Abstract

Objective

Hospital readmission in patients admitted for community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) is frequent in the elderly and patients with multiple comorbidities, resulting in a clinical and economic burden. The aim of this study was to determine factors associated with 30-day readmission in patients with CAP.

Design

A cross-sectional study.

Setting

The study was conducted in patients admitted to 20 hospitals in seven Spanish regions during two influenza seasons (2013–2014 and 2014–2015).

Participants

We included patients aged ≥65 years admitted through the emergency department with a diagnosis compatible with CAP. Patients who died during the initial hospitalisation and those hospitalised more than 30 days were excluded. Finally, 1756 CAP cases were included and of these, 200 (11.39%) were readmitted.

Main outcome measures

30-day readmission.

Results

Factors associated with 30-day readmission were living with a person aged <15 years (adjusted OR (aOR) 2.10, 95% CI 1.01 to 4.41), >3 hospital visits during the 90 previous days (aOR 1.53, 95% CI 1.01 to 2.34), chronic respiratory failure (aOR 1.74, 95% CI 1.24 to 2.45), heart failure (aOR 1.69, 95% CI 1.21 to 2.35), chronic liver disease (aOR 2.27, 95% CI 1.20 to 4.31) and discharge to home with home healthcare (aOR 5.61, 95% CI 1.70 to 18.50). No associations were found with pneumococcal or seasonal influenza vaccination in any of the three previous seasons.

Conclusions

This study shows that 11.39% of patients aged ≥65 years initially hospitalised for CAP were readmitted within 30 days after discharge. Rehospitalisation was associated with preventable and non-preventable factors.

Keywords: community acquired pneumonia, readmission, elderly, infectious diseases

Strengths and limitations of this study.

All the information on readmission was obtained from medical records.

The study is part of a multicentre study carried out in seven autonomous communities representing 70% of the Spanish population.

It was not possible to collect detailed information on the readmission episode.

Introduction

Community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) is a frequent, potentially serious disease in people aged ≥65 years and one of the leading causes of hospitalisation and mortality worldwide in this age group,1–4 in whom recovery from an episode of CAP is predictive of increased mortality in subsequent years.5

The incidence of CAP differs between European countries due to variations in age distribution, the introduction of vaccination programmes and the clinical guidelines used. However, the incidence of cases and hospitalisations increases with age in all countries.6 7 In Spain, CAP is not a reportable disease and therefore the incidence in the population is unknown, although 2013 data also show an increase in hospitalisation (394.04 per 100,000 in the 65–74 years age group and 2584.95 per 100,000 in the >85 years age group).8

In people aged ≥65 years, full recovery after hospitalisation due to CAP is usually slow and the probability of readmission during a period of time after discharge is greater.9 Thirty-day readmission postdischarge is usually used as an indicator of vulnerability.2 10–12

Readmission in patients initially hospitalised due to CAP is relatively frequent (especially in the elderly and patients with multiple comorbidities), and is often associated with a worsening of a baseline disease or the appearance of a new pathology,13 and this results in a significant clinical and economic burden for health systems.2 14 Studies have explored the factors associated with readmission following hospitalisation due to CAP, and have identified factors that improve the prognosis at discharge and are considered preventable, such as influenza and pneumococcal vaccination, the use of hospital care protocols, discharge planning and postdischarge follow-up. Adequate discharge planning, including patient stability and destination, has been associated with reduced readmission.15–17 However, the effect of seasonal influenza and pneumococcal vaccination and the adequacy of hospital care (use of clinical guidelines and antibiotic plans) may be more controversial.18–21 The initial severity of CAP, worsening of comorbidities and some individual patient characteristics have been described as non-preventable factors,15 21–25 and factors such as age, sex, socioeconomic status, education and some comorbidities have been independently associated with a greater likelihood of readmission.25 26

The objective of this study was to determine the risk factors associated with 30-day readmission in people aged ≥65 years initially hospitalised due to CAP.

Materials and methods

Study design

This cross-sectional study was carried out as part of a multicentre study in 20 hospitals from seven Spanish regions (Andalusia, the Basque Country, Castile and Leon, Catalonia, Madrid, Navarre and Valencian Community). Patients aged ≥65 years hospitalised due to CAP in the participating hospitals during the 2013–2014 and 2014–2015 influenza seasons were recruited.

Study population

The Spanish health system assigns each citizen a primary healthcare centre and a referral hospital to be attended. The assignation of the population to each hospital is made according to geography. Consequently, if there is a readmission, it would be in the same hospital. However, in an emergency, the patient may be treated in any hospital.

Patients included were aged ≥65 years admitted through the emergency department to any of the participating hospitals for ≥24 hours with a chest X-ray showing pulmonary infiltrate compatible with pneumonia and ≥1 of the following symptoms or signs of acute lower respiratory tract infection: cough, pleural chest pain, dyspnoea, fever >38°C, hypothermia <35°C and abnormal auscultator respiratory sounds unexplained by other causes.

Patients who died during the initial hospitalisation and patients hospitalised for more than 30 days were not included. Institutionalised patients, patients with nosocomial pneumonia (onset ≥48 hours after hospital admission), patients whose main residence was not in any of the seven participating regions and those who did not provide signed informed consent were excluded.

Outcomes

The dependent variable was 30-day readmission, defined as ‘hospitalisation for any reason within 30 days of discharge’. Information on readmission was collected by re-review of index hospital medical records up to 30 days after initial discharge.

All participating hospitals had a specifically trained team of health professionals who used a structured questionnaire to obtain sociodemographic information and lifestyle factors by patient interview and the review of patient’s medical record to collect immunisation history, risk medical conditions and the CAP hospital care process.

Information collected included sociodemographic variables: age, sex, marital status, educational level, cohabitation; lifestyle factors: smoking status (current smoker, ex-smoker, non-smoker) and high alcohol consumption (>40 g/day in men, >20 g/day in women). The Barthel Index27 was used to assess the functional capacity at hospital admission (ranging from 0 — complete dependence to 100 — complete independence). Patients were considered vaccinated against pneumococcal disease if they had received a dose of pneumococcal vaccine in the last 5 years and against seasonal influenza if they had received a dose of the influenza vaccination at least 14 days before symptom onset. Comorbidities considered at high or moderate risk (chronic respiratory failure, history of pneumonia during the last 2 years, solid or haematological neoplasm, diabetes mellitus, renal failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), heart failure, disabling neurological disease, chronic liver disease and haemoglobinopathy or anaemia) were collected from the patient’s medical record through chart review and were assessed using the Charlson Comorbidity Index,28 which assigns a weight to each comorbid condition (0, no comorbidity; 1, low comorbidity and 2, high comorbidity). Number of primary care nurse visits, number of hospital visits in the last 90 days. Severity of illness quantified in five risk classes using the Pneumonia Severity Index (PSI) at admission,29 length of stay (LOS) <8 and ≥8 days,8 intensive care unit (ICU) admission, mechanical ventilation, adequacy of antibiotic treatment plan according to clinical guidelines (yes/no) and discharge disposition (home without services, home with home healthcare or social health centre) 6 were also colected

Statistical analysis

The Barthel Index, a continuous variable, was dichotomised into 0–89 (moderate-to-high degree of dependency) and ≥90 (little or no dependency).

A bivariate analysis was conducted to compare 30-day readmission and no readmission according to sociodemographic variables, lifestyle factors, the Barthel Index, immunisation history, risk medical conditions, prior medical utilisation and hospital care process. Independent variables were checked for collinearity using the variance inflation factor.30

As Spanish regions have varying degrees of autonomy in organising health services, persons living in the same region tend to have similar access to healthcare. Therefore, to estimate the crude OR and adjusted OR (aOR), we used multilevel regression models that considered the outcome variable in people from the same region to obtain accurate statistical estimates of predictors of 30-day readmission.30 Covariates were introduced into the model using a backward stepwise procedure, with a cut-off point of p<0.2.

The analysis was performed using the SPSS V.24 statistical package and R V.3.3.0 statistical software.

Results

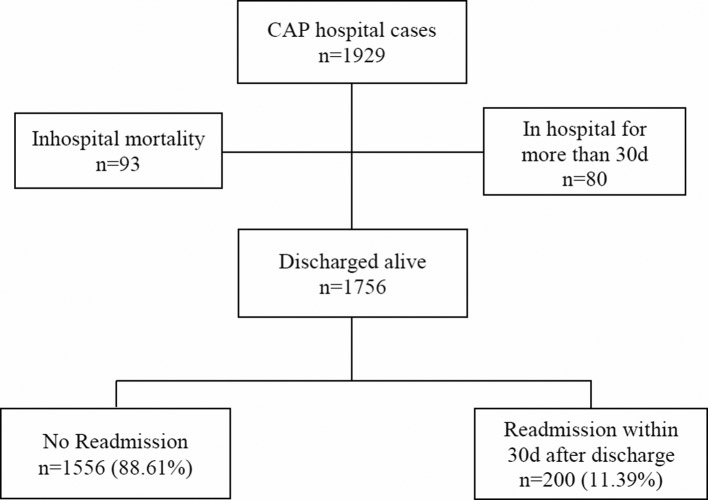

Overall, 1929 inpatients met all study eligibility criteria for CAP: 93 patients died during the initial hospitalisation and 80 were hospitalised for >30 days. Therefore, 1756 CAP cases were discharged within 30 days after the initial hospitalisation: of these, 200 (11.39%) were readmitted within 30 days after hospital discharge (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow chart of hospital readmissions. CAP, community-acquired pneumonia.

The reasons for 30-day readmission were unrelated to pneumonia in 49.5% (99 cases), pneumonia-related in 44.5% (89 cases) and unknown diagnosis in 6% (12 cases).

The descriptive analysis and unadjusted associations of factors related to 30-day readmission are shown in table 1. No differences were observed according to lifestyle factors and immunisation history.

Table 1.

Distribution of 30-day readmission cases according to patient characteristics

| Readmission n=200 | No readmission n=1556 | Crude OR (95%CI) | P values | |

| Sociodemographic | ||||

| Age median (range) | 80 (65–101) | 78 (64–100) | 1.02 (0.99–1.04) | 0.07 |

| Age group | ||||

| 65–74 years | 56 (28.0%) | 501 (32.2%) | 1 | |

| 75–84 years | 98 (49.0%) | 729 (46.9%) | 1.20 (0.85–1.70) | 0.31 |

| >84 years | 46 (23.0%) | 326 (20.5%) | 1.26 (0.83–1.91) | 0.27 |

| Sex | ||||

| Female | 64 (32.0%) | 622 (40.0%) | 1 | |

| Male | 136 (68.0%) | 934 (60.0%) | 1.44 (1.05–1.97) | 0.02 |

| Educational level | ||||

| No/primary education | 153 (78.1%) | 1118 (72.4%) | 1 | |

| Secondary or higher | 43 (21.9%) | 427 (27.6%) | 0.75 (0.51–1.10) | 0.14 |

| Marital status | ||||

| Married/cohabiting | 116 (58.0%) | 912 (58.6%) | 1 | |

| Single | 21 (10.5%) | 107 (6.9%) | 1.56 (0.94–2.59) | 0.09 |

| Widowed/divorced | 63 (31.5%) | 536 (34.4%) | 0.93 (0.67–1.29) | 0.66 |

| Cohabitation | ||||

| Lives alone | 31 (15.5%) | 289 (18.6%) | 1 | |

| Lives with cohabitant aged >15 years | 155 (77.5%) | 1203 (77.4%) | 1.20 (0.80–1.80) | 0.39 |

| Lives with cohabitant aged <15 years | 14 (7.0%) | 63 (4.1%) | 2.03 (1.02–4.04) | 0.04 |

| Lifestyle factors | ||||

| Smoking status | ||||

| Non-smoker | 79 (39.5%) | 693 (44.5%) | 1 | |

| Smoker | 16 (8.0%) | 138 (8.9%) | 1.04 (0.59–1.83) | 0.90 |

| Ex-smoker | 105 (52.5%) | 725 (46.6%) | 1.28 (0.94–1.75) | 0.11 |

| High alcohol consumption | ||||

| No | 197 (98.5%) | 1524 (97.9%) | 1 | |

| Yes | 3 (1.5%) | 32 (2.1%) | 1.38 (0.42–4.54) | 0.60 |

| Prior utilisation of resources | ||||

| No of nurse visits in last 90 days | ||||

| 0–2 | 147 (73.5%) | 1182 (76.4%) | 1 | |

| ≥3 | 53 (26.5%) | 365 (23.6%) | 1.17 (0.82–1.65) | 0.39 |

| No of hospital visits in last 90 days | ||||

| 0–2 | 164 (82.8%) | 1355 (87.6%) | 1 | |

| ≥3 | 34 (17.2%) | 192 (12.4%) | 1.53 (1.02–2.31) | 0.04 |

| Barthel Index | ||||

| Little or no dependency >90 | 108 (54.0%) | 990 (63.6%) | 1 | |

| Moderate-to-high dependency ≤90 | 92 (46.0%) | 566 (36.4%) | 1.47 (1.08–2.01) | 0.01 |

| Immunisations | ||||

| Influenza vaccination in any of the three previous seasons | ||||

| No | 54 (27.0%) | 464 (29.8%) | 1 | |

| Yes | 146 (73.0%) | 1092 (70.2%) | 1.16 (0.83–1.61) | 0.39 |

| Pneumococcal vaccination in five previous years | ||||

| No | 161 (80.5%) | 1281 (82.3%) | 1 | |

| Yes | 39 (19.5%) | 275 (17.7%) | 1.11 (0.76–1.62) | 0.58 |

| Risk medical conditions | ||||

| Chronic respiratory failure | ||||

| No | 136 (68.0%) | 1269 (81.6%) | 1 | |

| Yes | 64 (32.0%) | 287 (18.4%) | 2.08 (1.50–2.88) | <0.001 |

| Pneumonia during the last 2 years | ||||

| No | 146 (73.0%) | 1267 (81.4%) | 1 | |

| Yes | 54 (27.0%) | 289 (18.6%) | 1.65 (1.18–2.32) | 0.004 |

| Any malignancy | ||||

| No | 161 (80.5%) | 1271 (81.7%) | 1 | |

| Yes | 39 (19.5%) | 285 (18.3%) | 1.08 (0.74–1.58) | 0.67 |

| Diabetes | ||||

| No | 139 (69.5%) | 1023 (65.7%) | 1 | |

| Yes | 61 (30.5%) | 533 (34.3%) | 0.83 (0.60–1.14) | 0.26 |

| Renal failure | ||||

| No | 151 (75.5%) | 1263 (81.2%) | 1 | |

| Yes | 49 (24.5%) | 293 (18.8%) | 1.38 (0.97–1.96) | 0.07 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | ||||

| No | 128 (64.0%) | 1074 (69.0%) | 1 | |

| Yes | 72 (36.0%) | 482 (31.0%) | 1.25 (0.92–1.70) | 0.16 |

| Heart failure | ||||

| No | 128 (64.0%) | 1168 (75.1%) | 1 | |

| Yes | 72 (36.0%) | 388 (24.9%) | 1.69 (1.24–2.31) | 0.001 |

| Chronic liver disease | ||||

| No | 186 (93.0%) | 1504 (96.7%) | 1 | |

| Yes | 14 (7.0%) | 52 (3.3%) | 2.13 (1.15–3.94) | 0.01 |

| Haemoglobinopathy or anaemia | ||||

| No | 160 (80.0%) | 1324 (85.1%) | 1 | |

| Yes | 40 (20.0%) | 232 (14.9%) | 1.40 (0.96–2.04) | 0.08 |

| Disabling neurological disease | ||||

| No | 179 (89.5%) | 1416 (91.0%) | 1 | |

| Yes | 21 (10.5%) | 140 (9.0%) | 1.17 (0.72–1.90) | 0.52 |

| Charlson Index | ||||

| No comorbidity (0) | 18 (9.0%) | 233 (15.0%) | 1 | |

| Low comorbidity (1) | 54 (27.0%) | 378 (24.3%) | 1.83 (1.05–3.20) | 0.03 |

| High comorbidity (≥2) | 128 (64.0%) | 945 (60.7%) | 1.71 (1.02–2.86) | 0.04 |

| Hospital care process | ||||

| Intensive care unit | ||||

| No | 188 (94.5%) | 1499 (96.9%) | 1 | |

| Yes | 11 (5.5%) | 48 (3.1%) | 1.93 (0.97–3.81) | 0.06 |

| Mechanical ventilation | ||||

| No | 157 (78.5%) | 1317 (84.9%) | 1 | |

| Yes | 43 (21.5%) | 235 (15.1%) | 1.50 (1.03–2.18) | 0.03 |

| Pneumonia Severity Index | ||||

| I–III | 69 (34.7%) | 645 (41.7%) | 1 | |

| IV–V | 130 (65.3%) | 902 (58.3%) | 1.40 (1.02–1.92) | 0.04 |

| Length of hospital stay | ||||

| <8 days | 80 (40.0%) | 766 (49.2%) | 1 | |

| ≥8 days | 120 (60.0%) | 790 (50.8%) | 1.45 (1.05–2.02) | 0.02 |

| Antibiotic treatment | ||||

| No | 97 (50.3%) | 700 (46.6%) | 1 | |

| Yes | 96 (49.7%) | 802 (53.4%) | 1.07 (0.76–1.50) | 0.70 |

| Discharge disposition | ||||

| Home without services | 185 (92.5%) | 1477 (94.9%) | 1 | |

| Home with home healthcare | 9 (4.5%) | 19 (1.2%) | 5.05 (1.58–16.15) | 0.01 |

| Social health centre | 6 (3.0%) | 60 (3.9%) | 1.23 (0.41–2.92) | 0.63 |

Factors independently associated with 30-day readmission in the multilevel analysis (table 2) were living with a person aged <15 years (aOR 2.10, 95% CI 1.01 to 4.41; p=0.04), more than three hospital visits during the 90 previous days (aOR 1.53, 95% CI 1.01 to 2.34; p=0.04) chronic respiratory failure (aOR 1.74, 95% CI 1.24 to 2.45; p=0.001), heart failure (aOR 1.69, 95% CI 1.21 to 2.35; p=0.002), chronic liver disease (aOR 2.27, 95% CI 1.21 to 4.31; p=0.01) and discharge to home with home healthcare (aOR 5.61, 95% CI 1.70 to 18.50; p=0.005).

Table 2.

Multilevel regression analysis of factors associated with 30-day readmission

| Adjusted OR (95%CI) | P values | |

| Age | 1.02 (0.99–1.04) | 0.13 |

| Sex—male | 1.39 (0.99–3.12) | 0.06 |

| Cohabitation | ||

| Lives alone | 1 | |

| Lives with cohabitant aged >15 years | 1.17 (0.71–1.95) | 0.54 |

| Lives with cohabitant aged <15 years | 2.10 (1.01–4.41) | 0.04 |

| Marital status | ||

| Married/cohabiting | 1 | |

| Single | 1.73 (0.96–3.11) | 0.07 |

| Widowed/divorced | 0.94 (0.61–1.44) | 0.77 |

| No of hospital visits ≥3 | 1.53 (1.01–2.34) | 0.04 |

| Barthel Index | ||

| Moderate-to-high dependency ≤90 | 1.39 (0.99–1.95) | 0.05 |

| Pneumonia during the last 2 years | 1.31 (0.91–1.88) | 0.14 |

| Chronic respiratory failure | 1.74 (1.24–2.45) | 0.001 |

| Diabetes | 0.74 (0.53–1.04) | 0.08 |

| Heart failure | 1.69 (1.21–2.35) | 0.002 |

| Chronic liver disease | 2.27 (1.20–4.31) | 0.01 |

| Mechanical ventilation | 1.33 (0.90–1.97) | 0.15 |

| Discharge disposition | ||

| Home without services | 1 | |

| Home with home healthcare | 5.61 (1.70–18.50) | 0.005 |

| Social health centre | 1.27 (0.53–3.05) | 0.59 |

A moderate-to-high degree of dependency was tentatively associated with readmission (aOR 1.39, 95% CI 0.99 to 1.95; p=0.05).

No associations were observed with age, sex, pneumococcal vaccination or seasonal influenza vaccination in any of the three previous seasons, the PSI or any variable related to the hospital care process.

Discussion

The overall 30-day readmission rate in our study was 11.39%. Although all participating hospitals were referral centres, readmission rates ranged between regions from 2.5% to 14%. This might be due to the differences in the hospital healthcare burden of participating hospitals and in the protocols used.

In the Pneumonia Patient Outcomes Research Team cohort study, carried out in the USA and Canada, the readmission rate in adults was 10.1%.31 Readmission rates at 30 days in people aged ≥65 years admitted for CAP vary between 8% and 27%, depending on the population and country studied.11 19 21 25 32 In Spain, national data show 30-day readmissions increased from 11.5% in 2004 to 13.5% in 2013 in adults admitted for CAP.8

Our results show that non-preventable factors, specifically patient characteristics (living with a person aged <15 years, more than three hospital visits during the 90 previous days and some comorbidities) and one preventable factor (discharge disposition) were significantly associated with 30-day readmission. Factors such as cohabitation and the discharge dispostion have been little studied and their identification provides a new perspective on the risk factors involved in 30-day readmission of these patients.

Calvillo-King et al in a thorough review of studies on readmission, underlined the importance of considering social factors (sociodemographic, socioeconomic and the social environment) as elements that could influence readmission after an episode of CAP.22 Our study evaluated sociodemographic and socioeconomic factors and the social environment. Although the influence of sex varies between studies and may be closely related to other factors such as age, risk habits and some comorbidities, the association with male sex disappeared in the final model, in contrast to the results found by Neupane et al, and Bohannon and Maljanian.19 33

Patients living with children aged <15 years had a twofold higher probability of readmission than those living alone or with a partner. Although it is known that school children may be a source of infection of the elderly in some infectious diseases, we found no studies that investigated the type of cohabitation in this context, possibly because one factor usually associated with readmission in people aged ≥65 years is living in geriatric residences.11 In Spain, the recommendation of vaccination of persons in contact with high-risk persons, including persons aged ≥65 years with risk factors has been maintained.34 We also found no association with factors identified by other authors, such as the educational level or the history of smoking or alcohol use.25 35

In the studies by Neupane et al in two Canadian cities and Adamuz et al in a tertiary hospital in Barcelona, seasonal influenza and pneumococcal vaccination were included in the adjusted analysis of readmission due to CAP, but no association was found.19 23 We investigated seasonal influenza and pneumococcal vaccination in the previous 5 years but found no association in the crude or adjusted models.

In our study, 49.5% of 30-day readmissions were due to causes unrelated to CAP and 91% of readmitted patients presented comorbidities. Patients with chronic liver disease, heart failure and respiratory failure had higher 30-day readmission rates, findings consistent with other studies showing that some cardiovascular and respiratory diseases play an important role in the risk of readmission in patients with CAP,12 23–25 36 and that the reason for readmission generally differs from the initial diagnosis of CAP due, in most cases, to destabilisation of comorbidities10 23–26 37 38. Fine et al, in a cohort study, found that pneumonia often occurs in patients with underlying comorbidities and often results in a worsening of such underlying conditions.31

We found an association with prior hospital utilisation in the 90 days before admission for CAP, but no association with general practitioner and primary care nurse visits. Healthcare in Spain is free, which encourages patients to make multiple visits to primary care centres and/or hospitals, ensuring patient care and follow-up. Adamuz et al and Tang et al found an association between readmission and hospitalisation in the 90 days before admission for CAP.11 23

One preventable factor that influences CAP episodes in people aged ≥65 years is the quality of care received during hospitalisation, while discharge planning and follow-up until recovery influence patient recovery and, therefore, readmission.16 21 23 24 We found, as did Dong et al,16 an association with discharge to home with home healthcare. A possible explanation might be an inadequate evaluation of the patient’s stability at discharge. Various authors have suggested the importance of the discharge dispostion in patients admitted due to other causes such as COPD or some specific interventions.39–41 However, with respect to patients with CAP, only Dong et al and the present study have found an association between the discharge dispostion and readmission. Other variables related to the quality of care were studied to assess these aspects but no association with readmission was found.

Strengths and limitations

The main strength of the study is that all clinical information was obtained from patient medical records and, therefore, was unlikely to be biased. Another strength is the cross-sectional design, as it is part of a multicentre study carried out in seven regions representing 70% of the Spanish population.

A limitation is that it was not possible to collect patient characteristics at discharge, and therefore we cannot say whether there was instability at discharge that may have caused the readmission. Therefore, the variable ‘discharge disposition’ was considered as a proxy to define instability.

Conclusions

In conclusion, this study shows that 11.39% of patients aged ≥65 years hospitalised due to CAP are readmitted within 30 days after an episode of CAP and that this was associated with living with a cohabitant aged <15 years, more than three hospital visits during the 90 previous days, chronic respiratory failure, heart failure, chronic liver disease and discharge to home with home healthcare services.

Because social factors, in addition to postdischarge and prereadmission clinical information, may influence the prognosis, it is important that these factors continue to be considered in future research.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: DT is the guarantor of this article. DT, MJP, EE, GN, ME and AD designed the research. DT and NS conducted the statistical analyses. DT, NT and AD wrote the initial draft of the manuscript, and DT, NS, NT, MJP, EE, GN, ME and AD reviewed the manuscript for accuracy and scientific content. The other members of the Project PI12/02079 Working Group contributed to the design of the study, patient recruitment, data collection and interpretation of the results.

Funding: This study was supported by the Institute of Health Carlos III with the European Regional Development Fund (FEDER) (PI12/02079) and the Catalan Agency for the Management of Grants for University Research (AGAUR Grant number 2017/ SGR 1342).

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Detail has been removed from this case description/these case descriptions to ensure anonymity. The editors and reviewers have seen the detailed information available and are satisfied that the information backs up the case the authors are making.

Ethics approval: Ethics committees of the participating hospitals.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data available.

Collaborators: The members of the Project PI12/02079 Working Group are by region: Andalusia: JM Mayoral (in memoriam) (Servicio de Vigilancia de Andalucía), J Díaz-Borrego (Servicio Andaluz de Salud), A Morillo (Hospital Universitario Virgen del Rocío), MJ Pérez-Lozano (Hospital Universitario Virgen de Valme), J Gutiérrez (Hospital Universitario Puerta del Mar), M Pérez-Ruiz, MA Fernández-Sierra (Complejo Hospitalario Universitario de Granada). Castile and Leon: S Tamames (Dirección General de Salud Pública, Investigación, Desarrollo e Innovación, Junta de Castilla y León), S Rojo-Rello (Hospital Clínico Universitario de Valladolid), R Ortiz de Lejarazu (Universidad de Valladolid), MI Fernández-Natal (Complejo Asistencial Universitario de León), T Fernández-Villa (GIIGAS-Grupo de Investigación en Interacción Gen-Ambiente y Salud, Universidad de León), A Pueyo (Hospital Universitario de Burgos), V Martín (Universidad de León; CIBERESP). Catalonia: A Vilella (Hospital Clínic), M Campins, A Antón (Hospital Universitari Vall d’Hebron; Universitat Autónoma de Barcelona), G Navarro (Corporació Sanitària i Universitaria Parc Taulí), M Riera (Hospital Universitari Mútua Terrassa), E Espejo (Hospital de Terrassa), MD Mas, R Pérez (ALTHAIA, Xarxa Hospitalaria de Manresa), JA Cayla, C Rius (Agència de Salut Pública de Barcelona; CIBERESP), P Godoy (Agència de Salut Pública de Catalunya; Institut de Recerca Biomèdica de Lleida, Universitat de Lleida; CIBERESP), N Torner (Agència de Salut Pública de Catalunya; Universitat de Barcelona; CIBERESP), C Izquierdo, R Torra (Agència de Salut Pública de Catalunya), L Force (Hospital de Mataró), A Domínguez, N Soldevila, I Crespo (Universitat de Barcelona; CIBERESP), D Toledo (Universitat de Barcelona). Valencia Community: M. Morales-Suárez-Varela (Universidad de Valencia; CIBERESP), F. Sanz (Consorci Hospital General Universitari de Valencia). Madrid: J Astray, MF Domínguez-Berjon, MA Gutiérrez, S Jiménez, E Gil, F Martín, R Génova-Maleras (Consejería de Sanidad), MC Prados, F. Enzzine de Blas, MA Salvador, S Rodríguez, M Romero (Hospital Universitario la Paz), JC Galán, E Navas, L Rodríguez (Hospital Ramón y Cajal), CJ Álvarez, E Banderas, S Fernandez (Hospital Universitario 12 de Octubre). Basque Country: M Egurrola, MJ López de Goicoechea (Hospital de Galdakao). Navarre: J Chamorro (Complejo Hospitalario de Navarra), I Casado, J Díaz-González, J Castilla (Instituto de Salud Pública de Navarra; Instituto de Investigación Sanitaria de Navarra; CIBERESP).

Contributor Information

the Project FIS PI12/02079 Working Group:

JM Mayoral, J Díaz-borrego, A Morillo, J Gutiérrez, M Pérez-ruiz, MA Fernández-sierra, S Tamames, S Rojo-Rello, R Ortiz De lejarazu, MI Fernández-Natal, T Fernández-Villa, A Pueyo, V Martín, A Vilella, M Campins, A Antón, M Riera, MD Mas, R Pérez, JA Cayla, C Rius, P Godoy, C Izquierdo, R Torra, L Force, I Crespo, M Morales-suárez-Varela, F Sanz, J Astray, MF Domínguez-Berjon, MA Gutiérrez, S Jiménez, E Gil, F Martín, R Génova-Maleras, MC Prados, F Enzzine de Blas, MA Salvador, S Rodríguez, M Romero, JC Galán, E Navas, L Rodríguez, CJ Álvarez, E Banderas, S Fernandez, MJ López de Goicoechea, J Chamorro, I Casado, J Díaz-González, and J Castilla

Collaborators: the Project FIS PI12/02079 Working Group

References

- 1.Donowitz GR, Cox HL. Bacterial community-acquired pneumonia in older patients. Clin Geriatr Med 2007;23:515–34. 10.1016/j.cger.2007.03.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Welte T, Torres A, Nathwani D. Clinical and economic burden of community-acquired pneumonia among adults in Europe. Thorax 2012;67:71–9. 10.1136/thx.2009.129502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blasi F, Mantero M, Santus P, et al. Understanding the burden of pneumococcal disease in adults. Clin Microbiol Infect 2012;18(Suppl5):7–14. 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2012.03937.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pneumonia. European lung white book. 2nd edn Sheffield, UK: European Respiratory Society/European Lung Foundation, 2003:55–65. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Koivula I, Stén M, Mäkelä PH. Prognosis after community-acquired pneumonia in the elderly: a population-based 12-year follow-up study. Arch Intern Med 1999;159:1550–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Torres A, Peetermans WE, Viegi G, et al. Risk factors for community-acquired pneumonia in adults in Europe: a literature review. Thorax 2013;68:1057–65. 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2013-204282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Quan TP, Fawcett NJ, Wrightson JM, et al. Increasing burden of community-acquired pneumonia leading to hospitalisation, 1998-2014. Thorax 2016;71:535–42. 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2015-207688 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.de Miguel-Díez J, Jiménez-García R, Hernández-Barrera V, et al. Trends in hospitalizations for community-acquired pneumonia in Spain: 2004 to 2013. Eur J Intern Med 2017;40:64–71. 10.1016/j.ejim.2016.12.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marrie TJ, Haldane EV, Faulkner RS, et al. Community-acquired pneumonia requiring hospitalization. Is it different in the elderly? J Am Geriatr Soc 1985;33:671–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dharmarajan K, Hsieh AF, Lin Z, et al. Diagnoses and timing of 30-day readmissions after hospitalization for heart failure, acute myocardial infarction, or pneumonia. JAMA 2013;309:355–63. 10.1001/jama.2012.216476 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kahlon S, Pederson J, Majumdar SR, et al. Association between frailty and 30-day outcomes after discharge from hospital. CMAJ 2015;187:799–804. 10.1503/cmaj.150100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tang VL, Halm EA, Fine MJ, et al. Predictors of rehospitalization after admission for pneumonia in the veterans affairs healthcare system. J Hosp Med 2014;9:379–83. 10.1002/jhm.2184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Steel K, Gertman PM, Crescenzi C, et al. Iatrogenic illness on a general medical service at a university hospital. N Engl J Med 1981;304:638–42. 10.1056/NEJM198103123041104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Elixhauser A, Steiner C. Readmissions to U.S. hospitals by diagnosis, 2010: statistical brief #153 Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) statistical briefs. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US), 2013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Halm EA, Fine MJ, Kapoor WN, et al. Instability on hospital discharge and the risk of adverse outcomes in patients with pneumonia. Arch Intern Med 2002;162:1278–84. 10.1001/archinte.162.11.1278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dong T, Cursio JF, Qadir S, et al. Discharge disposition as an independent predictor of readmission among patients hospitalised for community-acquired pneumonia. Int J Clin Pract 2017;71:e12935 10.1111/ijcp.12935 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Auerbach AD, Kripalani S, Vasilevskis EE, et al. Preventability and causes of readmissions in a national cohort of general medicine patients. JAMA Intern Med 2016;176:484 93. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.7863 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mykietiuk A, Carratalà J, Domínguez A, et al. Effect of prior pneumococcal vaccination on clinical outcome of hospitalized adults with community-acquired pneumococcal pneumonia. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 2006;25:457–62. 10.1007/s10096-006-0161-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Neupane B, Walter SD, Krueger P, et al. Predictors of inhospital mortality and re-hospitalization in older adults with community-acquired pneumonia: a prospective cohort study. BMC Geriatr 2010;10:22 10.1186/1471-2318-10-22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Domínguez À, Soldevila N, Toledo D, et al. Effectiveness of 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccination in preventing community-acquired pneumonia hospitalization and severe outcomes in the elderly in Spain. PLoS One 2017;12:e0171943 10.1371/journal.pone.0171943 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lindenauer PK, Normand SL, Drye EE, et al. Development, validation, and results of a measure of 30-day readmission following hospitalization for pneumonia. J Hosp Med 2011;6:142–50. 10.1002/jhm.890 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Calvillo-King L, Arnold D, Eubank KJ, et al. Impact of social factors on risk of readmission or mortality in pneumonia and heart failure: systematic review. J Gen Intern Med 2013;28:269–82. 10.1007/s11606-012-2235-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Adamuz J, Viasus D, Campreciós-Rodríguez P, et al. A prospective cohort study of healthcare visits and rehospitalizations after discharge of patients with community-acquired pneumonia. Respirology 2011;16:1119–26. 10.1111/j.1440-1843.2011.02017.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Capelastegui A, España Yandiola PP, Quintana JM, et al. Predictors of short-term rehospitalization following discharge of patients hospitalized with community-acquired pneumonia. Chest 2009;136:1079–85. 10.1378/chest.08-2950 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jasti H, Mortensen EM, Obrosky DS, et al. Causes and risk factors for rehospitalization of patients hospitalized with community-acquired pneumonia. Clin Infect Dis 2008;46:550–6. 10.1086/526526 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jencks SF, Williams MV, Coleman EA. Rehospitalizations among patients in the medicare fee-for-service program. N Engl J Med 2009;360:1418–28. 10.1056/NEJMsa0803563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mahoney FI, Barthel DW. Functional evaluation: the barthel index. Md State Med J 1965;14:61–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, et al. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis 1987;40:373–83. 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fine MJ, Auble TE, Yealy DM, et al. A prediction rule to identify low-risk patients with community-acquired pneumonia. N Engl J Med 1997;336:243–50. 10.1056/NEJM199701233360402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kats MH, Analysis M. A practical guide for clinicians and public health researches. 3rd edn New York, NY: Cambridge University Press, 2011:88–92. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fine MJ, Stone RA, Singer DE, et al. Processes and outcomes of care for patients with community-acquired pneumonia: results from the pneumonia Patient Outcomes Research Team (PORT) cohort study. Arch Intern Med 1999;159:970–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Epstein AM, Jha AK, Orav EJ. The relationship between hospital admission rates and rehospitalizations. N Engl J Med 2011;365:2287–95. 10.1056/NEJMsa1101942 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bohannon RW, Maljanian RD. Hospital readmissions of elderly patients hospitalized with pneumonia. Conn Med 2003;67:599–603. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ministerio de Sanidad, Servicios Sociales e Igualdad. La Gripe. https://www.msssi.gob.es/ciudadanos/enfLesiones/enfTransmisibles/gripe/gripe.htm (accessed 22 Dec 2017).

- 35.El Solh AA, Brewer T, Okada M, et al. Indicators of recurrent hospitalization for pneumonia in the elderly. J Am Geriatr Soc 2004;52:2010–5. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52556.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Millett ER, De Stavola BL, Quint JK, et al. Risk factors for hospital admission in the 28 days following a community-acquired pneumonia diagnosis in older adults, and their contribution to increasing hospitalisation rates over time: a cohort study. BMJ Open 2015;5:e008737 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-008737 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.O’Connor CM, Miller AB, Blair JE, et al. Causes of death and rehospitalization in patients hospitalized with worsening heart failure and reduced left ventricular ejection fraction: results from Efficacy of Vasopressin Antagonism in Heart Failure Outcome Study with Tolvaptan (EVEREST) program. Am Heart J 2010;159:841–9. 10.1016/j.ahj.2010.02.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dunlay SM, Weston SA, Killian JM, et al. Thirty-day rehospitalizations after acute myocardial infarction: a cohort study. Ann Intern Med 2012;157:11–18. 10.7326/0003-4819-157-1-201207030-00004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yakubek GA, Curtis GL, Sodhi N, et al. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease is associated with short-term complications following total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 2018. 10.1016/j.arth.2017.12.043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cook C, Coronado RA, Bettger JP, et al. The association of discharge destination with 30-day rehospitalization rates among older adults receiving lumbar spinal fusion surgery. Musculoskelet Sci Pract 2018;34:77–82. Epub ahead of print 10.1016/j.msksp.2018.01.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dodson JA, Williams MR, Cohen DJ, et al. Hospital practice of direct-home discharge and 30-day readmission after transcatheter aortic valve replacement in the society of thoracic surgeons/American college of cardiology transcatheter valve therapy (STS/ACC TVT) registry. J Am Heart Assoc 2017;6:e006127 10.1161/JAHA.117.006127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.