Abstract

Snakes have fascinated humankind for millennia. Snakebites are a serious medical, social, and economic problem that are experienced worldwide; however, they are most serious in tropical and subtropical countries. The reasons for this are 1) the presence of more species of the most dangerous snakes, 2) the inaccessibility of immediate medical treatment, and 3) poor health care. The goal of this study was to collect information concerning rare, less utilized, and less studied medicinal plants. More than 100 plants were found to have potential to be utilized as anti-snake venom across India. Data accumulated from a variety of literature sources revealed useful plant families, the parts of plants used, and how to utilize them. In India, there are over 520 plant species, belonging to approximately 122 families, which could be useful in the management of snakebites. This study was conducted to encourage researchers to create herbal antidotes, which will counteract snake venom. These may prove to be an inexpensive and easily assessable alternative, which would be of immense importance to society. Plants from families such as Acanthaceae, Arecaceae, Apocynaceae, Caesalpiniaceae, Asteraceae, Cucurbitaceae, Fabaceae, Euphorbiaceae, Lamiaceae, Rubiaceae, and Zingiberaceae are the most useful. In India, experts of folklore are using herbs either single or in combination with others.

Keywords: Appraise traditional medicinal plants, Ethnomedicine, India, Snake antivenom

1. Introduction

For centuries, plants have been important in the treatment of a wide variety of illnesses, diseases, and disorders.1, 2 The inherent traditional systems of medicine, along with information from conservative folklore, are serving a large section of the populace, particularly in rural and tribal areas, despite the dawn of modern medicine. Ethnobotany is the scientific and systematic study of traditional knowledge and customs of people concerning plants and their medical, religious, and other uses. Studies involve literature surveys, detailed investigations, analyses, interpretation, and conclusions concerning various research and scientific data. An ethno-medico-botanical appraisal includes discussions with natives, as well as utilization of available facts and data regarding folklore literature.3 Indigenous medicinal plant species have been added to several recent drug formulations and preparations for fundamental health care.3

2. Methodology

The current study provides a collection of information on medicinal plants that grow and can be utilized in various regions of India for snakebite treatment. The appropriate literature, including books, journals, and reports, was reviewed. The relevant information was searched using various electronic catalogs (e.g., Google Scholar, Medline, NISCAIR, Science Direct, Scirus, and Scopus) and keywords such as “anti-venom activity,” “ethno botany,” “ethno pharmacology,” “Indian,” “indigenous,” “medicinal plants,” “snake bite,” and “survey.” It was difficult to include all the information regarding medicinal plants used for snakebite treatment, and as such this study focused on information that would be easily accessible for researchers. Over the last few decades, people from different tribal communities have been recoding and maintaining data regarding traditional and tribal knowledge related to the use of medicinal plants. However, this information has, until now, not been made available to the modern world. In this regard, information on tribal and local use of various plants has been made available and a systematic “ready to use” list of medicinal plants has been formed. The list consists of data, including biological source(s), family, local name(s), part(s) used, method(s) of preparation/formulations, and reference(s). In this review, care was taken to ensure the identification of the herbal medicinal plants that were in the original resources (Table 1).

Table 1.

List of Medicinal Plants Used for Treatment of Snakebites in India

| Biological source | Family | Local names | Part used | Method of administration | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ajuga bracteosa Wall Ex Benth | Lamiaceae | Neelkanthi, Nilkanthi, Kanasar | Rt | Root extract is used as an antidote | 29 |

| Ailanthus excels Roxb | Simaroubaceae | Peeyamaram | Lv | Decoction of the leaves with the leaves of Aristolochia indica prepared and mixed with goats’ milk to drink for treatment of snakebites | 30, 31 |

| Alangium lamarbi Thwaites | Alangiaceae | – | Br | Bark paste is taken orally | 32 |

| Alangium salvifolium (Linnf) Wang | Alangiaceae | Ankol, Ankula, Alangi, Aankla | Wp, R, Lv, St, Br | Approximately 15 g of bark ground + 10–12 black peppers mixed with 72 g animal fat given every 2 h to cure snakebite Root bark decoction is given internally to treat snakebite |

33, 34, 35, 36 |

| Albizia lebbeck (Linn) Benth | Fabaceae | Siris, Kala, Siris, Segta/Siris, Hombage, bhandi | Lv, Br, Fl, Wp, R | Paste of bark is used | 31, 37, 38, 39, 40 |

| Allium cepa Linn | Liliaceae | Piyaz, Venkayam | Bb | The paste made from fresh skin of bulb is used for external application (5 d) | 38, 41 |

| Allium sativum Linn | Liliaceae | Lasoon | Bb | Bulb is made into paste and given orally | 41, 42 |

| Alsophila glabra Sensu Bedd | Cyatheaceae | – | Rz | Unknown | 43 |

| Alstonia scholaris (Linn) RBr | Apocynaceae | Saptparni, Chatni, Satina, Barap lei, Lawthong | Lv, Br | Bark decoction given orally | 44, 45, 46, 47 |

| Alstonia venenata RBr | Apocynaceae | Analivegham, Elaipalai, Analivegham | St, Br, Rt | Tablets made from paste of stem bark are taken with cow's urine Decoction also taken orally |

48, 49 |

| Alternanthera sessilis (Linn) R Brown ex DC | Amaranthaceae | KandiliJari | St, Lv | External application of stem and leaf paste is used | 50, 51, 52 |

| Amaranthus blitum Linn | Amaranthaceae | Chaulai | Rt | Root powder is used | 39 |

| Amaranthus spinosus Linn | Amaranthaceae | Kateli, Mullikeerai, Kateli, Chaurai, Kanta-bhaji, Kateli-chaulai | R, Lv Wp | Paste of leaves is applied locally | 39, 53, 54, 55, 56 |

| Amaranthus viridis Linn | Amaranthaceae | Khutora, Chaulai | Lv, St | Leaf/stem paste is applied externally | 53 |

| Ammannia baccifera Linn | Lythraceae | Neerumulli | Wp | Whole plant powder mixed with hot cow's milk to drink | 57 |

| Amomum aromaticum Roxb | Zingiberaceae | Borelachi, Chakma, Bodaelachi | Sd | Seed paste is used | 58 |

| Amomum subulatum Roxb | Zingiberaceae | Bara elachi | Pd | Boil 2–3 pods and drink the extract twice daily for a week | 58 |

| Amorphophallus campanulatus Blume: ex DC | Araceae | Bhabdi | Tb | The tubers are crushed and applied externally | 59 |

| Amorphophallus commutatus (Schott) Engler | Araceae | – | Tb | Unknown | 60 |

| Andrographis alata Nees | Acanthaceae | Periyanangai | Lv | A handful of fresh leaves or juice is taken orally | 61 |

| Andrographis echioides Nees | Acanthaceae | Nadnaur, Gusum puru, Gopuranthangi | Wp | Paste of whole plant is given orally with water It is also applied externally |

62 |

| Andrographis lineate Wallich ex | Acanthaceae | Siriyanangai, Periyanangai, Malaiveempu | Wp, Lv | Paste of leaves is applied externally About 3 grams of whole plant paste is directly administered orally |

63, 64, 65 |

| Andrographis paniculata (Burm f) Wall Ex Nees | Acantheceae | Kalmegh, Bhumi neem, Neelaveppu, Nilavaembu, Chirianangai, Sirianangai, Periyanangai | Lv, Lv, Wp | A decoction of the leaves with the leaves of Andrographis alata is given Decoction or extract is applied externally |

30, 63, 65, 66, 67, 68, 69, 70, 71, 72, 73, 74 |

| Anisomeles indica (Linn) Kuntze | Lamiaceae | Paeimiratti | Lv | Paste of leaf is taken | 75 |

| Anisomeles malabarica (Linn) RBr | Lamiaceae | Siriyapaeyamarati, Peymarutti | Lv | The leaf or juice mixed with water to drink | 75 |

| Annona squamosa Linn | Annonaceae | Seethaphala | St, Br, Lv | Unknown | 57, 76 |

| Anogeissus acuminata Wall | Combretaceae | Dhavra | Pl | Poultice is applied | 77 |

| Anthocephalus cadamba Miq | Rubiaceae | Kadam | Wp | Unknown | 39 |

| Antidesma bunius (Linn) Spreng | Phyllanthaceae | Tuaitit | Lv | Unknown | 78 |

| Arachne cordifolia (Decne) Hurusawa | Euphorbiaceae | – | Lv, St | Unknown | 79 |

| Ardisia humilis Vahl | Myrsinaceae | Kumbreth | Br | Crushed paste is applied | 80 |

| Argemone Mexicana Linn | Papaveraceae | Sialkatahi, Datturi, Pilikateli, Bharbhand, Brahmathandu | Lv, Sd, Rt | Leaf/seed decoction given orally (7 d) Root paste is also used |

53, 81, 82 |

| Ariesaema barnesii C Fischer | Araceae | Kaattuchenai | Tb | Dried tuber of this plant and whole plant paste of Andrographis paniculata (1:1) applied over wounds twice a day | 69 |

| Arisaema flavum (Forsskal) Schott | Araceae | Sapp googli | Tb | The tubers are crushed and a paste is made that is applied | 83 |

| Arisaema jacquemontii Blume | Araceae | Khaprya | Fr, Rz | Unknown | 79, 80 |

| Arisaema leschenaultii Bl ume | Araceae | Havina jola | Rt, Lv, Fr | Fruit/leaf and root paste is applied on the spot of snakebite thrice a day for about 8 d. | 81 |

| Arisaema tortuosum (Wall) Schott | Araceae | Haap roodakaro, Halida, Kotukand, Chambus, Chakrata | Tb, Bb | Paste of the tuber in applied. Infusion of fresh bulb is taken orally thrice daily |

60, 84, 85 |

| Aristolochia bracteolate Lamk | Aristolochiaceae | Kalipad, Aduthinnapalai | Lv, Rt | Leaf paste applied externally, as well as infusion taken orally | 60, 75, 85, 86 |

| Aristolochia indica Linn | Aristolochiaceae | Sapasan, Garalika, Garudi, Nagbel, Arkamul, Birthwort, Ishwarmul, Bhedi-Janete, Karalakam, Kaliparh, Kaligulesar, Eashwari, Eshwarballi, Perumarindu, Karuda kodi, Garudakodi, Thalaisuruli | Rt, Wp | Fresh roots are ground along with Rouwalfia serpentina mixed in water taken twice daily (3 d) Root powder is snuffed Root juice is given orally and root paste applied locally |

3, 34, 54, 61, 62, 71, 75, 87, 88, 89, 90, 91, 92, 93, 94, 95, 96, 97 |

| Aristolochia tagala Cham | Aristolochiaceae | Samta, Valiya, Eswaramulli, Perumarunt, Hukodi | Rt | Crushed and mixed with water and drunk, as well as fresh roots ground and applied externally on affected area | 80, 98 |

| Artocarpus heterophyllus Lam | Moraceae | Kanthal | Pn | Drink 1 cup juice thrice daily | 94 |

| Artocarpus hirsutus Lam | Moraceae | – | Br | Bark paste made with coconut oil and applied | 99 |

| Artocarpus integrifolia | Artocarpaceae | Kothal, Theibong | Fr | Unknown | 78 |

| Asparagus racemosus Willd | Liliaceae | Halavu, Makkala, Beru, Satvari | Rt | Paste of the fasciculate root is applied externally | 3, 100 |

| Asystasia gangetica Linn | Acanthaceae | Silandhinaayagam | Lv | Leaf paste is given | 90 |

| Azadirachta indica A Juss | Meliaceae | Vembu, Veempu, Neem | Fl, Br, Lv, Fr | Decoction/paste is prepared and given orally (7 d) | 38, 54, 59, 101 |

| Bacopa monnieri (Linn) Pennell | Scrophulariaceae | Brahmisak, Nirbirami, Neeripirami, Brahmi | Br, Lv, Wp | Juice mixed with castor oil is applied externally to treat Leaf powder decoction mixed with hot cow's milk taken orally |

3, 86 |

| Barleria cristata Linn | Acanthaceae | Kali, Brenkad | Lv, R, Sd | Leaf juice is applied | 50 |

| Barleria prionitis Linn | Acanthaceae | Kattukanagambaram | Rt | Decoction taken orally | 49 |

| Boerhaavia diffusa Linn | Nyctaginaceae | Punarnawa, Dabbal bhaji, Chotwa bhaji, Patharchatta, Biskhapara, Ittsitt | Lv, Wp | Leaf juice is also applied locally and taken orally for 7 d | 39, 50 |

| Boerhavia repens Linn | Nyctaginaceae | Ponownowa | Rt | Unknown | |

| Bombax ceiba Linn | Bombaceae | Ilavu, Kate savar, Semal, Simul, Semar, Phunchawng, Simbal, Pikriisii | Fls, RBr, Sd | Paste of flowers/fruits/leaves is applied on the bitten spot | 39, 80 |

| Bryophyllum pinnatum Kuntz | Crassulaceae | Dupartenga | Lv | Unknown | 53 |

| Buchanania lanzan Spr | Anacardiaceae | Char, Chironji, Achar, Chironji, Chirongi, Pial | Br | Unknown | 37 |

| Butea monosperma (Lamk) Taub | Fabaceae | Palash, Dhak, Parsa, Plash | Br, Lv, Fl, Gu, Sd, St, Br, Re, Lx | Bark paste applied on swelling Paste of one seed in 10 mL lemon juice is given orally |

38 |

| Caesalpinia bonduc (Linn) Roxb | Caesalpiniaceae | Poonainagam, Karanj | Sd | Seeds paste applied externally (2 weeks) | 39, 95 |

| Calotropis gigantea (L) R Br | Asclepiadaceae | Dev rui, Aak, Ekke, Akanda, Erukku, Aakdo, Safedaakdo, Gadsa, Akanda, Erukku | R, Lx | Root bark is ground into paste and made into pills and given orally Leaf latex is applied externally |

43, 76, 77, 90 |

| Calotropis procera (Ait) R Br | Asclepiadaceae | Rui, Rai, Aakori: Aakra, Biliekke, Ekka (Safed Ak), Rakta arka, Vellerukku, Akra, Aak, Madar, Safed, Madar, Gadsa, Akwan | Lx, Rt, Young, Bd | Leaf latex is applied on bitten area Root is crushed and given to drink and applied externally |

75, 99 |

| Cannabis sativa Linn | Cannabaceae | Bhang | Lv | Leaf paste is used | 38 |

| Capparis decidua (Forssk) Edgew | Capparaceae | Kareel, Karerua | Fr, Sd | Fruits are eaten | 39, 92 |

| Capsicum annum Linn | Solanaceae | Marchiya | Rt | Unknown | 41 |

| Cardiospermum luridium Linn | Sapindaceae | Moddacoatan | Wp | The whole plant powder mixed with goat's milk to drink | 75 |

| Carica papaya Linn | Caricaceae | Papita, Amrurbhanda, Papita | Fr, Sd, Lx | Unripened fruit of Carica papaya is taken and the skin is removed by slicing, salt is then rubbed over it, and the fruit is then placed over the bite with sliced portions in contact with the bite and bandaged Few drops of latex are applied to snakebite wound for quick healing |

34 |

| Cassia alata Linn | Caesalpiniaceae | Senna, Khor-pat daopata, Seemaiyagathi | Lv | Paste of leaves is applied externally, as well as given orally | 78 |

| Cassia fistula Linn | Caesalpiniaceae | Amaltash, Dhanba, Amaltas, Sonarkhi, Kakke | Fr, Sd, Lv, St, R, Br | The paste & decoction of root bark with black pepper is given orally Paste of stem bark applied on bitten place Fruit pulp is used |

37, 38, 39, 62 |

| Cassia occidentalis Linn | Caesalpiniaceae | Kasaundi, Kasondi, Peeperambi, Thagarai | Rt, Lv | Oral administration of root paste | 38, 39, 67 |

| Cassia sophera Linn | Caesalpiniaceae | Sularai | Rt | Unknown | 86 |

| Cassia tora Linn | Caesalpiniaceae | Takala, Sickle, senna, Chakawad, Chakunda, Tagarai, Bon medelwa | Rt, Lv | Root paste & leaf decoction is applied externally (30 d) | 39, 53 |

| Catharanthus roseus G Don | Apocynaceae | Nithya pushpa | Rt | Root paste mixed with pepper and lime is applied externally | 81 |

| Cayratia trifolia (Linn) Domin | Vitaceae | Khhata nimbi | Tb | Paste of tuber applied on the affected area | 84 |

| Centratherum anthelminticum (L) Kuntze | Asteraceae | Kattujeerakam | Sd | Unknown | 66 |

| Cheilocostus speciosus (JKeonig) CDSpecht | Costaceae | Keu, Chengalva kostu | Rz | Unknown | 95 |

| Chlorophytum laxum R Br | Liliaceae | Neerootikizangu | Tb | Tuber paste applied on affected area | 89 |

| Cissampelos pareira Linn | Menispermaceae | Patha, Patindu, Batindu, Patha, Urikkakodi, Chokipar, Tijumala, Ekladi Poa | Tb, Rt | Root paste with long pepper is prescribed once daily for 5 d | 92, 93, 96 |

| Citrullus colocynthis (Linn) Schrad | Cucurbitaceae | Kadva inravarna, Tumba, Gadumba, Tumbo, Indrayan | Sd, Rt, Fr | Seed oil used externally, as well as root crushed and given to drink | 33, 38 |

| Clematis triloba Linn | Ranunculaceae | Badarsiti, Jangali, Bhoda, Bendar, Siti | Rt | Root paste is applied | 77 |

| Cleome gynandra Linn | Cleomaceae | Hul-hul | Lv, Wp | Unknown | 39 |

| Cleome viscose Linn | Capparidaceae | Nayivelai | Lv | Leaf paste applied externally | 30 |

| Clerodendron inerme Gaertn | Verbenaceae | Vishaparihari | Rt | Root paste mixed with lime is applied twice daily for a week | 81 |

| Clitoria ternatea Linn | Fabaceae | Ruhu tuhu, Aparajita, Syahiful, Aparajita, Gokarni, Aparajita, Bili, Shankhapushpa | R | The root extract is taken with the root of Aristolochia indica and Rauwolfia serpentine | 39, 87 |

| Cocculus villosus DC | Menispermaceae | Nagdun, Vachan karalla | Rt | The root bark extract is given internally and applied | 3, 38 |

| Commelina bengalensis Linn | Commelinaceae | Kana simolu | R | Roots are useful | 53 |

| Corallocarpus epigaeus (Rottl & Willd) Hook f | Cucurbitaceae | Aathalai, Marsikand, Kollan, Kova killangu | Rt, Tb | Root decoction given internally 3–7 times | 64, 68, 97 |

| Costus speciosus (Koen) Sm | Costaceae | Keon, Kanda, Kebuk, Mahalakri, Jamlakhuti, Pewa, Jamlakhuti, Khongbam, Takhelei, Sumbul, Jomalkhuti, Myonpobap | Rt, Rz | Rhizome and root paste is used internally & externally | 58, 60, 80, 87 |

| Crateva magna (Lour) DC | Capparaceae | Jong-sia | Br | Chewed and applied on bitten area | 80 |

| Curculigo orchioide Gaertn | Amaryllidaceae | Nilapanai, Nela tengu, Kali musli | Rt, Tb | Root paste use topicaly | 39, 80, 81 |

| Curcuma amada Roxb | Zingiberaceae | Amba haldi | Rz | The powder of the rhizome is applied locally | 84 |

| Curcuma aromatica Salisb | Zingiberaceae | Bon haladhi, Lam-yaingang | Rz | Paste of rhizome taken with water | 58 |

| Curcuma caesia Roxb | Zingiberaceae | Kalahalud, Kalahaldi krushna kedara, Neelkanth | Rz | The dried rhizome powder is mixed with powdered seeds of Andrographis paniculata and applied | 34, 58 |

| Cyathula tomentosa Roth | Amaranthaceae | – | Lv | Unknown | 79 |

| Cyphostemma auriculatum (Roxb) Singh & Shetty | Vitaceae | Kali-vel | Br | Bark is taken in some water and taken once a day (7–8 d) | 96 |

| Daemia extensa RBr | Asclepiadaceae | Vaelipparuththi | Rt | Powder of root is given | 90 |

| Datura metel Linn | Solanaceae | Kala Dhatura, Dhutura | Sd, Rt, Lv | Extract of roots are taken with garlic | 39, 70, 80, 81 |

| Delphinium denudatum Wall ex Hook f & Thomson | Ranunculaceae | Nirbishi | Rt | Unkown | 41 |

| Desmodium gangeticum (Linn) DC | Fabaceae | Kareti, Salparni | R | Half-cup root decoction is taken orally | 39, 60 |

| Dichrostachys cinerea Linn Wight & Arn | Araceae | Vedathalai, Kheri | Lv, Rt | Root powder is used Leaves are crushed into paste and applied locally |

54 |

| Dicliptera paniculata (Forssk) IDarbysh | Acanthaceae | Chebeera | Wp | Unknown | 95 |

| Dioscorea pentaphylla Linn | Dioscoreaceae | Lalvala vahrikand | Tb | Extract is also given | 60 |

| Dregea volubilis (Lf) BenthEx Hookf | Apocynaceae | Dudipala, Bandi gurija | Lv | Unknown | 95, 96 |

| Drymaria cordata (L) Willd Ex Roem & Schult | Caryophyllaceae | Mecanachil, Theiphelwang, Kynbat thalap | Wp | Whole plant is used (crushed paste applied) | 80 |

| Dryopteris cochleata CChr | Aspidiaceae | Chhoti Bhulan | Wp, Lv, R | The whole plant crushed in a bowl and the extract is given orally twice a day The leaves and roots are applied on the bite wound |

43 |

| Eclipta alba (Linn) Hassk | Asteraceae | Manchal karisalankanni, Bhringraj, Maka | Wp | Whole plant juice is given orally (30 d) | 38 |

| Elaeodendron glaucum Pers | Celastraceae | Ratangaur, Bhairao, Niuri Mamri, Jamrasi Mukarthi (Bhutphal) | Br, Rt | Roots and bark of plant made into paste taken orally with cow's milk | 62 |

| Elettaria cardamomum Maton | Zingiberaceae | Elassi | Sd, Pd | Decoction | 58 |

| Eleusine indica (L) Gaertn | Poaceae | Malkantari-Mundari | Rt | 20 g root is crushed along with 10 g Zingiber officinale and nine black pepper pieces; paste is divided into two equal parts One part with a few drops of honey is administered orally and the other part is applied on the snake bitten area | 92 |

| Enicostemma axillare (Lam) A Raynal | Gentianaceae | Vellarugu | Rt | 5–10 drops of root extract is poured in the spot | 91 |

| Ervatamia coronaria Stapf | Apocynaceae | – | Rt, Br | Root and bark infusion mixed with milk and butter, filtered, and used | 99 |

| Ervatamia heyneana Cooke | Apocynaceae | Kadunandibattalu | Rt | Root paste mixed with lemon juice & applied | 81 |

| Euphorbia neriifolia Linn | Euphorbiaceae | Mausa sij, Dudhbol, Thor, Thundar, Manasa | Lx, Rt | Latex is applied locally Root is used with black pepper |

54, 80 |

| Ficus benghalensis Linn | Moraceae | Badd, Bar, Bargad | Lx, Ap, Rt, Fr | Unknown | 38 |

| Ficus glomerata Roxb | Moraceae | Medi | St, Br | The stem bark paste is applied | 31 |

| Ficus hirta Vahl | Moraceae | Tamangaddu | Rt | Root crushed & rubbed | 47 |

| Ficus racemosa Linn | Moraceae | Gular | Br | The stem bark is pounded with whey and applied locally | 54 |

| Ficus religiosa Linn | Moraceae | Peepal | Lv, Br, Fr | 25 g stem bark and 8–10 cloves are pounded with animal fat (pure ghee) and given 4–6 times a day | 35, 37, 59 |

| Ficus tinctoria Forstf | Moraceae | Tella barnika | Lv | Unknown | 31 |

| Fimbristylis spathacea Roth | Cyperaceae | Hathia | Rt | The fresh root is taken internally & externally | 87 |

| Gloriosa superb Linn | Liliaceae | Vadhavadiyo, Vach, Nag, Nagardi, Gowri, Huvu, Kalihari, Kalihari, Karianaga, Agnishikha, Kariyari, Kalappa, Kilangu | Tb, Rt, Rz, Sd | Root paste or tuber paste is applied externally (2–5 d) | 38, 39, 81, 82 |

| Habenaria commelinifolia Wall | Orchidaceae | Ankra | Tb | The tuber paste is applied | 59 |

| Hedychium spicatum SM | Zingiberaceae | Aithur, Takhellei-hanggam-mapan | Rz, Rt | Root decoction is used | 58 |

| Helicteres isora Linn | Sterculiaceae | Hateri, Murud sheng, Maror Phali | Br, Rt | Bark power is given in snakebite | 39, 57 |

| Heliotropium indicum Linn | Boraginaceae | Nakkipoo | Lv | The leaf juice mixed with hot water is used | 75 |

| Heliotropium marifolium Koen ex Retz | Boraginaceae | Choti-santri | Wp | Unknown | 82 |

| Heliotropium supinum Linn | Boraginaceae | Goma | Ap | Pounded aerial portions are applied externally and its juice is given orally in a dose of 5 mL at frequent intervals | 35 |

| Hemidesmus indicus (Linn) R Br | Asclepiadaceae | Suganti Jad, Anantmul, Choti dudhia, Anantamul, Analsing, Nannari, Anantamul | Rt, Lv | Aqueous extract of root is prepared in water and given orally & root paste is applied two or three times a day | 92, 93 |

| Heteropogon contortus (Linn) P Beauv | Poaceae | Lapia, Lapida, Soorwala | Rt | Root paste is taken orally Poultice of root paste is also applied on the bitten portion for early cure | 60 |

| Holarrhena pubescens (Buch-Ham)Wall ex GDon | Apocynaceae | Pandhara Kula, Bolmatra | Sd, Rt, St, Br | Paste is applied on the bitten area two times a day | 80 |

| Hordeum vulgare Linn | Poaceae | Jau, Jav | Gr | Unknown | 54 |

| Hyptis suaveolens (Linn) Poit | Lamiaceae | Ban Tulsi | R | Unkown | 39 |

| Impatiens glandulifera Royle | Balsaminaceae | Hillu | Fls | Unknown | 83 |

| Ipomoea obscura (L) Ker Gawler | Convolvulaceae | Siruthaalikkodi | Lv | Leaf juice is administered | 91 |

| Jatropha gossipifolia Linn | Euphorbiaceae | Kattamanakku | Lv, St, Br, Sd, Lx | Unkown | 55 |

| Kyllinga monocephala Rottb | Cyperaceae | Safad, Nirbashi | Un | Unknown | 38 |

| Lantana camara Linn | Verbenaceae | Ragadd, Gajukampa, Arippu | R, Fl, St, Lv, Wp | Decoction of roots, flower, and stem are used | 75 |

| Leucas aspera Spreng | Lamiaceae | Durum bon, Gumma, Bhodaki, Tumbe, Thumbai, Gadde tumbe, Thumbi, Thumbai, Kennathumbai | Wp, Lv, Rt | Leaf paste or crushed leaf is taken both externally & internally to treat The root juice is mixed with goat's milk three times a day (4 d) |

73, 75, 81, 90, 99, 100 |

| Leucas cephalotes (Roth) Spreng | Lamiaceae | Goma, Gumbi, Gumma | Wp | Decoction of whole plant (twice a day for 6 d) | 38, 39 |

| Lindenbergia muraria (Roxb) Brühl | Scrophulariaceae | Chatti | Wp | Paste of leaf is applied externally | 82 |

| Lobelia nicotianaefolia Heyne | Campanulaceae | Heddumbe, Kadu hogesoppu | Lv, Lx | Latex is applied externally | 81, 100 |

| Luffa acutangula (Linn) Roxb | Cucurbitaceae | Torai, Peerkan, Jangli Torai | Fr, Tn, Sd | Tendrils & seed paste is used | 39, 90 |

| Malva sylvestris Linn | Malvaceae | Bendi gida | Lv | Extract of leaf mixed with lime juice given | 99 |

| Martynia annua Linn | Martyniaceae | Bagnakha | Rt | Decoction | 67 |

| Mimosa pudica Linn | Mimosaceae | Lajwanti, Thotta, Sinungi, Uskadpoda, Chhuimui/Lajwanti, Thottal surungi, Thottalvadi, Thottasiniki | Rt, Lv, Wp | Whole plants are made into extract in drinking water and shaken well and filtered Extract of whole plant is given twice a day for one day only Leaves are ground and made into paste and applied over affected area |

31, 39, 47, 90 |

| Mirabilis jalapa Linn | Nyctaginaceae | Jahai juhi | Tb | The solution of tuber paste is given orally | 62 |

| Mitragyna parvifolia (Roxb) Korth | Rubiaceae | Neer-kadamba, Kadamba | Br, Fr | Unknown | 57 |

| Momordica charantia Linn | Cucurbitaceae | Karela, Pakakai | Wp, Sh, Rt | Juice of tender shoot or root is applied | 42 |

| Momordica dioica Roxb Ex Willd | Cucurbitaceae | Kakoda, Kankoda, Madi hagala kayi | Rt | Root tuber pounded with lime is applied externally on bitten spot daily thrice for 7 d | 81, 82 |

| Moringa oleifera Lam | Moringaceae | Sajina, Nugge, Sahigan, Mungna, Sainjna, Sahjan, Sainjnad, Murungaih | Rt, Sd, Wp, St, Br, Lv | Fresh extract of bark is taken orally Bark root tincture apllied externally (3 d) |

3, 54 |

| Mucuna pruriens (Linn) DC | Fabaceae | Kevach, Konch | Sd, Fr, Rt | Aqueous extract of root is given orally twice a day | 39 |

| Musa paradisiaca Linn | Musaceae | Vazhai, Valaimaram, Valai | Br, St, skin, Br | A plant extract is given orally | 30, 68 |

| Nerium indicum Mill Gard | Apocynaceae | Kaner, Kaner/Kanail, Lal kanher | Lv, Br Rt | The root is crushed with roots of Capparis sepiaria and Datura innoxia and paste applied externally thrice for 5 d | 39, 54 |

| Nymphoides hydrophylla O Kuntze | Menyanthaceae | – | Lv | Leaf paste is used | 52 |

| Ochna obtusata DC | Ochnaceae | – | Rt | Powder of root drunk with hot water frequently | 80 |

| Ocimum adscendens Wild | Lamiaceae | Heddumbe | Rt | Unknown | 99 |

| Ocimum basilicum Linn | Lamiaceae | Naitulasi, Kali Tulsi | Wp | Whole plant decoction orally given (week) | 39 |

| Ocimum sanctum Linn | Lamiaceae | Barpai, Tulasi | Lv, Rt, Wp | A paste of Ocimum leaf with the rhizome of Curcuma longa L (Zingiberaceae) is applied externally Leaf juice oral (8 d) |

3, 38, 51 |

| Ophiorrhiza mungos Linn | Rubiaceae | Havina gedde, Pambupoo, Keeripundu | Rt | Root juice is given (twice a day for 6 d | 61, 98 |

| Opuntia dillenii (Ker-Gawl) Haw | Cactaceae | Sappathikali | St, Br, Fr, Wp | The fruit paste is applied | 75 |

| Ottelia alismoides (L) Pers | Verbenaceae | – | Lv | Unknown | 57 |

| Oxalis debilis HBK var corymbosa (DC) Lour O martiana Zucc | Oxalidaceae | Khatti Booti | Wp | Unknown | 39 |

| Pandanus nepalensis St John | Pandanaceae | – | Lv | Unknown | 42 |

| Parnassia nubicola Wall ex Royle | Parnassiaceae | – | Tbs, Rt | Unknown | 79 |

| Pavetta indica Linn | Rubiaceae | Therani | Lv | A leaf paste is used externally | 68 |

| Pergularia daemia (Forrsk)Chiov | Apocynaceae | Veliparuthi | Rt, Lv | The decoction of the leaves is used | 30, 75, 95 |

| Peucedanum anamallayense Cl | Apiaceae | Padachurukki | Wp | Whole plant paste along with cow's urine is taken | 48 |

| Phyllanthus acidus (Linn) Skeels | Euphorbiaceae | Kawlsunhlu | Rt | Decoction of roots is given | 78 |

| Piper nigrum Linn | Piperaceae | Bolkaalu, Menasina kaalu, Maricha, Kali-mirch, Milagu | Fl, Sd, Fr | Seed powder mixed with butter is given orally against snakebite Flower paste with ghee given orally (4 d) |

3, 54 |

| Pistia stratiotes Linn | Araceae | Jalkumbhi | Sd | Decoction of seeds is given | 67 |

| Pittosporum tetraspermum Wight & Arn | Pittosporaceae | Analivegam | St, Br | Paste of stem bark is taken with cow's urine | 48, 66 |

| Plantago erosa Wall | Plantaginaceae | Chhakur-blang | Lv | Poultice of the leaves is given | 80 |

| Platanthera susannae Lindl | Orchidaceae | Nela site huvu | Rt | In combination with lime and salt, the paste of root tubers is applied on the affected area | 81 |

| Pouzolzia indica Gaud | Urticaceae | Dudhmor | Wp | Unknown | 53 |

| Prosopis cineraria Druce | Fabaceae | Khejdi, Vanni maram | Br | Paste of bark tied on the affected area | 71 |

| Quercus leucotrichophora A Camus | Fagaceae | Banj | Sd | Unknown | 41 |

| Randia dumetorum (Retz) Poiret Linn | Rubiaceae | Kaare | Rt | Paste with water The root of this plant and leaves of Acacia suma (Mimosaceae) are pounded with salt and applied externally |

81 |

| Rauvolfia serpentina (Linn) Benth ex Kurz | Apocynaceae | Nagbel, Bhuin karuan, Patal-garuda, Bhuikurma, Sarpagandha, Keramaddinagaddi, Sutranabhi, Sarpagandha lairusich, Sarpagandha | Lv, Rt | Leave juice used as antidote Roots and leaf buds crushed with milk to make into paste used both internally and externally on affected area |

34, 39, 43, 62, 76, 99 |

| Rhinacanthus nasutus (L) Kurz | Acanthaceae | Nagamalli | Lv | Fresh leaves are taken orally, as well as the paste of the leaf applied externally | 49, 61 |

| Rivea hypocrateriformis (Desr) Choisy | Convolvulaceae | Parh | Wp, Rt | The plant juice/paste is orally taken | 95, 96 |

| Rubus niveus Thunb | Rosaceae | – | Fr | Unknown | 79 |

| Ruta graveolense Linn | Rutaceae | Nagadali | Rt | Root paste is used | 99 |

| Sanseveria roxbhurgiana Schultes F | Agavaceae | Saganaara, Gaju kura | Rt | Tuberous root paste is applied on the area of snakebite | 97 |

| Saraca asoca (Roxb) De Wilde | Ceasalpiniaceae | Ashok, Asoka | Sd | Unknown | 40 |

| Sauromatum venosum (Ait) Kunth | Araceae | Halida, Samp ki dawa | Tb | The paste of tuber is applied on the affected area | 33, 84 |

| Saussurea costus (Falc) Lipsch | Asteraceae | Kuth | Rt | Unknown | 41 |

| Sesamum indicum Linn | Pedaliaceae | Til | Sd | Seeds are mixed with butter, ginger powder, and oil and given orally | 54 |

| Sida acuta Burm | Malvaceae | – | Wp | The whole plant extract is given internally and applied externally | 3 |

| Sida caprinifolia Linn | Malvaceae | Arivaal mania poondu | Lv | Leaf paste is used | 90 |

| Sida cordifolia Linn | Malvaceae | Kungyi | Wp | Unknown | 82 |

| Solanum nigrum Linn | Solanaceae | Makoi | Rt | Paste of dried root is applied | 54 |

| Solanum xanthocarpum Schard & Wendl | Solanceae | Bhui ringani, Bhat kataiyan, Choti kateli | Lv, Rt | Fresh leaf extract (paste or decoction) of this species is given | 101 |

| Soymida febrifuga A Juss | Meliaceae | Rohina | St, Br, Br, Rt | Fresh bark of this plant together with root of Holarrhena pubescens (1:1) are made into paste and mixed with drinking water given orally three times a day for 3 d | 31 |

| Sterculia urens Roxb | Sterculiaceae | Karaya | Br | Unknown | 60 |

| Strychnos nux-vomica Linn | Loganiaceae | Kajara, Kaasarka, Kanjiram, Vishamushti, Etti, Visakkotai, Yeti | Rt, Sd | Root bark juice in cow's milk is externally rubbed 3–4 times a day to treat The seed powder is also used |

89 |

| Strychnos potatorum Linn | Leguminoceae | Thethamkottai | Sd | Seed powder given orally | 49 |

| Tabernaemontana coronaria RBr | Apocynaceae | Nandibattalu huvu | Rt | The crushed root mixed with salt and turmeric is applied | 81 |

| Tabernaemontana divaricata (Linn) RBr | Apocynaceae | Nanjatte, Maddarasa, Kathona, Amli, Tengtere, Tetul | Rt, Lv Sd | The extract of the seed is given, as well as crushed paste applied on bitten area | 80 |

| Tamarindus indica Linn | Caesalpiniaceae | Puli | Sd, Rt | Unknown | 51, 55 |

| Tectona grandis Linn | Verbenaceae | Sagwan | Lv, Br | Unknown | 44 |

| Terminalia arjuna (DC) Wight & Arn | Combertaceae | Arjun, Marutham, Vellamarthu | Br | Bark paste applied externally (5 d) | 45 |

| Thottea siliquosa (lamk) Ding Hou | Aristolochiaceae | Kuttalvayana, Padamchurukkialpam, Kuttilavayana | Rt, Lv | Roots and leaves decoction are given orally | 66, 89 |

| Tiliacora acuminata (Lamk) Miers | Menispermaceae | Kappa teega | Lv | Leaf paste is applied on the affected area | 31 |

| Trewia nudiflora Linn | Euphorbiaceae | Panigambhar | Br | Pounded bark is taken internally | 88 |

| Trichisanthes cucumerina Linn | Cucurbitaceae | Nagfani beldi | Tb | Powder of tuber is applied locally | 84 |

| Tridax procumbens Linn | Asteraceae | Munya arxa, Dagad Ful | Lv | The leaves are crushed and the juice is dripped on the wound of snakebite Juice is taken orally after its dilution with some quanty of water |

62, 76 |

| Tylophora indica (Burm f) Merr | Asclepiadaceae | Nangilai, Asthamakodi | Lv, Rt | Paste of leaf and root is mixed with equal amount of root paste of Rauvolfia serpentina and applied externally on the spot, as well as leaf juice alone taken internally | 31, 63, 65 |

| Urginea indica (Roxb) Kunth | Liliaceae | Koliknada | Cm | Half of the corm is ground with some quantity of black pepper seeds & animal fat (pure ghee) and given in three doses within a day | 35 |

| Ventilago maderaspatana Gaertn | Rhamnaceae | Rakta pichula | Br | The infusion of bark is given orally | 43 |

| Vitex negundo Linn | Verbenaceae | Nukki, Lakkigida, Karinochi notchi, Nishindi, Shet nishinda | Br, Rt, Lv, Sd | Leaf paste applied over the bitten area (5 d), as well as root extract is given with warm water | 81 |

| Vitex penduncularis Wall | Verbenaceae | Charaigorh | Br | Decoction of the bark is given orally at 30 min intervals | 62, 88 |

| Zingiber rubens Roxb | Zingiberaceae | Pauphok | Lv | The leaves are torn into thin strips and rope is made that is used to tie up parts of snakebite to prevent flow of venom in blood | 45 |

Abbreviations used – Ap, arial portion; Bb, bulb; Bd, bud; Br, bark; Cm, corm; Fl, flower; Fr, fruit; Gr, grain; Gu, gum; Lv, leaves; Lx, latex; Pd, pods; Pl, poultice; Pn, penduncle; Re, resin; Rt, root; Rz, rhizomes; Sd, seeds; Sh, shoot; St, stem; Tb, tuber; Tn, tendril; Un, unknown; Wp, whole plant; d, day(s); h, hour(s).

3. The Indian subcontinent and snakes

The Republic of India (3rd largest country in Asia and 7th by area in world) is a multilingual country home to a diverse culture with a rich and glorious heritage. India's land border covers 151,067 km, which is shared with neighboring countries, including Bangladesh (border shared = 40,967 km), China (3488 km), Pakistan (3323 km), Nepal (1751 km), Myanmar (1643 km), Bhutan (699 km), and Afghanistan (106 km). India's coastline covers 75,166 km, and land area including island territories covers more than 3,287,260 km2. Some of these countries were part of India before the partition.4

India has numerous and diverse medico-herbal plants. They are dispersed, depending upon geographical and ecological conditions, across the country. Of these, more than 1500 species have demonstrated significant medicinal properties.4 Envenomation, especially by snakebite, is a serious worldwide public health crisis.5, 6, 7, 8 Inappropriate and unwarranted treatment results from reasons such as the failure to identify the snake species (venomous or non-venomous), which increases the risk of complications. According to the Integrated Taxonomic Information System (ITIS), Elapidae and Viperidae are the two major families of venomous snakes. Elapidae consists of 325 species distributed in 61 genera. Viperidae includes 224 species distributed in 22 genera. In and around India, approximately 216 species of snakes belong to these families, and only 52 are known to be poisonous.9, 10 The ‘Big Four’ snakes cause the largest number of snakebite deaths on the Indian subcontinent. The ‘Big Four’ snakes consist of Russell's viper (Daboia russelii; Marathi translation, ghonas tawarya), Indian cobra (Naja naja; Marathi translation, Nag), saw-scaled viper (Echis carinatus; Marathi translation, phoorsa), and common krait (Bungarus caeruleus; Marathi translation, manyar kanadar) (Fig. 1).11 Apart from these big four, the hump-nosed viper is also hazardous.12 Envenomation is a ‘choice’ and voluntary action or reaction by snakes. Their bite is a natural protective defense mechanism. All venomous snakes have the ability to bite without including venom (dry bite).13 Farmers, fieldsmen, and outdoor workers find suffering from snakebites to be an occupational hazard.14 It is also a leading problem in rural areas of India. It is estimated that snakebite poisoning causes approximately 50,000 deaths annually, and the number is likely higher because not all cases from rural areas are reported.10, 15

Fig. 1.

Big Four Russell's viper (Daboia russelii, Marathi – ghonas, tawarya), Indian cobra (Naja naja, Marathi – Nag), saw-scaled viper (Echis carinatus, Marathi – phoorsa), and the common krait (Bungarus caerules, Marathi – manyar, kanadar). Images reprinted with permission from indiansnakes.org.

4. Snake venom and snake anti-venoms

Snake venom is one of the most intense and ‘mysterious’ biological fluids within the animal kingdom, causing complex medical effects. This is because of the presence of complex mixtures of proteins, peptides, and contain at least 25 enzymes.16, 17 Venom is a complicated combination of proteins (both enzymatic and non-enzymatic), peptides, and small organic compounds, such as acetylcholine citrate and nucleoside.18, 19 There are many potential effects of snake envenomation on humans; however, a few broad categories of major clinical significance are:

-

1.

Systemic myolysis

-

2.

Flaccid (drooping) paralysis

-

3.

Coagulopathy and hemorrhage

-

4.

Cardiotoxicity

-

5.

Renal damage or failure

-

6.

Local tissue injury at the bite site

Each of these may cause a number of secondary effects, and each is associated with potential morbidity and mortality.3 Similar to other modern medicines, anti-venom can have side effects. In addition, it takes too long to develop and is expensive. Strict and specific conditions are required for long-term storage.10 Because of the lack of availability of antidotes and anti-venoms at any specific time, alternatives from plant sources (which are abundant) should developed. Adequate information about herbal preparations or formulations is needed. The Indian system of medicine, especially Ayurveda medicine, has thrown light on this subject. A variety of plants mentioned in Ayurvedic literature are useful in snakebite treatment.20 Considering that treatment at a proper clinic or hospital is at an unreachable distance for approximately 80% of victims, these people are primarily treated or handled by a traditional practitioner, or Vaidya, or other tribal herbalist. If the situation is beyond their control, they must proceed to a nearby clinic or hospital for advanced therapy.8 The traditional practitioners rely on various plants for treatment because they are knowledgeable about a variety of plant species that are helpful against snakebites and associated complications.3, 21 In the management of snakebites, there are two main aspects:

-

1.

Proper first aid treatment and

-

2.

Anti-venom/anti-ophidian treatment, such as serum therapy

Because of side effects or adverse events (e.g., anaphylactic reactions), serum sickness and sometimes the anti-venom itself produces complications during treatment.22

5. Diversity of India

World Health Organization (WHO) stated that almost 80% of the population in developing countries depend on various herbal plants for the management of diverse diseases and illnesses because of the lack of modern health care services.3, 23 In addition, for prime health care, people are dependent on their earnings and improvement of the standard of living. More than 65,000 plant species are traditionally used in addition to modern medicines.24 In India, Ayurveda is the most widely practiced system of medicine, which has a marvelous diversity of plant information. The Republic of India has 29 states and seven union territories comprising an area of 3,287,263 km2. The Indian people speak a variety of languages, including 23 regional languages: Assamese, Bengali, Bodo, Dogri, Gujrathi, Kannada, Kashiri, Kokborok, Konkani, Maithili, Malayalam, Manipuri, Marathi, Mizo, Nepali, Odia, Punjabi, Sanskrit, Santali, Sindhi, Tamil, Telugu, and Urdu. Apart from these, other local or tribal people have their own tribal or native language per locality. India encompasses different ethnic groups with over 539 core indigenous people living in diverse territories. It has varied cultures, foods, traditions, and religious rituals, which causes separations among the people. Furthermore, there is a wealth of knowledge of conventional medicine, particularly herbal and folk medicine, for treatment of snakebites.

6. Clinical significance of snakebite

Traditional herbalists treat people earlier and use plants to cure various complications and ailments.3 The snake is still not perfectly understood to worldwide researchers. The word ‘snake’ invokes feelings of fear because of an instinctive human emotion and its image is powerful and primal. Snakes are as fascinating to psychologists, pharmacologists, and clinicians as they are to evolutionists. Snakes are either poisonous or nonpoisonous. Snakebites can be considered as environmental or occupational hazard because they occur regularly and repeatedly, with overwhelming frequency, particularly in remote rural areas in tropical developing nations. It is estimated that each year in India there are more than 80,000 snake envenoming and 11,000 deaths, which makes India a seriously affected nation. Snakes are present on each continent, except Antarctica.9 Mishal et al listed some critical and medically significant (clinical) conditions and syndromes related to snakebite envenomation14 as follows:

-

1.

Local or restricted area envenoming (swelling of the affected part) with hemorrhage or difficulty clotting (this is particularly seen in Viperidae envenomation).

-

2.

Local or restricted area envenoming (viz. swelling) with hemorrhage or difficulty clotting damages the kidneys or contributes to infections that cause neuro-paralysis and shock.

-

3.

Local or restricted area envenoming (such as swelling) along with paralysis.

-

4.

Paralysis with/without local or restricted area envenoming.

-

5.

Paralysis with urine that is dark brown in color in addition to acute kidney injury.

7. Composition of snake venom

Medical science occasionally ignores community health values. Snake venom is rich in protein and peptide toxins. These proteins have a definite action on numerous tissue receptors. The wide range of action of snake venoms makes them clinically demanding and scientifically interesting, in particular, for drug design.25 The mysterious biological nature of venom and its complex medical effects have long captured human imagination and inquisitiveness. Venoms, mainly snake venoms, have been the focus of ancient mythology, early biomedical speculation, folklore, and scientific investigation, in addition to pharmacognosy.24 The venom of any species may have more than 100 diverse toxic and non-toxic proteins and peptides, along with non-protein toxins (amines, carbohydrates, lipids, and additional small molecules).25 Proteins and peptides comprise approximately 90 ± 05% of the dry weight of venom. Supplementary components in the venom consist of carbohydrates, metallic cations, nucleosides, biogenic amines, and a small amount of free amino acids and lipids. The venom of snakes contains at least 25 enzymes, although no single snake venom has all of them. Enzymes are responsible for catalyzing numerous precise biochemical reactions that occur in living matter. They are the mediators upon which cellular metabolism depend. Among the available choices, the more important snake venom enzymes are as follows: 5′-nucleotidase, acetylcholinesterase, arginine ester hydrolase, collagenase, DNase, hyaluronidase, lactate dehydrogenase, l-amino acid oxidase, NAD nucleosidase, phosphodiesterase, phospholipase A2 (A), phospholipase B, phospholipase C, phosphomonoesterase, proteolytic enzymes, RNase, and thrombin-like enzymes. All these enzymes are not present in all venoms. Among the peptides originating in snake venoms are pre-synaptic and postsynaptic neurotoxins, myotoxins, cytotoxins, cardiotoxins, and potassium channel-binding neurotoxins, along with platelet aggregation inhibitors (disinterring).3, 26, 27

8. Snakebite treatment in India

Because India is the only country of its kind in terms of the diversity of geographical, environmental, and climatic features, it has a rich and wide-ranging flora of medicinal herbal plants that have been used since the Vedic period. A huge portion of the nation still uses plants as home remedies in rural and remote areas for a number of illness, infections, and diseases, including snakebites. India is a nation with mega diversity; moreover, approximately 10% of world's species are indigenous to India. Because India has a prosperous, flourishing, enlightening legacy, almost all Indians have directly and indirectly been connected with a variety of herbs during their ritualistic ceremonies and various cultural activities. A recent study found that rich ethno-medicinal knowledge could be gathered from the community members, which would provide a great advantage to future generations by documenting and preserving the knowledge. This requires that the ethno-medicinal plants used by the native tribal people should be comprehensively revised and the proper significance of these plant species assigned, such that they can be managed and conserved for the welfare of mankind.3 Reliable progress has been made in that direction. Snakebite treatment in India (before partition) consisted of various snake antivenom drugs and/or combination formulations, such as Surucuina (1908), Ofidina (1909), Viborina (1910), an unknown plant used by the Civil Surgeon of Hugli (1912), an ointment made by Mr M Robert of Bordeaux (1914), Goor Boinchee Antitoxicum (1915), Tiriyaq (1916, repeated in 1929), white champa pod and root (1920), Payam-i-Hayat (February 14, 1921), El Elixir Antiviperino Lexin (1923), remedy by firozuddin (June 1928), and lobelin (1929) that have been tested since 1908 in various pharmacological labs across India, then British India and the Indian subcontinent.28 The severity of snakebite poisoning is always a catastrophic issue for the sufferer and physician. Usually death will result because of many reasons, such as failure of the patient to reach the hospital, lack of appropriate treatment, difficulty in production, deployment, and accessibility of current snake anti-venoms. The mortality rate depends largely on the species of snake. Elapid poisoning (viz. cobra and krait) always has a higher mortality rate than that of Viperidae poisoning (saw-scaled viper and Russell's viper). The point to be considered is that an approximately 70-kg healthy person will succumb to only a small quantity of venom, and typically it takes the venom 6 seconds or less to reach the heart.14 In various ancient texts and literature, more than 320 medicinal plants and more than 180 different combinations are reported to have snake anti-venom activity. However, after comprehensive evaluation, all of these Ayurvedic preparations from medicinal plants had no snake anti-venom properties.28

9. Vaidya – Indian herbalist, physician, compounder and dispenser

In the Indian system of medicine, the Vaidya is known as doctor of herbs, who makes a diagnosis of illness and compounds medicinal preparations, such as asava, aristha, churna (powders), lotions, liniments, pills, syrup, and taila. Furthermore, many old-aged persons (such as a grandmother) are familiar with the application of various herbs. Practitioners of Ayurveda believe that every plant on the Earth has some significant medicinal property for the purpose of the good of the world; the right person just has to show you. The practitioner of Ayurveda states  (Naasti Moolam Anaushadhim

translation Every plant on earth has a medicinal property). Allopathy (the treatment of disease by conventional means, that is, with drugs having effects opposite to the symptoms) or modern medicinal systems sometimes has a number of undesired effects from drugs, such as adverse drugs reactions. Therefore, an increasing number of people in developed and developing countries are using medicinal plants for some betterment.3 The formulations or plant preparations rely on the availability of the plant part(s). Usually preparation is made by crushing the plant or its part(s) by using stones or pieces of wood. Often a juice or paste is made to apply to the affected area or sometimes is given orally. A number of villagers or Vaidya have a specific stone set called a “Paata-Varvantaa” (Fig. 2). The Paata is a Marathi language word meaning base on which the plant or its part(s) are kept. The Varvantaa is a Marathi language word meaning a pastel-like stone to crush the plants or its part(s). The present review is an attempt to cover the traditional/ethnobotanical medicinal plants utilized in various parts of India for snakebites. Apart from previous reviews, this will also help future researchers to recognize the herbal approach for the treatment of snakebites. In Table 1, the data from the current analysis is presented. Arrangement of medicinal plant species is in alphabetical order.

(Naasti Moolam Anaushadhim

translation Every plant on earth has a medicinal property). Allopathy (the treatment of disease by conventional means, that is, with drugs having effects opposite to the symptoms) or modern medicinal systems sometimes has a number of undesired effects from drugs, such as adverse drugs reactions. Therefore, an increasing number of people in developed and developing countries are using medicinal plants for some betterment.3 The formulations or plant preparations rely on the availability of the plant part(s). Usually preparation is made by crushing the plant or its part(s) by using stones or pieces of wood. Often a juice or paste is made to apply to the affected area or sometimes is given orally. A number of villagers or Vaidya have a specific stone set called a “Paata-Varvantaa” (Fig. 2). The Paata is a Marathi language word meaning base on which the plant or its part(s) are kept. The Varvantaa is a Marathi language word meaning a pastel-like stone to crush the plants or its part(s). The present review is an attempt to cover the traditional/ethnobotanical medicinal plants utilized in various parts of India for snakebites. Apart from previous reviews, this will also help future researchers to recognize the herbal approach for the treatment of snakebites. In Table 1, the data from the current analysis is presented. Arrangement of medicinal plant species is in alphabetical order.

Fig. 2.

Paata Varvanta, the traditional Indian mortal pestle (Google).

10. Conclusion

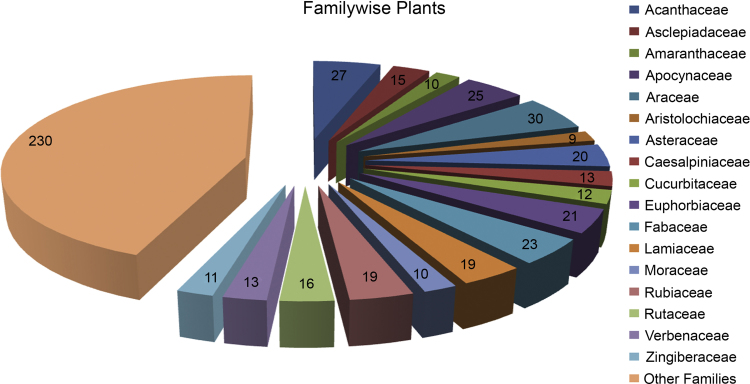

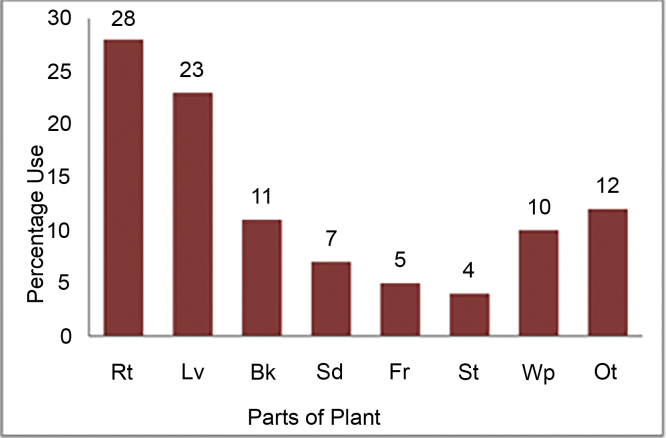

Mother Nature has given humans a most precious gift in medicinal plants. The natives of India are people who are very connected to Nature, as Indians are “celebration affectionate” people. In almost every festival in India, there is connectivity of human beings to animals and Mother Nature. The local tribes understand biodiversity and serve as a source of knowledge regarding proper use of medicinal plants. For various reasons, the focus altered from modern medicine to Ayurveda herbs and medicinal plants for various diseases or disorders. India is homeland for such a marvelous variety of diversity. In cultural heritage, India has a long history of medicinal plant utilization. This review has attempted to cover remarkable similarities among medicinal plants that are used across India. In our study, a total of 523 plant species belonging to 122 families were reported for treatment of snakebites. Furthermore, this review encompasses some plants that are rarely or less often used. The most common families include Acanthaceae, Apocynaceae, Arecaceae, Asteraceae, Caesalpiniaceae, Cucurbitaceae, Euphorbiaceae, Fabaceae, Lamiaceae, Rubiaceae, and Zingiberaceae (Fig. 3). For a long time, the traditional healers have practiced using herbal traditional medications for snakebite treatment, as well as numerous other diseases. Biological source(s), family, local name(s), part(s) used (Fig. 4), method of preparation, and reference(s) are provided to increase the ease of availability for the data.

Fig. 3.

Graphical representation showing number of plant according to various families (Upasani et al, 2017).

Fig. 4.

Plant parts used in treatment of Snake bite. (Upasani et al, 2017) (Rt, root; Lv, leaves; Bk, bark; Sd, seed; Fr, fruit; St, stem; Wp, whole plant; Ot, other parts).

There is a lot of information yet to be gathered and formulated. Ethno-botanical investigation is the future branch that will aid in maintaining good health for all mankind because much is still hidden and there are chances to make new phytochemical phytopharmacological drug discoveries, which will become the most reliable progression in the direction of utilization of medicinal plants for the treatment of various illnesses.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Sources of funding

Nil.

Acknowledgments

The authors are thankful to all relevant personnel from R C Patel Institute of Pharmaceutical Education and Research Shirpur, as well as R C Patel Institute of Pharmacy Shirpur for their help, encouragement, and occasional suggestions.The authors are very thankful to Jose Louies, Member – IUCN Viper Specialist Group and Founder of indiansnakes.org <http://indiansnakes.org/> & snakebiteinitiative.in <http://snakebiteinitiative.in/> and his team for providing high resolution images of Big four snakes.

References

- 1.Nasab F.K., Khosravi A.R. Ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants of Sirjan in Kerman Province Iran. J Ethnopharmacol. 2014;154:190–197. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2014.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ody P. Dorling Kindersley Limited; New York: 1993. The complex medicinal herbal. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Upasani S.V., Beldar V.G., Upasani M.S., Tatiya A.U., Surana S.J., Patil D.J. Ethnomedicinal plants used for snakebite in India: a brief overview. Integr Med Res. 2017;6:114–130. doi: 10.1016/j.imr.2017.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ministry of Home Affairs Government of India official website http://mhanicin/sites/upload_files/mha/files/bmintro-1011pdf. Published March 23, 2017. Updated March 23, 2017. Accessed March 23, 2017.

- 5.Kasturiratne A., Wickremasinghe A.R., de Silva N., Gunawardena K., Pathmeswaran A., Premaratna R. The global burden of snakebite: a literature analysis and modelling based on regional estimates of envenoming and deaths. PLoS Med. 2008;5:e218. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gutiérrez J.M., Theakston R.D.G., Warrell D.A. Confronting the neglected problem of snake bite envenoming: the need for a global partnership. PLoS Med. 2008;3:e150. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gutiérrez J.M., Williams D., Fan H.W. Snakebite envenoming from a global perspective: towards an integrated approach. Toxicon. 2008;56:1223–1235. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2009.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chippaux J.P. Snake-bites: appraisal of the global situation. Bull World Health Organ. 1998;76:515. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bawaskar H.S. Snake venoms and antivenoms: critical supply issues. J Assoc Phys India. 2008;52:11–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Meenatchisundaram S., Parameswari G., Subbaraj T., Michael A. Anti-venom activity of medicinal plants – a mini review. Ethnobotan Leaf. 2008;12:1218–1220. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Indian snakes on indiansnakes.org website (accessed 28.12.2015). Published March 23, 2017. Updated March 23, 2017. Accessed March 23, 2017.

- 12.Simpson I.D., Norris R.L. Snakes of medical importance in India: is the concept of the “Big 4” still relevant and useful? Wilderness Environ Med. 2007;18:2–9. doi: 10.1580/06-weme-co-023r1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Young B.A., Cynthia E.L., Kylle M.D. Do snakes meter venom? BioScience. 2002;12:1121–1126. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mishal H.B., Mishal R.H., Saudagar R.B. Focus on the various corridors of snake bite envenomation treatment – a review. Int J Curr Res Life Sci. 2015;4:492–498. [Google Scholar]

- 15.David A.W. WHO Regional Office for South East Asia; New Delhi: 2005. Guidelines for the clinical management of snakebite in the south East Asia region. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zelanis A., Tashima A.K. Unraveling snake venom complexity with ‘omics’ approaches: challenges and perspectives. Toxicon. 2005;87:131–134. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2014.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Markland F.S. Snake venoms and the hemostatic system. Toxicon. 1998;36:1749–1800. doi: 10.1016/s0041-0101(98)00126-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Elbey B., Baykal B., Yazgan U.C. The prognostic value of the neutrophil/lymphocyte ratio in patients with snake bites for clinical outcomes and complications. Saudi J Biol Sci. 2017;24:362–366. doi: 10.1016/j.sjbs.2015.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aird S.D. Ophidian envenomation strategies and the role of purines. Toxicon. 2002;40:335–393. doi: 10.1016/s0041-0101(01)00232-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kanojia A., Chaudhari K.S., Gothecha V.K. Medicinal plants active against snake envenomation. IJRAP. 2012;3:363–366. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mors W.B., DoNascimento M.C., Pereira B.M.R., Pereira N.A. Plant natural products active against snake bite – the molecular approach. Phytochemistry. 2000;55:627–642. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9422(00)00229-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lakshmi V., Lakshmi T. Antivenom activity of traditional herbal drugs: an update. Int Res J Pharm. 2000;4:1–3. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Calixto J.B. Twenty-five years of research on medicinal plants in Latin America: a personal review. J Ethnopharmacol. 2005;100:131–134. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2005.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Polat R., Satıl F. An ethnobotanical survey of medicinal plants in Edremit Gulf (Balıkesir – Turkey) J Ethnopharmacol. 2012;139:626–641. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2011.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Warrell D.A. Snake bite. Lancet. 2010;375:77–88. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61754-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stocker K. Composition of snake venoms. In: Stocker K.F., editor. Medical use of snake venom proteins. CRC Press; Boca Raton: 1990. pp. 33–56. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Niewiarowski S., McLane M.A., Kloczewiak M. Disintegrins and other naturally occurring antagonists of platelet brinogen receptors. Sem Hematol. 1994;31:289–300. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mhaskar K.S., Caius J.F. Indian Med Res Memoirs. 1931:1–96. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Guleria V., Vasishth A. Ethnobotanical uses of wild medicinal plants by Guddi and Gujjar Tribes of Himachal Pradesh. Ethnobotan Leaf. 2009;13:1158–1167. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Alagesaboopathi C. Ethnomedicinal plants used as medicine by the Kurumba Tribals in Pennagaram Region Dharmapuri District of Tamil Nadu India. Asian J Exp Biol Sci. 2011;2:140–142. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Krishna N.R., Varma Y.N., Saidulu C. Ethnobotanical studies of Adilabad District Andhra Pradesh. India J Pharmacognosy Phytochem. 2014;3:18–36. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kadhirvel K., Ramya S., Sathya Sudha T.P., Ravi A.V., Rajasekaran C., Selvi V.R. Ethnomedicinal survey on plants used by tribals in Chitteri Hills. Environ We Int J Sci Technol. 2010;5:35–46. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Meena K.L., Yadav B.L. Studies on ethnomedicinal plants conserved by Garasia tribes of Sirohi district Rajasthan India. Indian J Nat Prod Res. 2010;1:500–506. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Panda T., Padhy R.N. Ethnomedicinal plants used by tribes of Kalahandi district Orissa. Indian J Tradit Knowl. 2008;7:242–249. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Anis M., Sharma M.P., Iqbal M. Herbal ethnomedicine of the Gwalior forest division in Madhya Pradesh. India Pharm Biol. 2000;38:241–253. doi: 10.1076/1388-0209(200009)3841-AFT241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mallik B.K., Panda T., Padhy R.N. Ethnoveterinary practices of aborigine tribes in Odisha India. Asian Pacific J Trop Biomed. 2012;2:S1520–S1525. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Samar R., Shrivastava P.N., Jain M. Ethnobotanical study of traditional medicinal plants used by tribe of Guna District Madhya Pradesh India. Int J Curr Microbiol Appl Sci. 2015;4:466–471. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Panghal M., Arya V., Yadav S., Kumar S., Yadav J.P. Indigenous knowledge of medicinal plants used by Saperas community of Khetawas Jhajjar District Haryana India. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2010;6:1–11. doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-6-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Singh P.K., Kumar V., Tiwari R.K., Sharma A., Rao C.V., Singh R.H. Medico-ethnobotany of ‘chatara’ block of district sonebhadra Uttar Pradesh India. Adv Biol Res. 2010;4:65–80. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shiddamallayya N., Yasmeen A., Gopakumar K. Hundred common forest medicinal plants of Karnataka in primary healthcare. Indian J Tradit Knowl. 2010;9:90–95. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Phondani P.C., Maikhuri R.K., Kala C.P. Ethnoveterinary uses of medicinal plants among traditional herbal healers in Alaknanda catchment of Uttarakhand India. Afr J Tradit Complement Altern Med. 2010;7:195–206. doi: 10.4314/ajtcam.v7i3.54775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pradhan B.K., Badola H.K. Ethnomedicinal plant use by Lepcha tribe of Dzongu valley bordering Khangchendzonga Biosphere Reserve in north Sikkim India. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2008;4:1–18. doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-4-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rout S.D., Panda T., Mishra N. Ethno-medicinal plants used to cure different diseases by tribals of Mayurbhanj district of North Orissa. Ethno-med. 2009;3:27–32. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Harney N.V. Ethnomedicinal plants diversity of Bhadrawati Tahsil of Chandrapur District Maharashtra India. Int J Sci Res Publ. 2013;3:1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Choudhury S., Sharma P., Choudhury M.D., Sharma G.D. Ethnomedicinal plants used by Chorei tribes of Southern Assam North Eastern India. Asian Pacific J Trop Dis. 2012;2:141–147. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hazarika R., Abujam S.S., Neog B. Ethno medicinal studies of common plants of Assam and Manipur. Int J Pharm Biol Arch. 2012;3:809–815. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Choudhury P.R., Choudhury M.D., Ningthoujam S.S., Das D., Nath D., Das T.A. Ethnomedicinal plants used by traditional healers of North Tripura district Tripura North East India. J Ethnopharmacol. 2015;166:135–148. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2015.03.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Udayan P.S., George S., Tushar K.V., Bhalchandran I. Medicinal plants used by the Kaadar tribes of Sholayar forest Thrissur district Kerala. Indian J Tradit Knowl. 2005;4:159–163. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Karuppusamy S. Medicinal plants used by Paliyan tribes of Sirumalai hills of southern India. Nat Prod Rad. 2007;6:436–442. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bhatia H., Sharma Y.P., Manhas R.K., Kumar K. Ethnomedicinal plants used by the villagers of district Udhampur J&K India. J Ethnopharmacol. 2014;151:1005–1018. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2013.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Das A.K., Dutta B.K., Sharma G.D. Medicinal plants used by different tribes of Cachar district Assam. Indian J Tradit Knowl. 2008;7:446–454. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Swapna M.M., Prakashkumar R., Anoop K.P., Manju C.N., Rajith N.P. A review on the medicinal and edible aspects of aquatic and wetland plants of India. J Med Plants Res. 2011;5:7163–7176. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sikdar M., Dutta U. Traditional phytotherapy among the Nath people of Assam. Ethno Med. 2008;2:39–45. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Upadhyay B., Dhaker A.K., Kumar A. Ethnomedicinal and ethnopharmaco-statistical studies of Eastern Rajasthan India. J Ethnopharmacol. 2010;129:64–86. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2010.02.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rameshkumar S., Ramakritinan C.M. Floristic survey of traditional herbal medicinal plants for treatments of various diseases from coastal diversity in Pudhukkottai District Tamilnadu India. J Coastal Life Med. 2013;1:225–232. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sharma P., Rana J.C. Assessment of ethnomedicinal plants in Shivalik Hills of Northwest Himalaya India. Am J Ethnomed. 2014;1:186–205. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rao D.M., Rao U.V., Sudharshanam G. Ethno-medico-botanical studies from Rayalaseema region of southern Eastern Ghats Andhra Pradesh India. Ethnobotan Leaf. 2006;1:198–207. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Basak S., Sarma G.C., Rangan L. Ethnomedical uses of Zingiberaceous plants of Northeast India. J Ethnopharmacol. 2010;132:286–296. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2010.08.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Maheshwari J.K., Kalakoti B.S., Lal B. Ethnomedicine of Bhil tribe of Jhabua District MP. Anc Sci Life. 1986;5:255–261. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Jain A., Katewa S.S., Galav P.K., Sharma P. Medicinal plant diversity of Sitamata wildlife sanctuary Rajasthan India. J Ethnopharmacol. 2005;102:143–157. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2005.05.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kottaimuthu R. Ethnobotany of the Valaiyans of Karandamalai Dindigul District Tamil Nadu India. Ethnobotan Leaf. 2008;12:195–203. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Marandi R.R., Britto S.J. Ethnomedicinal plants used by the Oraon Tribals of Latehar District of Jharkhand India. Asian J Pharm Res. 2014;4:126–133. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ignacimuthu S., Ayyanar M. Ethnobotanical investigations among tribes in Madurai district of Tamil Nadu (India) J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2006;2:1–7. doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-2-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Rajendran S.M., Sekar K.C., Sundaresan V. Ethnomedicinal lore of Valaya tribals in Seithur Hills of Virudunagar district Tamil Nadu India. Indian J Tradit Knowl. 2002;1:59–71. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ignacimuthu S., Ayyanar M., Sivaraman S.K. Ethnobotanical investigations among tribes in Madurai District of Tamil Nadu (India) J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2006;2:56–63. doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-2-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Yesodharan K., Sujana K.A. Ethnomedicinal knowledge among Malamalasar tribe of Parambikulam wildlife sanctuary Kerala. Indian J Tradit Knowl. 2007;6:481–485. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Vijendra N., Kumar K.P. Traditional knowledge on ethno-medicinal uses prevailing in tribal pockets of Chhindwara and Betul Districts Madhya Pradesh India. Afr J Pharm Pharmacol. 2010;4:662–670. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ganesan S., Pandi N.R., Banumathy N. Ethnomedicinal survey of Alagarkoil Hills (Reserved forest) Tamil Nadu India. eJ Indian Med. 2008;1:1–18. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Udayan P.S., George S., Tushar K.V., Bhalchandran I. Medicinal plants used by the Malayali tribe of Servarayan Hills Yercad Salem District Tamil Nadu India. Zoos’ Print J. 2006;21:2223–2224. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Beverly C.D., Sudarsanam G. Ethnomedicinal plant knowledge and practice of people of Javadhu hills in Tamilnadu. Asian Pacific J Trop Biomed. 2011;1:79–81. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Bosco F.G., Arumugam R. Ethnobotany of irular tribes in redhills tamilnadu India. Asian Pacific J Trop Dis. 2012;2:S874–S877. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ganesan S., Suresh N., Kesaven L. Ethnomedicinal survey of lower Palni Hills of Tamilnadu. Indian J Tradit Knowl. 2004;3:299–304. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Revathi P., Parimelazhagan T. Traditional knowledge on medicinal plants used by the Irula tribe of Hasanur Hills Erode District Tamil Nadu India. Ethnobotan Leaf. 2010;14:136–160. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Pattanaik C., Sudhakar Reddy C. Medicinal plant wealth of local communities in Kuldiha Wildlife Sanctuary Orissa India. J Herbs Spices Med Plants. 2008;14:175–184. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Alagesaboopathi C. Ethnomedicinal plants and their utilization by villagers in Kumaragiri hills of Salem district of Tamilnadu India. Afr J Tradit Complement Altern Med. 2009;6:222–227. doi: 10.4314/ajtcam.v6i3.57157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Sravan P.M., Venkateshwara R.K.N., Santhosha D., Chaitany R.S.N.A.K.K., David B. Medicinal plants used by the ethnic practitioners in Naldonda District Andhra Pradesh India. Int J Res Ayurveda Pharm. 2010;1:493–496. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Dahare D.K., Jain A. Ethnobotanical studies on plant resources of Tahsil Multai District Betul Madhya Pradesh India. Ethnobotan Leaf. 2010;14:694–705. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Hazarika T.K., Nautiyal B.P. Studies on wild edible fruits of Mizoram India used as ethno-medicine. Genet Resour Crop Evol. 2012;59:1767–1776. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Bhat J.A., Kumar M., Bussmann R.W. Ecological status and traditional knowledge of medicinal plants in Kedarnath Wildlife Sanctuary of Garhwal Himalaya. India J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2013;9:1–18. doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-9-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Singh B., Borthakur S.K., Phukan S.J. A Survey of ethnomedicinal plants utilized by the indigenous people of Garo Hills with special reference to the Nokrek Biosphere Reserve (Meghalaya) India. J Herbs Spices Med Plants. 2014;20:1–30. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Lingaraju D.P., Sudarshana M.S., Rajashekar N. Ethnopharmacological survey of traditional medicinal plants in tribal areas of Kodagu district Karnataka. India J Pharm Res. 2013;6:284–297. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Jain S.C., Jain R., Singh R. Ethnobotanical survey of Sariska and Siliserh regions from Alwar district of Rajasthan India. Ethnobotan Leaf. 2009;13:171–188. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Kumar M., Paul Y., Anand V.K. An ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants used by the locals in Kishtwar Jammu and Kashmir India. Ethnobotan Leaf. 2009;13:1240–1260. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Swarnkar S., Katewa S.S. Ethnobotanical observation on tuberous plants from tribal area of Rajasthan (India) Ethnobotan Leaf. 2008;12:647–666. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Katewa S.S., Chaudhary B.L., Jain A. Folk herbal medicines from tribal area of Rajasthan. India J Ethnopharmacol. 2004;92:41–46. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2004.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Vanila D., Ghanthikumar S., Manickam V.S. Ethnomedicinal uses of plants in the plains area of the Tirunelveli-District Tamilnadu India. Ethnobotan Leaf. 2008;12:1198–1205. [Google Scholar]

- 87.Kumar K., Murthy A.R., Upadhyay O.P. Plants used as antidotes by the tribals of Bihar. Anc Sci Life. 1998;17:268–272. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Chandra K., Paney B.N., Lal V.K. Folk-lore medicinal plants of Dumka (Bihar) Anc Sci Life. 1985;4:181–185. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Vanam A. Traditional remedies of Kani tribes of Kottoor reserve forest Agasthyavanam Thiruvananthapuram Kerala. Indian J Tradit Knowl. 2007;6:589–594. [Google Scholar]

- 90.Vijayakumar S., Yabesh J.M., Prabhu S., Manikandan R., Muralidharan B. Quantitative ethnomedicinal study of plants used in the Nelliyampathy hills of Kerala India. J Ethnopharmacol. 2015;161:238–254. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2014.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Shanmugam S., Rajendran K., Suresh K. Traditional uses of medicinal plants among the rural people in Sivagangai district of Tamilnadu Southern India. Asian Pacific J Trop Biomed. 2012;2:S429–S434. [Google Scholar]

- 92.Dey A., De J.N. Traditional use of plants against snakebite in Indian subcontinent: a review of the recent literature. Afr J Tradit Complement Altern Med. 2012;9:153–174. doi: 10.4314/ajtcam.v9i1.20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Chakraborty M.K., Bhattacharjee A. Some common ethnomedicinal uses of various diseases in Purulia district West Bengal. Indian J Tradit Knowl. 2006;5:554–558. [Google Scholar]

- 94.Ghosh A. Ethnomedicinal plants used in West Rarrh region of West Bengal. Nat Prod Rad. 2008;7:461–465. [Google Scholar]

- 95.Suthari S., Kanneboyena O., Raju V.S. Ethnomedicinal knowledge of inhabitants from Gundlabrahmeswaram Wildlife Sanctuary (Eastern Ghats) Andhra Pradesh India. Am J Ethnomed. 2015;2:333–346. [Google Scholar]

- 96.Suthari S., Sreeramulu N., Omkar K., Raju V. The climbing plants of northern Telangana in India and their ethnomedicinal and economic uses. Indian J Plant Sci. 2014;3:86–100. [Google Scholar]

- 97.Reddy M.B., Reddy K.R., Reddy M.N. A survey of medicinal plants of Chenchu tribes of Andhra Pradesh India. Pharm Biol. 1988;26:189–196. [Google Scholar]

- 98.Rajendran S.M., Agarwal S.C., Sundaresan V. Lesser known ethnomedicinal plants of the Ayyakarkoil Forest Province of Southwestern Ghats Tamilnadu India—Part I. J Herbs Spices Med Plants. 2004;10:103–112. [Google Scholar]

- 99.Parinitha M., Harish G.U., Vivek N.C., Mahesh T., Shivanna M.B. Ethno-botanical wealth of Bhadra wild life sanctuary in Karnataka. Indian J Tradit Knowl. 2004;3:37–50. [Google Scholar]

- 100.Prakasha H.M., Krishnappa M. People's knowledge on medicinal plants in Sringeri taluk Karnataka. Indian J Tradit Knowl. 2006;5:353–357. [Google Scholar]

- 101.Koche D.K., Shirsat R.P., Imran S., Nafees M., Zingare A.K., Donode K.A. Ethnobotanical and ethnomedicinal survey of Nagzira Wildlife Sanctuary District Gondia (MS) India-Part I. Ethnobotan Leaf. 2008;12:56–69. [Google Scholar]