Abstract

Marrow-resident mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) serve as a functional component of the perivascular niche that regulates hematopoiesis. They also represent the main source of bone formed in adult bone marrow, and their bifurcation to osteoblast and adipocyte lineages plays a key role in skeletal homeostasis and aging. Although the tumor suppressor p53 also functions in bone organogenesis, homeostasis, and neoplasia, its role in MSCs remains poorly described. Herein, we examined the normal physiological role of p53 in primary MSCs cultured under physiologic oxygen levels. Using knockout mice and gene silencing we show that p53 inactivation downregulates expression of TWIST2, which normally restrains cellular differentiation to maintain wild-type MSCs in a multipotent state, depletes mitochondrial reactive oxygen species (ROS) levels, and suppresses ROS generation and PPARG gene and protein induction in response to adipogenic stimuli. Mechanistically, this loss of adipogenic potential skews MSCs toward an osteogenic fate, which is further potentiated by TWIST2 downregulation, resulting in highly augmented osteogenic differentiation. We also show that p53−/− MSCs are defective in supporting hematopoiesis as measured in standard colony assays because of decreased secretion of various cytokines including CXCL12 and CSF1. Lastly, we show that transient exposure of wild-type MSCs to 21% oxygen upregulates p53 protein expression, resulting in increased mitochondrial ROS production and enhanced adipogenic differentiation at the expense of osteogenesis, and that treatment of cells with FGF2 mitigates these effects by inducing TWIST2. Together, these findings indicate that basal p53 levels are necessary to maintain MSC bi-potency, and oxygen-induced increases in p53 expression modulate cell fate and survival decisions. Because of the critical function of basal p53 in MSCs, our findings question the use of p53 null cell lines as MSC surrogates, and also implicate dysfunctional MSC responses in the pathophysiology of p53-related skeletal disorders.

Introduction

The tumor suppressor p53 is induced in cells in response to genotoxic and oncogenic stress and functions as a critical checkpoint control in cancer surveillance by inducing antiproliferative and pro-apoptotic cellular responses. Consequently, mutations in p53 are by far the most common cancer-related genetic defect [1] and predispose patients to a range of cancers including osteosarcoma, leukemia, and lymphoma [2–4]. Although basal expression of p53 was initially thought to be dispensable for normal cell survival, recent studies have demonstrated a requirement for the protein in early development, reproduction, energy metabolism, and hematopoiesis [5]. For example, p53 has been shown to maintain hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) in a quiescent state by modulating the expression of growth suppressors and intracellular levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS) [6, 7], which can significantly impact stem and progenitor cell functions under normal and pathologic conditions [8]. Therefore, by coordinating autoregulatory responses to physiological levels of ROS and acting as a sensor of DNA damage induced by excessive ROS, p53 provides a critical link between cancer surveillance, stem cell maintenance, and organismal aging [5, 9].

Skeletal homeostasis is regulated by the coordinated action of bone-producing osteoblasts and bone-resorbing osteoclasts. Bone formation declines with age because of an imbalance between these processes resulting in loss of bone mass. Skeletal aging also manifests as an increase in bone marrow adiposity, which further accelerates bone loss as secreted fatty acids and adipokines inhibit osteoblast function and promote osteoclast activity through paracrine action [10–12]. Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) play an important role in skeletal homeostasis by serving as a reservoir of osteoblast precursors [13] and studies have linked age-related bone loss to defects in MSC function including loss of proliferative and differentiation potential and increased senescence [14]. Cellular oxidative stress is also strongly linked to skeletal aging and has been shown to skew MSC differentiation toward adipogenesis at the expense of osteogenesis, which also contributes to increased marrow adiposity [15]. Since MSCs also contribute to the architecture of the hematopoietic niche, age-related changes in their function are likely to manifest as defects in hematopoiesis. Despite the important connection between oxidative stress, MSC self-maintenance, and skeletal aging, the interrelated aspects of how p53 regulates these processes and how its inactivation alters MSC function are poorly described.

We previously reported that primary MSCs isolated from mouse bone marrow are hypersensitive to oxygen-induced stress, that this stress induces growth arrest and apoptosis via a p53-dependent pathway, and inactivation of p53 renders MSCs insensitive to such stress [16]. We show here that p53 inactivation strongly biases MSCs to an osteogenic fate at the expense of adipogenesis because of depletion of mitochondrial ROS and diminished PPARG and TWIST2 expression, and impairs hematopoiesis-supporting activity by altering cytokine secretion. We further demonstrate an important role for TWIST2 in regulating MSC growth, survival, and multipotency, and that FGF2 potentiates TWIST2 expression and mitigates oxygen-induced mitochondrial ROS generation by suppressing p53 induction. Together, these data reveal a critical role for basal p53 expression in maintaining MSC integrity, and in doing so urge caution in using immortalized cell lines to model primary MSC behavior and activity. They also suggest that alterations in MSC function resulting from p53 inactivation may contribute more significantly to the pathophysiology of skeletal-related diseases than currently appreciated.

Results

Inactivation of p53 skews MSCs to an osteogenic fate and impairs hematopoiesis-supporting activity

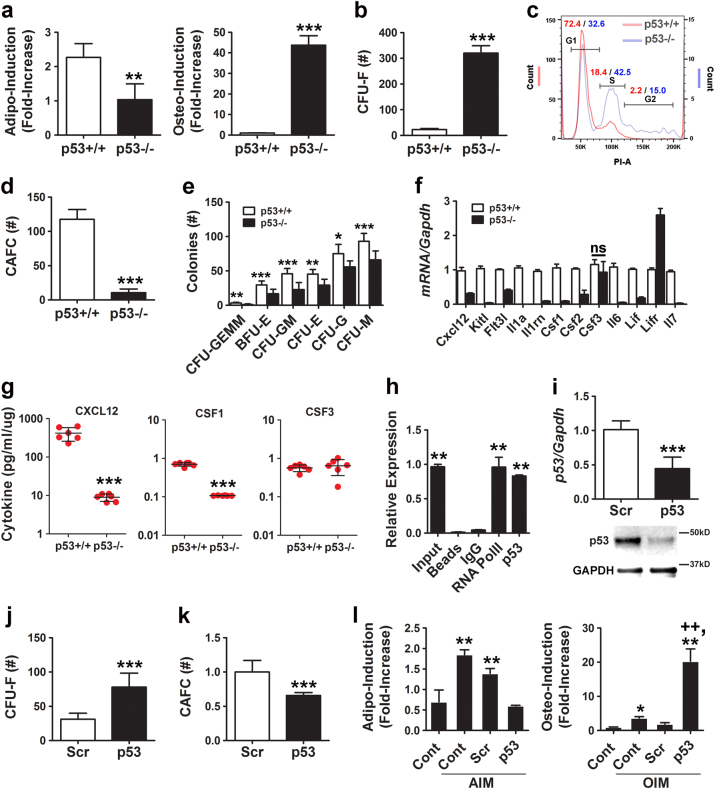

To explore a potential role for p53 in MSC self-maintenance, we evaluated how deletion of this gene impacted two defining cell characteristics: lineage-specific differentiation and hematopoiesis-supporting activity. Primary MSCs isolated from p53 knockout (p53−/−) mice and maintained in a closed low-oxygen (5%) environment exhibited a 2-fold reduced capacity for stimulus-driven adipogenic differentiation, while osteogenic capacity was augmented >40-fold as compared to MSCs from wild-type (p53+/+) mice (Fig. 1a and Supplementary Fig. 1a). In addition, p53−/− MSCs yielded significantly more colony-forming unit fibroblasts (CFU-Fs) (Fig. 1b) and contained a greater proportion of cycling cells (Fig. 1c) as compared to p53+/+ MSCs. Moreover, p53−/− vs. p53+/+ MSCs were defective in supporting growth of cobblestone area-forming cells (CAFCs; Fig. 1d) and erythroid, monocyte, and granulocyte progenitors from normal bone marrow (Fig. 1e): two independent measures of hematopoiesis-supporting activity. Consistent with these findings, quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) revealed that expressed levels of Cxcl2, Kitl, Flt3l, Il1a, Il1rn, Csf1, Csf2, Il6, Lif, and Il7 were significantly lower in p53−/− vs. p53+/+ MSCs (Fig. 1f) and multiplex arrays confirmed that p53−/− vs. p53+/+ MSCs secreted significantly lower levels of CXCL12 and CSF1 (Fig. 1g), which are expressed by MSCs in bone marrow and support hematopoiesis [17–19]. We also identified a p53 response element (RE) with half sites that correspond to the canonical activating motif (RRRCWWGYYY) [20] in the Kitl promoter (Supplementary Fig. 2a) and confirmed by chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) that p53 associated with this promoter (Fig. 1h). Together, these data demonstrate that p53 inactivation impairs the differentiation potential and hematopoiesis-supporting activity of MSCs.

Fig. 1.

Basal p53 expression maintains MSC integrity. a Quantification of stimulus-induced adipogenic (left panel) and osteogenic (right panel) differentiation of p53+/+ vs. p53−/− MSCs. Data are mean ± S.D. of experiments (n = 4) repeated twice. **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.005 by Student’s t-test. b CFU-F activity of p53+/+ vs. p53−/− MSCs. Data are mean ± S.D. of experiments (n = 6) repeated twice. ***p < 0.005 by Student’s t-test. c Flow cytometric analysis of PI-stained cells showing percentage of p53+/+ vs. p53−/− MSCs in G1, S, and G2 phases of cell cycle. d CAFC activity of p53+/+ vs. p53−/− MSCs. Data are mean ± S.D. of experiments (n = 6) repeated twice. ***p < 0.005 by Student’s t-test. e Methylcellulose colony-forming assays using conditioned media from p53+/+ vs. p53−/− MSCs. Data are mean ± S.D. of experiments (n = 3) repeated twice. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.005 by Student’s t-test. f qPCR analyses of the indicated mRNAs in p53+/+ vs. p53−/− MSCs. All cytokine levels were significantly (**p < 0.01) different between cell types by Student’s t-test (n = 3) except where indicated. g Luminex-based analyses of conditioned media collected from monolayer cultures of p53+/+ vs. p53−/− MSCs. ***p < 0.005 by Student’s t-test. h ChIP showing pull-down of Kitl promoter sequences using a RNA Pol II (positive control) or p53 antibody from cell extracts of p53+/+ MSCs treated with Nutlin-3a (20 µM). **p < 0.01 compared to IgG control by ANOVA and Tukey post hoc test. i p53 mRNA and protein expression quantified by qPCR (upper panel) and immunoblot analysis (bottom panel), respectively, in p53+/+ MSCs transfected with a scrambled (Scr) and p53-specific siRNA. qPCR data are mean ± SD of experiments (n = 3) repeated twice. ***p < 0.005 by Student’s t-test. j, k Effect of siRNAs on CFU-F (j) and CAFC (k) activity in p53+/+ MSCs. Data are mean ± SD of experiments (n = 6) repeated twice. ***p < 0.005 by Student’s t-test. l Quantification of stimulus-induced adipogenic (left panel) and osteogenic (right panel) differentiation of siRNA-transfected p53+/+ MSCs. Data are mean ± SD (n = 4). **p < 0.01 compared to unstimulated control and ++p < 0.01 compared to scrambled (Scr) by ANOVA and Tukey post hoc test

To confirm a role for p53 in MSC self-maintenance, we inhibited expression of this protein in wild-type MSCs using a small interfering RNA (siRNA; Fig. 1i), which resulted in downregulation of known target genes including p21 (Cip1), Bax, and Foxo3a but not p27 (Kip1), which is not regulated by p53 (Supplementary Fig. 1b). Changes in target gene expression due to p53 silencing mirrored that seen following p53 inactivation, although the effect was less pronounced (Supplementary Fig. 1c). Silencing of p53 also significantly increased CFU-F activity (Fig. 1j) and augmented stimulus-driven osteogenic differentiation (Fig. 1l) but inhibited hematopoiesis-supporting activity (Fig. 1k) and adipogenic differentiation (Fig. 1l). Flow cytometric analysis using a panel of established MSC markers failed to reveal significant differences in the surface phenotype of p53−/− vs. p53+/+ MSCs except for a shift in staining intensity for CD146 and SSEA4 (Supplementary Fig. 3). Therefore, p53 inactivation alters MSC bi-potency and hematopoiesis-supporting activity but these functional changes are not evident based on surface phenotype.

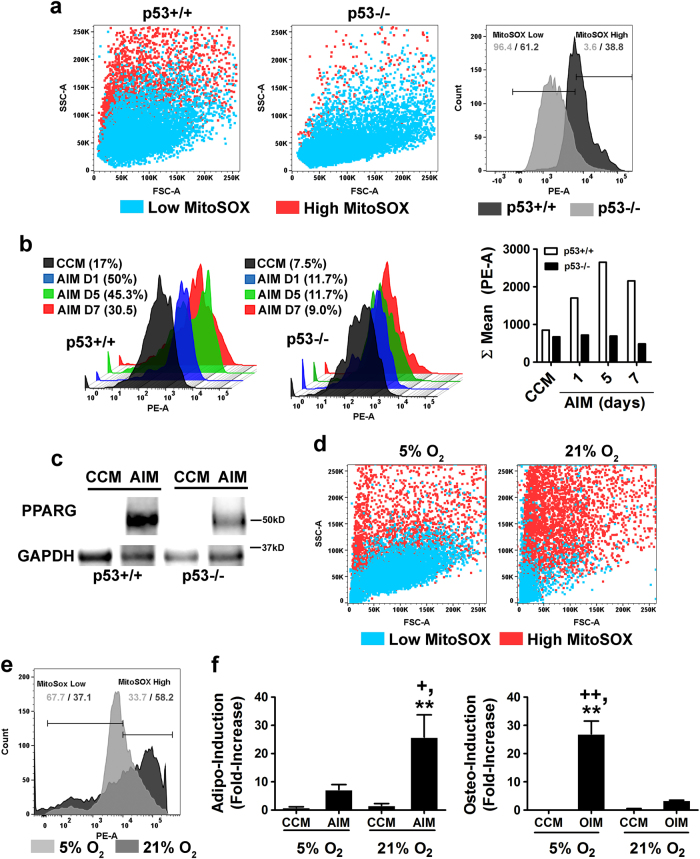

Diminished mitochondrial ROS production leads to impaired adipogenesis in p53−/− MSCs

Exposure of primary mouse MSCs to atmospheric oxygen induces mitochondrial ROS generation via a p53-dependent mechanism [16]. Herein, we show that mitochondrial superoxide generation was markedly lower in p53−/− (3.6%) vs. p53+/+ (38.8%) MSCs after 1 week of continuous culture in 5% oxygen based on flow cytometric analysis of MitoSOXTM Red-stained populations (Fig. 2a). Since ROS generation by mitochondrial complex III is required for initiation of the adipogenic program in MSCs [21, 22], we questioned whether low mitochondrial ROS output contributed to the reduced adipogenic potential of p53−/− MSCs. While p53+/+ MSCs showed a burst of mitochondrial ROS production following exposure to adipogenic induction media (AIM) over a 7-day time course, no such response was evident in p53−/− MSCs (Fig. 2b). Moreover, while AIM treatment induced PPARG expression in both populations, protein levels were markedly higher in p53+/+ vs. p53−/− MSCs (Fig. 2c). To artificially elevate intracellular ROS levels, we cultured p53−/− MSCs in media supplemented with D-galactose (0.5–2.0 mM) and galactose oxidase (0.015–0.06 U/ml), which continuously generates H2O2 in the culture media that diffuses into cells. This treatment produced incremental increases in mitochondrial ROS levels resulting in a slight enhancement of adipogenic differentiation but had no significant effect on osteogenic differentiation (Supplementary Figs. 4a, b). Next, we cultured p53+/+ MSCs in the presence of the ROS scavenger, NAC, which lowers mitochondrial ROS levels [16]. MSCs pretreated with NAC produced significantly lower levels of mitochondrial ROS after exposure to AIM as compared to non-treated MSCs (Supplementary Fig. 4c), which resulted in reduced capacity for adipogenic differentiation, although this difference did not reach statistical significance (Supplementary Fig. 4d). Together, these data underscore the extent of mitochondrial ROS generation induced by AIM, which is only modestly reduced by NAC, and why the absence of ROS generation in p53−/− MSCs prevents adipogenic differentiation. Lastly, we shifted p53+/+ MSCs maintained in 5% oxygen saturation to 21% oxygen, which we previously showed induces p53 activation in response to oxidative DNA damage [16]. This shift resulted in increased mitochondrial ROS production (Figs. 2d, e), resulting in enhanced adipogenic differentiation and decreased osteogenic differentiation (Fig. 2f). Importantly, prolonged exposure to 21% oxygen decreased overall MSC fitness [16] resulting in loss of both adipogenic and osteogenic potential (Supplementary Fig. 4e). Together, these studies highlight the necessity of basal p53 in regulating the cellular redox balance in MSCs and how p53 translates varying levels of oxidative stress to regulate differentiation or apoptosis.

Fig. 2.

Basal p53 expression regulates the cellular redox balance in MSCs. a Dot plots (left) and histogram (right) of flow cytometric analysis of MitoSOXTM Red-stained p53+/+ vs. p53−/− MSCs. Horizontal lines in the histogram illustrate gating strategy for MitoSOXTM low and high populations. b Representative histograms depicting changes in mitochondrial ROS generation in p53+/+ vs. p53−/− MSCs over a 7-day time course of AIM exposure based on flow cytometric analysis of MitoSOXTM Red-stained cells. Bar graph (right panel) illustrates mean fluorescence intensity in the PE channel from each experimental sample. c Immunoblots of whole-cell extracts from MSC populations in (b) probed with anti-PPARG and anti-GAPDH antibodies. d Dot plots from flow cytometric analysis of MitoSOXTM Red-stained MSCs cultured in 5 or 21% oxygen saturation. e Histogram of flow cytometric data in (d). Horizontal lines illustrate gating strategy for MitoSOXTM low and high populations. f Effect of oxygen saturation levels (5% vs. 21%) on stimulus-driven adipogenic (left panel) and osteogenic (right panel) differentiation of MSCs. Data are mean ± S.D. (n = 4). **p < 0.01 vs. CCM, +p < 0.5 vs AIM, and ++p < 0.01 vs. OIM by one-way ANOVA and Tukey post hoc test

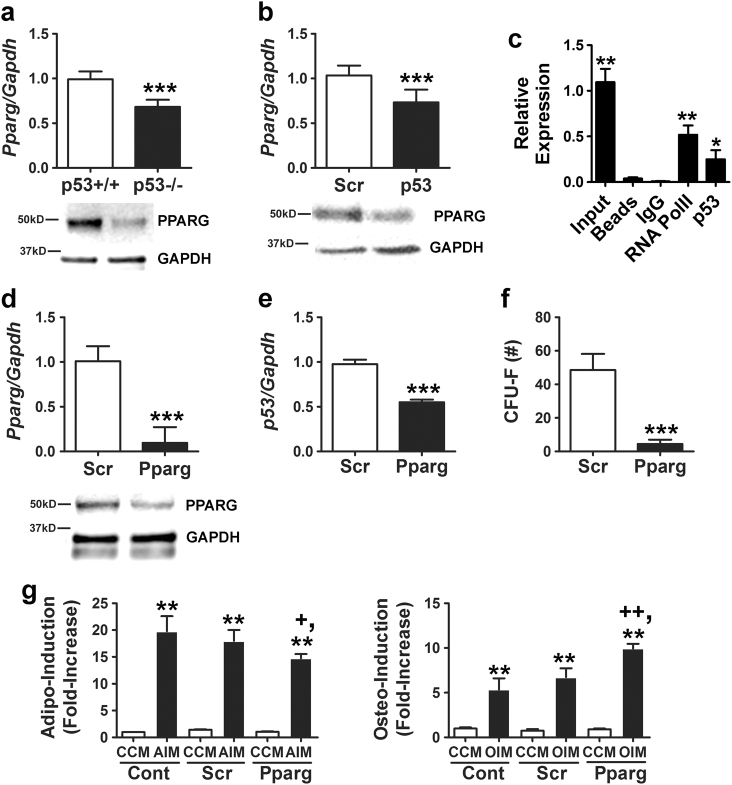

Inactivation of p53 suppresses PPARG levels in MSCs

PPARG is a master regulator of adipogenesis, and numerous studies have shown that PPARG agonists decrease bone mineral density [23–25]. We found that PPARG mRNA and protein were expressed at significantly lower levels in p53−/− vs. p53+/+ MSCs (Fig. 3a) and that several PPARG target genes including Pgc1 and Fabp4 were also significantly downregulated (not shown). Consistent with these results, siRNA-mediated silencing of p53 in wild-type MSCs resulted in a modest but significant decrease in PPARG mRNA and protein expression (Fig. 3b). Analysis of the Pparg gene sequence identified a consensus activating p53 RE in an intronic region between exons 12 and 13 (Supplementary Fig. 2b), and ChIP analyses determined that p53 associated with this region (Fig. 3c). However, further studies are required to determine whether p53 binding at this site directly regulates Pparg transcription. To ascertain effects of PPARG downregulation on MSC function, we silenced its expression in p53+/+ MSCs using siRNAs (Fig. 3d). This resulted in downregulation of p53 mRNA levels (Fig. 3e), which is consistent with previous studies showing that PPARG induces p53 transcription via binding to an NF-k B site in its promoter [26]. Silencing of PPARG also significantly reduced CFU-F activity (Fig. 3f) and inhibited stimulus-driven adipogenic differentiation while enhancing osteogenic differentiation (Fig. 3g). Together, these data indicate that PPARG downregulation following p53 inactivation contributes to the skewing of cells toward an osteogenic fate at the expense of adipogenesis.

Fig. 3.

Diminished PPARG expression alters the adipogenic potential of p53−/− MSCs. a PPARG protein and mRNA expression quantified by qPCR (upper panel) and immunoblot analyses. The blot for this panel is a duplication from Figure 1i by mistake. Dr. Shi requested that we add the correct blot panel. Therefore, I have created a revised figure 3R2 with the corrected panel. Not sure I can attach it here but will e-mail if not (bottom panel), respectively, in p53+/+ vs. p53−/− MSCs. QPCR data are mean ± S.D. of experiments (n = 3) repeated twice. ***p < 0.005 by Student’s t-test. b, d PPARG mRNA and protein expression quantified by qPCR (upper panel) and immunoblot analyses (bottom panel), respectively, in MSCs transfected with a scrambled (Scr) and p53-specific siRNA (b) or Scr and Pparg-specific siRNA (d). QPCR data are mean ± S.D. of experiments (n = 3) repeated twice. ***p < 0.005 by Student’s t-test. c ChIP showing pull-down of Pparg promoter sequences using a RNA Pol II (positive control) or p53 antibody from cell extracts of p53+/+ MSCs treated with Nutlin-3a (20 µM). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 compared to IgG control by ANOVA and Tukey post hoc test. e qPCR of Pparg mRNA levels in MSCs transfected with a p53-specific siRNA. Data are mean ± S.D. of experiments (n = 3) repeated three times. ***p < 0.005 by Student’s t-test. f Effect of siRNAs on CFU-F activity in MSCs. Data are mean ± S.D. of experiments (n = 6). ***p < 0.005 by Student’s t-test. g Effect of siRNAs on stimulus-induced adipogenic (left panel) and osteogenic (right panel) differentiation. Data are mean ± S.D. of experiments (n = 4). **p < 0.01 compared to CCM, +p < 0.05 vs. Scr + AIM, and ++p < 0.01 vs.Scr + OIM by one-way ANOVA and Tukey post hoc test

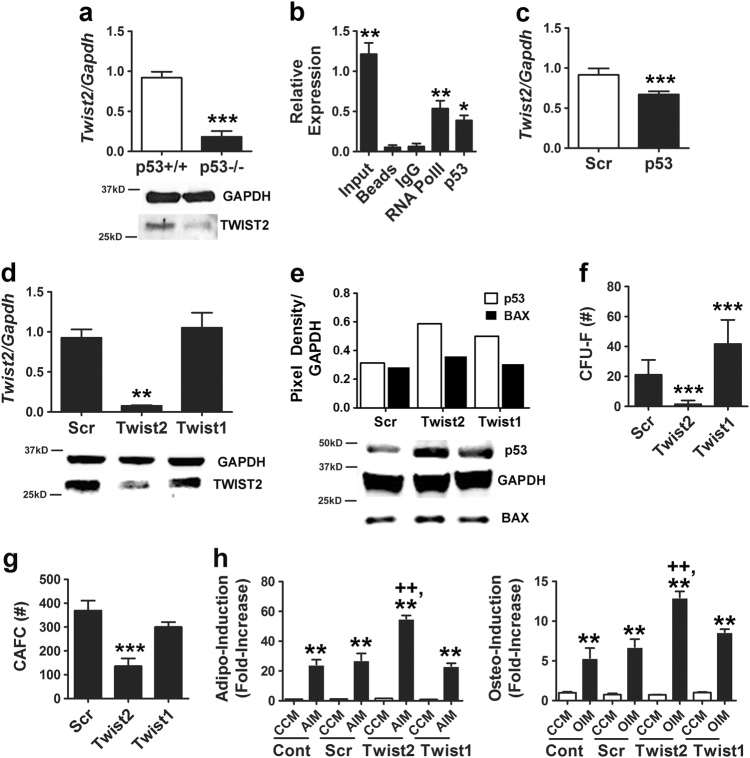

Reduced TWIST2 expression following p53 inactivation results in unrestrained cell growth and differentiation

On the basis of studies showing that TWIST2 inhibits differentiation of primary mouse MSCs [27], we questioned whether p53 inactivation affected TWIST2 levels and whether this contributed to alterations in cell function. As shown in Fig. 4a, p53−/− vs. p53+/+ MSCs expressed significantly lower levels of TWIST2 mRNA and protein. A bioinformatics search revealed an activating p53 RE in the Twist2 promoter (Supplementary Fig. 2c), and ChIP analysis confirmed that p53 associated with this promoter (Fig. 4b). Expressed levels of Twist1 were also reduced in p53−/− MSCs but to a lesser extent than Twist2 (1.4-fold vs. 5-fold, respectively; Supplementary Fig. 5a). Consistent with these findings, Twist2 mRNA levels in wild-type MSCs were repressed by transfection with a p53-specific siRNA (Fig. 4c), and, conversely, silencing of Twist2 (Fig. 4d) resulted in increased p53 and BAX protein expression while silencing of Twist1 yielded more modest increases in p53 but had no effect on BAX levels (Fig. 4e). Silencing of TWIST2 also significantly impaired cell growth and survival (Supplementary Figs. 5b–d), significantly inhibited CFU-F (Fig. 4f) and CAFC activity (Fig. 4g), and significantly enhanced the extent of stimulus-driven adipogenic and osteogenic differentiation (Fig. 4h). In contrast, silencing of TWIST1 had no effect on MSC growth and survival (Supplementary Figs. 5b–d), CAFC activity (Fig. 4g), or cellular differentiation (Fig. 4h) but did significantly increase CFU-F activity (Fig. 4f). Together, these data indicate that Twist2 and p53 expression are coordinately regulated in MSCs.

Fig. 4.

TWIST2 expression is downregulated in MSCs following p53 inactivation. a qPCR (top panel) and immunoblot (bottom panel) analyses of TWIST2 mRNA and protein levels, respectively, in p53−/− vs, p53+/+ MSCs. qPCR data are mean ± S.D. of experiments (N = 2) repeated twice. ***p < 0.005 by Student’s t-test. b ChIP showing pull-down of Twist2 promoter sequences using a RNA Pol II (positive control) or p53 antibody from cell extracts of MSCs treated with Nutlin-3a (20 µM). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 compared to IgG control by ANOVA and Tukey post hoc test. c Effect of siRNAs on Twist2 mRNA levels as determined by qPCR. Data are mean ± S.D. of experiments (N = 2) repeated three times. ***p < 0.005 by Student’s t-test. d qPCR (top panel) and immunoblot (bottom panel) analyses showing effect of siRNAs on TWIST2 mRNA and protein expression, respectively, in MSCs. qPCR data are mean ± S.D. of experiments (N = 2) repeated twice. **p < 0.01 compared to Scr by Student’s t-test. e Densitometry (top panel) and immunoblot (lower panel) showing effect of siRNAs on BAX and p53 protein expression in MSCs. f, g Effect of siRNAs on CFU-F (f) and CAFC activity (g) in MSCs. Data are mean ± S.D. of experiments (N = 6) repeated twice for CAFC and three times for CFU-F. ***p < 0.005 compared to Scr by Student’s t-test. h Effect of siRNAs on stimulus-driven adipogenic (left panel) and osteogenic (right panel) differentiation. Data are mean ± S.D. of experiments (N = 4). **p < 0.01 compared to CCM, ++p < 0.01 compared to Scr + AIM or Scr + OIM by ANOVA and Tukey post hoc test

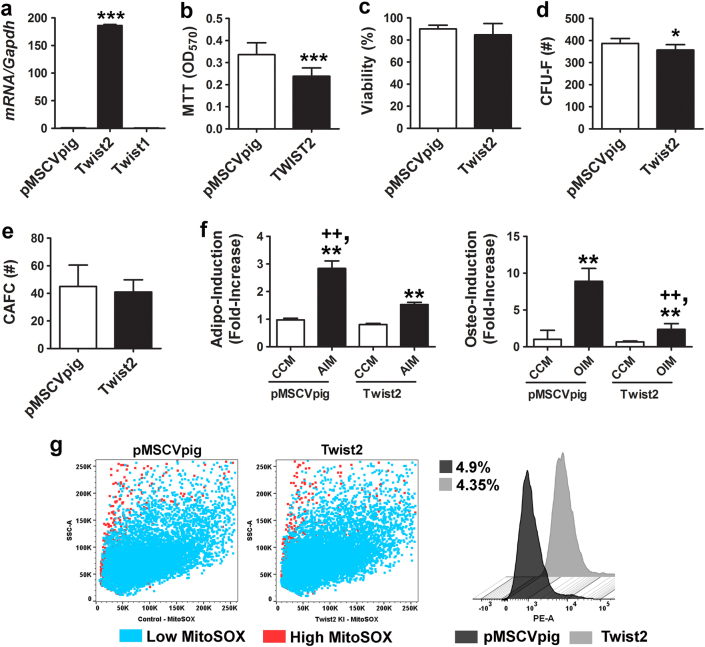

Next, we transduced p53−/− MSCs with a retrovirus expressing a full-length Twist2 cDNA, internal ribosomal entry site (IRES), and a GFP reporter, and double sorted cells to enrich for those that express high levels of GFP fluorescence by flow cytometry (Supplementary Figure 5e). As anticipated, these cells expressed >150-fold higher levels of Twist2 as compared to those transduced with an empty expression vector (Fig. 5a). Ectopic expression of Twist2 in p53−/− MSCs resulted in a small but significant decrease in cell growth (Fig. 5b) without significantly altering cell viability (Fig. 5c), and significantly reduced CFU-F activity (Fig. 5d), had no effect on CAFC activity (Fig. 5e), and significantly reduced stimulus-driven adipogenic and osteogenic differentiation (Figs. 5f, g). However, ectopic TWIST2 expression did not alter mitochondrial ROS production in p53−/− MSCs (Fig. 5h), indicating that its ability to suppress cellular differentiation was independent of the cellular redox state. Repeated attempts to ectopically express a full-length p53 cDNA in p53−/− MSCs yielded only low levels of protein expression even following cell sorting (not shown) due to the negative selection pressure it imparts on primary MSCs. Together, these data indicate that re-introduction of TWIST2 partially restores growth control and bi-potency to p53−/− MSCs.

Fig. 5.

Ectopic TWIST2 expression in p53−/− MSCs represses differentiation but does not affect cellular redox state. a QPCR of Twist2 and Twist1 mRNA levels in p53−/− MSCs transduced with an empty or Twist2-expressing retroviral vector (pMSCVpig). Data are mean ± S.D. of experiments (n = 3). ***p < 0.005 by Student’s t-test. b–e Effect of ectopic Twist2 expression on growth (b), viability (c), CFU-F activity (d), and CAFC activity (e) of p53−/− MSCs. Data are mean ± S.D. of experiments (n = = 3–6). *p < 0.05 compared to pMSCVpig by Student’s t-test. f Effect of ectopic Twist2 expression on stimulus-driven adipogenic (left panel) and osteogenic (right panel) differentiation. Data are mean ± S.D. of experiments (n = 6) repeated twice. **p < 0.01 compared to CCM and ++p < 0.01 compared to AIM or OIM by ANOVA and Tukey post hoc test. g Dot plots (left panels) and histogram (right panel) of flow cytometric analysis of MitoSOXTM Red-stained p53−/− MSCs. Numbers indicate percentage of MitoSOXTM Red high-expressing cells

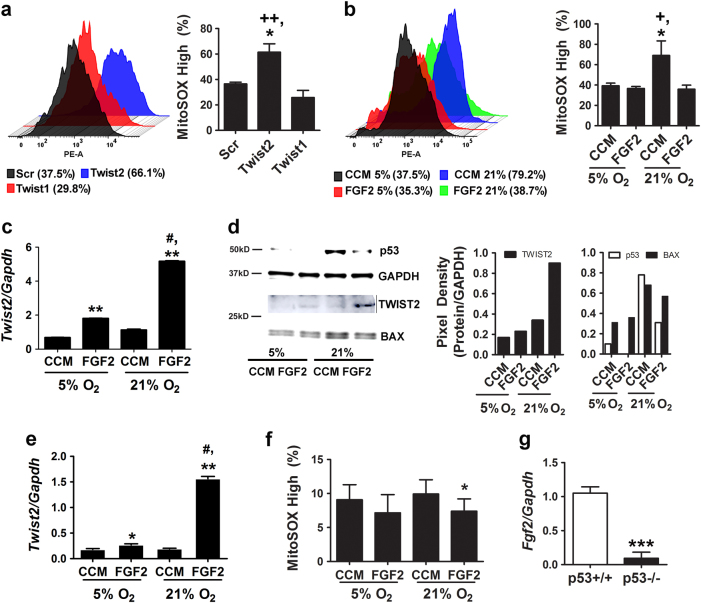

FGF2-mediated induction of TWIST2 suppresses oxygen-induced ROS generation via a p53-dependent mechanism

To determine whether TWIST2 modulates mitochondrial ROS generation in MSCs via a p53-dependent mechanism, we showed that siRNA-mediated silencing of Twist2 but not Twist1 resulted in a significant increase in mitochondrial ROS levels in wild-type MSCs (Fig. 6a and Supplementary Fig. 6a). Next, we cultured MSCs in CCM alone or media supplemented with FGF2 to induce Twist2 expression [27], and then switched cells from 5 to 21% oxygen saturation to induce oxidative stress [16]. MSCs supplemented with FGF2 (25 ng/ml) were refractory to oxygen-induced increases in mitochondrial ROS production when switched to higher oxygen levels (Fig. 6b and Supplementary Fig. 6b). Furthermore, we found that the magnitude of Twist2 induction by FGF2 was significantly greater in 21% vs. 5% O2 (Fig. 6c). Two-way ANOVA analysis confirmed significant effects on Twist2 expression due to time and oxygen saturation (F(6,11) = 5.14, p = 0.0000034) and time and FGF2 treatment (F(6,11) = 5.14, p = 0.0000021). Immunoblot analysis confirmed that TWIST2 protein levels mirrored that of its mRNA and accumulated to high levels in cells switched from 5 to 21% oxygen saturation in the presence of FGF2 (Fig. 6d). BAX and p53 were also upregulated in MSCs exposed to 21% oxygen, but induction of these proteins was suppressed in FGF2-treated cells (Fig. 6d). In contrast, FGF2 did not induce Twist1 expression, which itself was also not highly induced in response to oxidative stress (Supplementary Fig. 6c). Together, these data indicate that FGF2 treatment mitigates oxygen-induced ROS generation by inducing TWIST2 expression, which moderates p53 induction in response to such stress.

Fig. 6.

FGF2 modulates the cellular redox balance via regulation of TWIST2. a, b Histograms (left panel) and percentage of MitoSOX Red high cells (right panel) from flow cytometric analysis of MitoSOXTM Red-stained p53+/+ MSCs transfected with the indicated siRNAs (a) or cultured in CCM supplemented with or without FGF2 (20 ng/ml) under 5 or 21% oxygen saturation (b). Data are mean ± S.D. of experiments run in duplicate. *p < 0.05 compared to Scr, ++p < 0.01 compared to Twist1 by Student’s t-test. *p < 0.05 compared to CCM, +p < 0.05 compared to FGF2 treated by ANOVA and Tukey post hoc test. c QPCR analysis of Twist2 mRNA levels in p53+/+ MSCs from (b). Data are mean ± S.D. of experiments (N = 3) repeated twice. **p < 0.01 compared to CCM, #p < 0.01 vs. FGF2 by ANOVA and Tukey post hoc test. d Immunoblots (left panel) and densitometry (right panels) showing TWIST2, BAX, and p53 protein expression in cells from (b). e qPCR analysis of Twist2 mRNA levels in p53−/− MSCs treated as in (b). Data are mean ± S.D. of experiments (N = 3) repeated twice and normalized to data shown in (c). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 compared to CCM, #p < 0.01 vs. FGF2 by ANOVA and Tukey post hoc test. f Percentage of MitoSOX Red high cells based on flow cytometric analysis of MitoSOXTM Red-stained p53−/− MSCs cultured in CCM supplemented with or without FGF2 (20 ng/ml) under 5 or 21% oxygen saturation. Data are mean ± S.D. of experiments run in duplicate. *p < 0.05 compared to CCM by ANOVA and Tukey post hoc test. g qPCR analysis of normalized Fgf2 mRNA levels in p53−/− vs. p53+/+ MSCs. Data are mean ± S.D. of experiments (n = 3) repeated twice. ***p < 0.005 by Student’s t-test

To further dissect the roles of FGF2, p53, and TWIST2 in this process, we quantified changes in Twist2 expression levels in p53−/− MSCs treated with or without FGF2. As shown in Fig. 6e, FGF2 also significantly induced Twist2 mRNA in p53−/− MSCs maintained in 5% oxygen, and the magnitude of this induction was significantly greater in 21% oxygen. Therefore, Twist2 expression retains its sensitivity to FGF2 in a p53 null background, although overall expression levels are lower as compared to wild-type MSCs (data are normalized to that shown in Fig. 6c for comparison). In addition, we showed that FGF2 supplementation was able to reduce ROS levels in p53−/− MSCs cultured in 5 or 21% oxygen (Fig. 6f), but the effect was minimal due to low intrinsic ROS levels in these cells. Lastly, we also found that Fgf2 mRNA levels were significantly lower (Fig. 6g) and Fgfr2 mRNA levels were significantly higher (Supplementary Fig. 6d) in p53−/− vs. p53+/+ MSCs, implying that a block in FGF signaling accounts for reduced TWIST2 levels in p53−/− MSCs. Together, these data indicate that FGF2 induces Twist2 expression independent of p53 but that p53 itself is the dominant regulator of Twist2 in MSCs.

Discussion

Inactivation of p53 drives osteogenesis of adipose and marrow-derived MSCs [28, 29] by de-repressing Runx2 expression and exerts beneficial effects on cell growth in vitro [30]. These results are consistent with the known role of p53 as a negative regulator of osteogenesis based on evidence that germline deletion of this gene in mice results in a high bone mass phenotype [31] and increased propensity of developing osteosarcoma. Our results provide new insight into the mechanisms by which p53 regulates bifurcation of stem/progenitors to osteogenic and adipogenic lineages. For example, we demonstrate that p53 inactivation in MSCs suppresses basal and inducible levels of PPARG mRNA and protein, and that p53−/− MSCs are characterized by low basal mitochondrial ROS levels. Existing evidence indicates that ROS generation by mitochondrial complex III is required for initiation of the adipogenic program in MSCs [21, 22], and we confirmed that primary mouse MSCs undergo a burst of ROS generation following exposure to adipogenic stimuli but that this response is absent following p53 inactivation. Lack of ROS generation may also contribute to reduced PPARG activity based on evidence that this protein is activated by products of lipid peroxidation [32, 33]. PPARG also reportedly binds directly to an NF-kB site in the p53 promoter and PPARG agonists enhance promoter recruitment [26]. Together, these data indicate the existence of a feed forward mechanism, whereby PPARG induction by lipid oxidation byproducts stimulates p53 transcription, which in turn promotes continued mitochondrial ROS generation and lipid oxidation, thereby driving adipogenesis. Inactivation of p53 interrupts this circuitry by reducing intrinsic ROS levels and suppressing mitochondrial ROS generation and PPARG expression in response to adipogenic stimuli, thereby blocking the adipogenic program.

Our data also demonstrate that p53 inactivation results in reduced expression of TWIST2, which functions as a negative regulator of osteogenesis during skeletal development [34]. For example, we showed that TWIST2 silencing augments both adipogenic and osteogenic differentiation of MSCs, and ectopic expression of TWIST2 partially restored bi-potency to p53−/− MSCs. These data suggest that TWIST2 downregulation following p53 inactivation results in unconstrained cellular differentiation that, when coupled with the absence of ROS generation and reduced PPARG levels, skews cells toward an osteogenic fate. These results are consistent with a recent report showing that TWIST2 functions as a tumor suppressor in osteosarcoma [35] and our own studies showing that FGF2 blocks multilineage differentiation of mouse MSCs via a TWIST2-dependent mechanism [27]. We also found that TWIST2 silencing induced p53 expression but did not pursue experiments to determine this mechanism. However, TWIST is known to negatively regulate p53 activity by direct protein interaction via a conserved domain termed the TWIST box [36]. We also provided data indicating that TWIST2 alters the cellular redox state via a p53-dependent mechanism. These findings are consistent with a previous study showing that ectopic TWIST2 expression decreased intracellular ROS levels in human diploid fibroblasts [37]. Lastly, studies showing that FGF2-mediated induction of TWIST2 alters mitochondrial ROS generation by modulating p53 protein levels point to a novel signaling axis that may function to preserve stem cell integrity under conditions of oxidative stress.

Various transcription factors including ΔFosb, Taz, Esr1, Msx2, and Cebpβ have been reported to regulate MSC bifurcation to the adipocyte and osteoblast lineages [38–40]. We extend these findings by showing that p53 also functions in a similar manner but by a novel mechanism. Moreover, since it is well established that p53 loss-of-function has anti-aging effects [1] and p53-activating mutations cause early-onset aging-associated phenotypes in mice [41], our findings have important implications with respect to the role of MSCs in aging. For example, it is well established that MSCs in bone marrow exhibit enhanced adipogenic differentiation and reduced osteogenic potential with aging or following treatment with antidiabetic drugs such as thiazolidinediones. Although the precise mechanism responsible for this switch is unknown, skeletal involution is strongly correlated with increased oxidative stress [42]. Recently, Nishikawa et al. [43] showed a correlation between increased p53 expression due to age-associated oxidative stress and repression of Maf, a transcription factor that modulates osteoblast/adipocyte bifurcation by augmenting RUNX2 activity and inhibiting Pparg mRNA transcription. Herein, haploinsufficiency of Maf resulted in decreased osteoblast numbers, reduced bone volume, and increased marrow adiposity in adult mice. These data implicate age-induced increases in p53 expression with downregulation of Maf and increased MSC adipogenesis. While we did not explore the effect of p53 inactivation on Maf expression, our data are also consistent with the thesis that age-associated oxidative stress drives MSC adipogenesis via a p53-dependent mechanism and loss-of-function of p53 prevents these age-related changes by making cells insensitive to such stress.

Our studies also reveal that basal p53 expression also influences hematopoiesis-supporting activity of MSCs, and that p53 loss-of-function results in reduced cytokine secretion including that of KITL due to loss of p53 activity at the Kitl promoter. Studies mapping global p53-binding sites in human colorectal cancer cells also identified the Kitl promoter as a p53 target [44]. Importantly, deletion of CXCL12-expressing and KITL-expressing CAR cells or FAP+ stromal cells from bone marrow impairs hematopoiesis in vivo [18, 19], demonstrating the critical role of these proteins in hematopoiesis. Expression of CXCL12 was also markedly reduced in MSCs following p53 inactivation. Although we did not demonstrate that p53 associates with the CXCL12 promoter, this has been confirmed in a pancreatic insulinoma cell line [45]. However, our data contrast with other reports indicating that p53 suppresses expression of CXCL12 in human MSCs [46, 47].

Inactivation of p53 has been shown to impair HSC quiescence [7], and p53 hyperactivation in response to Mysm1 deletion is linked to defects in HSC differentiation [48]. Similarly, we provide evidence that basal p53 expression is necessary to maintain the stem/progenitor properties of primary MSCs. These findings indicate that dysfunctional MSC responses may contribute to the pathophysiology of p53-related diseases including osteosarcoma and Fanconi anemia. They also have important implications for the use of immortalized cell lines as surrogates to study basic MSC biology, suggesting that outcomes achieved using immortalized cell lines [16, 49, 50] should be cautiously interpreted.

Materials and methods

Cell culture

MSCs were enriched from the bone marrow of FVB/n and B6.129S2-Trp53<tm1Tyj> mice (The Jackson Laboratory) by immunodepletion as previously described [51] except that all manipulations were performed in a modular airtight chamber (BioSpherix Ltd) flushed with 5% O2 balanced with N2. Following immunodepletion, MSCs were designated as passage 1 and expanded at 37 oC in a humidified chamber in 5% CO2 and 5% O2 balanced with N2 in complete culture media (CCM; α-minimal essential media containing L-glutamine and supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 100 U/ml penicillin, and 100 U/m streptomycin). Where indicated, MSCs maintained in 5% O2 were switched to 21% O2 (atmospheric oxygen) or cultured in CCM supplemented with N-acetyl cysteine (NAC; 5 nM, Tocris Bioscience). Delivery of siRNA into MSCs was accomplished as described previously using the LipofectamineTM RNAiMAX Transfection Reagent (Invitrogen) [16]. To evaluate cell cycle, MSCs were washed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and stained with propidium iodide (5 µg/ml) for 20 min. Cell proliferation was evaluated using the MTT Cell Proliferation Assay Kit (Cayman Chemical Co.) and a synergy of two multimode microplate reader (BioTek Instrument Co.). Apoptosis was measured using the FITC Annexin V Apoptosis Kit (BD Biosciences). Fluorescent quantification of mitochondrial superoxide production was performed by staining cells with MitoSOX RedTM (5 µM, Thermo Fisher Scientific) as previously described [16]. Stained cells were analyzed using a LSR II Flow Cytometer System (Beckton Dickinson) and FlowJo software (Tree Star Inc.). Cultures were photographed using a Leica DMI3000 B upright fluorescent microscope attached to a DFC295 digital camera (Micro Optics of Florida Inc.).

To quantify CFU-Fs, MSCs (10,000 cells) were plated in 100 mm dishes and were cultured for 7–10 days with media changes every 2–3 days. On day 10 the monolayers were washed with PBS, stained with 0.5% crystal violet (Sigma-Aldrich) in 25% methanol for 10 min at room temperature, washed, and colonies ≥2 mm in size were counted. To quantify CAFC activity, confluent MSC monolayers were expanded for 7 days in 5 or 21% oxygen, charged with freshly isolated bone marrow cells (10,000 cells/cm2), and cultured an additional 10–14 days in 5 or 21% O2 as described previously [52]. Cultures were then stained with 0.5% crystal violet solution, washed with PBS, and the number of CAFCs enumerated. To perform standard colony assays for hematopoiesis, conditioned media (serum-free) was collected over a 24-h period from confluent monolayers of p53−/− and p53+/+ MSCs, filtered, and then used to suspend whole-bone marrow cells isolated from wild-type mice. The cells were then mixed with growth factor supplemented semi-solid media (Methocult) and plated in 60 mm dishes at 100,000 cells/dish. The plates were incubated 37 °C in a humidified chamber in 5% CO2 and 5% O2 balanced with N2 for 8–10 days after which colonies were enumerated based on morphology.

Cell differentiation

Unless indicated otherwise, MSCs (1000 cells/cm2) at passage 2 were maintained in 5% oxygen and their capacity for adipogenic and osteogenic differentiation was quantified as described previously [16] with the following exceptions. Adipogenic induction media (AIM) consisted of α-MEM supplemented with 10% rabbit serum, 10−8 M dexamethasone, 20 mM ETYA, and 25 mg/ml insulin. Lipid accumulation was quantified by staining the monolayer with AdipoRedTM Assay Reagent (Lonza) for 10 min and measuring fluorescence using a SpectraMax fluorescent plate reader (excitation 485 nm; emission 572 nm). Adipo-induction was normalized to cell number, which was determined by staining the monolayer with 4', 6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) or direct cell counting. Osteogenic induction media (OIM) consisted of high-glucose DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS, 50 µg/ml L-ascorbic-2-phosphate, 10 mM β-glycerolphosphate, and 10−8 M dexamethasone. Mineralization was quantified by extracting calcium from monolayers using 10% cetylpyridinium chloride and measuring absorbance at 562 nm. Osteo-induction was also normalized to cell number.

Quantitative real-time PCR

Total RNA was isolated using the RNeasy Kit (Qiagen), converted to cDNA using the qScript cDNA synthesis kit (Quantabio), and amplified by PCR using the POWER SYBR® Green PCR Master Mix (Thermo Fisher Scientific) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Primer sets used for PCR amplification are listed in Supplementary Table 1. Reactions were performed on a 7900 HT sequence detector (Applied Biosystems) and transcript levels quantified using the relative Ct method by employing Gapdh as an internal control.

Western blot

Protein lysates were prepared using the Qproteome Mammalian Protein Prep Kit (Qiagen) and protein concentrations were determined using the Pierce BCA Protein Assay Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Protein samples (20 µg) were prepared in Laemmli sample buffer (Bio-Rad) containing 5% β-mercaptoethanol, denatured at 95 °C for 10 min, electrophoresed on NuPAGE 10% Bis-Tris gels or 4–12% gradient gels using 1× NuPAGE MES SDS Running Buffer (Invitrogen), and then transferred to 0.45 µm nitrocellulose membranes in 1× NuPAGE transfer buffer containing 10% methanol. Membranes were washed with Tris-buffered saline (TBS) for 5 min, incubated in TBS with 0.1% Tween-20 (TBST) and Odyssey® blocking buffer (LI-COR Biosciences) overnight at 4 °C, washed an additional 3× in TBST, and then incubated with anti-p53 (1:1000) or anti-PPARG (1:500) antibodies (Cell Signaling company) or anti-TWIST2 (1:500), anti-BAX (1:1000), or anti-GAPDH (1:1000; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) antibodies in Odyssey® blocking buffer for 2 h at room temperature with gentle agitation. Membranes were washed 5× in TBST and probed with a fluorescent-labeled secondary antibody at a 1:15,000 dilution in Odyssey® blocking buffer for 1 h. Blots were scanned using Odyssey® infrared image system (LI-COR Biosciences).

Luminex multiplex array

Confluent monolayer cultures of p53+/+ and p53−/− MSCs were maintained in serum-free media for 24 h, the conditioned media collected, and concentrated 5-fold, 10-fold, and 50-fold using Amicon Ultra-15 centrifugal filters (Millipore). Media was then analyzed using the Mouse Pre-mixed Analyte Kit (R&D Systems) for simultaneous detection of the indicated analytes. Quantification of analyte abundance was performed using a Luminex 200 dual-laser, flow-based detection platform (Luminex).

Chromatin immunoprecipitation

MSCs were treated with 20 µM Nutlin-3a (Millipore) for 24 h prior to fixing. ChIP was performed according to the manufacturer’s protocol using the ChIP-IT™ Express kit (Active Motif). Fixed chromatin was concentrated into two volumes (350 µl) of shearing buffer, sonicated using a sonicator with a 1/8″ probe (Qsonica) on ice for five pulses of 20 s at 25% power at 30 s intervals. Immunoprecipitation reactions (200 µl) were performed overnight on chromatin samples (15 µg) using the following antibodies (3 µg): mouse anti-RNA pol II IgG1 (Active Motif), mouse (G3A1) IgG1 isotype control, and mouse anti-p53 (1C12) mAB (Cell Signaling Technology). A bridging antibody (3 µg, Active Motif) was used to enhance binding of the anti-Pol II and anti-p53 antibodies to protein G magnetic beads. End point qPCR on precipitated and eluted chromatin was performed using Power SYBR Green qPCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems) and the following primers (IDT): Kitlg, 5′-atgtgacagttaatgctggctact-3′ and 5′-atttgtgctggcctttaatcttca-3′; Pparg, 5′-aaacagaaggtttggaggtgctt-3′ and 5′-tggctgctgtgctttgtgc-3′; Twist2, 5′-ggttggagctcagcacaactcaagg-3′ and 5′-tgcagagcggtctgccctgg-3′.

Statistical analysis

Significance was estimated by unpaired Student’s t-test in experiments where comparison between two groups was warranted. Alternatively, significance was determined by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and post hoc Tukey tests. Cell cycle data were fit using the Watson pragmatic model. Differences between treatment groups were considered significant with a p value ≤ 0.05.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health to DGP (R24 OD018254).

Authors' contributions

S.V.B., V.K., and D.G.P. designed the study. S.V.B., V.K., J.S., C.L.H., and C.N.B. performed laboratory experiments and collected data. S.V.B., V.K., and D.G.P. performed statistical analyses. D.G.P. wrote the manuscript. All authors edited and approved the manuscript.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing financial interests.

Footnotes

Edited by Y. Shi

Siddaraju V. Boregowda and Veena Krishnappa contributed equally to this study.

A comment to this article is available online at https://doi.org/10.1038/s41418-018-0062-2.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1038/s41418-017-0004-4) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

References

- 1.Olivier M, Hollstein M, Hainaut P. TP53 mutations in human cancers: origins, consequences, and clinical use. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2010;2:a001008. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a001008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fuchs B, Pritchard DJ. Etiology of osteosarcoma. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2002;397:40–52. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200204000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Birch JM, Blair V, Kelsey AM, Evans DG, Harris M, Tricker KJ, et al. Cancer phenotype correlates with constitutional TP53 genotype in families with the Li-Fraumeni syndrome. Oncogene. 1998;17:1061–8. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pant V, Quintas-Cardama A, Lozano G. The p53 pathway in hematopoiesis: lessons from mouse models, implications for humans. Blood. 2012;120:5118–27. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-05-356014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hafsi H, Hainaut P. Redox control and interplay between p53 isoforms: roles in the regulation of basal p53 levels, cell fate, and senescence. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2011;15:1655–67. doi: 10.1089/ars.2010.3771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Asai T, Liu Y, Bae N, Nimer SD. The p53 tumor suppressor protein regulates hematopoietic stem cell fate. J Cell Physiol. 2011;226:2215–21. doi: 10.1002/jcp.22561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liu Y, Elf SE, Miyata Y, Sashida G, Liu Y, Huang G, et al. p53 regulates hematopoietic stem cell quiescence. Cell Stem Cell. 2009;4:37–48. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Urao N, Ushio-Fukai M. Redox regulation of stem/progenitor cells and bone marrow niche. Free Radic Biol Med. 2013;54:26–39. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2012.10.532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Signer RA, Morrison SJ. Mechanisms that regulate stem cell aging and life span. Cell Stem Cell. 2013;12:152–65. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2013.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang H, Lu W, Zhao Y, Rong P, Cao R, Gu W, et al. Adipocytes derived from human bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells exert inhibitory effects on osteoblastogenesis. Curr Mol Med. 2011;11:489–502. doi: 10.2174/156652411796268704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sadie-Van Gijsen H, Crowther NJ, Hough FS, Ferris WF. The interrelationship between bone and fat: from cellular see-saw to endocrine reciprocity. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2013;70:2331–49. doi: 10.1007/s00018-012-1211-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Devlin MJ, Rosen CJ. The bone-fat interface: basic and clinical implications of marrow adiposity. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2015;3:141–7. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(14)70007-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhou BO, Yue R, Murphy MM, Peyer JG, Morrison SJ. Leptin-receptor-expressing mesenchymal stromal cells represent the main source of bone formed by adult bone marrow. Cell Stem Cell. 2014;15:154–68. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2014.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim M, Kim C, Choi YS, Kim M, Park C, Suh Y. Age-related alterations in mesenchymal stem cells related to shift in differentiation from osteogenic to adipogenic potential: implication to age-associated bone diseases and defects. Mech Ageing Dev. 2012;133:215–25. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2012.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Atashi F, Modarressi A, Pepper MS. The role of reactive oxygen species in mesenchymal stem cell adipogenic and osteogenic differentiation: a review. Stem Cells Dev. 2015;24:1150–63. doi: 10.1089/scd.2014.0484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Boregowda SV, Krishnappa V, Chambers JW, Lograsso PV, Lai WT, Ortiz LA, et al. Atmospheric oxygen inhibits growth and differentiation of marrow-derived mouse mesenchymal stem cells via a p53-dependent mechanism: implications for long-term culture expansion. Stem Cells. 2012;30:975–87. doi: 10.1002/stem.1069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ding L, Saunders TL, Enikolopov G, Morrison SJ. Endothelial and perivascular cells maintain haematopoietic stem cells. Nature. 2012;481:457–62. doi: 10.1038/nature10783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Omatsu Y, Sugiyama T, Kohara H, Kondoh G, Fujii N, Kohno K, et al. The essential functions of adipo-osteogenic progenitors as the hematopoietic stem and progenitor cell niche. Immunity. 2010;33:387–99. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Roberts EW, Deonarine A, Jones JO, Denton AE, Feig C, Lyons SK, et al. Depletion of stromal cells expressing fibroblast activation protein-alpha from skeletal muscle and bone marrow results in cachexia and anemia. J Expt Med. 2013;210:1137–51. doi: 10.1084/jem.20122344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang B, Xiao Z, Ren EC. Redefining the p53 response element. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:14373–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0903284106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tormos KV, Anso E, Hamanaka RB, Eisenbart J, Joseph J, Kalyanaraman B, et al. Mitochondrial complex III ROS regulate adipocyte differentiation. Cell Metab. 2011;14:537–44. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2011.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Higuchi M, Dusting GJ, Peshavariya H, Jiang F, Hsiao ST, Chan EC, et al. Differentiation of human adipose-derived stem cells into fat involves reactive oxygen species and Forkhead box O1 mediated upregulation of antioxidant enzymes. Stem Cells Dev. 2013;22:878–88. doi: 10.1089/scd.2012.0306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Marciano DP, Kuruvilla DS, Boregowda SV, Asteian A, Hughes TS, Garcia-Ordonez R, et al. Pharmacological repression of PPARgamma promotes osteogenesis. Nat Commun. 2015;6:7443. doi: 10.1038/ncomms8443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Grey A, Bolland M, Gamble G, Wattie D, Horne A, Davidson J, et al. The peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma agonist rosiglitazone decreases bone formation and bone mineral density in healthy postmenopausal women: a randomized, controlled trial. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92:1305–10. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-2646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Soroceanu MA, Miao D, Bai XY, Su H, Goltzman D, Karaplis AC. Rosiglitazone impacts negatively on bone by promoting osteoblast/osteocyte apoptosis. J Endocrinol. 2004;183:203–16. doi: 10.1677/joe.1.05723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bonofiglio D, Aquila S, Catalano S, Gabriele S, Belmonte M, Middea E, et al. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma activates p53 gene promoter binding to the nuclear factor-kappaB sequence in human MCF7 breast cancer cells. Mol Endocrinol. 2006;20:3083–92. doi: 10.1210/me.2006-0192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lai WT, Krishnappa V, Phinney DG. Fibroblast growth factor 2 (Fgf2) inhibits differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells by inducing Twist2 and Spry4, blocking extracellular regulated kinase activation, and altering Fgf receptor expression levels. Stem Cells. 2011;29:1102–11. doi: 10.1002/stem.661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tataria M, Quarto N, Longaker MT, Sylvester KG. Absence of the p53 tumor suppressor gene promotes osteogenesis in mesenchymal stem cells. J Pediatr Surg. 2006;41:624–32. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2005.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.He Y, de Castro LF, Shin MH, Dubois W, Yang HH, Jiang S, et al. p53 loss increases the osteogenic differentiation of bone marrow stromal cells. Stem Cells. 2015;33:1304–19. doi: 10.1002/stem.1925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Armesilla-Diaz A, Elvira G, Silva A. p53 regulates the proliferation, differentiation and spontaneous transformation of mesenchymal stem cells. Expt Cell Res. 2009;315:3598–610. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2009.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang X, Kua HY, Hu Y, Guo K, Zeng Q, Wu Q, et al. p53 functions as a negative regulator of osteoblastogenesis, osteoblast-dependent osteoclastogenesis, and bone remodeling. J Cell Biol. 2006;172:115–25. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200507106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schild RL, Schaiff WT, Carlson MG, Cronbach EJ, Nelson DM, Sadovsky Y. The activity of PPAR gamma in primary human trophoblasts is enhanced by oxidized lipids. J Clin Endorcrinol Metab. 2002;87:1105–10. doi: 10.1210/jcem.87.3.8284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nagy L, Tontonoz P, Alvarez JG, Chen H, Evans RM. Oxidized LDL regulates macrophage gene expression through ligand activation of PPARgamma. Cell. 1998;93:229–40. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81574-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bialek P, Kern B, Yang X, Schrock M, Sosic D, Hong N, et al. A twist code determines the onset of osteoblast differentiation. Dev Cell. 2004;6:423–35. doi: 10.1016/S1534-5807(04)00058-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ishikawa T, Shimizu T, Ueki A, Yamaguchi SI, Onishi N, Sugihara E, et al. Twist2 functions as a tumor suppressor in murine osteosarcoma cells. Cancer Sci. 2013;104:880–8. doi: 10.1111/cas.12163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Piccinin S, Tonin E, Sessa S, Demontis S, Rossi S, Pecciarini L, et al. A "twist box" code of p53 inactivation: twist box: p53 interaction promotes p53 degradation. Cancer Cell. 2012;22:404–15. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Floc'h N, Kolodziejski J, Akkari L, Simonin Y, Ansieau S, Puisieux A, et al. Modulation of oxidative stress by twist oncoproteins. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e72490. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0072490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gimble JM, Zvonic S, Floyd ZE, Kassem M, Nuttall ME. Playing with bone and fat. J Cell Biochem. 2006;98:251–66. doi: 10.1002/jcb.20777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sabatakos G, Sims NA, Chen J, Aoki K, Kelz MB, Amling M, et al. Overexpression of DeltaFosB transcription factor(s) increases bone formation and inhibits adipogenesis. Nat Med. 2000;6:985–90. doi: 10.1038/79683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hong JH, Hwang ES, McManus MT, Amsterdam A, Tian Y, Kalmukova R, et al. TAZ, a transcriptional modulator of mesenchymal stem cell differentiation. Science. 2005;309:1074–8. doi: 10.1126/science.1110955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tyner SD, Venkatachalam S, Choi J, Jones S, Ghebranious N, Igelmann H, et al. p53 mutant mice that display early ageing-associated phenotypes. Nature. 2002;415:45–53. doi: 10.1038/415045a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Almeida M, Han L, Martin-Millan M, Plotkin LI, Stewart SA, Roberson PK, et al. Skeletal involution by age-associated oxidative stress and its acceleration by loss of sex steroids. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:27285–97. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M702810200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nishikawa K, Nakashima T, Takeda S, Isogai M, Hamada M, Kimura A, et al. Maf promotes osteoblast differentiation in mice by mediating the age-related switch in mesenchymal cell differentiation. J Clin Invest. 2010;120:3455–65. doi: 10.1172/JCI42528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wei CL, Wu Q, Vega VB, Chiu KP, Ng P, Zhang T, et al. A global map of p53 transcription-factor binding sites in the human genome. Cell. 2006;124:207–19. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.10.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Markovic J, Uskokovic A, Grdovic N, Dinic S, Mihailovic M, Jovanovic JA, et al. Identification of transcription factors involved in the transcriptional regulation of the CXCL12 gene in rat pancreatic insulinoma Rin-5F cell line. Biochem Cell Biol. 2015;93:54–62. doi: 10.1139/bcb-2014-0104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kojima K, McQueen T, Chen Y, Jacamo R, Konopleva M, Shinojima N, et al. p53 activation of mesenchymal stromal cells partially abrogates microenvironment-mediated resistance to FLT3 inhibition in AML through HIF-1alpha-mediated down-regulation of CXCL12. Blood. 2011;118:4431–9. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-02-334136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lin SY, Dolfi SC, Amiri S, Li J, Budak-Alpdogan T, Lee KC, et al. P53 regulates the migration of mesenchymal stromal cells in response to the tumor microenvironment through both CXCL12-dependent and -independent mechanisms. Int J Oncol. 2013;43:1817–23. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2013.2109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Belle JI, Langlais D, Petrov JC, Pardo M, Jones RG, Gros P, et al. p53 mediates loss of hematopoietic stem cell function and lymphopenia in Mysm1 deficiency. Blood. 2015;125:2344–8. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-05-574111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Krishnappa V, Boregowda SV, Phinney DG. The peculiar biology of mouse mesenchymal stromal cells-oxygen is the key. Cytotherapy. 2013;15:536–41. doi: 10.1016/j.jcyt.2012.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Prockop DJ. A long-awaited discovery: hypoxia prevents mouse cells from undergoing spontaneous p53-dependent transformation. Cytotherapy. 2012;14:1029–31. doi: 10.3109/14653249.2012.718887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Phinney DG. Isolation of mesenchymal stem cells from murine bone marrow by immunodepletion. Methods Mol Biol. 2008;449:171–86. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60327-169-1_12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.van Os RP, Dethmers-Ausema B, de Haan G. In vitro assays for cobblestone area-forming cells, LTC-IC, and CFU-C. Methods Mol Biol. 2008;430:143–57. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-182-6_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.