Abstract

Mechanical strength and its long-term stability of bioceramic scaffolds is still a problem to treat the osteonecrosis of the femoral head. Considering the long-term stability of diopside (DIO) ceramic but poor mechanical strength, we developed the DIO-based porous bioceramic composites via dilute magnesium substituted wollastonite reinforcing and three-dimensional (3D) printing. The experimental results showed that the secondary phase (i.e. 10% magnesium substituting calcium silicate; CSM10) could readily improve the sintering property of the bioceramic composites (DIO/CSM10-x, x = 0–30) with increasing the CSM10 content from 0% to 30%, and the presence of the CSM10 also improved the biomimetic apatite mineralization ability in the pore struts of the scaffolds. Furthermore, the flexible strength (12.5–30 MPa) and compressive strength (14–37 MPa) of the 3D printed porous bioceramics remarkably increased with increasing CSM10 content, and the compressive strength of DIO/CSM10-30 showed a limited decay (from 37 MPa to 29 MPa) in the Tris buffer solution for a long time stage (8 weeks). These findings suggest that the new CSM10-reinforced diopside porous constructs possess excellent mechanical properties and can potentially be used to the clinic, especially for the treatment of osteonecrosis of the femoral head work as a bioceramic rod.

Keywords: Diopside, Dilute magnesium substituting wollastonite, Mechanical properties, Porous bioceramics, 3D printing, Osteonecrosis of the femoral head

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

10% Mg-substituted wollastonite (CSM10) may be used to reinforce the diopside (DIO) bioceramic.

-

•

DIO/CSM10 porous bioceramics may be fabricated via 3D printing and pressureless sintering.

-

•

DIO/CSM10 porous bioceramics indicate excellent mechanical strength and bioactivity.

-

•

DIO/CSM10 porous rod is potentially a good candidate to treat the osteonecrosis of femoral head.

1. Introduction

Osteonecrosis of the femoral head (ONFH) is considered as one of the important medical problems due to its unknown pathogenesis, inadequate treatment, and poor biological performance of implants. The best way to treat this degenerative disease and the complications in the early stage is to prepare the porous implants which can reserve the blood supply of the femoral head and can subsequently maintain bone remodeling, and thus to control the development of the disease [1], [2]. Although the porous tantalum rod is found partly effective to control the development, it is still a challenge to maintain the satisfied biomechanical support and to conduct bone regeneration due to its inert nature and mechanical deficiency [3], [4], [5].

It has been widely investigated that integration of osteogenic (stem) cells, growth factors or proteins with bioengineering scaffolds can promote vascularization and osteogenesis and is favorable for treatment of ONFH. For instance, basic fibroblast growth factor, rhBMP-2 and mesenchymal stromal cells were integrated into biomaterial matrixes to facilitate osteogenesis in many attempt investigations [6], [7], [8]. However, these approaches are restricted because of the high cost, complex techniques, short half-lives of angiogenic growth factors, and the potential safety problems caused by the uncontrollable release behavior of growth factors in vivo [2], [9].

On the other hand, the artificial implant materials that can provide permanent integration and the ability to stimulate the osteogenesis and vascularization are of special significance for the successful reconstruction treatment in ONFH [10]. A number of calcium phosphate (CaP) materials have historically been used for ONFH filling repair [11], [12]. However, these materials are lowly bioactive, or may retard vascularization and osteogenesis if they were implanted solely. A variety of studies and applications showed that the low bioactivity of conventional CaP implants, and difficulties in pores enlargement of sparingly soluble CaP constructs have raised some concerns and resulted in limited use in many bone reconstruction situations [13], [14]. In fact, the ideal biomaterials for porous constructs should have the capability to induce rapid and adequate vascularization and osteogenesis as well as prolonged mechanical stability.

In this context, the desired features of ONFH filler should possess: 1) good integration of materials and femoral tissues to facilitate osteogenic fusion; 2) uniform interconnected pores and excellent bioactivity to promote the rapid and complete osteogenesis; 3) slow biodegradation to provide prolonged mechanical support; and 4) strong, non-brittle construct to easy to insert. Ca-silicate ceramics have developed as promising biomaterials for hard tissue regeneration [15]. It has reported that the wollastonite ceramic can not only stimulate osteogenic cell differentiation, but also be able to enhance proangiogenesis of endothelial cells (ECs) [16]. Diba et al. have systematically reviewed that biological performance of the Mg-containing Ca-silicate (CSM) bioceramics such as diopside (CaMgSi2O6) [17]. Some studies have confirmed that diopside is bioactive, but very stable in vitro and in vivo [18], [19]. Our previous studies have demonstrated that the dilute Mg substituted wollastonite (porous) ceramics have the exceptional sintering properties and outstanding mechanical performances and, at the same time, to stimulate osteogenesis in vivo [20], [21], [22], [23]. Thus, it could be hypothesized that diopside is a good choice for the porous substrate but the CSM may act as multifunctional additive to enhance the mechanical and biological performances of the diopside-based bioceramics.

Three-dimensional (3D) printing is an advanced additive manufacturing technique which facilitates in building up complex constructs with periodic macropores and adjustable geometrical parameters [24]. A fully interconnected macroporous structure can mimic the external cell matrix (ECM) properties (e.g., mechanical support, cellular activity and protein production through biochemical and mechanical interactions), and provide a template for cell attachment and stimulate new bone tissue formation in vivo [25]. Therefore, we demonstrated herein the new diopside-based porous bioceramics that were endowed with fully interconnected macropores, adequate open porosity (>50%) and pore size (∼300 μm), and high-bioactivity pore wall favorable for rapid osteogenesis. The diopside-based scaffolds were fabricated by ceramic ink writing assembly, and CSM was added to reinforce its mechanical and biological properties. It is reasonable to consider that such new bioactive porous constructs, independent of conventional growth factors, are potentially perfect for enhancing the treatment of ONFH.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Preparation of powders

The wollastonite powders with 10% Mg-substituting-Ca (denoted as CSM10) were synthesized by a conventional wet-chemical co-precipitation method as described previously [20]. The as-calcined CSM10 powders were ground to the particle size of 600–1500 nm. The diopside powders were synthesized by a wet-chemical co-precipitation method and were also ground for 6 h.

2.2. Preparation of scaffolds

The powder composites of the diopside and CSM10 with different CSM10 contents (x%) from 0 to 30 wt% were mechanically mixed by ball milling in ethanol for 30 min, and then dried at 90 °C overnight. Then the paste of the powders for layer-by-layer printing of the porous scaffolds was prepared by mixing 4.5 g of powders with 4.0 g of 6.0% polyvinyl alcohol (PVA, Sigma-Aldrich) solution. Thus, the scaffolds with 0°/90° strut structure were prepared by using our home-made 3D printing equipment [21]. After that, the samples were dried at 80 °C overnight, and then heat to 1150 °C for 3 h with the heating rate of 3 °C/min. The pore size of the sintered scaffolds (denoted as DIO/CSM10-x; x = 0, 10, 20, 30) were ∼320 μm.

2.3. Microstructure characterization

In order to investigate the size distribution of particles, dynamic light scattering (DLS, Malven Instrument 2000) was used. The scaffolds were verified by X-ray diffractometer (XRD; Rigaku D/max-rA) using CuKα radiation (λ = 1.5406 Å) at 40 kV/40 mA. Data were collected with a step of 0.02°/2θ and a dwell time of 1.5 s to identify crystalline phase of the scaffolds. The scaffold morphology and pore structure were observed by scanning electron microscopy (SEM; JEM-6700F). The μCT analysis (SkyScan), a powerful investigative and non-destructive testing method, was employed to characterize the pores interconnectivity, and 2D and 3D constructs of the sintered scaffolds. The porosity of the bioceramic scaffolds (n = 4) was measured using the Archimedes method in distilled water.

2.4. In vitro bioactivity assessment in SBF

The four groups of DIO/CSM10-x (x = 0, 10, 20, 30) samples (7 × 7 × 7 mm; n = 4) were immersed in SBF with a ratio of 1.0 g of scaffold to 200 mL of SBF at 37 °C and the formation of CHA was monitored on the scaffolds. After soaking for 1, 4, 7, 10, and 14 d, 1.0 mL of supernatant was extracted for inductively coupled plasma-optical emission spectrometry (ICP-OES; Thermo) measurement. An equal volume of fresh buffer was added, and the solution was refreshed every 3 d. After 14 d, the scaffolds were washed with absolute ethanol and observed by SEM.

2.5. Degradation and mechanical stability evaluation of the scaffolds in vitro

For evaluation of degradation, the DIO/CSM10-x scaffolds (n = 16; 7 × 7 × 7 mm) were weighed (W0) and immersed in 37 °C Tris buffer with an initial pH 7.4 for 2, 4, and 8 weeks, respectively, and a ratio of 1.0 g of scaffold to 200 mL of buffer was used. After the pre-set time stage, the scaffolds were rinsed with absolute ethanol and then dried at 110 °C for 12 h, and weighed (Wt). The change in weight was expressed as Wt/W0 × 100%. The mechanical strength of the as-dried scaffolds was also determined by Instron testing machine. The porosity of the bioceramic scaffolds (n = 4) was also measured using the Archimedes method in distilled water at each time point.

2.6. Statistical analysis

The results were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (mean ± SD). Statistical analysis was carried out using one-way ANOVA, and a p-value of less than 0.05 (p < 0.05) was considered statistically significant.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Primary characterization of the bioceramic powders and scaffolds

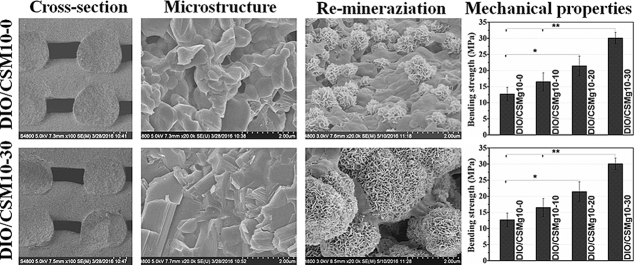

A series of CSM10-reinforced diopside porous scaffolds were prepared with adding CSM10 of 0%, 10%, 20%, and 30% in mass percent. Fig. 1A shows the XRD patterns of the bioceramic scaffolds for four of the compositions in this series. With increasing CSM10% ratio from 10% to 30%, the secondary phase of wollastonite (CaSiO3; PDF# 27-0088) became clearly detectable, suggesting an evolution in composition from mono- to bi-phasic hybrids, and indicated the fact that the intensity of peaks for diopside decreases significantly.

Fig. 1.

XRD patterns of the DIO/CSM10-x scaffolds after sintering (A) and the 2D, 3D reconstructed structure by μCT (B–E).

Direct ceramic ink writing is one of 3D printing technologies that offers unparalleled flexibility in achieving controlled composition, geometric shape, and complexity over traditional manufacturing methods [26], [27]. Although the bioactive ceramic scaffolds consisting of irregular pores were evaluated as bone implants [28], the poor pore interconnectivity cannot meet the demands of the practical applications via conventional sacrificial template (porogen) sintering method. In contrast, introduction of inkjet printing of porous diopside-based bioceramics must be necessary for giving an assurance of their self-reinforcement, because the binder-assisted printing has significant issues about strut densification due to high binder in ink.

In order to confirm the interconnected pore architecture of the 3D printed biphasic bioceramic constructs, the internal 2D and 3D visualizations of the representative DIO/CSM10-30 scaffold was characterized by μCT determination. As shown in Fig. 1B–E, the bioceramic scaffolds had a uniform porous structure with well regular pore morphology. The constructs retained their shape with no noticeable deformation of the filaments after sintering. There were no closed pores present in the internal porous network. This result suggests that the CSM10-reinforced diopside scaffolds possess fully interconnected macroporous structures, which would be potentially favorable for fibrovascularization and osteogenesis in bone defect.

3.2. Microstructure characterization of bioceramic scaffolds

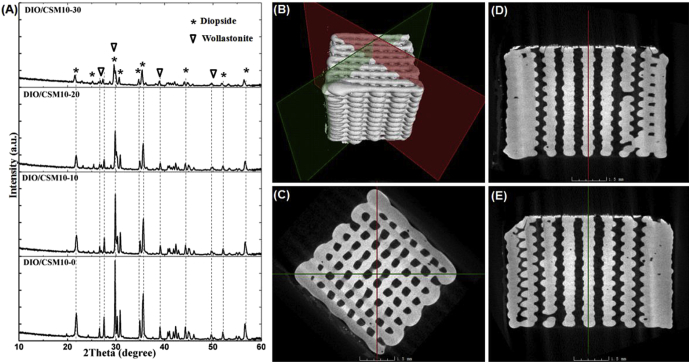

The bioceramic scaffolds with filament distance of ∼350 μm were patterned by extruded the DIO/CSM10-x inks through 400-μm nozzle. According to the quantitative analyses for the scaffold structure parameters, it was displayed that the strut thickness (330–355 μm), pore size (310–330 μm), and porosity (50%–56%) slightly decreased while increasing CSM10% ratio (0–30%). Fig. 2 indicated the different degree of linear shrinkage of the scaffolds after sintering in the three orientations with increasing the CSM10 content. These quantitative analyses suggest that, the more is the CSM10% ratio, the higher is the linear shrinkage of the bioceramic scaffolds during the sintering process. Generally, depending on the initial green body density, this is typically associated with high and anisotropic shrinkage for the 3D printed scaffolds [24], [29].

Fig. 2.

Linear (length, width, height) shrinkage of the four different scaffolds after sintering. *p < 0.05.

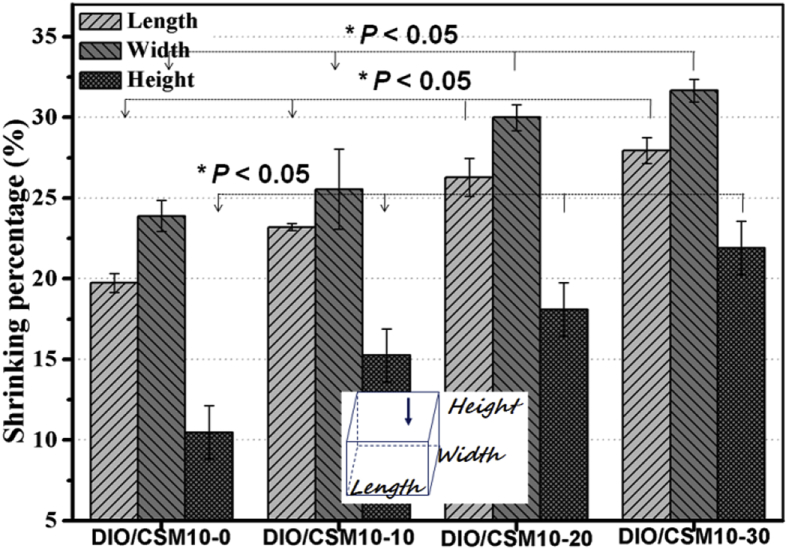

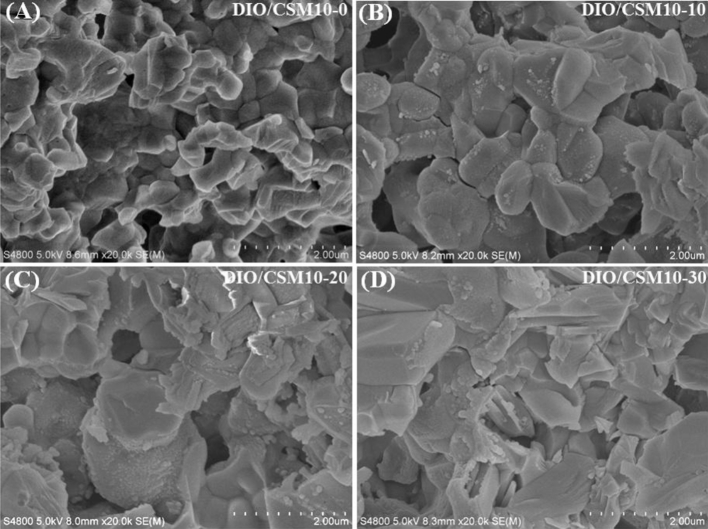

Fig. 3 shows the microstructure in the fracture surface of the DIO/CSM10-x scaffolds. It should be mentioned that there were no significant changes in the microstructure along the length of the bioceramic ink filaments. So each fracture surface was, in general, representative of the whole construct. It indicated a transgranular type of fracture for the DIO/CSM10-x (x = 0, 10, 20), but both transgranular and intergranular types of fracture can be observed for the DIO/CSM10-30. The SEM micrographs of these DIO/CSM10-30 ceramic particles in pore struts show softening while beginning to bond to each other, and thus the closed pores were also hardly noticeable, which is thought to contribute the increased mechanical strength. However, it is noticed that all of the porous DIO/CSM10-x (x = 0, 10, 20) maintained shape of particles and here the pores were the connective open pores, which would be potentially disadvantageous for scaffold's strength.

Fig. 3.

Fracture microstructure (SEM images) of the DIO/CSM10-x scaffolds after sintering.

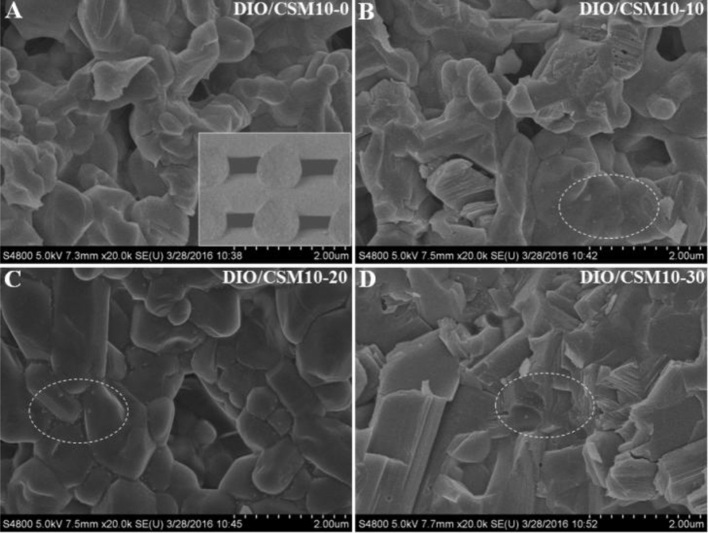

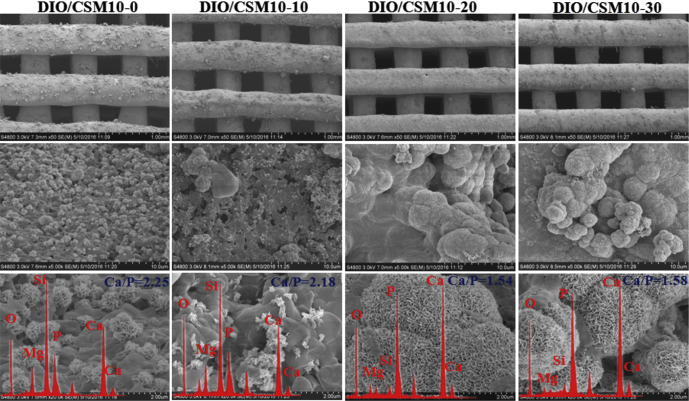

3.3. CHA formation ability on the bioceramic scaffolds

To further determine the suitability of the DIO/CSM10-x bioceramic scaffolds for the application in bone repair, their surface reactivity was tested by immersing SBF for 14 d. Fig. 4 shows SEM micrographs of the scaffolds after immersion in SBF for 14 d. It was occasionally observed that some globular structures precipitate on the surface of the DIO/CSM10-x scaffolds containing ≤10% CSM10, which might be identified as the first Ca-phosphate nuclei. However, the surface of the DIO/CSM10-20 and DIO/CSM10-30 scaffolds was completely covered by a continuous coating layer with the typical carbonated hydroxyapatite (CHA) morphology after immersion in SBF. EDX spectra (Fig. 4, inset) for the DIO/CSM10-20 and DIO/CSM10-30 showed that the chemical composition of the surface layer slightly differed in Ca/P ratio after 14 d of immersion in SBF, and the Ca/P ratio (∼1.54–1.58) was similar to that in calcium-deficient CHA [30]. The formation of biomimetic CHA has been reported to be responsible for the strong bonding between bioceramics and host bone tissue [31]. The fast deposition of apatite layer is usually considered an indication of good bioactivity in vitro. These results suggest the addition of CSM10 is beneficial for the bioactive behavior of diopside bioceramic scaffolds.

Fig. 4.

SEM images of the pore struts in the DIO/CSM10-x scaffolds after soaking in SBF for 14 days.

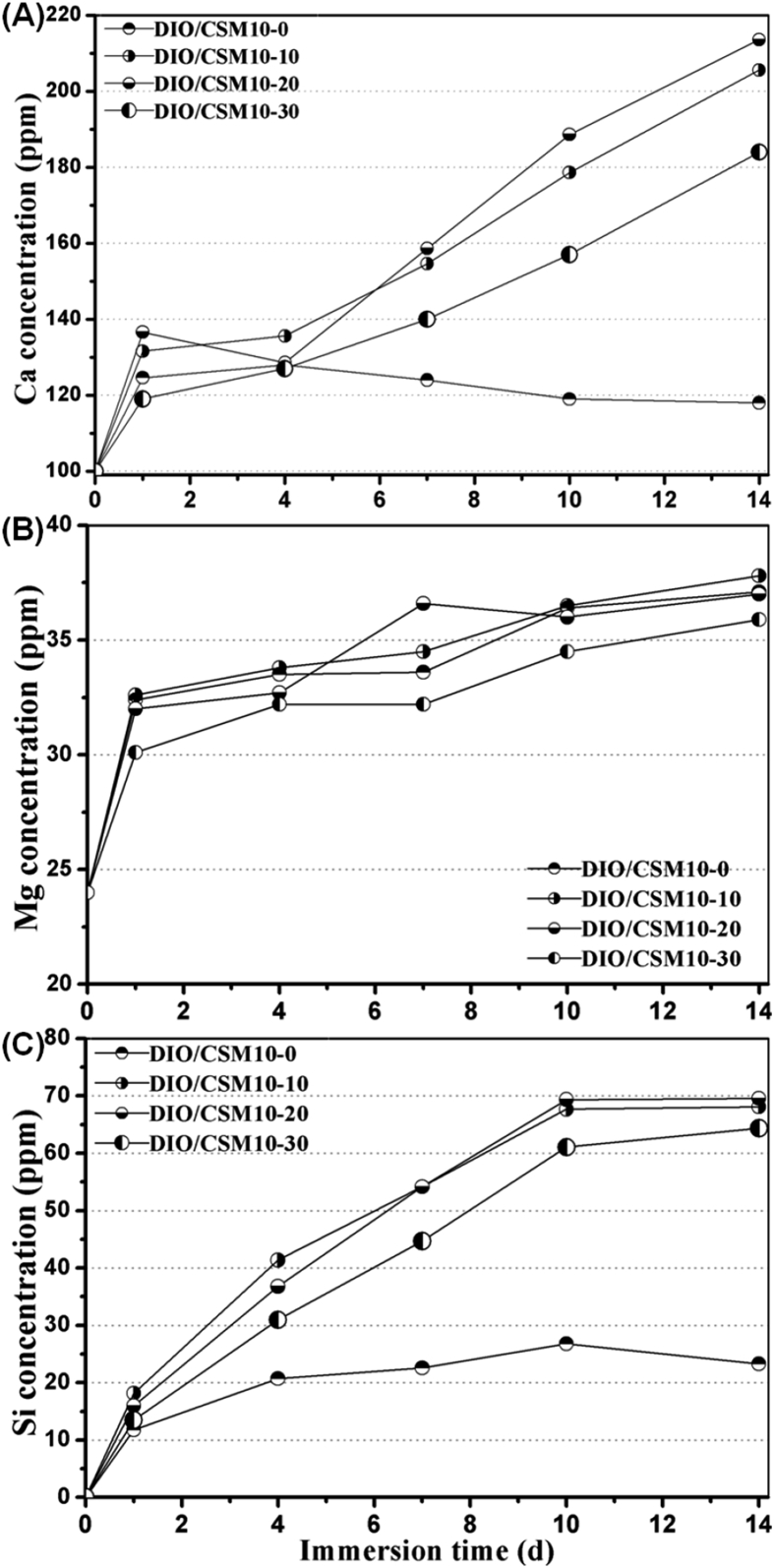

Fig. 5 shows the changes in ion concentrations in SBF during immersing the porous samples. The Mg concentration was increased with immersion time, while the Ca and Si concentration increased quickly for the composite scaffolds but then slowly varied for the pure diopside scaffolds. In general, the formation of biomimetic CHA layer in (simulated) body fluid has been reported to be responsible for an indication of good bioactivity in vitro [32]. The bioceramic dissolution leads to a significant decrease in weight but new apatite layer resulted in mechanical stability. This performance parameter is favorable for bone tissue regeneration in the early stage. In this regard, it is reasonable to consider that a biomimetic CHA layer can readily deposit on the surface of the pore struts in such composite scaffolds when immersing in SBF.

Fig. 5.

Changes in Ca, Mg and Si concentration in SBF during soaking the DIO/CSM10-x scaffolds for 1–14 days.

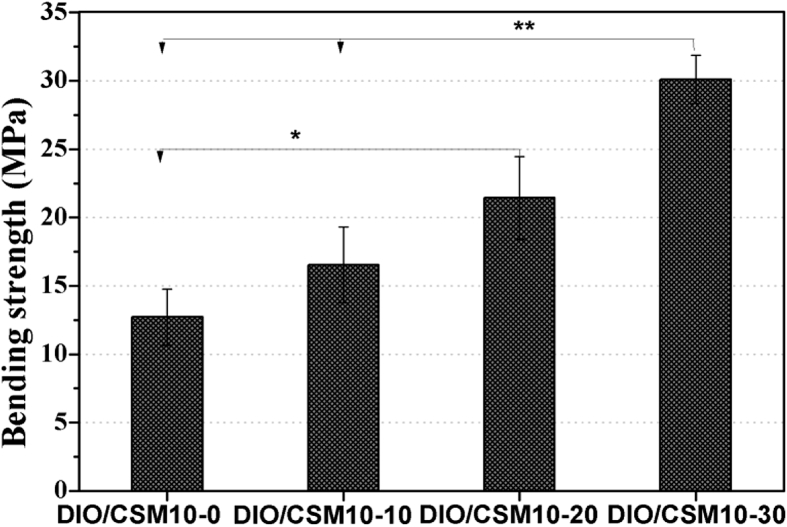

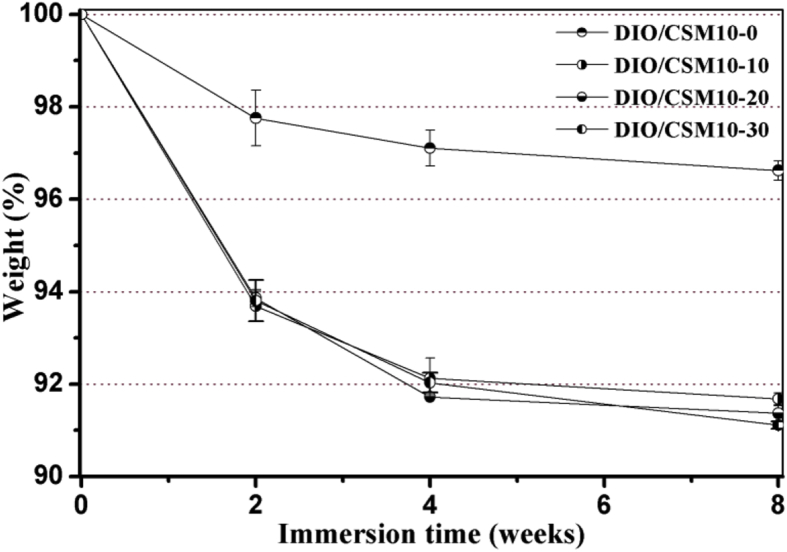

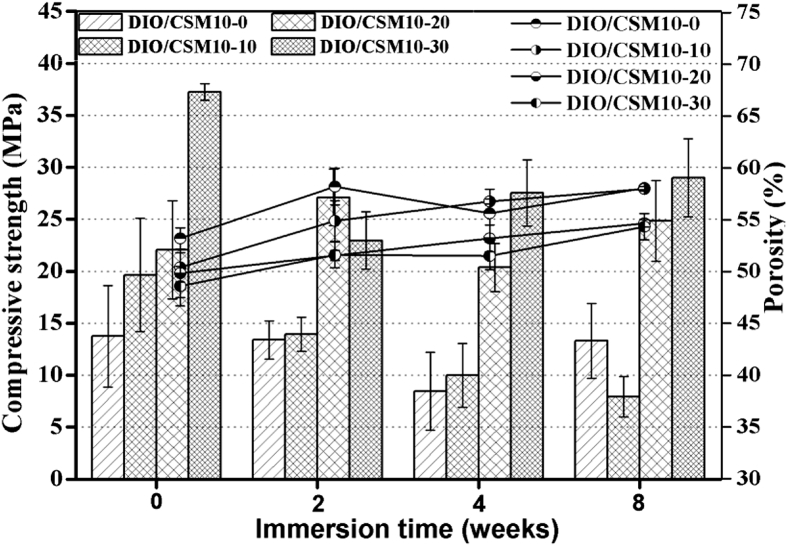

3.4. Mechanical properties and degradation behavior in vitro

Biodegradable scaffolds provide the initial structure and stability for tissue formation, but degrade as the tissue forms, providing room for matrix deposition and tissue growth [33]. To further understand the decay in strength and especially the influence of CSM10 content on that, the DIO/CSM10-x scaffolds were kept in Tris buffer up to 8 weeks. The DIO/CSM10-30 scaffolds were underwent one-step sintering treatment with the highest initial bending strength (∼30 MPa), while the DIO/CSM10-x (x = 0, 10) scaffolds with low initial strength (12–16 MPa) were sintered with the same sintering schedule (Fig. 6). On the other hand, the compressive strength and weight of bioceramic scaffolds are affected by two different mechanisms: (i) the degradation or dissolution effect lead to the loss of strength because of the increase in porosity and weakened grain boundaries, and (ii) apatite formation which fills the pores and increases the density and strength of the material. Therefore, the final weight and strength will depend on which one of these mechanisms is the dominant one. Fig. 7, Fig. 8 shows the changes in weight and compressive strength as a function of immersion time. The weight of all DIO/CSM10-x (x = 10–30) scaffolds reduced to 91–92% within the initial 8 weeks, but the pure diopside (i.e. DIO/CSM10-0) scaffolds changed little and remained up to 97% after 8 weeks. However, in comparison with the DIO/CSM10-0 scaffolds, the strength decay of the DIO/CSM10-30 was limited, from ∼37 MPa at 0 week to ∼29 MPa at 8 weeks. As has been mentioned above, the slight diopside biodissolution leads to a very limited decrease in weight but new HA mineralization results in weight and mechanical stability for the composite scaffolds. These two performances are favorable for bone tissue regeneration in the early stage, and in turn the new bone ingrowth offers the added benefits of structural stability and mechanical reliability for bone defect repair [34].

Fig. 6.

Bending strength of the DIO/CSM10-x scaffold samples.

Fig. 7.

Changes in weight of the DIO/CSM10-x scaffolds after immersion in Tris buffers for different time periods.

Fig. 8.

Changes in compressive strength and porosity of the DIO/CSM10-x scaffolds after immersion in Tris buffer for different time periods.

Fig. 9 shows the fracture microstructure of the immersed samples in the Tris buffer after 8 weeks. It is seen that the DIO/CSM10-30 maintained denser structure in the pore struts possibly due to the higher initial densification. In contrast, the DIO/CSM10-x (x = 0, 10, 20) scaffolds produced loose and porous structure in the pore struts, probably due to the dissolution of the CSM phase and their low densification nature. Thus, the high initial densification could be thought to be favorable for reinforce the mechanical stability during immersion in aqueous medium.

Fig. 9.

SEM images of the fracture surface in the pore struts in the DIO/CSM10-x scaffolds after immersion in Tris buffer for 8 weeks.

4. Conclusions

In summary, this investigation is demonstrated that a dilute Mg substituted wollastonite (i.e. CSM10) reinforcing approach can be used to modulate the mechanical and biological properties of the diopside-based porous bioceramic by the 3D printing manufacture and conventional pressureless sintering technique. In vitro SBF immersion experiments revealed that the appropriate amount (e.g. 30%) of CSM10 addition showed appreciable apatite formation ability superior to pure diopside and the highly bioactive CSM10 reinforcement substantially contributed to the structural and strength reliability in such biomimetic aqueous medium, which is particularly beneficial for enhancing osteogenic cell activity and bone regeneration. We believe this approach presents a promising strategy for developing biodegradation-retarding, high-strength bioceramic scaffolds, indicating substantial promise of bone defect repair applications—for example, in in situ load-bearing bone regeneration and repair in ONFH condition.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Zhejiang Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (LZ14E020001, LQ14H060003), gs2:National Science Foundation of China (51372218, 81271956, 81301326), and the Science and Technology Department of Zhejiang Province Foundation (2015C33119, 2014C33202).

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of KeAi Communications Co., Ltd.

Contributor Information

Sanzhong Xu, Email: wyhxsz@aliyun.com.

Zhongru Gou, Email: zhrgou@zju.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Moya-Angeler J., Gianakos A.L., Villa J.C., Ni A., Lane J.M. Current concepts on osteonecrosis of the femoral head. World J. Orthop. 2015;6:590–601. doi: 10.5312/wjo.v6.i8.590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hernigou P., Trousselier M., Roubineau F., Bouthors C., Chevallier N., Rouard H., Flouzat-Lachaniette C.H. Stem cell therapy for the treatment of hip osteonecrosis: a 30-year review of progress. Clin. Orthop. Surg. 2016;8:1–8. doi: 10.4055/cios.2016.8.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhang X.Z., Wang J., Xiao J., Shi Z.J. Early failures of porous tantalum osteonecrosis implants: a case series with retrieval analysis. Int. Orthop. 2016:1–8. doi: 10.1007/s00264-015-3087-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee G.W., Park K.S., Kim D.Y., Lee Y.M., Eshnazarow K.E., Yoon T.R. Results of total hip arthroplasty after core decompression with tantalum rod for osteonecrosis of the femoral head. Clin. Orthop. Surg. 2016;8:38–44. doi: 10.4055/cios.2016.8.1.38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liu Y.S., Yan L., Zhou S.G., Su X.Y., Cao Y.C., Wang C., Liu S.B. Tantalum rod implantation for femoral head osteonecrosis: survivorship analysis and determination of prognostic factors for total hip arthroplasty. Int. Orthop. 2016;40:1397–1407. doi: 10.1007/s00264-015-2897-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kuroda Y., Asada R., So K., Yonezawa A., Nabkaku M., Mukai K., Ito-Ihara T., Tada H., Yamamoto M., Murayama T., Morita S., Tabata Y., Yokode M., Shimizu A., Matsuda S., Haruhiko A. A pilot study of regenerative therapy using controlled release of recombinant human fibroblast growth factor for patients with pre-collapse osteonecrosis of the femoral head. Int. Orthop. 2015:1–8. doi: 10.1007/s00264-015-3083-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aoyama T., Goto K., Kakinoki R., Ikeguchi R., Uneda M., Kasai Y., Maekawa T., Tada H., Teramukai S., Nakamura T., Toguchida J. An exploratory clinical trial for idiopathic osteonecrosis of femoral head by cultured autologous multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells augmented with vascularized bone grafts. Tissue Eng. Part B. 2014;20:233–242. doi: 10.1089/ten.teb.2014.0090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang C.K., Ho M.L., Wang G.J., Chang J.K., Chen C.H., Fu Y.C., Fu H.H. Controlled-release of rhBMP-2 carriers in the regeneration of osteonecrotic bone. Biomaterials. 2009;30:4178–4186. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.04.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hong G.J., Lin N., Chen L.L., Chen X.B., He W. Association between vascular endothelial growth factor gene polymorphisms and the risk of osteonecrosis of the femoral head: systematic review. Biomed. Rep. 2016;4:92–96. doi: 10.3892/br.2015.527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 10.Mont M.A., Cherian J.J., Sierra R.J., Jones L.C., Lieberman J.R. Nontraumatic osteonecrosis of the femoral head: where do we stand Today? A ten-year update. J. Bone Jt. Surg. Am. 2015;97:1604–1627. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.O.00071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu Y.S., Liu S.B., Su X.Y. Core decompression and implantation of bone marrow mononuclear cells with porous hydroxylapatite composite filler for the treatment of osteonecrosis of the femoral head. Arch. Orthop. Trauma Surg. 2013;133:125–133. doi: 10.1007/s00402-012-1623-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kang P.D., Xie X.W., Tan Z., Yang J., Shen B., Zhou Z.K., Pei F.X. Repairing defect and preventing collapse of femoral head in a steroid-induced osteonecrotic of femoral head animal model using strontium-doped calcium polyphosphate combined BM-MNCs. J. Mater Sci. Mater Med. 2015;26:1–9. doi: 10.1007/s10856-015-5402-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu Y.S., Liu S.B., Su X.Y. Core decompression and implantation of bone marrow mononuclear cells with porous hydroxylapatite composite filler for the treatment of osteonecrosis of the femoral head. Arch. Orthop. Trauma Surg. 2013;133:125–133. doi: 10.1007/s00402-012-1623-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gauthier O., Bouler J.M., Aguado E., Pilet P., Daculsi G. Macroporous biphasic calcium phosphate ceramics: influence of macropore diameter and macroporosity percentage on bone ingrowth. Biomaterials. 1998;19:133–139. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(97)00180-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wu C.T., Chang J. A review of bioactive silicate ceramics. Biomed. Mater. 2013;8:032001–032008. doi: 10.1088/1748-6041/8/3/032001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li H.Y., Xue K., Kong N., Liu K., Chang J. Silicate bioceramics enhanced vascularization and osteogenesis through stimulating interactions between endothelia cells and bone marrow stromal cells. Biomaterials. 2014;35:3803–3818. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2014.01.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Diba M., Goudouri O.M., Tapia F., Boccaccini A.R. Magnesium-containing bioactive polycrystalline silicate-based ceramics and glass-ceramics for biomedical applications. Curr. Opin. Solid State Mater Sci. 2014;18:147–167. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nonami T., Tsutsumi S. Study of diopside ceramics for biomaterials. J. Mater Sci. Mater Med. 1999;10:475–479. doi: 10.1023/a:1008996908797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kobayashi T., Okada K., Kuroda T., Sato K. Osteogenic cell cytotoxicity and biomechanical strength of the new ceramic diopside. J. Biomed. Mater Res. 1997;37:100–107. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4636(199710)37:1<100::aid-jbm12>3.0.co;2-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xie J., Yang X., Shao H., Ye J., He Y., Fu J., Gao C., Gou Z. Simultaneous mechanical property and biodegradation improvement of wollastonite bioceramic through magnesium dilute doping. J. Mechan Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2016;54:60–71. doi: 10.1016/j.jmbbm.2015.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xie J., Shao H., He D., Yang X., Yao C., Ye J., He Y., Fu J., Gou Z. Ultrahigh strength of 3D printed diluted magnesium doping wollastonite porous scaffolds. MRS Comm. 2015;5:631–639. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shao H., He Y., Fu J., He D., Yang X., Xie J., Yao C., Ye J., Xu S., Gou Z. 3D printing magnesium-doped wollastonite/b-TCP bioceramics scaffolds with high strength and adjustable degradation. J. Euro Ceram. Soc. 2016;36:1493–1503. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu A., Sun M., Shao H., Yang X., Ma C., He D., Gao Q., Liu Y., Yan S., Xu S., He Y., Fu J., Gou Z. Outstanding mechanical response and bone regeneration capacity of robocasting dilute magnesium-doped wollastonite scaffolds in critical size bone defect. J. Mater Chem. B. 2016;4:3945–3958. doi: 10.1039/c6tb00449k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shao H., Yang X., He Y., Fu J., Liu L., Ma L., Zhang L., Yang G., Gao C., Gou Z. Bioactive glass-reinforced bioceramic ink writing scaffolds: sintering, microstructure and mechanical behavior. Biofabrication. 2015;7:035010. doi: 10.1088/1758-5090/7/3/035010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bose S., Vahabzadeh S., Bandyopadhyay A. Bone tissue engineering using 3D printing. Mater. Today. 2013;16:496–504. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gratson G.M., Xu M.J., Lewis J.A. Microperiodic structures–direct writing of three-dimensional webs. Nature. 2004;428:386–388. doi: 10.1038/428386a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Compton B.G., Levis J.A. 3D-printing of light weight cellular composite. Adv. Mater. 2014;26:5930–5935. doi: 10.1002/adma.201401804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lin K., Chang J., Liu Z., Zeng Y., Shen R.X. Fabrication and characterization of 45S5 bioglass reinforced macroporous calcium silicate bioceramics. J. Euro Ceram. Soc. 2009;29:2937–2943. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fu Q., Saiz E., Tomsia A.P. Bioinspired strong and highly porous glass scaffolds. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2011;21:1058–1063. doi: 10.1002/adfm.201002030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kokubo T., Kushitani H.F., Sakka S., Kitsugi T., Yamamuro T.J. Solutions able to reproduce in vivo surface-structure changes in bioactive glass-ceramic A-W. J. Biomed. Mater Res. 1990;24:721–734. doi: 10.1002/jbm.820240607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hench L.L., Polak J.M. Third-generation biomedical materials. Science. 2002;295:1014–1017. doi: 10.1126/science.1067404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hench L.L. Bioceramics: from concept to clinic. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 1991;74:1487–1510. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Burg K.J.L., Porter S., Kellam J.F. Biomaterial developments for bone tissue engineering. Biomaterials. 2000;21:2347–2359. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(00)00102-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Razi H., Checa S., Schaser K.D., Duda G.N. Shaping scaffold structures in rapid manufacturing implants: a modeling approach toward mechano-biologically optimized configurations for large bone defect. J. Biomed. Mater Res. B Appl. Biomater. 2012;100:1736–1745. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.32740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]