Abstract

We estimated the temporal course of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in Vietnam-era veterans using a national sample of male twins with a 20-year follow-up. The complete sample included those twins with a PTSD diagnostic assessment in 1992 and who completed a DSM-IV PTSD diagnostic assessment and a self-report PTSD checklist in 2012 (n = 4,138). Using PTSD diagnostic data, we classified veterans into 5 mutually exclusive groups, including those who never had PTSD, and 4 PTSD trajectory groups: (a) early recovery, (b) late recovery, (c) late onset, and (d) chronic. The majority of veterans remained unaffected by PTSD throughout their lives (79.05% of those with theater service, 90.85% of those with nontheater service); however, an important minority (10.50% of theater veterans, 4.45% of nontheater veterans) in 2012 had current PTSD that was either late onset (6.55% theater, 3.29% nontheater) or chronic (3.95% theater, 1.16% nontheater). The distribution of trajectories was significantly different by theater service (p < .001). PTSD remains a prominent issue for many Vietnam-era veterans, especially for those who served in Vietnam.

Few longitudinal studies of the course of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) focus over the lifespan of an individual (Peleg & Shalev, 2006). Most research suggests that the majority of cases occur proximal to trauma exposure and about a third remit within 5 years (Breslau et al., 1998; Chapman et al., 2012; Kessler, Sonnega, Bromet, Hughes, & Nelson, 1995). Of those who experience PTSD, for about a third of civilians (Chapman et al., 2012; Kessler et al., 1995) and half of military veterans (Schnurr, Lunney, Sengupta, & Waelde, 2003), however, PTSD is stable and chronic. In addition, a recent review of 19 studies indicated that delayed-onset PTSD accounted for 38.2% and 15.3%, respectively, of military and civilian cases of PTSD (Andrews, Brewin, Philpott, & Stewart, 2007). Others have pointed out the complex trajectories of PTSD (especially for veterans) that may be related to factors that occur over the years following initial exposure (Bryant, O’Donnell, Creamer, McFarlane, & Silove, 2013; Solomon & Mikulincer, 2006).

Several large cross-sectional epidemiologic studies conducted from 1985 through 1990, more than a decade after the end of the war, established PTSD as a major condition affecting a large number of Vietnam-era veterans who served in the combat theater (Eisen et al., 2004; Kulka et al., 1990; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 1989). For example, Kulka et al. (1990) found that 15% and 30% of male theater veterans had current and lifetime PTSD, whereas Eisen et al. (2004) reported that 15.0% of theater veterans and 6.1% of nontheater veterans had lifetime PTSD. A recent follow-up study (based on the Kulka et al. cohort) found that 4.5% of Vietnam veterans had current PTSD (Marmar et al., 2015), suggesting considerable remission over approximately 25 years.

Nearly 40 years after the end of the U.S. involvement in the Vietnam conflict, however, the trajectories of PTSD among aging veterans are unknown. In fiscal year 2010, 259,133 Vietnam-era veterans had one or more mental health visits within the Veterans Affairs (VA) heath care system for PTSD (Hermes, Rosenheck, Desai, & Fontana, 2012), attesting to the chronicity of the disorder for some; less is known about the long-term course for those not using VA health services. A recent doubling of PTSD cases among Vietnam-era veterans seeking VA mental health treatment between 1997 and 2010 suggests an increased prevalence of PTSD in this at risk population (Hermes et al., 2012), which could be due to late onset or chronicity with late treatment seeking as well as new screening policies for VA primary care. Psychiatric comorbidities, especially alcohol use disorder and depression, could also be implicated, as they have been found to worsen PTSD symptoms (Sampson et al., 2015).

In the mid-1980s the Vietnam Era Twin (VET) Registry was constructed from military discharge records as an epidemiologic resource to study the physical and mental health of Vietnam-era veterans (Henderson et al., 1990). PTSD was part of a psychiatric assessment conducted in 1992 on VET Registry members (see Eisen et al., 2004). The aims of the current study, a component of VA Cooperative Study #569, Course and Consequences of PTSD in Vietnam Era Twins (Cooperative Studies Program [CSP] #569), which was initiated in 2007, were to examine the 20-year trajectories of PTSD in VET Registry members by using the assessments for current and subthreshold PTSD in 2012.

Method

Participants and Procedure

This study was conducted using the VET Registry, a national sample of male–male twin pairs from all service branches who served on active duty during the Vietnam era (1964–1975; Henderson et al., 1990). Members of the VET Registry were born from 1939 through 1957. The VET Registry is representative of Vietnam-era veterans who were assembled solely on the basis of being members of a twin pair. The cohort study design used psychiatric assessment data collected at two points in time: in 1992 (Eisen et al., 2004; Tsuang et al., 1996) and in 2012 as part of the current study.

Participants in the CSP #569 study included VET Registry members who entered military service in 1965 or later, were discharged prior to 1986, and completed the 1992 PTSD assessments. After mailing a complete description of the study to all active VET Registry members, informed consent was obtained; the VA Central Institutional Review Board approved the study protocol. There were two sources of new data in 2012: a mailed questionnaire and a telephone assessment. Twins were requested to complete and return a physical and mental health questionnaire by mail. A telephone interview used a structured psychiatric assessment to diagnose PTSD. Participating twins were compensated after completion of the mailed questionnaire ($75) and telephone psychiatric interview ($75). Because of the size and scope of the study, all mail and telephone fieldwork was done under contract by Abt SRBI, Inc. (West Long Branch, NJ), a large survey research organization.

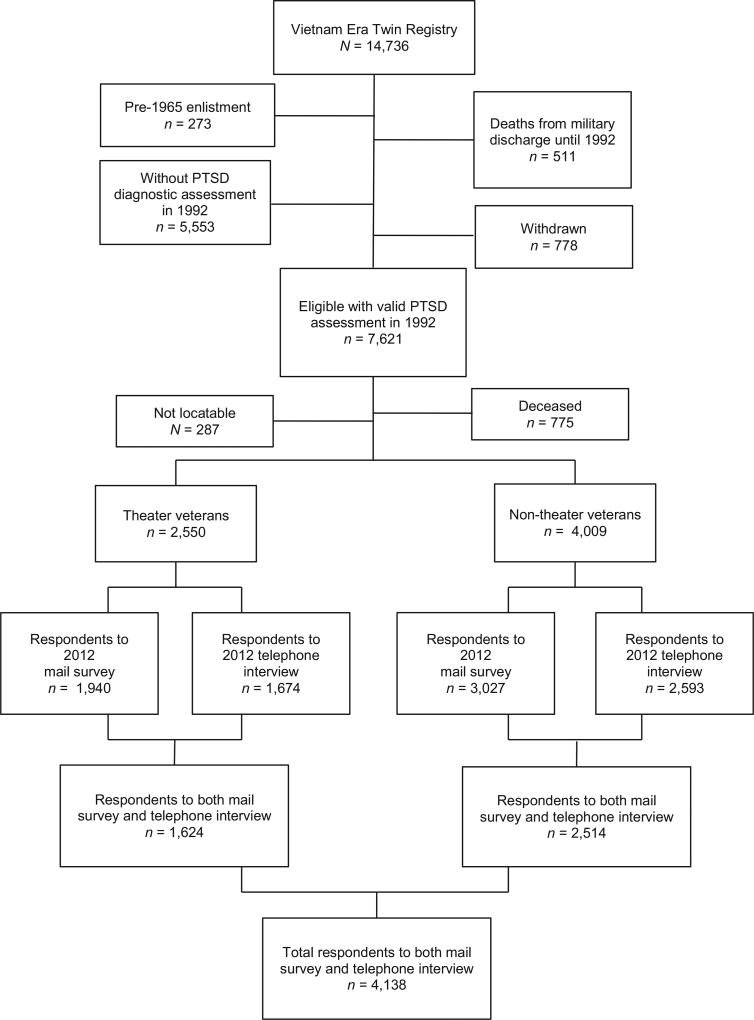

From our original sample of 14,736 individuals in the VET Registry (7,368 twin pairs), 511 individuals had died between discharge and 1992 when the baseline PTSD assessment was conducted; in addition, 778 individuals were excluded because they requested to be withdrawn from the Registry, and another 273 were ineligible due to their pre-1965 enlistment date (Figure 1). In 1992, 7,621 veterans had completed the telephone diagnostic assessment for PTSD using the Diagnostic Interview Schedule (DIS; Robins et al., 1989). After excluding those who had died in 1992 through 2010, we obtained a final response rate of 60.4% of 6,559, who completed telephone psychiatric interviews in 2012 of those who were alive and eligible for follow-up; these 4,138 veterans were the overall sample for analysis.

Figure 1.

Flow chart for sample construction.

Measures

In 1992, VET Registry members participated in a diagnostic assessment of PTSD based on a telephone administration of the Diagnostic Interview Schedule (DIS) according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (3rd ed., rev.; DSM-III-R; American Psychiatric Association (APA), 1987; Tsuang et al., 1996). The DIS was administered in standard fashion, and respondents were given the opportunity to name up to three separate qualifying traumatic events. When a respondent met the full criteria according to the DSM-III-R during his lifetime, he was assigned a diagnosis of lifetime PTSD (pre-1992). When a respondent met criteria within the past 12 months, he was assigned a diagnosis of current PTSD.

We also determined the presence of subthreshold PTSD (current or lifetime) according to a definition that has been widely used in the literature (Blanchard et al., 1995; Schnyder, Moergeli, Klaghofer, & Buddeberg, 2001). These criteria are identical to the DSM-III-R PTSD criteria except that respondents meet Criterion C or D, but not both. We chose the Blanchard et al. criteria for subthreshold PTSD for several reasons: (a) it spans both the DSM III-R and DSM-IV (APA, 1994); (b) it is used in a variety of studies, which facilitates comparison; (c) instead of using a severity threshold, it uses a clinical diagnostic DSM-based threshold, which requires a Criterion A event, threshold level reexperiencing symptoms, and at least clinically significant avoidance or hyperarousal problems; and (d) those meeting these criteria did not differ in symptom severity and functioning from those meeting criteria for other subthreshold PTSD definitions in a primary care sample (Kasckow, Yeager, & Magruder, 2015).

We assessed PTSD in 2012 by a telephone administration of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI; Kessler & Üstün, 2004) according to the DSM-IV. We used DSM-IV criteria to conform to the accepted standard in 2012. The CIDI is a structured instrument designed for administration by trained nonclinical interviewers; it has become the most widely used instrument for the assessment of psychiatric disorders in epidemiologic studies.

We followed the standard method of CIDI administration and asked the symptom questions for up to two separate stressful traumatic events named by the respondent; however, if a veteran identified more than two events, one of which was theater combat exposure, we always asked symptom questions for the combat exposure event. As with the DIS, a final diagnosis was assigned via a computer algorithm according to the PTSD symptom criteria specified in the DSM-IV or subthreshold criteria using Blanchard et al. (1995). Based on this 2012 PTSD assessment, respondents were classified as having current full or current subthreshold PTSD.

Training for both the DIS and CIDI was done by certified trainers at the start of the study and continuously monitored during the course of the fieldwork.

The PTSD Checklist-Civilian Version (PCL; Weathers, Litz, Huska, & Keane, 1993), one of the most widely used self-report questionnaires of PTSD, was included in the 2012 mail survey to assess symptom burden. The PCL consists of 17 items corresponding to DSM-IV criteria with each item scored on a 5-point scale. Scores can range from 17 to 85. The PCL has excellent correspondence with the Clinician Administered PTSD Scale (CAPS; Yeager, Magruder, Knapp, Nicholas, & Frueh, 2007); more recently it has been shown to have excellent correspondence with the CIDI PTSD module (Magruder et al., 2014). A score of 50 was originally recommended as an indicator of probable PTSD; however, in recent years, newer studies support the use of scores as low as 31–33 (Magruder et al., 2014; Yeager et al., 2007), particularly for older veterans (Yeager & Magruder, 2013). The PCL score was used as an outcome for current PTSD symptom burden among the trajectory groups.

Information on the 1992 demographic characteristics was available from the VET Registry database; variables included race, marital status, educational attainment, and employment status. Military service characteristics primarily came from military records and included date of birth, age of enlistment, rank at discharge, dates of enlistment and discharge, and branch of service. For most veterans we assigned Vietnam theater service based on a mailed questionnaire at the Registry’s inception (1985–1990); in fewer than 4% of the veterans theater service was assigned based on military records. Psychiatric diagnoses of major depression (MDD), alcohol and substance use disorders (AUD, SUD), and generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) were assessed in the 1992 DIS using DSM-III-R criteria.

Data Analysis

We estimated the response rate based on the number of eligible VET Registry members who responded in 2012 to both the mailed and telephone interview. We used a two-step weighting process in our estimation of PTSD trajectory groups and mean PCL scores to adjust for nonresponse (Step 1) and the current 2010 population characteristics of the living Vietnam-era veteran population (Step 2). The nonresponse weights were generated based on a model-based weighting function (Rosenbaum, 1987) that predicted nonresponse from the following variables included in the VET Registry database: race, current 2010 age, branch of service, marital status at enlistment, education at enlistment, rank at discharge, enlistment year, discharge year, Vietnam theater service, combat exposure, psychiatric diagnoses from the 1992 assessment (MDD, AUD, GAD, and PTSD), and past participation in Registry studies when available. After weighting for nonresponse, we then developed second-stage weights based on the characteristics of the 2010 living Vietnam-era veteran population as estimated by the National Survey of Veterans (Westat, 2010). We restricted the National Survey of Veterans sample to mirror the construction criteria used to create the VET Registry cohort with the exception of twinhood: males who served during the Vietnam era (1964–1975), born from 1939 through 1957, enlisted in 1965 through 1975, and discharged prior to 1986. The second-stage population weights were based on age, branch of service, discharge year, enlistment year, current 2010 marital status, education, and total family income. The product of the nonresponse and current population weights were used to generate the final weights used for estimating the PTSD trajectory groups and mean PCL scores.

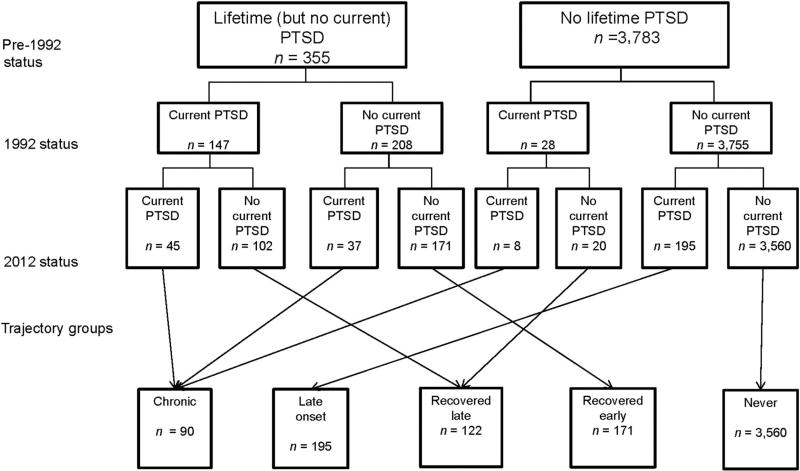

Based on the 1992 and 2012 PTSD diagnostic assessments, all respondents were classified into groups covering pre-1992 status, 1992 status, and 2012 status. Pre-1992 status was assigned on the basis of a twin meeting or not meeting criteria for past PTSD (i.e., lifetime PTSD but not current) at the 1992 assessment. Current 1992 status was assigned on the basis of meeting or not meeting criteria for 12-month PTSD. Current 2012 PTSD was similarly assigned on the basis of meeting or not meeting criteria for 12 month PTSD in 2012. Using the classifications from these three time periods (pre-1992, 1992, 2012), twins were classified into mutually exclusive groups: chronic, late recovery, early recovery, delayed onset, and a group who never had PTSD (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) trajectory and no PTSD groups.

Using these groups and stratifying by theater service, we derived estimates of the proportion of the population in each group (and 95% confidence intervals [CIs]). We also developed trajectory groups that included full PTSD diagnosis alone and full PTSD diagnosis plus subthreshold PTSD. Using PCL scores we obtained estimates of mean symptom burden (and 95% CIs) for each of the groups. We further adjusted for military and 1992 demographic factors (age, race, marital status, education, branch of service, employment, and age at enlistment) using model-based weighting. Lastly, because comorbidities can affect trajectories (Sampson et al., 2015), we included psychiatric diagnoses in 1992 (MDD, AUD, SUD, and GAD) in our modeling. In all analyses, significance levels were two-sided and set at p = .05. Analyses accounted for the clustered data structure represented by twin pairs in the VET Registry using cluster variance estimators. All statistical tests (Pearson χ2 test for categorical and the Wald test for continuous) were corrected to account for weights. Data analyses were performed with Stata 14.0 (StataCorp, 2015).

Results

The distribution of military service, demographic, and health characteristics was compared via design-corrected Pearson χ2 tests among respondents (unweighted) and after nonresponse and population reweighting; the 2010 National Survey of Veterans population distributions are also presented (Supplemental Table S1). Weighting made the population older, less likely to be White, less likely to be married, and have slightly lower income. Regarding military variables, weighting increased Army and Marines representation and increased both early and late enlistment and discharge years. The characteristics of the fully reweighted sample were similar to the comparable population values of living Vietnam-era veterans for all demographic and military service characteristics derived from the 2010 National Survey of Veterans. All tables and analyses other than Supplemental Table S1 are based on these weights.

In the overall analytic sample, there were differences in the 1992 demographic and military service variables between the groups (Table 1). Among demographic variables, age, race, education, and employment were significantly different across the groups, with marital status not significantly different. There were also differences regarding branch of service, service in Southeast Asia, military rank at discharge, and age at enlistment, but enlistment year was not significant. The presence of comorbid psychiatric diagnoses was significantly different.

Table 1.

Demographic and Military Service Characteristics and Psychiatric Disorders Among Study Participants According to PTSD Trajectory or Status

| PTSD trajectory or status

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | No PTSD (n = 3,560) % |

Early recovery (n = 171) % |

Late recovery (n = 122) % |

Late onset (n = 195) % |

Chronic (n = 90) % |

p |

| Age in years (1992) | .002 | |||||

| ≤39 | 19.4 | 20.7 | 23.0 | 31.6 | 25.2 | |

| 40–41 | 14.3 | 20.2 | 20.7 | 19.7 | 18.6 | |

| 42–43 | 24.3 | 32.9 | 32.8 | 26.0 | 24.6 | |

| ≥44 | 42.0 | 26.2 | 23.5 | 22.7 | 31.6 | |

| Race | .002 | |||||

| White | 89.0 | 85.1 | 91.5 | 76.1 | 77.6 | |

| Non-White | 11.0 | 14.9 | 8.5 | 23.9 | 22.4 | |

| Marital status (1992) | .083 | |||||

| Married/widowed | 75.2 | 81.7 | 68.6 | 70.1 | 69.9 | |

| Divorced | 17.2 | 15.7 | 22.2 | 23.6 | 13.8 | |

| Never married | 7.6 | 2.6 | 9.2 | 6.3 | 16.3 | |

| Education (1992) | .001 | |||||

| <HS graduate | 3.1 | 2.1 | 8.0 | 10.6 | 1.5 | |

| HS graduate | 31.3 | 37.8 | 33.0 | 22.9 | 39.0 | |

| Some college/vocational | 36.0 | 35.4 | 37.9 | 48.6 | 45.2 | |

| College graduate or more | 29.6 | 23.7 | 21.1 | 17.9 | 14.3 | |

| Employment (1992) | <.001 | |||||

| Fulltime | 94.1 | 94.4 | 86.4 | 87.6 | 88.6 | |

| Part time | 1.5 | 1.6 | 2.4 | 0.0 | 4.1 | |

| Unemployed | 4.4 | 4.0 | 11.2 | 12.4 | 7.3 | |

| Branch of service | .001 | |||||

| Army | 53.3 | 45.2 | 61.0 | 59.6 | 61.8 | |

| Navy | 22.2 | 20.1 | 18.5 | 14.7 | 11.7 | |

| Air Force | 15.9 | 11.1 | 11.2 | 12.0 | 5.0 | |

| Marines | 8.6 | 23.6 | 9.3 | 13.7 | 18.4 | |

| Enlistment year | .321 | |||||

| <1968 | 41.8 | 34.8 | 22.1 | 31.7 | 41.7 | |

| 1968–1969 | 26.6 | 34.2 | 27.1 | 27.6 | 26.1 | |

| >1969 | 31.6 | 31.0 | 39.8 | 40.8 | 32.2 | |

| Rank at discharge | .039 | |||||

| Enlisted | 92.8 | 96.9 | 99.0 | 99.6 | 100.0 | |

| Officer | 7.2 | 3.1 | 1.0 | 0.4 | 0.0 | |

| Age at enlistment | <.001 | |||||

| <18 | 5.8 | 6.9 | 12.2 | 13.4 | 17.2 | |

| 18 | 19.3 | 33.0 | 15.6 | 23.9 | 20.2 | |

| 19 | 31.4 | 32.8 | 35.2 | 36.4 | 34.8 | |

| ≥20 | 43.5 | 27.2 | 37.1 | 26.3 | 27.7 | |

| Service in Southeast Asia | <.001 | |||||

| No | 63.4 | 37.5 | 43.1 | 49.3 | 30.0 | |

| Yes | 36.6 | 62.5 | 56.6 | 50.7 | 70.0 | |

| Lifetime psychiatric disorder in (1992) | ||||||

| MDD | <.001 | |||||

| No | 93.3 | 81.8 | 56.9 | 86.1 | 47.7 | |

| Yes | 6.7 | 18.2 | 43.1 | 13.9 | 52.3 | |

| AUD | .006 | |||||

| No | 48.3 | 30.3 | 30.3 | 40.9 | 31.8 | |

| Yes | 51.7 | 69.7 | 69.7 | 59.1 | 68.2 | |

| SUD | <.001 | |||||

| No | 92.3 | 77.1 | 74.9 | 76,8 | 72.7 | |

| Yes | 7.7 | 22.9 | 25.1 | 23.2 | 27.3 | |

| GAD | <.001 | |||||

| No | 99.1 | 94.6 | 86.6 | 98.0 | 86.1 | |

| Yes | 0.9 | 5.4 | 13.4 | 2.0 | 13.9 | |

Note. The PTSD group counts of veterans were unweighted; however, estimates were adjusted for nonresponse and to the 2010 Vietnam-era population. The Pearson χ2 statistic was corrected for weighting design and converted to an F statistic. PTSD = posttraumatic stress disorder; HS = high school; MDD = major depressive disorder; AUD = alcohol use disorder; SUD = substance use disorder; GAD = generalized anxiety disorder.

The distribution of groups was significantly different by theater service (p < .001) in the unadjusted analysis and remained so even after adjustment for military service and demographics (p < .001) and prior psychiatric disorders (p < .001; Table 2). Of note, the majority of all respondents were negative for PTSD across the lifespan and therefore without a trajectory; however, there were significantly fewer who were unaffected among those who served in Vietnam (79.05% vs. 90.85% in the fully adjusted model, p < .001). Though there were few in the chronic trajectory, those who served in Vietnam were more likely to be in this category (3.95% vs. 1.16% in the fully adjusted model, p < .001). Similarly, those who served in Vietnam were more likely to be in any of the recovered or late-onset categories.

Table 2.

Weighted Prevalence of PTSD Trajectory Groups and Status by Military Service in Theater Full Cases and Full Plus Subthreshold

| Yes

|

No

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PTSD status and trajectory | % | 95% CI | % | 95% CI | p |

| Full | |||||

| Unadjusted | <.001 | ||||

| No PTSD | 79.33 | [75.69, 82.54] | 90.47 | [88.92, 91.83] | |

| Early recovery | 7.18 | [5.15, 9.93] | 2.83 | [2.15, 3.71] | |

| Late recovery | 3.74 | [2.79, 5.00] | 1.88 | [1.39, 2.55] | |

| Late onset | 5.83 | [4.46, 7.57] | 3.71 | [2.83, 4.85] | |

| Chronic | 3.93 | [2.50, 6.12] | 1.10 | [0.67, 1.81] | |

| Adjusted for military service and demographics | <.001 | ||||

| No PTSD | 78.36 | [74.88, 81.47] | 91.22 | [89.75, 92.49] | |

| Early recovery | 6.98 | [5.09, 9.50] | 2.73 | [2.07, 3.59] | |

| Late recovery | 4.13 | [3.05, 5.57] | 1.74 | [1.26, 2.41] | |

| Late onset | 6.40 | [4.78, 8.53] | 3.21 | [2.47, 4.17] | |

| Chronic | 4.13 | [2.65, 6.37] | 1.10 | [0.64, 1.88] | |

| Adjusted for military service, demographics, and psychiatric disorders | <.001 | ||||

| No PTSD | 79.05 | [75.62, 82.11] | 90.85 | [89.33, 92.18] | |

| Early recovered | 6.56 | [4.82, 8.87] | 2.85 | [2.17, 3.74] | |

| Late recovery | 3.89 | [2.87, 5.26] | 1.85 | [1.33, 2.56] | |

| Late onset | 6.55 | [4.87, 8.76] | 3.29 | [2.52, 4.28] | |

| Chronic | 3.95 | [2.47, 6.27] | 1.16 | [0.69, 1.96] | |

| Full plus subthreshold | |||||

| Unadjusted | <.001 | ||||

| No PTSD | 62.58 | [57.96, 66.99] | 80.83 | [78.84, 82.68] | |

| Early recovery | 17.15 | [13.95, 20.90] | 8.33 | [7.14, 9.70] | |

| Late recovery | 7.00 | [5.38, 9.08] | 3.58 | [2.82, 4.53] | |

| Late onset | 5.69 | [4.28, 7.54] | 3.97 | [3.07, 5.12] | |

| Chronic | 7.57 | [5.69, 10.00] | 3.28 | [2.52, 4.27] | |

| Adjusted for military service and demographics | <.001 | ||||

| No PTSD | 62.17 | [58.24, 65.94] | 81.65 | [79.61, 83.52] | |

| Early recovery | 16.78 | [14.00, 19.99] | 8.30 | [7.08, 9.72] | |

| Late recovery | 7.42 | [5.76, 9.51] | 3.31 | [2.58, 4.22] | |

| Late onset | 5.75 | [4.30, 7.64] | 3.51 | [2.69, 4.56] | |

| Chronic | 7.88 | [5.88, 10.48] | 3.23 | [2.42, 4.30] | |

| Adjusted for military service, demographics, and psychiatric disorders | <.001 | ||||

| No PTSD | 62.89 | [59.00, 66.62] | 81.08 | [79.00, 83.00] | |

| Early recovery | 16.19 | [13.54, 19.23] | 8.58 | [7.32, 10.05] | |

| Late recovery | 7.35 | [5.67, 9.47] | 3.43 | [2.67, 4.40] | |

| Late onset | 5.94 | [4.44, 7.91] | 3.57 | [2.73, 4.67] | |

| Chronic | 7.64 | [5.61, 10.33] | 3.33 | [2.51, 4.40] | |

Note. All estimates were adjusted for nonresponse and to the 2010 Vietnam-era population. Subthreshold cases met Criterion C or D according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (American Psychiatric Association, 1994), but not both in the last 12 months.

Pearson χ2 statistic corrected for weighting design and converted to an F statistic.

When the definition of PTSD was expanded to include cases of subthreshold PTSD, the distribution of groups differed according to theater service both in unadjusted and adjusted analyses (p < .001 for all). There were fewer veterans who were negative both in 1992 and 2012 (fully adjusted model: 62.89% theater service, 81.08% no theater service, p < .001), and more in the chronic, recovered late, and recovered early trajectories, but the relationships were consistent with the pattern identified in the full PTSD diagnosis analyses (p < .001 for all).

The mean PCL scores varied significantly across PTSD groups (p = .001 in unadjusted and adjusted analyses). For those who never had PTSD, there was little difference in PCL scores according to theater service, whereas among those in the recovered early group the PCL score was slightly lower among those who served in Vietnam compared to those who did not serve. This pattern was reversed for the recovered late and late-onset groups where the mean PCL score was consistently 5–10 points higher among those who served in Vietnam compared to those who did not serve in Vietnam. Among those with chronic PTSD there was a smaller increase in the mean PCL score among Vietnam theater veterans compared to nontheater veterans. The analysis that added subthreshold cases to the full PTSD diagnosis showed a similar pattern of PCL scores according to service in Vietnam and trajectory groups. Including these sub-threshold cases made mean PCL score differences according to service in Vietnam in the late-onset and chronic groups more pronounced.

Discussion

Our findings demonstrated that even though the majority of Vietnam-era veterans remained unaffected by PTSD throughout their lives, 20 years after the initial assessment an important subset (10.50% of theater veterans, 4.45% of nontheater veterans) had current PTSD that was either late onset (6.55% theater, 3.29% nontheater) or chronic (3.95% theater, 1.16% nontheater). When subthreshold cases were included, there was an increase in chronic or late-onset PTSD to 13.58% (theater veterans) and 6.90% (nontheater veterans). Furthermore, those who served in Vietnam were less likely to be in the group that never had PTSD, but were more likely to be in the late-onset or chronic groups. Of note, although there were similar percentages for the combined early or late recovery groups (10.45% theater service, 4.70% nontheater service in the fully adjusted estimates), the average PCL scores were still higher than those who never had PTSD—indicating that there were residual symptoms (theater veterans: 28.33 early recovery, 38.27 late recovery vs. 24.85 never; nontheater veterans: 32.53 early recovery, 31.87 late recovery vs. 23.12 never).

The chronicity of PTSD for those who served in Vietnam (3.95%) in this study was remarkably less than the 45.7% found by Koenen, Stellmen, Stellmen, and Sommer (2003) in their 14-year follow-up of American Legionnaire Vietnam Veterans; however, the percentage of late-onset PTSD was comparable in the two studies (5.8% and 6.55% respectively). In a different approach, Schnurr, Lunney, and Sengupta (2004) used previously collected cross-sectional data from two large studies of veterans who served in Vietnam (the National Vietnam Veterans Readjustment Survey; Kulka et al., 1990; and the Matsunaga study of Vietnam veterans of native Hawaiians and Americans of Japanese ancestry; Friedman et al., 1997) and retrospectively established PTSD groups. Of the 482 veterans in the sample, 23.9% had current PTSD or current partial PTSD, 25.5% had only past PTSD (full or partial), and 50.6% had never met criteria for full or partial PTSD. Combining our own categories to be comparable, 13.58% of our total theater sample had current full or subthreshold PTSD, whereas 23.54% had only past (full or subthreshold) PTSD, with 62.89% never having PTSD. Both the chronicity and our estimate of current PTSD were lower in comparison to those of Koenen et al. (2003) and Schnurr et al. (2004). Because we had a longer follow-up period, these differences could be due to increased mortality rates for those with PTSD; some support is found for this in the findings of Boscarino (2006) that both Vietnam theater and nontheater veterans with PTSD had significantly higher all-cause mortality. Our overall remission rate was nearly identical to that of Schnurr et al. (2004; 23.54% vs. 25.5%), whereas our overall unaffected rate was higher (62.89% vs. 5.6%). These differences could be due to study design variation (cross-sectional vs. three time points) or instrumentation, but they also suggest that our overall lower percentage of current PTSD was not due to higher levels of remission than new onset. Notably, neither Koenen et al. (2003) nor Schnurr et al. (2004) included nondeployed comparison groups, so it was not possible to comment on the role of service location. It was difficult to compare our results to those of Marmar et al. (2015), as they assigned improvement (16.0%) and worsening (7.6%) over time to scale changes, and they did not report gender results separately; however, our results (10.45% recovery and 6.55% late onset) appear consistent.

A note is in order regarding the 6.55% (Vietnam service) and 3.29% (non-Vietnam service) of delayed-onset PTSD cases. Of those who had never had PTSD in 1992, 6.55% (Vietnam service) and 3.29% (non-Vietnam service) had developed PTSD by 2012; however, higher percentages (up to 20%) of those with past PTSD or current or subthreshold symptoms in 1992 met PTSD criteria in 2012. Our delayed-onset cases account for the majority of all 2012 current cases, which is considerably higher than the 38.2% for military cases and 15.3% for civilian cases reported in a systematic review (Andrews et al., 2007). Similar to findings of Prigerson, Maciejewski, and Rosenheck (2001), who showed that men with combat trauma had 4.42 higher odds of delayed-onset PTSD than those with other traumas, we also showed a greater percentage of delayed-onset cases in our theater than nontheater veterans.

The measurement of PTSD is critical and bears directly on the interpretation of our results. We defined our 1992 and pre-1992 PTSD groups based on the psychiatric diagnoses obtained from the DIS with DSM-III-R criteria. The DSM-III-R PTSD module in the DIS has low sensitivity (Kulka et al., 1991) and as a consequence may have missed cases of PTSD (particularly cases with childhood maltreatment) in 1992 because trauma was inadequately assessed. Inclusion of cases of sub-threshold PTSD, however, did not change the direction of the results.

The measurement of DSM-IV PTSD using the CIDI has also been criticized, with one study reporting sensitivity of .38, specificity of .99, κ of .49, and area under the curve of .69 compared to the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID; Haro et al., 2006). In a more recent study of Vietnam era women veterans (Kimerling et al., 2014), the diagnostic utility of the CIDI PTSD module was evaluated against the Clinician Administered PTSD Scale (CAPS; Blake et al., 1995; Weathers, Keane, & Davidson, 2001). For lifetime and 12-month PTSD (respectively), this study found κs of .56 and .51, sensitivities of .61 and .71, and specificities of .91 and .85 (Kimerling et al., 2014). The authors concluded that CIDI has good utility for identifying PTSD, but may be somewhat conservative for lifetime PTSD compared with the CAPS. Finally, a separate analysis of the current dataset demonstrated strong association between the CIDI (for current PTSD) and the PCL, with an area under the curve of 89.0% (Magruder et al., 2014). When we examined the association between the trajectory groups and the 2012 PCL scores, the results were consistent with the categorical analyses obtained using the CIDI DSM-IV PTSD diagnosis.

We conducted our diagnostic interviews by telephone, using trained lay interviewers because it was not feasible to use in-person assessments with clinically trained personnel in a large national sample of veterans. Nevertheless, all of our interviews were confidential and not related to benefits or clinical care; thus, we did not expect any exaggeration of symptoms for disability gain. We also cannot discount the possibility, however, that many of our respondents in 1992 may have been reluctant to admit to psychiatric symptoms.

The VET Registry was originally constructed as a sample of male–male twin pairs who served during the Vietnam era, which is a limitation to generalizability. Because the VET Registry was constructed from computerized records maintained by the Defense Manpower Data Center, there is some truncation of veterans from the early years of the Vietnam era: those who were enlisted prior to 1965 were excluded. A further limitation is the absence of female veterans because the VET Registry was restricted to male twins when it was created. It is also possible that being a twin might influence whether one develops PTSD; however, carefully conducted studies from the Scandinavian twin registries suggest that adult twins are at similar risk as the general population for the major physical and mental health disorders (Oberg et al., 2012).

We obtained a 60% response rate nearly 20 years after the first PTSD evaluation. We did reweight our results to adjust for nonresponse (both to the original Registry sample and respondents of the 1992 psychiatric assessment) and the current population of living Vietnam-era veterans. The decision to include those who never have had PTSD may have influenced the outcome such that a comparison of the four trajectory groups only would have yielded different findings.

Strengths of our study included a large sample size drawn from all service branches and ranks and that was not derived from treatment seekers. Additionally, our design was prospective, whereas many such studies have been retrospective, relying solely on recall of symptom onset and remission (Chapman et al., 2012; Kessler et al., 2005; Schnurr et al., 2003).

In summary, 3.95% of theater and 1.16% of nontheater veterans who suffered from PTSD when they were in their 30s and 40s continue to suffer 20 years later in life; an additional 6.55% of theater and 3.29% of nontheater veterans developed late-onset PTSD. The ongoing toll of PTSD was evident in all Vietnam-era veterans, though more so for those who served in Vietnam. This study provided important details about PTSD trajectories and status a period of time for which little had been known. It provides more insight into considering factors like theater and past mental health history in aging veterans. This suggests that there is a need for surveillance and treatment programs throughout the life course and the importance of carefully monitoring the psychiatric health of all aging veterans.

Supplementary Material

Table 3.

Weighted Mean PCL Scores for PTSD Trajectory Groups and Status According to Military Service in Theater

| Service in theater

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes

|

No

|

||||

| PTSD status and trajectory | M | 95% CI for estimate |

M | 95% CI for estimate |

p |

| Full diagnosis | |||||

| Unadjusted | <.001 | ||||

| No PTSD | 24.88 | [23.77, 25.99] | 23.21 | [22.57, 23.85] | |

| Early recovery | 28.20 | [25.73, 30.67] | 32.23 | [28.35, 36.11] | |

| Late recovery | 38.73 | [33.69, 43.78] | 32.55 | [28.04, 37.05] | |

| Late onset | 52.95 | [48.14, 57.85] | 42.69 | [37.59, 47.79] | |

| Chronic | 49.86 | [43.76, 55.96] | 47.46 | [40.59, 54.32] | |

| Adjusted for military service and demographics | <.001 | ||||

| No PTSD | 24.92 | [24.03, 25.80] | 23.07 | [22.41, 23.72] | |

| Early recovery | 28.43 | [26.48, 30.38] | 32.49 | [28.31, 36.68] | |

| Late recovery | 38.60 | [33.57, 43.64] | 31.95 | [26.84, 37.08] | |

| Late onset | 50.94 | [46.37, 55.52] | 43.12 | [38.42, 47.82] | |

| Chronic | 49.91 | [43.51, 56.31] | 47.27 | [39.55, 54.99] | |

| Adjusted for military service, demographics, and psychiatric disorders | .001 | ||||

| No PTSD | 24.85 | [23.97, 25.73] | 23.12 | [22.48, 23.76] | |

| Early recovery | 28.33 | [26.33, 30.32] | 32.53 | [28.32, 36.74] | |

| Late recovery | 38.27 | [33.36, 43.19] | 31.87 | [27.10, 36.63] | |

| Late onset | 51.11 | [46.40, 55.82] | 42.98 | [38.12, 47.84] | |

| Chronic | 49.61 | [42.90, 56.31] | 47.05 | [39.41, 54.69] | |

| Diagnosis plus subthreshold cases | |||||

| Unadjusted | <.001 | ||||

| No PTSD | 23.51 | [22.43, 24.59] | 22.82 | [22.12, 23.52] | |

| Early recovery | 27.28 | [25.27, 29.29] | 27.16 | [25.34, 28.98] | |

| Late recovery | 34.29 | [30.95, 37.63] | 27.85 | [25.58, 30.11] | |

| Late onset | 47.77 | [43.01, 52.52] | 38.30 | [34.15, 42.46] | |

| Chronic | 49.46 | [45.31, 53.61] | 42.83 | [38.41, 47.24] | |

| Adjusted for military service and demographics | <.001 | ||||

| No PTSD | 23.68 | [22.79, 24.58] | 22.68 | [22.00, 23.40] | |

| Early recovery | 27.23 | [25.55, 28.92] | 26.95 | [25.08, 28.83] | |

| Late recovery | 34.04 | [30.70, 37.38] | 27.54 | [25.37, 29.72] | |

| Late onset | 47.99 | [43.84, 52.15] | 38.49 | [34.14, 42.84] | |

| Chronic | 48.79 | [44.47, 53.12] | 42.32 | [37.69, 46.95] | |

| Adjusted for military service, demographics, and psychiatric disorders | <.001 | ||||

| No PTSD | 23.57 | [22.69, 24.44] | 22.73 | [22.04, 23.43] | |

| Early recovery | 27.39 | [25.62, 29.16] | 26.99 | [25.09, 28.88] | |

| Late recovery | 33.72 | [30.44, 37.00] | 27.74 | [25.57, 29.91] | |

| Late onset | 48.21 | [44.00, 52.42] | 38.37 | [33.91, 42.82] | |

| Chronic | 48.54 | [44.03–53.05] | 42.34 | [37.76, 46.92] | |

Note. All estimates were adjusted for nonresponse and to the 2010 Vietnam-era population. Subthreshold cases met Criterion C or D according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (American Psychiatric Association, 1994), but not both in the last 12 months.

Wald test adjusted for weighting.

Acknowledgments

The Cooperative Studies Program (CSP) of the Office of Research and Development, Clinical Science Research and Development of the United States Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), has provided financial support for Cooperative Study #569 and the development and maintenance of the Vietnam Era Twin (VET) Registry. Dr. Viola Vaccarino was supported in part by a National Institutes of Health award (K24 HL077506).

Dr. Magruder had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. The funding source was involved in the design and conduct of the study, and the interpretation, preparation, review, and approval of the manuscript. The authors were responsible for the collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data and for the preparation of the manuscript and its submission for publication. The authors gratefully acknowledge the continued cooperation and participation of the members of the VET Registry—without their contribution this research would not have been possible. The authors would also like to thank the members of the Department of Veterans Affairs Cooperative Study #569 Group (in addition to the authors): I. Curtis, A. Ali, B. Majerczyk, B. Harp, K. Moore, A. Fox, M. Tsai, A. Mori, J. Sporleder, P. Terry, Seattle, WA; D. Yeager, Charleston, SC. Executive Committee: S. Eisen, Washington, DC; A. Snodgrass, Albuquerque, NM. Data Monitoring Committee: J. Vasterling, Boston, MA; M. Stein, La Jolla, CA; B. Booth, Little Rock, AR; J. Westermeyer, Minneapolis, MN. Planning Committee: M. McFall, Seattle, WA; T. O’Leary, S. Eisen, Washington, DC; M. Smith, Palo Alto, CA; K. Swanson, Albuquerque, NM. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States Government.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 3. Washington, DC: Author; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4. Washington, DC: Author; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Andrews B, Brewin CR, Philpott R, Stewart L. Delayed-onset posttraumatic stress disorder: A systematic review of the evidence. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 2007;164:1319–1326. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.06091491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blake DD, Weathers FW, Nagy LM, Kaloupek DG, Gusman FD, Charney DS, Keane TM. The development of a clinician-administered PTSD scale. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 1995;8:75–90. doi: 10.1002/jts.2490080106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanchard EB, Hickling EJ, Taylor AE, Forneris CA, Loos W, Jaccard J. Effects of varying scoring rules of the Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale (CAPS) for the diagnosis of post-traumatic stress disorder in motor vehicle accident victims. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1995;33:471–475. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(94)00064-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boscarino JA. Posttrumatic stress disorder and mortality amont U.S. Army veterans 30 years after military service. Annals of Epidemiology. 2006;16:248–256. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2005.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breslau N, Kessler RC, Chilcoat HD, Schultz LR, Davis GC, Andreski P. Trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder in the community: The 1996 Detroit Area Survey of Trauma. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1998;55:626–632. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.55.7.626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryant RA, O’Donnell ML, Creamer M, McFarlane AC, Silove D. A multisite analysis of the fluctuating course of posttraumatic stress disorder. JAMA Psychiatry. 2013;70:839–846. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.1137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman C, Mills K, Slade T, McFarlane AC, Bryant RA, Creamer M, Teesson M. Remission from post-traumatic stress disorder in the general population. Psychological Medicine. 2012;42:1695–1703. doi: 10.1017/S0033291711002856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisen SA, Griffith KH, Xian H, Scherrer JF, Fischer ID, Chantarujikapong S, Tsuang MT. Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of psychiatric disorders in 8,169 male Vietnam war era veterans. Military Medicine. 2004;169:896–902. doi: 10.7205/milmed.169.11.896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman MJ, Ashcraft ML, Beals JL, Keane TM, Manson SM, Marsella AJ. Matsunaga Vietnam Veterans Project. White River Junction, VT: National Center for Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder and National Center for American Indian and Alaska Native Mental Health Research; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Haro JM, Arbabzadeh-Bouchez S, Brugha TS, de Girolamo G, Guyer ME, Jin R, Kessler RC. Concordance of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview Version 3.0 (CIDI 3.0) with standardized clinical assessments in the WHO World Mental Health surveys. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research. 2006;15:167–180. doi: 10.1002/mpr.196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson WG, Eisen S, Goldberg J, True WR, Barnes JE, Vitek ME. The Vietnam Era Twin Registry: A resource for medical research. Public Health Reports. 1990;105:368–373. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermes ED, Rosenheck RA, Desai R, Fontana AF. Recent trends in the treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder and other mental disorders in the VHA. Psychiatric Services. 2012;63:471–476. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201100432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasckow J, Yeager DE, Magruder KM. Levels of symptom severity and functioning in four different definitions of subthreshold post-traumatic stress disorder in primary care veterans. Journal of Nervous and Mental Diseases. 2015;203:43–47. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0000000000000233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Merikangas KR, Walters EE. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005;62:593–602. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Sonnega A, Bromet E, Hughes M, Nelson CB. Posttraumatic stress disorder in the National Co-morbidity Survey. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1995;52:1048–1060. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1995.03950240066012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, U¨stu¨n TB. The World Mental Health (WMH) Survey Initiative Version of the World Health Organization (WHO) Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research. 2004;13:93–121. doi: 10.1002/mpr.168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimerling R, Serpi T, Weathers F, Kilbourne AM, Kang H, Collins JF, Magruder K. Diagnostic accuracy of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI 3.0) PTSD module among female Vietnam-era veterans. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2014;27:160–167. doi: 10.1002/jts.21905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koenen KC, Stellman JM, Stellman SD, Sommer JF., Jr Risk factors for the course of posttraumatic stress disorder among Vietnam veterans: A 14-year follow-up of American Legionnaires. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2003;71:980–986. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.71.6.980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulka RA, Schlenger WE, Fairbank JA, Hough RL, Jordan BK, Marmar CR, Grady DA. Trauma and the Vietnam war generation: Report of findings from the National Vietnam Veterans Readjustment Study. 1. New York, NY: Brunner Mazel; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Kulka RA, Schlenger WE, Fairbank JA, Jordan BK, Hough RL, Marmar CR, Weiss DS. Assessment of PTSD in the community: Prospects and pitfalls from recent studies of Vietnam veterans. Psychological Assessment: A Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1991;3:547–560. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.3.4.547. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Magruder KM, Yeager DE, Goldberg J, Forsberg C, Litz B, Vaccarino V, Smith N. Diagnostic performance of PCL and VET-R PTSD Scale. Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences. 2014;6:1–8. doi: 10.1017/S2045796014000365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marmar CR, Schlenger W, Henn-Haase C, Qian M, Purchia E, Li M, Kulka RA. Course of posttraumatic stress disorder 40 years after the Vietnam war: Findings From the National Vietnam Veterans Longitudinal Study. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72:875–881. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.0803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oberg S, Cnattingius S, Sandin S, Lichtenstein P, Morley R, Il-iadou AN. Twinship influence on morbidity and mortality across the lifespan. International Journal of Epidemiology. 2012;41:1002–1009. doi: 10.1093/ije/dys067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peleg T, Shalev AY. Longitudinal studies of PTSD: Overview of findings and methods. CNS Spectrums. 2006;11:589–602. doi: 10.1017/s109285290001364x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prigerson HG, Maciejewski PK, Rosenheck RA. Combat trauma: Trauma with highest risk of delayed onset and unresolved posttrumatic s tress disorder symptoms, unemployment, and abuse among men. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 2001;189:99–108. doi: 10.1097/00005053-200102000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robins LN, Cottler LB, Bucholz KK, Compton WM, North C, Rourke K. The Diagnostic Interview Schedule, Version III-R. St. Louis, MO: Washington University School of Medicine; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbaum PR. Model-based direct adjustment. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 1987;82:387–394. doi: 10.1080/01621459.1987.10478441. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sampson L, Cohen G, Calabrese J, Fink D, Tamburino M, Liberzon I, Galea S. Mental health over time in a military sample: The impact of alcohol use disorder on trajectories of psychopathology after deployment. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2015;28:547–555. doi: 10.1002/jts.22055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnurr PP, Lunney CA, Sengupta A. Risk factors for the development versus maintenance of posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2004;17:85–95. doi: 10.1023/B:JOTS.0000022614.21794.f4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnurr PP, Lunney CA, Sengupta A, Waelde LC. A descriptive analysis of PTSD chronicity in Vietnam veterans. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2003;16:545–553. doi: 10.1023/B:JOTS.0000004077.22408.cf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnyder U, Moergeli H, Klaghofer R, Buddeberg C. Incidence and prediction of posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms in severely injured accident victims. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 2001;158:594–599. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.4.594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solomon Z, Mikulincer M. Trajectories of PTSD: A 20-year longitudinal study. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2006;163:659–666. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.163.4.659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- StataCorp. Stata statistical software: Release 14 [Computer software] College Station, TX: Author; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Tsuang MT, Lyons MJ, Eisen SA, Goldberg J, True W, Lin N, Eaves L. Genetic influences on DSM-III-R drug abuse and dependence: A study of 3,372 twin pairs. American Journal of Medical Genetics. 1996;67:473–477. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-8628(19960920)67:5<473::AID-AJMG6>3.0.CO;2-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Vietnam Experience Study. IV. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 1989. Health status of Vietnam veterans. IV. Psychological and neurological evaluation. [Google Scholar]

- Weathers F, Litz B, Huska J, Keane TM. The PTSD Checklist: Reliability, validity, and diagnostic utility. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies; San Antonio, TX. 1993. Oct, [Google Scholar]

- Weathers FW, Keane TM, Davidson JR. Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale: A review of the first ten years of research. Depression and Anxiety. 2001;13:132–156. doi: 10.1002/da.1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westat . National Survey of Veterans, Active Duty Service Members, Demobilized National Guard and Reserve Members, Family Members, and Surviving Spouses. Rockville, MD: Author; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Yeager DE, Magruder KM. PTSD Checklist scoring rules for elderly Veterans Affairs outpatients. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2013.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeager DE, Magruder KM, Knapp RG, Nicholas JS, Frueh BC. Performance characteristics of the posttraumatic stress disorder checklist and SPAN in Veterans Affairs primary care settings. General Hospital Psychiatry. 2007;29:294–301. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2007.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.