Abstract

Background

Two methods are presented for obtaining hysterectomy prevalence corrected estimates of invasive cancer incidence rates and probabilities of the corpus uterine.

Methods

The first method involves cross-sectional hysterectomy data from the Utah Hospital Discharge Data Base and mortality data applied to life-table methods. The second involves hysterectomy prevalence estimates obtained directly from the Utah Behavior Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) survey.

Results

Hysterectomy prevalence estimates based on the first method are lower than those obtained from the second method through age 74, but higher in the remaining ages. Correction for hysterectomy prevalence is greatest among women ages 75–79. In this age group, the uncorrected rate is 125 (per 100,000) and the corrected rate based on the life-table method is 223 using 1995–97 data, 243 using 1992–94 data, and 228 from the survey method. The uncorrected lifetime probability of developing corpus uterine cancer is 2.6%; the corrected probability from the life-table method using 1995–97 data is 4.2%, using 1992–94 data is 4.5%; and based on prevalence data from the survey method is 4.6%.

Conclusions

Both methods provide reasonable hysterectomy prevalence estimates for correcting corpus uterine cancer rates and probabilities. Because of declining trends in hysterectomy in recent decades, corrected estimates from the life-table method are less pronounced than those based on the survey method. These methods may be useful for obtaining corrected uterine cancer rates and probabilities in areas of the world that do not have sufficient years of hysterectomy data to directly compute prevalence.

Introduction

Conventional cancer incidence rates contain new cases of the disease for a given year in the numerator and the mid-year population in the denominator [1]. However, this rate is potentially problematic for those cancers in which the denominator includes cases not at-risk of developing the disease [2]. For example, a large portion of the female population will undergo a hysterectomy in their lifetime [2-4], removing them from being at risk of developing corpus uterine cancer. In addition, a woman with cancer of the corpus uterine is very unlikely to be diagnosed with the disease a second time [2]. Hence, these women should be removed from the at-risk population in the rate calculation.

In the mid 1970s, Lyon and Gardner presented a method for obtaining hysterectomy prevalence and applied it to uterine cancers in order to produce corrected incidence and mortality rates [5]. The approach used the prevalence of hysterectomy, as determined by the United States Health Examination Survey of 1960–1962 [6], and a cohort model population applied to the 1960 United States female population. This population was corrected over time by hysterectomy rates obtained from the National Hospital Discharge Survey, a survey providing annual probability samples of hospital discharges from nonfederal, short-stay hospitals [7]. A more recent study provided corrected uterine cancer rates for the United States by applying the method proposed by Lyon and Gardner and using hysterectomy rates from the National Hospital Discharge Survey through 1992 [2].

Two other methods may be used to obtain hysterectomy prevalence estimates that have an advantage in that they do not require several years of follow-up data to obtain hysterectomy prevalence estimates. The first involves calculating hysterectomy prevalence estimates by applying cross-sectional hysterectomy incidence and all-cause mortality data to single- and double-decrement life tables [8]. However, this approach may be limited by trends in the data. A second approach obtains prevalence estimates directly from responses to cross-sectional survey data. An advantage of this method is that it does not require complicated modeling, but it may be limited by potential biases that affect self-reported survey data.

The purpose of this paper is to describe these two methods for correcting corpus uterine cancer incidence rates and probabilities. The methods yield estimates of the proportion of the population at risk for developing the disease and correct the incidence rates and probabilities accordingly. Although the focus is on corpus uterine cancer, the same methods may be applied to other cancers of the female genital system, such as of the cervix uteri or ovaries.

Materials and Methods

Method 1. Life-table method of estimating hysterectomy prevalence

A single-decrement life table was used to calculate the proportion (p1x) of a hypothetical cohort of 10 million newborns alive at the beginning of age interval x when exposed to the cross-sectional hazard of death from all causes. From a multiple-decrement life table, the proportion (p2x) of a hypothetical cohort of newborns alive and at risk of the disease at the beginning of age interval x is calculated based on their chance of having undergone a hysterectomy, having been diagnosed with the disease, or dying of any cause. Women having undergone a hysterectomy or previously diagnosed with corpus cancer without having had a hysterectomy are assumed to reflect those not at risk of developing the disease. The prevalence of having undergone a hysterectomy or having been previously diagnosed with corpus uterine cancer (minus those having had a hysterectomy is calculated as Px = 1-(p2x/p1x).

Estimates derived from the life tables represent the prevalence that would be observed if a cohort of individuals were exposed to the current hysterectomy, corpus uterine (minus those having had a hysterectomy), and all-cause mortality rates over their entire lifetime.

Method 2. Cross-sectional survey method for estimating hysterectomy prevalence

The status of an individual with respect to the presence or absence of a disease or health-related event may be obtained through assessment at a given point in time. There are national and international surveys that track the disease and health status of people in the population. For example, the Behavior Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) collects information about women's health issues, such as pregnancy and hysterectomy. A question that asks whether a woman has ever had a hysterectomy, along with solicitation of the woman's current age, indicates the prevalent proportion of women who have had a hysterectomy by a certain age.

Corrected denominators in the cancer rate calculation

In order to correct the denominator in the rate calculation of corpus uterine cancer, we need to alter the population so that it reflects women at risk of developing the disease. We assume that a woman is at risk of developing corpus uterine cancer if she has not already been diagnosed with the disease or has had her uterus removed because of a hysterectomy. The majority of women who are diagnosed with corpus uterine cancer are treated with a hysterectomy. The percentage of corpus uterine cancer cases that underwent a hysterectomy between 1995–97 was 93% overall, 85% for ages 0–39, 98% for ages 40–59, and 91% for ages 60 and older [9]. Thus, the prevalence (Px) derived using the life-table method involves the age-specific number of hysterectomies plus women diagnosed with corpus uterine cancer who did not undergo a hysterectomy (i.e., not at risk). In the survey method, the age-specific rate of women not at risk of corpus uterine cancer divided by the age-specific rate of women having undergone a hysterectomy provided an index which was multiplied by the age-specific hysterectomy prevalence obtained from the BRFSS to get an estimate of prevalent proportion of women not at risk of corpus uterine cancers.

Corrected incidence rates of cancers of the corpus uterine

Conventional cancer incidence rates are derived as Rx= Cx/Lx, where Cx is the age-specific number of cancer cases and Lx is the mid-year population from cross-sectional census dat. Corrected rates are derived as:

![]()

for x = 0-4, 5-9, . . ., 80-84, 85+.

Lifetime and age-conditional probability estimates

Lifetime and age-conditional probability (risk) estimates of being diagnosed with cancer are derived using life-table methods. Conventional lifetime and age-conditional probability estimates of being diagnosed with cancer are corrected for the prevalence of the cancer. This involves multiplying the cancer incidence rate used in the computation of the probability estimates by p1x/p2x = 1/(1-Px). The two methods for obtaining Px are described above. A complete description of the method for deriving lifetime and age-conditional probability estimates of being diagnosed with cancer is given elsewhere [8]. Probability estimates of developing cancer are reported across the age span and interpreted as the probability that the average child born today will be diagnosed with the disease by age x. This statistic assumes that the current rates upon which the probability estimates are based will remain constant over the child's lifetime. Given that current rates are unlikely to remain constant over an extended period of time, and that persons are more likely interested in their chance of developing the cancer from their current ages onward, short-term, age-conditional probability estimates are perhaps more relevant [10]. Both types of probability estimates are reported in this paper.

Diagnostic and procedure codes

The Utah Cancer Registry identifies cancer using the International Classification of Disease, Second Edition (ICD-02) [11]. Invasive cancers of the corpus uteri and other uterus not otherwise specified (hereafter called corpus uteri) are identified as C540-C549 and C559. Hysterectomy is defined as International Classification of Disease, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) procedure codes 68.3 to 68.8, where 68.3 to 68.4 reflect abdominal hysterectomy, 68.5 reflects vaginal hysterectomy, and 68.6 to 68.8 reflect radical hysterectomy [12].

Data sources

Data from five different sources were used in the analysis: hysterectomy cases obtained from the Hospital Discharge Data Base (HDDB) in Utah, hysterectomy prevalence obtained from the BRFSS, invasive corpus uterine cancer cases from the Utah Cancer Registry, population estimates from the United States Bureau of the Census, and mortality data from the Utah State Health Department. Population estimates of the female residents in Utah were combined with case data to compute hysterectomy incidence rates, prevalence proportions, and invasive cancer incidence rates and probabilities. Three years of data were considered in order to provide more stable estimates. The influence of race was not considered because of the high percentage of whites in Utah (i.e., 95% White, 2% Indian, 2% Asian, 1% Black) [13].

Fifty-five Utah hospitals submit data to the Utah Health Data Committee on an ongoing basis. These hospitals include nine psychiatric facilities, seven specialty hospitals, and the Veterans Administration Medical Center. Shriners Hospital, a charity hospital, is exempt from reporting requirements. These hospitals report discharge data (i.e., the consolidation of complete billing, medical, and personal information describing a patient, the services received, and the charges billed) for each patient served on an inpatient basis.

Cancer data were obtained from the Utah Cancer Registry, which is one of the oldest in the country, originating in 1966. Since 1973, the Utah Cancer Registry has participated in the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program of the National Cancer Institute [1]. The registries in the SEER Program meet high-quality standards and are the nation's source of cancer incidence and survival data. Since 1983, the cancer registries in the SEER Program have also collected first course of cancer-directed therapy. The Utah Cancer Registry ensures complete incidence and treatment information by abstracting information from hospital records, clinical and nursing home records, private pathology laboratories and radiotherapy units, and death certificates.

The BRFSS is a state-based surveillance system active in all 50 states. Since the early 1980s, the Center for Disease Control and Prevention has collaborated with states to develop questions that would reveal adults' knowledge, attitudes, and practices related to health issues. Since 1984 Utah has been involved in collecting data for the BRFSS.

Age-specific corpus uterine rates are fit using second- or third-order polynomial models.

Results

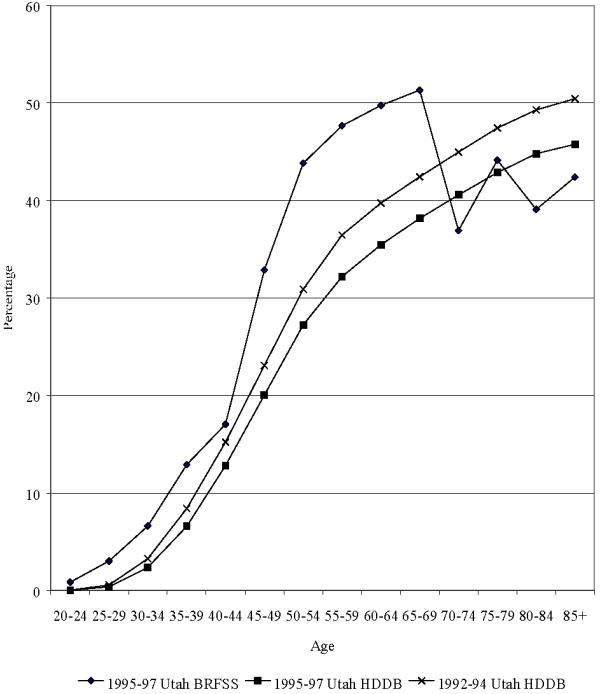

Numbers and crude rates of hysterectomy per 10,000 in Utah are shown for 1992–94 and 1995–97 (Table 1). The rates increase early in life, peak, and then decrease over the older ages. The rates were significantly higher in 1992–94, compared to 1995–97, in the age groups 25–34 and 35–44. Estimates of hysterectomy prevalence based on the life-table method and the survey method are presented in Figure 1. Higher prevalence estimates based on the life-table method with 1992–94 data versus 1995–97 data reflect lower hysterectomy rates in the later time period for most ages. Prevalence estimates based on the BRFSS 1995–97 are highest, particularly for women aged 45 through 69.

Table 1.

Numbers and crude rates of hysterectomy per 100,000 women in Utah during 1992–94 and 1995–97

| 1992–94 | 1995–97 | |||

| Age Group | Number | Rate | Number | Rate |

| 15–24 | 287 | 57 | 212 | 36a |

| 25–34 | 3,568 | 838 | 2,910 | 664ab |

| 35–44 | 6,138 | 1597 | 6,232 | 1494ab |

| 45–54 | 3,679 | 1455 | 3,990 | 1328a |

| 55–64 | 1,145 | 636 | 1,224 | 624 |

| 65–74 | 834 | 547 | 807 | 512 |

| 75+ | 373 | 288 | 411 | 287 |

| 15+ | 16,024 | 788 | 15,786 | 705a |

Data source: Utah Hospital Discharge Data, Public Dataset. aSignificant change in rates between 1992–94 and 1995–97, p < 0.05.

Figure 1.

Age-specific hysterectomy point prevalence proportions in Utah according to calendar year and source

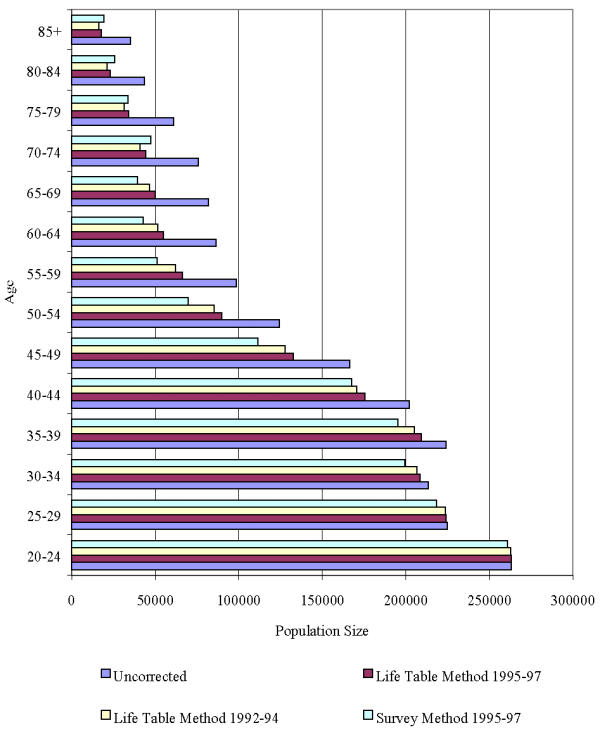

During 1995–97, there were 549 cases of invasive cancer of the corpus uteri in Utah. The age-adjusted rate was 20 per 100,000. This conventionally derived rate is based on the denominator of the rate calculation including women who are not at risk of being diagnosed with invasive cancer of the corpus uterine. Figure 2 presents corrected and uncorrected population denominators with the corrections based on the two methods. Applying the corrected populations, the age-adjusted rates using the life - table method became 32 with 1995-97 data, 34 with 1992-94 data, and using the survey method was 37.

Figure 2.

Corrected and uncorrected population denominators

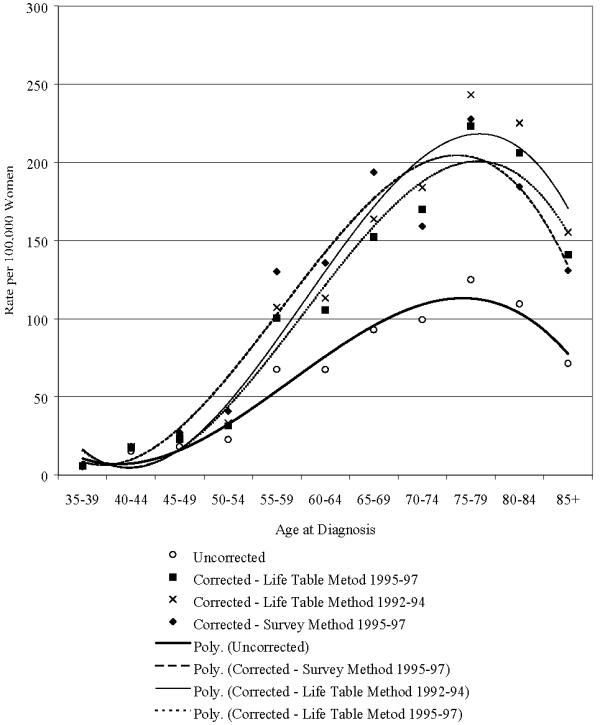

Figure 3 presents corrected and uncorrected invasive cancer incidence rates of the corpus uteri in Utah. The correction for hysterectomy prevalence was greatest among women ages 75–79. In this age group, the uncorrected rate was 125 per 100,000 and the corrected rate using the life-table method was 223 based on 1995–97 data, 243 based on 1992–94 data, and the corrected rate using the survey method was 228.

Figure 3.

Corrected and uncorrected invasive cancer incidence of the corpus uteri and uterus not otherwise specified in Utah

The lifetime probability of developing corpus uterine cancer was 2.6% (uncorrected); and corrected, based on the life-table method, was 4.2% using 1995–97 data, 4.5% using 1992–94 data; and according to the survey method was 4.6%. Corresponding percentages women free of the disease at age 50 are slightly lower, 2.5%, 4.1%, 4.4%, and for 4.5%.

Table 2 shows the corrected and uncorrected number per 100,000 invasive cancers of the corpus uteri expected in Utah over the next 10 years among women aged x. Ten-year probability estimates are largely influenced by the age in which they are conditioned. The 10-year probability of being diagnosed with cancer of the corpus uterine is greatest for women aged 65. The corrections increase these probabilities considerably, most noticeably for those corrected using the survey method.

Table 2.

Corrected and uncorrected number per 100,000 of invasive cancers

| Age x | |||||

| 25 | 35 | 45 | 55 | 65 | |

| Uncorrected | |||||

| Number | 208 | 464 | 680 | 774 | 885 |

| Life Table Method 1995–97 | |||||

| Number | 276 | 677 | 1,037 | 1,243 | 1,480 |

| % Increase a | 32.7% | 45.9% | 52.5% | 60.6% | 67.2% |

| Life Table Method 1992–94 | |||||

| Number | 289 | 721 | 1,109 | 1,334 | 1,595 |

| % Increase a | 38.9% | 55.4% | 63.1% | 72.4% | 80.2% |

| Survey Method 1995–97 | |||||

| Number | 345 | 876 | 1,336 | 1,586 | 1,633 |

| % Increase a | 65.9% | 88.8% | 96.5% | 104.9% | 84.5% |

aPercentage increase between the corrected and uncorrected number of invasive corpus uteri and uterus not otherwise specified.

Discussion

This paper presents two methods for obtaining corrected corpus uterine cancer incidence rates and probabilities. In the life-table method, hysterectomy or corpus uterine cancer prevalence estimates were derived from cross-sectional hysterectomy, corpus uterine, and all-cause mortality data applied to life tables. In the survey method, hysterectomy prevalence estimates were obtained directly from BRFSS data. The purpose of the correction was to adjust the population values used in the calculations in order to reflect the at-risk population for developing corpus uterine cancer.

Both methods have the advantage that several years of follow-up data are not required to determine the at-risk population. Hence, for areas of the world that do not have sufficient years of hysterectomy or cancer data to directly compute prevalence, corrected rates and probabilities can still be obtained. However, the life-table method is limited by trends in the data. Because the hysterectomy rates were lower in 1995–97 than in previous years, the prevalence estimates based on these years underestimated the prevalence of this procedure. Use of the higher incidence rates in 1992–94 produced higher hysterectomy prevalence estimates across the age span. However, prevalence based on these rates may also have been underestimated, at least through ages 69, as suggested by the hysterectomy prevalence estimates from the survey method.

According to a self-reported national survey, hysterectomies have remained stable between 1965–95 [14]. However, based on the National Hospital Discharge Survey, there is evidence that hysterectomy rates decreased slightly from the mid 1970s through the 1980s and then may have leveled off through 1993 [4,15,16]. Our results show that hysterectomy in Utah significantly decreased between 1992–94 and 1995–97 in the age groups 25–34 and 35–44, where hysterectomy is most common. This suggests that hysterectomy prevalence based on the cross-sectional method, at least for ages less than 55 based on 1995-97 data, underestimates hysterectomy prevalence. Use of the survey method to obtain prevalence has the advantage that it does not require complicated modeling and is not influenced by trends, but it may or may not represent the Utah population, given potential biases that may influence self-reported responses. Yet a high level of correspondence has been previously shown to exist between self-reports and hospital records of hysterectomy [17].

In an earlier report by Merrill and Feuer [2], based on 1990–92 national data, the hysterectomy prevalence correction based on an historical, rather than a cross-sectional, approach increased the age-adjusted rates of corpus uterine rates from 22.2 to 33.0. Although we cannot compare our results directly because of difference in time periods studied, the unique racial makeup in Utah, and because we also incorporated the prevalence of corpus uterine cancer cases not treated with a hysterectomy, the magnitude of the correction is similar to those reported in this prior study.

As anticipated, the hysterectomy prevalence corrections had large influences on the rates and probabilities. The percentage increase was smallest earlier in life and increased consistently with age. This is because the number of women alive that have undergone a hysterectomy increases over the age span, as evident in the corrected versus the uncorrected rates and probabilities. Yet, although the percentage change increases with age, the greatest absolute change tends to be where the cancer rates are largest.

It should be emphasized that correcting the rates and probabilities had a large impact because of the high prevalence of hysterectomy. The additional influence of prevalent cases of corpus uterine cancer cases who had not undergone a hysterectomy was relatively very small. Several studies have explored the benefits, risks, and costs of hysterectomy [18-28]. Despite the potential risks and costs associated with this medical procedure, over 35% of women in the United States received a hysterectomy by age 50 [2]. Hysterectomies are primarily performed for nonmalignant conditions [3,4], with the expectation that the benefits of the surgery outweigh the risks.

Given the high percentage of whites in Utah, the study results primarily reflect this race. Hence, comparison of the results to other geographic locations should be restricted to primarily white populations. Yet the results provide an important baseline for future comparisons.

In addition to the limitations stated above, because it is impractical to expect cross-sectional rates upon which lifetime and age-conditional cancer probabilities are based to remain constant in the long run, lifetime probabilities of cancer are less reliable than shorter term, age-conditional probability estimates. They are also less relevant to a woman already aged to mid-life. However, lifetime probability estimates of cancer may provide a guide to individuals and health policy officials as to the burden of these select cancers.

As already well established, an accurate representation of the expected risk of corpus uterine cancer requires that the population in the incidence-rate calculation be corrected to reflect the at-risk population. Similarly, an accurate measure of the burden of this cancer, in terms of lifetime and age-conditional probabilities of developing the disease, also requires a population correction to reflect those women at risk. The two methods developed in this study reflect unique strengths and weaknesses. Yet despite their potential weaknesses and in the absence of long-term hysterectomy and cancer data, they will provide more reasonable estimates of the rates and probabilities of corpus uterine cancer.

Competing Interests

None declared

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:

Contributor Information

Ray M Merrill, Email: ray_merrill@byu.edu.

Joseph L Lyon, Email: jlyon@dfpm.utah.edu.

Charles Wiggins, Email: chuck.wiggins@hsc.utah.edu.

References

- Ries LAG, Kosary CL, Hankey BF, Miller BA, Edwards BK, eds SEER cancer statistics review, 1973–1996 Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute, 1999.

- Merrill RM, Feuer EJ. Risk-adjusted cancer incidence rates (United States). Cancer Causes Control. 1996;7:544–552. doi: 10.1007/BF00051888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilcox LS, Koonin LM, Pokras R, Strauss LT, Xia Z. Hysterectomy in the United States, 1988–1990. Obstet Gynecol. 1994;83:549–555. doi: 10.1097/00006250-199404000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lepine LA, Hillis SD, Marchbanks PA, Koonin LM, Morrow B, Kieke BA, et al. Hysterectomy Surveillance – United States, 1980–93. In CDC Surveillance Summaries, Aug 8 1997 MMWR. 1997;46(SS-4):1–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyon JL, Gardner JW. The rising frequency of hysterectomy: its effect on uterine cancer rates. Am J Epidemiol. 1977;105:439–443. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a112402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacMahon B, Worcester J. Age at menopause. Washington, DC: US Public Health Service, USPHS Pub No 1000, Series 11, No 19. 1966.

- Grave EJ. National hospital discharge survey: annual summary, 1990. Hyattsville, MD (USA): National Center for Health Statistics, 1992; DHHS Pub No (PHS) 92-1773, (Vital and Health Statistics, Series 13, No 112) [PubMed]

- Wun L-M, Merrill RM, Feuer EJ. Estimating lifetime and age-conditional probabilities of developing cancer. Lifetime Data Analysis. 1998;4:169–186. doi: 10.1023/A:1009685507602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SEER*Stat 3.0. SEER Cancer Incidence Public-Use Database, 1973–1997. August 1999 Submission. Bethesda, MD (USA): US Department of Health and Human Services National Institutes of Health.

- Merrill RM, Kessler LG, Udler JM, Rasband GC, Feuer EJ. Comparison of risk estimates for selected diseases and causes of death. Prev Med. 1999;28:179–193. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1998.0399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- International classification of diseases for oncology. 2nd ed Geneva, World Health Organization, 1990.

- International classification of diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification. 4th ed DHHS No (PHS) 91-US Dept HHS, PHS, HCFA, 1991.

- US Bureau of the Census. NCHS vs census race distribution of population age 0 and mean absolute percent error (using NCHS race of mother) 2000. http://www.census.gov:80/population/documentation/twps0017/table05.txt

- Brett KM, Marsh JVR, Madans JH. Epidemiology of hysterectomy in the United States: demographic and reproductive factors in a nationally representative sample. J Womens Health. 1997;6:309–316. doi: 10.1089/jwh.1997.6.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sattin RW, Rubin GL. Hysterectomy among women of reproductive age, United States, Update for 1979–1980. MMWR. 1983;32(3SS):1ss–7ss. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irwin KL, Peterson HB, Hughes JM, Gill SW. Hysterectomy among women of reproductive age, United States, update for 1981–1982. MMWR. 1986;35(1SS):1ss–6ss. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brett KM, Madans JH. Hysterectomy use: the correspondence between self-reports and hospital records. Am J Public Health. 1994;84:1653–5. doi: 10.2105/ajph.84.10.1653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandberg SI, Barnes BA, Weinstein MC, Braun P. Elective hysterectomy: benefits, risks, and costs. Med Care. 1985;23:1067–1085. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones ED, Shackelford DP, Brame RG. Supracervical hysterectomy: back to the future? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1999;180:513–515. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(99)70245-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parazzini F, Negri E, Vecchia CL, Luchini L, Mezzopane R. Hysterectomy, oophorectomy, and subsequent ovarian cancer risk. Obstet Gynecol. 1993;81:363–366. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grover CM, Kupperman M, Kahn JG, Washington AE. Concurrent hysterectomy at bilateral salpingo oophorectomy: benefits, risks, and costs. Obstet Gynecol. 1996;88:907–913. doi: 10.1016/S0029-7844(96)00314-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Speroff T, Dawson NV, Speroff L, Haber RJ. A risk-benefit analysis of elective bilateral oophorectomy: effect of changes in compliance with estrogen therapy on outcome. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1991;164:165–174. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(91)90649-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kritz-Silverstein D, Barrett-Connor E, Wingard DL. Hysterectomy, oophorectomy, and heart disease risk factors in older women. Am J Pubic Health. 1997;87:676–680. doi: 10.2105/ajph.87.4.676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luoto R, Auvinen A, Pukkala E, Hakama M. Hysterectomy and subsequent risk of cancer. Int J Epidemiol. 1997;26:476–483. doi: 10.1093/ije/26.3.476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green A, Purdie D, Bain C, Siskind V, Russell P, Quinn M, Ward B. Tubal sterilisation, hysterectomy, and decreased risk of ovarian cancer. Survey of Women's Health Study Group. Int J Cancer. 1997;71:948–51. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0215(19970611)71:6<948::AID-IJC6>3.3.CO;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yaegashi N, Sato S, Yajima A. Incidence of ovarian cancer in women with prior hysterectomy in Japan. Gynecol Oncol. 1998;68:244–246. doi: 10.1006/gyno.1998.4946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson KJ, Miller BA, Fowler FJ. The Maine Women's Health Study I: outcomes of hysterectomy. Obstet Gynecol. 1994;83:556–565. doi: 10.1097/00006250-199404000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson KJ, Miller BA, Fowler FJ. The Maine Women's Health Study II: outcomes of nonsurgical management of leiomyomas, abnormal bleeding, and chronic pelvic pain. Obstet Gynecol. 1994;83:566–572. doi: 10.1097/00006250-199404000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]