Abstract

Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE) organisms have emerged to become a major global public health threat among antimicrobial resistant bacterial human pathogens. Little is known about how CREs emerge. One characteristic phenotype of CREs is heteroresistance, which is clinically associated with treatment failure in patients given a carbapenem. Through in vitro whole-transcriptome analysis we tracked gene expression over time in two different strains (BR7, BR21) of heteroresistant KPC-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae, first exposed to a bactericidal concentration of imipenem followed by growth in drug-free medium. In both strains, the immediate response was dominated by a shift in expression of genes involved in glycolysis toward those involved in catabolic pathways. This response was followed by global dampening of transcriptional changes involving protein translation, folding and transport, and decreased expression of genes encoding critical junctures of lipopolysaccharide biosynthesis. The emerged high-level carbapenem-resistant BR21 subpopulation had a prophage (IS1) disrupting ompK36 associated with irreversible OmpK36 porin loss. On the other hand, OmpK36 loss in BR7 was reversible. The acquisition of high-level carbapenem resistance by the two heteroresistant strains was associated with distinct and shared stepwise transcriptional programs. Carbapenem heteroresistance may emerge from the most adaptive subpopulation among a population of cells undergoing a complex set of stress-adaptive responses.

1. Introduction

In 2013, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) designated carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE) as “urgent threat” pathogens [1]. In early 2017 the World Health Organization (WHO) included CREs among “Priority 1, critical” pathogens among a global priority list of antibiotic-resistant bacteria (http://www.who.int/mediacentre/news/releases/2017/bacteria-antibiotics-needed/en/). CREs are considered high-consequence antibiotic threats because infections caused by them are desperately in need of new treatments [1–3]. Among the most worrisome CREs are the Gram-negative bacilli that produce Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase (KPC), a broad-spectrum β-lactamase. KPC inactivates carbapenems as well as all other β-lactam drugs. Klebsiella pneumoniae, a common cause of infections associated with health-care settings, is the most frequently identified KPC-producer [4]. The blaKPC gene that encodes the enzyme is carried on several types of plasmids that are readily transmitted to other Gram-negative species such as Escherichia coli, one of the most important causes of community-onset infections [4, 5].

KPC-producing strains are sometimes missed by routine automated-device susceptibility tests [6–10], which are often suggested to result from heterogeneous subpopulations among these strains [7, 11–14]. Such subpopulations can adapt to changing environments [7, 15–18]. These subpopulations not only complicate their detection but also may acquire in vivo high-level resistance that leads to treatment failure and increased mortality [6, 8–10, 19–25]. Indeed, mortality associated with KPC-producing K. pneumoniae (KPC-Kp) infections in many hospitals exceeds 50% [6, 20, 23, 25]. The efficacious treatment of KPC-Kp infections remains very challenging [6, 8, 20, 23, 25, 26].

We previously showed that exposure of carbapenem-heteroresistant KPC-Kp strains to a bactericidal concentration of imipenem resulted in a reproducible, biphasic pattern of near-complete killing of the population, followed by recovery within 20 hours (h) [11]. The minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of imipenem for the recovered population increased at least fourfold compared to the MIC for the population before imipenem exposure. This high-level resistance characteristically occurred through loss of the OmpK36 porin that facilitates entry of imipenem.

Here, we undertook this study to understand how subpopulations of heteroresistant KPC-Kp survive after exposure to a bactericidal concentration of a carbapenem. We identified sequential complex stress-related transcriptional changes that these KPC-Kp strains undergo, which were associated with selection of high-level carbapenem-resistant bacterial cell populations. Furthermore, this high-level resistance appeared to involve mechanisms beyond drug inactivation by KPC-mediated hydrolysis or drug exclusion by porin modification.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Few Genetic Mutations Observed in Two Clonally Related Carbapenem-Heteroresistant Strains after Lethal Imipenem Exposure

We compared two clinical strains of KPC-Kp (BR7 and BR21) that are carbapenem-heteroresistant and carry blaKPC; they belong to multilocus sequence type ST437—members of the ST258 clonal complex most commonly distributed worldwide [27–30]. The imipenem heteroresistant behavior of both strains was previously characterized [11]. They are 99.9% similar at the genome sequence level, excluding one 70 kb prophage carried by BR21 (Tables S1 and S2). We also analyzed the whole genomes of the 2 h and 8 h imipenem-exposed samples of each strain to look for mutations associated with lethal-dose imipenem exposure (Table S2). We compared these strains because of our previous observation that OmpK36 porin synthesis differed between them [11]. While neither strain produced the porin after 8 h of lethal imipenem exposure, strain BR7 resumed production of the porin after multiple passages in drug-free media (reverting to wild-type imipenem susceptibility), while strain BR21 did not. The only major difference in the chromosomal sequences of imipenem-exposed samples compared to their unexposed counterparts was that due to low quality assembly and base-calling errors, primarily within and around mobile genetic elements. One exception was an ISI interruption found in the coding region of ompK36 in 8 h-exposed samples of BR21, but not in unexposed or 2 h-exposed samples (Table S2). The element was 100% identical to a chromosomal phage-encoded IS1 from SfIV (NCBI number NC022749) located in a P4 prophage region interrupted by genes from other phage sources (Table S1).

2.2. A Diverse Transcriptional Response Is Observed in Two Clonally Related Carbapenem-Heteroresistant Strains after Lethal Imipenem Exposure Followed by Growth in Drug-Free Medium

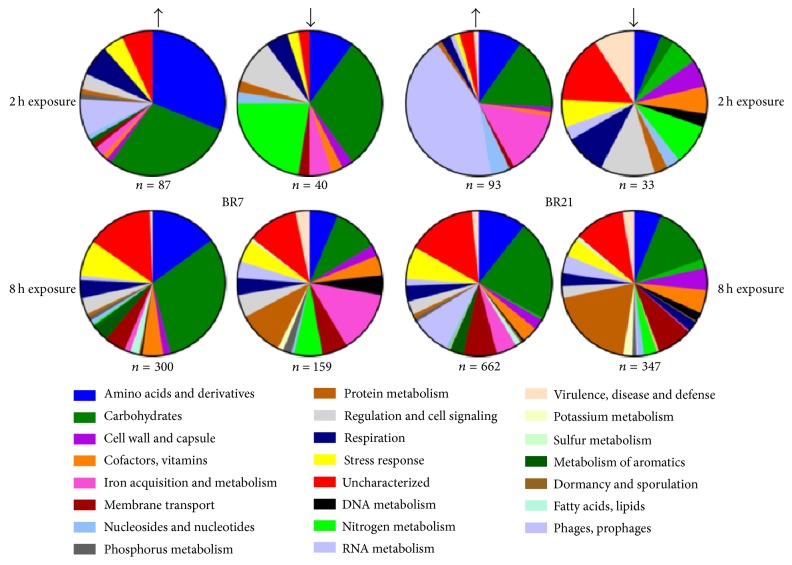

Despite their genomic and phenotypic similarity, we observed some striking transcriptome-level differences between the two strains after exposure to imipenem followed by incubation in drug-free medium. While both had relatively few differentially expressed genes after 2 h of imipenem exposure (Figure 1), BR21 had more than twice the number (1009) of differentially expressed genes compared to BR7 (459) after 8 h of exposure. Both showed strong expression of genes for carbohydrate metabolism after 2 h of exposure (Figure 1). BR7 also showed increased expression of genes involved in amino acid metabolism and transport, while BR21 showed increased expression of genes involved in iron acquisition and metabolism and in prophage genes. In general, if differential expression was observed for a shared gene in both strains, the direction (up or down) was in agreement (Table S3).

Figure 1.

Differential expression after 2 h and 8 h of lethal imipenem exposure. The proportion (%) of genes by ontological category showing increased or decreased expression (indicated by black arrows) after 2 h or 8 h of imipenem exposure for strains BR7 and BR21 (shown here with minimum threshold of 2-fold differential expression of imipenem-exposed compared to unexposed). Note that the proportion of stress-response genes is limited to those identified through initial annotation (see text for details).

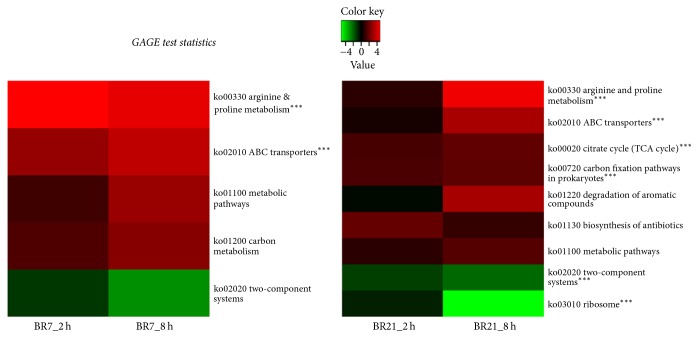

Gene Set Analysis (GSA) showed significant expression of genes in five and nine KEGG orthology (KO) pathways in BR7 and BR21, respectively (Figure 2). BR7 had only one differentially expressed plasmid-encoded gene while BR21 had 14 differentially expressed genes among its two plasmids which encoded conjugative transfer, restriction modification, DNA repair, and iron transport functions. The plasmid-mediated blaKPC gene was 100% identical in sequence in both strains and was not differentially expressed after imipenem exposure.

Figure 2.

Significantly enriched KEGG orthology (KO) pathways after 2 h and 8 h of imipenem exposure followed by growth in drug-free broth medium. Generally applicable gene-set enrichment (GAGE) analysis shows log2 fold change (FC) ratios from low (green) to high (red) expression in significantly enriched KO pathways for imipenem-exposed compared to unexposed bacterial populations (three biological replicates in each sample group). A false discovery rate q-value cutoff ≤ 0.2 was applied. ∗∗∗KO pathways with q-value of <0.1.

2.3. Lethal Imipenem Exposure Is Associated with Differential Expression of Genes Encoding Metabolic Regulatory Pathways

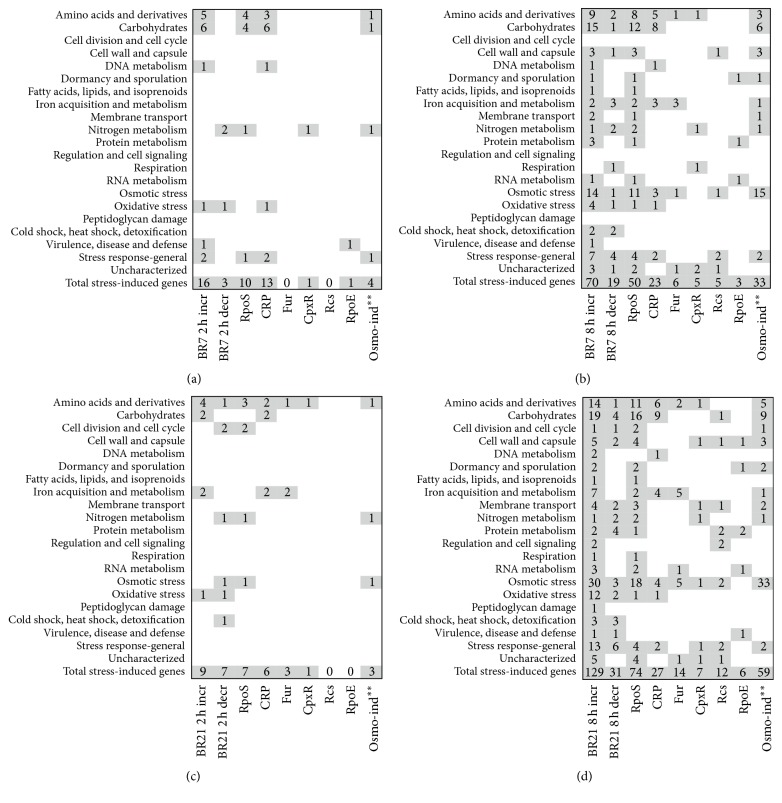

Ontological annotation categorized 77 differentially expressed genes as those involved in adaptions to osmotic and oxidative stress, membrane and cell wall damage, and general stress responses. We identified 90 additional differentially expressed genes associated with stress regulons based on a search of RegulonDB, UniProt, and the work of others (Table S4, Figure 3) [31, 34, 35, 37–58]. These genes are involved in diverse categories of amino acid, carbohydrate, and protein metabolism, as well as cell wall biosynthesis and transport. Osmotic stress-associated genes had greater than 2-fold change in expression in 33 (36%) of 89 and 59 (36%) of 160 genes associated with stress response in imipenem-exposed BR7 and BR21, respectively, compared to drug unexposed strains (Figure 3). The strongest association was observed at 8 h of imipenem exposure in both strains.

Figure 3.

Transcriptional changes associated with strong osmotic and general RpoS stress response after lethal imipenem exposure. The panels indicate the number of genes (by ontological category) associated with stress-response regulons RpoS, CRP, Fur, CpxR, Rcs, and RpoE for BR7 2 h (a), 8 h (b), BR21 2 h (c), and BR21 8 h (d). The first two columns in each panel indicate total stress-associated genes with increased (incr, column 1) or decreased (decr, column 2) expression (shown here with minimum threshold of 2-fold differential expression of imipenem-exposed compared to unexposed). Genes associated with stress regulons (in addition to those shown in Figure 1) were identified by RegulonDB, UniProt, and the experimental work of others. ∗∗Genes associated with osmotic stress were identified through the experimental work cited here [31]. Table S4 presents the data by individual differentially expressed genes.

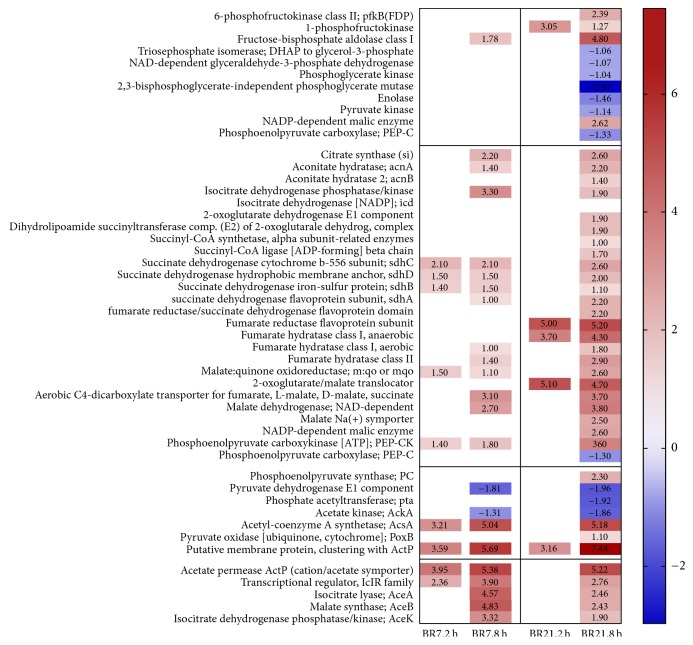

The genes encoding enzymes in glycolysis were either not differentially expressed (BR7) or were downregulated (BR21), with the exception of the earliest genes in the pathway (Figure 4). As a result, pyruvate generated from glycolysis is unlikely to serve as a primary source of acetyl-CoA needed to enter the TCA cycle. GSA indicated a significant enrichment of genes in the TCA cycle in BR21 (Figure 2, Table S3). The genes encoding the initial enzymes for the TCA cycle from citrate synthase (the formation of citrate from acetyl-CoA and oxaloacetate) and the reversible conversion of citrate to isocitrate showed increased expression in 8 h-exposed samples of both strains (Figure 4). Expression of the genes of the glyoxylate bypass cycle, catalyzed by the aceBAK operon to mediate growth on acetate or fatty acids in the absence of glucose, was strongly increased in both BR7 and BR21 [32, 33, 49, 54, 59]. The 8 h-exposed samples of both strains also had reduced expression of the genes encoding the pyruvate dehydrogenase complex (Figure 4). Increased expression of genes encoding conversion of pyruvate to acetate (pyruvate oxidase) was observed in 8 h-exposed samples of BR21. Genes encoding conversion of pyruvate to acetaldehyde (pyruvate decarboxylase) were upregulated in 8 h-exposed samples of both strains. These observations are consistent with a metabolic shift from the TCA to the glyoxylate shunt pathway [49, 59].

Figure 4.

Transcriptional changes in glycolytic pathway: upper glycolysis (section 1, lines 1–11), lower glycolysis: pyruvate and acetate (section 3, lines 38–44), the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) pathway (section 2, lines 12–37), and the glyoxylate shunt (section 4, lines 45–48) after lethal imipenem exposure. At 8 h of imipenem exposure, both BR7 and BR21 strains exhibit a similar metabolic transcriptional profile. Illustrations to guide the reader through these pathways are provided in cited research [32, 33]. Color scale shows gene expression of log2 fold change (FC) from low (blue) to high (red) expression in imipenem-exposed compared to unexposed bacterial populations (three biological replicates in each sample group). A false discovery rate p value correction (FDR) ≤ 0.05 was applied.

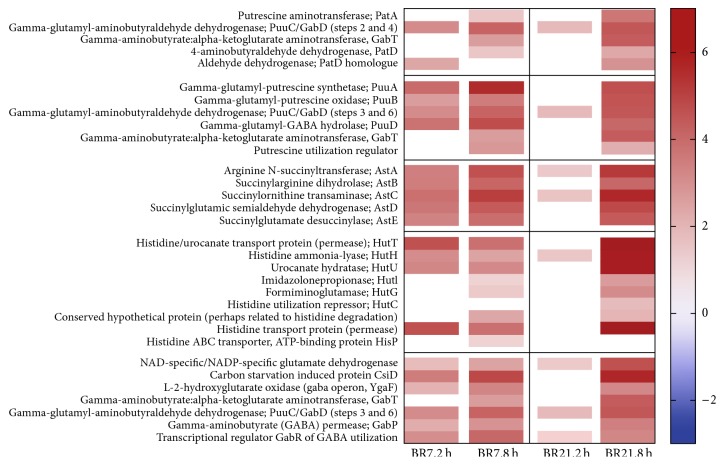

Numerous genes involved in glutamate metabolism showed strong enhanced expression after imipenem exposure (Figure 5). Glutamate is known to be a predominant source of carbon and nitrogen, especially in osmotically stressed cells [34, 35, 43, 60–62]. The genes of the ATP-binding cassette (ABC) glutamate-aspartate transporter gltIJKL had increased expression in all imipenem-exposed samples of BR7 and in 8 h-exposed samples of BR21. These findings were confirmed by GSA for both strains (Table S3). The glt-encoded glutamate synthesis genes (from α-ketoglutarate and asparagine) were not differentially expressed. Instead, we saw high-level expression of genes in four different catabolic pathways, which may result in glutamate and GABA production as by-products or end-products (Figure 5). In fact, six of the nine genes with increased expression in both strains at 2 h and 8 h of exposure were found in these pathways.

Figure 5.

Transcriptional response after lethal imipenem exposure is associated with key metabolites entering the TCA pathway via increased expression of glutamate/γ-aminobutyrate (GABA) catabolic pathways: transaminase pathway of putrescine degradation (section 1, lines 1–5), glutamylated putrescine pathway of putrescine degradation (section 2, lines 6–11), arginine degradation pathway to glutamate (section 3, lines 12–16), histidine degradation pathway to glutamate (section 4, lines 17–25), and glutamate flux to TCA, including the GABA shunt operon (section 5, lines 26–32). Illustrations to guide the reader through these pathways are provided in cited research [34–36].

We also observed increased expression in all genes of the transaminase and glutamylated putrescine catabolic pathways (Figure 5). GSA supported the findings of significant enrichment of genes in these pathways (Figure 2, Table S3). The GABA shunt, an important part of these pathways, feeds succinate and NAD(P)H formed in the putrescine degradation pathways into the TCA cycle [34, 43]. These genes belong to the well-characterized carbon starvation-induced operon, csiD-ygaF-gabDTP [31, 34, 35].

All of the genes in the arginine and histidine catabolic pathways leading to the formation of glutamate were strongly expressed (Figure 5). GSA identified significant enrichment of the genes in the arginine catabolic pathway (Figure 2, Table S3). The first gene in this pathway is reported to be RpoS-controlled [35].

GABA and glutamate are among the first compatible solutes that rapidly accumulate during osmotic stress and two of the most predominant compatible solutes in bacteria [43, 61, 62]. Glutamate also induces the uptake of other important osmoprotectants. Accordingly, we observed increased expression of genes encoding transport for the osmolytes glycine betaine and the CRP-regulated osmC, osmY, and the proline transporter, putP (Table S4).

2.4. Imipenem Exposure Is Associated with Differential Expression of Genes Involved in Outer Membrane Protein Integrity, Transport, and Processing, as well as in Global Dampening of Protein Expression

We previously reported that the observed loss of OmpK36 in 8 h-exposed samples of both BR7 and BR21 was a key factor in the conversion from relative imipenem susceptibility to high-level imipenem resistance [11]. Mutants with loss of the carbapenem-heteroresistant phenotype did not acquire high levels of imipenem resistance and did not abolish production of this porin [63]. We found no differential expression of ompK36 in 2 h-exposed B21 samples, nor in any imipenem-exposed BR7 samples (Table S3). Expression of ompK35 did not differ with imipenem exposure. In fact, ompK35 had very low expression even in unexposed samples, which agrees with our former report of its absence in SDS-PAGE analysis [11].

Small RNAs are known to control the synthesis of outer membrane porins [45, 64, 65]. We found no differential expression of micF (ompK35), micC, or rybB (ompK36). Other small noncoding RNAs have been reported to control the translation of ompC in E. coli [45, 66], but we did not identify similar sequences in our K. pneumoniae strains. However, in both strains we found significant differential expression of micA, a small RNA reported to be under the control of RpoE in response to accumulation of misfolded proteins, which decreases the stability of the ompA transcript in E. coli (Figure S1) [45].

We next examined the expression of genes involved in protein processing and export from the cytoplasm to the outer membrane. Surprisingly, while BR7 only showed increased expression of the clpA heat shock and hflc-like protease genes in 8 h-exposed samples, BR21 showed differential expression in numerous genes associated with these functions (Figure S1). These include decreased expression in 8 h-exposed samples of the sec-encoded genes, secA and secY. The Sec-dependent pathway is important for export of a majority of proteins, including the β-barrel outer membrane porins [37]. Expression of the integral membrane universal stress protein B (uspB) was increased in 8 h-exposed samples of both strains. This protein is induced by RpoS and carbon starvation and has been implicated in sensing and responding to membrane damage [42]. The RpoS-regulated, osmotically induced protein osmB, described as having a role in membrane resealing, [40] had increased expression only in 8 h-exposed samples of BR21.

We also found decreased expression of genes encoding ribosomal proteins and translation initiating factors in 8 h-exposed samples of both strains, indicating a global dampening of protein translation (Figure S1). This may be an additional effect of the stress response imposed by the antibiotic, involving cellular homeostasis to restrict protein expression. In particular, decreased expression was observed in the gene encoding the CshA DEAD-box protein, which is associated with slow growth, ribosomal biogenesis, and RNA transcript degradation [67]. GSA identified significant enrichment of genes in the ribosome pathway in BR21 (Figure 2).

CREs are a major threat to successful treatment outcomes and an urgent and growing threat to public health [1, 4]. Here, we observed that emergence of high-level carbapenem-resistant subpopulations from a heteroresistant population of KPC-Kp is associated with differential adaptive response to stress initiated by an antibiotic. In two genotypically related strains of heteroresistant K. pneumoniae strains exposed to imipenem followed by incubation in drug-free medium, we observed (1) transcriptional changes that first involved general and osmotic stress response, followed by carbon source utilization and then protein processing, outer membrane integrity, and transport; (2) these sequential stress-adaptive responses to be associated with transient emergence (BR7) as well as irreversible appearance (BR21) of high-level imipenem resistant subpopulations; and (3) transcriptional changes associated with heritable loss of OmpK36 production and enrichment of subpopulations (BR21) that gained high-level CR.

We found that the loss of OmpK36 in the two strains exposed to imipenem followed distinct pathways. Imipenem-exposed BR21 samples showed changes in genes involved in potential modifications in the heptose core, which have been associated with translational repression of ompC in E. coli [68–70]. Strain BR7 had decreased expression of genes encoding a critical juncture of LPS synthesis that may result in the heterogeneity of LPS, or in the reduction of Lipid A in the outer membrane (Figure S2). Such changes could lead to failure of OmpK36 insertion into the outer membrane [68–70]. We also observed an increase in the noncoding RNA, micA, which may cause misfolded outer membrane proteins in response to lethal imipenem exposure [45]. Unlike BR21, which permanently lost OmpK36 as a result of an IS1 insertion, OmpK36 loss in BR7 was reversible, perhaps via renaturation of the transiently misfolded protein. In the latter, once the drug was withdrawn, porin expression was restored, which may indicate a potential fitness advantage to this strain in the absence of drug exposure.

We previously showed that hydrolysis by KPC is required for imipenem-resistant KPC-Kp subpopulations to emerge from a relatively susceptible population [11]. Our present study suggests that KPC is necessary but not sufficient for KPC-Kp to gain high-level carbapenem resistance. Perhaps the first step involves KPC β-lactamase that hydrolyzes a relatively low concentration of imipenem entering the periplasm. This allows some subpopulations to survive. However, continued entry of the drug causes peptidoglycan damage. We propose that this damage induces general and osmotic stress responses followed by redirection of bacterial metabolism from glucose utilization to glutamate-dependent metabolism. This serves multiple purposes to set the stage for a catabolite-mediated adaptive response that feeds key metabolites into the TCA cycle. This response allows yet another set of subpopulations to survive long enough for abolished production of OmpK36, which leads to diminished cell entry of the drug and therefore high-level CR. Phage induction triggered by carbapenem-imposed stress may also play a role in this sequential adaptive response, as observed with BR21.

The limitation of our findings includes results that were obtained under in vitro laboratory conditions with controlled exposures. The transcriptional profile analysis was performed with RNA extracted from bacteria incubated as described in Materials and Methods in drug-free medium after they were exposed to imipenem for 2 and 8 hours, respectively, as analysis of cells immediately after drug exposure would have included mostly transcripts associated with dying cells. The high-level resistance of BR21 was irreversible, whereas BR7 reverted to its preexposure heteroresistant phenotype after incubation in drug-free medium. Thus, what we describe here is not directly related to imipenem exposure but the effect of bacterial propagation in drug-free medium for a subpopulation that survived the initial imipenem selective stress.

Despite these limitations, we observed distinct evolutionary pathways associated with appearance of high-level drug resistance of two carbapenem heteroresistant KPC-Kp strains exposed to a carbapenem prior to their incubation in drug-free medium. We suggest that high-level carbapenem resistance in heteroresistant K. pneumoniae strains results from sequential adaptive changes in response to stress first induced by a carbapenem. Further studies of additional CRE strains are required to confirm or generalize these observations.

These findings provide a rationale for potentially targeting the metabolic pathways we found to be involved in the emergence of CRE subpopulations. They may include inhibition of bacteria-specific polyamine and glutamate catabolic, as well as stress response, phage induction, and LPS synthetic pathways.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Study Strains and Sample Preparation

The KPC-Kp BR7 and BR21 strains in this study were obtained from bloodstream and urinary tract infections, respectively, collected from different hospitals in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, in 2009. Their phenotypic imipenem heteroresistance was previously characterized [11]. No individual patient data was collected. Imipenem-exposed samples were obtained from dilution of overnight cultures standardized by optical density at 600 nm (OD600) to a starting inoculum of 106 cfu/ml. Three biological replicates were each incubated in a lethal imipenem dose of 16 ug/ml for 2 or 8 hours at 37°C with shaking in Mueller-Hinton media (MH). The surviving cells were centrifuged for 15 minutes at 5000 ×g, resuspended in 2 ml drug-free cation-adjusted MH, and grown to midlogarithmic phase (OD600, 0.5). The time required to reach midlogarithmic phase varied from 5 to 6 hours for 8-hour exposed samples and 12 to 15 hours for 2-hour exposed samples. Unexposed control samples were prepared under the same conditions without imipenem and required 2-3 hours to achieve midlogarithmic phase growth. RNA was extracted with the Qiagen RNeasy MiniKit, after stabilization of RNA transcripts with the RNAprotect reagent, according to manufacturer's protocol (Qiagen, MD, USA). Genomic DNA was prepared from all strains with the Qiagen Blood and Tissue DNeasy kit.

3.2. Whole Genome/Transcriptome Sequencing

The number of biological replicates (3) was determined for transcriptome sequencing with published methods to optimize sequencing depth and achieve the power to detect differential expression [71]. RNA and DNA samples were submitted to the QB3 Functional Genomics Laboratory (UC Berkeley) for library preparation and cDNA synthesis (RNA). Study samples were submitted for whole genome sequencing on the Illumina platform at the QB3/Vincent J. Coates Genomics Sequencing Facility (UC Berkeley). Final libraries were quantified by Bioanalzyer and then sequenced via a 300 base-pair, paired-end run on a MiSeq instrument (genome), or via a 100 base-pair, paired-end run on a HiSeq 4000 instrument (transcriptome). Quality of Illumina sequences was analyzed with FastQC (Babraham Institute, Cambridge, UK). Illumina adaptors and low-quality sequences were trimmed with Geneious® version 9.0 (Biomatters, Ltd., New Zealand) or Trimmomatic 0.36 [72].

K. pneumoniae strains BR7 and BR21 were additionally sequenced on the Pacific Biosciences (PacBio) RSII sequencing platform (Pacific Biosciences, Menlo Park, California) at the University of California, Davis Genome Center. The data were de novo assembled with the PacBio hierarchical genome assembly pipeline (HGAP.2) and polished with the Quiver software package. For whole genome assembly, PacBio chromosomal and plasmid DNA sequences were used as reference sequences for mapping Illumina data from the imipenem-exposed study samples. Reads were mapped to plasmids and then to the chromosome with Geneious. Assemblies were submitted to RAST for annotation and subsystem ontological categorization [73]. Variant analysis was performed with the progressive Mauve algorithm running within Geneious. Highly variable phage (with the exception of annotated prophage regions), mobile elements, and intergenic regions were excluded from this portion of the analysis.

3.3. Whole Transcriptome Assembly and Statistical Analysis

Whole transcriptome assembly was performed on reads from triplicate biological samples indexed and mapped to PacBio reference sequences with Bowtie 2.2.3 and TopHat 2.0.13 (http://ccb.jhu.edu/software.shtml). Raw reads per sample are shown in Table S3. Uniquely mapped reads were sorted with SamTools 0.1.19 [74], and counts were obtained with HTSeq 0.6.1. [75]. Differential expression analysis was performed with EdgeR (R, 3.2.3) [76] with count data under a negative binomial model. Low counts were filtered; then remaining counts were normalized to correct for different composition of the sample read libraries. Statistically significant differential expression based on these counts was determined by Fisher's Exact Test to analyze pair-wise tests for differential expression between 3 biological replicates of the 2 h- or 8 h-imipenem-exposed samples compared to unexposed replicate samples and were reported as a log2-fold change of the resulting normalized differential expression counts. The topTags function subsequently adjusted the raw p values for multiple comparisons with the Benjamini-Hochberg False Discovery Rate (FDR) correction. Differentially expressed genes with FDR ≤ 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Pie chart and heat map figures were created with GraphPad Prism version 7 (GraphPad software, La Jolla, CA). Raw data, including dispersion of counts between biological replicates, is available as supplemental material (Table S3). Gene Set Analysis (GSA) was conducted to determine if differential expression of genes in certain groups was overrepresented in imipenem-exposed samples. The set of differentially expressed genes generated from EdgeR analysis were submitted to the KEGG Automated Annotation Server (KAAS, http://www.genome.jp/tools/kaas/) to generate KEGG orthology (KO) identifiers [77] and then used as input for Generally Applicable Gene-set Enrichment (GAGE) analysis running on the R/Bioconductor Pathview server (https://pathview.uncc.edu) [78–80]. An FDR q-value cutoff of 0.2 was used to assess pathway significance.

3.4. Accession Numbers

Complete genomes and plasmids for BR7 and BR21 are deposited in the NCBI database under Bioproject PRJNA358426 and Biosamples SAMN06173548 (BR7) and SAMN06173549 (BR21).

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Beatriz Moreira of the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro for providing the KPC-Kp strains for this study. They also thank Karen Lundy (QB3 Berkeley Functional Genomics Laboratory), Shana McDevitt (QB3 Berkeley Genomics Sequencing Laboratory), and Lutz Froenick, (UC Davis Genome Center) and thank Jason Huff and Ke Bi (QB3 Berkeley Computational Genomics Resource Laboratory) and the trainers at D-Lab (UC Berkeley), for bioinformatics computation resources and training, Aaron Culich (Berkeley Institute for Data Science) and Rick Jaffe (Research Data Management) for data management infrastructure, and Jeffrey Skerker (UC Berkeley Biosciences Institute) for assembly advice. Finally, they thank Mallika Lal for technical assistance with the samples and Nicole Tarlton for critical review of the manuscript. This study was supported in part by RB Roberts Bacterial Drug-Resistant Infection Research Fund. This work used the Vincent J. Coates Genomics Sequencing Laboratory at UC Berkeley, supported by NIH S10 OD018174 Instrumentation grant.

Disclosure

The funders had no role in study design, data collection and interpretation, or the decision to submit the work for publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1: lethal imipenem exposure is associated with a global dampening of protein synthesis. Changes in outer membrane protein synthesis, protein transport and processing (Section 1, above the horizontal line), and protein translation (Section 2, below the horizontal line) were observed to a greater extent in BR21 than in BR7 at 8 h of imipenem exposure. Figure S2: transcriptional changes in the peptidoglycan biosynthetic pathway (Section 1, lines 1–8) and in key junctures of lipopolysaccharide (LPS) biosynthesis (Section 2, lines 9–23) after lethal imipenem exposure. At 8 h of exposure, genes involved in LPS synthesis were downregulated more prominently in BR21 than in B7. Table S1: characteristics of heteroresistant KPC-producing K. pneumoniae study strains, including source of infection, chromosome size, plasmid types and sizes, and carriage of prophage. Table S2: chromosomal sequence identity and variant analysis of KPC K. pneumoniae study strains and variant analysis between unexposed and imipenem-exposed samples. BR7 v BR21, chromosomal identity: Table S3: differentially expressed genes (FDR < 0.05) due to lethal IPM exposure of 2 h- and 8 h-exposed samples of heteroresistant KPC-producing K. pneumoniae strains. Chromosomal and plasmid-borne genes are shown separately. Raw reads by sample are shown at the bottom of the tables. Table S4: differentially expressed genes induced by stress regulons as a response to lethal imipenem exposure of heteroresistant KPC-producing K. pneumoniae study strains.

References

- 1.Antibiotic Resistance Threats in the United States, in. US Departent of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Strategy for Combating Antibiotic Resistant Bacteria. The White House; 2014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Antimicrobial Resistance Global Report on Surveillance. in: World Health Organization; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nordmann P., Dortet L., Poirel L. Carbapenem resistance in Enterobacteriaceae: Here is the storm! Trends in Molecular Medicine. 2012;18(5):263–272. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2012.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Riley L. W. Pandemic lineages of extraintestinal pathogenic Escherichia coli. Clinical Microbiology and Infection. 2014;20(5):380–390. doi: 10.1111/1469-0691.12646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Arnold R. S., Thom K. A., Sharma S., Phillips M., Kristie Johnson J., Morgan D. J. Emergence of Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase-producing bacteria. Southern Medical Journal. 2011;104(1):40–45. doi: 10.1097/SMJ.0b013e3181fd7d5a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Falagas M. E., Makris G. C., Dimopoulos G., Matthaiou D. K. Heteroresistance: A concern of increasing clinical significance? Clinical Microbiology and Infection. 2008;14(2):101–104. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2007.01912.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hirsch E. B., Tam V. H. Detection and treatment options for Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemases (KPCs): an emerging cause of multidrug-resistant infection. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. 2010;65(6):1119–1125. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkq108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nordmann P., Cuzon G., Naas T. The real threat of Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase-producing bacteria. The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 2009;9(4):228–236. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(09)70054-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tenover F. C., Kalsi R. K., Williams P. P., et al. Carbapenem resistance in Klebsiella pneumoniae not detected by automated susceptibility testing. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2006;12(8):1209–1213. doi: 10.3201/eid1708.060291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Adams-Sapper S., Nolen S., Donzelli G. F., et al. Rapid induction of high-level carbapenem resistance in heteroresistant KPC-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 2015;59(6):3281–3289. doi: 10.1128/AAC.05100-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.El-Halfawy O. M., Valvano M. A. Antimicrobial heteroresistance: An emerging field in need of clarity. Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 2015;28(1):191–207. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00058-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Morand B., Mühlemann K. Heteroresistance to penicillin in Streptococcus pneumoniae. Proceedings of the National Acadamy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2007;104(35):14098–14103. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0702377104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nodari C. S., Barth A. L., Ribeiro V. B. Imipenem heteroresistance: High prevalence among Enterobacteriaceae Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase producers. Journal of Medical Microbiology. 2015;64(1):124–126. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.081869-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Acar M., Mettetal J. T., Van Oudenaarden A. Stochastic switching as a survival strategy in fluctuating environments. Nature Genetics. 2008;40(4):471–475. doi: 10.1038/ng.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Balaban N. Q., Merrin J., Chait R., Kowalik L., Leibler S. Bacterial persistence as a phenotypic switch. Science. 2004;305(5690):1622–1625. doi: 10.1126/science.1099390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Baym M., Lieberman T. D., Kelsic E. D., et al. Spatiotemporal microbial evolution on antibiotic landscapes. Science. 2016;353(6304):1147–1151. doi: 10.1126/science.aag0822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang X., Kang Y., Luo C., et al. Heteroresistance at the single-cell level: Adapting to antibiotic stress through a population-based strategy and growth-controlled interphenotypic coordination. mBio. 2014;5(1) doi: 10.1128/mBio.00942-13.e00942-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Elliott E., Brink A. J., van Greune J., et al. In Vivo Development of Ertapenem Resistance in a Patient with Pneumonia Caused by Klebsiella pneumoniae with an Extended-Spectrum-Lactamase. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2006;42(11):e95–e98. doi: 10.1086/503264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Falagas M. E., Lourida P., Poulikakos P., Rafailidis P. I., Tansarli G. S. Antibiotic treatment of infections due to carbapenem-resistant enterobacteriaceae: systematic evaluation of the available evidence. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 2014;58(2):654–663. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01222-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mena A., Plasencia V., García L., et al. Characterization of a large outbreak by CTX-M-1-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae and mechanisms leading to in vivo carbapenem resistance development. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 2006;44(8):2831–2837. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00418-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Poirel L., Héritier C., Spicq C., Nordmann P. In vivo acquisition of high-level resistance to imipenem in Escherichia coli. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 2004;42(8):3831–3833. doi: 10.1128/JCM.42.8.3831-3833.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Qureshi Z. A., Paterson D. L., Potoski B. A., et al. Treatment outcome of bacteremia due to KPC-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae: superiority of combination antimicrobial regimens. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 2012;56(4):2108–2113. doi: 10.1128/AAC.06268-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Song W., Suh B., Choi J. Y., et al. In vivo selection of carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae by OmpK36 loss during meropenem treatment. Diagnostic Microbiology And Infectious Disease. 2009;65(4):447–449. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2009.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Weisenberg S. A., Morgan D. J., Espinal-Witter R., Larone D. H. Clinical outcomes of patients with Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase-producing K. pneumoniae after treatment with imipenem or meropenem. Diagnostic Microbiology And Infectious Disease. 2009;64(2):233–235. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2009.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Morrill H. J., Pogue J. M., Kaye K. S., LaPlante K. L. Treatment options for carbapenem-resistant enterobacteriaceae infections. Open Forum Infectious Diseases. 2015;2(2) doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofv050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bowers J. R., Kitchel B., Driebe E. M., et al. Genomic analysis of the emergence and rapid global dissemination of the clonal group 258 Klebsiella pneumoniae pandemic. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(7) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0133727.0133727 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen L., Chavda K. D., Melano R. G., et al. Comparative genomic analysis of kpc-encoding pkpqil-like plasmids and their distribution in New Jersey and New York hospitals. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 2014;58(5):2871–2877. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00120-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.DeLeo F. R., Chen L., Porcella S. F., et al. Molecular dissection of the evolution of carbapenem-resistant multilocus sequence type 258 Klebsiella pneumoniae. Proceedings of the National Acadamy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2014;111(13):4988–4993. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1321364111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Munoz-Price L. S., Poirel L., Bonomo R. A., et al. Clinical epidemiology of the global expansion of Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemases. The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 2013;13(9):785–796. doi: 10.1016/s1473-3099(13)70190-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Weber H., Polen T., Heuveling J., Wendisch V. F., Hengge R. Genome-wide analysis of the general stress response network in Escherichia coli: σS-dependent genes, promoters, and sigma factor selectivity. Journal of Bacteriology. 2005;187(5):1591–1603. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.5.1591-1603.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Holms H. Flux analysis and control of the central metabolic pathways in Escherichia coli. FEMS Microbiology Reviews. 1996;19(2):85–116. doi: 10.1016/S0168-6445(96)00026-5. doi: 10.1016/S0168-6445(96)00026-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kretzschmar U., Rückert A., Jeoung J.-H., Görisch H. Malate: Quinone oxidoreductase is essential for growth on ethanol or acetate in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Microbiology. 2002;148(12):3839–3847. doi: 10.1099/00221287-148-12-3839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Metzner M., Germer J., Hengge R. Multiple stress signal integration in the regulation of the complex σS-dependent csiD-ygaF-gabDTP operon in Escherichia coli. Molecular Microbiology. 2004;51(3):799–811. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03867.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schneider B. L., Hernandez V. J., Reitzer L. Putrescine catabolism is a metabolic response to several stresses in Escherichia coli. Molecular Microbiology. 2013;88(3):537–550. doi: 10.1111/mmi.12207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bender R. A. Regulation of the histidine utilization (Hut) system in bacteria. Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews. 2012;76(3):565–584. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00014-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Baneyx F., Mujacic M. Recombinant protein folding and misfolding in Escherichia coli. Nature Biotechnology. 2004;22(11):1399–1408. doi: 10.1038/nbt1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Battesti A., Hoskins J. R., Tong S., et al. Anti-adaptors provide multiple modes for regulation of the RssB adaptor protein. Genes & Development. 2013;27(24):2722–2735. doi: 10.1101/gad.229617.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Brzoska P., Boos W. Characteristics of a ugp-encoded and phoB-dependent glycerophosphoryl diester phosphodiesterase which is physically dependent on the ugp transport system of Escherichia coli. Journal of Bacteriology. 1988;170(9):4125–4135. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.9.4125-4135.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Charoenwong D., Andrews S., Mackey B. Role of rpoS in the development of cell envelope resilience and pressure resistance in stationary-phase Escherichia coli. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 2011;77(15):5220–5229. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00648-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.De Majumdar S., Yu J., Fookes M., et al. Elucidation of the RamA Regulon in Klebsiella pneumoniae Reveals a Role in LPS Regulation. PLoS Pathogens. 2015;11(1):p. e1004627. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Farewell A., Kvint K., Nyström T. uspB, a new σ(S)-regulated gene in Escherichia coli which is required for stationary-phase resistance to ethanol. Journal of Bacteriology. 1998;180(23):6140–6147. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.23.6140-6147.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Feehily C., Karatzas K. A. G. Role of glutamate metabolism in bacterial responses towards acid and other stresses. Journal of Applied Microbiology. 2013;114(1):11–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2012.05434.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gama-Castro S., Salgado H., Santos-Zavaleta A., et al. RegulonDB version 9.0: High-level integration of gene regulation, coexpression, motif clustering and beyond. Nucleic Acids Research. 2016;44(1):D133–D143. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv1156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Guillier M., Gottesman S., Storz G. Modulating the outer membrane with small RNAs. Genes & Development. 2006;20(17):2338–2348. doi: 10.1101/gad.1457506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kaldalu N., Mei R., Lewis K. Killing by Ampicillin and Ofloxacin Induces Overlapping Changes in Escherichia coli Transcription Profile. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 2004;48(3):890–896. doi: 10.1128/AAC.48.3.890-896.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kamenek S., Gur-Bertok D. Global transcriptional responses to the bacteriocin colicin M in Escherichia coli. BMC Microbiology. 2013:p. 42. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-13-42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Laubacher M. E., Ades S. E. The Rcs phosphorelay is a cell envelope stress response activated by peptidoglycan stress and contributes to intrinsic antibiotic resistance. Journal of Bacteriology. 2008;190(6):2065–2074. doi: 10.1128/JB.01740-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lorca G. L., Ezersky A., Lunin V. V., et al. Glyoxylate and pyruvate are antagonistic effectors of the Escherichia coli IcIR transcriptional regulator. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2007;282(22):16476–16491. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M610838200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Majdalani N., Gottesman S. The Rcs phosphorelay: A complex signal transduction system. Annual Review of Microbiology. 2005;59:379–405. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.59.050405.101230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nair S., Finkel S. E. Dps protects cells against multiple stresses during stationary phase. Journal of Bacteriology. 2004;186(13):4192–4198. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.13.4192-4198.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Oropeza R., Salgado-Bravo R., Calva E. Deletion analysis of RcsC reveals a novel signaling pathway controlling poly-N-acetylglucosamine synthesis and biofilm formation in Escherichia coli. Microbiology (United Kingdom) 2015;161(4):903–913. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.000050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pratt L. A., Hsing W., Gibson K. E., Silhavy T. J. From acids to osmZ: Multiple factors influence synthesis of the OmpF and OmpC porins in Escherichia coli. Molecular Microbiology. 1996;20(5):911–917. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1996.tb02532.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sarkar D., Siddiquee K. A. Z., Araúzo-Bravo M. J., Oba T., Shimizu K. Effect of cra gene knockout together with edd and iclR genes knockout on the metabolism in Escherichia coli. Archives of Microbiology. 2008;190(5):559–571. doi: 10.1007/s00203-008-0406-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Uppal S., Shetty D. M., Jawali N. Cyclic AMP receptor protein regulates cspd, a bacterial toxin gene, in escherichia coli. Journal of Bacteriology. 2014;196(8):1569–1577. doi: 10.1128/JB.01476-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Vijayakumar S. R. V., Kirchhof M. G., Patten C. L., Schellhorn H. E. RpoS-regulated genes of Escherichia coli identified by random lacZ fusion mutagenesis. Journal of Bacteriology. 2004;186(24):8499–8507. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.24.8499-8507.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wolfe A. J. Physiologically relevant small phosphodonors link metabolism to signal transduction. Current Opinion in Microbiology. 2010;13(2):204–209. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2010.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bastian F. B., Chibucos M. C., Gaudet P., et al. The confidence information ontology: A step towards a standard for asserting confidence in annotations. Database. 2015;2015 doi: 10.1093/database/bav043.bav043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kornberg H. L. The role and control of the glyoxylate cycle in Escherichia coli. Biochemical Journal. 1966;99(1):1–11. doi: 10.1042/bj0990001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Belitsky B. R., Sonenshein A. L. GabR, a member of a novel protein family, regulates the utilization of γ-aminobutyrate in Bacillus subtilis. Molecular Microbiology. 2002;45(2):569–583. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.03036.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Goude R., Renaud S., Bonnassie S., Bernard T., Blanco C. Glutamine, glutamate, and α-glucosylglycerate are the major osmotic solutes accumulated by Erwinia chrysanthemi strain 3937. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 2004;70(11):6535–6541. doi: 10.1128/AEM.70.11.6535-6541.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yancey P. H. Organic osmolytes as compatible, metabolic and counteracting cytoprotectants in high osmolarity and other stresses. Journal of Experimental Biology. 2005;208(15):2819–2830. doi: 10.1242/jeb.01730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Adams-Sapper S. Characteristics and coordinated mechanisms of carbapenem heteroresistance in KPC-producing Enterobacteriaceae [Doctoral, thesis] Berkeley, Calif, USA: University of California; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Chen S., Zhang A., Blyn L. B., Storz G. MicC, a second small-RNA regulator of omp protein expression in Escherichia coli. Journal of Bacteriology. 2004;186(20):6689–6697. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.20.6689-6697.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Delihas N., Forst S. MicF: An antisense RNA gene involved in response of Escherichia coli to global stress factors. Journal of Molecular Biology. 2001;313(1):1–12. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.5029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Klein G., Raina S. Regulated control of the assembly and diversity of lps by noncoding sRNAs. BioMed Research International. 2015;2015 doi: 10.1155/2015/153561.153561 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Iost I., Bizebard T., Dreyfus M. Functions of DEAD-box proteins in bacteria: Current knowledge and pending questions. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta - Gene Regulatory Mechanisms. 2013;1829(8):866–877. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2013.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ames G. F., Spudich E. N., Nikaido H. Protein composition of the outer membrane of Salmonella typhimurium: effect of lipopolysaccharide mutations. Journal of Bacteriology. 1974;117(2):406–416. doi: 10.1128/jb.117.2.406-416.1974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Klein G., Lindner B., Brabetz W., Brade H., Raina S. Escherichia coli K-12 suppressor-free mutants lacking early glycosyltransferases and late acyltransferases: minimal lipopolysaccharide structure and induction of envelope stress response. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2009;284(23):15369–15389. doi: 10.1074/jbc.m900490200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ried G., Hindennach I., Henning U. Role of lipopolysaccharide in assembly of Escherichia coli outer membrane proteins OmpA, OmpC, and OmpF. Journal of Bacteriology. 1990;172(10):6048–6053. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.10.6048-6053.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hart S. N., Therneau T. M., Zhang Y., Poland G. A., Kocher J.-P. Calculating sample size estimates for {RNA} sequencing data. Journal of Computational Biology. 2013;20(12):970–978. doi: 10.1089/cmb.2012.0283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Bolger A. M., Lohse M., Usadel B. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics. 2014;30(15):2114–2120. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Aziz R. K., Bartels D., Best A., et al. The RAST Server: rapid annotations using subsystems technology. BMC Genomics. 2008;9, article 75 doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-9-75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Li H., Handsaker B., Wysoker A., et al. The sequence alignment/map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics. 2009;25(16):2078–2079. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Anders S., Pyl P. T., Huber W. HTSeq—a Python framework to work with high-throughput sequencing data. Bioinformatics. 2015;31(2):166–169. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Robinson M. D., McCarthy D. J., Smyth G. K. edgeR: a Bioconductor package for differential expression analysis of digital gene expression data. Bioinformatics. 2010;26(1):139–140. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Moriya Y., Itoh M., Okuda S., Yoshizawa A. C., Kanehisa M. KAAS: an automatic genome annotation and pathway reconstruction server. Nucleic Acids Research. 2007;35(2, supplement):W182–W185. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Luo W., Brouwer C. Pathview: An R/Bioconductor package for pathway-based data integration and visualization. Bioinformatics. 2013;29(14):1830–1831. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btt285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Luo W., Friedman M. S., Shedden K., Hankenson K. D., Woolf P. J. GAGE: generally applicable gene set enrichment for pathway analysis. BMC Bioinformatics. 2009;10(1, article 161) doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-10-161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Luo W., Pant G., Bhavnasi Y. K., Blanchard S. G., Brouwer C. Pathview Web: User friendly pathway visualization and data integration. Nucleic Acids Research. 2017;45(1):W501–W508. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1: lethal imipenem exposure is associated with a global dampening of protein synthesis. Changes in outer membrane protein synthesis, protein transport and processing (Section 1, above the horizontal line), and protein translation (Section 2, below the horizontal line) were observed to a greater extent in BR21 than in BR7 at 8 h of imipenem exposure. Figure S2: transcriptional changes in the peptidoglycan biosynthetic pathway (Section 1, lines 1–8) and in key junctures of lipopolysaccharide (LPS) biosynthesis (Section 2, lines 9–23) after lethal imipenem exposure. At 8 h of exposure, genes involved in LPS synthesis were downregulated more prominently in BR21 than in B7. Table S1: characteristics of heteroresistant KPC-producing K. pneumoniae study strains, including source of infection, chromosome size, plasmid types and sizes, and carriage of prophage. Table S2: chromosomal sequence identity and variant analysis of KPC K. pneumoniae study strains and variant analysis between unexposed and imipenem-exposed samples. BR7 v BR21, chromosomal identity: Table S3: differentially expressed genes (FDR < 0.05) due to lethal IPM exposure of 2 h- and 8 h-exposed samples of heteroresistant KPC-producing K. pneumoniae strains. Chromosomal and plasmid-borne genes are shown separately. Raw reads by sample are shown at the bottom of the tables. Table S4: differentially expressed genes induced by stress regulons as a response to lethal imipenem exposure of heteroresistant KPC-producing K. pneumoniae study strains.