Abstract

Objective:

An important determinant of job satisfaction and life fulfillment is the quality of life (QOL) of the individuals working in a particular field. Currently, in the United Arab Emirates (UAE), there is limited research pertaining to the QOL of dentists. The main objective of this study was to assess QOL of dentists in the UAE.

Materials and Methods:

The World Health Organization (WHO) QOL-BREF questionnaire (the World Health Organization abbreviated instrument for QOL assessment), which assesses QOL in physical, psychological, social, and environmental domains, was found to be a suitable instrument for use. A total of 290 questionnaires were distributed to general dental practitioners and specialists working in the private sector. The response rate was 46%. The completed questionnaires were coded and analyzed using the SPSS IBM software version 21.

Results:

QOL of specialists was significantly better than general practitioners (GPs) on all domains of the WHOQOL-BREF (P < 0.05). Married dentists had better QOL than singles on the social and environmental domains. Furthermore, specialists reported significantly better QOL compared to GPs after adjustment for sex, age, and marital status (P < 0.05) in the psychosocial and environmental domains.

Conclusions:

Among dentists who work in the UAE, QOL can be affected by several factors, one of them being whether dentist is a GP or a specialist.

Keywords: Dentists, job satisfaction, quality of life

INTRODUCTION

Quality of life (QOL) is an increasingly deliberated topic; it can be defined as a subjective attitude toward the outcome of mental, physical, and social well-being, which in turn, is part of cultural, social, and environmental welfare. It has been generally agreed that job satisfaction among physicians is declining and that affects the quality of working life.[1] All health-care workers (HCWs) are recognized as a vulnerable group, due to their exposure to a number of hazards, namely ergonomic, physical, chemical, biological, and psychosocial at the workplace. Moreover, HCWs were selected as a priority group for improvement of safety and health at work in the World Health Organization (WHO) work plan 2009–2012 (priority 1.4).[2] Since the 21st century, dentists' QOL has become a major concern due to the fact that dentists nowadays need to exert an enormous amount of physical and mental effort in order to keep up with patients' increasing demands for precise and efficient treatment, along with rapidly progressing stream of knowledge and technology.

Dentistry is a profession where several occupational factors affect dentists' well-being. Physical and psychological disorders were found to be of high prevalence in dental practice as shown in several studies.[3,4,5] Some of the consistent predictors of mental health were time and scheduling demands such as working under time pressure and negative patient perceptions, such as being underrated by patients and lack of their appreciation.[3] Income-related issues such as working hard to meet lifestyle demands and conflicts between profits and professional ethics are other factors affecting dentists' mental well-being.[6] The repetitive nature of the job, uncooperative patients, long working hours, and unsatisfactory staff and auxiliary help have also been included as stressors among dentists.[7,8] Furthermore, the relationship of four traits such as self-esteem, generalized self-efficacy, locus of control, and emotional stability with job satisfaction and job performance are found to significantly affect both job satisfaction and job performance.[9]

Job stress is known to have a deleterious effect on general health and has been associated with a range of health disorders such as psychological difficulties, coronary heart disease, and signs and symptoms of musculoskeletal disorders. Work-related musculoskeletal disorders (WRMDs) contribute to approximately 40% of all treatment costs of work-related injuries.[10] These are the most costly type of work disability which negatively affects QOL and reduces productivity. Due to the multifactorial nature of WRMDs, it was found that the most frequently reported risk factors include working for long periods of time in the same position, working in uncomfortable or restricted positions, and treating a large number of patients per day.[11]

There is a paucity of studies focusing on the QOL of dentists in general. The aim of this study is to evaluate the perception of QOL of dental professionals working in the private sector and to determine the factors that affect their QOL.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The WHO for QOL Assessment-BREF (WHOQOL-BREF),[12,13] an abbreviated version, addresses four domains of QOL (social relationships, environmental factors, physical health, and psychological health) and two items which measure overall QOL and general health. This self-administered questionnaire uses a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (not at all) to 5 (completely), measuring intensity (not at all to an extreme amount), capacity (not at all to completely), frequency (never to always), and evaluation (very satisfied to very dissatisfied and very poor to very well).[14] The general QOL was determined from the response to the question of the WHOQOL-BREF, “How would you rate your QOL?” The five response options include very poor, poor, neither poor nor good, good, and very good. The responses were grouped into two levels: good QOL (very good and good) and poor (neither poor nor good, poor, and very poor).[13] Due to cultural considerations, a question related to the dentists' sexual life was eliminated (Q no. 21). The participants were instructed to answer the questions according to what they felt in the last 2 weeks.

A total of 290 surveys were administered to general practitioners (GPs) and specialists working in private sector in the Emirates of Abu Dhabi, Dubai, and Sharjah. Written consent to carry out this study was obtained from each participant prior to commencement. Each participant was instructed to answer the entire questionnaire at a single go while in a calm state after finishing their daily duties in order to avoid bias due to the dentists' mood being affected by daily stresses. The completed questionnaires were collected after a week in order to give ample time for completion. The study was conducted in full accordance with the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki and received ethical approval from the Research and Ethics committee of College of Dental Medicine, University of Sharjah. Data were entered and the scores of the 26-item questions were initially measured on a scale of 4–20, and these were converted to a scale of 100 in order to make the results comparable to studies which employ the WHOQOL-100 questionnaire. Data were analyzed using SPSS IBM version 21 (IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 21.0, IBM Corp: Armonk, NY). Descriptive statistics were utilized, and frequencies, means, and standard deviations were reported. Independent t-tests were used to assess the association between each of the domains and the independent variables. Multivariate regression analysis was conducted to assess the association between each of the domains and the independent variables in the study (age, sex, marital status, and type of practice). For all analyses, P value used for statistical significance was 0.05 (two tailed).

RESULTS

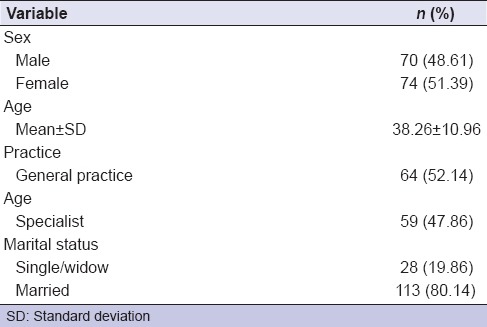

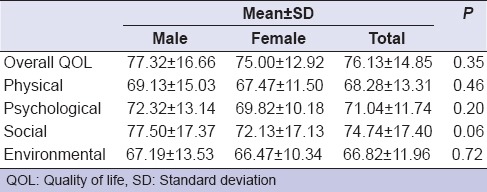

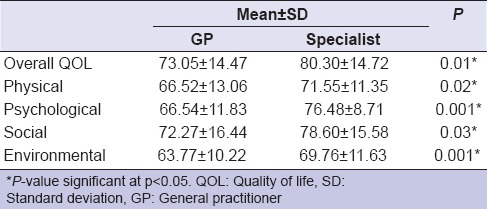

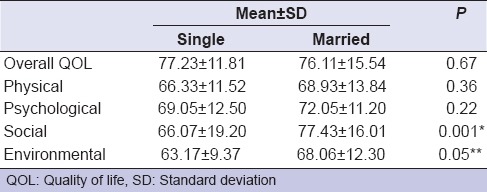

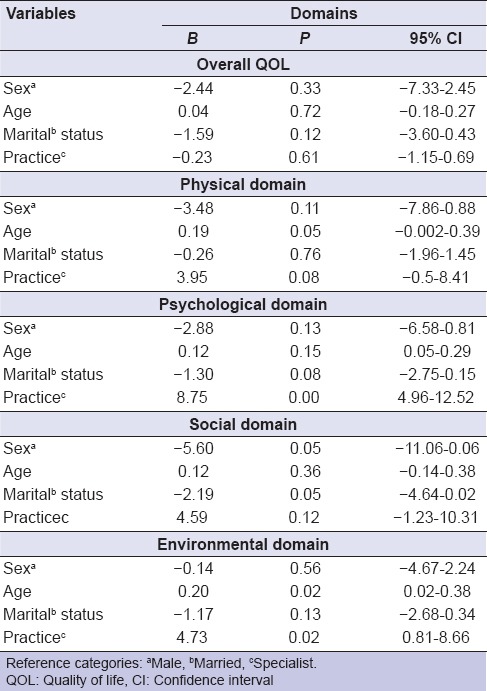

Out of the 290 questionnaires distributed to dentists, 135 questionnaires were answered and returned. The response rate was 46%. Maintaining high response rates is always desirable in a survey. However, a review of literature shows that survey response rates among physicians tend to be lower than the general population owing to their demanding work schedules.[15] Nearly 51% of the study participants were females and the majority were married (80.14%) [Table 1]. No significant differences were observed in the four QOL domains according to sex [Table 2]. On the other hand, significant differences were observed in the QOL domains according to dentists' practice. Specialists had significantly better QOL than GPs on all the four domains of the WHO-BREF questionnaire [Table 3, P < 0.05], with the largest difference observed in the psychological domain (76.48 ± 8.71 vs. 66.54 ± 11.83, P < 0.05). In addition, married dentists appeared to express significantly better QOL compared to single/widowed dentists on the social and environmental domains [Table 4, P < 0.05]. Multivariate regression analysis [Table 5] shows that specialists expressed better QOL in the psychological and environmental domains after adjustment for age, sex, and marital status (B = 8.75, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 4.96–12.52: P =0.00; B = 4.73, 95% CI: 0.81–8.66, P = 0.02).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the study participants

Table 2.

Quality-of-life domains according to sex

Table 3.

Quality-of-life domains according to dentists' practice

Table 4.

Quality-of-life domains according to marital status

Table 5.

Mutilinear regression analysis for the association between each of the quality-of-life domains and gender, age, marital status, and practice

DISCUSSION

There is a link between dentists' job satisfaction and patients' experiences;[16] therefore, assessment of dentists' QOL is important to understand. Arguably, dentists' QOL could affect the delivery of care as well as the communication with patients and consequently, patients' satisfaction with the treatment received. Previous studies that assessed job satisfaction of dentists[3,7,17,18] reported that several factors such as work-related environment, personal life, clinic location, years of practice, and income were positively associated with job satisfaction among dentists. Other factors such as patient relations and years in practice were also found to affect job satisfaction.[19,20]

Stress and job satisfaction have a complex interrelation and stress could be a significant feature of a dentists' job.[21] Working in a dental practice is recognized to be a physically and mentally demanding activity and the possible consequences of chronic occupational stress are professional burnouts.[22] As professional burnout affects all aspects of life including marital problems, emotional disorders, and problems with alcohol and drug abuse, this has a devastating effect on the patients, resulting in medical errors and reduced compliance to medical advice.[23,24,25] Although several studies addressed job satisfaction among dentists, the literature is scarce regarding QOL of dentists in general.

The majority of dentists, in our study, rated their QOL as “very satisfied,” and the highest mean scores were obtained in the social domain. The social domain could be influenced by the marital status, where married dentists had better social life and superior social relationships. Our study revealed that married dentists, when compared to single dentists, seem to have better QOL on the social domain and this relationship persisted after adjustment for gender and age. These results are consistent with the findings of studies by Doshi et al.,[26] Wig et al.,[27] and Barua et al.[28] Married couples in general had increased social, emotional, and financial backing and thus a better secure life. Their combined network of colleagues, professional relations, and associates would be larger and would bring increased opportunities to interact with people in different or similar fields. On the contrary, in a study on dentists of local public health services,[29] the physical domain had the highest scores. The authors explain that there was a contrast of information on the health evaluation and reports of presence of actual disease in the participants. This implies that even though there were health issues, this did not prevent a majority of these professionals from performing their daily activities.

Different age groups showed variations in satisfaction levels. The results of studies done by Luzzi et al.,[17] Nunes Mde and Freire Mdo,[29] and Kaipa et al.[30] showed low job satisfaction levels with age. The authors attribute these findings to greater responsibilities and family commitments, which may explain the negative association between age and job satisfaction. However, consistent with some reports,[7,31,32] the results in our study show that QOL of the dentists improved with age. This could be explained by the fact that experienced dentists have already proven practices, administrative responsibilities and established relationships with colleagues, patients, and staff, and manage their personal time well; consequently they can handle the demands of their career.

Specialists in our study rated their QOL higher when compared to GPs in the environment domain. Possible factors such as financial resources, security, health and social care, opportunities for acquiring new information and skills, and opportunities for recreation/leisure activities could contribute to this. Poor satisfaction in GP dentists may be related to their fear about career goals and the feeling of being unable to improve themselves.[3,33] In a study on dentists' QOL in teaching hospitals, results show that being a specialist dentist positively influenced the QOL as reflected in the psychologic domain.[25] However, in a QOL study among dentists of a local public health service in 2006, there was no difference between dentists with or without a graduate degree in any aspect of the QOL.[28] In the UAE, specialists are assessed in their area of expertise and are licensed by the authorities to secure a job more easily when compared to a GP. They are usually limited to treating specialty cases, have job satisfaction focusing on their specialty, and have the opportunity to collaborate with specialists in their field in various forums and associations. The financial compensations and benefits are also higher for specialists.

A limitation of this study was that only dentists in private practices were included, thereby limiting the generalization of study findings to all dentists in the UAE. Although differences were observed in the QOL between specialists and GPs, a casual association cannot be concluded given the cross-sectional design of this study. Furthermore, the respondent rate could affect the study results as the decision to respond or not to the survey could be related to their perceptions regarding their QOL. The results are based on responded surveys; this low response rate might change the final outcome (bias).

CONCLUSION

Although our findings suggest that specialists have better QOL than GPs, additional research is needed to expose other factors not measured in this study and their impact. Our findings could provide dentists with some important insights into possible factors which affect their QOL and may be considered when choosing their practice settings, as scientific evidence has shown that low job satisfaction is linked with low performance, suboptimal health-care delivery, and clinical outcomes of primary care providers, which can lead to loss of continuity of care.[19,34]

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgment

We would like to thank Ghadeer Aref, Hadeel Abu Hussein, Imran Maher, Mays A. Zaidan, Yasmin Obaidi and Yasmine Tariq who helped in collection of data for the study.

REFERENCES

- 1.Nylenna M, Gulbrandsen P, Førde R, Aasland OG. Unhappy doctors? A longitudinal study of life and job satisfaction among Norwegian doctors 1994-2002. BMC Health Serv Res. 2005;5:44. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-5-44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.WHO Work Plan 2009-2012. WHO Global Network of Collaborating Centers in Occupational Health. Available from: http://www.who.int/occupational_health/cc_compendium.pdf .

- 3.Jeong SH, Chung JK, Choi YH, Sohn W, Song KB. Factors related to job satisfaction among South Korean dentists. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2006;34:460–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.2006.00297.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Puriene A, Aleksejuniene J, Petrauskiene J, Balciuniene I, Janulyte V. Occupational hazards of dental profession to psychological wellbeing. Stomatologija. 2007;9:72–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leggat PA, Kedjarune U, Smith DR. Occupational health problems in modern dentistry: A review. Ind Health. 2007;45:611–21. doi: 10.2486/indhealth.45.611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gorter RC, Albrecht G, Hoogstraten J, Eijkman MA. Work place characteristics, work stress and burnout among Dutch dentists. Eur J Oral Sci. 1998;106:999–1005. doi: 10.1046/j.0909-8836.1998.eos106604.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shugars DA, DiMatteo MR, Hays RD, Cretin S, Johnson JD. Professional satisfaction among California general dentists. J Dent Educ. 1990;54:661–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Logan HL, Muller PJ, Berst MR, Yeaney DW. Contributors to dentists' job satisfaction and quality of life. J Am Coll Dent. 1997;64:39–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Judge TA, Bono JE. Relationship of core self-evaluations traits – Self-esteem, generalized self-efficacy, locus of control, and emotional stability – With job satisfaction and job performance: A meta-analysis. J Appl Psychol. 2001;86:80–92. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.86.1.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alexopoulos EC, Stathi IC, Charizani F. Prevalence of musculoskeletal disorders in dentists. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2004;5:16. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-5-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yasobant S, Rajkumar P. Work-related musculoskeletal disorders among health care professionals: A cross-sectional assessment of risk factors in a tertiary hospital, India. Indian J Occup Environ Med. 2014;18:75–81. doi: 10.4103/0019-5278.146896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.The WHOQOL-BREF Questionnaire. US Version, University of Washington. Seattle: Washington United States of America; 1997. Jun, [Google Scholar]

- 13.The WHOQOL Group. Development of the World Health Organization WHOQOL-BREF quality of life assessment. Psychol Med. 1998;28:551–8. doi: 10.1017/s0033291798006667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ahmad MS, Bhayat A, Zafar MS, Al-Samadani KH. The impact of hyposalivation on Quality of Life (QoL) and oral health in the aging population of Al Madinah Al Munawarrah. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2017;14 doi: 10.3390/ijerph14040445. pii: E445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Flanigan TS, McFarlane E, Cook S. Proceedings of the Survey Research Methods Section. American Statistical Association; 2008. Conducting Survey Research among Physicians and Other Medical Professionals: A Review of Current Literature; pp. 4136–47. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lo Sasso AT, Starkel RL, Warren MN, Guay AH, Vujicic M. Practice settings and dentists' job satisfaction. J Am Dent Assoc. 2015;146:600–9. doi: 10.1016/j.adaj.2015.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Luzzi L, Spencer AJ, Jones K, Teusner D. Job satisfaction of registered dental practitioners. Aust Dent J. 2005;50:179–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1834-7819.2005.tb00358.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wells A, Winter PA. Influence of practice and personal characteristics on dental job satisfaction. J Dent Educ. 1999;63:805–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schwartz RH, Shenoy S. Personality factors related to career satisfaction among general practitioners. J Dent Educ. 1994;58:225–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ali DA. Patient satisfaction in dental healthcare centers. Eur J Dent. 2016;10:309–14. doi: 10.4103/1305-7456.184147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gorter RC, Freeman R. Burnout and engagement in relation with job demands and resources among dental staff in Northern Ireland. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2011;39:87–95. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.2010.00568.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rada RE, Johnson-Leong C. Stress, burnout, anxiety and depression among dentists. J Am Dent Assoc. 2004;135:788–94. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2004.0279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Norlund S, Reuterwall C, Höög J, Lindahl B, Janlert U, Birgander LS, et al. Burnout, working conditions and gender – Results from the northern Sweden MONICA study. BMC Public Health. 2010;10:326. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-10-326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.De Valk M, Oostrom C. Burnout in the medical profession. Occup Health Work. 2007;3:1–4. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gorter RC, Eijkman MA, Hoogstraten J. Burnout and health among Dutch dentists. Eur J Oral Sci. 2000;108:261–7. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0722.2000.108004261.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Doshi D, Jain A, Vinaya K, Kotian S. Quality of life among dentists in teaching hospitals in South Canara, India. Indian J Dent Res. 2011;22:552–5. doi: 10.4103/0970-9290.90297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wig N, Lekshmi R, Pal H, Ahuja V, Mittal CM, Agarwal SK, et al. The impact of HIV/AIDS on the quality of life: A cross sectional study in North India. Indian J Med Sci. 2006;60:3–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Barua A, Mangesh R, Kumar H, Mathew S. A cross-sectional study on quality of life in geriatric population. Indian J Comm Med. 2007;32:146–7. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nunes Mde F, Freire Mdo C. Quality of life among dentists of a local public health service. Rev Saude Publica. 2006;40:1019–26. doi: 10.1590/s0034-89102006000700009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kaipa S, Pydi SK, Krishna Kumar RV, Srinivasulu G, Darsi VR, Sode M, et al. Career satisfaction among dental practitioners in Srikakulam, India. J Int Soc Prev Community Dent. 2015;5:40–6. doi: 10.4103/2231-0762.151976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Puriene A, Petrauskiene J, Janulyte V, Balciuniene I. Factors related to job satisfaction among Lithuanian dentists. Stomatologija. 2007;9:109–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gilmour J, Stewardson DA, Shugars DA, Burke FJ. An assessment of career satisfaction among a group of general dental practitioners in Staffordshire. Br Dent J. 2005;198:701–4. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4812387. discussion 693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yildiz S, Dogan B. Self reported dental health attitudes and behaviour of dental students in Turkey. Eur J Dent. 2011;5:253–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Judge TA, Thoresen CJ, Bono JE, Patton GK. The job satisfaction-job performance relationship: A qualitative and quantitative review. Psychol Bull. 2001;127:376–407. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.127.3.376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]