Abstract

Background

Despite decades of research, the concept of normality in labour in terms of its progression and duration is not universal or standardized. However, in clinical practice, it is important to define the boundaries that distinguish what is normal from what is abnormal to enable women and care providers have a shared understanding of what to expect and when labour interventions are justified.

Objectives

To synthesise available evidence on the duration of latent and active first stage and the second stage of spontaneous labour in women at low risk of complications with ‘normal’ perinatal outcomes.

Search strategy

PubMed, EMBASE, CINAHL, POPLINE, Global Health Library, and reference lists of eligible studies.

Selection criteria

Observational studies and other study designs.

Data collection and analysis

Four authors extracted data on: maternal characteristics; labour interventions; duration of latent first stage, active first stage, and second stage of labour; and the definitions of onset of latent and active first stage, and second stage where reported. Heterogeneity in the included studies precluded meta-analysis and data were presented descriptively.

Main results

Thirty-seven studies reporting the duration of first and/or second stages of labour for 208,000 women met our inclusion criteria. Among nulliparous women, the median duration of active first stage (when the starting reference point was 4 cm) ranged from 3.7–5.9 h (95th percentiles: 14.5–16.7 h). With active phase starting from 5 cm, the median duration was from 3.8–4.3 h (95th percentiles: 11.3–12.7 h). The median duration of second stage ranged from 14 to 66 min (95th percentiles: 65–138 min) and from 6 to 12 min (95th percentiles: 58–76 min) in nulliparous and parous women, respectively. Sensitivity analyses excluding first and second stage interventions did not significantly impact on these findings

Conclusions

The duration of spontaneous labour in women with good perinatal outcomes varies from one woman to another. Some women may experience labour for longer than previously thought, and still achieve a vaginal birth without adverse perinatal outcomes. Our findings question the rigid limits currently applied in clinical practice for the assessment of prolonged first or second stage that warrant obstetric intervention.

Keywords: Normal labour, First and second stage of labour, Labour onset, Labour duration, Systematic review

Introduction

Despite the traditional division of labour into phases and stages for clinical convenience, what constitutes normal labour in terms of its progression and duration is not universal or standardized. This is in part related to the complexity of the onset of labour and the fact that transition between its phases and stages can only be objectively determined in retrospect. Evidence on the duration of the first stage of labour has largely been shaped by Friedman’s observations in the 1950s and 1960s when he subdivided the first stage of labour into an initial latent phase characterized by a slow progression in cervical dilatation up to 2 or 3 cm, followed by an active phase, when cervical dilatation rate significantly increases [[1], [2], [3]]. The time limits proposed from these studies became the benchmarks for assessment of normal labour progression [[4], [5], [6]] and the need for interventions to accelerate or terminate labour when it extends beyond these boundaries. However, over the past two decades, the prescribed duration of latent and active first stage, and second stage of labour, has increasingly been questioned as a result of new evidence suggesting that the description of labour progression that was proposed six decades ago may be inappropriate [[7], [8], [9], [10], [11], [12]].

The applicability of these safe time limits has become even more problematic in contemporary practice because of the variations in how onset of phases and stages of labour are defined. For instance, active first stage has been redefined through a recent professional consensus as starting from a cervical dilatation of 6 cm instead of 3 or 4 cm that has been traditionally applied [13]. Without a clear linkage between the definition and duration of phases and stages of labour, interventions to correct deviations from what is considered physiological progress of first and second stages [13] to prevent adverse maternal or neonatal outcomes may be unnecessary in some situations or even harmful [14].

The aim of this review was to synthesise available evidence on the duration of first (latent and active) and second stages of spontaneous labour in women without risk factors for complications and with good maternal and perinatal outcomes.

Methods

We conducted this review in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines, and followed a protocol (CRD42017054314) [15]. Eligible studies included all published and unpublished observational studies reporting on the duration of the first stage (discriminating whenever possible its latent and active phases) and the second stage of labour for women with low risk of complications with ‘normal’ perinatal outcomes. We considered other study designs (randomized trials and non-randomized studies) where these observations were reported for our population of interest. We included studies where the population was defined as ‘healthy women’, ‘women without risk factors for complications’, women deemed to be ‘low-risk’, or with clearly defined criteria including at the minimum singleton pregnancy, near term or term pregnancy, and cephalic presentation. ‘Normal perinatal outcomes’ were as defined by primary authors, but must include at least the birth of a live baby with Apgar score ≥7 at 5 min. We excluded studies involving women with induction of labour, morbidities or risk factors (e.g. gestational diabetes, hypertensive disorders, previous caesarean section), and those that applied ‘active management of labour’, or included first stage caesarean sections. Reviews, commentaries and letters were also excluded.

The outcomes of interest were the duration of the first stage (total, latent phase, and active phase) and the second stage of labour. We extracted information on the definitions of phases and stages of labour in terms of the characteristic features and reference points as reported by study authors, as well as baseline information and interventions during labour.

We searched PubMed, EMBASE, CINAHL, POPLINE, and Global Health Library using key concepts related to ‘spontaneous labour’, ‘labour onset’, ‘labour duration’, ‘cervical dilatation’, ‘labour pattern’, ‘latent phase’, ‘active phase’, ‘first stage of labour’, and ‘second stage of labour’. Searches for grey literature and bibliographies of related systematic reviews and eligible studies complemented the search strategies. There were no date or language restrictions. Details of the search strategy are presented in Box S1. Four review authors (EA, MC, VD and JP) independently screened the titles and abstracts, assessed the full texts of potentially eligible studies, and extracted data. Disagreements were resolved by discussion.

We extracted information on the duration of labour according to parity groups: nulliparous (parity = 0) and parous women (parity ≥ 1). For each parity group, we extracted the measure of central tendency and corresponding dispersion as reported by the authors according to latent first stage, active first stage, and second stage of labour. Given the significant methodological heterogeneity and variations in reporting format, data across studies were not meta-analysed but descriptively presented for each study according to the central measure of tendency (i.e. median and percentiles or mean and standard deviations). We reported upper limits of median as 95th percentiles (P95th) and upper limits of mean as mean + 2 standard deviations (2SD, the so called “statistical limits” or “statistical maximum”) as reported by the study authors. In situations where statistical limit is not reported for the mean, we deduced these values from the reported standard deviation.

The methodological quality of eligible studies was assessed to investigate internal validity (the extent to which the information is probably free of bias) and external validity (the extent to which the study provides the correct basis for applicability to other circumstances) with the following five attributes: intent of the study research question, representativeness of the study population, temporality of observations, adequacy of reference points and use of a valid measure of central tendency to report data (Table S1). Studies were graded as A, B or C if they were scored as low risk of bias in at least four, three or two or less of the five domains pre-specified above, respectively.

Results

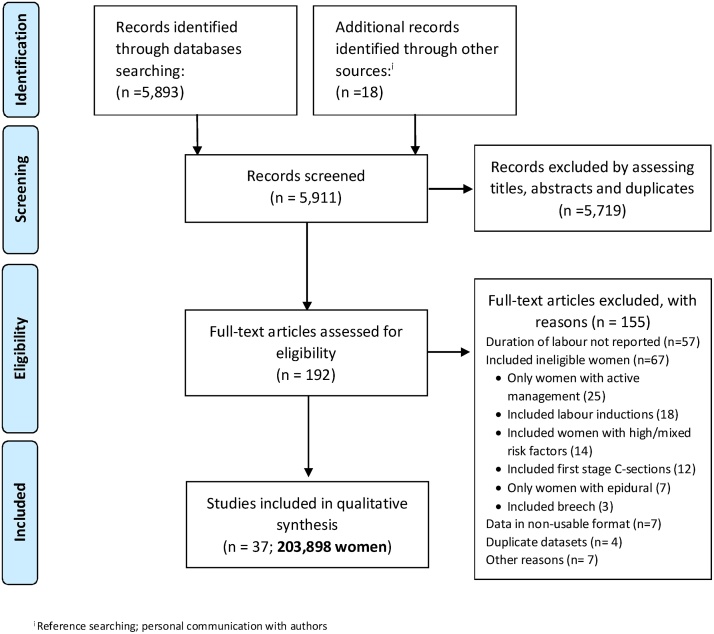

Fig. 1 summarises the process for identification and selection of eligible studies. From 5911 citations screened, 193 papers were selected for full-text review. Thirty-seven studies evaluating the duration of labour in 203,898 women met our inclusion criteria [[3], [7], [8], [9], [11], [12], [16], [17], [18], [19], [20], [21], [22], [23], [24], [25], [26], [27], [28], [29], [30], [31], [32], [33], [34], [35], [36], [37], [38], [39], [40], [41], [42], [43], [44], [45], [46]]. Thirty-two (75,081 women) reported the outcomes for nulliparous women and 29 (117,829 women) for parous women. In three studies (10,988 women) [[3], [27], [46]] parity was not reported separately, for that reason they were not included in the analysis of labour duration.

Fig. 1.

Detailed study selection process.

Characteristics of included studies and study populations

Tables S1 and S2 show the maternal and neonatal characteristics of nulliparous and parous women, respectively. Studies included women from different ethnic origins and socio-demographic backgrounds in 17 countries (China, Columbia, Croatia, Egypt, Finland, Germany, Israel, Japan, Korea, Myanmar, Nigeria, Norway, Taiwan, UK, Uganda, USA, and Zambia). Most of them (20/37) were relatively small, reporting data for a sample of 100 to 900 women, and only five were large (10,000 to more than 60,000 women). Seven studies were published in the 1960s and 1970s, 16 in the 1980s and 1990s, and 14 after year 2000.

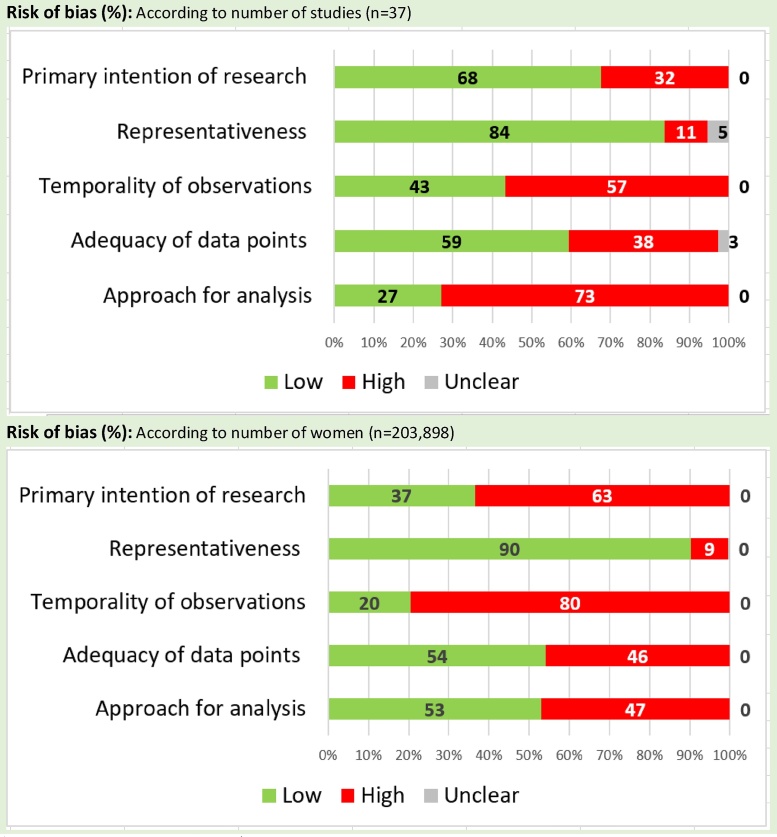

The overall quality of the studies was moderate to low. Ten studies were graded as A, 14 studies as B, and the remaining 13 as C. Fig. 2 shows the risk of bias for the five pre-specified domains according to the number of studies and number of women included in these studies.

Fig. 2.

Risk of bias of included studies.

Tables S3 and S4 show the baseline characteristics of women at labour admission, and the interventions received during labour according to parity. Many studies did not report the status of amniotic membranes, cervical effacement or cervical dilatation at labour admission. Although most studies reported the inclusion of women with spontaneous and normally evolving labours, some described the use of interventions such as amniotomy, oxytocin augmentation, and epidural analgesia with varying frequencies. Amniotomy varied from 0 to 60% (9 studies), oxytocin augmentation from 0 to 60% (29 studies), epidural use from 0 to 84% (30 studies), and instrumental vaginal birth from 0 to 73% (32 studies) in nulliparous women. In parous women, amniotomy ranged from 0 to 71% (8 studies), oxytocin augmentation from 0 to 45% (26 studies), epidural use from 0 to 77% (25 studies), and instrumental vaginal birth from 0 to 45% (28 studies).

Definition of phases and stages of labour

Overall, 28 studies reporting data for 185,408 women did not define labour or its onset. They only made a reference to ‘women in labour’ or ‘established labour’. Nine studies (18,490 women) provided a definition of spontaneous labour, such as cervical dilatation of 3 cm [19] or 4 cm [12] and effacement, or regular contractions within a 10-min period, [[29], [33], [40]] or regular contractions every 5 min with cervical changes [[7], [30]], or regular contractions plus a cervical dilatation of 4 cm, [18] or regular contractions with cervical changes (undefined) and effaced cervix or descent of the fetal head [27].

First stage of labour was defined in five studies as the time taken to reach full cervical dilatation from the initial examination [[22], [23], [26], [30]], or from the onset of regular contractions perceived by the woman up to the start of expulsive efforts at full dilatation [25]. Six studies defined the latent phase of first stage of labour. Although there was no consistent description of when it starts, in three studies, the authors confined its end to 2.5 cm [3], 3 cm [[16], [23]] or 4 cm [43] One study [26] defined the latent phase as the “duration of labour before presentation to hospital,” and another as the “length of time from the reported onset of regular contractions until the time of the examination where the slope of the cervical dilatation progress was greater than 1.2 cm per hour” [36]. The onset of active phase of first stage of labour was varyingly defined in 11 studies. In 10, it commenced at a cervical dilatation of 1.5 cm, [40] 2.5 cm [3], 3 cm, [16] 4 cm [[16], [17], [18], [28], [29], [38], [43]], or 5 cm [36] and ending at 10 cm (or full dilatation). In one study, it was defined as the “time spent to achieve full cervical dilatation from time of arrival in labour ward” [26].

Nine studies provided definitions of second stage of labour, six of them as the interval from full cervical dilatation to the expulsion of the baby [[12], [17], [18], [20], [30], [38]]. In the other three the definition included the predicted or confirmed full dilatation or the time of maternal spontaneous pushing, whichever occurred first, until expulsion of the baby [[22], [24], [35]].

Duration of labour

Latent first stage (nulliparous and parous women)

In nulliparous, two studies reported the median duration of the latent first stage lasting from 6.0–7.5 h but without reporting the corresponding P95th (Table 1). Another two studies reported the mean duration as 5.1–7.1 h with statistical limits of 10.3–11.5 h. For parous women, the median duration reported by three studies ranged from 4.5–5.5 h without recording P95th; and in three other studies, mean duration was 2.2–5.7 h with statistical limits ranging from 5.4–8.7 h.

Table 1.

Duration of latent phase, nulliparous and parous women.

|

Nulliparous women | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | N | Study quality | Cervical dilatation on admission (cm) | Definition of starting and ending reference points | Median duration (h) | 5th percentile (h) | 95th percentile (h) |

| Peisner 1983a36 | 1544 | A | 0.5** | Reported onset of contractions until slope of labour record > 1.2 cm/h | 7.5 | – | – |

| Ijaiya 2009a26 | 75 | B | 5** | Duration of labour before presentation | 6.0 | – | – |

| Mean duration (h) | SD (h) | +2SD (h) | |||||

| Juntunen 1994a29 | 42 | B | NR | Not defined | 5.1 | 3.2 | 11.5 |

| Velasco 1985a43 | 74 | B | NR | From admission until 4 cm | 7.1 | 1.6 | 10.3 |

| Parous women | |||||||

| Peisner 1983b36(P = 1) | 720 | A | 4.5** | Reported onset of contractions until slope of labour record > 1.5 cm/h | 5.5 | – | – |

| Peisner 1983c36(P ≥ 1) | 581 | A | 4.5** | Reported onset of contractions until slope of labour record > 1.5 cm/h | 4.5 | – | – |

| Ijaiya 2009b26 | 163 | B | 6** | Duration of labour before presentation | 5.0 | – | – |

| Mean duration (h) | SD (h) | +2SD (h) | |||||

| Juntunen 1994b29(P = 2/3) | 42 | B | NR | Not defined | 3.2 | 2.3 | 7.8* |

| Juntunen 1994c29(P > 3) | 42 | B | NR | Not defined | 2.2 | 1.6 | 5.4* |

| Velasco 1985b43 | 37 | B | NR | From admission until 4 cm | 5.7 | 1.5 | 8.7* |

Estimated by authors.

Median; P = Parity.

Active first stage (nulliparous and parous women)

Among nulliparous, three studies suggest that the median duration of active first stage (when the starting reference point was less than 4.5 cm) ranged from 3.7–8.4 h (P95th: 14.5–20.0 h) (Table 2). With reference point starting from 5 cm, two studies reported the median duration of 3.8–4.3 h (P95th:11.3–12.7 h). The only study recording 6 cm as the starting reference point showed a median duration of 2.9 h (P95th: 9.5 h). From studies reporting means, duration of active first stage starting from 2.5 to 4 cm was 3.1–7.7 h, with statistical limits of 6.1–19.4 h in 6 studies. In a small study (18 women), mean duration of active first stage was 15.4 h (statistical limit of 28.6 h) in women from the control group admitted at 5.4 cm mean cervical dilatation. The remaining study did not report cervical dilatation at admission nor the starting points for active first stage.

Table 2.

Duration of active phase, nulliparous women.

|

Nulliparous women | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | N | Study quality | Cervical dilatation on admission (cm) | Amniotomy (%) | Oxytocin (%) | Epidural (%) | Definition of starting and ending reference points | Median duration (h) | 5th percentile (h) | 95th percentile (h) |

| Zhang 2010 (2)-19 | 4247 | B | 2–2.5** | NR | 47* | 8* | From 2 (or 2.5) to 10 cm | 8.4 | – | 20.0 |

| Zhang 2010 (2)-29 | 6096 | B | 3–3.5** | NR | 47* | 8* | From 3 (or 3.5) to 10 cm | 6.9 | – | 17.4 |

| Zhang 2010 (1)11 | 8690 | B | 3** | NR | 20 | 8 | From 4 to 10 cm | 3.7 | – | 16.7 |

| Oladapo 2018-134 | 715 | A | 4** | NR | 40* | 0.0 | From 4 to 10 cm | 5.9 | 2.4 | 14.5 |

| Zhang 2010 (2)-39 | 5550 | B | 4–4.5** | NR | 47* | 8* | From 4 (or 4.5) to 10 cm | 5.3 | – | 16.4 |

| Oladapo 2018-234 | 316 | A | 5** | NR | 40* | 0.0 | From 5 to 10 cm | 4.3 | 1.6 | 11.3 |

| Zhang 2010 (2)-49 | 2764 | B | 5–5.5** | NR | 47* | 84* | From 5 (or 5.5) to 10 cm | 3.8 | – | 12.7 |

| Oladapo 2018-334 | 322 | A | 6** | NR | 40* | 0.0 | From 6 to 10 cm | 2.9 | 0.9 | 9.3 |

| Mean duration (h) | SD (h) | +2SD (h) | ||||||||

| Schiff 199838 | 69 | B | 3.5*** | NR | NR | NR | From 4 to 10 cm | 4.7 | 2.6 | 9.9* |

| Albers 199917 | 806 | A | 4*** | 0.0 | 0.0 | NR | From 4 to 10 cm | 7.7 | 4.9 | 17.5 |

| Jones 200328 | 120 | B | 4*** | NR | 0.0 | 0.0 | From 4 to 10 cm | 6.2 | 3.6 | 13.4 |

| Albers 199618 | 347 | C | 4*** | NR | 0.0 | NR | From 4 to 10 cm | 7.7 | 5.9 | 19.4 |

| Velasco 198543 | 74 | B | NR | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | From 4 to 10 cm | 3.9 | 1.6 | 7.1* |

| Juntunen 199429 | 42 | B | NR | 57.1 | 0.0 | 42.9 | From 4 to 10 cm | 3.1 | 1.5 | 6.1* |

| Lee 200731 | 66 | C | 2.5*** | NR | NR | 0.0 | NR | 3.6 | 1.9 | 7.4* |

| Schorn 199339 | 18 | B | 5.4*** | NR | 18 | NR | NR | 15.4 | 6.6 | 28.6 |

| Kilpatrick 198930 | 2032 | C | NR | NR | 0.0 | 0.0 | NR | 8.1 | 4.3 | 16.7* |

Risk of bias: A = at least four (out of five) domains scored as low risk; B = three domains scored as low risk; C = two domains or less scored as low risk.

SD = Standard deviation.

NR = Not reported.

h = h.

Estimated by authors.

Median.

Mean.

For parous women, two studies suggest that the median duration of active phase with onset defined as 3.5 or 4 cm ranged from 2.2–4.7 h (P95th: 13.0–14.2 h) (Table 3). One study with reference points starting from 5 cm reported median duration of 3.1–3.4 h (P95th 10.1–10.8 h), and 2.2–2.4 h (P95th:7.4–7.5 h) when the starting reference point was 6 cm. For eight studies presenting means, duration of active phase when defined from 4 cm was 2.1–5.7 h, with statistical limits from 4.9–13.8 h. One study in this category did not report the starting points for active first stage, nor the cervical dilatation at admission. In Schorn et al.,[39] parous women also showed longer labours (mean 13.2 h, 2SD: 23.9 h).

Table 3.

Duration of active phase, parous (≥1) women.

|

Parous women | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | N | Study quality | Cervical dilatation on admission (cm) | Amniotomy (%) | Oxytocin (%) | Epidural (%) | Definition of starting and ending reference points | Median duration (h) | 5th percentile (h) | 95th percentile (h) |

| Zhang 2010 (1)11(P = 1) | 6373 | B | 3.5** | NR | 20.0 | 11 | From 4 to 10 cm | 2.4 | – | 13.8 |

| Zhang 2010 (1)11(P ≥ 2) | 11765 | B | 3.5** | NR | 12.0 | 8 | From 4 to 10 cm | 2.2 | – | 14.2 |

| Oladapo 2018-434(P = 1) | 491 | A | 4** | NR | 29.8* | 0.1 | From 4 to 10 cm | 4.6 | 1.7 | 13.0 |

| Oladapo 2018-534(P ≥ 2) | 626 | A | 4** | NR | 26.7* | 0.0 | From 4 to 10 cm | 4.7 | 1.7 | 13.0 |

| Oladapo 2018-634(P = 1) | 292 | A | 5** | NR | 29.8* | 0.1 | From 5 to 10 cm | 3.4 | 1.2 | 10.1 |

| Oladapo 2018-734(P ≥ 2) | 385 | A | 5** | NR | 26.7* | 0.0 | From 5 to 10 cm | 3.1 | 0.9 | 10.8 |

| Oladapo 2018-834(P = 1) | 320 | A | 6** | NR | 29.8* | 0.1 | From 6 to 10 cm | 2.2 | 0.6 | 7.5 |

| Oladapo 2018-934(P ≥ 2) | 414 | A | 6** | NR | 26.7* | 0.0 | From 6 to 10 cm | 2.4 | 0.8 | 7.4 |

| Mean duration (h) | SD (h) | +2SD (h) | ||||||||

| Schiff 199838 | 94 | B | 3.5*** | NR | NR | NR | From 4 to 10 cm | 3.3 | 1.9 | 7.1* |

| Albers 199917 | 1705 | A | 4*** | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | From 4 to 10 cm | 5.6 | 4.1 | 13.8 |

| Jones 200328 | 120 | B | 4*** | NR | 0.0 | 0.0 | From 4 to 10 cm | 4.4 | 3.4 | 11.6 |

| Albers 199617 | 602 | C | 4*** | NR | NR | NR | From 4 to 10 cm | 5.7 | 4.0 | 13.7 |

| Velasco 198543 | 37 | B | NR | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | From 4 to 10 cm | 2.1 | 1.4 | 4.9* |

| Juntunen 199429(P = 2/3) | 42 | B | NR | 69.0 | 0.0 | 2.4 | From 4 to 10 cm | 2.7 | 1.4 | 5.5* |

| Juntunen 199429(GP) | 42 | B | NR | 71.4 | 0.0 | 9.5 | From 4 to 10 cm | 2.8 | 1.5 | 5.8* |

| Schorn 199328 | 30 | B | 5.3*** | NR | 18 | NR | NR | 13.2 | 5.3 | 23.9 |

| Kilpatrick 198930 | 3767 | C | NR | NR | NR | 0.0 | NR | 5.7 | 3.4 | 12.5 |

Risk of bias: A = at least four (out of five) domains scored as low risk; B = three domains scored as low risk; C = two domains or less scored as low risk.

SD = Standard deviation.

NR = Not reported.

P = Parity.

GP = Grand parity.

h = h.

Estimated by authors.

Median.

Mean.

Sensitivity analyses were conducted by excluding studies reporting interventions aimed at shortening labour (augmentation, instrumental vaginal birth and intrapartum caesarean section) (Table S5). Studies reporting amniotomy and epidural analgesia remained in the analysis as they could have other indications, such as internal fetal monitoring or pain relief. Sensitivity analyses did not significantly impact on our observations in the entire dataset.

Second stage of labour (nulliparous and parous women)

Four studies reported the median duration of second stage in nulliparous ranging from 14 to 66 min [0.2–1.1 h], P95th: 65–138 min [1.1–2.3 h] (Table 4). Two of these studies with epidural use at 48 and 100% reported a relatively longer median duration (53–66 min [0.9–1.1 h], P95th: 138–216 min [2.3–3.6 h]). Seventeen studies reported means from 20 to 116 min [0.3–1.9 h], with statistical limits of 78–216 min [1.3–3.6 h]. In one of these studies 42.9% of women received epidural and reported mean duration of 20 min [0.3 h] with statistical limits of 60 mins [1 h]. The other with 4.1% epidural use reported mean duration of 40 min [0.7 h] with no statistical limits reported.

Table 4.

Duration of second stage, nulliparous women.

|

Nulliparous women | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | N | Study quality | Epidural analgesia (%) | Definition of starting reference points | Median duration (min) |

5th percentile (min) |

95th percentile (min) |

| Oladapo 201834 | 2166 | A | 0 | 10 cm to birth | 14 | 3.0 | 65 |

| Zhang 2010(2)-19 | 4100 | B | 0 | 10 cm to birth | 36 | – | 168 |

| Zhang 200212 | 1162 | A | 48 | 10 cm to birth | 53 | 18 | 138* |

| Zhang 2010(2)-29 | 21524 | B | 100 | 10 cm to birth | 66 | – | 216 |

| Paterson 199235 | 8270 | C | 0 | 10 cm or urge to bear down | 45 | – | – |

| Mean duration (min) | SD (min) | +2SD (min) | |||||

| Albers 199917 | 806 | A | 0.0 | 10 cm to birth | 54 | 46 | 146 |

| Diegmann 2000-120 | 373 | C | 0.0 | 10 cm to birth | 32 | 23 | 78* |

| Diegmann 2000-220 | 157 | C | 0.0 | 10 cm to birth | 44 | 33 | 110* |

| Kilpatrick 198930 | 2032 | C | 0.0 | 10 cm to birth | 54 | 39 | 132* |

| Schiff 199838 | 69 | B | NR | 10 cm to birth | 66 | 36 | 138* |

| Albers 199618 | 347 | C | NR | 10 cm to birth | 53 | 47 | 147 |

| Duignan 197522 | 437 | B | 0.0 | 10 cm or urge to bear down | 42 | – | – |

| Abdel-Aleem 199116 | 175 | A | 0.0 | Undefined | 43 | 24 | 91* |

| Chen 198619 | 500 | B | 0.0 | Undefined | 43 | – | – |

| Jones 200328 | 120 | B | 0.0 | Undefined | 54 | 43 | 140* |

| Studd 197341 | 176 | B | 0.0 | Undefined | 46 | – | – |

| Lee 200731 | 66 | C | 0.0 | Undefined | 54 | 34 | 122* |

| Wusteman 200345 | 66 | C | 0.0 | Undefined | 36 | 5 | 46 |

| Studd 197542 | 194 | A | 4.1 | Undefined | 40 | – | – |

| Juntunen 199429 | 42 | B | 42.9 | Undefined | 20 | 20 | 60* |

| Schorn 199339 | 18 | B | NR | Undefined | 66 | 54 | 174 |

| Dior 201321 | 12631 | C | NR | Undefined | 78 | – | – |

| Shi 20167 | 1091 | C | NR | Undefined | 116 | 50 | 216 |

Risk of bias: A = at least four (out of five) domains scored as low risk; B = three domains scored as low risk; C = two domains or less scored as low risk

NR = Not reported.

SD = Standard deviation.

min = min.

Estimated by authors.

For parous women, two studies reported the median duration of second stage from 6 to 12 mins [0.1–0.2 h], P95th: 58–76 min [1.0–1.3 h] (Table 5). The subpopulation of women with 100% epidural in one of these studies had longer median duration of 18–24 min [0.3–0.4 h], P95th: 96–120 min [1.6–2.0 h]. Fifteen studies reporting data as mean show mean duration of second stage ranging from 6 to 30 min [0.1–0.5 h] with statistical limits of 16–78 min [0.3–1.3 h]. Only four of these studies clearly defined the starting reference point for the second stage. Three studies reported epidural use in 2.4%, 4.3% and 9.5% of women.

Table 5.

Duration of second stage, parous (≥1) women.

|

Parous women | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | N | Study quality | Epidural analgesia (%) | Definition of starting reference points | Median duration (min) | 5th percentile (min) | 95th percentile (min) |

| Oladapo 201834(P = 1) | 1488 | A | 0.1 | 10 cm to birth | 11 | 2 | 65 |

| Oladapo 201834(P ≥ 2) | 1952 | A | 0 | 10 cm to birth | 11 | 2 | 58 |

| Zhang 2010 (2)-19(P = 1) | 4106 | B | 0 | 10 cm to birth | 12 | – | 76 |

| Zhang 2010 (2)-19(P ≥ 2) | 4001 | B | 0 | 10 cm to birth | 6 | – | 66 |

| Zhang 2010 (2)-29(P = 1) | 12649 | B | 100 | 10 cm to birth | 24 | – | 120 |

| Zhang 2010 (2)-29(P ≥ 2) | 12218 | B | 100 | 10 cm to birth | 18 | – | 96 |

| Mean duration (min) | SD (min) | +2SD (min) | |||||

| Albers 199917 | 1705 | A | 0 | 10 cm to birth | 18 | 23 | 64* |

| Kilpatrick 198930 | 3767 | C | 0 | 10 cm to birth | 19 | 21 | 61* |

| Albers 199618 | 602 | C | NR | 10 cm to birth | 17 | 20 | 57* |

| Duignan 197522 | 869 | B | 0 | 10 cm or urge to bear down | 17.4 | – | – |

| Abdel-Aleem 199116 | 372 | A | 0 | Undefined | 29 | 16 | 61* |

| Jones 200328 | 120 | B | 0 | Undefined | 22 | 28 | 78* |

| Studd 197341 | 264 | B | 0 | Undefined | 22 | – | – |

| Paterson 199235 | 13159 | C | 0 | Undefined | 19 | 21 | 61 |

| Wusteman 200345 | 71 | C | 0 | Undefined | 16 | 21 | 58* |

| Juntunen 199429(P = 2/3) | 42 | B | 2.4 | Undefined | 8.7 | 5.5 | |

| Studd 197545 | 322 | A | 4.3 | Undefined | 19 | – | – |

| Juntunen 199429(GP) | 42 | B | 9.5 | Undefined | 6 | 5 | 16* |

| Schiff 199838 | 94 | B | NR | Undefined | 30 | 24 | 78* |

| Schorn 199339 | 30 | B | NR | Undefined | 24 | 24 | 72 |

| Gibb 198223 | 749 | C | NR | Undefined | 17 | – | – |

| Dior 201321(P = 2/5) | 27252 | C | NR | Undefined | 21 | – | – |

| Dior 201321(P ≥ 6) | 4112 | C | NR | Undefined | 16 | – | – |

Risk of bias: A = at least four (out of five) domains scored as low risk; B = three domains scored as low risk; C = two domains or less scored as low risk.

NR = Not reported.

SD = Standard deviation.

min = min.

P = Parity.

GP = Grand parity.

Estimated by authors.

Sensitivity analysis excluding second stage interventions also shows similar range of values (Table S6).

Discussion

Main findings

Our study provides an up-to-date overview of how the duration of spontaneous labour in healthy women with good perinatal outcomes was reported in the literature. Clear reference points for the assessment of duration of labour were generally not provided by primary study authors and where they were, there are differences in the way the onset of phases and stages of labour were defined. Nonetheless, some patterns emerged. When beginning at 4 cm cervical dilatation (commonly associated with active labour onset), the median duration of active first stage was approximately 4–8 h in nulliparous with upper limits of up to 20 h, and 4 h (up to 13 h) when active phase onset was defined by cervical dilatation of 5 cm. In parous women, when beginning at 4 cm cervical dilatation, the median duration was approximately 2–5 h with an upper limit of up to 14 h, and 3 h (up to 11 h) when starting point is defined at 5 cm. In nulliparous, the second stage was often completed within 1 h but could take close to 4 h in women with epidural analgesia. Likewise, the second stage in parous women was usually completed in less than half an hour but could take up to 2 h in women with epidural analgesia. Exclusion of studies with accelerative labour interventions and second stage interventions did not significantly impact on these findings.

Strength and limitations

All major datasets of women at low risk of labour complications with normal perinatal outcomes, evaluating more than 200,000 women from different ethnic and demographic backgrounds representing many regions and socio-economic settings were included. However, the quality of the results and conclusions from a systematic review are only as accurate and robust as the data provided by the primary datasets. The main limitation of this review relates to the considerable heterogeneity in the way primary authors defined the reference points for labour phases and stages, and how they measured and reported their duration. It is possible that what some authors assessed as active phase had included a variable period of time considered by others as part of the latent phase. Other important limitation is the poor and inconsistent reporting of other factors that could potentially affect labour duration such as maternal characteristics at admission and use of labour interventions.

Interpretation

When the onset of labour is determined differently, diverse views are expected about the time needed to complete birth. Apart from the fact that the duration and features of the latent phase was reported in few studies, the point at which it truly commenced was ambiguously reported, from self-perception of regular contractions by women at home to a given cervical dilatation confirmed by a health professional at hospital admission. Despite the very low certainty of the evidence, the reported data compares favourably with the observations in Friedman’s pioneer work (1, 2) on ‘normal’ duration of labour (which did not meet the inclusion criteria for our review as Friedman’s studies also included women with twins, breech presentations, and perinatal deaths – a set of risk factors and outcomes that could complicate the interpretation and applicability of our results to clinical practice). Similar to our findings, Friedman reported the duration of latent phase in nulliparous women as mean: 8.6 h; median: 7.5 h; and “statistical maximum”: 20.6 h; and in parous women reported mean of 5.3 h; median 4.5 h; and statistical maximum of 13.6 h. As stated by other authors [[47], [48]], there is little consensus on the degree of cervical dilatation or the pattern of uterine contractions to define when the latent phase ends and active phase begins. More recent studies [[7], [9], [11], [12], [34], [49]] did not find the inflection point defined by Friedman at 2 to 3 cm dilatation, but rather a smoother transition at later stages of cervical dilatation. Understanding when this transition takes place is important as women who are managed according to current standards of care for active first stage are likely to receive more labour interventions, such as electronic fetal monitoring, epidural analgesia, oxytocin, and caesarean section [[50], [51], [52]]. The same uncertainties apply for determining when second stage of labour truly begins. It was not possible in most studies to precisely determine when a woman reached full cervical dilatation, and it is probable that many were already in the second stage for longer periods by the time they were assessed.

Diagnosis of progression and normality only can be made retrospectively, so it is not possible to predict if a particular woman in labour fits under specified parameters. On the other hand, the majority of descriptions defined the phases and stages of labour by cervical assessment over time, as defined by health professionals, which may not reflect women’s own perceptions or expectations on when and how labour starts and progresses [53].

The statistical methods used to report a central tendency and its dispersion varied across studies, and were not consistently reported. Most studies reported mean and standard deviations. It has been shown, however, that labour duration may not hold to a statistically normal curve, as there is a tendency for longer labours to positively skew the statistical distribution [54]. Thus, median labour duration is regarded as a superior measure of central tendency than the means, which is more susceptible to these slowest but yet normal labours [54]. For this reason, the data presented as means and the corresponding statistical limits should be interpreted with caution.

It is interesting to note that while the median times reported for active first stage of labour in both nulliparous and parous women reflect what one would expect if the cervix were dilating at least at the rate of 1 cm/hour, the 95th percentile times suggest a much longer duration. In nulliparous, active first stage extending beyond 12 h is often described as “prolonged labour” and interventions to terminate labour process may be considered justified. In the light of our results, it would be reasonable to take a more expectant and supportive approach, when there is some evidence of labour progression, provided maternal and fetal conditions are reassuring. The application of limits of labour duration as informed by the respective 95th percentile thresholds as the benchmark for identifying unduly prolonged labour might be cost-effective as it has the potential to reduce the use of interventions to accelerate labour and birth. However, it might increase costs associated with the provision of supportive care such as pain relief, and labour companionship required for women to tolerate slightly longer but normal labours.

Conclusions

The duration of phases and stages of labour varies from one woman to another, and is dependent on the reference point used to signify onset. Given the limits within which women could still achieve full cervical dilatation and give birth without adverse perinatal outcomes, the decision to intervene whenever the first stage of labour appears prolonged must not be taken on the basis of duration alone. Health professional should aim to support pregnant women to experience labour and childbirth according to individual woman’s own natural reproductive processes without interventions to shorten the duration, provided the conditions of both mother and baby are reassuring, there is evidence of progression, and the duration remains within the upper limits presented in this review. Future studies on the duration of first stage labour would benefit from an agreement on reporting other elements, including the patterns of uterine contractions, cervical effacement, fetal station, that should be considered either alone or in combination in defining the onset of phases and stages of labour.

Contribution to authorship

OTO, EA, MB and AMG conceived the general aims and objectives of the review, and agreed on the analyses plan. EA drafted the protocol with input from MB, OTO, JPS and AMG. EA, MC, VD, JP built the search strategies, ran the searches, assessed the papers for eligibility and extracted data. EA performed the data analyses with inputs from all authors and wrote the first draft of the paper. All authors contributed to revising the final version. EA is the guarantor. All authors approved the manuscript for publication.

Funding

OTO, MB, JPS and AMG are staff of the UNDP/UNFPA/UNICEF/WHO/World Bank Special Programme of Research, Development and Research Training in Human Reproduction (HRP), Department of Reproductive Health and Research (RHR), World Health Organization, which commissioned the review. EA, MC, VD and JP are staff of CREP, Rosario, Argentina, which received funds to execute these systematic reviews from the World Health Organization, as part of evidence base preparation towards the WHO recommendations on intrapartum care for a positive childbirth experience.

Conflicts of interest

OTO participated in a large unpublished study on labour monitoring and action with a component that included cervical dilatation patterns during labour in African women. Other members of the review team have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Dr Qian Long for her help in translating papers from Chinese. We are grateful to Tomas Allen and José Garnica, the Information Specialists at the World Health Organizatiotablen, Geneva, Switzerland, for reviewing the search strategies.

Footnotes

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejogrb.2018.02.026.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Friedman E.A. Primigravid labor; a graphicostatistical analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 1955;6(6):567–589. doi: 10.1097/00006250-195512000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Friedman E.A. Labor in multiparas; a graphicostatistical analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 1956;8(6):691–703. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Friedman E.A., Kroll B.H. Computer analysis of labour progression. J Obstet Gynaecol Br Commonw. 1969;76(12):1075–1079. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1969.tb05788.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Friedman E.A., Sachtleben M.R. Dysfunctional labor. II. Protracted active-phase dilatation in the nullipara. Obstet Gynecol. 1961;17:566–578. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Friedman E.A., Sachtleben M.R. Dysfunctional labor. I. Prolonged latent phase in the nullipara. Obstet Gynecol. 1961;17:135–148. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Friedman E.A., Kroll B.H. Computer analysis of labor progression. II. Distribution of data and limits of normal. J Reprod Med. 1971;6(1):20–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shi Q., Tan X.Q., Liu X.R., Tian X.B., Qi H.B. Labour patterns in Chinese women in Chongqing. BJOG: Int J Obstet Gynaecol. 2016;123(Suppl. 3):57–63. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.14019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Suzuki R., Horiuchi S., Ohtsu H. Evaluation of the labor curve in nulliparous Japanese women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;203(3):e1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2010.04.014. 226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang J., Landy H.J., Branch D.W., Burkman R., Haberman S., Gregory K.D. Contemporary patterns of spontaneous labor with normal neonatal outcomes. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116(6):1281–1287. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181fdef6e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang J., Landy H.J., Branch W., Burkman R., Haberman S., Gregory K.D. Contemporary patterns of spontaneous labor with normal neonatal outcomes. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2011;66(3):132–133. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181fdef6e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang J., Troendle J., Mikolajczyk R., Sundaram R., Beaver J., Fraser W. The natural history of the normal first stage of labor. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;115(4):705–710. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181d55925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang J., Troendle J.F., Yancey M.K. Reassessing the labor curve in nulliparous women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;187(4):824–828. doi: 10.1067/mob.2002.127142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.American College of O, Gynecologists, Society for Maternal-Fetal M. Caughey, A.B. Cahill, A.G. Guise, J.M. et al., Safe prevention of the primary cesarean delivery. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology, 210 (3) (2014)179–93. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Miller S., Abalos E., Chamillard M., Ciapponi A., Colaci D., Comande D. Beyond too little, too late and too much, too soon: a pathway towards evidence-based, respectful maternity care worldwide. Lancet. 2016;388(10056):2176–2192. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31472-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.E.B.M. Abalos, M. Chamillard, V. Diaz, O.T. Oladapo J. Pasquale, Definitions of phases and stages of spontaneous labour in ‘low-risk’ women with normal perinatal outcomes: a systematic review protocol, PROSPERO CRD42017054314. 2017.

- 16.Abdel Aleem H. Nomograms of cervical dilatation and characteristics of normal labor in Upper Egypt. Assiut Med J. 1991;15(4):19–30. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Albers L.L. The duration of labor in healthy women. J Perinatol. 1999;19(2):114–119. doi: 10.1038/sj.jp.7200100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Albers L.L., Schiff M., Gorwoda J.G. The length of active labor in normal pregnancies. Obstet Gynecol. 1996;87(3):355–359. doi: 10.1016/0029-7844(95)00423-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen H.F., Chu K.K. Double-lined nomogram of cervical dilatation in Chinese primigravidas. Acta obstetricia et gynecologica Scandinavica. 1986;65(6):573–575. doi: 10.3109/00016348609158389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Diegmann E.K., Andrews C.M., Niemczura C.A. The length of the second stage of labor in uncomplicated, nulliparous African American and Puerto Rican women. J Midwifery Women Health. 2000;45(1):67–71. doi: 10.1016/s1526-9523(99)00019-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dior U.K.L., Ezra Y., Calderon-Margalit R. Population based labor curves. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2013;(Suppl):S150–151. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Duignan N.M., Studd J.W., Hughes A.O. Characteristics of normal labour in different racial groups. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1975;82(8):593–601. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1975.tb00695.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gibb D.M., Cardozo L.D., Studd J.W., Magos A.L., Cooper D.J. Outcome of spontaneous labour in multigravidae. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1982;89(9):708–711. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1982.tb05095.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gross M.M., Drobnic S., Keirse M.J. Influence of fixed and time-dependent factors on duration of normal first stage labor. Birth. 2005;32(1):27–33. doi: 10.1111/j.0730-7659.2005.00341.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gross M.M., Petersen A., Hille U., Hillemanns P. Association between women's self-diagnosis of labor and labor duration after admission. J Perinat Med. 2010;38(1):33–38. doi: 10.1515/jpm.2010.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ijaiya M.A., Aboyeji A.P., Fakeye O.O., Balogun O.R., Nwachukwu D.C., Abiodun M.O. Pattern of cervical dilatation among parturients in Ilorin, Nigeria. Ann Afr Med. 2009;8(3):181–184. doi: 10.4103/1596-3519.57243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Johnson N., Lilford R., Guthrie K., Thornton J., Barker M., Kelly M. Randomised trial comparing a policy of early with selective amniotomy in uncomplicated labour at term. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1997;104(3):340–346. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1997.tb11465.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jones M., Larson E. Length of normal labor in women of Hispanic origin. J Midwifery Women Health. 2003;48(1):2–9. doi: 10.1016/s1526-9523(02)00367-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Juntunen K., Kirkinen P. Partogram of a grand multipara: different descent slope compared with an ordinary parturient. J Perinat Med. 1994;22(3):213–218. doi: 10.1515/jpme.1994.22.3.213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kilpatrick S.J., Laros R.K., Jr. Characteristics of normal labor. Obstet Gynecol. 1989;74(1):85–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee S.W., Yang J.H., Cho H.J., Hong D.S., Kim M.Y., Ryu H.M. The effects of epidural analgesia on labor progress and perinatal outcomes. Korean J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;50(10):1330–1335. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mya Mya D.A.T.D., Sann Yee S. Partogram and nomogram of cervical dilatation in multigravidae. Bur Med J. 1980;26(4):263–270. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nesheim B.I. Duration of labor: an analysis of influencing factors. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1988;67(2):121–124. doi: 10.3109/00016348809004182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Oladapo O.T., Souza J.P., Fawole B., Mugerwa K., Perdona G., Alves D. Progression of the first stage of spontaneous labour: a prospective cohort study in two sub Saharan African countries. PLoS Med. 2018;15(1):e1002492. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Paterson C.M., Saunders N.S., Wadsworth J. The characteristics of the second stage of labour in 25,069 singleton deliveries in the North West Thames Health Region, 1988. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1992;99(5):377–380. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1992.tb13752.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Peisner D.B., Rosen M.G. Latent phase of labor in normal patients: a reassessment. Obstet Gynecol. 1985;66(5):644–648. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rajhvajn B., Kurjak A., Latin V., Barsic E. Construction and use of a partograph in the management of labour. Z Geburtshilfe Perinatol. 1974;178(1):58–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schiff E., Cohen S.B., Dulitzky M., Novikov I., Friedman S.A., Mashiach S. Progression of labor in twin versus singleton gestations. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1998;179(5):1181–1185. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(98)70128-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schorn M.N., McAllister J.L., Blanco J.D. Water immersion and the effect on labor. J Nurse Midwifery. 1993;38(6):336–342. doi: 10.1016/0091-2182(93)90014-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Steward P. Introduction of partographic records in a District Hospital in Zambia and development of nomograms of cervical dilatation. Med J Zambia. 1977;11(4):97–99. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Studd J. Partograms and nomograms of cervical dilatation in management of primigravid labour. Br Med J. 1973;4(5890):451–455. doi: 10.1136/bmj.4.5890.451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Studd J., Clegg D.R., Sanders R.R., Hughes A.O. Identification of high risk labours by labour nomogram. Br Med J. 1975;2(5970):545–547. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.5970.545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Velasco A.F.A., Reyes F. Nomograma de la dilatación del cervix en el parto. Rev Colomb Obstet Ginecol. 1985;36(5):323–327. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Woraschk H.J., Ehinger B., Roepke F. Dynamics of cervix dilatation during labor. Zentralblatt Gynakol. 1978;100(18):1173–1177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wüstemann M., Gremm B., Scharf A., Sohn C. Influence of the » walking epidural « on duration of labour in primi- and multiparae with vaginal delivery and comparison of vaginal operative delivery rates. Gynakol Praxis. 2003;27(3):433–439. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wu P. Clinical study on early artificial rupture of fetal membrane to shorten the stages of labor. Zhonghua Hu Li Za Zhi. 1994;29(12):714–715. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hanley G.E., Munro S., Greyson D., Gross M.M., Hundley V., Spiby H. Diagnosing onset of labor: a systematic review of definitions in the research literature. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2016;16:71. doi: 10.1186/s12884-016-0857-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Blix E., Kumle M., Oian P. What is the duration of normal labour? Tidsskrift for den Norske laegeforening: tidsskrift for praktisk medicin, ny raekke. 2008;128(6):686–689. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Oladapo O.T., Diaz V., Bonet M., Abalos E., Thwin S.S., Souza H. Cervical dilatation patterns of ‘low-risk' women with spontaneous labour and normal perinatal outcomes: a systematic review. BJOG. 2017;(September) doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.14930. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bailit J.L., Dierker L., Blanchard M.H., Mercer B.M. Outcomes of women presenting in active versus latent phase of spontaneous labor. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105(1):77–79. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000147843.12196.00. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Holmes P., Oppenheimer L.W., Wen S.W. The relationship between cervical dilatation at initial presentation in labour and subsequent intervention. BJOG. 2001;108(11):1120–1124. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2003.00265.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tilden E.L., Lee V.R., Allen A.J., Griffin E.E., Caughey A.B. Cost-Effectiveness analysis of latent versus active labor hospital admission for medically low-risk, term women. Birth. 2015;42(3):219–226. doi: 10.1111/birt.12179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dixon L., Skinner J., Foureur M. Women's perspectives of the stages and phases of labour. Midwifery. 2013;29(1):10–17. doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2012.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Vahratian A., Troendle J.F., Siega-Riz A.M., Zhang J. Methodological challenges in studying labour progression in contemporary practice. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2006;20(1):72–78. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3016.2006.00696.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.