Abstract

Background

The format or frame in which the results of randomized trials are presented has been shown to influence health professional's self-reported practice. We sought to investigate the effect of framing cardiovascular risk as two different formats in a randomized trial.

Methods

We recruited 457 patients aged between 60 and 79 years with high blood pressure from 20 family practices in Avon, UK. Patients were randomized to cardiovascular risk presented either as 1) an absolute risk level (AR) or as 2) the number needed to treat to prevent an adverse event (NNT). The main outcome measures were: 1) percentage of patients in each group with a five-year cardiovascular risk ≥ 10%, 2) systolic and diastolic blood pressure, 3) intensity of prescribing of cardiovascular medication.

Results

Presenting cardiovascular risk as either an AR or NNT had no impact reducing cardiovascular risk at 12 month follow up, adjusted odds ratio 1.53 (95%CI 0.76 to 3.08). There was no difference between the two groups in systolic (adjusted difference 0.97 mmHg, 95%CI -2.34 mmHg to 4.29 mmHg) or diastolic (adjusted difference 0.70 mmHg, 95%CI -1.05 mmHg to 2.45 mmHg) blood pressure. Intensity of prescribing of blood pressure lowering drugs was not significantly different between the two groups at six months follow up.

Conclusions

Presenting cardiovascular risk in clinical practice guidelines as either an AR or NNT had a similar influence on patient outcome and prescribing intensity. There is no difference in patient outcomes when these alternative formats of risk are used in clinical practice guidelines.

Background

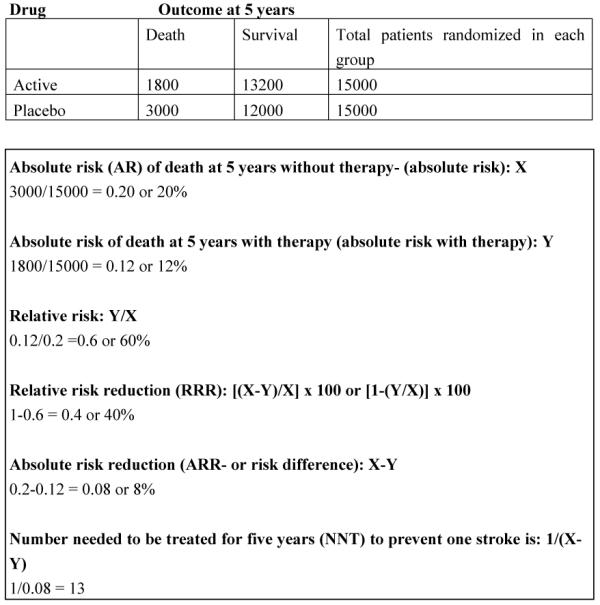

The results of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and clinical practice guidelines are based on data that estimate, in numeric terms, the benefits and risks of treatment [1]. Data can be presented in a number of different formats: as an absolute risk level (AR), an absolute risk reduction (ARR), a relative risk reduction (RRR) or as the number of patients who need to be treated in order that an adverse event is prevented (NNT) [2-4]. (see Figure 1 for an example of how different formats of risk can be calculated)

Figure 1.

Example of how data from randomized trials can be presented as different formats of risk in the treatment of hypertension. Adapted from reference [3].

Studies of self reported practice demonstrate that interpretation by physicians of numeric data may vary depending on the format or the "frame" in which they are presented [1]. In clinical scenarios, results expressed as a relative risk reduction are viewed more positively by health professionals than when they are expressed as absolute differences [1]. However, some studies suggest framing effects may occur between different absolute risk formats; for example primary care physicians are more likely to prescribe anti-hypertensive drugs when results are presented as an ARR than when the same results are presented as an NNT [5]. Such observations are of importance when attempting to ensure that clinical practice is based on highest quality evidence. If physicians are influenced by the "framing" of data presented in clinical practice guidelines or in pharmaceutical promotional material [6], their clinical practice may be systematically biased [1].

Case scenarios of intended clinical practice may not predict actual clinical behaviour [7]. As the existing literature is confined to examination of physicians' opinion or their intended clinical practice, the effect of "framing" on actual clinical practice has not yet been estimated [1]. We aimed to investigate in a randomized controlled trial the effect of "framing" cardiovascular risk when two different but equivalent formats were used: as an absolute risk level (AR) versus number needed to treat (NNT).

Methods

All patients aged 60–80 years with a diagnosis of hypertension and a record of having been prescribed anti-hypertensive medication in the previous year were eligible. Thirty eligible patients were randomly sampled from each practice list using either the computer system's built-in sampling facility (EMIS practices) or a random sampling programme on a personal computer (AAH Meditel practices). Patients were recruited to a study investigating the use of New Zealand practice guidelines for the management of high blood pressure. These practice guidelines specifically quantify the absolute risk of a cardiovascular event (newly diagnosed angina, myocardial infarction, coronary heart disease, stroke or transient ischaemic attack) over a five year period and are based on a Framingham risk equation [8]. The guidelines are formatted in such a way that when an individual's age, sex, smoking status, presence or absence of diabetes, total:HDL cholesterol ratio and blood pressure level are elicited their absolute risk of a cardiovascular event can be read directly from a coloured chart (see: http://cebm.jr2.ox.ac.uk/docs/prognosis.html). This method of risk assessment has been proposed as a rational way on which to base treatment recommendations for patients with high blood pressure [9].

Study design

Twenty seven Family practices were randomly allocated to receive the practice guidelines in either computerised format plus a coloured chart, the chart guidelines only, or usual care (no guidelines). The results of this randomized study have been published separately [10]. In a factorial design, the twenty family practices receiving the practice guidelines in the chart and computerised format were further randomly allocated to have risk presented during the consultation as AR or NNT (the seven "usual care" practices did not receive charts, thus were unable to participate in this part of the randomized trial). The risk tables classify patients into one of six absolute risk categories (<2.5%, 2.5 to 4.9, 5.0 to 9.9, 10.0 to 14.9, 15 to 19.9, >20% over five years). The equivalent NNTs for these absolute risks were presented assuming that blood pressure lowering led to a relative risk reduction of one third. Patients had their blood pressure measured and risk assessed at baseline, six and 12 months follow-up. Local research ethics committee approval was obtained to undertake the study.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was the proportion of patients in each group with cardiovascular risk ≥ 10% over five-years at 12 months follow up. Secondary outcomes were systolic and diastolic blood pressure at 12 months; and intensity of changes in prescribing of blood pressure lowering medication at six months follow up. Blinding the health professionals to intervention group was not possible given the nature of the study. No attempt was made to blind the data analysts (TP, AM & TF) to the study group.

Analysis

All data analyses were carried out using Stata statistical software. Multivariable analyses were performed examining the impact of alternative framing formats (AR or NNT) on outcome, adjusting for intervention group from the other factorial element of the trial (chart plus computer or chart alone), outcome variable at baseline and type of computer system used in the family health centre (one of two different computer systems). Since randomisation was by practice, we also corrected for clustering effects using procedures in Stata to derive robust estimates of standard error. As observational studies have reported on the intention of prescribing in physicians in the context of different framing of risk [1], we measured the intensity of prescribing of blood pressure lowering drugs at baseline and six months follow up. Prescribing intensity was categorised into three groups: 0 or 1; 2; 3 or more different classes of blood pressure lowering drugs. Distribution of prescribing intensity was compared by means of Χ2 test and multinominal logistic regression models that allowed for the distributions of prescribing intensity at baseline.

Sample size calculation

With 93 patients in each arm, a difference of 20 percentage points in the proportion of patients at cardiovascular risk of ≥ 10% could be detected with 80% power and a two sided 5% significance level [10]. This sample size was inflated by a factor of 2.05 based on an intrapractice correlation coefficient of 0.0551 to allow for randomisation by practice [11,12]. This resulted in a sample size requirement of 190 patients for each arm of the randomized trial.

Results

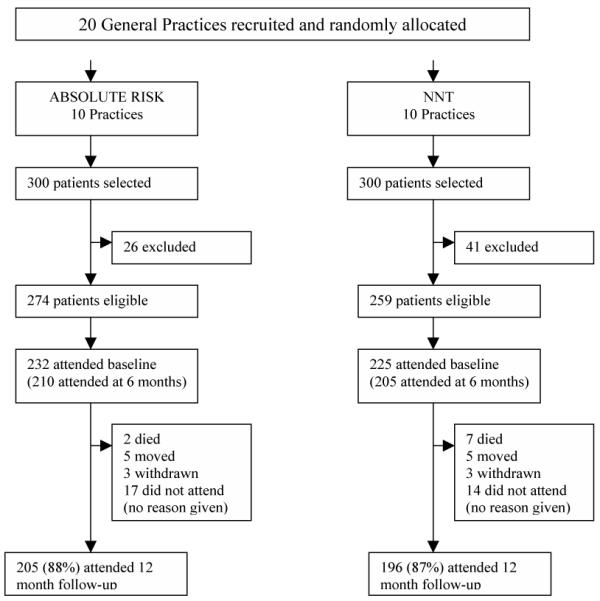

Baseline data were collected from 457 patients and 12-month follow-up data from 401 (88%) patients (Figure 2). As would be expected in an elderly population, over 80% of patients in both comparison groups had a five year cardiovascular risk of 10% or more. Other baseline characteristics are presented in Table 1. Adjusting for the clustering effect of using practice as the unit of randomisation did not affect the results so the unadjusted analyses are reported. Cardiovascular risk increased in both groups during the 12 months of follow up (Table 2). After adjustment for baseline differences, practice computer system and method of presentation (computer or risk chart) there were no statistically significant differences between the AR and NNT groups in terms of primary and secondary outcome variables at 12 months (Table 3).

Figure 2.

Trial profile

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of trial participants

| Absolute Risk (n = 232) | NNT(n = 225) | |

|---|---|---|

| Mean age (SD) in years | 70.4 (5.5) | 70.4 (5.5) |

| Female | 123 (53%) | 130 (58%) |

| Five year cardiovascular risk ≥ 10% | 194 (83.6%) | 193 (85.8%) |

| Mean absolute 5-yr risk in % (SD) | 17.9 (8.2) | 18.4 (8.6) |

| Mean SBP in mmHg (SD) | 152 (19) | 157 (19) |

| Mean DBP in mmHg (SD) | 85 (10) | 86 (9) |

| Mean BMI (SD) | 27.4 (4.5) | 27.0 (4.3) |

| Mean total cholesterol mmol/l (SD) | 6.1 (1.0) (n = 137) | 6.0 (1.0) (n = 143) |

| Mean HDL cholesterol mmol/l (SD) | 1.3 (0.3) (n = 12) | 1.2 (0.3) (n = 16) |

| Current smoker | 34 (14.7%) | 29 (12.9%) |

| Diabetes | 26 (11.2%) | 23 (10.2%) |

| Left Ventricular Hypertrophy | 5 (2.2%) | 9 (4.0%) |

| Atrial fibrillation | 12 (5.2%) | 15 (6.7%) |

| Angina | 21 (9.1%) | 29 (12.9%) |

| Transient Ischaemic Attack | 10 (4.3%) | 10 (4.4%) |

| Angioplasty | 1 (0.4%) | 4 (1.8) |

| Peripheral Vascular Disease | 9 (3.9%) | 13 (5.8%) |

| Coronary Artery Bypass Graft | 1 (0.4%) | 3 (1.3%) |

| Previous Myocardial Infarction | 20 (8.6%) | 13 (5.8%) |

| Previous Stroke | 9 (3.9%) | 6 (2.7%) |

| Family history of Ischaemic Heart Disease | 34 (14.7%) | 48 (21.3%) |

| Family history of stroke | 29 (12.5%) | 38 (16.9%) |

| Family history of hypercholesterolaemia | 8 (3.4%) | 1 (0.4%) |

Table 2.

Unadjusted risk of a cardiovascular event (5 year), mean systolic and diastolic blood pressure at 12-month follow up in the two comparison groups (AR vs NNT)

| Risk presented as | Risk presented as | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome | Absolute Risk | Number Needed to Treat | ||

| (AR) | (NNT) | |||

| (n = 205) | (n = 196) | |||

| Cardiovascular risk n (%) | Baseline | 12 months | Baseline | 12 months |

| 0% to 9.9% | 40 (20%) | 26 (13%) | 36 (18%) | 29(15%) |

| 10% to 19.9% | 104 (51%) | 108 (53%) | 104 (53%) | 109 (56%) |

| ≥ 20% | 61 (30%) | 71 (35%) | 56 (29%) | 58 (30%) |

| Mean cardiovascular risk (sd) | 16.4 (7.4) | 18.0 (7.6) | 16.8 (7.4) | 17.3 (7.7) |

| Difference (se) | 1.6 (0.3) | 0.6 (0.4) | ||

| Mean systolic BP mmHg (SD) | 152 (19) | 153(17) | 157 (18) | 154 (20) |

| Difference (se) | -0.6 (1.3) | -3.4 (1.5) | ||

| Mean diastolic BP mmHg (SD) | 85 (10) | 86 (9) | 86 (9) | 85 (9) |

| Difference (se) | -0.3 (0.7) | -1.1 (0.8) | ||

Table 3.

Adjusted* risk of a cardiovascular event (5 year), mean systolic and diastolic blood pressure at 12-month follow up in the two comparison groups (AR vs NNT)

| Outcome variable | Risk presented as | Risk presented as | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Absolute Risk (AR) | Number Needed to | |||

| (n = 205) | Treat (NNT) | |||

| (n = 196) | ||||

| 5-year cardiovascular risk | 180 (87.8%) | 168 (85.7%) | Adjusted odds ratio = 1.53 | p = 0.23 |

| ≥ 10% | (95%CI 0.76,3.08) | |||

| Mean absolute 5-yr risk in | 18.3 (8.0) | 18.1 (8.0) | Adjusted difference = 0.69 | p = 0.16 |

| %(SD) | (95%CI -0.27,1.66) | |||

| Mean SBP in mmHg (SD) | 153 (17) | 154 (20) | Adjusted difference = 0.97 (95%CI -2.34,4.29) | p = 0.56 |

| (95%CI -2.34,4.29) | ||||

| Mean DBP in mmHg (SD) | 86 (9) | 85 (9) | Adjusted difference = 0.70 (95%CI -1.05,2.45) | p = 0.43 |

| (95%CI -1.05,2.45) |

Outcome variables adjusted for baseline measurement of outcome variable, practice computer system and method of presentation of risk (chart or computer)

Intensity of prescribing of blood pressure lowering drugs also increased within both groups during the six months of follow up (Table 4). However, when baseline prescribing was controlled for using multinominal regression, there were no statistically significant differences between the AR and NNT groups in prescribing intensity (Table 5). The CONSORT checklist is available – see additional file

Table 4.

Number (%) of patients prescribed different numbers of blood pressure lowering drugs at baseline and six-month follow-up in the two comparison groups (AR vs NNT)

| Risk presented as Absolute Risk (AR) | Risk presented as Number Needed to | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 210) | Treat (NNT) (n = 205) | |||

| Number of classes of drugs prescribed | Baseline | 6 months | Baseline | 6 months |

| of drugs prescribed | ||||

| 0–1 | 92 (44) | 72 (34) | 94 (46) | 77 (38) |

| 2 | 67 (32) | 67 (32) | 66 (32) | 74 (36) |

| 3+ | 51 (24) | 71 (34) | 45 (22) | 54 (26) |

Table 5.

Multinominal logistic regression analysis of number of types of blood pressure lowering drugs prescribed at six months follow up adjusted for number at baseline

| Odds ratio (95% CI) compared with 0–1 classes of drug | ||

|---|---|---|

| 2 drugs | ≥ 3 drugs | |

| Risk presented as NNT | 1 | 1 |

| Risk presented as AR | 0.98 (0.50 to 1.96) | 1.79 (0.82 to 3.95) |

Χ2 on 2 degrees of freedom = 3.4 p = 0.18

Discussion

Using charts that estimate cardiovascular risk is being promoted as the most rational way to manage high blood pressure and other cardiovascular risk factors [9]. Such an approach has been adopted in the UK and New Zealand [13,14]. Less explicit risk-stratification is recommended in the US blood pressure guidelines [15]. It seems likely that provision of individualised risk information will become the starting point for evidence-based management of hypertension and other forms of cardiovascular disease [16]. In the context of individualised risk and the evidence from observational studies of "framing" effects, it is critically important to establish whether a particular format of presenting risk is superior to another. This randomized trial has shown that there appears to be little difference in presenting risk either as an AR and NNT in consultations with patients in terms of their subsequent cardiovascular risk, systolic or diastolic blood pressure levels, or prescribing intensity. The confidence limits around these estimates do not rule out a potentially important benefit favouring presentation of risk as an AR in terms of systolic blood pressure (the upper limit of 95% confidence limit was 4.29 mmHg) but this finding would require confirmation in a larger study.

Of the thirteen observational studies that have examined "framing" effects only one explicitly considered its impact on the treatment of high blood pressure [5]. This study suggested that presenting risk as an ARR was likely to be associated with more intensive drug prescribing than when risk was presented as an NNT. Our randomized trial, though not directly equivalent as risk was presented as an AR rather than ARR, does not confirm this finding. Rather it reinforces the finding from other studies of "framing" effects, which suggest that absolute risk formats, either an AR, ARR or NNT have the same impact on health professionals' prescribing intentions [1].

The NNT has been promoted as a clinically useful measure of treatment effect [2,4]. Some commentators have criticised the use of the NNT as an index of risk that may be difficult for health professionals to understand and use [17]. We found no evidence that patients' outcomes or prescribing intensity changed when the NNT was used in clinical practice guidelines compared with when AR was used as the format of presentation. However, routine use of the NNT may be problematic. Pooled NNTs derived from meta-analyses can be seriously misleading if baseline risk varies between randomized trials. [18] Furthermore, the use of an "adjusted" NNT(a ratio measurement of the NNT and NNH, number needed to harm) – has been proposed as a further refinement when deciding on the risks and benefits of treatment in individual patients [16]. It is not altogether clear whether such refinements will serve to help or confuse patients and health professionals, when discussing cardiovascular risk in the context of deciding on drug treatment [17]. It might reasonably be argued that the impact of framing is unlikely to have a large effect on either professional behaviour (as measured by changes in the intensity of blood pressure lowering drugs) or patient outcome (measured by changes in cardiovascular risk and blood pressure readings). This study shows that large effects on professional behaviour and patient outcome are unlikely to occur when risk information is presented in absolute terms, either as an NNT or AR.

There are several shortcomings with the present study. Cardiovascular risk in recruited patients was higher than anticipated, with the consequence that the study was under – powered to detect a difference in the primary outcome measure. However, all secondary outcome measures, systolic and diastolic blood pressure and prescribing intensity of blood pressure lowering drugs were unaffected by the format of risk presentation. A sample size of over 3000 patients would be necessary if a difference of 2 mmHg in systolic blood pressure was thought to be clinically important enough to detect. The intervention was directed at health professionals not patients. We do not know to what extent health professionals discussed management of hypertension with their patients and are therefore uncertain whether presenting risk in different formats would have a similar effect on patients. Lastly, a third arm of presenting risk as a relative risk reduction was not undertaken. Generation of a CDSS or production of a risk chart based on absolute risk does not facilitate presentation of risk in relative terms. All blood pressure lowering drugs produce a relative risk reduction of about one third. Producing a chart stating this single fact seemed unlikely to be of use to health professionals or patients.

At present clinical practice guidelines do not go beyond measurements of treatment efficacy, often ignoring the potential for harm and the impact of patients' preferences [3]. However, this situation is changing [19]. At the basic level, informed decision making should require estimates of treatment efficacy (both in absolute and relative terms); some measure of susceptibility to the target outcome (the absolute risk); and some measure of how precise these estimates are (95% confidence limits around the estimates) [3]. It is notable that no current cardiovascular guidelines in the UK provide this level of information in primary care. Lastly, pictorial representation of cardiovascular risk may well be subject to systematic bias in the same way that "framing" effects may exist. As a large proportion of cardiovascular risk guidelines rely on some form of pictorial representation of risk, careful consideration and empirical testing should be given to the most effective way data are displayed in clinical practice guidelines [20].

Conclusions

This randomized trial suggests that use of either the AR or the NNT should be a matter of choice for health professionals using hypertension guidelines. Further studies should examine the impact of using the NNT as an index of risk in terms of patients' preferences for treatment choices, as well as the use of other data display formats, aside from risk tables, in clinical practice guidelines.

Competing interests

None declared.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:

Supplementary Material

Consort checklist for Randomised Controlled Trials

Contributor Information

Tom Fahey, Email: tom.fahey@bristol.ac.uk.

Alan A Montgomery, Email: alan.a.montgomery@bristol.ac.uk.

Tim J Peters, Email: tim.peters@bristol.ac.uk.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all the 20 Avon practices for participating in this study. This study was supported by Wales Research & Development grant number RC016. TF is supported as a NHS R&D Primary Care Career Scientist. AM is supported as a UK Medical Research Council Training Fellow in Health Services Research.

References

- McGettigan P, Sly K, O'Connell D, Hill S, Henry D. The effects of information framing on the practices of physicians. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2000;14:633–642. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1999.09038.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laupacis A, Sackett D, Roberts R. An assessment of clinically useful measures of the consequences of treatment. The New England Journal of Medicine. 1988;318:1728–1733. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198806303182605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sackett D, Cook R. Understanding clinical trials. British Medical Journal. 1994;309:755–756. doi: 10.1136/bmj.309.6957.755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook R, Sackett D. The number needed to treat: a clinically useful measure of reatment effect. British Medical Journal. 1995;310:452–454. doi: 10.1136/bmj.310.6977.452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cranney M, Walley T. Same information, different decisions: the influence of evidence on the management of hypertension in the elderly. British Journal of General Practice. 1997;46:661–663. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skolbekken J. Communicating the risk reduction acheived by cholesterol reducting drugs. British Medical Journal. 2000;316:1956–1958. doi: 10.1136/bmj.316.7149.1956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eccles M, Ford G, Duggan S, Steen N. Are postal questionnaire surveys of reported activity valid? An exploration using general practitioner management of hypertension in older people. British Journal of General Practice. 1999;49:35–38. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson KM, Odell PM, Wilson PWF, Kannel WB. Cardiovascular disease risk profiles. American Heart Journal. 1991;121:293–298. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(91)90861-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson RT, Sackett DL. Guidelines for managing raised blood pressure. ritish Medical Journal. 1996;313:64–65. doi: 10.1136/bmj.313.7049.64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery AA, Fahey T, Peters TJ, MacKintosh C, Sharp D. Evaluation of a computer-based clinical decision support system and chart guidelines in the management of hypertension in primary care: a randomized controlled trial. British Medical Journal. 2000;320:686–690. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7236.686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fahey T, Peters TJ. What constitutes controlled hypertension? A patient-based comparison of hypertension guidelines. British Medical Journal. 1996;313:93–96. doi: 10.1136/bmj.313.7049.93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dormer A, Birkett N, Buck C. Randomization by cluster. American Journal of Epidemiology. 1981;114:906–914. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a113261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramsay LE, Williams B, Johnston G. Guidelines for the management of hypertension: report of the third working party of the British Hypertension Society. Journal of Human Hypertension. 1999;13:569–592. doi: 10.1038/sj.jhh.1000917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Working Party of the British Cardiac Society, British Hyperlipidaemia Association and British Hypertension Society. Joint British recommendations on prevention of coronary heart disease in clinical practice. Heart. 1998;80 (Suppl. 2):S1–S29. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joint National Committee. The sixth report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation and Treatment of High Blood Pressure. National Institutes of Health, 1997.

- McAlister F, Straus SE, Guyatt G. Users' guides to the Medical Literature XX. Integrating Research Evidence with the care of the individual patient. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2000;283:2829–2836. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.21.2829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowie J. The 'number needed to treat' and the 'adjusted NNT' in health care decision-making. Journal of Health Services Research and Policy. 1998;3:44–49. doi: 10.1177/135581969800300110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smeeth L, Haines A, Ebrahim S. Number needed to treat derived from meta-analyses – sometimes informative, usually misleading. British Medical Journal. 2000;318:1548–1551. doi: 10.1136/bmj.318.7197.1548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomson R, Parkin D, Eccles M, Sudlow M, Robinson A. Decision analysis and guidelines for anticoagulation therapy to prevent stroke in patients with atrial fibrillation. Lancet. 2000;355:956–962. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)90012-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elting L, Martin C, Cantor S, Rubenstein E. Influence of data display formats on physician investigators' decisions to stop clinical trials: prospective trial with repeated measures. British Medical Journal. 2000;318:1527–1531. doi: 10.1136/bmj.318.7197.1527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Consort checklist for Randomised Controlled Trials