Abstract

Objectives

To describe the implementation of a trigger tool in Sweden and present the national incidence of adverse events (AEs) over a 4-year period during which an ongoing national patient safety initiative was terminated.

Design

Cohort study using retrospective record review based on a trigger tool methodology.

Setting and participants

Patients ≥18 years admitted to all somatic acute care hospitals in Sweden from 2013 to 2016 were randomised into the study.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

Primary outcome measure was the incidence of AEs, and secondary measures were type of injury, severity of harm, preventability of AEs, estimated healthcare cost of AEs and incidence of AEs in patients cared for in another type of unit than the one specialised for their medical needs (‘off-site’).

Results

In a review of 64 917 admissions, the average AE rates in 2014 (11.6%), 2015 (10.9%) and 2016 (11.4%) were significantly lower than in 2013 (13.1%). The decrease in the AE rates was seen in different age groups, in both genders and for preventable and non-preventable AEs. The decrease comprised only the least severe AEs. The types of AEs that decreased were hospital-acquired infections, urinary bladder distention and compromised vital signs. Patients cared for ‘off-site’ had 84% more preventable AEs than patients cared for in the appropriate units. The cost of increased length of stay associated with preventable AEs corresponded to 13%–14% of the total cost of somatic hospital care in Sweden.

Conclusions

The rate of AEs in Swedish somatic hospitals has decreased from 2013 to 2016. Retrospective record review can be used to monitor patient safety over time, to assess the effects of national patient safety interventions and analyse challenges to patient safety such as the increasing care of patients ‘off-site’. It was found that the economic burden of preventable AEs is high.

Keywords: adverse event, patient harm, patient safety, trigger tool

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The study includes all somatic acute care hospitals in Sweden, except for paediatric units.

This is a longitudinal study over a 4-year period during which an ongoing national patient safety initiative was terminated.

An estimation of the economic cost for prolonged hospital stay due to preventable AEs was undertaken.

The trigger tool and the national database were adaptive to new triggers and trends in healthcare, thus showing the ability to evaluate new patient safety risks.

Inherent weaknesses in a retrospective record review are poor documentation quality and the risk of hindsight bias.

Introduction

Retrospective medical record review (RRR) is an established and validated method to identify adverse events (AEs).1–4 The method gives an overview of the incidence, nature, preventability and consequences of AEs. This information can be used in systematic quality improvement work to reduce the incidence of AEs. RRR is superior to clinical incident reporting systems for detecting AEs.3 A list of criteria (triggers) that indicate a higher probability of AEs may be used to identify details in the record that indicate the presence of AEs. The Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI) in the USA combined topic and location-specific trigger tools into one Global Trigger Tool (GTT),5 which is one of the most commonly used trigger tools. Translated and adapted versions of the GTT are available in, for example, Sweden, Denmark, Norway, Germany, Italy and the UK. Although GTT is considered relevant for measuring AEs at the national level, to the best of our knowledge, only Norway and Sweden have used the methodology for this purpose.6 7

The present study describes the implementation of a trigger tool in Sweden, including the development of a national database that covers reviews from all acute care hospitals save for paediatric and psychiatric care. We also present the national yearly incidence of AEs over a 4-year period (2013–2016) and estimate the cost of preventable AEs.

Methods

Implementation of the Swedish trigger tool

The first national handbook for record review was published in 2008. It was based on the IHI-GTT version 2007, which was translated and adapted to a Swedish context. The Swedish handbook included a six-graded preventability scale used in a national survey on AEs initiated by The National Board of Health and Welfare.8 The trigger tool methodology gradually spreads over the country, and in 2011, hospitals in approximately half of the country’s 21 regions used the method.

In 2012, a national group of experienced reviewers, in collaboration with a reference group of reviewers, patient safety experts and researchers in the trigger tool field, revised the national handbook.9 The work was initiated and financed by the Swedish Association of Local Authorities and Regions (SALAR) as part of a national patient safety initiative. The number of triggers was reduced from 53 to 44 based on the fact that the removed triggers seldom pointed to AEs or were not possible to identify in the review. Others were merged together and renamed. Ten new triggers were added based on local review teams’ findings and research pointing to these common AEs. An example of a new trigger added was urinary bladder distension.10 11 Review teams were educated in all regions in a coordinated effort within a national patient safety initiative, which promoted and financially rewarded record review. This contributed to the rapid use of the method by all somatic acute care hospitals.

National patient safety initiative and database

Launched by the Swedish government and SALAR, a national initiative to increase patient safety took place from 2011 to 2014. The initiative involved financial incentives and included, among other things, safer use of drugs, prevention of resistance to antibiotics, reduction of hospital-acquired infections and measurement of the patient safety culture. As a result of the national initiative, by 2013, all somatic hospitals involved in acute care (n=63) undertook monthly reviews of patient records to determine the rate and nature of AEs. A database was developed by SALAR in 2012, and in this database, the review results from each hospital were entered. These included hospital type, medical specialty, the patient’s gender, age and length of hospital stay and the type, severity and preventability of AEs. The monthly reviews continued after the termination of the national patient safety initiative in December 2014, and by December 2016, the database included almost 65 000 admissions.

The database was expanded in 2015 to include information on risk factors for AEs, such as acute admission, surgical intervention and care provided in another type of unit other than the one specialised for the patient’s medical needs (‘off-site’).

Inclusion criteria and sampling

From the period 2013–2014, the minimum monthly number of randomly selected admissions reviewed was 40 for university hospitals, 30 for the central county council hospitals and 20 for the county hospitals.5 From 2015 and onward, the number of reviewed records was reduced by 50%. Somatic hospital admissions from patients aged 18 years or older with a hospital stay of at least 24 hours were eligible for inclusion. All records from the whole period of hospitalisation were reviewed, which sometimes included more than one type of department.

Review process

Each hospital had its own review team. The review teams consisted of one or two nurses and at least one physician. All team members were senior level, had special training in the record review method and had an interest and knowledge in the field of patient safety. The team members often represented different medical specialties.

A nurse first screened the records for the presence of triggers and possible AEs. In the second review stage, the team assessed the occurrence of AEs. All AEs were categorised according to type, severity and preventability using the national handbook. The physician made the final decisions. There was no assessment of inter-rater reliability.

Categorisation of adverse events

An AE was defined as an unintended physical injury resulting from or contributed to by medical care that required additional monitoring, treatment or hospitalisation or that resulted in death. An AE was categorised into one of 16 different types (see results). A hospital-acquired infection was defined as either an infection associated with previous in-hospital treatment or an infection occurring 48 hours after hospitalisation or within 48 hours after discharge from the hospital. Each AE could only be categorised into one type.

AEs were categorised into one of five severity categories, per the National Coordination Council for Medication Error Reporting and Prevention index: category E: contributed to or resulted in temporary harm and required intervention; category F: contributed to or resulted in temporary harm requiring outpatient care, readmission or prolonged hospital care; category G: contributed to or caused permanent patient harm; category H: event that required lifesaving intervention within 60 min and category I: contributed to the patient’s death.

An AE was categorised as being preventable or not by using a graded scale of four options: (1) The AE was ‘not preventable’; (2) ‘probably not preventable’; (3) ‘probably preventable’ and (4) ‘certainly preventable’. The handbook gives detailed instructions concerning the difficult assessment of preventability (see online supplementary table 1). AEs categorised as 1 and 2 are denoted as non-preventable, and AEs categorised as 3 and 4 are denoted as preventable in the following text and figures.

bmjopen-2017-020833supp001.pdf (84.9KB, pdf)

Statistics

Data are presented as number (per cent), median (range), mean (SD) or mean (95% CI). Comparison of the proportions between two groups was made by χ2 test and between more than two groups by Z-test with Bonferroni adjustment. CIs were calculated using a normal distribution approximation. A p value<0.05 was considered significant. All statistical calculations were made using SPSS V.22 (IBM).

Ethics

The study was conducted in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki (World Medical Association, 2013), and because it was a part of quality improvement initiatives in the hospitals, an approval from an ethical committee was not necessary. The principles published in the National Ethical Guidelines for Research were followed (SFS 2003:460). Names and personal identification numbers were not collected or entered into the database.

Patient and public involvement

Patients were not involved in the study design or the implementation of the national trigger tool. Yearly reports from SALAR of AE rates on an aggregated national level have been publicly available.

Results

Results of GTT 2013–2016

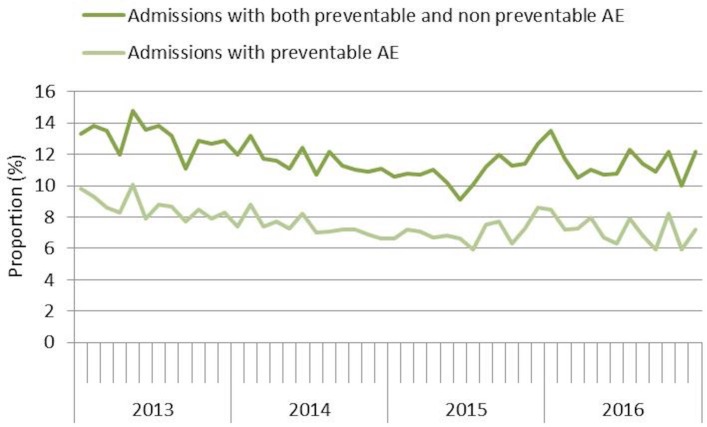

A total of 64 917 admissions were reviewed in 59–63 hospitals during the years 2013–2016. The number of hospitals decreased over the period because two of the minor hospitals stopped reviewing, and two merged with another hospital (table 1). From the beginning of 2013 to the middle of 2015, there was a continuous decline in the average monthly rates of admissions with AEs and preventable AEs (figure 1). During the second half of 2015, the rates of AEs increased slightly and subsequently stabilised.

Table 1.

The number of hospitals and admissions, demographics and the proportion of admissions with adverse events and preventable adverse events

| 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | |

| Number of hospitals | 63 | 63 | 62 | 59 |

| Number of admissions | 19 927 | 18 629 | 13 771 | 12 590 |

| Age (median (range)), years | 71 (18–105) | 71 (18–109) | 71 (18–108) | 72 (18–105) |

| Men, per cent | 46, 8 | 46, 0 | 47, 1 | 48, 0 |

| Admissions with AEs, per cent (95% CI) | 13.1 (12.7 to 13.6)* | 11.6 (11.2 to 12.1)* | 10.9 (10.4 to 11.4)* | 11.4 (10.9 to 12.0)* |

| Admissions with preventable AEs, per cent (95% CI) | 8.7 (8.3 to 9.1)* | 7.4 (7.1 to 7.8)* | 7.0 (6.6 to 7.4)* | 7.2 (6.7 to 7.6)* |

*Significant differences compared with 2013.

AEs, adverse events.

Figure 1.

The proportion of admissions with AEs every month from 2013 to 2016. AEs, adverse events.

The proportion of admissions with preventable AEs decreased significantly between 2013 and the years 2014, 2015 and 2016, respectively. No significant differences were seen between the other years (table 1).

The decrease in the AE rate can largely be attributed to a reduction in the least severe AEs (category E) (table 2). The types of AEs that decreased significantly were hospital-acquired infections, urinary bladder distention, compromised vital signs and ‘other’ (table 3). The latter group included allergic reaction, haemorrhage not related to surgery, venous thrombosis or pulmonary embolus, superficial blood vessel or skin harm, anaesthetic-related AE and any other AE. Among the hospital-acquired infections, there were significant reductions in the rate of admissions with pneumonia, ventilator-associated pneumonia and ‘other infections’.

Table 2.

Proportion (95% CI) of admissions with AEs classified according to severity

| Severity | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 |

| E: contributed to or resulted in temporary harm and required intervention | 7.40 (7.03 to 7.77) |

6.08 (5.73 to 6.42)* |

5.50 (5.12 to 5.89)* |

5.99 (5.57 to 6.40)* |

| F: contributed to or resulted in temporary harm requiring outpatient care, readmission or prolonged hospital care | 6.15 (5.81 to 6.48) |

5.84 (5.50 to 6.18) |

5.74 (5.36 to 6.13) |

5.76 (5.35 to 6.17) |

| G: contributed to or caused permanent patient harm | 0.41 (0.32 to 0.50) |

0.27 (0.20 to 0.35) |

0.29 (0.20 to 0.38) |

0.38 (0.27 to 0.49) |

| H: event that required lifesaving intervention required within 60 min | 0.09 (0.05 to 0.13) |

0.08 (0.04 to 0.12) |

0.12 (0.06 to 0.17) |

0.10 (0.04 to 0.15) |

| I: contributed to the patient’s death | 0.31 (0.23 to 0.38) |

0.23 (0.16 to 0.29) |

0.23 (0.15 to 0.31) |

0.24 (0.15 to 0.32) |

*Significant differences compared with 2013.

AEs, adverse events.

Table 3.

Proportion (95 % CI) of admissions with AEs classified according to type

| Type | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 |

| Hospital-acquired infection | 5.2 (4.9 to 5.5) | 4.6 (4.3 to 4.9)* | 4.5 (4.1 to 4.8)* | 4.3 (4.0 to 4.7)* |

| Infection other | 1.4 (1.2 to 1.6) | 1.0 (0.8 to 1.1)* | 1.1(0.9 to 1.3) | 0.9 (0.8 to 1.1)* |

| Urinary tract infection | 1.4 (1.3 to 1.6) | 1.5 (1.4 to 1.7) | 1.3 (1.1 to 1.5) | 1.3 (1.1 to 1.5) |

| Postoperative wound infection | 1.2 (1.1 to 1.4) | 1.2 (1.0 to 1.3) | 1.1 (0.9 to 1.2) | 1.1 (0.9 to 1.3) |

| Pneumonia | 0.7 (0.6 to 0.8) | 0.5 (0.4 to 0.6)* | 0.5 (0.4 to 0.6)* | 0.5 (0.4 to 0.6)* |

| Sepsis | 0.5 (0.4 to 0.6) | 0.3 (0.3 to 0.4)* | 0.4 (0.3 to 0.6) | 0.5 (0.4 to 0.6) |

| Central venous line infection | 0.2 (0.1 to 0.2) | 0.1 (0.0 to 0.1) | 0.1 (0.0 to 0.1) | 0.1 (0.0 to 0.2) |

| Ventilator associated pneumonia | 0.1 (0.1 to 0.2) | 0.0 (0.0 to 0.1)* | 0.1 (0.0 to 0.1) | 0,1 (0,0 to 0.1)* |

| Clostridium difficile infection | – | 0.3 (0.2 to 0.3) | 0.3 (0.2 to 0.3) | 0.3 (0.2 to 0.3) |

| Other | 2.7 (2.5 to 3.0) | 2.4 (2.2 to 2.7) | 2.0 (1.8 to 2.3)* | 2.2 (2.0 to 2.5)* |

| AEs caused by surgery/invasive procedures | 1.9 (1.7 to 2.1) | 1.8 (1.6 to 2.0) | 1.8 (1.6 to 2.0) | 1.6 (1.4 to 1.8) |

| Urinary bladder distention | 1.7 (1.5 to 1.9) | 1.0 (0.9 to 1.2)* | 1.0 (0.9 to 1.2)* | 1.1 (0.9 to 1.3)* |

| Drug-related AE | 1.4 (1.3 to 1.6) | 1.4 (1.2 to 1.6) | 1.3 (1.1 to 1.5) | 1.5 (1.3 to 1.7) |

| Pressure ulcer (grades 2–4) | 1.1 (1.0 to 1.3) | 1.0 (0.9 to 1.1) | 1.2 (1.0 to 1.4) | 1.3 (1.1 to 1.5) |

| Fall injury | 0.8 (0.7 to 0.9) | 0.9 (0.7 to 1.0) | 0.7 (0.5 to 0.8) | 0.7 (0.6 to 0.9) |

| Compromised vital signs | 0.5 (0.4 to 0.6) | 0.3 (0.2 to 0.3)* | 0.3 (0.2 to 0.4) | 0.2 (0.1 to 0.2)* |

| Postpartum or obstetric AE† | 0.2 (0.2 to 0.3) | 0.2 (0.2 to 0.3) | 0.1 (0.1 to 0.2)* | 0.3 (0.2 to 0.4) |

| Neurological AE | 0.1 (0.1 to 0.2) | 0.0 (0.0 to 0.1) | 0.1 (0.0 to 0.1) | 0.1 (0.1 to 0.2) |

*Significant differences compared with 2013.

†Not corrected for the proportion of women in the studied population.

AEs, adverse events.

When aggregating data for the years 2013–2016, 11.4% of the AEs were categorised as ‘not preventable’, 27.2% as ‘probably not preventable’, 39.4% as ‘probably preventable’ and 22.0% as ‘certainly preventable’. Consequently, 61.4% of the AEs were judged to be preventable (probably and certainly preventable). The types of AEs considered most preventable were pressure ulcer (91%) and urinary bladder distention (88%). The corresponding preventability rates were for hospital-acquired infections (60%), fall injuries (60%), AEs caused by surgery or invasive procedures (56%), ‘other’ (54%), drug-related AE (46%), compromised vital signs (41%), neurological AE (38%) and postpartum or obstetric AE (41%).

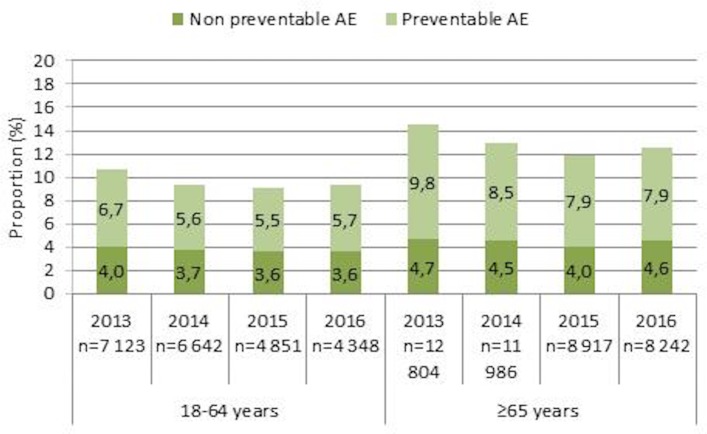

AEs were more common in patients aged 65 years or older than in patients 18–64 years of age (p<0.001). The number of admissions with AEs decreased between 2013 and 2016 in the younger (p=0.02) and older patient groups (p<0.001) (figure 2). The reductions were significant also for the ‘preventable AEs’ (younger p=0.05, older p<0.001).

Figure 2.

Proportion of admissions with preventable and non-preventable AEs in younger and older patients from 2013 to 2016. AEs, adverse events.

When aggregating data for the years 2013–2016, men had a significantly higher rate of admissions with AEs than women (12.5% vs 11.5%, p<0.001). Men had significantly higher rates of hospital-acquired infections and urinary bladder distention. From aggregated data 2013–2016, when stratifying the older age group into three groups (65–74, 75–84 and ≥85 years), the rates of AEs were 12.0%, 13.2% and 14.3%, respectively. The difference was significant between the group 65–74 years and the two older age groups (p=0.02 and p<0.0001, respectively).

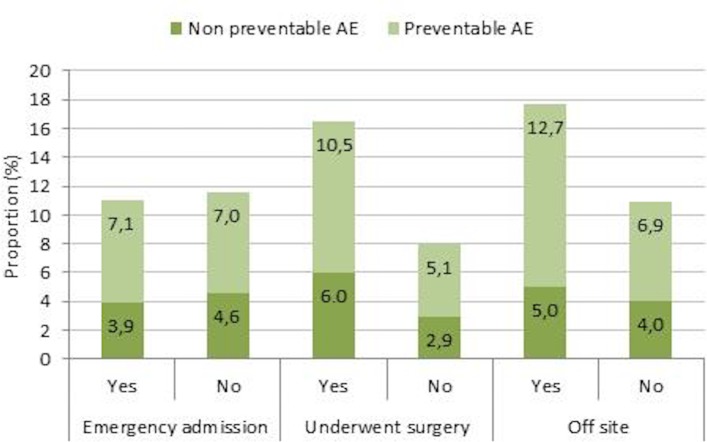

Aggregated data for 2015–2016 showed that the incidence of preventable AEs was almost 100% higher in patients who had undergone surgery or another invasive procedure (n=9584; p<0.001) and approximately 84% higher in patients treated in another unit than the unit specialised to their medical needs (‘off-site’) (n=984; p<0.001). No difference in AE rates was found between acute and planned admissions (p=0.72) (figure 3).

Figure 3.

The proportion of admissions with preventable and non-preventable AEs in patients with acute admissions, patients who underwent surgery and patients treated ‘off-site’ from 2015 to 2016. AEs, adverse events.

Acute admissions were more common in men compared with women (80.5% vs 78.5%, p=0.001) and in patients aged 65 years or older compared with patients under 65 years of age (82.2% vs 73.7%, p<0.001). The proportion of admissions where the patient underwent surgery or another invasive procedure did not differ between the genders. In patients who had surgery, the rate of AEs was higher in acute admissions than in planned admissions (19.1% vs 13.1%, p<0.001).

The proportion of patients cared for ‘off-site’ increased from 3.1% in 2015 to 4.5% in 2016 (p<0.001). Patients aged 65 years or older were more often treated ‘off-site’ than younger patients (4.1% vs 3.1%, p<0.001). No differences related to gender were observed. The most common type of AEs in patients cared for ‘off-site’ were hospital-acquired infections (36.0%) and ‘other’ (19.8%), which includes skin injury, superficial vessel injury and vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism.

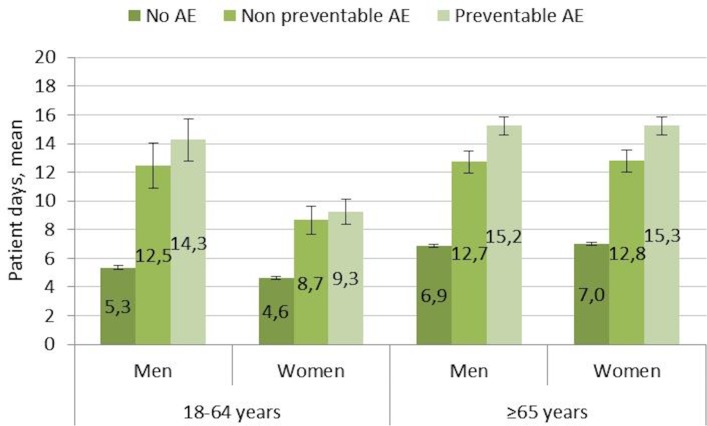

The mean (SD) length of hospital stay (LOS) in aggregated data for 2013–2016 was 7.1 (8.1) days. LOS for the admissions without AEs was 6.2 (6.6) days while admissions with preventable AEs was 14.2 (14.5) days. A significantly longer LOS in patients with AEs was seen in both age groups of both men and women (figure 4). The LOS was significantly longer in older patients (≥65 years) than in younger (18–64 years) both for patients with and without AEs. When stratifying the older age group into three groups (65–74, 75–84 and ≥85 years) no difference was seen between these three groups in LOS among patients with preventable AEs.

Figure 4.

Length of stay (mean, 95% CI) in two age groups of men and women for admissions without AEs, with non-preventable AEs and with preventable AEs from 2013 to 2016. AEs, adverse events.

The mean difference in LOS between hospital stays without AEs and those with preventable AEs was 8 days. The average incidence of preventable AEs (2013–2016) was 8%, and the average number of hospital admissions per year was almost 1.4 million. Accordingly, it can be estimated that preventable AEs affected some 110 000 hospital admissions per year and were associated with 880 000 extra days of hospitalisation. With the mean cost for 1 day of hospitalisation being approximately Kr10 000, the annual cost for preventable AEs can be estimated at €880 million. This corresponds to approximately 13%–14% of the total cost of adult somatic hospital care in Sweden. During 2015 and 2016, approximately 13 000 records were reviewed yearly. The estimated annual total cost for record review was €0.4–0.5 million.

National feedback of the results based on GTT

Regular yearly reports from SALAR described the development of AE rates on an aggregated national level. Also, specific reports for surgical care,12 orthopaedic care,13 obstetrics and gynaecology14 and hospital-acquired infections15 were published. The mapping of AEs is an important basis for improvement work. In 2016, SALAR published an inventory of all patient safety initiatives undertaken by hospitals or departments based on the record review findings. The prominent areas for the 268 different improvement initiatives were pressure ulcers, education of patient safety experts, falls, healthcare-associated infections, urinary bladder distension, surgical harm and compromised vital signs.

Discussion

From our nationwide review of almost 65 000 randomly selected admissions to acute care hospitals, we have shown there was a reduction in the rate of AEs between 2013 and 2014 and 2015 and 2016, respectively. However, a gradual decrease in the rate of admissions with AEs was seen from 2013 until mid-2015; thereafter, the AE rate rose to, and stabilised at, a slightly higher level. The initial gradual decrease in AE rate could reflect the focus on patient safety promoted by the national patient safety initiative. The decrease in the rate of AEs continued 6 months after the termination of the initiative (2014), which may indicate that the effect of the 4-year long initiative persisted for a short period after it was terminated. The subsequent broken trend after the termination of the patient safety initiative may reflect the hospital leadership shifting their focus and a subsequent decrease in the efforts to reduce the rate of AEs. Conceivably, other factors not related to the initiative may have influenced the trends seen in the AE rates. The higher proportion of patients treated ‘off-site’ 2016 compared with 2015 might explain to some extent the increase in the rates of AEs.

The study has some strengths. To our knowledge, the current study is the largest published trigger tool study, including all somatic acute hospitals in Sweden, save for paediatric and psychiatric care. Also, the current study covers a substantial period of time. The revision of the trigger tool made it possible to add triggers found to indicate AEs that were not included in the initial IHI tool, for example, urinary bladder distension and the national database enabled a continuous systematic but also flexible, collection of data because we were able to add administrative data that enabled the detection of safety risks connected to trends in healthcare, for example, increasing ‘off-site’ care. The trigger tool has high specificity, high reliability, is more sensitive than other methods16 17 and large-scale implementations of the GTT including modifications have been successful in other studies.6 18 19

In retrospective record review studies, a potential weakness is poor documentation quality, which means only documented AEs can be identified. The true number of AEs and even premature death is thus probably higher than found only by RRR.20 Postdischarge patient interviews have shown that even serious AEs are not documented in the record and that AEs that not occur in close proximity to hospital stay might go unnoticed.21 An example is a forgotten vaccination against pneumococcal infection in connection with splenectomy that may give a serious infection decades later. Direct observation of care is another way of detecting AEs not captured by a record review.22 Another weakness is the risk of hindsight bias when assessing the preventability of AEs. Two-thirds of the AEs were classified as ‘probably preventable’ or ‘probably not preventable’, which illustrates the difficulty in determining preventability with certainty. A further limitation is that we did not assess inter-rater reliability. The reason is that as the record reviews were part of a national patient safety initiative with the primary focus on changes in AE rates of individual hospitals and not for comparisons in between hospitals. The number of reviewed admissions from university hospitals, central county council hospitals and small hospitals does not fully reflect the true proportion of admissions to these hospital categories. Because the rates of AEs differ between hospital types, this must be taken into account when estimating the true national average rate of AEs. When doing so, the national rates of AEs presented in this paper increase by approximately 10%.

We have demonstrated an increased rate of AEs in patients cared for in another type of unit other than the one specialised for their medical needs. The main reason why patients are cared for ‘off-site’ is a shortage of available beds due to lack of nurses. Actions need to be taken to reduce the number of ‘off-site’ patients.

As shown earlier,23 a hospital-acquired infection is the most common type of AE, and its incidence fell during the study period. Evidence-based programmes to prevent central venous catheter-associated infections, postoperative wound infections and urinary tract infections were promoted nationally during the study period. This was carried out by conducting a continuous follow-up on compliance to basic hygiene rules and dress code on a department level. Conceivably, the promotion of measures to reduce the incidence of hospital-acquired infections during the patient safety initiative was successful and resulted in a reduction of infection rates.

Urinary bladder distention was most often regarded as preventable, and the rates decreased over time. This could in part be because of the use of a stricter definition after 2013, but this problem was extensively addressed by physicians as well as nursing organisations. The decrease in the rates of compromised vital signs could reflect an increased use of vital sign checks, such as the modified early warning score24 and rapid response teams.25

The higher incidence of AEs found among men can partly be attributed to their higher rates of hospital-acquired infections and urinary bladder distension. The reason behind the former remains to be explained. Another explanation is that the present study included gynaecology and obstetrics, where AE rates are lower than in other medical disciplines.26

The suffering associated with patient harm for the patients, relatives and involved personnel is high but cannot easily be quantified. There is also an economic burden associated with patient harm, both on healthcare and society. The golden standard to estimate the financial cost of AEs for healthcare is considered to be retrospective record review.27 Our estimate, based solely on the costs of prolonged LOS, is in line with a recent report that suggested that 15% of hospital expenditures in Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries relate to AEs.28 These entail additional treatment and diagnostic procedures, (re)admission to hospital and a prolonged hospital stay. In line with our finding, the OECD report estimated that 6–8 additional days are spent in the hospital for patients having an AE.26 With a longer LOS, it is probable that patients are more exposed to AEs. Regrettably, we did not collect data on day of occurrence of AEs. However, our group has previously shown that AEs most often occur early during the hospital stay or cause the hospitalisation.29 The OECD report28 emphasises that the costs for preventive actions are substantially lower than the costs of AEs.

To our knowledge, Norway and Sweden are the only countries so far that has have evaluated the effect of a national patient safety initiative using monthly assessments of AE rates based on GTT. Accordingly, some 40 000 hospital admissions were reviewed during the Norwegian patient safety campaign, and AE rates decreased from 16.1% (2011) to 13.0% (2013).6 The rates and types of AEs in Norway and Sweden in 2013 have been shown to be similar.7

In conclusion, AE rates in Swedish somatic acute care hospitals decreased between 2013 and 2014, 2015 and 2016, respectively. Retrospective record review is a useful method to monitor patient safety over time and to assess the effects of national patient safety interventions. Off-site care of patients is becoming more common. This increases the incidence of AEs and is a challenge to patient safety. The economic burden of preventable AEs is high.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: All authors designed and conducted the study. MB-R statistically analysed the data. HR, UN and CÅ undertook the initial interpretation of the data, which was followed by discussions with all the authors. LN and HR drafted the initial version of the manuscript, which was followed by a critical revision process of the intellectual content involving all the authors. All the authors agreed to the final version of the manuscript before submission. All authors agreed to be accountable for the accuracy of any part of the work.

Funding: This work was supported by the Swedish Association of Local Authorities and Regions by creating and hosting a national database for the reporting of data from the record reviews.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Not required.

Ethics approval: We used retrospective record review to investigate adverse events as part of a structured quality improvement. The principles published in the National Ethical Guidelines for Research were followed (SFS 2003:460). Names and personal identification numbers were not collected or entered into the database.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Naessens JM, Campbell CR, Huddleston JM, et al. A comparison of hospital adverse events identified by three widely used detection methods. Int J Qual Health Care 2009;21:301–7. 10.1093/intqhc/mzp027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Christiaans-Dingelhoff I, Smits M, Zwaan L, et al. To what extent are adverse events found in patient records reported by patients and healthcare professionals via complaints, claims and incident reports? BMC Health Serv Res 2011;11:49 10.1186/1472-6963-11-49 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Classen DC, Resar R, Griffin F, et al. ’Global trigger tool' shows that adverse events in hospitals may be ten times greater than previously measured. Health Aff 2011;30:581–9. 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Unbeck M, Muren O, Lillkrona U. Identification of adverse events at an orthopedics department in Sweden. Acta Orthop 2008;79:396–403. 10.1080/17453670710015319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Griffin FA, Resar RK. IHI Global trigger tool for measuring adverse events. IHI innovation series white paper. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Institute for Healthcare Improvement, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Deilkås ET, Bukholm G, Lindstrøm JC, et al. Monitoring adverse events in Norwegian hospitals from 2010 to 2013. BMJ Open 2015;5:e008576 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-008576 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Deilkås ET, Risberg MB, Haugen M, et al. Exploring similarities and differences in hospital adverse event rates between Norway and Sweden using Global Trigger Tool. BMJ Open 2017;7:e012492 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-012492 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Soop M, Fryksmark U, Köster M, et al. The incidence of adverse events in Swedish hospitals: a retrospective medical record review study. Int J Qual Health Care 2009;21:285–91. 10.1093/intqhc/mzp025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Markörbaserad Journalgranskning för att identifiera och mäta skador i vården [in Swedish]. Sveriges kommuner och Landsting: ETC kommunikation, 2012. ISBN: 978-917-164-847. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Unbeck M, Dalen N, Muren O, et al. Healthcare processes must be improved to reduce the occurrence of orthopaedic adverse events. Scand J Caring Sci 2010;24:671–7. 10.1111/j.1471-6712.2009.00760.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Joelsson-Alm E, Nyman CR, Lindholm C, et al. Perioperative bladder distension: a prospective study. Scand J Urol Nephrol 2009;43:58–62. 10.1080/00365590802299122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nilsson L, Risberg MB, Montgomery A, et al. Preventable adverse events in surgical care in Sweden: a nationwide review of patient notes. Medicine 2016;95:e3047 10.1097/MD.0000000000003047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rutberg H, Borgstedt-Risberg M, Gustafson P, et al. Adverse events in orthopedic care identified via the global trigger tool in Sweden implications on preventable prolonged hospitalizations. Patient Saf Surg 2016;10:23 10.1186/s13037-016-0112-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Skador i vården. Skadefrekvens och skadepanorama för obstetric och gynekologi (In Swedish). http://lof.se/wp-content/uploads/Skador-i-v%C3%A5rden-skadefrekvens-och-skadepanorama-f%C3%B6r-obstetrik-och-gynekologi.pdf (accessed Sep 2017).

- 15.Vårdrelaterade infektioner. Kunskap, konsekvenser, kostnader (In Swedish). ISBN: 978-91-7585-475-5 http://webbutik.skl.se/bilder/artiklar/pdf/7585-475-5.pdf?issuusl=ignore (accessed Sep 2017).

- 16.Sharek PJ, Parry G, Goldmann D, et al. Performance characteristics of a methodology to quantify adverse events over time in hospitalized patients. Health Serv Res 2011;46:654–78. 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2010.01156.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Naessens JM, O’Byrne TJ, Johnson MG, et al. Measuring hospital adverse events: assessing inter-rater reliability and trigger performance of the Global Trigger Tool. Int J Qual Health Care 2010;22:266–74. 10.1093/intqhc/mzq026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Good VS, Saldaña M, Gilder R, et al. Large-scale deployment of the Global Trigger Tool across a large hospital system: refinements for the characterisation of adverse events to support patient safety learning opportunities. BMJ Qual Saf 2011;20:25–30. 10.1136/bmjqs.2008.029181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Garrett PR, Sammer C, Nelson A, et al. Developing and implementing a standardized process for global trigger tool application across a large health system. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf 2013;39:292–7. 10.1016/S1553-7250(13)39041-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.James JT. A new, evidence-based estimate of patient harms associated with hospital care. J Patient Saf 2013. 9:122–8. 10.1097/PTS.0b013e3182948a69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Weissman JS, Schneider EC, Weingart SN, et al. Comparing patient-reported hospital adverse events with medical record review: do patients know something that hospitals do not? Ann Intern Med 2008;149:100–8. 10.7326/0003-4819-149-2-200807150-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Flynn EA, Barker KN, Pepper GA, et al. Comparison of methods for detecting medication errors in 36 hospitals and skilled-nursing facilities. Am J Health Syst Pharm 2002;59:436–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hibbert PD, Molloy CJ, Hooper TD, et al. The application of the global trigger tool: a systematic review. Int J Qual Health Care 2016;28:640–9. 10.1093/intqhc/mzw115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Smith ME, Chiovaro JC, O’Neil M, et al. Early warning system scores for clinical deterioration in hospitalized patients: a systematic review. Ann Am Thorac Soc 2014;11:1454–65. 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201403-102OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Solomon RS, Corwin GS, Barclay DC, et al. Effectiveness of rapid response teams on rates of in-hospital cardiopulmonary arrest and mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Hosp Med 2016;11:438–45. 10.1002/jhm.2554 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Leape LL, Brennan TA, Laird N, et al. The nature of adverse events in hospitalized patients. Results of the harvard medical practice study II. N Engl J Med 1991;324:377–84. 10.1056/NEJM199102073240605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jackson T. One dollar in seven: scoping the economics of patient safety: The Canadian Patient Safety Institute, 2009. http://www.patientsafetyinstitute.ca/en/toolsResources/Research/commissionedResearch/EconomicsofPatientSafety/Documents/Economics%20of%20Patient%20Safety%20Literature%20Review.pdf (accessed Sep 2017). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Slawomirski L, Auraaen A, Klazinga N. The economics of patient safety: strengthening a value-based approach to reducing patient harm at national level: OECD, Directorate for Employment, Labour and Social Affairs, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rutberg H, Borgstedt Risberg M, Sjödahl R, et al. Characterisations of adverse events detected in a university hospital: a 4-year study using the global trigger tool method. BMJ Open 2014;4:e004879 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-004879 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2017-020833supp001.pdf (84.9KB, pdf)