditioning might induce neuroprotection through generation of systemic IFN-α, which affected the cerebral endogenous TLR4 response to ischemia stroke. TNF was found independent in the neuroprotective effect of GDQ. Instead, TLR7-induced neuroprotection by preconditioning with GDQ relied on IRF7-mediated induction of IFN-α and signaling through the type I IFN receptor. These findings provide novel targets for therapeutic interventions against ischemic injury.

4.6. Inhibitions of TLR5

Luteolin was previously recognized by a series of biologic effects through anti-inflammatory property in multiple sclerosis and rheumatoid arthritis. Huimin Qiao et al. [48] newly found that luteolin could be therapeutic in cerebral ischemia through targeting on TLR5, NF-κB, p-p38MAPK and p-Erk pathway. The conclusion was drawn by an experiment on pMCAO rats.

5. Different insights

The role that downstream signaling effectors like MyD88 and TRIF play seems to be disputed. For example, a paper held the view that disruption of MyD88 or TRIF was not beneficial in protection against cerebral ischemia [135]. They put up with this insight on the basis of 2 in vitro and 2 in vivo models, and found an unexpected trend without statistically significant [135]. Since TLR2, 4, 5, 7 and 9 are thought to be harmful and trails summarized in this review have shown protective effects through downregulating the MyD88 and NF-κB via the MyD88 signaling pathway, more evidences are needed to clarify whether there is a bad outcome to interrupt the MyD88 signaling pathway. As to the TRIF signaling pathway, TLR3 could utilize it to provoke a protective effect after cerebral ischemia, which was in contrast to TLR4. So, blocking the TRIF signaling pathway may function as neuroprotective role with TLR4 but not with TLR3. In a word, it requires more researches to end this controversy.

CONCLUSION

Innate immunity is ubiquitous and can initialize the response to inflammation. TLR signaling activates the inherent immune cells, contributing to the expressions of proinflammatory cytokines as well as co-stimulatory molecule, which lead the specific immune response. Take into consideration the limit application of rt-PA and the valid methods summarized above, mediation of TLRs is a promising therapy which protect brain from post-stroke neuroinflammatory injury. Not only TLR4 and TLR2 but also other TLRs have been testified to participate in these processes. Additionally, along with the successful efforts on preconditioning, postconditioning deserves more extensive researches. Considering the fact that there is limited amount of studies exploring the potential curative effect of other TLRs, innovative research methods are needed to combat brain injury in cerebral ischemia.

Consent for Publication

Not applicable.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81371840 and 81400970), Hubei Province health and family planning scientific research project (No. WJ2017Q021).

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest, financial or otherwise.

REFERENCES

- 1.Wang W., Jiang B., Sun H., Ru X., Sun D., Wang L., Wang L., Jiang Y., Li Y., Wang Y., Chen Z., Wu S., Zhang Y., Wang D., Wang Y., Feigin V.L. Prevalence, Incidence, and Mortality of Stroke in China: Results from a Nationwide Population-Based Survey of 480 687 Adults. Circulation. 2017;135(8):759–771. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.025250. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.025250]. [PMID: 28052979]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mozaffarian D., Benjamin E.J., Go A.S., Arnett D.K., Blaha M.J., Cushman M., Das S.R., de Ferranti S., Després J.P., Fullerton H.J., Howard V.J., Huffman M.D., Isasi C.R., Jiménez M.C., Judd S.E., Kissela B.M., Lichtman J.H., Lisabeth L.D., Liu S., Mackey R.H., Magid D.J., McGuire D.K., Mohler E.R., III, Moy C.S., Muntner P., Mussolino M.E., Nasir K., Neumar R.W., Nichol G., Palaniappan L., Pandey D.K., Reeves M.J., Rodriguez C.J., Rosamond W., Sorlie P.D., Stein J., Towfighi A., Turan T.N., Virani S.S., Woo D., Yeh R.W., Turner M.B. Heart disease and stroke statistics-2016 update: A report from the american heart association. Circulation. 2016;133(4):e38–e360. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000350. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000350]. [PMID: 26673558]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mokdad A.H., Forouzanfar M.H., Daoud F., Mokdad A.A., El Bcheraoui C., Moradi-Lakeh M., Kyu H.H., Barber R.M., Wagner J., Cercy K., Kravitz H., Coggeshall M., Chew A., O’Rourke K.F., Steiner C., Tuffaha M., Charara R., Al-Ghamdi E.A., Adi Y., Afifi R.A., Alahmadi H., AlBuhairan F., Allen N., AlMazroa M., Al-Nehmi A.A., AlRayess Z., Arora M., Azzopardi P., Barroso C., Basulaiman M., Bhutta Z.A., Bonell C., Breinbauer C., Degenhardt L., Denno D., Fang J., Fatusi A., Feigl A.B., Kakuma R., Karam N., Kennedy E., Khoja T.A., Maalouf F., Obermeyer C.M., Mattoo A., McGovern T., Memish Z.A., Mensah G.A., Patel V., Petroni S., Reavley N., Zertuche D.R., Saeedi M., Santelli J., Sawyer S.M., Ssewamala F., Taiwo K., Tantawy M., Viner R.M., Waldfogel J., Zuñiga M.P., Naghavi M., Wang H., Vos T., Lopez A.D., Al Rabeeah A.A., Patton G.C., Murray C.J. Global burden of diseases, injuries, and risk factors for young people’s health during 1990-2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet. 2016;387(10036):2383–2401. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00648-6. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00648-6]. [PMID: 27174305]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Strokert-PA Stroke Study Group Tissue plasminogen activator for acute ischemic stroke. N. Engl. J. Med. 1995;333(24):1581–1587. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199512143332401. [http://dx. doi.org/10.1056/NEJM199512143332401]. [PMID: 7477192]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carpenter C.R., Keim S.M., Milne W.K., Meurer W.J., Barsan W.G. Thrombolytic therapy for acute ischemic stroke beyond three hours. J. Emerg. Med. 2011;40(1):82–92. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2010.05.009. [http://dx.doi.org/10. 1016/j.jemermed.2010.05.009]. [PMID: 20576390]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shobha N., Buchan A.M., Hill M.D. Thrombolysis at 3-4.5 hours after acute ischemic stroke onset--evidence from the Canadian Alteplase for Stroke Effectiveness Study (CASES) registry. Cerebrovasc. Dis. 2011;31(3):223–228. doi: 10.1159/000321893. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1159/ 000321893]. [PMID: 21178345]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Franceschi C., Campisi J. Chronic inflammation (inflammaging) and its potential contribution to age-associated diseases. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2014;69(Suppl. 1):S4–S9. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glu057. [http://dx. doi.org/10.1093/gerona/glu057]. [PMID: 24833586]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maskrey B.H., Megson I.L., Whitfield P.D., Rossi A.G. Mechanisms of resolution of inflammation: a focus on cardiovascular disease. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2011;31(5):1001–1006. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.110.213850. [http:// dx.doi.org/10.1161/ATVBAHA.110.213850]. [PMID: 21508346]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Griffiths M.R., Gasque P., Neal J.W. The multiple roles of the innate immune system in the regulation of apoptosis and inflammation in the brain. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 2009;68(3):217–226. doi: 10.1097/NEN.0b013e3181996688. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/NEN.0b013e3181996688]. [PMID: 19225414]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lehnardt S. Innate immunity and neuroinflammation in the CNS: the role of microglia in Toll-like receptor-mediated neuronal injury. Glia. 2010;58(3):253–263. doi: 10.1002/glia.20928. [PMID: 19705460]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yang I., Han S.J., Kaur G., Crane C., Parsa A.T. The role of microglia in central nervous system immunity and glioma immunology. J. Clin. Neurosci. 2010;17(1):6–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2009.05.006. [http://dx.doi.org/10. 1016/j.jocn.2009.05.006]. [PMID: 19926287]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Block M.L., Zecca L., Hong J.S. Microglia-mediated neurotoxicity: uncovering the molecular mechanisms. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2007;8(1):57–69. doi: 10.1038/nrn2038. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nrn2038]. [PMID: 17180163]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Waisman A., Liblau R.S., Becher B. Innate and adaptive immune responses in the CNS. Lancet Neurol. 2015;14(9):945–955. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(15)00141-6. [http:// dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(15)00141-6]. [PMID: 26293566]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Caso J.R., Pradillo J.M., Hurtado O., Lorenzo P., Moro M.A., Lizasoain I. Toll-like receptor 4 is involved in brain damage and inflammation after experimental stroke. Circulation. 2007;115(12):1599–1608. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.603431. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106. 603431]. [PMID: 17372179]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lehnardt S., Lehmann S., Kaul D., Tschimmel K., Hoffmann O., Cho S., Krueger C., Nitsch R., Meisel A., Weber J.R. Toll-like receptor 2 mediates CNS injury in focal cerebral ischemia. J. Neuroimmunol. 2007;190(1-2):28–33. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2007.07.023. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/ j.jneuroim.2007.07.023]. [PMID: 17854911]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brea D., Blanco M., Ramos-Cabrer P., Moldes O., Arias S., Pérez-Mato M., Leira R., Sobrino T., Castillo J. Toll-like receptors 2 and 4 in ischemic stroke: outcome and therapeutic values. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2011;31(6):1424–1431. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2010.231. [http://dx.doi. org/10.1038/jcbfm.2010.231]. [PMID: 21206505]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hashimoto C., Hudson K.L., Anderson K.V. The Toll gene of Drosophila, required for dorsal-ventral embryonic polarity, appears to encode a transmembrane protein. Cell. 1988;52(2):269–279. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90516-8. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0092-8674(88)90516-8]. [PMID: 2449285]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lemaitre B., Nicolas E., Michaut L., Reichhart J-M., Hoffmann J.A. The dorsoventral regulatory gene cassette spätzle/Toll/cactus controls the potent antifungal response in Drosophila adults. Cell. 1996;86(6):973–983. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80172-5. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0092-8674(00) 80172-5]. [PMID: 8808632]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Medzhitov R., Preston-Hurlburt P., Janeway C.A. Jr A human homologue of the drosophila toll protein signals activation of adaptive immunity. Nature. 1997;388(6640):394–397. doi: 10.1038/41131. [http://dx. doi.org/10.1038/41131]. [PMID: 9237759]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang Y.C., Lin S., Yang Q.W. Toll-like receptors in cerebral ischemic inflammatory injury. J. Neuroinflam. 2011;8:134. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-8-134. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1742-2094-8-134]. [PMID: 21982558]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mogensen T.H. Pathogen recognition and inflammatory signaling in innate immune defenses. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2009;22(2):240–273. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00046-08. [Table of Contents.]. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/CMR.00046-08]. [PMID: 19366914]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Piccinini A.M., Midwood K.S. DAM Pening inflammation by modulating TLR signalling. 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Yang Q.W., Lu F.L., Zhou Y., Wang L., Zhong Q., Lin S., Xiang J., Li J.C., Fang C.Q., Wang J.Z. HMBG1 mediates ischemia-reperfusion injury by TRIF-adaptor independent Toll-like receptor 4 signaling. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2011;31(2):593–605. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2010.129. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/jcbfm.2010.129]. [PMID: 20700129]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yamada C., Sano H., Shimizu T., Mitsuzawa H., Nishitani C., Himi T., Kuroki Y. Surfactant protein A directly interacts with TLR4 and MD-2 and regulates inflammatory cellular response. Importance of supratrimeric oligomerization. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281(31):21771–21780. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M513041200. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M513041200]. [PMID: 16754682]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Garantziotis S., Li Z., Potts E.N., Lindsey J.Y., Stober V.P., Polosukhin V.V., Blackwell T.S., Schwartz D.A., Foster W.M., Hollingsworth J.W. TLR4 is necessary for hyaluronan-mediated airway hyperresponsiveness after ozone inhalation. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2010;181(7):666–675. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200903-0381OC. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1164/ rccm.200903-0381OC]. [PMID: 20007931]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Research Misconduct Found]

- 26.Smiley S.T., King J.A., Hancock W.W. Fibrinogen stimulates macrophage chemokine secretion through toll-like receptor 4. J. Immunol. 2001;167(5):2887–2894. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.5.2887. [http://dx.doi.org/10.4049/ jimmunol.167.5.2887]. [PMID: 11509636]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.O’Neill L.A. TLRs: Professor Mechnikov, sit on your hat. Trends Immunol. 2004;25(12):687–693. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2004.10.005. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.it. 2004.10.005]. [PMID: 15530840]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Akira S., Takeda K. Toll-like receptor signalling. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2004;4(7):499–511. doi: 10.1038/nri1391. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nri1391]. [PMID: 15229469]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Akira S., Uematsu S., Takeuchi O. Pathogen recognition and innate immunity. Cell. 2006;124(4):783–801. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.02.015. [http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.cell.2006.02.015]. [PMID: 16497588]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Medzhitov R. Toll-like receptors and innate immunity. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2001;1(2):135–145. doi: 10.1038/35100529. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/ 35100529]. [PMID: 11905821]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gangloff M., Weber A.N., Gibbard R.J., Gay N.J. Evolutionary relationships, but functional differences, between the Drosophila and human Toll-like receptor families. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2003;31(Pt 3):659–663. doi: 10.1042/bst0310659. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1042/bst0310659]. [PMID: 12773177]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Takeda K., Kaisho T., Akira S. Toll-like receptors. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2003;21:335–376. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.21.120601.141126. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1146/annurev. immunol.21.120601.141126]. [PMID: 12524386]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Muzio M., Bosisio D., Polentarutti N., D’amico G., Stoppacciaro A., Mancinelli R., van’t Veer C., Penton-Rol G., Ruco L.P., Allavena P., Mantovani A. Differential expression and regulation of toll-like receptors (TLR) in human leukocytes: selective expression of TLR3 in dendritic cells. J. Immunol. 2000;164(11):5998–6004. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.11.5998. [http://dx.doi.org/10.4049/jimmunol.164.11.5998]. [PMID: 10820283]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Akira S., Takeda K., Kaisho T. Toll-like receptors: critical proteins linking innate and acquired immunity. Nat. Immunol. 2001;2(8):675–680. doi: 10.1038/90609. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/90609]. [PMID: 11477402]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Farina C., Krumbholz M., Giese T., Hartmann G., Aloisi F., Meinl E. Preferential expression and function of Toll-like receptor 3 in human astrocytes. J. Neuroimmunol. 2005;159(1-2):12–19. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2004.09.009. [http:// dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jneuroim.2004.09.009]. [PMID: 15652398]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jack C.S., Arbour N., Manusow J., Montgrain V., Blain M., McCrea E., Shapiro A., Antel J.P. TLR signaling tailors innate immune responses in human microglia and astrocytes. J. Immunol. 2005;175(7):4320–4330. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.7.4320. [http://dx.doi.org/10.4049/jimmunol. 175.7.4320]. [PMID: 16177072]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lafon M., Megret F., Lafage M., Prehaud C. The innate immune facet of brain: human neurons express TLR-3 and sense viral dsRNA. J. Mol. Neurosci. 2006;29(3):185–194. doi: 10.1385/JMN:29:3:185. [http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1385/JMN:29:3:185]. [PMID: 17085778]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ma Y., Li J., Chiu I., Wang Y., Sloane J.A., Lü J., Kosaras B., Sidman R.L., Volpe J.J., Vartanian T. Toll-like receptor 8 functions as a negative regulator of neurite outgrowth and inducer of neuronal apoptosis. J. Cell Biol. 2006;175(2):209–215. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200606016. [http://dx. doi.org/10.1083/jcb.200606016]. [PMID: 17060494]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Carty M., Bowie A.G. Evaluating the role of Toll-like receptors in diseases of the central nervous system. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2011;81(7):825–837. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2011.01.003. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.bcp.2011.01.003]. [PMID: 21241665]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rock F.L., Hardiman G., Timans J.C., Kastelein R.A., Bazan J.F. A family of human receptors structurally related to Drosophila Toll. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1998;95(2):588–593. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.2.588. [http://dx. doi.org/10.1073/pnas.95.2.588]. [PMID: 9435236]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bell J.K., Mullen G.E., Leifer C.A., Mazzoni A., Davies D.R., Segal D.M. Leucine-rich repeats and pathogen recognition in Toll-like receptors. Trends Immunol. 2003;24(10):528–533. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4906(03)00242-4. [http://dx. doi.org/10.1016/S1471-4906(03)00242-4]. [PMID: 14552836]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fang Y., Hu J. Toll-like receptor and its roles in myocardial ischemic/reperfusion injury. Med. Sci. Monit. 2011;17(4):RA100–RA109. doi: 10.12659/MSM.881709. [http://dx.doi.org/10.12659/MSM.881709]. [PMID: 21455117]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dunne A., O’Neill L.A. The interleukin-1 receptor/Toll-like receptor superfamily: signal transduction during inflammation and host defense. Sci. STKE. 2003;2003(171):re3. doi: 10.1126/stke.2003.171.re3. [PMID: 12606705]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Downes C.E., Crack P.J. Neural injury following stroke: are Toll-like receptors the link between the immune system and the CNS? Br. J. Pharmacol. 2010;160(8):1872–1888. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.00864.x. [http://dx.doi.org/10. 1111/j.1476-5381.2010.00864.x]. [PMID: 20649586]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zuany-Amorim C., Hastewell J., Walker C. Toll-like receptors as potential therapeutic targets for multiple diseases. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2002;1(10):797–807. doi: 10.1038/nrd914. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nrd914]. [PMID: 12360257]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ostuni R., Zanoni I., Granucci F. Deciphering the complexity of Toll-like receptor signaling. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2010;67(24):4109–4134. doi: 10.1007/s00018-010-0464-x. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00018-010-0464-x]. [PMID: 20680392]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Brown J., Wang H., Hajishengallis G.N., Martin M. TLR-signaling networks: an integration of adaptor molecules, kinases, and cross-talk. J. Dent. Res. 2011;90(4):417–427. doi: 10.1177/0022034510381264. [http://dx.doi. org/10.1177/0022034510381264]. [PMID: 20940366]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Qiao H., Zhang X., Zhu C., Dong L., Wang L., Zhang X., Xing Y., Wang C., Ji Y., Cao X. Luteolin downregulates TLR4, TLR5, NF-κB and p-p38MAPK expression, upregulates the p-ERK expression, and protects rat brains against focal ischemia. Brain Res. 2012;1448:71–81. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2012.02.003. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.brainres.2012. 02.003]. [PMID: 22377454]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hyakkoku K., Hamanaka J., Tsuruma K., Shimazawa M., Tanaka H., Uematsu S., Akira S., Inagaki N., Nagai H., Hara H. Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4), but not TLR3 or TLR9, knock-out mice have neuroprotective effects against focal cerebral ischemia. Neuroscience. 2010;171(1):258–267. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2010.08.054. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/ j.neuroscience.2010.08.054]. [PMID: 20804821]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Stridh L., Smith P.L., Naylor A.S., Wang X., Mallard C. Regulation of toll-like receptor 1 and -2 in neonatal mice brains after hypoxia-ischemia. J. Neuroinflam. 2011;8:45. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-8-45. [http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1186/1742-2094-8-45]. [PMID: 21569241]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cao C.X., Yang Q.W., Lv F.L., Cui J., Fu H.B., Wang J.Z. Reduced cerebral ischemia-reperfusion injury in Toll-like receptor 4 deficient mice. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2007;353(2):509–514. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.12.057. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.12.057]. [PMID: 17188246]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hua F., Ma J., Ha T., Kelley J.L., Kao R.L., Schweitzer J.B., Kalbfleisch J.H., Williams D.L., Li C. Differential roles of TLR2 and TLR4 in acute focal cerebral ischemia/reperfusion injury in mice. Brain Res. 2009;1262:100–108. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2009.01.018. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/ j.brainres.2009.01.018]. [PMID: 19401158]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ziegler G., Harhausen D., Schepers C., Hoffmann O., Röhr C., Prinz V., König J., Lehrach H., Nietfeld W., Trendelenburg G. TLR2 has a detrimental role in mouse transient focal cerebral ischemia. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2007;359(3):574–579. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.05.157. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.05.157]. [PMID: 17548055]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bohacek I., Cordeau P., Lalancette-Hébert M., Gorup D., Weng Y.C., Gajovic S., Kriz J. Toll-like receptor 2 deficiency leads to delayed exacerbation of ischemic injury. J. Neuroinflam. 2012;9:191. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-9-191. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1742-2094-9-191]. [PMID: 22873409]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Brea D., Sobrino T., Rodríguez-Yáñez M., Ramos-Cabrer P., Agulla J., Rodríguez-González R., Campos F., Blanco M., Castillo J. Toll-like receptors 7 and 8 expression is associated with poor outcome and greater inflammatory response in acute ischemic stroke. Clin. Immunol. 2011;139(2):193–198. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2011.02.001. [http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.clim.2011.02.001]. [PMID: 21354862]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tang S.C., Yeh S.J., Li Y.I., Wang Y.C., Baik S.H., Santro T., Widiapradja A., Manzanero S., Sobey C.G., Jo D.G., Arumugam T.V., Jeng J.S. Evidence for a detrimental role of TLR8 in ischemic stroke. Exp. Neurol. 2013;250:341–347. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2013.10.012. [http://dx.doi. org/10.1016/j.expneurol.2013.10.012]. [PMID: 24196452]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Urra X., Villamor N., Amaro S., Gómez-Choco M., Obach V., Oleaga L., Planas A.M., Chamorro A. Monocyte subtypes predict clinical course and prognosis in human stroke. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2009;29(5):994–1002. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2009.25. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/ jcbfm.2009.25]. [PMID: 19293821]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yang Q.W., Li J.C., Lu F.L., Wen A.Q., Xiang J., Zhang L.L., Huang Z.Y., Wang J.Z. Upregulated expression of toll-like receptor 4 in monocytes correlates with severity of acute cerebral infarction. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2008;28(9):1588–1596. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2008.50. [http:// dx.doi.org/10.1038/jcbfm.2008.50]. [PMID: 18523439]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Qiu J., Xu J., Zheng Y., Wei Y., Zhu X., Lo E.H., Moskowitz M.A., Sims J.R. High-mobility group box 1 promotes metalloproteinase-9 upregulation through Toll-like receptor 4 after cerebral ischemia. Stroke. 2010;41(9):2077–2082. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.590463. [http://dx.doi.org/10. 1161/STROKEAHA.110.590463]. [PMID: 20671243]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wang L., Zhang X., Liu L., Cui L., Yang R., Li M., Du W. Tanshinone II A down-regulates HMGB1, RAGE, TLR4, NF-kappaB expression, ameliorates BBB permeability and endothelial cell function, and protects rat brains against focal ischemia. Brain Res. 2010;1321:143–151. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2009.12.046. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.brainres. 2009.12.046]. [PMID: 20043889]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zhang J., Wu Y., Weng Z., Zhou T., Feng T., Lin Y. Glycyrrhizin protects brain against ischemia-reperfusion injury in mice through HMGB1-TLR4-IL-17A signaling pathway. Brain Res. 2014;1582:176–186. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2014.07.002. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.brainres.2014. 07.002]. [PMID: 25111887]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wang L., Zhang X., Liu L., Yang R., Cui L., Li M. Atorvastatin protects rat brains against permanent focal ischemia and downregulates HMGB1, HMGB1 receptors (RAGE and TLR4), NF-kappaB expression. Neurosci. Lett. 2010;471(3):152–156. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2010.01.030. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.neulet.2010.01.030]. [PMID: 20100543]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wen Y., Zhang X., Dong L., Zhao J., Zhang C., Zhu C. Acetylbritannilactone Modulates MicroRNA-155-Mediated Inflammatory Response in Ischemic Cerebral Tissues. Mol. Med. 2015;21:197–209. doi: 10.2119/molmed.2014.00199. [http://dx.doi.org/10.2119/molmed.2014.00199]. [PMID: 25811992]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Tao X., Sun X., Yin L., Han X., Xu L., Qi Y., Xu Y., Li H., Lin Y., Liu K., Peng J. Dioscin ameliorates cerebral ischemia/reperfusion injury through the downregulation of TLR4 signaling via HMGB-1 inhibition. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2015;84:103–115. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2015.03.003. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2015.03.003]. [PMID: 25772012]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lok K.Z., Basta M., Manzanero S., Arumugam T.V. Intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIg) dampens neuronal toll-like receptor-mediated responses in ischemia. J. Neuroinflam. 2015;12:73. doi: 10.1186/s12974-015-0294-8. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/s12974-015-0294-8]. [PMID: 25886362]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Chang C.Y., Kao T.K., Chen W.Y., Ou Y.C., Li J.R., Liao S.L., Raung S.L., Chen C.J. Tetramethylpyrazine inhibits neutrophil activation following permanent cerebral ischemia in rats. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2015;463(3):421–427. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2015.05.088. [http:// dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.bbrc.2015.05.088]. [PMID: 26043690]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Andresen L., Theodorou K., Grünewald S., Czech-Zechmeister B., Könnecke B., Lühder F., Trendelenburg G. Evaluation of the therapeutic potential of anti-TLR4-antibody MTS510 in experimental stroke and significance of different routes of application. PLoS One. 2016;11(2):e0148428. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0148428. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/ journal.pone.0148428]. [PMID: 26849209]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Tu X.K., Yang W.Z., Chen J.P., Chen Y., Ouyang L.Q., Xu Y.C., Shi S.S. Curcumin inhibits TLR2/4-NF-κB signaling pathway and attenuates brain damage in permanent focal cerebral ischemia in rats. Inflammation. 2014;37(5):1544–1551. doi: 10.1007/s10753-014-9881-6. [http://dx. doi.org/10.1007/s10753-014-9881-6]. [PMID: 24723245]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Zhang L., Li Y.J., Wu X.Y., Hong Z., Wei W.S. MicroRNA-181c negatively regulates the inflammatory response in oxygen-glucose-deprived microglia by targeting Toll-like receptor 4. J. Neurochem. 2015;132(6):713–723. doi: 10.1111/jnc.13021. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/ jnc.13021]. [PMID: 25545945]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Tu X.K., Yang W.Z., Shi S.S., Chen Y., Wang C.H., Chen C.M., Chen Z. Baicalin inhibits TLR2/4 signaling pathway in rat brain following permanent cerebral ischemia. Inflammation. 2011;34(5):463–470. doi: 10.1007/s10753-010-9254-8. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10753-010-9254-8]. [PMID: 20859668]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Guo Y., Xu X., Li Q., Li Z., Du F. Anti-inflammation effects of picroside 2 in cerebral ischemic injury rats. Behav. Brain Funct. 2010;6:43. doi: 10.1186/1744-9081-6-43. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1744-9081-6-43]. [PMID: 20618938]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wang M., Wang Y., He J., Wei S., Zhang N., Liu F., Liu X., Kang Y., Yao X. Albumin induces neuroprotection against ischemic stroke by altering Toll-like receptor 4 and regulatory T cells in mice. CNS Neurol. Disord. Drug Targets. 2013;12(2):220–227. doi: 10.2174/18715273113129990058. [http://dx.doi.org/10.2174/18715273113129990058]. [PMID: 23394540]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Li H.Y., Yuan Z.Y., Wang Y.G., Wan H.J., Hu J., Chai Y.S., Lei F., Xing D.M., Du L.J. Role of baicalin in regulating Toll-like receptor 2/4 after ischemic neuronal injury. Chin. Med. J. (Engl.) 2012;125(9):1586–1593. [PMID: 22800826]. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Barakat W., Safwet N., El-Maraghy N.N., Zakaria M.N. Candesartan and glycyrrhizin ameliorate ischemic brain damage through downregulation of the TLR signaling cascade. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2014;724:43–50. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2013.12.032. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ejphar.2013.12.032]. [PMID: 24378346]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Zhao J., Zhang X., Dong L., Wen Y., Zheng X., Zhang C., Chen R., Zhang Y., Li Y., He T., Zhu X., Li L. Cinnamaldehyde inhibits inflammation and brain damage in a mouse model of permanent cerebral ischaemia. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2015;172(20):5009–5023. doi: 10.1111/bph.13270. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/bph.13270]. [PMID: 26234631]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Cui X., Chopp M., Zacharek A., Cui C., Yan T., Ning R., Chen J. D-4F decreases white matter damage after stroke in mice. Stroke. 2016;47(1):214–220. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.115.011046. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1161/ STROKEAHA.115.011046]. [PMID: 26604250]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Lee K.M., Bang J., Kim B.Y., Lee I.S., Han J.S., Hwang B.Y., Jeon W.K. Fructus mume alleviates chronic cerebral hypoperfusion-induced white matter and hippocampal damage via inhibition of inflammation and downregulation of TLR4 and p38 MAPK signaling. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2015;15:125. doi: 10.1186/s12906-015-0652-1. [http://dx. doi.org/10.1186/s12906-015-0652-1]. [PMID: 25898017]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Fluri F., Grünstein D., Cam E., Ungethuem U., Hatz F., Schäfer J., Samnick S., Israel I., Kleinschnitz C., Orts-Gil G., Moch H., Zeis T., Schaeren-Wiemers N., Seeberger P. Fullerenols and glucosamine fullerenes reduce infarct volume and cerebral inflammation after ischemic stroke in normotensive and hypertensive rats. Exp. Neurol. 2015;265:142–151. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2015.01.005. [http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.expneurol.2015.01.005]. [PMID: 25625851]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Wang J., Hou J., Zhang P., Li D., Zhang C., Liu J. Geniposide reduces inflammatory responses of oxygen-glucose deprived rat microglial cells via inhibition of the TLR4 signaling pathway. Neurochem. Res. 2012;37(10):2235–2248. doi: 10.1007/s11064-012-0852-8. [http://dx.doi.org/10. 1007/s11064-012-0852-8]. [PMID: 22869019]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Lv Y., Qian Y., Fu L., Chen X., Zhong H., Wei X. Hydroxysafflor yellow A exerts neuroprotective effects in cerebral ischemia reperfusion-injured mice by suppressing the innate immune TLR4-inducing pathway. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2015;769:324–332. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2015.11.036. [http:// dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ejphar.2015.11.036]. [PMID: 26607471]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Wang C.P., Li J.L., Zhang L.Z., Zhang X.C., Yu S., Liang X.M., Ding F., Wang Z.W. Isoquercetin protects cortical neurons from oxygen-glucose deprivation-reperfusion induced injury via suppression of TLR4-NF-кB signal pathway. Neurochem. Int. 2013;63(8):741–749. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2013.09.018. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.neuint.2013. 09.018]. [PMID: 24099731]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Kuang X., Wang L.F., Yu L., Li Y.J., Wang Y.N., He Q., Chen C., Du J.R. Ligustilide ameliorates neuroinflammation and brain injury in focal cerebral ischemia/reperfusion rats: involvement of inhibition of TLR4/peroxiredoxin 6 signaling. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2014;71:165–175. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2014.03.028. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j. freeradbiomed.2014.03.028]. [PMID: 24681253]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Zheng J.M., Chen X.C., Lin M., Zhang J., Lin Z.Y., Zheng G.Y., Li K.Z. Mechanism of the reduction of cerebral ischemic-reperfusion injury through inhibiting the activity of NF-kappaB by propyl gallate. Yao Xue Xue Bao. 2011;46(2):158–164. [PMID: 21542286]. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Ning R., Chopp M., Zacharek A., Yan T., Zhang C., Roberts C., Lu M., Chen J. Neamine induces neuroprotection after acute ischemic stroke in type one diabetic rats. Neuroscience. 2014;257:76–85. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2013.10.071. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroscience.2013.10.071]. [PMID: 24211797]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Zhang J., Fu B., Zhang X., Chen L., Zhang L., Zhao X., Bai X., Zhu C., Cui L., Wang L. Neuroprotective effect of bicyclol in rat ischemic stroke: down-regulates TLR4, TLR9, TRAF6, NF-κB, MMP-9 and up-regulates claudin-5 expression. Brain Res. 2013;1528:80–88. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2013.06.032. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.brainres.2013.06.032]. [PMID: 23850770]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Huang H., Zhong R., Xia Z., Song J., Feng L. Neuroprotective effects of rhynchophylline against ischemic brain injury via regulation of the Akt/mTOR and TLRs signaling pathways. Molecules. 2014;19(8):11196–11210. doi: 10.3390/molecules190811196. [http://dx.doi.org/10.3390/molecules 190811196]. [PMID: 25079660]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Fan H., Li L., Zhang X., Liu Y., Yang C., Yang Y., Yin J. Oxymatrine downregulates TLR4, TLR2, MyD88, and NF-kappaB and protects rat brains against focal ischemia. Mediators Inflamm., 2009 doi: 10.1155/2009/704706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Suzuki Y., Hattori K., Hamanaka J., Murase T., Egashira Y., Mishiro K., Ishiguro M., Tsuruma K., Hirose Y., Tanaka H., Yoshimura S., Shimazawa M., Inagaki N., Nagasawa H., Iwama T., Hara H. Pharmacological inhibition of TLR4-NOX4 signal protects against neuronal death in transient focal ischemia. Sci. Rep. 2012;2:896. doi: 10.1038/srep00896. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/srep00896]. [PMID: 23193438]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Wang L., Li Z., Zhang X., Wang S., Zhu C., Miao J., Chen L., Cui L., Qiao H. Protective effect of shikonin in experimental ischemic stroke: attenuated TLR4, p-p38MAPK, NF-κB, TNF-α and MMP-9 expression, up-regulated claudin-5 expression, ameliorated BBB permeability. Neurochem. Res. 2014;39(1):97–106. doi: 10.1007/s11064-013-1194-x. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11064-013-1194-x]. [PMID: 24248858]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Kim M.S., Bang J.H., Lee J., Kim H.W., Sung S.H., Han J.S., Jeon W.K. Salvia miltiorrhiza extract protects white matter and the hippocampus from damage induced by chronic cerebral hypoperfusion in rats. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2015;15:415. doi: 10.1186/s12906-015-0943-6. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/s12906-015-0943-6]. [PMID: 26597908]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Wang Y., Chen G., Yu X., Li Y., Zhang L., He Z., Zhang N., Yang X., Zhao Y., Li N., Qiu H. Salvianolic acid B ameliorates cerebral ischemia/reperfusion injury through inhibiting TLR4/ MyD88 signaling pathway. Inflammation. 2016;39(4):1503–1513. doi: 10.1007/s10753-016-0384-5. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10753-016-0384-5]. [PMID: 27255374]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]